Key Points

Arf6 selectively regulates endocytic trafficking of platelet αIIbβ3.

Endocytosis contributes to acute platelet function.

Abstract

Platelet and megakaryocyte endocytosis is important for loading certain granule cargo (ie, fibrinogen [Fg] and vascular endothelial growth factor); however, the mechanisms of platelet endocytosis and its functional acute effects are understudied. Adenosine 5'-diphosphate–ribosylation factor 6 (Arf6) is a small guanosine triphosphate–binding protein that regulates endocytic trafficking, especially of integrins. To study platelet endocytosis, we generated platelet-specific Arf6 knockout (KO) mice. Arf6 KO platelets had less associated Fg suggesting that Arf6 affects αIIbβ3-mediated Fg uptake and/or storage. Other cargo was unaffected. To measure Fg uptake, mice were injected with biotinylated- or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–labeled Fg. Platelets from the injected Arf6 KO mice showed lower accumulation of tagged Fg, suggesting an uptake defect. Ex vivo, Arf6 KO platelets were also defective in FITC-Fg uptake and storage. Immunofluorescence analysis showed initial trafficking of FITC-Fg to a Rab4-positive compartment followed by colocalization with Rab11-positive structures, suggesting that platelets contain and use both early and recycling endosomes. Resting and activated αIIbβ3 levels, as measured by flow cytometry, were unchanged; yet, Arf6 KO platelets exhibited enhanced spreading on Fg and faster clot retraction. This was not the result of alterations in αIIbβ3 signaling, because myosin light-chain phosphorylation and Rac1/RhoA activation were unaffected. Consistent with the enhanced clot retraction and spreading, Arf6 KO mice showed no deficits in tail bleeding or FeCl3-induced carotid injury assays. Our studies present the first mouse model for defining the functions of platelet endocytosis and suggest that altered integrin trafficking may affect the efficacy of platelet function.

Introduction

It is increasingly clear that platelets are capable of different types of intracellular membrane trafficking. Platelet exocytosis and autophagy are critical for hemostasis.1-4 Platelet endocytosis is important for granule cargo loading. Platelets selectively take up certain cargo (ie, fibrinogen [Fg] and vascular endothelial growth factor) from plasma and package it into α-granules.5-8 However, the molecular mechanisms of platelet endocytosis are largely unknown. It is also unclear whether platelet endocytosis contributes to acute platelet functions beyond granule cargo loading. The goal of this study is to begin to address these fundamental questions.

The Ras-like, small guanosine triphosphate (GTP)–binding proteins called adenosine 5'-diphosphate–ribosylation factors (Arf’s), are key intracellular trafficking regulators. They cycle between inactive guanosine diphosphate (GDP)–bound and active GTP-bound states and are important for multiple functions (eg, actin cytoskeleton remodeling, lipid metabolism, and vesicle trafficking).9,10 Arf1, 3, and 6 are present in platelets.11,12 Previously, we showed that Arf6 rapidly converts from the GTP- to GDP-bound state upon platelet activation.12,13 A second wave of activation, mediated via integrin outside-in signaling, suppresses return of Arf6-GTP. Using inhibitory, membrane-permeant, myristoylated Arf6 peptides, we demonstrated that Arf6 affected human platelet adhesion and spreading.12 Arf6 also appears to play a role in the endocytosis and resensitization of P2Y receptors.14 Taken together, these data suggest that Arf6 controls endocytic trafficking in a manner that may be responsive to both initial platelet activation and subsequent signaling from contact-mediated pathways. The goal of this study was to further understand the action of Arf6 in platelets.

The integrin αIIbβ3 plays an essential role in platelet adhesion and aggregation.15,16 Also, it mediates plasma Fg endocytosis and storage into α-granules by megakaryocytes and platelets.7,17,18 Although unknown in platelets, Arf6 clearly affects integrin trafficking in other cells: both endocytosis and recycling.19-21 In cancer cells, active and inactive β1 integrins traffic via different endocytic recycling routes, although their endocytosis equally requires both clathrin and dynamin.22 Integrins can be recycled back to the plasma membrane, either via a Rab4-mediated short loop, recycling from early endosomes, or via a Rab11-mediated long loop, recycling from a perinuclear recycling compartment. These integrin recycling routes are critical for cell adhesion and for directional migration.23,24 It has been suggested that trafficking of αIIbβ3 bound to Fg could modulate platelet function.25 Based on its role in nucleated cells, we asked if Arf6 could modulate membrane trafficking and whether that was important in platelets.

To probe Arf6’s role, we generated platelet-specific Arf6 knockout (KO) mice. Deletion of Arf6 decreased Fg content by ∼50%, suggesting that Arf6 is involved in Fg uptake and/or storage by controlling αIIbβ3 trafficking. This conclusion was supported by the impaired uptake of biotinylated human Fg (biotin-Fg) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–Fg in vivo and of FITC-Fg ex vivo. The levels of other cargo were unaffected, suggesting a specific role for Arf6 in αIIbβ3/Fg trafficking. Consistent with the importance of αIIbβ3 trafficking, Arf6 KO platelets showed enhanced clot retraction and spreading on Fg, but this did not overtly increase thrombosis or hemostasis. This is the first report, using a transgenic mouse model, that αIIbβ3 trafficking is affected by Arf6 in platelets and that this regulation contributes to acute platelet functions. Furthermore, our Arf6 KO mice should prove to be invaluable in studying other endocytic trafficking processes in platelets.

Methods

Some methods are described in detail in the supplemental Materials and Methods (available on the Blood Web site).

Mouse generation and genotyping

Arf6flox/flox mice26 were crossed with PF4-promoter-driven Cre-recombinase transgenic mice (Dr Radek Skoda, University Hospital, Basel, Switzerland).27 Each animal was genotyped by polymerase chain reaction using DNA from tail biopsies. For the floxed Arf6 gene, the following primer set was used: forward primer 5′-GACCCCATGAGTGTTGTCAC-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GGGATACATAGAGAAACCTTGTCTCAGG-3′. Detection of the PF4-Cre transgene was as described.28

Flow cytometry analysis

To measure the surface levels of total and activated αIIbβ3, washed platelets (5 × 107/mL) were either kept resting or stimulated with thrombin (0.1 U/mL) for 1 minute. The reactions were stopped with hirudin (twofold excess) and incubated with FITC-anti-CD41/61 antibody and phycoerythrin-Jon/A antibody. The mixture was analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) as described.2

To measure FITC-Fg binding, platelets (5.0 × 108/mL) were incubated, on ice, with 0.06 or 0.12 mg/mL FITC-Fg for 20 minutes. Platelets were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and analyzed by FACS. The difference of geometric mean fluorescence intensity (GMFI) before and after trypan blue addition was used to assess surface Fg binding (0.04% trypan blue quenched >95% of free FITC-Fg fluorescence; supplemental Figure 1).29

To study FITC-Fg endocytosis at early time points, washed platelets (1.0 × 109/mL) were incubated with FITC-Fg (0.15 mg/mL) at 37°C for the indicated times. The platelets were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and analyzed by FACS after addition of trypan blue.

