Key Points

TLR1/2 signaling in bone marrow DCs results in expansion of HSPCs with reduced repopulating activity through IL-1β production.

Bone marrow DCs in patients with low-risk myelodysplastic syndrome have high IL-1β and TLR1/2 expression.

Abstract

Hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) reside in localized microenvironments, or niches, in the bone marrow that provide key signals regulating their activity. A fundamental property of hematopoiesis is the ability to respond to environmental cues such as inflammation. How these cues are transmitted to HSPCs within hematopoietic niches is not well established. Here, we show that perivascular bone marrow dendritic cells (DCs) express a high basal level of Toll-like receptor-1 (TLR1) and TLR2. Systemic treatment with a TLR1/2 agonist induces HSPC expansion and mobilization. It also induces marked alterations in the bone marrow microenvironment, including a decrease in osteoblast activity and sinusoidal endothelial cell numbers. TLR1/2 agonist treatment of mice in which Myd88 is deleted specifically in DCs using Zbtb46-Cre show that the TLR1/2-induced expansion of multipotent HPSCs, but not HSPC mobilization or alterations in the bone marrow microenvironment, is dependent on TLR1/2 signaling in DCs. Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) is constitutively expressed in both murine and human DCs and is further induced after TLR1/2 stimulation. Systemic TLR1/2 agonist treatment of Il1r1−/− mice show that TLR1/2-induced HSPC expansion is dependent on IL-1β signaling. Single-cell RNA-sequencing of low-risk myelodysplastic syndrome bone marrow revealed that IL1B and TLR1 expression is increased in DCs. Collectively, these data suggest a model in which TLR1/2 stimulation of DCs induces secretion of IL-1β and other inflammatory cytokines into the perivascular niche, which in turn, regulates multipotent HSPCs. Increased DC TLR1/2 signaling may contribute to altered HSPC function in myelodysplastic syndrome by increasing local IL-1β expression.

Introduction

Under basal conditions, the majority of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) reside in specialized environments, or niches, within the bone marrow. Most hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are perivascular, where they are in close contact with endothelial cells and CXCL12-expressing mesenchymal stromal cells.1-4 We and others showed that bone marrow–resident dendritic cells (DCs) also reside in the perivascular niche.5,6 Bone marrow DCs express a distinct pattern of chemokine and cytokine receptors compared with splenic DCs, suggesting that bone marrow DCs may be uniquely adapted to regulate hematopoiesis in response to certain inflammatory signals.6 In this study, we characterized the role of bone marrow DCs in the hematopoietic response to Toll-like receptor 1/2 (TLR1/2) agonist treatment.

TLRs are a family of pattern recognition receptors that play a critical role in innate immunity.7 There is accumulating evidence that TLRs also regulate hematopoiesis, in part by regulating HSPC function. Systemic treatment with TLR4 or TLR2 agonists induces HSC proliferation and expansion.8-10 However, prolonged (4-6 weeks) treatment with a low-dose TLR4 agonist is associated with a loss of HSC repopulating and enhanced myeloid differentiation.11 Likewise, systemic TLR2 agonist exposure is associated with an expansion of phenotypic HSCs but a loss of HSC self-renewal capacity.8 There is also evidence implicating increased TLR signaling in the pathogenesis of certain hematopoietic malignancies (as reviewed by Monlish et al12). Of particular relevance to the current study, increased expression of TLR2 and its obligate coreceptors (TLR1 or TLR6) have been reported in CD34+ cells from patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS).13-15 Moreover, TLR2 stimulation of CD34+ cells in vitro impairs their erythroid differentiation.15 These observations have led to a clinical trial of the TLR2 antagonist, tomaralimab, in lower risk MDS (#NCT02363491).

There is evidence that TLRs regulate HSPCs by both cell-autonomous and cell non-autonomous mechanisms.12 Stimulation of HSPCs in vitro with TLR agonists induces cell cycling and myeloid differentiation, consistent with a cell-autonomous effect.9,16,17 Moreover, Herman et al8 used Tlr2−/− bone marrow chimeras to show that TLR2 agonists regulate HSCs, in part, cell autonomously. Takizawa et al18 used Tlr4−/− mice to show that pathogen-induced Tlr4 signaling in HSPCs promotes proliferation and loss of self-renewal capacity in a cell-autonomous manner. Conversely, most TLRs, including TLR1, TLR4, and TLR6, are expressed at relatively low levels in multipotent HPSCs compared with mature myeloid cells such as monocytes (http://servers.binf.ku.dk/bloodspot).19 TLR stimulation of innate immune cells leads to the production of inflammatory cytokines, which act indirectly to regulate HSPC function.12 For example, systemic TLR4 ligand administration induces HSPC mobilization by increasing granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) production from endothelial cells.20 Likewise, there is evidence that TLR2-induced regulation of HSPCs is mediated, in part, by inflammatory cytokine production.8

TLR2 partners with TLR1 or TLR6 to generate functional heterodimeric receptors. TLR1/2 and TLR2/6 dimers respond to distinct ligands, and evidence suggests that they may transmit distinct signals.21 In the current study, we provide evidence supporting a model in which TLR1/2 signaling in bone marrow DCs regulates HSPC function in part through increased interleukin-1β (IL-1β) expression. Moreover, using single-cell RNA sequencing, we show that IL1B and TLR1 expression is increased in bone marrow DCs from 4 patients with low-risk or very-low-risk MDS. Together, these data suggest that increased DC TLR1/2 signaling in MDS may contribute to altered HSPC function by increasing IL-1β expression.

Methods

Detailed methods are provided in the supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site). Specialized methods are highlighted here.

PAM3CSK4 administration

PAM3CSK4 (tlrl-pms; InvivoGen) was diluted in H2O and administered intraperitoneally at a dose of 100 μg per mouse or every other day for 1 to 3 doses.

DC culture

Bone marrow cells from wild-type mice were cultured in DC differentiation media (RPMI, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 100 U/mL penicillin and streptomycin plus 20 ng/mL murine GM-CSF and 10 ng/mL murine IL-4). Nonattached cells were removed and fresh media replaced at day 2. Loosely attached cells were collected by gentle trituration and replated in fresh media on day 7. On day 10 to 12, cells were stimulated with 10 ng/mL PAM3CSK4 alone or in combination with 1 ng/mL anakinra for 24 hours in stem cell media: StemPro-34 (#10639011; Gibco), penicillin-streptomycin (100 U/mL), l-glutamine (2 mM), murine stem cell factor (100 ng/mL), murine thrombopoietin (100 ng/mL), murine Flt3 ligand (50 ng/mL), and murine IL-3 (5 ng/mL). Cells were removed by centrifugation at 500g for 5 minutes to generate DC conditioned media (CM); IL-1β levels were assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (BMS6002; Invitrogen). Sorted HSCs (100 lineage– Sca1+ c-Kit+ CD150+ CD48– [LSK-SLAM] cells) were cultured in 96-well culture dishes containing 100 μL of DC CM.

For the human bone marrow cells, fresh bone marrow aspirate from healthy donors were red blood cell lysed and cultured in minimum essential medium-alpha modification, 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 U/mL at 1 million cells/mL with or without 10 ng/mL PAM3CSK4 for 24 hours. DCs (CD19– CD20– CD56– CD15– CD71– CD1C+ CLEC10+ FCER1A+) and monocytes (CD19– CD20– CD56– CD15– CD71– CD14+) were sorted and processed for RNA. For murine cells, bone marrow cells from wild-type C57BL/6 mice were cultured for 24 hours in media with vehicle alone, 10 ng/mL of PAM3CSK4, or 10 μg/mL of PGN-SA (InvivoGen). DCs or monocytes were sorted as described in the supplemental Methods and processed for RNA.

Statistical analyses

Statistical significance was determined by using Prism (version 9) (GraphPad Software). Unpaired t test, two-way analysis of variance, or an analysis of variance with Tukey’s honestly significant difference post hoc analysis was used to evaluate the significance of differences between 2 groups or multiple groups. All data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean.

Study approval

All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Washington University. Human samples were acquired after informed consent under institutional review board–approved protocols: (1) “tissue acquisition for analysis of genetic progression factors in hematologic diseases” (201011766); and (2) “Washington University healthy donor 061046” (201103258).

Results

Bone marrow resident DCs in mice constitutively express a high level of TLR1/2 and IL-1β

To assess TLR expression in myeloid cell populations, RNA sequencing was performed on sorted bone marrow DCs, monocytes, and macrophages. To facilitate the accurate sorting of these cell populations, we used Cx3cr1gfp/+ mice, which express high-level green fluorescent protein (GFP) in DCs and monocytes but not macrophages.22-24 We modified our previously reported sorting strategy to define the following myeloid cell populations in the bone marrow: (1) DCs, CX3CR1-GFPhigh MHCIIhigh CD11chigh Gr-1– B220– cells; (2) macrophages, CX3CR1-GFP– MHCIIhigh CD169+ Gr-1– B220– cells; and (3) monocytes, CX3CR1-GFPhigh CD115+, B220– (both Gr1-low and Gr1-high) cells (Figure 1A).6 Principal component analysis revealed that the 3 populations clustered independently (Figure 1B). A total of 519 genes were differentially expressed in bone marrow DCs compared with both monocytes and macrophages, including many genes previously shown to be expressed in monocyte-derived DCs (supplemental Table 1). Of note, within these bone marrow–resident myeloid cell populations, Tlr1 and Tlr2 expression was highest in DCs (Figure 1C). Indeed, Tlr1 messenger RNA (mRNA) expression in bone marrow DCs was 2.9- and 3.9-fold higher compared with that in bone marrow monocytes and macrophages, respectively. Consistent with these findings, TLR1 cell surface expression was significantly increased in DCs compared with monocytes, with no detectable expression lineage– Sca1+ c-Kit+ (LSK) cells or LSK CD150+ CD48– (SLAM) phenotypic HSCs (Figure 1D). Of note, high TLR2 cell surface expression also was observed in bone marrow DCs and monocytes, with lower but detectable expression in LSK cells and HSCs.

Bone marrow–resident DCs express high levels of TLRs and inflammatory cytokines. (A) Representative flow plots showing gating strategy using Cx3cr1gfp/+ mice to sort DCs (MHCIIhigh CD11chigh CX3CR1-GFPhigh Gr-1– B220–), monocytes (CD115+ CX3CR1-GFPhigh B220–), and macrophages (MHCIIhigh CD169+ CX3CR1-GFP– Gr-1– B220–) in the bone marrow. (B) Principal component analysis (PCA) of RNA-sequencing data. (C) Expression of TLR receptors (fragments per kilobase [FPKM]). (D) Represented flow plots showing TLR1 or TLR2 cell surface expression (left panels: fluorescence minus one control [FMO]). Mean fluorescent intensity (ΔMFI) compared with FMO controls in the indicated cell population. (E) Basal expression of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines implicated in MDS pathogenesis that are expressed with an FPKM >2 in DCs, monocytes, or macrophages. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance determined by using two-way analysis of variance (panels C and E) or one-way analysis of variance (panel D). ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Bone marrow–resident DCs express high levels of TLRs and inflammatory cytokines. (A) Representative flow plots showing gating strategy using Cx3cr1gfp/+ mice to sort DCs (MHCIIhigh CD11chigh CX3CR1-GFPhigh Gr-1– B220–), monocytes (CD115+ CX3CR1-GFPhigh B220–), and macrophages (MHCIIhigh CD169+ CX3CR1-GFP– Gr-1– B220–) in the bone marrow. (B) Principal component analysis (PCA) of RNA-sequencing data. (C) Expression of TLR receptors (fragments per kilobase [FPKM]). (D) Represented flow plots showing TLR1 or TLR2 cell surface expression (left panels: fluorescence minus one control [FMO]). Mean fluorescent intensity (ΔMFI) compared with FMO controls in the indicated cell population. (E) Basal expression of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines implicated in MDS pathogenesis that are expressed with an FPKM >2 in DCs, monocytes, or macrophages. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance determined by using two-way analysis of variance (panels C and E) or one-way analysis of variance (panel D). ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

We next examined expression of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines implicated in MDS pathogenesis. Of the 30 cytokines/chemokines reported to be differentially expressed in MDS,13 only 8 had basal expression (defined as fragments per kilobase >2) in any of the bone marrow myeloid cell populations (Figure 1E; supplemental Table 1). High basal expression of Il1b was only observed in bone marrow DCs. Conversely, basal expression of vascular endothelial growth factor α (Vegfa) and colony-stimulating factor-1 (Csf1) was highest in bone marrow macrophages. These data show that bone marrow–resident DCs, macrophages, and monocytes have unique basal TLR and inflammatory cytokine expression profiles, suggesting that they may play distinct roles in the response to specific TLR stimulation.

TLR1/2 agonist treatment of mice is associated with a loss of bone marrow DCs, expansion of phenotypic HSCs, and HSPC mobilization

Because TLR1/2 signaling has been implicated in MDS pathogenesis, we next assessed hematopoietic responses to the TLR1/2 agonist PAM3CSK4.8,25 Treatment with PAM3CSK4 (100 μg every other day for 3 doses) resulted in a significant decrease in bone marrow DCs, monocytes, and macrophages, whereas neutrophil (ie, polymorphonuclear neutrophil) numbers were modestly increased (Figure 2A-C). The reduction in bone marrow DCs may, in part, be due to their mobilization into the blood (supplemental Figure 1B). Herman et al8 previously reported that treatment with PAM3CSK4 induced a modest expansion in phenotypic HSCs and a more robust mobilization of HSPCs to the spleen. Consistent with these results, we observed a significant increase in bone marrow LSK cells and LSK-SLAM cells (Figure 2D-E; supplemental Figure 1A). We also observed significant mobilization of HSPCs to spleen and blood (Figure 2F-K). Cell cycle analysis performed 24 hours after the final does of PAM3CSK4 found that LSK cell cycling was increased, with a trend to decreased HSC quiescence (Figure 2L-N). All of the hematopoietic changes were transient, with recovery of B cells, monocytes, and DCs by 3 weeks and HSPCs by 6 weeks after stopping PAM3CSK4 treatment (supplemental Figure 1C-E).

TLR1/2 agonist treatment is associated with a loss of DCs and macrophages in the bone marrow and HSPC expansion and mobilization. Wild-type mice were treated with PAM3CSK4 (100 μg, every other day × 3 doses) and analyzed 24 hours after the final dose. (A) Total leukocytes per femur. (B-C) Number of the indicated cell type in the bone marrow (BM). Number of LSK (D) or LSK-SLAM (E) cells in the BM. Number of LSK (F) and LSK-SLAM (G) cells in the spleen (SP). (H) Number of LSK cells in the peripheral blood (PB). Number of colony-forming cell (CFC) in BM (I), SP (J), or PB (K). (L) Representative flow plots showing gating strategy to identify different stages of the cell cycle; data are gated on LSK cells. Cell cycle analysis of LSK (M) and LSK-SLAM (N) cells in the BM. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance determined by using two-way analysis of variance (panels B, C, M, and N) or unpaired t-test (panels A and D-K). ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Ctrl, control; PMN, polymorphonuclear neutrophil.

TLR1/2 agonist treatment is associated with a loss of DCs and macrophages in the bone marrow and HSPC expansion and mobilization. Wild-type mice were treated with PAM3CSK4 (100 μg, every other day × 3 doses) and analyzed 24 hours after the final dose. (A) Total leukocytes per femur. (B-C) Number of the indicated cell type in the bone marrow (BM). Number of LSK (D) or LSK-SLAM (E) cells in the BM. Number of LSK (F) and LSK-SLAM (G) cells in the spleen (SP). (H) Number of LSK cells in the peripheral blood (PB). Number of colony-forming cell (CFC) in BM (I), SP (J), or PB (K). (L) Representative flow plots showing gating strategy to identify different stages of the cell cycle; data are gated on LSK cells. Cell cycle analysis of LSK (M) and LSK-SLAM (N) cells in the BM. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance determined by using two-way analysis of variance (panels B, C, M, and N) or unpaired t-test (panels A and D-K). ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Ctrl, control; PMN, polymorphonuclear neutrophil.

TLR1/2 agonist treatment alters the bone marrow microenvironment in mice

HSPC mobilization by inflammatory cytokines/chemokines is mediated, in part, by alterations in the bone marrow microenvironment, including the loss of CXCL12 and stem cell factor (SCF) expression by mesenchymal stromal cells.26-28 However, total bone marrow mRNA expression of CXCL12 and SCF was unchanged after PAM3CSK4 treatment (Figure 3A). Conversely, osteocalcin (OCN) mRNA expression, a marker of active osteoblasts, was significantly reduced. To examine osteoblasts in more detail, we used Col2.3-GFP mice, which express GFP in osteoblasts.29 Treatment with PAM3CSK4 resulted in a modest but significant decrease in GFP+ PDGFRα+ (CD140a) lineage– osteoblasts (Figure 3B-C). Immunostaining of bone sections from PAM3CSK4-treated Col2.3-GFP mice confirmed the loss of GFP+ endosteal cells (Figure 3D-E). Interestingly, PAM3CSK4 treatment was also associated with a significant reduction in the thickness of the remaining GFP+ endosteal cells, which is a defining feature of bone-lining cells (Figure 3F).30 Consistent with a bone-lining phenotype, sorted GFP+ PDGFRα+ lineage– cells from PAM3CSK4-treated mice exhibited increased expression of ICAM1 and reduced expression of OCN (Figure 3G). In line with these findings, the number of OCN+ endosteal cells was reduced after PAM3CSK4 treatment (supplemental Figure 2). Interestingly, no difference in CXCL12 or SCF mRNA expression was observed in sorted GFP+ PDGFRα+ lineage– cells. In addition to osteoblasts, we observed a reduction in non-osteoblastic mesenchymal stromal cells (lineage– CD31– GFP– PDGFRα+ Sca1–) in the bone marrow after PAM3CSK4 treatment (Figure 3H-J).

TLR1/2 agonist treatment suppresses the osteoblast niche. Wild-type or Col2.3-GFP+ mice were treated with PAM3CSK4 (100 μg, every other day × 3 doses) and analyzed 24 hours after the final dose. (A) RNA expression from total bone marrow of the indicated gene relative to β-actin. (B) Representative flow plots showing gating strategy to identify Col2.3-GFP+ CD140a+ CD31– lineage– osteoblasts (Obs). (C) Quantification of Ob numbers by flow cytometry. (D) Representative immunofluorescence staining images of femur sections showing Col2.3-GFP (green) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue). (E) Ob number per millimeter bone perimeter. (F) Quantification of osteoblast thickness. (G) RNA expression of the indicated gene relative to β-actin from sorted Col2.3-GFP+ CD140a+ CD31– lineage– Obs. (H) Representative flow plots of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs; GFP– CD140a [PDGFRα]+ Sca1+ CD31– lineage–) and non-osteoblastic stromal cells (GFP– CD140a+ Sca1– CD31– lineage–). Quantification of MSCs (I) and non-osteoblastic stromal cells (J) by flow cytometry. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance determined by using unpaired t-test. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗∗P < .001. Ctrl, control; SSC-A, side scatter area.

TLR1/2 agonist treatment suppresses the osteoblast niche. Wild-type or Col2.3-GFP+ mice were treated with PAM3CSK4 (100 μg, every other day × 3 doses) and analyzed 24 hours after the final dose. (A) RNA expression from total bone marrow of the indicated gene relative to β-actin. (B) Representative flow plots showing gating strategy to identify Col2.3-GFP+ CD140a+ CD31– lineage– osteoblasts (Obs). (C) Quantification of Ob numbers by flow cytometry. (D) Representative immunofluorescence staining images of femur sections showing Col2.3-GFP (green) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue). (E) Ob number per millimeter bone perimeter. (F) Quantification of osteoblast thickness. (G) RNA expression of the indicated gene relative to β-actin from sorted Col2.3-GFP+ CD140a+ CD31– lineage– Obs. (H) Representative flow plots of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs; GFP– CD140a [PDGFRα]+ Sca1+ CD31– lineage–) and non-osteoblastic stromal cells (GFP– CD140a+ Sca1– CD31– lineage–). Quantification of MSCs (I) and non-osteoblastic stromal cells (J) by flow cytometry. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance determined by using unpaired t-test. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗∗P < .001. Ctrl, control; SSC-A, side scatter area.

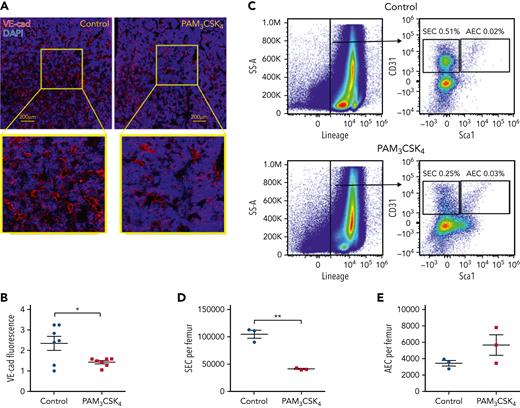

Activation of bone marrow endothelial cells has been linked to HSPC mobilization.6,31-33 Thus, we next examined the impact of PAM3CSK4 treatment on bone marrow sinusoidal and arteriolar endothelial cells. We observed a significant decrease in vascular endothelial–cadherin+ endothelial cells on bone sections taken from mice 24 hours after the final dose of PAM3CSK4 (Figure 4A-B). This observation was confirmed by flow cytometry, which revealed that the number of CD31+ Sca1– CD45– Ter119– sinusoidal endothelial cells (SECs), but not CD31+ Sca1+ CD45– Ter119– arteriolar endothelial cells (AECs), was significantly reduced (Figure 4C-E). Altogether, these results show that systemic treatment with a TLR1/2 ligand in mice induces marked changes in stromal cells that contribute to hematopoietic niches in the bone marrow, including a decrease in osteoblast number and activity and a decrease in mesenchymal stromal cell and SEC number.

TLR1/2 agonist treatment is associated with decreased bone marrow SECs. Wild-type mice were treated with PAM3CSK4 (100 μg, every other day × 3 doses) and analyzed 24 hours after the final dose. (A) Representative images of femur sections stained for vascular endothelial–cadherin (VE-cad; red) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue). (B) Quantification of the VE-cad signal by histomorphometry. (C) Representative flow plots showing gating strategy to identify CD31+ Sca1– CD45– Ter119– SECs and CD31+ Sca1+ CD45– Ter119– AECs. Quantification of SECs (D) and AECs (E). Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance determined by using an unpaired t-test. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01.

TLR1/2 agonist treatment is associated with decreased bone marrow SECs. Wild-type mice were treated with PAM3CSK4 (100 μg, every other day × 3 doses) and analyzed 24 hours after the final dose. (A) Representative images of femur sections stained for vascular endothelial–cadherin (VE-cad; red) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue). (B) Quantification of the VE-cad signal by histomorphometry. (C) Representative flow plots showing gating strategy to identify CD31+ Sca1– CD45– Ter119– SECs and CD31+ Sca1+ CD45– Ter119– AECs. Quantification of SECs (D) and AECs (E). Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance determined by using an unpaired t-test. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01.

TLR1/2-induced HSPC expansion, but not mobilization, is dependent on TLR signaling in bone marrow DCs in mice

TLR1 is not expressed on osteolineage or endothelial cells (https://compbio.nyumc.org/niche),34 and its expression in HSPCs is low,35 suggesting that the effects of TLR1/2 stimulation on these cell populations is non–cell intrinsic. Our data show that bone marrow DCs express the highest level of TLR1 (Figure 1D). To test the hypothesis that TLR1/2 signaling in bone marrow DCs may contribute to PAM3CSK4-induced changes in HSPCs and stromal cells, we generated Zbtb46-Cre, Myd88f/f mice. Of note, Zbtb46-Cre selectively targets DCs but not monocytes or macrophages.36 Because Myd88 is required for TLR1/2 signaling, DCs in these mice should be unresponsive to PAM3CSK4 stimulation. Because endothelial cells also express Zbtb46,37 we generated Zbtb46-Cre Myd88f/f or Myd88f/f (control) bone marrow chimeras to restrict the Myd88 loss to hematopoietic cells (Figure 5A). These bone marrow chimeras were treated with PAM3CSK4, and bone marrow DCs, monocytes, and macrophages were isolated to assess Myd88 deletion. As expected, a significant decrease in Myd88 mRNA was observed in DCs but not in monocytes or macrophages (Figure 5B). Treatment with PAM3CSK4 induced a significant increase in the number of LSK and LSK-SLAM cells in the bone marrow of control but not Zbtb46-Cre Myd88f/f chimeras (Figure 5C-D). Within the LSK population, the effect of PAM3CSK4 treatment was limited to the myeloid-biased multipotent progenitor-3 population, where it resulted in a significant increase in control but not Zbtb46-Cre Myd88f/f chimeras (Figure 5E). An analysis of committed myeloid progenitors showed that PAM3CSK4 treatment resulted in a modest expansion of granulocyte-monocyte progenitors (GMPs) in control chimeras that was attenuated, but still present, in Zbtb46-Cre Myd88f/f chimeras (Figure 5F). Conversely, PAM3CSK4-induced HSPC mobilization was similar in control and Zbtb46-Cre Myd88f/f chimeras (Figure 5G-H). Likewise, PAM3CSK4-induced decreases in bone marrow DCs and B cells and increases in neutrophils were not affected by the loss of Myd88 in DCs (supplemental Figure 3). Together, these data show that the expansion of phenotypic HSPCs, but not HSPC mobilization or myeloid expansion, induced by PAM3CSK4 is dependent on TLR1/2 signaling in DCs.

TLR signaling in bone marrow DCs contributes to TLR1/2 agonist–induced HSPC expansion. (A) Bone marrow from Zbtb46-Cre, Myd88f/f, or Myd88f/f mice were transplanted into irradiated wild-type recipient mice; 8 weeks later, mice were treated with PAM3CSK4 (100 μg, every other day × 3 doses) and analyzed 24 hours after the final dose. (B) Expression of Myd88 mRNA relative to β-actin mRNA from sorted bone marrow DCs, monocytes, and macrophages. Number of LSK (C) or LSK-SLAM (D) cells per femur. (E) Number of LSK Flk2– CD48+ CD150+ cells (multipotent progenitor-2 [MPP2]), LSK Flk2– CD48+ CD150– cells (MPP3), and LSK Flk2+ cells (MPP4) in the bone marrow. (F) Number of common myeloid progenitors (CMPs), GMPs, and megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors (MEPs) in bone marrow. (G) Number of colony-forming unit cells (CFU-C) per spleen. (H) Number of LSK cells per spleen. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance determined by using a one-way analysis of variance. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001.

TLR signaling in bone marrow DCs contributes to TLR1/2 agonist–induced HSPC expansion. (A) Bone marrow from Zbtb46-Cre, Myd88f/f, or Myd88f/f mice were transplanted into irradiated wild-type recipient mice; 8 weeks later, mice were treated with PAM3CSK4 (100 μg, every other day × 3 doses) and analyzed 24 hours after the final dose. (B) Expression of Myd88 mRNA relative to β-actin mRNA from sorted bone marrow DCs, monocytes, and macrophages. Number of LSK (C) or LSK-SLAM (D) cells per femur. (E) Number of LSK Flk2– CD48+ CD150+ cells (multipotent progenitor-2 [MPP2]), LSK Flk2– CD48+ CD150– cells (MPP3), and LSK Flk2+ cells (MPP4) in the bone marrow. (F) Number of common myeloid progenitors (CMPs), GMPs, and megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors (MEPs) in bone marrow. (G) Number of colony-forming unit cells (CFU-C) per spleen. (H) Number of LSK cells per spleen. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance determined by using a one-way analysis of variance. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001.

TLR1/2-induced alterations in osteoblasts and endothelial cells are not dependent on TLR signaling in bone marrow DCs in mice

To determine whether TLR1/2 signaling in bone marrow DCs also contributes to alterations in bone marrow stromal cells, we treated control or Zbtb46-Cre Myd88f/f chimeras with PAM3CSK4 and assessed osteoblasts and endothelial cells. Treatment with PAM3CSK4 induced a similar decrease in total bone marrow OCN mRNA expression in control and Zbtb46-Cre Myd88f/f chimeras (supplemental Figure 4A). Likewise, OCN expression, as measured by immunostaining of bone sections, showed a significant decrease in both cohorts (supplemental Figure 4B-C). The number of SECs and AECs was measured by using flow cytometry. A similar decrease in SECs was observed after PAM3CSK4 treatment in both control and Zbtb46-Cre Myd88f/f chimeras; no change in AECs was observed in either cohort (supplemental Figure 4D-E). These data suggest that TLR1/2 signaling in bone marrow DCs is not required for PAM3CSK4-induced alterations in the bone marrow microenvironment.

TLR1/2-induced HSPC expansion is dependent on IL-1 signaling in mice

To explore mechanisms by which DCs contribute to PAM3CSK4-induced HSPC expansion, we performed RNA-sequencing on sorted bone marrow DCs from Cx3cr1gfp/+ mice 24 hours after treatment with PAM3CSK4 (supplemental Table 2). Only 3 cytokines/chemokines were differentially expressed in bone marrow DCs after PAM3CSK4 treatment. Of particular interest is IL1b (Figure 6A), whose expression increased more than 6-fold from a relatively high baseline. Likewise, ex vivo treatment of murine bone marrow DCs with PAM3CSK4 or the TLR2 agonist PGN-SA (a peptidoglycan from Staphylococcus aureus) resulted in a significant increase in Il1b mRNA expression (supplemental Figure 5). Because IL1b has been implicated in the pathogenesis of MDS and other myeloid malignancies,13,38 and treatment with IL-1β results in an expansion of HSPCs and myeloid cells,39,40 we next examined the impact of the loss of IL-1 signaling on the hematopoietic changes induced by PAM3CSK4 in Il1r1−/− mice. The PAM3CSK4-induced increase in LSK cells, LSK-SLAM cells, and multipotent progenitor-3 cells was significantly reduced in Il1r1−/− mice, with a trend to decreased GMP (Figure 6B-E). To assess the impact of PAM3CSK4 treatment and IL-1 signaling on HSC function, serial competitive bone marrow transplantation assays were performed. In the primary transplant mice, no significant effect of PAM3CSK4 treatment on repopulating activity was observed (Figure 6F-G; supplemental Figure 6A-C). However, in secondary transplant mice, a trend to reduced HSPC donor chimerism in wild-type but not Il1r1−/− HSPCs treated with PAM3CSK4 was observed (Figure 6H-I; supplemental Figure 6D-F). These data suggest that PAM3CSK4 treatment suppresses HSC self-renewal capacity in an IL-1–dependent fashion.

Abrogation of IL-1 signaling attenuates TLR1/2 agonist-induced multipotent HSPC expansion. (A) DCs were sorted from the bone marrow of Cx3cr1gfp/+ mice treated with one dose of 100 μg PAM3CSK4, and RNA-sequencing was performed. Expression of selected inflammatory cytokines/chemokines is shown. LSK (B) or LSK-SLAM (C) cell number per femur. (D) Number of multipotent progenitor-2 (MPP2), MMP3, and MMP4 per femur. (E) Number of common myeloid progenitors (CMPs), GMPs, and megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors (MEPs) per femur. (F) Bone marrow cells from wild-type (WT) or Il1r1−/− (Ly5.2) mice treated with vehicle alone (Ctrl) or PAM3CSK4 were transplanted along with an equal number of WT competitor (Ly5.1) bone marrow. Shown is the percentage of Ly5.2 donor chimerism in peripheral blood. (G) LSK Ly5.2 donor chimerism 12 weeks after transplantation. (H) Peripheral blood Ly5.2 donor chimerism after secondary transplantation. (I) LSK Ly5.2 donor chimerism 12 weeks after secondary transplantation. (J) CM from bone marrow–derived DC cultures stimulated with vehicle alone (Ctrl), PAM3CSK4 (10 ng/mL) alone, or PAM3CSK4 with anakinra (1 μg/mL) was prepared. HSCs (LSK-SLAM cells) were sorted into the different DC CM and cultured for 7 days with supportive cytokines. (K) IL-1β protein level in DC CM. (L) Number of lineage-negative (CD11b– Gr1–) Kit+ cells on day 7 of culture. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance determined by using unpaired t-test (panels A and K), two-way analysis of variance (panels B-E and L), and one-way analysis of variance (panels G and I). ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001.

Abrogation of IL-1 signaling attenuates TLR1/2 agonist-induced multipotent HSPC expansion. (A) DCs were sorted from the bone marrow of Cx3cr1gfp/+ mice treated with one dose of 100 μg PAM3CSK4, and RNA-sequencing was performed. Expression of selected inflammatory cytokines/chemokines is shown. LSK (B) or LSK-SLAM (C) cell number per femur. (D) Number of multipotent progenitor-2 (MPP2), MMP3, and MMP4 per femur. (E) Number of common myeloid progenitors (CMPs), GMPs, and megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors (MEPs) per femur. (F) Bone marrow cells from wild-type (WT) or Il1r1−/− (Ly5.2) mice treated with vehicle alone (Ctrl) or PAM3CSK4 were transplanted along with an equal number of WT competitor (Ly5.1) bone marrow. Shown is the percentage of Ly5.2 donor chimerism in peripheral blood. (G) LSK Ly5.2 donor chimerism 12 weeks after transplantation. (H) Peripheral blood Ly5.2 donor chimerism after secondary transplantation. (I) LSK Ly5.2 donor chimerism 12 weeks after secondary transplantation. (J) CM from bone marrow–derived DC cultures stimulated with vehicle alone (Ctrl), PAM3CSK4 (10 ng/mL) alone, or PAM3CSK4 with anakinra (1 μg/mL) was prepared. HSCs (LSK-SLAM cells) were sorted into the different DC CM and cultured for 7 days with supportive cytokines. (K) IL-1β protein level in DC CM. (L) Number of lineage-negative (CD11b– Gr1–) Kit+ cells on day 7 of culture. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance determined by using unpaired t-test (panels A and K), two-way analysis of variance (panels B-E and L), and one-way analysis of variance (panels G and I). ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001.

To assess the impact of DC IL-1β on HSPCs, we cultured sorted wild-type HSCs (LSK-SLAM cells) with CM from bone marrow–derived DCs stimulated with PAM3CSK4 (Figure 6J). Of note, we confirmed that PAM3CSK4 treatment strongly induced IL-1β protein levels in DC CM (Figure 6K). DC CM supported the expansion of HSPCs that was significantly accentuated in cultures with PAM3CSK4–treated DC CM (Figure 6L; supplemental Figure 7). Importantly, the augmented HSC proliferation induced by PAM3CSK4–treated DC CM was abrogated by the addition of the IL-1 receptor antagonist anakinra. Collectively, these data suggest that PAM3CSK4 treatment induces an expansion of multipotent HSPCs, at least in part, by increasing IL-1β expression in bone marrow DCs.

Human bone marrow DCs express IL-1β that is induced by TLR1/2 activation and is increased in low-risk MDS

We next questioned whether human bone marrow DCs induce IL-1β expression in response to TLR1/2 stimulation. Single-cell RNA-sequencing was performed on cryopreserved bone marrow from 2 healthy donors and 4 cases of MDS, with low or very low scores on the revised International Prognostic Scoring System (Figure 7A; supplemental Table 3). Type 2–like DCs were identified as CD1C+, MHC class II-high, FCER1a+, and CLEC10A+ cells (Figure 7B). We developed a flow assay based on CD1C, FCER1A, and CLEC10A to identify and sort bone marrow DCs (Figure 7C). Bone marrow cells from healthy donors were treated overnight with PAM3CSK4, and then DCs and monocytes were sorted. Treatment with PAM3CSK4 strongly induced IL1B mRNA expression in human DCs but not in monocytes (Figure 7D). We next examined basal TLR1/2 and IL1B expression in bone marrow DCs and monocytes in MDS using the single-cell RNA-sequencing data. Expression of TLR1 and IL1B was significantly increased in DCs, CD14+ monocytes, and CD16+ monocytes, with increased TLR2 expression in CD14+ and CD16+ monocytes (Figure 7E; supplemental Figure 8). Altogether, these data show that human bone marrow resident DCs are a source of IL-1β that is inducible with TLR1/2 activation and is increased in at least some cases of low-risk MDS.

IL-1β expression in bone marrow DCs from healthy donors and patients with MDS. (A) Annotations of single-cell RNA-sequencing clusters from healthy donors and patients with MDS compared with reference data sets. (B) Expression of the indicated cDC2 marker genes. Bone marrow cells from 4 healthy donors were cultured overnight in PAM3CSK4 (10 ng/mL) or vehicle alone; DCs or monocytes were sorted by flow cytometry; and IL1B mRNA expression was quantified. (C) Representative flow plots showing gating strategy to identify human DC2-like cells. (D) IL1B mRNA expression data; significance determined by paired t-test. (E) Violin plots showing TLR1, TLR2, or IL1B mRNA expression in the indicated myeloid cell population; data are pooled single-cell RNA-sequencing data from 2 healthy donors (HD) and 4 patients with MDS. Significance determined by unpaired t-test. ∗P < .05, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ASDC, AXL+ DC; BaEoMa, basophil, eosinophil, mast cells; CLP, common lymphoid progenitor; Ctrl, control; EMP, erythrocyte megakaryocyte progenitor; ILC, innate lymphoid cell; NK, natural killer; pDC, precursor DC; pre-pDC, precursor plasmacytoid DC; Prog Mk, progenitor megakaryocytes; UMAP, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection.

IL-1β expression in bone marrow DCs from healthy donors and patients with MDS. (A) Annotations of single-cell RNA-sequencing clusters from healthy donors and patients with MDS compared with reference data sets. (B) Expression of the indicated cDC2 marker genes. Bone marrow cells from 4 healthy donors were cultured overnight in PAM3CSK4 (10 ng/mL) or vehicle alone; DCs or monocytes were sorted by flow cytometry; and IL1B mRNA expression was quantified. (C) Representative flow plots showing gating strategy to identify human DC2-like cells. (D) IL1B mRNA expression data; significance determined by paired t-test. (E) Violin plots showing TLR1, TLR2, or IL1B mRNA expression in the indicated myeloid cell population; data are pooled single-cell RNA-sequencing data from 2 healthy donors (HD) and 4 patients with MDS. Significance determined by unpaired t-test. ∗P < .05, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ASDC, AXL+ DC; BaEoMa, basophil, eosinophil, mast cells; CLP, common lymphoid progenitor; Ctrl, control; EMP, erythrocyte megakaryocyte progenitor; ILC, innate lymphoid cell; NK, natural killer; pDC, precursor DC; pre-pDC, precursor plasmacytoid DC; Prog Mk, progenitor megakaryocytes; UMAP, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection.

Discussion

Consistent with a prior report,8 we show that increasing systemic levels of a TLR1/2 agonist results in HSPC expansion and mobilization and a shift from lymphopoiesis to myelopoiesis. These hematopoietic changes are associated with marked alterations in the bone marrow microenvironment. Specifically, PAM3CSK4 treatment results in a decrease in SECs and osteolineage cells. It is also associated with a decrease in osteoblast activity, as evidenced by a reduction in osteoblast thickness and a decrease in osteocalcin expression. These latter features, along with increased ICAM1 expression, are consistent with the conversion of osteoblasts into bone-lining cells.30,41 Bone-lining cells are quiescent cells of the osteolineage that activate osteoclasts through production of RANK ligand.30,42 Of note, Kollet et al43 previously reported that increased osteoclast activity promotes HSPC mobilization. Whether the increase in bone-lining cells contributes to HSPC mobilization in response to TLR1/2 stimulation requires further study.

TLR1 is not expressed on either osteoblasts or bone marrow endothelial cells (https://compbio.nyumc.org/niche).34 Thus, PAM3CSK4 must act in a non–cell autonomous fashion to regulate these stromal cell populations. However, our Zbtb46-Cre Myd88f/f chimera data show that TLR1/2 signaling in DCs is not required to induce these changes. A prior study found that PAM3CSK4 treatment induces expression of G-CSF.8 This is relevant, as treatment with G-CSF suppresses osteoblasts in mice.44-46 There is evidence that macrophages are the target cell population that mediates G-CSF–induced osteoblast suppression.47,48 Whether increased G-CSF signaling in macrophages mediates osteoblast suppression and/or the other alterations in bone marrow stromal cells induced by TLR1/2 agonist treatment requires further study.

We found that TLR1/2 signaling in DCs mediates the expansion of multipotent HSPCs (LSK cells) but not the expansion of myeloid lineage–restricted progenitors (ie, GMPs) or mature myeloid cells. Bone marrow DCs localize to the perivascular niche, where the majority of HSCs reside.2,3,34 In contrast, GMPs are more broadly distributed in the bone marrow,49 and lymphoid progenitors localize to the endosteum.50 These observations suggest that TLR1/2 signaling in bone marrow DCs produce factors such as IL-1β that alter the localized microenvironment of the perivascular niche and affect multipotent HSPC function. Lineage-restricted progenitors that reside outside of the perivascular niche may not be exposed, at least at the same level, to factors produced by DCs. We acknowledge that, in addition to bone marrow–resident DCs, Zbtb46-Cre targets DCs throughout the body. Thus, signals generated by DCs outside of the bone marrow may contribute to the observed hematopoietic phenotype. It is also worth noting that in the Zbtb46-Cre Myd88 chimeric mice, all TLR signaling in DCs is likely to be altered by the loss of Myd88. Thus, although PAM3CSK4 is believed to be a specific TLR1/2 agonist, it is possible that the loss of other TLR signaling in DCs (triggered indirectly by PAM3CSK4) may contribute to the observed hematopoietic phenotypes.

Both TLR1/2 and TLR4 agonists mobilize HSPCs, at least in part, in a non–cell autonomous fashion.8,20 Herman et al8 reported that treatment with PAM3CSK4 induces an increase in serum G-CSF. However, G-CSF induces HSPC mobilization primarily by suppressing stromal cell expression of CXCL12,45,51,52 and no change in total bone marrow CXCL12 was observed in mice after PAM3CSK4 treatment. Thus, it is unlikely that increased G-CSF is the primary mechanism by which TLR1/2 agonists induce HSPC mobilization. Of note, we recently reported that ablation of DCs induces HSPC mobilization by activating endothelial cells in a CXCR2-dependent fashion.6 However, PAM3CSK4 treatment did not induce an increase in DC CXCR1/2 ligands expression and, in contrast to DC ablation, SECs are decreased, not increased. Therefore, the mechanisms by which TLR1/2 stimulation induces HSPC mobilization are unclear.

Our data suggest that DCs are an important source of IL-1β in both murine and human bone marrow under steady-state conditions, which is further increased after TLR1/2 stimulation. Consistent with this conclusion, a recent study showed that microbiota stimulate the expression of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, in CX3CR1+ mononuclear cells in a TLR-dependent fashion that, in turn, results in HSPC expansion.53 Of note, CX3CR1+ mononuclear cells include DCs and monocytes. Whether microbiota-induced activation of TLR1/2 signaling in DCs contributes to HSPC expansion is unclear. Of note, Arranz et al38 reported that HSPCs carrying JAK2V617F also are an important source of IL-1β and contribute to the development of a myeloproliferative phenotype by targeting sympathetic nerves in the perivascular niche. There is considerable data showing that IL-1β directly regulates HSPC function. Pietras et al40 showed that prolonged treatment with IL-1β (for 20 days) results in the expansion of HSCs and multipotent progenitor cells and enhances the myeloid differentiation of HSCs. Kovtonyuk et al54 recently reported that IL-1β contributes to the microbiome-dependent expansion of myeloid-biased HSCs with aging. We found that increased IL-1β expression from TLR1/2-stimulated DCs directly induces the proliferation of sorted murine HSCs. Accordingly, genetic ablation of IL-1 signaling blocks PAM3CSK4-induced multipotent HSPC expansion and prevents PAM3CSK4-induced loss of HSC self-renewal capacity. Together, these data suggest that perivascular DCs are poised to respond early to increases in the circulation of inflammatory mediators such as TLR1/2 ligands. The localized release of cytokines, chemokines, and other factors by activated DCs into the perivascular niche may contribute to the regulation of HSPC function in both steady-state and stress conditions.

There is evidence that increased TLR1/2 signaling may contribute to MDS pathogenesis. Specifically, TLR1 and TLR2 expression is increased in patients with MDS,13-15 and TLR2 stimulation of CD34+ cells in vitro impairs their erythroid differentiation.15 Our single-cell RNA-sequencing data show that TLR1, TLR2, and IL1B mRNA expression is significantly increased in DCs and monocytes in at least a subset of patients with low-risk MDS. Although confirmation in a larger cohort of patients with MDS is needed, our data raise the possibility that TLR1/2-induced expression of IL-1β by DCs may contribute to altered HSPC function in MDS.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (PO1CA101937, D.C.L. and M.J.W.), the Taub Foundation Grants Program for Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS) Research (D.C.L.), the Siteman Cancer Center and the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital Cancer Fund (M.J.W.), and the Edward P. Evans Foundation. G.M. is supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (AR076758), and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI161022).

Authorship

Contribution: S.L., J.-C.Y., K.A.O., and D.C.L. conceived the study; S.L., J.-C.Y., and K.A.O. performed the majority of the experiments and analyzed the data; J.Z. and A.P.S. helped with transplantation and sample collection; K.A.O., J.X., J.R.K., N.M.H., R.S.F., S.E.H., T.J.L., and M.J.W. provided tissue samples or assisted with RNA-sequencing analyses; I.R.T. and G.M. provided essential experimental reagents; and S.L., J.-C.Y., K.A.O., and D.C.L. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Daniel C. Link, Division of Oncology, Department of Medicine, 660 South Euclid Ave, Campus Box 8007, St. Louis, MO 63110; e-mail: danielclink@wustl.edu.

References

Author notes

∗S.L. and J.-C.Y. contributed equally to the study.

The bulk RNA-sequencing data are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE201544). The single-cell RNA-sequencing data from healthy donors and patients with MDS are available at the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (accession number phs000159).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

![Bone marrow–resident DCs express high levels of TLRs and inflammatory cytokines. (A) Representative flow plots showing gating strategy using Cx3cr1gfp/+ mice to sort DCs (MHCIIhigh CD11chigh CX3CR1-GFPhigh Gr-1– B220–), monocytes (CD115+ CX3CR1-GFPhigh B220–), and macrophages (MHCIIhigh CD169+ CX3CR1-GFP– Gr-1– B220–) in the bone marrow. (B) Principal component analysis (PCA) of RNA-sequencing data. (C) Expression of TLR receptors (fragments per kilobase [FPKM]). (D) Represented flow plots showing TLR1 or TLR2 cell surface expression (left panels: fluorescence minus one control [FMO]). Mean fluorescent intensity (ΔMFI) compared with FMO controls in the indicated cell population. (E) Basal expression of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines implicated in MDS pathogenesis that are expressed with an FPKM >2 in DCs, monocytes, or macrophages. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance determined by using two-way analysis of variance (panels C and E) or one-way analysis of variance (panel D). ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/140/14/10.1182_blood.2022016084/4/m_blood_bld-2022-016084-gr1.jpeg?Expires=1769087266&Signature=mkAXIKQO5LAEWb~oE1K-MzDUC3iLjruGYH5eYpUlvmUE8YaqDxxTUW2r5iNiRVcFI~HT6QoNbBtdPaBFO4PoWV~kUNq0jQkAc0rBtj1jnUqiVpSWpmMXpkDsRtFctK3exvISHmHplrmf0NgMrTF~QQQ70j5qYvXCRTVTm46rtG2J2JsGP6VRWFM-LYsYNd1fWyhUWhh0pAn5rWz4Nx16ocbWMmE3Qk4Qfyd0DPMQrc9deVLVmZtqUHNVVuDXdErZu5Yd5A3KtwoQvEmgpul1hYtUQ5753ajxQNs6NiiwokCqk3kQf50l80cWCthScz1~4iupwBQwBQ5CqDrsMaO1eg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![TLR1/2 agonist treatment suppresses the osteoblast niche. Wild-type or Col2.3-GFP+ mice were treated with PAM3CSK4 (100 μg, every other day × 3 doses) and analyzed 24 hours after the final dose. (A) RNA expression from total bone marrow of the indicated gene relative to β-actin. (B) Representative flow plots showing gating strategy to identify Col2.3-GFP+ CD140a+ CD31– lineage– osteoblasts (Obs). (C) Quantification of Ob numbers by flow cytometry. (D) Representative immunofluorescence staining images of femur sections showing Col2.3-GFP (green) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue). (E) Ob number per millimeter bone perimeter. (F) Quantification of osteoblast thickness. (G) RNA expression of the indicated gene relative to β-actin from sorted Col2.3-GFP+ CD140a+ CD31– lineage– Obs. (H) Representative flow plots of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs; GFP– CD140a [PDGFRα]+ Sca1+ CD31– lineage–) and non-osteoblastic stromal cells (GFP– CD140a+ Sca1– CD31– lineage–). Quantification of MSCs (I) and non-osteoblastic stromal cells (J) by flow cytometry. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance determined by using unpaired t-test. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗∗P < .001. Ctrl, control; SSC-A, side scatter area.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/140/14/10.1182_blood.2022016084/4/m_blood_bld-2022-016084-gr3.jpeg?Expires=1769087266&Signature=U1d0FeV6iF5tesp0b3uGF8Fl~HaCc0IvvUDEhEzNcM9enbuJGLdTZpWoiFMkTMY5OaHTzy4DI5TjyN1QECWfDXhpVNnUtolhMrNc2mnnP1169cEQtx25NN8kgDP-HUHopV9-noDDf-HGXioAvS5T9JSi6j-8FNgK393CtRJ-9jx6fzFs57BC6jKdJC~5XHuDgt6XqdYibzWapHc7Rz53Z7UAjxePNnZ5ZXIq~sTejMNzgWV7Ni-MOsyUxQvhRUqVfGOs2x2U68QUqate8NbIsUX3e6NS~14sOQAmTowywPZijTtHMwLYLqzOo~bblqlsemyn9StVcxiJz3EQAbUtaw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![TLR signaling in bone marrow DCs contributes to TLR1/2 agonist–induced HSPC expansion. (A) Bone marrow from Zbtb46-Cre, Myd88f/f, or Myd88f/f mice were transplanted into irradiated wild-type recipient mice; 8 weeks later, mice were treated with PAM3CSK4 (100 μg, every other day × 3 doses) and analyzed 24 hours after the final dose. (B) Expression of Myd88 mRNA relative to β-actin mRNA from sorted bone marrow DCs, monocytes, and macrophages. Number of LSK (C) or LSK-SLAM (D) cells per femur. (E) Number of LSK Flk2– CD48+ CD150+ cells (multipotent progenitor-2 [MPP2]), LSK Flk2– CD48+ CD150– cells (MPP3), and LSK Flk2+ cells (MPP4) in the bone marrow. (F) Number of common myeloid progenitors (CMPs), GMPs, and megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors (MEPs) in bone marrow. (G) Number of colony-forming unit cells (CFU-C) per spleen. (H) Number of LSK cells per spleen. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance determined by using a one-way analysis of variance. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/140/14/10.1182_blood.2022016084/4/m_blood_bld-2022-016084-gr5.jpeg?Expires=1769087266&Signature=ik8n6bl2XPB2UlYbK7A1BYlXkALvh2JvH-QwUHT0U8CTXlWtVJs0RkmbM8yqgnAloa9r7B-H0SetK496R0PHVnahTVFsxvBnNE6QW0mxrKk4TOiDCA1e8a5secvULFQ8FaPJufItrWBNGw~xT8x7rT7nCvv1RoDKDi2~mMZkD6XWquq0jRC9OhwiV1z5H-V7GjTODpgg6coQxzuj7G9xkFsWT7cqM~Fs3jjmxAOynh1ZyQYos5EzrLITjRaxXOPUHXUifUEaSCUJEarOtwgQhbzQVOUwBMU-UxWKb6Dh8eBs1EjryeNvGMUXLJmO4LRdizj0-7wYJ7QMx-W~nfZ-6Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal