Key Points

NR4A1 is downregulated in aggressive B-cell lymphoma.

Its overexpression causes apoptosis in lymphoma cells and suppresses lymphoma formation in vivo.

Abstract

NR4A1 (Nur77) and NR4A3 (Nor-1) function as tumor suppressor genes as demonstrated by the rapid development of acute myeloid leukemia in the NR4A1 and NR4A3 knockout mouse. The aim of our study was to investigate NR4A1 and NR4A3 expression and function in lymphoid malignancies. We found a vastly reduced expression of NR4A1 and NR4A3 in chronic lymphocytic B-cell leukemia (71%), in follicular lymphoma (FL, 70%), and in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL, 74%). In aggressive lymphomas (DLBCL and FL grade 3), low NR4A1 expression was significantly associated with a non–germinal center B-cell subtype and with poor overall survival. To investigate the function of NR4A1 in lymphomas, we overexpressed NR4A1 in several lymphoma cell lines. Overexpression of NR4A1 led to a higher proportion of lymphoma cells undergoing apoptosis. To test the tumor suppressor function of NR4A1 in vivo, the stable lentiviral-transduced SuDHL4 lymphoma cell line harboring an inducible NR4A1 construct was further investigated in xenografts. Induction of NR4A1 abrogated tumor growth in the NSG mice, in contrast to vector controls, which formed massive tumors. Our data suggest that NR4A1 has proapoptotic functions in aggressive lymphoma cells and define NR4A1 as a novel gene with tumor suppressor properties involved in lymphomagenesis.

Introduction

Aggressive B-cell lymphomas, consisting of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicular lymphoma grade 3 (FLIII), are the most common lymphoid malignancies in adults, comprising almost 50% of all lymphomas.1 DLBCL is the most common type of aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), accounting for 30% to 40% of all lymphomas in adults.2 Gene expression profiling showed that DLBCLs cluster in 3 different subtypes based on their similarity between expression patterns and their cellular origin: germinal center B-cell (GCB)–like DLBCL, activated B-cell (ABC)–like DLBCL, and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL).2 These subtypes of DLBCL are associated with different overall survival rates after anthracycline-based chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, oncovin, and prednisone [CHOP]): overall survival is favorable in patients with a GCB subtype and inferior in the ABC subtype.3 Although novel techniques have shed some light on the molecular basis of lymphomagenesis, the genetic mechanisms underlying the development of aggressive lymphoma are still incompletely understood.4

NR4A1 (Nur77, TR3), NR4A2 (Nurr1), and NR4A3 (NOR-1) are nuclear orphan receptors of the Nur77 family and are widely expressed in different types of tissues, such as skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, heart, kidney, T cells, liver, and brain. They are known as immediate early or stress response genes and can be induced by a wide range of physiological signals. Their activation is generally short-lived, and the cellular outcome is a stimulus-dependent and cell context–dependent activation of NR4A target genes that regulate cell cycle, apoptosis, inflammation, atherogenesis, metabolism, or DNA repair. As described more recently, they are also involved in tumorigenesis.5-7 Recently, NR4A1 and NR4A3 were identified functioning as tumor suppressor genes in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The deletion of both nuclear receptors led to the rapid development of AML in mice. A loss of NR4A1 and NR4A3 was also found in leukemic blasts from human AML patients, irrespective of karyotype.8 Additionally, NR4A1 and NR4A3 hypoallelic mice develop a chronic myeloid malignancy in rare cases, progression to AML.9

The aim of our study was to comprehensively and functionally investigate the NR4A expression in lymphoid malignancies. Here we show that NR4A1 and NR4A3 expression is downregulated in patients with aggressive B-cell lymphomas and that a low NR4A1 expression is associated with poor cancer-specific survival. We demonstrate that the overexpression of NR4A1 in aggressive lymphoma cells causes apoptosis in vitro and leads to reduced tumor growth in a xenograft model. Additionally, the activation of NR4A1 in aggressive lymphoma cells by cytosporone B (CsnB), a binding agonist of NR4A1,10 induced NR4A1 expression followed by apoptosis of lymphoma cells. Collectively, these results define NR4A1 as novel gene with tumor suppressive properties in lymphoid malignancies.

Materials and methods

Patient samples, expression analysis, and cell culture

Fresh frozen material from various indolent (n = 75) and aggressive (n = 62) lymphoid malignancies diagnosed between 1988 and 2010 was obtained from the Institute of Pathology at the Medical University Graz: 7 chronic lymphocytic B-cell leukemia (B-CLL), 10 FL grade 2 (FLII), 15 marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (MZBCL), 8 hairy cell leukemia, 7 Morbus Waldenström, 15 immunocytoma, 8 multiple myeloma and 7 prolymphocytic leukemia, 12 FLIII, 5 Burkitt lymphoma (BL), 5 PMBCL, 23 DLBCL, 9 mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), and 8 peripheral T-cell NHL malignancies. Also, Hodgkin lymphoma (HD; 9), acute lymphatic leukemia (ALL; 8), AML (n = 4), and normal controls [peripheral B and T cells (n = 4) and GCBs and mantle B cells (MC-Bs; n = 5) of healthy donors] were included (Table 1). All lymphomas were classified according to the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms.11 To subclassify DLBCLs into non-GCB and GCB, the Hans algorithm was applied.12 Tissue retrieval was done according to the regulations of the local institutional review board and data safety laws. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Materials used for the NR4A expression analyses and results of NR4A1 and NR4A3 expression compared with GCBs

| . | n . | Reduction of NR4A1 and NR4A3 . | Reduction of NR4A1 . | Fisher* . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) > 50% . | n (%): 50% to 25% . | n (%) < 25% . | n (%) > 50% . | n (%): 50% to 25% . | n (%) < 25% . | P . | ||

| Nonneoplastic controls | ||||||||

| Peripheral CD19+ B cells | 4 | — | — | 4 (100%) | — | — | 4 (100%) | na |

| Peripheral CD3+ T cells | 4 | — | — | 4 (100%) | — | — | 4 (100%) | na |

| Hyperplastic lymph nodes | 9 | — | 4 (44%) | 5 (56%) | — | 4 (44%) | 5 (56%) | ns |

| GCBs | 5 | — | — | 5 (100%) | — | — | 5 (100%) | na |

| Mantle cells | 5 | — | — | 5 (100%) | — | — | 5 (100%) | na |

| Marginal zone B cells | 5 | — | — | 5 (100%) | — | — | 5 (100%) | na |

| Tonsillar CD3+ T cells | 5 | — | 2 (40%) | 3 (60%) | — | 3 (60%) | 2 (40%) | ns |

| Indolent NHLs | ||||||||

| B-CLL | 7 | 5 (71%) | 2 (29%) | — | 6 (86%) | 1 (14%) | — | .001 |

| FLII | 10 | 7 (70%) | 2 (20%) | 1 (10%) | 7 (70%) | 2 (20%) | 1 (10%) | .002 |

| MZBCL | 15 | 9 (60%) | — | 6 (40%) | 9 (60%) | — | 6 (40%) | .038 |

| MALT lymphoma | 6 | 3 (50%) | — | 3 (50%) | 3 (50%) | — | 3 (50%) | ns |

| Nodal MZBCL | 9 | 6 (67%) | — | 3 (33%) | 6 (67%) | — | 3 (33%) | .031 |

| Hairy cell leukemia | 8 | 2 (25%) | 1 (12.5%) | 5 (62.5%) | 2 (25%) | 1 (12.5%) | 5 (62.5%) | ns |

| Morbus Waldenström | 7 | 2 (29%) | 2 (29%) | 3 (42%) | 4 (57%) | 3 (43%) | — | .001 |

| Immunocytoma | 15 | 5 (33%) | 1 (7%) | 9 (60%) | 7 (46%) | 4 (27%) | 4 (27%) | .016 |

| Multiple myeloma | 6 | — | — | 6 (100%) | — | — | 6 (100%) | na |

| B-cell prolymphocytic leukemia | 7 | 1 (14%) | — | 6 (86%) | 2 (28%) | — | 5 (72%) | .470 |

| Aggressive NHLs | ||||||||

| FLIII | 12 | 9 (75%) | 3 (25%) | — | 10 (83%) | 2 (17%) | — | <.001 |

| BL | 5 | 3 (60%) | 1 (20%) | 1 (20%) | 3 (60%) | 1 (20%) | 1 (20%) | .048 |

| PMBCL | 5 | 5 (100%) | — | — | 5 (100%) | — | — | .008 |

| DLBCL | 23 | 20 (87%) | 1 (4%) | 2 (9%) | 21 (91%) | — | 2 (9%) | <.001 |

| MCL | 9 | 7 (78%) | — | 2 (22%) | 8 (89%) | — | 1 (11%) | .003 |

| Peripheral T-cell NHL | 8 | — | — | 8 (100%) | — | 2 (25%) | 6 (75%) | ns |

| HD | 9 | 6 (67%) | 1 (11%) | 2 (22%) | 6 (67%) | 1 (11%) | 2 (22%) | .021 |

| ALL | 8 | 6 (75%) | 2 (25%) | — | 6 (75%) | 2 (25%) | — | .001 |

| . | n . | Reduction of NR4A1 and NR4A3 . | Reduction of NR4A1 . | Fisher* . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) > 50% . | n (%): 50% to 25% . | n (%) < 25% . | n (%) > 50% . | n (%): 50% to 25% . | n (%) < 25% . | P . | ||

| Nonneoplastic controls | ||||||||

| Peripheral CD19+ B cells | 4 | — | — | 4 (100%) | — | — | 4 (100%) | na |

| Peripheral CD3+ T cells | 4 | — | — | 4 (100%) | — | — | 4 (100%) | na |

| Hyperplastic lymph nodes | 9 | — | 4 (44%) | 5 (56%) | — | 4 (44%) | 5 (56%) | ns |

| GCBs | 5 | — | — | 5 (100%) | — | — | 5 (100%) | na |

| Mantle cells | 5 | — | — | 5 (100%) | — | — | 5 (100%) | na |

| Marginal zone B cells | 5 | — | — | 5 (100%) | — | — | 5 (100%) | na |

| Tonsillar CD3+ T cells | 5 | — | 2 (40%) | 3 (60%) | — | 3 (60%) | 2 (40%) | ns |

| Indolent NHLs | ||||||||

| B-CLL | 7 | 5 (71%) | 2 (29%) | — | 6 (86%) | 1 (14%) | — | .001 |

| FLII | 10 | 7 (70%) | 2 (20%) | 1 (10%) | 7 (70%) | 2 (20%) | 1 (10%) | .002 |

| MZBCL | 15 | 9 (60%) | — | 6 (40%) | 9 (60%) | — | 6 (40%) | .038 |

| MALT lymphoma | 6 | 3 (50%) | — | 3 (50%) | 3 (50%) | — | 3 (50%) | ns |

| Nodal MZBCL | 9 | 6 (67%) | — | 3 (33%) | 6 (67%) | — | 3 (33%) | .031 |

| Hairy cell leukemia | 8 | 2 (25%) | 1 (12.5%) | 5 (62.5%) | 2 (25%) | 1 (12.5%) | 5 (62.5%) | ns |

| Morbus Waldenström | 7 | 2 (29%) | 2 (29%) | 3 (42%) | 4 (57%) | 3 (43%) | — | .001 |

| Immunocytoma | 15 | 5 (33%) | 1 (7%) | 9 (60%) | 7 (46%) | 4 (27%) | 4 (27%) | .016 |

| Multiple myeloma | 6 | — | — | 6 (100%) | — | — | 6 (100%) | na |

| B-cell prolymphocytic leukemia | 7 | 1 (14%) | — | 6 (86%) | 2 (28%) | — | 5 (72%) | .470 |

| Aggressive NHLs | ||||||||

| FLIII | 12 | 9 (75%) | 3 (25%) | — | 10 (83%) | 2 (17%) | — | <.001 |

| BL | 5 | 3 (60%) | 1 (20%) | 1 (20%) | 3 (60%) | 1 (20%) | 1 (20%) | .048 |

| PMBCL | 5 | 5 (100%) | — | — | 5 (100%) | — | — | .008 |

| DLBCL | 23 | 20 (87%) | 1 (4%) | 2 (9%) | 21 (91%) | — | 2 (9%) | <.001 |

| MCL | 9 | 7 (78%) | — | 2 (22%) | 8 (89%) | — | 1 (11%) | .003 |

| Peripheral T-cell NHL | 8 | — | — | 8 (100%) | — | 2 (25%) | 6 (75%) | ns |

| HD | 9 | 6 (67%) | 1 (11%) | 2 (22%) | 6 (67%) | 1 (11%) | 2 (22%) | .021 |

| ALL | 8 | 6 (75%) | 2 (25%) | — | 6 (75%) | 2 (25%) | — | .001 |

MALT, mucosa associated lymphoid tissue; na, not applicable because of equality; ns, not significant.

Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the NR4A1 expression distribution to GCBs.

Semiquantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RQ-PCR) for NR4A1, NR4A2, NR4A3, Bim 1,6, Bim 9, Puma, BCL2, BCLX, MCL1, Trail, Fas-L, DR4, DR5, and Fas (primers are listed in supplemental Table 1; see the Blood Web site) was performed using an ABI Prism 7000 Detection system (Applied Biosystems). PCR reaction and data analysis were performed as previously described by our group.13 GAPDH, PPIA, and HPRT1, which are known to exhibit the lowest variability among lymphoid malignancies,14 served as housekeeping genes.

Details of western blot and immunohistochemical analyses, sequencing, DNA methylation, and gene copy number analysis are provided in supplemental Methods.

For in vitro analysis, the human B-cell lymphoma cell lines Karpas422, SuDHL4, RI-1, and U2932, obtained from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (Bonn, Germany), and the immortalized B-cell UH3 (kindly provided by R. Dalla-Favera, Institute of Cancer Genetics, Columbia University, New York, NY) were used. Further details on all cell culture procedures are provided in supplemental Methods.

Isolation of GCBs and MC-Bs as nonneoplastic controls

Tonsils from young patients undergoing routine tonsillectomy were disaggregated and separated by Ficoll (GE Healthcare). The specific monoclonal antibodies used were anti-CD5 phycoerythrin, anti-CD20 allophycocyanin, and anti-CD77 fluorescein isothiocyanate, all from BD Biosciences. Cells were sorted using the FACSAria (BD Biosciences) into GCBs (CD20+, CD77+) and MC-Bs (CD20+, CD5+).

NR4A1 expression and patient survival

To test whether different expression levels of NR4A1 influence a patient’s clinical outcome, in an independent cohort we analyzed the association of NR4A1 messenger RNA (mRNA) expression and clinical data of 82 histologically confirmed aggressive lymphoma patients, all receiving a rituximab-containing regimen, at the Division of Hematology, Medical University of Graz between 2000 and 2010 (with follow-up until August 2012; supplemental Table 2). The patients were further categorized as low- and high-expression groups by using the median value of NR4A1 expression. Cancer-specific survival was defined as the time in months from the date of diagnosis to cancer-related death. Patients’ cancer-specific survival was calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method, compared by the log-rank test. Backward stepwise multivariate Cox proportional analysis was performed to determine the influence of clinico-pathological variables, significantly associated with clinical outcome in univariate analysis of survival. Hazard ratios and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals were estimated from the Cox regression analysis. The assumption of proportional hazards was checked by log-minus-log plots and residual analysis using Schoenfeld plots. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Vector construction, lentiviral transduction, transient transfection, and silencing of NR4A1

Sequence-verified full-length PCR product, generated from peripheral blood B-cell complementary DNA using specific PCR primers (supplemental Table 1), was subcloned into the pTightTet-Off viral expression system (Clontech) for lentiviral transduction and into pEZ-M61 (Genecopoeia) for transient transfection.

For silencing NR4A1 or NR4A3, a specific NR4A1 short hairpin (sh) RNA (pLKO.1), a specific NR4A3 shRNA (pLKO.1), or a nonsilencing shRNA control (p-shRNA) lentiviral construct (Open Biosystems) was used.

Details on the generation of lentiviral vectors, transduction, NR4A1, and functional assays induction are provided in supplemental Methods.

Xenograft experiments

NOD/SCID/IL-2rγnull (NSG) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Thirteen male NSG mice received subcutaneous flank injections of 1 × 107 transduced SuDHL4 cells containing the empty pLVX-plasmid as vector control on the right flank and the inducible NR4A1 pLVX-construct on the left flank resuspended in 200 μL matrigel (BD Biosciences). Doxycycline (Clontech) was administered to 5 animals through their drinking water in a concentration of 200 µg/mL as controls. Tumor burden was assessed weekly by tentative inspection. At day 20, tumor volume was estimated by ultrasonic testing, and all tumors were harvested for histologic analysis. Tumor volume and histologic stains were compared between the doxycycline-administered mice and mice without doxycycline. All animal work was done in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Medical University of Graz.

Results

Reduced NR4A1 and NR4A3 expression inaggressive lymphomas

We examined the expression of NR4A1, NR4A2, and NR4A3 in 167 lymphoma cases consisting of indolent and aggressive lymphoid malignancies and in 18 nonneoplastic controls consisting of peripheral B and T cells, GCBs, MC-Bs, and hyperplastic lymph nodes (Table 1) by using RQ-PCR. If detectable, NR4A2 was not reduced to a significant extent (data not shown). NR4A1 and NR4A3 mRNA transcripts were detected in all analyzed specimens. The means of expression levels for each nuclear orphan receptor of the lymphoma entities with significantly reduced content are depicted in Figure 1A. In comparing the NR4A expression of each lymphoid malignancy to peripheral CD19+ cells, hyperplastic lymph nodes, or their cell of origin (MC-Bs for MCL, and GCBs for FLII + III, DLBCL, BL, PMBCL, and HD), significantly reduced NR4A1 and NR4A3 mRNA expression was detected in 2 of 8 indolent NHL entities (B-CLL and FLII) and in 3 of 5 aggressive NHL entities (DLBCL, FLIII, and PMBCL) (Figure 1A and Table 1, which contains only the comparison with GCB). The magnitude of reduction in NR4A1 and NR4A3 expression in high-grade lymphomas equaled those previously described for AML,8 suggesting a similar biological influence.

NR4A1 and NR4A3 expression in indolent and aggressive NHLs. (A) Depiction of NR4A1 and NR4A3 mRNA expression levels in indolent and aggressive NHL patients with reduced NR4A content and normal controls [reactive lymph nodes (LA), peripheral B-cells (CD19), and GCBs]. (B) Representative western blot analysis of NR4A1 and NR4A3 expression in peripheral B cells (B1-B4), DLBCL (DL1-12), and FLIII (FL1-12). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) western blot analysis served as a loading control. (C) Expression analysis of Fas-L, Trail, the 3 splice variants of BIM (BIM 1,6 and 9), and Puma as potential NR4A target genes in indolent and aggressive NHL patients with a reduced NR4A1 and NR4A3 content compared with GCBs and MC-Bs by RQ-PCR. (D) NR4A1 and NR4A3 expression in GCB-DLBCL, non–GCB-DLBCL, and FLIII by RQ-PCR. (E) Probability of cancer-specific survival in DLBCL patients stratified according to the NR4A1 mRNA expression level. Low NR4A1 expression is associated with poor survival. (F) Immunohistochemical analysis of NR4A1 in nonneoplastic lymph nodes (magnification ×200 for panel Fi, magnification ×400 for panel Fii), in GCB-DLBCL (magnification ×400 for panel Fiii), in non–GCB-DLBCL (magnification ×400 for panel Fiv), and in FLIII (magnification ×400 for panel Fv). Strong NR4A1 expression was found in almost all GCBs in nonneoplastic lymph nodes, whereas a weaker nuclear NR4A1 expression was detected in GCB-DLBCL and non–GCB-DLBCL and FLIII. All images were captured by using an Olympus BX51 microscope and an Olympus E-330 camera. mRNA expression levels were calculated as relative expression in comparison with peripheral mononucleated cells serving as a calibrator. Each bar represents the mean values of expression levels ± standard deviation (SD). The comparison of the expression levels was performed by using the Mann-Whitney U test; all significant associations were corrected for multiple testing by applying a Bonferroni correction. * indicates reduced expression compared with LA or CD19+ cells (P < .01); □, reduced expression compared with GCBs (P < .01); †, reduced expression compared with mantle cells (P < .01); Δ, reduced expression compared with GCB-DLBCL (P < .01); and ○, reduced expression compared with FLIII (P < .01). Number in or above columns indicates number of tested specimens.

NR4A1 and NR4A3 expression in indolent and aggressive NHLs. (A) Depiction of NR4A1 and NR4A3 mRNA expression levels in indolent and aggressive NHL patients with reduced NR4A content and normal controls [reactive lymph nodes (LA), peripheral B-cells (CD19), and GCBs]. (B) Representative western blot analysis of NR4A1 and NR4A3 expression in peripheral B cells (B1-B4), DLBCL (DL1-12), and FLIII (FL1-12). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) western blot analysis served as a loading control. (C) Expression analysis of Fas-L, Trail, the 3 splice variants of BIM (BIM 1,6 and 9), and Puma as potential NR4A target genes in indolent and aggressive NHL patients with a reduced NR4A1 and NR4A3 content compared with GCBs and MC-Bs by RQ-PCR. (D) NR4A1 and NR4A3 expression in GCB-DLBCL, non–GCB-DLBCL, and FLIII by RQ-PCR. (E) Probability of cancer-specific survival in DLBCL patients stratified according to the NR4A1 mRNA expression level. Low NR4A1 expression is associated with poor survival. (F) Immunohistochemical analysis of NR4A1 in nonneoplastic lymph nodes (magnification ×200 for panel Fi, magnification ×400 for panel Fii), in GCB-DLBCL (magnification ×400 for panel Fiii), in non–GCB-DLBCL (magnification ×400 for panel Fiv), and in FLIII (magnification ×400 for panel Fv). Strong NR4A1 expression was found in almost all GCBs in nonneoplastic lymph nodes, whereas a weaker nuclear NR4A1 expression was detected in GCB-DLBCL and non–GCB-DLBCL and FLIII. All images were captured by using an Olympus BX51 microscope and an Olympus E-330 camera. mRNA expression levels were calculated as relative expression in comparison with peripheral mononucleated cells serving as a calibrator. Each bar represents the mean values of expression levels ± standard deviation (SD). The comparison of the expression levels was performed by using the Mann-Whitney U test; all significant associations were corrected for multiple testing by applying a Bonferroni correction. * indicates reduced expression compared with LA or CD19+ cells (P < .01); □, reduced expression compared with GCBs (P < .01); †, reduced expression compared with mantle cells (P < .01); Δ, reduced expression compared with GCB-DLBCL (P < .01); and ○, reduced expression compared with FLIII (P < .01). Number in or above columns indicates number of tested specimens.

To determine whether reduced NR4A1 and NR4A3 mRNA expression translates to reduced protein levels, western blot analyses for NR4A1 and NR4A3 were performed in selected control samples (peripheral CD19+ B cells: B1-B4) and B-cell malignancies (DLBCL and FLIII, n = 12 each) (Figure 1B). Peripheral B cells and AML samples were included as positive and negative controls, respectively. In comparing densitometrically quantified protein levels to mRNA levels, a significant positive correlation for both factors was observed (Spearman ρ = 0.805 for NR4A1 and Spearman ρ = 0.565 for NR4A3, P < .01).

Reduced NR4A1 and NR4A3 expression is associated with diminished apoptotic signals

To gain knowledge of whether reduced NR4A1 and NR4A3 expression has an impact on potential NR4A downstream target genes, we analyzed the mRNA expression of Fas-L, TRAIL, Bim, and Puma, predicted targets of NR4A1 and NR4A3,15-17 exhibiting proapoptotic function, and their receptors (Fas,18 DR4, and DR519,20 ) and inhibitors (BCL2, BCLX, and MCL1). The expression of TRAIL, Puma, and Bim (isoforms 1,6 and 9) mRNA was significantly lower in the DLBCL and FLIII specimens and additionally in FLII and B-CLL specimens for Puma and Bim compared with GCB (Figure 1C). However, Fas-L, Fas, DR4 and DR5 BCL2, BCLX, and MCL1 levels remained unchanged (data not shown). Correlating the NR4A1 and NR4A3 mRNA levels to TRAIL, Puma, and Bim expression, a significant positive correlation was observed, suggesting that reduced NR4A1 and NR4A3 expression may result in a reduction of extrinsic and intrinsic apoptotic signals.

Low NR4A1 expression is associated with the non-GCB subtype and correlates with poor survival

Because aggressive B-cell lymphomas exhibited the lowest NR4A1 and NR4A3 expression levels, we decided to expand our analysis of mRNA expression levels of both receptors in an independent cohort of 82 patients diagnosed with DLBCL and FLIII at our institution. A marked (more than twofold) downregulation of both nuclear orphan receptors was detected in the vast majority of GCB-DLBCL, non–GCB-DLBCL, and FLIII patients, respectively. It is worth mentioning that NR4A1 was expressed 3.6- and 5.7-fold higher in GCB-DLBCL and in FLIII compared with the non-GCB subtype (Figure 1D, P = .021).

By dividing the patients into 2 groups using the median of their NR4A1 mRNA expression, a significant association between low NR4A1 expression and poor cancer-specific survival was observed (P = .042, log-rank test, Figure 1E). Supplemental Figure 1 shows the survival curves for the GCB and non-GCB patients (P < .001, log-rank test). Given the significant association between the low NR4A1 expression and the non-GCB group, we evaluated whether the NR4A1 expression value represents a novel prognostic marker using a multivariate analysis. However, in multivariate analysis the tumor stage and the cell of origin subtype were confirmed as poor prognostic factors, whereas the NR4A1 expression did not prove to be regarded as an independent prognostic factor (supplemental Table 3). No association between NR4A3 expression and overall survival or relapse-free survival was observed. Therefore, we proceeded with NR4A1 for further functional characterization.

Immunohistochemical analysis of NR4A1 correlated to its mRNA expression in nonneoplastic lymph nodes (n = 5) and in selected lymphoma specimens (n = 59, Spearman ρ = 0.758, P < .01) confirming that reduced mRNA expression translates to reduced protein levels in the investigated cohort. Notably, almost all GCBs in nonneoplastic lymph nodes (Figure 1Fi-ii) exhibited a strong nuclear NR4A1 expression, whereas aggressive lymphoma cells showed a weaker nuclear reactivity for NR4A1 in the range from 5% to 60% (Figure 1Fiii-v).

To confirm the results of NR4A1 expression and patient survival in a public data set, we used the microarray data (GSE108464) published by Lenz et al21 of patients treated with R-CHOP (addition of Rituximab [monoclonal CD20 antibody] to CHOP regimen) (n = 200) classified in ABC-DLBCL and GCB-DLBCL. The mean of the expression values of all features representing NR4A1 was computed, and the DLBCL patients were divided into 2 groups (low and high NR4A1 expressing) using the median of NR4A1 expression. In concordance with our RQ-PCR analysis, a significant association between low NR4A1 expression and poor cancer-specific survival was observed (supplemental Figure 2, P = .0492, log-rank test). In contrast to our cohort, the distribution of cell of origin (ABC vs GCB) and the level of NR4A1 expression did not coincide with each other (P = .0886), suggesting that NR4A1 is an independent prognostic parameter.

NR4A1 is somatically unmutated in aggressive lymphomas

Possible causes for lymphoma-related downregulation of NR4As might be mutations or deletions at their loci, microRNA (miRNA)–mediated regulation, and promoter hypermethylation. To investigate whether deletions or mutations in the promoter (1 kb upstream and downstream of the transcriptional initiation site) or coding sequence (CDS) occur, direct sequencing and gene copy number analyses of NR4A1 and NR4A3 in the lymphoma entities (4 B-CLL, 5 FLII, 10 GCB-DLBCL, 14 non–GCB-DLBCL, 14 FLIII, 5 ALL, and 4 AML) and in controls (n = 20) were performed. Besides some already described single-nucleotide polymorphisms derived from publicly available databases (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp) in both receptors (supplemental Table 1), 10 of 39 aggressive NHLs exhibited novel, silent single base pair substitutions in the CDS of NR4A1, namely c.15 G>A (3 FLIII and 4 non–GCB-DLBCL) and c.297 C>T (1 FLIII and 2 GCB-DLBCL) (supplemental Table 4). Further, 1 aggressive NHL specimen (1 DLBCL-GCB) exhibited a novel intronic base pair substitution in the NR4A1 locus (supplemental Table 4). To clarify whether the most frequent single base pair substitution, c.15 G>A, was of germ line origin, nonneoplastic tissue of all 7 mutated aggressive lymphoma patients was sequenced and demonstrated its germ line origin in all instances.

To clarify whether particular miRNAs might be involved in the downregulation of NR4A1 and NR4A3 in lymphoma cells by direct interaction on their 3′ untranslated region, we performed an in silico search for putative potential interacting miRNA binding sites that may inhibit protein translation or increasing mRNA degradation by using the bioinformatic predictive tool miRGen (http://www.diana.pcbi.upenn.edu/cgi-bin/miRGen/v3/Targets.cgi). We selected 13 miRNAs to analyze in a training set consisting of 10 lymphoma cases and 4 normal B-cell samples. Mir-15b_2, miR-98, miR-199a_1, and miR-497_1 showed at least twofold higher expression levels in lymphoma cells compared with normal B cells (P < .05, data not shown). Furthermore, the expression levels of these 4 miRNAs were determined in our cohort of aggressive B-cell lymphomas (n = 75) and germinal B cells (n = 5), but no inverse correlation to NR4A1 expression could be observed. Additionally, based on the miRNA expression data set of Jima et al,22 potential miRNAs with putative binding sites in the 3′ untranslated region of NR4A1 interacting miRNA (miR-16_1, mir16miR-16_2, miR-27a*, mir103miR-103_1, mir103miR-103_2, and mir185miR-185) were identified by using 10 publicly available prediction tool algorithms (DIANAmT, MiRanda, MirRDB, miRWalk, RNA hybrid, PICTAR4, PICTAR5, PITA, RNA22, and Target Scan). All of these miRNAs were expressed at least fourfold higher in lymphoma specimens compared with GCBs (P < .05, data not shown), but no inverse correlation to NR4A1 expression was detected.

In addition, no deletions or promoter hypermethylation in cytosine guanine dinucleotide islands of both NR4As could be detected by using methylation-specific PCR. Local deep bisulfite sequencing23 for the NR4A1 promoter confirmed the results obtained by methylation-specific PCR (supplemental Figure 3), pointing to transcriptional regulation independent of DNA methylation events.

Overexpression of NR4A1 causes apoptosis in aggressive lymphoma cells and upregulation of Bim, Puma, and Trail

To functionally characterize NR4A1, the SuDHL4 lymphoma cell line was stably transduced with an inducible lentiviral construct (pTight Tet-Off viral expression system, Clontech) carrying NR4A1. The transduction was performed in 3 replicates named SN1 I, SN1 II, and SN1 III. Transduction with the viral vector without insert, named Splvx, served as vector control. The removal of doxycycline from the culture medium led to an ∼17-fold NR4A1 induction, whereas in Splvx NR4A1 levels remained unchanged (Figure 2A,C; supplemental Figure 4). NR4A1 overexpression led to a 3.7-fold induction of caspase 3/7 activity after 72 hours (Figure 2C) and a 50% reduction in cell growth as demonstrated by the MTS [3-(4,5 dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium] assay after 72 hours (Figure 2D). After 48 hours and 72 hours of doxycyline removal, a higher proportion of NR4A1-expressing SuDHL4 lymphoma cells exhibited cleaved caspase 3 (20.8% vs 7.2%, Figure 2E; P < .001) and a significantly higher SubG1 peak compared with their vector controls (44.7% vs 4.4%, Figure 2F; P = .007). Additionally, the positivity for annexin V was significantly increased by induction of NR4A1 (38.9% vs 4.3%, Figure 2H; P = .009). Together, these results suggest a proapoptotic effect of NR4A1 in lymphoma cell lines. To further investigate the apoptotic effect of NR4A1 in SuDHL4 lymphoma cells, we analyzed the mRNA expression of Fas-L, TRAIL, Bim, and Puma, predicted targets of NR4A1,15-17 and their receptors (Fas, DR4, and DR5) and inhibitors (BCL2, BCLX, and MCL1) 48 hours after NR4A1 induction. Whereas Fas, DR4, DR5, BCL2, BCLX, and MCL1 mRNA expression remained unchanged and no mRNA transcripts for Fas-L and isoform 9 of Bim were detectable, TRAIL, isoform 1 and 6 of Bim, and Puma were significantly upregulated (Figure 2G, P < .001). Comparing the induction of these apoptotic genes to NR4A1 content, a significant positive correlation was observed (Spearman ρ = 0.86, 0.84, and 0.85 for TRAIL, Bim1,6, and Puma; P < .002), suggesting that NR4A1 functions as a transcriptional activator, acting on genes responsible for the induction of apoptosis in lymphoma cells.

Functional characterization of NR4A1 in SuDHL4 lymphoma cells. Transduced SuDHL4 cells carrying empty vector (SpLVX) or the inducible NR4A1 construct (SN1 I-III) were cultured in the presence of doxycycline (DOX), no NR4A1 induction, or absence of doxycycline (No DOX), induction of NR4A1. (A) NR4A1 mRNA expression analysis after induction. Relative expression levels were calculated in comparison with Splvx cultured with doxycycline-containing media. Each bar represents the mean values of expression levels ± SD. * indicates a significant induction of NR4A1 compared with vector control and uninduced counterpart (P < .01). (B) Western blot analysis of NR4A1 expression with and without its induction in SuDHL4 carrying the inducible NR4A1 construct. GAPDH served as loading control. (C-F, H) Apoptotic and cell growth assay of transduced SuDHL4 carrying the empty vector (Splvx) or the inducible NR4A1 construct SuDHL4 (SN1 I-III) with and without doxycycline. To determine the apoptotic effects of NR4A1 in aggressive lymphoma cells, caspase 3/7 activity (C), caspase 3 cleavage (E), SubG1 peak (F), and annexin V (H) were estimated. Furthermore, cell growth analysis was performed by employing MTS assays (D). The caspase 3/7 activity and the MTS were calculated in comparison with Splvx lymphoma cells cultured with doxycycline-containing media. Annexin V staining and cleaved caspase 3 percentage were estimated by using fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis with specific fluorophore-labeled peptides or antibodies. SubG1 peaks were determined by cell cycle analysis using FACS analysis. * indicates significantly higher apoptotic activity or reduced cell growth compared with vector control and uninduced counterpart (P < .01). (G) mRNA expression levels of potential NR4A target genes of transduced SuDHL4 carrying the empty vector (Splvx) or the inducible NR4A1 construct (SN1 I-III) with and without doxycycline. * indicates significantly higher induction of TRAIL, BIM 1,6, and Puma to vector control and uninduced counterpart (P < .01). (I) Visual inspection of SuDHL4 lymphoma formation with an inducible NR4A1 construct (left flank) and vector controls (right flank) with and without doxycycline administration in the NSG xenograft model after 20 days. (J) Macroscopic analysis of tumors from SuDHL4 lymphoma cells carrying the inducible NR4A1 construct (left flank) and empty vector (right flank) with and without doxycycline administration after 20 days. (K) Estimation of tumor volume by using an ultrasonic device after 20 days. * indicates significant induction of NR4A1 compared with vector control and uninduced counterpart (P < .01). (L) Histologic analysis of tumors from SuDHL4 lymphoma cells carrying empty vector (upper row) or the inducible NR4A1 construct (lower row) and with (left column) and without doxycycline (right column) administration after 20 days (magnification ×100).

Functional characterization of NR4A1 in SuDHL4 lymphoma cells. Transduced SuDHL4 cells carrying empty vector (SpLVX) or the inducible NR4A1 construct (SN1 I-III) were cultured in the presence of doxycycline (DOX), no NR4A1 induction, or absence of doxycycline (No DOX), induction of NR4A1. (A) NR4A1 mRNA expression analysis after induction. Relative expression levels were calculated in comparison with Splvx cultured with doxycycline-containing media. Each bar represents the mean values of expression levels ± SD. * indicates a significant induction of NR4A1 compared with vector control and uninduced counterpart (P < .01). (B) Western blot analysis of NR4A1 expression with and without its induction in SuDHL4 carrying the inducible NR4A1 construct. GAPDH served as loading control. (C-F, H) Apoptotic and cell growth assay of transduced SuDHL4 carrying the empty vector (Splvx) or the inducible NR4A1 construct SuDHL4 (SN1 I-III) with and without doxycycline. To determine the apoptotic effects of NR4A1 in aggressive lymphoma cells, caspase 3/7 activity (C), caspase 3 cleavage (E), SubG1 peak (F), and annexin V (H) were estimated. Furthermore, cell growth analysis was performed by employing MTS assays (D). The caspase 3/7 activity and the MTS were calculated in comparison with Splvx lymphoma cells cultured with doxycycline-containing media. Annexin V staining and cleaved caspase 3 percentage were estimated by using fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis with specific fluorophore-labeled peptides or antibodies. SubG1 peaks were determined by cell cycle analysis using FACS analysis. * indicates significantly higher apoptotic activity or reduced cell growth compared with vector control and uninduced counterpart (P < .01). (G) mRNA expression levels of potential NR4A target genes of transduced SuDHL4 carrying the empty vector (Splvx) or the inducible NR4A1 construct (SN1 I-III) with and without doxycycline. * indicates significantly higher induction of TRAIL, BIM 1,6, and Puma to vector control and uninduced counterpart (P < .01). (I) Visual inspection of SuDHL4 lymphoma formation with an inducible NR4A1 construct (left flank) and vector controls (right flank) with and without doxycycline administration in the NSG xenograft model after 20 days. (J) Macroscopic analysis of tumors from SuDHL4 lymphoma cells carrying the inducible NR4A1 construct (left flank) and empty vector (right flank) with and without doxycycline administration after 20 days. (K) Estimation of tumor volume by using an ultrasonic device after 20 days. * indicates significant induction of NR4A1 compared with vector control and uninduced counterpart (P < .01). (L) Histologic analysis of tumors from SuDHL4 lymphoma cells carrying empty vector (upper row) or the inducible NR4A1 construct (lower row) and with (left column) and without doxycycline (right column) administration after 20 days (magnification ×100).

Additionally, to investigate the function of NR4A1 in other cell lines, SuDHL4 and Karpas422 as GCB-DLBCL lymphoma cell lines and RI-1 and U2932 as ABC-DLBCL lymphoma cell lines were transiently transfected with the pEZ-M61 carrying NR4A1 by using the AMAXA nucleofection system. After transfection, NR4A1 was at least 19-fold overexpressed in all cell lines (SuDHL4, ∼19×; Karpas422, ∼30×; RI-1, ∼23×; and U2932, ∼19×) compared with their vector controls (Figure 3A). Overexpression of NR4A1 caused an ∼60% reduction in cell growth as demonstrated by the MTS assay after 72 hours (P < .01; Figure 3B) and a marked increased annexin V positivity after 48 hours for all cell lines (52.3% vs 5.2% for SuDHL4, 66.8% vs 6.8% for Karpas422, 61.9% vs 4.1% for RI-1, and 64.8% vs 5.0% for U2932; Figure 3C). Additionally, a higher caspase 3/7 activity was observed in all lymphoma cell lines overexpressing NR4A1 after 48 hours (3.8-fold for SuDHL4, 3.2-fold for Karpas422, 3.7-fold for RI-1, and 3.9-fold for U2932; Figure 3D). Again confirming our findings in lentivirally transduced SuDHL4, expression analysis of potential NR4A1 target genes (Fas-L, TRAIL, Bim, and Puma) demonstrated that NR4A1 overexpression caused a strong induction of isoform 1 and 6 of Bim, Puma, and TRAIL (Figure 3E), whereas expression levels of their inhibitors (BCL2, BCLX, and MCL1) and their receptors (Fas, DR4, and DR5) remained unchanged after 48 hours (data not shown). Comparing the levels of these apoptotic genes to NR4A1 content, a significant positive correlation was observed (Spearman ρ = 0.758, 0.771, and 0.695 for Bim1,6, Puma, and TRAIL; P < .001 for all 3 genes), suggesting that NR4A1 regulates genes responsible for apoptosis induction in GCB-DLBCL and ABC-DLBCL lymphoma cells.

Induction of apoptosis by NR4A1 in GCB and ABC lymphoma cell lines. SuDHL4 and Karpas422 (Karpas) (GCB origin), and RI-1 and U2932 (ABC origin) lymphoma cells were transfected with empty pEZ-M61 vector (pEZ-M61-empty) or pEZ-M61 carrying the NR4A1 construct. (A) NR4A1 mRNA expression after NR4A1 transfection. Relative expression levels were in comparison with empty vector controls. Each bar represents the mean values of expression levels ± SD. (B-D). Apoptotic and cell growth assays of all 4 transfected lymphoma cell lines carrying the empty vector or the NR4A1 construct: cell growth analysis was performed by employing MTS assays (B). To evaluate the apoptotic effects of NR4A1 in aggressive lymphoma cells, Annexin V, by using the FACS methods with specific fluorophore-labeled peptides (C), and caspase 3/7 activity (D) were estimated. (E) mRNA expression levels of potential NR4A target genes of NR4A1 overexpressing lymphoma cells.

Induction of apoptosis by NR4A1 in GCB and ABC lymphoma cell lines. SuDHL4 and Karpas422 (Karpas) (GCB origin), and RI-1 and U2932 (ABC origin) lymphoma cells were transfected with empty pEZ-M61 vector (pEZ-M61-empty) or pEZ-M61 carrying the NR4A1 construct. (A) NR4A1 mRNA expression after NR4A1 transfection. Relative expression levels were in comparison with empty vector controls. Each bar represents the mean values of expression levels ± SD. (B-D). Apoptotic and cell growth assays of all 4 transfected lymphoma cell lines carrying the empty vector or the NR4A1 construct: cell growth analysis was performed by employing MTS assays (B). To evaluate the apoptotic effects of NR4A1 in aggressive lymphoma cells, Annexin V, by using the FACS methods with specific fluorophore-labeled peptides (C), and caspase 3/7 activity (D) were estimated. (E) mRNA expression levels of potential NR4A target genes of NR4A1 overexpressing lymphoma cells.

Overexpression of NR4A1 suppresses tumor growth in an NSG mouse model

To test the tumor suppressor function of NR4A1 in vivo, the stably transduced SuDHL4 lymphoma cell lines were further investigated in the NSG mouse model. This xenograft model was chosen because it is among the most immunodeficient strains of inbred laboratory mice described to date.24 Control cells (Splvx containing no insert) were subcutaneously injected in the right flank, and the same number of SN1 III lymphoma cells, exhibiting the highest NR4A1 expression (supplemental Figure 1), in the left flank of (n = 13) male NSG mice. Eight of 13 mice did not achieve any doxycycline to induce NR4A1 expression, whereas doxycycline was administered to the residual 5 mice to suppress NR4A1 expression. Within 14 days, all mice developed visible tumors in their right flanks, whereas tumors in the left flanks were only detected in the doxycycline-administered mice (Figure 2I). The generated tumors expressed all markers for B-cell lymphomas (supplemental Figure 5). Macroscopic inspection (Figure 2J) showed a clear size difference: mice inoculated with SN1 III cells without doxycycline developed no lymphoma compared with doxycycline-administered mice or mice inoculated with the same cell line carrying the empty vector (Figure 2K). Histologic analysis also demonstrated that only mice without doxycycline from SN1 III lymphoma cells remained tumor free (Figure 2L). Together, these data define NR4A1 as a novel tumor suppressor in aggressive lymphoma.

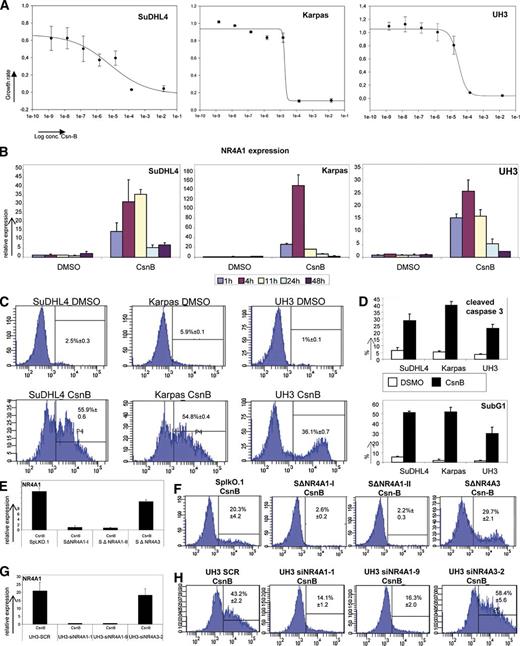

Treatment of lymphoma cell lines and immortalized B cells with CsnB induces NR4A1-mediated apoptosis

To investigate whether the known NR4A1 ligand CsnB is able to induce NR4A1 expression10 in lymphomas, we treated an immortalized B-cell line (UH3) and 2 lymphoma cell lines (SuDHL4 and Karpas422) with CsnB and performed MTS assays. After 72 hours of CsnB treatment, a concentration-dependent growth inhibition in all 2 investigated cell lines and immortalized B cells was detected (Figure 4A). NR4A1 expression was induced through treatment with 1.0 × 10−5 M CsnB in the 2 lymphoma cell lines and the immortalized B cells (Figure 4B). In order to find out whether CsnB-induced growth inhibition is mediated by apoptosis, we determined the cleavage of caspase 3, the Sub-G1 peak, and the positivity for annexin V. After 24 hours of treatment, CsnB led to a significantly higher number of annexin V–positive cells compared with their untreated controls (Figure 4C). Additionally, cleaved caspase 3 was also detected in a markedly higher fraction of lymphoma cells compared with their untreated controls (Figure 4D). Finally, to investigate whether the observed apoptotic effects are specific to CsnB action via induction of NR4A1 and NR4A3, shRNA and short interfering RNA (siRNA) silencing was performed in SuDHL4 and in immortalized B cells (UH3 cell line). Silencing of NR4A1, but not of NR4A3, entirely abrogated the apoptotic effects of CsnB (Figure 4E-F, for SuDHL4; Figure 4G-H, for UH3), indicating that the apoptotic effects of CsnB are specifically mediated by NR4A1.

Determination of CsnB effects on aggressive lymphoma cell lines. (A) Estimation of cell growth by MTS assay of SuDHL4, Karpas422, and UH3 72 hours after CsnB treatment in a range from 2.5 × 10−3 to 5 × 10−9 M. Cell growth was estimated by using the MTS assay in comparison with each cell line treated with dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) as vehicle control. (B) NR4A1 mRNA expression analysis in SuDHL4, Karpas422, and UH3 after treatment with 10 µM CsnB or DMSO. Relative expression levels were calculated in comparison with each cell line treated with DMSO as vehicle control. Each bar represents the mean values of expression levels ± SD. (C-D) Apoptosis assays of SuDHL4, Karpas422, and UH3 24 hours after 10 µM DMSO or CsnB treatment. To determine apoptotic effects of CsnB, annexin V (C) staining and estimation of the percentage of cleaved caspase 3 by using FACS analysis with specific fluorophore-labeled peptides or antibodies and SubG1 peak (D) determination by using FACS analysis for cell cycle distribution were performed. Each bar represents the mean values of expression levels ± SD for analyses for cleaved caspase 3 and SubG1 peak. (E) NR4A1 mRNA expression analysis of NR4A1 and NR4A3 silenced SuDHL4 lymphoma cells and vector control 24 hours after 10 µM CsnB treatment. Relative expression levels were calculated in comparison of SpLKO.1 treated with DMSO as vehicle control. The 2 replicates of NR4A1-silenced SuDHL4 cells were termed SΔNR4A1-I and SΔNR4A1-II; the NR4A3-silenced SuDHL4 cells, SΔNR4A3; and SuDHL4 just containing the empty vector, SpLKO.1. Each bar represents the mean values of expression levels ± SD. (F) Annexin V staining of SuDHL4 lymphoma cells NR4A1 silenced by shRNA or SuDHL4 lymphoma cells NR4A3 silenced by shRNA and vector control 24 hours after CsnB treatment. Annexin V staining was performed by using FACS analysis with specific fluorophore-labeled peptides. The 2 replicates of NR4A1 (SΔNR4A1-I and SΔNR4A1-II) and of NR4A3 (SΔNR4A3) were silenced in SuDHL4 cells. SpLKO.1 contains the empty vector. (G) NR4A1 mRNA expression analysis of NR4A1 and NR4A3 silenced in UH3 immortalized B cells and scrambled controls (UH3 SCR) 24 hours after 10 µM CsnB treatment. Relative expression levels were calculated in comparison of UH3 SCR treated with DMSO as vehicle control. UH3 cells transfected with 2 different siRNAs targeting NR4A1 were termed UH3-siNR4A1-1 and UH3-siNR4A1-9. The siRNA targeting NR4A3 was termed UH3-siNR4A3-2. Each bar represents the mean values of expression levels ± SD. (H) Annexin V staining of UH3 cells silenced by siRNA targeting NR4A1 or NR4A3 and scrambled control 24 hours after CsnB treatment. Annexin V staining was performed by using FACS analysis with specific fluorophore-labeled peptides.

Determination of CsnB effects on aggressive lymphoma cell lines. (A) Estimation of cell growth by MTS assay of SuDHL4, Karpas422, and UH3 72 hours after CsnB treatment in a range from 2.5 × 10−3 to 5 × 10−9 M. Cell growth was estimated by using the MTS assay in comparison with each cell line treated with dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) as vehicle control. (B) NR4A1 mRNA expression analysis in SuDHL4, Karpas422, and UH3 after treatment with 10 µM CsnB or DMSO. Relative expression levels were calculated in comparison with each cell line treated with DMSO as vehicle control. Each bar represents the mean values of expression levels ± SD. (C-D) Apoptosis assays of SuDHL4, Karpas422, and UH3 24 hours after 10 µM DMSO or CsnB treatment. To determine apoptotic effects of CsnB, annexin V (C) staining and estimation of the percentage of cleaved caspase 3 by using FACS analysis with specific fluorophore-labeled peptides or antibodies and SubG1 peak (D) determination by using FACS analysis for cell cycle distribution were performed. Each bar represents the mean values of expression levels ± SD for analyses for cleaved caspase 3 and SubG1 peak. (E) NR4A1 mRNA expression analysis of NR4A1 and NR4A3 silenced SuDHL4 lymphoma cells and vector control 24 hours after 10 µM CsnB treatment. Relative expression levels were calculated in comparison of SpLKO.1 treated with DMSO as vehicle control. The 2 replicates of NR4A1-silenced SuDHL4 cells were termed SΔNR4A1-I and SΔNR4A1-II; the NR4A3-silenced SuDHL4 cells, SΔNR4A3; and SuDHL4 just containing the empty vector, SpLKO.1. Each bar represents the mean values of expression levels ± SD. (F) Annexin V staining of SuDHL4 lymphoma cells NR4A1 silenced by shRNA or SuDHL4 lymphoma cells NR4A3 silenced by shRNA and vector control 24 hours after CsnB treatment. Annexin V staining was performed by using FACS analysis with specific fluorophore-labeled peptides. The 2 replicates of NR4A1 (SΔNR4A1-I and SΔNR4A1-II) and of NR4A3 (SΔNR4A3) were silenced in SuDHL4 cells. SpLKO.1 contains the empty vector. (G) NR4A1 mRNA expression analysis of NR4A1 and NR4A3 silenced in UH3 immortalized B cells and scrambled controls (UH3 SCR) 24 hours after 10 µM CsnB treatment. Relative expression levels were calculated in comparison of UH3 SCR treated with DMSO as vehicle control. UH3 cells transfected with 2 different siRNAs targeting NR4A1 were termed UH3-siNR4A1-1 and UH3-siNR4A1-9. The siRNA targeting NR4A3 was termed UH3-siNR4A3-2. Each bar represents the mean values of expression levels ± SD. (H) Annexin V staining of UH3 cells silenced by siRNA targeting NR4A1 or NR4A3 and scrambled control 24 hours after CsnB treatment. Annexin V staining was performed by using FACS analysis with specific fluorophore-labeled peptides.

Discussion

This study was designed to investigate the expression and function of the NR4A nuclear orphan receptors in the most common types of indolent and aggressive lymphomas. Although there is growing evidence that all 3 members of the NR4As play an important role in human tumorigenesis,5 data regarding lymphoma development are scarce. We observed reduced expression of NR4A1 and NR4A3 at mRNA and protein levels in FLII, B-CLL, DLBCL, FLIII, and PMBCL. NR4A1 and NR4A3 mRNA expression was also reduced in publicly available mRNA data sets of global gene expression profiling experiments derived from different B-cell lymphomas25-31 in FL and DLBCL, pointing to a tumor suppressive function of both NR4As in certain lymphoma subtypes.

For NR4A1 and NR4A3, a proapoptotic function has been described in various cancer types.5 Although NR4A1 target genes are poorly characterized, it is assumed that the proapoptotic effect of NR4A1 is achieved by its transactivation function acting as transcription factor of genes responsible for inducing apoptosis.15,32-34 Consequently, we found members of the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways TRAIL, Puma, and all isoforms of Bim, which represent already identified or potential targets of NR4A1 in the NR4A1 transgenic mouse model,16,17 with significantly lower expression. This suggests a reduced apoptotic signaling through reduction of NR4A expression in our primary lymphoma samples.

In our cohort of aggressive B-cell lymphomas, low NR4A1 expression was associated with reduced cancer-specific survival and non-GCB subtype. In contrast, by reanalyzing the largest publicly available gene expression profile data set of Lenz et al,21 NR4A1 expression even proved to be an independent prognostic factor for survival. The smaller number of patients and the higher proportion of patients with transformed follicular lymphomas in our cohort might account for this difference. Several studies applying gene expression analyses of cancer cell lines treated with chemo-immunotherapy including rituximab and doxorubicin suggest that NR4A1 expression is required for their antitumoral effects35-37 and that this NR4A1-mediated therapeutic effect influences survival.

Our gene copy number and DNA methylation analyses on the CDS and the regulatory regions of NR4A1 and NR4A3 did not provide any alterations. Furthermore, our analysis on miRNAs with potential to directly target NR4A1 and/or NR4A3 has not revealed an miRNA-target gene combination with inverse expression. Thus, a genome-wide miRNA profiling approach followed by in silico target prediction would more precisely delineate the causative role in NR4A1 downregulation.

Our sequence analysis of the CDS of NR4A1 resulted in silent mutation in 10 of 39 aggressive NHLs specimens. Direct sequencing of nonneoplastic tissue showed that the most frequent base pair substitutions were of germ line origin. Publicly available data on mutations present in DLBCL38-41 support our observation that NR4A1 is not somatically mutated by amino acid substitutions.

Because of the fact that NR4A1 is regulated by MEF2B,42 which is commonly mutated in aggressive lymphomas,39 it might be speculated that MEF2B mutations might be the genetic events causing NR4A1 downregulation.

Our in vitro experiment showed that NR4A1 reexpression led to the induction of apoptosis in aggressive lymphoma cells. Likewise, our NSG mouse model experiments demonstrated that NR4A1 induction completely prevented lymphoma formation. The proapoptotic effect of NR4A1 can be achieved by transactivating its target genes responsible for apoptosis, like Fas-L and TRAIL,15 or by “mitochondrial targeting,” a process in which NR4A1 translocates to the hydrophobic groove of mitochondria leading to BCL2 rearrangement and ultimately to cytochrome C release and apoptosis.43,44 Recently, a novel mechanism has been identified whereby NR4A1 transcriptionally suppresses MYC by occupying its promoter.45 Because TRAIL, Bim, and Puma were upregulated and MYC expression remained unchanged by NR4A1 induction in SuDHL4 cells (data not shown), we speculate that the proapoptotic effects of NR4A1 are achieved by the transaction of its proapoptotic target genes.

A recent publication demonstrated that CsnB, a known binding agonist of NR4A1,10 induces transactivational activity of NR4A1 on its target genes, including a feedback loop on the NR4A1 gene itself, which contains multiple consensus response elements suggestive of a positive autoregulation.10 By treating aggressive lymphoma cell lines with CsnB, we were able to induce an NR4A1-dependent apoptosis. Silencing NR4A1 by shRNA entirely reversed the apoptotic phenotype substantiating the central role of NR4A1 in lymphomagenesis. Because NR4A3 has been shown to be functionally redundant with NR4A1 in T-cell apoptosis and the tissue expression pattern of NR4A3 is similar to that of NR4A1, a redundancy of both is discussed.46 However, in our experiments, the apoptotic effects of CsnB were not influenced by silencing NR4A3, suggesting that in lymphomas CsnB works specifically through NR4A1.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the reduction of NR4A1 and NR4A3 is a common event in certain subtypes of aggressive NHLs, especially in DLBCL and FLIII. Low NR4A1 expression correlates with the non-GCB subtype and is associated with poor overall survival. Additionally, our in vitro and xenograft experiments indicate that NR4A1 acts as a novel tumor suppressor in lymphoma cells and that CsnB induces NR4A1-mediated apoptosis. Hence, the regulation of NR4A1 by agonists is a promising novel target for the development of new therapeutic drugs.

Presented in abstract form at the 54th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Atlanta, GA, December 2012.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Fellinger Krebsforschung, Land Steiermark, Hygienefond, and Jubiläumsfond der ÖNB (N11181) and by the START-Funding-Program of the Medical University of Graz and the city of Graz (A.J.A.D.).

Authorship

Contribution: A.J.A.D. designed the project, performed most of the experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; P.N. designed the project and wrote the manuscript; K.W., B.R., and A.J.A.D. performed most of the in vitro assays and xenograft experiments; K.W. and K.T. sequenced NR4A1 and NR4A3 in all lymphoma specimens; A.P. and A.K. participated in the cloning procedure of NR4A1 and helped to revise the manuscript; S.R. collected clinical data of the aggressive lymphoma cohort; M.P. performed the statistics; P.N. and H.S. supervised the whole project; C.B.-S. rediagnosed, selected all specimens, and performed immunohistochemical analysis; E.S. performed immunohistochemistry for NR4A1; K.T. and D.S. performed miRNA expression profiling under supervision from M.S. and M.P.; J.F. and G.G.T. performed the analysis of publicly available gene expression data; and S.T. performed bisulfite profiling of the NR4A1 cytosine guanine dinucleotide island.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Peter Neumeister, Medical University Graz, Auenbruggerplatz 38, A-8036 Graz, Austria; e-mail: peter.neumeister@medunigraz.at.

![Figure 1. NR4A1 and NR4A3 expression in indolent and aggressive NHLs. (A) Depiction of NR4A1 and NR4A3 mRNA expression levels in indolent and aggressive NHL patients with reduced NR4A content and normal controls [reactive lymph nodes (LA), peripheral B-cells (CD19), and GCBs]. (B) Representative western blot analysis of NR4A1 and NR4A3 expression in peripheral B cells (B1-B4), DLBCL (DL1-12), and FLIII (FL1-12). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) western blot analysis served as a loading control. (C) Expression analysis of Fas-L, Trail, the 3 splice variants of BIM (BIM 1,6 and 9), and Puma as potential NR4A target genes in indolent and aggressive NHL patients with a reduced NR4A1 and NR4A3 content compared with GCBs and MC-Bs by RQ-PCR. (D) NR4A1 and NR4A3 expression in GCB-DLBCL, non–GCB-DLBCL, and FLIII by RQ-PCR. (E) Probability of cancer-specific survival in DLBCL patients stratified according to the NR4A1 mRNA expression level. Low NR4A1 expression is associated with poor survival. (F) Immunohistochemical analysis of NR4A1 in nonneoplastic lymph nodes (magnification ×200 for panel Fi, magnification ×400 for panel Fii), in GCB-DLBCL (magnification ×400 for panel Fiii), in non–GCB-DLBCL (magnification ×400 for panel Fiv), and in FLIII (magnification ×400 for panel Fv). Strong NR4A1 expression was found in almost all GCBs in nonneoplastic lymph nodes, whereas a weaker nuclear NR4A1 expression was detected in GCB-DLBCL and non–GCB-DLBCL and FLIII. All images were captured by using an Olympus BX51 microscope and an Olympus E-330 camera. mRNA expression levels were calculated as relative expression in comparison with peripheral mononucleated cells serving as a calibrator. Each bar represents the mean values of expression levels ± standard deviation (SD). The comparison of the expression levels was performed by using the Mann-Whitney U test; all significant associations were corrected for multiple testing by applying a Bonferroni correction. * indicates reduced expression compared with LA or CD19+ cells (P < .01); □, reduced expression compared with GCBs (P < .01); †, reduced expression compared with mantle cells (P < .01); Δ, reduced expression compared with GCB-DLBCL (P < .01); and ○, reduced expression compared with FLIII (P < .01). Number in or above columns indicates number of tested specimens.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/123/15/10.1182_blood-2013-08-518878/4/m_2367f1.jpeg?Expires=1765887912&Signature=Iz4gPDeKAMV~GnZMsiNd1WQZJgeFGbdcywe0kkHR1bQQ2RkzraL-QY76nLycjCeNuGkGkGRRpWzvJtI6Jh9wagIW4cLhzGLC9yl5K8dLI~EtiDex9XTsP0HX1Li-evjEKjcATBZaCsDC1SkB~Isinh4yMxgUsdFVY06gbS~SvnDxkeNlNajMAATsScOH0V~WpJpmsLS~jjpO0ndCc2yOkScVKjqxwDH0sz-8aZH62Yfkmcg45l3i2hrpP0MUegaIKjTn7Ge6l~QqN0brBdB4y-Ch3YHloD8N0Ul3fGHXIikrbNFfTkkydn1t5KEHj-HidfwqPX1MLj6XZyrXP2ppqg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal