Key Points

Hemolytic processes induce rapid systemic and vascular inflammation in C57BL/6 mice that is abolished by a single dose of hydroxyurea (HU).

HU exerts some NO-dependent effects and should be investigated as an acute treatment of SCD and for other hemolytic disorders.

Abstract

Hemolysis and consequent release of cell-free hemoglobin (CFHb) impair vascular nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability and cause oxidative and inflammatory processes. Hydroxyurea (HU), a common therapy for sickle cell disease (SCD), induces fetal Hb production and can act as an NO donor. We evaluated the acute inflammatory effects of intravenous water-induced hemolysis in C57BL/6 mice and determined the abilities of an NO donor, diethylamine NONOate (DEANO), and a single dose of HU to modulate this inflammation. Intravenous water induced acute hemolysis in C57BL/6 mice, attaining plasma Hb levels comparable to those observed in chimeric SCD mice. This hemolysis resulted in significant and rapid systemic inflammation and vascular leukocyte recruitment within 15 minutes, accompanied by NO metabolite generation. Administration of another potent NO scavenger (2-phenyl-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide) to C57BL/6 mice induced similar alterations in leukocyte recruitment, whereas hemin-induced inflammation occurred over a longer time frame. Importantly, the acute inflammatory effects of water-induced hemolysis were abolished by the simultaneous administration of DEANO or HU, without altering CFHb, in an NO pathway–mediated manner. In vitro, HU partially reversed the Hb-mediated induction of endothelial proinflammatory cytokine secretion and adhesion molecule expression. In summary, pathophysiological levels of hemolysis trigger an immediate inflammatory response, possibly mediated by vascular NO consumption. HU presents beneficial anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting rapid-onset hemolytic inflammation via an NO-dependent mechanism, independently of fetal Hb elevation. Data provide novel insights into mechanisms of hemolytic inflammation and further support perspectives for the use of HU as an acute treatment for SCD and other hemolytic disorders.

Introduction

Red blood cell (RBC) destruction, or hemolysis, leads to the release of hemoglobin (Hb) into the plasma. Once in the plasma, cell-free hemoglobin (CFHb) is usually neutralized into less toxic metabolites by specialized scavenger proteins, such as haptoglobin and hemopexin.1,2 However, after procedures such as mismatched transfusions and hemodialysis and in some diseases, including malaria, sepsis, and hemolytic anemias (eg, sickle cell disease [SCD] and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria), levels of intravascular Hb can become excessive.3-5 Consequences of augmented CFHb include increased vascular nitric oxide (NO) consumption, oxidative stress, endothelial activation, and cytokine upregulation,3,6-9 all of which contribute significantly to the pathophysiology of these disorders. Endothelial activation leads to the expression of surface adhesion molecules, which can result in the recruitment of leukocytes and platelets, thus increasing inflammatory processes.10 In SCD, such leukocyte recruitment is significant because the adhesion of white blood cells (WBCs) and RBCs to the vascular wall can trigger vaso-occlusive processes. Furthermore, once oxidized, Hb releases hemin, a hydrophobic molecule recently demonstrated to induce neutrophil extracellular trap production11 and cause toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) –mediated stasis in murine SCD.12 Thus, hemolysis constitutes a major disease mechanism, and failure to neutralize CFHb can cause vascular and organ dysfunction, leading to the adverse clinical effects that have been associated with hemolytic diseases, including leg ulcers, pulmonary hypertension, and priapism.13

Hydroxyurea (HU) is a cytostatic drug, frequently used in the treatment of hematologic diseases such as SCD, beta thalassemia, polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myelofibrosis, as well as nonhematologic diseases such as HIV/AIDS.14-16 In SCD, HU modifies the disease process, improving hematologic parameters and reducing hospitalization and mortality.17 One of the major mechanisms of action of HU in SCD is believed to be its ability to induce the production of fetal Hb (HbF) in erythrocytes, reducing hemoglobin S (HbS) polymerization and red cell sickling.18,19 However, it is becoming increasingly clear that HU also has immediate benefits that can be observed in SCD before elevations in HbF occur; such alterations include reductions in leukocyte counts and improved blood flow as a result of local vasodilation.20-22 A possible explanation for the acute effects of HU lies in its NO donor property; previous reports have suggested that intravascular generation of NO occurs in SCD individuals after administration of HU.23-25 NO, in turn, facilitates vasodilatation via activation of intracellular cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) signaling in smooth muscle cells and can reduce endothelial and leukocyte activation.20,26,27 In a recent study, we reported that HU has immediate and acute beneficial effects in a murine sickle cell model (BERK) of inflammatory vaso-occlusion, reducing leukocyte adhesion recruitment and secondary RBC interactions, particularly when administered together with a cGMP-amplifying agent.28

The aim of this study was to observe the acute inflammatory effects of hemolytic processes in C57BL/6 mice and to compare them with inflammatory processes observed in chimeric SCD mice. Our data suggest that, in addition to its other well-documented effects,8 depletion of vascular NO by CFHb may contribute to the inflammatory effects of hemolysis. In addition, the abilities of an NO donor, diethylamine NONOate (DEANO), and a single-dose administration of HU to diminish hemolysis-induced inflammation were verified, as was the participation of NO/cGMP-dependent mechanisms in these effects.

Methods

Animals

C57BL/6 mice and chimeric SCD mice (generated from the transplantation of bone marrow from HbSS BERK SCD mice into lethally irradiated male C57BL/6 mice) were used in the study.28,29 For further information about animals, their diets, housing, transplantation, and confirmation of human globin expression, please see supplemental Data available on the Blood Web site. All animal procedures were carried out in accordance with the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care (http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/not96-208.html) and in accordance with current Brazilian laws for the protection of animals. This study was approved by the Commission for Ethics in Animal Experimentation of the University of Campinas (protocol 2360-1).

