Key Points

Multiple independent but recurring genetic and epigenetic changes drive venetoclax resistance, with marked NF-κB activation ubiquitous.

NF-κB activation is apparent within the first year of therapy, and most changes in CLL cells are sustained by ongoing venetoclax therapy.

Abstract

Venetoclax (VEN) inhibits the prosurvival protein BCL2 to induce apoptosis and is a standard therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), delivering high complete remission rates and prolonged progression-free survival in relapsed CLL but with eventual loss of efficacy. A spectrum of subclonal genetic changes associated with VEN resistance has now been described. To fully understand clinical resistance to VEN, we combined single-cell short- and long-read RNA-sequencing to reveal the previously unappreciated scale of genetic and epigenetic changes underpinning acquired VEN resistance. These appear to be multilayered. One layer comprises changes in the BCL2 family of apoptosis regulators, especially the prosurvival family members. This includes previously described mutations in BCL2 and amplification of the MCL1 gene but is heterogeneous across and within individual patient leukemias. Changes in the proapoptotic genes are notably uncommon, except for single cases with subclonal losses of BAX or NOXA. Much more prominent was universal MCL1 gene upregulation. This was driven by an overlying layer of emergent NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa B) activation, which persisted in circulating cells during VEN therapy. We discovered that MCL1 could be a direct transcriptional target of NF-κB. Both the switch to alternative prosurvival factors and NF-κB activation largely dissipate following VEN discontinuation. Our studies reveal the extent of plasticity of CLL cells in their ability to evade VEN-induced apoptosis. Importantly, these findings pinpoint new approaches to circumvent VEN resistance and provide a specific biological justification for the strategy of VEN discontinuation once a maximal response is achieved rather than maintaining long-term selective pressure with the drug.

Introduction

BH3-mimetics are a new class of small-molecule anticancer agents with a unique mechanism of action.1-3 One such agent, the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax4 (VEN), is now approved for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML).2,5,6 VEN disrupts the ability of BCL2 to restrain proapoptotic BCL2 family members (eg, BAX and BIM) through intracellular protein:protein interactions.3 The substantial clinical impact of VEN has spurred interest in other BH3-mimetics, which act selectively on related prosurvival proteins (eg, MCL17,8).

Secondary resistance to VEN (VEN-relapse) is a major clinical problem,2,9,10 but resistance mechanisms are beginning to be described and are unexpectedly heterogeneous.2,11-15 To date, research into clinical VEN resistance has largely focused on studies with bulk DNA sequencing, which detects coding mutations (eg, in BCL213) or gene amplification (eg, of MCL112). These approaches do not clarify what else might drive resistance (eg, other than BCL2 mutations) or give an accurate indication of potential tumor heterogeneity. Understanding how resistance to VEN develops in leukemia is necessary if its clinical use is to be optimized.

Current approved options for CLL patients include indefinite continuous use16 or time-limited therapy, either for 1 year as front-line treatment17 or 2 years as subsequent therapy.18 Although time-limited therapy is less expensive, the currently approved durations are arbitrary and may not be maximally beneficial. Strategies designed to personalize VEN treatment based on when a patient achieves a maximal reduction in their leukemic load are being explored and appear to be promising.19,20 All these approaches could be rationalized if we knew precisely what mediates resistance and whether it is reversible.

To fully uncover what drives VEN resistance in CLL, we have investigated the cohort of patients on VEN monotherapy with long-term follow-up5 using a novel multiomics approach. Given the anticipated complexity, we complemented single-cell short-read RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) to detect changes in gene expression with other methodologies applied to the same cells, notably single-cell long-read transcriptomic sequencing to discover isoform usage and link coding variations to transcriptional changes. This is the first patient cohort study in which long-read sequencing has been applied at the single-cell level to analyze full-length transcripts, integrating multiple genetic and phenotypic characteristics of single cells to explain resistance in patients.

Methods

Patient samples

After obtaining written informed consent, patient samples were collected before therapy, after progression on VEN, or after switching to a Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor (BTKi) (ibrutinib or zanubrutinib) treatment (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood website). Blood was collected in EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) tubes and processed within 2 hours. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated using Ficoll-Paque Plus (GE Healthcare, cat#17144002) density gradient centrifugation and cryopreserved.

Single-cell RNA and protein library preparation and sequencing

PBMCs were thawed, rested for 1 hour, and incubated with TruStain FcX (Biolegend, cat#422301) before staining with TotalSeq C antibodies (supplemental Methods) and CD19-BV510 (BD Biosciences) in Cell Staining Buffer (Biolegend), washed and stained with propidium iodide (PI, Sigma). To obtain equivalent tumor cells, viable (PI-ve) cells from each sample were flow-sorted into the same tube using the FACSAria (BD) to obtain ∼75% CD19+ve (CLL) and ∼25% CD19-ve (non-CLL) cells. Single cells (700-1100 cells per μl) were captured and barcoded using the Chromium Next GEM (Gel Bead-In Emulsions) Single Cell V(D)J (v1.1, 10× Genomics, cat#PN-1000165) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription time was increased to 2 hours to increase transcription of longer transcripts. After the GEM-RT, 20% volume of GEMs was transferred into a new tube, and subsequent steps were performed in parallel for both the 20% and 80% subsamples. Standard Illumina gene expression and protein expression libraries were prepared according to the 10× Genomics protocol and pooled to be sequenced. Library pools were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq-500 using the v2 150-cycle High Output kit (Illumina) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The base calling and quality scoring were determined using real-time analysis on board software (v2.4.6), while the FASTQ file generation and demultiplexing used bcl2fastq conversion software (v2.15.0.4).

Single-cell short-read data analysis

The CITE-seq (Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes by Sequencing) data were processed using the Cell Ranger software (v3.0.2, hg38 human genome), with “cellranger mkfastq” used to generate fastq files and “cellranger count” for the gene count matrix. The quickPerCellQC function in scuttle (v1.2.0)21 was used together with thresholds to remove low-quality cells with <500 UMI counts, 400 genes detected, or >15% mitochondrial reads. Data normalization and gene selection were performed for each sample using scran (v1.20.1)22 with function logNormCounts, modelGeneVar, and getTopHVGs. Data from different samples were integrated by the mutual nearest neighbor algorithm23 implemented using the fastMNN function with parameters k = 30, d = 50, deferred = FALSE, and auto.merge = TRUE. Doublets were identified by CD3 and CD20 antibody counts, and clusters that contained >50% doublet-positive cell barcodes were removed. The integrated data were converted to a Seurat object, and the Seurat package (v3.1.0)24 was used for downstream analysis. Clusters with CLL and B-cell markers (CD19+veCD20+ve) were identified jointly by gene expression and antibody count data, and CLL cells (CD19+veCD20+ve CD5+ve) from screening and at VEN-relapse were extracted for subsequent analysis that focused on the comparison between these 2 conditions.

We repeated data integration and clustering on CLL cells using the same methods. Differentially expressed marker genes for each cluster were identified by the FindAllMarkers function and ranked by fold change, with the top 4 genes plotted in supplemental Figure 2B. A list of all marker genes can be found in supplemental Table 1. The percentage of cells per cluster for each condition was ordered and shown in Figure 1D, where the same percentage was calculated for each sample in the heatmaps.

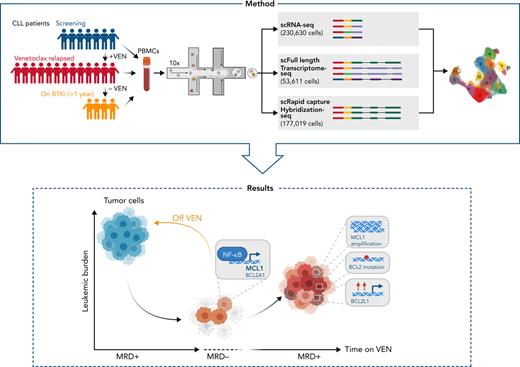

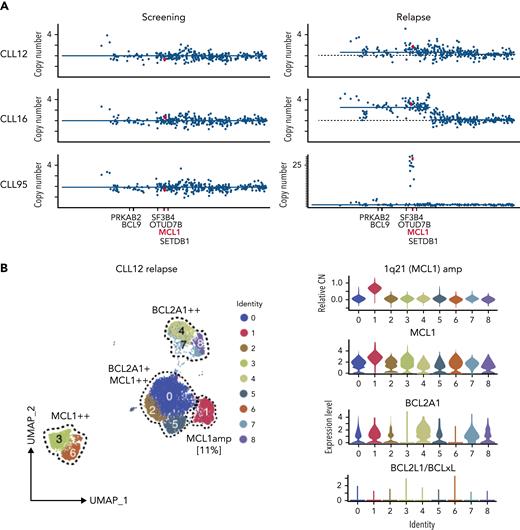

Single-cell multiomics reveals altered gene expression upon acquisition of VEN resistance. (A) Schematic of single-cell multiomics approach. The details of the patients are provided in supplemental Figure 1A-B. Samples taken at different time points from the same patient are connected with dotted lines. (B) UMAP projection of PBMCs (n = 230 360 cells) collected from patients or healthy donors (control samples). (C) UMAP projection specifically of the CLL cells (n = 161 499 cells) collected from patients at screening or after VEN relapse. (D) Upper: bar graphs of normalized proportions of all screening (blue) or relapsed (red) CLL cells from each cluster. Lower: heatmap portrays the abundance of CLL cells per sample (rows) in individual clusters (columns). Blue line: clusters predominantly represented in screening samples (“Group I”); red line: clusters representative of relapsed samples (“Group III”). (E) Dot plots showing a curated list of marker genes unique to the Group I screening-representative clusters or Group III relapse-representative clusters. Color intensity reflects the relative degree of gene expression and the size of the dot indicates the fraction of cells expressing that gene in that cluster, as exemplified by the higher expression of MCL1 present in more cells of the Group III clusters.

Single-cell multiomics reveals altered gene expression upon acquisition of VEN resistance. (A) Schematic of single-cell multiomics approach. The details of the patients are provided in supplemental Figure 1A-B. Samples taken at different time points from the same patient are connected with dotted lines. (B) UMAP projection of PBMCs (n = 230 360 cells) collected from patients or healthy donors (control samples). (C) UMAP projection specifically of the CLL cells (n = 161 499 cells) collected from patients at screening or after VEN relapse. (D) Upper: bar graphs of normalized proportions of all screening (blue) or relapsed (red) CLL cells from each cluster. Lower: heatmap portrays the abundance of CLL cells per sample (rows) in individual clusters (columns). Blue line: clusters predominantly represented in screening samples (“Group I”); red line: clusters representative of relapsed samples (“Group III”). (E) Dot plots showing a curated list of marker genes unique to the Group I screening-representative clusters or Group III relapse-representative clusters. Color intensity reflects the relative degree of gene expression and the size of the dot indicates the fraction of cells expressing that gene in that cluster, as exemplified by the higher expression of MCL1 present in more cells of the Group III clusters.

All gene set enrichment analyses were performed using the GSEA website,25 and the top 10 significant gene sets were selected. NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa B) activation was calculated using AddModuleScore function in Seurat, with MSigDB (v7.3).25

The copy number variations (CNVs) of MCL1 were first identified at the bulk level using whole-exome sequencing (WES). The genes near MCL1 that were inferred to have amplification were used as input to the AddModuleScore function to calculate the MCL1 amplification score per cell.

The data analysis of individual patient samples was performed by first extracting CLL cell data from all samples related to the patient and then repeating the data integration and clustering (see above).

Full-length transcriptome sequencing

Full-length complementary DNA (cDNA) generation from the 20% subsample (10× protocol) for full-length transcriptome sequencing was carried out as described in detail at protocols.io (dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.8d9hs96). Full-length cDNA libraries were prepared using SQK-LSK109 Ligation Sequencing Kit (Oxford Nanopore Technologies [ONT]), and 50 fmol per library was sequenced on PromethION FLO-PRO002 R9.4.1 flow cells according to the manufacturer’s protocol.26

Rapid capture hybridization sequencing (RaCH-seq)

cDNA generation for RaCH-seq was similar to full-length transcriptome sequencing, except that cDNA from the 80% subsample was used for amplification using the primers 10× Partial R1: CTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT and T5′ PCR Primer IIA: AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAG in place of FPSfilA and RPSfilBr. The amplified cDNA sample (2 μg) and 1 μl of the Blocking Oligos (1000 μM, xGen Integrated DNA Technologies [IDT]): Poly A: TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT/3InvdT/, PR1: CTACACGCGCTCTTCCGATCT and SO: AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGTAC were dried using a DNA vacuum concentrator (speed vac). To the dried sample, 8.5 μl 2× Hybridization Buffer, 2.7 μl Hybridization Buffer Enhancer (xGen Lockdown Hybridization and Wash Kit, IDT, cat#1080577), and 1.8 μl Nuclease Free Water (Thermo Fisher) were added and heated at 95°C for 10 minutes to denature the cDNA. Custom Lockdown Probe Panel (4 μl; xGen IDT) (supplemental Table 2) was added to the sample and hybridized to the cDNA at 65°C for 16 hours. The probe pulldown with streptavidin beads was performed using xGen Lockdown Hybridization and Wash Kit (IDT) with the following modifications: the sample was added directly to the dried washed beads (100 μl of Dynabeads M-270 Streptavidin). The captured sample and beads were resuspended in 50 μl EB Buffer (Qiagen) and amplified with the LA Taq DNA Polymerase Hot-Start (Takara) using the primers:

FPSfilA: 5′-ACTAAAGGCCATTACGGCCTACACGACGCTCT TCCGATCT,

RPSfilBr: 5′-TTACAGGCCGTAATGGCCAAGCAGTGGTATC AACGCAGAGTA.

Full-length cDNA libraries were prepared, and a pool of barcoded 8 to 9 captured samples was sequenced on PromethION flow cell.

Single-cell long-read data analysis

We performed base calling on the raw fast5 data using Guppy (v3.1.5) from ONT to generate fastq files. Isoform detection and quantification were performed using FLAMES (v0.1).26 Demultiplexing was carried out by searching the long-reads for cell barcodes identified in the matching short-read data, followed by read alignment to the human genome hg38 with minimap2 (v2.17). FLAMES then grouped similar isoforms and constructs consensus sequences from the assembly, to which the long reads are subsequently realigned to using minimap2 and quantified to get isoform counts. For each sample, we found genes with differential isoform usage at the cluster level using the workflow described previously.26 We identified mutations in the long-read data in a supervised way using the genomic coordinates of known mutations generated from WES data and summarized the per cell allele frequency for these known mutations.

Code and scripts are deposited at https://github.com/LuyiTian/scripts_for_venetoclax_Racheletal.

Data sharing statement

Sequencing data are available via the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA; accession number EGAS00001005815). A data transfer agreement is required, and limitations are in place on the disclosure of germline variants. Any other relevant data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Additional details are provided in the supplemental Methods for human ethics approvals, drug sensitivity assays, WES, ATAC (assay for transposase-accessible chromatin)- and ChIP (chromatin immunoprecipitation)-seq, mass cytometry, proliferation assay, CLL cell culture, real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, generation of cell lines, immunoblotting, and targeted DNA sequencing.

Results

Changes in gene expression upon acquisition of VEN resistance

Initially, we took an unbiased approach to compare the relapsed PB samples (n = 13; collected from patients whose CLL progressed after 30 to 84 months of continuous VEN monotherapy, having responded for >2 years) with screening samples (n = 7 available samples collected from the same patients before VEN) (supplemental Figure 1A-B). Reflecting the cell-intrinsic differences, the relapsed samples were less sensitive to VEN when tested in vitro than paired screening samples (supplemental Figure 1C).

In total, we sequenced 230 630 cells from 23 samples, which also included 4 during subsequent alternative therapy (“on BTKi” collected after switching to a BTKi after VEN-relapse) as well as 3 healthy donors (Figure 1A). The sequencing data from all cells in this study cohort were integrated using the mutual nearest neighbor method before clustering and visualizing using UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) (Figure 1B).24,27 B-cells (normal, CLL) could be readily distinguished from T/natural killer cells or monocytes, and the leukemic cells were identifiable by their distinct transcriptomes (supplemental Figure 2A) and expression of CLL markers (CD5, CD19, and CD20).28

These leukemic cells could be grouped into 20 distinct clusters based on relative gene expression, each having a unique set of marker genes (Figure 1C, supplemental Table 1, and supplemental Figure 2B). Regardless of VEN treatment status, each sample harbored leukemic cells across multiple clusters, demonstrating a high degree of intrapatient heterogeneity (Figure 1D and supplemental Figure 3A). Compared with the screening samples, each of the relapsed samples contained a distinctive set of clusters suggesting interpatient heterogeneity at leukemic relapse (supplemental Figure 3A-B), more marked than before VEN. Each VEN-relapse sample had dominant cluster(s), but these did not appear to be shared between the relapsed samples (Figure 1D). However, closer inspection of marker genes for each cluster suggested an underlying pattern. When compared, there was increased expression of some genes (Figure 1E) in the clusters containing mainly relapsed cells (eg, clusters #4 and #17), whereas those clusters enriched with screening cells (eg, clusters #10 and #13) had relatively higher expression of another set of genes.

Increased MCL1 expression in all VEN relapse samples, but MCL1 gene amplification was only detected in some cases

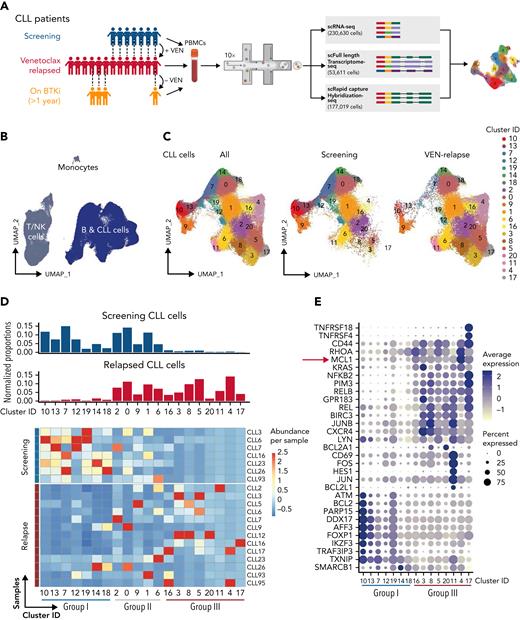

While some of the relapse-enriched Group III clusters (Figure 2A) had increased expression of BCLxL (#11) or BCL2A1 (#8 and #20), there was enrichment of MCL1, another relative of prosurvival BCL2, across all the Group III clusters (Figure 2A). Accordingly, MCL1 mRNA (Figure 2B) and MCL1 protein concentrations were higher at relapse in most of the samples (Figure 2C). Previously, MCL1 gene amplification had been reported in VEN-relapse CLL,12 but whether increased MCL1 is solely because of amplification of the MCL1 gene locus is unknown. We investigated this further since we could integrate our scRNA-seq data with the WES to infer CNV. We found only 3 (out of 13) instances of copy number (CN) gain at 1q21 (where MCL1 is located) (Figure 3A and supplemental Figure 4).

VEN-resistant cells display altered survival signaling. (A) Dot plots showing relative expression of prosurvival genes across Group I (predominantly cells from screening samples) and Group III (predominantly VEN-relapsed samples) clusters. (B) Violin plots showing MCL1 expression across the individual patient samples, including 3 with 1q21 (MCL1) amplification (marked as green bars). The height of the violins indicates the relative degree of MCL1 gene expression, and the width indicates the proportion of cells in a sample with increased MCL1 expression. (C) Mass cytometric analysis of MCL1 protein expression in viable (cisplatinlo) CD5+veCD19+ve CLL cells among PBMCs from screening (blue, n = 6) or relapsed samples (red, n = 11). The median expression for each sample was calculated by FlowJo. P value is from a 2-sided paired t test. Paired patient samples are joined by dotted lines. ∗Patient (CLL26) relapsed while off VEN.

VEN-resistant cells display altered survival signaling. (A) Dot plots showing relative expression of prosurvival genes across Group I (predominantly cells from screening samples) and Group III (predominantly VEN-relapsed samples) clusters. (B) Violin plots showing MCL1 expression across the individual patient samples, including 3 with 1q21 (MCL1) amplification (marked as green bars). The height of the violins indicates the relative degree of MCL1 gene expression, and the width indicates the proportion of cells in a sample with increased MCL1 expression. (C) Mass cytometric analysis of MCL1 protein expression in viable (cisplatinlo) CD5+veCD19+ve CLL cells among PBMCs from screening (blue, n = 6) or relapsed samples (red, n = 11). The median expression for each sample was calculated by FlowJo. P value is from a 2-sided paired t test. Paired patient samples are joined by dotted lines. ∗Patient (CLL26) relapsed while off VEN.

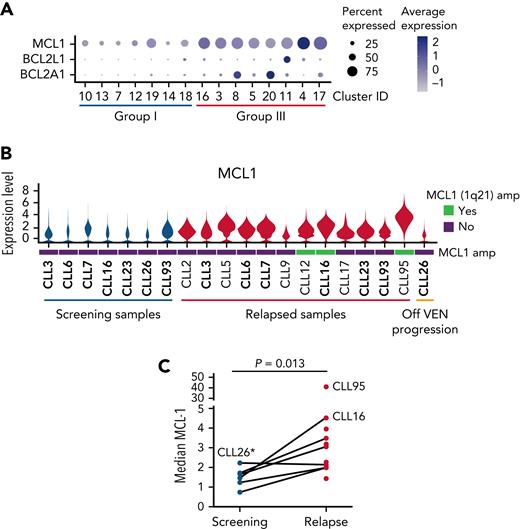

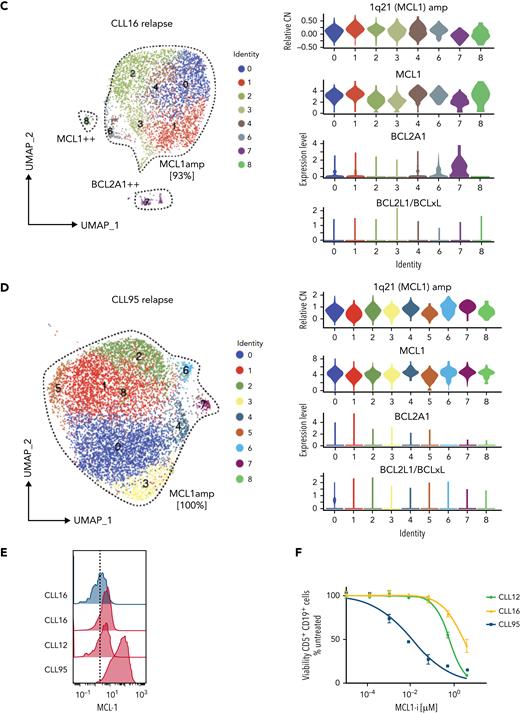

Increased MCL1 expression at VEN relapse is only partially explained by amplification of the MCL1 gene. (A) Representation of the gained genomic regions in the 1q locus across the screening and relapsed samples from CLL12, CLL16, and CLL95 analyzed by WES. MCL1 is highlighted in red. Gray dotted lines indicate CN of 2. Blue lines indicate CN inferred from WES data. (B-D) UMAP projections (left) of CLL cells from (B) CLL12, (C) CLL16, and (D) CLL95 at relapse, with violin plots (right panels) showing inferred CN variation of 1q21 (MCL1) or relative expression of indicated prosurvival genes across the individual clusters. (E) Histograms showing mass cytometric analysis of MCL1 protein expression in viable (cisplatinlo) CD5+veCD19+ve PBMCs from screening samples from CLL16 (blue), relapsed samples from CLL16, CLL12, and CLL95 (all red). (F) PBMCs prepared at VEN-relapse were incubated in vitro for 24 hours with 0 to 4 μM S63845 (MCL1i). Viability (PI-ve) was measured in CLL cells (CD5+veCD19+ve), and data points represent the mean ± standard deviation of triplicate measurements in single experiments. CLL95 displayed marked sensitivity to MCL1i (LC50 10nM), while CLL12 and CLL16 had modest sensitivity (LC50s ∼600nM and ∼2700nM, respectively).

Increased MCL1 expression at VEN relapse is only partially explained by amplification of the MCL1 gene. (A) Representation of the gained genomic regions in the 1q locus across the screening and relapsed samples from CLL12, CLL16, and CLL95 analyzed by WES. MCL1 is highlighted in red. Gray dotted lines indicate CN of 2. Blue lines indicate CN inferred from WES data. (B-D) UMAP projections (left) of CLL cells from (B) CLL12, (C) CLL16, and (D) CLL95 at relapse, with violin plots (right panels) showing inferred CN variation of 1q21 (MCL1) or relative expression of indicated prosurvival genes across the individual clusters. (E) Histograms showing mass cytometric analysis of MCL1 protein expression in viable (cisplatinlo) CD5+veCD19+ve PBMCs from screening samples from CLL16 (blue), relapsed samples from CLL16, CLL12, and CLL95 (all red). (F) PBMCs prepared at VEN-relapse were incubated in vitro for 24 hours with 0 to 4 μM S63845 (MCL1i). Viability (PI-ve) was measured in CLL cells (CD5+veCD19+ve), and data points represent the mean ± standard deviation of triplicate measurements in single experiments. CLL95 displayed marked sensitivity to MCL1i (LC50 10nM), while CLL12 and CLL16 had modest sensitivity (LC50s ∼600nM and ∼2700nM, respectively).

Interestingly, the fraction of leukemic cells with MCL1 CN gain in these samples was variable. In CLL12, a patient commenced on a BTK inhibitor, having previously relapsed on VEN (Figure 3B and supplemental Figure 1B), a distinct cluster (#1, ∼11% of the cells) with 1q21 (MCL1) gain was present at relapse; however, the cells in other clusters did not have 1q21 (MCL1) gain. Instead, upregulation of MCL1, BCL2A1, or both prosurvival genes characterized these clusters. In CLL16 (Figure 3C), there was a large cluster (∼93%) with 1q21 (MCL1) gain at relapse, as well as others that were MCL1hi or BCL2A1hi but did not harbor MCL1 CN gain. By contrast, the entire relapse sample of CLL95 (Figure 3D) showed a marked gain of 1q21 (MCL1), and the leukemic cells expressed very high concentrations of MCL1 protein compared with CLL12 or CLL16 (Figure 3E). Accordingly, CLL95 at relapse was highly dependent on MCL1 (Figure 3F).

Taken together, MCL1 gene amplification could only account for increased MCL1 expression in 3 of 13 relapses, subclonally in 2 (CLL12 and CLL16); moreover, the degree of MCL1 CN gain and, hence, MCL1 expression varied between the samples.

Prominent NF-κB activation marks VEN relapse

To address what was driving increased MCL1 expression, we compared gene expression between the relapse-enriched clusters (Group III) with the screening-enriched clusters (Group I) and then applied pathway analysis to the marker genes, identifying strong NF-κB29,30 activation in Group III (Figure 4A). There was enrichment of NF-κB pathway genes (Figure 4B), including key NF-κB mediators REL, RELB, and NFKB2 (supplemental Figure 5A). The Group II clusters most common to the screening and relapsed cells were also analyzed, revealing NF-κB activation in the VEN-relapse cells within these clusters (supplemental Figure 5B).

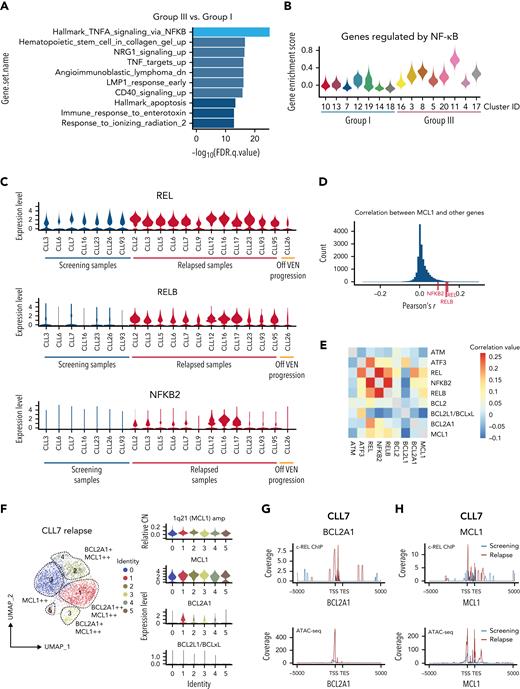

Increased MCL1 expression driven by NF-κB at VEN relapse. (A) Bar plots showing pathway enrichment analysis in clusters from Group III (predominantly cells from VEN-relapsed samples) vs clusters in Group I (predominantly cells from screening samples). (B) Violin plots showing NF-κB pathway gene enrichment in Group III relapsed clusters. (C) Relative expression of REL, RELB, and NFKB2 in screening (n = 7; on left) or relapse (n = 13) samples; 1 patient (CLL26; on right) progressed while off VEN. (D) Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated between MCL1 and all other genes. The r score between MCL1 and REL, RELB, or NFKB2 are indicated with red ticks at the bottom. (E) Heatmap showing the correlation in expression between the indicated genes in the relapsed samples. Red shades indicate stronger positive correlations. (F) UMAP projections (left) of CLL cells from CLL7 at relapse, with violin plots (right panels) showing inferred CN variation of 1q21 (MCL1) or relative expression of indicated prosurvival genes across the individual clusters. (G-H) c-REL ChIP and chromatin accessibility at the BCL2A1 (G) and MCL1 (H) loci 5000 kb upstream of the transcriptional start site (TSS) or 5000 kb downstream of the transcriptional end site (TES) in purified CLL cells from screening (blue) or relapsed (red) samples from CLL7.

Increased MCL1 expression driven by NF-κB at VEN relapse. (A) Bar plots showing pathway enrichment analysis in clusters from Group III (predominantly cells from VEN-relapsed samples) vs clusters in Group I (predominantly cells from screening samples). (B) Violin plots showing NF-κB pathway gene enrichment in Group III relapsed clusters. (C) Relative expression of REL, RELB, and NFKB2 in screening (n = 7; on left) or relapse (n = 13) samples; 1 patient (CLL26; on right) progressed while off VEN. (D) Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated between MCL1 and all other genes. The r score between MCL1 and REL, RELB, or NFKB2 are indicated with red ticks at the bottom. (E) Heatmap showing the correlation in expression between the indicated genes in the relapsed samples. Red shades indicate stronger positive correlations. (F) UMAP projections (left) of CLL cells from CLL7 at relapse, with violin plots (right panels) showing inferred CN variation of 1q21 (MCL1) or relative expression of indicated prosurvival genes across the individual clusters. (G-H) c-REL ChIP and chromatin accessibility at the BCL2A1 (G) and MCL1 (H) loci 5000 kb upstream of the transcriptional start site (TSS) or 5000 kb downstream of the transcriptional end site (TES) in purified CLL cells from screening (blue) or relapsed (red) samples from CLL7.

NF-κB activation in CLL was previously reported but only in leukemic cells that recently engaged with the microenvironment (typically exhibiting low CXCR4 expression).31,32 In our study, widespread NF-κB activation coincided with high CXCR4 expression, suggesting that these circulating CLL cells are not recent emigrants (Figure 1E and supplemental Figure 5C). This unexpected finding of NF-κB activation prompted us to fully interrogate the link between NF-κB and VEN resistance.

Firstly, the expression of key NF-κB mediators was substantially higher in the relapsed samples (Figure 4C). Secondly, these relapsed samples showed some sensitivity to in vitro blockade of NF-κB but not the other pathways tested (supplemental Figure 5D). Thirdly, CLL26 was an instructive example: unlike all the other relapse samples collected while patients were on VEN (Figure 4C), this sample was collected at disease recurrence 38 months after VEN discontinuation, the patient having previously achieved a complete clinical remission. Strikingly, NF-κB activation was absent in CLL26 when leukemia recurred after an extended period off VEN, thus raising the possibility that the prevalent NF-κB activation was sustained by ongoing VEN therapy.

Increased MCL1 expression at VEN relapse is closely associated with NF-κB activation

We hypothesized a causal link between NF-κB activation and widespread increase in MCL1 expression even though NF-κB is known to promote cell survival by transcriptionally activating BCLxL or BCL2A1.33,34 Consistent with our hypothesis, the top genes that correlate with the expression of MCL1 at relapse are NF-κB mediators REL, RELB, and NFKB2 (Figures 4D-E). Thus, we sought evidence of a direct mechanistic link between NF-κB activation and increased MCL1 expression.

To do this, we investigated another relapsed sample, CLL7, in which there was increased MCL1 expression (without MCL1 gene amplification) (Figure 2B and supplemental Figure 6A-B) and subclonal increase of BCL2A1, a bone fide NF-κB transcriptional target (Figure 4F and supplemental Figure 6C). Thus, we could evaluate by CHIP-seq whether NF-κB (c-REL protein) might be responsible for transcriptionally activating MCL1 in this sample. As expected, there was increased c-REL (Figure 4G) and NFKB2 (supplemental Figure 6D) binding to BCL2A1, driven by increased chromatin accessibility (see ATAC-seq undertaken with the same samples). In this patient, this was also the case for MCL1 at relapse (Figure 4H and supplemental Figure 6D), even though NF-κB has not previously been reported to drive MCL1 transcription.

Single-cell long-read sequencing reveals heterogeneous, complex, and multilayered changes at VEN relapse

The complex transcriptional changes arising during acquired VEN resistance revealed by scRNA-seq, with multiple and distinctive changes in gene expression (Figures 1-4), prompted us to probe some of the additional samples further. We undertook single-cell whole-transcriptome long-read sequencing on a subset of cells from each sample to test whether novel isoform usage or mutations could also contribute to resistance.26 Aged-matched healthy donor PBMCs were included as control samples for analysis of isoform usage. Further, we developed a new method using the 10× Genomics platform to capture full-length cDNAs of interest with probes (RaCH-seq) (see METHODS). We designed probes to capture the genes of the BCL2 family for a deeper coverage allowing us to undertake an in-depth analysis of these genes (Figure 5A). By integrating the single-cell gene expression data (from short-reads) with coding sequence and transcript usage information (whole transcriptome full-length sequencing,26 RaCH-seq, Figure 1A, and bulk WES), we obtained a much deeper resolution of the changes at VEN relapse.

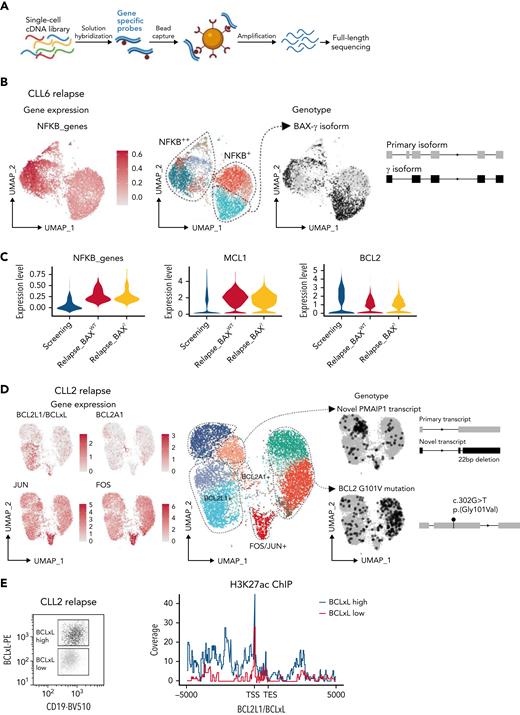

Multiple mechanisms drive VEN resistance even within a patient. (A) Schematic of RaCH-seq workflow. (B) CLL cells from CLL6 at relapse with altered gene expression (left), cluster assignments (middle), and BAXγ isoform (right). (C) Violin plots showing expression of NF-κB genes (left), MCL1 (middle), and BCL2 (right) for CLL6 screening or at relapse, with or without BAXγ. (D) CLL cells from CLL2 at relapse showing expression for the indicated genes (left, in red), with cluster assignments (middle), and RaCH-seq data for variants of interest (right, in black). (E) H3K27ac ChIP at the BCLxL locus in flow-sorted (left) CD19+veCD5+ve BCLxLhi (blue) or BCLxLlo (red) cells from CLL2; data representative of 2 independent experiments.

Multiple mechanisms drive VEN resistance even within a patient. (A) Schematic of RaCH-seq workflow. (B) CLL cells from CLL6 at relapse with altered gene expression (left), cluster assignments (middle), and BAXγ isoform (right). (C) Violin plots showing expression of NF-κB genes (left), MCL1 (middle), and BCL2 (right) for CLL6 screening or at relapse, with or without BAXγ. (D) CLL cells from CLL2 at relapse showing expression for the indicated genes (left, in red), with cluster assignments (middle), and RaCH-seq data for variants of interest (right, in black). (E) H3K27ac ChIP at the BCLxL locus in flow-sorted (left) CD19+veCD5+ve BCLxLhi (blue) or BCLxLlo (red) cells from CLL2; data representative of 2 independent experiments.

For each patient, we performed an unsupervised analysis looking for altered splicing events that correlate with transcriptional clusters and found the loss of exon 2 in BAX in certain clusters of CLL6 at relapse (Figure 5B). Undetectable at screening (supplemental Figure 4), this transcript was generated by a splice acceptor site mutation (c.35-2A>C), resulting in altered BAX splicing and a truncated, nonfunctional protein (BAX-γ35). Since the other BAX allele was deleted in this subclone (supplemental Figure 7A), we concluded there was a complete loss of BAX in these cells. What drives resistance in the remainder of CLL6? By integrating our data, we also found prominent NF-κB activation and increased MCL1 expression (without CN gain) at relapse (Figure 5C).

WES confirmed BCL2 mutations15 in 3 VEN-relapse samples but no overall increase in somatic mutations (supplemental Figure 7B). CLL2 is of interest since we have previously reported BCL2 G101V as well as increased BCLxL protein in distinct subclones at relapse.13 Applying RaCH-seq, we observed the presence of the BCL2 G101V mutated transcript in cells from distinct clusters (Figure 5D); intriguingly, in the clusters expressing BCL2 G101V, the wild-type BCL2 transcript was undetectable. Integrating this with scRNA-seq confirmed13 that the BCLxLhi cells were in different clusters and that additional clusters were characterized by BCL2A1hi or FOShi/JUNhi. Yet another cluster, also previously unappreciated, expressed an altered transcript of proapoptotic NOXA (PMAIP1) but not the wild-type transcript. The former, a 22bp deletion in the coding region of NOXA, encoded for a nonfunctional protein that reduced VEN sensitivity (supplemental Figure 7C-D), consistent with the loss of NOXA being implicated in VEN resistance.36,37 By leveraging single-cell transcriptomics,26 both short- and long-read, we identified ≥6 distinct mechanisms driving VEN resistance in CLL2; 5 in largely distinct subclones, concurrently with NF-κB activation present in all the cells at relapse (Figure 4B).

Since we did not understand why the cells express high BCLxL in VEN-relapse CLL2,13 we sought to identify the genetic drivers of increased BCLxL expression in this sample. Neither amplification of BCLxL (supplemental Figure 7E) nor mutation of SWI-SNF (SWItch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable) genes previously reported in VEN-relapse mantle cell lymphoma38 were detected. Instead, it appeared that increased BCLxL expression was driven by enhancer modification (increased H3K27ac binding) but not NF-κB binding (Figure 5E and supplemental Figure 7F); of note, BCL2A1 enhancer gain was previously reported in a cell line study of VEN resistance.37

Taken together, our findings allowed us to make some general conclusions about the acquisition of VEN-relapse in CLL among patients treated long-term (3 to 7 years) with VEN. While the loss of proapoptotic proteins was uncommon (supplemental Figure 8A), the inter- and intrapatient heterogeneity, underpinned by BCL2 mutation, MCL1/BCL2A1 upregulation, or high BCLxL protein expression (supplemental Figure 8A), is biologically intriguing as they suggest the co-emergence of multiple resistant clones, presumably all conferring survival advantage against VEN. As the VEN-relapse subclones did not otherwise appear to have an inherent growth advantage (supplemental Figures 8B-C), the development of polyclonal resistance mechanisms is likely to be a distinctive feature of acquired resistance to BH3-mimetic therapy.

Drivers for VEN resistance are sustained by ongoing VEN treatment

Finally, we asked if the multilayered, highly heterogeneous nature of acquired VEN-relapse could be maintained by long-term selection pressure exerted with ongoing VEN therapy and, thus, may diminish after discontinuing VEN. In CLL26, the absence of increased MCL1 expression and NF-κB activation at relapse off VEN (Figures 2B and 4C) supports this notion. To explore this further, we investigated 4 patients (CLL2, CLL5, CLL6, and CLL23) whose therapy was changed to a BTKi after VEN-relapse had developed (Figure 6 and supplemental Figure 9).

Altered transcriptional profiles at relapse dissipate after cessation of VEN therapy. (A) Bar plots (left) showing the proportion of CLL cells for each cluster (supplemental Figure 9A) from CLL23 samples collected at screening, after relapse while on VEN, and after subsequently switching to BTKi. Violin plots (middle; NF-κB high clusters marked in red) showing the expression of NF-κB genes for each cluster are shown on the left. Violin plots (right) showing NFKB genes, MCL1, BCL2A1, or BCL2 expression at different treatment stages for CLL23. (B-C) Bar plots (left) showing the proportion of CLL cells for each cluster (supplemental Figure 9B-C) from (B) CLL5 or (C) CLL2 samples collected at relapse while on VEN and after subsequently switching to BTKi. Violin plots (middle) showing the expression of NF-κB genes for each cluster are shown on the left. Violin plots (right) showing NFKB genes, MCL1, BCL2A1, BCL2, or BCLxL expression at different treatment stages for (B) CLL5 or (C) CLL2.

Altered transcriptional profiles at relapse dissipate after cessation of VEN therapy. (A) Bar plots (left) showing the proportion of CLL cells for each cluster (supplemental Figure 9A) from CLL23 samples collected at screening, after relapse while on VEN, and after subsequently switching to BTKi. Violin plots (middle; NF-κB high clusters marked in red) showing the expression of NF-κB genes for each cluster are shown on the left. Violin plots (right) showing NFKB genes, MCL1, BCL2A1, or BCL2 expression at different treatment stages for CLL23. (B-C) Bar plots (left) showing the proportion of CLL cells for each cluster (supplemental Figure 9B-C) from (B) CLL5 or (C) CLL2 samples collected at relapse while on VEN and after subsequently switching to BTKi. Violin plots (middle) showing the expression of NF-κB genes for each cluster are shown on the left. Violin plots (right) showing NFKB genes, MCL1, BCL2A1, BCL2, or BCLxL expression at different treatment stages for (B) CLL5 or (C) CLL2.

In CLL23, the transcriptional profile of the leukemic population reverted to resemble that before VEN (Figure 6A and supplemental Figure 9A). Accordingly, the NF-κB activation and increases in MCL1/BCL2A1 not driven by gene amplification at VEN-relapse were no longer present off VEN (Figure 6A). NF-κB activation was also reduced in CLL5 (Figure 6B and supplemental Figure 9B) and CLL2 (Figure 6C and supplemental Figure 9C) when off VEN compared with VEN-relapse. Concordantly, the increased expression of MCL1 at VEN-relapse in CLL5 (Figure 6B) and increased expression MCL1/BCL2A1 in CLL2 (Figure 6C) or in CLL6 (supplemental Figure 9D) in the absence of MCL1 gene amplification were no longer observed once VEN was discontinued. Furthermore, cells with increased BCLxL expression (CLL2) (Figure 6C) or BAX mutation (CLL6) (supplemental Figure 9E) diminished once the patients were no longer treated with VEN. Consistent with these observations, the leukemic cells also substantially recovered their in vitro sensitivity to VEN (supplemental Figure 9F). Whether the reversion in gene expression is solely because of VEN cessation or, at least in part, because of BTKi treatment cannot be formally resolved using the samples available for our study.

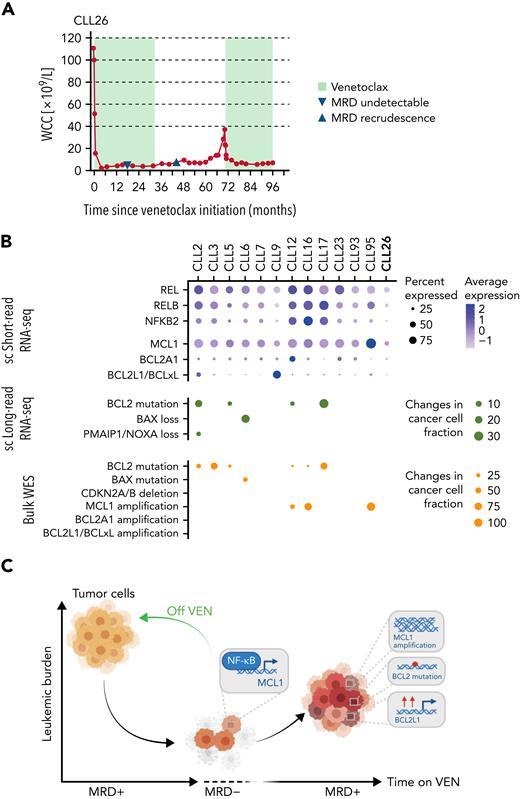

In sum, while CLL cells have the capacity to reduce their sensitivity to VEN, the changes at VEN-relapse appeared to be driven and sustained by ongoing VEN therapy. Normally, NF-κB activation in circulating CLL cells is infrequent, and as chronic NF-κB signaling could be oncogenic,39 we investigated the expression of key NF-κB mediators at earlier time points: after just 6 months on VEN, some NF-κB dysregulation in rare persisting cells was already evident (supplemental Figure 9G), suggesting that early intervention may be necessary in some scenarios. Finally, the striking response (Figure 7A) to VEN retreatment of CLL26 (relapsed off VEN without evidence of NF-κB activation or altered survival signaling (eg, increased MCL1 expression) (Figures 2B and 4C) strongly supports the notion that time-limited, instead of continuous, VEN therapy should be considered to avoid the development of full-blown resistance to VEN.

Single-cell multiomics approach reveals multilayered changes driving VEN resistance. (A) PB white cell counts of CLL26 during VEN treatment, following VEN discontinuation, and subsequent VEN retreatment when CLL recurred. MRD undetectable: first confirmation of PB undetectable MRD (CLL cells <0.01% of leukocytes), MRD recrudescence: first confirmation of MRD positivity in PB (CLL cells ≥0.01% of leukocytes). MRD, measurable residual disease. (B) Dot plots summarizing the single-cell RNA-seq, single-cell long-read sequencing, and WES changes observed in patient samples at VEN-relapse. For the single-cell short-read RNA-sequencing, color indicates relative degrees of gene expression, and the size of the dot indicates the proportion of cells with altered expression in a patient sample. For single-cell long-read RNA-seq and WES, the size of the dot indicates the fraction of cells harboring the mutation in a patient sample; no dots: not detected. (C) Schematic illustration of the study highlights.

Single-cell multiomics approach reveals multilayered changes driving VEN resistance. (A) PB white cell counts of CLL26 during VEN treatment, following VEN discontinuation, and subsequent VEN retreatment when CLL recurred. MRD undetectable: first confirmation of PB undetectable MRD (CLL cells <0.01% of leukocytes), MRD recrudescence: first confirmation of MRD positivity in PB (CLL cells ≥0.01% of leukocytes). MRD, measurable residual disease. (B) Dot plots summarizing the single-cell RNA-seq, single-cell long-read sequencing, and WES changes observed in patient samples at VEN-relapse. For the single-cell short-read RNA-sequencing, color indicates relative degrees of gene expression, and the size of the dot indicates the proportion of cells with altered expression in a patient sample. For single-cell long-read RNA-seq and WES, the size of the dot indicates the fraction of cells harboring the mutation in a patient sample; no dots: not detected. (C) Schematic illustration of the study highlights.

Discussion

Our single-cell multiomics analyses reveal that the emergence of VEN relapse in CLL is highly complex, with multiple coexisting changes present (Figure 7B). We identify, for the first time, consistent and marked NF-κB activation and associated increased MCL1 expression in all analyzed relapses occurring during ongoing VEN therapy. Although a recent study has revealed a putative binding site for NF-κB at the MCL1 locus,40 we are the first to show direct binding of c-REL at the MCL1 locus in primary CLL cells. Future studies are required to elucidate the factors that drive high NF-κB in circulating CLL cells from patients treated continuously with VEN.

Aside from the high NF-κB and MCL1 expression, CLL cells at VEN relapse typically have a second layer of genetic and epigenetic changes that center around the core apoptotic machinery. Increased expression of prosurvival relatives of BCL2, which are not targeted by VEN (MCL1, BCL2A1, or BCLxL), were typically subclonal, each contributing to the resistant population in several individual patients in a piecemeal fashion. Although MCL1 upregulation was prominent, MCL1 gene amplification was only detected in a minority of relapsed samples, and the subclonal nature of MCL1 CN gain was consistent with the overall complexity observed at relapse. Mutations in BCL2 were also detected subclonally, confirming prior reports.13-15 Application of whole transcriptome single-cell long-read sequencing to our patient cohort did not reveal any distinct altered isoform landscape contributing to VEN resistance but did allow us to directly investigate resistance mechanisms in the clones that do not harbor BCL2 mutations.

While gains in prosurvival signaling were universal, loss of proapoptotic signals, anticipated from studies with model cell lines,12,36,41 was uncommon at VEN-relapse in patients: subclonal losses of NOXA and BAX were the only examples in our cohort. No other losses in gene or protein expression, coding mutations, or altered transcript usage in the proapoptotic genes were detected with our highly sensitive single-cell approaches. Similarly surprising was the lack of increased proliferation at relapse. The expression (mRNA and protein) of the key drivers of cellular proliferation was unaltered, and we could not confirm the loss of CDKN2A/B previously reported.11

Taken together (Figure 7C), our data indicate that in patients with CLL, the leukemic cells intrinsically adapt in multiple ways to selection pressure on cell survival exerted by ongoing VEN treatment. Future prospective studies are needed to resolve the potential role of the microenvironment in providing extrinsic signals to cause VEN resistance. Our findings also suggest that drugs targeting mutant BCL2 (eg, BCL2 G101V) or altered survival signaling (eg, high MCL1 or BCL2A1) are unlikely to succeed in circumventing VEN-relapse CLL.

Rather, limited duration VEN therapy is an appealing strategy to prevent the emergence of resistance. The response of CLL26 with VEN retreatment (Figure 7A) and emerging evidence that many patients respond to VEN retreatment at relapse20,42 supports this approach that was developed empirically. Indeed, our data demonstrating the consequences of ongoing VEN selection pressure provide a biological explanation for the preliminary observations from the MURANO (NCT02005471) trial of time-limited therapy that BCL2 mutations are not a feature of reemergent CLL in patients off VEN.43 Since NF-κB activity is evident in persisting leukemic cells after 6 months of VEN therapy, our findings suggest that monitoring NF-κB activity could serve as a biomarker to indicate which patients are likely to respond to VEN retreatment or would benefit from alternative therapy.

Collectively, by leveraging combined short-read and long-read single-cell RNA-seq, we demonstrated a complexity of transcriptional changes that mediate VEN-relapse CLL, even in the absence of obvious genetic alterations. Our approach to this disease provides a guide for future studies on the use of high-throughput single-cell applications combining epigenetics (eg, single-cell ATAC-seq) with transcriptomic data to fully resolve tumor plasticity and heterogeneity underpinning resistance to other cancer therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients who enrolled in the venetoclax clinical trials and for assistance from Naomi Sprigg and Kelli Gray with the collection and curation of patient samples. The authors also thank Casey Anttila, Connie Li, and Stephen Wilcox, the WEHI SCORE team and core facilities (flow cytometry, genomics), and Andrew Mitchell at the Materials Characterisation and Fabrication Platform (MCFP) at the University of Melbourne for mass cytometry support; and Andreas Strasser, Christine White, and Mark van Delft for their critical reading of the manuscript. Illustrations were created with BioRender.com.

This work was supported by scholarships, fellowships, and grants from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC: Program Grants 1016647, 1113577 to A.W.R., 1016701, 1113133 to D.C.S.H., Fellowships 1089072 to C.E.T., 1090236 and 1158024 to D.H.D.G., 1079560 to A.W.R., 1043149, 1156024 to D.C.S.H., Investigator Grant 1177718 to M.A.A., 1174902 to A.W.R.), the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society of America (Fellowship 5467-18 to R.T., Specialized Center of Research (SCOR) grant 7015-18 to A.W.R. and D.C.S.H.), The Australian Research Council (Discovery Project 200102903 to M.E.R.), Cure Cancer and Cancer Australia (grant 1186003 to R.T.), Victorian Cancer Agency (MCRF grant 15018 to I.J.M. and A.W.R., MCRF20026 Fellowship to C.E.T.), Cancer Council Victoria (grants-in-aid 1146518 and 1102104 to D.H.D.G. and 1124178 to I.J.M.), the University of Melbourne (MIRS and MIFRS scholarships to L.T., H.P., and T.M.D.), grants from Snowdome Foundation (M.A.A. and P.B.), Wilson Centre for Lymphoma Genomics (P.B.), Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre (support for mass cytometry), Perpetual Impact Philanthropy Founding (IPAP2019/1437 to C.E.T.), the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative DAF (an advised fund of Silicon Valley Community Foundation, grant number 2019-002443 to M.E.R.), and the Australian Cancer Research Foundation. This work was made possible through Victorian State Government Operational Infrastructure Support and the Australian Government NHMRC IRIISS.

Authorship

Contribution: R.T., L.T., M.E.R., A.W.R., and D.C.S.H. devised the research strategy; M.E.R., A.W.R., and D.C.S.H. cosupervised the research; R.T., M.A.A., A.J., H.P., C.E.T., Q.G., A.G., T.T., and T.M.D., performed the experiments; L.T., C.F., A.L.G., H.P., and T.E.L. performed data analyses; J.S.J. developed the tools; R.T., L.T., C.S.T., J.F.S., P.B., D.H.D.G., I.J.M., M.E.R., A.W.R., and D.C.S.H. helped to interpret results; R.T., L.T., A.W.R., and D.C.S.H. wrote the manuscript; and all authors reviewed the manuscript before submission.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.T., L.T., M.A.A., C.F., A.J., A.L.G., J.S.J., H.P., C.E.T., Q.G., A.G., T.T., T.M.D., D.H.D.G., I.J.M., M.E.R., A.W.R., and D.C.S.H. are employees of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, which receives milestone and royalty payments related to venetoclax. M.A.A. has received honorarium from AbbVie. C.S.T. receives research funding and honorarium from both AbbVie and Roche. J.F.S. has received research funding from AbbVie and Genentech and is a consultant and member of advisory boards for both companies. D.H.D.G. has received research funding from Servier. A.W.R. has received research funding from AbbVie. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for L.T. is the Broad Institute of Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.

The current affiliation for T.M.D. is the Hudson Institute of Medical Research, Melbourne, Australia.

The current affiliation for C.S.T. is the Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Australia.

Correspondence: David C. S. Huang, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, 1G Royal Parade, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia; e-mail: huang_d@wehi.edu.au; and Andrew W. Roberts, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, 1G Royal Parade, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia; e-mail: roberts@wehi.edu.au.

References

Author notes

∗R.T., L.T., D.C.S.H., A.W.R., and M.E.R contributed equally to this study.

Sequencing data are available via the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA; accession number EGAS00001005815). A data transfer agreement is required, and limitations are in place on disclosure of germline variants. Any other relevant data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal