Abstract

Monitoring of minimal residual disease (MRD) has become routine clinical practice in frontline treatment of virtually all childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and in many adult ALL patients. MRD diagnostics has proven to be the strongest prognostic factor, allowing for risk group assignment into different treatment arms, ranging from significant treatment reduction to mild or strong intensification. Also in relapsed ALL patients and patients undergoing stem cell transplantation, MRD diagnostics is guiding treatment decisions. This is also why the efficacy of innovative drugs, such as antibodies and small molecules, are currently being evaluated with MRD diagnostics within clinical trials. In fact, MRD measurements might well be used as a surrogate end point, thereby significantly shortening the follow-up. The MRD techniques need to be sensitive (≤10−4), broadly applicable, accurate, reliable, fast, and affordable. Thus far, flow cytometry and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of rearranged immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor genes (allele-specific oligonucleotide [ASO]-PCR) are claimed to meet these criteria, but classical flow cytometry does not reach a solid 10−4, whereas classical ASO-PCR is time-consuming and labor intensive. Therefore, 2 high-throughput technologies are being explored, ie, high-throughput sequencing and next-generation (multidimensional) flow cytometry, both evaluating millions of sequences or cells, respectively. Each of them has specific advantages and disadvantages.

Introduction

Over the last decade (2005-2015), application of minimal residual disease (MRD) diagnostics in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) has expanded significantly from a limited number of study groups in Europe and the United States to worldwide application.1-9 Currently, virtually all pediatric ALL patients and a large part of adult ALL cases in Western countries are being monitored with MRD techniques to assess treatment effectiveness and assign patients to MRD-based risk groups.

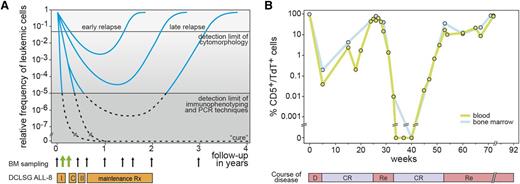

The first studies on MRD detection in ALL date back from the 1980s, using immunofluorescence microscopy (Figure 1A). Particularly in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), it appeared possible to accurately monitor the decrease and regrowth of leukemic cells (Figure 1B), because of the aberrant thymic immunophenotype of T-ALL cells in blood and bone marrow (BM), positive for a T-cell marker and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT).10,11 At that time, such a highly specific aberrant immunophenotype was not yet identified for B-cell precursor ALL (BCP-ALL), mainly because 2- or 3-color immunofluorescence microscopy could not detect small differences in marker expression. Furthermore, the expanded normal BCP population (so-called hematogones) in regenerating BM after intensive treatment blocks caused too much background for detection of BCP-ALL cells at low levels (<1% or <0.1%).12-14 Consequently many other technologies were evaluated for MRD detection, most of which appeared not to be sufficiently sensitive.15,16

Detection of MRD during follow-up of ALL patients. (A) Schematic diagram of relative frequencies of ALL cells in BM during and after treatment. I, induction treatment; C, consolidation treatment; II, reinduction treatment. The detection limit of cytomorphology and the detection limit of immunophenotyping and PCR techniques is indicated. (B) Follow-up of a T-ALL patient with CD5/TdT double immunofluorescence microscopy.58 The frequencies of the T-ALL cells in blood and BM are very comparable in this patient. D, diagnosis; CR, complete remission; Re, relapse.

Detection of MRD during follow-up of ALL patients. (A) Schematic diagram of relative frequencies of ALL cells in BM during and after treatment. I, induction treatment; C, consolidation treatment; II, reinduction treatment. The detection limit of cytomorphology and the detection limit of immunophenotyping and PCR techniques is indicated. (B) Follow-up of a T-ALL patient with CD5/TdT double immunofluorescence microscopy.58 The frequencies of the T-ALL cells in blood and BM are very comparable in this patient. D, diagnosis; CR, complete remission; Re, relapse.

Accurate and sensitive detection of low frequencies of ALL cells, ≤1 ALL cell in 10 000 normal cells (≤0.01% or ≤10−4), requires highly specific markers for discrimination between ALL cells and normal leukocytes in blood and BM, such as aberrant immunophenotypes, specific genetic aberrations, and/or specific immunoglobulin (IG) or T-cell receptor (TR) gene rearrangements, which are detectable by flow cytometry or polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based molecular techniques.

Classical MRD techniques

Over a period of 25 years, several PCR-based and flow cytometric (flow MRD) technologies have stepwise developed into routinely applicable MRD tools, particularly because of long-term international collaboration with open exchange of knowledge and experience and collaborative experiments.1,9,17-27 The principles and characteristics and the pros and cons of these MRD techniques are summarized below (Table 1).

Characteristics of the 3 classical MRD methods

| MRD technique . | Conventional flow cytometry . | RQ-PCR of IG/TR genes or breakpoint regions of . | RQ-PCR of fusion transcripts and other aberrances . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated sensitivity | 3-4 colors: 10−3-10−4 | 10−4-10−5 | 10−4-10−6 |

| 6-8 colors: 10−4 | |||

| Applicability | BCP-ALL: >90% | BCP-ALL: 95% | BCP-ALL: 25-40% (age dependent) |

| T-ALL: >90% | T-ALL: 90-95% | T-ALL: 10-15% | |

| Advantages | Fast Analysis at cell population level or single cell level Easy storage of data Information about the whole sample cellularity | Applicable in virtually all BCP-ALL and T-ALL Sensitive Well standardized + regular international QA rounds | Relatively easy Sensitive Applicable for specific leukemia subgroups, such as BCR-ABL or MLL-AF4 |

| Disadvantages | Variable sensitivity, because of similarities between normal (regenerating) cells and malignant cells Limited standardization, no QA results | Time-consuming Expensive Requires extensive experience and knowledge | Limited standardization (only harmonization) Limited QA rounds (with conversion factors) Limited applicability in ALL (absence of targets in >50% of cases) Risk of contamination |

| MRD technique . | Conventional flow cytometry . | RQ-PCR of IG/TR genes or breakpoint regions of . | RQ-PCR of fusion transcripts and other aberrances . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated sensitivity | 3-4 colors: 10−3-10−4 | 10−4-10−5 | 10−4-10−6 |

| 6-8 colors: 10−4 | |||

| Applicability | BCP-ALL: >90% | BCP-ALL: 95% | BCP-ALL: 25-40% (age dependent) |

| T-ALL: >90% | T-ALL: 90-95% | T-ALL: 10-15% | |

| Advantages | Fast Analysis at cell population level or single cell level Easy storage of data Information about the whole sample cellularity | Applicable in virtually all BCP-ALL and T-ALL Sensitive Well standardized + regular international QA rounds | Relatively easy Sensitive Applicable for specific leukemia subgroups, such as BCR-ABL or MLL-AF4 |

| Disadvantages | Variable sensitivity, because of similarities between normal (regenerating) cells and malignant cells Limited standardization, no QA results | Time-consuming Expensive Requires extensive experience and knowledge | Limited standardization (only harmonization) Limited QA rounds (with conversion factors) Limited applicability in ALL (absence of targets in >50% of cases) Risk of contamination |

Quantitative PCR of IG-TR targets (DNA level)

Already in the early 1980s (1983-1984), the extensive repertoire of rearranged IG and TR genes was used for detection of relatively small lymphoid clones between many normal or reactive lymphoid cells; for example, to assess clonality in suspected lymphoproliferations and the clonal relationship between 2 or more lymphoid malignancies in the same patient.28,29 At that time, classical Southern blotting was used, which appeared to be not sufficiently sensitive (5-10%) for MRD detection.29 This changed in the late 1980s with the invention of the PCR technique: from 1989 to 1991 onward, many laboratories started to use PCR analysis of IG-TR gene rearrangements for clonality assessment and MRD detection.30-33 Whereas Southern blotting takes advantage of the combinatorial repertoire (different combinations of rearranged V, D, and J genes), the PCR technique is mainly focused on the highly diverse size and composition of the junctional regions (Figure 2A), resulting in higher sensitivities.33 Particularly when oligonucleotide primers were designed complementary to the individual junctional region sequences, high sensitivities of 10−4 to 10−5 could be reached.34 This so-called allele-specific oligonucleotide (ASO)-PCR was further improved by the introduction of real-time quantitative PCR (RQ-PCR) technologies in 1997 to 1998, which use fluorescently labeled probes as a reading system for improved quantitation (Figures 2B-C).34-37

Basic principles of RQ-PCR–based MRD analysis using rearranged IG and TR genes as targets. (A) Schematic diagram of an IGH gene rearrangement, resulting in a V-D-J exon with highly diverse junctional regions, which differ in each individual B cell, even if by coincidence the same V, D, and J genes are used. (B) RQ-PCR analysis of an dilution experiment, showing the technical definitions for interpretation of RQ-PCR results.18 The amplification plot shows the position of the threshold and obtained Ct values, the quantitative range, the sensitivity, and the background signal. (C) Example of RQ-PCR MRD analysis using an Vδ2-Dδ2-Jα11 rearrangement as target.44 One primer and the TaqMan probe are positioned at the Vδ2 gene and the other primer is an ASO primer, positioned at the Vδ2-Dδ2 junctional region. The amplification plot (right) shows the dilution experiment and the follow-up sample (in triplicate). The corresponding standard curve (left) is based on the dilution experiment and allows calculation of the ALL cell frequency in the follow-up sample.

Basic principles of RQ-PCR–based MRD analysis using rearranged IG and TR genes as targets. (A) Schematic diagram of an IGH gene rearrangement, resulting in a V-D-J exon with highly diverse junctional regions, which differ in each individual B cell, even if by coincidence the same V, D, and J genes are used. (B) RQ-PCR analysis of an dilution experiment, showing the technical definitions for interpretation of RQ-PCR results.18 The amplification plot shows the position of the threshold and obtained Ct values, the quantitative range, the sensitivity, and the background signal. (C) Example of RQ-PCR MRD analysis using an Vδ2-Dδ2-Jα11 rearrangement as target.44 One primer and the TaqMan probe are positioned at the Vδ2 gene and the other primer is an ASO primer, positioned at the Vδ2-Dδ2 junctional region. The amplification plot (right) shows the dilution experiment and the follow-up sample (in triplicate). The corresponding standard curve (left) is based on the dilution experiment and allows calculation of the ALL cell frequency in the follow-up sample.

The first large-scale PCR-based MRD studies were performed in childhood ALL, using IGH (VH-JH), TRG, and TRD gene rearrangements as PCR targets, mainly because of the limited number of primers needed to detect these rearrangements.1,2 Soon it appeared that multiple IGH and TRD gene rearrangements occur in a substantial fraction (25-40%) of BCP-ALL patients (Table 2), implying that multiple subclones (with different IG-TR rearrangements) are present.38,39 Such subclones might differ in treatment response. Indeed, clonal evolution with changed IG-TR rearrangement patterns at relapse particularly occurs in patients with oligoclonal rearrangements at initial diagnosis (Table 2).39,40 Because of several European collaborations (BIOMED-1, International Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster Study Group (I-BFM-SG), and BIOMED-2 Concerted Actions), additional PCR targets could be introduced to solve at least part of the oligoclonality issue, such as IGK, TRB, incomplete IGH (DH-JH), and unusual TRD (Vδ2-Jα) rearrangements.37,41-45 Because of these additional targets, the majority of ALL patients (90-95%) can now be monitored with ≥2 sensitive MRD-PCR targets (Table 2).18,37 Since 2001, the RQ-PCR MRD method has been attuned between ∼60 diagnostic laboratories worldwide (www.EuroMRD.org) and is subjected to biannual international quality assurance (QA) rounds (27th QA round is currently ongoing).

Frequencies and stability of MRD-PCR targets in childhood BCP-ALL and T-ALL

| Gene . | Rearrangement type . | Precursor-B-ALL . | T-ALL . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency . | Oligoclonality . | Stability . | Frequency . | Stability . | |||

| Monoclonal . | Oligoclonal . | ||||||

| IGH | VH-JH | 93% | 30-40% | 88% | 47% | 5% | NT |

| DH-JH | 20% | 50-60% | 57% | 38% | 23% | NT | |

| Total IGH | 98% | ∼40% | 85% | 44% | 23% | NT | |

| IGK | Vκ-Kde | 45% | 5-10% | 95% | 40% | 0% | NA |

| Intron RSS-Kde | 25% | 5-10% | 86% | 0% | 0% | NA | |

| Total Kde | 50% | 5-10% | 95% | 40% | 0% | NA | |

| TRB | Vβ-Jβ | 21% | 10-15% | 89% | 60% | 77% | 79% |

| Dβ-Jβ | 14% | 10-15% | 67% | 0% | 55% | 80% | |

| Total TRB | 33% | 10-15% | 81% | 43% | 92% | 80% | |

| TRG | Vγ-Jγ | 55% | ∼15% | 75% | 95% | 86% | |

| TRD | Vδ-Jδ or Dδ-Jδ1 | <1% | NA | NA | NA | 50% | 100% |

| Vδ2-Dδ3 or Dδ2-Dδ3 | 40% | 20-25% | 86% | 26% | 55% | 100% | |

| Total TRD | 40% | 20-25% | 86% | 26% | 55% | 100% | |

| TRD/A | Vδ2-Jα | 46% | ∼45% | 86% | 43% | NT | NT |

| Gene . | Rearrangement type . | Precursor-B-ALL . | T-ALL . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency . | Oligoclonality . | Stability . | Frequency . | Stability . | |||

| Monoclonal . | Oligoclonal . | ||||||

| IGH | VH-JH | 93% | 30-40% | 88% | 47% | 5% | NT |

| DH-JH | 20% | 50-60% | 57% | 38% | 23% | NT | |

| Total IGH | 98% | ∼40% | 85% | 44% | 23% | NT | |

| IGK | Vκ-Kde | 45% | 5-10% | 95% | 40% | 0% | NA |

| Intron RSS-Kde | 25% | 5-10% | 86% | 0% | 0% | NA | |

| Total Kde | 50% | 5-10% | 95% | 40% | 0% | NA | |

| TRB | Vβ-Jβ | 21% | 10-15% | 89% | 60% | 77% | 79% |

| Dβ-Jβ | 14% | 10-15% | 67% | 0% | 55% | 80% | |

| Total TRB | 33% | 10-15% | 81% | 43% | 92% | 80% | |

| TRG | Vγ-Jγ | 55% | ∼15% | 75% | 95% | 86% | |

| TRD | Vδ-Jδ or Dδ-Jδ1 | <1% | NA | NA | NA | 50% | 100% |

| Vδ2-Dδ3 or Dδ2-Dδ3 | 40% | 20-25% | 86% | 26% | 55% | 100% | |

| Total TRD | 40% | 20-25% | 86% | 26% | 55% | 100% | |

| TRD/A | Vδ2-Jα | 46% | ∼45% | 86% | 43% | NT | NT |

Nevertheless, the ASO-RQ-PCR MRD method requires extensive knowledge and experience and is laborious and time-consuming. Detection and sequencing of the IG-TR rearrangements at diagnosis and design of the corresponding ASO primers takes 3 to 4 weeks, whereas analysis of follow-up samples takes ∼1 week.18,26

Classical multicolor (4- to 6-color) flow MRD

In parallel to the ASO-RQ-PCR methods, flow cytometry was explored as a less labor-intensive and faster MRD technique, when 4- and 6-color cytometers became available in 1998 to 2002 (Table 1).3,8,17,46-49 These multicolor approaches followed classical concepts with emphasis on the detection of aberrant immunophenotypes in the “empty spaces” (not overlapping with normal leukocytes) in 2-dimensional dot plots, particularly based on the experience of the BIOMED-1 Concerted Action.17,19,47-49 Indeed, fair sensitivities were reached, but many comparative flow PCR studies consistently showed that classical flow MRD did not reach a sensitivity below 10−4 in the majority of ALL cases.50-53 This appeared particularly difficult at the postinduction time points when regenerating BCP cells (hematogones) are abundantly present,13,14 making it complicated to identify low frequencies of BCP-ALL cells.50-53

Another disadvantage of classical flow MRD is that the applied immunostaining protocols, antibody panels, and gating strategies differ significantly between centers and between treatment protocols and are in fact highly subjective expert procedures. Consequently, results of flow-based MRD methods have much less interlaboratory comparability than PCR-based methods.

RQ-reverse transcriptase-PCR of fusion gene transcripts

PCR methods for detection of fusion gene transcripts became an important MRD tool in myeloid leukemias (particularly in BCR-ABL+ chronic myeloid leukemia and PML-RARA+ acute promyelocytic leukemia), as well as in BCR-ABL+ adult ALL, because of its age-related high frequency.54-56 In childhood ALL, RQ-reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR is much less used, albeit that it can have added value in specific well-defined subgroups such as BCR-ABL-ALL.54,55 The RQ-RT-PCR methods are sensitive (10−4-10−6) and relatively easy to perform with standardized PCR protocols and primer-probe sets already available for more than a decade.54,57 Nevertheless, full standardization of all steps and international QA systems are not yet available (Table 1). Based on the experience of the IG-TR targets, the BCR-ABL section of the EuroMRD Consortium tries to come with solutions (H. Pfeifer, G. Cazzaniga, V. H. J. van der Velden, J. M. Cayuela, B. Schäfer, O. Spinelli, S. Akiki, S. Avigad, I. Bendit, K. Borg, H. Cavé, L. Elia, J. Gastier-Foster, G. Gerrard, S. Hayette, M. Herrmansson, A. Juh, T. Jurcek, M. González, C. Homburg, I. Iaccobucci, V. Keiristo, T. Lange, T. Lion, M. C. Mueller, F. Pane, L. Rai, S. Röttgers, T. Sacha, S. Schnittger, T. Touloumenidou, H. Vaalerhaugen, P. Van den Berghe, J. Zuna, E. Herrmann, S. Markovic, O. G. Ottmann, J. J. M. van Dongen, unpublished data, 2015).

Sample requirements

Monitoring of BM samples and not blood samples

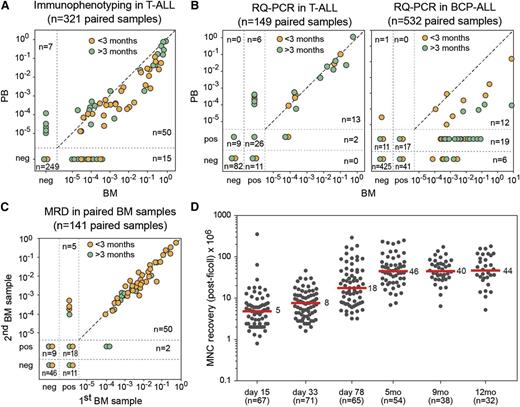

Early microscopic MRD studies in T-ALL suggested that blood samples might be used instead of more invasive and traumatic BM samples (Figures 1B and 3A).58 Subsequently, several large-scale clinical studies evaluated MRD levels in paired blood/BM samples in both BCP-ALL and T-ALL.59-61 These studies confirmed that blood MRD levels in T-ALL patients were comparable or up to 1 log lower than in BM (Figure 3B). However, in BCP-ALL patients, blood MRD levels were 1 to 3 logs lower than in BM (Figure 3B), making MRD studies via blood sampling impossible in BCP-ALL patients.59-61 Consequently, for both BCP-ALL and T-ALL patients, BM sampling is a prerequisite.

ALL cell frequencies in blood and BM samples during follow-up. (A) Frequencies of T-cell marker+/TdT+ T-ALL cells, as detected by immunofluorescence microscopy in 321 paired blood and BM samples, obtained from 26 patients.58,60 The T-ALL cell frequencies are comparable in many pairs, but differences can occur up to 1 log. Orange, sample <3 months of follow-up; green, >3 months of follow-up. (B) (Left) Frequencies of ALL cells in 149 paired blood and BM samples from 22 T-ALL patients, analyzed by RQ-PCR of TR gene rearrangements and TAL1 deletions.60 A strong correlation was observed between the blood and BM frequencies in T-ALL. (Right) Frequencies of ALL cells in 532 paired blood and BM samples from 62 BCP-ALL patients, analyzed by RQ-PCR of IG and TR gene rearrangements.60 The MRD levels were significantly higher in BM compared with blood. Moreover, the ratio between the MRD levels in BM and blood was highly variable, ranging from 1 to 3 logs. Orange, sample <3 months of follow-up; green, >3 months of follow-up. (C) Frequencies of ALL cells in 141 paired BM samples (left-right) from 26 patients, showing a very high concordance.62 Only in case of very low MRD levels was variation seen, mainly because of levels outside the quantitative range of the RQ-PCR assay. Orange, sample <3 months of follow-up; green, >3 months of follow-up. (D) Recovery of BM mononuclear cells after ficoll density centrifugation at different time points during follow-up in the DCOG-ALL11 protocol. Recovery of mononuclear cells is relatively low at days 33 and 78 (median, 5-8 × 106). Recovery at day 78 and at later time points is much higher (median, 18-40 × 106).

ALL cell frequencies in blood and BM samples during follow-up. (A) Frequencies of T-cell marker+/TdT+ T-ALL cells, as detected by immunofluorescence microscopy in 321 paired blood and BM samples, obtained from 26 patients.58,60 The T-ALL cell frequencies are comparable in many pairs, but differences can occur up to 1 log. Orange, sample <3 months of follow-up; green, >3 months of follow-up. (B) (Left) Frequencies of ALL cells in 149 paired blood and BM samples from 22 T-ALL patients, analyzed by RQ-PCR of TR gene rearrangements and TAL1 deletions.60 A strong correlation was observed between the blood and BM frequencies in T-ALL. (Right) Frequencies of ALL cells in 532 paired blood and BM samples from 62 BCP-ALL patients, analyzed by RQ-PCR of IG and TR gene rearrangements.60 The MRD levels were significantly higher in BM compared with blood. Moreover, the ratio between the MRD levels in BM and blood was highly variable, ranging from 1 to 3 logs. Orange, sample <3 months of follow-up; green, >3 months of follow-up. (C) Frequencies of ALL cells in 141 paired BM samples (left-right) from 26 patients, showing a very high concordance.62 Only in case of very low MRD levels was variation seen, mainly because of levels outside the quantitative range of the RQ-PCR assay. Orange, sample <3 months of follow-up; green, >3 months of follow-up. (D) Recovery of BM mononuclear cells after ficoll density centrifugation at different time points during follow-up in the DCOG-ALL11 protocol. Recovery of mononuclear cells is relatively low at days 33 and 78 (median, 5-8 × 106). Recovery at day 78 and at later time points is much higher (median, 18-40 × 106).

Homogeneous distribution of ALL cells over BM during first-line treatment

For a long time it has been speculated that ALL is relatively homogenously distributed over BM at diagnosis but that treatment might cause differential degrees of tumor load decrease in different parts of the BM compartment, which might result in different MRD levels in different BM aspirates during follow-up. Therefore, we performed 141 paired (left-right) BM studies in 26 patients during the first year of treatment, showing highly concordant results between the paired BM samples (Figure 3C).62 Consequently no signs for unequal distribution of ALL cells were found during ALL treatment.

How many cells are needed for reliable MRD measurements?

Sensitivities of ≤10−4 require sufficient numbers of BM cells. The early childhood ALL MRD studies already revealed that only the first BM aspirate should be used because of significant dilution by blood contamination in subsequent aspirates at the same spot. For the same reason, aspiration of large volumes is also discouraged: it is advised to collect ≥2 mL but ≤5 mL of the first BM aspirate. RQ-PCR–based MRD studies require, for each follow-up time point, ≥2 × 106 cells, which is sufficient to extract ≥6 μg of DNA, needed for analysis of ≥2 MRD-PCR targets in triplicate and the control gene in duplicate.18 Please note that generally only 50% of DNA is recovered from the theoretical 13 μg of DNA, present in 2 × 106 cells. Current flow cytometric MRD studies require even more cells: ≥5 × 106 cells (see later).

The cell recovery is related to the time point, with low cell yields at days 15 and 33 but higher cell yields at day 79 and later time points (Figure 3D). The lower cell yields at day 15 are generally not a problem, because at that time, most patients still have clearly detectable MRD levels. Lack of sufficient cells at day 33 is more a problem, because at that time, it is important to identify patients with undetectable MRD levels, using MRD-PCR targets with a quantitative range of ≤10−4. Consequently, appropriate BM sampling is a critical part of MRD-based clinical studies.

Clinical application of MRD diagnostics

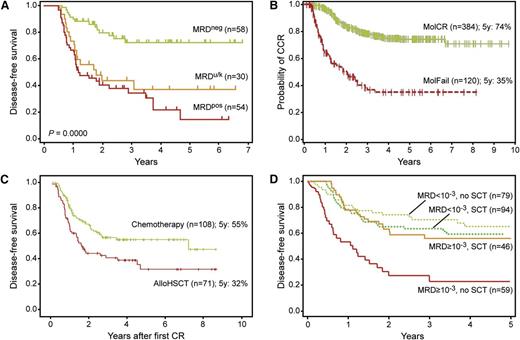

MRD diagnostics has proven to be the strongest prognostic factor, allowing for risk group assignment into different treatment arms, ranging from low-risk/standard-risk with treatment reduction to medium-risk or high-risk with mild or strong intensification, respectively. The large-scale Associazione Italiana di Ematologia Oncologia Pediatrica and the Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia 2000 (AIEOP-BFM-ALL 2000) studies have shown that MRD-based treatment strategies further improve outcome in the involved patients, both in BCP-ALL and T-ALL patients (Figure 4).1,63,64 The United Kingdom ALL (UKALL)-2003 randomized controlled trial demonstrated that treatment can be reduced in MRD-based low-risk patient,65 and can be augmented in MRD-high-risk patients albeit at the cost of more adverse events.66 These MRD-based results look promising and form the basis for further attempts to improve the overall outcome of ALL treatment, preferably with reduced toxicity. However, clinical trials with MRD-based treatment strategies require reliable MRD results for the vast majority of all included patients (90-95%); otherwise, selection bias might be introduced. This appears to be a challenge in large-scale clinical trials. In addition, the definition of the MRD cutoff levels should be attuned between different clinical trials (see later).

Long-term follow-up in childhood ALL patients, classified according to MRD measurements. (A) Disease-free survival of 129 ALL patients, classified according to 3 MRD-based risk groups in the International BFM study.1 Patients were classified as MRD-low-risk if no MRD was detected at day 33 (TP1) and at day 78 (TP2); patients with MRD ≥10−3 at TP2 were classified as MRD-high-risk; all other patients had MRD <10−3 at TP2 and were classified as MRD-intermediate-risk. (B) Disease-free survival of 54 infant ALL cases, treated according to the INTERFANT-99 treatment protocol.67 Patients were considered MRD-high-risk if the MRD level at TP3 was ≥10−4; patients were considered MRD-low-risk if MRD levels were <10−4 at both time points; all remaining patients were considered MRD-medium-risk. Only 3 of 24 MRD-low-risk patients relapsed, whereas all 14 MRD-high-risk patients relapsed. (C) Event-free survival of 3184 BCP-ALL patients of the AEIOP-BFM 2000 study (with kind permission by Dr V. Conter, Monza, Italy).63 Patients were classified as MRD-standard-risk (SR) if no MRD was detected at day 33 (TP1) and at day 78 (TP2) and as MRD-intermediate-risk (IR) when MRD was positive at 1 or both TPs but <10−3 at TP2. Patients with MRD ≥10−3 at TP2 were classified as MRD-high-risk (HR). (D) Event-free survival of 464 T-ALL patients of the AEIOP-BFM-ALL 2000 study (with kind permission by M. Schrappe, Kiel, Germany).64 The MRD-based classification is the same as for C.

Long-term follow-up in childhood ALL patients, classified according to MRD measurements. (A) Disease-free survival of 129 ALL patients, classified according to 3 MRD-based risk groups in the International BFM study.1 Patients were classified as MRD-low-risk if no MRD was detected at day 33 (TP1) and at day 78 (TP2); patients with MRD ≥10−3 at TP2 were classified as MRD-high-risk; all other patients had MRD <10−3 at TP2 and were classified as MRD-intermediate-risk. (B) Disease-free survival of 54 infant ALL cases, treated according to the INTERFANT-99 treatment protocol.67 Patients were considered MRD-high-risk if the MRD level at TP3 was ≥10−4; patients were considered MRD-low-risk if MRD levels were <10−4 at both time points; all remaining patients were considered MRD-medium-risk. Only 3 of 24 MRD-low-risk patients relapsed, whereas all 14 MRD-high-risk patients relapsed. (C) Event-free survival of 3184 BCP-ALL patients of the AEIOP-BFM 2000 study (with kind permission by Dr V. Conter, Monza, Italy).63 Patients were classified as MRD-standard-risk (SR) if no MRD was detected at day 33 (TP1) and at day 78 (TP2) and as MRD-intermediate-risk (IR) when MRD was positive at 1 or both TPs but <10−3 at TP2. Patients with MRD ≥10−3 at TP2 were classified as MRD-high-risk (HR). (D) Event-free survival of 464 T-ALL patients of the AEIOP-BFM-ALL 2000 study (with kind permission by M. Schrappe, Kiel, Germany).64 The MRD-based classification is the same as for C.

Even within relatively homogeneous high-risk patient groups, such as infant ALL patients with MLL gene aberrations (Figure 4B), children with BCR-ABL1–like ALL, and Ph+-ALL treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors plus chemotherapy, MRD levels predict outcome in a comparable way as in childhood ALL.67-70 Only IKZF1 alterations (deletion or mutations) had added value in the MRD-based medium-risk group by identifying a subgroup of poor-prognosis patients.71

Also in relapsed ALL patients and in patients undergoing stem cell transplantation (SCT), MRD measurements identify good and poor responders and correlate with outcome.72-75 MRD diagnostics before allogeneic SCT in childhood ALL appeared to be the most important predictor for post-SCT outcome,73,74,76 whereas MRD measurements after SCT allows prediction of relapse.77,78 Consequently, MRD measurements are now guiding treatment decisions in childhood ALL patients undergoing SCT.79,80

Because of its high prognostic value, MRD diagnostics are currently also used for evaluation of treatment effectiveness in clinical trials with innovative drugs, such as antibodies and small molecules. At the international hematology congresses of the last 2 years, virtually all ALL clinical trials with novel drugs appeared to have implemented MRD diagnostics for treatment evaluation.81-84 In these clinical trials, MRD measurements might well be used as a surrogate end point, thereby shortening the clinical trials significantly.85 If so, the novel drugs will become faster available for the patients at affordable prices.

MRD-based risk group assignment vs continuous monitoring

Already in the early 1990s, it became clear that early prediction of relapse in childhood ALL via continuous monitoring is too laborious and not feasible in routine practice. The first reason is that remission duration is highly variable, with only 35% of all childhood BCP-ALL relapses occurring during the 2-year period of treatment, whereas 95% of all childhood T-ALL relapses occur during treatment.86 Second, the kinetics of leukemic cell regrowth in childhood ALL appeared to differ between patients from gradual regrowth over multiple months to rapid progression in only a few weeks.58,87 Therefore, the MRD monitoring results in childhood ALL appeared too variable to design effective strategies for early treatment intervention, such as early relapse treatment. In the late 1990s, several large-scale clinical studies evaluated MRD levels in BM at multiple time points during treatment to evaluate the effectiveness of individual treatment blocks in the eradication of the ALL cells.1-3 These studies showed that MRD measurements in the first 3 months of treatment are most informative for MRD risk group assignment in childhood ALL.1-3

In adult ALL, postremission MRD monitoring for early detection of relapse seems to be more feasible, because of the shorter remission duration.5,6 In a prospective German Multicenter ALL Study Group (GMALL) study, MRD-negative patients reconverted to quantifiable MRD positivity a median time of 4.1 months before clinical relapse, supporting the concept that hematologic relapse can be predicted by MRD.5 Therefore, a 2-step strategy becomes an option. First, postinduction MRD is used for primary risk group assignment and treatment stratification. Second, ongoing MRD monitoring serves as a safety net, particularly in patients with MRD-based treatment de-escalation as it allows for preemptive salvage therapy in case of MRD relapse.

Which sensitivity and which time points are required for risk group definition?

Childhood ALL

The first large-scale clinical MRD studies in childhood ALL evaluated the prognostic value of different MRD levels at multiple follow-up time points (Figure 1A).1-3 MRD levels of 10−2, 10−3, and 10−4 and MRD negativity were clearly related to different outcomes at the first follow-up time points. Early MRD negativity predicted good outcome in all studies, whereas remaining high levels of MRD positivity at 3 months (≥10−2 and ≥10−3) predicted poor outcome (Figure 4A).1 Importantly, at later time points (after consolidation, after reinduction, and during first part of maintenance treatment), any MRD positivity was related to poor outcome.

MRD measurements at 1 (day 33) and 3 months (day 78) appeared to provide the most important prognostic information (Figure 4A).1 MRD-based low-risk patients are MRD negative at both time points (defined as no detectable MRD, using methods that reach ≤10−4); MRD-based high-risk patients have high MRD levels (≥5 × 10−4) at the 3-month time point; and MRD-based medium-risk patients have moderate to low MRD levels (<5 × 10−4) at the 3-month time point (Figure 4).1 Please note that the ≥5 × 10−4 cutoff level in RQ-PCR MRD analysis is the same as the original 10−3 cutoff level in the classical dot-blot hybridization technique.1,88

Early MRD measurements at day 15 in childhood ALL can provide additional information for identification of very early responders (<10−3) and a small subgroup of poor responders (≥10−2).23,89,90 However, it should be realized that MRD-based risk group definition at 2 weeks will have a different level of accuracy compared with the day 78 MRD information, when the treatment response to the complete induction block is evaluated.

Adult ALL

In adult ALL, most studies focus on MRD measurement after end of induction and/or during early consolidation, such as in treatment protocols of the GMALL, the French Group For Research On Adult ALL (GRAALL), the Northern Italy Leukemia Group (NILG), and the Programa Espanol de Tratamientos en Hematología (PETHEMA) (Figure 5).6,7,91-94 Within GMALL protocols, MRD negativity (no detectable MRD) after induction-2 and/or consolidation-I (day 71 and week 16) was associated with a comparable clinical benefit irrespective of pretherapeutic risk factors. MRD persistence at a level ≥10−4 after consolidation-I identified patients with molecular failure as a new high-risk group.6,95 Also, the GRAALL, NILG, and PETHEMA confirmed the strong and independent prognostic impact of MRD after induction and early consolidation treatment.7,91-93

Results of prospective clinical trials on adult Ph-ALL according to MRD response. (A) Results of the NILG ALL 09/00 trial (with kind permission by Dr R. Bassan, Bergamo, Italy).91,97 Disease-free survival according to MRD levels at weeks 16 and 22. MRDneg, negative or low MRD positivity (10−4) at week 16 and no detectable MRD at week 22; MRDpos, all other patients with evaluable MRD results; MRDu/k, MRD risk class unknown. (B) Results of the GMALL 06/99 and 07/03 trials (with kind permission by N. Gökbuget, Frankfurt, Germany).6 Probability of continuous complete remission according to MRD at week 16 in SR and HR patients. MolCR, MRD negativity with an assay sensitivity of ≥10−4; MolFail, quantifiable MRD positivity ≥10−4. (C) Results of the PETHEMA ALL-AR-03 trial (with kind permission by J. Ribera, Barcelona, Spain).7 Disease-free survival for HR patients by intention to treat. Assignment to postconsolidation therapy according to early cytomorphologic response and postconsolidation flow-MRD (weeks 16-18): assignment to chemotherapy if <10% blasts in bone marrow (day 14) and flow MRD <5 × 10−4 (weeks 16-18); assignment to allo-HSCT if ≥10% blasts in BM (day 14) and/or flow MRD ≥ 5 × 10−4 (weeks 16-18). (D) Results of the GRAALL-2003/2005 trials (with kind permission by H. Dombret, Paris, France).93 Simon-Makuch plots of SCT time-dependent analysis of RFS according to MRD at week 6 and type of postremission treatment (SCT vs no SCT) in HR Ph-negative ALL.

Results of prospective clinical trials on adult Ph-ALL according to MRD response. (A) Results of the NILG ALL 09/00 trial (with kind permission by Dr R. Bassan, Bergamo, Italy).91,97 Disease-free survival according to MRD levels at weeks 16 and 22. MRDneg, negative or low MRD positivity (10−4) at week 16 and no detectable MRD at week 22; MRDpos, all other patients with evaluable MRD results; MRDu/k, MRD risk class unknown. (B) Results of the GMALL 06/99 and 07/03 trials (with kind permission by N. Gökbuget, Frankfurt, Germany).6 Probability of continuous complete remission according to MRD at week 16 in SR and HR patients. MolCR, MRD negativity with an assay sensitivity of ≥10−4; MolFail, quantifiable MRD positivity ≥10−4. (C) Results of the PETHEMA ALL-AR-03 trial (with kind permission by J. Ribera, Barcelona, Spain).7 Disease-free survival for HR patients by intention to treat. Assignment to postconsolidation therapy according to early cytomorphologic response and postconsolidation flow-MRD (weeks 16-18): assignment to chemotherapy if <10% blasts in bone marrow (day 14) and flow MRD <5 × 10−4 (weeks 16-18); assignment to allo-HSCT if ≥10% blasts in BM (day 14) and/or flow MRD ≥ 5 × 10−4 (weeks 16-18). (D) Results of the GRAALL-2003/2005 trials (with kind permission by H. Dombret, Paris, France).93 Simon-Makuch plots of SCT time-dependent analysis of RFS according to MRD at week 6 and type of postremission treatment (SCT vs no SCT) in HR Ph-negative ALL.

Of note, different adult ALL study groups applied different cutoff values, depending on the MRD time point and the patient population. NILG used week 16 (cutoff of 1 × 10−4) and week 22 (absence of detectable MRD).91 PETHEMA used a cutoff of 5 × 10−4 at weeks 16 to 18.7 GRAALL focused on week 6 with a cutoff of 1 × 10−4 for all Ph-negative ALL92 and 10−3 for high-risk patients,93 respectively. Apart from these differences, all studies confirmed the strong independent prognostic effect of MRD response in adult ALL (Figure 5).6,7,91,93

MRD levels of >10−4 or >5 × 10−4 identify poor MRD responders with a particularly poor prognosis.6,7,91-94,96 These patients are candidates for SCT, which improved prognosis in 3 prospective nonrandomized trials (GMALL, NILG, and GRAALL).6,91-94 NILG correlated postinduction quantitative MRD levels and SCT outcome, showing that MRD from 10−4 to <10−3 correlated with a disease-free survival (DFS) of 60% after SCT, whereas patients with MRD ≥10−3 did very badly.97 In adult ALL patients with MRD levels ≥10−4 after ≥3 intensive treatment blocks, single-drug treatment with the bispecific T-cell engager Blinatumomab, showed encouraging results.75,82,98

MRD good responders have a good prognosis. The PETHEMA trial did not use SCT in Ph-negative high-risk patients with MRD levels <5 × 10−4 at week +17 and good early cytologic response.7 The results suggest that SCT can be avoided in good responders. The GMALL study showed that MRD at very early time points (during induction phase I) identifies a small patient subset with a rapid tumor clearance with MRD levels <10−4 at day 11 and an excellent prognosis.95

How to define MRD negativity?

The definition of MRD negativity has frequently been debated at conferences, mainly in the context of comparing different MRD technologies and related to different definitions of sensitivity.9 Whereas many flow cytometry and PCR-based MRD studies claim a sensitivity of ≤10−4, most classical flow MRD studies reach such sensitivity only in a subset of patients, depending on the aberrant phenotypes and the level of BM regeneration at different time points. This is clearly illustrated by the high numbers of relapses in the MRD-negative low-risk patients in classical flow MRD studies.4,7

MRD negativity implies that no MRD is detected with high certainty, using an MRD technique that can truly measure low MRD levels (quantitative range, ≤10−4). This definition is needed to identify MRD-based low-risk patients with very low chance of relapse (3-5%); otherwise, it might not be possible to consider therapy reduction. In an era of progressive treatment intensification with progressively better outcomes, therapy reduction has been an issue of fierce debate at many childhood oncology meetings. Nevertheless, the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group (DCOG) decided to perform a study with significant treatment reduction in the MRD-based low-risk group, resulting in an excellent outcome with very few side effects (R. Pieters, H. A. de Groot-Kruseman, V. H. J. van der Velden, M. Fiocco, H. van den Berg, E. S. J. M. de Bont, R. M. Egeler, P. M. Hoogerbrugge, G. J. L. Kaspers, C. E. van der Schoot, V. de Haas, J. J. M. van Dongen, unpublished data, 2014). In this DCOG-ALL10 treatment protocol, the sharp criteria of the MRD-based low-risk group of the original I-BFM-SG study have been retained to define MRD negativity, using ≥2 different types of sensitive IG-TR PCR targets, thereby avoiding or reducing oligoclonality problems and related false negativity.1,18,99 This made the MRD-based low-risk group one-third smaller than previously (∼28% instead of ∼43%).

During the last 5 years, the debate about the sensitivity of MRD techniques has intensified. It is clear that MRD technologies should aim for 10−4 to 10−5 to define the MRD-based risk groups accurately. However, discussions about pushing the detection limit further down (even <10−5-10−6) ignore the cellularity limits of BM samples, particularly in aplastic BM.

New high-throughput MRD technologies

Thus far, most European clinical trials use PCR-based MRD techniques, whereas in the United States and several Asian countries, flow MRD approaches are preferred. In the last 5 years, new high-throughput PCR sequencing and flow MRD techniques have been developed, which at least in part use the basic knowledge and experience of the classical MRD techniques. These new approaches aim at higher sensitivities and at easy and broad applicability. Here we briefly provide background information and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of the 2 high-throughput MRD techniques (Table 3).

Characteristics of high-throughput MRD techniques

| MRD technique . | EuroFlow-based flow cytometry (≥8 colors) . | PCR-based HTS of IG-TR genes . |

|---|---|---|

| Targets | N-dimension (eg, principal component analysis)-based deviations from normal leukocytes (normal differentiation/maturation pathways) using novel software (eg, Infinicyt) | Rearranged IG/TR genes |

| Specific onco-genetic aberrations | ||

| Estimated sensitivity | 10−4-10−5(2.5-5.0 × 106 cells analyzed) | 10−4-10−6(depending on amounts of DNA analyzed) |

| Applicability | BCP-ALL: >95% | >95% of all lymphoid malignancies |

| T-ALL: >90% | ||

| Availability | Multiple laboratories in Europe, South America, Asia, South Africa, and Australia (still limited in United States) | Limited no. of labs; mainly centralized in companies |

| Standardization/ assay verification | Full technical EuroFlow standardization and assay verification | No standardization between laboratories |

| No guidelines for data analysis | ||

| QA rounds | Yearly external technical QA (will be increased to several QA rounds per year) | No external QA rounds yet |

| Clinical validation | Ongoing | Ongoing |

| Advantages | Rapid (within 3-4 h) Highly standardized with possibilities for automated gating (Infinicyt software) Efficient data storage and management with easy data comparison Accurate quantitation Provides information on normal and malignant cells Ready for IVD development | High sensitivity Not dependent on primers for patient-specific junctions Potential for IVD development Provides information on background repertoire of B and T cells Potential to identify oligoclonality and clonal evolution phenomena |

| Disadvantages | Education and training required Many cells needed to reach the required sensitivity, eg, 5.0 × 106, if quantitation down to 10−5 is needed | Super-multiplex PCR, prone to disproportional target amplification Discrimination from normal clonal background Complex bioinformatic pipeline + need for error correction Turnaround time of ∼1 week per sample Prone to contamination problems (if no barcoded primers are used) No clear definition for positivity Limited experience in the field |

| MRD technique . | EuroFlow-based flow cytometry (≥8 colors) . | PCR-based HTS of IG-TR genes . |

|---|---|---|

| Targets | N-dimension (eg, principal component analysis)-based deviations from normal leukocytes (normal differentiation/maturation pathways) using novel software (eg, Infinicyt) | Rearranged IG/TR genes |

| Specific onco-genetic aberrations | ||

| Estimated sensitivity | 10−4-10−5(2.5-5.0 × 106 cells analyzed) | 10−4-10−6(depending on amounts of DNA analyzed) |

| Applicability | BCP-ALL: >95% | >95% of all lymphoid malignancies |

| T-ALL: >90% | ||

| Availability | Multiple laboratories in Europe, South America, Asia, South Africa, and Australia (still limited in United States) | Limited no. of labs; mainly centralized in companies |

| Standardization/ assay verification | Full technical EuroFlow standardization and assay verification | No standardization between laboratories |

| No guidelines for data analysis | ||

| QA rounds | Yearly external technical QA (will be increased to several QA rounds per year) | No external QA rounds yet |

| Clinical validation | Ongoing | Ongoing |

| Advantages | Rapid (within 3-4 h) Highly standardized with possibilities for automated gating (Infinicyt software) Efficient data storage and management with easy data comparison Accurate quantitation Provides information on normal and malignant cells Ready for IVD development | High sensitivity Not dependent on primers for patient-specific junctions Potential for IVD development Provides information on background repertoire of B and T cells Potential to identify oligoclonality and clonal evolution phenomena |

| Disadvantages | Education and training required Many cells needed to reach the required sensitivity, eg, 5.0 × 106, if quantitation down to 10−5 is needed | Super-multiplex PCR, prone to disproportional target amplification Discrimination from normal clonal background Complex bioinformatic pipeline + need for error correction Turnaround time of ∼1 week per sample Prone to contamination problems (if no barcoded primers are used) No clear definition for positivity Limited experience in the field |

EuroFlow-based (≥8-color) next-generation flow MRD

The EuroFlow consortium has introduced new high-throughput concepts in flow MRD, based on multivariate analysis, eg, principal component and canonical analysis.100,101 Another important feature is the development of MRD antibody combinations that give insight in the full normal BCP pathway in BM, which allows to define the degree of immunophenotypic deviation of BCP-ALL cells from normal BCP (also in regenerating BM), visualized in multivariate analysis plots (Figure 6).100,101 This development required >5 rounds of design, testing, evaluation, and redesign (with 50-100 BCP-ALL cases per testing round) to define reliable combinations of fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies. Also flow MRD in T-ALL requires discrimination from various types of normal T cells and other cells with cross-lineage marker expression. Consequently, also for T-ALL, a comparable strategy is used to obtain reliable (evidence-based) antibody combinations.

EuroFlow-based multidimensional analysis of normal and malignant BCP cells. (A) (Left) Automated population separation of normal B-cell differentiation in BM (BCP cells and more mature B cells). (Center) Automated population separation view of BCP cells in regenerating BM (blue dots), plotted against the normal B-cell differentiation (green arrow), showing that regenerating BCP cells (hematogones) are fully comparable to BCP cells in normal BM. (Right) Plotting of ALL cells (red dots) against normal B-cell differentiation (green), showing that the ALL cells differ from normal B cells. (B) (Left) ALL cells (in red) plotted against normal BCP cells (green). (Center) ALL cells (red) plotted against immature CD34+ BCP cells only, showing that the ALL cells separate from their normal counterparts. (Right) The separation is not based on a single marker but on multiple markers (in this case: CD10, FSC, CD38, etc). (C) Normalized B-cell maturation pathway (gray zone), allowing to assess differences in CD38 expression between ALL cells and normal cells to support MRD detection. (Left) MRD analysis in BM at day 33, showing complete deletion of the normal BCP cells, but presence of normal more mature B cells (green) within the normal B-cell pathway, as well as a small population of ALL cells with aberrant (low) CD38 expression. (Right) MRD analysis of BM at day 78 of the same patient as in the left panel, now showing regeneration of normal BCP cells (blue dots), which fit with the normalized B-cell differentiation pathway (gray zone). No aberrant cells were detected at day 78 in this patient sample.

EuroFlow-based multidimensional analysis of normal and malignant BCP cells. (A) (Left) Automated population separation of normal B-cell differentiation in BM (BCP cells and more mature B cells). (Center) Automated population separation view of BCP cells in regenerating BM (blue dots), plotted against the normal B-cell differentiation (green arrow), showing that regenerating BCP cells (hematogones) are fully comparable to BCP cells in normal BM. (Right) Plotting of ALL cells (red dots) against normal B-cell differentiation (green), showing that the ALL cells differ from normal B cells. (B) (Left) ALL cells (in red) plotted against normal BCP cells (green). (Center) ALL cells (red) plotted against immature CD34+ BCP cells only, showing that the ALL cells separate from their normal counterparts. (Right) The separation is not based on a single marker but on multiple markers (in this case: CD10, FSC, CD38, etc). (C) Normalized B-cell maturation pathway (gray zone), allowing to assess differences in CD38 expression between ALL cells and normal cells to support MRD detection. (Left) MRD analysis in BM at day 33, showing complete deletion of the normal BCP cells, but presence of normal more mature B cells (green) within the normal B-cell pathway, as well as a small population of ALL cells with aberrant (low) CD38 expression. (Right) MRD analysis of BM at day 78 of the same patient as in the left panel, now showing regeneration of normal BCP cells (blue dots), which fit with the normalized B-cell differentiation pathway (gray zone). No aberrant cells were detected at day 78 in this patient sample.

To reach high sensitivity, new cell sample processing was introduced, aiming at analysis of ≥5 × 106 cells to have a population of ≥40 cells at quantifiable MRD levels of 10−5. The EuroFlow tools and strategies indeed reach sensitivities <10−4 to 10−5 (-10−6). This requires fully standardized approaches, including instrument setting, sample processing with bulk lysis procedure, immunostaining, data acquisition, and data analysis with standardized (even automated) gating strategies for definition of cell populations102,103 ; see www.EuroFlow.org for standard operating procedures (Table 3). The EuroFlow QA program helps to identify technical failures or inconsistencies and will be available for all EuroFlow users per 2015.104

Importantly, EuroFlow-based next-generation flow (NGF)-MRD strategies provide full insight into the composition of normal cells and aberrant cells, such as treatment-induced immunophenotypic shifts within the ALL cell population,105,106 including lineage shifts in ∼5% of pediatric cases, such as CD2+ BCP-ALL cases with an early switch to the monocytic lineage107,108 ; heterogeneity in the blast cell population with dedifferentiation to immature stem-like cells; and aberrancies in other lineages, pointing to the possibility that more lineages are affected by the disease process or by toxicity of the treatment.

Finally, within the last decade, most diagnostic laboratories shifted rapidly from 3- and 4-color flowcytometers to 8- and 10-color flowcytometers. With the introduction of new fluorochromes and 4- to 6-laser flowcytometers, >15 colors should be possible for routine settings in the forthcoming decade, which likely will contribute to improved applicability and improved specificity of flow MRD measurements.

High-throughput sequencing of IG-TCR targets (DNA level)

PCR-based high-throughput sequencing (HTS) of IG-TR gene rearrangements to quantify MRD in lymphoid malignancies is currently the focus of intense research. For this purpose, multiplex PCR V-, D-, and J-primer sets42,109-111 are being used to amplify all potential rearrangements in a sample and to consecutively sequence them with high depth of >1 × 106. Comparable to RQ-PCR approaches, the first step is identification of clone-specific IG-TR index sequences using the diagnostic sample (Table 3). However, in contrast to RQ-PCR, the laborious design and testing of patient-specific assays is avoided as the same multiplex approach is applied to follow-up samples, with re-identification of the index sequence(s), allowing for MRD quantification. Moreover, the readout is more specific than RQ-PCR, where false-positive results may be caused by nonspecific binding of the ASO primer, particularly in situations with massive BCP regeneration.112,113 HTS IG-TR can also detect clonal evolution of IG-TR rearrangements114 and provide insight into the background repertoire of B and T cells. Overall, HTS can speed up the process of molecular MRD quantification and provide results at early time points of the treatment, which has not been possible before because of the time-consuming ASO-RQ-PCR preparations.

One of the main concerns in HTS for MRD assessment is the correct identification of the IG-TR gene rearrangements of the ALL cells (Table 3). Published studies use an arbitrary cutoff of 5% of all sequences.110,115,116 This procedure is error prone, because (depending on the clinical setting) IG-TR rearrangements of unrelated B- and T-cell clones can account for a considerable fraction of amplified sequences and might be misinterpreted as “leukemia-specific” rearrangements, particularly when the applied primer set does not detect the IG-TR rearrangements of the ALL cells; in such situations, only IG-TR rearrangements of the remaining lymphoid cells will be detected by HTS. Also the assumption of absolute specificity of the ALL sequence has to be revisited, because (depending on the rearrangement) background frequencies might occur, limiting the sensitivity of HTS.117 Another issue, rarely discussed, is the fact that most PCR-HTS approaches use a 2-step procedure with the necessity of post-PCR processing with nonbarcoded PCR amplicons, which is prone to contamination and, in this respect a step backward, comparable to nested PCR methods of previous times. This is why several groups are now redesigning primers directly linked to sample-specific barcodes in a 1-step procedure (Figure 7).

Schematic diagram showing the various steps in HTS of IG and TR for MRD detection. (Top) The IG or TR gene rearrangements are amplified in a single step using a super-multiplex PCR with many different primers, which match with one or more individual V and J genes of the IG and TR genes. The primers contain a platform-specific adaptor (red) and a unique identifier (barcode) for each sample (green). (Middle) After PCR amplification, HTS is being performed, using sequence primers directed against the platform-specific adaptors. (Bottom) The obtained sequencing data are processed via a specially designed bioinformatic pipeline, which includes error correction, annotation of the gene segments, meta-analysis, and visualization of the results (www.EuroClonality.org).

Schematic diagram showing the various steps in HTS of IG and TR for MRD detection. (Top) The IG or TR gene rearrangements are amplified in a single step using a super-multiplex PCR with many different primers, which match with one or more individual V and J genes of the IG and TR genes. The primers contain a platform-specific adaptor (red) and a unique identifier (barcode) for each sample (green). (Middle) After PCR amplification, HTS is being performed, using sequence primers directed against the platform-specific adaptors. (Bottom) The obtained sequencing data are processed via a specially designed bioinformatic pipeline, which includes error correction, annotation of the gene segments, meta-analysis, and visualization of the results (www.EuroClonality.org).

Like all other MRD methods, the sensitivity of HTS is dependent on the number of analyzed cells and the corresponding amount of DNA. Therefore, a sensitivity of 10−6 cannot be reached if only 2 to 4 μg of DNA is used. Furthermore, DNA is extracted from all cells in the sample, implying that the target cell DNA is mixed with that of normal counterparts and many other cells. As a consequence, only a small fraction of the DNA is amplified, eg, only the IG rearrangements of 50 000 B cells of a total of 106 BM leukocytes.

Overall, standardization, quality control, and validation of HTS in a multicenter and scientifically independent setting is highly warranted but still lacking (Table 3). Therefore, the scientific consortia EuroClonality (www.EuroClonality.org) and EuroMRD are now collaborating to standardize the HTS methods before implementation in routine practice (Figure 7). This includes the preanalytical, analytical (eg, new primers with sample-specific barcodes), and postanalytical phases (eg, a novel bioinformatics pipeline), as well as the generation of large databases to determine background in different clinical settings, and validation of the technology via large-scale multilaboratory testing of clinical samples in the context of clinical trials.

Conclusion

In the ALL field, MRD diagnostics is no longer a (clinical) research tool for evaluation of clinical trials only but has become part of diagnostic patient care. Consequently, standardized MRD diagnostics should be available for assessment of treatment response in each individual ALL patient, to be used for personalized medicine such as accurate risk group assignment with risk-adapted treatment. This also includes the evaluation of new treatment modalities, where MRD measurements can demonstrate the effectiveness of the novel treatment and be used as a surrogate end point.

Most classical MRD techniques are not sufficiently standardized or contain patient-specific elements that make in vitro diagnostics (IVD) approval complex. The 2 new high-throughput MRD technologies can solve these problems, but they have to fulfill a series of requirements for acceptance in the field, such as broad availability, easy implementation, applicability in the vast majority of patients (90-95%), sufficient sensitivity (quantitative range of ≤10−4, preferably down to 10−5), fast (short turn-around time, particularly for follow-up samples), affordable, and standardized with QA programs. This requires international (worldwide) collaboration with interactive workshops and educational meetings for exchange of technologies and tools, as well as agreements on the definition of MRD cutoff levels for risk group assignment. In the next 3 to 5 years, it will become clear whether HTS-MRD and NGF-MRD can meet the needs of the field.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their colleagues from the EuroClonality, EuroMRD, and EuroFlow consortia for their fruitful collaboration and collective actions to innovate, standardize, and disseminate the collective achievements in the field of MRD diagnostics. These achievements form the basis for this review. Marieke Bitter is thanked for the design of the figures, Quentin Lecrevisse for providing Figure 6, and Bibi van Bodegom for her secretarial support.

Authorship

Contribution: J.J.M.v.D., V.H.J.v.d.V., M.B., and A.O. contributed to the writing of the invited review and to the design of the figures and the tables.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors are members of EuroMRD (J.J.M.v.D., V.H.J.v.d.V., and M.B.), EuroFlow (J.J.M.v.D., A.O., and V.H.J.v.d.V.), and EuroClonality (J.J.M.v.D. and M.B.). These consortia are scientifically independent organizations, which collectively own intellectual property (IP), including patents. Revenues from licensed IP and patents are collectively owned by the 3 above mentioned consortia and are fully used for sustainability of these consortia, such as for covering costs for scientific meetings, reagents, and management support, as well as for educational materials, which are distributed on request free of charge. BD Biosciences provides support for part of the external EuroFlow educational meetings and workshops, including part of the traveling costs for J.J.M.v.D. and A.O..

Correspondence: J.J.M. van Dongen, Department of Immunology, Room Na-1208, Erasmus University Medical Center, Wytemaweg 80, 3015 CN, Rotterdam, The Netherlands; e-mail: j.j.m.vandongen@erasmusmc.nl.