This issue of Blood includes 2 review articles that summarize the recent revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues:

Daniel A. Arber, Attilio Orazi, Robert Hasserjian, Jürgen Thiele, Michael J. Borowitz, Michelle M. Le Beau, Clara D. Bloomfield, Mario Cazzola, and James W. Vardiman, “The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia”

Steven H. Swerdlow, Elias Campo, Stefano A. Pileri, Nancy Lee Harris, Harald Stein, Reiner Siebert, Ranjana Advani, Michele Ghielmini, Gilles A. Salles, Andrew D. Zelenetz, and Elaine S. Jaffe, “The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms”

The “blue book” monograph

The “WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues”1 is one of the “blue book” monographs published by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC; Lyon, France).

Eight years have elapsed since the current fourth edition of the monograph was published in 2008, and remarkable progress has been made in the field in this time period. Despite this, a truly new fifth edition cannot be published for the time being, as there are still other volumes pending in the fourth edition of the WHO tumor monograph series. Therefore, the Editors of the “WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues,”1 with the support of the IARC and the WHO, decided to publish an updated revision of the fourth edition that would incorporate new data from the past 8 years which have important diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic implications. Although some provisional entities have been promoted to definite entities and a few provisional entities have been added to the revised WHO classification, no new definite entities were permitted according to IARC guidelines.

A multiparameter consensus classification

As underlined by the Editors of the fourth edition of the monograph, “classification is the language of medicine: diseases must be described, defined and named before they can be diagnosed, treated and studied. A consensus on definitions and terminology is essential for both clinical practice and investigations.”2

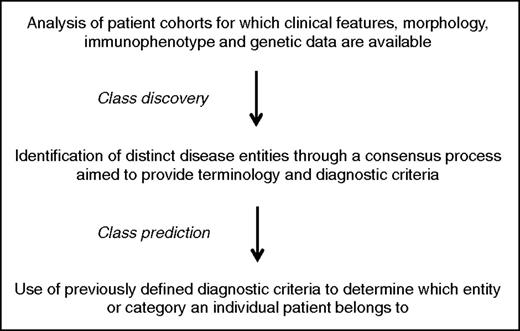

The main steps of the classification process are illustrated in Figure 1. In the introduction to the 2008 edition, Harris et al2 have clearly stated that the WHO classification is based on the principles that were adopted by the International Lymphoma Study Group for preparing the revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms (REAL classification).3 In brief, the aim was to define “real” diseases that can be reliably diagnosed using the proposed criteria.

Three aspects have characterized the WHO classification so far2 :

a multiparameter approach to define diseases has been adopted that uses all available information, that is, clinical features, morphology, immunophenotype, and genetic data;

the classification must necessarily rely on building a consensus among as many experts as possible on the definition and nomenclature of hematologic malignancies. In turn, this implies that compromise is essential in order to arrive at a consensus;

while the pathologists take the primary responsibility for developing a classification, involvement of clinicians and geneticists is crucial to ensure its usefulness and acceptance both in daily practice and in basic/clinical investigations.

The 2014 Chicago meeting

On March 31st and April 1st, 2014, 2 Clinical Advisory Committees (CAC) composed of pathologists, hematologists, oncologists, and geneticists from around the world convened in Chicago, IL, to propose revisions to the fourth edition of the classification that had been published in 2008.1 One CAC examined myeloid neoplasms; the other examined lymphoid neoplasms.

The purpose of the CAC meetings was to consider basic and clinical scientific data that had accumulated in the previous 6 years and to identify disease entities that should be modified, eliminated, or added in order to keep the classification useful for both clinical practice and clinical investigations. In preparation for the Chicago meeting, pathologists and CAC co-chairs identified proposals and issues of interest to be discussed. The meeting itself consisted of a series of proposals for modifications to the existing classification, offered by either pathologists, clinicians, or clinical scientists, followed by 1 or more short formal comments from CAC members, and then by an open discussion of the issue until consensus was achieved.

There were ongoing discussions following the CAC meetings that led to refinement of some of the provisional conclusions and to better definition of the most controversial topics.

Toward a closer integration of morphology and genetics

Facing a patient with a suspected hematologic malignancy, there is no question that morphology represents and will continue to represent a fundamental step in the diagnostic process. I belong to a school of hematology in which the hematologist is expected to personally examine the patient’s peripheral blood smear and bone marrow aspirate, and to actively discuss pathology reports. However, although being essential for the diagnostic assessment, morphology is unlikely to provide major breakthroughs in our understanding of hematologic malignancies, which are inevitably associated with advances in molecular genetics. These latter will in turn generate new diagnostic approaches, improved prognostic/predictive models, and hopefully innovative therapeutic approaches according to the principles of precision medicine.4

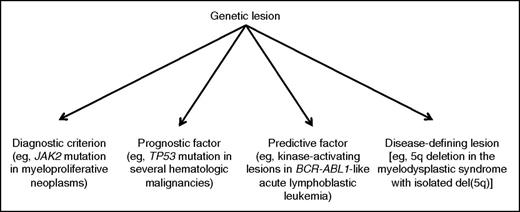

The different levels of integration of genetic data into a clinicopathological classification of hematologic malignancies are schematically represented in Figure 2. Reducing a complex subject to a scheme inevitably involves oversimplification, and the reader should therefore consider that Figure 2 is just aimed to illustrate a few fundamental concepts; in this scheme, moving from left to right means closer integration of morphology and genetics. The revised WHO classification includes remarkable examples of closer integration of genetic data into the preexisting clinicopathological classification.

Different levels of integration of genetic data into the clinicopathological classification of hematologic malignancies.

Different levels of integration of genetic data into the clinicopathological classification of hematologic malignancies.

With respect to myeloid neoplasm, Arber et al emphasize that many novel molecular findings with diagnostic and/or prognostic importance have been incorporated into the 2016 revision. These include the somatic mutations of CALR, the gene encoding calreticulin, whose detection has considerably improved our diagnostic approach to essential thrombocythemia and primary myelofibrosis, though bone marrow biopsy continues to be of fundamental importance in this process.5,6 Ad hoc studies are now needed to establish whether in myeloproliferative neoplasms, driver mutations in JAK2, CALR, or MPL should be used just as a diagnostic criterion, or may also be used as prognostic/predictive factors or eventually disease-defining genetic lesions, according to the scheme in Figure 2.

Another molecular finding with diagnostic importance that has been incorporated into the 2016 revision of myeloid neoplasms is the CSF3R mutation, which is closely associated with the rare myeloproliferative disorder known as chronic neutrophilic leukemia.7 This condition can now be more easily separated from the myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative disorder known as atypical chronic myeloid leukemia, which is preferentially associated with other mutant genes, namely SETBP1 and ETNK1.8,9 A major change to the 2016 revision of myeloid malignancies is also the addition of a section on myeloid neoplasms with germ line predisposition, including those with germ line mutation in CEBPA, DDX41, RUNX1, ANKRD26, ETV6, or GATA2.

Not always has the explosion of molecular data translated into major revisions of the WHO classification of myeloid neoplasms. For instance, this is the case with the myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), whose genetic basis is complex with several potential mutant genes.10,11 Although somatic mutations can be detected in up to 90% of patients with MDS, the same mutations can be present in elderly people with age-related clonal hematopoiesis.12 Further study is therefore required in this field to define the clinical significance of specific mutations or mutation combinations. At present, the best genotype/phenotype relationship is the association of the SF3B1 mutation with refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts.13 In the revised classification of MDS, although at least 15% ring sideroblasts are still required in cases lacking a demonstrable SF3B1 mutation, a diagnosis of refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts can be made if ring sideroblasts comprise as few as 5% of nucleated erythroid cells but an SF3B1 mutation is detected. Therefore, the SF3B1 mutation has become a novel diagnostic criterion.

With respect to acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma, 2 new provisional entities with recurrent genetic abnormalities have been incorporated into the revised classification: (1) B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia with translocations involving receptor tyrosine kinases or cytokine receptors (BCR-ABL1–like acute lymphoblastic leukemia)14,15 and (2) B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia with intrachromosomal amplification of chromosome 21 (iAMP21).16 In a recent study, BCR-ABL1–like acute lymphoblastic leukemia was found to be characterized by a limited number of activated signaling pathways that are targetable with approved tyrosine kinase inhibitors.17

In their review article on the revision of the WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms, Swerdlow et al have included in 1 table the highlights of changes, many of which derive from the explosion of new pathological and genetic data concerning the “small B-cell” lymphomas.

Hairy cell leukemia is the paradigmatic example of a major clinical impact of the identification of the genetic basis of disease. In the 2008 WHO monograph, the chapter on hairy cell leukemia reported that “no cytogenetic abnormality is specific for hairy cell leukemia.”18 The identification of the unique BRAF V600E mutation has now provided a remarkable diagnostic tool, as this genetic lesion is found in almost all patients with hairy cell leukemia.19 At the same time, the fact that it can be detected in occasional patients with splenic marginal zone lymphoma underlines the importance of a multiparameter approach to diagnosis. The identification of the unique BRAF V600E mutation also emphasizes the importance of defining the genetic basis of disease for developing innovative precision medicine strategies. In fact, 2 recent clinical trials have shown that the oral BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib is safe and effective in heavily pretreated patients with relapsed or refractory hairy cell leukemia.20

Another remarkable example of genetic lesion of diagnostic importance is the MYD88 L265P mutation,21 which is detectable in the vast majority of patients with Waldenström macroglobulinemia, possibly in all patients using sensitive approaches.22 Combined with morphology, the detection of MYD88 L265P has now become an important diagnostic criterion for lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, though the mutation is not specific for this lymphoid neoplasm.22

Similarly to what is found in the myelodysplastic syndromes, the situation is more complex with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. Although there are no recognized disease-defining mutations in this lymphoid neoplasm, molecular investigations have shown a large number of mutations that occur with a relatively low frequency. Some of these mutations, namely those in TP53, NOTCH1, and SF3B1,23,24 have adverse prognostic implications, but further study is needed before they can be integrated into an updated genetic risk profile.

Additional changes in the revised WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms include a number of provisional entities or diagnostic categories based on their molecular/cytogenetic findings, such as: large B-cell lymphoma with IRF4 rearrangement,25 predominantly diffuse follicular lymphoma with 1p36 deletion,26 Burkitt-like lymphoma with 11q aberration,27 and high-grade B-cell lymphoma with MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 rearrangements.28

The value of combining clinical, pathological, and genetic data for defining real diseases

As shown in Figure 2, one of the best examples of disease-defining genetic lesion is the 5q deletion responsible for the MDS with isolated del(5q). The process that led to defining this nosologic entity illustrates the importance of combining clinical, pathological, and genetic data.

The MDS with isolated del(5q) was first defined as a distinct hematologic disorder in 1974/1975 by Van Den Berghe, Sokal et al31,32 with a classical multiparameter approach. In fact, these investigators used a combination of clinical features (macrocytic anemia with slight leukopenia but normal or elevated platelet count), morphologic abnormalities (megakaryocytes with nonlobated and hypolobated nuclei), and cytogenetic data (acquired 5q deletion). In 2006, a clinical trial showed that lenalidomide not only corrects anemia but can also reverse the cytogenetic abnormality in this condition.33 A subsequent study showed that a portion of patients carry a subclonal TP53 mutation, and that this predicts poor response to lenalidomide and disease progression.34 More recent studies have revealed that haploinsufficiency of several genes mapping on the deleted chromosomal region represents the molecular mechanism of disease, and have in particular shown the crucial role of the CSNK1A1 gene both in the biology of the disease and its response to lenalidomide.35,36 The prognostic/predictive significance of the TP53 mutation has now been included into the revised WHO classification, and mutation analysis of TP53 is recommended to help identify an adverse prognostic subgroup in this generally favorable-prognosis MDS.

In conclusion, the current revision is a much needed and significant update of the 2008 WHO classification, and the 2 reviews being published in this issue of Blood represent the efforts of pathologists working closely with clinicians and geneticists. In the next few years, we should continue this collaboration to further improve the integration of clinical features, morphology, and genetics.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal