Key Points

p.Met41Val genotype and transfusion dependence are risks for decreased survival in VEXAS syndrome; ear chondritis confers better prognosis.

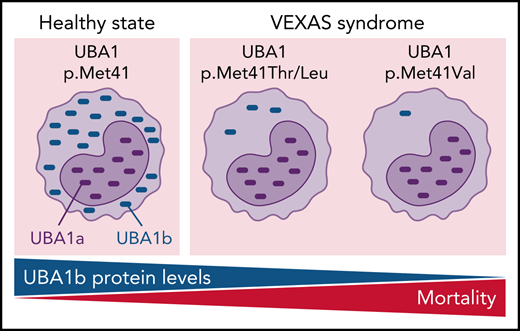

Differences in disease severity of VEXAS syndrome are linked with residual translation of the cytoplasmic isoform of UBA1 (UBA1b).

Abstract

Somatic mutations in UBA1 cause vacuoles, E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme, X-linked, autoinflammatory somatic (VEXAS) syndrome, an adult-onset inflammatory disease with an overlap of hematologic manifestations. VEXAS syndrome is characterized by a high mortality rate and significant clinical heterogeneity. We sought to determine independent predictors of survival in VEXAS and to understand the mechanistic basis for these factors. We analyzed 83 patients with somatic pathogenic variants in UBA1 at p.Met41 (p.Met41Leu/Thr/Val), the start codon for translation of the cytoplasmic isoform of UBA1 (UBA1b). Patients with the p.Met41Val genotype were most likely to have an undifferentiated inflammatory syndrome. Multivariate analysis showed ear chondritis was associated with increased survival, whereas transfusion dependence and the p.Met41Val variant were independently associated with decreased survival. Using in vitro models and patient-derived cells, we demonstrate that p.Met41Val variant supports less UBA1b translation than either p.Met41Leu or p.Met41Thr, providing a molecular rationale for decreased survival. In addition, we show that these 3 canonical VEXAS variants produce more UBA1b than any of the 6 other possible single-nucleotide variants within this codon. Finally, we report a patient, clinically diagnosed with VEXAS syndrome, with 2 novel mutations in UBA1 occurring in cis on the same allele. One mutation (c.121 A>T; p.Met41Leu) caused severely reduced translation of UBA1b in a reporter assay, but coexpression with the second mutation (c.119 G>C; p.Gly40Ala) rescued UBA1b levels to those of canonical mutations. We conclude that regulation of residual UBA1b translation is fundamental to the pathogenesis of VEXAS syndrome and contributes to disease prognosis.

Introduction

The recent discovery of vacuoles, E1 enzyme, X-linked, autoinflammatory, somatic (VEXAS) syndrome demonstrates how molecular diagnostics can reshape disease taxonomy.1 VEXAS syndrome connects a spectrum of seemingly unrelated systemic inflammatory and hematologic features into a new disease defined by lineage-restricted somatic mutations in hematologic progenitor cells in the gene UBA1, encoding the master enzyme of cellular ubiquitylation. The majority of disease-defining mutations are restricted to p.Met41, the translation initiation codon for UBA1b,2-4 leading to a loss of the normally active cytoplasmic isoform with emergence of an enzymatically impaired, novel isoform (UBA1c).1 Severe, treatment-refractory systemic inflammation coupled with progressive bone marrow failure makes VEXAS syndrome an often-fatal disease. Bone marrow transplant has been proposed as curative; however, selection of appropriate candidates for transplant is challenging due to the heterogeneity of the disease, older age at disease onset, associated comorbidities, and risks of transplant.5 The study objective was to identify predictors of survival in VEXAS syndrome to inform patient-specific approaches to treatment and define mechanistic relationships that govern associations between genetic variants in UBA1 and clinical outcomes.

Methods

Patient population

Patients with clinically suspected VEXAS syndrome1 referred to 2 academic institutions (National Institutes of Health and Leeds Teaching Hospital, United Kingdom) for diagnostic testing who had mutations in UBA1 at p.Met 41 were included in this study. Patients with other previously reported pathogenic mutations in UBA1, including c.118-1G>C (2 individuals), c.118-2A>C (2 individuals), and c.167 C>T;p.Ser56Phe (1 individuals), were excluded from this analysis due to small sample size. All patients provided written informed consent in study protocols approved by ethics review at the respective institutions.

Clinical data acquisition

Clinical and laboratory data were collected by systematic review of the medical records. Confirmation of clinical symptoms was obtained whenever possible by communicating with the patients via video telehealth visits, telephone interviews, or direct clinical evaluation.

Genetic testing

Presence of VEXAS-defining genetic mutations in UBA1 were detected by Sanger sequencing of peripheral blood and bone marrow samples as previously described.1 Briefly, coding exons of UBA1 were sequenced using the BigDye Terminator v1.1 Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer's instructions. Sequencing was performed on a Seq Studio Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Sequencing data were analyzed using Sequencher (Gene Codes). Patients were identified as positive for pathogenic mutations via manual review of Sanger sequencing with agreement between 2 independent reviewers. Sanger sequencing has a false negative rate of <1% for VEXAS syndrome, as compared with amplicon-based sequencing, in our cohort (data not shown). For a subset of patients with available samples, the variant allele frequency (VAF) of UBA1 mutations was quantified by error-corrected sequencing with a limit of detection of 0.5% (minimum deduplication ratio of 3:1). Exon 3 of UBA1 was sequenced at an average coverage of 2000× (500× deduplicated reads) in a NovaSeq 6000 instrument (Illumina, CA).

Clinical definitions

Definitions of organ involvement, symptoms, and hematologic abnormalities are provided in supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site). The revised International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS-R) was calculated as previously described.6 Clinical diagnoses were confirmed by applying available classification or diagnostic criteria as follows: relapsing polychondritis: McAdam’s7 or Damiani’s8 diagnostic criteria; Sweet syndrome: skin biopsy demonstrating a predominantly neutrophilic dermal infiltrate in the absence of infection; myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS): World Health Organization criteria9,10; and undifferentiated inflammatory syndrome: elevated inflammatory markers and systemic symptoms without meeting criteria for a specific clinical diagnosis.

Survival analysis

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to evaluate overall survival. Time to event was defined as the difference in years between age at the onset of the first symptom attributed to disease and age at death. The study period end date was 10 May 2021. Differences in survival were compared between subgroups of patients using the log-rank test.

Cox proportional hazards models were used to identify VEXAS-related features independently associated with survival. The proportional hazard assumption was assessed by visual assessment of the Kaplan-Meier curves. Disease-relevant predictor variables were chosen to represent the following categories: clinical manifestations (age of disease onset and any clinical manifestation with a prevalence of 10% or more), genotype (eg, leucine [Leu], valine [Val], or threonine [Thr] missense mutation at codon 41), clinical diagnosis (relapsing polychondritis, undifferentiated fever syndrome, Sweet syndrome, and MDS), and transfusion dependence. Transfusion dependence was defined as requiring red blood cells transfusions >3 times in a consecutive period of 6 months. Because bone marrow failure and MDS typically occurs later in the course of the VEXAS syndrome, transfusion dependence and development of MDS were modeled as time-varying covariates. Univariable associations were studied, and only predictor variables associated with survival at P < .05 were retained for consideration in multivariable models. Interaction terms were modeled within the multivariable analyses as appropriate.

The association of VEXAS-related disease features with time to transfusion dependence was also modeled using Cox proportional hazards. Time to transfusion dependence was chosen as an outcome measure of interest as a surrogate marker for bone marrow failure, a defining feature of the VEXAS syndrome. For patients that did not become transfusion dependent, the study period end date was set as 10 May 2021. The same predictor variables studied in association with survival were investigated in association with time to transfusion dependence. Death was modeled as a competing risk.

Translation reporter and immunoblotting

UBA1b translational reporter constructs consisting of a pCS2+ backbone and a bicistronic translational reporter were generated by Gibson assembly and Q5 site-directed mutagenesis (NEB). The first cistron of these reporters is translated in a CAP-dependent mechanism and encodes for C-terminally HA-tagged UBA1 constructs varied in p.Met41 and mutated at p.Met1 and p.Met67 (to suppress UBA1a and UBA1c translation and thus allowing for sensitive quantification of UBA1b by anti-HA immunoblotting). The second cistron is translated using an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) and encodes for a C-terminally HA-tagged MBP, which is used for normalization. HEK293T cells were transfected with translational reporters using Lipofectamine 3000 or polyethyleneimine (PEI) and grown for 24 hours, and cells were lysed in 2× Laemmli buffer. Lysates were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and analyzed by anti-HA immunoblotting. Relative UBA1b translation was calculated by normalizing the signal intensity of UBA1 to the one of MBP for each condition. Relative UBA1b translation for wild-type (WT) UBA1 was set to 100%. Immunoblots were quantified by ImageJ. To allow for quantification of UBA1b in the linear range, 10- to 20-fold less lysate was loaded for the WT UBA1b reporter. Immunoprecipitations were performed using Flag beads (Sigma M2), and detection was performed with anti-HA antibody (Biolegend 16B12). UBA1a and UBA1a/b antibodies used were from Cell Signaling. Similar detection was performed on magnetic activated cell sorting (MACS) (Miltenyi) purified patient cells.

Generation of UBA1a/b-specific monoclonal antibodies

UBA1a/b-specific monoclonal antibodies were generated using the custom monoclonal antibody service from GenScript using UBA1a protein as immunogen. Hybridoma clones were screened by immunoblotting for recognizing recombinant UBA1a and UBA1b but not UBA1c. Positive clones producing desired antibodies were expanded, and antibodies were purified from the hybridoma supernatant using CL350 CELLine bioreactors (Abnova).

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using JMP 14.0.0., Graphpad Prism 8, or Python (v3.6.10) package Lifelines (v0.25.11). Categorical and continuous variables were compared using the χ2 or Kruskal-Wallis test. Continuous variables were reported as mean plus or minus standard deviation or as the median (interquartile), as appropriate. For reporter assays, 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were performed. Nonparametric variables were compared between 2 groups using the Mann-Whitney U test. Survival analysis results are reported as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 83 patients with genetically confirmed VEXAS syndrome with pathogenic variants in UBA1 at p.Met41 were included in this analysis. There were no significant genetic, clinical, or therapeutic differences between patients enrolled at the National Institutes of Health (n = 71) vs Leeds University (n = 12). All patients were male and Caucasian. The median age at symptom onset was 66 years (absolute range, 41-80). All patients were treated with glucocorticoids. The mean number of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) prescribed was 2.6 (range, 0-12). Five patients received hypomethylating agents, and no patient underwent allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation during this study. The most commonly assigned clinical diagnosis was relapsing polychondritis (52%, n = 43), followed by Sweet syndrome (22%, n = 18), whereas 23% (n = 19) of the patients did not meet criteria for any clinical diagnosis. Myelodysplastic syndrome was diagnosed in 31% (n = 26) of the patients. Among patients with MDS, IPSS-R scores were available in 23 patients, categorized as follows: very low risk (n = 9); low risk (n = 11); intermediate risk (n = 0); or high risk (n = 2). Next-generation sequencing was available in 17 patients; 59% of the patients had no MDS-associated mutations (supplemental Table 2). The most prevalent clinical manifestations were fever (83%), skin involvement (82%), arthritis (58%), pulmonary infiltrates (57%), ear chondritis (54%), unprovoked deep vein thrombosis (DVT) (41%), periorbital edema (30%), hearing loss (29%), and inflammatory eye disease (24%) (Table 1). Macrocytic anemia (97%, n = 81) and thrombocytopenia (48%, n = 40) was prevalent in the cohort. Twenty-one out of 26 patients with MDS (81%) had associated thrombocytopenia. The genetic missense variants at codon 41 resulted in an amino acid substitution of a methionine for a leucine (Leu) (c.121 A>C; p. Met41Leu) in 15 individuals (18%), a valine (Val) (c.121 A>G; p. Met41Val) in 18 individuals (22%), or a threonine (Thr) (c.122 T>C; p. Met41Thr) in 50 individuals (60%).

Study population characteristics stratified by genotype

| . | Total cohort (n = 83) . | Leu variant (n = 15) . | Val variant (n = 18) . | Thr variant (n = 50) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age of disease onset median (range) | 66 (41-80) | 66 (55-74) | 65 (50-72) | 66 (42-80) | .97 |

| Sex, n (%) | 83 (100) | 15 (100) | 18 (100) | 50 (100) | 1.00 |

| White, n (%) | 83 (100) | 15 (100) | 18 (100) | 50 (100) | 1.00 |

| Clinical diagnosis | |||||

| Relapsing polychondritis, n (%) | 43 (52) | 8 (53) | 4 (22) | 31 (62) | .01 |

| Undifferentiated fever syndrome, n (%) | 19 (23) | 1 (6) | 10 (55) | 8 (16) | <.01 |

| Sweet syndrome, n (%) | 18 (22) | 9 (60) | 2 (11) | 7 (14) | <.01 |

| MDS, n (%) | 26 (31) | 5 (33) | 8 (44) | 13 (26) | .35 |

| Clinical manifestations, n (%) | |||||

| Fever | 69 (83) | 13 (87) | 17 (94) | 39 (78) | .25 |

| Skin involvement | 68 (82) | 13 (87) | 15 (83) | 40 (80) | .82 |

| Arthritis | 48 (58) | 8 (53) | 10 (55) | 30 (60) | .87 |

| Pulmonary infiltrates | 47 (57) | 10 (67) | 10 (55) | 27 (54) | .67 |

| Ear chondritis | 45 (54) | 8 (53) | 4 (22) | 33 (66) | <.01 |

| Unprovoked DVT | 34 (41) | 9 (60) | 6 (33) | 19 (38) | .24 |

| Nose chondritis | 30 (36) | 5 (33) | 3 (16) | 21 (42) | .13 |

| Periorbital edema | 25 (30) | 3 (20) | 10 (55) | 12 (24) | .03 |

| Hearing loss | 24 (29) | 7 (47) | 4 (22) | 13 (26) | .25 |

| Ocular inflammation | 20 (24) | 1 (6) | 1 (5) | 18 (36) | <.01 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 11 (13) | 2 (13) | 4 (22) | 5 (10) | .45 |

| Pleural effusion | 11 (13) | 2 (13) | 4 (22) | 5 (10) | .45 |

| Orchitis | 10 (12) | 0 (0) | 4 (22) | 6 (12) | .07 |

| Airway chondritis | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | .60 |

| Number of DMARDs, median (IQR) | 2 (1-4) | 3 (1-5) | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-4) | .62 |

| Hematologic manifestations | |||||

| IPSS-R score*, n (%) | |||||

| Very low risk | 9 (39) | 1 (11) | 2 (22) | 6 (66) | .72 |

| Low risk | 12 (52) | 2 (16) | 4 (33) | 6 (50) | .77 |

| Intermediate risk | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A |

| High risk | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | .67 |

| Very high risk | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A |

| Macrocytic anemia, n (%) | 81 (97) | 15 (100) | 18 (100) | 48 (96) | .35 |

| Thrombocytopenia, n (%) | 40 (83) | 7 (47) | 8 (44) | 25 (50) | .71 |

| UBA1 VAF median (IQR)† | 75 (57-85) | 64 (47-83) | 72 (52-86) | 76 (69-86) | .43 |

| . | Total cohort (n = 83) . | Leu variant (n = 15) . | Val variant (n = 18) . | Thr variant (n = 50) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age of disease onset median (range) | 66 (41-80) | 66 (55-74) | 65 (50-72) | 66 (42-80) | .97 |

| Sex, n (%) | 83 (100) | 15 (100) | 18 (100) | 50 (100) | 1.00 |

| White, n (%) | 83 (100) | 15 (100) | 18 (100) | 50 (100) | 1.00 |

| Clinical diagnosis | |||||

| Relapsing polychondritis, n (%) | 43 (52) | 8 (53) | 4 (22) | 31 (62) | .01 |

| Undifferentiated fever syndrome, n (%) | 19 (23) | 1 (6) | 10 (55) | 8 (16) | <.01 |

| Sweet syndrome, n (%) | 18 (22) | 9 (60) | 2 (11) | 7 (14) | <.01 |

| MDS, n (%) | 26 (31) | 5 (33) | 8 (44) | 13 (26) | .35 |

| Clinical manifestations, n (%) | |||||

| Fever | 69 (83) | 13 (87) | 17 (94) | 39 (78) | .25 |

| Skin involvement | 68 (82) | 13 (87) | 15 (83) | 40 (80) | .82 |

| Arthritis | 48 (58) | 8 (53) | 10 (55) | 30 (60) | .87 |

| Pulmonary infiltrates | 47 (57) | 10 (67) | 10 (55) | 27 (54) | .67 |

| Ear chondritis | 45 (54) | 8 (53) | 4 (22) | 33 (66) | <.01 |

| Unprovoked DVT | 34 (41) | 9 (60) | 6 (33) | 19 (38) | .24 |

| Nose chondritis | 30 (36) | 5 (33) | 3 (16) | 21 (42) | .13 |

| Periorbital edema | 25 (30) | 3 (20) | 10 (55) | 12 (24) | .03 |

| Hearing loss | 24 (29) | 7 (47) | 4 (22) | 13 (26) | .25 |

| Ocular inflammation | 20 (24) | 1 (6) | 1 (5) | 18 (36) | <.01 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 11 (13) | 2 (13) | 4 (22) | 5 (10) | .45 |

| Pleural effusion | 11 (13) | 2 (13) | 4 (22) | 5 (10) | .45 |

| Orchitis | 10 (12) | 0 (0) | 4 (22) | 6 (12) | .07 |

| Airway chondritis | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | .60 |

| Number of DMARDs, median (IQR) | 2 (1-4) | 3 (1-5) | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-4) | .62 |

| Hematologic manifestations | |||||

| IPSS-R score*, n (%) | |||||

| Very low risk | 9 (39) | 1 (11) | 2 (22) | 6 (66) | .72 |

| Low risk | 12 (52) | 2 (16) | 4 (33) | 6 (50) | .77 |

| Intermediate risk | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A |

| High risk | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | .67 |

| Very high risk | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A |

| Macrocytic anemia, n (%) | 81 (97) | 15 (100) | 18 (100) | 48 (96) | .35 |

| Thrombocytopenia, n (%) | 40 (83) | 7 (47) | 8 (44) | 25 (50) | .71 |

| UBA1 VAF median (IQR)† | 75 (57-85) | 64 (47-83) | 72 (52-86) | 76 (69-86) | .43 |

IQR, interquartile range; N/A, not applicable.

IPSS-R Scores: ≤1.5, very low risk; >1.5-3, low risk; >3-4.5, intermediate risk; >4.5-6, high risk; >6, very high risk.

Testing available in 47/83 (57%) patients.

Clinical features were associated with specific genetic variants. Patients with the Val variant were less likely to develop ear chondritis (Leu n = 8 [53%], Val n = 4 [22%], Thr n = 33 [66%]; P < .01) and were more likely to have an undifferentiated inflammatory syndrome (Leu n = 1 [6%], Val n = 10 [55%], Thr n = 8 [16%]; P < .01) (Figure 1A). Patients with the Thr variant had more inflammatory eye disease (Leu n = 1 [6%], Val n = 1 [5%], Thr n = 18 [36%]; P < .01). Patients with the Leu variant were more commonly diagnosed with Sweet syndrome (Leu n = 9 [60%], Val n = 2 [11%], Thr n = 7 [14%]; P < .01). There were no significant differences by variant status in number of DMARDs used, hematologic manifestations, or development of blood transfusion dependence. A complete list of clinical comparisons is detailed in Table 1.

Survival analysis in VEXAS syndrome. (A) Frequencies of common clinical diagnoses assigned to patients with VEXAS syndrome are shown stratified by genotype. (B) Kaplan-Meier curves demonstrate survival in the entire cohort and (C) are stratified by genotype. (D) Forest plot showing the results of a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model where the Val variant (c.121 A>G, p.Met41Val), transfusion dependence (time-varying predictor), and ear chondritis were significantly associated with mortality in VEXAS syndrome. *, P < .05; #, P < .01 for survival difference between all groups.

Survival analysis in VEXAS syndrome. (A) Frequencies of common clinical diagnoses assigned to patients with VEXAS syndrome are shown stratified by genotype. (B) Kaplan-Meier curves demonstrate survival in the entire cohort and (C) are stratified by genotype. (D) Forest plot showing the results of a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model where the Val variant (c.121 A>G, p.Met41Val), transfusion dependence (time-varying predictor), and ear chondritis were significantly associated with mortality in VEXAS syndrome. *, P < .05; #, P < .01 for survival difference between all groups.

The median length of follow-up from symptom onset to study end date was 4.7 years (range, 1-18). Twenty patients (25%) died of a variety of disease-related complications related to end-stage illness compounded by glucocorticoid toxicities, and 7 patients were transfusion dependent at the time of death. A total of 16 patients were identified retrospectively after death. Across the cohort, the median survival time from symptom onset was 10 years (Figure 1B). Death was more common in patients with the Val variant (50%, n = 9) compared with patients with the Leu (13%, n = 2) or Thr variants (18%, n = 9); P = .02. Median survival of patients with the Val variant was 9 years, which was significantly shorter compared with patients with the Leu or Thr variants (P < .01, Figure 1C). No patient with the Val variant survived longer than 12 years after symptom onset.

On univariate analysis, ear chondritis was associated with increased survival, with a HR of 0.24 (95% CI, 0.09-0.61; P < .01) (Table 2). Decreased survival was observed for patients with the Val variant (HR, 3.49; 95% CI, 1.47-8.32; P < .01) and for patients who became transfusion dependent (HR, 4.56; 95% CI, 1.87-11.08; P < .01). Unlike transfusion dependence, development of MDS was not associated with a statistically significant increased risk of death (HR, 2.44; 95% CI, 0.92-6.50, P = .07). When patients with MDS were categorized into 2 groups based on the IPSS-R score, there was no association between IPSS-R and death (very low risk/low risk vs intermediate/high risk; P = .37). Use of DMARDs was also not associated with survival (HR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.11-1.56; P = .23). VAF of UBA1 mutations were measured in 47 patients (median, 75.5; IQR, 57.3-85.4). There was no association between UBA1 VAF and survival (HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.94-1.03; P = .52) (Table 2).

Cox proportional hazards analysis of clinical factors associated with survival in VEXAS syndrome

| . | Univariable . | Multivariable* . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Hazard ratio (95% CI) . | P value . | Hazard ratio (95% CI) . | P value . |

| Ear chondritis | 0.24 (0.09-0.61) | <.01 | 0.32 (0.12-0.90) | .03 |

| Val variant | 3.49 (1.47-8.32) | <.01 | 2.56 (1.01-6.47) | .05 |

| Transfusion dependence† | 4.56 (1.87-11.08) | .03 | 4.47 (1.79-11.18) | <.01 |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome† | 2.44 (0.92-6.50) | .07 | ||

| Nose chondritis | 0.44 (0.15-1.13) | .10 | ||

| Age at disease onset | 1.00 (0.98-1.11) | .12 | ||

| Unprovoked DVT | 0.49 (0.17-1.25) | .14 | ||

| Lower extremity edema | 0.55 (0.20-1.38) | .22 | ||

| Use of DMARDs | 0.20 (0.11-1.56) | .23 | ||

| Fever | 3.19 (0.65-1.52) | .25 | ||

| Arthritis | 0.70 (0.28-1.70) | .42 | ||

| Testicular pain/swelling | 0.78 (0.28-1.74) | .42 | ||

| Hearing loss | 1.49 (0.44-4.23) | .45 | ||

| UBA1 VAF | 0.98 (0.94-1.03) | .52 | ||

| Pleural effusion | 1.28 (0.44-3.21) | .63 | ||

| Periorbital edema | 3.61 (0.36-2.92) | .82 | ||

| Eye inflammation | 1.32 (0.36-2.91) | .85 | ||

| Skin involvement | 1.05 (0.38-3.72) | .92 | ||

| Pulmonary infiltrates | 0.96 (0.39-2.48) | .94 | ||

| . | Univariable . | Multivariable* . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Hazard ratio (95% CI) . | P value . | Hazard ratio (95% CI) . | P value . |

| Ear chondritis | 0.24 (0.09-0.61) | <.01 | 0.32 (0.12-0.90) | .03 |

| Val variant | 3.49 (1.47-8.32) | <.01 | 2.56 (1.01-6.47) | .05 |

| Transfusion dependence† | 4.56 (1.87-11.08) | .03 | 4.47 (1.79-11.18) | <.01 |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome† | 2.44 (0.92-6.50) | .07 | ||

| Nose chondritis | 0.44 (0.15-1.13) | .10 | ||

| Age at disease onset | 1.00 (0.98-1.11) | .12 | ||

| Unprovoked DVT | 0.49 (0.17-1.25) | .14 | ||

| Lower extremity edema | 0.55 (0.20-1.38) | .22 | ||

| Use of DMARDs | 0.20 (0.11-1.56) | .23 | ||

| Fever | 3.19 (0.65-1.52) | .25 | ||

| Arthritis | 0.70 (0.28-1.70) | .42 | ||

| Testicular pain/swelling | 0.78 (0.28-1.74) | .42 | ||

| Hearing loss | 1.49 (0.44-4.23) | .45 | ||

| UBA1 VAF | 0.98 (0.94-1.03) | .52 | ||

| Pleural effusion | 1.28 (0.44-3.21) | .63 | ||

| Periorbital edema | 3.61 (0.36-2.92) | .82 | ||

| Eye inflammation | 1.32 (0.36-2.91) | .85 | ||

| Skin involvement | 1.05 (0.38-3.72) | .92 | ||

| Pulmonary infiltrates | 0.96 (0.39-2.48) | .94 | ||

Only variables with P < .05 on univariable analyses were carried forward to the multivariable model.

Modeled as time-varying predictor variables.

In multivariate analysis, development of transfusion dependence (HR, 4.47; 95% CI, 1.79-11.18; P < .01) and the Val variant (HR, 2.56; 95% CI, 1.01-6.47; P = .049) were independently associated with increased risk of death. Ear chondritis (HR, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.12-0.90; P = .03) was an independent predictor of prolonged survival (Table 2; Figure 1D). No interaction effects were observed.

Overall, 32% (n = 22) of patients became transfusion dependent. In survival analysis, median time from symptom onset to transfusion dependence was 14 years (supplemental Figure 1). The percentage of patients who became transfusion dependent was similar by variant (Leu n = 4 [26%], Val n = 4 [22%], Thr n = 14 [28%]; P = .89). No genetic or clinical features were significantly associated with time to transfusion dependence (supplemental Table 3).

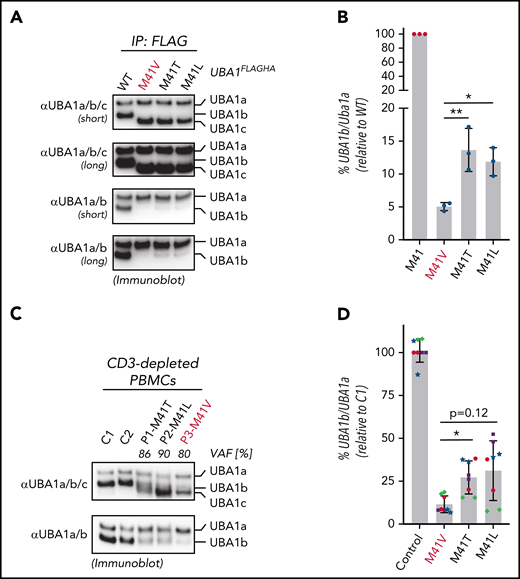

Mutations in UBA1 at p.Met41 lead to a cytoplasmic isoform swap through reduced UBA1b translation (initiated from p.Met41) and production of a catalytically impaired UBA1c (initiated from p.Met67).1 These mutations substitute the canonical start codon AUG to GUG (p.Met41Val), ACG (p.Met41Thr), or CUG (p.Met41Leu). All 3 of these noncanonical start codons support translation initiation with varying efficiencies depending on sequence context and cell type.11 Thus, we hypothesized that the genotype-specific disease mortality and clinical characteristics may correlate with residual translation of UBA1b. To provide first evidence for this hypothesis, we performed immunoblot analysis of immunoprecipitation fractions of UBA1FLAGHA constructs from 293T cells using antibodies recognizing all 3 proteo-isoforms of UBA1 (UBA1a/b/c, Figure 2A). Consistent with our previous reports,1,12 we found that when p.Met41 is altered, UBA1c is expressed. However, due to the close migration of UBA1b and UBA1c, we were not able to detect residual UBA1b fractions in a quantifiable manner. To overcome this limitation in detection, we developed monoclonal antibodies that specifically recognize UBA1a and UBA1b but not UBA1c (αUBA1a/b, supplemental Figure 2). Using these antibodies, we were able to quantify the residual amounts of UBA1b relative to UBA1a for the different VEXAS variants (Figure 2B), which, when compared with WT UBA1, revealed an overall marked decrease in the UBA1b/UBA1a ratio. Importantly, we also detected a significant ∼2-fold lower amount of relative UBA1b levels produced by the p.Met41Val variant compared with the p.Met41Leu or p.Met41Thr variants.

p.Met41Val produces less UBA1b as compared with other patient variants. (A) p.Met41Val supports less UBA1b translation than p.Met41Thr and p.Met41Leu. HEK293T cells were transfected with C-terminally FLAG-tagged WT UBA1 and indicated VEXAS variants, lysed, subjected to anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation and analyzed by anti-UBA1a/b/c or anti-UBA1a/b immunoblotting. Shorter and longer exposures of the respective immunoblots are shown. (B) Quantification of the experiment shown in panel A. Error bars denote standard error of the mean, n = 3 technical replicates, *P < .05; **P < .01, ordinary 1-way ANOVA. (C) p.Met41Val carriers express less UBA1b than p.Met41Thr and p.Met41Leu carriers. CD3-depleted peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of healthy volunteers (C1, C2) and VEXAS patients with similar VAFs were subjected to anti-UBA1a/b/c or anti-UBA1a/b immunoblotting. (D) Quantification of anti-UBA1a/b immunoblots of CD3-depleted PBMCs or CD14+ cells of healthy volunteers (control) or VEXAS patients (p.Met41Val/Thr/Leu). Error bars denote standard deviation, n = 8 (4 biological replicates of independently processed patient samples per genotype with 2 technical replicates each; technical replicates of each biological replicate are depicted in the same color and symbol), *P < .05, ordinary 1-way ANOVA.

p.Met41Val produces less UBA1b as compared with other patient variants. (A) p.Met41Val supports less UBA1b translation than p.Met41Thr and p.Met41Leu. HEK293T cells were transfected with C-terminally FLAG-tagged WT UBA1 and indicated VEXAS variants, lysed, subjected to anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation and analyzed by anti-UBA1a/b/c or anti-UBA1a/b immunoblotting. Shorter and longer exposures of the respective immunoblots are shown. (B) Quantification of the experiment shown in panel A. Error bars denote standard error of the mean, n = 3 technical replicates, *P < .05; **P < .01, ordinary 1-way ANOVA. (C) p.Met41Val carriers express less UBA1b than p.Met41Thr and p.Met41Leu carriers. CD3-depleted peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of healthy volunteers (C1, C2) and VEXAS patients with similar VAFs were subjected to anti-UBA1a/b/c or anti-UBA1a/b immunoblotting. (D) Quantification of anti-UBA1a/b immunoblots of CD3-depleted PBMCs or CD14+ cells of healthy volunteers (control) or VEXAS patients (p.Met41Val/Thr/Leu). Error bars denote standard deviation, n = 8 (4 biological replicates of independently processed patient samples per genotype with 2 technical replicates each; technical replicates of each biological replicate are depicted in the same color and symbol), *P < .05, ordinary 1-way ANOVA.

To confirm this genotype-specific difference in UBA1b levels in patient cells, we subjected CD3-depleted PBMCs from control or VEXAS patients with similar VAFs (80% to 90%) to immunoblotting using our newly developed UBA1a/b-specific antibodies (Figure 2C). Indeed, consistent with our findings in 293T cells, we found that the p.Met41Val patient lysate contained ∼2-fold less UBA1b than p.Met41Thr and p.Met41Leu patient lysates. Quantification of UBA1b levels of CD3-depleted PBMCs or CD14+ patient cells revealed a significant ∼2-fold difference between p.Met41Val and p.Met41Thr, with a similar trend for p.Met41Leu (Figure 2D). To overcome variability in patient cells due to differences in VAFs and cell viability, we next sought to confirm these genotype-specific differences in UBA1b levels by an independent approach. Therefore, we developed a bicistronic UBA1b reporter system that supports (1) CAP-dependent translation of UBA1HA (in which p.Met41 is varied and UBA1a and UBA1c initiation suppressed through p.Met1/67Ala substitutions) and (2) IRES-dependent translation of MBPHA (Figure 3A). Employing this reporter system in HEK293T cells, we observed an expected marked decrease in UBA1b translation for all VEXAS mutations when compared with the canonical UBA1b start codon (Figure 3B). However, all VEXAS variants supported significantly higher UBA1b translation than p.Met41Ala, a codon not known to mediate translation initiation (Figure 3C). Consistent with our observations in patients cells, we also observed a significant ∼2-fold increase in relative UBA1b levels when comparing p.Met41Thr and p.Met41Leu to p.Met41Val, the VEXAS variant associated with increased mortality.

Residual UBA1b translation defines a threshold for VEXAS syndrome pathogenesis. (A) Schematic overview of the translation reporter system used to determine UBA1b translation. The first cistron of these reporters is translated in a CAP-dependent mechanism and encodes for C-terminally HA-tagged UBA1 constructs varied in p.Met41 and mutated at p.Met1 and p.Met67 (to suppress UBA1a and UBA1c translation and thus allowing for sensitive quantification of UBA1b by anti-HA immunoblotting). The second cistron is translated using an IRES and encodes for a C-terminally HA-tagged MBP, which is used for normalization across different p.Met41 variants. (B) p.Met41Val supports less UBA1b translation than p.Met41Thr and p.Met41Leu. Anti-HA immunoblot analysis of HEK293T lysates expressing indicated UBA1b translation reporters. (C) Quantification of the experiment shown in panel B. Error bars denote SD, n = 12 (4 biological with 3 technical replicates each; technical replicates of each biological replicate are depicted in the same color and symbol), **P < .01; ****P < .0001, ordinary 1-way ANOVA. (D) The canonical VEXAS variants (p.Met41Val/Thr/Leu) support more UBA1b translation than any of the other possible single-nucleotide variants at the Met41 start codon. Anti-HA immunoblot analysis of HEK293T lysates expressing indicated UBA1b translation reporters. (E) Quantification of the experiment shown in panel D. Error bars denote SD, n = 4 (2 biological with 2 technical replicates each; technical replicates of each biological replicate are depicted in the same color and symbol), *P < .05; ****P < .0001, ordinary 1-way ANOVA. (F) Two novel VEXAS variants (c.121 A>T; p.Met41Leu and c.119 G>C; p.Gly40Ala) are present in a patient in cis on the same allele. Overview of the genome sequencing reads of the p.Met41LeuTTG/p.Gly40Ala patient. (G) The p.Gly40Ala variant rescues residual UBA1b translation of the p.Met41LeuTTG to the level of the canonical VEXAS variant p.Met41Val. Anti-HA immunoblot analysis of HEK293T lysates expressing indicated UBA1b translation reporters. (H) Quantification of the experiment shown in panel G. Error bars denote SD, n = 10 (2 biological with 5 technical replicates each; technical replicates of each biological replicate are depicted in the same color and symbol), **P < .01; ****P < .0001, ordinary 1-way ANOVA. Shaded area represents minimum threshold below p.Met41Val expression. SD, standard deviation.

Residual UBA1b translation defines a threshold for VEXAS syndrome pathogenesis. (A) Schematic overview of the translation reporter system used to determine UBA1b translation. The first cistron of these reporters is translated in a CAP-dependent mechanism and encodes for C-terminally HA-tagged UBA1 constructs varied in p.Met41 and mutated at p.Met1 and p.Met67 (to suppress UBA1a and UBA1c translation and thus allowing for sensitive quantification of UBA1b by anti-HA immunoblotting). The second cistron is translated using an IRES and encodes for a C-terminally HA-tagged MBP, which is used for normalization across different p.Met41 variants. (B) p.Met41Val supports less UBA1b translation than p.Met41Thr and p.Met41Leu. Anti-HA immunoblot analysis of HEK293T lysates expressing indicated UBA1b translation reporters. (C) Quantification of the experiment shown in panel B. Error bars denote SD, n = 12 (4 biological with 3 technical replicates each; technical replicates of each biological replicate are depicted in the same color and symbol), **P < .01; ****P < .0001, ordinary 1-way ANOVA. (D) The canonical VEXAS variants (p.Met41Val/Thr/Leu) support more UBA1b translation than any of the other possible single-nucleotide variants at the Met41 start codon. Anti-HA immunoblot analysis of HEK293T lysates expressing indicated UBA1b translation reporters. (E) Quantification of the experiment shown in panel D. Error bars denote SD, n = 4 (2 biological with 2 technical replicates each; technical replicates of each biological replicate are depicted in the same color and symbol), *P < .05; ****P < .0001, ordinary 1-way ANOVA. (F) Two novel VEXAS variants (c.121 A>T; p.Met41Leu and c.119 G>C; p.Gly40Ala) are present in a patient in cis on the same allele. Overview of the genome sequencing reads of the p.Met41LeuTTG/p.Gly40Ala patient. (G) The p.Gly40Ala variant rescues residual UBA1b translation of the p.Met41LeuTTG to the level of the canonical VEXAS variant p.Met41Val. Anti-HA immunoblot analysis of HEK293T lysates expressing indicated UBA1b translation reporters. (H) Quantification of the experiment shown in panel G. Error bars denote SD, n = 10 (2 biological with 5 technical replicates each; technical replicates of each biological replicate are depicted in the same color and symbol), **P < .01; ****P < .0001, ordinary 1-way ANOVA. Shaded area represents minimum threshold below p.Met41Val expression. SD, standard deviation.

Of the 9 possible single-nucleotide variants within the Met41 start codon, only 3 have been identified in VEXAS syndrome to date. This suggests that the 3 canonical VEXAS mutations might have unique features in acting as near-cognate start codons for UBA1b translation. To investigate this further, we assessed the ability of all possible nucleotide variants within the Met41 start codon to support UBA1b translation within our reporter system (Figure 3D). Strikingly, we found that only p.Met41Thr/Val/Leu generated significantly higher levels of UBA1b than did p.Met41Ala, whereas this was not the case for any of the other variants (Figure 3E). Previously reported splice mutations also do not produce UBA1b above background levels (supplemental Figure 3). However, these variants produce a small percentage of WT-spliced transcript,3 therefore likely underestimating the residual amount of UBA1b present in patient cells.

The above results suggested that a minimum threshold of residual UBA1b level is required to cause disease. Supporting this notion, a patient with clinical features consistent with VEXAS syndrome was recently identified who had 2 novel mutations present in exon 3 of UBA1 (c.121 A>T; p.Met41Leu and c.119 G>C; p.Gly40Ala) in cis on the same allele (Figure 3F). We found that this novel Leu mutation by itself produces less UBA1b than the canonical Leu variant causing VEXAS (c.121 A>C; p.Met41Leu) (TTG vs M41L in Figure 3D-E). However, residual UBA1b translation of the p.Met41LeuTTG variant was significantly increased by the cooccurring p.Gly40Ala mutation to levels similar to those of the VEXAS-causing p.Met41Val variant (Figure 3G-H). The novel genotype of this patient suggests that these 2 mutations coevolved to cause disease by concurrently modulating levels of UBA1b production above a disease-specific threshold.

Discussion

Here, we report clinical characteristics of a cohort of 83 patients with VEXAS, all caused by somatic mutations at UBA1 p.Met41. Our study identified 3 factors that independently predict survival in this severe disease: presence of ear chondritis, development of transfusion-dependent anemia, and genotype. We establish p.Met41Val as a negative prognostic biomarker and provide an underlying molecular explanation for this finding: p.Met41Val supports less non-AUG translation of UBA1b than the other variants, indicating that VEXAS syndrome severity inversely correlates with residual UBA1b protein. In addition, our mechanistic studies suggest that a certain minimum threshold of cellular UBA1b levels is required to initiate disease progression. Our work thus provides a framework for genotype-driven risk stratification along with potential novel avenues for treatment consideration.

The overall clinical phenotype and the treatment-refractory nature of the disease reported in this study remains consistent with the initial 25 patients described with VEXAS syndrome.1 Furthermore, results from this study confirm and extend upon recent findings from an independent cohort of 116 patients with VEXAS from France.2 In both the French study and the current study, there was a high prevalence of skin involvement, fever, pulmonary involvement, and chondritis among patients with VEXAS. A similar frequency of VEXAS-defining mutations was reported within codon 41 in each study. Both studies found that patients with p.Met41Val were less likely to develop chondritis and more likely to have fever. Similarly, the highest prevalence of ocular involvement was observed in patients with p.Met41Thr. In addition, we report a novel association between Sweet syndrome and p.Met41Leu, which was not assessed in the French study.

Both the present work and the French study examined potential relationships between genotype and survival in VEXAS. In this study, we identified that p.Met41Val was a negative predictor of survival. In the French study, the p.Met41Leu variant was associated with improved survival. Although different, these findings are not discordant and are likely related to differences in follow-up time between the studies. In the French cohort, patients were followed for 5 years from symptom onset, during which time no patients with the p.Met41Leu variant died. In contrast, the follow-up period in this study was longer, with many patients studied for >10 years after symptom onset. Survival curves in this study and the study from France are identical up to 5 years from symptom onset; however, the genotype-specific differences reported in this study emerge in years 5 to 10 from symptom onset. During that interval, death occurred in several patients with the p.Met41Leu variant; therefore, this variant was not associated with improved overall survival in our cohort. In contrast, we found the p.Met41Val variant was a biomarker of decreased survival as many patients with the p.Met41Val variant died in years 5 to 10 from symptom onset, and no patient survived longer than 12 years. Therefore, our study validates the findings about early survival reported in the French cohort and extends those findings to examine a critical time period later in the disease course.

MDS is common in patients with VEXAS syndrome, with prevalence ranging from 25% to 63% in different cohorts.1,3,4 Although we observed an association with development of MDS and decreased survival, this association was not statistically significant, likely due to the relatively modest sample size of the cohort in the presence of competing risks for death in these patients. The IPSS-R score was also not significantly associated with survival as most patients with VEXAS have lower-risk MDS with low IPSS-R scores and few myeloid malignancy–associated genetic abnormalities, and no patient evolved to acute myeloid leukemia.13 The hematologic features of patients with clonal acquired UBA1 mutations are more similar to clonal cytopenia of uncertain significance (CCUS), given that the vast majority have anemia and/or thrombocytopenia.14,15 However, the UBA1 gene is not currently designated a myeloid malignancy–associated genetic mutation, and patients with VEXAS have severe disease with inflammation potentially contributing to anemia and thrombocytopenia, making CCUS an inaccurate classification.16 We propose that VEXAS and UBA1 mutations are a unique subgroup of highly inflammatory clonal cytopenia, which will require prospective comprehensive studies going forward. A similar paradigm of specific mutations altering survival and prognosis, independent of IPSS score and known risk factors, is well established in CCUS and MDS.14,15,17-19

Genotype-phenotype approaches are powerful means to understand different diseases, both at the clinical and the molecular level. Examples of such relationships are seen in Marfan syndrome,20 deficiency of ADA2,21 and Fabry disease.22 In these cases, disease severity can be predicted based on the impact of the mutation on protein function (ie, nonsense, missense, and synonymous mutations). However, to our knowledge, this work is the first example in which varying mutations at the same amino acid lead to a spectrum of disease by differentially affecting protein translation rather than UBA1 VAF levels. In addition, clinical analysis combined with our in vitro translation assays and patient cell analysis provide strong evidence for the dose-dependent nature of disease severity. In contrast, UBA1 VAF levels were not associated with survival, as clonal burden of mutation is exceedingly high in almost every patient with VEXAS syndrome.

The delineation of an inverse correlation between UBA1b levels and disease severity has important implications for the molecular mechanisms underlying VEXAS syndrome. Together with our previous findings that VEXAS syndrome can be caused by p.Ser56Phe, a UBA1 variant that does not result in translation of UBA1c,12 our results suggest that the major cause of disease is loss of UBA1b or its activity rather than gain of UBA1c. In addition, the pathogenic mutations convert p.Met41 to those subcognate start codons that are most frequently used for translation initiation in mammalian cells23,24 and support more UBA1b translation than any of the 6 other possible single-nucleotide mutations that would lead to a missense variant at this position (Figure 3D-E). This raises the possibility that a certain residual amount of UBA1b translation might be required to cause disease and, if too low, would not promote clonal expansion. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that none of the other possible p.Met41 missense mutations have been found in isolation in patients with VEXAS and are also absent in healthy controls in gnomAD.25 In addition, we find that deleterious mutations such as c.121A>T; p.Met41Leu are only present in combination with variants that increase translation (Figure 3E-F). Further work is needed to understand how decreased levels of UBA1b lead to inflammatory disease and to delineate whether cell-specific thresholds of UBA1b activity promote clonal expansion vs cell death. Finally, the inverse correlation between UBA1b levels and disease severity also identifies potential new treatment strategies for the VEXAS syndrome: reactivation of UBA1c by small molecule activators or an increase of UBA1b pools by promoting non-AUG translation from p.Met41 mutations.

A few study limitations should be considered. This study was conducted within an observational, retrospective cohort, raising potential for confounding differences in patient-specific clinical management. Although the study was not designed to evaluate the effect of specific treatments on mortality risk, use of steroid-sparing treatments in general was not associated with survival, reflecting the fact that few effective therapies beyond glucocorticoids have been identified for this disease.26-30 Information about cumulative glucocorticoid exposure was not available. Patients with disease-defining mutations outside of p.Met41 were excluded from analysis due to insufficient numbers. Because VEXAS syndrome is a newly discovered disease, the spectrum of disease-associated clinical and genetic features may change over time. Prognostic findings from this study should be validated in additional cohorts. Finally, to directly define the role of UBA1b residual protein levels in determining disease severity, we will need model systems that allow fine tuning of UBA1b expression to assess inflammation.

VEXAS syndrome connects a set of patients with seemingly unrelated clinical diagnoses. In addition to the diagnostic value of molecular genetics, this study establishes a prognostic role for molecular genotyping as a biomarker of disease severity in VEXAS syndrome. Specific amino acid substitutions at codon 41 affect residual translation of UBA1b in association with clinical phenotype and disease severity. These observations may lead to the development of much-needed targeted therapeutics for what is a life-threatening condition. A set of both clinical and genetic risk factors are independently associated with survival. These findings may inform clinical risk assessment and guide management decisions, including selection of appropriate patients with VEXAS syndrome for bone marrow transplantation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and their families for participating in clinical research. They thank Ivona Aksentijevich for helpful comments on this manuscript.

This work was supported by the intramural programs of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institutes of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), and the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR). D.B.B. is supported by the Relapsing Polychondritis Foundation and funding from the NIH/NIAMS (R00AR078205). C.J.A.D. is a Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Career Development Fellow (211153/Z/18/Z). This paper presents some independent research supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Leeds Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). J.J.P. is supported by K23AR073927. The Visual abstract created with BioRender.

Authorship

Contribution: M.A.F., S.S., A.W., P.C.G., and D.B.B. designed the study; M.A.F., S.S., D.O.C., J.C.C., H.A., F.G.-R., D.B.U.K., L.W., W.G., J.S.T., J.J.P., J.A.P., T.A.K., M.J.K., K.J.W., C.C., R.S.T., C.J.A.D., A.C., P.H., E.M.P., H.B., K.K., E.W.C., K.R.C., B.A.P., A.K.O., A.W., P.C.G., and D.B.B. gathered data; and M.A.F., D.O.C., J.C.C., H.A., D.L.K., N.S.Y., A.W., P.C.G., and D.B.B. analyzed data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: David B. Beck, 435 East 30th Street, Office 805, NYU Langone, New York, NY 10016; e-mail: david.beck@nyulangone.org; Peter C. Grayson, 10 Center Drive, Building 10 12N248B, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: peter.grayson@nih.gov; and Achim Werner, Building 30 Room 326, 30 Convent Drive, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: achim.werner@nih.gov.

Send data sharing requests via e-mail to the corresponding author.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

REFERENCES

Author notes

A.W., P.C.G., and D.B.B. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal