Damage-associated molecular patterns from conditioning-related tissue injury have been shown to aggravate acute graft-versus-host disease.

Results support a role for enhancing CD24–Siglec-10 interactions in regulating graft-versus-host disease after HSCT.

Visual Abstract

Patients who undergo human leukocyte antigen–matched unrelated donor (MUD) allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) with myeloablative conditioning for hematologic malignancies often develop acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) despite standard calcineurin inhibitor–based prophylaxis in combination with methotrexate. This trial evaluated a novel human CD24 fusion protein (CD24Fc/MK-7110) that selectively targets and mitigates inflammation due to damage-associated molecular patterns underlying acute GVHD while preserving protective immunity after myeloablative conditioning. This phase 2a, multicenter study evaluated the pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of CD24Fc in combination with tacrolimus and methotrexate in preventing acute GVHD in adults undergoing MUD HSCT for hematologic malignancies. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation phase to identify a recommended dose was followed by an open-label expansion phase with matched controls to further evaluate the efficacy and safety of CD24Fc in preventing acute GVHD. A multidose regimen of CD24Fc produced sustained drug exposure with similar safety outcomes when compared with single-dose regimens. Grade 3 to 4 acute GVHD–free survival at day 180 was 96.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 75.7-99.4) in the CD24Fc expansion cohort (CD24Fc multidose), compared with 73.6% (95% CI, 63.2-81.4) in matched controls (hazard ratio, 0.1 [95% CI, 0.0-0.6]; log-rank test, P = .03). No participants in the CD24Fc escalation or expansion phases experienced dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs). The multidose regimen of CD24Fc was well tolerated with no DLTs and was associated with high rates of severe acute GVHD–free survival after myeloablative MUD HSCT. This trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov as #NCT02663622.

Introduction

Matched unrelated donor (MUD) allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) with myeloablative conditioning is frequently used as a potent chemoimmunotherapy platform for treatment of aggressive hematologic malignancies.1,2 It is estimated that 40% to 60% of patients who undergo MUD allogeneic HSCT will develop acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) despite receiving standard calcineurin inhibitor–based prophylaxis in combination with methotrexate.2-5 Among all cases of acute GVHD, 15% to 25% involve severe disease (grade 3 or 4), which can result in mortality in up to 50% of patients.3,6

Tissue injury, initiated by pre-HSCT conditioning, amplifies experimental and clinical acute GVHD through release of inflammatory cytokines and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which activate host antigen-presenting cells.7-10 Antigen-presenting cells express counterregulatory sialic acid–binding immunoglobulin-like lectin-G (Siglec-G, or Siglec-10 in humans), which constrains the immune response to DAMPs.11 CD24, a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored glycoprotein ligand, promotes anti-inflammatory effects by binding and sequestering DAMPs or by natural ligand interactions with Siglec-G/10.11-13 Murine models of MUD HSCT demonstrate that defects in either Siglec-G or CD24 promote GVHD. Administration in animals of a human CD24 fusion protein (CD24Fc or MK-7110) ameliorated DAMP-mediated inflammation and GVHD-related mortality without impeding graft-versus-leukemia effect.14,15

Alloreactive T cells are principal mediators of acute GVHD; therefore, their activation, homing, or depletion have largely underpinned clinical strategies to improve preventive immunosuppressive regimens.16-18 Although direct T-cell therapies are effective in certain contexts, they often lack clear survival advantages because of offsetting risks of relapse, infection, and graft rejection.16,17,19-21 The CD24–Siglec-G pathway differs in that it primarily regulates responses of innate immune cells to tissue injury, discriminating between inflammation from tissue injury vs from pathogens.11 In preclinical murine models, CD24Fc reduced GVHD without adversely affecting graft-versus-leukemia responses and reduced immunotherapy-related adverse events (AEs) associated with anti–cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 and anti–programmed cell death 1 protein antibodies while preserving antitumor therapeutic effect.22-24 Moreover, in a phase 3 study, CD24Fc significantly accelerated clinical improvement and reduced hospitalization time compared with placebo in patients with COVID-19, suggesting that targeting tissue injury may play a role in other non-HSCT conditions.25 We hypothesized that enhancing CD24–Siglec-10 interactions beginning immediately before HSCT would reduce the incidence and severity of acute GVHD. Accordingly, a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted to identify a recommended safe dose, followed by an open-label expansion phase to evaluate the efficacy of CD24Fc in preventing GVHD after MUD HSCT.

Methods

Study population

Adults, aged 18 to 70 years, undergoing myeloablative allogeneic HSCT for hematologic malignancies were eligible. Hematologic malignancies included acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia in morphologic remission at time of HSCT. Participants received bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cells from MUDs with a human leukocyte antigen (HLA) 8-of-8 match at HLA-A, B, C, and DRB1. Participants were required to have a Karnofsky performance status score of >70% and hematopoietic cell transplantation–comorbidity index of ≤5.26 Candidates with active central nervous system or extramedullary disease involvement, prior transplantations, uncontrolled infection, or prior treatment with antithymocyte globulin or alemtuzumab were excluded; detailed eligibility criteria are included in the protocol.

Study design

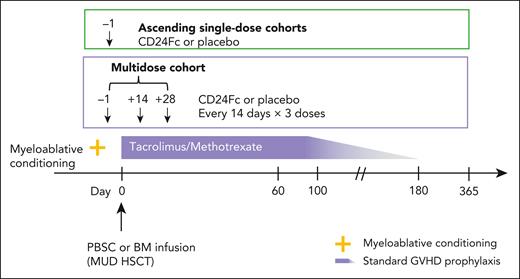

Double-blind, dose-escalation phase

The double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation phase of a phase 2a, multicenter study (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02663622) assessed pharmacokinetics (PKs), safety, tolerability, and dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) to select a maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of CD24Fc for phase 2b. There were 2 ascending single-dose cohorts (CD24Fc 240 or 480 mg, administered as a single-dose infusion on day −1) and 1 multidose cohort (CD24Fc 480, 240, and 240 mg, administered as an infusion on days −1, 14, and 28, respectively; dosages were based on safety considerations and optimal drug exposure at time of GVHD risk; Figure 1). Twenty-four participants (6 per cohort) were randomized 3:1 to CD24Fc vs placebo (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood website). The myeloablative conditioning regimen was selected by the local investigator before HSCT (supplemental Methods).

Phase 2a study schema of CD24Fc for GVHD prevention. Two ascending single-dose cohorts and a multidose cohort. BM, bone marrow; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cell.

Phase 2a study schema of CD24Fc for GVHD prevention. Two ascending single-dose cohorts and a multidose cohort. BM, bone marrow; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cell.

Open-label expansion phase and expansion cohort

The open-label, single-cohort expansion phase of the phase 2a study further evaluated safety and efficacy of the CD24Fc multidose regimen for preventing acute GVHD (supplemental Figure 2). The study protocol was amended to include this expansion phase (n = 20) to increase the number of participants who received the multidose regimen and allow efficacy end point comparisons between the expansion cohort and matched controls receiving standard GVHD prophylaxis alone from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) using propensity score matching (supplemental Methods). The CD24Fc-treated expansion cohort comprised 26 participants: 6 from the initial double-blind, dose-escalation phase who received the multidose regimen, and 20 additional participants from the open-label expansion phase. A planned cohort of patients identified in the CIBMTR database was included to serve as controls for the expansion cohort. Please refer to supplemental Methods for eligibility criteria and matching procedures.

End points and outcomes

Double-blind, dose-escalation phase

Primary end points were proportion of participants with AEs, discontinuations because of AEs, incidence of DLTs, and MTD. Please refer to supplemental Methods for DLT definitions and a list of efficacy end points, which were secondary; refer to supplemental Table 1 for efficacy end point definitions.

Expansion cohort

Primary end point was grade 3 to 4 acute GVHD–free survival (GFS) at day 180. Secondary end points were grade 2 to 4 acute GFS at day 180, relapse-free survival (RFS) at 1 year, and overall survival (OS) at 1 year. Please refer to supplemental Methods for exploratory efficacy end points.

Statistical analyses

Demographic and baseline summaries were based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, which included all randomized participants. Baseline was defined as the last observation before the first administration of study drug or placebo or as the last observation before HSCT (for matched controls). The PK population included all participants in the ITT population who received CD24Fc with ≥1 evaluable postbaseline PK sample. Missing values were not imputed and were recorded as missing. The PK parameters (supplemental Table 2) were calculated using standard noncompartmental analyses of individual time–concentration profiles from each participant with sufficient plasma concentration data (supplemental Methods).

Safety analyses included participants who received ≥1 dose of study drug (CD24Fc or placebo). Only AEs encountered during the treatment period (defined as day −1 to 30 for the single-dose cohorts and day −1 to 60 for the multidose cohort) were included (unless the event reflected an ongoing toxicity initiated during the treatment period). DLTs were to be summarized by system organ class and preferred term for all participants who received any amount of CD24Fc and completed the DLT evaluation period (day −1 to 30 or 60). Incidence of DLTs (primary safety end point in the double-blind, dose-escalation phase; refer to supplemental Methods for definitions) was used to determine the MTD for the expansion phase.

Efficacy analyses were performed on the modified ITT population, which comprised all randomized participants who received study drug and underwent HSCT. In the double-blind, dose-escalation phase, efficacy analyses were descriptive; no formal hypothesis testing was performed. In a planned analysis, clinical outcomes of the expansion cohort were compared with those of matched controls from the CIBMTR database. Twenty participants in the expansion cohort with 80 matched controls would provide 80% power to detect a hazard ratio (HR) of 5.0 (corresponding to an improvement in the 180-day acute GFS rate from 0.75 to 0.945) using a 2-sided log-rank test at the 5% significance level. In the expansion cohort, P values, odds ratios, and HRs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were derived from the respective analyses.

Probabilities of grade 2 to 4 acute GFS, grade 3 to 4 acute GFS, OS, and RFS were calculated using Kaplan-Meier analysis with censoring for those alive, in remission, and without the event of interest. Specifically, for GFS analyses, participants alive at the data cutoff date with no documented occurrence of grade 2 to 4 or grade 3 to 4 acute GVHD were censored at the last date of acute GVHD assessment on, or before, day 180. Confirmed recurrence or relapse of primary disease was also considered a censoring event. Outcomes were compared between the CD24Fc cohort and matched controls using a stratified, 2-sided, log-rank test (α = 0.05) with donor stem cell source as the stratification factor. Stratified Cox or Fine-Gray regression was used to obtain HRs with 95% CIs. Owing to differences in the proportion of participants treated with CD24Fc vs matched controls receiving total body irradiation (TBI), a post hoc sensitivity analysis was performed using a robust sandwich covariance estimator with treatment and TBI-based conditioning regimen as factors. Secondary end points, only tested if the primary end point was significant, were evaluated using Hochberg procedure to control for overall type I error rate at 0.05. Please refer to supplemental Methods for further details. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 or higher (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Correlative studies

To assess levels of the DAMP high mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1), plasma samples were collected from a subset of participants treated with CD24Fc in the expansion cohort (n = 12) and cryopreserved on day −7 (±2 days, preconditioning), day −1 (postconditioning, pretreatment), and day 28 (±2 days, post-HSCT, posttreatment). HMGB1 was analyzed using Luminex (Simplex ProcartaPlex Kit; ThermoFisher Scientific).

To assess levels of the GVHD biomarker suppression of tumorigenicity 2 and cytokines, plasma samples were collected from a subset of participants in the dose-escalation cohorts (CD24Fc multidose, n = 3; placebo, n = 3) and were analyzed at day −7 (±2 days, preconditioning) and day 28 (±2 days, post-HSCT, posttreatment) using Luminex (Invitrogen).

Study oversight

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Council for Harmonization guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. The research protocol was approved by institutional review boards at participating centers. All participants and donors provided written informed consent before study entry (supplemental Methods).

Results

Participant population

Demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Mean ages were comparable across the escalation-phase (single-dose, multidose, placebo) and expansion cohorts. Proportions of participants in the high-risk comorbidity index score and Karnofsky performance status of ≤80% categories were similar across escalation-phase cohorts and expansion cohort/matched controls. The most common primary diagnosis was acute myeloid leukemia, with most participants receiving peripheral blood stem cells as the graft source. Across escalation-phase (single-dose, multidose, placebo) and expansion cohorts, all participants demonstrated neutrophil and platelet engraftment, excluding 1 participant receiving placebo (who demonstrated neutrophil engraftment but not platelet engraftment); none had primary engraftment failure. Median (range) time to neutrophil and platelet engraftment was 13 (12-23) and 13 (9-23) days, respectively, for participants receiving CD24Fc in the escalation-phase cohorts and 14 (12-25) and 14 (9-25) days, respectively, for the expansion cohort.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

| Parameter . | Double-blind, dose-escalation cohorts . | Expansion cohort/matched controls . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 6) . | CD24Fc 240 mg (n = 6) . | CD24Fc 480 mg (n = 6) . | CD24Fc 480/240/240 mg∗ (n = 6) . | CD24Fc total (n = 18) . | Matched controls (n = 92) . | CD24Fc 480/240/240 mg∗ (n = 26†) . | |

| Age, mean (SD), y‡ | 53.8 (11.67) | 54.2 (16.82) | 53.3 (19.76) | 57.3 (11.15) | 54.9 (15.42) | 50.1 (12.92) | 51.3 (13.28) |

| Age group, y | |||||||

| <65§ | 5 (83.3) | 5 (83.3) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | 11 (61.1) | 79 (85.9) | 21 (80.8) |

| ≥65§ | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | 7 (38.9) | 13 (14.1) | 5 (19.2) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 4 (66.7) | 4 (66.7) | 4 (66.7) | 3 (50.0) | 11 (61.1) | 64 (69.6) | 14 (53.8) |

| Female | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) | 7 (38.9) | 28 (30.4) | 12 (46.2) |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 6 (100.0) | 5 (83.3) | 6 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 17 (94.4) | 79 (85.9) | 25 (96.2) |

| African American | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (4.3) | 1 (3.8) |

| Pacific Islander/Asian | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 (7.6) | 0 |

| American Indian | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 0 |

| Not reported | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.6) | 1 (1.1) | 0 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.6) | 2 (2.2) | 0 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 6 (100.0) | 5 (83.3) | 6 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 17 (94.4) | 89 (96.7) | 26 (100.0) |

| NA (non-US resident) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 0 |

| Primary diagnosis‖ | |||||||

| AML | 2 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | 1 (16.7) | 7 (38.9) | 54 (58.7) | 12 (46.2) |

| ALL | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (16.7) | 17 (18.5) | 7 (26.9) |

| CML | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 2 (11.1) | 2 (2.2) | 1 (3.8) |

| MDS | 3 (50.0) | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 4 (66.7) | 5 (27.8) | 19 (20.7) | 6 (23.1) |

| CMML | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 1 (5.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Refined disease risk index | |||||||

| Low/intermediate | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 65 (70.7) | 21 (80.8) |

| High/very high | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 27 (29.3) | 5 (19.2) |

| Karnofsky performance status at baseline | |||||||

| 90%-100% | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (50.0) | 5 (27.8) | 62 (67.4) | 17 (65.4) |

| 70%-80% | 5 (83.3) | 5 (83.3) | 5 (83.3) | 3 (50.0) | 13 (72.2) | 30 (32.6) | 9 (34.6) |

| Comorbidity index risk category at baseline | |||||||

| Low (0) | 3 (50.0) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 5 (27.8) | 19 (20.7) | 6 (23.1) |

| Intermediate (1-2) | 2 (33.3) | 5 (83.3) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 9 (50.0) | 42 (45.7) | 13 (50.0) |

| High (3-4)¶ | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 4 (22.2) | 31 (33.7) | 7 (26.9) |

| Graft type | |||||||

| PBSCs | 4 (66.7) | 4 (66.7) | 5 (83.3) | 5 (83.3) | 14 (77.8) | 86 (93.5) | 23 (88.5) |

| BM | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (22.2) | 6 (6.5) | 3 (11.5) |

| Donor-recipient sex | |||||||

| Male-male | 3 (50.0) | 2 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) | 2 (33.3) | 7 (38.9) | 48 (52.2) | 9 (34.6) |

| Male-female | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 6 (33.3) | 18 (19.6) | 7 (26.9) |

| Female-male | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (22.2) | 16 (17.4) | 3 (11.5) |

| Female-female | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 1 (5.6) | 10 (10.9) | 5 (19.2) |

| Unknown-male | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (7.7) |

| Conditioning regimen | |||||||

| TBI/Cy | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (22.2) | 20 (21.7) | 3 (11.5) |

| TBI/Cy/etoposide | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 0 |

| TBI/etoposide | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 0 |

| Bu/Cy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 41 (44.6) | 0 |

| Bu/Flu | 6 (100.0) | 5 (83.3) | 4 (66.7) | 5 (83.3) | 14 (77.8) | 28 (30.4) | 16 (61.5) |

| Flu/melphalan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 0 |

| Cy/thiotepa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 (26.9) |

| Parameter . | Double-blind, dose-escalation cohorts . | Expansion cohort/matched controls . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 6) . | CD24Fc 240 mg (n = 6) . | CD24Fc 480 mg (n = 6) . | CD24Fc 480/240/240 mg∗ (n = 6) . | CD24Fc total (n = 18) . | Matched controls (n = 92) . | CD24Fc 480/240/240 mg∗ (n = 26†) . | |

| Age, mean (SD), y‡ | 53.8 (11.67) | 54.2 (16.82) | 53.3 (19.76) | 57.3 (11.15) | 54.9 (15.42) | 50.1 (12.92) | 51.3 (13.28) |

| Age group, y | |||||||

| <65§ | 5 (83.3) | 5 (83.3) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | 11 (61.1) | 79 (85.9) | 21 (80.8) |

| ≥65§ | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | 7 (38.9) | 13 (14.1) | 5 (19.2) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 4 (66.7) | 4 (66.7) | 4 (66.7) | 3 (50.0) | 11 (61.1) | 64 (69.6) | 14 (53.8) |

| Female | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) | 7 (38.9) | 28 (30.4) | 12 (46.2) |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 6 (100.0) | 5 (83.3) | 6 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 17 (94.4) | 79 (85.9) | 25 (96.2) |

| African American | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (4.3) | 1 (3.8) |

| Pacific Islander/Asian | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 (7.6) | 0 |

| American Indian | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 0 |

| Not reported | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.6) | 1 (1.1) | 0 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.6) | 2 (2.2) | 0 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 6 (100.0) | 5 (83.3) | 6 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 17 (94.4) | 89 (96.7) | 26 (100.0) |

| NA (non-US resident) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 0 |

| Primary diagnosis‖ | |||||||

| AML | 2 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | 1 (16.7) | 7 (38.9) | 54 (58.7) | 12 (46.2) |

| ALL | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (16.7) | 17 (18.5) | 7 (26.9) |

| CML | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 2 (11.1) | 2 (2.2) | 1 (3.8) |

| MDS | 3 (50.0) | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 4 (66.7) | 5 (27.8) | 19 (20.7) | 6 (23.1) |

| CMML | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 1 (5.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Refined disease risk index | |||||||

| Low/intermediate | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 65 (70.7) | 21 (80.8) |

| High/very high | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 27 (29.3) | 5 (19.2) |

| Karnofsky performance status at baseline | |||||||

| 90%-100% | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (50.0) | 5 (27.8) | 62 (67.4) | 17 (65.4) |

| 70%-80% | 5 (83.3) | 5 (83.3) | 5 (83.3) | 3 (50.0) | 13 (72.2) | 30 (32.6) | 9 (34.6) |

| Comorbidity index risk category at baseline | |||||||

| Low (0) | 3 (50.0) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 5 (27.8) | 19 (20.7) | 6 (23.1) |

| Intermediate (1-2) | 2 (33.3) | 5 (83.3) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 9 (50.0) | 42 (45.7) | 13 (50.0) |

| High (3-4)¶ | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 4 (22.2) | 31 (33.7) | 7 (26.9) |

| Graft type | |||||||

| PBSCs | 4 (66.7) | 4 (66.7) | 5 (83.3) | 5 (83.3) | 14 (77.8) | 86 (93.5) | 23 (88.5) |

| BM | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (22.2) | 6 (6.5) | 3 (11.5) |

| Donor-recipient sex | |||||||

| Male-male | 3 (50.0) | 2 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) | 2 (33.3) | 7 (38.9) | 48 (52.2) | 9 (34.6) |

| Male-female | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 6 (33.3) | 18 (19.6) | 7 (26.9) |

| Female-male | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (22.2) | 16 (17.4) | 3 (11.5) |

| Female-female | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 1 (5.6) | 10 (10.9) | 5 (19.2) |

| Unknown-male | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (7.7) |

| Conditioning regimen | |||||||

| TBI/Cy | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (22.2) | 20 (21.7) | 3 (11.5) |

| TBI/Cy/etoposide | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 0 |

| TBI/etoposide | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 0 |

| Bu/Cy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 41 (44.6) | 0 |

| Bu/Flu | 6 (100.0) | 5 (83.3) | 4 (66.7) | 5 (83.3) | 14 (77.8) | 28 (30.4) | 16 (61.5) |

| Flu/melphalan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 0 |

| Cy/thiotepa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 (26.9) |

Except for mean (SD) age, all values are reported as n (%); percentages were calculated using the number of participants in the column heading as the denominator.

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BM, bone marrow; Bu, busulfan; CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; CMML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; Cy, cyclophosphamide; Flu, fludarabine; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; NA, not applicable; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cell; SD, standard deviation.

Regimen (infusion): 480, 240, and 240 mg on days −1, 14, and 28, respectively.

Expansion cohort includes n = 6 participants from the double-blind, dose-escalation cohort and n = 20 additional participants from the open-label expansion phase.

Age for double-blind, dose-escalation cohorts reported as mean age at time of informed consent; age for expansion cohort/matched controls reported as mean age at time of HSCT.

For expansion cohort/matched controls, values are ≤65 and >65 years, respectively.

None of the participants in the expansion cohort had CMML, thus, the selection criteria for matched controls only included AML, ALL, CML, and MDS.

Comorbidity index risk category of high ranges from 3 to 5 for expansion cohort/matched controls.

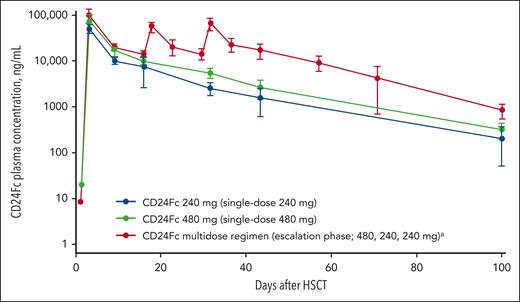

PKs

In the escalation-phase multidose cohort, PK data demonstrated sustained drug levels through day 100 (Figure 2). Mean (standard deviation) plasma concentration on day 100 was 850.8 (302.8) ng/mL for the multidose cohort, vs 216.4 (161.9) and 331.0 (123.2) ng/mL for the 240- and 480-mg single-dose cohorts, respectively. Median time to reach maximum concentration was 2.1 hours for day −1 dosing (single-dose and multidose cohorts) and 2.5 hours for day 28 dosing (multidose cohort). Mean (standard deviation) half-life was ∼17 (4) days. Additional PK results are reported in the supplemental Results and supplemental Table 3.

Mean (standard deviation) plasma CD24Fc concentration (ng/mL) vs time on a semilogarithmic scale, PK population.aRegimen (infusion): 480, 240, and 240 mg on days −1, 14, and 28, respectively.

Mean (standard deviation) plasma CD24Fc concentration (ng/mL) vs time on a semilogarithmic scale, PK population.aRegimen (infusion): 480, 240, and 240 mg on days −1, 14, and 28, respectively.

Dose selection

There were no DLTs during the double-blind, dose-escalation phase, and all planned doses were administered without reaching an MTD. The multidose regimen was selected for further study in the expansion cohort given the comparable safety profile among the dosing regimens and PK data showing more sustained exposure (ie, higher mean plasma CD24Fc concentrations from time of engraftment through day 100; supplemental Results).

Double-blind, dose-escalation phase

Safety and toxicity

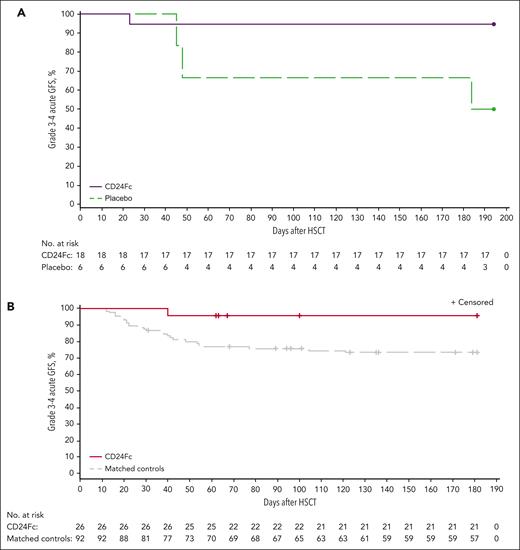

All participants experienced treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) from time of study drug infusion through day 30 (post-HSCT; single-dose cohorts) or through day 60 (post-HSCT; multidose cohort; supplemental Table 4). CD24Fc-related TEAEs included diarrhea and hyperglycemia, which occurred in 1 participant in the 480-mg single-dose cohort but did not prompt study discontinuation. Stomatitis, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia were the most common TEAEs (supplemental Table 5). Treatment-emergent infections occurred in 4 (22.2%) participants receiving CD24Fc, 2 (11.1%) of whom experienced grade ≥3 infections, and in 2 (33.3%) participants receiving placebo, 1 (16.7%) of whom experienced a grade ≥3 infection. There were no differences in overall TEAEs or discontinuations because of study drug–related TEAEs between CD24Fc and placebo cohorts. There was 1 participant death from pneumonia and pneumomediastinum in the placebo cohort during the treatment period. There were no infection-related mortalities associated with CD24Fc treatment. Secondary end points for efficacy in the escalation-phase cohorts are reported in Figure 3A and supplemental Tables 6 and 7.

Kaplan-Meier plot of grade 3 to 4 acute GFS through day 180. (A) Escalation-phase cohorts (pooled CD24Fc and placebo); (B) expansion cohort/matched controls. Follow-up was censored for 4 participants who experienced relapse of primary disease before day 180.

Kaplan-Meier plot of grade 3 to 4 acute GFS through day 180. (A) Escalation-phase cohorts (pooled CD24Fc and placebo); (B) expansion cohort/matched controls. Follow-up was censored for 4 participants who experienced relapse of primary disease before day 180.

Expansion cohort

Efficacy

The primary efficacy end point of grade 3 to 4 acute GFS at day 180 was significantly greater in the CD24Fc multidose cohort (n = 26; 96.2% [95% CI, 75.7-99.4]) compared with matched controls (n = 92; 73.6% [95% CI, 63.2-81.4]; survival curve HR, 0.1 [95% CI, 0.0-0.6]; and log-rank test, P = .03; Figure 3B; Table 2). After factoring for differences in TBI-based conditioning, grade 3 to 4 acute GFS at day 180 was still significantly different between participants treated with CD24Fc and matched controls (HR, 0.1; 95% CI, 0.0-0.6; log-rank test, P = .03).

Efficacy end points for expansion cohort/matched controls (modified ITT population)

| End point . | Rate, % (95% CI)∗ . | HR (95% CI)§ . | P . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matched controls (n = 92) . | CD24Fc 480/240/240 mg† (n = 26‡) . | |||

| Primary end point | ||||

| Grade 3-4 acute GFS through day 180 | 73.6 (63.2-81.4) | 96.2 (75.7-99.4) | 0.1 (0.0-0.6) | .03 |

| Secondary end points | ||||

| Grade 2-4 acute GFS through day 180 | 49.4 (38.8-59.2) | 64.4 (42.6-79.7) | 0.6 (0.3-1.1) | .30‖ |

| RFS through 1 y | 71.6 (61.2-79.7) | 64.8 (43.2-79.9) | 1.3 (0.7-2.5) | .91‖ |

| OS through 1 y | 79.2 (69.3-86.2) | 76.7 (55.3-88.8) | 1.1 (0.4-2.9) | .91‖ |

| Exploratory end points | ||||

| Grade 2-4 acute GVHD, cumulative incidence through day 100 | 47.8 (37.3-57.6) | 30.8 (14.3-49.0) | 0.5 (0.3-1.1) | — |

| Chronic GVHD, cumulative incidence through 1 y | 48.9 (38.1-58.8) | 50.0 (29.2-67.7) | 1.1 (0.6-2.0) | — |

| Relapse, cumulative incidence through 1 y | 17.5 (10.5-26.0) | 27.3 (11.8-45.5) | 1.6 (0.7-3.9) | — |

| Nonrelapse mortality, cumulative incidence through 1 y | 10.9 (5.5-18.3) | 7.7 (1.3-22.1) | 0.7 (0.2-3.1) | — |

| End point . | Rate, % (95% CI)∗ . | HR (95% CI)§ . | P . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matched controls (n = 92) . | CD24Fc 480/240/240 mg† (n = 26‡) . | |||

| Primary end point | ||||

| Grade 3-4 acute GFS through day 180 | 73.6 (63.2-81.4) | 96.2 (75.7-99.4) | 0.1 (0.0-0.6) | .03 |

| Secondary end points | ||||

| Grade 2-4 acute GFS through day 180 | 49.4 (38.8-59.2) | 64.4 (42.6-79.7) | 0.6 (0.3-1.1) | .30‖ |

| RFS through 1 y | 71.6 (61.2-79.7) | 64.8 (43.2-79.9) | 1.3 (0.7-2.5) | .91‖ |

| OS through 1 y | 79.2 (69.3-86.2) | 76.7 (55.3-88.8) | 1.1 (0.4-2.9) | .91‖ |

| Exploratory end points | ||||

| Grade 2-4 acute GVHD, cumulative incidence through day 100 | 47.8 (37.3-57.6) | 30.8 (14.3-49.0) | 0.5 (0.3-1.1) | — |

| Chronic GVHD, cumulative incidence through 1 y | 48.9 (38.1-58.8) | 50.0 (29.2-67.7) | 1.1 (0.6-2.0) | — |

| Relapse, cumulative incidence through 1 y | 17.5 (10.5-26.0) | 27.3 (11.8-45.5) | 1.6 (0.7-3.9) | — |

| Nonrelapse mortality, cumulative incidence through 1 y | 10.9 (5.5-18.3) | 7.7 (1.3-22.1) | 0.7 (0.2-3.1) | — |

Kaplan-Meier estimate.

Regimen (infusion): 480, 240, and 240 mg on days −1, 14, and 28, respectively.

Expansion cohort includes n = 6 participants from the double-blind, dose-escalation cohort and n = 20 additional participants from the open-label expansion phase.

For the expansion cohort, HRs were generated relative to matched controls.

Reports adjusted P value based on Hochberg procedure.

Grade 2 to 4 acute GFS at day 180 for CD24Fc was 64.4% (95% CI, 42.6-79.7), compared with 49.4% (95% CI, 38.8-59.2) for matched controls (P = .30). There was no significant difference in RFS (P = .61; supplemental Figure 3), OS (P = .91; supplemental Figure 4), or cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD (P = .78; supplemental Figure 5).

Among those treated with CD24Fc, 1 participant developed grade 4 acute GVHD after undergoing immunosuppressant withdrawal and treatment for relapse of primary disease (supplemental Table 8). Of 20 (76.9%) participants who survived 1 year after HSCT, 11 (42.3%) were no longer receiving immunosuppressive therapy. Of 13 (50.0%) participants who had chronic GVHD at 1 year after HSCT, 6 (23.0%) had moderate or severe chronic GVHD. Other exploratory efficacy results are presented in Table 2 and supplemental Table 8.

Safety

The multidose regimen in the expansion cohort was well tolerated in most participants. Three participants experienced CD24Fc-related TEAEs including QT prolongation, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, diarrhea, hypomagnesemia, and hypotension. In 1 instance (QT prolongation), further CD24Fc therapy was withheld. No severe (grade ≥3) CD24Fc-related TEAEs were observed. Treatment-emergent infections occurred in 11 (42.3%) participants who received CD24Fc treatment; of those, 7 (26.9%) had grade ≥3 infections. Two events of Stevens-Johnson syndrome occurred in the expansion cohort and were not considered to be drug related. In 1 participant, a vesicular skin rash positive for herpes simplex virus type 1 and bacterial infection progressed to grade 5 Stevens-Johnson syndrome 16 days after their last CD24Fc dose. A second participant who was admitted for sepsis developed a grade 4 rash 225 days after completing the last dose of CD24Fc, which resolved after changing antibiotic therapy. Investigators attributed both of these events to antimicrobial treatments for infection (cephalosporin and sulfonamide, respectively). Please refer to supplemental Results for additional details.

At 1 year after HSCT, there were 6 (23.1%) deaths in the expansion cohort; 4 were related to relapse and 2 were related to nonrelapse mortality. Among 19 (20.7%) deaths in matched controls, 9 were related to relapse and 10 were related to nonrelapse mortality.

Correlative studies

In a subset of participants (n = 12) from the expansion cohort, HMGB1 levels significantly increased from day −7 (preconditioning) to day −1 (postconditioning) and significantly decreased from day −1 to day 28 (posttreatment [after 2 of 3 doses]), returning to below-baseline levels (Figure 4).

DAMP (HMGB1) levels of participants (CD24Fc multidose, n = 12) in the open-label expansion cohort. Plasma samples obtained on day –7 (±2 days, preconditioning), day –1 (postconditioning, pretreatment), and day 28 (±2 days, post-HSCT, posttreatment). ∗P < .05; Wilcoxon signed-rank test (GraphPad Prism 8.0). SE, standard error.

DAMP (HMGB1) levels of participants (CD24Fc multidose, n = 12) in the open-label expansion cohort. Plasma samples obtained on day –7 (±2 days, preconditioning), day –1 (postconditioning, pretreatment), and day 28 (±2 days, post-HSCT, posttreatment). ∗P < .05; Wilcoxon signed-rank test (GraphPad Prism 8.0). SE, standard error.

Additional plasma GVHD biomarkers and inflammatory cytokines were analyzed in participants receiving CD24Fc multidose (n = 3) or placebo (n = 3) in the dose-escalation phase but did not show any significant changes or trends between day −7 and day 28 (supplemental Figure 6; supplemental Table 9).

Discussion

This trial was designed to determine a recommended dose (or MTD) of CD24Fc while assessing its efficacy in preventing acute GVHD in recipients undergoing MUD HSCT with myeloablative conditioning. In the dose-escalation phase, a multidose regimen of CD24Fc was well tolerated. The expansion cohort demonstrated similar safety, and CD24Fc concurrently with tacrolimus/methotrexate resulted in a high percentage of participants achieving acute GFS, which compared favorably to matched controls.

In the double-blind, dose-escalation phase, across cohorts, participants had similar distributions of age and comorbidities that placed them at risk of acute GVHD and transplantation-related mortality. Observed TEAEs represented common effects of myeloablative HSCT (eg, stomatitis, blood cytopenia, and electrolyte disorders) and did not require drug discontinuation. All CD24Fc cohorts were completed without occurrence of DLTs or infection-related mortality. The multidose regimen was selected for the open-label expansion cohort because of a sustained increase in drug exposure during the time period of peak GVHD risk (engraftment through 100 days after HSCT; Figure 2) and no additional safety concerns over the single-dose regimens. The relatively small number of participants limits interpretability of these safety findings; however, no unexpected drug-related AEs or toxicities were observed. Moreover, considering potential impacts of the multidose regimen on logistics and costs, as well as the occurrence of DAMP-mediated inflammation early after HSCT, additional biomarker or clinical data supporting the need for a CD24Fc multidose regimen may be warranted in future studies.

In the expansion cohort, incidence of grade 3 to 4 acute GVHD in those receiving CD24Fc remained low (3.8%) without other mortality at day 180, resulting in 96.2% of participants achieving grade 3 to 4 acute GFS and thus meeting the expansion cohort’s primary end point. This was significantly greater when compared with matched controls (73.6%), who also received myeloablative conditioning with tacrolimus/methotrexate.

The primary efficacy end point evaluated here (GFS) was assessed in a placebo-controlled trial of a recently approved GVHD prophylactic treatment (abatacept).27 In that trial, participants undergoing MUD HSCT and receiving myeloablative conditioning with costimulatory blockade with abatacept combined with tacrolimus and methotrexate had favorable GVHD outcomes, reporting a 93.2% incidence of grade 3 to 4 acute GFS at 6 months. This result was significantly greater when compared with tacrolimus and methotrexate controls and contributed to regulatory approval of abatacept for GVHD prevention. Newer options for prevention (eg, posttransplantation cyclophosphamide [PtCy] and sitagliptin) have demonstrated impressive results, including low grade 3 to 4 GVHD rates (2%-3%), but important differences in conditioning regimen (reduced intensity for PtCy) and other components of the GVHD prophylaxis regimen (tacrolimus plus sirolimus for sitagliptin) limit comparisons to our study.28,29 Rates of severe acute GVHD in our study were suppressed, and there did not appear to be detrimental effects on early survival. This suggests that CD24Fc may provide protection against GVHD, especially high-risk involvement of the lower gastrointestinal tract and liver, without reciprocal increases in alternative causes of mortality (eg, relapse and infection). These attributes may facilitate improved survival outcomes after HSCT but will require further validation in future studies.

Regarding additional key secondary end points, moderate to severe (grade 2-4) acute GFS, although numerically higher than matched controls, did not reach statistical significance. One explanation was the 31% incidence of grade 2 to 4 acute GVHD in recipients of CD24Fc, which largely reflected isolated cutaneous involvement. This may indicate the overall higher prevalence of cutaneous GVHD but may also suggest that protective effects of CD24Fc are associated with gastrointestinal tissues involved in conditioning-related injury at the time of HSCT. Regardless, all instances of GVHD encountered in our study were responsive to corticosteroid treatment. Similar to a recent trial of abatacept,27 CD24Fc did not affect subsequent rates of chronic GVHD (Table 2; supplemental Table 7), a finding that differs from T-cell–depleting approaches used in other prevention trials (eg, anti–T-lymphocyte globulin, PtCy, or sitagliptin).16 In a recent phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, CD24Fc accelerated clinical improvement in patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19, further suggesting that targeting the CD24–Siglec-10 pathway may play a role in mitigating acute inflammation in non-HSCT disease.25 Based on the timing of our treatment course and the mechanism of CD24Fc in attenuating inflammation from DAMPs, it is possible that immunologic effects on chronic GVHD might wane at time points more distal to HSCT. Furthermore, because CD24Fc targets DAMP-mediated inflammation, its role in less-intensive conditioning regimens will require additional research.

Although freedom from severe acute GVHD might have been anticipated to favorably influence OS in our study, the sample size and design were insufficient to evaluate effects on OS. Another limitation was the lack of a bona fide placebo group in the expansion cohort, which resulted in differences in the types of myeloablative-conditioning regimens received by participants treated with CD24Fc vs matched controls. Thus, the potential for unrecognized heterogeneity to affect outcomes in matched controls must be considered when interpreting results. Moreover, given the study size, we acknowledge that although CD24Fc had a favorable safety profile, the incidence of infection and certain rare toxicities observed such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome will require additional careful monitoring in future trials. Nevertheless, strengths of this study include the uniform patient population and well-matched controls, with all participants receiving the same prophylactic regimen.

A growing body of basic and preclinical literature demonstrates that tissue damage ensuing HSCT and the associated release of numerous inflammatory DAMPs (such as HMGB1, adenosine triphosphate, heparan sulfate, and uric acid) are key signals that amplify GVHD.2,8,30,31 Consistent with this hypothesis, we observed significant elevations in plasma HMGB1 levels after myeloablative conditioning, which subsequently returned to levels below baseline after CD24Fc treatment. Considering the wide number of DAMPs, limited sample size, and absence of controls, these data should not be interpreted as evidence for a CD24Fc treatment effect. Nonetheless, preclinical evidence suggests that CD24Fc targets a heretofore unexplored pathway in GVHD by engaging immunoreceptors on donor antigen-presenting cells to prevent their activation, alloantigen presentation, and inflammation in the presence of DAMPs.14,15 Therefore, enhancing the CD24–Siglec-10 axis may play an important early role in protecting against DAMP-mediated GVHD. As opposed to therapies that focus on any 1 specific molecule or signaling pathway, downregulation of this central mechanism used by several DAMPs may have important impacts on preventing GVHD.

In conclusion, administration of a multidose regimen of CD24Fc was well tolerated and associated with high rates of severe acute GFS after myeloablative MUD HSCT. These data on the first proof-of-concept clinical trial, together with prior experimental evidence, demonstrate that enhancing CD24–Siglec-10 interactions early after HSCT may suppress severe acute GVHD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ryan M. Drzewicki for administrative and logistical support as the multisite project manager for this study. The authors also thank the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) member centers in the United States and throughout the world for reporting patients to the CIBMTR (refer to https://www.cibmtr.org/About/WhoWeAre/Centers/Pages/index.aspx) and contributing to this study. All authors vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and the fidelity of the trial to the protocol. Writing, editorial, and administrative assistance was provided by Shina Satoh, Alexandra Kennedy, and Jenna Lewis (MedThink SciCom, Cary, NC); and Amy O. Johnson-Levonas and Jennifer Rotonda (Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co, Inc, Rahway, NJ). This assistance was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co, Inc, Rahway, NJ. CD24Fc has been acquired by Merck & Co, Inc, Rahway, NJ.

The trial was funded by OncoImmune, Inc, Rockville, MD, a wholly owned subsidiary of Merck & Co, Inc, Rahway, NJ. The trial was partially supported by grants from the US Food and Drug Administration Office of Orphan Product Development Clinical Trials (grant R01FD006089-01 [Y.L.]), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute (NCI) (grant R01CA217156 [P.R.]), and the NIH, NCI Small Business Innovation Research (grants R44CA221513 [M.D.] and R44CA246991 [P.Z.]).

Authorship

Contribution: J. Magenau, S.A., M.D., S.D., M.-J.Z., Y.L., P.Z., and P.R. substantially contributed to conception, design, or planning of the study; J. Magenau, J.U., M.M.R., A.P., S.A., M.G., J. Maciejewski, and L.J.B. substantially contributed to acquisition of the data; J. Magenau, S.S.F., T.B., B.B., C.D., S.D., and L.J.B. substantially contributed to data analysis; S.J., S.S.F., T.B., S.L., C.D., S.D., M.-J.Z., L.J.B., Y.L., and P.R. substantially contributed to interpretation of the results; J. Magenau and P.R. substantially contributed to drafting the manuscript; and all authors substantially contributed to critically reviewing or revising the manuscript for important intellectual content, reviewed the final version of the manuscript and are in agreement with its content and submission, have access to all relevant study data and related analyses and vouch for the completeness/accuracy of the presented data, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work and ensure that any questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work will be appropriately investigated and resolved.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J. Magenau has received research funding from Merck. S.A. has served as site principal investigator for AltruBio, Inc; CSL Behring, LLC; Equilibrium, Inc; and Incyte Corporation. S.L., B.B., and C.D. are employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co, Inc, Rahway, NJ, who may own stock and/or hold stock options in Merck & Co, Inc, Rahway, NJ. M.D. is a former employee of OncoImmune and had stock options from OncoImmune during the study period as an employee. S.D. is an employee of the National Marrow Donor Program, which supplied matched unrelated donor grafts to US transplantation centers participating in this study. Y.L. and P.Z. are founders and former part-time employees of OncoImmune; they held stocks and stock options from OncoImmune during the study period as employees; and they served as coinvestigators for a grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (R44CA221513). Y.L. received funding from the US Food and Drug Administration (R01FD006089-01). P.Z. received funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (R44CA246991). The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation of P.R. is Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX.

Correspondence: John Magenau, Transplantation and Cellular Therapy Program, University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center, 1500 E Medical Center Dr, SPC 5271, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-5271; email: johnmage@med.umich.edu.

References

Author notes

The data sharing policy, including restrictions, of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co, Inc, Rahway, NJ, USA, is available at http://engagezone.msd.com/ds_documentation.php. Requests for access to the clinical study data can be submitted through the Engage Zone website or via email to dataaccess@merck.com. The study protocol is included as a data supplement available with the online version of this article.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal