In this issue of Blood, Abdul Sultan et al describe risk factors for venous thromboembolism (VTE) after pregnancy with consideration of duration of risk in differing clinical circumstances.1 They provide essential information toward a data-driven foundation on which clinical guidelines may be refined.

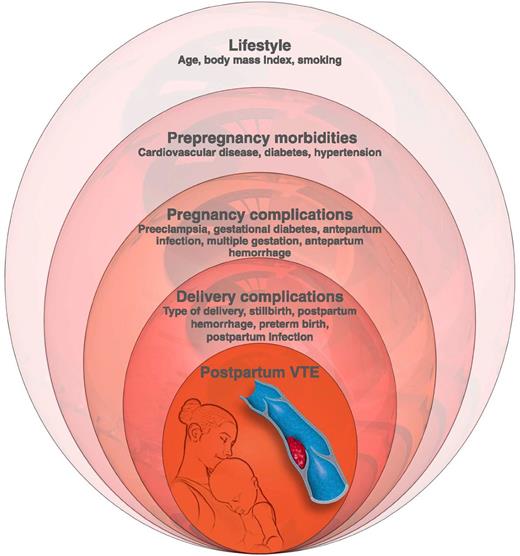

Conceptual model of levels of risk factors for postpartum VTE, based on hierarchical analysis used by Abdul Sultan et al. Professional illustration by Luk Cox, Somersault18:24.

Conceptual model of levels of risk factors for postpartum VTE, based on hierarchical analysis used by Abdul Sultan et al. Professional illustration by Luk Cox, Somersault18:24.

Pregnancy-related VTE represents one of the leading causes of maternal mortality and morbidity worldwide.2,3 In pregnancy and postpartum, several factors converge to increase VTE risk, including altered coagulation factors, mechanical obstruction by the enlarged uterus, and pregnancy-related endothelial changes. Pregnancy-related VTE occurs in ∼1 to 2 of every 1000 deliveries.3,4 Relative to nonpregnant, reproductive age women, pregnant women have a 4-fold higher risk of VTE,4 and postpartum risk is further increased, with estimates ranging from 9-fold to 84-fold higher.4,5

Clinical guidelines addressing VTE risk and thromboprophylaxis aim to target high-risk populations to effectively prevent these complications.6,7 However, the data on which guidelines have been developed rely on observational studies, extrapolation from other populations, and expert opinion. In fact, the primary conclusion of the guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians was that there is an urgent need for improved data to address these questions.7 In the last few years, several investigators have sought to address this identified need, but many questions remain.

Clinical factors associated with VTE risk are well established2-5,7-9 and, as suggested by Abdul Sultan et al, may be best considered in a hierarchical framework (see figure). Patient characteristics prior to pregnancy that may influence risk include maternal age, race, genetic thrombophilias, obesity, and smoking. Disease conditions prior to pregnancy that are associated with higher risk include prior VTE, anemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, heart disease, and sickle cell disease. During pregnancy, antepartum hemorrhage, infection, hyperemesis, hospitalization, bed rest or other immobilization, preeclampsia, fetal growth restriction, and multiple gestation are associated with higher risk. At the time of delivery and in the immediate postpartum time frame, risk factors include cesarean section, postpartum hemorrhage, infection, and other serious systemic illness.

To optimize thromboprophylaxis strategies, an understanding of the variance in risk over time and in particular the duration of risk postpartum is essential. In prior work, Abdul Sultan et al established that overall, VTE risk is highest in the third trimester of pregnancy and in the first 3 weeks postpartum.2 However, other studies have suggested that in some clinical scenarios, postpartum risk may persist for up to 12 weeks after delivery.5,8

It is clear that VTE risk varies over time and with clinical circumstances and that thromboprophylaxis guidelines therefore cannot fall into a one-size-fits-all category. The need for comprehensive, prospective data with which to customize recommendations remains; however, in the current study, Abdul Sultan et al have uniquely addressed the intersection of risk factors and timing of risk.

Using a conceptual hierarchical modeling approach, the authors evaluated data from linked primary and secondary medical information from a large study population representative of the general United Kingdom population. Their statistical technique allowed exploration of the complex interactions between confounding variables and estimation of VTE risk in specific postpartum time periods, up to 12 weeks postpartum. Overall, they found that women with obesity, preeclampsia, infection, and cesarean delivery had a higher risk of VTE that persisted for 6 weeks after delivery. In contrast, the higher risk of VTE seen in women with postpartum hemorrhage or preterm birth persisted for 3 weeks postpartum.

Prospective—ideally, randomized—studies remain essential to optimize postpartum thromboprophylaxis guidelines. However, this study by Abdul Sultan et al demonstrates the importance of tailoring recommendations according to each patient’s clinical circumstances and constellation of risk factors and provides needed data on which such decisions may be informed.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.