Hemolysis protocol and mouse treatments

Hemolysis was induced in mice by the IV injection of water (H2O 150 µL) at 15 to 60 minutes before analyses, unless otherwise indicated. An acute inflammatory reaction was induced in some mice by the injection of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α; 0.5 µg intraperitoneally [IP]) 180 minutes prior to analyses. Some mice were also treated with HU 250 mg/kg IV (dose was determined on the basis of body surface area normalization for mice and represents the equivalent of 20 mg/kg in humans30 ), DEANO (0.4 mg/kg IV), or vehicle (saline) concomitantly with TNF-α or H2O administration (in separate boluses). In some experiments, mice were pretreated 75 minutes before H2O administration with a soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) inhibitor, 1H-[1,2,4] oxadiazolo [4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ; 15 mg/kg IP), or with 2-phenyl-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide (PTIO; 1 mg/kg IV), a scavenger of NO that does not affect nitric oxide synthase activity, or with vehicle (2% dimethylsulfoxide in saline, or saline). PTIO was also used alone 15 minutes before analyses in some experiments. Hemin (40 µmol/kg IP or IV), haptoglobin (7.14 mg/kg IV; Molecular Innovations Inc., Novi, MI), or hemopexin (4.46 mg/kg IV) were also administered, as indicated. All reagents and drugs were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated.

In vivo imaging system (IVIS) protocol

A chemiluminescent probe (XenoLight Rediject Inflammation Probe; Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) was used to evaluate in vivo myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity. Mice were pretreated with TNF-α, H2O, HU, DEANO, saline, or vehicle and then anesthetized in a plastic chamber (2.5% isoflurane/oxygen). The probe (200 mg/kg) was then injected intravenously immediately before image capture (5-minute exposure) and luminescent detection by using an IVIS Lumina System (Caliper Life Sciences Inc, Hopkinton, MA). Isoflurane anesthesia (1.5%) was maintained during IVIS procedures. Signal intensity was quantified as the photon flux (photons per second) within the region of interest by using IVIS Living Image 3.0 software (Caliper Life Sciences).

Plasma Hb and nitrate quantification

Plasma was stored at −80°C for CFHb quantification by using the Fairbanks AII method, as described.31 Samples were centrifuged (1200g for 10 minutes) before quantification, and Hb concentrations are expressed as µM heme associated with Hb, assuming that Hb is tetramic. Plasma nitrate was quantified by using a nitrate/nitrite colorimetric assay (Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI).

Intravital microscopy

After treatment protocols, mice were anesthetized (2% α-chloralose/10% urethane in phosphate-buffered saline) and tracheostomized. The cremaster muscle was surgically exteriorized and continuously superfused with bicarbonate-buffered saline (37°C, pH 7.4) and equilibrated with a mixture of 95% N2 and 5% CO2. For all protocols, microvessels (8-15 for each mouse) were visualized after surgery by using a custom-designed intravital microscope (Imager A2, Zeiss; ×63 magnification), and images were recorded for 30 to 90 seconds by using a video camera device (AxioCam HSm, Zeiss). Leukocyte (WBC) rolling, adhesion, and extravasation were monitored and analyzed for 30 to 45 minutes after surgery, unless otherwise stated. The definitions of leukocyte rolling, adhesion, and extravasation have been previously described.28,29

Human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) cultures and analyses

For information regarding HUVEC cultures and analyses by flow cytometry and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, please see supplemental Data.

Neutrophil isolation, incubation with RBC lysate, and adhesion assays

For information regarding in vitro neutrophil assays, please see supplemental Data.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses are described in the supplemental Data.

Results

IV administration of H2O induces rapid hemolysis in C57BL/6 mice

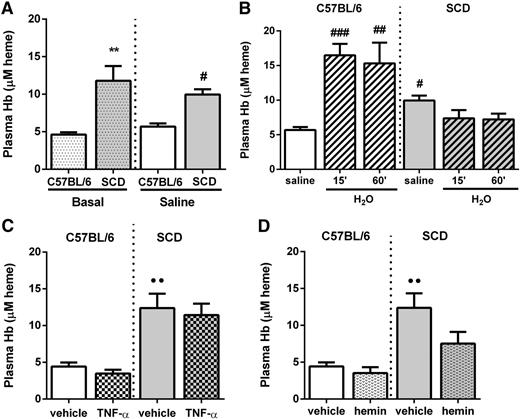

Under basal conditions, or at 15 minutes after IV administration of saline, C57BL/6 mice present with low-level intravascular hemolysis, as evaluated by determining plasma CFHb (Figure 1A). In contrast, basal hemolysis was approximately 2.5-fold higher in chimeric SCD mice. Intravenous injection of sterile H2O (150 μL) induced a marked increase in CFHb within just 15 minutes in C57BL/6 mice (Figure 1B), resulting in levels of CFHb similar to those of nonmanipulated chimeric SCD mice (Figure 1A). In contrast, sterile H2O injection does not induce further hemolysis in chimeric SCD mice within 60 minutes (Figure 1B). Plasma CFHb levels were not elevated by IP administration of either the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α (0.5 µg; Figure 1C) or hemin (40 µmol/kg; Figure 1D) in either C57BL/6 mice or chimeric SCD mice within 180 and 120 minutes, respectively.

Administration of H2O, but not TNF-α or hemin, increases plasma Hb levels in C57BL/6 mice. Plasma Hb concentration in C57BL/6 or chimeric SCD mice (A) at baseline or 15 minutes after administration of saline (150 μL IV; n = 5 to 9 mice), (B) at 15 minutes after administration of saline or 15 and 60 minutes after administration of H2O (150 µL IV; n = 4 to 9 mice), (C) at 180 minutes after administration of TNF-α or vehicle (0.5 µg IP; n = 4 to 6 mice), and (D) at 120 minutes after administration of hemin or vehicle (40 µmol/kg IP; n = 3 to 6 mice). Plasma Hb is expressed as µM heme associated with Hb, assuming that Hb is tetramic. **P < .01 compared with basal C57BL/6; #P < .05, ##P < .01, and ###P < .001 compared with C57BL/6 plus saline; ●●P < .01 compared with vehicle (C57BL/6).

Administration of H2O, but not TNF-α or hemin, increases plasma Hb levels in C57BL/6 mice. Plasma Hb concentration in C57BL/6 or chimeric SCD mice (A) at baseline or 15 minutes after administration of saline (150 μL IV; n = 5 to 9 mice), (B) at 15 minutes after administration of saline or 15 and 60 minutes after administration of H2O (150 µL IV; n = 4 to 9 mice), (C) at 180 minutes after administration of TNF-α or vehicle (0.5 µg IP; n = 4 to 6 mice), and (D) at 120 minutes after administration of hemin or vehicle (40 µmol/kg IP; n = 3 to 6 mice). Plasma Hb is expressed as µM heme associated with Hb, assuming that Hb is tetramic. **P < .01 compared with basal C57BL/6; #P < .05, ##P < .01, and ###P < .001 compared with C57BL/6 plus saline; ●●P < .01 compared with vehicle (C57BL/6).

Hemolysis induces extensive systemic inflammation in C57BL/6 mice comparable to that of administration of TNF-α cytokine

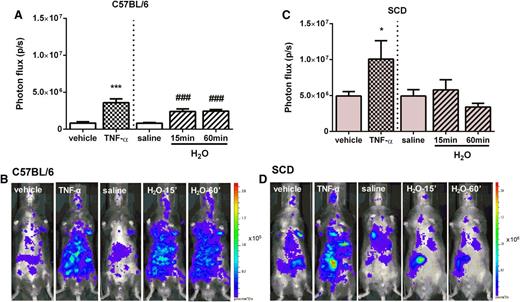

C57BL/6 mice received hemolytic or inflammatory stimuli, and systemic inflammation was quantified by using a probe to detect MPO in activated neutrophils with in vivo imaging. Rapid hemolysis induced by administration of H2O was accompanied by extensive inflammation that was comparable to that induced by IP administration of TNF-α (Figure 2A-B). Inflammation induced by both H2O and TNF-α was observed throughout the entire bodies of the C57BL/6 mice, with a greater dissemination in the abdominal/peritoneal area. In contrast, the administration of similar volumes of a vehicle solution or of saline did not produce inflammation. Interestingly, basal inflammation in chimeric SCD mice (Figure 2C-D) was found to be significantly higher than that of basal inflammation of C57BL/6 mice, showing similar levels to those of hemolysis-induced C57BL/6 mice. IP administration of TNF-α induced a further significant systemic inflammatory response in these chimeric SCD mice (Figure 2C-D); however, IV injection of H2O in chimeric SCD mice did not result in any further increase in inflammation, in keeping with the finding that this approach does not generate further hemolysis in chimeric SCD mice (Figure 2C-D).

Bioluminescence imaging of myeloperoxidase activity in C57BL/6 and chimeric SCD mice after administration of TNF-α and H2O. Quantification of systemic inflammation in (A) C57BL/6 and (C) chimeric SCD mice after treatment with TNF-α (0.5 µg IP; 180 minutes; n = 3 to 5 mice) or vehicle and H2O (150 µL IV; 15 or 60 minutes; n = 5 to 12 mice) or saline. *P < .05 and ***P < .001 compared with vehicle and ###P < .001 compared with saline. Illustrative images from each treatment in (B) C57BL/6 and (D) chimeric SCD mice. Mice were injected with a chemiluminescent probe that reacts with myeloperoxidase produced by activated phagocytes and/or neutrophils. Signal intensity was quantified as the photon flux (photons per second) within the region of interest.

Bioluminescence imaging of myeloperoxidase activity in C57BL/6 and chimeric SCD mice after administration of TNF-α and H2O. Quantification of systemic inflammation in (A) C57BL/6 and (C) chimeric SCD mice after treatment with TNF-α (0.5 µg IP; 180 minutes; n = 3 to 5 mice) or vehicle and H2O (150 µL IV; 15 or 60 minutes; n = 5 to 12 mice) or saline. *P < .05 and ***P < .001 compared with vehicle and ###P < .001 compared with saline. Illustrative images from each treatment in (B) C57BL/6 and (D) chimeric SCD mice. Mice were injected with a chemiluminescent probe that reacts with myeloperoxidase produced by activated phagocytes and/or neutrophils. Signal intensity was quantified as the photon flux (photons per second) within the region of interest.

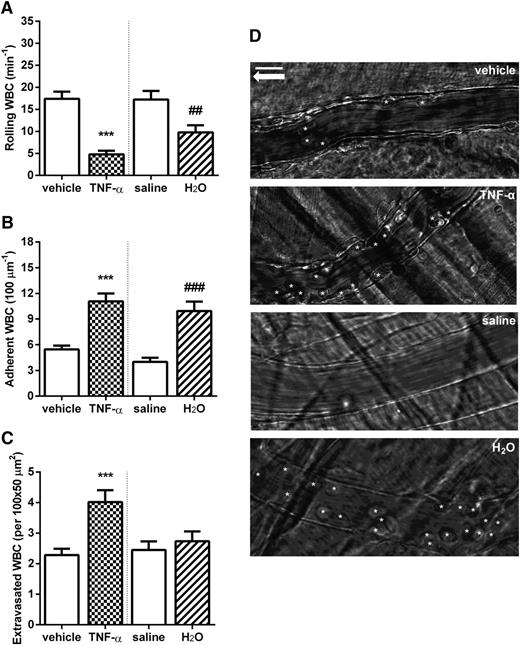

Rapid hemolysis induces vascular leukocyte recruitment in C57BL/6 mice comparable to that of TNF-α administration

We then looked at the effects of H2O-induced rapid hemolysis on leukocyte dynamics in the microcirculation of C57BL/6 mice by using intravital microscopy. Previous studies32-34 have comprehensively shown the effects of inflammatory stimuli on the induction of leukocyte adhesion to the microvasculature. In BERK SCD mice, inflammatory stimuli lead to leukocyte recruitment, followed by secondary RBC capture and eventually vaso-occlusive processes.28,29,35 In C57BL/6 mice, as expected, at 3 hours after administration of TNF-α (0.5 µg IP), leukocytes demonstrated decreased rolling and markedly increased adhesion to the microvascular walls as well as augmented extravasation (Figure 3). Surprisingly, IV administration of H2O in C57BL/6 mice with ensuing hemolysis caused a significant decrease in leukocyte rolling and increased leukocyte adhesion to the microvascular walls (Figure 3A-B) within 15 minutes. These effects were similar in magnitude to those resulting from a TNF-α inflammatory stimulus.

Rapid hemolysis caused by the IV administration of H2O is associated with increased leukocyte (WBC) recruitment in C57BL/6 mice. WBC (A) rolling, (B) adhesion, and (C) extravasation in the cremaster microcirculation, determined at 180 minutes after administration of TNF-α (0.5 µg IP) or vehicle or 15 minutes after H2O (150 µL IV) or saline. ***P < .001 compared with vehicle; ##P < .01 and ###P < .001 compared with saline; n = 28 to 53 venules from 3 to 6 mice. (D) Representative images of C57BL/6 mice venules after treatments. White stars represent adherent WBCs; white arrow indicates the direction of blood flow. Scale bar, 15 µm.

Rapid hemolysis caused by the IV administration of H2O is associated with increased leukocyte (WBC) recruitment in C57BL/6 mice. WBC (A) rolling, (B) adhesion, and (C) extravasation in the cremaster microcirculation, determined at 180 minutes after administration of TNF-α (0.5 µg IP) or vehicle or 15 minutes after H2O (150 µL IV) or saline. ***P < .001 compared with vehicle; ##P < .01 and ###P < .001 compared with saline; n = 28 to 53 venules from 3 to 6 mice. (D) Representative images of C57BL/6 mice venules after treatments. White stars represent adherent WBCs; white arrow indicates the direction of blood flow. Scale bar, 15 µm.

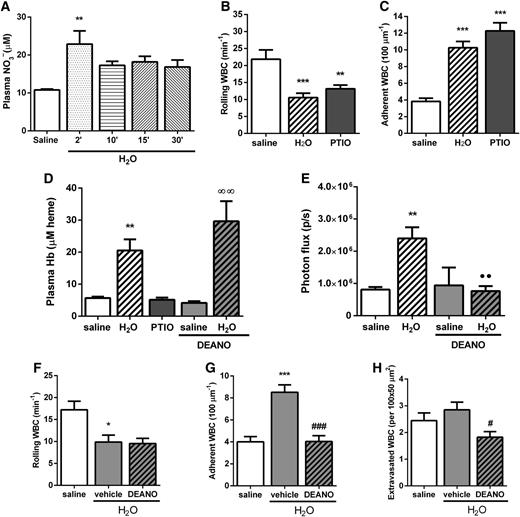

Scavenging of NO is associated with a rapid onset of vascular inflammation

Consistent with reports that vascular hemolysis results in substantial NO consumption by CFHb, we found significant plasma nitrate generation within 2 minutes of IV administration of H2O in C57BL/6 mice (Figure 4A). Hypothesizing that NO depletion by CFHb may participate in the rapid onset of H2O-induced hemolytic inflammation, we administered another potent NO scavenger in C57BL/6 mice (PTIO 1 mg/kg IV) and observed leukocyte recruitment in the microcirculation after 15 minutes (Figure 4B-C). PTIO induced alterations in leukocyte rolling and adhesion similar to those provoked by IV H2O without changing plasma Hb (Figure 4D), indicating that NO consumption per se can induce vascular inflammation in an Hb-independent manner.

NO scavenging induces leukocyte recruitment, and NO donation reverses the systemic inflammation and leukocyte recruitment induced by H2O in C57BL/6 mice. (A) Plasma nitrate (NO3–) concentration in C57BL/6 mice at 2 to 30 minutes after administration of H2O (150 µL IV) or saline; n = 3 mice. WBC (B) rolling and (C) adhesion determined 15 minutes after administration of saline, H2O (150 µL IV), or PTIO (1.0 mg/kg IV); n = 34 to 48 venules from 4 to 6 mice. (D) Plasma Hb levels in C57BL/6 mice 15 minutes after receiving saline (150 µL IV), H2O (150 µL IV), PTIO (1.0 mg/kg IV), or DEANO (0.4 mg/kg IV) coadministered with either saline or H2O (150 µL IV); n = 3 to 11 mice. (E) Inflammatory status was analyzed by IVIS at 15 minutes after administration of H2O or saline (150 µL IV) in the presence or absence of DEANO (0.4 mg/kg IV; n = 3 to 6 mice). WBC (F) rolling, (G) adhesion, and (H) extravasation determined 15 minutes after coadministration of DEANO or vehicle (0.4 mg/kg IV) plus saline or H2O (150 µL IV) (n = 24 to 28 venules from 3 mice). *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001 compared with saline; ∞∞P < .01 compared with saline + DEANO; ●●P < .01 compared with H2O alone; #P < .05 and ###P < .001 compared with H2O + vehicle.

NO scavenging induces leukocyte recruitment, and NO donation reverses the systemic inflammation and leukocyte recruitment induced by H2O in C57BL/6 mice. (A) Plasma nitrate (NO3–) concentration in C57BL/6 mice at 2 to 30 minutes after administration of H2O (150 µL IV) or saline; n = 3 mice. WBC (B) rolling and (C) adhesion determined 15 minutes after administration of saline, H2O (150 µL IV), or PTIO (1.0 mg/kg IV); n = 34 to 48 venules from 4 to 6 mice. (D) Plasma Hb levels in C57BL/6 mice 15 minutes after receiving saline (150 µL IV), H2O (150 µL IV), PTIO (1.0 mg/kg IV), or DEANO (0.4 mg/kg IV) coadministered with either saline or H2O (150 µL IV); n = 3 to 11 mice. (E) Inflammatory status was analyzed by IVIS at 15 minutes after administration of H2O or saline (150 µL IV) in the presence or absence of DEANO (0.4 mg/kg IV; n = 3 to 6 mice). WBC (F) rolling, (G) adhesion, and (H) extravasation determined 15 minutes after coadministration of DEANO or vehicle (0.4 mg/kg IV) plus saline or H2O (150 µL IV) (n = 24 to 28 venules from 3 mice). *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001 compared with saline; ∞∞P < .01 compared with saline + DEANO; ●●P < .01 compared with H2O alone; #P < .05 and ###P < .001 compared with H2O + vehicle.

Given the known effect that the Hb product hemin has on inflammatory processes, we administered hemin to C57BL/6 mice and evaluated leukocyte recruitment over time. Hemin, when given both IV (supplemental Figure 1A-C) and IP (data not shown), was indeed able to induce leukocyte recruitment, but only over a prolonged time period, with peak leukocyte recruitment occurring at approximately 2 hours after administration of hemin. To further investigate the role of CFHb and hemin release in the rapid inflammation instigated by H2O-induced hemolysis, we induced hemolysis (H2O IV) and concomitantly administered either haptoglobin (extracellular Hb scavenger) or hemopexin (a hemin scavenger) and observed leukocyte recruitment after 15 minutes (supplemental Figure 1D-F). Although haptoglobin almost abolished the effects of hemolysis on leukocyte recruitment, hemopexin did not significantly modify the effects of H2O-induced hemolysis on leukocyte adhesion and extravasation. Data are consistent with the hypothesis that the consumption of NO by CFHb may contribute to the acute and immediate inflammatory effects of H2O-induced inflammation.

An NO donor reduces the inflammatory effects of hemolysis in C57BL/6 mice

DEANO, an NO donor, was intravenously injected concomitantly with H2O in mice. As illustrated in Figure 4D, DEANO does not alter plasma CFHb levels and therefore does not prevent H2O-induced hemolysis. However, DEANO significantly inhibited H2O-induced hemolytic systemic inflammation in C57BL/6 mice (Figure 4E). Furthermore, although coadministration of DEANO and H2O did not significantly alter hemolysis-induced WBC rolling (Figure 4F), significant reductions in WBC adhesion and extravasation (Figure 4G-H) were observed in C57BL/6 mice compared with mice receiving H2O and vehicle.

HU reduces the inflammatory effects of hemolysis in C57BL/6 mice

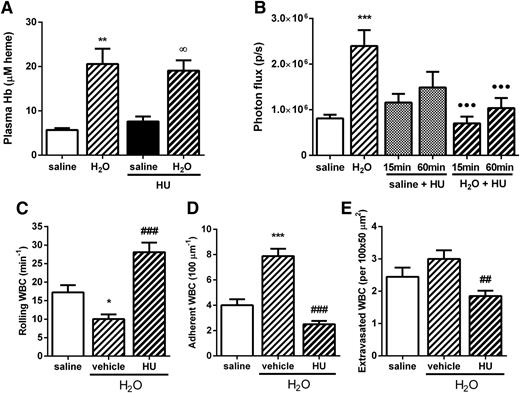

The effects of a single dose of HU (250 mg/kg IV) on acute H2O-induced hemolytic inflammation were evaluated. Similar to DEANO, administration of HU together with H2O (IV) did not abolish the H2O-induced elevation in CFHb in C57BL/6 mice (Figure 5A). However, HU reversed the inflammatory effects of hemolysis, reducing systemic inflammation (as measured by MPO detection by IVIS; Figure 5B) and significantly abrogating leukocyte recruitment in the microvasculature, reversing the effects of IV H2O on leukocyte rolling, adhesion, and extravasation (Figure 5C-E). At the lower dose of 100 mg/kg, HU also significantly reduced hemolysis-induced leukocyte adhesion and extravasation in the microcirculation but did not inhibit alterations in leukocyte rolling mechanisms (see supplemental Figure 2).

A single dose of HU abolishes the induction of systemic inflammation and leukocyte recruitment by H2O-mediated hemolysis in C57BL/6 mice. (A) Plasma Hb levels in C57BL/6 mice at 15 minutes after receiving H2O or saline (150 µL IV) in the presence of HU or vehicle (250 mg/kg IV); n = 4 to 11 mice. (B) Inflammatory status was analyzed by IVIS at 15 minutes after administration of H2O or saline (150 µL IV) in the presence of HU (250 mg/kg IV) or vehicle; n = 4 to 9 mice. WBC (C) rolling, (D) adhesion, and (E) extravasation determined 15 minutes after coadministration of saline or H2O (150 µL IV) plus HU or vehicle (250 mg/kg IV); n = 28 to 33 venules in 3 to 4 mice. *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001 compared with saline; ∞P < .05 compared with saline + HU; ●●●P < .001 compared with H2O; ##P < .01 and ###P < .001 compared with H2O + vehicle.

A single dose of HU abolishes the induction of systemic inflammation and leukocyte recruitment by H2O-mediated hemolysis in C57BL/6 mice. (A) Plasma Hb levels in C57BL/6 mice at 15 minutes after receiving H2O or saline (150 µL IV) in the presence of HU or vehicle (250 mg/kg IV); n = 4 to 11 mice. (B) Inflammatory status was analyzed by IVIS at 15 minutes after administration of H2O or saline (150 µL IV) in the presence of HU (250 mg/kg IV) or vehicle; n = 4 to 9 mice. WBC (C) rolling, (D) adhesion, and (E) extravasation determined 15 minutes after coadministration of saline or H2O (150 µL IV) plus HU or vehicle (250 mg/kg IV); n = 28 to 33 venules in 3 to 4 mice. *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001 compared with saline; ∞P < .05 compared with saline + HU; ●●●P < .001 compared with H2O; ##P < .01 and ###P < .001 compared with H2O + vehicle.

HU reduces hemolysis-induced inflammation via an NO-dependent pathway

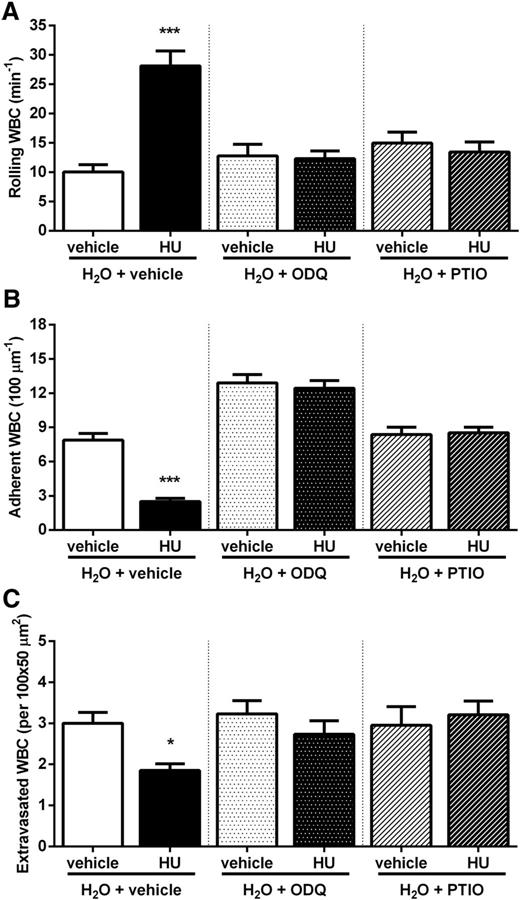

Hypothesizing that the acute beneficial effects of HU on hemolytic inflammatory processes are the result of NO release in vivo and/or stimulation of cGMP-dependent signaling, we administered H2O (IV) in C57BL/6 mice together with HU and the NO scavenger PTIO or ODQ (an sGC inhibitor). Figure 6 demonstrates that both PTIO and ODQ abrogate the beneficial effects of HU on WBC rolling, adhesion, and extravasation.

HU exerts its effects via an NO/cGMP–dependent pathway. WBC (A) rolling, (B) adhesion, and (C) extravasation in H2O-treated C57BL/6 mice after administration of HU (250 mg/kg IV) or vehicle in the presence of ODQ (15 mg/kg IP) or PTIO (1 mg/kg IV) or vehicle. *P < .05 and ***P < .001 compared with vehicle. n = 22 to 33 venules from 3 to 4 mice.

HU exerts its effects via an NO/cGMP–dependent pathway. WBC (A) rolling, (B) adhesion, and (C) extravasation in H2O-treated C57BL/6 mice after administration of HU (250 mg/kg IV) or vehicle in the presence of ODQ (15 mg/kg IP) or PTIO (1 mg/kg IV) or vehicle. *P < .05 and ***P < .001 compared with vehicle. n = 22 to 33 venules from 3 to 4 mice.

Effects of Hb on endothelial cells can be partially inhibited by HU

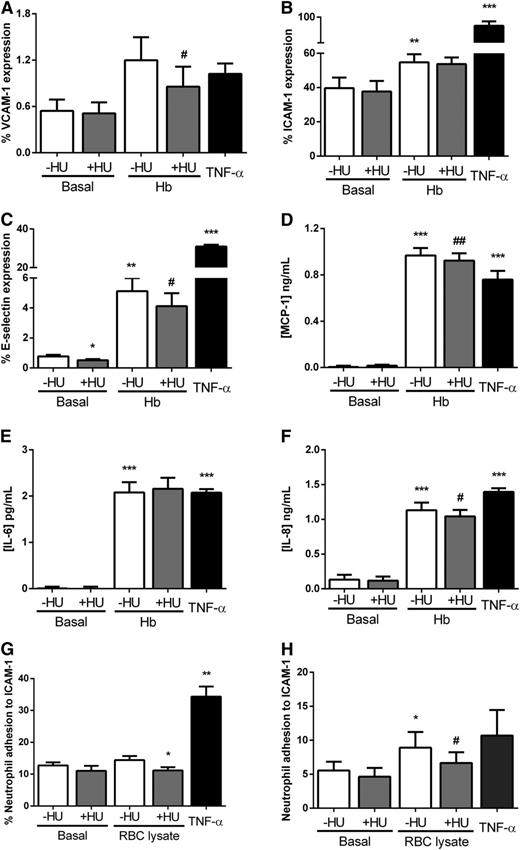

Given that CFHb may exert some of its inflammatory effects via endothelial activation, we looked at the effect of the inhibition of endothelial adhesion molecules on H2O-induced hemolytic inflammation in vivo. The coadministration of antibodies that neutralize the activities of the adhesion molecules E-selectin and ICAM-1 together with the IV H2O stimulus, each abolished the immediate effects of hemolysis on leukocyte recruitment in the microcirculation (supplemental Figure 3). Thus, we investigated whether HU can protect endothelial cells (HUVECs) from some of the effects of Hb in vitro. HUVECs were incubated with an Hb suspension (10 mg/mL for 4 hours) concomitantly with HU (100 µM). Hb slightly increased VCAM-1 expression (P > .05) and significantly augmented the expression of ICAM-1 and E-selectin on the HUVEC surface (Figure 7A-C). The presence of HU in cultures partially inhibited the effects of Hb on endothelial VCAM-1 and E-selectin expression. Cytokines released by HUVECs after treatments were also evaluated; Hb significantly intensified endothelial release of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and IL-8 (Figure 7D-F). Furthermore, the presence of HU slightly but significantly inhibited the release of MCP-1 and IL-8 by HUVECs.

HU reverses the effects of Hb on endothelial cell activation and neutrophil adhesion in vitro. The expression of adhesion molecules on the HUVEC surface was determined by flow cytometry after incubation with 10 mg/mL Hb in the presence or absence of HU (100 µM) or vehicle for 4 hours. (A) VCAM-1 (anti-CD106-fluorescein isothiocyanate), (B) ICAM-1 (anti-CD54- phycoerythrin), and (C) E-selectin (anti-CD62E-allophycocyanin); n = 9 assays. Cytokines in HUVEC-conditioned culture medium were quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; (D) MCP-1, (E) IL-6, and (F) IL-8; n = 4 to 14 assays. Adhesion of human neutrophils to ICAM-1 ligand (10 µg/mL) evaluated after incubation with autologous RBC lysate (Hb 1.5 mg/mL) in the presence or absence of HU (100 µM) (G) by static adhesion. After 5 minutes of treatment, neutrophil adhesion was quantified by using a colorimetric assay (n = 8 subjects), or (H) by using a microfluidic platform after 4 hours of treatment. For the microfluidic assay, neutrophil adhesion was quantified in a 400-µm-width channel with an applied shear stress of 0.5 dynes/cm2; data were analyzed by using a DucoCell analysis program, recording the mean number of neutrophils adhered to an area of 0.08 mm2 (n = 13 to 17 subjects). TNF-α (10 ng/mL) was used as a positive control. *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001 compared to basal without HU; #P < .05 and ##P < .01 compared with Hb or RBC lysate without HU.

HU reverses the effects of Hb on endothelial cell activation and neutrophil adhesion in vitro. The expression of adhesion molecules on the HUVEC surface was determined by flow cytometry after incubation with 10 mg/mL Hb in the presence or absence of HU (100 µM) or vehicle for 4 hours. (A) VCAM-1 (anti-CD106-fluorescein isothiocyanate), (B) ICAM-1 (anti-CD54- phycoerythrin), and (C) E-selectin (anti-CD62E-allophycocyanin); n = 9 assays. Cytokines in HUVEC-conditioned culture medium were quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; (D) MCP-1, (E) IL-6, and (F) IL-8; n = 4 to 14 assays. Adhesion of human neutrophils to ICAM-1 ligand (10 µg/mL) evaluated after incubation with autologous RBC lysate (Hb 1.5 mg/mL) in the presence or absence of HU (100 µM) (G) by static adhesion. After 5 minutes of treatment, neutrophil adhesion was quantified by using a colorimetric assay (n = 8 subjects), or (H) by using a microfluidic platform after 4 hours of treatment. For the microfluidic assay, neutrophil adhesion was quantified in a 400-µm-width channel with an applied shear stress of 0.5 dynes/cm2; data were analyzed by using a DucoCell analysis program, recording the mean number of neutrophils adhered to an area of 0.08 mm2 (n = 13 to 17 subjects). TNF-α (10 ng/mL) was used as a positive control. *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001 compared to basal without HU; #P < .05 and ##P < .01 compared with Hb or RBC lysate without HU.

Induction of neutrophil adhesion by RBC lysates is partially prevented by HU

Neutrophils from healthy individuals were isolated and incubated with autologous RBC lysate (1.5 mg/mL [Hb]) in the presence or absence of HU (100 µM), and their capacity to adhere to ICAM-1 was evaluated by using 2 assays: a static adhesion assay (5 minutes incubation with RBC lysate; Figure 7G) and a microfluidic adhesion assay (4 hours incubation with RBC lysate; Figure 7H). After 4 hours of incubation with RBC lysate, the adhesive properties of human neutrophils were significantly increased, whereas at 5 minutes, this increase was not significant. The presence of HU in cultures significantly diminished these RBC lysate–induced neutrophil adhesive properties.

Discussion

Under normal conditions, Hb is compartmentalized inside erythrocytes, where its primary function is to transport oxygen throughout the organism; however, under certain circumstances, and in a number of diseases such as SCD, the erythrocyte membrane is disrupted, and Hb is released into the plasma. If not neutralized immediately, CFHb reduces endothelial cell–derived NO bioavailability and is oxidized into methemoglobin (metHb) before releasing hemin,2,36 with significant pathophysiological consequences. Because hemolysis occurs exponentially over time during blood storage, CFHb also has potentially important implications for transfusion procedures, in addition to the known hazards of hemolytic transfusion reactions.9,37

New insights into the potent inflammatory effects of hemolytic products have emerged after reports that heme activates inflammasome formation in macrophages38 and induces neutrophil extracellular trap release in neutrophils of BERK SCD mice as well as TLR-4–mediated signaling in endothelial cells.11,12 In support of these data, we induced intravascular hemolysis in C57BL/6 mice, elevating CFHb to levels equivalent to those of a chimeric SCD mouse model (approximately 2.5-fold higher). In vivo imaging demonstrated that this hemolysis was associated with a rapid generation of systemic inflammation that was similar to the inflammation observed in TNF-α–stimulated mice and in nonmanipulated chimeric SCD mice. Furthermore, intravital microscopy showed that IV H2O–induced hemolysis in C57BL/6 mice was associated with augmented leukocyte recruitment in venules, similar to that observed in TNF-α–stimulated C57BL/6 mice, and previously reported to trigger vaso-occlusive events in BERK SCD mice.29 Consistent with the observation that IV H2O does not augment hemolysis in chimeric SCD mice, we did not see further increases in neutrophil recruitment or systemic inflammation in chimeric SCD mice after administration of H2O (data not shown). These findings probably reflect the decreased osmotic fragility of sickle RBCs39 and the fact that BERK SCD mice already demonstrate high levels of intravascular hemolysis.40

Although others have successfully demonstrated the direct inflammatory effects of hemin administration in vivo,11,12,38 we opted to use IV H2O administration to achieve RBC rupture with ensuing and measurable Hb release, as previously described,41 rather than administer the product of Hb processing (hemin) because the oxidation of Hb to metHb may constitute an important step in in vivo hemolysis. This approach effectively elevated CFHb and induced inflammation in C57BL/6 mice within 15 minutes of H2O administration. Although known to destabilize the erythrocyte membrane42 under the conditions used, hemin did not induce rapid hemolysis in either the C57BL/6 or the chimeric SCD mice.

Consumption of NO by CFHb to form metHb may constitute one of the major effects of intravascular hemolysis.8,20 We found that, in C57BL/6 mice, H2O-induced hemolysis was accompanied by rapid NO metabolite generation, indicative of NO consumption. Furthermore, the administration of another potent (nonheme) NO scavenger was able to induce inflammation similar to that of H2O-induced hemolysis. Additionally, the immediate inflammatory effects of H2O-induced hemolysis were abolished by haptoglobin, a scavenger of extracellular Hb, but not by hemopexin, a hemin scavenger, while the effects of hemin on leukocyte recruitment occurred over a longer time period, appearing to peak at about 2 hours after hemin administration. Of course these findings do not exclude a participation for heme in the immediate inflammatory effects of acute hemolysis, but they suggest that other more instantaneous effects, such as NO consumption and consequent reactive oxygen species production, may be more at play during the acute inflammation seen in the model that we used.

Thus, we hypothesized that restoration of NO could inhibit or reverse the rapid and potent immediate inflammatory effects of intravascular hemolysis. Accordingly, when an NO donor (DEANO) was administered together with H2O in C57BL/6 mice, we observed a significant inhibition of ensuing systemic inflammation and leukocyte recruitment and extravasation that was not mediated by changes in CFHb levels. Data indicate that the rapid release of NO afforded by DEANO within minutes of administration is able to spare the inflammatory effects of CFHb.

HU is commonly used for the treatment of SCD, among other hematologic and nonhematologic diseases14-16 in a chronic regime, because of its ability to increase levels of HbF and reduce platelet and leukocyte counts,17,19 with consequent clinical benefits for patients.43 However, HU may have important effects that are independent of HbF elevation, as this molecule can donate NO.44 Additionally, reports suggest that HU stimulates nitric oxide synthase activity and may provoke cGMP-dependent signaling in vivo by direct nitrosylation of the sGC enzyme.45-47 As NO bioavailability is apparently reduced in SCD patients,48 it is reasonable to assume that HU exerts some of its beneficial effects by improving NO bioavailability.21 In support of this hypothesis, we recently found that the administration of HU to BERK SCD mice, together with a cGMP-amplifying agent, abolished TNF-α–induced vaso-occlusive mechanisms and increased animal survival in an NO-dependent manner.28 In this study, administering HU to C57BL/6 mice at the time of hemolytic induction inhibited ensuing systemic inflammatory processes and leukocyte recruitment without altering plasma CFHb levels. HU was also administered to H2O-induced hemolytic C57BL/6 mice at the same time as NO-signaling modulating agents. Accordingly, the effects of HU administration on hemolytic vascular inflammation in C57BL/6 mice were abrogated in the presence of an NO scavenger and an sGC inhibitor indicating that, in this model, HU exerts these anti-inflammatory effects via an NO/cGMP-dependent pathway, possibly via the generation of intravascular NO. Although the anti-inflammatory effects of HU observed herein are consistent with the idea that the acute hemolytic inflammation generated in this model may occur via rapid NO consumption, the possibility that stimulation of NO/cGMP-dependent signaling by HU exerts a protective effect rather than an abrogating effect in this setting should not be overlooked.

Hemolysis-induced leukocyte recruitment in vivo was found to be dependent on endothelial E-selectin and ICAM-1 activity. To clarify whether HU exerts effects via modulation of cellular mechanisms, in vitro assays were used to determine the direct effects of Hb on endothelial cell activation and leukocyte adhesive properties. Significant effects of Hb were observed in vitro after a longer time frame of 4 hours compared with the induction of inflammation by hemolysis in vivo, which occurred within just 15 minutes. Because in vitro Hb preparations are rapidly oxidized in air, the in vitro effects observed were likely mediated by metHb/hemin. Hb increased the expression of adhesion molecules involved in leukocyte recruitment on the surface of HUVECs and significantly induced their secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, indicating an activation of cells to a proinflammatory phenotype. In the presence of HU, these alterations were slightly but significantly abrogated. Additionally, Hb acquired from autologous RBC lysis induced neutrophil adhesion to ICAM-1, and the presence of HU effectively reduced this induction of neutrophil adhesion. Although in vivo data indicate that the ability of HU to abrogate hemolytic inflammation may primarily be the result of its ability to counteract the immediate depletion of NO by Hb, HU may also diminish the subsequent effects that Hb has on leukocyte and endothelial activation, potentially reducing the ability of the endothelium to capture and tether leukocytes in response to Hb or its products and reducing the subsequent ability of neutrophils to firmly adhere to endothelial ICAM-1.49-51 Given that ongoing clinical trials demonstrate potential for the use of pan-selectin inhibitors for ameliorating leukocyte adhesive interactions in SCD,52 the use of HU in combination with this approach should be explored.

In summary, induction of hemolysis in C57BL/6 mice to levels similar to those seen at baseline in chimeric SCD mice triggers a rapid systemic and vascular inflammatory response, possibly mediated by vascular NO consumption. Such an acute inflammatory response is likely to play an important role in the pathophysiology of hemolytic reactions and diseases, including SCD, with significant clinical consequences. Acute administration of HU at the time of the hemolytic assault abolished the effects of CFHb on systemic and vascular inflammation via activation of an NO/cGMP signaling pathway. HU may exert its immediate beneficial effects by restoring vascular Hb-scavenged NO in addition to diminishing endothelial activation and leukocyte adhesive interactions induced by Hb products. In addition to providing evidence that HU may hold potential for countering hemolytic inflammation in diverse disorders, this study further highlights perspectives for the use of HU as an acute treatment of SCD,53 an approach that could have major clinical implications.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. John Belcher, University of Minnesota, for assistance with methodology for plasma hemoglobin determination. We also thank CEMIB (Centro Multidisciplinar para Investigação Biológica na Área de Ciência em Animais de Laboratório), the Instituto de Pesquisas Energéticas Nucleares, São Paulo, Brazil, and Drs. Flávia R. Pallis and Carla F. Penteado for support with animal procedures.

This work was supported by grants No. 2008/50582-3 and 11/50959-7 (C.B.A.) from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, and grants No. 565036/2010 and 307784/2013-4 (C.C.W.) from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico.

Authorship

Contribution: C.B.A. and N.C. conceived and designed the study, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; C.B.A. also performed experiments; L.E.B.S. performed and analyzed in vivo imaging system experiments; F.C.L. performed in vitro experiments; and F.T.M.C., C.C.W., D.T.C., and F.F.C. participated in study design and revised and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Nicola Conran, Hemocentro, Rua Carlos Chagas 480, Cidade Universitária, 13083-878 SP, Campinas SP, Brazil; e-mail: conran@unicamp.br.