Abstract

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is characterized by deregulated engulfment of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) by BM macrophages, which are activated presumably by systemic inflammatory hypercytokinemia. In the present study, we show that the pathogenesis of HLH involves impairment of the antiphagocytic system operated by an interaction between surface CD47 and signal regulatory protein α (SIRPA). In HLH patients, changes in expression levels and HLH-specific polymorphism of SIRPA were not found. In contrast, the expression of surface CD47 was down-regulated specifically in HSCs in association with exacerbation of HLH, but not in healthy subjects. The number of BM HSCs in HLH patients was reduced to approximately 20% of that of healthy controls and macrophages from normal donors aggressively engulfed HSCs purified from HLH patients, but not those from healthy controls in vitro. Furthermore, in response to inflammatory cytokines, normal HSCs, but not progenitors or mature blood cells, down-regulated CD47 sufficiently to be engulfed by macrophages. The expression of prophagocytic calreticulin was kept suppressed at the HSC stage in both HLH patients and healthy controls, even in the presence of inflammatory cytokines. These data suggest that the CD47-SIRPA antiphagocytic system plays a key role in the maintenance of HSCs and that its disruption by HSC-specific CD47 down-regulation might be critical for HLH development.

Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a syndrome with excessive immune activation characterized by deregulated engulfment of hematopoietic cells by macrophages in the BM. Patients with HLH display hemophagocytosis, pancytopenia, and various inflammatory symptoms, including high fever, acute liver failure, and splenomegaly.1-4 HLH is classified into primary HLH and secondary HLH. Primary HLH, also known as familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, shows clear familial inheritance or genetic causes, including mutations in the perforin (PRF1), MUNC13-4, syntaxin 11 (STX11), and RAB27A genes.5-9 In primary HLH, natural killer cells and/or cytotoxic T lymphocytes fail to eliminate the targets in response to inflammatory reactions, and the resulting sustained inflammatory responses induce deregulated activation of macrophages. In secondary HLH, macrophages are activated in association with infections and malignant disorders.4 The key pathogenic feature of HLH is hypercytokinemia including IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, and M-CSF, which may activate macrophages to engulf blood cells.3 These cytokines are produced mainly by natural killer cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes, and might stimulate BM macrophages to engulf erythrocytes, leukocytes, platelets, and their precursors in the BM.

The question is, if hypercytokinemia causes activation of macrophages to engulf blood cells, why does such activation occur specifically in BM macrophages and induce severe hypocellularity and pancytopenia? Engulfment is triggered by the binding of specific receptors on macrophages to their ligands. Receptors on macrophages include phosphatidylserine receptors and low-density lipoprotein-related protein (LRP).10-14 Lipopolysaccharide and calreticulin (CRT) are typical ligands for these macrophage receptors to induce a prophagocytic signal.14,15 The phosphatidylserine-phosphatidylserine receptor system predominantly serves as a prophagocytic signal for macrophages during apoptosis.13,16 In contrast, the CRT-LRP system also works on viable cells,14 so there must be a mechanism to prevent inadequate engulfment of viable cells. Self-recognition to prevent phagocytosis is regulated by the CD47 and signal regulatory protein α (SIRPA) interaction, and CD47-SIRPA signaling plays an important role in preventing phagocytosis of cells.17,18 Therefore, phagocytosis of viable cells is regulated by the balance of prophagocytic CRT-LRP and antiphagocytic CD47-SIRPA signals for macrophages, indicating that the balance of this signaling is deregulated in HLH.

CD47 is a member of the Ig superfamily that is ubiquitously expressed in hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells.17,18 CD47 interacts with SIRPA through its respective IgV-like domains.18 In contrast, SIRPA is a transmembrane protein that contains 3 Ig-like domains within the extracellular region. SIRPA is expressed in macrophages, myeloid cells, and neurons.18-21 The cytoplasmic region of SIRPA has immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs.18 Binding cell-surface CD47 with SIRPA on macrophages provokes inhibitory signals through phosphorylation of the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs of SIRPA, activating inhibitory tyrosine phosphatases such as SHP1 and SHP2.18 This signaling inhibits myosin assembly of macrophages, thereby inhibiting phagocytosis.18 The CD47-SIRPA self-recognition system is primarily used in RBC clearance to maintain homeostasis of the blood.22

Interestingly, this system also plays a critical role in engraftment of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in xenotransplantation. Transplantation of the BM of CD47-deficient mice could not rescue lethally irradiated wild-type mice,23 probably due to engulfment of CD47-deficient HSCs by BM macrophages that constitute the HSC niche.24,25 In addition, we have reported previously that polymorphism of the SIRPA IgV domain can modulate the binding affinity of mouse SIRPA to human CD47 and plays a decisive role in xenotransplantation of human HSCs into mice; NOD, a mouse line known to have very efficient engraftment of human hematopoiesis, has a SIRPA polymorphism that can recognize human CD47, and this binding produces inhibitory signaling for mouse macrophages not to engulf human HSCs.26

These previous data led us to hypothesize that the BM-specific macrophage activation in HLH is caused by disruption of the CD47-SIRPA self-recognition system. In the present study, we show that in HLH, inflammatory cytokines down-regulate CD47, especially at the HSC stage, which can provoke the engulfment of HSCs by macrophages.

Methods

Patients and samples

Supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) summarizes the clinical characteristics of the patients. During the period from October 2005 to April 2011, 24 patients were diagnosed with HLH. The diagnosis of HLH was made according to HLH-2004 diagnostic guideline27 and Tsuda-97.28 The median age was 36 years (range, 16-71). Etiologies were documented in 12 patients: EBV (n = 7), CMV (n = 1), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (n = 1), EBV+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (n = 1), defective PRF1 (n = 1), and adult onset Still disease (n = 1). The median hemoglobin level was 11.1 g/dL (range, 6.2-16.2), the median platelet count was 54.8 × 109/L (range, 4-187), and the median ferritin level was 4530 ng/mL (range, 620-44 020). Prednisolone-based treatment was used in 14 patients (58%), and HSC transplantation was performed in 2 patients (8%). BM and peripheral blood samples were obtained from healthy volunteers (n = 50) and HLH patients (n = 24). Cord blood samples from full-term deliveries and normal BM samples from normal volunteers were obtained based on informed consent (provided by Kyushu Block Red Cross Blood Center, Japan Red Cross Society). Informed consent was received for all donors in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The institutional review board of Kyushu University Hospital approved all experiments in this study.

Cell lines

A human acute promyelocytic leukemia cell line, NB4, which retains t(15;17), was obtained from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ). NB4 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Wako) containing 10% FBS (ICN).

Sequence alignment of the human SIRPA IgV domains

Genomic DNA was extracted by using QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN). The cording region of the SIRPA IgV domain was amplified by PCR. Genomic DNA was used as a PCR template in the following conditions: 10 minutes at 94°C, 30 cycles of 1 minute at 94°C, 1 minute at 60°C, 1 minute at 72°C, and 16 minutes at 72°C. PCR and sequencing primers were as follows: forward primer 5′-GCCTGCTTCTGGTGTGCATCCAGTC-3′ reverse primer 5′-GAGTTACTGTCACAAACCAGAGGC-3′. PCR products were cloned to the PCR 2.1-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and 10-25 clones were sequenced for every sample.

Abs, cell staining, and sorting

For analysis of cell-surface expression of SIRPA, we used SIRPA mAb (MBL International) and FITC-conjugated antimouse IgG (Beckman Coulter). For analysis of cell-surface expression of CD47, we used PE-conjugated anti-CD47 (BD Pharmingen). For sorting and analysis of CD34+CD38− and CD34+CD38+ cells, cells were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD34 (BD Pharmingen), PE-conjugated anti-CRT (Enzo Life Sciences), peridinin chlorophyll A protein-cy5.5–conjugated anti-CD47 (BD Pharmingen), and allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD38 (BD Pharmingen). For some experiments, cells were stained with allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD34, PE-conjugated anti-CD47, and PE-Cy7 conjugated anti-CD38 (all BD Pharmingen). Before sorting and analysis, lineage cells in cord blood cells were depleted using a lineage cell depletion kit (Miltenyi Biotec). CD34+CD38− and CD34+CD38+ cells were purified on a FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences).

The analysis procedures of CD34+CD38+ progenitor populations were described previously.29,30 BM mononuclear cells were first stained with PE-Cy5–conjugated lineage Abs, including anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD10, anti-CD19, anti-CD20, anti-CD14, anti-CD56, and glycophorin A (BD Pharmingen). Subsequently, cells were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD34 (BD Pharmingen), PE-conjugated anti-CD47 (BD Pharmingen), PE-Cy7–conjugated anti-CD123 (eBiosciences), and Pacific Blue–conjugated anti-CD45RA (Beckman Coulter) Abs. HSCs, common myeloid progenitors, granulocyte/macrophage progenitors, and megakaryocyte/erythrocyte progenitors were isolated as Lin−CD34+CD38−, Lin−CD34+CD38+CD123+CD45RA−, Lin−CD34+CD38+CD123+CD45RA+, and Lin−CD34+CD38+CD123−CD45RA− populations. The cells were analyzed and sorted with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer and a FACSAria 2 cell sorter (both BD Biosciences). The mean fluorescent intensity of CD47 and CRT was normalized and shown as a ratio to PBMCs from healthy donors.

Preparation of human macrophages from peripheral blood

In vitro phagocytosis assays for target cells

Peripheral blood–derived macrophages were prepared and incubated at 1.0 × 104 cells in 200 μL of RPMI 1640 medium in Falcon culture tubes (2058; BD Biosciences), and then 1.0-5.0 × 104 target cells were added to the tubes and incubated at 37°C for 2 hours. Before the addition of target cells to macrophage-containing tubes, cells were opsonized with CD34 Ab (sc-19621; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for CD34+CD38− cells and CD34+CD38+ cells isolated from normal and HLH BM by FACS sorting; CD13 Ab (sc-51522; Santa Cruz Biotechnolgoy) and CD33 Ab (sc-19660; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for NB4 cells; CD45 Ab (555480; BD Pharmingen) for lymphocytes; and neutrophils and glycophorin A Ab for RBCs (555569; BD Pharmingen). For activation of macrophages, cells were incubated with IFN-γ (100 ng/mL; R&D Systems) for 24 hours and with lipopolysaccharide (0.3 μg/μL) for 1 hour, and then harvested and washed 3 times with PBS before the addition of target cells. After coincubation with macrophages and target cells, they were mounted on cytospin preparations, and 1000 macrophages were tested to enumerate engulfing ones by a blinded observer. We calculated the phagocytic index using the following formula: phagocytosis index = phagocytic macrophages/number of macrophages.33

Inhibition of CD47 expression by siRNA

To investigate the effect on phagocytosis according to the expression level of CD47, CD47 expression of NB4 cells and CD34+ cord blood cells was down-regulated using siRNA. CD47 siRNA primers used were as follows: siRNA1, UAUACACGCCGCAAUACAGAGACUC and GAGUCUCUGUAUUGCGGCGUGUAUA; siRNA2, UAGAAGUCACAAUUAAACCAAGGCC and GGCCUUGGUUUAAUUGUGACUUCUA. The Nucleofector kit V and Human CD34 Cell Nucleofector kit (both Amaxa) were used to transfect siRNA and transfected NB4 cells, and lineage-depleted cord blood cells were incubated for 48 and 24 hours, respectively. NB4 cells and CD34+CD38− cells were then sorted depending on CD47 expression using the FACSAria 2 cell sorter (BD Biosciences), and these cells were used for in vitro phagocytic assays to determine the phagocytic index.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from normal and HLH BM. Reverse transcription was performed using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. CD47 and control gene 18srRNA primers were obtained from Applied Biosystems. Amplification, detection, and quantification were performed with the TaqMan ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). Data were calculated by the relative quantitation method (ΔΔCt) compared with 18srRNA as an internal control.

Measurement of cytokines by ELISA

Cytokines, including IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, and M-CSF, from HLH and normal blood serum were measured with ELISA. IFN-γ was measured with the IFN-γ Quantikine ELISA kit (DIF50; R&D Systems), TNF-α was measured with the TNF-α Quantikine HS ELISA kit (HSTA00D; R&D Systems), IL-6 was measured with the IL-6 Quantikine ELISA kit (D6050; R&D Systems), and M-CSF was measured with the M-CSF Quantikine ELISA kit (DMC00B; R&D Systems).

In vitro treatment of normal HSCs with inflammatory cytokines

To evaluated the effects of inflammatory cytokines on the expression level of CD47, lineage-depleted cord blood cells were purified by negative selection using the MACS lineage cell depletion kit (Miltenyi Biotec) and cultured in 24-well dish (3047; BD Biosciences) with 300 μL of X-VIVO10 supplemented with 10% FBS and cytokines as follows: SCF (50 ng/mL; R&D Systems), M-CSF (750 pg/mL; R&D Systems), IL-6 (200 pg/mL; R&D Systems), TNF-α (20 pg/mL; R&D Systems), and IFN-γ (250 pg/mL; R&D Systems). After 24 hours of culture, CD34+CD38− and CD34+CD38+ cells were sorted with the FACSAria 2 cell sorter (BD Biosciences), and these cells were used to determine the phagocytic index.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using jmp Version 9 software (SAS Institute). CD47 expression on CD34+CD38− cells, CD34+CD38+ cells, and bulk among the groups were compared with the Dunnett test. For siRNA experiments using NB4 cells and CD34+CD38− cells, phagocytic index was compared with a conventional t test. For phagocytic assays using CD34+CD38− cells from cord blood cells that had been cultured with inflammatory cytokines, P values were obtained by ANCOVA. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Changes in expression levels of SIRPA or SIRPA mutations do not occur in HLH patients

Several variants of the IgV domain in SIRPA (exon3 of SIRPA), where the CD47-binding site is located, have been reported in human.26,34 We first tested the possibility that the SIRPA polymorphism may influence the development of HLH. We examined the sequence alignment of SIRPA IgV domain of 50 Japanese healthy donors. Although many polymorphisms have been reported previously in the SIRPA IgV domain,26 we identified 2 variants (variants 1 and 2) in the present study (Figure 1A). There are 13 amino acid differences between these 2 variants as we have described,26 and their binding capacity to CD47 was equal.34 Twenty-four of 50 healthy donors were heterozygous for variants 1 and 2, 4 were homozygous for variant 1, and 22 were homozygous for variant 2 (Figure 1B). Similarly, we examined sequence alignment of SIRPA IgV domain of 15 HLH patients, in whom we identified variant 1 and variant 2 SIRPA IgV-encoding alleles, but no other variants or changes in the allele burden of variants 1 and 2 (Figure 1C). Furthermore, the expression level of SIRPA on the cell surface did not differ among HLH and normal BM cells (data not shown) and CD14+ cells (Figure 1D). These data suggest that alterations in SIRPA or its expression are not involved in the pathogenesis of HLH.

SIRPA mutation or changes of its expression level is not involved in pathogenesis of HLH. (A) Sequence alignment of SIRPA IgV domains (exon 3 of SIRPA) identified by sequence analysis from genomic DNA of 50 healthy donors. Two variants, which we have described previously,20 were identified in the present study. There are 13 amino acid differences between these 2 variants. (B) Distribution of genotype of SIRPA IgV domains in 50 healthy donors. PCR products were cloned to pCR 2.1-TOPO vector and 10-25 clones were sequenced for every sample: 24 were heterozygous for variants 1 and 2, 4 were homozygous for variant 1, and 22 were homozygous for variant 2. (C) Distribution of genotype of SIRPA IgV domains in 15 HLH patients (unique patient number [UPN] 1-15); 4 (UPN 2, 4, 7, and 14) were heterozygous of variants 1 and 2, 6 (UPN 3, 5, 8, 10, 11, and 12) were homozygous for variant 1, and 5 (UPN 1, 6, 9, 13, and 15) were homozygous for variant 2. There were no other variants or changes of SIRPA IgV domain in HLH patients. (D) Representative expression of surface SIRPA on CD14+ cells of control and HLH patients on FACS. There was no significant difference in the expression level of SIRPA in CD14+ monocytes between HLH and normal BM: The mean ± SD of CD47 fluorescence intensity was 116 ± 1.7 and 118 ± 9.6 in healthy controls (n = 5) and HLH patients (n = 5), respectively (P = .88).

SIRPA mutation or changes of its expression level is not involved in pathogenesis of HLH. (A) Sequence alignment of SIRPA IgV domains (exon 3 of SIRPA) identified by sequence analysis from genomic DNA of 50 healthy donors. Two variants, which we have described previously,20 were identified in the present study. There are 13 amino acid differences between these 2 variants. (B) Distribution of genotype of SIRPA IgV domains in 50 healthy donors. PCR products were cloned to pCR 2.1-TOPO vector and 10-25 clones were sequenced for every sample: 24 were heterozygous for variants 1 and 2, 4 were homozygous for variant 1, and 22 were homozygous for variant 2. (C) Distribution of genotype of SIRPA IgV domains in 15 HLH patients (unique patient number [UPN] 1-15); 4 (UPN 2, 4, 7, and 14) were heterozygous of variants 1 and 2, 6 (UPN 3, 5, 8, 10, 11, and 12) were homozygous for variant 1, and 5 (UPN 1, 6, 9, 13, and 15) were homozygous for variant 2. There were no other variants or changes of SIRPA IgV domain in HLH patients. (D) Representative expression of surface SIRPA on CD14+ cells of control and HLH patients on FACS. There was no significant difference in the expression level of SIRPA in CD14+ monocytes between HLH and normal BM: The mean ± SD of CD47 fluorescence intensity was 116 ± 1.7 and 118 ± 9.6 in healthy controls (n = 5) and HLH patients (n = 5), respectively (P = .88).

CD47 is down-regulated in the CD34+CD38− HSCs from HLH patients

We also evaluated the expression level of CD47 in the BM of HLH patients. As shown in Figure 2A, the control normal BM cells ubiquitously express CD47. Its expression levels were always high in the CD34+CD38− fraction that concentrates HSCs,35 in the CD34+CD38+ progenitor fraction, and in unfractionated cells that mainly contained mature cells. In the HLH BM, CD47 expression is down-regulated specifically in the CD34+CD38− HSC fraction compared with those in the progenitor and mature cell fraction by approximately 2-fold at the expression level (Figure 2A-B). To determine more precisely the expression of CD47 in progenitor fractions, we subfractionated CD34+CD38+ progenitors into common myeloid progenitor, granulocyte/macrophage progenitor, and megakaryocyte/erythrocyte progenitor populations.29 These progenitors had equivalent levels of CD47 (Figure 2C and supplemental Figure 1). The down-regulation of CD47 occurs in conjunction with the deterioration of HLH. Patient number 10, who suffered from adult onset primary HLH due to defective PRF1,36 had repeated episodes of HLH. The follow-up of this patient revealed that the expression levels of CD47 in HSCs normalized in remission, but its down-regulation occurred again at exacerbation of the disorder (Figure 2D). These data strongly suggest that the HSC stage-specific down-regulation of CD47 plays a critical role in HLH development.

CD47 expression is down-regulated specifically in the CD34+CD38− HSC fraction in HLH patients, reflecting the disease activity. (A) CD47 expression of CD34+CD38− cells, CD34+CD38+ cells and unfractionated BM cells in HLH patients and healthy controls. The number in each open circle corresponds to the unique patient number (UPN) of patients (supplemental Table 1). The horizontal bars in each group show mean values of the group. The level of CD47 on CD34+CD38− cells was significantly decreased compared with that on CD34+CD38+ cells and more mature cells. The CD47 expression index represents the relative surface CD47 level (median CD47 levels of analyzed cells/those in normal blood mononuclear cells). (B) Histograms of CD47 expression of BM cells in 4 representative HLH patients (UPN 1, 8, 9, and 12). (C) CD47 expression of CD34+CD38− HSC-enriched fraction and of each progenitor cell fraction in HLH patients (UPN 1, 4, 9, and 10) and healthy controls. All progenitor populations expressed equivalent levels of CD47, and CD47 expression was down-regulated only in HSC fraction. (D) Change of CD47 expression in UPN 10 during multiple episodes of HLH. Down-regulation of CD47 repeatedly occurred at exacerbation of HLH.

CD47 expression is down-regulated specifically in the CD34+CD38− HSC fraction in HLH patients, reflecting the disease activity. (A) CD47 expression of CD34+CD38− cells, CD34+CD38+ cells and unfractionated BM cells in HLH patients and healthy controls. The number in each open circle corresponds to the unique patient number (UPN) of patients (supplemental Table 1). The horizontal bars in each group show mean values of the group. The level of CD47 on CD34+CD38− cells was significantly decreased compared with that on CD34+CD38+ cells and more mature cells. The CD47 expression index represents the relative surface CD47 level (median CD47 levels of analyzed cells/those in normal blood mononuclear cells). (B) Histograms of CD47 expression of BM cells in 4 representative HLH patients (UPN 1, 8, 9, and 12). (C) CD47 expression of CD34+CD38− HSC-enriched fraction and of each progenitor cell fraction in HLH patients (UPN 1, 4, 9, and 10) and healthy controls. All progenitor populations expressed equivalent levels of CD47, and CD47 expression was down-regulated only in HSC fraction. (D) Change of CD47 expression in UPN 10 during multiple episodes of HLH. Down-regulation of CD47 repeatedly occurred at exacerbation of HLH.

Reduction of CD47 expression in HSCs in HLH patients results in engulfment of HSCs by macrophages

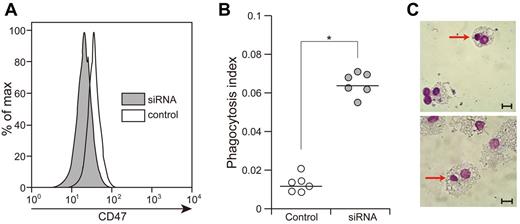

We also sought to investigate whether CD47 expression levels in target cells affect the efficiency of engulfment by macrophages. We first treated NB4, a human promyelocytic leukemia cell line, with 2 types of siRNAs targeting human CD47. siRNA1 showed a 72% reduction of CD47 expression in NB4 cells, whereas siRNA2 showed a 37% reduction (supplemental Figure 2A). We then quantitated the engulfment of macrophages by enumeration of the phagocytosis index (phagocytic macrophages/number of macrophages).22,33,35,37 In the culture of these cells with normal macrophages, rare control NB4 cells were engulfed by macrophages, whereas NB4 cells treated with siRNA1 or siRNA2 showed 5- and 2.5-fold increases in the phagocytosis index, respectively, which illustrates the efficiency of engulfment by macrophages (supplemental Figure 2B). Therefore, the engulfment of NB4 evoked by CD47 suppression occurs in a dose-dependent manner.

We treated purified normal CD34+CD38− HSCs with the siRNA1 for 24 hours and evaluated the phagocytosis index. As shown in Figure 3A, an approximately 30% reduction of the level of CD47 expression was observed in purified CD34+CD38− cells treated with siRNA1. The CD34+CD38− cells treated with siRNA1 became susceptible to phagocytosis, and showed 5.3-fold increase in the phagocytosis index compared with untreated CD34+CD38− cells (P < .01). Therefore, the reduction of CD47 in CD34+CD38− cells stimulates macrophages to engulf these cells.

Knocking down CD47 in CD34+CD38− cells induces their engulfment by macrophages. (A) Knockdown of CD47 expression in normal CD34+CD38− cells by siRNA for human CD47. Treatment of CD34+CD38− cells with siRNA for 48 hours induced 60% reduction of CD47 expression in these cells. (B) CD34+CD38− cells treated with the siRNA for human CD47 showed accelerated engulfment by normal macrophages. Vertical axis shows the phagocytosis index (phagocytosis index = phagocytic macrophages/number of macrophages) and the bars show mean value. *P < .01 by conventional t test. (C) Engulfment of CD34+CD38− cells treated with siRNA by normal macrophages (Giemsa staining). Scale bars indicate 10 μm.

Knocking down CD47 in CD34+CD38− cells induces their engulfment by macrophages. (A) Knockdown of CD47 expression in normal CD34+CD38− cells by siRNA for human CD47. Treatment of CD34+CD38− cells with siRNA for 48 hours induced 60% reduction of CD47 expression in these cells. (B) CD34+CD38− cells treated with the siRNA for human CD47 showed accelerated engulfment by normal macrophages. Vertical axis shows the phagocytosis index (phagocytosis index = phagocytic macrophages/number of macrophages) and the bars show mean value. *P < .01 by conventional t test. (C) Engulfment of CD34+CD38− cells treated with siRNA by normal macrophages (Giemsa staining). Scale bars indicate 10 μm.

We also investigated whether HSCs isolated from HLH patients are susceptible to phagocytosis by normal macrophages. We purified CD34+CD38− HSCs and CD34+CD38+ progenitors from HLH patients (patients number 4, 16, and 22) and healthy controls and evaluated the phagocytosis index. As shown in Figure 4A, in all 3 HLH patient samples, CD34+CD38− cells with a 40%-60% reduction of CD47 levels (Figure 2A) were actively engulfed by macrophages. In contrast, CD34+CD38+ cells of HLH patients showed a low phagocytic index, as was also observed in HSCs or progenitors in healthy controls (Figure 4A). Therefore, the efficiency of phagocytosis by macrophages is inversely correlated with the expression of CD47 of target cells even in human HLH samples, showing that a decrease of CD47 expression can induce engulfment of HSCs in HLH, at least in vitro.

The CD34+CD38− HSC fraction but not the progenitor population in HLH patients is sensitive to engulfment by macrophages. (A) Relationship between the level of CD47 expression and the phagocytosis index tested in vitro. CD34+CD38− cells and CD34+CD38+ cells from 3 HLH patients (unique patient number [UPN] 4, 16, and 22) and healthy controls were cultured with activated macrophages. CD47 expression index represents the relative surface CD47 level calculated as the median CD47 levels of analyzed cells/those in normal blood mononuclear cells. The bar shows the regression line; the coefficient of correlation value was −0.91. (B) The number of CD34+CD38− HSCs and CD34+CD38− progenitor cells in the BM of HLH patients (n = 14) and healthy controls (n = 6) are shown in the box and whisker plot. HLH patients had significantly decreased numbers of HSC and progenitor populations, but the magnitude of suppression of HSCs was more profound. The bottom and top of the boxes are the 25th and 75th percentile values. The bands in the middle of the boxes represent the 50th percentile (median). Error bars show 1 SD differences above and below the mean of the data. *P < .01 by conventional t test.

The CD34+CD38− HSC fraction but not the progenitor population in HLH patients is sensitive to engulfment by macrophages. (A) Relationship between the level of CD47 expression and the phagocytosis index tested in vitro. CD34+CD38− cells and CD34+CD38+ cells from 3 HLH patients (unique patient number [UPN] 4, 16, and 22) and healthy controls were cultured with activated macrophages. CD47 expression index represents the relative surface CD47 level calculated as the median CD47 levels of analyzed cells/those in normal blood mononuclear cells. The bar shows the regression line; the coefficient of correlation value was −0.91. (B) The number of CD34+CD38− HSCs and CD34+CD38− progenitor cells in the BM of HLH patients (n = 14) and healthy controls (n = 6) are shown in the box and whisker plot. HLH patients had significantly decreased numbers of HSC and progenitor populations, but the magnitude of suppression of HSCs was more profound. The bottom and top of the boxes are the 25th and 75th percentile values. The bands in the middle of the boxes represent the 50th percentile (median). Error bars show 1 SD differences above and below the mean of the data. *P < .01 by conventional t test.

Finally, we investigated whether HSCs were engulfed and reduced in number in HLH patients. We counted the number of CD34+CD38− cells in BM from healthy controls and HLH patients (Figure 4B). The frequencies of CD34+CD38− HSCs were significantly reduced in HLH BM (0.04% ± 0.02% of total nucleated cells) compared with those in normal adults (0.15% ± 0.09%). The number of nucleated cells in the BM was also reduced by approximately 50%. As a result, as shown in Figure 4B, the number of CD34+CD38− cells in HLH patients was reduced down to only 23% of those in healthy adults. Although the number of CD34+CD38+ cells were also reduced in the HLH patients (approximately 42% of healthy adults), the reduction was more profound in the CD34+CD38− fraction. The number of HSCs is reduced in the BM of HLH patient by phagocytosis that is evoked by HSC-specific reduction of CD47.

Inflammatory cytokines down-regulate CD47 expression and enhance the efficiency of engulfment of HSCs by macrophages

It has been shown that hypercytokinemia plays a critical role in the development of HLH. Consistent with previous results,3 HLH patient sera contained high levels of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, M-CSF, IFN-γ, and TNF-α (Figure 5A). We investigated whether these cytokines can affect the expression of CD47 in hematopoietic cells. Lineage-depleted cord blood cells were cultured with M-CSF (750 pg/mL), IL-6 (200 pg/mL), IFN-γ (250 pg/mL), and TNF-α (20 pg/mL) for 24 hours, and CD47 expression was evaluated in stem, progenitor, and mature cell fractions. The concentrations of inflammatory cytokines were compared with those of HLH patient sera. CD47 expression was down-regulated specifically in CD34+CD38− HSCs, whereas it did not change in CD34+CD38+ progenitors or unfractionated mature cells (Figure 5B). The down-regulation of CD47 expression in CD34+CD38− cells occurs in response to cytokines in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5C). The cells treated with cytokines were further tested for phagocytosis assays. As shown in Figure 5D, the expression level of CD47 in CD34+CD38− HSCs treated with inflammatory cytokines was inversely correlated with the phagocytosis index. These data suggest that inflammatory cytokines can down-regulate CD47 expression specifically in HSCs, inducing HSC-targeted engulfment by BM macrophages.

Inflammatory cytokines down-regulate CD47 specifically in CD34+CD38− cells to induce engulfment by macrophages. (A) Serum levels of M-CSF, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ from in patients by ELISA. These cytokines were extremely high in HLH samples compared with healthy controls. *P < .01; **P < .05 by conventional t test. (B) Changes of CD47 expression levels in normal CD34+CD38− HSCa and CD34+CD38+ progenitor cells in the presence of inflammatory cytokines. CD47 expression index represents the relative surface CD47 level calculated as median CD47 levels of analyzed cells/those in normal blood mononuclear cells. The HSC fraction, but not the progenitor fraction, showed down-regulated CD47 in response to cytokines. **P < .05 by conventional t test. (C) Suppression of CD47 in CD34+CD38− cells by graded doses of inflammatory cytokines. The concentration of inflammatory cytokines is shown on the right. (D) Engulfment of HSCs by macrophages in response to reduction of CD47 expression by cytokines in vitro. The CD47 expression index was inversely correlated with phagocytosis index. The bar shows the regression line; the coefficient of correlation value was −0.89.

Inflammatory cytokines down-regulate CD47 specifically in CD34+CD38− cells to induce engulfment by macrophages. (A) Serum levels of M-CSF, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ from in patients by ELISA. These cytokines were extremely high in HLH samples compared with healthy controls. *P < .01; **P < .05 by conventional t test. (B) Changes of CD47 expression levels in normal CD34+CD38− HSCa and CD34+CD38+ progenitor cells in the presence of inflammatory cytokines. CD47 expression index represents the relative surface CD47 level calculated as median CD47 levels of analyzed cells/those in normal blood mononuclear cells. The HSC fraction, but not the progenitor fraction, showed down-regulated CD47 in response to cytokines. **P < .05 by conventional t test. (C) Suppression of CD47 in CD34+CD38− cells by graded doses of inflammatory cytokines. The concentration of inflammatory cytokines is shown on the right. (D) Engulfment of HSCs by macrophages in response to reduction of CD47 expression by cytokines in vitro. The CD47 expression index was inversely correlated with phagocytosis index. The bar shows the regression line; the coefficient of correlation value was −0.89.

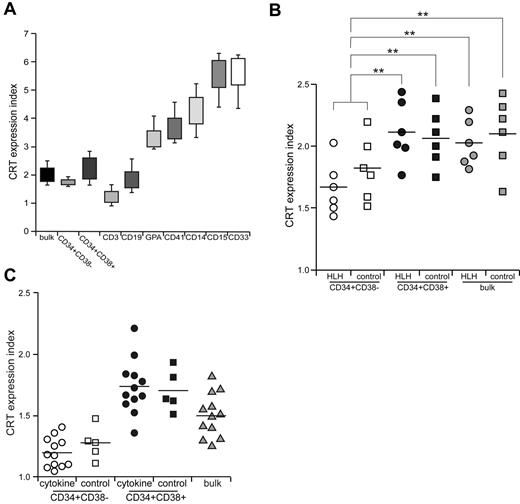

CRT, a dominant prophagocytic factor, is down-regulated in CD34+CD38− HSCs in both HLH patients and healthy controls

CRT is the major prophagocytic factor expressed on the cell surface, which binds to lipoprotein-related protein on cell surface of macrophages and stimulates their phagocytic activities.14 During apoptotic cell death, these cells are engulfed due to loss of CD47 expression and coordinated up-regulation of cell-surface CRT as thedominant prophagocytic signal.38 We evaluated the expression level of CRT in stem, progenitor, and mature cell fractions in HLH patients. In the healthy BM, CRT was highly expressed in mature myeloid cells, but at a very low level in lymphoid cells. Erythroblasts and megakaryocytes expressed intermediate levels of CRT. Interestingly, the expression level of CRT was very low in immature hematopoietic cells, including CD34+CD38− HSCs and CD34+CD38+ progenitor cell fractions (Figure 6A). CD34+CD38− HSCs expressed even lower levels of CRT compared with those in CD34+CD38+ progenitors (Figure 6B). In HLH patients, the expression of CRT was comparable to that in healthy controls: The CD34+CD38− HSC population expressed only a very low level of CRT (Figure 6B). We then cultured normal HSCs in the presence of inflammatory cytokines including M-CSF, IL-6, IFN-γ, and TNF-α for 24 hours, and the expression of CRT did not change in the HSC or progenitor populations (Figure 6C). Therefore, CRT is shut down at the HSC stage even in HLH patients, suggesting that the expression of CRT is not involved in engulfment of HSCs by macrophages.

CRT is not involved in the engulfment of HSCs in HLH. (A) CRT expression in normal hematopoietic cells. CRT expression index represents the relative surface CRT level calculated as median CRT levels of analyzed cells/those in normal blood mononuclear cells. Error bars show 1 SD differences. (B) CRT expression in CD34+CD38− HSCs, CD34+CD38+ progenitors, and unfractionated BM cells from HLH patients and healthy controls. The expression level of CRT was equivalent in HLH patients and healthy controls in all of these cell fractions. **P < .05 by conventional t test. (C) The effect of cytokines on CRT expression. CRT expression was not changed irrespective of incubation with cytokines in any of these cell fractions. Bars show the mean values.

CRT is not involved in the engulfment of HSCs in HLH. (A) CRT expression in normal hematopoietic cells. CRT expression index represents the relative surface CRT level calculated as median CRT levels of analyzed cells/those in normal blood mononuclear cells. Error bars show 1 SD differences. (B) CRT expression in CD34+CD38− HSCs, CD34+CD38+ progenitors, and unfractionated BM cells from HLH patients and healthy controls. The expression level of CRT was equivalent in HLH patients and healthy controls in all of these cell fractions. **P < .05 by conventional t test. (C) The effect of cytokines on CRT expression. CRT expression was not changed irrespective of incubation with cytokines in any of these cell fractions. Bars show the mean values.

Discussion

In HLH, cytopenia occurs in more than 80% of patients at disease presentation. The BM may present either hypocellularity or hypercellularity at the onset, but eventually becomes hypoplastic. This phenotype is thought to result mainly from suppression of hematopoiesis by elevated inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IFN-γ and from engulfment of hematopoietic cells by BM macrophages.39 The serum concentrations of these cytokine levels in HLH are usually quite higher than those with sepsis,40 suggesting that these extremely high levels of cytokines should be critical in the pathogenesis of HLH. In the present study, we show that HLH patients have low numbers of HSCs, and that HSCs from HLH patients down-regulate CD47 and are prone to be engulfed by macrophages more actively than normal HSCs. We also show that inflammatory cytokines can down-regulate the expression of CD47 selectively in HSCs, resulting in a disruption of self-recognition based on the CD47-SIRPA system to induce engulfment of HSCs by macrophages. Based on these data, we propose that the disruption of the CD47-SIRPA system plays a primary role in the development of HLH.

Macrophages function to clear foreign, aged, or damaged cells via phagocytosis, and this process is regulated by the balance between antiphagocytic and prophagocytic signals. The primary antiphagocytic and prophagocytic signals for macrophages to engulf nonapoptotic cells are the CD47-SIRPA and the LPR-CRT systems, respectively.14 Because in the present study, freshly isolated HSCs from HLH patients, but not from healthy controls, were engulfed by macrophages in vitro (Figure 4A), the balancing of this signaling should be altered in HLH.

Many polymorphisms have been detected in human SIRPA, especially in the ligand-binding IgV domain.26 In the present study, however, HLH patients did not have any specific polymorphisms of SIRPA. In addition, we could not find differences in the level of SIRPA expression between normal and HLH BM cells. We conclude that neither polymorphisms of SIRPA nor the change of its expression levels are involved in the pathogenesis of HLH.

Conversely, the expression of CD47 was significantly down-regulated specifically in the HSC fraction in HLH patients, but was not changed in progenitors and other mature cells (Figure 2A-C). The expression level of CD47 in HLH HSCs was approximately 50% at the protein level compared with that in normal HSCs. This level of reduction readily induced macrophage activation in vitro (supplemental Figures 2 and 4A). BM HSCs in HLH patients were reduced in number, presumably by engulfment, but were functionally normal, at least in terms of colony-forming capabilities in vitro (supplemental Figure 1B). The down-regulation of CD47 in HLH HSCs might be induced by high levels of serum inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, M-CSF, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, because incubation of normal HSCs, but not progenitors, with these cytokines induced down-regulation of CD47 in vitro in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5B-C), and rendered normal HSCs susceptible to engulfment by macrophages (Figure 5D).

It remains unclear by what mechanism only the HSC fraction is sensitive to cytokines to down-regulate CD47. Interestingly, in contrast to the CD47 protein, the CD47 mRNA levels were normal in HSCs in all 5 HLH patients analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR assays (not shown), so the down-regulation of CD47 could occur at the posttranscriptional level. In a recent study, Junker et al examined miRNA profiles from active and inactive lesions in multiple sclerosis patients, and found out that miRNA-34a, miRNA-155 and miRNA-326, the targets of which include human CD47, were up-regulated in active sclerosis lesions.41 These miRNAs reduce the expression of CD47 in brain-resident cells, promoting macrophages to engulf myelin. In the present study, we evaluated miRNA-34a, miRNA-155, and miRNA-326 expression in HSCs in HLH patients, but could not find any differences in the expression level of these miRNAs in HSCs from HLH patients and healthy controls (T.K., unpublished data, February 2010). Inflammatory cytokines did not induce the increased expression of these miRNAs (T.K., unpublished data, March 2010). It is critical to clarify the mechanism of CD47 down-regulation in the HSC fraction in future studies.

The expression of CRT on the cell surface is an important prophagocytic signal. When CRT binds to LPR on macrophages, LPR signaling immediately can stimulate macrophages to engulf the CRT-expressing cells.14,15 This “eat me” signal could antagonize the “do not eat me” signal mediated by the CD47-SIRPA interaction.42 Once apoptosis is initiated, CRT is up-regulated, phosphatidylserine is exposed to the cell surface, and CD47-SIRPA signaling is rendered ineffective, thereby permitting engulfment of target cells.42 In contrast to CD47, which is ubiquitously expressed in normal hematopoietic cells from HSCs to mature cell stages (Figure 2A), CRT is expressed mainly in myeloerythroid cells, but only at a low level in immature CD34+CD38− HSCs. Because recent studies have shown that macrophages are cellular components of HSC niches,24 down-regulation of CRT might be required for HSCs to stay intact at the niche. In contrast, mature myeloerythroid cells might be primed to be prophagocytic via sustained CRT expression, which enables macrophages to engulf these cells on activation by, for example, cytokines.

Previous studies have shown that the CD47-SIRPA system is critical to engraftment and maintenance of HSCs in vivo. We have reported that the reason that human HSCs engraft efficiently in the NOD mouse is that this strain has a polymorphic SIRPA capable of binding to human CD47.26 Blocking the CD47-SIRPA interaction by antihuman CD47 Fc inhibited the engraftment of human HSCs in the NOD-SCID xenograft model. In fact, HSCs have contact with macrophages in the vascular or reticuloendothelial niche,43,44 suggesting that self-recognition by macrophages could operate actively at the HSC niche. The impairment of antiphagocytic signals that involves HSCs specifically may be one of the primary mechanisms for the severe hypocellularity and pancytopenia seen in the BM of HLH patients.

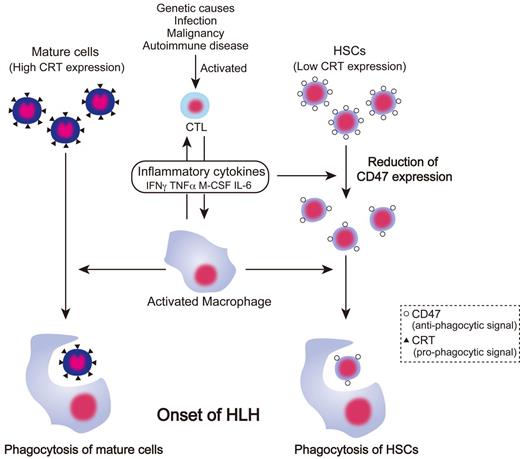

A schematic of the proposed pathogenesis of HLH based on the results of the present study is provided in Figure 7. In HLH, elevated inflammatory cytokines activate macrophages. Mature blood cells with high levels of CRT expression might be readily ingested by macrophages on activation compared with immature cells. The prophagocytic CRT is not expressed in HSCs; however, HSCs cannot compensate for the loss of mature cells in HLH by enhancement of hematopoiesis, because HSCs are also targeted by BM macrophages through inhibition of surface CD47 expression by inflammatory cytokines. The down-regulation of CD47 in HSCs abrogates the antiphagocytic SIRPA signal, resulting in active engulfment of HSCs by macrophages, presumably at the HSC niche. Therefore, hemophagocytosis in HLH occurs by at least 2 independent pathways mediated by CRT or CD47.

Pathogenesis of HLH based on antiphagocytic and prophagocytic signaling. In HLH, cytotoxic T lymphocytes are activated by genetic abnormality, infection, malignancy, and autoimmune disease, and then produce inflammatory cytokines and activate macrophages. Activated macrophages engulf mature cells such as RBCs, platelets, and granulocytes, which are susceptible to phagocytosis because of high expression of prophagocytic CRT. In contrast, inflammatory cytokines suppress hematopoiesis by their direct toxic effects and down-regulate CD47 expression on HSCs, resulting in a decreased threshold of antiphagocytic signals. Therefore, HSCs were engulfed by activated macrophages, causing the BM of HLH patients to become hypoplastic, thereby exacerbating pancytopenia.

Pathogenesis of HLH based on antiphagocytic and prophagocytic signaling. In HLH, cytotoxic T lymphocytes are activated by genetic abnormality, infection, malignancy, and autoimmune disease, and then produce inflammatory cytokines and activate macrophages. Activated macrophages engulf mature cells such as RBCs, platelets, and granulocytes, which are susceptible to phagocytosis because of high expression of prophagocytic CRT. In contrast, inflammatory cytokines suppress hematopoiesis by their direct toxic effects and down-regulate CD47 expression on HSCs, resulting in a decreased threshold of antiphagocytic signals. Therefore, HSCs were engulfed by activated macrophages, causing the BM of HLH patients to become hypoplastic, thereby exacerbating pancytopenia.

We have reported previously that in HLH patients, activated macrophages and monocytes produce a high level of cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α, whereas activated T cells produce IFN-γ and M-CSF.3 These cytokines may cause the down-regulation of CD47 in HSCs that further activate macrophages. Therefore, to trigger HLH development, activation of both acquired and innate immune systems might be required. Nonetheless, our present data highlight the importance of CD47-SIRPA axis in the development of HLH, by which the HSC, the source of all blood cells, becomes the target for engulfment. Accordingly, our results suggest that the CD47-Fc protein that can bind to SIRPA on activated macrophages may be able to suppress the deregulated engulfment of HSCs in HLH. Understanding the mechanism of HSC-specific down-regulation of CD47 will be critical to the development of future therapeutic approaches for HLH.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Kyushu Block Red Cross Blood Center for providing umbilical cord blood samples.

This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan (to K.A. and K.T.); a grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare in Japan (to K.A.); the Takeda Science Foundation (to K.T.); and the Cell Science Research Foundation (to K.T.).

Authorship

Contribution: T.K. and K.T. coordinated the project, designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; K.K., T.Y., S.D., G.Y., and Y.K. performed the experiments; J.K. analyzed the data; Y.A. and N.H. provided technical advice; and T.M., H.I., T.T., and K.A. designed the experiments, reviewed the data, and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Katsuto Takenaka, MD, PhD, Department of Medicine and Biosystemic Science, Kyushu University Graduate School of Medical Sciences, 3-1-1 Maidashi, Higashi-ku, Fukuoka 812-8582, Japan; e-mail: takenaka@intmed1.med.kyushu-u.ac.jp.

![Figure 1. SIRPA mutation or changes of its expression level is not involved in pathogenesis of HLH. (A) Sequence alignment of SIRPA IgV domains (exon 3 of SIRPA) identified by sequence analysis from genomic DNA of 50 healthy donors. Two variants, which we have described previously,20 were identified in the present study. There are 13 amino acid differences between these 2 variants. (B) Distribution of genotype of SIRPA IgV domains in 50 healthy donors. PCR products were cloned to pCR 2.1-TOPO vector and 10-25 clones were sequenced for every sample: 24 were heterozygous for variants 1 and 2, 4 were homozygous for variant 1, and 22 were homozygous for variant 2. (C) Distribution of genotype of SIRPA IgV domains in 15 HLH patients (unique patient number [UPN] 1-15); 4 (UPN 2, 4, 7, and 14) were heterozygous of variants 1 and 2, 6 (UPN 3, 5, 8, 10, 11, and 12) were homozygous for variant 1, and 5 (UPN 1, 6, 9, 13, and 15) were homozygous for variant 2. There were no other variants or changes of SIRPA IgV domain in HLH patients. (D) Representative expression of surface SIRPA on CD14+ cells of control and HLH patients on FACS. There was no significant difference in the expression level of SIRPA in CD14+ monocytes between HLH and normal BM: The mean ± SD of CD47 fluorescence intensity was 116 ± 1.7 and 118 ± 9.6 in healthy controls (n = 5) and HLH patients (n = 5), respectively (P = .88).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/120/19/10.1182_blood-2012-02-408864/4/m_zh89991298820001.jpeg?Expires=1765891312&Signature=bdqE6fywFBzgCN38iLmewsGNk~-Yifti8OzYt7KFTDUNcWq~aj5jO~NMlYKa9A4R6ZxYgjEZseMzKhvHxdtz9Iwp67yYIBc5VXR1i8bezBFBRsEQMPGIZB7qvOhHm~nwHuvYim2nlXBi0aLaDbYyHqNWeGc3ryXewQX8v9I6kK0AJM6V1WITpZOAT4Kz6fKBP32-PZXn2zt~VW3rxCEmTz6i~EC~tz-Qb0V2W40Gd0xCHAM8ub1X7yXAGjEsbQsO-PsIbkVhr4LKuJQ5Pj~dICgFr3Ou2DgfXW-lhnlXu2aawrLPV81MDmiLAUK2ClWezrRjQes4wYYg8eBuTElaXA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 4. The CD34+CD38− HSC fraction but not the progenitor population in HLH patients is sensitive to engulfment by macrophages. (A) Relationship between the level of CD47 expression and the phagocytosis index tested in vitro. CD34+CD38− cells and CD34+CD38+ cells from 3 HLH patients (unique patient number [UPN] 4, 16, and 22) and healthy controls were cultured with activated macrophages. CD47 expression index represents the relative surface CD47 level calculated as the median CD47 levels of analyzed cells/those in normal blood mononuclear cells. The bar shows the regression line; the coefficient of correlation value was −0.91. (B) The number of CD34+CD38− HSCs and CD34+CD38− progenitor cells in the BM of HLH patients (n = 14) and healthy controls (n = 6) are shown in the box and whisker plot. HLH patients had significantly decreased numbers of HSC and progenitor populations, but the magnitude of suppression of HSCs was more profound. The bottom and top of the boxes are the 25th and 75th percentile values. The bands in the middle of the boxes represent the 50th percentile (median). Error bars show 1 SD differences above and below the mean of the data. *P < .01 by conventional t test.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/120/19/10.1182_blood-2012-02-408864/4/m_zh89991298820004.jpeg?Expires=1765891312&Signature=3k2AQmV3kbazd2lovN628UbnqCxuDQ5BNscNUJtlA2UK1tBQb205woYx4CBowQT5OkqqP3z8Au~mIKLH9OQu2BMdIjBNQqA6pk2yn0WQ-4UEfA0~C2FsOf5WX~xj~nLEI8p0dHzbzQKUVXbeJFYoVi~6Qsb9FqUKqxW5QCjD~H69w-FBcvs8xOuzauJbRV4jCx-j1eMoMMGSkd~NoSGwWZ~Xr6G8NXFry-iPBO962cx5~IlRc6cA2fGWeJL1f0gKXe3sGaKiPZTJyA0sU8jQWySWXNRVwPyEVJH3aRQh-yPLv28GFbyZlbGEARSzwL-kGx-6pF~mK2gCmuWSEwGYYw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal