Key Points

Pomalidomide leads to rapid immune activation in vivo correlating with clinical outcome in relapsed myeloma.

Baseline expression of ikaros/aiolos protein in tumor cells is not predictive of outcome.

Abstract

In preclinical studies, pomalidomide mediated both direct antitumor effects and immune activation by binding cereblon. However, the impact of drug-induced immune activation and cereblon/ikaros in antitumor effects of pomalidomide in vivo is unknown. Here we evaluated the clinical and pharmacodynamic effects of continuous or intermittent dosing strategies of pomalidomide/dexamethasone in lenalidomide-refractory myeloma in a randomized trial. Intermittent dosing led to greater tumor reduction at the cost of more frequent adverse events. Both cohorts experienced similar event-free and overall survival. Both regimens led to a distinct pattern but similar degree of mid-cycle immune activation, manifested as increased expression of cytokines and lytic genes in T and natural killer (NK) cells. Pomalidomide induced poly-functional T-cell activation, with increased proportion of coinhibitory receptor BTLA+ T cells and Tim-3+ NK cells. Baseline levels of ikaros and aiolos protein in tumor cells did not correlate with response or survival. Pomalidomide led to rapid decline in Ikaros in T and NK cells in vivo, and therapy-induced activation of CD8+ T cells correlated with clinical response. These data demonstrate that pomalidomide leads to strong and rapid immunomodulatory effects involving both innate and adaptive immunity, even in heavily pretreated multiple myeloma, which correlates with clinical antitumor effects. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT01319422.

Introduction

The therapeutic landscape in multiple myeloma (MM) has changed considerably in the last decade with the introduction of the immunomodulatory drugs thalidomide (Thal) and its analog lenalidomide (Len).1 Pomalidomide (Pom) is the newest immunomodulatory drug that shares structural features with both Thal and Len.2,3 In early phase clinical studies, Pom was administered at a dose of 2 to 4 mg/day either as continuous (28/28 day) dosing (analogous to Thal) or in an intermittent (21/28 day) dosing schedule (analogous to Len) and demonstrated comparable clinical activity in relapsed/refractory MM (RRMM).4-10 In a phase 3 trial, Pom and low-dose dexamethasone (Dex) improved progression-free survival compared with high-dose Dex in patients with RRMM.11 Based on these studies, Pom was approved for therapy of patients with relapsed myeloma who have received ≥2 prior therapies, including Len and bortezomib and demonstrated disease progression on or within 60 days of completion of the last therapy. However, the optimal dosing schedule (continuous vs intermittent) for Pom has not been rigorously tested,9,10 and data comparing pharmacodynamics properties of the 2 regimens are lacking.12 Such data are essential to better understand the mechanism of antitumor effects in vivo and optimize the clinical development of Pom.

In preclinical and mostly in vitro studies, Pom was shown to mediate direct antiproliferative effects on tumor cells, as well as immune-modulatory effects on T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and monocytes.13-23 In early phase studies, Pom therapy led to an increase in CD45RO+ T cells, and serum levels of interleukin (IL)12 and soluble IL2 receptor, along with a concurrent decrease in CD45RA+ T cells in vivo.8 Pom has greater direct antiproliferative effects on myeloma tumor cells compared with Len. Cereblon (CRBN)-CRL4 E3 ligase has emerged as a direct cellular target for Thal and its analogs Len and Pom.18,24,25 Binding of Len to CRBN promotes selective degradation of Ikaros (IKZF1) and Aiolos (IKZF3), which is essential for Len-mediated antiproliferative effects on myeloma cells.26,27 Depletion of IKZF1/IKZF3 has also been implicated in Len-mediated amplification of anti-CD3-induced IL2 production in human T cells in culture21,27 ; however, the impact of Pom therapy on Ikaros levels in immune cells in vivo has not been studied. It is notable that the effects of Len/Pom on T-cell activation involve costimulation and require T-cell receptor/antigen-dependent signal 1.28,29 Despite shared mechanisms of antitumor effects, Pom has also been reported to have antitumor activity in a proportion of patients with disease progressing on Len therapy.3 In recent studies, we showed that the immunomodulatory effects of Len therapy are highly dependent on drug exposure and are detected as early as 7 days after initiation of therapy.30 Therefore, in the setting of intermittent dosing, it is essential to evaluate mid-cycle immunologic effects in vivo. Immune-modulatory effects of Pom therapy in vivo in patients have not yet been studied in detail, and the impact of different dosing schedules or concurrent steroids on Pom-mediated immune activation, particularly in the setting of RRMM, remains to be clarified. In view of shared cellular targets of Pom and Len, the role of cereblon/ikaros protein expression in predicting the clinical activity of Pom in Len-refractory disease is being explored.18,25,31 However, it is essential that such measurements be obtained using validated assays.32 Here we describe the findings from a prospective randomized phase 2 trial evaluating clinical and pharmacodynamics effects of 2 dosing schedules for Pom in the setting of Len-refractory MM to address these issues.

Methods

Study objectives and design

The primary objective of this study was to estimate the clinical activity (in terms of objective response rate) of continuous and intermittent dosing regimens of Pom/Dex in the context of a phase 2 randomized trial in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma refractory to prior Len therapy. Secondary objectives were to evaluate the immunologic effects of this therapy and correlate the immunologic effects and baseline properties of tumor cells with clinical outcome.

Eligibility

Patients were eligible if they were ≥18 years of age and had relapsed MM following ≥2 prior standard lines of therapy including Len. Induction therapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation was considered a single regimen. Patients were required to have disease refractory to prior Len therapy, defined as objective progression on a regimen containing full or maximally tolerated dose of Len administered for ≥1 cycle of therapy. Patients were required to have measurable disease defined as one of the following: serum monoclonal protein >10 g/L, serum immunoglobulin free light chain >10 mg/dL and an abnormal free light chain ratio, urine light chain excretion >200 mg/24 hours, measurable soft-tissue plasmacytoma that had not been radiated, or >30% bone marrow plasma cells. All prior cancer therapy must have been discontinued >2 weeks before study registration. Patients were also required to have Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score 0 to 2, absolute neutrophil count >1 × 109/L, platelet count >75 × 109/L, serum creatinine <221 μM (<2.5 mg/dL), total bilirubin <2 mg/dL, transaminases ≤5 upper limit of normal, and be disease free of prior malignancies for ≥5 years. Women of childbearing potential were required to document a negative pregnancy test and use a dual method of contraception, whereas men had to agree to use a condom with sexual activity. Pregnant or breastfeeding women and those with grade 3 to 4 peripheral neuropathy, use of another investigational drug within 28 days, prior hypersensitivity or erythema nodosum following immunomodulatory drug (IMiD), known positivity for HIV infection, or active hepatitis B or C were excluded. All patients signed an informed consent approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Board in accordance with federal regulations and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Treatment schema

Patients were randomized (1:1) to receive Pom on continuous (2 mg/day for 28/28 days) or intermittent dosing (4 mg/day for 21/28 days) schedule. All patients received Pom alone for cycle 1, and Dex at 40 mg weekly was added with cycle 2 and beyond. The dose of Dex for patients >70 years old was 20 mg. Patients also received aspirin at 325 mg/day for thromboprophylaxis. Dose adjustments for both Pom and Dex were permitted for grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events, and re-escalation was not permitted. Use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor was permitted at physician’s discretion after cycle 2, to avoid dose reduction. Initiation of a new cycle required neutrophil count of >1 × 109/L, platelet count of 75 × 109/L, and recovery of nonhematopoietic toxicity to less than grade 2. Therapy was continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or withdrawal of informed consent.

Response and toxicity criteria

Response and progression were assessed according to the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) criteria and required 2 consecutive assessments made at any time. The National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3, was used to grade adverse events.

Statistical considerations

The study was designed as a randomized phase 2 trial. The primary end point was to estimate the proportion of patients achieving confirmed partial response (PR) or greater by IMWG criteria. Other clinical end points were progression-free and overall survival. Exact binomial confidence intervals were constructed for survival end points. All time-to-event analyses were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. A data cutoff was made on June 1, 2014. Statistical analysis was performed with SAS 9.3 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Correlative studies

All patients provided consent for correlative studies. Baseline evaluation included collection of both blood and bone marrow aspirate and biopsy for correlative studies. All patients had posttherapy blood samples collected at 3 hours, 1 week, and 4 weeks after initiation of cycles 1 and 2 and thereafter before initiation of a new cycle of therapy. Collection of a posttreatment bone marrow sample after 2 cycles of therapy was optional.

Immune profiling

Multiparameter flow cytometry was used to evaluate the profile of immune cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. LIVE/DEAD Fixable Green Dead Cell stain kit (Molecular Probes) was used to stain dead cells as per the protocol recommended by the manufacturer before staining with labeled antibodies. Fluorochrome-conjugated anti-human antibodies CD3 (SP34-2), CD4 (RPA-T4), and CD8 (RPA-T8) from BD Pharmingen and CD56 (HCD56) from BioLegend were used to identify T and NK cell subsets. All samples were acquired on BD LSRFortessa or BD LSR II, and the data were analyzed using Flowjo v9.7.5 software (TreeStar Inc.).

Functional analysis of T and NK cells

Analysis in intracellular cytokines (IL-2, IL-4, interferon [IFN]γ, tumor necrosis factor [TNF]α, IL-13, and IL-17A) and lytic molecules (GranzymeB and Perforin) on NK and T cells was performed as previously described.30 For cytokine detection, cells were stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and ionomycin, both at a 500 ng/mL concentration for 5 hours at 37°C in the presence of protein transport inhibitor BD Golgi Stop (0.7 μL/mL).

Analysis of immune checkpoints

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were analyzed for the expression of immune checkpoints using flow cytometry. Antibodies against human CD272 (BTLA, clone MIH26) from BioLegend and CD279 (PD-1, J105) and TIM3 (F38-2E2) from eBioscience were used to study their expression on the surface of T cells and NK cells.

Gene expression profiling of tumor microenvironment

Bone marrow mononuclear cells from before or after 2 cycles of therapy were sorted to isolate CD138+ plasma cells. RNA was isolated from sorted bone marrow derived from CD138− cells using the RNeasy Total RNA isolation kit (Qiagen) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. The Illumina Human HT-12v4 Expression Beadchip kit was used for the gene expression studies. Gene expression data were imported into Genespring Gx 12.5 (Agilent Technologies) or Partek GS 6.6 (Partek) for analysis of the microarray data. Gene Ontology analysis was performed on the differentially regulated gene targets using the Genespring GX 12.5 analysis platform. Functional pathway analysis was performed using the MetaCore Analytical Suite (Thomson Reuters) as described previously.33

Sequential evaluation of intranuclear Ikaros in immune cells

To detect changes in intranuclear Ikaros in immune cells following Pom therapy, cells labeled with T and NK cell markers were fixed and permeabilized using the BD Pharmingen Transcription Factor Buffer Set using the recommended protocol. A fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibody against IKZF1 (R32-1149) was used to detect intranuclear levels of the protein.

Immunohistochemistry for cereblon, Ikaros, and Aiolos expression in tumor cells and H-score

Expression of cereblon, Ikaros, and Aiolos were evaluated in baseline bone marrow biopsies by immunohistochemistry (IHC) (Y.R., M.W., S.C., D.H., K. Miller, A. Lopez-Girona, C. Bjorklund, A. Gandhi, A.T., R. Chopra, M.B., unpublished data). Sequential dual-color CRBN/CD138, Aiolos/CD138, and Ikaros/CD138 IHC (assays were performed on the Bond-Max automated slide stainer (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). Briefly, sections were deparaffinized on a Bond instrument. Antigen retrieval was performed for 20 minutes at 100°C in Epitope Retrieval solution 2, pH 9.0. Celgene anti-CRBN rabbit monoclonal antibody CRBN65, Celgene anti-Aiolos rabbit monoclonal antibody clone 9B-9-7, and rabbit polyclonal anti-Ikaros antibody (catalog no. sc-13039; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were used at 1/2000, 1/800, and 1/400 dilution, respectively; DAB substrate (3,3′-diaminobenzidine) was then developed using Leica Bond Polymer Refine Detection (DS9800). Dako anti-CD138 mouse monoclonal antibody (catalog no. M7228; Dako, Carpinteria, CA) was used at a 1/2000 dilution, and Fast Red substrate was developed using Leica Bond Polymer Refine Red Detection (DS9390). After staining was complete, slides were rinsed in tap water, baked in a 60°C oven for 20 minutes until completely dry, and then coverslipped.

CRBN, Aiolos, and Ikaros immunoreactivity of CD138+ MM cells was scored using the H-score method as described previously.34,35 The entire tumor was scored for each target protein’s immunoreactivity based on staining intensity and the percentage of cells staining positively. Staining intensity was recorded on a scale of 0 to 3 for negative, mild, moderate, and strong immunoreactivity, respectively. The percentage of tumor cells that are negative (0) or positive (1-3) for each marker was noted in 10% increments. A final score (range, 0-300) was the sum of the products of each intensity value multiplied by the percentage of cells at that intensity to account for 100% of the tumor cells. Cytoplasmic and nuclear CRBN H-scores were recorded separately for each sample. For each marker, the average H-scores from 3 pathologists were used in the final analysis.

Results

Patient and treatment characteristics

Thirty-nine eligible patients with relapsed myeloma were randomized to therapy with Pom/Dex (following Pom alone for cycle 1), using either continuous Pom dosing (2 mg-28/28 days, cohort 1, n = 19) or an intermittent dosing schedule (4 mg-21/28 days, cohort 2, n = 20; supplemental Figure 1 available on the Blood Web site). Patient demographics and baseline characteristics were similar between both cohorts (Table 1). All patients had received prior therapy with Len and bortezomib and were known to be Len refractory. The study cohort had received a median of 4 prior lines of therapy before study entry. Importantly, 79% patients had disease refractory to both Len and bortezomib (Bort). All patients received Pom alone for cycle 1, followed by Pom/Dex for subsequent cycles. Median duration of therapy was 4.8 months and similar between the 2 arms (4.2 vs 5.1 months; P = .5). As of the cutoff date of March 31, 2014, all but 1 patient had discontinued therapy. The most common cause for treatment discontinuation was disease progression (77% of patients), similar in both arms. Seven patients (36.8%) in cohort 1 and 7 patients (35%) in cohort 2 required dose reduction. The median number of cycles of therapy delivered in cohorts 1 and 2 was 4 and 5, respectively.

Patient characteristics

| Variable . | All patients (n = 39) [N (%)]* . | Cohort 1, 2 mg-28/28 (n = 19) [N (%)] . | Cohort 2, 4 mg-21/28 (n = 20) [N (%)] . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (years) | 61 | 63 | 61 | .68 |

| Male sex | 22 (56) | 10 (52) | 12 (60) | .64 |

| IgH type | .30 | |||

| IgG | 20 (51) | 8 (42) | 12 (60) | |

| IgA | 5 (13) | 4 (21) | 1 (5) | |

| Light chain only | 14 (36) | 7 (37) | 7 (35) | |

| IgL type | .73 | |||

| κ | 28 (72) | 13 (68) | 15 (75) | |

| Λ | 11 (28) | 6 (32) | 5 (25) | |

| Mean serum β2 microglobulin (mg/L) | 3.2 | 3.0 | 3.4 | .45 |

| Mean serum albumin (g/dL) | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 | .65 |

| Lines of prior therapy (median) | 4 | 4 | 4 | .64 |

| Cytogenetics | ||||

| Deletion chromosome 17p† | 7 (18) | 4 (21) | 3 (15) | .64 |

| Chromosome 1q abnormalities | 18 (46) | 10 (55) | 8 (42) | .41 |

| Deletion chromosome 13 | 13 (33) | 5 (28) | 8 (42) | .36 |

| Len as most recent therapy | 15 (38) | 6 (32) | 9 (45) | .38 |

| Resistance to prior therapy | .99 | |||

| Len refractory | 39 (100) | 19 (100) | 20 (100) | |

| Len + bortezomib refractory | 31 (79) | 15 (79) | 16 (80) |

| Variable . | All patients (n = 39) [N (%)]* . | Cohort 1, 2 mg-28/28 (n = 19) [N (%)] . | Cohort 2, 4 mg-21/28 (n = 20) [N (%)] . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (years) | 61 | 63 | 61 | .68 |

| Male sex | 22 (56) | 10 (52) | 12 (60) | .64 |

| IgH type | .30 | |||

| IgG | 20 (51) | 8 (42) | 12 (60) | |

| IgA | 5 (13) | 4 (21) | 1 (5) | |

| Light chain only | 14 (36) | 7 (37) | 7 (35) | |

| IgL type | .73 | |||

| κ | 28 (72) | 13 (68) | 15 (75) | |

| Λ | 11 (28) | 6 (32) | 5 (25) | |

| Mean serum β2 microglobulin (mg/L) | 3.2 | 3.0 | 3.4 | .45 |

| Mean serum albumin (g/dL) | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 | .65 |

| Lines of prior therapy (median) | 4 | 4 | 4 | .64 |

| Cytogenetics | ||||

| Deletion chromosome 17p† | 7 (18) | 4 (21) | 3 (15) | .64 |

| Chromosome 1q abnormalities | 18 (46) | 10 (55) | 8 (42) | .41 |

| Deletion chromosome 13 | 13 (33) | 5 (28) | 8 (42) | .36 |

| Len as most recent therapy | 15 (38) | 6 (32) | 9 (45) | .38 |

| Resistance to prior therapy | .99 | |||

| Len refractory | 39 (100) | 19 (100) | 20 (100) | |

| Len + bortezomib refractory | 31 (79) | 15 (79) | 16 (80) |

Numbers in parentheses represent percentage of the cohort, when applicable.

Of 26 patients with available data.

Response to therapy and survival

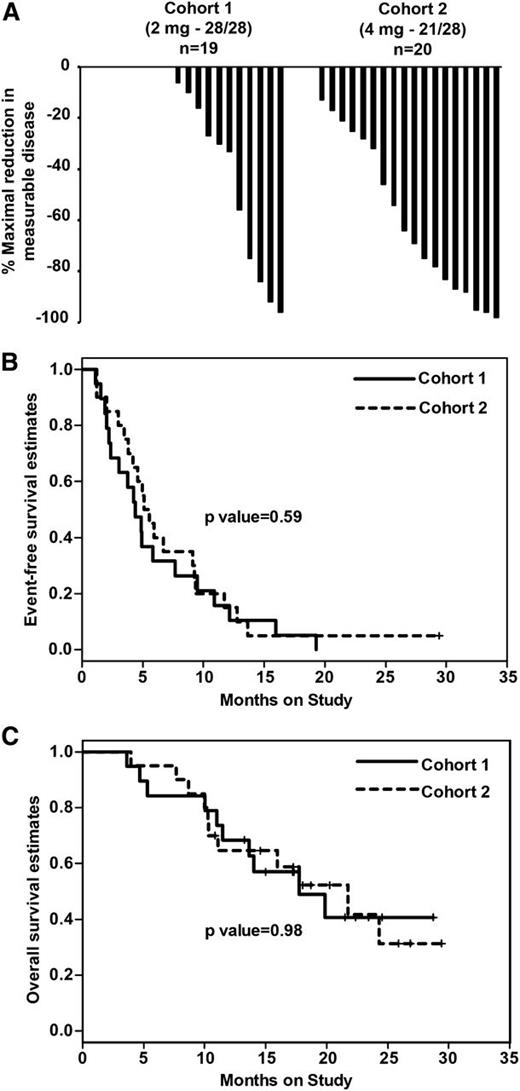

Overall, 13 of 39 patients treated achieved a confirmed objective response (≥PR by IMWG criteria). Objective responses were observed in 4 of 19 patients in cohort 1 (2 PR, 2 very good partial response) and 9 of 20 patients in cohort 2 (7 PR, 2 very good partial response). The objective response rate was 21% in cohort 1 and 45% in cohort 2 (P = .17). None of the patients achieved a confirmed complete response. Patients in the 21/28-day cohort experienced a greater mean percent reduction in measurable disease compared with the 28/28-day cohort (mean reduction, 54% vs 28%; P = .02; Figure 1A).

Clinical response and survival following pomalidomide/dexamethasone in Len-refractory myeloma. Patients were randomized to therapy with pomalidomide at 2 mg/day on a 28/28-day continuous schedule (n = 19; cohort 1), or 4 mg/day on a 21/28-day intermittent schedule (n = 20; cohort 2). All patients received Pom alone for cycle 1 and with weekly dexamethasone with cycle 2 and beyond. (A) Waterfall plot of maximal reduction in measurable disease. (B) Kaplan-Meier plot comparing event-free survival in the 2 cohorts. (C) Kaplan-Meier plot comparing overall survival in the 2 cohorts.

Clinical response and survival following pomalidomide/dexamethasone in Len-refractory myeloma. Patients were randomized to therapy with pomalidomide at 2 mg/day on a 28/28-day continuous schedule (n = 19; cohort 1), or 4 mg/day on a 21/28-day intermittent schedule (n = 20; cohort 2). All patients received Pom alone for cycle 1 and with weekly dexamethasone with cycle 2 and beyond. (A) Waterfall plot of maximal reduction in measurable disease. (B) Kaplan-Meier plot comparing event-free survival in the 2 cohorts. (C) Kaplan-Meier plot comparing overall survival in the 2 cohorts.

As of the data cutoff of March 31, 2014, 21 patients had died: 10 in cohort 1 and 11 in cohort 2. There were no deaths directly attributed to treatment-related toxicity. Both cohorts experienced similar event-free survival (4.3 vs 5.3 months; P = .59) and overall survival (OS; 21.7 vs 17.7 months; P = .98; Figure 1B-C).

Analysis of prognostic factors

Baseline features including age, sex, immunoglobulin (Ig)H type, IgL type, and recent Len-containing regimen, or adverse cytogenetics did not differ between responders and nonresponders (supplemental Table 1). Overall response rate in the cohort with Len/Bort double refractory disease was 32% and did not differ from patients without previously documented bortezomib resistance. Univariate analysis of factors associated with survival identified the level of serum β-2 microglobulin (hazard ratio [HR], 1.98; P = .0001) and albumin (HR, 0.37; P = .06) and the absence of deletion 17 (HR, 0.2; P = .03) associated with OS in treated patients (Table 2).

Prognostic factors associated with overall survival

| Variable . | P value* . | Hazard ratio . |

|---|---|---|

| Age | .5588 | 0.985 |

| Serum B2 microglobulin at study entry | .0001 | 1.986 |

| Serum albumin on entry | .0636 | 0.373 |

| Lines of prior therapy | .1870 | 1.172 |

| Female sex | .4030 | 1.447 |

| IGH type (IgG) | .6498 | 1.259 |

| IgL type | .9692 | 1.019 |

| Len as most recent therapy | .3310 | 1.555 |

| Cytogenetics:-lack of deletion 13 | .3400 | 0.644 |

| Cytogenetics: lack of Chr 1q abnormalities | .0806 | 0.460 |

| Cytogenetics: lack of deletion 17p | .0367 | 0.291 |

| Not double (Len + bortezomib) refractory | .2458 | 0.420 |

| Variable . | P value* . | Hazard ratio . |

|---|---|---|

| Age | .5588 | 0.985 |

| Serum B2 microglobulin at study entry | .0001 | 1.986 |

| Serum albumin on entry | .0636 | 0.373 |

| Lines of prior therapy | .1870 | 1.172 |

| Female sex | .4030 | 1.447 |

| IGH type (IgG) | .6498 | 1.259 |

| IgL type | .9692 | 1.019 |

| Len as most recent therapy | .3310 | 1.555 |

| Cytogenetics:-lack of deletion 13 | .3400 | 0.644 |

| Cytogenetics: lack of Chr 1q abnormalities | .0806 | 0.460 |

| Cytogenetics: lack of deletion 17p | .0367 | 0.291 |

| Not double (Len + bortezomib) refractory | .2458 | 0.420 |

Wald test.

Toxicity

The most common toxicity observed following Pom/Dex was myelo-suppression (supplemental Table 2). The incidence of treatment-related grade 3/4 adverse effects was greater in cohort 2 than cohort 1 (90% vs 58%, P = .03). The pattern of specific toxicities did not significantly differ between cohorts (supplemental Table 2). The incidence of grade 3/4 adverse effects did not differ based on age or number of lines of prior therapy (data not shown).

Immunologic studies

Therapy-induced changes in immune profile and function

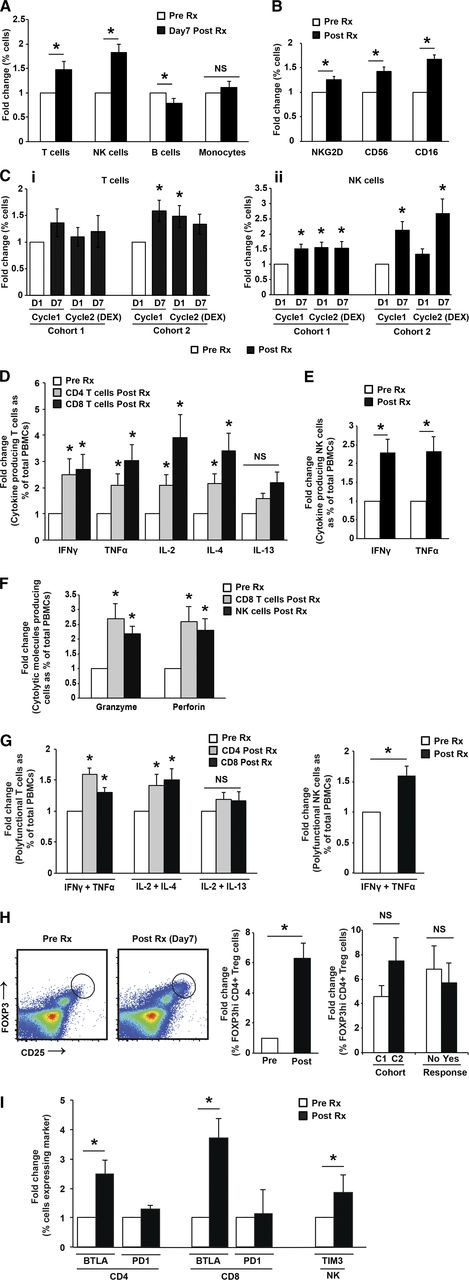

Compared with baseline, Pom therapy led to an increase in T cells (particularly cohort 2) and NK cells, along with a decrease in B cells detected as early as 7 days after initiating therapy (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 2A). Pom therapy also led to an increase in the expression of CD16, CD56, and NKG2D on NK cells, consistent with therapy-induced activation of NK cells (Figure 2B; supplemental Figure 2B). There was no difference in the relative increase in T cells or NK cells between cohort 1 and 2, indicating that the 2 dose levels had comparable effects in vivo (Figure 2C; supplemental Figure 2C). Analysis of serial samples revealed that the effects on NK cells were cyclic in cohort 2 and returned closer to baseline before each cycle of therapy. Comparison of changes following cycle 2 (Pom+Dex) compared with cycle 1 (Pom alone) indicated that the addition of Dex did not inhibit the therapy-induced increase in NK cells, although the effects on T cells were partially blunted, particularly in cohort 2. Therefore, both dosing schedules of Pom (±Dex) led to a distinct pattern but comparable degree of immune activation in vivo.

Mid-cycle changes in treatment-induced immune profile following Pom therapy. (A-C) Phenotypic and numeric changes in immune cells. (A) Changes in T, NK, B, and monocytes at baseline and 1 week after therapy. (B) Changes in the expression of NKG2D, CD16, and CD56 on NK cells at baseline and after 1 week of therapy. (C) Fold change (compared with baseline) in T cells (i) and NK cells (ii) at 1 week after initiation of therapy in patients with a 28/28-day schedule (cohort 1) or a 21/28-day schedule (cohort 2) at 7 days following initiation of therapy in cycle 1 (Pom alone) or with dexamethasone (cycle 2). (D-G) Changes in functional properties of T and NK cells. (D) Changes in cytokine profile of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. Intracellular cytokine production by CD4/CD8+ T cells was analyzed by flow cytometry at baseline vs 7 days after initiation of therapy. (E) Changes in cytokine profile of NK cells. Intracellular cytokine production by NK cells was analyzed by flow cytometry at baseline vs 7 days after initiation of therapy. (F) Changes in cytolysis proteins in T and NK cells. Expression of granzymeB and perforin by NK and CD8+ T cells was analyzed by flow cytometry at baseline vs 7 days after initiation of therapy. (G) Changes in polyfunctional T cells. Intracellular cytokine production by CD4/CD8+ T cells was analyzed by flow cytometry at baseline vs 7 days after initiation of therapy. (H) Changes in CD25hi FOXP3hi Tregs. Changes in circulating CD25hiFOXP3hi Tregs following Pom therapy were analyzed by flow cytometry. (Left) Representative FACS plot. (Center) Summary of changes before and after therapy. (Right) Comparison of changes following cycles 1 and 2. (I) Changes in coinhibitory receptors. Changes in the expression of BTLA, PD1, and Tim3 on CD4/CD8+ T or NK cells at baseline and after 1 week of therapy.

Mid-cycle changes in treatment-induced immune profile following Pom therapy. (A-C) Phenotypic and numeric changes in immune cells. (A) Changes in T, NK, B, and monocytes at baseline and 1 week after therapy. (B) Changes in the expression of NKG2D, CD16, and CD56 on NK cells at baseline and after 1 week of therapy. (C) Fold change (compared with baseline) in T cells (i) and NK cells (ii) at 1 week after initiation of therapy in patients with a 28/28-day schedule (cohort 1) or a 21/28-day schedule (cohort 2) at 7 days following initiation of therapy in cycle 1 (Pom alone) or with dexamethasone (cycle 2). (D-G) Changes in functional properties of T and NK cells. (D) Changes in cytokine profile of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. Intracellular cytokine production by CD4/CD8+ T cells was analyzed by flow cytometry at baseline vs 7 days after initiation of therapy. (E) Changes in cytokine profile of NK cells. Intracellular cytokine production by NK cells was analyzed by flow cytometry at baseline vs 7 days after initiation of therapy. (F) Changes in cytolysis proteins in T and NK cells. Expression of granzymeB and perforin by NK and CD8+ T cells was analyzed by flow cytometry at baseline vs 7 days after initiation of therapy. (G) Changes in polyfunctional T cells. Intracellular cytokine production by CD4/CD8+ T cells was analyzed by flow cytometry at baseline vs 7 days after initiation of therapy. (H) Changes in CD25hi FOXP3hi Tregs. Changes in circulating CD25hiFOXP3hi Tregs following Pom therapy were analyzed by flow cytometry. (Left) Representative FACS plot. (Center) Summary of changes before and after therapy. (Right) Comparison of changes following cycles 1 and 2. (I) Changes in coinhibitory receptors. Changes in the expression of BTLA, PD1, and Tim3 on CD4/CD8+ T or NK cells at baseline and after 1 week of therapy.

Therapy-induced functional changes in T and NK cells in vivo

An important property of immunomodulatory compounds is their capacity to enhance costimulation of T cells.36 Accordingly, we analyzed whether Pom therapy led to an increase in cytokine production and lytic granules by T cells and NK cells in vivo (Figure 2D-E). Pom therapy led to increased production of multiple lineage cytokines by T cells: interferon-γ, TNFα, IL2, and IL4 by CD4 and CD8 T cells and TNFα and IFNγ by NK cells. Pom therapy also led to increased expression of cytolysis genes, granzymeB and perforin, by CD8 T cells, as well as NK cells (Figure 2F). Pom therapy also led to an increase in polyfunctional T/NK cells producing both TNFα and IFNγ (Figure 2G). Together these data demonstrate that Pom therapy leads to a distinct poly-functional immune response in vivo that includes multiple lineages and lytic molecules (supplemental Figure 2D-G). Paired evaluation of marrow infiltrating T/NK cells before and after therapy also revealed a treatment-emergent increase in cytokine production by T and NK cells in the marrow (including polyfunctional T and NK cells), as well as increase in perforin in CD8+ T cells and granzyme in both CD8 and NK cells in the bone marrow (supplemental Figure 3A-C). Therefore, Pom therapy leads to functional activation of both circulating and bone marrow infiltrating T and NK cells.

Changes in coinhibitory receptors in vivo

Understanding immune checkpoints/suppressive factors following immune activation is essential to optimize drug-mediated immune activation. Pom therapy led to an increase in CD25hiFOXP3+ regulatory T cells (Figure 2H) and increased proportion of BTLA+ T cells and Tim-3+ NK cells, but no change in PD1+ T cells (Figure 2I; supplemental Figure 2I). Pom-mediated increase in BTLA expression was also observed in bone marrow-infiltrating T cells (supplemental Figure 3D). Therefore, the major coinhibitory molecules induced by Pom are BTLA and Tim-3 on T cells and NK cells, respectively.

Changes in gene expression in the tumor microenvironment in vivo

Pom/Len induce diverse effects on the tumor microenvironment (TME); however, few studies have used genome-wide approaches to study these changes in vivo. Therefore, we analyzed changes in gene expression in purified CD138− cells from paired bone marrow samples before and after Pom therapy using microarray analysis. A list of the top 50 differentially expressed genes following Pom therapy is listed in supplemental Table 3. Gene Ontology analysis of the top differentially expressed genes revealed that immune related genes are the major pathways altered following Pom therapy (supplemental Table 4). Notably, increased expression of genes implicated in innate lymphocytes, such as zbtb16 (or PLZF),37 was observed following Pom therapy (supplemental Table 3). Therefore, immune genes are the dominant component of Pom-induced changes in TME.

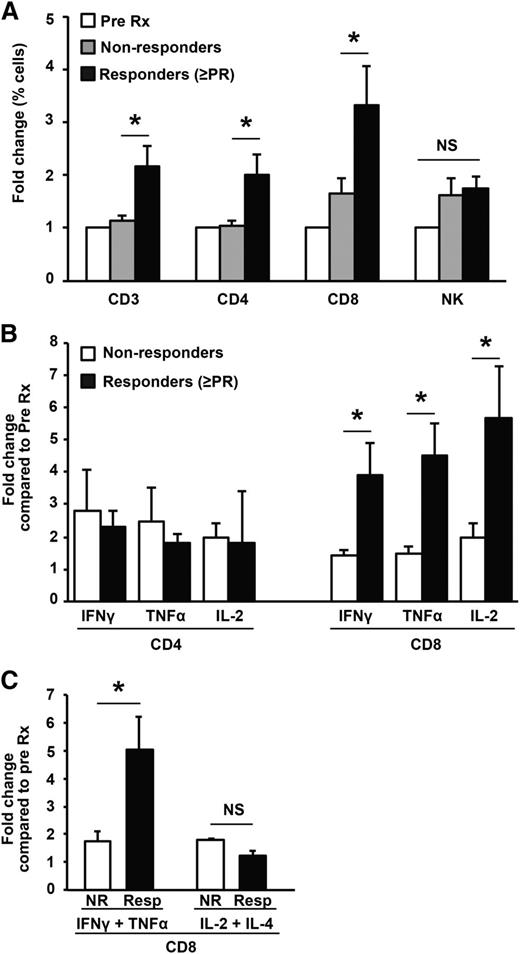

Correlation between profile of immune activation and clinical response to therapy

The capacity of Pom to mediate effects on several immune cells raises the question as to which, if any, of these changes correlate with clinical responses. Pom induced an increase in T cells (particularly CD8+T cells), but not NK cells, which correlated with the objective response to therapy (Figure 3A). Clinical response also correlated with the Pom-mediated increase in IFNγ- and TNFα-producing CD8+ T cells (Figure 3B) and polyfunctional T cells (Figure 3C). In contrast, changes in T cells producing other cytokines (such as IL13 and IL17), cytolysis-associated markers (granzyme, perforin), or FOXP3hi T-regulatory cells (Tregs) did not differ significantly between responders and nonresponders (data not shown). Similarly, changes in NK numbers or NK-cytokine production did not correlate with response (data not shown).

Correlation of immunologic effects following Pom and clinical response to therapy. (A) Changes in T and NK cells vs objective clinical response (≥PR). (B) Changes in cytokine production by T cells vs objective clinical response (≥PR). (C) Changes in cytokine production by polyfunctional CD8+ T cells vs objective clinical response (≥PR).

Correlation of immunologic effects following Pom and clinical response to therapy. (A) Changes in T and NK cells vs objective clinical response (≥PR). (B) Changes in cytokine production by T cells vs objective clinical response (≥PR). (C) Changes in cytokine production by polyfunctional CD8+ T cells vs objective clinical response (≥PR).

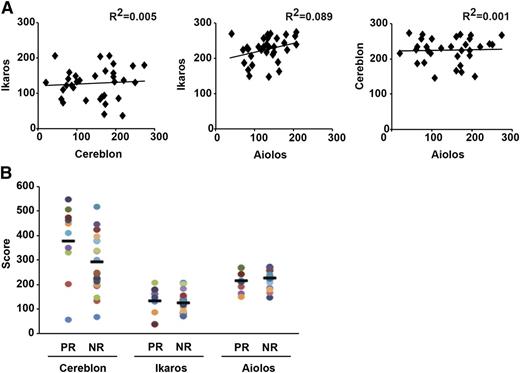

Correlation of cereblon, Ikaros (IKZF1), and Aiolos (IKZF3) expression in tumor cells with response to therapy

The ubiquitously expressed CUL4-CRBN E3 ligase has been identified as a major cellular target of IMiDs including Pom.18,21,24,25 CRBN expression in tumor cells was suggested as a biomarker of IMiD sensitivity.25,38,39 However, there is a need for validated assays to measure CRBN protein expression in bone marrow biopsies.32 It was recently shown that binding of IMiDs to CRBN leads to selective degradation of IKZF1 and IKZF3.21,26,27,31 However, whether the expression of these proteins in primary tumor cells correlates with response to Pom is unknown. To address this issue, we analyzed the expression of CRBN (cytoplasmic, nuclear, total), IKZF1 (nuclear), and IKZF3 (nuclear) in CD138+ tumor cells by IHC. The IHC data were independently scored by 3 pathologists and revealed high interobserver concordance for all 3 markers (data not shown). There was no correlation between the level of expression of any of the 3 proteins tested (Figure 4A). The expression of these proteins also did not differ in patients who had received Len as the most recent therapy before Pom (data not shown). Expression scores for IKZF1/IKZF3 did not differ between responders and nonresponders and objective tumor regressions were observed in patients with lowest recorded tumor H-scores for CRBN/IKZF1/IKZF3 (Figure 4B). H-score for CRBN (total, nuclear, or cytoplasmic) did show a trend with higher scores in responders but did not impact survival (supplemental Tables 5 and 6). In some prior studies, CRBN RNA was correlated with response to lenalidomide.25 There was a modest correlation between IHC scores and RNA levels for CRBN but not for IKZF1/3 (supplemental Table 7). RNA levels for CRBN/IKZF1/IKZF3 did not correlate with response/survival (supplemental Tables 8 and 9). An important aspect of study design was the use of single agent therapy for cycle 1. The percent change in measurable disease after cycle 1 correlated with baseline CRBN RNA and particularly cytoplasmic IHC scores, but not IKZF1/IKZF3 IHC scores or RNA levels (supplemental Tables 10 and 11).

Expression of cereblon, ikaros, and aiolos protein in tumor cells and its correlation with clinical response. Expression of these proteins in bone marrow biopsies at baseline at study entry was quantified by immunohistochemistry as an H-score. (A) Correlation between immunohistochemical H-scores for ikaros, cereblon, and aiolos protein expression in tumor cells. (B) Expression of ikaros, cereblon, and aiolos protein vs objective clinical response (≥PR).

Expression of cereblon, ikaros, and aiolos protein in tumor cells and its correlation with clinical response. Expression of these proteins in bone marrow biopsies at baseline at study entry was quantified by immunohistochemistry as an H-score. (A) Correlation between immunohistochemical H-scores for ikaros, cereblon, and aiolos protein expression in tumor cells. (B) Expression of ikaros, cereblon, and aiolos protein vs objective clinical response (≥PR).

Kinetics of changes in IKZF1 in immune cells after therapy

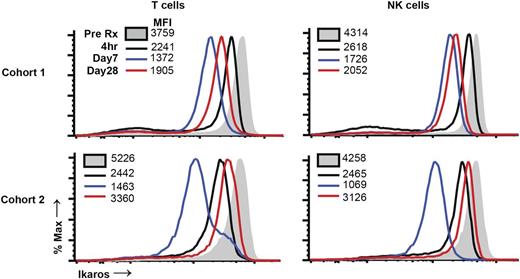

Pom led to degradation of IKZF1 in both tumor and T cells in culture.21,27 To study the kinetics of changes in Ikaros in immune cells following Pom therapy, we analyzed serial samples for the expression of IKZF1. Pom therapy led to Ikaros depletion in both T cells and NK cells, which was detected as early as 2 to 4 hours after dosing (Figure 5). Depletion of Ikaros in freshly isolated T cells was maximal at 1 week, but increased by day 28, irrespective of 21/28 or 28/28 dosing. In parallel experiments, we observed that activation of human T cells in culture leads to upregulation of Ikaros (data not shown). Together, these data demonstrate that Pom therapy leads to rapid reduction in Ikaros levels in immune cells in vivo but identify a possible feedback loop wherein drug-induced immune activation partially restores Ikaros levels.

Changes in ikaros levels in immune cells following Pom therapy. Pre- and posttherapy samples were thawed and analyzed together for the expression of intranuclear ikaros levels in T and NK cells by flow cytometry. Data are representative of 2 patients each in cohorts 1 and 2.

Changes in ikaros levels in immune cells following Pom therapy. Pre- and posttherapy samples were thawed and analyzed together for the expression of intranuclear ikaros levels in T and NK cells by flow cytometry. Data are representative of 2 patients each in cohorts 1 and 2.

Discussion

Pomalidomide has emerged as an effective therapy for relapsed/refractory MM and was tested in early phase clinical studies as either a continuous or intermittent dosing regimen.4-10 These data provide direct comparison of phamacodynamic properties of these dosing schedules that may have implications for optimal use of Pom in MM and as an immunomodulatory agent in MM and other settings. Intermittent dosing schedule, as currently approved for RRMM by the US Food and Drug Administration, led to overlapping OS/event-free survival curves compared with a lower-dose continuous schedule. The clinical data therefore bear some similarity to those reported by Leleu at al in a randomized phase 2 trial,9 and by Lacy et al in the context of sequentially treated cohorts.10 In our study, although the 21/28-day schedule led to a greater reduction in measurable disease (although the differences in overall response rate did not reach statistical significance), it also led to a greater incidence of grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events. Taken together, in our view, these data do not suggest a clear advantage for either regimen based on clinical parameters alone. A strength of this study is its randomized design, and its weakness is the relatively small sample size. Data from both regimens suggest a favorable impact of Pom on expected survival in this heavily pretreated population, and further studies are needed to evaluate the impact on quality of life.

An important and novel aspect of this study is the evaluation of the pharmacodynamics properties of the 2 regimens. Preclinical data have suggested immune-stimulatory properties of Pom in culture; however, data regarding Pom-mediated immune activation in vivo are limited.40 These data clearly demonstrate that even in the setting of heavily pretreated patients, both Pom/Dex dosing regimens lead to rapid activation of innate and adaptive immunity and reaffirm the importance of mid-cycle pharmacodynamic evaluation in Pom/Len trials.30 Indeed, the effects on NK cells with an intermittent Pom dosing regimen show clear periodicity and return closer to baseline before each cycle. The finding that both schedules lead to comparable early immune activation suggests that the lower Pom dose may be sufficient in clinical settings when used as an immune-modulator. Dexamethasone synergizes with Pom in terms of tumor regression; however, it also blunts Pom-mediated T-cell activation and supports consideration of a Pom combination with lower steroid dosing.

Clinical effects of immune activation may be enhanced by blockade of immune checkpoints.41-43 The finding that Pom leads to an increase in Tim-3 and BTLA4 in vivo sets the stage for further investigations of combinations of Pom with emerging antibodies against these targets.44 Drug-induced IKZF1 depletion has been implicated in enhanced IL2 transcription in T cells,27 and IKZF1 can regulate transcriptional silencing during T-lineage commitment.45,46 Therefore, drug-induced disruption of this axis in T cells may explain the poly-lineage effects that we observed. Analysis of serial samples identified rebound in IKZF1 levels in immune cells with ongoing therapy, which may represent a mechanism of acquired resistance to drug-induced immune activation. As this may be a direct consequence of immune activation itself, strategies such as drug holidays should be explored to restore IKZF1 depletion. Ikaros recovery with ongoing therapy may also provide support to intermittent dosing, although this needs further study.

These data also have implications for understanding the mechanism of antitumor effects of Pom in Len-refractory RRMM, the clinical setting wherein it is currently approved. The potential impact of prior Len therapy is particularly relevant as both Len and Pom share cereblon as a major cellular target. In recent elegant studies, Len and Pom were shown to mediate antiproliferative effects on MM tumor cells in culture via selective depletion of IKZF1 and IKZF3.21,26,27,47 However, the role of this axis in the effects of Pom in vivo in the clinic remains to be demonstrated. To our knowledge, this is the first study to concurrently examine the expression of IKZF1/IKZF3/cereblon (at the protein level) in tumor cells using validated assays in the context of Pom therapy. The trend between cereblon levels and response is consistent with this as a drug target. This is particularly true for correlation between cytoplasmic CRBN scores and percent reduction in measurable disease after cycle 1, indicating an early effect of single agent pomalidomide (supplemental Table 10). The expression of CRBN RNA or protein on tumor cells had a weaker association with objective responses and no association with survival following Pom/Dex, consistent with the possibility that pathways other than CRBN in tumor cells may contribute to outcome following this combination. In contrast to CRBN, baseline levels of IKZF1/IKZF3 in tumor cells did not correlate with response or survival. Further studies are needed to explore IKZF1-independent effects on tumor cells (including other cereblon-binding targets) or other effects on the tumor microenvironment.

Within TME, changes in immune-related genes emerged from a genome-wide analysis as the dominant pathway impacted by Pom in vivo. Drug-induced effects on the immune system are surprisingly rapid (within hours) and involve both innate and adaptive immunity. Gene array studies identified changes in several genes implicated in innate immunity. Of particular interest are genes such as PLZF, implicated in the biology of innate lymphocytes (such as natural killer T cells), indicating that the biology of innate lymphocytes in the context of Pom/Len therapy requires further study.29,30,37 A role for immune-mediated effects in the antitumor effects of Pom is also supported by the observed correlation of treatment-induced changes in CD8+ T cells (and their functional properties) with clinical response. Together, these data suggest that at least in the RRMM setting, the antitumor effects of Pom may be particularly dependent on changes in TME/immune cells. Optimizing the immune effects of Pom/Len on the TME with combination therapies may enhance their therapeutic potential in MM and other cancers.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of the clinical research staff at the Yale Clinical Trials Office for their help with this study.

M.V.D. and K.M.D. are supported in part by funds from the National Institutes of Health. These studies were also supported in part by funds from Celgene.

Authorship

Contribution: K.S. managed clinical data and analyzed data; R.D. performed experiments and analyzed data; L.Z. performed experiments and analyzed data; R.V. analyzed microarray data; Y.D. and X.Y. performed statistical analysis; M.K., S.S., and D.C. performed clinical research; J.V. performed data analysis; S.K. performed experiments; M.W., Y.R., S.C., D.H., M.B., and A.T. performed immunohistochemistry studies; K.M.D. designed and coordinated immune studies, analyzed data, and wrote paper; and M.V.D. designed and coordinated clinical studies, analyzed data, and wrote paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: Y.R., M.W., S.C., M.B., and A.T. are Celgene employees and D.H. is a consultant to Celgene. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Madhav Dhodapkar, Yale University School of Medicine, 333 Cedar St, New Haven, CT 06515; e-mail: madhav.dhodapkar@yale.edu; or Kavita Dhodapkar, Yale University School of Medicine, 333 Cedar St, New Haven, CT 06515; e-mail: kavita.dhodapkar@yale.edu.

References

Author notes

K.S. and R.D. contributed equally to this work.

K.M.D. and M.V.D. contributed equally to this work.