Abstract

The origin of aberrant DNA methylation in cancer remains largely unknown. In the present study, we elucidated the DNA methylome in primary acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) and the role of promyelocytic leukemia–retinoic acid receptor α (PML-RARα) in establishing these patterns. Cells from APL patients showed increased genome-wide DNA methylation with higher variability than healthy CD34+ cells, promyelocytes, and remission BM cells. A core set of differentially methylated regions in APL was identified. Age at diagnosis, Sanz score, and Flt3-mutation status characterized methylation subtypes. Transcription factor–binding sites (eg, the c-myc–binding sites) were associated with low methylation. However, SUZ12- and REST-binding sites identified in embryonic stem cells were preferentially DNA hypermethylated in APL cells. Unexpectedly, PML-RARα–binding sites were also protected from aberrant DNA methylation in APL cells. Consistent with this, myeloid cells from preleukemic PML-RARα knock-in mice did not show altered DNA methylation and the expression of PML-RARα in hematopoietic progenitor cells prevented differentiation without affecting DNA methylation. Treatment of APL blasts with all-trans retinoic acid also did not result in immediate DNA methylation changes. The results of the present study suggest that aberrant DNA methylation is associated with leukemia phenotype but is not required for PML-RARα–mediated initiation of leukemogenesis.

Key Points

APL is characterized by DNA hypermethylation with increased variability and DNA hypomethylation at chromosome ends.

Occupied transcription factor binding sites, including PML-RAR&α binding sites, are protected from DNA methylation in APL.

Introduction

DNA methylation is important for hematopoietic lineage commitment and differentiation.1-3 Aberrant DNA methylation patterns are a characteristic feature of cancer,4,5 but the mechanism behind aberrant DNA methylation remains obscure. Specific DNA methylation patterns often occur alongside defined genetic DNA mutations.6-8 One plausible model proposes that oncogenes directly or indirectly induce aberrant DNA methylation patterns and thereby control gene expression.9-11 This model is intriguing for mutated transcription factors, several of which have been reported to recruit DNA-methyltransferase activity to their target gene promoters.9,11,12 Alternative models suggest a more random induction of DNA methylation changes.13,14 In most cancers, the numbers of both genetic alterations and DNA methylation changes are high,15 so the relationship between DNA mutations and epigenetic changes cannot be deciphered easily. In addition, many oncogenes do not induce disease when expressed alone and few accurate oncogenic animal models exist.

One important exception is the promyelocytic leukemia–retinoic acid receptor α (PML-RARα) oncogene in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL). Virtually all APL patients carry the PML-RARα translocation t(15;17), which suggests that APL is molecularly homogeneous.16 PML-RARα–induced leukemia exhibits characteristic clinical features that are evident in all patients. There are also genetic mouse models accurately representing the situation in humans.17 PML-RARα is therefore an exemplary oncogene with which to evaluate the contribution of oncogenes to epigenetic dysregulation.

Key elements of PML-RARα–induced leukemogenesis have been elucidated. Genes involved in processes such as differentiation and apoptosis are suppressed in APL and reactivated on high-dose all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) treatment.9,18,19 Small-scale studies involving a few genes revealed that PML-RARα binding was directly associated with this transcriptional suppression.9,12,18,20-22 DNA methylation, histone deacetylation, and histone methylation have all been implicated in this gene-silencing process. It was proposed that PML-RARα recruits histone deacetylases, DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), and Polycomb group proteins directly to its target genes.9,12,23

Recent genome-wide studies have now identified nearly 3000 binding sites of PML-RARα and have shed light on PML-RARα–associated epigenetic alterations.24,25 Binding of PML-RARα was associated with deregulated H3-acetylation at 80% of PML-RARα target genes. However, the specific role of DNA methylation in APL pathogenesis remains unclear.

APL has been associated with a specific methylation phenotype different from other forms of acute myeloid leukemia.6 Overexpression of DNMT3A in APL was also shown to enhance leukemia penetrance in a mouse model.26 However, not all studies could substantiate a role for differential methylation in gene silencing.20,24

Next-generation sequencing approaches allow the accurate evaluation of genome-wide CpG-island methylation at single CpG-site resolution.27 To address the significance of deregulated DNA methylation in APL pathogenesis, in the present study, we analyzed DNA methylation in APL patients at primary diagnosis using reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS). We detected a core set of differentially methylated regions (DMRs) identified across 18 primary APL samples. Our data provide evidence that DNA methylation patterns in APL are not directly dependent on PML-RARα activity at its target sites. Consistent with this, no specific PML-RARα–induced DNA methylation occurred on strong PML-RARα expression in primary hematopoietic progenitors or in preleukemic PML-RARα knock-in mice. Similarly, ATRA treatment of APL blasts did not result in DNA methylation changes. These findings suggest that APL initiation occurs independently of DNA methylation changes, but that DNA methylation influences disease phenotype at the stage of overt leukemia.

Methods

APL patient samples

APL patient samples were obtained from patient BM (median blast count, 80%) at the time of diagnosis with informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Genomic DNA was extracted by standard procedures after density centrifugation. Remission samples were obtained in complete remission after treatment.

RRBS

A total of 0.3-1 μg of DNA was used for RRBS library preparation using a published protocol with minor modifications.28 Briefly, genomic DNA was digested with MspI (NEB), end-repaired and A-tailed with the Klenow-fragment enzyme (NEB), and ligated (NEB) with 5mC-methylated paired-end sequencing adapters (Illumina). Fragments in a range of 40-220 bp insert size were gel purified (NuSieve 3:1 agarose; Lonza). Libraries were bisulfite converted using the EZ DNA Methylation Kit (ZymoResearch) and amplified using PfuTurboCx polymerase (Agilent Technologies). Each library was sequenced on a separate lane using an Illumina HiScanSQ instrument with Version 2.5 sequencing chemistry. Libraries were spiked with 45% PhiX DNA to counteract the imbalance in nucleotide representation. Sequencing data can be downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus (accession no. GSE42119).

Illumina methylation bead array 450K

Bisulfite conversion of genomic DNA was performed using the EZ DNA Methylation Kit. A total of 500 ng of converted DNA was hybridized to an Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip (Illumina) and scanned using the HiScan instrument (Illumina). Data preprocessing and methylation-level extraction were done using Genome Studio Version 2011.1 software, including Methylation Module Version 1.9.0 and Illumina Genome Viewer Module Version 1.9.0 (Illumina). Bead array data can be downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus (accession no. GSE42119).

