Abstract

Anemia of inflammation (AI), also known as anemia of chronic disease (ACD), is regarded as the most frequent anemia in hospitalized and chronically ill patients. It is prevalent in patients with diseases that cause prolonged immune activation, including infection, autoimmune diseases, and cancer. More recently, the list has grown to include chronic kidney disease, congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary diseases, and obesity. Inflammation-inducible cytokines and the master regulator of iron homeostasis, hepcidin, block intestinal iron absorption and cause iron retention in reticuloendothelial cells, resulting in iron-restricted erythropoiesis. In addition, shortened erythrocyte half-life, suppressed erythropoietin response to anemia, and inhibition of erythroid cell differentiation by inflammatory mediators further contribute to AI in a disease-specific pattern. Although the diagnosis of AI is a diagnosis of exclusion and is supported by characteristic alterations in iron homeostasis, hypoferremia, and hyperferritinemia, the diagnosis of AI patients with coexisting iron deficiency is more difficult. In addition to treatment of the disease underlying AI, the combination of iron therapy and erythropoiesis-stimulating agents can improve anemia in many patients. In the future, emerging therapeutics that antagonize hepcidin function and redistribute endogenous iron for erythropoiesis may offer additional options. However, based on experience with anemia treatment in chronic kidney disease, critical illness, and cancer, finding the appropriate indications for the specific treatment of AI will require improved understanding and a balanced consideration of the contribution of anemia to each patient’s morbidity and the impact of anemia treatment on the patient’s prognosis in a variety of disease settings.

Introduction

Anemia of inflammation (AI), better known as anemia of chronic disease (ACD), is considered the second most prevalent anemia worldwide (after iron deficiency anemia [IDA]) and the most frequent anemic entity observed in hospitalized or chronically ill patients.1,2 Estimates suggest that up to 40% of all anemias worldwide can be considered AI or combined anemias with important AI contributions, which, in total, account for >1 billion affected individuals.2,3 These high numbers reflect that the spectrum of diseases in which inflammation has been recognized as contributing to anemia has expanded over the past years. Originally, AI was linked to chronic infections and autoimmune diseases in which inflammation was easily detectable and sustained1,4,5 (Table 1). Some cancers that presented with a strong inflammatory component were recognized to have a similar pathophysiology, although this was often complicated by other cancer-specific and iatrogenic mechanisms.4 Accumulating data suggest that AI, sometimes with coexisting iron deficiency, is much more prevalent and also affects patients with chronic kidney disease, especially those undergoing dialysis, and patients with congestive heart failure in whom iron deficiency impairs cardiovascular performance.6,7 Other less well-studied examples include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary arterial hypertension, obesity, chronic liver disease, and advanced atherosclerosis with its sequelae of coronary artery disease and stroke8-10 (Table 1). Despite the high prevalence of AI and its documented associations with the progression of underlying diseases, it remains unclear to what extent AI is merely a marker of disease severity and progression as opposed to a causative factor with a specific impact on the underlying diseases and long-term patient outcomes. Increased understanding of the specific contribution of AI to long-term patient outcomes may only come with human trials of narrowly targeted therapeutic interventions against AI.

Disease groups in which AI is common

| Disease group . |

|---|

| Cancer and hematological malignancies |

| Infections |

| Immune-mediated diseases |

| Inflammatory diseases |

| Chronic kidney disease |

| Congestive heart failure |

| Chronic pulmonary disease |

| Obesity |

| Anemia of the elderly |

| Anemia of critical illness (accelerated course) |

| Disease group . |

|---|

| Cancer and hematological malignancies |

| Infections |

| Immune-mediated diseases |

| Inflammatory diseases |

| Chronic kidney disease |

| Congestive heart failure |

| Chronic pulmonary disease |

| Obesity |

| Anemia of the elderly |

| Anemia of critical illness (accelerated course) |

Pathophysiology of AI

AI is caused by 3 major pathophysiological pathways that act through mediators of an activated immune system (Figure 1).

Pathophysiological mechanisms of AI. Systemic inflammation results in immune cell activation and formation of numerous cytokines. Interleukin (IL-6) and IL-1β, as well as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), are potent inducers of the master regulator of iron homeostasis, hepcidin, in the liver, whereas expression of the iron-transport protein transferrin is reduced. Hepcidin causes iron retention in macrophages by degrading the only known cellular iron exporter ferroportin (FP1); by the same mechanism, it blocks dietary iron absorption in the duodenum. Multiple cytokines (eg, interleukin-1β [IL-1β], IL-6, IL-10, and interferon-γ [IFN-γ]) promote iron uptake into macrophages, increase radical-mediated damage to erythrocytes and their ingestion by macrophages, and cause efficient iron storage by stimulating ferritin production and blocking iron export by transcriptional inhibition of FP1 expression. This results in the typical changes of AI (ie, hypoferremia and hyperferritinemia). In addition, IL-1 and TNF inhibit the formation of the red cell hormone erythropoietin (Epo) by kidney epithelial cells. Epo stimulates erythroid progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation, but the expression of its erythroid receptor (EpoR) and EpoR-mediated signaling are inhibited by several cytokines. Moreover, cytokines can directly damage erythroid progenitors or inhibit heme biosynthesis via radical formation or induction of apoptotic processes. Importantly, because of iron restriction in macrophages, the availability of this metal for erythroid progenitors is reduced. Erythroid progenitors acquire iron mainly via transferrin-iron/transferrin receptor (Tf/TfR)-mediated endocytosis. Erythroid iron deficiency limits heme and hemoglobin (Hb) biosynthesis, as well as reduces EpoR expression and signaling via blunted expression of Scribble (Scb). In addition, the reduced Epo/EpoR signaling activity impairs the induction of erythroferrone (Erfe), which normally inhibits hepcidin production.

Pathophysiological mechanisms of AI. Systemic inflammation results in immune cell activation and formation of numerous cytokines. Interleukin (IL-6) and IL-1β, as well as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), are potent inducers of the master regulator of iron homeostasis, hepcidin, in the liver, whereas expression of the iron-transport protein transferrin is reduced. Hepcidin causes iron retention in macrophages by degrading the only known cellular iron exporter ferroportin (FP1); by the same mechanism, it blocks dietary iron absorption in the duodenum. Multiple cytokines (eg, interleukin-1β [IL-1β], IL-6, IL-10, and interferon-γ [IFN-γ]) promote iron uptake into macrophages, increase radical-mediated damage to erythrocytes and their ingestion by macrophages, and cause efficient iron storage by stimulating ferritin production and blocking iron export by transcriptional inhibition of FP1 expression. This results in the typical changes of AI (ie, hypoferremia and hyperferritinemia). In addition, IL-1 and TNF inhibit the formation of the red cell hormone erythropoietin (Epo) by kidney epithelial cells. Epo stimulates erythroid progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation, but the expression of its erythroid receptor (EpoR) and EpoR-mediated signaling are inhibited by several cytokines. Moreover, cytokines can directly damage erythroid progenitors or inhibit heme biosynthesis via radical formation or induction of apoptotic processes. Importantly, because of iron restriction in macrophages, the availability of this metal for erythroid progenitors is reduced. Erythroid progenitors acquire iron mainly via transferrin-iron/transferrin receptor (Tf/TfR)-mediated endocytosis. Erythroid iron deficiency limits heme and hemoglobin (Hb) biosynthesis, as well as reduces EpoR expression and signaling via blunted expression of Scribble (Scb). In addition, the reduced Epo/EpoR signaling activity impairs the induction of erythroferrone (Erfe), which normally inhibits hepcidin production.

Although not specifically documented, it can be expected that the contribution of each of these pathways depends on the underlying causes and patterns of inflammation, as well as the genetic makeup and premorbid condition of the patient, including preexisting iron stores, erythropoietic capacity of the marrow and the responsiveness of renal erythropoietin (Epo) production to anemia and hypoxia, and the resistance of erythrocytes to mechanical and antibody-complement induced injury.

Iron restriction

First, systemic immune activation leads to profound changes of iron trafficking, resulting in iron retention in macrophages and in reduced dietary iron absorption. Iron sequestration in macrophages is by far more important, because recycling of iron from senescent erythrocytes by macrophages accounts for >90% of the daily iron requirements for hemoglobin (Hb) synthesis and erythropoiesis.11 In response to microbial molecules, autoantigens, or tumor antigens, multiple inflammatory cytokines are released by cells of the immune system and alter systemic iron metabolism. Although it is not possible to completely disentangle the iron-regulatory contributions of the multiply cross-regulating cytokine networks, interleukin-6 (IL-6) appears to be the most important, at least in animal models.12 In laboratory animals and in humans, IL-6 stimulates hepatocytes to produce hepcidin, the master regulator of iron homeostasis, predominantly through STAT3.11 Other cytokines, including IL-1 and activin B, can also stimulate hepcidin production, but their specific pathological role is less well established.13 As reviewed elsewhere, the synthesis of systemically acting hepcidin by hepatocytes is also positively regulated by transferrin saturation and iron stores and negatively regulated by erythroid activity in the marrow.11,14

Hepcidin exerts its iron-regulatory effects by binding to the only known transmembrane iron exporter, ferroportin, causing cellular ferroportin internalization and degradation.15 Thus, increased hepcidin concentrations inhibit iron absorption in the duodenum where ferroportin is needed to deliver absorbed dietary iron to the circulation, and they also act on macrophages to block the release of iron recycled from senescent erythrocytes into the plasma.16 Recent evidence indicates that, at higher concentrations, hepcidin may directly block iron export by occluding ferroportin,17 a mechanism that may be especially important in limiting iron release from cells that lack endocytic machinery (erythrocytes) or in conditions under which endocytosis is slow.

In animal models of AI and in patients suffering from inflammatory diseases, increased hepcidin levels are associated with low ferroportin expression on duodenal enterocytes and macrophages, along with impaired dietary iron absorption and retention of iron in macrophages,18,19 thereby causing decreased iron delivery for erythropoiesis.

In addition, various cytokines directly impact on duodenal or macrophage iron homeostasis. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) reduces duodenal iron absorption by a poorly characterized, but hepcidin-independent, mechanism.20 The cytokines IL-1, IL-6, IL-10, or TNF-α promote iron acquisition into macrophages via transferrin receptor–mediated endocytosis, via divalent metal transporter 1, or possibly also via increased iron acquisition by lactoferrin and lipocalin-2.21 However, the major source for iron for macrophages is senescent erythrocytes. Cytokines, inflammation-derived radicals, and complement factors damage erythrocytes and promote erythrophagocytosis via stimulation of receptors recognizing senescent red blood cells, such as T-cell immunoglobulin domain 4 or possibly CD44.22,23 Recent evidence suggests that, during periods of increased erythrocyte destruction, erythrophagocytosis and iron recycling are primarily carried out by hepatic macrophages differentiating in the liver from circulating monocytes, rather than by resident splenic macrophages.24 Once iron is acquired by macrophages, it is mainly stored within ferritin, the major iron storage protein whose expression is massively induced by macrophage iron, heme, and cytokines.5,25 Although circulating and, to a lesser extent, macrophage-derived hepcidin are the main regulators of iron export by these cells,15,16,18,19,26,27 bacterial lipopolysaccharides and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) block the transcription of ferroportin, thereby reducing cellular iron export.28,29 All of these events lead to iron-restricted erythropoiesis and the characteristic changes in systemic iron homeostasis observed in AI: hypoferremia and hyperferritinemia. These effects are partially counteracted by the stimulation of synthesis of ferroportin in macrophages by retained iron and heme,30 perhaps explaining why AI rarely reaches the severity seen in pure iron-deficiency anemia.

The specific mechanisms by which iron restriction decreases erythropoiesis have not been fully clarified, but they involve active iron-regulated erythroid-specific mechanisms that decrease the synthesis of heme and Hb, as well as inhibit erythropoiesis, thereby protecting nonerythroid tissues from iron deficiency.31-33 Heme concentration in erythrocyte precursors functions as a secondary iron-dependent regulator of Hb synthesis and erythropoiesis.

Inflammatory suppression of erythropoietic activity

The second pathogenic factor in AI is iron- and hepcidin-independent impairment of erythropoiesis. It is caused, in part, by reduced production and/or reduced biological activity of the hormone Epo in the inflammatory setting.34 Observational studies have indicated lower Epo levels than expected for the degree of anemia in most AI subjects.1 These observations may be due, in part, to the inhibitory effects of cytokines, such as IL-1 and TNF, on hypoxia-mediated stimulation of Epo by interfering with mediated GATA-2 or HNF4 transcription or by causing radical-mediated damage of Epo-producing kidney epithelial cells.35,36 Epo exerts its biological effects after binding to its homodimeric erythroid receptor via JAK/STAT-mediated signaling cascades.36 Although, the number of Epo receptors (EpoRs) did not appear to be altered in subjects with inflammatory anemia, the efficacy of Epo-mediated signaling is reduced and inversely linked to the circulating levels of IL-1 and IL-6,37 indicating the inflammation-driven hyporesponsiveness of EpoRs. However, recent evidence suggests that erythroid iron deficiency, because it also occurs in AI, results in downregulation of EpoR, which could be traced back to iron-mediated regulation of the EpoR control element Scribble.31 Specifically, iron deficiency impairs transferrin receptor-2–mediated iron sensing in erythroid cells,38 resulting in downregulation of Scribble and reduced EpoR expression.

Acting to promote increased iron supply during intensified erythropoiesis, Epo and hypoxia inhibit hepcidin formation via induction of hypoxia inducible factor 1, erythroferrone, matriptase-2, growth differentiation factor-15, or platelet derived growth factor-BB.14,39-42 Thus, the reduced availability and activity of Epo in AI negatively impact the induction of at least some of these hepcidin blockers, such as erythroferrone, thereby aggravating hepcidin-mediated erythroid iron limitation43 and impairing, via a vicious cycle, Epo signaling via Scribble (Figure 1).

Erythroid cell proliferation and differentiation are impaired by the blunted Epo effect and by iron limitation via hepcidin and cytokines. In addition, various inflammatory mediators directly target erythroid cells and induce apoptosis via ceramide- or radical-mediated pathways.1 IFN-γ appears to be central for this process,44 but this cytokine also downregulates EpoR expression on erythroid progenitors,45 inhibits their differentiation via stimulation of PU.1 expression, and reduces erythrocyte lifespan, even as it promotes leukocyte production, differentiation, and activation that are important for host defense.46

In addition, the severity and appearance of AI can be further modified by different factors (Table 2). Specifically, concomitant bleeding episodes, as well as dietary-, genetic-, hormonal-, age-, treatment-, or disease-specific factors and mechanisms, can impact iron metabolism and erythropoiesis in the setting of AI.

Modifiers of severity of AI

| Entity . | Specific factors . | Mechanism . |

|---|---|---|

| Bleeding | Menstruation, gastrointestinal blood loss, repeated blood draws for diagnostics | Development of true iron deficiency |

| Vitamin deficiencies | Cobalamin | Impaired erythropoiesis, hemolysis |

| Folic acid | Impaired erythropoiesis, hemolysis | |

| Vitamin D | Increased hepcidin formation and iron retention | |

| Hemolysis | In autoimmune diseases | Immunoglobulin or complement mediated |

| In infectious diseases | Plasmodium- or Babesia-mediated hemolysis; stimulation of erythrophagocytosis; hemolysis in association with viral infections (eg, EBV, CMV) | |

| In malignancies | Immunoglobulin or complement mediated | |

| Renal dysfunction | Reduced hepcidin excretion | Iron retention and impaired dietary absorption |

| Reduced Epo formation | Impaired erythroid maturation | |

| Uremic toxins | Impaired erythroid progenitor differentiation | |

| Infection | Helicobacter pylori infection | Reduced dietary iron absorption |

| Parvovirus B19, CMV, EBV, HIV, HCV | Pancytopenia, impaired red cell proliferation, hemolysis | |

| Leishmania, Plasmodium | Bone marrow infiltration | |

| Medication | Cytotoxic chemotherapy (including rheumatologic and nephrologic indications) | Impaired erythroid progenitor proliferation and apoptosis |

| Nonsteroidal antirheumatic drugs | Subclinical bleeding | |

| ACE blockers, proton pump inhibitors, neuroleptics | Impaired erythroid progenitor proliferation | |

| Antiplatelet therapy | Subclinical bleeding | |

| Heparins | Hepcidin reduction, subclinical bleeding | |

| Radiotherapy | Erythroid progenitor damage | |

| Hormones | Estrogens/testosterone | Hepcidin regulation |

| Thyroid hormones | Reduced erythroid progenitor proliferation | |

| Genetic polymorphisms | Transferrin, TMPRSS6, divalent metal transporter 1 | Impaired iron absorption |

| Hepcidin | Amelioration or reduction of iron transfer from enterocytes and macrophages | |

| Dietary habits | Low heme iron content | Reduced bioavailability and absorption of dietary iron |

| Obesity | Increased hepcidin levels | Cellular and dietary iron retention |

| Hematological malignancies | Myelodysplasia, smoldering lymphoma | Dyserythropoiesis, bone marrow inflammation and inflammation |

| Age-related factors | Chronic inflammatory status based on chronic diseases, renal impairment, vitamin deficiencies, subclinical myelodysplasia | Dyserythropoiesis, hepcidin-mediated iron retention, reduced Epo activity |

| Entity . | Specific factors . | Mechanism . |

|---|---|---|

| Bleeding | Menstruation, gastrointestinal blood loss, repeated blood draws for diagnostics | Development of true iron deficiency |

| Vitamin deficiencies | Cobalamin | Impaired erythropoiesis, hemolysis |

| Folic acid | Impaired erythropoiesis, hemolysis | |

| Vitamin D | Increased hepcidin formation and iron retention | |

| Hemolysis | In autoimmune diseases | Immunoglobulin or complement mediated |

| In infectious diseases | Plasmodium- or Babesia-mediated hemolysis; stimulation of erythrophagocytosis; hemolysis in association with viral infections (eg, EBV, CMV) | |

| In malignancies | Immunoglobulin or complement mediated | |

| Renal dysfunction | Reduced hepcidin excretion | Iron retention and impaired dietary absorption |

| Reduced Epo formation | Impaired erythroid maturation | |

| Uremic toxins | Impaired erythroid progenitor differentiation | |

| Infection | Helicobacter pylori infection | Reduced dietary iron absorption |

| Parvovirus B19, CMV, EBV, HIV, HCV | Pancytopenia, impaired red cell proliferation, hemolysis | |

| Leishmania, Plasmodium | Bone marrow infiltration | |

| Medication | Cytotoxic chemotherapy (including rheumatologic and nephrologic indications) | Impaired erythroid progenitor proliferation and apoptosis |

| Nonsteroidal antirheumatic drugs | Subclinical bleeding | |

| ACE blockers, proton pump inhibitors, neuroleptics | Impaired erythroid progenitor proliferation | |

| Antiplatelet therapy | Subclinical bleeding | |

| Heparins | Hepcidin reduction, subclinical bleeding | |

| Radiotherapy | Erythroid progenitor damage | |

| Hormones | Estrogens/testosterone | Hepcidin regulation |

| Thyroid hormones | Reduced erythroid progenitor proliferation | |

| Genetic polymorphisms | Transferrin, TMPRSS6, divalent metal transporter 1 | Impaired iron absorption |

| Hepcidin | Amelioration or reduction of iron transfer from enterocytes and macrophages | |

| Dietary habits | Low heme iron content | Reduced bioavailability and absorption of dietary iron |

| Obesity | Increased hepcidin levels | Cellular and dietary iron retention |

| Hematological malignancies | Myelodysplasia, smoldering lymphoma | Dyserythropoiesis, bone marrow inflammation and inflammation |

| Age-related factors | Chronic inflammatory status based on chronic diseases, renal impairment, vitamin deficiencies, subclinical myelodysplasia | Dyserythropoiesis, hepcidin-mediated iron retention, reduced Epo activity |

ACE, angiotensin convertin enzyme; CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Finally, in an acute clinical setting, anemia is detected after hours or a few days in patients with severe infection, which cannot be solely explained by inflammation-driven iron retention or inhibition of erythropoiesis, which may require more time to result in a clinically evident reduction in Hb.

Decreased erythrocyte survival

A shortened erythrocyte lifespan has been extensively documented in the inflammatory setting and has been attributed to enhanced erythrophagocytosis by hepatic and splenic macrophages caused by “bystander” deposition of antibody and complement on erythrocytes, mechanical damage from fibrin deposition in microvasculature, and activation of macrophages for increased erythrophagocytosis.23,46,47 Shortened erythrocyte survival is usually a minor factor in chronic AI; however, in acute infections, severe sepsis, or other critical illnesses accompanied by a high level of cytokine activation, anemia is detected after hours or a few days (ie, too rapidly to be accounted for by deficient erythropoiesis). It is reasonable that massive erythrophagocytosis, hemolysis, or pooling of erythrocytes, along with hemodilution, contribute to this entity that awaits systematic scientific analysis.48 Moreover, remediable iatrogenic factors are common in critical illness and include blood loss from phlebotomy and gastrointestinal blood loss caused by nasogastric tubes, anticoagulation, and the use of medications that promote gastroduodenal erosion or ulceration.

Diagnosis

Although not studied in a comparative fashion, symptoms and signs of IDA and AI are similar and include fatigue, weakness, reduced cardiovascular performance and exercise tolerance, and impaired learning and memory capacity.49,50 Of note, it is uncertain to what extent symptoms of anemia are caused by hypoxia and reduced tissue oxygen tension, as opposed to iron deficiency, which impairs mitochondrial function, cellular metabolism, enzyme activities, and neurotransmitter synthesis.11,51,52 The important effects of cellular iron deficiency are highlighted by clinical observations of symptomatic improvement in women who are treated for nonanemic iron deficiency,53 as well as interventional studies in patients with congestive heart failure in whom intravenous iron supplementation provided comparable benefits in subjects with IDA, even without correction of anemia.7 However, in contrast to IDA, anemia-related symptoms in AI are often attributed to the underlying disease, which may be 1 reason why AI is often not specifically treated.

Anemia, defined by a Hb concentration <120 g/L for women and <130 g/L for men, can be diagnosed as AI or ACD based on the underlying alterations in iron homeostasis along with clinical or biochemical evidence of inflammation; however, it is often necessary to rule out coexisting causes of anemia that may require specific interventions (Table 2). In addition to assessing coexisting iron deficiency, as discussed further below, laboratory evaluations may include renal and liver function tests, thyroid function tests or markers of hemolysis, and determination of folic acid, cobalamin, or vitamin D concentrations. Vitamin D is a negative regulator of hepcidin expression.54 Elderly subjects with different causes of anemia were often found to suffer from vitamin D deficiency, and anemia can be corrected, in part, by vitamin D supplementation, which decreases hepcidin levels.54,55

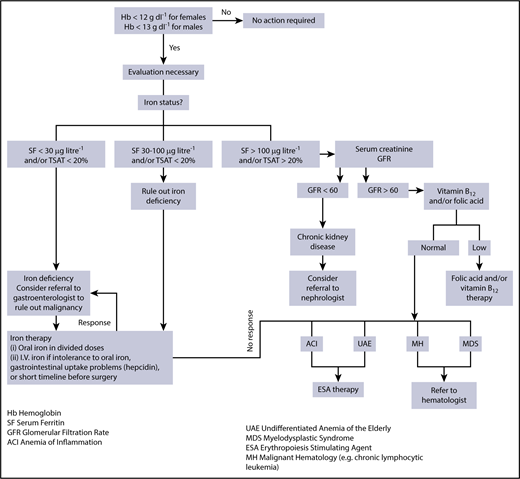

Characteristically, AI presents as a mild to moderate normochromic and normocytic anemia, which clearly separates it from hypochromic and microcytic IDA.50 AI and IDA have in common reduced circulating iron concentrations and a reduced percentage of iron bound to transferrin, known as transferrin saturation, as well as reduced reticulocyte counts. The most useful differentiating parameter is serum ferritin. Whereas a ferritin level <30 µg/mL is associated with absolute or true iron deficiency, patients with AI present with normal or increased ferritin levels (>100 µg/L), depending on the underlying condition.1 Serum ferritin is predominantly secreted by macrophages and hepatocytes.56,57 High concentrations of serum ferritin in AI result from increased ferritin secretion by iron-retaining macrophages but also reflect that ferritin is an acute-phase protein that is induced by various inflammatory mediators.5,56 Thus, in the setting of inflammatory diseases, ferritin largely loses its diagnostic value as an indicator of body iron stores. The circulating concentrations of the iron transport protein transferrin are at the upper limit of normal in IDA subjects but are reduced in subjects with AI, because transferrin expression is negatively affected by cytokines.58 Thus, with these parameters at hand, AI can be diagnosed,18 as illustrated in Figure 2.

Evaluation and management of anemia. Evaluation and management of anemia. Once the screening blood count demonstrates anemia, an evaluation is necessary and begins with an assessment of iron status. When ferritin (SF) and/or iron saturation levels (TSAT) indicate absolute iron deficiency, referral to a gastroenterologist or gynecologist to identify a specific source of chronic blood loss may be indicated. When ferritin and/or iron saturation values rule out absolute iron deficiency, and signs of inflammation are evident, AI is likely. Depending on ferritin, transferrin saturation, or values of markers suggesting concomitant true iron deficiency, diagnostic steps to identify the disease underlying AI and/or the reason for iron deficiency should be undertaken. A nephrologist may be consulted in the case of GFR reduction and evidence for chronic kidney disease. When ferritin and/or iron saturation values are indeterminant, further evaluation to rule out absolute iron deficiency vs inflammation/chronic disease is necessary. A successful therapeutic trial of iron would confirm absolute iron deficiency. No response to iron therapy would support the diagnosis of AI, suggesting that ESA therapy may be beneficial. Reprinted from Goodnough and Schrier8 with permission.

Evaluation and management of anemia. Evaluation and management of anemia. Once the screening blood count demonstrates anemia, an evaluation is necessary and begins with an assessment of iron status. When ferritin (SF) and/or iron saturation levels (TSAT) indicate absolute iron deficiency, referral to a gastroenterologist or gynecologist to identify a specific source of chronic blood loss may be indicated. When ferritin and/or iron saturation values rule out absolute iron deficiency, and signs of inflammation are evident, AI is likely. Depending on ferritin, transferrin saturation, or values of markers suggesting concomitant true iron deficiency, diagnostic steps to identify the disease underlying AI and/or the reason for iron deficiency should be undertaken. A nephrologist may be consulted in the case of GFR reduction and evidence for chronic kidney disease. When ferritin and/or iron saturation values are indeterminant, further evaluation to rule out absolute iron deficiency vs inflammation/chronic disease is necessary. A successful therapeutic trial of iron would confirm absolute iron deficiency. No response to iron therapy would support the diagnosis of AI, suggesting that ESA therapy may be beneficial. Reprinted from Goodnough and Schrier8 with permission.

The diagnostic challenge in AI is the identification of patients with concomitant true iron deficiency (AI/IDA patients), because they need specific evaluation for the source of blood loss and iron-targeted management strategies.1,59,60 A varying percentage (20%-85%) of patients with AI also suffer from true iron deficiency, which is mainly based on concomitant disease-related or unrelated gastrointestinal or urogenital bleeding episodes, iatrogenic blood draws, or losses in association with therapeutic procedures, such as hemodialysis.1,9,10,50,55,59,61-65 Children with AI and chronic inflammatory diseases are at particular risk for coexisting true iron deficiency, because their growth and the expansion of the red cell mass require additional iron.

Although one would expect that subjects with AI/IDA may become microcytic and hypochromic, this pattern is much less pronounced in AI/IDA than in IDA, and a significant overlap between AI and AI/IDA makes the differential diagnosis challenging and inaccurate.18,66 Several alternative cellular markers, including the percentage of hypochromic red blood cells, reticulocyte Hb content, red blood cell Hb content, and red cell distribution width, alone or in combination with iron-metabolism parameters, have been studied for their potential to detect iron deficiency in the presence of inflammation.58,59,65,66 Although some of these tests showed promise, the analyses greatly depend on the availability of appropriate laboratory instruments and on standardized preanalytical procedures. Moreover, most of these tests have never been prospectively studied to evaluate their true diagnostic potential for differentiating AI vs AI/IDA, for the prediction of response to the chosen therapy, or as indicators of potential harm (eg, iron oversupplementation).65,67 Even soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR), a valuable measure of iron requirements for erythropoiesis, is confounded by inflammation, because several cytokines affect sTfR levels independently of iron status.68 The ferritin index, which is calculated by sTfR/log ferritin values, provided a better discrimination between AI (<1) and AI/IDA (>2) subjects, admittedly with some overlap and a clinically relevant zone of uncertainty.58,64,69 Based on our expanding knowledge of the pathophysiology of AI, hepcidin measurement may eventually play a role in the evaluation and management of AI (Table 3).19,61,70,71 The potential utility of hepcidin measurements in this context was based on observations showing that, although hepcidin levels are increased in AI, they are significantly reduced in the presence of concomitant iron deficiency. The mechanism could be traced back to induction of inhibitory SMAD proteins by iron deficiency, which reduced inflammation-driven hepcidin expression, suggesting that inhibitory erythropoietic signals dominate over inflammation-driven hepcidin induction.72,73 Although serum hepcidin may help to differentiate AI and AI/IDA subjects,19 a hepcidin assay alone is not definitive (Table 3). Nonetheless, hepcidin determination is a promising diagnostic tool when used in combination with other established tests16,19,71,74 or emerging novel markers, such as erythroferrone. Of note, hepcidin levels may predict the response to therapy with oral iron, and if treatment with oral iron has not been efficient after 2 weeks, a switch to IV iron is indicated75 (Table 3). The differentiation between AI and AI/IDA is also an important consideration when managing dialysis patients; however, hepcidin levels are increased in these subjects as a consequence of impaired renal hepcidin excretion and are of limited diagnostic value.67 Thus, there is still a need for readily available and interpretable biomarkers that clearly differentiate between ACD and ACD/AI patients at beside and help to identify the best therapy and predict the therapeutic response.75

Potential role of hepcidin in the diagnosis and management of anemia

| Condition . | Expected hepcidin levels . | Iron variables . | Iron therapy strategies . | Potential hepcidin therapy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute IDA | Low | Low Tsat and ferritin | PO (or IV if PO poorly tolerated or malabsorbed) | No |

| Functional iron deficiency (ESA therapy, CKD) | Variable, depending on the severity and etiology of CKD | Low Tsat, variable ferritin | IV or oral if low disease activity | Antagonist (if hepcidin levels not low) |

| Iron sequestration (AI) | High | Low Tsat, normal to elevated ferritin | IV | Antagonist |

| Mixed anemia (AI/IDA or AI/functional iron deficiency) | Variable | Low Tsat, low to normal ferritin | IV or oral if low disease activity | Antagonist (if hepcidin levels not low) |

| Iron-loading anemias (eg, ineffective erythropoiesis) | Low | High Tsat and ferritin | Iron chelation therapy | Agonist |

| Iron-loading anemias treated with transfusion | Normal to high | High Tsat and ferritin | Iron chelation therapy | Agonist |

| Condition . | Expected hepcidin levels . | Iron variables . | Iron therapy strategies . | Potential hepcidin therapy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute IDA | Low | Low Tsat and ferritin | PO (or IV if PO poorly tolerated or malabsorbed) | No |

| Functional iron deficiency (ESA therapy, CKD) | Variable, depending on the severity and etiology of CKD | Low Tsat, variable ferritin | IV or oral if low disease activity | Antagonist (if hepcidin levels not low) |

| Iron sequestration (AI) | High | Low Tsat, normal to elevated ferritin | IV | Antagonist |

| Mixed anemia (AI/IDA or AI/functional iron deficiency) | Variable | Low Tsat, low to normal ferritin | IV or oral if low disease activity | Antagonist (if hepcidin levels not low) |

| Iron-loading anemias (eg, ineffective erythropoiesis) | Low | High Tsat and ferritin | Iron chelation therapy | Agonist |

| Iron-loading anemias treated with transfusion | Normal to high | High Tsat and ferritin | Iron chelation therapy | Agonist |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; PO, by mouth; Tsat, transferrin saturation.

Treatment

Any consideration of treatment in AI must take into account its evolutionary context. AI results from a conserved defense strategy of the body directed against invading microbes. Iron is an essential nutrient for humans and other animals, as well as for most microbes, which require iron for their proliferation and pathogenicity. By the combined action of cytokines, hepcidin, and iron-binding peptides, as outlined in Pathophysiology of AI, iron is sequestered in forms that make it less accessible to circulating pathogens, a strategy termed “nutritional immunity.”76,77 In this context, tissue- and cell-specific changes in iron trafficking depend on the type and location of the pathogen (ie, extracellularly or within a specific cellular compartment),78-80 with details under intensive study. In addition, iron availability exerts subtle effects on immune function by modulating immune cell differentiation and proliferation, and it also affects antimicrobial effector mechanisms of immune cells.76 Thus, when treating anemias, one has to consider whether such a treatment could also impact the underlying disease; this is of utmost concern when treating patients with infections or cancer.

Optimally, the best treatment for AI is cure of the underlying inflammatory disease, which mostly results in resolution of AI. As much as is feasible, the contribution of concomitant pathologies to AI (Table 2) should also be considered and specifically corrected; however, such fundamental treatments are not always possible or effective. With regard to treatments directed specifically at AI, we lack data from prospective trials about how aggressive such treatments should be or what constitutes the optimal therapeutic end point. Caution is suggested by studies indicating that, in environments with a high endemic burden of infectious diseases, mild anemia and/or iron deficiency may even be beneficial. Infants with mild iron deficiency or anemia were less likely to suffer and die from severe malaria.81 Indiscriminate dietary iron fortification resulted in increased morbidity and mortality from serious infections, including malaria and enteric infections.82,83 Such studies indicate that care should be taken to identify those patients with AI, with or without iron deficiency, who can benefit from iron supplementation or anemia correction.84 Although not yet widely used, low pretreatment serum hepcidin concentration appears to be a good predictor of therapeutic response to oral iron supplementation, thus potentially avoiding risks to patients who could not benefit from oral iron supplementation.85

Two therapies have been established for the treatment of AI: iron supplementation and treatment with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs). Red blood cell transfusion is considered only as an emergency treatment in patients with severe anemia who are clinically unstable and in whom rapid correction of Hb levels is warranted.48,86 Of interest, recent evidence suggested that restrictive use of blood transfusion, specifically in critically ill patients with acute bleeding, is associated with a lower mortality than liberal use achieving higher target Hb levels.87 Given the increasing evidence that blood transfusions have poor effectiveness and are possibly harmful, the guiding principle for transfusion therapy should be “less is more.”88 Anemic patients with inflammatory bowel disease89 and rheumatoid arthritis77,90 have very mild anemias that are corrected by anti-TNF therapy.89,90 Patients with more severe anemia often have other pathophysiologic components that are treatable with iron or ESA therapy,91 as illustrated in Figure 2.

Recombinant human ESAs have been used successfully for the treatment of AI for many years, specifically in patients with cancer or renal failure or when iron supplementation alone was ineffective.1,68 However, concerns about the unrestricted use of ESAs in AI arose from studies showing higher mortality in patients with cancer or in dialysis patients not immediately responding to ESA treatment, as well as in nondialysis patients treated with novel erythropoiesis-stimulating drugs.92-94 The specific mechanisms of increased mortality remain elusive but may include effects of ESAs on coagulation or angiogenesis, direct proliferative effects of ESAs on cancer cells expressing EpoRs, or the immune-modulatory effects of ESAs that may dampen antimicrobial effector function.92,95,96 Nevertheless, ESA therapy remains approved for a variety of indications, including patients who are anemic (and in whom iron deficiency has been ruled out) and scheduled for major noncardiac surgery (Table 4).91

ESAs: current approval status

| . | Perisurgical . | PAD . | ESKD predialysis/dialysis . | CIA . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | No | Yes (1993) | Yes (1990/1994) | No |

| European Union | No | Yes (1994) | Yes (1988/1990) | Yes (1994) |

| United States | Yes (1996) | No | Yes (1989/1990) | Yes (1993) |

| Canada | Yes (1996) | Yes (1996) | Yes (1900/1900) | Yes (1995) |

| . | Perisurgical . | PAD . | ESKD predialysis/dialysis . | CIA . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | No | Yes (1993) | Yes (1990/1994) | No |

| European Union | No | Yes (1994) | Yes (1988/1990) | Yes (1994) |

| United States | Yes (1996) | No | Yes (1989/1990) | Yes (1993) |

| Canada | Yes (1996) | Yes (1996) | Yes (1900/1900) | Yes (1995) |

Year of approval is shown in parentheses.

CIA, chemotherapy-induced anemia; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; PAD, preoperative autologous donation.

Iron-replenishing strategies have attracted renewed interest in AI therapy, either alone or in combination with low to moderate doses of ESAs. Although oral or IV iron therapy appears to be justified in patients with combined AI/IDA, new treatment strategies that mobilize sequestered iron from the reticuloendothelial system by targeting hepcidin make more sense for subjects with pure AI. Accurate diagnostic tools will be needed to correctly discriminate AI and AI/IDA subjects for future trials of these approaches.

Oral iron preparations are available as iron salts or iron carbohydrates and are the therapy of choice in AI subjects with true iron deficiency and mild inflammation, in whom they show an efficacy that is comparable to IV preparations.97,98 However, in specific disease conditions, IV iron may be preferable, even with low inflammation (eg, chronic heart failure) or under circumstances when data on the therapeutic efficacy of oral iron therapy are not available, as reviewed recently.99,100 In general, oral iron preparations should be taken once in the morning at a minimum dose of 50 mg of ferrous iron (the total compound dose depends on the specific iron salt or glycan used). More frequent dosing reduces iron bioavailability by increased production of hepcidin, inhibiting iron absorption.101 Ascorbic acid and overnight fasting can increase iron bioavailability, whereas proton pump inhibitors or several foods, including milk products and tea, decrease iron absorption.11,50,63 IV iron therapy is indicated when oral iron treatment is insufficient to correct iron deficiency, such as during ongoing blood loss in dysfunctional uterine bleeding or multiple vascular malformations in the gastrointestinal tract, in the presence of gastrointestinal side effects, or when a rapid replenishment of iron stores is desired, such as prior to a planned surgery. Insufficient absorption of iron in the duodenum is a major problem in AI patients, because of inhibition of iron transfer from enterocytes to the circulation by hepcidin and cytokines.16,19 In addition to older IV iron-carbohydrate formulations, such as ferric gluconate or ferric sucrose, newer glycan-coated nanoparticle drugs, such as iron carboxymaltose, iron isomaltoside, and ferumoxytol, have been introduced into clinical practice, which allow administration of up to 1000 mg of iron per injection. The rare life-threatening anaphylactoid reactions that occurred after iron injections resulted in warning letters from the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency,102 and strategies have been implemented to identify susceptible patients and to reduce the risk of serious side effects.103 IV iron has been shown to successfully correct iron deficiency in AI patients,62 and it is especially effective in patients with inflammatory bowel disease who often suffer from concomitant true iron deficiency as a consequence of chronic intestinal bleeding.61,63 Severe systemic inflammation may even make IV iron therapy less effective, because IV iron-glycan complexes are primarily taken up by macrophages, and iron is subsequently exported from macrophages to transferrin in the circulation via ferroportin. The expression and activity of ferroportin are inhibited by hepcidin, which is present at higher concentration in such patients.16,104 In this instance, ESA therapy may be helpful, because it stimulates erythropoiesis while suppressing hepcidin.

Based on our knowledge of the pathophysiology of AI, with the underlying iron retention in the reticuloendothelial system and the central role of hepcidin in this process (Figure 1), novel therapeutic approaches have emerged that aim to antagonize hepcidin function and to mobilize iron from macrophages to deliver it for erythropoiesis (Table 3). Such strategies have been evaluated in animal models and are beginning to reach human clinical trials. General mechanisms involve inhibition of hepcidin production, neutralization of circulating hepcidin, protection of ferroportin function from hepcidin inhibition, and inhibition of hepcidin-inducing signals, such as IL-6; all were summarized in recent reviews.9,105 Of note, hepcidin-antagonizing strategies and increased egress of iron from the reticuloendothelial system to the circulation may affect the disease underlying ACD, potentially detrimentally (eg, in infections) or beneficially (eg, chronic kidney disease).79,106 Nonetheless, hepcidin-modifying strategies may hold promise in combination with ESA,107 because the increased endogenous delivery of iron may reduce ESA requirements and limit their adverse effects.

A novel therapeutic principle emerged from the introduction of prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors, which stabilize hypoxia-inducible factors and subsequently ameliorate anemia by promoting endogenous Epo formation and iron delivery from enterocytes and macrophages.108 These orally available drugs are being studied in phase 3 clinical trials for the treatment of anemia in hemodialysis,109 but they could also become useful therapeutic options in AI.

Outlook

Our knowledge on the pathophysiology of AI has expanded dramatically over the past years, and we are gathering information on the therapeutic efficacy of established and novel emerging treatment strategies. However, we are still lacking information on optimal therapeutic start and end points for AI and are in need of identifying biomarkers that help to differentiate patients with AI from patients with AI and true iron deficiency, because different treatment strategies are used for these 2 groups. Moreover, we have to gather information on the effects of any treatment on the course of the specific disease underlying AI. This is essential to choose the best therapeutic options for our patients to achieve an optimal quality of life or cardiovascular performance, together with a neutral, or even beneficial, effect on the primary disease causing AI.

Acknowledgments

G.W. is grateful for support from the Christian Doppler Society.

Authorship

Contribution: G.W., T.G., and L.T.G. were responsible for conception and design, as well as the writing and final approval of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: G.W. has received lecture honoraria from Vifor. L.T.G. is a consultant for Vifor Pharma and InCube Labs. T.G. is a consultant for Keryx Pharma, Vifor Pharma, Akebia Therapeutics, Gilead Sciences, La Jolla Pharma, and Ionis Pharmaceuticals; has received research funding from Keryx Pharma and Akebia Therapeutics; and is a scientific founder and consultant for Silarus Pharma and Intrinsic LifeSciences.

Correspondence: Guenter Weiss, Department of Internal Medicine II, Infectious Diseases, Immunology, Pneumology and Rheumatology, Medical University Innsbruck, Anichstr 35, A-6020 Innsbruck, Austria; e-mail: guenter.weiss@i-med.ac.at.

![Figure 1. Pathophysiological mechanisms of AI. Systemic inflammation results in immune cell activation and formation of numerous cytokines. Interleukin (IL-6) and IL-1β, as well as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), are potent inducers of the master regulator of iron homeostasis, hepcidin, in the liver, whereas expression of the iron-transport protein transferrin is reduced. Hepcidin causes iron retention in macrophages by degrading the only known cellular iron exporter ferroportin (FP1); by the same mechanism, it blocks dietary iron absorption in the duodenum. Multiple cytokines (eg, interleukin-1β [IL-1β], IL-6, IL-10, and interferon-γ [IFN-γ]) promote iron uptake into macrophages, increase radical-mediated damage to erythrocytes and their ingestion by macrophages, and cause efficient iron storage by stimulating ferritin production and blocking iron export by transcriptional inhibition of FP1 expression. This results in the typical changes of AI (ie, hypoferremia and hyperferritinemia). In addition, IL-1 and TNF inhibit the formation of the red cell hormone erythropoietin (Epo) by kidney epithelial cells. Epo stimulates erythroid progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation, but the expression of its erythroid receptor (EpoR) and EpoR-mediated signaling are inhibited by several cytokines. Moreover, cytokines can directly damage erythroid progenitors or inhibit heme biosynthesis via radical formation or induction of apoptotic processes. Importantly, because of iron restriction in macrophages, the availability of this metal for erythroid progenitors is reduced. Erythroid progenitors acquire iron mainly via transferrin-iron/transferrin receptor (Tf/TfR)-mediated endocytosis. Erythroid iron deficiency limits heme and hemoglobin (Hb) biosynthesis, as well as reduces EpoR expression and signaling via blunted expression of Scribble (Scb). In addition, the reduced Epo/EpoR signaling activity impairs the induction of erythroferrone (Erfe), which normally inhibits hepcidin production.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/133/1/10.1182_blood-2018-06-856500/9/m_blood856500f1.png?Expires=1768488254&Signature=g070BDbYZ2Q0uOiiyK4paHJgOcyGmenmzAep8-PkIDdMmnrBiWc0ILMUoenkiNT~ALK3wK8Jc8hUCQNx-SwfeoBAep0ss2dRzv0z94D0hndhlaeWodc~isEgRCXymzr-wZc~QwLXPeGORG53ygwKtxnxnTv~6Faa8b42LjmGSlceMooXalF9juLJe1SDifkcYemKffXlA6BqpcQrr5wV5sqGfrZR17x5gVk5-fs10rkUn7ohrqBnQwYiSrz0cVC5Ab~hzQtt70DfJr6aly2OLo9R6qS-ZNLniOALvM9s0Ev9nio4rplo4ury1ram1qFnGWsZC9iOr77jmYKIvfoEsg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal