To the editor:

Genome surveys have offered a comprehensive view of the genetic landscape of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), identifying several recurrently mutated genes, including myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MYD88). The predominant mutation concerns a p.L265P substitution within exon 5,1,2 which leads to constitutive nuclear factor κB stimulation, thus conferring a proliferation and survival advantage to the mutant cells.1 MYD88 mutations reach up to 2% to 5% in CLL and are strikingly enriched among patients expressing mutated IGHV genes (M-CLL).3-5

According to a recent study, MYD88 mutations were biased to younger patients with CLL and associated with longer time to first treatment (TTFT) and overall survival (OS),6 which is in contrast with previous studies reporting no differences in TTFT or OS for MYD88 mutant vs wild-type patients.3-5 To gain further insight into this issue, we reappraised the clinical significance of MYD88 mutations in a collaborative multicenter series of 1039 well-annotated CLL cases. Information about the patient cohort and the methodology is provided in supplemental Data, available on the Blood Web site. Approval was obtained from the local Ethics Review Committee of the participating institutions. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Overall, MYD88 mutations were identified in 21 (2%) of 1039 cases. All concerned M-CLL cases accounted for 4% (21/537 cases) within this subgroup; 19/21 (90%) cases carried the hotspot p. L265P substitution. Given their exclusivity to M-CLL, further evaluation of the biological and clinical associations of MYD88 mutations was based on comparisons of MYD88 mutant cases with wild-type M-CLL cases (supplemental Table 2), as well as comparisons with published studies (supplemental Table 3). Thus, we avoided the confounding effect of distinct prognosis associated with the different IGHV gene somatic hypermutation status. Put differently, as wild-type MYD88 cases concern both M-CLL and CLL expressing unmutated IGHV genes, with the latter displaying significantly worse outcome,7,8 the comparison of mutant MYD88 cases, which exclusively concern M-CLL, with this wild-type group, irrespective of somatic hypermutation status, could produce misleading results.

In general, mutant and wild-type MYD88 M-CLL cases did not differ, with the exception of a male predominance among MYD88 mutant cases (P = .01) (supplemental Table 2). The median age of both groups was similar (64.4 years [range, 43-82 years] vs 64.3 years [range, 32-92 years]; P = .66); hence, we cannot confirm the recently reported association between MYD88 mutations and a younger age at diagnosis. This discrepancy could be a result of the combined effect of the differential composition of the evaluated cohorts and the overall rarity of MYD88 mutations.

Regarding the genetic aberrations, the 2 groups were highly similar; that is, both had a high frequency of isolated deletion of chromosome 13q and a complete absence or low frequency of both intermediate/poor prognostic cytogenetic abnormalities and mutations in the TP53, SF3B1, and NOTCH1 genes. A trend was noted in favor of Binet stage B/C at diagnosis (P = .08) and IGHV3-23 gene usage (P = .08) in MYD88 mutant vs wild-type cases (supplemental Table 2). None of the MYD88 mutant cases was assigned to any of the major subsets with stereotyped B-cell receptors.9

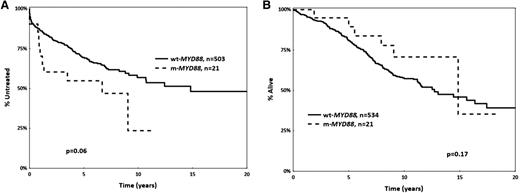

Regarding prognostic implications, mutant MYD88 M-CLL cases showed a tendency (P = .06) for shorter median TTFT compared with wild-type MYD88 M-CLL cases (6.6 years [95% confidence interval, 0.5-9 years] vs 14.8 years [95% confidence interval, 0.2-16 years]) (Figure 1). However, this difference could be attributed to the enrichment for advanced clinical stage among mutant MYD88 cases. Indeed, when restricting the analysis to Binet stage A cases, no difference in TTFT or OS was observed between MYD88 mutated vs wild-type M-CLL patients (supplemental Figure 1).

Kaplan-Meier curves for MYD88 mutant (m-MYD88) and MYD88 wild-type (wt-MYD88) cases. (A) Time to first treatment, and (B) overall survival. All cases carry mutated IGHV genes (M-CLL).

Kaplan-Meier curves for MYD88 mutant (m-MYD88) and MYD88 wild-type (wt-MYD88) cases. (A) Time to first treatment, and (B) overall survival. All cases carry mutated IGHV genes (M-CLL).

To our knowledge, no other published study has evaluated the prognostic significance of MYD88 mutations within M-CLL, which is the relevant group to consider, given the strong bias for MYD88 mutations to M-CLL, as evidenced by this and previous studies. The distinction between M-CLL and CLL expressing unmutated IGHV genes is fundamental not only for understanding the biology of the disease but also in the context of prognostication and prediction.10 Along these lines, we argue that conclusions regarding the clinical implications of any biomarker should always be adjusted to IGHV gene mutational status.

In conclusion, our findings question the recent proposal that MYD88 mutant cases may display a distinct clinical behavior attributed solely to the mutations themselves. That said, the possibility of a distinct biological profile linked to constitutional nuclear factor κB activation remains, which could prove to be of therapeutic relevance in the future. Larger collaborative studies in CLL are imperative to study the prognostic and predictive relevance of MYD88 mutations, if any.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Authorship

Acknowledgments: This work was supported in part by the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Research Council, Uppsala University Hospital, and Lion’s Cancer Research Foundation, Uppsala, project MSMT CR CZ.1.05/1.1.00/02.68 (CEITEC) and IGA MZ CR NT13493-4/2012, Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro AIRC (Investigator Grant and Special Program Molecular Clinical Oncology, 5 per mille #9965) and Ricerca Finalizzata 2010, Ministero della Salute, Roma; the ENosAI project (code 09SYN-13-880), cofunded by the European Union and the General Secretariat for Research and Technology of Greece; and the KRIPIS action, funded by the General Secretariat for Research and Technology of Greece.

Contribution: P.B. performed research and wrote the paper. A.H., A.A., D.R., L.-A.S., J.K., L.S., S.P., and G.G. performed research. K.S., P.G., and R.R. designed the study and wrote the paper, which was approved by all the authors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Paolo Ghia, Università Vita-Salute San Raffaele, Via Olgettina 58, 20132 Milan, Italy; e-mail: ghia.paolo@hsr.it.

References

Author notes

K.S., P.G., and R.R. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal