Key Points

For women with preeclampsia, BMI >30 kg/m2, infection, or those having cesarean delivery, VTE risk remained elevated for 6 weeks postpartum.

For women with postpartum hemorrhage or preterm birth, the relative rate of VTE was only increased for the first 3 weeks postpartum.

Abstract

Impact on the timing of first postpartum venous thromboembolism (VTE) for women with specific risk factors is of crucial importance when planning the duration of thromboprophylaxis regimen. We observed this using a large linked primary and secondary care database containing 222 334 pregnancies resulting in live and stillbirth births between 1997 and 2010. We assessed the impact of risk factors on the timing of postpartum VTE in term of absolute rates (ARs) and incidence rate ratios (IRRs) using a Poisson regression model. Women with preeclampsia/eclampsia and postpartum acute systemic infection had the highest risk of VTE during the first 3 weeks postpartum (ARs ≥2263/100 000 person-years; IRR ≥2.5) and at 4-6 weeks postpartum (AR ≥1360; IRR ≥3.5). Women with body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m2 or those having cesarean delivery also had elevated rates up to 6 weeks (AR ≥1425 at 1-3 weeks and ≥722 at 4-6 weeks). Women with postpartum hemorrhage or preterm birth, had significantly increased VTE rates only in the first 3 weeks (AR ≥1736; IRR ≥2). Our findings suggest that the duration of the increased VTE risk after childbirth varies based on the type of risk factors and can extend up to the first 3 to 6 weeks postpartum.

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a preventable serious maternal complication1,2 most likely to occur during the postpartum period.3-5 Although a number of studies6-9 have identified risk factors for VTE during the postpartum period, there is a lack of evidence quantifying how the impact of risk factors on the incidence of VTE may differ from early to later postpartum periods. The United Kingdom Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG)10 and the American College of Chest Physicians11 guidelines currently recommend 7 days or in-hospital pharmacologic postpartum thromboprophylaxis, respectively, for women with ≥2 minor risk factors (eg, smoking, postpartum hemorrhage, preeclampsia, cesarean delivery, obesity) if they have had no previous VTE. These guidelines, however, are based on expert clinical consensus rather than on robust evidence. Such evidence for the impact on the timing of postpartum VTE for women with specific risk factors is of crucial importance when planning the duration of thromboprophylaxis regimens.12 Although a large study by Kamel et al13 recently looked at the risk of VTE during specific postpartum periods, they were unable stratify the effects of risk factors in the different periods.

Previously, our group comprehensively reported the risk factors of VTE during the postpartum period in terms of absolute risks.14 However, due to the uncertainty of timing of VTE recorded in primary care data, we were then unable to assess the risk of VTE during specific postpartum periods by risk factors. Similarly, previous studies have also failed to report those estimates. Recently linked primary and secondary care data that are representative of the English population provide better information on the timing of VTE than solely using primary care data particularly during the specific postpartum periods.15 Therefore, our aim was to assess the risk of VTE during specific postpartum periods according to women’s risk profiles using these prospectively collected primary and secondary care data. We employed multiple modeling frameworks based on a conceptual hierarchical framework to quantify the impacts of women’s preexisting, pregnancy, and delivery-related risk factors and to assess the effects of mutual confounding and mediation by certain risk factors.

Methods

Study population

We used the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD),16 which is a large longitudinal United Kingdom (UK) database that contains computerized primary care (ie, general practice) records of anonymized patients. Approximately 98% of the England and Wales population is registered with general practitioners (GPs), who areresponsible for almost the entirety of a patient’s medical care, including coordination of their health care from hospital or other secondary care facilities. The CPRD includes practices that have received training to record information using the Vision software and that have consented to be included in the database. All patients within a consented practice are automatically included. Around 53% of CPRD practices are linked to Hospital Episode Statistics (HES)17 data, which contain information on all hospitalizations in England including all discharge diagnoses and procedures. The anonymized patient identifiers from CPRD and HES were linked by a trusted third party using National Health Service number, date of birth, postcode, and gender.18 As HES only covers English hospitals, practices from Northern Ireland, Wales, and Scotland were excluded. Previously, data from the linked portion of the CPRD have been shown to be representative in terms of age and sex distribution to data from the UK population published by the Office for National Statistics. Diagnoses of VTE in primary care19 and birth information in HES maternity data20 have been validated to external sources with accuracy, with positive predictive values of 84% and 90%, respectively. Women aged 15 to 44 years with HES-recorded pregnancies ending in live birth or stillbirth between 1997 and 2010 and with no VTE before or during pregnancy (as determined from their longitudinal clinical record) were identified as our study population.

We defined first VTE using Read and ICD-10 diagnosis codes for pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis in CPRD and HES, respectively (taking the earliest date as the date of diagnosis if the event was recorded in both databases). For VTE events first recorded in HES, the date of VTE was taken as the date of hospital admission. The diagnosis was accepted if supported by one of the following: a prescription of heparin or warfarin within 90 days of diagnosis, evidence of anticoagulant therapy or attendance at an anticoagulant clinic within 90 days of diagnosis, or death within 30 days of diagnosis. Rates of VTE ascertained using this definition have been demonstrated to be highly comparable to incidence rates of VTE in and around pregnancy across other high-income countries, and estimation of the date of clinical diagnosis of VTE during specific postpartum periods has been found to be accurate.15 As 90% of deliveries occurred on the day women were admitted to hospital for delivery or on the day after, the postpartum period was defined from 1 day before delivery to 12 weeks after, to ensure VTE events occurring during delivery admissions were captured.

Defining potential risk factors

Demographics, lifestyle characteristics, and preexisting comorbidities.

For all pregnancies, we extracted information on women’s demographic and lifestyle characteristics as well as important comorbidities from both primary and secondary care data. Information on body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2), cigarette smoking (current, ex-smoker, or nonsmoker), ethnicity (white or nonwhite), and age at delivery were obtained from CPRD data, whereas cardiac disease, varicose veins, inflammatory bowel disease, preexisting diabetes, and hypertension were ascertained using both CPRD and HES using methods similar to previously described using primary care data.14 Similarly, we defined women as having preexisting renal disease if they had a diagnosis of acute or chronic kidney disease, glomerular or renal tubule-interstitial disease before conception in HES or CPRD.

Pregnancy characteristics and complications.

Preeclampsia/eclampsia, hyperemesis, multiple birth, gestational diabetes, or hypertension as previously defined14 were extracted using both CPRD and HES.

Delivery characteristics and complications.

From HES, we extracted risk factors occurring around delivery: length of gestation categorized as preterm, normal, or prolonged (<37, 37-41, and ≥42 weeks, respectively), mode of delivery (spontaneous, assisted [forceps, breech, or vacuum], or emergency or elective cesarean), stillbirth, and postpartum hemorrhage (including intrapartum hemorrhage). We also assessed the 2 most common acute systemic infections known to be associated with increased risk of VTE (urinary and respiratory tract infection).21,22

Statistical analysis

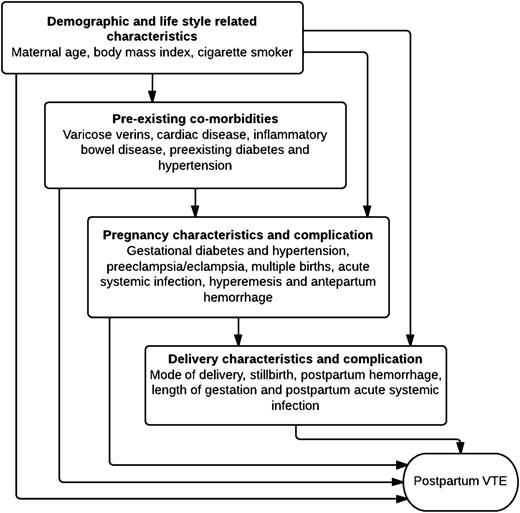

We calculated incidence rates of VTE per 100 000 person-years and incidence rate ratios (IRRs) using Poisson regression for potential risk factors. We fitted a clustering term to take into account multiple pregnancies experienced by an individual woman over the study period. For associations where the likelihood ratio test (LRT) P value was <.1, we included these risk factors in multivariate models. Our multivariate analyses were constructed using a predeveloped conceptual hierarchical framework (Figure 1) as a tool to assess the complex causal pathways between variables.23 For instance, some of the impact of delivery complications (eg, mode of delivery, postpartum hemorrhage) on postpartum VTE may be confounded by pregnancy characteristics (eg, preeclampsia), preexisting medical comorbidities (eg, cardiac disease), or demographic factors (eg, maternal age); however, each of these factors may also have direct effects on postpartum VTE that are not mediated through delivery complications.

Conceptual hierarchical framework for multivariate modeling of risk factors for VTE during the postpartum period.

Conceptual hierarchical framework for multivariate modeling of risk factors for VTE during the postpartum period.

In our hierarchical framework, we grouped factors that were considered to have more proximate associations with postpartum VTE (eg, cesarean delivery) separately from more distant factors (eg, prepregnancy BMI) that may have direct effects on VTE but may also have indirect effects mediated through proximate risk factors. Based on this, we created 3 modeling frameworks (MFs) to present rate ratio estimates adjusted for different groups of risk factors. In MF 1, we created separate models for each preexisting comorbidity, pregnancy, and delivery characteristic/complication to estimate their overall effects on postpartum VTE, adjusting only for demographic and lifestyle characteristics (maternal age, BMI, cigarette smoker). In MF 2, models from MF 1 were additionally adjusted for any preexisting medical comorbidities (eg, cardiac disease). In MF 3, models were adjusted for demographic and lifestyle-related factors, preexisting medical comorbidities, and pregnancy-related characteristics and complications to estimate each of their effects unmediated by their more proximate risk factors and also the fully adjusted effects of each delivery characteristic/complication. At that point, we readded statistically nonsignificant variables previously excluded to assess if they became significant. Because the direction of causal pathways between cesarean delivery and other delivery complications (eg, stillbirth) can vary, we carried out a subgroup analysis restricting to women who only underwent spontaneous vaginal or assisted delivery. We also formally tested for interaction between risk factors based on biological plausibility using the LRT (P < .05).

For pregnancy and delivery complications showing increased postpartum VTE risks with >10 associated VTE events (to ensure reasonable precision), we assessed whether the absolute and relative risks (ARs and RRs) of VTE differed during the early postpartum (weeks 1-3 and weeks 4-6 postdelivery) and late postpartum (weeks 7-12 postdelivery). For the purpose of this analysis, we also evaluated the risk of VTE within 1 year after the 12-week postpartum period (weeks 13-52 postdelivery). Although the rate of VTE expressed as per 100 000 person-years during postpartum periods helps in standardization and comparison of estimates, we also calculated the rate of VTE per 100 000 pregnancies, which is of clinical value. We used those estimates to calculate the number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent 1 VTE assuming that thromboprophylaxis reduces the VTE risk by 50% based on the randomized trials of general medical patients.24 We also calculated the NNT based on the 88% risk reduction observed among nonrandomized pregnant women.25

For our sensitivity analysis, we reran all models, excluding the small proportion (7%) of VTE events first recorded in HES because they occurred during the same hospital admission as the delivery or another risk factor event (eg, postpartum hemorrhage) and therefore precise temporality could not be established (ie, we could not determine whether VTE was the cause or consequence of a cesarean delivery or postpartum hemorrhage, particularly for those occurring on the same day). This study was approved by the Independent Scientific Advisory Committee reference number 10_193R.

Results

Among 168 077 women, there were 222 334 pregnancies ending in live birth or stillbirth. There were a total of 178 VTE events that occurred during the postpartum period. Table 1 shows absolute rates of postpartum VTE and associations with each of the 21 risk factors assessed, 14 of which were significantly associated with postpartum VTE in bivariate models (LRT, P < .01).

Incidence rates of postpartum VTE per 100 000 person-years and IRRs for potential delivery, pregnancy, and preexisting risk factors (222 334 pregnancies)

| Variable . | Pregnancies, n (%) (total = 222 334) . | Postpartum VTE, n (total = 178) . | Rate (95% CI)* . | IRR (95% CI) unadjusted . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and lifestyle characteristics | ||||

| Maternal age at delivery | ||||

| 15-19 y | 12 927 (5.8) | 5 | 170 (70-408) | 0.43 (0.17-1.08) |

| 20-24 y | 36 960 (16.6) | 28 | 330 (228-478) | 0.84 (0.53-1.33) |

| 25-29 y | 58 207 (26.1) | 53 | 390 (298-551) | 1.00 |

| 30-34 y | 68 753 (30.9) | 37 | 228 (165-315) | 0.58 (0.38-8.90) |

| 35-39 y | 37 968 (17.0) | 44 | 491 (366-661) | 1.25 (0.84-1.87) |

| 40-44 y | 7 519 (3.3) | 11 | 325 (346-1 130) | 1.60 (0.83-3.06) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| Normal (18.5-24.9) | 98 730 (44.4) | 60 | 259 (201-334) | 1.00 |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 7 339 (3.30) | 3 | 179 (56-545) | 0.67 (0.21-2.16) |

| Overweight (25-29.9) | 39 652 (17.8) | 33 | 353 (252-499) | 1.36 (0.89-2.09) |

| Obese (30-40) | 21 410 (9.6) | 28 | 558 (385-808) | 2.14 (1.37-3.36) |

| Class 3 obese (>40) | 2 731 (1.2) | 12 | 1 881 (1 068-3 312) | 7.24 (3.89-13.4) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 159 159 (71.5) | 129 | 347 (292-412) | 1.00 |

| Non white | 21 178 (9.5) | 21 | 430 (280-658) | 1.23 (0.78-1.96) |

| Missing | 41 997 (18.8) | 28 | 284 (196-411) | 0.81 (0.54-1.23) |

| Cigarette smoker | 51 731 (23.2) | 51 | 424 (322-558) | 1.24 (0.88-1.76) |

| Ex-smoker | 55 743 (25) | 36 | 275 (198-382) | 0.81 (0.55-1.19) |

| Preexisting comorbidities | ||||

| Varicose veins | 5 895 (2.65) | 16 | 1 154 (707-1884) | 3.59 (2.15-6.01) |

| Cardiac disease | 2 264 (1.0) | 5 | 945 (393-2271) | 2.80 (1.15-6.83) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 1 105 (0.5) | 4 | 1 545 (580-4 117) | 4.58 (1.69-12.3) |

| Preexisting hypertension | 13 814 (6.5) | 17 | 524 (326-844) | 1.68 (1.01-2.78) |

| Preexisting diabetes | 2 501 (1.1) | 4 | 685 (257-1 826) | 2.03 (0.75-5.46) |

| Preexisting renal disease | 1 493 (0.7) | 2 | 575 (143-2 300) | 1.68 (0.41-6.78) |

| Pregnancy characteristics and complications | ||||

| Antepartum hemorrhage | 10 329 (4.6) | 10 | 416 (224-774) | 1.22 (0.64-2.31) |

| Acute systemic infection | 26 572 (11.9) | 20 | 323 (208-550) | 0.93 (0.58-1.48) |

| Preeclampsia/eclampsia | 5 237 (2.3) | 14 | 1 148 (679-1938) | 3.54 (2.05-6.11) |

| Multiple birth | 3 282 (1.4) | 3 | 390 (125-1 211) | 1.14 (0.36-3.57) |

| Gestational hypertension | 11 796 (5.6) | 18 | 655 (413-1041) | 2.10 (1.28-3.43) |

| Gestational diabetes | 3 518 (1.6) | 4 | 486 (182-1294) | 1.44 (0.53-3.88) |

| Hyperemesis | 7 838 (3.53) | 9 | 494 (257-950) | 1.46 (0.74-2.86) |

| Delivery characteristics and complications | ||||

| Length of gestation | ||||

| Normal gestation | 184 744 (83.0) | 15 | 313 (264-370) | 1.00 |

| Preterm gestation | 17 112 (7.7) | 29 | 727 (505-1 047) | 2.31 (1.55-3.46) |

| Prolonged gestation | 20 478 (9.2) | 14 | 293 (173-494) | 0.93 (0.53-1.62) |

| Mode of delivery | ||||

| Spontaneous | 141 1207 (63.5) | 76 | 230 (184-288) | 1.00 |

| Assisted | 26 943 (12.1) | 19 | 304 (194-476) | 1.31 (0.79-2.18) |

| Elective cesarean | 22 341 (10.0) | 33 | 630 (448-886) | 2.73 (1.81-4.11) |

| Emergency cesarean | 31 843 (14.3) | 50 | 674 (511-890) | 2.92 (2.04-4.18) |

| Stillbirth | 1 356 (0.61) | 8 | 2 595 (1 297-5 189) | 7.86 (3.87-15.9) |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | 20 762 (9.34) | 30 | 629 (440-900) | 2.00 (1.35-2.96) |

| Postpartum acute systemic infection | 7 740 (3.4) | 18 | 1 291 (813-2049) | 4.07 (2.50-6.63) |

| Variable . | Pregnancies, n (%) (total = 222 334) . | Postpartum VTE, n (total = 178) . | Rate (95% CI)* . | IRR (95% CI) unadjusted . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and lifestyle characteristics | ||||

| Maternal age at delivery | ||||

| 15-19 y | 12 927 (5.8) | 5 | 170 (70-408) | 0.43 (0.17-1.08) |

| 20-24 y | 36 960 (16.6) | 28 | 330 (228-478) | 0.84 (0.53-1.33) |

| 25-29 y | 58 207 (26.1) | 53 | 390 (298-551) | 1.00 |

| 30-34 y | 68 753 (30.9) | 37 | 228 (165-315) | 0.58 (0.38-8.90) |

| 35-39 y | 37 968 (17.0) | 44 | 491 (366-661) | 1.25 (0.84-1.87) |

| 40-44 y | 7 519 (3.3) | 11 | 325 (346-1 130) | 1.60 (0.83-3.06) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| Normal (18.5-24.9) | 98 730 (44.4) | 60 | 259 (201-334) | 1.00 |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 7 339 (3.30) | 3 | 179 (56-545) | 0.67 (0.21-2.16) |

| Overweight (25-29.9) | 39 652 (17.8) | 33 | 353 (252-499) | 1.36 (0.89-2.09) |

| Obese (30-40) | 21 410 (9.6) | 28 | 558 (385-808) | 2.14 (1.37-3.36) |

| Class 3 obese (>40) | 2 731 (1.2) | 12 | 1 881 (1 068-3 312) | 7.24 (3.89-13.4) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 159 159 (71.5) | 129 | 347 (292-412) | 1.00 |

| Non white | 21 178 (9.5) | 21 | 430 (280-658) | 1.23 (0.78-1.96) |

| Missing | 41 997 (18.8) | 28 | 284 (196-411) | 0.81 (0.54-1.23) |

| Cigarette smoker | 51 731 (23.2) | 51 | 424 (322-558) | 1.24 (0.88-1.76) |

| Ex-smoker | 55 743 (25) | 36 | 275 (198-382) | 0.81 (0.55-1.19) |

| Preexisting comorbidities | ||||

| Varicose veins | 5 895 (2.65) | 16 | 1 154 (707-1884) | 3.59 (2.15-6.01) |

| Cardiac disease | 2 264 (1.0) | 5 | 945 (393-2271) | 2.80 (1.15-6.83) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 1 105 (0.5) | 4 | 1 545 (580-4 117) | 4.58 (1.69-12.3) |

| Preexisting hypertension | 13 814 (6.5) | 17 | 524 (326-844) | 1.68 (1.01-2.78) |

| Preexisting diabetes | 2 501 (1.1) | 4 | 685 (257-1 826) | 2.03 (0.75-5.46) |

| Preexisting renal disease | 1 493 (0.7) | 2 | 575 (143-2 300) | 1.68 (0.41-6.78) |

| Pregnancy characteristics and complications | ||||

| Antepartum hemorrhage | 10 329 (4.6) | 10 | 416 (224-774) | 1.22 (0.64-2.31) |

| Acute systemic infection | 26 572 (11.9) | 20 | 323 (208-550) | 0.93 (0.58-1.48) |

| Preeclampsia/eclampsia | 5 237 (2.3) | 14 | 1 148 (679-1938) | 3.54 (2.05-6.11) |

| Multiple birth | 3 282 (1.4) | 3 | 390 (125-1 211) | 1.14 (0.36-3.57) |

| Gestational hypertension | 11 796 (5.6) | 18 | 655 (413-1041) | 2.10 (1.28-3.43) |

| Gestational diabetes | 3 518 (1.6) | 4 | 486 (182-1294) | 1.44 (0.53-3.88) |

| Hyperemesis | 7 838 (3.53) | 9 | 494 (257-950) | 1.46 (0.74-2.86) |

| Delivery characteristics and complications | ||||

| Length of gestation | ||||

| Normal gestation | 184 744 (83.0) | 15 | 313 (264-370) | 1.00 |

| Preterm gestation | 17 112 (7.7) | 29 | 727 (505-1 047) | 2.31 (1.55-3.46) |

| Prolonged gestation | 20 478 (9.2) | 14 | 293 (173-494) | 0.93 (0.53-1.62) |

| Mode of delivery | ||||

| Spontaneous | 141 1207 (63.5) | 76 | 230 (184-288) | 1.00 |

| Assisted | 26 943 (12.1) | 19 | 304 (194-476) | 1.31 (0.79-2.18) |

| Elective cesarean | 22 341 (10.0) | 33 | 630 (448-886) | 2.73 (1.81-4.11) |

| Emergency cesarean | 31 843 (14.3) | 50 | 674 (511-890) | 2.92 (2.04-4.18) |

| Stillbirth | 1 356 (0.61) | 8 | 2 595 (1 297-5 189) | 7.86 (3.87-15.9) |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | 20 762 (9.34) | 30 | 629 (440-900) | 2.00 (1.35-2.96) |

| Postpartum acute systemic infection | 7 740 (3.4) | 18 | 1 291 (813-2049) | 4.07 (2.50-6.63) |

Rate calculated per 100 000 person-years.

Multivariate analyses of postpartum VTE risks

When we assessed the direct and mediated effects of each factor using different modeling frameworks (Figure 1 and Table 2), we found that high BMI was associated with increased postpartum VTE risk across all 3 models, indicating that little of the obesity-associated risk was mediated through other factors, preexisting or pregnancy related. Similarly there were almost fourfold and threefold increased risks for women previously diagnosed with varicose veins and cardiac disease, respectively, which did not appear to be strongly mediated by other risk factors. For delivery characteristics and complications, we found a 7-fold (95% confidence interval [CI], 3.33-15.4) increased risk of VTE for those with stillbirth even after adjusting for important background factors. Elective cesarean and emergency cesarean, infection, and preterm birth were associated with at least twofold increased risks compared with spontaneous vaginal deliveries, those with no postpartum acute systemic infection, and those with normal gestational length, respectively. These factors were still important even after adjusting for women’s preexisting comorbidities and factors occurring prior to delivery. Furthermore, we found no evidence of an interaction between preterm birth and preeclampsia/eclampsia (P = .22) or stillbirth (P = .46). The increased risk of VTE observed with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 and cesarean delivery remained consistent when we restricted our analysis to women without any other risk factor (Table 3).

Multivariate analysis for VTE risk factors during the postpartum period

| Variable . | IRR (95% CI) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MF 1 . | MF 2 . | MF 3 . | MF 3 restricted to spontaneous vaginal/assisted deliveries . | |

| Demographic and lifestyle characteristics | ||||

| Maternal age at delivery | ||||

| Age (for every year increase)* | 1.03 (1.00-1.06) | 1.02 (0.99-1.05) | 1.02 (0.99-1.05) | 1.02 (0.98-1.07) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| Normal (18.5-24.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 0.70 (0.21-2.27) | 0.69 (0.21-2.23) | 0.74 (0.23-2.39) | 0.84 (0.19-3.56) |

| Overweight (25-29.9) | 1.35 (0.88-2.07) | 1.36 (0.89-2.09) | 1.21 (0.77-1.90) | 0.67 (0.30-1.46) |

| Obese (30-40) | 2.13 (1.36-3.34) | 2.15 (1.37-3.37) | 1.91 (1.18-3.11) | 2.57 (1.37-4.82) |

| Class 3 obese (≥40) | 7.23 (3.89-13.4) | 7.45 (4.00-13.8) | 6.36 (3.19-12.6) | 11.5 (4.96-26.6) |

| Cigarette smoker | 1.43 (1.03-1.99) | 1.44 (1.04-2.00) | 1.38 (0.97-1.96) | 1.16 (0.71-1.89) |

| Preexisting comorbidities | ||||

| Varicose veins | 3.50 (2.09-5.87) | 3.50 (2.09-5.78) | 3.97 (2.36-6.68) | 4.88 (2.61-9.11) |

| Cardiac disease | 2.67 (1.09-6.53) | 2.59 (1.05-6.33) | 2.78 (1.02-7.53) | 2.69 (0.66-10.9) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 4.59 (1.69-12.4) | 4.61 (1.70-12.4) | 2.62 (0.64-10.6) | † |

| Preexisting hypertension | 1.46 (0.88-2.43) | — | — | — |

| Pregnancy characteristics and complications | ||||

| Preeclampsia/eclampsia | 3.31 (1.78-6.43) | 3.18 (1.81-5.72) | 4.41 (1.29-15.0) | 3.02 (1.20-7.61) |

| Gestational hypertension | 1.83 (1.10-3.04) | 1.86 (1.12-3.08) | 0.78 (0.26-2.33) | — |

| Delivery characteristics and complications | ||||

| Pregnancy length | ||||

| Normal gestation (37-42 wk) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Preterm gestation (<37 wk) | 2.25 (1.50-3.38) | 2.27 (1.51-3.40) | 2.09 (1.39-3.13)‡ | 1.90 (1.05-3.44) |

| Prolonged gestation (>42 wk) | 0.90 (0.52-1.57) | 0.91 (0.57-1.57) | 0.89 (0.49-1.60)‡ | 1.02 (0.49-2.11) |

| Mode of delivery | ||||

| Spontaneous | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | — |

| Assisted | 1.38 (0.83-2.28) | 1.41 (0.85-2.34) | 1.29 (0.76-2.20)§ | — |

| Elective cesarean | 2.39 (1.55-3.68) | 2.39 (1.55-3.69) | 2.47 (1.58-3.85)§ | — |

| Emergency cesarean | 2.78 (1.93-4.01) | 2.81 (1.95-4.05) | 2.23 (1.50-3.33)§ | — |

| Stillbirth outcome | 7.42 (3.64-15.1) | 7.57 (3.71-15.4) | 7.17 (3.33-15.4) | 11.9 (5.43-26.1) |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | 1.93 (1.30-2.87) | 1.93 (1.30-2.86) | 1.78 (1.17-2.72) | 2.35 (1.32-4.17) |

| Postpartum acute systemic infection | 4.18 (2.72-6.43) | 4.07 (2.64-6.28) | 3.72 (2.32-5.97) | 3.59 (1.85-6.96) |

| Variable . | IRR (95% CI) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MF 1 . | MF 2 . | MF 3 . | MF 3 restricted to spontaneous vaginal/assisted deliveries . | |

| Demographic and lifestyle characteristics | ||||

| Maternal age at delivery | ||||

| Age (for every year increase)* | 1.03 (1.00-1.06) | 1.02 (0.99-1.05) | 1.02 (0.99-1.05) | 1.02 (0.98-1.07) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| Normal (18.5-24.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 0.70 (0.21-2.27) | 0.69 (0.21-2.23) | 0.74 (0.23-2.39) | 0.84 (0.19-3.56) |

| Overweight (25-29.9) | 1.35 (0.88-2.07) | 1.36 (0.89-2.09) | 1.21 (0.77-1.90) | 0.67 (0.30-1.46) |

| Obese (30-40) | 2.13 (1.36-3.34) | 2.15 (1.37-3.37) | 1.91 (1.18-3.11) | 2.57 (1.37-4.82) |

| Class 3 obese (≥40) | 7.23 (3.89-13.4) | 7.45 (4.00-13.8) | 6.36 (3.19-12.6) | 11.5 (4.96-26.6) |

| Cigarette smoker | 1.43 (1.03-1.99) | 1.44 (1.04-2.00) | 1.38 (0.97-1.96) | 1.16 (0.71-1.89) |

| Preexisting comorbidities | ||||

| Varicose veins | 3.50 (2.09-5.87) | 3.50 (2.09-5.78) | 3.97 (2.36-6.68) | 4.88 (2.61-9.11) |

| Cardiac disease | 2.67 (1.09-6.53) | 2.59 (1.05-6.33) | 2.78 (1.02-7.53) | 2.69 (0.66-10.9) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 4.59 (1.69-12.4) | 4.61 (1.70-12.4) | 2.62 (0.64-10.6) | † |

| Preexisting hypertension | 1.46 (0.88-2.43) | — | — | — |

| Pregnancy characteristics and complications | ||||

| Preeclampsia/eclampsia | 3.31 (1.78-6.43) | 3.18 (1.81-5.72) | 4.41 (1.29-15.0) | 3.02 (1.20-7.61) |

| Gestational hypertension | 1.83 (1.10-3.04) | 1.86 (1.12-3.08) | 0.78 (0.26-2.33) | — |

| Delivery characteristics and complications | ||||

| Pregnancy length | ||||

| Normal gestation (37-42 wk) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Preterm gestation (<37 wk) | 2.25 (1.50-3.38) | 2.27 (1.51-3.40) | 2.09 (1.39-3.13)‡ | 1.90 (1.05-3.44) |

| Prolonged gestation (>42 wk) | 0.90 (0.52-1.57) | 0.91 (0.57-1.57) | 0.89 (0.49-1.60)‡ | 1.02 (0.49-2.11) |

| Mode of delivery | ||||

| Spontaneous | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | — |

| Assisted | 1.38 (0.83-2.28) | 1.41 (0.85-2.34) | 1.29 (0.76-2.20)§ | — |

| Elective cesarean | 2.39 (1.55-3.68) | 2.39 (1.55-3.69) | 2.47 (1.58-3.85)§ | — |

| Emergency cesarean | 2.78 (1.93-4.01) | 2.81 (1.95-4.05) | 2.23 (1.50-3.33)§ | — |

| Stillbirth outcome | 7.42 (3.64-15.1) | 7.57 (3.71-15.4) | 7.17 (3.33-15.4) | 11.9 (5.43-26.1) |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | 1.93 (1.30-2.87) | 1.93 (1.30-2.86) | 1.78 (1.17-2.72) | 2.35 (1.32-4.17) |

| Postpartum acute systemic infection | 4.18 (2.72-6.43) | 4.07 (2.64-6.28) | 3.72 (2.32-5.97) | 3.59 (1.85-6.96) |

MF 1, models are built for each risk factor separately, adjusting for demographic and lifestyle characteristics only; MF 2, as MF 1 and additionally adjusted for preexisting comorbidities; MF 3, as MF 2 and additionally adjusted for pregnancy characteristics and complications.

Age taken as a continuous variable.

No VTE events to perform analysis.

Additionally adjusted for stillbirths.

Additionally adjusted for stillbirths, postpartum infection, and postpartum hemorrhage.

Incidence rates of VTE per 100 000 person-years and incidence rate ratios restricted to women without other risk factors

| Variable . | VTE . | Rate (95% CI) . | IRR (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI ≥30 kg/m2* | |||

| No | 14 | 106 (63-179) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 13 | 528 (306-909) | 5.29 (3.28-8.65) |

| Cesarean section† | |||

| No | 14 | 100 (59-169) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 16 | 464 (284-758) | 4.32 (2.80-6.45) |

| Variable . | VTE . | Rate (95% CI) . | IRR (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI ≥30 kg/m2* | |||

| No | 14 | 106 (63-179) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 13 | 528 (306-909) | 5.29 (3.28-8.65) |

| Cesarean section† | |||

| No | 14 | 100 (59-169) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 16 | 464 (284-758) | 4.32 (2.80-6.45) |

Women without cesarean section and delivering at term or postterm and without postpartum infection, stillbirth, postpartum hemorrhage, gestational hypertension, inflammatory bowel disease, varicose veins, and cardiac disease.

Women who are not obese and delivering at term or postterm and without postpartum acute systemic infection, stillbirth, postpartum hemorrhage, gestational hypertension, inflammatory bowel disease, varicose veins, and cardiac disease.

Even among women with spontaneous vaginal deliveries, stillbirth, postpartum hemorrhage, acute infection, preterm birth, preeclampsia/eclampsia, varicose veins, and BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 were still associated with increased risks (Table 2). No associations changed when we excluded the 7% of VTE events occurring during the same hospital admission as the delivery or risk factor event where we could not establish their relative order.

Variation in VTE incidence and incidence rate ratios during postpartum periods

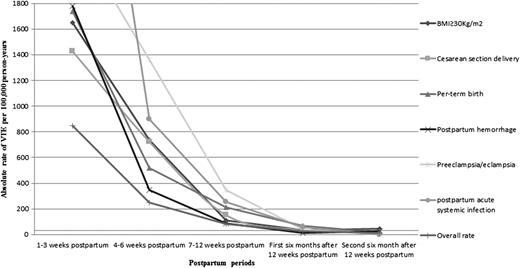

When we ascertained absolute risks of VTE within specific postpartum intervals (Table 4), we found that women with preeclampsia/eclampsia and acute systemic infection had the highest risk of VTE in during the first 3 weeks postpartum (AR = 2263 and AR = 4813 per 100 000 person-years, respectively). The risk also remained elevated in the 4 to 6 weeks postpartum for those risk factors, although to a lesser extent (AR >890 per 100 000 person-years). Women with BMI >30 kg/m2 or those who had cesarean delivery also had elevated rate of VTE up to 6 weeks postpartum (ARs >1400/100 000 person-years in weeks 1-3 and >700 in weeks 4-6). However for women with postpartum hemorrhage or preterm birth, the relative rate of VTE was only increased for the first 3 weeks postpartum (ARs = 1-2/100 person-years). Within a year after the 12 weeks postpartum (Figure 2), the absolute rate of VTE associated with those risk factors became similar to that of nonpregnant women of childbearing age (30/100 000 person-year). Our absolute rates of VTE for the above-stated risk factors were broadly similar when restricted to the first week compared with those over weeks 1 to 3 postpartum (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site).

Incidence rates of VTE per 100 000 person-years and IRRs during different periods of postpartum and around delivery

| . | 1-3 wk postpartum . | 4-6 wk postpartum . | 7-12 wk postpartum . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VTE . | Rate (95% CI)* . | IRR (95% CI)† . | VTE . | Rate (95% CI)* . | IRR (95% CI)† . | VTE . | Rate (95% CI)* . | IRR (95% CI)† . | |

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | |||||||||

| No | 40 | 598 (438-815) | 1.00 | 9 | 161 (84-311) | 1.00 | 11 | 101 (56-182) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 27 | 1650 (1131-2406) | 2.74 (1.66-4.52) | 10 | 735 (395-1366) | 4.18 (1.65-10.5) | 3 | 112 (36-350) | 0.97 (0.4-3.88) |

| Preeclampsia/eclampsia | |||||||||

| No | 119 | 814 (680-974) | 1.00 | 27 | 221 (151-322) | 1.00 | 18 | 75 (47-119) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 8 | 2263 (1131-4525) | 2.54 (1.23-5.26) | 4 | 1360 (510-3623) | 5.41 (1.84-15.8) | 2 | 349 (87-1397) | 4.76 (1.05-21.6) |

| Length of gestation | |||||||||

| Normal (36-42 wk) | 98 | 788 (646-960) | 1.00 | 22 | 211 (139-321) | 1.00 | 15 | 73 (44-122) | 1.00 |

| Preterm (<37 wk) | 20 | 1736 (1120-2691) | 2.04 (1.26-3.28) | 5 | 519 (216-1247) | 1.92 (0.77-4.78) | 4 | 213 (80-569) | 2.81 (0.86-9.16) |

| Cesarean section | |||||||||

| No | 75 | 662 (528-831) | 1.00 | 9 | 95 (49-182) | 1.00 | 11 | 59 (33-107) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 52 | 1425 (1086-1870) | 1.89 (1.30-2.74) | 22 | 722 (475-1096) | 6.99 (3.07-15.9) | 9 | 151 (78-290) | 2.22 (0.85-5.79) |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | |||||||||

| No | 103 | 756 (623-917) | 1.00 | 27 | 237 (163-346) | 1.00 | 18 | 81 (51-129) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 24 | 1778 (1192-2653) | 2.22 (1.42-3.47) | 4 | 347 (130-353) | 1.38 (0.47-4.04) | 2 | 88 (22-353) | 1.00 (0.22-4.46) |

| Postpartum acute systemic infection | |||||||||

| No | 114 | 775 (645-932) | 1.00 | 28 | 230 (158-333) | 1.00 | 18 | 76 (48-121) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 13 | 4813 (279-828) | 5.99 (3.36-10.6) | 3 | 899 (289-2787) | 3.56 (1.08-11.7) | 2 | 253 (63-1011) | 3.27 (0.73-14.6) |

| . | 1-3 wk postpartum . | 4-6 wk postpartum . | 7-12 wk postpartum . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VTE . | Rate (95% CI)* . | IRR (95% CI)† . | VTE . | Rate (95% CI)* . | IRR (95% CI)† . | VTE . | Rate (95% CI)* . | IRR (95% CI)† . | |

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | |||||||||

| No | 40 | 598 (438-815) | 1.00 | 9 | 161 (84-311) | 1.00 | 11 | 101 (56-182) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 27 | 1650 (1131-2406) | 2.74 (1.66-4.52) | 10 | 735 (395-1366) | 4.18 (1.65-10.5) | 3 | 112 (36-350) | 0.97 (0.4-3.88) |

| Preeclampsia/eclampsia | |||||||||

| No | 119 | 814 (680-974) | 1.00 | 27 | 221 (151-322) | 1.00 | 18 | 75 (47-119) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 8 | 2263 (1131-4525) | 2.54 (1.23-5.26) | 4 | 1360 (510-3623) | 5.41 (1.84-15.8) | 2 | 349 (87-1397) | 4.76 (1.05-21.6) |

| Length of gestation | |||||||||

| Normal (36-42 wk) | 98 | 788 (646-960) | 1.00 | 22 | 211 (139-321) | 1.00 | 15 | 73 (44-122) | 1.00 |

| Preterm (<37 wk) | 20 | 1736 (1120-2691) | 2.04 (1.26-3.28) | 5 | 519 (216-1247) | 1.92 (0.77-4.78) | 4 | 213 (80-569) | 2.81 (0.86-9.16) |

| Cesarean section | |||||||||

| No | 75 | 662 (528-831) | 1.00 | 9 | 95 (49-182) | 1.00 | 11 | 59 (33-107) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 52 | 1425 (1086-1870) | 1.89 (1.30-2.74) | 22 | 722 (475-1096) | 6.99 (3.07-15.9) | 9 | 151 (78-290) | 2.22 (0.85-5.79) |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | |||||||||

| No | 103 | 756 (623-917) | 1.00 | 27 | 237 (163-346) | 1.00 | 18 | 81 (51-129) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 24 | 1778 (1192-2653) | 2.22 (1.42-3.47) | 4 | 347 (130-353) | 1.38 (0.47-4.04) | 2 | 88 (22-353) | 1.00 (0.22-4.46) |

| Postpartum acute systemic infection | |||||||||

| No | 114 | 775 (645-932) | 1.00 | 28 | 230 (158-333) | 1.00 | 18 | 76 (48-121) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 13 | 4813 (279-828) | 5.99 (3.36-10.6) | 3 | 899 (289-2787) | 3.56 (1.08-11.7) | 2 | 253 (63-1011) | 3.27 (0.73-14.6) |

Rate per 100 000 person-years.

Adjusted for demographic characteristics, preexisting medical comorbidities, and pregnancy-related complications and characteristics when not stratified by them.

Number needed to treat during weeks of postpartum

Table 5 contains the risk of VTE per 100 000 pregnancies and NNT for each specific risk factor. Based on a 50% risk reduction, we observed that during the first 3 weeks of postpartum, the lowest NNT was 1173 for women with infection, followed by women with preeclampsia/eclampsia (NNT = 1289). The NNT values were all around 1600 for women with preterm births, postpartum hemorrhage, or BMI > 30 kg/m2. At 4 to 6 weeks postpartum, the lowest NNT was for women with preeclampsia/eclampsia (NNT = 2557), followed by BMI > 30 kg/m2 (NNT = 4734) and cesarean delivery (NNT = 4816).

Absolute rate of VTE per 100 000 pregnancies and NNT

| Risk factors . | 1-3 wk postpartum . | 4-6 wk postpartum . | 7-12 wk postpartum . |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | |||

| Rate (95% CI) | 113 (74-164) | 42 (20-77) | 13 (2-37) |

| NNT (50% RR) | 1771 | 4734 | 15 398 |

| NNT (88% RR) | 1006 | 2690 | 8749 |

| Preeclampsia/eclampsia | |||

| Rate (95% CI) | 155 (67-305) | 78 (21-200) | 40 (48-145) |

| NNT (50% RR) | 1289 | 2557 | 4974 |

| NNT (88% RR) | 733 | 1453 | 2826 |

| Per-term birth | |||

| Rate (95% CI) | 119 (73-183) | 30 (9-69) | 24 (6-62) |

| NNT (50% RR) | 1683 | 6700 | 8249 |

| NNT (88% RR) | 956 | 3807 | 4687 |

| Cesarean section | |||

| Rate (95% CI) | 98 (72-127) | 42 (26-63) | 17 (7-33) |

| NNT (50% RR) | 2050 | 4816 | 11 502 |

| NNT (88% RR) | 1165 | 2737 | 6535 |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | |||

| Rate (95% CI) | 122 (78-181) | 20 (5-51) | 10.2 (1-36) |

| NNT (50% RR) | 1642 | 10 018 | 19 689 |

| NNT (88% RR) | 933 | 5692 | 11 187 |

| Postpartum acute systemic infection | |||

| Rate (95% CI) | 249 (15-38) | 39 (8-114) | 27 (3-96) |

| NNT (50% RR) | 1173 | 5090 | 7479 |

| NNT (88% RR) | 667 | 2892 | 4249 |

| Risk factors . | 1-3 wk postpartum . | 4-6 wk postpartum . | 7-12 wk postpartum . |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | |||

| Rate (95% CI) | 113 (74-164) | 42 (20-77) | 13 (2-37) |

| NNT (50% RR) | 1771 | 4734 | 15 398 |

| NNT (88% RR) | 1006 | 2690 | 8749 |

| Preeclampsia/eclampsia | |||

| Rate (95% CI) | 155 (67-305) | 78 (21-200) | 40 (48-145) |

| NNT (50% RR) | 1289 | 2557 | 4974 |

| NNT (88% RR) | 733 | 1453 | 2826 |

| Per-term birth | |||

| Rate (95% CI) | 119 (73-183) | 30 (9-69) | 24 (6-62) |

| NNT (50% RR) | 1683 | 6700 | 8249 |

| NNT (88% RR) | 956 | 3807 | 4687 |

| Cesarean section | |||

| Rate (95% CI) | 98 (72-127) | 42 (26-63) | 17 (7-33) |

| NNT (50% RR) | 2050 | 4816 | 11 502 |

| NNT (88% RR) | 1165 | 2737 | 6535 |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | |||

| Rate (95% CI) | 122 (78-181) | 20 (5-51) | 10.2 (1-36) |

| NNT (50% RR) | 1642 | 10 018 | 19 689 |

| NNT (88% RR) | 933 | 5692 | 11 187 |

| Postpartum acute systemic infection | |||

| Rate (95% CI) | 249 (15-38) | 39 (8-114) | 27 (3-96) |

| NNT (50% RR) | 1173 | 5090 | 7479 |

| NNT (88% RR) | 667 | 2892 | 4249 |

Absolute rates per 100 000 are based on the number of pregnancies complicated by a particular risk factor (Table 1) divided by VTE events. It does not consider postpartum hemorrhage or postpartum infections as time-varying covariates nor censor postpartum follow-up time after a VTE event.

RR, risk reduction.

Discussion

Main findings

This study provides precise absolute and relative risks of postpartum VTE for maternal risk factors occurring before, during, and after childbirth and quantifies which have the greatest impact on VTE during specific postpartum intervals. We found that women with stillbirths, preterm birth, postpartum hemorrhage, postpartum acute infection, cesarean delivery, and high BMI (>30 kg/m2) were at a high risk of postpartum VTE. The augmented risks associated with these factors were not explained by other pregnancy characteristics and complications, preexisting comorbidities, demographics, or lifestyle factors considered in this study. We found that for women with preeclampsia/eclampsia, BMI >30 kg/m2, infection, or those having cesarean delivery, the rate of VTE remained elevated for 6 weeks postpartum. However, for women with postpartum hemorrhage or preterm birth, the relative rate of VTE was only increased for the first 3 weeks postpartum, with NNTs of 933 and 956, respectively.

Strengths and weaknesses

Our study used information on more than 222 000 pregnancies with postpartum follow-up using linked primary and secondary care data that cover 3% of the UK population and have similar age and sex distribution to the national population.26 Our study findings are therefore reasonably generalizable to pregnant women in England with no prior diagnosis of VTE and to women in other high-income countries with similar health care systems. By using linked primary and secondary care data, we had comprehensive medical information on women’s baseline health risks recorded before pregnancy as well as their pregnancy and delivery health records, all of which were prospectively recorded. This enabled us not only to assess the impact of risk factors on postpartum VTE while adequately controlling for confounding factors but also to assess the impact of risk factors on the incidence of VTE during specific postpartum periods.

Another strength of this study was our use of a conceptual hierarchical framework to adjust our estimates for potential confounding factors. Most previous studies have used stepwise regression models for their risk factor analysis. This is solely reliant on statistical association rather than any conceptual basis for the interrelationship between factors where all explanatory variables are treated at the same hierarchical level, an assumption that may not be appropriate in all cases, particularly for closely related factors around pregnancy and delivery. In contrast, our categorization of risk factors and adjustments in hierarchical order enabled us to better evaluate the extent to which the effect of a particular risk factor had a direct effect or was mediated by other risk factors. (eg, whether the effect of stillbirth is mediated by more distant risk factors such as age and/or BMI).

A limitation of this analysis is our inability to establish temporality between VTE and risk factors that were recorded during the same hospital admission as the VTE event (eg, postpartum hemorrhage). However, this only affected 7% of our cases, and our sensitivity analysis demonstrated that removing those women from our analysis did not affect our estimates. We also acknowledge that we were not able to consider certain risk factors such as family history of VTE and thrombophilia. However, we believe that the following arguments should be considered. Firstly, although family history may be important, it has rarely been looked at in previous population-based studies, possibly for the reason that accurate recall of a family history is problematic. Secondly, because thrombophilia screening is not routinely recommended for pregnant women, pragmatically it cannot be used as a predictor for VTE outcome. We did not distinguish between fatal and nonfatal VTEs based on the notion that the RCOG guidelines10 are focused on preventing all VTEs.

Our VTE definition and birth outcomes have been validated with positive predictive values of 84%19 and 90%,20 respectively. These studies do not give an indication of negative predictive value (which is rarely possible from routine clinical data as negative tests are less likely to be recorded), and we therefore cannot rule out the possibility of a small number of false negatives. However, our absolute rate of VTE during the postpartum period is comparable to the pooled estimates of the previous studies on the subject.15 Secondly, only around 2%27 of births in England take place outside hospital, thereby minimizing impact on our estimates. Moreover, our prevalence figures for hypertension, preeclampsia, diabetes, cesarean delivery, stillbirths, postpartum hemorrhage, and preterm births are very similar to those from national studies or other similarly developed countries.28-34 Prevalence figures for key pregnancy statistics were also similar between our study population and all recorded hospital deliveries in England from maternity HES (supplemental Table 2), indicating that it was closely representative of the maternity population overall.

One way of assessing the effectiveness of intervention is by calculating NNT. For instance, if we were to assume that thromboprophylaxis reduce the risk of postpartum VTE by 88% based on observational data in pregnant women25 during the first 3 weeks postpartum, then based on our estimates of absolute rates, 144 VTE events could be prevented per year during that period in women whose pregnancies end in cesarean delivery (NNT = 1165). If we assume that 50% of the women with cesarean delivery are currently receiving some form of thromboprophylaxis, then the corresponding NNT would be 1526 (based on a 50% risk reduction). These values should be interpreted with caution, as they are not based on randomized controlled trial data, and future studies should assess the risk-benefit and cost implications.

Finally, we acknowledge that some of the numbers in our postpartum analysis are small, which could lead to type 2 error. However, a large study conducted by Kamel et al13 (which used information on 1.6 million pregnancies but did not assess risk factors) showed an overall elevated risk of thrombosis that persisted until at least 12 weeks after delivery. This might be due to certain risk factors that we have highlighted in our study.

Comparison with other literature

Our relative increased risks observed for women with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, cardiac disease, varicose veins, preeclampsia/eclampsia, and infection are in concordance with most previous studies.6,7,9,35-37 Additionally, our study findings support increased risks of more than twofold and sixfold in women experiencing preterm delivery and stillbirth, respectively, both of which have been previously reported.9,14,36 We did not observe a difference in the risk of VTE between elective and emergency cesarean delivery, which has been found in other few studies,35,38 that were able to compare this. This may be due to differences in the study design and population studied. For instance, our finding of an increased risk of VTE associated with elective cesarean delivery contradicts that of Jacobsen et al,35 who only found an increased VTE risk associated with emergency cesarean delivery, but not elective. However, they obtained VTE cases using a patient registry for the whole population of Norway and controls from only a single hospital where they had many more elective cesarean deliveries (9.2%) compared with the general population (4.8%), which may have biased their estimates toward the null. Another possible explanation is the fact that definition for elective and emergency cesarean delivery remains inconsistent within and between countries,39 so our discordant findings could be because of differences in the indication and urgency of cesarean delivery between different countries. For example, the rate of cesarean delivery is much higher in the United Kingdom compared with Norway (25% vs 17%).40

Only few studies36,41 have evaluated the impact of multiple risk factors on the absolute and relative rates of VTE in different specific postpartum periods. Recently Tepper et al41 concluded that the risk of VTE remains consistently high up to 12 weeks postpartum among those who undergo cesarean section, develop postpartum hemorrhage, or have high BMI, which is in contrast to our study. This could be due to the fact the Tepper et al study did not stratify risk within the 4 to 12 weeks during which the risk of VTE varies markedly. Nonetheless, our risk factor estimates during the first 3 weeks postpartum are consistent.

The higher relative risk of VTE that we found associated with obesity and cesarean delivery in weeks 4 to 6 following delivery compared with the first 3 weeks may be explained by the fact that those women would have received some form of thromboprophylaxis. However, it is noteworthy that the current UK thromboprophylaxis guidelines10 only recommend 7 days of pharmacologic prophylaxis for the majority of high-risk women, whereas we are demonstrating later extended risks of VTE following cesarean delivery. We therefore think that an assumption that this early thromboprophylaxis would greatly influence our absolute risk both within the first 3 weeks postpartum and subsequently is unlikely to be true. Additionally, there is also evidence suggesting the underuse of postcesarean thromboprophylaxis.42 Moreover, we observed no overall statistically significant difference in the rate of VTE among those with cesarean delivery or BMI ≥30 kg/m2 when we assessed this before and after 2004, suggesting minimal impact of the current guidelines on our estimates.

Clinical implication

Our results have important implications for deciding how and when thromboprophylaxis is delivered in the obstetric health care setting and will help targeting of thromboprophylaxis in the following ways. Firstly, our results suggest that the increased risk of VTE extends beyond the currently suggested 7 days for women with certain risk factors. Secondly we found that for women with preeclampsia/eclampsia, BMI >30 kg/m2, infection, or those having cesarean delivery, the rate of VTE remained elevated for 6 weeks postpartum. However, for women with postpartum hemorrhage or preterm birth, the relative rate of VTE was only increased for the first 3 weeks postpartum, with a NNT of 1739. This suggests that the time period of increased risk of VTE during the postpartum is dependent on the type of risk factors that should be considered when planning thromboprophylaxis. Finally, women whose pregnancies are complicated by stillbirth, high BMI, preterm birth, cesarean delivery, postpartum acute infection, or postpartum hemorrhage should be considered at high risk (AR = 0.6-2.5 per 100 person-years) of VTE postnatally. The augmented risks associated with these factors are not explained by other pregnancy characteristics and complications, preexisting comorbidities, demographics, or lifestyle factors. Therefore, pregnancies complicated by any one of those factors may require careful consideration in terms of VTE risk assessment during the immediate postpartum.

Recommendations regarding postpartum thromboprophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin for women with the above highlighted risk factors will of course be highly dependent on the combination of the risk reduction from prophylaxis and any adverse events from its use, both of which were beyond the scope of this study. Nevertheless, our study provides the most robust, comprehensive, and clinically relevant information on risk factors for postpartum VTE that can be of direct use in formulating such guidelines.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

A.A.S. is funded by a scholarship awarded by the Aga Khan Foundation. J.W. is funded by a University of Nottingham senior clinical research fellowship, which also contributes to A.A.S.’s funding.

Authorship

Contribution: A.A.S., L.J.T., J.W., and M.J.G. conceived the idea for the study, with K.M.F. also making important contributions to the design of the study; A.A.S. carried out the data management and analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; C.N.-P. provided clinical input and interpretation at all stages of the project; all authors were involved in the interpretation of the data, contributed toward critical revision of the manuscript, and approved the final draft; A.A.S. had full access to all of the data; and A.A.S. and L.J.T. had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.N.-P. was codeveloper of the currently available guidelines on VTE prophylaxis in pregnancy issued by the RCOG (Green-top Guideline 37a). C.N.-P. has also received honoraria for giving lectures from Leo Pharma and Sanofi Aventis (makers of tinzaparin and enoxaparin low-molecular-weight heparins used in obstetric thromboprophylaxis) and has received payment from Leo Pharma for development of an educational “slide kit” about obstetric thromboprophylaxis. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Alyshah Abdul Sultan, Division of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Nottingham, City Hospital, Nottingham, UK, NG5 1PB; e-mail: alyshah.sultan@hotmail.com and Laila J. Tata, Division of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Nottingham, City Hospital, Nottingham, UK, NG5 1PB; e-mail: laila.tata@nottingham.ac.uk.