Key Points

AMKL patients in 2000 to 2009 had better survival than those in 1989 to 1999, but outcomes for patients in 2000 to 2004 and 2005 to 2009 were comparable.

Heterogeneous cytogenetic groups can be classified into good, intermediate, and poor risk on the basis of prognosis.

Abstract

Comprehensive clinical studies of patients with acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (AMKL) are lacking. We performed an international retrospective study on 490 patients (age ≤18 years) with non–Down syndrome de novo AMKL diagnosed from 1989 to 2009. Patients with AMKL (median age 1.53 years) comprised 7.8% of pediatric AML. Five-year event-free (EFS) and overall survival (OS) were 43.7% ± 2.7% and 49.0% ± 2.7%, respectively. Patients diagnosed in 2000 to 2009 were treated with higher cytarabine doses and had better EFS (P = .037) and OS (P = .003) than those diagnosed in 1989 to 1999. Transplantation in first remission did not improve survival. Cytogenetic data were available for 372 (75.9%) patients: hypodiploid (n = 18, 4.8%), normal karyotype (n = 49, 13.2%), pseudodiploid (n = 119, 32.0%), 47 to 50 chromosomes (n = 142, 38.2%), and >50 chromosomes (n = 44, 11.8%). Chromosome gain occurred in 195 of 372 (52.4%) patients: +21 (n = 106, 28.5%), +19 (n = 93, 25.0%), +8 (n = 77, 20.7%). Losses occurred in 65 patients (17.5%): –7 (n = 13, 3.5%). Common structural chromosomal aberrations were t(1;22)(p13;q13) (n = 51, 13.7%) and 11q23 rearrangements (n = 38, 10.2%); t(9;11)(p22;q23) occurred in 21 patients. On the basis of frequency and prognosis, AMKL can be classified to 3 risk groups: good risk—7p abnormalities; poor risk—normal karyotypes, –7, 9p abnormalities including t(9;11)(p22;q23)/MLL-MLLT3, –13/13q-, and –15; and intermediate risk—others including t(1;22)(p13;q13)/OTT-MAL (RBM15-MKL1) and 11q23/MLL except t(9;11). Risk-based innovative therapy is needed to improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

Acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (AMKL) occurs predominantly in children and comprises as much as 10% of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cases.1-4 AMKL blasts show cytoplasmic blebs and are immunophenotypically positive for CD41, CD42b, and CD61. However, the diagnosis of AMKL may be difficult because of myelofibrosis and manifestation as extramedullary disease.

AMKL is characterized by various chromosomal abnormalities that are frequently associated with complex karyotypes and hyperdiploidy.5 A study of 30 children and 23 adults with AMKL described 9 cytogenetic subgroups: (1) normal karyotypes; (2) Down syndrome (DS); (3) numerical abnormalities only; (4) t(1;22)(p13;q13)/OTT-MAL (RBM15-MKL1); (5) t(9;22)(q34;q11.2); (6) 3q21q26; (7) –5/5q-, –7/7q-, or both; (8) i(12)(p10); and (9) other structural changes.4 Groups 1 through 4 were mostly seen in children and groups 5 through 8 mainly in adults. AMKL is the most frequent form of AML in young children (<4 years) with DS, which is currently recognized as a distinct form of leukemia (myeloid leukemia associated with Down syndrome) in the 2008 World Health Organization (WHO) classification and has an excellent prognosis.6,7 It is often preceded by the transient myeloproliferative disorder (TMD), and GATA1 mutations are detected in nearly all patients. In children with non-DS AMKL, numerical chromosomal abnormalities, especially +8, +19, and +21, are commonly seen.1-3 The t(1;22)(p13;q13) is restricted to AMKL and observed in non-DS infants.4

Among patients with AMKL treated at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (St. Jude), non-DS patients (n = 28) had a significantly worse 2-year event-free survival (EFS) (14%) than DS patients (n = 6, 83%).1 Similarly, 53 children with AMKL treated on the CCG2891 protocol had a 5-year EFS of 22.5%.8 However, the Japanese groups reported a 10-year EFS of 57% for children with non-DS AMKL (n = 21),2 and the Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster (BFM) AML04 study reported improvement in 5-year EFS (n = 60; 54%).9 The BFM group attributed this improvement to the higher cumulative dosage of cytarabine (48-fold) and anthracyclines (1.2- to 1.6-fold) in the BFM93/98 protocols than the BFM87 study.3 However, the benefit of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) remains contradictory. Patients with non-DS AMKL had significantly better 2-year EFS after allo-HSCT (26%) than after chemotherapy alone (0%) in a St. Jude study,1 and the European Group for Blood and Bone Marrow Transplantation study reported a 3-year leukemia-free survival of 66% after allo-HSCT (n = 19) in children with AMKL, although this study included DS patients.10 However, the BFM and Japanese studies did not document a benefit of allo-HSCT.2,3,9 The prognostic impact of cytogenetically defined subgroups in AMKL has not yet been clearly defined, except in a St. Jude AML02 multicenter study in which EFS and overall survival (OS) for patients with AMKL and t(1;22) (n = 5) were better than for those with AMKL without t(1;22) (n = 21).11,12

All previous studies on AMKL were conducted on small numbers of patients. Herein, we conducted an international, large-scale retrospective study of children with non-DS AMKL diagnosed in 1989 to 2009 to analyze clinical features and survival rates by cytogenetic subgroups.

Patients and methods

Patients

De-identified data on pediatric patients with AMKL were collected from 19 members of the international BFM (I-BFM) Study Group (supplemental Table 1). Inclusion criteria were age 0 to 18 years, de novo AMKL, and diagnosis between January 1, 1989 and December 31, 2009. AMKL was diagnosed according to the following criteria: expression of the megakaryocytic antigen profile in leukemia blasts by flow cytometry (CD41, CD42b, or CD61) or immunohistochemistry (CD42b, CD61, CD31, or Factor VIII) or detection of platelet peroxidase activity by electron microscopy. Exclusion criteria were AMKL as secondary malignancy; previous chemotherapy or radiotherapy for malignant disease; and DS-associated AMKL including mosaicism. Records were studied for clinical features at initial diagnosis, treatment including HSCT, and events during follow-up. Treatment protocols were administered in accordance with local laws and guidelines and approved by institutional review boards of participating centers. Informed consent was obtained from patients’ parents or legal guardians in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Cytogenetic analysis

Submitted karyotypes were centrally reviewed by a cytogeneticist, using standard nomenclature according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature 2009.13 A successful karyotype required at least 20 fully analyzed metaphases, except when clonal abnormalities were clearly identified. Patients with ≥3 aberrations were considered as having a complex karyotype.

Statistical analyses

Complete remission (CR) was defined as bone marrow with <5% blasts and evidence of regeneration of normal hematopoietic cells. EFS was defined as time from diagnosis to first event, including failure to achieve remission, relapse, secondary malignancy, or death from any cause. Patients who did not achieve CR were considered to have an event at time zero. OS was calculated from diagnosis to death from any cause. Early death was defined when the event occurred within 30 days from diagnosis. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate 5-year probabilities of EFS and OS,14 and survival distributions between groups were compared by the log-rank test.15

All P values were two-tailed. Multivariable Cox regression analyses using variables with P ≤ .1 in univariate analysis were performed on EFS and OS. Backward selection was used to assess variables with an independent significant effect at a significance level of .05 in the final model.

Results

Patient characteristics

The study included 490 patients with AMKL (Table 1), which comprises 7.8% of pediatric patients with AML treated by members of the I-BFM study group. At diagnosis, the median age was 1.53 years (range, 0.01-16.47), median white blood cell count was 12.0 × 109/L (range, 0.6-188.0 × 109/L); males and females were equally represented. Extramedullary disease was recorded in 69 (14.1%) patients: 23 central nervous system (CNS), 13 lymph nodes, 11 skin, 10 bone, 7 orbit/sinus, 4 gonad, and 9 not specified. Multiple treatment protocols were used by participating groups (supplemental Table 2). When doses of cytarabine, anthracycline, and etoposide were calculated in treatment protocols for patients during the period 1989 to 2009, both 1989 to 1999 and 2000 to 2009, and 2000 to 2009, the regimen used in 2000 to 2009 had higher mean doses of cytarabine and etoposide in the first 2 courses and higher mean doses of cytarabine in the entire treatment course than those in the other 2 eras. Some of the protocols in 2000 to 2009 limited the use of allo-HSCT to patients at high risk or those with poor response to initial treatment.

Patient characteristics and outcomes

| . | Patients . | 5-y EFS (%) . | P . | 5-y OS (%) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 490 | 43.7 ± 2.7 | 49.0 ± 2.7 | ||

| Median age, y (range) | 1.53 (0.01-16.47) | .266 | .491 | ||

| <1.53, n (%) | 245 (50.0) | 41.5 ± 3.7 | 48.1 ± 3.7 | ||

| ≥1.53, n (%) | 245 (50.0) | 46.0 ± 3.8 | 49.8 ± 3.9 | ||

| Sex | .637 | .621 | |||

| Female, n (%) | 247 (50.4) | 45.4 ± 3.8 | 50.3 ± 3.8 | ||

| Male, n (%) | 243 (49.6) | 42.0 ± 3.7 | 47.6 ± 3.8 | ||

| Year of diagnosis | .037 | .003 | |||

| 1989-1999, n (%) | 165 (33.7) | 38.6 ± 3.9 | 41.0 ± 3.9 | ||

| 2000-2009, n (%) | 325 (66.3) | 46.5 ± 3.5 | 53.0 ± 3.6 | ||

| Median WBC count, × 109/L (range)* | 12.0 (0.6-188.0) | .548 | .726 | ||

| <20 × 109/L, n (%) | 356 (73.9) | 44.5 ± 3.1 | 49.5 ± 3.1 | ||

| 20-100 × 109/L, n (%) | 121 (25.1) | 43.0 ± 5.3 | 48.4 ± 5.6 | ||

| ≥100 × 109/L, n (%) | 5 (1.0) | 20.0 ± 12.6¶ | 30.0 ± 17.7 | ||

| Median PB blasts, % (range)† | 12 (0-93) | .594 | .724 | ||

| Less than median, n (%) | 206 | 44.8 ± 4.1 | 48.4 ± 4.2 | ||

| At least median, n (%) | 224 | 44.3 ± 3.8 | 49.0 ± 3.9 | ||

| Median BM blasts, % (range)‡ | 41 (0-98) | .120 | .270 | ||

| Less than median, n (%) | 213 | 48.1 ± 4.1 | 52.2 ± 4.1 | ||

| At least median, n (%) | 215 | 40.2 ± 4.1 | 45.6 ± 4.3 | ||

| CNS involvement§ | .740 | .264 | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 23 (4.9) | 38.6 ± 10.1 | 38.3 ± 10.0 | ||

| No, n (%) | 445 (95.1) | 44.4 ± 2.8 | 50.0 ± 2.9 | ||

| Cytogenetics | .965 | .753 | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 372 (75.9) | 44.0 ± 3.1 | 48.7 ± 3.2 | ||

| No, n (%) | 118 (24.1) | 42.9 ± 5.0 | 50.0 ± 5.2 |

| . | Patients . | 5-y EFS (%) . | P . | 5-y OS (%) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 490 | 43.7 ± 2.7 | 49.0 ± 2.7 | ||

| Median age, y (range) | 1.53 (0.01-16.47) | .266 | .491 | ||

| <1.53, n (%) | 245 (50.0) | 41.5 ± 3.7 | 48.1 ± 3.7 | ||

| ≥1.53, n (%) | 245 (50.0) | 46.0 ± 3.8 | 49.8 ± 3.9 | ||

| Sex | .637 | .621 | |||

| Female, n (%) | 247 (50.4) | 45.4 ± 3.8 | 50.3 ± 3.8 | ||

| Male, n (%) | 243 (49.6) | 42.0 ± 3.7 | 47.6 ± 3.8 | ||

| Year of diagnosis | .037 | .003 | |||

| 1989-1999, n (%) | 165 (33.7) | 38.6 ± 3.9 | 41.0 ± 3.9 | ||

| 2000-2009, n (%) | 325 (66.3) | 46.5 ± 3.5 | 53.0 ± 3.6 | ||

| Median WBC count, × 109/L (range)* | 12.0 (0.6-188.0) | .548 | .726 | ||

| <20 × 109/L, n (%) | 356 (73.9) | 44.5 ± 3.1 | 49.5 ± 3.1 | ||

| 20-100 × 109/L, n (%) | 121 (25.1) | 43.0 ± 5.3 | 48.4 ± 5.6 | ||

| ≥100 × 109/L, n (%) | 5 (1.0) | 20.0 ± 12.6¶ | 30.0 ± 17.7 | ||

| Median PB blasts, % (range)† | 12 (0-93) | .594 | .724 | ||

| Less than median, n (%) | 206 | 44.8 ± 4.1 | 48.4 ± 4.2 | ||

| At least median, n (%) | 224 | 44.3 ± 3.8 | 49.0 ± 3.9 | ||

| Median BM blasts, % (range)‡ | 41 (0-98) | .120 | .270 | ||

| Less than median, n (%) | 213 | 48.1 ± 4.1 | 52.2 ± 4.1 | ||

| At least median, n (%) | 215 | 40.2 ± 4.1 | 45.6 ± 4.3 | ||

| CNS involvement§ | .740 | .264 | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 23 (4.9) | 38.6 ± 10.1 | 38.3 ± 10.0 | ||

| No, n (%) | 445 (95.1) | 44.4 ± 2.8 | 50.0 ± 2.9 | ||

| Cytogenetics | .965 | .753 | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 372 (75.9) | 44.0 ± 3.1 | 48.7 ± 3.2 | ||

| No, n (%) | 118 (24.1) | 42.9 ± 5.0 | 50.0 ± 5.2 |

BM, bone marrow; CNS, central nervous system; EFS, event-free survival; OS, overall survival; PB, peripheral blood; WBC, white blood cell.

n = 482.

n = 430.

n = 428.

n = 468.

3-year rate.

Median follow-up time for the 239 survivors was 6.46 years (range, 0.52-20.20). CR was achieved in 417 (85.1%) patients. Of the 206 (42.0%) patients who received allo-HSCT, 113 (23.1%) were in first CR, 45 (9.2%) in second CR, 40 (8.2%) had evidence of residual disease, and information was missing for 8 patients. Significantly more patients received allo-HSCT in 2000 to 2009 (n = 155) than in 1989 to 1999 (n = 51; P < .001).

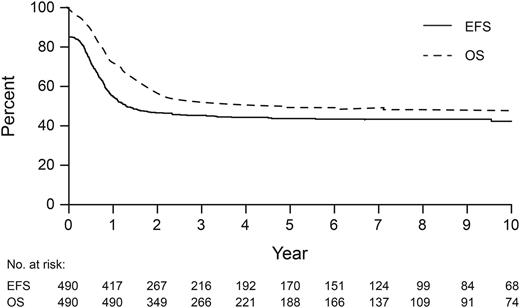

The 5-year EFS and OS of the 490 patients were 43.7% ± 2.7% and 49.0% ± 2.7%, respectively (Figure 1). Of 246 deaths, 150 were caused by relapse, 52 by primary refractory disease, 32 during first CR (17 infection, 12 HSCT-related, 1 each to secondary solid tumor, accident, and not specified), and 12 were early deaths (6 infection, 3 hemorrhage, 1 disease progression, and 2 not specified). Patients diagnosed in 2000 to 2009 had better EFS (46.5% ± 3.5%, P = .037) and OS (53.0% ± 3.6%, P = .003) than those diagnosed in 1989 to 1999 (38.6% ± 3.9% and 41.0% ± 3.9%, respectively) (Table 1 and supplemental Figure 1A-B). However, EFS and OS for patients diagnosed in 2005 to 2009 were not different from those diagnosed in 2000 to 2004 (supplemental Figure 1C-D). The EFS and OS for patients who did (n = 113, 56.8% ± 5.1% and 58.1% ± 5.1%) or did not receive allo-HSCT in first CR (n = 298, 50.2% ± 3.5% and 55.2% ± 3.5%) were not significantly different (supplemental Figure 2A-B). OS after transplant was significantly better for patients receiving allo-HSCT in first CR (58.0% ± 5.3%) than those receiving it in second CR (27.6% ± 7.8%) or those with evidence of residual disease (19.3% ± 8.7%) (P < .001, supplemental Table 3). The OS of children transplanted in first CR or second CR was not influenced by the treatment period. However, patients who received allo-HSCT with evidence of residual disease in 2000 to 2009 had significantly better OS (28.6 ± 12.1%) than those receiving it in 1989 to 1999 (0.0%) (P = .002, supplemental Table 3). There were no associations between extramedullary or CNS disease and EFS or OS. Two patients developed second malignancies: B-lymphoblastic leukemia (n = 1) and solid tumor (n = 1, details unknown).

Event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) for 490 patients with acute megakaryoblastic leukemia.

Event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) for 490 patients with acute megakaryoblastic leukemia.

Cytogenetic analysis

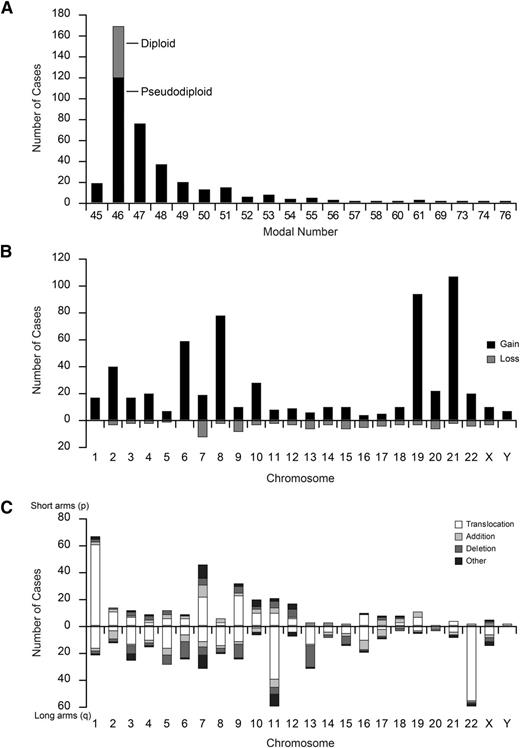

Of the 490 patients, cytogenetic data were available for 372 (75.9%) (Table 1). The remaining 118 patients were not evaluated for different reasons (24 with normal karyotype but <20 analyzed metaphases, 26 for whom cytogenetic description of the abnormality was incomplete, and 68 for whom information was not available). Compared with patients for whom cytogenetic data were not available, patients for whom data were available had higher initial white blood cell (WBC) counts and were more frequently diagnosed in 2000 to 2009 (supplemental Table 4). Among 372 evaluable patients, modal number analysis showed hypodiploidy (n = 18, 4.8%), normal karyotype (n = 49, 13.2%), pseudodiploidy (n = 119, 32.0%), 47 to 50 chromosomes (n = 142, 38.2%), and >50 chromosomes (n = 44, 11.8%) (Figure 2A and Table 2). Among 323 patients with chromosomal aberrations, 45 (13.9%) had numerical aberrations only, 94 (29.1%) had structural aberrations only, and 184 (57.0%) had both. Of 371 evaluable patients, 181 (48.8%) had complex karyotypes (Table 2).

Distribution of modal number and frequency (number of cases) of numerical and structural cytogenetic abnormalities. (A) Cases in gray among modal number 46 represent normal karyotype (n = 49), and those in black represent pseudodiploid chromosomes (n = 119). (B) Gains are shown on the positive y-axis and losses on the negative y-axis. Chromosomes are shown on the x-axis. (C) The short arms (p) of the chromosomes are shown on the positive y-axis and the long arms (q) on the negative y-axis.

Distribution of modal number and frequency (number of cases) of numerical and structural cytogenetic abnormalities. (A) Cases in gray among modal number 46 represent normal karyotype (n = 49), and those in black represent pseudodiploid chromosomes (n = 119). (B) Gains are shown on the positive y-axis and losses on the negative y-axis. Chromosomes are shown on the x-axis. (C) The short arms (p) of the chromosomes are shown on the positive y-axis and the long arms (q) on the negative y-axis.

Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients by cytogenetic subgroup

| Chromosome modal number and complexity* . | N (%) . | Age at diagnosis (y) . | Sex . | 5-y EFS . | 5-y OS . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (range) . | P . | Female: N (%) . | P . | EFS ± SE (%) . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | OS ± SE (%) . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | ||

| Modal number | .003 | .141 | .077 | .002 | |||||||

| Normal karyotype | 49 (13.2) | 1.45 (0.10-15.46) | 21 (42.9) | 27.3 ± 7.8 | 26.4 ± 7.5 | ||||||

| Hypodiploid (≤45) | 18 (4.8) | 2.97 (0.39-15.01) | 11 (61.1) | 27.8 ± 10.6 | 1.039 (0.550-1.964) | 33.3 ± 11.1 | 1.009 (0.523 - 1.944) | ||||

| Pseudodiploid (46) | 119 (32.0) | 1.20 (0.03-13.63) | 66 (55.5) | 41.2 ± 5.7 | 0.860 (0.573-1.291) | 44.8 ± 5.6 | 0.745 (0.493 - 1.126) | ||||

| 47-50 chromosomes | 142 (38.2) | 1.73 (0.08-15.29) | 66 (46.5) | 51.4 ± 5.0 | 0.614 (0.408-0.924) | 58.9 ± 5.0 | 0.463 (0.303 - 0.707) | (<.001) | |||

| >50 chromosomes | 44 (11.8) | 1.66 (0.62-6.54) | 28 (63.6) | 52.3 ± 8.3 | 0.653 (0.380-1.123) | 56.6 ± 8.3 | 0.520 (0.297 - 0.911) | (.022) | |||

| Complexity | .161 | .243 | .361 | .031 | |||||||

| 1 aberration | 92 (24.7) | 1.28 (0.03-15.29) | 55 (59.8) | 42.6 ± 6.2 | 0.833 (0.543-1.277) | 47.2 ± 6.2 | 0.705 (0.456 - 1.092) | ||||

| 2 aberrations | 49 (13.2) | 1.96 (0.13-11.69) | 26 (53.1) | 44.3 ± 8.3 | 0.768 (0.464-1.269) | 52.0 ± 8.5 | 0.612 (0.361 - 1.036) | (.067) | |||

| 3 aberrations | 32 (8.6) | 1.57 (0.41-15.01) | 15 (46.9) | 45.0 ± 10.6 | 0.735 (0.411-1.312) | 44.3 ± 10.5 | 0.679 (0.380 - 1.213) | ||||

| 4 aberrations | 40 (10.8) | 1.55 (0.10-4.90) | 16 (40.0) | 55.0 ± 9.2 | 0.558 (0.316-0.986) | 66.7 ± 8.8 | 0.371 (0.196 - 0.703) | (.002) | |||

| ≥5 aberrations | 109 (29.3) | 1.51 (0.25-11.32) | 59 (54.1) | 48.4 ± 5.6 | 0.680 (0.445-1.038) | 53.7 ± 5.8 | 0.549 (0.355 - 0.848) | (.007) | |||

| Chromosome modal number and complexity* . | N (%) . | Age at diagnosis (y) . | Sex . | 5-y EFS . | 5-y OS . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (range) . | P . | Female: N (%) . | P . | EFS ± SE (%) . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | OS ± SE (%) . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | ||

| Modal number | .003 | .141 | .077 | .002 | |||||||

| Normal karyotype | 49 (13.2) | 1.45 (0.10-15.46) | 21 (42.9) | 27.3 ± 7.8 | 26.4 ± 7.5 | ||||||

| Hypodiploid (≤45) | 18 (4.8) | 2.97 (0.39-15.01) | 11 (61.1) | 27.8 ± 10.6 | 1.039 (0.550-1.964) | 33.3 ± 11.1 | 1.009 (0.523 - 1.944) | ||||

| Pseudodiploid (46) | 119 (32.0) | 1.20 (0.03-13.63) | 66 (55.5) | 41.2 ± 5.7 | 0.860 (0.573-1.291) | 44.8 ± 5.6 | 0.745 (0.493 - 1.126) | ||||

| 47-50 chromosomes | 142 (38.2) | 1.73 (0.08-15.29) | 66 (46.5) | 51.4 ± 5.0 | 0.614 (0.408-0.924) | 58.9 ± 5.0 | 0.463 (0.303 - 0.707) | (<.001) | |||

| >50 chromosomes | 44 (11.8) | 1.66 (0.62-6.54) | 28 (63.6) | 52.3 ± 8.3 | 0.653 (0.380-1.123) | 56.6 ± 8.3 | 0.520 (0.297 - 0.911) | (.022) | |||

| Complexity | .161 | .243 | .361 | .031 | |||||||

| 1 aberration | 92 (24.7) | 1.28 (0.03-15.29) | 55 (59.8) | 42.6 ± 6.2 | 0.833 (0.543-1.277) | 47.2 ± 6.2 | 0.705 (0.456 - 1.092) | ||||

| 2 aberrations | 49 (13.2) | 1.96 (0.13-11.69) | 26 (53.1) | 44.3 ± 8.3 | 0.768 (0.464-1.269) | 52.0 ± 8.5 | 0.612 (0.361 - 1.036) | (.067) | |||

| 3 aberrations | 32 (8.6) | 1.57 (0.41-15.01) | 15 (46.9) | 45.0 ± 10.6 | 0.735 (0.411-1.312) | 44.3 ± 10.5 | 0.679 (0.380 - 1.213) | ||||

| 4 aberrations | 40 (10.8) | 1.55 (0.10-4.90) | 16 (40.0) | 55.0 ± 9.2 | 0.558 (0.316-0.986) | 66.7 ± 8.8 | 0.371 (0.196 - 0.703) | (.002) | |||

| ≥5 aberrations | 109 (29.3) | 1.51 (0.25-11.32) | 59 (54.1) | 48.4 ± 5.6 | 0.680 (0.445-1.038) | 53.7 ± 5.8 | 0.549 (0.355 - 0.848) | (.007) | |||

| Representative chromosome subgroups† . | N (%) . | Age at diagnosis (y) . | Sex . | 5-y EFS . | 5-y OS . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (range) . | P . | Female: N (%) . | P . | EFS ± SE (%) . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | OS ± SE (%) . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | ||

| Normal karyotype | 49 (13.2) | 1.45 (0.10-15.46) | 21 (42.9) | 27.3 ± 7.8 | 1.376 (0.956-1.981) | .086 | 26.4 ± 7.5 | 1.688 (1.167-2.441) | .005 | ||

| Trisomy 1 | 16 (4.3) | 1.13 (0.79-2.70) | 10 (62.5) | 25.0 ± 10.8 | 1.645 (0.918-2.948) | .095 | 25.0 ± 10.8 | 1.789 (0.996-3.213) | .051 | ||

| t(1;22)(p13;q13) | 51 (13.7) | 0.55 (0.03-6.25) | < .001 | 33 (64.7) | .050 | 54.5 ± 8.0 | 0.813 (0.531-1.244) | 58.2 ± 7.7 | 0.811 (0.519-1.265) | ||

| t(1;22), balanced only | 38 (10.2) | 0.39 (0.03-1.81) | < .001 | 25 (65.8) | .086 | 63.2 ± 9.0 | 0.660 (0.390-1.116) | 68.2 ± 8.4 | 0.632 (0.360-1.112) | ||

| t(1;22), unbalanced | 13 (3.5) | 1.13 (0.79-6.25) | 8 (61.5) | 30.8 ± 12.8 | 1.329 (0.682-2.593) | 30.8 ± 12.8 | 1.369 (0.701-2.675) | ||||

| Abnormality in 3q21q26 | 14 (3.8) | 1.61 (0.70-10.72) | 3 (21.4) | .028 | 64.3 ± 12.8 | 0.518 (0.213-1.259) | 64.3 ± 12.8 | 0.588 (0.242-1.430) | |||

| Deletion of 5q | 7 (1.9) | 2.43 (1.66-8.20) | .026 | 2 (28.6) | 57.1 ± 21.6 | 0.635 (0.203-1.985) | 64.3 ± 22.2 | 0.424 (0.105-1.708) | |||

| Trisomy 6 | 58 (15.6) | 1.28 (0.18-8.20) | 33 (56.9) | 39.2 ± 7.9 | 1.167 (0.811-1.679) | 50.1 ± 8.1 | 0.962 (0.643-1.437) | ||||

| Monosomy 7 | 13 (3.5) | 4.17 (0.39-15.01) | .006 | 6 (46.2) | 15.4 ± 10.0 | 1.924 (1.047-3.534) | .035 | 23.1 ± 11.7 | 2.276 (1.202-4.309) | .012 | |

| Abnormality of 7p | 43 (11.6) | 1.77 (0.51-8.20) | 19 (44.2) | 74.1 ± 8.0 | 0.350 (0.191-0.642) | .001 | 76.7 ± 7.9 | 0.307 (0.157-0.599) | .001 | ||

| Abnormality of 7q | 31 (8.3) | 1.99 (0.70-4.85) | .031 | 13 (41.9) | 63.5 ± 11.1 | 0.501 (0.273-0.919) | .026 | 67.0 ± 10.7 | 0.452 (0.231-0.883) | .020 | |

| Trisomy 8 | 77 (20.7) | 1.66 (0.25-15.29) | 41 (53.2) | 51.4 ± 6.2 | 0.774 (0.542-1.104) | 59.0 ± 6.3 | 0.681 (0.463-1.001) | .051 | |||

| Abnormality of 8q | 20 (5.4) | 1.55 (0.76-11.28) | 8 (40.0) | 64.0 ± 11.6 | 0.557 (0.262-1.184) | 71.4 ± 11.5 | 0.431 (0.177-1.048) | .063 | |||

| Abnormality of 9p, other than t(9;11) | 9 (2.4) | 2.10 (1.12-4.90) | .046 | 6 (66.7) | 22.2 ± 11.3 | 1.979 (0.930-4.208) | .076 | 22.2 ± 11.3 | 2.553 (1.198-5.438) | .015 | |

| Abnormality of 9q | 23 (6.2) | 1.78 (0.66-13.62) | .052 | 11 (47.8) | 52.2 ± 12.0 | 0.755 (0.411-1.385) | 59.2 ± 12.6 | 0.730 (0.374-1.425) | |||

| Trisomy 10 | 27 (7.3) | 1.77 (0.18-8.20) | 15 (55.6) | 55.3 ± 10.7 | 0.681 (0.380-1.221) | 64.2 ± 10.7 | 0.537 (0.275-1.050) | .069 | |||

| Abnormality of 11p | 18 (4.8) | 1.41 (0.18-12.58) | 10 (55.6) | 27.8 ± 10.6 | 1.605 (0.915-2.817) | .099 | 37.0 ± 12.0 | 1.368 (0.744-2.516) | |||

| Abnormality of 11q | 57 (15.3) | 1.83 (0.48-13.63) | .083 | 30 (52.6) | 34.9 ± 7.3 | 1.362 (0.955-1.945) | .088 | 39.7 ± 7.5 | 1.309 (0.902-1.898) | ||

| Abnormality of 11q23 | 38 (10.2) | 1.77 (0.59-13.63) | 21 (55.3) | 28.5 ± 9.1 | 1.632 (1.088-2.447) | .018 | 32.4 ± 9.4 | 1.548 (1.015-2.360) | .043 | ||

| t(9;11)(p22;q23) | 21 (5.6) | 1.41 (0.72-3.98) | 10 (47.6) | 17.1 ± 7.8 | 1.929 (1.173-3.171) | .010 | 17.1 ± 7.8 | 2.130 (1.292-3.514) | .003 | ||

| Other 11q23 | 17 (4.6) | 2.05 (0.59-13.63) | 11 (64.7) | 41.2 ± 15.8 | 1.223 (0.648-2.309) | 52.9 ± 16.2 | 0.932 (0.459-1.892) | ||||

| Abnormality of 12p | 16 (4.3) | 1.45 (0.84-8.54) | 6 (37.5) | 31.2 ± 13.0 | 1.197 (0.652-2.197) | 47.4 ± 15.4 | 1.110 (0.546-2.253) | ||||

| Monosomy 13 | 7 (1.9) | 1.12 (0.65-11.32) | 6 (85.7) | NA‡ | 3.433 (1.514-7.784) | .003 | 28.6 ± 17.1 | 2.202 (0.904-5.360) | .082 | ||

| Deletion of 13q | 16 (4.3) | 1.50 (0.56-4.90) | 5 (31.3) | 18.8 ± 9.8 | 1.850 (1.054-3.245) | .032 | 29.2 ± 12.3 | 1.805 (0.980-3.322) | .058 | ||

| Monosomy 15 | 7 (1.9) | 1.17 (0.81-2.04) | 5 (71.4) | 14.3 ± 9.4 | 2.914 (1.289-6.586) | .010 | 14.3 ± 9.4 | 2.133 (0.946-4.809) | .068 | ||

| Trisomy 19 | 93 (25.0) | 1.44 (0.25-6.54) | 41 (44.1) | .096 | 48.3 ± 5.8 | 0.903 (0.654-1.248) | 52.9 ± 5.9 | 0.898 (0.638-1.263) | |||

| Trisomy 21 | 106 (28.5) | 1.72 (0.08-8.20) | 48 (45.3) | 47.9 ± 5.8 | 0.882 (0.648-1.200) | 52.7 ± 5.9 | 0.803 (0.579-1.113) | ||||

| Abnormality of Xq | 15 (4.0) | 1.39 (0.48-7.32) | 9 (60.0) | 20.0 ± 8.9 | 1.796 (1.002-3.218) | .049 | 32.0 ± 11.8 | 1.498 (0.792-2.833) | |||

| Chromosome 49-65, numerical or structural | 52 (14.0) | 1.41 (0.49-6.54) | 25 (48.1) | 59.6 ± 7.3 | 0.631 (0.402-0.991) | .046 | 64.8 ± 7.1 | 0.588 (0.362-0.956) | .032 | ||

| Representative chromosome subgroups† . | N (%) . | Age at diagnosis (y) . | Sex . | 5-y EFS . | 5-y OS . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (range) . | P . | Female: N (%) . | P . | EFS ± SE (%) . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | OS ± SE (%) . | HR (95% CI) . | P . | ||

| Normal karyotype | 49 (13.2) | 1.45 (0.10-15.46) | 21 (42.9) | 27.3 ± 7.8 | 1.376 (0.956-1.981) | .086 | 26.4 ± 7.5 | 1.688 (1.167-2.441) | .005 | ||

| Trisomy 1 | 16 (4.3) | 1.13 (0.79-2.70) | 10 (62.5) | 25.0 ± 10.8 | 1.645 (0.918-2.948) | .095 | 25.0 ± 10.8 | 1.789 (0.996-3.213) | .051 | ||

| t(1;22)(p13;q13) | 51 (13.7) | 0.55 (0.03-6.25) | < .001 | 33 (64.7) | .050 | 54.5 ± 8.0 | 0.813 (0.531-1.244) | 58.2 ± 7.7 | 0.811 (0.519-1.265) | ||

| t(1;22), balanced only | 38 (10.2) | 0.39 (0.03-1.81) | < .001 | 25 (65.8) | .086 | 63.2 ± 9.0 | 0.660 (0.390-1.116) | 68.2 ± 8.4 | 0.632 (0.360-1.112) | ||

| t(1;22), unbalanced | 13 (3.5) | 1.13 (0.79-6.25) | 8 (61.5) | 30.8 ± 12.8 | 1.329 (0.682-2.593) | 30.8 ± 12.8 | 1.369 (0.701-2.675) | ||||

| Abnormality in 3q21q26 | 14 (3.8) | 1.61 (0.70-10.72) | 3 (21.4) | .028 | 64.3 ± 12.8 | 0.518 (0.213-1.259) | 64.3 ± 12.8 | 0.588 (0.242-1.430) | |||

| Deletion of 5q | 7 (1.9) | 2.43 (1.66-8.20) | .026 | 2 (28.6) | 57.1 ± 21.6 | 0.635 (0.203-1.985) | 64.3 ± 22.2 | 0.424 (0.105-1.708) | |||

| Trisomy 6 | 58 (15.6) | 1.28 (0.18-8.20) | 33 (56.9) | 39.2 ± 7.9 | 1.167 (0.811-1.679) | 50.1 ± 8.1 | 0.962 (0.643-1.437) | ||||

| Monosomy 7 | 13 (3.5) | 4.17 (0.39-15.01) | .006 | 6 (46.2) | 15.4 ± 10.0 | 1.924 (1.047-3.534) | .035 | 23.1 ± 11.7 | 2.276 (1.202-4.309) | .012 | |

| Abnormality of 7p | 43 (11.6) | 1.77 (0.51-8.20) | 19 (44.2) | 74.1 ± 8.0 | 0.350 (0.191-0.642) | .001 | 76.7 ± 7.9 | 0.307 (0.157-0.599) | .001 | ||

| Abnormality of 7q | 31 (8.3) | 1.99 (0.70-4.85) | .031 | 13 (41.9) | 63.5 ± 11.1 | 0.501 (0.273-0.919) | .026 | 67.0 ± 10.7 | 0.452 (0.231-0.883) | .020 | |

| Trisomy 8 | 77 (20.7) | 1.66 (0.25-15.29) | 41 (53.2) | 51.4 ± 6.2 | 0.774 (0.542-1.104) | 59.0 ± 6.3 | 0.681 (0.463-1.001) | .051 | |||

| Abnormality of 8q | 20 (5.4) | 1.55 (0.76-11.28) | 8 (40.0) | 64.0 ± 11.6 | 0.557 (0.262-1.184) | 71.4 ± 11.5 | 0.431 (0.177-1.048) | .063 | |||

| Abnormality of 9p, other than t(9;11) | 9 (2.4) | 2.10 (1.12-4.90) | .046 | 6 (66.7) | 22.2 ± 11.3 | 1.979 (0.930-4.208) | .076 | 22.2 ± 11.3 | 2.553 (1.198-5.438) | .015 | |

| Abnormality of 9q | 23 (6.2) | 1.78 (0.66-13.62) | .052 | 11 (47.8) | 52.2 ± 12.0 | 0.755 (0.411-1.385) | 59.2 ± 12.6 | 0.730 (0.374-1.425) | |||

| Trisomy 10 | 27 (7.3) | 1.77 (0.18-8.20) | 15 (55.6) | 55.3 ± 10.7 | 0.681 (0.380-1.221) | 64.2 ± 10.7 | 0.537 (0.275-1.050) | .069 | |||

| Abnormality of 11p | 18 (4.8) | 1.41 (0.18-12.58) | 10 (55.6) | 27.8 ± 10.6 | 1.605 (0.915-2.817) | .099 | 37.0 ± 12.0 | 1.368 (0.744-2.516) | |||

| Abnormality of 11q | 57 (15.3) | 1.83 (0.48-13.63) | .083 | 30 (52.6) | 34.9 ± 7.3 | 1.362 (0.955-1.945) | .088 | 39.7 ± 7.5 | 1.309 (0.902-1.898) | ||

| Abnormality of 11q23 | 38 (10.2) | 1.77 (0.59-13.63) | 21 (55.3) | 28.5 ± 9.1 | 1.632 (1.088-2.447) | .018 | 32.4 ± 9.4 | 1.548 (1.015-2.360) | .043 | ||

| t(9;11)(p22;q23) | 21 (5.6) | 1.41 (0.72-3.98) | 10 (47.6) | 17.1 ± 7.8 | 1.929 (1.173-3.171) | .010 | 17.1 ± 7.8 | 2.130 (1.292-3.514) | .003 | ||

| Other 11q23 | 17 (4.6) | 2.05 (0.59-13.63) | 11 (64.7) | 41.2 ± 15.8 | 1.223 (0.648-2.309) | 52.9 ± 16.2 | 0.932 (0.459-1.892) | ||||

| Abnormality of 12p | 16 (4.3) | 1.45 (0.84-8.54) | 6 (37.5) | 31.2 ± 13.0 | 1.197 (0.652-2.197) | 47.4 ± 15.4 | 1.110 (0.546-2.253) | ||||

| Monosomy 13 | 7 (1.9) | 1.12 (0.65-11.32) | 6 (85.7) | NA‡ | 3.433 (1.514-7.784) | .003 | 28.6 ± 17.1 | 2.202 (0.904-5.360) | .082 | ||

| Deletion of 13q | 16 (4.3) | 1.50 (0.56-4.90) | 5 (31.3) | 18.8 ± 9.8 | 1.850 (1.054-3.245) | .032 | 29.2 ± 12.3 | 1.805 (0.980-3.322) | .058 | ||

| Monosomy 15 | 7 (1.9) | 1.17 (0.81-2.04) | 5 (71.4) | 14.3 ± 9.4 | 2.914 (1.289-6.586) | .010 | 14.3 ± 9.4 | 2.133 (0.946-4.809) | .068 | ||

| Trisomy 19 | 93 (25.0) | 1.44 (0.25-6.54) | 41 (44.1) | .096 | 48.3 ± 5.8 | 0.903 (0.654-1.248) | 52.9 ± 5.9 | 0.898 (0.638-1.263) | |||

| Trisomy 21 | 106 (28.5) | 1.72 (0.08-8.20) | 48 (45.3) | 47.9 ± 5.8 | 0.882 (0.648-1.200) | 52.7 ± 5.9 | 0.803 (0.579-1.113) | ||||

| Abnormality of Xq | 15 (4.0) | 1.39 (0.48-7.32) | 9 (60.0) | 20.0 ± 8.9 | 1.796 (1.002-3.218) | .049 | 32.0 ± 11.8 | 1.498 (0.792-2.833) | |||

| Chromosome 49-65, numerical or structural | 52 (14.0) | 1.41 (0.49-6.54) | 25 (48.1) | 59.6 ± 7.3 | 0.631 (0.402-0.991) | .046 | 64.8 ± 7.1 | 0.588 (0.362-0.956) | .032 | ||

CI, confidence interval; EFS, event-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; SE, standard error.

For modal number and complexity, P values were obtained with the comparison of all factors. HR and P value in parentheses were derived from comparison with normal karyotype.

For chromosome subgroups, HR and P values were obtained by comparing particular subgroup with others and only P values < .1 are listed.

3-year event-free survival: 14.3% ± 13.2%

Specific recurrent chromosomal abnormalities

For whole numerical abnormalities, 195 of 372 (52.4%) patients had 592 acquired chromosome gain(s) (Figure 2B); +21 was the most frequent (n = 106, 28.5%), followed by +19 (n = 93, 25.0%), +8 (n = 77, 20.7%), +6 (n = 58, 15.6%), and +2 (n = 39, 10.5%). A patient had TMD at 7 weeks old and developed AMKL at 7 months old.16 In this patient, blast cells at both episodes showed +21, but GATA1 mutation was detected only at the time of TMD. Whole-chromosome loss(es) occurred in 65 of 372 (17.5%) patients, with 105 lesions: –7 (n = 13, 3.5%); –9 (n = 9, 2.4%); –13, –15, and –20 (n = 7 each, 1.9%) in decreasing order of frequency (Figure 2B); and –5 was seen in only 2 patients.

Figure 2C shows the overall analysis of unequivocal structural aberrations in 262 patients: 457 translocation breakpoints, 175 deletions, 111 additions, and 94 other structural changes. Of note, recurrent structural cytogenetic alterations in children with AMKL are distinct from those in other myeloid French-American-British classification (FAB) subtypes (Table 2). Most common recurrent alterations were t(1;22)(p13;q13) (n = 51) and 11q23 rearrangements (n = 38). Of 51 patients with t(1;22), 38 had balanced translocations, 2 had unbalanced translocations, and 11 had both. The cytogenetic abnormalities involving the 11q23 region were t(9;11)(p22;q23) (n = 21), t(10;11)(p12;q23) (n = 6), t(4;11)(q21;q23) and t(11;19)(q23;p13) (n = 2 each), and others (n = 7). Among the other 7 partners of 11q23, 14q23 (CEP170B or GPHN) has been previously recognized and the remaining were Xq22, 7p15, 8q13, 9q22, 17q23, and unknown. MLL rearrangements were confirmed in 21 of 38 patients by fluorescent in situ hybridization, reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, or Southern blotting: 15 with t(9;11) (2 had incomplete cytogenetic data), 4 with t(10;11), and 1 each with t(4;11) and t(11;19). Notably, 1 patient with t(11;14)(q23;q22) also had t(1;22).

Many recurrent abnormalities were identified mostly within complex karyotypes. Of 25 patients with 3q abnormalities, 5 also had a –7, which is a known association. Of these 25 patients, 14 had 3q21 and/or 3q26 break points and 1 had a t(3;21)(q24;q22). Of 28 patients with 5q abnormalities, 7 had deletions and 17 had translocations. Interestingly, 7p and 7q abnormalities were frequently detected (n = 43 and n = 31, respectively), and most abnormalities were in complex karyotypes. The 7p included translocation (n = 21), addition (n = 9), deletion (n = 5), ring (n = 5), inversion (n = 4), and insertion (n = 1) (supplemental Table 5). The 7q included translocation (n = 12), deletion (n = 6, 2 with 5q–), ring (n = 5), addition (n = 4), and isochromosome (n = 2). Chromosome 8 had only 2 recurrent aberrations: t(8;21)(q22;q22) and t(8;16)(p11.2;p13.3). Of 23 patients with 9q abnormalities, 10 had deletions, 2 had t(9;22)(q34;q11.2), and 1 had t(6;9)(p21;q34). For non-11q23 chromosome 11 abnormalities, 3 patients had t(10;11)(p12;q14) and 8 had break points in 11p15 (mapping of NUP98 gene). The 12p abnormality occurred in 16 patients: 6 had a deletion and 10 had mostly balanced rearrangements, including 2 with inv(12)(p13q13) and 1 with t(5;12)(p13;p13). Notably, 5 of the 16 12p abnormalities were associated with known recurrent abnormalities: t(4;11), t(8;16), t(6;9), t(8;21), and inv(16)(p13.1q22). Among 31 patients with 13q abnormalities, 16 had 13q deletions and 14 had translocations. Abnormalities of chromosome 16 included inv(16)(p13.1q22) (n = 1) and t(2;16)(n = 3), but in the latter, break points were annotated between 2p13-2p24 and 16q13-16q22. No patient had t(16;21)(p11;q22).

Hyperdiploidy with 49 to 65 chromosomes without t(15;17), t(8;21), inv(16), or t(9;11) is overrepresented in pediatric AMKL and comprises a heterogeneous cytogenetic subgroup.17 We identified 68 patients with such abnormalities (37.6% of 181 patients with complex karyotypes), including 7 with numerical, 45 with structural, and 16 with adverse (abnormalities of 3q [3 patients], –5 [1], 5q– [5], 11q23 translocations [4], and abnormalities of 17p [3]) changes. No patient had –7 or t(9;22), and 2 patients with 7q– were considered to have structural changes because 7q– was not associated with poor outcome in a pediatric international retrospective study.18

Comprehensive cross-tabulation was done to evaluate overlaps among cytogenetic subgroups (supplemental Table 6). At P < .0001, +6, +8, +10, +19, and +21 were significantly associated with each other, although +21 was not strongly associated with +10. Also, +1 was associated with t(1;22) because of high frequency of the unbalanced pattern, abnormality of 7p was associated with abnormalities of 7q and 8q, and t(9;11) was associated with +19. Complex karyotype was associated with +1, +6, abnormalities of 7p, +8, +10, +19, and +21; and numerical or structural changes among 49 to 65 chromosomes were associated with +1, +6, +8, +10, and +19.

Clinical features and outcomes by cytogenetic subtype

Patients with hypodiploidy were significantly older at diagnosis (median, 2.97 years; P = .003) than those with normal karyotype, pseudodiploidy, 47 to 50 chromosomes, and >50 chromosomes (Table 2). Among chromosome subgroups, those with t(1;22) (median, 0.55 years), especially balanced t(1;22) only (median 0.39 years), were younger (both P < .001) than other non-t(1;22) patients (Table 2). In contrast, patients with 5q– (median, 2.43 years; P = .026), –7 (median, 4.17 years; P = .006), 7q abnormalities (median, 1.99 years; P = .031), and 9p abnormalities other than t(9;11) (median, 2.10 years; P = .046) were older. The t(1;22) occurred more often in females (64.7%, P = .050) and the 3q21/3q26 more often in males (78.6%, P = .028) (Table 2). Extramedullary or CNS disease was not associated with a particular cytogenetic subgroup.

There were no significant differences in outcomes between patients for whom cytogenetic information was or was not available (Table 1). Patients with a normal karyotype had significantly worse OS (26.4% ± 7.5%) when modal number (P = .002) and complexity (P = .031) were considered, especially compared with patients with ≥47 chromosomes and ≥4 aberrations (Table 2).

Next, we compared outcomes of patients in a particular cytogenetic subgroup with those from all other groups. Notably, patients with 11q23 abnormalities had significantly worse EFS (28.5% ± 9.1%, P = .018) and OS (32.4% ± 9.4%, P = .043) than those without this abnormality (Table 2). This worse prognosis was attributed to only patients with t(9;11), who had 5-year EFS and OS of 17.1% ± 7.8% (P = .010 and .003, respectively) and not to those with 11q23 abnormalities other than t(9;11). Patients with 9p abnormalities had significantly worse outcome, which was attributed to both patients with t(9;11) and those with other 9p abnormalities (P = .076 for EFS and P = .015 for OS, both 22.2% ± 11.3%).

Patients with abnormalities in 7p and 7q had significantly better EFS (74.1 ± 8.0%, P = .001, and 63.5% ± 11.1%, P = .026, respectively) and OS (76.7% ± 7.9%, P = .001, and 67.0% ± 10.7%, P = .020) than those in other cytogenetic groups. However, patients with –7 had worse EFS (15.4% ± 10.0%, P = .035) and OS (23.1% ± 11.7%, P = .012) than those in other groups. Patients with numerical or structural changes among 49 to 65 chromosomes had significantly better EFS (59.6% ± 7.3%, P = .046) and OS (64.8% ± 7.1%, P = .032) than those in other cytogenetic groups.

Other karyotypes associated with significantly worse EFS were –13 (P = .003), 13q– (18.8% ± 9.8%, P = .032), and –15 (14.3% ± 9.4%, P = .010), and patients with normal karyotypes had significantly worse OS (P = .005) than those in other subtypes. Patients with t(1;22) did not have a better EFS (54.5% ± 8.0%) or OS (58.2% ± 7.7%) than those in other subtypes (Table 2 and supplemental Figure 3). Notably, among the 12 patients who died early, cytogenetic information was available for 11 patients and 5 patients had balanced t(1;22) only, which accounted for 5 of 13 deaths in this subgroup.

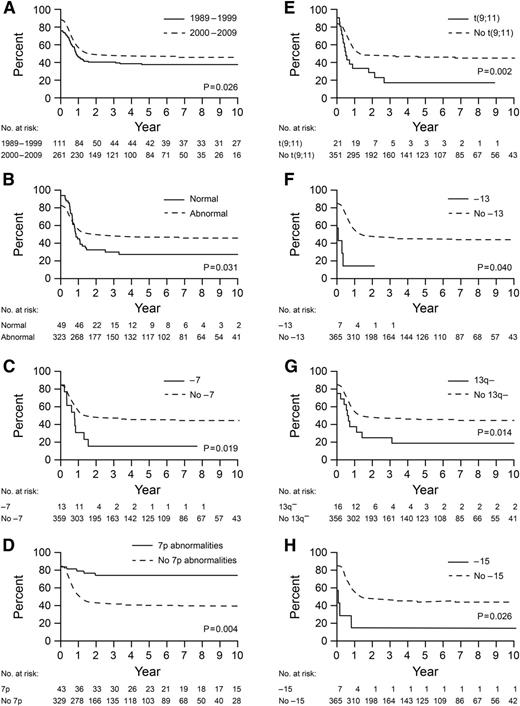

Multivariable Cox regression analysis for EFS and OS with clinical and cytogenetic features showed that year of diagnosis (1989-1999 vs 2000-2009) (P = .026 and .004, respectively), normal karyotype (P = .031 and .001), –7 (P = .019 and .004), t(9;11) (P = .002 and < .001), 13q– (P = .014 and .038), and –15 (P = .026 and .006) were associated with significantly worse outcomes, whereas 7p abnormalities were associated with better outcomes (P = .004 and .004) (Table 3 and Figure 3). Patients with –13 and 9p abnormalities other than t(9;11) had a poorer EFS (P = .040) and OS (P = .021), respectively, than those in other subgroups.

Multivariable Cox regression analysis of clinical factors and cytogenetics for event-free survival and overall survival

| Clinical characteristics . | HR . | 95% CI . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Event-free survival | |||

| Year of diagnosis: 1989-1999 vs 2000-2009 | 1.39 | 1.04-1.87 | .026 |

| Normal karyotype | 1.52 | 1.04-2.23 | .031 |

| Monosomy 7 | 2.10 | 1.13-3.91 | .019 |

| Abnormality of 7p | 0.40 | 0.21-0.74 | .004 |

| t(9;11) | 2.26 | 1.35-3.79 | .002 |

| Monosomy 13 | 2.72 | 1.05-7.05 | .040 |

| Deletion 13q | 2.06 | 1.16-3.66 | .014 |

| Monosomy 15 | 2.96 | 1.14-7.68 | .026 |

| Overall survival | |||

| Year of diagnosis: 1989-1999 vs 2000-2009 | 1.57 | 1.16-2.13 | .004 |

| Normal karyotype | 1.95 | 1.32-2.88 | .001 |

| Monosomy 7 | 2.60 | 1.35-4.99 | .004 |

| Abnormality of 7p | 0.37 | 0.18-0.73 | .004 |

| t(9;11) | 2.70 | 1.60-4.54 | <.001 |

| Abnormality of 9p other than t(9;11) | 2.48 | 1.15-5.36 | .021 |

| Deletion 13q | 1.94 | 1.04-3.64 | .038 |

| Monosomy 15 | 3.21 | 1.40-7.33 | .006 |

| Clinical characteristics . | HR . | 95% CI . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Event-free survival | |||

| Year of diagnosis: 1989-1999 vs 2000-2009 | 1.39 | 1.04-1.87 | .026 |

| Normal karyotype | 1.52 | 1.04-2.23 | .031 |

| Monosomy 7 | 2.10 | 1.13-3.91 | .019 |

| Abnormality of 7p | 0.40 | 0.21-0.74 | .004 |

| t(9;11) | 2.26 | 1.35-3.79 | .002 |

| Monosomy 13 | 2.72 | 1.05-7.05 | .040 |

| Deletion 13q | 2.06 | 1.16-3.66 | .014 |

| Monosomy 15 | 2.96 | 1.14-7.68 | .026 |

| Overall survival | |||

| Year of diagnosis: 1989-1999 vs 2000-2009 | 1.57 | 1.16-2.13 | .004 |

| Normal karyotype | 1.95 | 1.32-2.88 | .001 |

| Monosomy 7 | 2.60 | 1.35-4.99 | .004 |

| Abnormality of 7p | 0.37 | 0.18-0.73 | .004 |

| t(9;11) | 2.70 | 1.60-4.54 | <.001 |

| Abnormality of 9p other than t(9;11) | 2.48 | 1.15-5.36 | .021 |

| Deletion 13q | 1.94 | 1.04-3.64 | .038 |

| Monosomy 15 | 3.21 | 1.40-7.33 | .006 |

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Kaplan-Meier curves for EFS for 372 patients for whom cytogenetic data were available. (A) Patients diagnosed in 1989 to 1999 vs 2000 to 2009; (B) patients with vs without normal karyotype; (C) patients with vs without –7; (D) patients with vs without abnormalities of 7p; (E) patients with vs without t(9;11); (F) patients with vs without –13; (G) patients with vs without 13q–; and (H) patients with vs without –15. P values are derived from multivariable Cox regression analysis.

Kaplan-Meier curves for EFS for 372 patients for whom cytogenetic data were available. (A) Patients diagnosed in 1989 to 1999 vs 2000 to 2009; (B) patients with vs without normal karyotype; (C) patients with vs without –7; (D) patients with vs without abnormalities of 7p; (E) patients with vs without t(9;11); (F) patients with vs without –13; (G) patients with vs without 13q–; and (H) patients with vs without –15. P values are derived from multivariable Cox regression analysis.

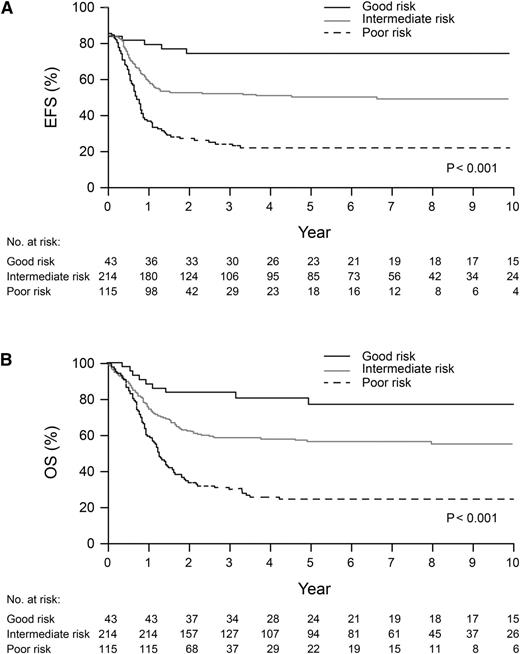

On the basis of results of multivariable analysis, we classified pediatric AMKL patients by survival risk group: good—abnormalities of 7p; poor—normal karyotype, –7, t(9;11), 9p abnormalities other than t(9;11), –13, 13q–, or –15; and intermediate—patients not included in the good- or poor-risk groups. EFS (74.1% ± 8.0% vs 21.7% ± 4.7% vs 50.0% ± 4.1%) and OS (76.7% ± 7.9% vs 24.2% ± 4.7% vs 56.2% ± 4.1%) were significantly different (both P < .001) for patients in these 3 risk groups (Figure 4A-B).

Kaplan-Meier curves for EFS (A) and overall survival (OS) (B) for 372 patients with good-, poor-, and intermediate-risk abnormalities. Good risk: abnormalities of 7p; poor risk: normal karyotype, –7, t(9;11), 9p abnormalities other than t(9;11), –13, 13q–, or –15; and intermediate risk: patients not included in good or poor-risk group. A patient with both 7p abnormalities and –15 was included in the good-risk group.

Kaplan-Meier curves for EFS (A) and overall survival (OS) (B) for 372 patients with good-, poor-, and intermediate-risk abnormalities. Good risk: abnormalities of 7p; poor risk: normal karyotype, –7, t(9;11), 9p abnormalities other than t(9;11), –13, 13q–, or –15; and intermediate risk: patients not included in good or poor-risk group. A patient with both 7p abnormalities and –15 was included in the good-risk group.

Discussion

We report herein the largest international collaborative study of pediatric AMKL. AMKL was seen in 7.8% of pediatric patients with AML in this retrospective study. The most common recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities were t(1;22) and those involving 11q23, mostly t(9;11). Interestingly, prognosis was significantly worse in patients with t(9;11) and normal karyotype and better in those with 7p abnormalities.

Consistent with survival data on patients with AML,19 AMKL patients in our study diagnosed in or after 2000 had better prognosis than those diagnosed earlier. This is possibly related to administration of intensified chemotherapy, especially higher doses of cytarabine, and better supportive care in the recent era than in previous eras.19 However, no improvement was seen for patients diagnosed in 2005 to 2009 compared with those diagnosed in 2000 to 2004, and EFS (46.5%) and OS (53.0%) of AMKL patients are worse than those of all AML patients treated in major clinical trials during the same period (EFS 55.0%-63.0% and OS 67.7%-75.6%).11,20-22 Data on the benefit of allo-HSCT in AMKL are conflicting.1-3,10 We found no benefit of allo-HSCT in first CR, although criteria for allo-HSCT differed among protocols. Some patients were salvaged by allo-HSCT in second CR or with evidence of residual disease, although the latter group was limited to the recent era. These findings suggest that allo-HSCT could be part of the salvage regimen. To improve the survival of patients, novel approaches based on subgroups of risk and better knowledge of their underlying biology are required. Induction of polyploidization and terminal differentiation of AMKL blasts by small molecules such as aurora kinase A inhibitors is of interest.23

Consistent with the study by Dastugue et al,4 cytogenetic analysis of our pediatric patients revealed normal karyotypes, numerical abnormalities, and t(1;22)(p13;q13). However, patients with t(9;22) and –5 were rare and no patient had i(12)(p10). We found that –7, t(9;11), 9p abnormalities other than t(9;11), –13/13q-, –15, and 7p abnormalities have prognostic significance. According to frequency and/or prognosis, we propose to classify pediatric non-DS AMKL to 3 risk groups: good risk—7p abnormalities; poor risk—normal karyotypes, –7, 9p abnormalities including t(9;11)(p22;q23)/MLL-MLLT3, –13/13q–, and –15; and intermediate risk—others including t(1;22)(p13;q13)/OTT-MAL, 11q23/MLL except t(9;11), and numerical and structural changes without adverse karyotype among 49 to 65 chromosomes.

In a retrospective I-BFM study of 11q23 leukemia, patients with t(9;11) were at intermediate risk, with a 5-year EFS of 50%. However, patients with FAB M5 morphology had significantly better 5-year EFS (56%) than those with other FAB subtypes (31%), suggesting a difference in biology based on cell type of origin of leukemia.24 In contrast to other AML subtypes,25 patients with normal karyotypes had worse prognosis than those with cytogenetic aberrations in our study. FLT3-internal tandem duplication (ITD) occurs in as much as 15% of children with AML, frequently in those with normal karyotypes, and is associated with poor prognosis.26 However, FLT3-ITD is rare in AMKL.26 The normal development of megakaryocytes requires polyploidization, and AMKL is often associated with hyperdiploidy.5 Thus, AMKL cells with a normal karyotype might abort these processes early and be associated with an unfavorable phenotype. Although multivariable analysis did not reveal significant differences, univariate analysis showed that patients with numerical or structural changes among 49 to 65 chromosomes had significantly better EFS and OS than those in other cytogenetic subgroups. Recently, high-resolution profiling of genetic alterations identified several submicroscopic genetic alterations contributing to leukemogenesis. For example, the fusion gene CBFA2T3-GLIS2 functions as a driver mutation and is associated with worse outcomes.27 Furthermore, extensive genetic characterization revealed various type II abnormalities in pediatric patients with AMKL, such as NUP98-JARID1A and MLL-PTD in addition to OTT-MAL, CBFA2T3-GLIS2, and MLL rearrangements.28,29 In our retrospective study, additional samples were not available for such investigations, especially for abnormalities that are cytogenetically cryptic or subtle. Further genomic analysis of AMKL leukemia blasts with both normal and abnormal karyotype will improve our understanding of pathogenesis and help develop targeted therapies.

The –7, but not 7q–, was significantly associated with worse prognosis in our study and another I-BFM study in which 12 (7.0%) of 172 children with AML and –7 had AMKL.18 Chromosome 13, especially the 13q14 locus, is associated with the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene (RB1).30 The 13q14 deletion is the most common chromosomal loss in AMKL cell lines and also occurs in myeloid malignancies and idiopathic myelofibrosis, with or without abnormal megakaryoblast proliferation.31,32 Reduced RB1 expression is significantly associated with poor outcome in AML.30 Also, autosomal chromosomal monosomies including –7, –13, and –15 are strongly associated with adverse outcome in adults with AML.33 7p abnormalities, occurring in 1% of young adults with AML, are associated with poor prognosis.34 However, AMKL patients with 7p abnormalities had significantly better outcome in our series.

The t(1;22), an AML subgroup added in the 2008 WHO classification,6 is predominant in infants and more frequent in girls. Previous studies on small numbers of patients showed that AMKL patients with t(1;22) have a good prognosis,12,28,35 but we did not observe this, possibly because of the high rate of early death in patients with balanced t(1;22). Careful supportive care is required to prevent early death,36 especially for patients with t(1;22), because of their very young age. In addition, high frequencies of trisomies 21, 19, and 8 without prognostic significance in our patients are comparable with findings from other studies.1,3,28 The biology of acquired +21 is different from that of DS-associated AMKL, which is associated with significantly better outcomes; GATA1 mutations; and frequent mutations in the cohesin complex, EZH2 and other epigenetic regulators, and JAK family kinases.37,38

Because AMKL is frequently associated with myelofibrosis and seen in young children, it is often difficult to obtain sufficient material for cytogenetic analysis. We do not have cytogenetic data for 118 (24.1%) patients, and the results need to be interpreted with caution; however, the prognosis of patients for whom cytogenetic information was and was not available did not differ. Considering these characteristics and the retrospective nature of this study, we believe that the availability of cytogenetic data for 75.9% of patients is remarkable. Cytogenetic central review helped exclude incomplete cases and organize abnormal karyotypes into subgroups. Another study limitation was that patients were treated on different protocols spanning long time periods. However, all protocols consisted of intensive chemotherapy comprising an anthracycline and cytarabine backbone, including HSCT for some patients, and we were able to evaluate the changes in chemotherapy intensity over time, which can be associated with improved survival of patients in the recent era. International collaborations are essential to study relatively rare leukemia subgroups such as AMKL.

In conclusion, our data highlight the great heterogeneity in cytogenetic findings of patients with AMKL and show that patients allocated to some specific cytogenetic subgroups have significantly different outcomes, which enables the classification of pediatric AMKL patients into 3 risk groups according to prognosis for risk-based therapy. New methods to evaluate genetic lesions can help identify underlying molecular pathogenic alterations and possible therapeutic targets, which can improve the outcome of children with AMKL.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jan Stary (the Czech Pediatric Hematology Working Group), Owen Smith (Our Lady's Children's Hospital Crumlin, Ireland), and Janez Jazbec (University Children’s Hospital, Ljubljana, Slovenia) for entering patients into this study, Kathleen Jackson (St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital) for data management, and Vani Shanker (St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital) for editorial assistance.

This study was supported by Cancer Center Support (CORE) grant P30 CA021765 from the National Institutes of Health (H.I., Y.Z., S.C.R.), ALSAC (H.I., Y.Z., S.C.R.), a grant for clinical cancer research from the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan (S.A., T.T., D.T.), and the Italian Association for Research on Cancer (AIRC) Special Project 5x1.000 (F.L.).

Authorship

Contribution: H.I. and S.C.R. conceived and designed the study; H.I., O.A., S.A., A.A., H.B.B., E.d.B., T.-T.C., U.C., M.D., S.E., A.F., E.F., H.H., D.-C.L., V.L., F.L., R.M., B.D.M., D.R., L.R., N.V.R., S.S., T.T., D.T., A.E.J.Y., M.Z., and S.C.R. provided study materials and patients; H.I., Y.Z., and S.C.R. provided data analysis and interpretation; H.I. and S.C.R. wrote the manuscript; and all authors provided final approval of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Hiroto Inaba, Department of Oncology, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, 262 Danny Thomas Place, Mail Stop 260, Memphis, TN 38105-2794; e-mail: hiroto.inaba@stjude.org.