To study the effect of myr-Arf peptides12,13 on FITC-Fg endocytosis by human platelets, washed platelets (5.0 × 108/mL) were pretreated with peptides for 5 minutes and then incubated with FITC-Fg (0.05 mg/mL) for the indicated times. Platelets were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and GMFI after trypan blue (1%) addition was used to assess the endocytosis of FITC-Fg.

Static platelet adhesion and platelet spreading

Platelet adhesion and spreading were performed as described by Ye et al2 and detailed in the supplemental Materials and Methods. Briefly, for platelet adhesion, calcein labeled platelets were seeded onto Fg- or bovine serum albumin (BSA)–coated plates for 30 minutes at 37°C. Adherent platelets were quantified with a fluorescence plate reader. For platelet spreading, platelets were incubated on different surfaces at 37°C for increasing times. The adherent platelets were fixed, imaged using differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy, and their areas were measured using Image J (v1.47; National Institutes of Health).

Clot retraction

Washed platelets (3 × 108/mL) in N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N'-2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) Tyrode buffer (pH 7.4) with human Fg (0.5 mg/mL; Sigma) and 1 mM CaCl2 were incubated in cuvettes with thrombin (0.1 U/mL), and images were taken at increasing times. Clot sizes were measured using Image J software (v1.47; National Institutes of Health), and the percentage of clot size relative to initial suspension volume was determined.

Biotin-Fg or FITC-Fg uptake in vivo

Biotin-Fg was prepared following manufacturer’s instructions using EZ-LinkTM sulfo-NHS-Biotinylation Kit (Thermo Scientific). Mice were injected with the indicated amounts of modified Fg via retro-orbital sinus and, after 24 hours, were euthanized. To study the uptake of biotin-Fg, platelets were harvested for analysis by western blotting. To study the in vivo uptake of FITC-Fg, platelets and bone marrow cells were harvested. Platelets were fixed directly with 2% paraformaldehyde at room temperature. In contrast, bone marrow cells were first stained with vioblue-conjugated anti-CD41 antibody, and then fixed. Cells were viewed using a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope, and images were taken with an AxioCam MR camera (Zeiss, Germany) and processed using Zen 2011 Digital Imaging software (Zeiss).

FITC-Fg uptake ex vivo

Washed platelets (5 × 108/mL) were incubated with FITC-Fg (0.05 mg/mL) for 1 hour at 37°C. Platelets were recovered and resuspended in platelet poor plasma or HEPES Tyrode buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.35% BSA and 1 mM CaCl2 and then incubated for 2 hours at 37°C and fixed. Platelets were mixed with trypan blue (0.1%), prior to imaging. The number of FITC-positive puncta per platelet was counted.

Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy

Washed platelets (5 × 108/mL) were incubated with or without FITC-Fg (0.05 mg/mL) for the indicated times and fixed at room temperature. Platelets were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then allowed to adhere to a poly-d-lysine (0.1 mg/mL)–coated surface. Platelets were washed once with PBS, reduced with 0.1% NaBH4 for 10 minutes at room temperature, washed again 3 × 5 minutes with PBS, and then permeabilized for 15 minutes with 0.2% Triton X-100/PBS. After blocking (10% fetal bovine serum [FBS] and 0.05% Triton X-100 in PBS) for >90 minutes at room temperature, platelets were incubated with primary antibody prepared with 5% FBS and 0.05% Triton X-100 in PBS. The platelets were washed 5 × 15 minutes with wash buffer (1% FBS and 0.05% Triton X-100 in PBS) and incubated with secondary antibody in PBS in the presence of 5% FBS and 0.05% Triton X-100 for 1 hour at room temperature. Finally platelets were washed 5 × 15 minutes with wash buffer, once in PBS, and postfixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes. After washing in PBS, coverslips were mounted with VECTASHIELD mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Cells were imaged with a Nikon A1R confocal microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) with an Apo TIRF 60X/1.49 NA DIC N2 oil objective and A1 camera. Images were processed using NIS-Elements AR 3.2 software (Nikon) and Photoshop CS5 (Adobe, San Jose, CA). Digital zooms were either ×15 or ×30.

Results

Arf6 KO platelets were defective for Fg storage

Platelet-specific Arf6 KO mice were generated by crossing Arf6flox/flox mice26 with PF4-Cre mice.27 Compared with their littermates, Arf6 KO mice had similar platelet counts but slightly decreased platelet size (∼5% decrease; supplemental Table 1). By western blotting, Arf6 was reduced by ∼95% (Figure 1). Other proteins remained unchanged (Figure 1A), including the following: Arf1/3, Rho family members (Rac1, Cdc42, and RhoA), granule membrane markers (P-selectin and VMAT2, α– and dense granules, respectively), and core secretory machinery (VAMP8, Syntaxin 11, SNAP23, and VAMP3). Arf6 KO platelets had no defects in aggregation or adenosine triphosphate release in response to different agonists (supplemental Figure 2A) and had no gross, morphologic abnormalities (supplemental Figures 2B and 3). To determine whether Arf6 KO mice had thrombosis or hemostasis defects, tail bleeding and FeCl3-induced carotid artery injury assays were performed. In supplemental Figure 2C-D, Arf6 KO mice showed no overt bleeding diathesis.

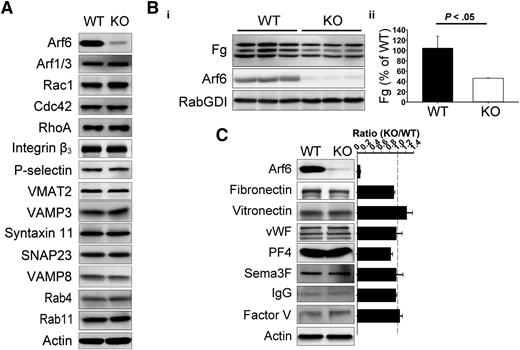

Arf6 KO platelets are defective in Fg storage but not in other cargo. (A) Comparison of proteins levels by western blotting between wild-type (WT) and KO platelets. Washed platelet extracts (1 × 107/lane) were loaded, and the indicated proteins were probed for by western blotting using the corresponding antibodies. β-Actin was used as a loading control. The data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments. (B) Comparison of endogenous Fg levels between WT and KO platelets. (i) Washed platelet extracts (1 × 107/lane) were loaded, and the indicated proteins were probed for by western blotting using corresponding antibodies. Each lane represents platelets from a single mouse. RabGDI was used as a loading control. (ii) Quantification of Fg levels in panel Bi was performed using ImageQuantTL and analyzed by SigmaPlot 12.0. (C) Comparison of granule cargo levels between WT and KO platelets. Washed platelet extracts (1 × 107/lane) were loaded, and the indicated proteins were probed for by western blotting using corresponding antibodies. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Quantification was performed using ImageQuantTL, and ratio of KO to WT was calculated. The dash line represents ratio of 1 (KO/WT). The data are representative of at least 2 independent experiments.

Arf6 KO platelets are defective in Fg storage but not in other cargo. (A) Comparison of proteins levels by western blotting between wild-type (WT) and KO platelets. Washed platelet extracts (1 × 107/lane) were loaded, and the indicated proteins were probed for by western blotting using the corresponding antibodies. β-Actin was used as a loading control. The data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments. (B) Comparison of endogenous Fg levels between WT and KO platelets. (i) Washed platelet extracts (1 × 107/lane) were loaded, and the indicated proteins were probed for by western blotting using corresponding antibodies. Each lane represents platelets from a single mouse. RabGDI was used as a loading control. (ii) Quantification of Fg levels in panel Bi was performed using ImageQuantTL and analyzed by SigmaPlot 12.0. (C) Comparison of granule cargo levels between WT and KO platelets. Washed platelet extracts (1 × 107/lane) were loaded, and the indicated proteins were probed for by western blotting using corresponding antibodies. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Quantification was performed using ImageQuantTL, and ratio of KO to WT was calculated. The dash line represents ratio of 1 (KO/WT). The data are representative of at least 2 independent experiments.

Given the importance of Arf6 in endocytic trafficking, we sought to determine if Arf6 KO platelets showed any defect in granule content. We paid specific attention to Fg because it is taken up by platelets via an αIIbβ3-mediated endocytosis process.5 In Figure 1B, endogenous Fg levels were reduced by ∼50% in each of the Arf6 KO platelet samples tested. This defect was not because of alterations in plasma Fg levels (supplemental Figure 4). Other cargo, derived either from plasma (eg, immunoglobulin G [IgG]) or from de novo synthesis (eg, platelet factor 4), were not reduced in Arf6 KO platelets (Figure 1C). Of note, there was no defect in vitronectin (binds αVβ3) or fibronectin (binds α5β1 and αvβ3) level, suggesting that the endocytosis defect is greater for αIIbβ3/Fg. These data suggest that Arf6 plays an important role in either Fg uptake, storage, or both.

Arf6 KO platelets displayed normal surface αIIbβ3 levels and normal Fg binding

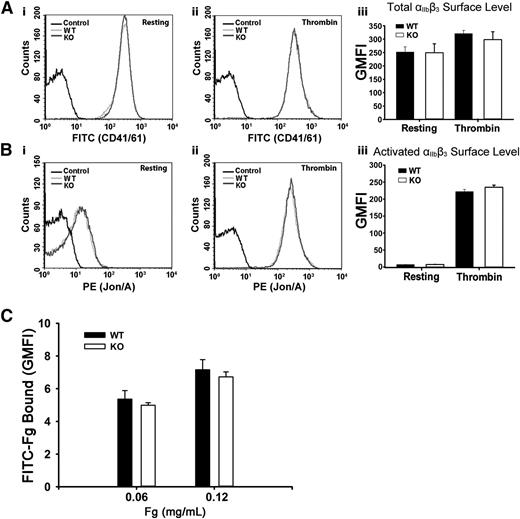

To address the possibility that the defective Fg storage was because of decreased surface αIIbβ3, levels of total and activated αIIbβ3 were measured. In Figure 2A-B, αIIbβ3 levels, whether total or activated, were unaffected in resting or in thrombin-stimulated Arf6 KO platelets as measured by FACS. These data are consistent with the aggregation results in supplemental Figure 2A. Thrombin stimulation did significantly increase total surface αIIbβ3, suggesting that a fraction (∼20%) resides in an internal compartment. The possibility that defective Fg storage was caused by defective Fg binding to Arf6 KO platelets was also tested by FACS. In Figure 2C, Arf6 KO platelets have comparable binding capacity for FITC-Fg in both concentrations tested. These data suggest that defective Fg uptake/storage in Arf6 KO platelets is not the result of either defective binding ability or decreased surface levels of αIIbβ3.

Arf6 deletion does not alter the surface levels of total or activated integrin αIIbβ3 or the binding of Fg to platelets. (A) Comparison of surface levels of total integrin αIIbβ3 between WT (light gray) and KO (dark gray) platelets. Using FITC-anti-CD41/61 antibody, levels of total integrin αIIbβ3 were measured by flow cytometry, in resting (i) and thrombin-stimulated (0.1 U/mL; ii) platelets. Unlabeled platelets (black) were used as the background control. (iii) Quantification of flow cytometry data in panels Ai and Aii expressed as GMFI. The data shown are representative of at least 2 independent experiments with triplicates. (B) Comparison of surface levels of activated integrin αIIbβ3 between WT (light gray) and KO (dark gray) platelets. Using phycoerythrin (PE)–Jon/A antibody, levels of activated integrin αIIbβ3 were measured by flow cytometry, in resting (i) and thrombin-stimulated (0.1 U/mL; ii) platelets. Unlabeled platelets (black) were used as the background control. (iii) Quantification of flow cytometry data in panels Bi and Bii expressed as GMFI. Data shown are representative of at least 2 independent experiments with triplicates. (C) Comparison of Fg binding to platelet surface between WT and KO platelets. Washed platelets (5.0 × 108/mL) were incubated, on ice, with FITC-Fg at different concentrations for 20 minutes and then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. Platelets were analyzed by flow cytometry, and quantification is shown as GMFI. The data shown are representative of 2 independent experiments with triplicates.

Arf6 deletion does not alter the surface levels of total or activated integrin αIIbβ3 or the binding of Fg to platelets. (A) Comparison of surface levels of total integrin αIIbβ3 between WT (light gray) and KO (dark gray) platelets. Using FITC-anti-CD41/61 antibody, levels of total integrin αIIbβ3 were measured by flow cytometry, in resting (i) and thrombin-stimulated (0.1 U/mL; ii) platelets. Unlabeled platelets (black) were used as the background control. (iii) Quantification of flow cytometry data in panels Ai and Aii expressed as GMFI. The data shown are representative of at least 2 independent experiments with triplicates. (B) Comparison of surface levels of activated integrin αIIbβ3 between WT (light gray) and KO (dark gray) platelets. Using phycoerythrin (PE)–Jon/A antibody, levels of activated integrin αIIbβ3 were measured by flow cytometry, in resting (i) and thrombin-stimulated (0.1 U/mL; ii) platelets. Unlabeled platelets (black) were used as the background control. (iii) Quantification of flow cytometry data in panels Bi and Bii expressed as GMFI. Data shown are representative of at least 2 independent experiments with triplicates. (C) Comparison of Fg binding to platelet surface between WT and KO platelets. Washed platelets (5.0 × 108/mL) were incubated, on ice, with FITC-Fg at different concentrations for 20 minutes and then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. Platelets were analyzed by flow cytometry, and quantification is shown as GMFI. The data shown are representative of 2 independent experiments with triplicates.

Arf6 KO platelets were defective in Fg uptake in vivo and ex vivo

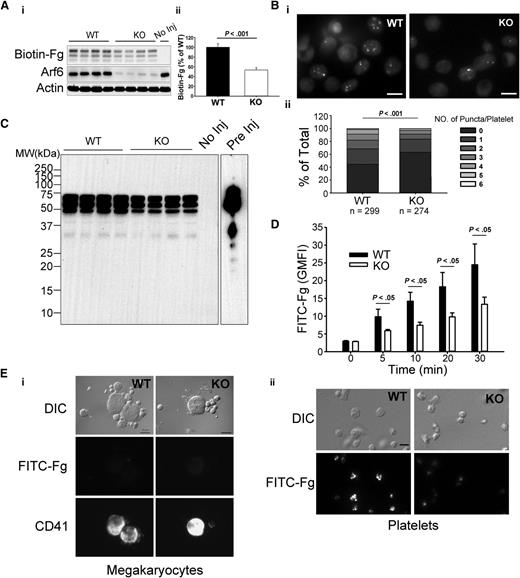

Fg uptake is seen in both megakaryocytes and platelets.5 To determine if Arf6 plays a role in platelet Fg uptake, we examined uptake of biotin-Fg and FITC-Fg. For in vivo assays, biotin-Fg was injected via the retro-orbital sinus, and platelets were harvested 24 hours postinjection. The platelet-associated biotin-Fg was analyzed by western blotting. In Figure 3A, Arf6 KO platelets retained significantly less biotin-Fg compared with WT. Ex vivo, washed platelets were incubated with FITC-Fg and fixed for imaging in the presence of trypan blue. In Figure 3Bi, Arf6 KO platelets had a lower, trypan blue-resistant, internal pool of FITC-Fg compared with WT platelets. Quantitatively, using FITC-labeled puncta number per platelet as a metric, KO platelets had a higher percentage of cells with fewer puncta (Figure 3Bii). This deficit was also detectible by flow cytometry at the earliest time point (5 minutes; Figure 3D). These data suggest that Arf6 deletion could affect intraplatelet trafficking of endocytosed Fg by redirecting it away from its normal storage site (ie, α-granules).

Arf6 KO platelets are defective in Fg uptake in vivo and ex vivo. (A) Arf6 deletion impairs platelet uptake of Fg in vivo. (i) WT and KO mice were injected with biotin-Fg via the retro-orbital sinus. Platelets were harvested 24 hours postinjection. Platelet extracts (1 × 107/lane) were loaded, and the indicated proteins were probed for by western blotting using corresponding antibodies. Each lane represents platelets from a single mouse. A mouse without injection (No Inj) was included as a negative control. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (ii) Quantification of biotin-Fg levels in panel Ai was performed using ImageQuantTL and analyzed by SigmaPlot 12.0. (B) Arf6 deletion impairs Fg uptake by platelets ex vivo. (i) Washed platelets (5 × 108/mL) from WT and KO mice were incubated with FITC-Fg (0.05 mg/mL) for 1 hour at 37°C. After removing the extracellular FITC-Fg, platelets were incubated with HEPES Tyrode buffer (pH = 7.4) for another 2 hours. Platelets were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C and subjected to epifluorescence microscopy. The extracellular signal was quenched with 0.1% trypan blue, and representative images, from 4 experiments, are presented. (ii) The number of FITC-positive puncta per platelet was manually counted, and platelets were grouped according to that number. The percentage platelets in each group relative to total was calculated and plotted as a bar graph. Statistical significance was determined using rank sum test. (C) Overexposure of biotin blot in panel Ai, to probe for fragments of biotin-Fg. Starting biotin-Fg (Pre Inj) was included as a comparison. (D) Arf6 deletion impedes uptake of FITC-Fg ex vivo. Washed platelets (1.0 × 109/mL) from 3 WT (black) and 3 KO (open) mice were separately incubated with FITC-Fg (0.15 mg/mL) at 37°C for the indicated times and then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. Intracellular FITC-Fg levels were measured by flow cytometry, after addition of trypan blue, and expressed as GMFI (mean ± standard deviation). Statistical significance was determined by Student t test. (E) Megakaryocyte uptake of FITC-Fg is below detection under the conditions used. WT and KO mice were injected with FITC-Fg (0.75 mg/mouse) via the retro-orbital sinus. Each group included 2 mice. Bone marrow cells and platelets were harvested 24 hours postinjection and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde. DIC images and fluorescence images are presented. Megakaryocytes were identified by CD41 staining. (i) The exposure time for FITC-Fg and CD41 images is 2 seconds and 0.5 seconds, respectively. The scale bar is 10 µm. (ii) The exposure time for FITC-Fg is 1 second. The scale bar represents 5 µm. Representative images were selected from >10 different fields of each group.

Arf6 KO platelets are defective in Fg uptake in vivo and ex vivo. (A) Arf6 deletion impairs platelet uptake of Fg in vivo. (i) WT and KO mice were injected with biotin-Fg via the retro-orbital sinus. Platelets were harvested 24 hours postinjection. Platelet extracts (1 × 107/lane) were loaded, and the indicated proteins were probed for by western blotting using corresponding antibodies. Each lane represents platelets from a single mouse. A mouse without injection (No Inj) was included as a negative control. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (ii) Quantification of biotin-Fg levels in panel Ai was performed using ImageQuantTL and analyzed by SigmaPlot 12.0. (B) Arf6 deletion impairs Fg uptake by platelets ex vivo. (i) Washed platelets (5 × 108/mL) from WT and KO mice were incubated with FITC-Fg (0.05 mg/mL) for 1 hour at 37°C. After removing the extracellular FITC-Fg, platelets were incubated with HEPES Tyrode buffer (pH = 7.4) for another 2 hours. Platelets were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C and subjected to epifluorescence microscopy. The extracellular signal was quenched with 0.1% trypan blue, and representative images, from 4 experiments, are presented. (ii) The number of FITC-positive puncta per platelet was manually counted, and platelets were grouped according to that number. The percentage platelets in each group relative to total was calculated and plotted as a bar graph. Statistical significance was determined using rank sum test. (C) Overexposure of biotin blot in panel Ai, to probe for fragments of biotin-Fg. Starting biotin-Fg (Pre Inj) was included as a comparison. (D) Arf6 deletion impedes uptake of FITC-Fg ex vivo. Washed platelets (1.0 × 109/mL) from 3 WT (black) and 3 KO (open) mice were separately incubated with FITC-Fg (0.15 mg/mL) at 37°C for the indicated times and then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. Intracellular FITC-Fg levels were measured by flow cytometry, after addition of trypan blue, and expressed as GMFI (mean ± standard deviation). Statistical significance was determined by Student t test. (E) Megakaryocyte uptake of FITC-Fg is below detection under the conditions used. WT and KO mice were injected with FITC-Fg (0.75 mg/mouse) via the retro-orbital sinus. Each group included 2 mice. Bone marrow cells and platelets were harvested 24 hours postinjection and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde. DIC images and fluorescence images are presented. Megakaryocytes were identified by CD41 staining. (i) The exposure time for FITC-Fg and CD41 images is 2 seconds and 0.5 seconds, respectively. The scale bar is 10 µm. (ii) The exposure time for FITC-Fg is 1 second. The scale bar represents 5 µm. Representative images were selected from >10 different fields of each group.

To determine if uptake of Fg by megakaryocytes contributes to the storage deficit of Fg in platelets in vivo, WT and KO mice were injected with FITC-Fg, via retro-orbital sinus, and bone marrow cells and platelets were harvested 24 hours postinjection. Megakaryocytes were identified by anti-CD41 staining. In Figure 3E, FITC-Fg was undetectable in megakaryocytes from either WT or KO mice, whereas FITC-Fg was readily detected in WT platelets but was lower in KO platelets. In Figure 3E, the exposure times for FITC-Fg were twice as long for megakaryocytes as for platelets. This result suggests that, under our experimental conditions, FITC-Fg uptake by platelets is more effective than by megakaryocytes. It should be noted that the injected FITC-Fg was probably taken up by circulating platelets before gaining access to the bone marrow cells.

Endocytosed Fg can be routed through multivesicular bodies (MVBs) before being stored in α-granules.30 MVBs are also considered an intermediate stage for lysosomal degradation.31 To exclude the possibility that decreased Fg storage was because of enhanced degradation, we tried to detect fragments of biotin-Fg in samples from the in vivo uptake assay. Despite overexposing the images, fragments of biotin-Fg were not detectable in either WT or KO platelets (Figure 3C). Although the lack of fragments is a negative result, it is consistent with endocytosed biotin-Fg not being degraded in platelets lacking Arf6. Taken together, these data suggest that Arf6 is required for proper Fg storage in platelets.

Spreading on Fg was enhanced by Arf6 deletion

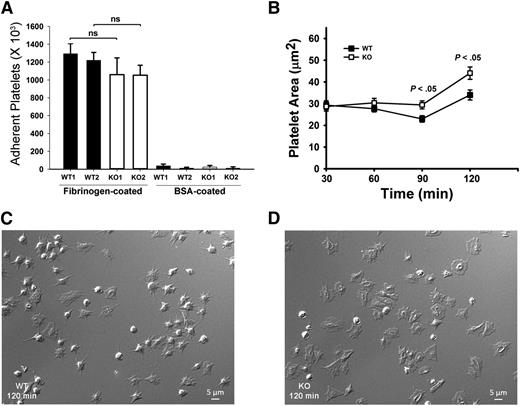

Because αIIbβ3 is the major receptor for Fg uptake and storage,7 defective Fg storage in Arf6 KO platelets implies defective endocytic trafficking of αIIbβ3. We sought to determine if this altered trafficking affects other platelet activities, aside from granule loading. Examples of how this could occur include the following: Inhibition of β1 integrin trafficking by Arf6 deletion in HeLa cells inhibits cell spreading on fibronectin.32 Alternatively, in neurons, Arf6 inactivation increases recycling of α9β1 through a Rab4-mediated pathway and increases axonal growth.19 To investigate roles for Arf6 in αIIbβ3-mediated spreading, we performed time-course studies of platelet spreading on Fg-coated surfaces. Surprisingly, Arf6 KO platelets spread faster compared with WT without affecting initial static adhesion (Figure 4). Arf6 KO platelets had larger surface areas as early as 60 minutes (Figure 4B). At 90 and 120 minutes, Arf6 KO platelets were significantly larger than WT (Figure 4B-D).

Arf6 KO platelets have enhanced spreading but normal static adhesion. (A) Quantification of static platelet adhesion on Fg- and BSA-coated surface. Washed calcein-labeled platelets (2.5 × 108/mL) from WT and KO mouse were incubated on Fg- or BSA-coated surfaces for 30 minutes at 37°C. The number of adherent platelets was measured using a plate reader with excitation/emission at 485/538 nm, and referenced to a standard curve. Each bar represents platelets from a single mouse. Statistical analysis was performed using Student t test. (B) Quantification of platelet surface area when spread on Fg-coated surfaces. Washed platelets from WT and KO mice (2.0 × 107/mL) were supplemented with 1 mM Ca2+ and then incubated on Fg-coated surfaces for the indicated times. They were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and DIC images were taken using Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope (Nikon) with a 100X/1.40 NA, DIC H oil objective lens (Nikon) with a Zeiss camera (AxioCam MR). Images were processed with Zen 2011 (blue edition; Zeiss) and quantified by Image J (v1.47; National Institutes of Health). (C-D) Representative DIC images of WT (C) and KO (D) platelets spread at the 120 minutes point. The data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

Arf6 KO platelets have enhanced spreading but normal static adhesion. (A) Quantification of static platelet adhesion on Fg- and BSA-coated surface. Washed calcein-labeled platelets (2.5 × 108/mL) from WT and KO mouse were incubated on Fg- or BSA-coated surfaces for 30 minutes at 37°C. The number of adherent platelets was measured using a plate reader with excitation/emission at 485/538 nm, and referenced to a standard curve. Each bar represents platelets from a single mouse. Statistical analysis was performed using Student t test. (B) Quantification of platelet surface area when spread on Fg-coated surfaces. Washed platelets from WT and KO mice (2.0 × 107/mL) were supplemented with 1 mM Ca2+ and then incubated on Fg-coated surfaces for the indicated times. They were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and DIC images were taken using Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope (Nikon) with a 100X/1.40 NA, DIC H oil objective lens (Nikon) with a Zeiss camera (AxioCam MR). Images were processed with Zen 2011 (blue edition; Zeiss) and quantified by Image J (v1.47; National Institutes of Health). (C-D) Representative DIC images of WT (C) and KO (D) platelets spread at the 120 minutes point. The data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

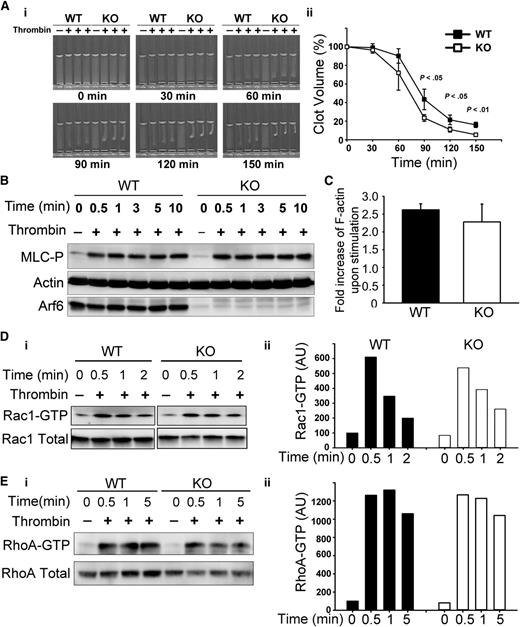

Arf6 deletion affected platelet clot retraction

Given the enhanced spreading, we asked if other aspects of αIIbβ3 function, such as clot retraction were affected. Consistently, Arf6 KO platelets had enhanced clot retraction (Figure 5A). Fg was added exogenously and thus is not limiting. The increased clot retraction supports the contention that loss of Arf6 affects the efficacy of αIIbβ3 engagement with substrate. Because downstream signaling by αIIbβ3 plays an important role in clot retraction,33,34 tyrosine phosphorylation profiles (supplemental Figure 5), myosin light-chain phosphorylation (Figure 5B), F-actin formation (Figure 5C), and Rac1/RhoA activation (Figure 5D-E) were examined. Surprisingly, there were no overt differences detected between WT and KO. These data lessen the possibility that the enhanced clot retraction and spreading phenotypes are because of some effects on the signaling steps that are associated with αIIbβ3.

Arf6 KO platelets have enhanced platelet clot retraction without noticeable defect on myosin light-chain phosphorylation (MLC-P), actin polymerization, or Rac1/RhoA activation. (A) Washed platelets from WT and KO mice (3 × 108/mL) were supplemented with 0.5 mg/mL human Fg and 1 mM Ca2+. Clot retraction was initiated with thrombin (0.1 U/mL), and images were taken at the indicated times (i) and quantified (ii). Clot size in panel A was measured using Image J v1.48 and normalized to clot size at time 0 (clot volume %). The data are representative of at least 5 independent experiments. (B) KO mice showed no defect in MLC-P upon thrombin stimulation. Washed platelets from WT and KO mice were prepared at 4 × 108/mL in HEPES Tyrode buffer (pH 7.4) and kept resting or stimulated with thrombin (0.1 U/mL) for the indicated times. The reaction was stopped by addition of sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer containing both protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails. The lysates were probed for MLC-P by western blotting. β-Actin was used as a loading control. The blots shown are representative of at least 3 independent experiments. (C) Arf6 deletion did not affect thrombin-induced F-actin formation. Resting and thrombin-stimulated platelets (2 × 107) were fixed and permeabilized with Triton X-100 in the presence of tetramethylrhodamine (TRITC)-phalloidin. The bound TRITC-phalloidin was solubilized and measured using a microplate spectrofluorimeter. The data are representative of 2 independent experiments. (D-E) KO platelets showed no defect in Rac1/RhoA activation. Washed platelets (5 × 108/mL) from WT and KO mice were kept resting or stimulated with thrombin (0.1 U/mL) for the indicated times. The reactions were stopped by addition of 2× GTPases-pulldown lysis buffer containing a protease inhibitor cocktail. Rac1-GTP/RhoA-GTP were recovered as described in “Methods.” (Di and Ei) Western blotting of the pellets (Rac1-GTP or RhoA-GTP) and the supernatant (total Rac1 or total RhoA). (Dii and Eii) Quantification of Rac1-GTP/total Rac1 and RhoA-GTP/total RhoA. Quantification was performed using ImageQuantTL, and the ratio of Rac1-GTP/total Rac1 or RhoA-GTP/total RhoA was plotted in a bar graph. Blots shown are representative of at least 2 independent experiments.

Arf6 KO platelets have enhanced platelet clot retraction without noticeable defect on myosin light-chain phosphorylation (MLC-P), actin polymerization, or Rac1/RhoA activation. (A) Washed platelets from WT and KO mice (3 × 108/mL) were supplemented with 0.5 mg/mL human Fg and 1 mM Ca2+. Clot retraction was initiated with thrombin (0.1 U/mL), and images were taken at the indicated times (i) and quantified (ii). Clot size in panel A was measured using Image J v1.48 and normalized to clot size at time 0 (clot volume %). The data are representative of at least 5 independent experiments. (B) KO mice showed no defect in MLC-P upon thrombin stimulation. Washed platelets from WT and KO mice were prepared at 4 × 108/mL in HEPES Tyrode buffer (pH 7.4) and kept resting or stimulated with thrombin (0.1 U/mL) for the indicated times. The reaction was stopped by addition of sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer containing both protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails. The lysates were probed for MLC-P by western blotting. β-Actin was used as a loading control. The blots shown are representative of at least 3 independent experiments. (C) Arf6 deletion did not affect thrombin-induced F-actin formation. Resting and thrombin-stimulated platelets (2 × 107) were fixed and permeabilized with Triton X-100 in the presence of tetramethylrhodamine (TRITC)-phalloidin. The bound TRITC-phalloidin was solubilized and measured using a microplate spectrofluorimeter. The data are representative of 2 independent experiments. (D-E) KO platelets showed no defect in Rac1/RhoA activation. Washed platelets (5 × 108/mL) from WT and KO mice were kept resting or stimulated with thrombin (0.1 U/mL) for the indicated times. The reactions were stopped by addition of 2× GTPases-pulldown lysis buffer containing a protease inhibitor cocktail. Rac1-GTP/RhoA-GTP were recovered as described in “Methods.” (Di and Ei) Western blotting of the pellets (Rac1-GTP or RhoA-GTP) and the supernatant (total Rac1 or total RhoA). (Dii and Eii) Quantification of Rac1-GTP/total Rac1 and RhoA-GTP/total RhoA. Quantification was performed using ImageQuantTL, and the ratio of Rac1-GTP/total Rac1 or RhoA-GTP/total RhoA was plotted in a bar graph. Blots shown are representative of at least 2 independent experiments.

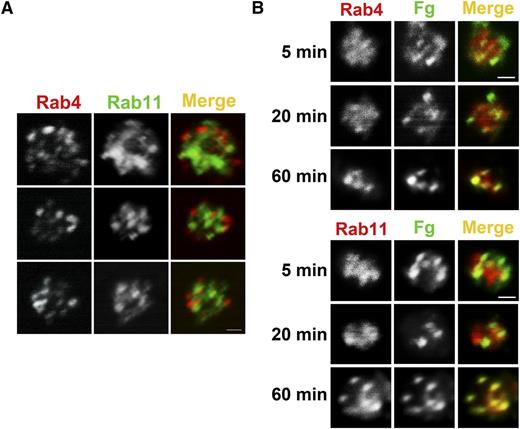

Intraplatelet trafficking of FITC-Fg

Previous work showed that Fg is taken up and trafficked to MVBs and granules.30 Other studies showed that trafficking of integrins in nucleated cells involves a Rab4-mediated fast route and a Rab11-mediated slow route.22,24,35 Rab4 and Rab11 are both present in platelets, and their levels were unaffected by Arf6 deletion (Figure 1A). Immunofluorescence analysis showed that Rab4+ and Rab11+ compartments were present but did not overlap, indicating that resting platelets contained both early and recycling endosomes (Figure 6A). To monitor Fg trafficking, WT platelets were incubated with FITC-Fg for increasing times, fixed, and immunostained with anti-Rab4 (early endosomes) or anti-Rab11 (recycling endosomes) antibodies (Figure 6B). At the initial time points, FITC-Fg colocalized more obviously with Rab4, but over time, it also colocalized with Rab11. This progression suggests a transit of endocytosed cargo from early to recycling endosomes. Because of the lower number of FITC-Fg+ platelets, we were unable to successfully evaluate Fg trafficking in Arf6 KO platelets. In the few platelets examined, there was a delay in progression to the Rab11+ compartment, but this will require more analysis to confirm (data not shown).

FITC-Fg transits through Rab4- and Rab11-positive compartments after internalization. (A) Rab4- and Rab11-containing compartments are present in human platelets. Washed human platelets (5 × 108/mL) were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, washed, and allowed to adhere to poly-d-lysine–coated coverslips. Immunofluorescence staining was done as described in “Methods.” Platelets were incubated with anti-Rab4 mouse monoclonal antibody and anti-Rab11 rabbit polyclonal antibody, and then with Alexa 568 conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG or Alexa 488 conjugated anti-rabbit IgG, respectively. Images were taken with a Nikon A1R confocal microscope (60X/1.49 NA DIC N2 oil) and digitally magnified ×30. Scale bar represents 1 µm. (B) Internalized FITC-Fg goes through Rab4- and Rab11-positive compartments in WT mouse platelets. Washed WT mouse platelets (5 × 108/mL) in HEPES Tyrode buffer containing 1 mM Ca2+ were incubated with FITC-Fg (0.05 mg/mL) for the indicated times and then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde at room temperature. After washing with PBS, the fixed platelets (5 × 107/mL) were allowed to adhere to poly-d-lysine–coated coverslips. Immunofluorescence staining was performed as described in “Methods” using anti-Rab4 rabbit polyclonal antibody or anti-Rab11 rabbit polyclonal antibody followed by TRITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Images were taken with a Nikon A1R confocal microscope (60X/1.49 NA DIC N2 oil) and digitally magnified ×15. Scale bar represents 1 µm.

FITC-Fg transits through Rab4- and Rab11-positive compartments after internalization. (A) Rab4- and Rab11-containing compartments are present in human platelets. Washed human platelets (5 × 108/mL) were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, washed, and allowed to adhere to poly-d-lysine–coated coverslips. Immunofluorescence staining was done as described in “Methods.” Platelets were incubated with anti-Rab4 mouse monoclonal antibody and anti-Rab11 rabbit polyclonal antibody, and then with Alexa 568 conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG or Alexa 488 conjugated anti-rabbit IgG, respectively. Images were taken with a Nikon A1R confocal microscope (60X/1.49 NA DIC N2 oil) and digitally magnified ×30. Scale bar represents 1 µm. (B) Internalized FITC-Fg goes through Rab4- and Rab11-positive compartments in WT mouse platelets. Washed WT mouse platelets (5 × 108/mL) in HEPES Tyrode buffer containing 1 mM Ca2+ were incubated with FITC-Fg (0.05 mg/mL) for the indicated times and then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde at room temperature. After washing with PBS, the fixed platelets (5 × 107/mL) were allowed to adhere to poly-d-lysine–coated coverslips. Immunofluorescence staining was performed as described in “Methods” using anti-Rab4 rabbit polyclonal antibody or anti-Rab11 rabbit polyclonal antibody followed by TRITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Images were taken with a Nikon A1R confocal microscope (60X/1.49 NA DIC N2 oil) and digitally magnified ×15. Scale bar represents 1 µm.

Discussion

In this study, we found that deletion of a small GTPase, Arf6, in platelets, resulted in defective Fg uptake and storage (Figures 1B and 3). Fg, bound at the surface, was apparently not transported to its proper storage site(s). Because αIIbβ3 is the major receptor for Fg uptake5 and its levels were normal in Arf6 KO platelets (Figure 1A), our data suggest a role for Arf6 in intraplatelet trafficking of αIIbβ3. Intracellular trafficking of integrins affects cell adhesion and migration and may affect platelet activity. Loss of Arf6 had no significant effects on the expression of other proteins (Figure 1A), nor was there any overt morphology defect (supplemental Figure 2B). Flow cytometry analysis confirmed that there were no detectible defects in total or activated levels of surface αIIbβ3 (Figure 2A-B). Fg binding also appeared normal (Figure 2C). Consistently, agonist-induced platelet aggregation and adenosine triphosphate release were unaffected (supplemental Figure 2A). Surprisingly, Arf6 loss enhanced platelet spreading on Fg and clot retraction; however, these effects were insufficient to significantly alter thrombus formation or hemostasis. The simplest interpretation of our data is that Arf6 affects Fg uptake and, by extension, αIIbβ3 trafficking in platelets. One can surmise that the ∼50% reduction in Fg uptake is not detrimental in the thrombosis and hemostasis models tested. Our data imply that αIIbβ3 trafficking contributes to platelet spreading and clot formation, which is consistent with the roles of integrin trafficking in migrating cells.

It is well-established that platelets and megakaryocytes do not synthesize Fg and that the Fg, stored in platelets, accumulates via a receptor-mediated endocytosis process with αIIbβ3 as its receptor.7 Platelet αIIbβ3 levels (Figure 1A) and plasma Fg levels (supplemental Figure 4) were normal in the Arf6 KO mice. As a possible explanation for our data, binding of Fg to αIIbβ3 could be less stable in Arf6 KO platelets, resulting in less efficient endocytosis. However, Fg binding to αIIbβ3 appeared unaffected (Figure 2C). Defective Fg storage, in Arf6 KO platelets, could result from mistargeting of endocytosed Fg into a degradative compartment. However, we failed to detect any biotin-Fg fragments (Figure 3C). Western blotting for other α-granule cargo and membrane proteins did not uncover any overt defects in granule biogenesis (Figure 1C). Thus, our data are most consistent with the defect in Fg uptake or storage in Arf6 KO platelets being because of either defective endocytosis or altered Fg/αIIbβ3 trafficking.

Integrin endocytosis and recycling are essential for adhesion and cell migration.23,24 Arf6 affects the routing between 2 integrin recycling pathways: a Rab4-mediated fast-recycling pathway and a Rab11-mediated slow-recycling pathway.19,22 Rab4 and Rab11 are present but did not colocalize suggesting that platelets contain both early and recycling endosomes (Figure 6A). Endocytosed Fg did gain access to both compartments, over time, in WT platelets (Figure 6B). A potential explanation for the Arf6 KO platelet phenotype is a redirection of Fg/αIIbβ3 into a Rab4-mediated fast pathway, reducing αIIbβ3’s internal residence time and resulting in less Fg being retained within the platelets. This hypothesis is consistent with our observations in Figure 3B,D, where Arf6 KO platelets contain lower levels of FITC-Fg in fewer punctate structures. Although we cannot directly exclude a defect in endocytosis, FITC-Fg was detected in internal punctate structures suggesting that bulk-phase endocytosis may still occur in the absence of Arf6. Other endocytosed cargo were unaffected (Figure 1C). To fully define the role of Arf6 in αIIbβ3 trafficking and the routes possible, extensive high-resolution imaging analysis will be needed. However, our present data are consistent with previous studies that platelets do contain sorting compartments, such as MVBs,30 which are known to be part of normal endocytic routes.

Given the proposed role of Arf6 in αIIbβ3 trafficking, we were surprised that flow cytometry analysis (Figure 2A-B) showed little alterations in the surface levels of αIIbβ3 in the Arf6 KO platelets. Because our FACS assays are static measurements, reflecting steady-state levels of surface αIIbβ3, they may not report on small populations of αIIbβ3 that rapidly recycle on and off the plasma membrane. Arf6 depletion did not affect the platelet signaling steps examined (Figure 5B-E and supplemental Figure 5), which contradicted our previous studies of human platelets using acylated peptides as Arf6 inhibitors.12 The myr-Arf6 peptide, compared with a myr-Arf1 peptide, inhibited uptake of FITC-Fg by human platelets (supplemental Figure 6B); however, mouse platelets were not sensitive to either acylated peptide (supplemental Figure 6A), so it is possible that there are some off-target effects for the myr-Arf6 peptide’s actions. It should be noted that mouse and human platelets contain different amounts of GIT1 (supplemental Figure 7), an Arf6 GTPase-activating protein, which could account for these species differences. Additional studies are underway to understand the effects of the acylated Arf6 peptides.

Because Arf6 could affect the endocytic trafficking of αIIbβ3, Arf6 depletion was expected to affect the platelet functions related to αIIbβ3. Indeed, Arf6 deficiency enhanced platelet spreading on Fg-coated surfaces and promoted platelet clot retraction (Figures 4B-D and 5A). If activated αIIbβ3 was recycling more rapidly in Arf6 KO platelets, more might be available to make contacts with Fg. This scenario is consistent with our previous findings regarding changes in Arf6-GTP/GDP levels in resting vs activated platelets.12,13 Resting human and mouse platelets have higher, active Arf6-GTP levels (perhaps a consequence of involvement in trafficking). Arf6-GTP decreases precipitously to Arf6-GDP upon platelet activation, and Arf6-GDP levels are maintained via an integrin-mediated process that requires Src family kinases and outside-in signaling.13 This “inactivated” state is mimicked by Arf6 deletion. During normal platelet activation, active Arf6-GTP may be reduced to promote spreading. Outside-in signaling in the spreading platelet suppresses recovery of Arf6-GTP to prolong spreading. The enhanced spreading phenotype appeared specific for Fg because it was not detected on other coated surfaces (supplemental Figure 8). Based on the spreading and clot retraction phenotype, we expected that the Arf6 KO mice should be hyperthrombotic; however, that was not detected in the 2 assays used. This would suggest that the enhancements of spreading and clot retraction are not sufficient to cause robust alterations in clot formation in vivo.

Our studies represent some of the first mechanistic analyses of endocytosis by platelets. Although recognized, for ∼30 years, as a process to load granules with Fg,18,36 our data imply more acute functions for endocytosis in clot formation. A refined role for such platelet endocytosis is still unclear; however, one could envision the endocytic trafficking of integrins being involved in modulating interplatelet connections in a growing thrombus. Also, although still uncharacterized, it would seem possible that platelets may migrate in the forming clot, and thus endocytic trafficking of cell surface integrins may play a role in that process as it does in migrating, nucleated cells. The mice we characterized in this manuscript will assist in the continued study of such processes and in the determination of their relevance to thrombosis.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors are immensely grateful to members of the Whiteheart laboratory for their careful reading of this manuscript and their helpful comments. The authors thank the staff of the University Imaging Facility for help with the electron microscopy analysis, Greg Bauman at the University Flow Cytometry Core Facility for help with the FACS analysis, and the staff of Department of Laboratory Animal Resources for their assistance. The authors also thank Dr Richard T. Premont at Duke University for generously providing us GIT1 and GIT2 brain tissue for western blots.

The Departmental Imaging Facility, where all the fluorescence imaging was done, is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health National Center for Research Resources (P20 RR020171). This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL56652 and HL082193 [S.W.W.] and HL68819 [Z.L.]), an American Heart Association (AHA) predoctoral fellowship (11PRE7500051) (Y.H.), a Grant-in-Aid from AHA Great Rivers Affiliate (Z.L.), and a Scientist Development Grant from AHA Great Rivers Affiliate (B.X.).

Authorship

Contribution: Y.H. and S.W.W. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; S.J. performed some of the experiments; Z.L. and B.X. helped with the in vivo Fg uptake experiment; Y.K. contributed the Arf6flox/flox mouse strain; C.L.M. assisted with the microscopy; and B.A.B. contributed valuable reagents and key methodologic insights.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Sidney W. Whiteheart, Department of Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry, University of Kentucky College of Medicine, B271 BBSRB, 741 South Limestone, Lexington, KY 40536; e-mail: whitehe@uky.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal