Key Points

Loss of 1 copy of Ctnnb1 (encoding β-catenin) in an Apc-haploinsufficient microenvironment prevents the development of MDS.

Modulation of WNT signaling in the niche using pyrvinium inhibits the development of MDS in Apc-haploinsufficient mice.

Abstract

There is accumulating evidence that functional alteration(s) of the bone marrow (BM) microenvironment contribute to the development of some myeloid disorders, such as myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML). In addition to a cell-intrinsic role of WNT activation in leukemia stem cells, WNT activation in the BM niche is also thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of MDS and AML. We previously showed that the Apc-haploinsufficient mice (Apcdel/+) model MDS induced by an aberrant BM microenvironment. We sought to determine whether Apc, a multifunctional protein and key negative regulator of the canonical β-catenin (Ctnnb1)/WNT-signaling pathway, mediates this disease through modulating WNT signaling, and whether inhibition of WNT signaling prevents the development of MDS in Apcdel/+mice. Here, we demonstrate that loss of 1 copy of Ctnnb1 is sufficient to prevent the development of MDS in Apcdel/+ mice and that altered canonical WNT signaling in the microenvironment is responsible for the disease. Furthermore, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drug pyrvinium delays and/or inhibits disease in Apcdel/+ mice, even when it is administered after the presentation of anemia. Other groups have observed increased nuclear CTNNB1 in stromal cells from a high frequency of MDS/AML patients, a finding that together with our results highlights a potential new strategy for treating some myeloid disorders.

Introduction

The myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) include a spectrum of clonal hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) disorders that are characterized by ineffective hematopoiesis, peripheral cytopenia(s), morphologic dysplasia, and a variable propensity to transform to acute myeloid leukemia (AML).1 Cytogenetic abnormalities are incorporated into the diagnostic and prognostic classification of MDS.1 A del(5q) is the most common recurring cytogenetic abnormality, and is observed in 10% to 20% of primary MDS, and 40% of therapy-related MDS/AML, patients.2,3 Our laboratory has had a long-standing interest in elucidating how loss of function of tumor suppressor genes on 5q, such as early growth response 1 (EGR1) and adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), contributes to the pathogenesis of MDS and AML. In addition to cytogenetic abnormalities, somatic mutations contributing to the pathogenesis of the disease are common in MDS, with >75% of patients carrying ≥1 abnormality in the 30 most frequently mutated genes.4-7

Recent studies highlight the role of the complex bidirectional crosstalk between HSCs and the bone marrow (BM) niche in normal hematopoiesis as well as in the pathogenesis of myeloid diseases.8 Multiple cell types contribute to the niche, including various mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC) populations, and progeny cells derived from MSCs, such as osteoblasts.9,10 Although not fully understood, emerging data suggest that niche alterations play a role in the pathogenesis of myeloid neoplasms.8 In MDS and AML, there is evidence that patient-derived MSCs may have cytogenetic abnormalities that are distinct from their hematopoietic counterparts, have unique methylation signatures, are impaired in supporting hematopoietic function, and promote the malignant behavior of human MDS stem cells and their progeny.8,11-15 In mice, the deletion of Rb116 or Rarg (RARγ),17 or haploinsufficiency of Crebbp18 or Apc19-21 in the BM microenvironment promoted the development of myeloproliferation and/or myelodysplasia. In addition, dysregulated expression of Dicer122 or Ctnnb123 in cells of the osteoblastic lineage was sufficient to promote the development of MDS or AML in mice.

Canonical WNT signaling has been implicated in the regulation of hematopoiesis as well as the aberrant renewal of HSCs that drives leukemia formation.24 Under steady-state conditions, the so-called “destruction complex,” which is composed of the APC tumor suppressor, the Ser-Thr kinases (glycogen synthase kinase 3β [GSK-3β] and casein kinase 1α [CK1α]) as well as the scaffold protein AXIN1, is responsible for the phosphorylation and breakdown of CTNNB1.25 The WNT-signaling pathway is activated by the inhibition of this complex, leading to the intracellular stabilization and translocation of CTNNB1 to the nucleus. Graded WNT signaling in HSCs has differential effects, with high activation leading to BM failure, whereas less profound activation leads to HSC expansion.26 Gene expression profiling of hematopoietic cells supports a role for WNT pathway activation in MDS, AML, and therapy-related myeloid neoplasms (t-MN).19,27-30 Moreover, WNT activation in HSCs has been directly implicated in self-renewal of leukemia stem cells, and is associated with a poorer outcome in mouse models and in AML patients.19,21,31-34

WNT activation in the BM niche may also contribute to the pathogenesis of MDS and AML. First, WNT signaling has been shown to inhibit differentiation of MSCs into chondrocytes and adipocytes, but promote osteoblastic proliferation and differentiation.35,36 Second, mice genetically altered to express a constitutively active mutant allele of Ctnnb1 in osteoblastic cells develop AML with 100% penetrance due to the upregulation of the Notch ligand, Jagged 1 (Jag1, a Ctnnb1 transcriptionally regulated gene), in the osteoblasts.23 Of relevance to human disease, activation of CTNNB1 (demonstrated by nuclear localization) was observed in osteoblastic cells in 38% of MDS/AML patients studied.23 Furthermore, differential expression of WNT signaling genes and significantly increased JAGGED-1 messenger RNA (mRNA) levels have been observed in MDS-derived MSCs as compared with MSCs derived from healthy individuals.37,38

In previous studies, we modeled activation of WNT signaling in the BM microenvironment, and showed that haploinsufficient loss of Apc in the BM niche promotes the development of MDS with a severe macrocytic anemia.20,21 Apc is a multifunctional protein and, in addition to regulating WNT signaling, it has roles in regulating cell cycle progression,39 cell migration,40 and mitosis via control of spindle orientation and chromosome segregation,41,42 as well as the regulation of DNA methylation.43 Thus, the goal of this study was to determine whether canonical WNT signaling in the BM microenvironment was, in fact, mediating the development of MDS in Apc-haploinsufficient mice. Herein, we show that loss of only 1 copy of Ctnnb1 or administration of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved WNT inhibitor, pyrvinium,44 prevented the development of disease in Apc-haploinsufficient mice, which model MDS induced by WNT activation in the microenvironment. These results suggest that administration of pyrvinium may be a rational treatment strategy, notably for the subset of MDS/AML patients who display the accumulation of nuclear CTNNB1 in the marrow stromal cell compartment.

Methods

Mouse strains and transplantation studies

All studies were approved by the University of Chicago’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and mice were housed in a facility fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Mx1-Cre−Apcfl/+ (Apcfl/+) and Mx1-Cre+Apcfl/+ (Apcdel/+), Mx1-Cre−Ctnnb1fl/+ (Ctnnb1fl/+) and Mx1-Cre+Ctnnb1fl/+ (Ctnnb1del/+) mice were generated by crossing Mx1-Cre transgenic mice45 with Apcfl/fl46 or Ctnnb1fl/fl mice47 (B6.129-Ctnnnb1tm2Kem/KnwJ; purchased from JAX mice, Bar Harbor, ME). All mice are on a C57BL/6J genetic background. Deletion of the floxed allele in blood cells, after 3 intraperitoneal (IP) injections with 10 mg/kg polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (pIpC; GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA) when mice were 2 months old, was verified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), as previously described.47,48 Where indicated, total BM cells (∼3 × 106 to 5 × 106 cells) isolated from B6.SJL (CD45.1) mice were transplanted, via retro-orbital injection, into lethally irradiated (8.6 Gy) Apcfl/+, Apcdel/+, or Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ mice (CD45.2) that had been pretreated, 3 to 4 weeks prior to irradiation, with pIpC to induce deletion of the floxed alleles. Peripheral blood, histology, flow cytometric, and statistical analysis were done as previously described.20,49

In vivo administration of PT

Pyrvinium tosylate (PT) salt: 6-(dimethylamino)-2-[(E)-2-(2,5-dimethyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrrol-3-yl)ethenyl]-1-methylquionlimium 4-methylbenzenesulfonate was purchased from Symansis (Timaru, New Zealand). Dilutions of PT were prepared from a working stock of 10 mg/mL dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). PT was administered by IP injection at the doses indicated. Apcdel/+ mice were injected IP twice weekly; the duration of treatment and doses are indicated in the figure legends.

Treatment of MSCs with Wnt3a and PT

For mice, femur, tibia, and humerus bones were isolated and flushed to remove hematopoietic BM cells, treated with collagenase, and cultured using MesenCult (Mouse) with MesenPure in 5% O2 according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada). The AML and MDS patient samples were obtained with informed consent and approved by the University of Chicago Medicine Institutional Review Board. MDS and AML hematopoietic cells incubated for 24 hours for routine cytogenetic analysis were removed, and MesenCult was added to an empty flask to grow out adherent MSCs using MesenCult (Human) in 20% O2. MSCs were stained with antibodies specific for CD45 to confirm absence of hematopoietic cells and used between passages 1 and 3 (mice) and 2 and 3 (human). Because Wnt ligands are secreted in the BM microenvironment50 and a reduction in APC function has been shown to sensitize cells to Wnt ligands,51 we wanted to examine the effect of Apc haploinsufficiency both with and without Wnt ligand. MSCs were stimulated with 50 ng/mL recombinant mouse Wnt3a (Pepro Tech, Rocky Hill, NJ) or human WNT3A (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) with or without 50 nM PT for times indicated. Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions (NE-PER kit; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for Ctnnb1 (β-catenin) (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ), β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), Hdac1 and Lamin A/C (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas TX). Quantitative PCR was performed as previously described.52 Primer sequences are provided in supplemental Table 1 (see supplemental Data, available on the Blood Web site).

Results

Loss of 1 copy of Ctnnb1 prevents the development of MDS in Apcdel/+ mice

Apc is a key negative regulator of the canonical WNT-signaling pathway25 ; however, it also plays WNT-independent roles in cytoskeletal regulation and chromosome segregation.40,41 To determine whether the observed disease is due to Apc’s role in canonical WNT signaling, we generated mice that were haploinsufficient for both Apc and Ctnnb1, the gene encoding β-catenin, the intracellular signal transducer of the WNT-signaling pathway.

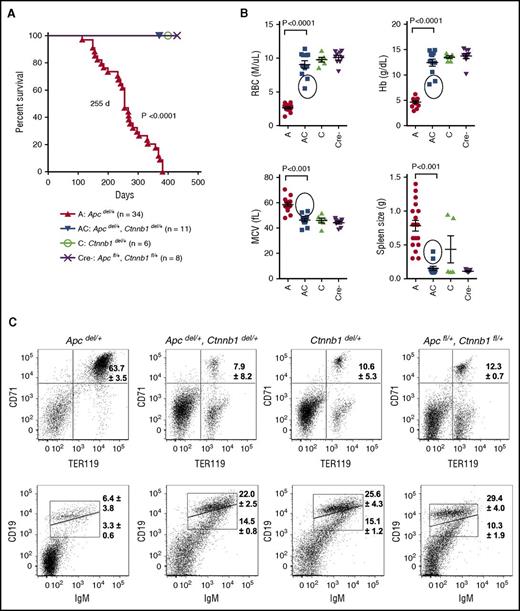

Mx1-Cre+Apcfl/+ (referred herein as Apcdel/+) mice develop a fatal MDS, 4 to 12 months (median survival, 255 days) after inducible deletion of 1 allele of the Apc gene.20,21 In contrast, all Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ mice survived until the end of the study (∼400 days), demonstrating that loss of only 1 copy of Ctnnb1 was sufficient to prevent disease (Figure 1A). Compared with the phenotype of Apcdel/+ mice at the time of sacrifice, Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ (AC), Ctnnb1del/+ (C), and Apcfl/+, Ctnnb1fl/+ (Cre−) mice typically did not show evidence of severe macrocytic anemia or splenomegaly when assessed at ∼400 days (Figure 1B). Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis of the spleen cells also confirmed the presence of a block at the basophilic erythroblast, or R2 (CD71+Ter119+) stage and effacement of splenic white pulp, as reflected by a decrease in CD19+ immunoglobulin M–positive (IgM+) B cells, observed in Apcdel/+ mice, but not Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ mice (Figure 1C).

Loss of 1 copy of Ctnnb1 is sufficient to prevent fatal macrocytic anemia in Apcdel/+ mice. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for Apcdel/+ (A; n = 34), Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ (AC; n = 11), Ctnnb1del/+ (C; n = 6), and Apcfl/+, Ctnnb1fl/+ (Cre−; n = 8) control mice. The median survival of Apcdel/+ mice was 255 days (previously published by Stoddart et al20 ); thus, the A and AC mice were not littermates in this figure. All other mouse cohorts, monitored monthly for the development of macrocytic anemia, survived until the end of the study (∼400 days) (B) RBC parameters from complete blood counts (CBCs) and spleen size. CBCs and spleen size for Apcdel/+ mice were measured at the time of sacrifice, and for the other 3 cohorts were measured at the end of the study (∼400 days). Circles represent 2 Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ mice that displayed moderate anemia and splenomegaly at the end of the study, suggestive of the onset of MDS. (C) Representative flow cytometric analysis of erythroid (CD71+Ter119+) and B cells (CD19+IgM+) in spleen isolated from mice for each cohort. Shown is the average percentage of CD71+Ter119+ erythroblasts and CD19loIgM+ (immature) and CD19hiIgM+ (mature) B cells from at least 3 mice from each cohort. In contrast to Apcdel/+ mice, 9 of 11 Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ mice (82%) had a normal distribution of erythroid cells and B cells in the spleen, similar to controls. Analysis of the 2 exceptional Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ mice with splenomegaly and moderate anemia is shown in supplemental Table 2. MCV, mean corpuscular volume.

Loss of 1 copy of Ctnnb1 is sufficient to prevent fatal macrocytic anemia in Apcdel/+ mice. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for Apcdel/+ (A; n = 34), Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ (AC; n = 11), Ctnnb1del/+ (C; n = 6), and Apcfl/+, Ctnnb1fl/+ (Cre−; n = 8) control mice. The median survival of Apcdel/+ mice was 255 days (previously published by Stoddart et al20 ); thus, the A and AC mice were not littermates in this figure. All other mouse cohorts, monitored monthly for the development of macrocytic anemia, survived until the end of the study (∼400 days) (B) RBC parameters from complete blood counts (CBCs) and spleen size. CBCs and spleen size for Apcdel/+ mice were measured at the time of sacrifice, and for the other 3 cohorts were measured at the end of the study (∼400 days). Circles represent 2 Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ mice that displayed moderate anemia and splenomegaly at the end of the study, suggestive of the onset of MDS. (C) Representative flow cytometric analysis of erythroid (CD71+Ter119+) and B cells (CD19+IgM+) in spleen isolated from mice for each cohort. Shown is the average percentage of CD71+Ter119+ erythroblasts and CD19loIgM+ (immature) and CD19hiIgM+ (mature) B cells from at least 3 mice from each cohort. In contrast to Apcdel/+ mice, 9 of 11 Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ mice (82%) had a normal distribution of erythroid cells and B cells in the spleen, similar to controls. Analysis of the 2 exceptional Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ mice with splenomegaly and moderate anemia is shown in supplemental Table 2. MCV, mean corpuscular volume.

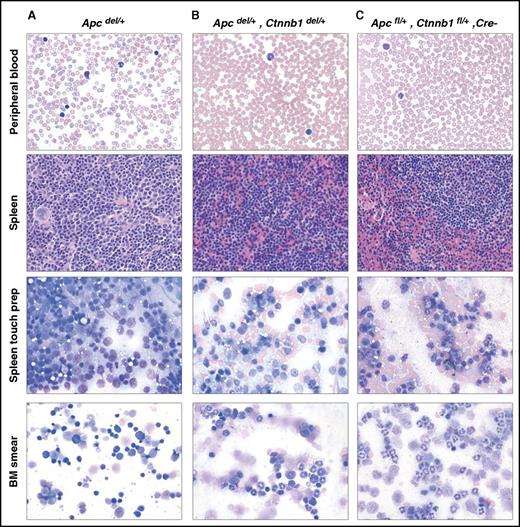

Histological analysis of Apcdel/+ mice demonstrated that they develop MDS characterized by severe anemia with macrocytosis, anisocytosis, and poikilocytosis in the peripheral blood and effacement of the normal splenic architecture. Marked erythroid and megakaryocytic hyperproliferation as well as dyserythropoiesis were observed in both BM and spleen (Figure 2A). Strikingly, histological analysis of blood, spleen, and BM of Apcdel/+, Ctnnbdel/+ mice at 400 days was normal (Figure 2B) and similar to WT-Cre− controls (Figure 2C).

Decreasing Ctnnb1 levels in Apcdel/+ mice reverses the MDS phenotype. Histology of hematopoietic tissues from a representative Apcdel/+ mouse (A, mouse 3938) euthanized when displaying severe signs of anemia (241 days) vs an Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ mouse (B, mouse 8455), and an Apcfl/+, Ctnnb1fl/+, Cre− mouse (C, mouse 8740) euthanized at the end of the study (∼400 days). All images were obtained using an Olympus BX41 microscope (Melville, NY) and a 50×/0.9 (oil) or 40×/0.9 objective. Images were processed with Adobe Photoshop (San Jose, CA). Peripheral blood smears, BM smears, and spleen touch preparations were stained with Wright-Giemsa (original magnification ×500), and spleen sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; original magnification ×400).

Decreasing Ctnnb1 levels in Apcdel/+ mice reverses the MDS phenotype. Histology of hematopoietic tissues from a representative Apcdel/+ mouse (A, mouse 3938) euthanized when displaying severe signs of anemia (241 days) vs an Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ mouse (B, mouse 8455), and an Apcfl/+, Ctnnb1fl/+, Cre− mouse (C, mouse 8740) euthanized at the end of the study (∼400 days). All images were obtained using an Olympus BX41 microscope (Melville, NY) and a 50×/0.9 (oil) or 40×/0.9 objective. Images were processed with Adobe Photoshop (San Jose, CA). Peripheral blood smears, BM smears, and spleen touch preparations were stained with Wright-Giemsa (original magnification ×500), and spleen sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; original magnification ×400).

Of the 11 Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del//+ mice, there were 2 exceptional mice that displayed the onset of anemia, splenomegaly, and marked erythroid proliferation at ∼400 days (circled in Figure 1B and supplemental Table 2). The late onset of disease in 18% (2 of 11) of these mice is unlikely to be due to a failure to delete Ctnnb1 (we confirmed deletion of the floxed allele in approximately the same proportion of blood cells examined from all mice). However, we cannot confirm that Ctnnb1 expression in the MSCs of these 2 mice was sufficiently low to counteract activated WNT signaling over an extended period of time. Together, these data show that a decrease in Ctnnb1 levels in Apcdel/+ mice was sufficient to reverse the MDS phenotype.

Canonical WNT signaling in the BM microenvironment is responsible for MDS in Apcdel/+ mice

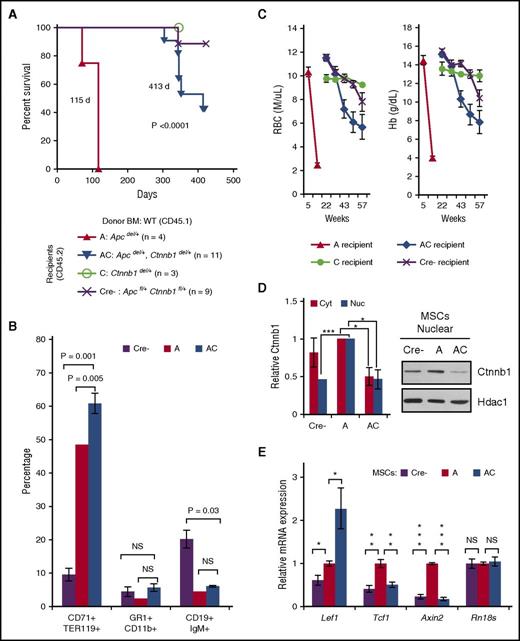

We previously showed that the Apcdel/+-induced disease is cell extrinsic.20 To determine whether WNT signaling in the BM microenvironment was responsible for mediating disease, we transplanted wild-type (WT; CD45.1) hematopoietic cells into CD45.2 Apcdel/+ (A), Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ (AC), Ctnnb1del/+ (C), or Apcfl/+, Ctnnb1fl/+ (Cre−) lethally irradiated recipient mice. Similar to our previous study, Apcdel/+ recipients were euthanized by ∼4 months of age due to a severe anemia. In contrast, Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ recipients survived on average 8 to 10 months longer (median survival, 115 vs 413 days; P < .0001) (Figure 3A). Although Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ recipients survived much longer, 45% (5 of 11) of them ultimately developed MDS with anemia, splenomegaly, and an increased percentage of CD71+Ter119+ erythroblasts and decreased CD19+IgM+ B cells in the spleen similar to Apcdel/+ recipients (Figure 3B-C; supplemental Figure 1). In contrast to Apcdel/+ recipients that were sacrificed due to severe anemia by 16 weeks, moderate anemia was not detected in the Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ recipients until 40 weeks (Figure 3C). Thus, the longer survival in Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ recipients was due to the delayed development or the slower progression of disease. Two Cre− control recipients became moderately anemic around 57 weeks; however, these mice did not develop MDS.

Loss of 1 copy of Ctnnb1 in an Apc-haploinsufficient microenvironment prevents or delays the development of MDS by 8 to 10 months. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for Apcdel/+ (A; n = 4), Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ (AC; n = 11), Ctnnb1del/+ (C; n = 3), and Apcfl/+, Ctnnb1fl/+ (Cre−; n = 9) recipient mice. Median survival of Apcdel/+ and Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ recipient mice was significantly different (115 vs 413 days; P < .0001). All control mice (C and Cre−) survived until the end of the study, with the exception of 1 Apcfl/+, Ctnnb1fl/+ recipient that died at 343 days, likely due to a hemorrhagic renal cyst. (B) Percentage of CD71+Ter119+ erythroid cells, Gr1+CD11b+ myeloid cells, and CD19+IgM+ B cells in spleen isolated from Cre− (∼400 days), A (70-115 days), and AC (303-413 days) recipients that eventually displayed a fatal anemia. At sacrifice, the AC cell populations were more similar to A than Cre− recipients. (C) RBC and Hb counts in all 4 cohorts over time. The development of anemia is delayed in AC recipients after 35 weeks (a point in time when all A recipients have already been sacrificed due to severe anemia). In Cre− control recipients, 2 mice developed moderate anemia at 57 weeks. However, 1 mouse had an apparent colorectal tumor, and the other had a hemorrhagic renal cyst; neither had developed MDS. (D) MSCs were isolated from Cre− (control), A, and AC littermates 2 months posttreatment with pIpC to induce Cre-mediated deletion, and before development of disease. Following in vitro Wnt3a stimulation for 6 hours, nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were isolated and immunoblotted with Ctnnb1, β-actin (cytoplasmic), and Hdac1 (nuclear) antibodies. Quantification of 3 independent experiments shows increased nuclear and cytoplasmic Ctnnb1 protein expression in Apcdel/+ MSCs that is reduced by ∼50% upon haploinsufficient loss of Ctnnb1. (E) RNA was isolated from Cre−, A, and AC MSCs (no Wnt3a stimulation), transcribed to complementary DNA (cDNA), and PCRs (run in triplicate) were quantified using Fast-SYBR Green. Gene expression was normalized to Gapdh and data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of 3 independent experiments. ***P < .0001, **P < .001, *P < .05. NS, not significant.

Loss of 1 copy of Ctnnb1 in an Apc-haploinsufficient microenvironment prevents or delays the development of MDS by 8 to 10 months. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for Apcdel/+ (A; n = 4), Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ (AC; n = 11), Ctnnb1del/+ (C; n = 3), and Apcfl/+, Ctnnb1fl/+ (Cre−; n = 9) recipient mice. Median survival of Apcdel/+ and Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ recipient mice was significantly different (115 vs 413 days; P < .0001). All control mice (C and Cre−) survived until the end of the study, with the exception of 1 Apcfl/+, Ctnnb1fl/+ recipient that died at 343 days, likely due to a hemorrhagic renal cyst. (B) Percentage of CD71+Ter119+ erythroid cells, Gr1+CD11b+ myeloid cells, and CD19+IgM+ B cells in spleen isolated from Cre− (∼400 days), A (70-115 days), and AC (303-413 days) recipients that eventually displayed a fatal anemia. At sacrifice, the AC cell populations were more similar to A than Cre− recipients. (C) RBC and Hb counts in all 4 cohorts over time. The development of anemia is delayed in AC recipients after 35 weeks (a point in time when all A recipients have already been sacrificed due to severe anemia). In Cre− control recipients, 2 mice developed moderate anemia at 57 weeks. However, 1 mouse had an apparent colorectal tumor, and the other had a hemorrhagic renal cyst; neither had developed MDS. (D) MSCs were isolated from Cre− (control), A, and AC littermates 2 months posttreatment with pIpC to induce Cre-mediated deletion, and before development of disease. Following in vitro Wnt3a stimulation for 6 hours, nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were isolated and immunoblotted with Ctnnb1, β-actin (cytoplasmic), and Hdac1 (nuclear) antibodies. Quantification of 3 independent experiments shows increased nuclear and cytoplasmic Ctnnb1 protein expression in Apcdel/+ MSCs that is reduced by ∼50% upon haploinsufficient loss of Ctnnb1. (E) RNA was isolated from Cre−, A, and AC MSCs (no Wnt3a stimulation), transcribed to complementary DNA (cDNA), and PCRs (run in triplicate) were quantified using Fast-SYBR Green. Gene expression was normalized to Gapdh and data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of 3 independent experiments. ***P < .0001, **P < .001, *P < .05. NS, not significant.

To demonstrate that Ctnnb1 haploinsufficiency alters Wnt signaling in the BM niche, we isolated MSCs from Cre− (control), Apcdel/+ (A), and Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ (AC) compact bones (supplemental Figure 2). Cytoplasmic and nuclear Ctnnb1 levels in Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ MSCs remained at ∼50% compared with Apcdel/+ MSCs, even after Wnt3a stimulation, suggesting that there is no compensatory upregulation of Ctnnb1 upon haploinsufficient loss of Ctnnb1 (Figure 3D). In the absence of exogenous Wnt3a, expression of the WNT targets genes, Tcf1 and Axin2, but not the Lef1 or the control Rn18s gene, was significantly lower in Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+ vs Apcdel/+ MSCs, and similar to Cre− MSCs (Figure 3E). Similar results were seen after in vitro Wnt3a stimulation of MSCs (supplemental Figure 3). The inconsistent suppression of Lef1 may be due to Ctnnb1-independent activation of this gene under some circumstances. Loss of 1 copy of Ctnnb1 in BM hematopoietic cells also suppressed WNT signaling (supplemental Figure 4); however, given the cell-extrinsic effect of Apc loss on MDS development, that is, the niche effect, these data suggest that WNT signaling in the BM microenvironment, rather than hematopoietic cells, is responsible for MDS in Apcdel/+ mice.

Treatment with pyrvinium inhibits disease in Apcdel/+ mice

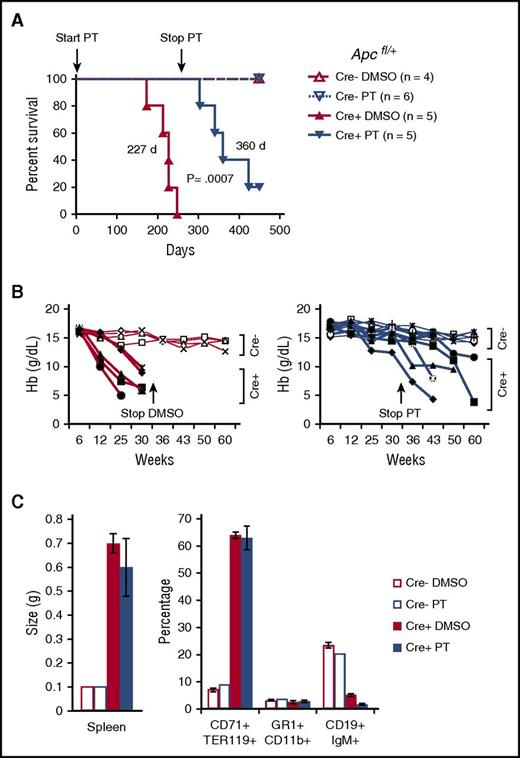

The FDA-approved antihelminth drug, pyrvinium, attenuates WNT signaling through direct binding to and activation of CK1α (or CSNK1A1).44 CK1α is a key kinase responsible for initiating the phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and subsequent proteosomal degradation of Ctnnb1. To determine whether an inhibitor of WNT signaling can prevent Apcdel/+ mice from developing disease, we injected Apcdel/+ (Cre+) or control Cre− mice 2 times per week with vehicle (DMSO) or PT at 0.1 mg/kg immediately following pIpC treatment. Apcdel/+ mice in the control DMSO group developed disease with a median survival of 227 days (Figure 4A). During this time period, none of the PT-treated Apcdel/+ became moribund and appeared as healthy as control Cre− mice. At 250 days, by which time all of the DMSO-treated mice had succumbed, drug administration was suspended, and the PT-treated group eventually succumbed to disease with a significantly longer median survival of 360 days vs 227 days for the control group (P = .007).

Pharmacological inhibition of WNT signaling using pyrvinium prevents the development of MDS in Apcdel/+ mice. (A) Mx1-Cre−Apcfl/+ (Cre−) or Mx1-Cre+Apcfl/+ (Cre+, also referred to as Apcdel/+) were injected IP for 300 days with 0.1 mg/kg PT or vehicle (DMSO) twice per week (beginning when Apc deletion was induced at 2 months of age). Kaplan-Meier survival curves of Cre− and Cre+ mice treated with PT or DMSO are shown. DMSO-treated Cre+ mice died with a median survival of 227 days. PT-treated Cre+ mice did not develop disease as long as PT was administered; however, they slowly developed a severe anemia after PT was withdrawn and survived for a median of 360 days (DMSO 227 days vs PT 360 days; P = .0007). Cre− mice, treated with PT or vehicle, survived until the end of the study indicating no major adverse effects from PT administration. (B) Hb counts from Cre− (open symbols) and Cre+ (solid black symbols) mice injected with DMSO (left) or PT (right) over time. Injections were stopped at 35 weeks, after all DMSO-treated Cre+ were sacrificed. None of the PT-treated Cre+ mice were anemic at 35 weeks (with the exception of mouse 8493, which was mildly anemic with a Hb of ∼10 g/dL). However, following cessation of PT treatment, anemia slowly developed at varying rates in all PT-treated Cre+ mice. (C) Spleen size and percentage of CD71+Ter119+ erythroid cells, Gr1+Cd11b+ myeloid cells, and CD19+IgM+ B cells in spleen isolated from DMSO-treated Cre− (450 days) or Cre+ (173-248 days) mice or PT-treated Cre− (450 days) or Cre+ (304-449 days) mice. After PT cessation, PT-treated Cre+ mice eventually developed splenomegaly with marked erythroid proliferation and effacement of B lymphoid cells, indicators of the MDS seen in the DMSO-treated Cre+ mice.

Pharmacological inhibition of WNT signaling using pyrvinium prevents the development of MDS in Apcdel/+ mice. (A) Mx1-Cre−Apcfl/+ (Cre−) or Mx1-Cre+Apcfl/+ (Cre+, also referred to as Apcdel/+) were injected IP for 300 days with 0.1 mg/kg PT or vehicle (DMSO) twice per week (beginning when Apc deletion was induced at 2 months of age). Kaplan-Meier survival curves of Cre− and Cre+ mice treated with PT or DMSO are shown. DMSO-treated Cre+ mice died with a median survival of 227 days. PT-treated Cre+ mice did not develop disease as long as PT was administered; however, they slowly developed a severe anemia after PT was withdrawn and survived for a median of 360 days (DMSO 227 days vs PT 360 days; P = .0007). Cre− mice, treated with PT or vehicle, survived until the end of the study indicating no major adverse effects from PT administration. (B) Hb counts from Cre− (open symbols) and Cre+ (solid black symbols) mice injected with DMSO (left) or PT (right) over time. Injections were stopped at 35 weeks, after all DMSO-treated Cre+ were sacrificed. None of the PT-treated Cre+ mice were anemic at 35 weeks (with the exception of mouse 8493, which was mildly anemic with a Hb of ∼10 g/dL). However, following cessation of PT treatment, anemia slowly developed at varying rates in all PT-treated Cre+ mice. (C) Spleen size and percentage of CD71+Ter119+ erythroid cells, Gr1+Cd11b+ myeloid cells, and CD19+IgM+ B cells in spleen isolated from DMSO-treated Cre− (450 days) or Cre+ (173-248 days) mice or PT-treated Cre− (450 days) or Cre+ (304-449 days) mice. After PT cessation, PT-treated Cre+ mice eventually developed splenomegaly with marked erythroid proliferation and effacement of B lymphoid cells, indicators of the MDS seen in the DMSO-treated Cre+ mice.

Hemoglobin (Hb) levels were followed during the administration of DMSO and PT. Over a 36-week period, we observed a decline in Hb levels from ∼16 g/dL to 4 g/dL in the Cre+ (Apcdel/+) DMSO-treated group. With the exception of 1 mouse, Hb levels stayed normal throughout the duration of PT treatment of the Cre+ group (Figure 4B). Following the cessation of PT treatment, all mice showed a slow decrease in Hb levels. PT-treated mice eventually developed MDS with the typical macrocytic anemia, splenomegaly, marked erythroid proliferation (increased CD71+Ter119+ erythroblasts), and effacement of splenic architecture (decreased CD19+IgM+ B cells) (Figure 4C). None of the Cre− mice showed any signs of disease, as reflected by their lengthy survival, normal levels of Hb, and normal distribution of erythroid, myeloid, and lymphoid cells, indicating that PT is well tolerated (Figure 4A-C). Thus, continuous in vivo administration of the FDA-approved antihelminth drug pyrvinium prevents the development of MDS in Apc-haploinsufficient mice.

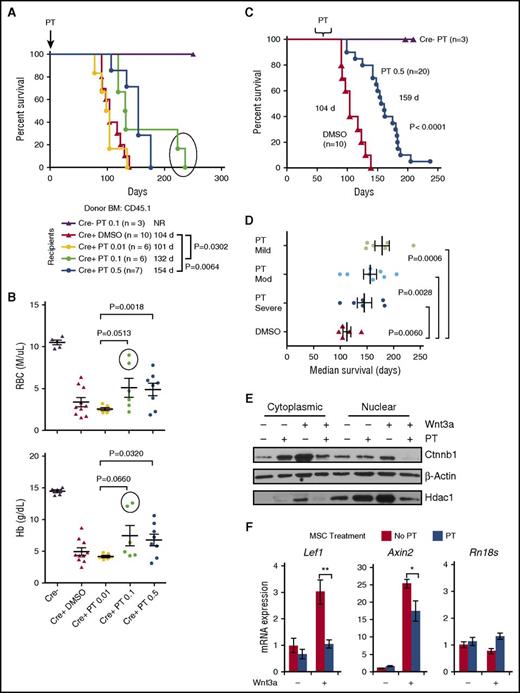

Prevention of MDS is sensitive to WNT-signaling levels in the BM microenvironment and the timing of treatment

To examine PT’s effect on the BM microenvironment, Apcdel/+ mice were treated biweekly with DMSO, 0.01, 0.1, or 0.5 mg/kg PT before and after transplantation with WT BM. Survival was similar for the DMSO and 0.01 PT cohorts (104 and 101 days); however, survival was significantly prolonged in both the 0.1 and 0.5 mg/kg PT group compared with the DMSO control (132 days vs 104 days, P = .0302 and 154 days vs 104 days, P = .0064) (Figure 5A). Analysis of red blood cell (RBC) and Hb counts at ∼100 days posttransplant revealed that the development of anemia in mice treated with 0.1 or 0.5 mg/kg PT was delayed compared with either the DMSO-treated or 0.01 mg/kg PT-treated group. There was a significant increase in RBC and Hb counts in the 0.5 mg/kg PT-treated mice compared with 0.01 mg/kg PT-treated mice (P = .0018 and P = .032, respectively) (Figure 5B) (statistical significance was not observed with the DMSO-treated group, possibly due to greater blood cell count variability). Thus, PT administered at 0.1 or 0.5 mg/mL delayed the development of MDS in Apcdel/+ recipient mice.

Pyrvinium modulation of WNT signaling is more effective before the onset of moderate-severe anemia. (A) Two-month-old Mx1-Cre−Apcfl/+ (Cre−) or Mx1-Cre+Apcfl/+ (Cre+, also referred to as Apcdel/+) recipients were treated with pIpC (to induce Apc deletion) and vehicle (DMSO) or PT 2 weeks before lethal irradiation and transplantation with WT (CD45.1) BM cells. Mice were injected twice per week with 0.01, 0.1, or 0.5 mg/kg PT or DMSO until sacrifice. Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival show that mice treated with 0.1 mg/kg or 0.5 mg/kg PT survived about 1 to 2 months longer than vehicle-treated mice (P = .0302 and P = .0064, respectively). (B) RBC and Hb counts of DMSO and PT-treated mice at ∼100 days posttransplant (for some mice in the DMSO and 0.01 mg/kg PT groups, counts from <100 days were plotted since they died before 100 days). The RBC and Hb counts of 0.5 mg/kg PT-treated mice were higher than 0.01 mg/kg PT-treated mice, indicating the administration of 0.5 mg/kg PT delays development of anemia (P = .0018 and P = .0320). The 2 mice in the 0.1 mg/kg PT-treated group that survived beyond 200 days had noticeably higher RBC and Hb counts at 100 days (circled). (C) Cre+ recipients were treated with 0.5 mg/kg PT once they developed mild (Hb, 12-13.5 g/dL), moderate (Hb, 10-11.5 g/dL), or severe anemia (Hb, <10 g/dL). A Kaplan-Meier survival curve of all PT-treated mice indicates survival is extended by almost 2 months (DMSO vs PT: 104 days vs 159 days; P < .0001). (D) The average median survival of recipients from the mild, moderate, and severe anemia group vs the DMSO-treated control group is shown. A longer survival is achieved if treatment is started before the onset of severe anemia. (E) MSCs were isolated from Apcdel/+mice ∼2 months post-pIpC-induced deletion and before development of disease. MSCs were treated with or without 50 ng/mL Wnt3a ± 50 nM PT, as indicated, for 16 hours. A representative immunoblot of nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions immunoblotted with Ctnnb1, β-actin (cytoplasmic), and Hdac1 (nuclear) is shown. In 3 independent experiments, PT treatment decreased Wnt3a-mediated elevation of Ctnnb1 by 56% ± 11.5% (P = .04). (F) Apcdel/+ MSCs were stimulated in vitro ± 50 ng/mL Wnt3a ± 50 nM PT for 16 hours. RNA was isolated and transcribed to cDNA, and PCRs (run in triplicate) were quantified using Fast-SYBR Green. Gene expression was normalized to Gapdh and data are presented as mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. **P < .001, *P < .05. NR, not reached.

Pyrvinium modulation of WNT signaling is more effective before the onset of moderate-severe anemia. (A) Two-month-old Mx1-Cre−Apcfl/+ (Cre−) or Mx1-Cre+Apcfl/+ (Cre+, also referred to as Apcdel/+) recipients were treated with pIpC (to induce Apc deletion) and vehicle (DMSO) or PT 2 weeks before lethal irradiation and transplantation with WT (CD45.1) BM cells. Mice were injected twice per week with 0.01, 0.1, or 0.5 mg/kg PT or DMSO until sacrifice. Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival show that mice treated with 0.1 mg/kg or 0.5 mg/kg PT survived about 1 to 2 months longer than vehicle-treated mice (P = .0302 and P = .0064, respectively). (B) RBC and Hb counts of DMSO and PT-treated mice at ∼100 days posttransplant (for some mice in the DMSO and 0.01 mg/kg PT groups, counts from <100 days were plotted since they died before 100 days). The RBC and Hb counts of 0.5 mg/kg PT-treated mice were higher than 0.01 mg/kg PT-treated mice, indicating the administration of 0.5 mg/kg PT delays development of anemia (P = .0018 and P = .0320). The 2 mice in the 0.1 mg/kg PT-treated group that survived beyond 200 days had noticeably higher RBC and Hb counts at 100 days (circled). (C) Cre+ recipients were treated with 0.5 mg/kg PT once they developed mild (Hb, 12-13.5 g/dL), moderate (Hb, 10-11.5 g/dL), or severe anemia (Hb, <10 g/dL). A Kaplan-Meier survival curve of all PT-treated mice indicates survival is extended by almost 2 months (DMSO vs PT: 104 days vs 159 days; P < .0001). (D) The average median survival of recipients from the mild, moderate, and severe anemia group vs the DMSO-treated control group is shown. A longer survival is achieved if treatment is started before the onset of severe anemia. (E) MSCs were isolated from Apcdel/+mice ∼2 months post-pIpC-induced deletion and before development of disease. MSCs were treated with or without 50 ng/mL Wnt3a ± 50 nM PT, as indicated, for 16 hours. A representative immunoblot of nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions immunoblotted with Ctnnb1, β-actin (cytoplasmic), and Hdac1 (nuclear) is shown. In 3 independent experiments, PT treatment decreased Wnt3a-mediated elevation of Ctnnb1 by 56% ± 11.5% (P = .04). (F) Apcdel/+ MSCs were stimulated in vitro ± 50 ng/mL Wnt3a ± 50 nM PT for 16 hours. RNA was isolated and transcribed to cDNA, and PCRs (run in triplicate) were quantified using Fast-SYBR Green. Gene expression was normalized to Gapdh and data are presented as mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. **P < .001, *P < .05. NR, not reached.

Rescuing anemia in the transplant setting, with Apcdel/+, Ctnnb1del/+, or PT-treated Apcdel/+ recipients (Figures 3A and 5A), was typically weaker compared with the genetic models (Figures 1A and 4A). It is possible that an inflammatory response caused by the radiation-based conditioning regime used for transplantation enhanced or cooperated with WNT signaling, thereby accelerating disease progression and rendering it less sensitive to WNT inhibition.

We next asked whether PT was effective in delaying the progression of disease or improving hematologic parameters in mice that had already developed anemia. We administered 0.5 mg/kg PT to Apcdel/+ recipients once they developed mild (Hb, 12-13.5 g/dL), moderate (Hb, 10-11.5 g/dL) or severe anemia (Hb, <10 g/dL). (Healthy mice typically have a Hb of 14.5-16.5 g/dL). The median duration of treatment was 69 (62-103), 67 (51-76) and 69 (57-76) days after transplantation in the 3 groups, respectively. A Kaplan-Meier survival curve revealed a longer survival of all mice treated with PT compared with DMSO (159 vs 104 days; P < .0001) (Figure 5C). Stratification of PT-treated mice based on the level of anemia they displayed when treatment was initiated is shown in Figure 5D. Compared with DMSO-treated controls, mice that received PT treatment after they developed mild, moderate, or severe anemia survived significantly longer, with a median survival of 173 days, 159 days, or 142 days, respectively (P = .0006, P = .0028, P = .0060). Thus, to extend the life of Apcdel/+ recipients, PT treatment does not have to be administered before anemia develops. However, the drug is more effective when it is started in animals that display milder anemia.

To determine whether PT dampens WNT signaling in niche cells, Apcdel/+ MSCs were treated in vitro with or without Wnt3a ± PT. Ctnnb1 levels in Apcdel/+ MSCs increase after treatment with Wnt3a. However, PT treatment decreases Wnt3a-mediated elevation of cytosolic and nuclear Ctnnb1 by 56% ± 11.6% (P = .04) (Figure 5E). In addition, PT suppressed Wnt3a-mediated transcription of the WNT targets genes, Lef1 and Axin2, but not the control gene Rn18s, threefold (P = .0008) and 1.5-fold (P = .013), respectively. (Figure 5F). In the absence of Wnt3a, the effect of PT was inconsistent.

PT may also have had some effect on hematopoietic cells. The expression of the WNT target gene, Axin2, was decreased in Cre−, but not Cre+, leukocytes that were treated for 150 days with PT compared with DMSO (supplemental Figure 5) (an effect of PT in Cre+ leukocytes may have been hampered by the early anemia in DMSO but not PT mice). The development of MDS, resulting from haploinsufficient loss of Apc in the BM niche, can be delayed by treating recipients with PT. Thus, it is most likely that PT-induced reduction of WNT signaling in the MSCs, rather than hematopoietic cells, prolongs the life of Apcdel/+ mice.

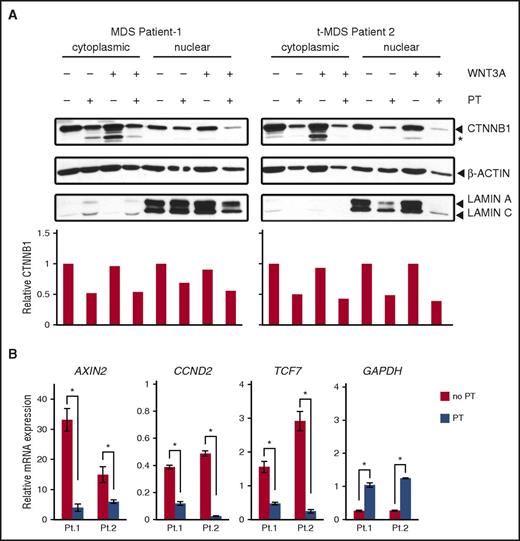

MSCs isolated from del(5q) MDS patients are sensitive to pyrvinium

To determine whether MSCs isolated from patients with MDS would be sensitive to WNT inhibition, we isolated MSCs from 2 del(5q) patients with primary MDS or therapy-related MDS (t-MDS) (supplemental Table 3). MSCs treated with PT for 16 hours showed a ∼40% to 60% reduction in cytosolic and nuclear CTNNB1 in both unstimulated and WNT3A-stimulated samples (Figure 6A). PT-suppressed WNT3A-mediated transcription of WNT target genes, AXIN2, CCND1, and TCF7, but increased the control GAPDH gene (Figure 6B). Similar results were observed in MSCs isolated from a patient with therapy-related AML without a del(5q) (supplemental Figure 6). Together with our mouse model, these studies suggest that fine-tuning aberrant WNT signaling in the BM niche may provide a therapeutic avenue in the treatment of some myeloid neoplasms.

Pyrvinium suppresses WNT activation in MSCs isolated from patients with myeloid neoplasms with a del(5q). (A) MSCs were isolated from the BM of 2 del(5q) patients with primary MDS or t-MDS and were treated in vitro with or without 50 ng/mL WNT3A ± 50 nM PT, as indicated, for 16 hours. Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were isolated and immunoblotted with antibodies specific for CTNNB1, β-actin, and Lamin A/C. Quantitation of the immunoblots revealed a ∼50% reduction in CTNNB1 levels in samples treated with PT. *A smaller CTNNB1 degradation product. (B) Patient MSCs were treated with WNT3A ± 50 nM PT for 16 hours. RNA was isolated and transcribed to cDNA, and PCRs (run in triplicate) were quantified using Fast-SYBR Green. Gene expression was normalized to the ACTB gene and data are presented as mean ± SEM of 1 patient sample, run in triplicate. PT significantly decreased WNT3A-mediated transcription of WNT target genes, but not the control GAPDH gene. *P < .05. Increased GAPDH may reflect emerging evidence suggesting that GAPDH gene expression can be modulated by external factors.58

Pyrvinium suppresses WNT activation in MSCs isolated from patients with myeloid neoplasms with a del(5q). (A) MSCs were isolated from the BM of 2 del(5q) patients with primary MDS or t-MDS and were treated in vitro with or without 50 ng/mL WNT3A ± 50 nM PT, as indicated, for 16 hours. Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were isolated and immunoblotted with antibodies specific for CTNNB1, β-actin, and Lamin A/C. Quantitation of the immunoblots revealed a ∼50% reduction in CTNNB1 levels in samples treated with PT. *A smaller CTNNB1 degradation product. (B) Patient MSCs were treated with WNT3A ± 50 nM PT for 16 hours. RNA was isolated and transcribed to cDNA, and PCRs (run in triplicate) were quantified using Fast-SYBR Green. Gene expression was normalized to the ACTB gene and data are presented as mean ± SEM of 1 patient sample, run in triplicate. PT significantly decreased WNT3A-mediated transcription of WNT target genes, but not the control GAPDH gene. *P < .05. Increased GAPDH may reflect emerging evidence suggesting that GAPDH gene expression can be modulated by external factors.58

Discussion

Traditionally, MDS has been considered to be clonal disorders of HSCs, resulting in ineffective hematopoiesis, peripheral cytopenia(s), dysplasia, and a predisposition to progress to AML. However, the etiology of MDS, including the events that lead to the initiation and progression of the disease, are only beginning to emerge. In parallel, progress in developing mouse models recapitulating the genetic abnormalities in MDS as well as improvements in murine xenograft MDS models have provided compelling evidence that the BM microenvironment participates in the pathogenesis of MDS and AML, and that an altered microenvironment may, in some instances, serve as the inciting event in hematological malignancies.

In this regard, haploinsufficient loss of Apc, or heterozygosity for the ApcMin allele in the BM niche in mice, promotes the development of MDS characterized by a severe macrocytic anemia.19-21 Because Apc is a major regulator of the WNT-signaling pathway, we sought to determine whether disease development was, in fact, mediated by aberrant WNT signaling. Using mice that were haploinsufficient for both Apc and Ctnnb1, or treating Apcdel/+ mice with a WNT inhibitor, we demonstrated that reducing Ctnnb1 levels in MSCs by ∼50% is sufficient to restore a healthy microenvironment that protects the mice from disease development.

There is growing evidence that aberrant WNT signaling in leukemia stem cells and/or the BM niche can lead to MDS/AML. CTNNB1 overexpression,34 and nuclear, nonphosphorylated CTNNB1 expression (the activated form) in the BM32 are adverse prognostic factors in AML. Gene expression profiling of hematopoietic cells also supports a role for WNT pathway activation in MDS, AML, and t-MN.19,27-30 There is also strong evidence that WNT signaling in the BM niche itself promotes myeloid malignancy. Differential WNT signaling gene expression has been observed in MSCs from MDS patients vs healthy individuals.37,38 Moreover, nuclear localization of CTNNB1 (a surrogate for activation of WNT signaling) was reported in osteoblastic cells from 38% (41 of 107) of patients with MDS or AML.23 In parallel, all mice genetically altered to express a constitutively active mutant allele of Ctnnb1 in osteoblastic cells developed AML between 2 and 3.5 weeks of age that was mechanistically linked to the expression of the Notch ligand, Jag1, and Notch activation in the leukemia cells.23

The results of our studies using transplantation of WT hematopoietic cells into mice with an Apc-haploinsufficient BM microenvironment demonstrated that aberrant WNT/Ctnnb1 signaling in the BM niche leads to MDS, with the hallmark feature of anemia. The slow development of MDS, without progression to AML in our mouse model vs the rapid development of AML in the mouse model by Kode et al,23 may be due to differences in Ctnnb1 levels, activation of downstream pathways, or the targeted niche cell type. Unlike the study with activated Ctnnb1 in osteoblasts,23 we did not see a change in expression of Notch target genes (Hes1, Hes5, Hey2) or the Hes1 target genes, Spi1 (PU.1) and Cebpa, in the LSK population in the BM (Lin−Sca1+Kit+) from healthy mice upon deletion of 1 Apc allele (supplemental Figure 7). The absence of Notch activation in HSCs may explain why the mice did not progress to AML in our mouse model of Apc haploinsufficiency.

Currently, stem cell transplantation is considered to be the only curative option for MDS, but it is associated with significant mortality and is not an appropriate approach for many elderly patients, who make up about 75% of MDS cases.53 Although hypomethylating agents and lenalidomide have improved MDS outcomes, about half of MDS patients succumb as a result of cytopenias rather than leukemic progression.54 Supportive therapy, such as RBC transfusions and erythropoietic-stimulating agents, are also not ideal, due to the high cost and problems with iron overload and resistance to erythropoietic-stimulating agent treatment that frequently arise in patients.55,56 In the United States, there have been no new drugs approved for MDS in the past 9 years; thus, novel targeted therapies are urgently needed.

The results of our studies highlight the potential of niche-targeting strategies in combination with conventional therapies as a new paradigm for therapy of MDS and AML. Herein we show that the Apcdel/+ mouse model of MDS (as induced by WNT activation in the microenvironment) and the development of MDS can be prevented by reduction of Ctnnb1 levels, or drug inhibition of the WNT/Ctnnb1-signaling pathway. Although this approach may be effective for only some forms of MDS or AML, that is, those patients with activated CTNNB1 in the BM niche, it has several advantages over the current regimens, such as reduced costs and fewer side effects. Here, we show that MSCs isolated from MDS/AML patients are sensitive to pyrvinium in response to WNT3A simulation, supporting the use of a WNT inhibitor as a novel therapeutic strategy for targeting the BM niche in some MDS/AML patients.

Although our study suggests that the drug has to be continuously administered to stave off anemia, treatment with pyrvinium has been proven to be safe in humans at doses as high as 35 mg/kg without any toxic effects.57 In addition, because aberrant WNT signaling in HSCs themselves may promote the development of AML,31,34 treating MDS patients with pyrvinium may have the added benefit of slowing or preventing the progression to AML. In summary, our studies contribute to the growing body of data implicating the BM microenvironment in the pathogenesis of hematological diseases. An integrated and comprehensive understanding of the underlying mechanisms and complex signals between the BM microenvironment and HSCs or disease-initiating cells is essential for the development of novel therapeutic strategies targeting the BM niche for hematological malignant diseases.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Megan McNerney for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by a Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute (NCI) grant (RO1 CA190372), and by a grant from the Edward P. Evans Foundation (M.M.L.B.), as well as an NIH/NCI Cancer Center support grant awarded to the University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30 CA14599).

Authorship

Contribution: A.S., J.W., C.H., A.A.F., and E.M.D. performed experiments; J.X.C. analyzed histology data; and A.S. and M.M.L.B. designed and supervised research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for C.H. is The Second Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, China.

Correspondence: Angela Stoddart, Section of Hematology/Oncology, University of Chicago, 900 E. 57th St, KCBD 7th Floor, Chicago, IL 60637; e-mail: astoddar@bsd.uchicago.edu.

References

Author notes

A.S. and J.W. contributed equally to this study.