Key Points

Factor XII can contribute to thrombus formation in human and nonhuman primate blood.

An antibody that blocks factor XII activation (15H8) produces an antithrombotic effect in a primate thrombosis model.

The plasma zymogens factor XII (fXII) and factor XI (fXI) contribute to thrombosis in a variety of mouse models. These proteins serve a limited role in hemostasis, suggesting that antithrombotic therapies targeting them may be associated with low bleeding risks. Although there is substantial epidemiologic evidence supporting a role for fXI in human thrombosis, the situation is not as clear for fXII. We generated monoclonal antibodies (9A2 and 15H8) against the human fXII heavy chain that interfere with fXII conversion to the protease factor XIIa (fXIIa). The anti-fXII antibodies were tested in models in which anti-fXI antibodies are known to have antithrombotic effects. Both anti-fXII antibodies reduced fibrin formation in human blood perfused through collagen-coated tubes. fXII-deficient mice are resistant to ferric chloride–induced arterial thrombosis, and this resistance can be reversed by infusion of human fXII. 9A2 partially blocks, and 15H8 completely blocks, the prothrombotic effect of fXII in this model. 15H8 prolonged the activated partial thromboplastin time of baboon and human plasmas. 15H8 reduced fibrin formation in collagen-coated vascular grafts inserted into arteriovenous shunts in baboons, and reduced fibrin and platelet accumulation downstream of the graft. These findings support a role for fXII in thrombus formation in primates.

Introduction

There is considerable interest in the possibility that targeted inhibition of the plasma protease factor XIIa (fXIIa) and factor XIa (fXIa) may be useful for preventing or treating thrombosis.1,,,-5 Mice lacking factor XII (fXII) or factor XI (fXI), the zymogens of fXIIa and fXIa, respectively, are resistant to injury-induced arterial and venous thrombosis,6,,-9 and to ischemia-reperfusion injury in the brain10 and heart.11 fXI inhibition also reduces experimental thrombus formation in primates.8,12,13 Humans lacking fXII do not bleed abnormally,5,14 and fXI-deficient patients have a relatively mild bleeding disorder,14,15 raising the prospect that drugs targeting these proteins will produce antithrombotic effects without significantly compromising hemostasis. In the cascade/waterfall models of plasma coagulation, sequential proteolytic reactions initiated by conversion of fXII to fXIIa lead to thrombin generation and fibrin formation.16,17 fXIIa catalyzes conversion of fXI to fXIa during this process. Autoactivation of fXII in plasma is readily induced by adding minerals such as silica or kaolin that provide a surface on which the reaction occurs, and amplified by reciprocal activation of fXII and prekallikrein (PK) in a process called contact activation.4,14 In vivo, polymers such as collagen,18 laminin,19 RNA,20 DNA,21 and polyphosphate,9 as well as misfolded protein aggregates (such as occur in systemic amyloidosis),22 may facilitate fXII activation by similar processes, contributing to thrombosis. fXII may also be activated on membranes of vascular endothelial cells by a distinct mechanism initiated by prolylcarboxypeptidase-mediated conversion of PK to α-kallikrein.23,24

Consistent with data from mouse studies, there is substantial evidence supporting a role for fXI in arterial and venous thrombosis in humans.25,,,,-30 However, available data make a less compelling case for a role for fXII in human thrombosis. Indeed, 2 large surveys reported the counterintuitive observation that plasma fXII levels are inversely correlated with risk of myocardial infarction26 and death from all causes.31 This suggests that the contribution of fXII to thrombus formation observed in rodents may not reflect processes in humans. To address this issue, we developed monoclonal antibodies to human fXII that inhibit fXII activation, specifically to determine whether blocking fXII in a primate thrombosis model produces an antithrombotic effect similar to the reported effects of antibodies that block fXI.

Materials and methods

Proteins

Human fXII, fXIIa, PK, and high-molecular-weight kininogen (HK) were purchased from Enzyme Research Laboratories. Human fXI and fXIa were purchased from Haematologic Technologies.

Anti-fXII monoclonal antibodies

The murine fXII null genotype (C57Bl/6 background)7 was crossed onto the Balb-C background through 7 generations. fXII-deficient Balb-C mice were given 25 μg of a mixture of human fXII and fXIIa by intraperitoneal injection in Freund complete adjuvant on day 0 and Freund incomplete adjuvant on day 28. A 25-μg booster dose in saline was given on day 70. On day 73, spleens were removed and lymphocytes were fused with P3X63Ag8.653 myeloma cells using a standard polyethylene glycol–based protocol. Antibodies were tested for capacity to recognize human fXII by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and western blot, and to prolong the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) of human plasma. Clones 9A2 and 15H8 were subcloned, expanded in a CL1000 bioreactor (Integra Biosciences), and purified by cation exchange and thiophilic agarose chromatography.

Expression of recombinant fXII and antibody mapping

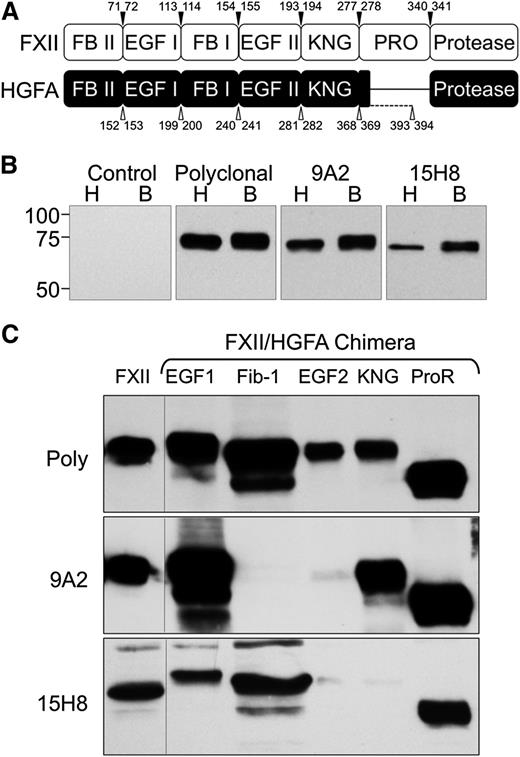

The human fXII complementary DNA (cDNA) was inserted into vector pJVCMV.32 Sequence encoding individual domains from the fXII homolog hepatocyte growth factor activator (HGFA) were amplified from the human HGFA cDNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR),33 and used to replace corresponding sequence in the fXII cDNA (Figure 1A and supplemental Tables 1-2, available on the Blood Web site). HEK293 fibroblasts (ATCC-CRL1573) were transfected with pJVCMV/fXII-HGFA constructs as described.32 Conditioned serum-free media (Cellgro Complete; Mediatech) from expressing clones were size-fractionated on 10% polyacrylamide–sodium dodecyl sulfate gels, and chemiluminescent western blots were prepared using 9A2, 15H8, or goat polyclonal–anti-human fXII immunoglobulin G (IgG) for detection.

Antibodies to human fXII. (A) Schematic diagrams comparing the domain structures of fXII and its homolog HGFA. Arrowed numbers indicate the locations of amino acid pairs that were used to create splice sites for introduction of HGFA domains into fXII to create fXII/HGFA chimeras. (B) Western blots of nonreduced human (H) and baboon (B) plasma size-fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-PAGE. The primary anti-factor XII antibodies used for detection are indicated at the top of each panel. (C) Western blots of wild-type human fXII (FXII) and human fXII with the first or second epidermal growth factor (EGF1 or EGF2), fibronectin type 1 (Fib-1), kringle (KNG), or proline-rich (ProR) domains replaced with the corresponding HGFA domain. Primary antibodies are indicated to the left of each blot. Poly, Polyclonal goat IgG against human fXII.

Antibodies to human fXII. (A) Schematic diagrams comparing the domain structures of fXII and its homolog HGFA. Arrowed numbers indicate the locations of amino acid pairs that were used to create splice sites for introduction of HGFA domains into fXII to create fXII/HGFA chimeras. (B) Western blots of nonreduced human (H) and baboon (B) plasma size-fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-PAGE. The primary anti-factor XII antibodies used for detection are indicated at the top of each panel. (C) Western blots of wild-type human fXII (FXII) and human fXII with the first or second epidermal growth factor (EGF1 or EGF2), fibronectin type 1 (Fib-1), kringle (KNG), or proline-rich (ProR) domains replaced with the corresponding HGFA domain. Primary antibodies are indicated to the left of each blot. Poly, Polyclonal goat IgG against human fXII.

Clotting assays

aPTT assays were performed by mixing 65 μL of normal plasma (0.32% sodium citrate weight to volume ratio [w/v] with an equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with or without 8μM anti-fXII IgG. After 5 minutes at room temperature (RT), 65 μL of aPTT reagent (Diagnostica Stago) was added, followed by a 5-minute incubation at 37°C. CaCl2 (25 mM–65 μL) was added and time to clot formation determined on an ST4 fibrometer (Diagnostica Stago). In separate assays, 65 μL of fXIIa (50 nM) in PBS was incubated with an equal volume of antibody (1 µM) or vehicle for 15 minutes prior to addition of 65 μL of plasma. CaCl2 was added and time to clot formation determined.

fXII activation

Polyphosphate (75-100 phosphate units) was prepared by gel electrophoresis as described.9 fXII (100 nM) was incubated with aPTT reagent (2.5% of total volume) or polyphosphate (2 µM) at 37°C in the presence of 1 µM 9A2, 15H8, both antibodies, or vehicle in reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, and 1 mg/mL polyethylene glycol 8000). At various times, aliquots were removed into Polybrene (5 µM final). fXIIa activity was identified by adding chromogenic substrate S-2302 (500 μM; Diapharma) and following changes in optical density (OD) 405 nm on a microplate reader. Results were compared with a control curve prepared with pure fXIIa.

PK activation

fXIIa (1 nM) was incubated with PK (50 nM) and HK (70 nM) in reaction buffer containing 250 μM CS-31(02) (Biophen) at RT, with or without aPTT reagent (5% volume to volume ratio [v/v]), and with or without anti-fXII IgG (100 nM). Changes in OD 405 nm reflecting conversion of PK to α-kallikrein were followed on a microplate reader.

Thrombin generation

Normal plasma (0.32% sodium citrate w/v) was supplemented with 415 μM Z-Gly-Gly-Arg-AMC, 5 μM phosphatidylcholine/phosphatidylserine vesicles, and 4 μM IgG anti-fXII IgG. Supplemented plasma (40 μL) was mixed with aPTT reagent (1% v/v) or type I fibrillar collagen (100 μg/mL; Chrono-Log). Ten microliters of 20 mM HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid), pH 7.4, 100 mM CaCl2, 6% bovine serum albumin (BSA) was added and fluorescence (excitation λ 390 nm, emission λ 460 nm) was monitored at 37°C on a Thrombinoscope.34 In a separate experiment, fXII-deficient plasma (George King) was treated in a similar manner, except that 5 nM fXIIa was added with aPTT reagent (5% v/v). Each condition was tested 3 times in duplicate. Peak thrombin generation and endogenous thrombin potential (ETP) were determined (Thrombinoscope Analysis software, version 3.0).

Flow model

Blood was collected from healthy volunteers (0.32% sodium citrate w/v), and platelets were labeled by adding 1,1′-dimethyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindodicarbocyanine iodide (DiIC15) (2 μM).13 Blood was supplemented with Alexa 594–labeled fibrinogen (20 μg/mL) and 4 μM anti-fXII IgG, and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C prior to use. Glass capillary tubes (0.2 × 2.0 × 50 mm; VitroCom) were coated with 100 μg/mL type I fibrillar collagen (Chrono-Log) overnight at 4°C, then blocked with 0.5% BSA. Blood was perfused through tubes at an initial shear rate of 300 s−1 using a syringe pump. Prior to entering the capillary tube, blood was mixed with 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 154 mM NaCl with 37.5 mM CaCl2, 19.8 mM MgCl2 via a second pump and passed through a coiled 12-cm mixing tube. Blood is diluted ∼20% by this step, with final free [Ca2+] and [Mg2+] ∼2.5 and 1.2 mM, respectively. Tubes were subsequently perfused with 3.5% formaldehyde/PBS solution and imaged by laser-scanning microscopy, using a Zeiss LSM 710 microscope.

Capillary occlusion assay

Glass35 capillary tubes (0.2 × 2 mm; VitroCom) were incubated for 1 hour at RT with fibrillar collagen (100 µg/mL), washed with PBS, blocked with 5 mg/mL denatured BSA for 1 hour, then placed in a vertical position. The top of the tube was connected to reservoir, and the bottom was immersed in PBS. Human blood (0.32% sodium citrate w/v) supplemented with 7.5 mM CaCl2 and 3.75 mM MgCl2 was added to the reservoir. Blood flows through the tube under the force of gravity. The height of the sample reservoir was maintained to produce an initial shear rate of 300 s−1.

Mouse thrombosis model

fXII-deficient (fXII−/−) C57Bl/6 mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital. PBS (100 μL) with or without 10 μg of human fXII, and with or without 100 μg of anti-fXII IgG, was infused into the right jugular vein. Thrombus formation was induced in the right carotid artery by applying 3.5% ferric chloride (FeCl3), as described.8 Arterial blood flow was monitored for 30 minutes using a Doppler flow probe (Model 0.5 VB; Transonic System). Studies with mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Vanderbilt University.

Baboon thrombosis model

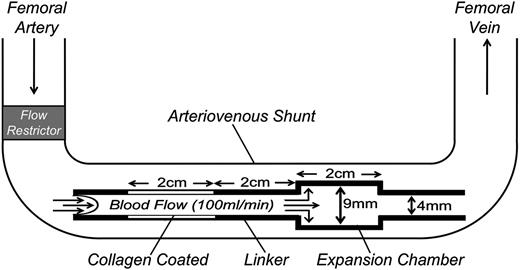

Nonterminal studies were performed on 2 male baboons (Papio anubis) with exteriorized femoral arteriovenous shunts, as described.8,12,13 Thrombus formation was initiated by deploying a thrombogenic graft (Figure 2) into the shunt for 60 minutes. The graft comprised a 20 × 4 mm ePTFE (Gortex) segment coated with collagen, a 20 × 4 mm silicon rubber linker, and a 20 × 9 mm silicon rubber expansion chamber. Flow through the shunt was restricted to 100 mL per minute, producing an initial wall shear rate in the graft of 265 s−1. Platelet deposition in the graft and expansion chamber was assessed in real time by quantitative imaging of 111In-labeled platelet accumulation using a GE-400T γ scintillation camera interfaced to a NuQuest InteCam computer system. Endpoint fibrin deposition was determined by direct measurement of 125I-labeled fibrinogen, as described.8,12,13 Plasma thrombin-antithrombin (TAT) complex levels were measured with an Enzygnost TAT ELISA (Siemens). Studies with baboons were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Oregon Health and Sciences University.

Schematic diagram of the arteriovenous shunt and thrombogenic device used to study thrombosis in baboons. Thrombogenic devices contain a 20-mm long segment of ePTFE graft tubing (4-mm diameter) coated with collagen and a 20-mm expansion chamber made of silicon rubber tubing (9-mm diameter, 20-mm length) downstream of the collagen-coated segment. The collagen-coated segment and expansion chamber are connected by a 20-mm linker made of uncoated silicon tubing (4-mm diameter). Flow through the arterio-venous shunt is adjusted to 100 mL per minute by a flow restrictor, producing an initial shear rate in the collagen-coated portion of the thrombogenic device of 265 s−1.

Schematic diagram of the arteriovenous shunt and thrombogenic device used to study thrombosis in baboons. Thrombogenic devices contain a 20-mm long segment of ePTFE graft tubing (4-mm diameter) coated with collagen and a 20-mm expansion chamber made of silicon rubber tubing (9-mm diameter, 20-mm length) downstream of the collagen-coated segment. The collagen-coated segment and expansion chamber are connected by a 20-mm linker made of uncoated silicon tubing (4-mm diameter). Flow through the arterio-venous shunt is adjusted to 100 mL per minute by a flow restrictor, producing an initial shear rate in the collagen-coated portion of the thrombogenic device of 265 s−1.

Results

Anti-fXII antibodies

Antibodies 9A2 and 15H8 recognize fXII in human and baboon plasma (Figure 1B) on western blots. The fXII gene arose from a duplication of the HGFA gene.33,36 fXII and HGFA have similar domain structures, except that fXII has a proline-rich region not found in HGFA (Figure 1A). We prepared fXII with individual domains replaced by corresponding HGFA domains. With the exception of the fXII/HGFA-fibronectin type II domain chimera, all proteins were secreted by a human fibroblast line (Figure 1C top). 9A2 and 15H8 recognize distinct epitopes on fXII, with 9A2 binding to the fibronectin type I and/or EGF2 domains (Figure 1C, middle), and 15H8 to the EGF2 /kringle domains (Figure 1C, bottom).

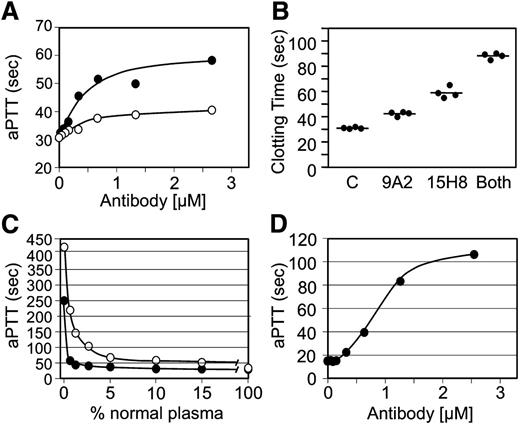

9A2 and 15H8 prolong the aPTT of human plasma (Figure 3A), with 15H8 having a greater effect. Antibodies at ∼2 to 3 times the plasma fXII concentration achieved maximum inhibition. Combining 9A2 and 15H8 produced a greater degree of inhibition (Figure 3B), consistent with the 2 antibodies recognizing distinct epitopes. The curve (open circles) in Figure 3C shows the relationship between fXII concentration and the aPTT. Using this curve for comparison, the effect of 15H8 on the aPTT of normal plasma corresponds to >95% inhibition of fXII activity, while 9A2 achieves ∼50% reduction. 15H8 prolonged the aPTT of baboon plasma (Figure 3D) to a greater degree than human plasma (Figure 3A). The curve with closed circles in Figure 3C was prepared by mixing baboon plasma with fXII-deficient human plasma. When data in Figure 3D are compared with this curve, it appears that 15H8 inhibits >99% of the fXII activity in baboon plasma. 9A2 did not prolong the aPTT of baboon plasma.

Effects of anti-fXII antibodies on plasma coagulation. (A) Results of a standard aPTT assay using a silica-based reagent for normal human plasma supplemented with different concentrations of IgG 9A2 (○) or 15H8 (●). Data are averages of 2 clotting times. (B) aPTT assay of normal human plasma supplemented with control vehicle (C), 4 μM 9A2 or 15H8, or 4 μM of both antibodies. Each circle represents a single clotting time, and the bar indicates the mean for the group. (C) aPTT results for human fXII-deficient plasma mixed with normal human (○) or baboon (●) plasma in various ratios. (D) Effect of different concentrations of IgG 15H8 on the aPTT of baboon plasma.

Effects of anti-fXII antibodies on plasma coagulation. (A) Results of a standard aPTT assay using a silica-based reagent for normal human plasma supplemented with different concentrations of IgG 9A2 (○) or 15H8 (●). Data are averages of 2 clotting times. (B) aPTT assay of normal human plasma supplemented with control vehicle (C), 4 μM 9A2 or 15H8, or 4 μM of both antibodies. Each circle represents a single clotting time, and the bar indicates the mean for the group. (C) aPTT results for human fXII-deficient plasma mixed with normal human (○) or baboon (●) plasma in various ratios. (D) Effect of different concentrations of IgG 15H8 on the aPTT of baboon plasma.

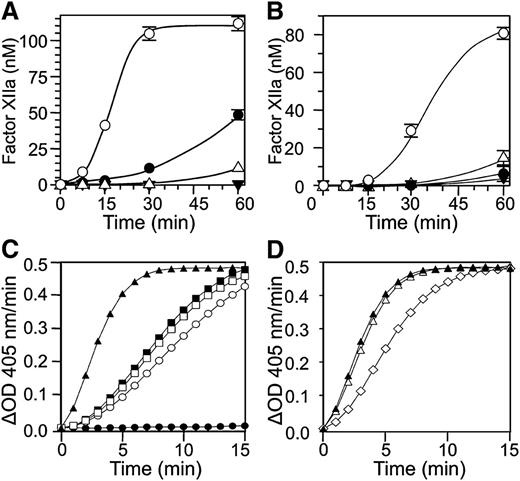

Effects of anti-fXII antibodies on fXII and PK activation in vitro

fXII undergoes autoactivation in the presence of a variety of surfaces and polymers.9,14,19 We tested the capacity of anti-fXII antibodies to inhibit fXII autoactivation in the presence of a silica-based aPTT reagent (Figure 4A) or polyphosphate (Figure 4B). Both antibodies reduced fXII activation with the aPTT reagent, with 15H8 having a greater effect, while both had roughly similar effects with polyphosphate.

Effects of anti-fXII antibodies on fXII and PK. fXII activation: conversion of fXII to fXIIa in the presence of (A) a silica-based aPTT reagent or (B) polyphosphate (2 μM) and vehicle (○), 9A2 (●), 15H8 (△), or the combination of 9A2 and 15H8 (▼). Results are means of 3 separate runs ± 1 standard deviation (SD). Prekallikrein activation: (C) PK (50 nM) was incubated in reaction buffer containing 250 μM CS-3102 at RT, in the absence (●) or presence (○) of fXIIa (1 nM). Cleavage of CS-3102 was monitoring by following changes in OD 405 nm. fXIIa at the concentration used does not cleave CS-3102 at an appreciable rate in the absence of PK (not shown). Addition of HK (□, 70 nM) or aPTT reagent (■, 5% v/v) to the reaction with PK and fXIIa had modest effects on the rate of activation, while addition of both aPTT reagent and HK (▲) had a greater effect. (D) The effects of vehicle (▲) 100 nM 9A2 (△) and 15H8 (♢) on activation of PK by fXIIa in the presence of aPTT reagent (5% v/v) and HK (70 nM).

Effects of anti-fXII antibodies on fXII and PK. fXII activation: conversion of fXII to fXIIa in the presence of (A) a silica-based aPTT reagent or (B) polyphosphate (2 μM) and vehicle (○), 9A2 (●), 15H8 (△), or the combination of 9A2 and 15H8 (▼). Results are means of 3 separate runs ± 1 standard deviation (SD). Prekallikrein activation: (C) PK (50 nM) was incubated in reaction buffer containing 250 μM CS-3102 at RT, in the absence (●) or presence (○) of fXIIa (1 nM). Cleavage of CS-3102 was monitoring by following changes in OD 405 nm. fXIIa at the concentration used does not cleave CS-3102 at an appreciable rate in the absence of PK (not shown). Addition of HK (□, 70 nM) or aPTT reagent (■, 5% v/v) to the reaction with PK and fXIIa had modest effects on the rate of activation, while addition of both aPTT reagent and HK (▲) had a greater effect. (D) The effects of vehicle (▲) 100 nM 9A2 (△) and 15H8 (♢) on activation of PK by fXIIa in the presence of aPTT reagent (5% v/v) and HK (70 nM).

When PK is incubated with fXIIa in solution, α-kallikrein is formed (Figure 4C, open circle). The rate of PK activation by fXIIa is enhanced slightly by adding HK (Figure 4C, open square) or aPTT reagent (Figure 4C, filled square), while adding both significantly increases activation (Figure 4C, filled triangle). This is consistent with the well-described surface-dependent cofactor effect of HK on PK activation by fXIIa. 9A2 has little effect on surface-dependent PK activation by fXIIa (Figure 4D, open triangle), while 15H8 reduced the rate of the reaction (Figure 4D, open diamond).

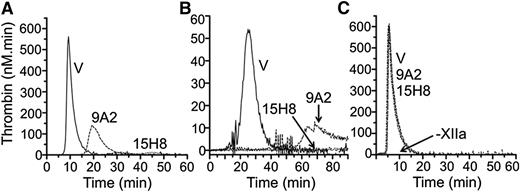

Effects of anti-fXII antibodies on thrombin generation in plasma

Addition of aPTT reagent to normal plasma leads to a burst of thrombin generation (Figure 5A, ETP 1805 nM × minutes) that is almost completely blocked by 15H8. 9A2 reduces ETP by ∼50% (961 nM × minutes), with a delay in peak thrombin generation. Similar results were obtained using collagen to induce coagulation (Figure 5B). In contrast, neither antibody blocks thrombin generation induced by adding fXIIa to fXII-deficient plasma supplemented with aPTT reagent (Figure 5C). These data indicate that 15H8 and 9A2 mostly inhibited fXII autoactivation to fXIIa while 15H8, but not 9A2, also reduces fXIIa activation of PK. Neither antibody affects surface-dependent fXI activation by fXIIa in plasma appreciably.

Effects of anti-fXII antibodies on thrombin generation. Shown are the effects of 4 μM 9A2, 15H8, or vehicle (V) on thrombin generation in normal plasma triggered with (A) 1% v/v aPTT reagent or (B) 100 μg/mL type I collagen. No thrombin is generated in the absence of aPTT reagent or collagen. (C) Thrombin generation in fXII-deficient plasma supplemented with 5 nM fXIIa in the presence of 500 nM 9A2, 15H8, or vehicle (V). –XIIa indicates that no thrombin was generated in the absence of fXIIa.

Effects of anti-fXII antibodies on thrombin generation. Shown are the effects of 4 μM 9A2, 15H8, or vehicle (V) on thrombin generation in normal plasma triggered with (A) 1% v/v aPTT reagent or (B) 100 μg/mL type I collagen. No thrombin is generated in the absence of aPTT reagent or collagen. (C) Thrombin generation in fXII-deficient plasma supplemented with 5 nM fXIIa in the presence of 500 nM 9A2, 15H8, or vehicle (V). –XIIa indicates that no thrombin was generated in the absence of fXIIa.

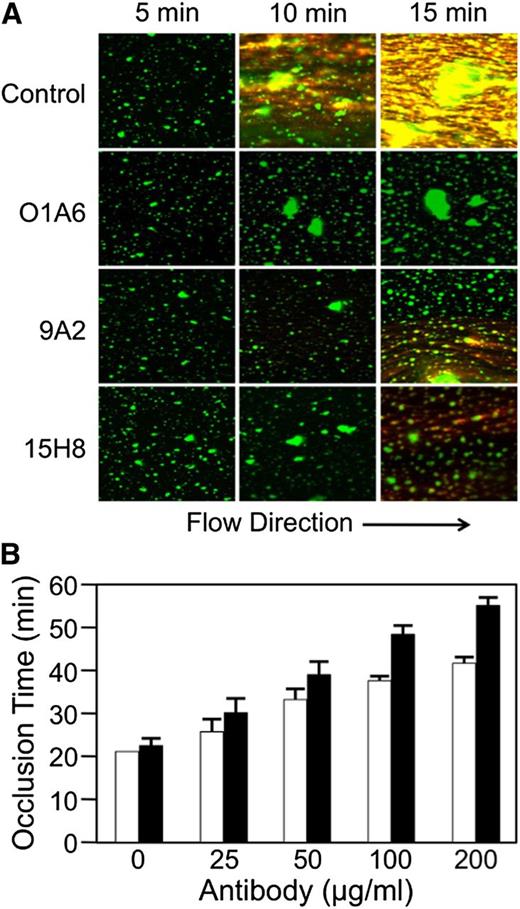

Anti-fXII antibodies in flow models

Anti-fXI antibodies inhibit fibrin formation in recalcified human blood perfused across collagen-coated surfaces.13 Figure 6A shows images from collagen-coated tubes perfused with human blood at a shear rate of 300 s−1. Platelet aggregates appear green and fibrin strands orange. The anti-fXI antibody O1A613 blocks fibrin generation in this system. 9A2 and 15H8 substantially reduce fibrin deposition, although some fibrin does form. These data indicate that the anti-fXII antibodies have an effect in flowing human blood that is similar to the effect reported for anti-fXI antibodies.13 9A2 and 15H8 also prolonged the time it takes for blood to occlude collagen-coated capillary tubes in which flow is induced by gravity (Figure 6B). At a concentration (1.3 μM) ∼3.5-fold higher than the plasma fXII concentration, 9A2 increased time to occlusion twofold, while 15H8 increased it nearly threefold.

Effect of anti-fXII antibodies on fibrin formation in human blood under flow. (A) Immunofluorescent images (Zeiss LSM 710, objective lenses: 20×/0.80 Plan-Apochromat, ×20 magnification) showing the effects of the anti-fXI IgG O1A6 (300 nM) or the anti-fXII IgGs 9A2 and 15H8 (4 μM) on fibrin deposition over time in recalcified human blood flowing across collagen-coated surfaces with an initial average shear rate of 300 s−1. Direction of flow is indicated at the bottom of the image. Fibrin appears orange in these images and platelet aggregates appear green. (B) Collagen-coated glass capillary tubes were perfused with recalcified human blood driven by a constant pressure gradient under the force of gravity. Shown are times to capillary occlusion in the presence of varying concentrations of 9A2 (□) or 15H8 (▪). Each bar represent means for 3 separate measurements ± standard error.

Effect of anti-fXII antibodies on fibrin formation in human blood under flow. (A) Immunofluorescent images (Zeiss LSM 710, objective lenses: 20×/0.80 Plan-Apochromat, ×20 magnification) showing the effects of the anti-fXI IgG O1A6 (300 nM) or the anti-fXII IgGs 9A2 and 15H8 (4 μM) on fibrin deposition over time in recalcified human blood flowing across collagen-coated surfaces with an initial average shear rate of 300 s−1. Direction of flow is indicated at the bottom of the image. Fibrin appears orange in these images and platelet aggregates appear green. (B) Collagen-coated glass capillary tubes were perfused with recalcified human blood driven by a constant pressure gradient under the force of gravity. Shown are times to capillary occlusion in the presence of varying concentrations of 9A2 (□) or 15H8 (▪). Each bar represent means for 3 separate measurements ± standard error.

Anti-fXII antibodies in a murine thrombosis model

Exposing blood vessels in mice to FeCl3 results in changes to the blood vessel endothelium that lead to thrombus formation in a fXII- and fXI-dependent manner.7,8,37 fXII-deficient C57Bl/6 mice do not develop carotid artery occlusion when exposed to 3.5% FeCl3, while wild-type mice reproducibly develop occlusion in 10 to 15 minutes.8 Infusing human fXII into fXII-deficient animals to raise the plasma level to ∼20% of normal restores the wild-type phenotype (n = 5, all with vessel occlusion). Coadministration of fXII and a 10-fold molar excess of 9A2 reduced the incidence of arterial occlusion to 50%, while 15H8 prevented arterial occlusion (n = 6 for each antibody).

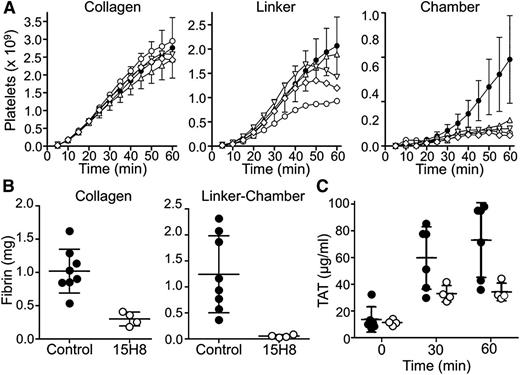

Anti-fXII antibodies in a baboon thrombosis model

We tested the effects of 15H8 on platelet (Figure 7A) and fibrin (Figure 7B) deposition in thrombogenic devices deployed into arteriovenous shunts in 2 baboons (Figure 2). Thrombus formation is triggered in the collagen-coated segment of the graft where the initial wall shear rates is ∼265 s−1. A distal expansion chamber made of silicon rubber is incorporated to assess thrombus propagation under lower shear (<30 s−1; Figure 2). 15H8 (5-6 mg/kg IV) prolonged the aPTT from 29.5 to 50 seconds in 1 baboon, and from 33.5 to 78 seconds in a second animal. Based on the curve in Figure 3C (black circles), these results indicate substantial (∼99%) inhibition of fXII activity. The inhibitory effect lasted >24 hours. Results were obtained for 9 thrombogenic devices tested before, and 4 devices tested after, 15H8 administration. Devices were tested sequentially, and at least 30 minutes were allowed to lapse between removal of a device and placement of a new device. Data and means are shown in Figure 7, however, the design of the study is not conducive to a detailed statistical analysis.15H8 did not affect platelet deposition (Figure 7A) within the collagen-coated graft, had a modest effect in the linker downstream from the collagen, and caused a substantial reduction (∼80%) compared with control in the expansion chamber. 15H8 reduced fibrin deposition by 70% ± 5% in the collagen-coated portion of the graft (Figures 7B, left panel), and by 95% ± 1% in the linker-expansion chamber (Figure 7B, right panel). The grafts promote thrombin generation that is detectable in the systemic circulation as a TAT complex.8,13 15H8 reduced TAT levels by ∼50% (Figure 7C).

Effect of 15H8 on platelet and fibrin deposition in a baboon arteriovenous shunt thrombosis model. Thrombogenic devices depicted in Figure 2 were inserted into femoral arteriovenous shunts in olive baboons as described.9,13,14 Flow through the grafts was maintained at 100 mL per minute, producing an initial average wall shear rate of 265 s−1 within the 4-mm diameter portions of the graft. (A) Platelet accumulation in the collagen-coated, silicon linker, and silicon expansion chamber segments of grafts was assessed in real time by imaging of local 111In-labeled platelet accumulation using a GE-400T camera with NuQuest InteCam. The curves composed of closed circles (●) with error bars (±1 SD) represent mean values for 9 devices inserted into arterio-venous shunts in 2 untreated animals (control results). Individual results for 4 devices tested in the same 2 animals at least 1 hour after administration of anti-fXII antibody 15H8 (5-6 mg/kg IV) are indicated by the symbols ○, △, ▽, and ♢. (B) Endpoint determinations of total 125I-labeled fibrin deposition during the experiments in panel A. Fibrin deposition in the collagen-coated graft segment (left panel) and silicon expansion chamber (right panel) were determined for 8 of the 9 devices inserted before animals received 15H8 (●) and for the 4 devices tested after animals received 15H8 (○). Large bars indicate mean values and smaller bars ± 1 SD (C) Plasma TAT complex measured in blood obtained at various times after graft insertion from the arteriovenous shunt upstream of the site of graft insertion for 6 of 8 control grafts (●), and the 4 grafts placed after 15H8 administration (○). Large bars indicate mean values and smaller bars ± 1 SD.

Effect of 15H8 on platelet and fibrin deposition in a baboon arteriovenous shunt thrombosis model. Thrombogenic devices depicted in Figure 2 were inserted into femoral arteriovenous shunts in olive baboons as described.9,13,14 Flow through the grafts was maintained at 100 mL per minute, producing an initial average wall shear rate of 265 s−1 within the 4-mm diameter portions of the graft. (A) Platelet accumulation in the collagen-coated, silicon linker, and silicon expansion chamber segments of grafts was assessed in real time by imaging of local 111In-labeled platelet accumulation using a GE-400T camera with NuQuest InteCam. The curves composed of closed circles (●) with error bars (±1 SD) represent mean values for 9 devices inserted into arterio-venous shunts in 2 untreated animals (control results). Individual results for 4 devices tested in the same 2 animals at least 1 hour after administration of anti-fXII antibody 15H8 (5-6 mg/kg IV) are indicated by the symbols ○, △, ▽, and ♢. (B) Endpoint determinations of total 125I-labeled fibrin deposition during the experiments in panel A. Fibrin deposition in the collagen-coated graft segment (left panel) and silicon expansion chamber (right panel) were determined for 8 of the 9 devices inserted before animals received 15H8 (●) and for the 4 devices tested after animals received 15H8 (○). Large bars indicate mean values and smaller bars ± 1 SD (C) Plasma TAT complex measured in blood obtained at various times after graft insertion from the arteriovenous shunt upstream of the site of graft insertion for 6 of 8 control grafts (●), and the 4 grafts placed after 15H8 administration (○). Large bars indicate mean values and smaller bars ± 1 SD.

Discussion

Anticoagulants currently used for treating or preventing thromboembolism directly inhibit thrombin or factor Xa activity, or limit production of their precursors. Although effective, this strategy increases bleeding risk because the targeted proteases are central to hemostasis. This places limits on the types of patients who can be treated safely with anticoagulants, and the clinical scenarios in which treatment is applied. The intuitive notion that thrombosis reflects “hemostasis in the wrong place” has been brought into question by data from rodent models demonstrating prothrombotic roles for the proteases fXIa and fXIIa.6,,,-10,38,-40 These observations suggest that it may be possible to develop therapies in which antithrombotic effects are largely or completely dissociated from antihemostatic effects.

Both fXIa and fXIIa have features that make them attractive therapeutic targets. There is substantial evidence supporting a role for fXI in human thrombosis. Plasma fXI levels at the upper end of the normal range increase risk for myocardial infarction,26 stroke,29 and venous thromboembolism (VTE)25,28 relative to the remainder of the population, while severe fXI deficiency reduces incidence of stroke27 and VTE.30 The major function of fXIa, activation of fIX, appears to serve a limited role in hemostasis, primarily directed at preventing excessive trauma-induced bleeding in tissues with high fibrinolytic activity such as the oropharynx and urinary tract.14,15 In patients with severe fXI deficiency, some types of surgery41 and normal child birth42 are associated with relatively low rates of excessive bleeding in the absence of factor replacement. Indeed, many fXI-deficient individuals do not experience abnormal hemostasis, and symptomatic patients rarely bleed spontaneously (with the exception of menorrhagia),14,15 indicating that drugs targeting fXIa would be associated with less bleeding than drugs that inhibit thrombin or fXa. The absence of a bleeding diathesis in fXII-deficient individuals suggests that drugs specifically targeting this protein would not compromise hemostasis, allowing them to be used in patients with the most restrictive contraindications for current anticoagulation therapies. Enthusiasm for developing fXIIa inhibitors, however, is tempered by 2 considerations. First, while numerous functions are attributed to fXIIa, the physiologic roles of the protease are incompletely understood. Perhaps as important, a clear link between fXII and thrombosis in humans is not established.

Anecdotal reports suggesting that fXII deficiency actually predisposes to VTE date back to the death of the first person identified with severe fXII deficiency from a pulmonary embolism.43 Subsequent investigation did not confirm an association between fXII levels and VTE,44,45 and an analysis of case reports concluded that most thrombotic events in fXII-deficient patients are unrelated to the deficiency.46 However, 2 recent studies have returned the issue of fXII and thrombotic risk to the forefront. Doggen et al reported an inverse relationship between plasma fXII levels and risk of myocardial infarction,26 with an odds ratio of 0.4 for individuals in the highest quartile for fXII level compared with those in the lowest quartile. This study examined fXII within the broad normal range, and not the consequences of severe fXII deficiency, which may be more relevant for anticipating effects of therapeutic fXII inhibition. Endler et al also observed an inverse relationship between plasma fXII and all-cause mortality,31 with participants with 10% to 20% of the normal fXII level having a hazard ratio of 4.7 compared with those with fXII >100% of normal. Curiously, there was no significant increase in mortality for subjects with fXII levels of 1% to 10% of normal, suggesting a fundamental difference between severe and moderate deficiency. Data from the studies from Doggen et al and Endler et al seem at odds with work showing that elevated plasma fXIIa is associated with an increased risk of coronary events.47,48 It is difficult to draw unifying conclusions from this data, but there seems to be grounds for concern that fXII may not contribute to thrombosis in humans and rodents in the same manner, or to the same extent.

The current study examined the contribution of fXII in human/primate models that require fXI for normal thrombus formation. An assumption here is that fXIIa contributes to thrombosis through fXI activation, and ultimately thrombin generation, although other fXIIa-mediated activities could be involved. For example, fXIIa can have direct effects on fibrin structure that could contribute to thrombus stability.49 Antibodies 9A2 and 15H8 recognize epitopes on the fXII heavy chain. They reduce fXII activity in plasma in which contact activation is triggered by inhibiting fXII activation, and not fXIIa activity, supporting work showing the fXII heavy chain is required for binding to polyanions.50,-52 In baboons, 15H8 reduced fibrin deposition in thrombogenic grafts, and limited platelet-rich thrombus growth downstream from the collagen-coated graft segment. The antibody reduced thrombin-antithrombin complex levels induced by the grafts, consistent with the premise that a reduction in thrombin generation was behind the antithrombotic effect. It is illustrative to compare this performance to those of anti-fXI antibodies in this model. The antibody O1A6 is a potent inhibitor of factor IX activation by fXIa.13,32 O1A6 reduces systemic TAT levels by ≥80%, and significantly reduces platelet and fibrin accumulation within the collagen-coated segments of grafts. Platelets adhere to collagen in the presence of O1A6, but there is a defect in 3-dimensional thrombus growth,13 consistent with the thrombus instability observed in fXI- and fXII-deficient mice.7,8 The considerably greater effect of O1A6 compared with 15H8 may be explained by its larger effect on thrombin generation. The anti-fXI antibody 14E11 inhibits fXI activation by fXIIa, but does not affect fXIa activity.8 Similar to 15H8, 14E11 had relatively little effect on platelet accumulation in the collagen-coated graft segment, but did limit downstream platelet deposition. The performance of these antibodies in human blood in a collagen-based flow system are, in general, consistent with those for the baboon model. Taken as a whole, the data suggest that inhibiting fXI activation by fXIIa, either by inhibiting fXIIa generation (15H8) or by blocking fXIIa activation of fXI (14E11) can inhibit thrombus formation by reducing thrombin generation. The effect, however, is not as pronounced as the one produced by inhibiting fXIa activation of factor IX (O1A6). Interestingly, O1A6,13 14E118 and 15H8 prolong the aPTT to similar extents in treated baboons, demonstrating that it is the mechanism targeted, and not the absolute value of the aPTT, that determines the antithrombotic effect. The primate models used in this study (the baboon and human ex vivo flow models) are collagen-based. Although mechanistic details for the process(es) responsible for fXII activation cannot be definitively established in these models, collagen may contribute directly to fXII activation through a process similar or identical to contact activation. The findings of this study, therefore, may only be applicable to surface-induced thrombosis, such as a clot associated with an intravascular catheter, and may not be applicable to thrombus formation triggered by other stimuli. However, it should be noted that 15H8 is effective in preventing FeCl3-induced thrombosis in mice. Here, thrombus formation is initiated by changes in vascular endothelium that promote red blood cell and platelet adhesion,37 with exposure of subendothelial collagen probably playing a relatively minor role.

The results suggesting that fXII inhibition has a smaller antithrombotic effect than fXI inhibition in primates contrast with those obtained with mouse thrombosis models. We observed that fXII-deficient mice are somewhat more resistant to carotid artery thrombosis induced by FeCl3 or laser injury than are fXI-deficient mice.8 Thrombin-mediated feedback activation of fXI may explain the observation that fXII deficiency does not cause a hemorrhagic tendency.34 Perhaps this mechanism plays a more prominent role in thrombus formation in primates than in mice, accounting for the greater effectiveness of O1A6 compared with 15H8 and 14E11 in baboons. This scenario is consistent with the more modest reduction in TAT levels in baboons treated with 15H8 compared with O1A6.13 Alternatively, it appears that relatively small amounts of fXII have significant effects on the aPTT in primate plasmas. Therefore, a high degree of fXII inhibition (not easily obtained with an antibody) may be required to produce an antithrombotic effect. Indeed, while 15H8 reduced fXII activity in the aPTT, it did not block it completely. Consistent with this, Pixley and coworkers reported that an antibody that neutralized ∼60% of fXII activity in baboons did not affect endotoxin-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation.53 In contrast, reducing fXI levels in baboons by as little as 50% affects thrombus formation in the arteriovenous shunt model.54 Furthermore, inhibiting fXII with an antibody to produce a similar effect to total fXII deficiency is made difficult by the relatively high plasma fXII concentration (400 nM). The plasma fXI concentration is only 30 nM. These observations have implications for developing therapeutic fXII/XIIa inhibitors, which may need to inhibit a high percentage of protease activity to produce a therapeutic effect.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Jennifer Greisel’s expert technical support with the primate studies, and Dr William Dupont for recommendations on the use of statistical analysis.

The authors acknowledge support from National Institutes of Health awards (Heart, Lung and Blood Institute) HL81326, HL58837 (D.G.), HL106919 (I.M.V.), HL047014 (J.H.M.), and HL101972 (A.G., O.J.T.M.); (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases) AI088937 (A.G., E.I.T.); (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke) NS077600 (P.Y.L.); UL1TR000128 to the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute, and RR000163 to the Oregon National Primate Research Center from the National Institutes of Health.

Authorship

Contribution: A.M. performed flow model studies, designed experiments for characterization of effects of antibodies on fXII, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript; P.Y.L. performed baboon studies and contributed to antibody development and to writing of the manuscript; A.E.G. and S.L.G. characterized the effects of antibodies on fXII activation and fXIIa activity in vitro; C.P. conducted capillary flow studies; Q.C. designed and conducted murine thrombosis studies; M-f.S. prepared the fXII/HGFA mutants and conducted studies to map the binding sites of 9A2 and 15H8 on fXII; O.J.T.M. contributed to design and interpretation of flow model experiments; E.I.T. contributed to antibody generation and characterization, and to baboon thrombosis studies; H.K. contributed to the design of XII/HGFA chimeras; T.R. contributed to the design of murine thrombosis models, and to the writing of the manuscript; J.H.M. contributed to the design of experiments with poly-P, and to the writing of the manuscript; A.G. oversaw studies involving baboons, generation of antibodies, and the writing of the manuscript; and D.G was responsible for oversight of the project and preparation of the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: D.G. is a consultant, and receives consultant’s fees from several pharmaceutical companies. P.Y.L., E.I.T., and A.G. are employees of the company Aronora. A.M., P.Y.L., A.G., D.G., Oregon Health and Sciences University, and Vanderbilt University may have financial interest in the results of this study. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: David Gailani, Hematology/Oncology Division, Vanderbilt University, 777 Preston Research Building, 2220 Pierce Ave, Nashville, TN 37232; e-mail: dave.gailani@vanderbilt.edu.

References

Author notes

A.M. and P.Y.L. contributed equally to the study and to manuscript preparation and should be considered cofirst authors.