Bioinformatics analysis

Human (hg19)/mouse (mm9) genomic sequences and other tracks (eg, RefSeq genes) were downloaded from the University of California Santa Cruz Genome Browser database.29 For RRBS data mapping, only reads starting with either TGG or CGG were considered. Adapter sequences were removed using Cutadapt Version 0.9.330 and sequences were mapped to hg19 or mm9 genome using Bismark Version 0.5.31 Methylation calls from Bismark were extracted with a modified script that removed 3′-MspI sites. Methylation data were analyzed in R/Bioconductor using the BiSeq package. Differentially methylated region detection was restricted to regions with high CpG-site density covered across all samples (CpG clusters) within which raw methylation data were smoothed. Only differentially methylated regions with P < .01 and differential methylation > 30% were considered. The false discovery rate for DMRs between APL and controls was estimated to be 5%. The false discovery rate for clinical subgroup DMRs was > 5%. See supplemental Methods for further details (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

PML-RARα knock-in mice

All animal experiments were approved by the Landesamt für Natur, Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz. PML-RARα knock-in mice were kindly provided by Timothy Ley (Washington University, St Louis, MO).17 BM was harvested from 6-month-old PML-RARα knock-in mice and age- and sex-matched C57/BL6 wild-type mice. Overt leukemia was ruled out by FACS, histological analysis, and cytospins. Total BM was MACS sorted for the Gr1+ population and genomic DNA was extracted from the Gr1+ fraction (Gr1 Ab; Miltenyi Biotec).

Retroviral transduction of hematopoietic progenitor cells

A retroviral mSCV-based PML-RARα construct has been described previously.32 BM was extracted from 12-week-old C57/BL6 mice using standard protocols. Lineage depletion using MACS (Miltenyi Biotec) was performed and hematopoietic progenitor cells were stimulated for 72 hours in IMDM (Invitrogen) containing 20% FCS (PAA), SCF (Tebu Bio), IL-3 (Tebu Bio), and IL-6 (PeproTech). Supernatants of PML-RARα and empty vector were obtained via transfection of PlatE cells. Lineage-negative (Lin−) cells were transduced using Retronectin (Takara) and sorted for green fluorescent protein expression. Sorted cells were further cultivated. Genomic DNA was extracted at various time points and cells were analyzed using stained cytospins.

Results

Identification of the genome-wide methylation signature in APL patient samples

RRBS was used to determine the genome-wide methylation signature of primary APL patient samples. First, 18 patient samples were sequenced at primary diagnosis (Figure 1A and supplemental Table 1). To establish methylation patterns that are APL specific, we also analyzed 3 types of control samples from various stages of hematopoiesis. This included density centrifugation–enriched mononuclear cells from remission BM of matched patient samples (n = 8), CD34+ cells from healthy donors (n = 4), and promyelocytes generated in vitro from these CD34+ cells according to an established protocol (supplemental Figure 1).33,34 On average, 1.17 × 107 sequencing reads were uniquely mapped per sample, yielding 9.4 × 105 CpG sites that were covered in all samples.

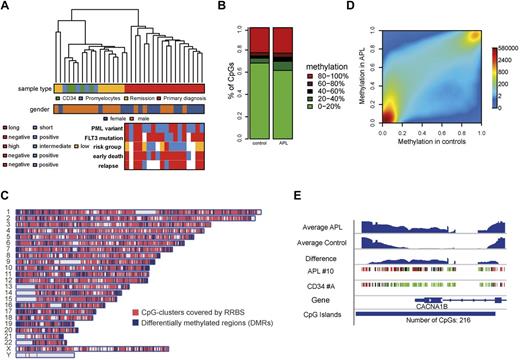

The methylome in APL. (A) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering based on raw DNA methylation levels. The color grid beneath visualizes the sample characteristics. The clustering is based on raw RRBS methylation values. (B) Distribution of methylation levels in APL and control samples. The stacked bar plots show the distribution of raw RRBS methylation levels of CpG sites covered in all samples for APL and control samples, respectively. The raw methylation levels (middle) are encoded by colors ranging from green (low methylation close to 0) to red (high methylation close to 1). Methylation levels were increased in APL samples (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test: P < .001). (C) Chromosomal distribution of covered CpG-clusters and DMRs. The plot shows the genome-wide distribution of CpG sites covered by RRBS together with DMRs detected between APL and controls. (D) Smoothed scatter plot of methylation values for APL versus healthy control samples. Colors represent the density of points ranging from red (high density) to blue (low density). Smoothed RRBS methylation levels were averaged for APL cells and controls. (E) Example of a differentially methylated region. The figure visualizes raw RRBS methylation levels for 2 exemplary samples (APL sample 10 and CD34 sample A) together with the estimated methylation levels for all APL and control samples at the CACNA1B promoter.

The methylome in APL. (A) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering based on raw DNA methylation levels. The color grid beneath visualizes the sample characteristics. The clustering is based on raw RRBS methylation values. (B) Distribution of methylation levels in APL and control samples. The stacked bar plots show the distribution of raw RRBS methylation levels of CpG sites covered in all samples for APL and control samples, respectively. The raw methylation levels (middle) are encoded by colors ranging from green (low methylation close to 0) to red (high methylation close to 1). Methylation levels were increased in APL samples (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test: P < .001). (C) Chromosomal distribution of covered CpG-clusters and DMRs. The plot shows the genome-wide distribution of CpG sites covered by RRBS together with DMRs detected between APL and controls. (D) Smoothed scatter plot of methylation values for APL versus healthy control samples. Colors represent the density of points ranging from red (high density) to blue (low density). Smoothed RRBS methylation levels were averaged for APL cells and controls. (E) Example of a differentially methylated region. The figure visualizes raw RRBS methylation levels for 2 exemplary samples (APL sample 10 and CD34 sample A) together with the estimated methylation levels for all APL and control samples at the CACNA1B promoter.

Raw methylation levels from CpG sites covered across all samples were used to perform unsupervised hierarchical clustering (Figure 1A). As expected, the samples formed 2 main clusters: one encompassing APL patient samples and the other encompassing hematopoietic progenitor cells and remission BM samples.6 We used the Infinium methylation bead array platform for large-scale validation of this result at single CpG resolution. Four APL patient samples and matched remission BM samples and one set of CD34+ cells/promyelocytes were analyzed with the 450K Infinium Methylation Bead Array platform. A close correlation existed for DNA methylation levels at single CpG resolution measured by RRBS and bead arrays (supplemental Figure 2A). As expected, a similar clustering pattern was observed (supplemental Figure 2B). Overall, APL samples exhibited a larger fraction of intermediately methylated (20%-80%) CpG sites and a smaller fraction of CpG sites with low methylation. The fraction of highly methylated (> 80%) CpG sites was not changed (Figure 1B). On a genome-wide scale, APL patient samples were therefore DNA hypermethylated compared with control samples.

For further analyses, we defined 26 849 CpG clusters within our RRBS data for subsequent methylation smoothing and DMR detection with CpG-cluster sizes ranging from 42-2682 bp and an average size of 343 bp. CpG clusters were spread across the whole genome (Figure 1C). Smoothed methylation values further underlined that APL patient samples showed genome-wide hypermethylation (Figure 1D). Similar results were obtained using bead array data (supplemental Figure 2C).

We also scanned the smoothed methylation levels within CpG clusters for differentially methylated regions between primary APL and control samples. All 3 control sample types were considered in the DMR finding process. Three separate analyses were performed, including APL versus CD34+/promyelocytes, APL versus remission BM, and APL versus all 3 control specimens combined. Approximately 90% of DMRs were found to be similarly deregulated in all 3 analyses, underscoring a strong APL-specific methylation signature. Because of this high degree of overlap, we subsequently focused on DMRs found in the comparison APL versus combined control specimens in following analyses. The comparison of APL and all control samples adjusted for sex yielded 1604 DMRs with sizes ranging from 11-1901 bp and an average size of 165 bp (Figure 1C). A sample DMR is shown in Figure 1E.

Approximately half of the DMRs detected with RRBS spanned at least 1 CpG site targeted by a bead array probe that allowed for extensive validation. Almost all DMRs that were found to be hypermethylated or hypomethylated with our RRBS analysis were also hypermethylated or hypomethylated in the Infinium Methylation Bead Array analysis, respectively (Figure 2A).

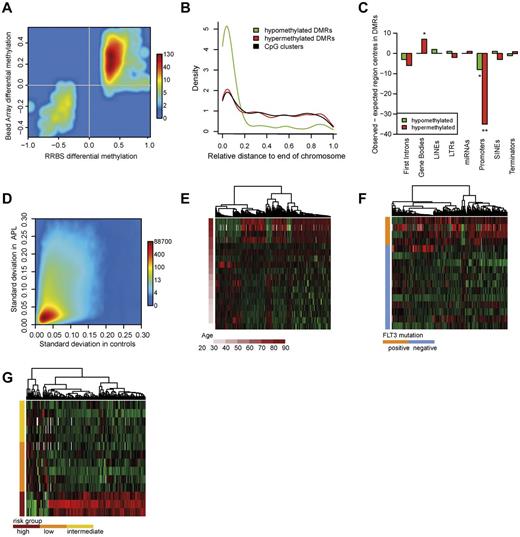

Characteristics of the APL methylome. (A) Methylation differences of CpG sites within DMRs were confirmed with Infinium 450K bead arrays. The smoothed scatter plot visualizes the methylation differences of APLs and controls in RRBS (x-axis) and the respective methylation differences in Infinium bead arrays (y-axis). A total of 851 DMRs were included in the analysis. (B) Chromosomal distribution of clusters and DMRs. The curves show the density distribution of hypomethylated and hypermethylated DMRs and CpG clusters in relation to their chromosomal position: 0 indicates chromosomal ends and 1 the centromeric region. Hypomethylated DMRs (green), hypermethylated DMRs (red), and CpG clusters (black) are shown. The distribution of DMRs is shifted toward chromosomal ends. (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test: P < .001). (C) Enrichment of genomic regions in DMRs. Briefly, the number of centers of a particular region of interest (eg, the gene promoter) that we could expect in DMRs under the assumption of uniform distribution (expected region centers) was subtracted from the number of region centers actually found in DMRs (observed region centers). The plot shows the differences of observed and expected region centers in hypomethylated DMRs (green bars) and in hypermethylated DMRs (red bars). Two-sided binomial test: significance levels of 1 × 10-2 (**), or 5 × 10-2 (*), respectively. (D) Standard deviation of methylation in APL and healthy controls. The plot shows the standard deviation values of smoothed methylation levels in APL and control samples, respectively. (E) Methylation of DMRs associated with age in APL. Heat map showing the methylation alterations within age-specific DMRs. Depicted DMRs exhibited at least 0.1% methylation difference per year (655 DMRs). (F) Methylation of DMRs associated with Flt3 mutational status. Heat map showing the methylation alterations within Flt3-mutation specific DMRs. Depicted DMRs exhibited at least 30% methylation difference between groups (317 DMRs). (G) Methylation of DMRs associated with risk group. Heat map showing methylation alterations within Sanz score–specific DMRs. Depicted DMRs exhibited at least 30% methylation difference between groups (173 DMRs).

Characteristics of the APL methylome. (A) Methylation differences of CpG sites within DMRs were confirmed with Infinium 450K bead arrays. The smoothed scatter plot visualizes the methylation differences of APLs and controls in RRBS (x-axis) and the respective methylation differences in Infinium bead arrays (y-axis). A total of 851 DMRs were included in the analysis. (B) Chromosomal distribution of clusters and DMRs. The curves show the density distribution of hypomethylated and hypermethylated DMRs and CpG clusters in relation to their chromosomal position: 0 indicates chromosomal ends and 1 the centromeric region. Hypomethylated DMRs (green), hypermethylated DMRs (red), and CpG clusters (black) are shown. The distribution of DMRs is shifted toward chromosomal ends. (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test: P < .001). (C) Enrichment of genomic regions in DMRs. Briefly, the number of centers of a particular region of interest (eg, the gene promoter) that we could expect in DMRs under the assumption of uniform distribution (expected region centers) was subtracted from the number of region centers actually found in DMRs (observed region centers). The plot shows the differences of observed and expected region centers in hypomethylated DMRs (green bars) and in hypermethylated DMRs (red bars). Two-sided binomial test: significance levels of 1 × 10-2 (**), or 5 × 10-2 (*), respectively. (D) Standard deviation of methylation in APL and healthy controls. The plot shows the standard deviation values of smoothed methylation levels in APL and control samples, respectively. (E) Methylation of DMRs associated with age in APL. Heat map showing the methylation alterations within age-specific DMRs. Depicted DMRs exhibited at least 0.1% methylation difference per year (655 DMRs). (F) Methylation of DMRs associated with Flt3 mutational status. Heat map showing the methylation alterations within Flt3-mutation specific DMRs. Depicted DMRs exhibited at least 30% methylation difference between groups (317 DMRs). (G) Methylation of DMRs associated with risk group. Heat map showing methylation alterations within Sanz score–specific DMRs. Depicted DMRs exhibited at least 30% methylation difference between groups (173 DMRs).

Genomic distribution of the APL-specific methylation signature

Aberrations at chromosomal ends such as 7p deletions have been associated with AML. Therefore, we investigated whether DNA methylation patterns are also targeted to chromosomal ends in APL.35 We plotted the chromosomal distribution of DNA methylation changes and the distribution of CpG clusters and investigated whether the DMR distribution was shifted toward chromosomal ends in relation to CpG-cluster distribution (Figure 2B). Aberrant DNA methylation was observed across all chromosomal regions, but was especially pronounced at chromosome ends. Surprisingly, hypomethylated DMRs were responsible for this pattern. These were especially enriched at the ends of chromosomes 5, 7, 9, and 17. Recent studies have established a correlation of subtelomeric hypomethylation with reduced telomere length.36 We analyzed telomere length in APL by quantitative PCR, but could not verify a correlation between hypomethylation and telomere length in APL (data not shown).

Both intragenic and intergenic regions were widely affected by differential methylation, mostly hypermethylation (Table 1). We investigated whether certain genomic regions were located in DMRs more (or less) frequently than statistically expected. Briefly, we determined the number of centers of a particular region of interest (eg, the gene promoter) that we could expect in DMRs under the assumption of uniform distribution (“expected region centers”). The number of expected region centers was then subtracted from the number of region centers actually found in DMRs (“observed region centers”). This analysis showed that gene bodies were significantly overrepresented in hypermethylated DMRs (Figure 2C). High gene-body methylation has been implicated in gene activation rather than transcriptional suppression.37 Gene promoters were not overrepresented in DMRs, and in fact were significantly underrepresented. Contrary to the conventional model of high promoter methylation in cancer, this indicates that, at least in APL, DNA hypermethylation is not specifically targeted only to gene promoters.

Analyzed and differentially methylated genomic regions

| Region . | Tested regions . | Differentially methylated . | Hypomethylated . | Hypermethylated . | Hyper- and hypomethylated . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First introns | 11 221 | 342 | 30 | 311 | 1 |

| Gene bodies | 4530 | 430 | 91 | 334 | 5 |

| LINEs | 292 | 15 | 3 | 12 | 0 |

| LTRs | 876 | 32 | 7 | 25 | 0 |

| miRNAs | 117 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Promoters | 13 846 | 386 | 13 | 372 | 1 |

| Satellites | 98 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| SINEs | 889 | 18 | 2 | 16 | 0 |

| Terminators | 1035 | 59 | 6 | 53 | 0 |

| Region . | Tested regions . | Differentially methylated . | Hypomethylated . | Hypermethylated . | Hyper- and hypomethylated . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First introns | 11 221 | 342 | 30 | 311 | 1 |

| Gene bodies | 4530 | 430 | 91 | 334 | 5 |

| LINEs | 292 | 15 | 3 | 12 | 0 |

| LTRs | 876 | 32 | 7 | 25 | 0 |

| miRNAs | 117 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Promoters | 13 846 | 386 | 13 | 372 | 1 |

| Satellites | 98 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| SINEs | 889 | 18 | 2 | 16 | 0 |

| Terminators | 1035 | 59 | 6 | 53 | 0 |

DNA methylation in APL is highly variable

Aberrant DNA methylation in cancer shows a high degree of variation across different samples.14 The reasons for this are unclear, but different pathogenetic mechanisms and clonal evolution in solid tumors might be responsible. In contrast to other cancers, the initiating event in APL is well known. Therefore, we analyzed the heterogeneity of DNA methylation in APL by comparing the standard deviation of methylation levels of APL samples and healthy controls (Figure 2D). Methylation levels in APL samples showed a higher variability compared with methylation levels in control samples. Control samples covered different states of hematopoiesis and DNA methylation differences during hematopoiesis have been described previously.1,38 Therefore, methylation variation in APL is high. To exclude that this finding occurred because of the overall higher methylation level of APL, we also investigated the relationship between average methylation and standard deviation for APL samples and controls. At similar average levels of DNA methylation, the variability was still higher in APL (supplemental Figure 3).

Several clinical parameters, including WBC count and platelet count before therapy (Sanz score), Flt3-ITD status, age, PML-RARα transcript type, and others,39,40 are used to identify APL subtypes. A recent study showed that the number of mutations in hematopoietic cells increases with age.41 In light of these findings, we estimated the effect that age had on methylation within a linear model. Most age-specific loci showed increased methylation with increasing age and a few loci showed progressive loss of DNA methylation (Figure 2E). Because Flt3 mutations frequently occur in APL, we examined whether Flt3-ITD+ patients showed a specific methylation pattern.40 Indeed, in Flt3-ITD+ patients, many loci showed hypermethylation compared with Flt3-ITD− patients (Figure 2F). Interestingly, patients with a high Sanz score also showed loci with accentuated hypermethylation compared with low- or intermediate-risk patients (Figure 2G). No spatial overlap was found for DMRs among the different clinical parameters. However, spatial overlap with disease-specific DMRs in approximately 20% of Flt3- and risk group–associated DMRs was seen. In patients who suffered early death (as an indicator of highly aggressive disease), we observed more hypermethylated than hypomethylated DMRs. No DNA methylation difference was found between the PML-RARα isoforms (supplemental Figure 4A-B).

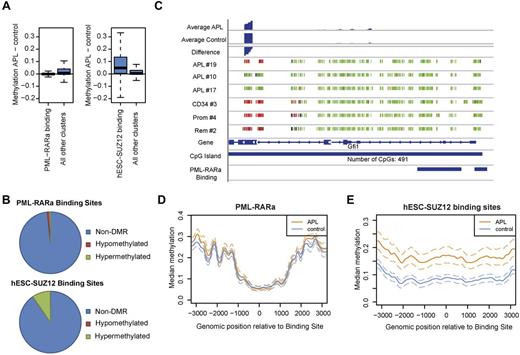

PML-RARα–binding sites do not coincide with DMRs

PML-RARα was found to recruit DNA methyltransferase activity to its target promoters.9,12 We therefore analyzed DNA methylation at PML-RARα binding sites using recently published ChIP-Seq data.24,25 The median methylation difference at PML-RARα sites between APL and control samples was close to zero (Figure 3A). Of 556 PML-RARα sites that could be evaluated, only 9 were differentially methylated, 6 of which were hypomethylated (Figure 3B). We also manually evaluated described bona fide PML-RARα targets42 to exclude that our finding was a result of a lack of data at these loci and, again, no preferential DNA hypermethylation was observed in bona fide PML-RARα targets such as DNMT3A, RUNX1, and RARα. Rather, some genes, such as Gfi1, even appeared to be hypomethylated in APL (Figure 3C and supplemental Figure 5). The previously evaluated PML-RARα target gene RARβ2 showed hypermethylation in 4 of 8 evaluable CpG sites (supplemental Figure 6).

PML-RARα binding protects against DNA methylation. (A) Distribution of methylation levels in PML-RARα– and SUZ12-binding sites compared with background methylation. The plot shows the distribution of methylation differences between APL and control samples within PML-RARα–binding sites (left) or SUZ12-binding sites (right) compared with nonbinding sites. PML-RARα–binding sites exhibited lower methylation than nonbinding sites in APL, P < .001. SUZ12-binding sites exhibited higher methylation than nonbinding sites in APL, P < .001.(B) Fractions of differentially methylated binding sites. Of 556 analyzed PML-RARα–binding sites, 9 were differentially methylated, 6 of which were hypomethylated. For SUZ12, 2228 binding sites could be evaluated. Of these, 216 exhibited differential methylation, with 214 of these hypermethylated. (C) DNA Methylation at the bona fide PML-RARα target Gfi1. Single CpG-site resolution methylation data were visualized. Each small vertical bar represents one CpG dinucleotide. The color encodes the degree of raw methylation ranging from green (low methylation = 0) to red (high methylation = 1).The number of CpGs contained in the respective CpG-island is shown at the bottom. At the top smoothed methylation values for APL and controls are shown with the bottom lane representing the methylation difference between the 2 groups (APL minus controls). (D) Methylation in and around PML-RARα–binding sites in APL cells and those from healthy controls. The curves visualize methylation levels of APL samples and control samples in and around PML-RARα–binding sites together with the 25% and 75% quantiles (dashed lines). (E) Methylation in and around SUZ12-binding sites in APL cells and those from healthy controls. The curves visualize methylation levels of APL samples and control samples around SUZ12-binding sites together with the 25% and 75% quantiles (dashed lines).

PML-RARα binding protects against DNA methylation. (A) Distribution of methylation levels in PML-RARα– and SUZ12-binding sites compared with background methylation. The plot shows the distribution of methylation differences between APL and control samples within PML-RARα–binding sites (left) or SUZ12-binding sites (right) compared with nonbinding sites. PML-RARα–binding sites exhibited lower methylation than nonbinding sites in APL, P < .001. SUZ12-binding sites exhibited higher methylation than nonbinding sites in APL, P < .001.(B) Fractions of differentially methylated binding sites. Of 556 analyzed PML-RARα–binding sites, 9 were differentially methylated, 6 of which were hypomethylated. For SUZ12, 2228 binding sites could be evaluated. Of these, 216 exhibited differential methylation, with 214 of these hypermethylated. (C) DNA Methylation at the bona fide PML-RARα target Gfi1. Single CpG-site resolution methylation data were visualized. Each small vertical bar represents one CpG dinucleotide. The color encodes the degree of raw methylation ranging from green (low methylation = 0) to red (high methylation = 1).The number of CpGs contained in the respective CpG-island is shown at the bottom. At the top smoothed methylation values for APL and controls are shown with the bottom lane representing the methylation difference between the 2 groups (APL minus controls). (D) Methylation in and around PML-RARα–binding sites in APL cells and those from healthy controls. The curves visualize methylation levels of APL samples and control samples in and around PML-RARα–binding sites together with the 25% and 75% quantiles (dashed lines). (E) Methylation in and around SUZ12-binding sites in APL cells and those from healthy controls. The curves visualize methylation levels of APL samples and control samples around SUZ12-binding sites together with the 25% and 75% quantiles (dashed lines).

PML-RARα might lead to DNA hypermethylation in its vicinity rather than at its target sites. To investigate this, we analyzed DNA methylation 3 kb around the center of PML-RARα–binding sites (Figure 3D). No hypermethylation was observed up to 3 kb upstream or downstream of PML-RARα–binding sites compared with healthy controls. PML-RARα thus appears to protect its binding sites from DNA hypermethylation.

SUZ12 binding sites from hESCs prime for DNA hypermethylation in APL

It is known that Polycomb sites in human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) are preferentially hypermethylated in human cancers.43 Binding of SUZ12 has also been associated with methylation in APL at a few examined loci.12 Using published SUZ12-binding sites from hESCs,44 we also found herein that hESC-SUZ12–binding sites were hypermethylated in APL (Figure 3A). Ten percent of hESC-SUZ12–binding sites directly overlapped with DMRs (Figure 3B). Hypermethylation was also found around hESC-SUZ12 binding in APL samples (Figure 3E).

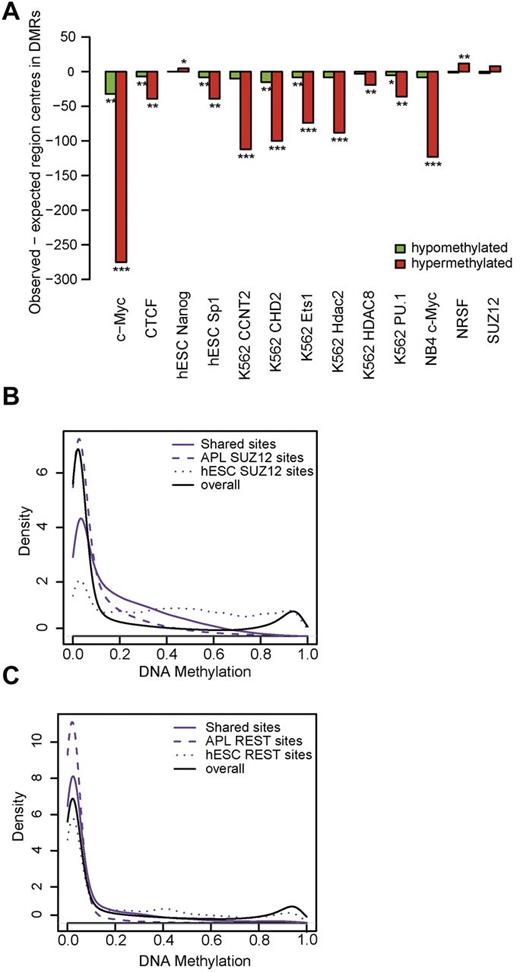

General underrepresentation of TFBSs in DMRs

The overlap of DMRs with published ChIP-sequencing data from ENCODE45 and binding motifs derived from the GenomeTrax (BIOBASE) database was then evaluated. We compared the number of transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) motifs expected in DMRs on random distribution with the number of actually observed TFBS in DMRs (Figure 4A). Almost all transcription factors were strongly underrepresented in DMRs. This was particularly true for c-myc ChIP-sequencing binding sites from NB4, hinting at a methylation protective role of c-myc in APL pathogenesis. Only a few transcription factor binding sites were actually overrepresented, and these included hESC-NRSF. NRSF, also known as REST, has been found to be methylation protective during mouse embryonic development.46 Interestingly, one study also established an interaction of REST with Polycomb group proteins, leading to repressive chromatin states.47

Transcription factor enrichment analysis and ChIP sequencing of SUZ12 and REST in patient blasts. (A) Presence of published transcription factor binding sites among DMRs. The bars visualize the differences of observed and expected region centers in hypomethylated DMRs (green bars) and in hypermethylated DMRs (red bars). Two-sided binomial test: significance levels of 1 × 10-10 (***), 1 × 10-2 (**), or 5 × 10-2, respectively. (B) Methylation in SUZ12-binding sites. The density distribution of methylation levels in an APL patient sample within SUZ12 ChiP-Seq–binding sites is depicted. Methylation levels within ChiP-Seq data from the same APL patient and published binding sites from hESCs were analyzed. Solid lines indicate binding sites common to both hESCs and APL (shared sites); dashed lines, binding sites found only in APL (APL SUZ12 sites); dotted lines, binding sites found only in hESCs (hESC SUZ12 sites); and black solid line, genome-wide background methylation. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test: methylation in hESC SUZ12 > methylation in shared SUZ12 sites, P < .001. Methylation in shared SUZ12 sites > methylation in APL SUZ12 sites, P < .001. (C) Methylation in REST-binding sites. The density distribution of methylation levels in an APL patient sample within REST-binding sites is depicted. ChiP-Seq data from the same APL patient and published binding sites from hESCs were analyzed. Solid lines indicate binding sites common to both hESCs and APL cells (shared sites); dashed lines, binding sites found only in APL cells (APL REST sites); dotted lines, binding sites found only in hESCs (hESC REST sites); and black solid line, genome-wide methylation as a reference. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test: methylation in hESC REST > methylation in shared REST sites, P < .001. Methylation in shared REST sites > methylation in APL REST sites, P < .001.

Transcription factor enrichment analysis and ChIP sequencing of SUZ12 and REST in patient blasts. (A) Presence of published transcription factor binding sites among DMRs. The bars visualize the differences of observed and expected region centers in hypomethylated DMRs (green bars) and in hypermethylated DMRs (red bars). Two-sided binomial test: significance levels of 1 × 10-10 (***), 1 × 10-2 (**), or 5 × 10-2, respectively. (B) Methylation in SUZ12-binding sites. The density distribution of methylation levels in an APL patient sample within SUZ12 ChiP-Seq–binding sites is depicted. Methylation levels within ChiP-Seq data from the same APL patient and published binding sites from hESCs were analyzed. Solid lines indicate binding sites common to both hESCs and APL (shared sites); dashed lines, binding sites found only in APL (APL SUZ12 sites); dotted lines, binding sites found only in hESCs (hESC SUZ12 sites); and black solid line, genome-wide background methylation. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test: methylation in hESC SUZ12 > methylation in shared SUZ12 sites, P < .001. Methylation in shared SUZ12 sites > methylation in APL SUZ12 sites, P < .001. (C) Methylation in REST-binding sites. The density distribution of methylation levels in an APL patient sample within REST-binding sites is depicted. ChiP-Seq data from the same APL patient and published binding sites from hESCs were analyzed. Solid lines indicate binding sites common to both hESCs and APL cells (shared sites); dashed lines, binding sites found only in APL cells (APL REST sites); dotted lines, binding sites found only in hESCs (hESC REST sites); and black solid line, genome-wide methylation as a reference. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test: methylation in hESC REST > methylation in shared REST sites, P < .001. Methylation in shared REST sites > methylation in APL REST sites, P < .001.

REST and SUZ12 binding in APL protect their binding sites from aberrant DNA methylation

To further investigate the association between transcription factor binding and DNA methylation, we performed ChIP sequencing of SUZ12 and REST in APL blasts from one patient. The distribution of hESC- and APL-binding sites for both SUZ12 and REST was analyzed with regard to the associated DNA methylation levels (Figure 4B-C). REST- and SUZ12-binding sites that were only found in APL cells, but not in hESCs, were associated with low DNA methylation. This finding is consistent with a prior report that REST protects its binding sites from methylation in mouse ESCs.46 SUZ12- and REST-binding sites that were only present in hESCs, but not in APL cells, were associated with increased levels of DNA methylation. Contrary to other cell types, the overlap between REST and SUZ12 binding in APL cells was small at only 6%.47 Twelve percent of PML-RARα–binding sites overlapped with APL REST-binding sites, whereas only a 2% overlap was observed with APL SUZ12-binding sites (supplemental Table 2).

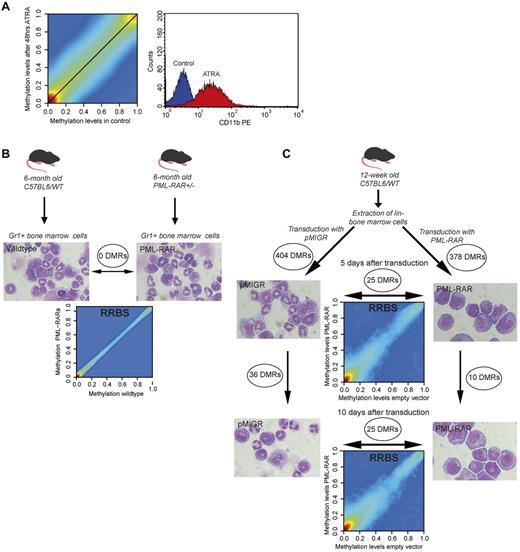

Absence of DNA methylation changes in ATRA-treated primary patient blasts and preleukemic PML-RARα knock-in mice

Fresh APL BM blasts were obtained and ATRA treatment was performed according to established protocols. Forty-eight hours of ATRA treatment led to successful differentiation, as evidenced by high CD11b levels in FACS analyses (Figure 5A). Nevertheless, no visible changes in DNA methylation occurred (Figure 5A).

Lack of methylation changes in ATRA-treated APL patient blasts and PML-RARα–expressing murine hematopoietic progenitor cells. (A) Smoothed scatter plot of methylation values for ATRA-treated versus untreated APL patient blasts. Colors encode the density of points ranging from red (high density) to blue (low density). Cells were treated with 1μM ATRA or incubated with no treatment for 48 hours and analyzed by CD11b-FACS and cytospins for differentiation. A histogram plot of CD11b levels for mock-treated (blue) versus ATRA-treated blast cells (red) is also shown. (B) Analysis of methylation patterns in preleukemic PML-RARα knock-in mice. Gr1+ BM cells were extracted from heterozygous PML-RARα knock-in mice (n = 3) and age- and sex-matched C57BL6 wild-type mice (n = 3). Gr1+ sorting yielded a population consisting of granulocytes and hematopoietic progenitor cells. Final magnification was 100× (Axio Imager M1; Zeiss). Genomic DNA was extracted and subjected to RRBS analysis. The smoothed scatter plot compares the averaged methylation levels for knock-in and wild-type mice. No DMRs could be found between groups. (C) Retroviral transduction of hematopoietic progenitor cells with PML-RARα. BM was extracted from 12-week-old C57BL6 wild-type mice (n = 20) and sorted for Lin− BM cells. Lin− BM cells were then transduced with either PML-RARα or empty vector, sorted for green fluorescent protein expression, and then further cultivated for 10 days (cells from n = 10 per group). Genomic DNA was extracted on days 0, 5, and 10 and subjected to RRBS analysis. Cells were also analyzed using Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospins. Final magnification was 100× (Axio Imager M1; Zeiss). Smoothed scatter plots comparing methylation levels of PML-RARα and empty vector–transduced cells are shown. Indicated are the numbers of DMRs obtained by comparison of the respective samples.

Lack of methylation changes in ATRA-treated APL patient blasts and PML-RARα–expressing murine hematopoietic progenitor cells. (A) Smoothed scatter plot of methylation values for ATRA-treated versus untreated APL patient blasts. Colors encode the density of points ranging from red (high density) to blue (low density). Cells were treated with 1μM ATRA or incubated with no treatment for 48 hours and analyzed by CD11b-FACS and cytospins for differentiation. A histogram plot of CD11b levels for mock-treated (blue) versus ATRA-treated blast cells (red) is also shown. (B) Analysis of methylation patterns in preleukemic PML-RARα knock-in mice. Gr1+ BM cells were extracted from heterozygous PML-RARα knock-in mice (n = 3) and age- and sex-matched C57BL6 wild-type mice (n = 3). Gr1+ sorting yielded a population consisting of granulocytes and hematopoietic progenitor cells. Final magnification was 100× (Axio Imager M1; Zeiss). Genomic DNA was extracted and subjected to RRBS analysis. The smoothed scatter plot compares the averaged methylation levels for knock-in and wild-type mice. No DMRs could be found between groups. (C) Retroviral transduction of hematopoietic progenitor cells with PML-RARα. BM was extracted from 12-week-old C57BL6 wild-type mice (n = 20) and sorted for Lin− BM cells. Lin− BM cells were then transduced with either PML-RARα or empty vector, sorted for green fluorescent protein expression, and then further cultivated for 10 days (cells from n = 10 per group). Genomic DNA was extracted on days 0, 5, and 10 and subjected to RRBS analysis. Cells were also analyzed using Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospins. Final magnification was 100× (Axio Imager M1; Zeiss). Smoothed scatter plots comparing methylation levels of PML-RARα and empty vector–transduced cells are shown. Indicated are the numbers of DMRs obtained by comparison of the respective samples.

Aberrant DNA methylation was not directly associated with PML-RARα binding in primary patient samples. Therefore, we analyzed preleukemic PML-RARα knock-in mice to determine the effect of PML-RARα expression on DNA methylation in the absence of leukemia.17 We extracted BM from 6-month-old PML-RARα knock-in mice (n = 3) and matched wild-type controls (n = 3). FACS analysis of blood and BM confirmed the preleukemic status (data not shown). Myeloid cells were enriched by MACS using an anti-Gr1 Ab to yield a population that consisted of granulocytes and myeloid progenitor cells (Figure 5B).

PML-RARα knock-in mice and age- and sex-matched wild-type controls did not form separate clusters in an unsupervised hierarchical clustering (data now shown). No systematic differences were observed comparing average smoothed methylation levels between knock-in mice and controls (Figure 5B). With a P threshold of 1% (as used for APL patients), we could not identify any DMRs. With a 5% P threshold, only one short DMR was detected.

To further investigate the direct effects of PML-RARα on DNA methylation, we transduced Lin− murine BM cells. Expression of PML-RARα on retroviral transduction led to the characteristic differentiation block and enhanced proliferation. This was evident after 5 days of culture and became even more pronounced after 10 days of culture. In vitro culture and the process of retroviral transduction affected DNA methylation of several hundred genomic regions after 5 days (Figure 5C). Further changes were observed after 10 days (Figure 5C). However, very few differences in DNA methylation were observed between empty vector versus PML-RARα–transduced cells (Figure 5C). There were no changes after 5 or 10 days (in each case, there were 25 DMRs with only 11 bp of overlap between days 5 and 10). Murine DMRs were compared with those from human APL patients using the University of California Santa Cruz liftover software and no overlap was detected.29

Discussion

Aberrant DNA methylation is a common feature of cancer.13 The origin of aberrant DNA methylation and its involvement in the pathogenesis of cancer are, however, still incompletely understood. Mutated transcription factors such as PML-RARα have been associated with specific DNA methylation patterns in leukemia.6,10 The question of whether cancer initiation is directly associated with aberrant DNA methylation or if aberrant DNA methylation occurs at a later stage of disease pathogenesis bears important implications, for example, for epigenetic therapy. In the present study, we focused on PML-RARα, the driving oncogene for APL. Although PML-RARα provides the defining leukemia-initiating step, secondary events of genetic and presumably epigenetic nature are required for leukemogenesis. These features render PML-RARα suitable for studying the sequence of events between genetic mutations as a first hit and the occurrence of DNA methylation patterns.

The results of the present study provide evidence that PML-RARα–induced phenotypical characteristics (eg, a differentiation block) occur independently of differential DNA methylation at PML-RARα–binding sites. Contrary to prior results showing that PML-RARα recruits DNMTs to target promoters, we could not substantiate hypermethylation at PML-RARα target genes in primary patient samples.9,12 Earlier studies focused on few CpGs because of the lack of genome-wide PML-RARα–binding sites. In addition, most findings were based on cell culture experiments.9,12 Furthermore, our findings are consistent with recent genome-wide studies showing that PML-RARα is associated with open chromatin regions.48

Nevertheless, our results suggest a directive process behind aberrant DNA methylation, because we found a core set of differentially methylated regions in APL patients. Moreover, selective targeting of aberrant DNA methylation to chromosomal ends was evident. Aberrant PML body formation might be responsible, because PML binding to chromosomal ends has been established previously.36,49 Further investigation will be necessary to establish the exact mechanism.

The present data suggest that consistent DNA methylation changes are associated with leukemogenesis but are not directly initiated by PML-RARα binding. Other leukemogenesis-associated transcription factor binding sites, such as those of c-myc, were also spared from DNA methylation changes. Actual APL SUZ12- and REST-binding sites were associated with low methylation levels, whereas sites that showed dissociation of REST and SUZ12 between hESCs and APL cells were found in regions of particularly high methylation. This is consistent with previous reports showing that transcription factor binding protects from methylation.46 In this model, Polycomb proteins and REST would pre-mark genomic regions for subsequent de novo methylation.

Our findings in human APL specimens were corroborated by functional studies in patient blasts and mice: ATRA treatment of patient blasts did not result in short-term methylation changes, even though differentiation had occurred. Retroviral transduction of PML-RARα into Lin− BM cells led to a specific phenotype after 5 and 10 days in culture, whereas no changes in DNA methylation levels were found. Furthermore, preleukemic murine BM with consistent expression of PML-RARα for 6 months did not exhibit a specific DNA methylation phenotype.

Interestingly, phenotypic variations of APL, for example, those caused by Flt3-ITD mutations or a high risk status (Sanz score), were associated with specific DNA methylation patterns. These data suggest that later events in leukemogenesis and phenotypic features of the disease are closely associated with specific DNA methylation occurrence. Our data are therefore consistent with an evolution of aberrant DNA methylation during disease pathogenesis. What are the implications of these data for leukemogenesis? Our data suggest that PML-RARα as an oncogenic transcription factor initiates leukemogenesis in a DNA methylation–independent manner. The APL-specific DNA methylation pattern seems to occur via indirect mechanisms that are induced by PML-RARα but not directly related to its function on its genomic targets. Loss of protective transcription factor binding rather than direct DNMT recruitment might lead to aberrant DNA methylation. In this model, aberrant DNA methylation patterns would then constitute a secondary event in leukemogenesis.

PML-RARα binding induces a specific gene-expression profile and specific states of histone modification patterns at target genes.24 Prior studies also suggest that it is involved in the silencing process of important hematopoietic transcription factor pathways such as the PU.1 pathway.25 Histone modifications are more easily reversible than DNA methylation changes. Therefore, the lack of association between PML-RARα binding and DNA methylation changes may provide the rationale for the immediate differentiating effects of ATRA in APL therapy.

The results of the present study have clinical implications. Repressive histone modifications that prevent ATRA effects in other leukemia subtypes might be overcome by drugs that modulate histone modifications on a global scale rather than modulating DNA methylation.50 Our data provide evidence that PML-RARα initiation of leukemogenesis occurs independently of DNA methylation. Therefore, aberrant transcription factor effects might be overcome by chromatin-modifying or -inhibiting enzymes rather than by DNA-demethylating therapy.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Thomas Sternsdorf for providing the retroviral PML-RARα construct.

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grants Mu1328/8-1 and 9-1 and the National Genome Research Network-Plus LeukemiaNet (01GS0873).

Authorship

Contribution: T.S., C.R., K.H., F.R., and C.M.-T. designed the research; C.R., K.H., H.U.K., M.L., and M.D. performed the bioinformatics analyses; T.S., C.R., S.G., I.S., N.D., and S.A.-S. performed the experiments; A.W. and M.S. performed the sequencing; E.L., W.-K.H., T.B., and W.E.B. collected the patient APL samples and clinical data; P.S. purified healthy CD34+ cells; and all authors contributed to the manuscript writing process.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Dr Carsten Müller-Tidow, Department of Medicine A, Hematology and Oncology, University of Münster, Domagkstr 3, 48129 Münster, Germany; e-mail: muellerc@uni-muenster.de.

References

Author notes

T.S. and C.R. contributed equally to this work.