Key Points

The initial blood cells emerged in the common ancestor of animals inheriting a phagocytic program from unicellular organisms.

In murine hematopoiesis, CEBPα is commonly repressed by polycomb complexes to maintain nonphagocytic lineages.

Abstract

Blood cells are thought to have emerged as phagocytes in the common ancestor of animals followed by the appearance of novel blood cell lineages such as thrombocytes, erythrocytes, and lymphocytes, during evolution. However, this speculation is not based on genetic evidence and it is still possible to argue that phagocytes in different species have different origins. It also remains to be clarified how the initial blood cells evolved; whether ancient animals have solely developed de novo programs for phagocytes or they have inherited a key program from ancestral unicellular organisms. Here, we traced the evolutionary history of blood cells, and cross-species comparison of gene expression profiles revealed that phagocytes in various animal species and Capsaspora (C.) owczarzaki, a unicellular organism, are transcriptionally similar to each other. We also found that both phagocytes and C. owczarzaki share a common phagocytic program, and that CEBPα is the sole transcription factor highly expressed in both phagocytes and C. owczarzaki. We further showed that the function of CEBPα to drive phagocyte program in nonphagocytic blood cells has been conserved in tunicate, sponge, and C. owczarzaki. We finally showed that, in murine hematopoiesis, repression of CEBPα to maintain nonphagocytic lineages is commonly achieved by polycomb complexes. These findings indicate that the initial blood cells emerged inheriting a unicellular organism program driven by CEBPα and that the program has also been seamlessly inherited in phagocytes of various animal species throughout evolution.

Introduction

Among various lineage blood cells, such as erythrocytes and lymphocytes, phagocytes including macrophages and neutrophils have been thought to represent the most evolutionarily ancient blood cells because phagocytes can be found in any animal including organisms that are morphologically very simple multicellular like the sponge,1 whereas more lineage types can be seen in more complex animals.2-5 It has thus been speculated that the evolutionary initial blood cells emerged as phagocytes in the common ancestor of animals, and that various nonphagocyte lineages have evolved from the primordial phagocytes during evolution. Concerning this issue, we have demonstrated that the potential to produce phagocytes is retained in the early progenitors primed for erythroid, T- and B-cell lineages in murine hematopoiesis.6-10 Based on such findings, we have proposed that the retention of phagocyte potential in these lineage progenitors is a vestige of the phylogenic process, where each of these lineages has evolved from ancestral phagocytes.2,11 The vestige has also been found in other vertebrates: thrombocytes, erythrocytes, and B cells in shark, bony fish, and frog have phagocytic potential.12-14

One thing to note here is that such speculation can be made provided that all phagocytes have the same origin during phylogeny. However, genetic evidence supporting this model has been insufficient, and we can still argue a possibility of convergent evolution: phagocytes in different animal species have different origins. Furthermore, it remains to be clarified how the initial blood cells evolved. We can argue 2 possible cases: the first is that ancient animals have solely developed de novo programs for phagocytes, and the second is that they inherited a key program from ancestral unicellular organisms.

To address this issue, we decided to clarify whether a common program has been shared in phagocytes of various animal species and whether the program is also shared with a unicellular organism. To this end, we compared gene expression profiles in phagocytes and nonphagocytes of various animal species, and unicellular organisms.

Methods

Mice

Ert2Cre-Cdkn2a−/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bfl/fl, Ert2Cre-CAGflox-stop-GFP-Cdkn2a−/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bfl/fl and LckCre-Cdkn2a−/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bfl/fl mice were generated and maintained in our animal facility. All mice were maintained in specific pathogen-free conditions in our animal facility. All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Kyoto University animal experiment committee and approved by our institutional committee.

Tunicate

Ciona intestinalis (type A; also called Ciona robusta) adults were obtained from the National BioResource Project for Ciona.

Capsaspora

Capsaspora owczarzaki was maintained at 23°C in the ATCC 1034 medium as previously reported.15

Data and code availability

Public data of mouse in EMBL-EBI (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website) and data of mouse, tunicate, sponge, C. owczarzaki, Salpingoeca rosetta, and Creolimax fragrantissima in previous reports were analyzed15-23. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data of tunicate phagocytes and Ring1a/b knockout (KO) myeloid cells are available at DNA Data Bank of Japan database (DRA013007 and DRA014437).

Cross-species transcriptomic comparison

We identified homologs in Mus musculus, C. intestinalis, Amphimedon queenslandica, and C. owczarzaki using the OrthoFinder (supplemental Table 2).24 Homolog groups commonly conserved across the 4 species were selected and used for cross-species comparison (supplemental Table 3). Cross-species analysis of 6 species adding S. rosetta and C. fragrantissima was also performed (supplemental Tables 4-5).

Transcription factors (TFs) and phagocytosis-related genes

For selecting TFs and phagocytosis/lysosome-related genes, we used the AmiGO2 database (http://amigo.geneontology.org/amigo) (supplemental Table 6).

Isolation of mouse progenitors

Single-cell suspensions of the thymus or bone marrow (BM) were prepared and progenitors were isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Gating strategies are shown in supplemental Figure 1.

CEBPα and Ring1B encoding vectors

Codon-optimized DNA sequences of CEBPα and Ring1B were synthesized using GeneArt (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (supplemental Table 7).

Retrovirus production and transduction

CEBPα- and Ring1B-encoding vectors were transfected into the Plat-E cells (CosmoBio) and supernatants were harvested. For transduction, purified progenitors were resuspended with the supernatant, and were centrifuged for 90 minutes at 1000×g at 32°C.

Phagocytosis assay

pHrodo-green zymosan or Staphylococcus aureus beads (Invitrogen) were added to each culture. One hour later, the medium was replaced with phosphate-buffered saline and phagocytosis was observed using a fluorescence microscope.

RNA extraction and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Complementary DNA synthesis was performed using a SuperScript IV VILO Master Mix complementary DNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen). Real-time polymerase chain reaction was performed using PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and analyzed by StepOnePlus (Applied Biosystems).

RNA-seq of tunicate phagocytes and Ring1a/b KO myeloid cells

Libraries were prepared using SMART-Seq v4 Ultra Low Input RNA Kit for Sequencing (Takara) and Nextera XT DNA Library Prep kit (Illumina) and sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina).

In vitro deletion of Ring1b

BM chimera mice

Hemolyzed whole BM cells (2 × 106 cells) were IV injected into sublethally irradiated (4 Gy) Rag2−/− mice. For long term observation, 1 × 106 BM cells were transplanted with 1 × 106 competitor cells.

Statistical analysis

Survival rates were estimated using Kaplan-Meier methods and compared using log-rank tests. Continuous and categorical variables were compared using 2-tailed t tests and Fisher exact test, respectively.

Further experimental details are provided in supplemental methods.

Results

Phagocytes of mouse, tunicate, and sponge are transcriptionally similar to a unicellular organism

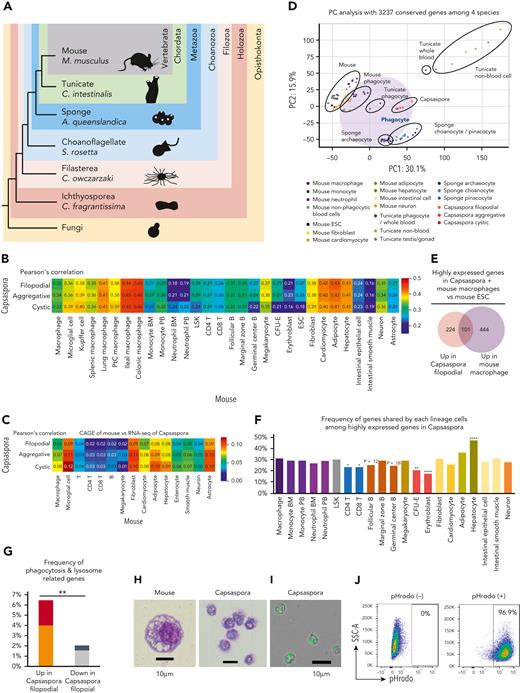

We compared gene expression profiles of various lineage or stage cells among 4 species: mouse (M. musculus), tunicate (C. intestinalis), sponge (A. queenslandica), and C. owczarzaki, a unicellular organism (hereafter Capsaspora) (Figure 1A). Among invertebrates, we selected tunicate and sponge because tunicate belongs to chordates and is close to vertebrates, whereas sponge is the animal oldest and farthest from vertebrates.27,28 Among unicellular organisms, Capsaspora was selected because it is phylogenetically close to animals, forming a clade termed Holozoa together with Metazoa (Figure 1A).29-31 We first searched homologs conserved among the 4 species and 3237 homolog groups were identified; 5911 genes in mouse, 4031 genes in tunicate, 5443 genes in sponge, and 4096 genes in Capsaspora were assigned to the 3237 homolog groups. Then, gene expression profiles were compared based on the homolog groups (supplemental Figure 2A). As expected, mouse, tunicate, sponge, and Capsaspora were very different form each other (supplemental Figure 2B). Among blood cells, macrophages were more similar to Capsaspora than nonphagocytic cells were (Figure 1C-D). Macrophages were also more similar to Capsaspora than neutrophils, in line with the fact that neutrophils with multilobulated nuclei are unique to vertebrates.32 In order to exclude batch effect between mouse data sets, comparison using a single data set of mouse cells with the cap analysis gene expression (CAGE) method was also performed (Figure 1C). In both the analysis with RNA-seq and CAGE data sets, macrophages, hepatocytes, fibroblasts, and adipocytes among mouse cells showed high similarity to Capsasapora (Figure 1B-C). Because hepatocytes, fibroblasts and adipocytes are known to have phagocytic potential,33-35 macrophages and these 3 lineage cells can be categorized as phagocytes. In principle component (PC) analysis, phagocytes of mouse and tunicate, sponge archaeocytes, which are known to have phagocytic potential,1 and Capsaspora showed similarity to each other (Figure 1D).

Phagocytes of mouse, tunicate, and sponge are transcriptionally similar to a unicellular organism. (A) Phylogenetic tree of mouse, tunicate, sponge, choanoflagellate, Capsaspora, Ichthyosporea, and fungi. (B-C) Heat map with Pearson correlation of various mouse cell lineages and Capsaspora. Gene expression profiles were compared among 3 stages of Capsaspora and 30 mouse lineages (B) or 15 lineages (C) based on 3237 conserved homologs. Transcriptome data examined by RNA-seq (B) or CAGE method (C) were analyzed. (D) PC analyses of various lineages or stages of 4 species: Capsaspora, sponge, tunicate, and mouse. Expression levels of 3237 conserved homologs were normalized and compared. (E) Venn diagrams with the number of highly expressed genes in Capsaspora filopodial stage or mouse macrophages compared with mouse ESCs. (F) Frequency of genes shared by various mouse cell lineages among 325 highly expressed genes in Capsaspora filopodial stage. Statistical significance of differences between macrophage and the other lineages are also shown. (G) Frequency of phagocytosis-related genes among 325 genes highly expressed in Capsaspora filopodial stage and 2252 genes low expressed in Capsaspora filopodial stage compared with mouse ESCs. Frequency of phagocytosis- and lysosome-related genes expressed higher in mouse macrophages than mouse ESCs are shown. Frequency of genes highly expressed in macrophages compared to mouse ESCs and nonphagocytic blood cells are shown in red and black, respectively. (H) Cytology of mouse phagocyte (left) and Capsaspora (right) was examined by Wright-Giemsa staining. (I-J) Phagocytic activity of Capsaspora was evaluated by engulfment of pHrodo-green beads (I), and frequency of phagocytic cells was evaluated by flow cytometry (J). Data are representative of 2 independent experiments. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ESCs, embryonic stem cells; PtC, peritoneal cavity.

Phagocytes of mouse, tunicate, and sponge are transcriptionally similar to a unicellular organism. (A) Phylogenetic tree of mouse, tunicate, sponge, choanoflagellate, Capsaspora, Ichthyosporea, and fungi. (B-C) Heat map with Pearson correlation of various mouse cell lineages and Capsaspora. Gene expression profiles were compared among 3 stages of Capsaspora and 30 mouse lineages (B) or 15 lineages (C) based on 3237 conserved homologs. Transcriptome data examined by RNA-seq (B) or CAGE method (C) were analyzed. (D) PC analyses of various lineages or stages of 4 species: Capsaspora, sponge, tunicate, and mouse. Expression levels of 3237 conserved homologs were normalized and compared. (E) Venn diagrams with the number of highly expressed genes in Capsaspora filopodial stage or mouse macrophages compared with mouse ESCs. (F) Frequency of genes shared by various mouse cell lineages among 325 highly expressed genes in Capsaspora filopodial stage. Statistical significance of differences between macrophage and the other lineages are also shown. (G) Frequency of phagocytosis-related genes among 325 genes highly expressed in Capsaspora filopodial stage and 2252 genes low expressed in Capsaspora filopodial stage compared with mouse ESCs. Frequency of phagocytosis- and lysosome-related genes expressed higher in mouse macrophages than mouse ESCs are shown. Frequency of genes highly expressed in macrophages compared to mouse ESCs and nonphagocytic blood cells are shown in red and black, respectively. (H) Cytology of mouse phagocyte (left) and Capsaspora (right) was examined by Wright-Giemsa staining. (I-J) Phagocytic activity of Capsaspora was evaluated by engulfment of pHrodo-green beads (I), and frequency of phagocytic cells was evaluated by flow cytometry (J). Data are representative of 2 independent experiments. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ESCs, embryonic stem cells; PtC, peritoneal cavity.

Next, we examined how frequently Capsaspora and various mouse cell lineages share highly expressed genes; number of genes expressed higher than ESCs were examined. Capsaspora and macrophages highly expressed 325 and 545 genes, respectively, and they shared 101 genes (Figure 1E). Macrophages shared more genes with Capsaspora than other blood cell lineages (Figure 1F and supplemental Figures 3-4). Hepatocytes also shared many genes with Capsaspora and shared more with macrophages among nonblood cells (supplemental Figures 3-4). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway analysis showed that lysosome-related genes were among genes shared by Capsaspora, macrophages, and hepatocytes (supplemental Figure 5). Gene ontology analysis using AmiGO2 database showed that 325 genes highly expressed in Capsaspora were more frequently phagocytosis/lysosome-related genes compared with the 2252 low expressed genes (Figure 1G). These data suggested that phagocytosis- and lysosome-related genes shape the similarity between Capsaspora and mouse phagocytes. In fact, Capsaspora cells showed mouse macrophage–like cytology with several vacuoles in the cytoplasm (Figure 1H) and robust phagocytic activity (Figure 1I-J). These data suggested that the transcriptional profile of phagocytes has been conserved from common ancestors of Capsaspora and animals.

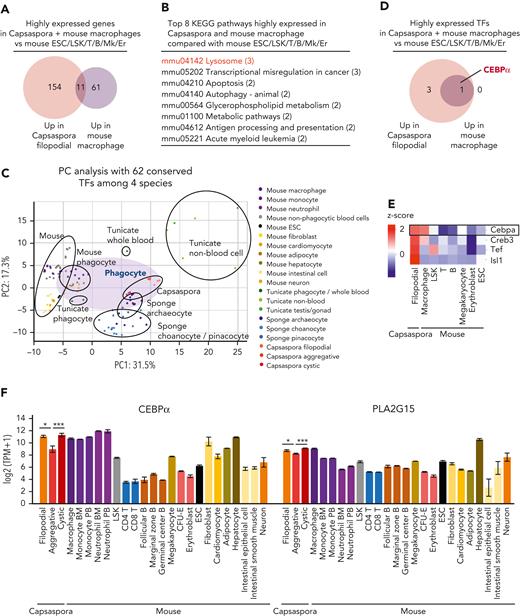

Phagocytes and a unicellular organism share a CEBPα-driven phagocytic program

Next, we compared gene expression profiles of Capsaspora and mouse macrophages with mouse ESCs and the nonphagocytic blood cells, Lin−Sca1+ckit+ cells, T cells, B cells, megakaryocytes, and erythroid cells. Eleven genes were highly expressed in both mouse macrophages and Capsaspora (Figure 2A and supplemental Figure 6A), and these 11 genes were lysosome related, suggesting that these genes contribute to phagocytosis in phagosome/lysosome pathway (Figure 2B and supplemental Figure 6B). Nine of the 11 genes were also highly expressed in hepatocytes (supplemental Figure 6A). Next, we attempted to reveal which TFs commonly play a key role in both Capsaspora and mouse phagocytes. We found that 62 TFs were conserved among the 4 species, and then we compared their expression levels. As with the comparison based on the 3237 conserved genes (Figure 1B-C), the comparison based on the 62 conserved TFs showed that mouse phagocytes were closer to Capsaspora than mouse nonphagocytes were (Figure 2C and supplemental Figure 7A-B). CEBPα was the sole TF highly expressed in both Capsaspora and mouse macrophages compared with mouse ESCs and nonphagocytic blood cells (Figure 2D-F and supplemental Figure 8A). Several regions of the CEBPα homologs, especially DNA binding bZIP domain, were conserved among the 4 species (supplemental Figure 9). Other TFs were also conserved among the 4 species (supplemental Figure 8B), and CEBPγ, another CEBP homolog, was also examined because we were not able to distinguish which was a functional CEBPα homolog in the phylogenetic tree (supplemental Figure 10). However, we found that expression levels of CEBPγ were not highly expressed in Capsaspora (supplemental Figure 8C). Expression levels of GATA1-6 homologs in Capsaspora, macrophages, and hepatocytes were lower than in megakaryocytes and erythroid cells (supplemental Figure 8D), and those of EBF1-4 were lower than B cells (supplemental Figure 8E). Relatively high expression levels of GATA and EBF families in Capsaspora and some mouse nonhematopoietic cells suggested that these TFs determine programs conserved among Capsaspora and mouse nonhematopoietic lineages.36-38 Although PU.1 and IRF are important in murine myeloid cells,39,40 their homologs were not detected in Capsaspora (supplemental Figure 8B). When gene expression levels were compared between the 3 stages of Capsaspora, CEBPα was expressed more in filopodial or cystic stages than in the aggregative stage (Figure 2F). Among the 11 genes highly expressed in mouse macrophages and Capsaspora, PLA2G15 was also expressed more in filopodial and cystic stages (Figure 2F and supplemental Figure 6A). PLA2G15 is a lysosomal protein and plays a role in host defense and efferocytosis by human phagocytes.41,42 These data suggested that a CEBPα-driven phagocytic program including PLA2G15 expression has been conserved between a unicellular organism and vertebrates.

Phagocytes and a unicellular organism share a CEBPα-driven phagocytic program. (A,D) Venn diagrams with the number of highly expressed genes (A) and TFs (D) in Capsaspora or mouse macrophages compared with mouse ESCs and nonphagocytic blood cells. (B) Top 8 KEGG pathways involved in the 11 genes highly expressed in Capsaspora and mouse macrophages compared with mouse ESCs and nonphagocytic blood cells. (C) PC analyses of various lineages or stages of 4 species: Capsaspora, sponge, tunicate, and mouse. Expression levels of 62 conserved TFs were compared. (E) Heatmap of scaled expression levels (z score) of TFs in Capsaspora, mouse macrophages, mouse ESCs, and mouse nonphagocytic blood cells. Four TFs expressed higher in Capsaspora or mouse macrophages than in mouse ESCs and nonphagocytic blood cells were selected. Expression levels were scaled among the 8 cell groups. (F) Expression levels of CEBPα homologs and PLA2G15 homologs in Capsaspora, and various mouse cell lineages. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance of differences between 3 stages of Capsaspora are shown, ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01. KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

Phagocytes and a unicellular organism share a CEBPα-driven phagocytic program. (A,D) Venn diagrams with the number of highly expressed genes (A) and TFs (D) in Capsaspora or mouse macrophages compared with mouse ESCs and nonphagocytic blood cells. (B) Top 8 KEGG pathways involved in the 11 genes highly expressed in Capsaspora and mouse macrophages compared with mouse ESCs and nonphagocytic blood cells. (C) PC analyses of various lineages or stages of 4 species: Capsaspora, sponge, tunicate, and mouse. Expression levels of 62 conserved TFs were compared. (E) Heatmap of scaled expression levels (z score) of TFs in Capsaspora, mouse macrophages, mouse ESCs, and mouse nonphagocytic blood cells. Four TFs expressed higher in Capsaspora or mouse macrophages than in mouse ESCs and nonphagocytic blood cells were selected. Expression levels were scaled among the 8 cell groups. (F) Expression levels of CEBPα homologs and PLA2G15 homologs in Capsaspora, and various mouse cell lineages. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance of differences between 3 stages of Capsaspora are shown, ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01. KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

We also performed cross-species analysis adding a choanoflagellate (S. rosetta) and Ichthyosporea (C. fragrantissima). In this analysis, phagocytes of various species also showed similarity to each other and to unicellular organisms (supplemental Figure 11A-C). In mouse cell lineages, macrophages and adipocytes showed high similarity to unicellular organisms (supplemental Figure 11B-C). Hgd was highly expressed in mouse macrophages, Capsaspora, and C. fragrantissima (supplemental Figure 11D). However, because both S. rosetta and C. fragrantissima lack CEBPα, no TFs highly expressed in all of mouse macrophages, Capsaspora, and C. fragrantissima were detected. Some important genes other than CEBPα may determine the similarity of these cells.

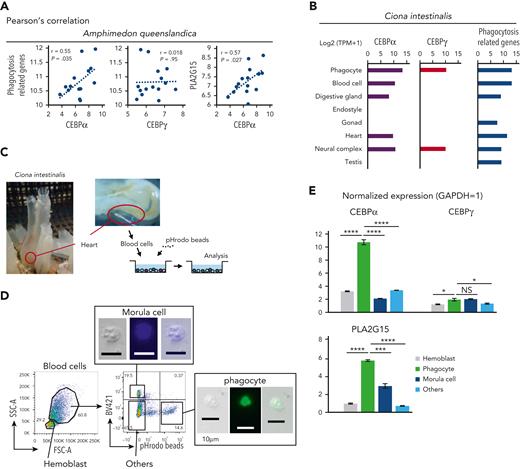

Tunicate and sponge phagocytes highly express CEBPα homologs

Next, we examined whether expression levels of CEBPα were different between phagocytes and nonphagocytic blood cells in sponge and tunicate. In sponges, we focused on archaeocytes, which behave like blood cells in that they circulate around the body cavity and have phagocytic potential.1 Analysis of archaeocytes showed that CEBPα expression levels were positively correlated with those of phagocytosis-related genes and PLA2G15, but CEBPγ levels were not (Figure 3A).

Tunicate and sponge phagocytes highly express CEBPα homologs. (A) Scatter plots of sponge archaeocytes with log2 (TPM + 1) values. The x-axes indicate sponge CEBPα and CEBPγ. The y-axes indicate total expression levels of phagocytosis-related genes and PLA2G15 (CEBPα homologs were excluded from phagocytosis-related genes in these analyses). (B) Expression levels with log2 (TPM + 1) values of CEBPα, CEBPγ, and phagocytosis-related genes in tunicate. Transcriptome data of phagocytes were examined by RNA-seq, and data of the other lineages were based on expressed sequence tag counts obtained from the Ghost Database (http://ghost.zool.kyoto-u.ac.jp/cgi-bin/gb2/gbrowse/kh/). (C) Blood cells of tunicate was aspirated by cardiac puncture. Collected blood cells were incubated with pHrodo beads and analyzed by flow cytometry. (D) Blood cells of tunicate were analyzed by flow cytometry based on their size, autofluorescence, and fluorescence of engulfed beads. (E) Normalized expression levels (Gapdh = 1) of CEBPα, CEBPγ, and PLA2G15 in various lineage blood cells of tunicate were evaluated by RT-qPCR. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean. ∗P < .05, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Tunicate and sponge phagocytes highly express CEBPα homologs. (A) Scatter plots of sponge archaeocytes with log2 (TPM + 1) values. The x-axes indicate sponge CEBPα and CEBPγ. The y-axes indicate total expression levels of phagocytosis-related genes and PLA2G15 (CEBPα homologs were excluded from phagocytosis-related genes in these analyses). (B) Expression levels with log2 (TPM + 1) values of CEBPα, CEBPγ, and phagocytosis-related genes in tunicate. Transcriptome data of phagocytes were examined by RNA-seq, and data of the other lineages were based on expressed sequence tag counts obtained from the Ghost Database (http://ghost.zool.kyoto-u.ac.jp/cgi-bin/gb2/gbrowse/kh/). (C) Blood cells of tunicate was aspirated by cardiac puncture. Collected blood cells were incubated with pHrodo beads and analyzed by flow cytometry. (D) Blood cells of tunicate were analyzed by flow cytometry based on their size, autofluorescence, and fluorescence of engulfed beads. (E) Normalized expression levels (Gapdh = 1) of CEBPα, CEBPγ, and PLA2G15 in various lineage blood cells of tunicate were evaluated by RT-qPCR. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean. ∗P < .05, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

We also examined tunicate blood cells and their expression of CEBP homologs and phagocytosis-related genes. CEBPα and phagocytosis-related genes were highly expressed in the blood cells, especially in phagocytes, but CEBPγ was not (Figure 3B). In order to investigate whether CEBPα is differently expressed among various blood lineage cells in tunicate, we collected blood cells from tunicates (Figure 3C). The blood cells were then sorted into 4 fractions based on characteristics of (1) small size (hemoblasts), (2) autofluorescence (morula cells), (3) fluorescence of engulfed beads (phagocytes), and (4) negative for these features (other blood cells) (Figure 3D). We found that the expression levels of CEBPα and PLA2G15 were remarkably higher in phagocytes compared to other lineages of blood cells, whereas the expression level of CEBPγ was not or only slightly (Figure 3E). These data may indicate that, in both sponge and tunicate, CEBPα commonly exert a phagocyte program.

Function of CEBPα to drive the phagocyte program has been conserved from a unicellular organism

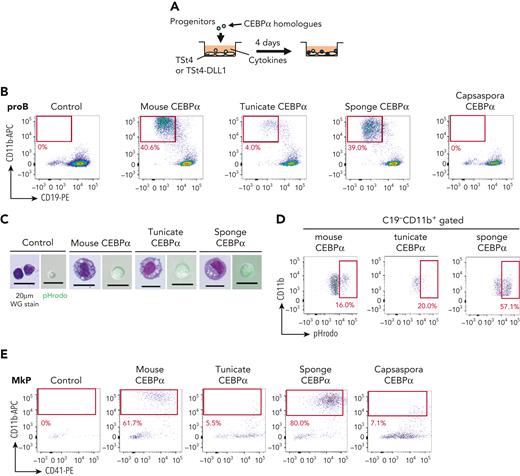

Next, we asked whether CEBPα of the tunicate, sponge, and Capsaspora has a function similar to mouse CEBPα, the enforced expression of which has been shown to convert T and B cells into phagocytes.43-46 First, mouse pro-B cells were transduced with CEBPα of mouse, tunicates, sponge, or Capsaspora (Figure 4A). CEBPα of tunicate and sponge, as well as mouse CEBPα, converted these B progenitors into cells that express CD11b, whereas the CEBPα of Capsaspora, and CEBPγ of sponge and Capsaspora, did not (Figure 4B and supplemental Figure 12A). The majority of the CD11b+ cells induced by either tunicate or sponge CEBPα looked like macrophages and showed efficient phagocytic activity (Figure 4C-D). D-J–rearranged IgH genes were present in the generated CD11b+ cells (supplemental Figure 12B), indicating that they were derived from pro-B cells. In order to clarify whether CEBPα of Capsaspora has the potential to drive the phagocyte program, we further examined other lineage progenitors. MkPs, ErPs, and DN3 T-cell progenitors were examined. CEBPα of Capsaspora as well as that of mouse, tunicate, and sponge converted MkPs into CD11b+ phagocytes, whereas CEBPγ of Capsaspora did not (Figure 4E-G and supplemental Figure 12C), indicating that Capsaspora CEBPα has the potential to drive the phagocytic program. We also found that CEBPα of mouse, tunicate, sponge, and Capsaspora converted ErPs into CD11b+ cells (Figure 4H and supplemental Figure 12D). DN3 T-cell progenitors were converted into CD11b+ cells by mouse and sponge CEBPα but not by the tunicate and Capsaspora homologs (Figure 4I and supplemental Figure 12E).

Function of CEBPα to drive the phagocyte program has been conserved from a unicellular organism. (A) Mouse CEBPα and its homologs from tunicate, sponge, and Capsaspora were transduced into pro-B cells, which were analyzed by flow cytometry 4 days later. (B,E,H-I) pro-B cells (B), MkPs (E), ErPs (H) and DN3 cells (I) were transduced with mouse, tunicate, sponge, or Capsaspora CEBPα and then examined by flow cytometry for the indicated lineage markers. Data are representative of 2 to 4 independent experiments. (C,F) The CD11b+ cells generated by transduction with various CEBPα homologs into pro-B cells (C) and MkPs (F) were sorted and their cytology was examined by Wright-Giemsa staining (left). Their phagocytic activity was evaluated by engulfment of pHrodo-green beads (right). (D,G) Phagocytic activities of the generated CD11b+ cells from pro-B cells (D) and MkPs (G) was evaluated by flow cytometry. (J) Wright-Giemsa stain of neutrophil-like cells with ring-shaped or multilobulated nuclei generated by transduction with mouse CEBPα into pro-B cells. (K) Frequency of cell types evaluated by cytology with Wright-Giemsa staining. Cells (n = 100) transduced with mouse, tunicate, or sponge CEBPα were examined. (L) Relative expression of neutrophil-associated genes in pro-B cells 2 days after CEBPα transduction. Relative expression levels (day 0 = 1) with 2−ΔΔCT values normalized with β-actin were shown. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean of 3 replicates. ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001. DN3, double-negative 3; ErPs, erythroid progenitors; MkPs, megakaryocyte progenitors.

Function of CEBPα to drive the phagocyte program has been conserved from a unicellular organism. (A) Mouse CEBPα and its homologs from tunicate, sponge, and Capsaspora were transduced into pro-B cells, which were analyzed by flow cytometry 4 days later. (B,E,H-I) pro-B cells (B), MkPs (E), ErPs (H) and DN3 cells (I) were transduced with mouse, tunicate, sponge, or Capsaspora CEBPα and then examined by flow cytometry for the indicated lineage markers. Data are representative of 2 to 4 independent experiments. (C,F) The CD11b+ cells generated by transduction with various CEBPα homologs into pro-B cells (C) and MkPs (F) were sorted and their cytology was examined by Wright-Giemsa staining (left). Their phagocytic activity was evaluated by engulfment of pHrodo-green beads (right). (D,G) Phagocytic activities of the generated CD11b+ cells from pro-B cells (D) and MkPs (G) was evaluated by flow cytometry. (J) Wright-Giemsa stain of neutrophil-like cells with ring-shaped or multilobulated nuclei generated by transduction with mouse CEBPα into pro-B cells. (K) Frequency of cell types evaluated by cytology with Wright-Giemsa staining. Cells (n = 100) transduced with mouse, tunicate, or sponge CEBPα were examined. (L) Relative expression of neutrophil-associated genes in pro-B cells 2 days after CEBPα transduction. Relative expression levels (day 0 = 1) with 2−ΔΔCT values normalized with β-actin were shown. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean of 3 replicates. ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001. DN3, double-negative 3; ErPs, erythroid progenitors; MkPs, megakaryocyte progenitors.

We then examined how functionally similar the CEBPα homologs were. CEBPα is known to play roles in the differentiation of mouse neutrophils, and indeed, mouse CEBPα converted pro-B cells into neutrophil-like cells with ring-shaped or multilobulated nuclei, whereas CEBPα of tunicate and sponge hardly did so (Figure 4J-K). The expression levels of various genes were also compared between pro-B cells transduced with the mouse or sponge CEBPα, which converted pro-B cells into phagocytes to a similar extent (Figure 4B). To examine the direct consequence of Cebpa gene expression, we collected the cells on day 2, when they had not yet begun to express CD11b (supplemental Figure 12F-G). Sponge CEBPα upregulated phagocyte-associated genes to the same extent as mouse CEBPα, but mouse CEBPα was superior to sponge CEBPα in inducing expression of neutrophil-associated genes and in repressing B cell–associated genes (Figure 4L and supplemental Figure 12H).

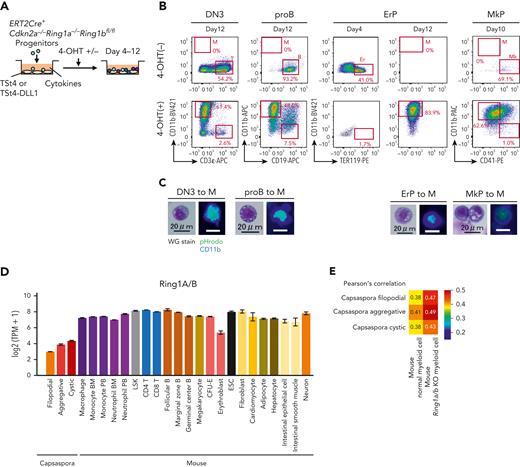

Polycomb-mediated suppression of CEBPα is required for maintenance of various hematopoietic lineages in mouse

In mouse blood cells, CEBPα functions as master regulators of phagocytes, or myeloid cells in other words, having the potential to convert nonphagocytic lineage progenitors into myeloid cells,43-50 implying that CEBPα must be strictly repressed for maintenance of nonphagocytic lineages. We attempted to reveal how CEBPα is repressed in nonphagocytic lineage cells, and hypothesized that the polycomb complex, one of major epigenetic repressors,51 plays a role in suppression of the phagocyte program. We focused on Ring1A and B, which are catalytic components of polycomb complexes.52 Expression levels of Ring1B were higher in nonphagocytic lineages than in myeloid cells reciprocally to those of CEBPα (supplemental Figure 13A-B). By analyzing published data, the Cebpa locus encoding CEBPα was found to be heavily marked with H3K27me3 in DN3 cells, pro-B cells, ErPs, and MkPs, but not in myeloid cells (supplemental Figure 13C). In contrast, Spi1 locus encoding PU.1 was found not to be marked with H3K27me3 (supplemental Figure 13D). We also observed Ring1B binding at the Cebpa locus (supplemental Figure 13E). In order to confirm that CEBPα is suppressed by polycomb, we deleted Ring1b by using 4-OHT in progenitors of each lineage from Ert2Cre -Cdkn2a−/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bfl/fl mice (supplemental Figure 13F). In this experiment, we used Cdkn2a−/− background mice because Ring1a/b KO may cause derepression of Cdkn2a, leading to apoptosis of Ring1a/b-deleted cells.53 Upon deletion of Ring1b, expression levels of CEBPα were remarkably elevated within a few days in all lineages (supplemental Figure 13G). These data indicate that polycomb complexes commonly suppress CEBPα in various nonphagocytic lineages.

Next, we examined whether polycomb-mediated CEBPα suppression is physiologically important. We made BM chimera mice by transplantation of BM cells from Ert2Cre-CAGflox-stop-GFP-Cdkn2a−/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bfl/fl mice into sublethally irradiated Rag2−/− mice. Six weeks after transplantation, Ring1b was deleted by administration of tamoxifen, and mice were analyzed 2 weeks later (Figure 5A). The number of thymocytes, double-positive cells, DN cells, and DN3 cells in the green fluorescent protein–positive (GFP+) fraction was decreased, whereas that of DN1 cells was increased in the Ring1a/b KO BM chimera mice (Figure 5B,E and supplemental Figure 14A-B,E). We also found a decrease in the number of pro-B cells and an increase of the number of B-1 progenitors, defined as CD19+B220− cells (Figure 5C,F and supplemental Figure 14F). Lin−Sca1+ckit+ cells including hematopoietic stem cells were decreased, whereas Lin−Sca1−ckit+ cells were increased (supplemental Figure 14C,G). The proportion of ErPs and MkPs was decreased, whereas common myeloid progenitors were increased, and megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors were intact (Figure 5D,G and supplemental Figure 14D,H). Because hematopoiesis of the BM chimera mice was severely impaired, they died within a few months (Figure 5H).

Polycomb-mediated suppression of CEBPα is required for maintenance of various hematopoietic lineages in mouse. (A,I) Experimental procedure for conditional inactivation of polycomb function. BM cells of Ert2Cre-CAGflox-stop-GFP-Cdkn2a−/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bfl/fl mice or Ert2Cre-CAGflox-stop-GFP-Cdkn2a−/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bfl/+ mice were transplanted without (A) or with (I) competitor cells by IV injection into sublethally irradiated Rag2−/− mice. Six weeks later, the transplanted mice were administrated tamoxifen intraperitoneally to delete Ring1b in blood cells. Two (A) or 8 (I) weeks after Ring1b deletion, mice were sacrificed and analyzed. (B-D) Flow cytometric profiles of GFP+ thymocytes (B) and GFP+ BM cells (C-D). Upper and lower panels show data of control (Δ/+; Cdkn2a−/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bΔ/+, n = 5 in panels B and D, and n = 3 in panel C) and Ring1a/b KO (Δ/Δ; Cdkn2a−/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bΔ/Δ, n = 6 in panel B, n = 3 in panel C, and n = 5 in panel D) mice, respectively. (E-G) Number of GFP+ DN3 cells (E), pro-B cells (F), and ErPs and MkPs (G) of control (black) and Ring1a/b KO (red) mice. (H) Survival curve with Kaplan-Meier plots after BM transplantation to sublethally irradiated Rag2−/− mice. Blue and red lines show survival curve of control (Cdkn2a−/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bΔ/+, n = 4) and Ring1a/b KO (Cdkn2a−/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bΔ/Δ, n = 3) mice, respectively. Statistical significance of differences between the survival rates were calculated with the log-rank test. (J) Flow cytometric profiles of whole BM cells of control (n = 4), Ring1a/b KO in Cdkn2a−/− background (n = 4), and Ring1a/b KO in Cdkn2a+/− background (n = 3) mice with competitor cells. (K) Percentage of myeloid cells, RBCs, T cells, and B cells among GFP+ BM cells of control (blue) and Ring1a/b KO (red) mice with competitor cells. (L) Wright-Giemsa stain of BM smears obtained from control and Ring1a/b KO mice with competitor cells. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Polycomb-mediated suppression of CEBPα is required for maintenance of various hematopoietic lineages in mouse. (A,I) Experimental procedure for conditional inactivation of polycomb function. BM cells of Ert2Cre-CAGflox-stop-GFP-Cdkn2a−/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bfl/fl mice or Ert2Cre-CAGflox-stop-GFP-Cdkn2a−/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bfl/+ mice were transplanted without (A) or with (I) competitor cells by IV injection into sublethally irradiated Rag2−/− mice. Six weeks later, the transplanted mice were administrated tamoxifen intraperitoneally to delete Ring1b in blood cells. Two (A) or 8 (I) weeks after Ring1b deletion, mice were sacrificed and analyzed. (B-D) Flow cytometric profiles of GFP+ thymocytes (B) and GFP+ BM cells (C-D). Upper and lower panels show data of control (Δ/+; Cdkn2a−/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bΔ/+, n = 5 in panels B and D, and n = 3 in panel C) and Ring1a/b KO (Δ/Δ; Cdkn2a−/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bΔ/Δ, n = 6 in panel B, n = 3 in panel C, and n = 5 in panel D) mice, respectively. (E-G) Number of GFP+ DN3 cells (E), pro-B cells (F), and ErPs and MkPs (G) of control (black) and Ring1a/b KO (red) mice. (H) Survival curve with Kaplan-Meier plots after BM transplantation to sublethally irradiated Rag2−/− mice. Blue and red lines show survival curve of control (Cdkn2a−/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bΔ/+, n = 4) and Ring1a/b KO (Cdkn2a−/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bΔ/Δ, n = 3) mice, respectively. Statistical significance of differences between the survival rates were calculated with the log-rank test. (J) Flow cytometric profiles of whole BM cells of control (n = 4), Ring1a/b KO in Cdkn2a−/− background (n = 4), and Ring1a/b KO in Cdkn2a+/− background (n = 3) mice with competitor cells. (K) Percentage of myeloid cells, RBCs, T cells, and B cells among GFP+ BM cells of control (blue) and Ring1a/b KO (red) mice with competitor cells. (L) Wright-Giemsa stain of BM smears obtained from control and Ring1a/b KO mice with competitor cells. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

To evaluate the long-term effect of Ring1a/b KO in blood cells, we performed transplantation of Ring1a/b KO BM cells with competitor BM cells, which should contribute normal hematopoiesis (Figure 5I). Eight weeks after deletion of Ring1b, almost all GFP+Ring1a/b KO cells became CD11b+ myeloid cells (Figure 5J-K). Furthermore, the BM of Ring1a/b KO mice was occupied with myeloid cells and exhibited an anemic appearance, and the mice died within 3 months (Figure 5L and supplemental Figure 15A-D). These GFP+Ring1a/b KO myeloid cells expressed CD34 and looked like immature blasts (supplemental Figure 15E-F). Various lineage progenitors of thymocytes and BM cells, including competitor cells, were decreased, indicating that Ring1a/b KO myeloid cells were transformed into leukemic blasts and disturbed normal hematopoiesis (supplemental Figure 15G-L). We then examined whether sole Ring1a/b KO without Cdkn2a KO causes leukemia. We found that mice with Cdkn2a+/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bΔ/Δ cells did not develop leukemia, and GFP+ cells disappeared (Figure 5J and supplemental Figure 15D). This result suggested that the KO of Ring1a/b, leaving Cdkn2a+/− still present, led to an overexpression of Cdkn2a, resulting in apoptosis of KO cells as previously reported in the T cell–specific KO case.53

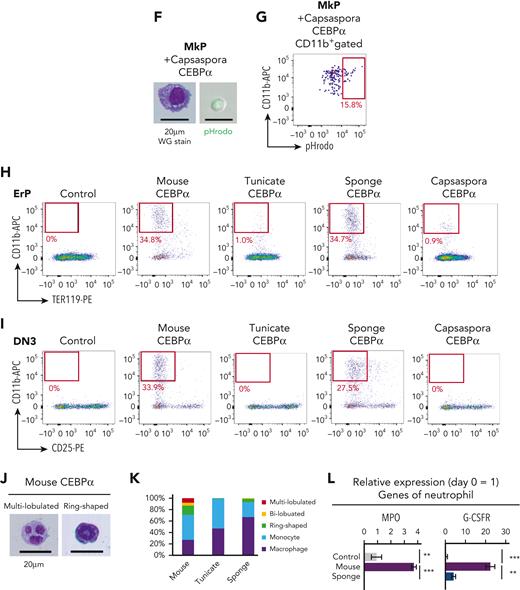

Various lineage progenitors were reverted into the primordial lineage of phagocytes by Ring1a/b KO

In BM chimera mice, we showed that the number of various lineage progenitors was decreased, whereas that of myeloid cells was increased (Figure 5). Next, we tested whether cell fate conversion from each of the lineage progenitors into myeloid cells had occurred. First, we found that the myeloid cells from the Ring1a/b KO mice carried rearranged IgH genes but those of control mice showed no rearrangements (supplemental Figure 16A). Among 8 Ring1a/b KO BM chimera mice examined, 5 carried IgH-rearranged myeloid cells. These data indicate that B cells were converted into myeloid cells in vivo. In order to examine whether various lineage progenitors are converted into myeloid cells by Ring1a/b KO, DN3 cells, pro-B cells, ErPs, and MkPs of Ert2Cre-Cdkn2a−/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bfl/fl mice were cultured with or without 4-OHT (Figure 6A). Because these progenitors had already been determined to their respective lineages, control cells maintained their lineage identity (Figure 6B). In contrast, by deletion of Ring1b, these progenitors gave rise to CD11b+ macrophage-like cells (Figure 6B-C). DN3- and pro-B–derived myeloid cells harbored V-DJ–rearranged TCR genes and IgH genes, respectively, confirming that they had originated from T and B lineage progenitors (supplemental Figure 16B-C). We also observed lineage conversion from pro–B cells into myeloid cells via B-1 stage in vitro (supplemental Figure 16D-E), which was consistent with the increase in number of B-1 cells in BM chimera mice (Figure 5C and supplemental Figure 14F). We previously reported that Ring1a/b KO by LckCre converted T cells into B cells.53 We again analyzed LckCre-Cdkn2a−/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bfl/fl mice and found that Ring1a/b KO DN3 cells expressed CD19 but some of them were B-1 phenotype lacking B220 expression (supplemental Figure 16F). In addition, DN3 cells of LckCre mice were converted into myeloid cells via B lineage cells carrying rearranged IgH and Tcrb genes (supplemental Figure 16G-J). Although Ring1b deletion converted nonphagocytic lineage cells into phagocytes, Ring1B overexpression did not convert phagocytes into nonphagocytic lineage cells (supplemental Figure 17A-E), indicating that polycomb complexes play a role in the maintenance of nonphagocytic lineages but not in induction of nonphagocytic lineages.

Various lineage progenitors were reverted into the primordial lineage of phagocytes by Ring1a/b KO. (A) DN3 cells, pro–B cells, ErPs, and MkPs isolated from Ert2Cre-Cdkn2a−/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bfl/fl mice were cocultured with TSt4 or TSt4-DLL1 cells for 4 to 12 days with or without 4-OHT in the presence of 10 ng/mL of stem cell factor, Flt3-L, interleukin 1α (IL-1α), IL-3, IL-7, tumor necrosis factor α, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. For ErPs and MkPs, 2 U/mL of erythropoietin and 50 ng/mL of thrombopoietin were added, respectively. (B) Flow cytometric profiles of the cultured cells. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) Cytology of the generated CD11b+ cells was examined by Wright-Giemsa staining (left), and their phagocytic activity was evaluated by pHrodo-green beads with CD11b-BV421 staining (right). (D) Expression levels of Ring1A/B homologs in Capsaspora and various mouse cell lineages. (E) Heat map with Pearson correlation of mouse normal and Ring1a/b KO myeloid cells and Capsaspora.

Various lineage progenitors were reverted into the primordial lineage of phagocytes by Ring1a/b KO. (A) DN3 cells, pro–B cells, ErPs, and MkPs isolated from Ert2Cre-Cdkn2a−/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bfl/fl mice were cocultured with TSt4 or TSt4-DLL1 cells for 4 to 12 days with or without 4-OHT in the presence of 10 ng/mL of stem cell factor, Flt3-L, interleukin 1α (IL-1α), IL-3, IL-7, tumor necrosis factor α, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. For ErPs and MkPs, 2 U/mL of erythropoietin and 50 ng/mL of thrombopoietin were added, respectively. (B) Flow cytometric profiles of the cultured cells. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) Cytology of the generated CD11b+ cells was examined by Wright-Giemsa staining (left), and their phagocytic activity was evaluated by pHrodo-green beads with CD11b-BV421 staining (right). (D) Expression levels of Ring1A/B homologs in Capsaspora and various mouse cell lineages. (E) Heat map with Pearson correlation of mouse normal and Ring1a/b KO myeloid cells and Capsaspora.

Lastly, we found that expression levels of Ring1A/B homologs were low in Capsaspora (Figure 6D), and Ring1a/b KO myeloid cells were more similar with Capsaspora than normal myeloid cells (Figure 6E). These data suggested that Ring1a/b KO reverted mouse cells toward a primordial status close to Capsaspora, and that Ring1A/B has played a role in acquiring new lineages in evolution.

Discussion

Animals evolved from unicellular organisms,29,30,54-57 and Capsaspora, which is known to exhibit typical filopodial features, is phylogenetically close to animals.15,20,58-61 The present study enabled us to envisage that the phenotype of Capsaspora represents the origin of phagocytes in animals. We showed that Capsaspora has phagocytic potential and exhibit gene expression profiles similar to phagocytes of animals characterized by high CEBPα expression. Furthermore, we showed that CEBPα homologs converted murine nonphagocyte progenitors into phagocytes.

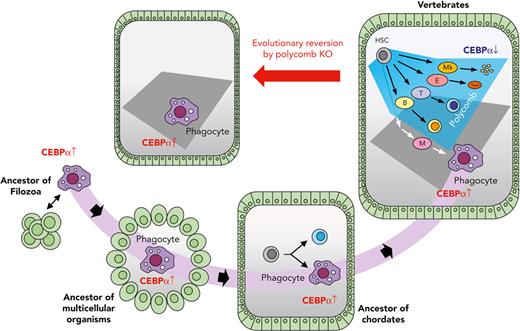

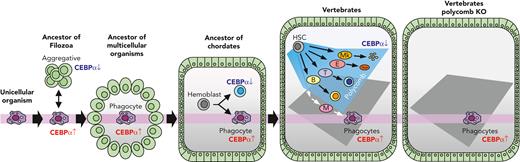

Here, we propose the following scenario in the evolutionary history of blood cells: when a unicellular ancestor came to form a multicellular organism, a body cavity structure surrounded by epithelium would have formed. In such a situation it would have been advantageous if the organism had an ancestral type of cell in the cavity that was able to patrol the cavity to eliminate pathogens and dead cells by phagocytosis. Thus, the multicellular organism should have survived after succeeding in holding such cells by inheriting the ancestral program for phagocytic characteristics driven by CEBPα, bringing about the birth of the initial blood cells (Figure 7).

Schematic illustration for the evolution of blood cells. A component of the unicellular organism phenotype has been seamlessly inherited as phagocytes in multicellular animals. Vertebrates acquired various lineage blood cells by suppressing CEBPα using polycomb complexes. When polycomb function was impaired, hematopoiesis was reverted into a primitive one with phagocytes alone.

Schematic illustration for the evolution of blood cells. A component of the unicellular organism phenotype has been seamlessly inherited as phagocytes in multicellular animals. Vertebrates acquired various lineage blood cells by suppressing CEBPα using polycomb complexes. When polycomb function was impaired, hematopoiesis was reverted into a primitive one with phagocytes alone.

Thereafter, megakaryocyte, erythroid, T-cell, and B-cell lineages were generated during the evolution of animals. An early study reported that the sea urchin has blood cells with clotting function,62 so it is probable that the megakaryocyte lineage had been segregated at an earlier stage than echinoderms in the branch of Deuterostomia. An early branch of the megakaryocyte lineage in the hematopoietic differentiation pathway63 should reflect its evolutionary early segregation. In chordates, at the level of protochordates, blood cells are segregated into several lineages,5,64 and, in accordance with this finding, we showed that CEBPα is specifically expressed in the phagocytic blood cells. In the evolutionary history of vertebrates, before branching into jawless and jawed fish, the erythroid and lymphoid lineages should have arisen, because both jawless and jawed fish have these 2 cell types.65-67 In vertebrate hematopoiesis, CEBPα is specifically expressed in phagocytes, and it is now clear, based on this study, that repression of CEBPα to maintain nonphagocytic lineages is commonly achieved by polycomb complexes in vertebrates (Figure 7). The findings that Ring1a/b KO leads to leukemogenesis in absence of Cdkn2a further suggest that Cdkn2a has been employed for secure hematopoiesis, so that dysfunction of the polycomb complex results in apoptosis (Figure 5J and supplemental Figure 15D).

In vertebrate hematopoiesis, phagocytic blood lineages and CEBPα has also been diverged. It is known that quadruplication of the genome took place in an ancestor of vertebrates after segregation from tunicates,68,69 and vertebrates have quadruple CEBPα genes: CEBPα, CEBPβ, CEBPδ, and CEBPε. Such quadruplication of CEBPα has enabled vertebrates to acquire various phagocytic blood cells; for example, CEBPδ and CEBPε are important in granulocyte.46,70,71 Homologs of other TFs essential to myeloid cells in vertebrates, such as PU.1 and IRF, were not found in Capsaspora (supplemental Figure 8B). It is probable that these genes have emerged after multicellular organisms had evolved from unicellular organisms and have enabled vertebrates to acquire another phagocytic blood cells, for example, dendritic cells.

We further argue whether findings in this study shows some implications regarding multicellularization in ancestral unicellular organisms. Phagocytosis itself is common among some unicellular eukaryotes,72,73 but CEBP homologs has been found only in Filozoa.60 Acquisition of CEBPα in ancestral Filozoan organisms, together with cis-regulatory system,61 should have enabled them to regulate a phagocytic program. Lower expression of CEBPα homolog and higher expression of Ring1A/B homologs in the aggregative stage of Capsaspora than the filopodial stage (Figures 2F and 6D) suggested that polycomb complexes have played a role in repressing CEBPα and a phagocytic program in ancestral Filozoa. It is tempting to speculate that polycomb-mediated CEBPα repression has contributed to aggregation and multicellularization.

Of note was that hepatocytes, fibroblasts, and adipocytes, in which CEBPα is also known to be expressed, showed similarity to Capsaspora. Because these cells are known to have phagocytic potential, it is likely that these cells also inherited Capsaspora program driven by CEBPα. Further study is required to unveil whether such programs have been seamlessly maintained in the evolutionary history of these cells. Another unsolved issue is the evolutionary history of Protostomia blood cells. It remains to be clarified whether they have seamlessly inherited the CEBPα-driven program or have inherited an alternative program driven by different TFs.

Overall, this study has provided insight into the origin of blood cells in the animal kingdom, where the primary phagocytes in the ancestor of animals arose by activating the CEBPα-driven phagocytic program inherited from a unicellular organism, and has clarified the molecular mechanism by which the phagocytic program is suppressed to maintain nonphagocytic lineage cells in vertebrate hematopoiesis, that is, polycomb-mediated epigenetic suppression of CEBPα.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Shimon Sakaguchi (Osaka University) for kindly providing Rag2−/− mice; Haruhiko Koseki (RIKEN) and Miguel Vidal (Centro de Investigaciones Biologicas) for kindly providing Ert2Cre mice and Cdkn2a−/−Ring1a−/−Ring1bfl/fl mice; Jun-ichi Miyazaki (Osaka University) for kindly providing CAGflox-stop-GFP mice; Ellen V. Rothenberg (Caltech) and Hiroyuki Hosokawa (Tokai University) for kindly providing the pMXs-IRES-hNGFR vector; and Peter Burrows (University of Alabama at Birmingham) for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by funds from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI, Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (JP15H04743), and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (JP 19H05747). LiMe Office of Director’s Research Grants 2022 (No. 6) also supported this work.

Authorship

Contribution: Y. Nagahata and H.K. conceived and designed the project; Y. Nagahata, K.M., T.I., Y. Nishimura, and S.K. designed and optimized experimental methodologies using mice, Y. Nagahata and Y.S. did so using tunicates, and Y. Nagahata and H.S. did so using Capsaspora; Y. Nagahata, H.S., and Y.S. performed experiments; Y. Nagahata, H.S., and Y.S. analyzed the data; T.K., Y. Nannya, S.O., and A.T.-K gave advice in performing the experiments; and Y. Nagahata., K.M., and H.K. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Hiroshi Kawamoto, 53 Kawahara-cho, Shogoin, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8507, Japan; e-mail: kawamoto@infront.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

References

Author notes

Expression levels of homologs were found in supplemental Tables 3 and 5. Other sources were also available with the online version of this article.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal