Abstract

During the last decade research has focused on the application of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) in the treatment of autoimmune disease. However, thorough functional characterization of these cells in patients with chronic autoimmune disease, especially at the site of inflammation, is still missing. Here we studied Treg function in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) and observed that Tregs from the peripheral blood as well as the inflamed joints are fully functional. Nevertheless, Treg-mediated suppression of cell proliferation and cytokine production by effector cells from the site of inflammation was severely impaired, because of resistance to suppression. This resistance to suppression was not caused by a memory phenotype of effector T cells or activation status of antigen presenting cells. Instead, activation of protein kinase B (PKB)/c-akt was enhanced in inflammatory effector cells, at least partially in response to TNFα and IL-6, and inhibition of this kinase restored responsiveness to suppression. We are the first to show that PKB/c-akt hyperactivation causes resistance of effector cells to suppression in human autoimmune disease. Furthermore, these findings suggest that for a Treg enhancing strategy to be successful in the treatment of autoimmune inflammation, resistance because of PKB/c-akt hyperactivation should be targeted as well.

Introduction

Since their discovery 15 years ago,1 it is now well established that CD25+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) are indispensable for immune homeostasis and self-tolerance. Tregs suppress the activation, proliferation, and effector functions of a wide range of immune cells via multiple mechanisms.2 FOXP3 has been identified as a master transcription factor, controlling both Treg development and functionality.3,4 In addition, human Tregs can be identified by high CD25 and low IL-7 receptor (CD127) expression.5,6 A critical role of Tregs in controlling autoimmune responses is demonstrated in various animal models of autoimmune disease.7 Furthermore, lack of functional Tregs leads to severe, systemic autoimmunity in humans.8,9

Because of their unique function, Tregs are considered important for the treatment of autoimmune disease, and several strategies are now being explored to target these cells for therapeutic purposes.10 However, there is still an ongoing debate whether the numbers and/or function of Tregs are changed in patients suffering from chronic autoimmune inflammation.11 In rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and multiple sclerosis, similar Treg numbers,12,13 or even enhanced numbers in RA,14 were observed in peripheral blood (PB) of patients compared with healthy controls (HCs). Thus, it appears that Treg numbers are not reduced in patients suffering from autoimmune inflammation. In addition, it remains unclear whether Treg function is impaired; some studies report reduced functioning of Tregs in PB of patients,12,13,15 whereas others have found no difference.14,16

In addition to these discrepancies concerning Treg numbers and function in the periphery, characterization of Tregs functionality at the site of autoimmune inflammation in humans is missing. High levels of Tregs have been found at the inflammatory sites in patients with arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease and these cells can suppress CD4+CD25− effector cells in vitro.17 Also at the site of inflammation in juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), one of the most common childhood autoimmune diseases, we have previously shown that Tregs are present in high numbers and suppress proliferation of CD4+CD25− effector cells in vitro.18 However, in vivo inflammation persists despite the large numbers of Tregs present, suggesting that these cells are defective in their ability to control the ongoing autoimmune response. This may result from the local proinflammatory environment, because in vitro experiments have shown that pro-inflammatory cytokines can affect both Treg function15,19-21 as well as effector T-cell responses.22,23 These data suggest that increasing Treg numbers or enhancing function for therapeutic purposes might be less effective in a chronic inflammatory environment. However, ex vivo data from patients with autoimmune disease are required to clarify the role of Tregs at the site of inflammation in humans.

Here, we studied Treg function at the site of inflammation in patients with JIA and compared their inhibitory potential to Tregs from PB of both patients and HCs. With this approach, we show that Tregs from inflamed joints demonstrate efficient suppressive capacity similar to Tregs from HCs, but control of effector cell proliferation and cytokine production is severely impaired, because of resistance of effector T cells to suppression. This unresponsiveness to suppression is, at least partially, caused by hyperactivation of protein kinase B (PKB)/c-akt and can be restored by selectively inhibiting PKB/c-akt activation. Taken together, these findings identify resistance of effector cells to suppression and, more specifically, enhanced PKB/c-akt activation of effector cells as a potential new target in the treatment of autoimmune inflammation.

Methods

Patients and healthy controls

Thirty-four patients with oligo articular (OA) and 3 with extended OA JIA, according to the revised criteria for JIA,24 were included in this study. All patients had active disease and underwent therapeutic joint aspiration at the time of sampling. Patients were between 5 and 18 years of age and were either untreated or treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), methotrexate (MTX), or both at the time of inclusion. Informed consent was received from parents/guardians or from participants directly when they were > 12 years of age. Twenty-seven volunteers from the laboratory with no history of autoimmune disease were included as HCs. The study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University Medical Center Utrecht (UMCU) and performed according to the principles expressed in the Helsinki Declaration.

Cell isolation

From JIA patients, synovial fluid (SF) was collected during therapeutic joint aspiration, and, at the same time, blood was drawn via veni puncture or intravenous drip. Blood was collected from HCs via veni puncture. Synovial fluid mononuclear cells (SFMCs) and PBMCs were isolated using Ficoll Isopaque density gradient centrifugation (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB) and were used either directly, or frozen in FCS (Invitrogen) containing 10% DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) until further experimentation.

Cell culture conditions

Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2mM l-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin, and 10% human AB serum or 10% FCS (all obtained from Invitrogen) in round-bottom 96-well plates (Nunc). Cells were stimulated with 1.5 μg/mL plate-bound anti-CD3 (clone OKT3; eBioscience) and cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Suppression assay

Total SFMCs or PBMCs were used as effector cells and cultured at 200.000 or 100.000 cells per well in 200 or 100 μL culture volume. CD4+ cells were isolated by magnetic cell sorting, using a CD4 T Lymphocyte Enrichment Set (BD Biosciences), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Subsequently, CD4+CD25+CD127low Tregs were sorted by flow cytometry on FACS Aria (BD Biosciences; supplemental Figure 1A, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Tregs were cocultured with effector cells at a 1:8 and 1:4 ratio. To control for cell density, effector cells instead of Tregs were added at a 1:4 ratio. In some experiments, PKB/c-akt inhibitor VIII (0.1μM; Calbiochem) was added from the start of culture. At day 4, proliferation of effector cells was analyzed or supernatant was collected to measure cytokine production.

Analysis of cell proliferation

To measure proliferation, effector cells were labeled with 2μM CFSE (Invitrogen) for 10 minutes at 37°C and extensively washed before use in suppression assays. At day 4, proliferation of effector cells was analyzed by flow cytometry by gating on CFSE+ cells. Proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was measured by subsequently gating on CD3+ cells, followed by gating on CD4+ and CD8+ cells, respectively.

Detection of cytokines in culture supernatant, peripheral blood, and SF

Supernatant was collected from suppression assays, stored at −80°C and processed within 1 month. Plasma was obtained by centrifugation of PB at 150g and SF at 980g for 10 minutes and stored at −80°C. Cytokine concentrations were measured with the Bio-Plex system in combination with the Bio-Plex Manager Version 4.0 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories), which employs the Luminex technology as previously described.25

Suppression assay with sorted memory and naive effector T cells

To study suppression of naive and memory effector cells, CD4+ cells were isolated by magnetic cell sorting, using a CD4 T Lymphocyte Enrichment Set (BD Biosciences, according to the manufacturer's instructions), and subsequently CD4+CD25+CD127low Tregs, CD4+CD25− total effector T cells, CD4+CD25−CD45RA+CD45RO− naive effector T cells, and CD4+CD25−CD45RA−CD45RO+ memory effector T cells were sorted by flow cytometry on FACS Aria (BD Biosciences). Effector T cells (25 000 cells) were cultured in 75 μL culture volume. Irradiated (3500 rad), autologous PBMCs (30 000 cells) depleted of CD3+ cells by magnetic cell sorting with anti–human CD3 particles (BD Biosciences, according to the manufacturer's instructions) were used as APCs. Tregs were added at a 1:2 ratio to effector cells and at day 5 proliferation of effector cells was analyzed and supernatant collected to measure cytokine production.

Suppression assay with sorted APCs and effector T cells

To study suppression of synovial T cells in the presence of PB- or SF-derived APCs, CD4+CD25+CD127low Tregs, CD3+ effector T cells, and CD3− APCs were sorted by flow cytometry on FACS Aria (BD Biosciences). CFSE labeled CD3+ effector T cells (100 000 cells) were cultured together with 100 000 unlabeled CD3− APCs in the presence of Tregs at a 1:4 and 1:8 ratio. At day 4, proliferation of effector cells was analyzed.

TGFβ suppression assay

To investigate suppression of SFMCs and PBMCs by TGFβ, CFSE-labeled SFMCs/PBMCs were cultured in the presence or absence of 40 ng/mL recombinant human TGFβ1 (Koma Biotech). In some experiments, PKB/c-akt inhibitor VIII (0, 0.01, 0.1, and 1μM; Calbiochem) was added from the start of culture. Cells were cultured for 4 or 5 days and proliferation of CD4+ T cells was analyzed by gating on CD3+ cells and subsequently on CD4+ cells. To study the effect of TNFα and IL-6 on TGFβ-mediated suppression, cells were untreated or pre-treated overnight with TNFα (50 ng/mL), IL-6 (100 ng/mL) or both, CFSE labeled and cultured in the presence or absence TNFα and IL-6 with or without TGFβ.

Methylation of FOXP3 Treg-specific demethylated region

To determine methylation of FOXP3 TSDR, male HC and JIA patients were included. DNA was isolated from sorted CD4+CD25+CD127low Tregs, using QiaAmp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN). Demethylation of the FOXP3 Treg-specific demethylated region (TSDR) was determined as previously described.26

Flow cytometry

To detect intracellular cytokine production, cells were stimulated for 4.5 hours with PMA (20 ng/mL; MP Biomedicals) and ionomycin (1 μg/mL; Calbiochem), with Golgistop (1/1500; BD Biosciences) added for the last 4 hours of culture. Before staining, cells were washed twice in FACS buffer (PBS containing 2% FCS [Invitrogen] and 0.1% sodium azide [Sigma-Aldrich]) and subsequently incubated with surface antibodies. After surface staining, cells were washed twice in FACS buffer and acquired directly, or fixed, permeabilized, and intracellularly stained using anti-human FOXP3 staining set (eBioscience, according to the manufacturer's instructions). To stain for phosphorylated PKB/c-akt, cells were fixed, permeabilized and stained using BD Phosflow method according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were acquired on FACSCalibur or FACSCanto II and analyzed using CellQuest Version 3.3 or FACS Diva Version 6.13 software, respectively (all BD Biosciences). All antibodies used for flow cytometry are described in supplemental Methods.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis of multiple groups, 1-way ANOVA, or in case of unequal variances, Kruskal-Wallis test was used. Bonferroni or Dunns posthoc test were used to compare between selected groups and Dunnet posthoc test to compare all groups versus a control group. To analyze paired patient samples, paired t test, or in case of unequal variances, Wilcoxon matched pairs test were used. P values < .05 were considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism Version 5.03 (Graphpad Software).

Results

Incomplete suppression of T-cell proliferation at the site of autoimmune inflammation

To study Treg function at the site of autoimmune inflammation, mononuclear cells were isolated from the inflamed synovium of patients with OA JIA. Consistent with previous reports18,19 Treg numbers were enriched at the site of inflammation in these patients (Figure 1A-B), whereas Treg levels in PB did not differ between patients and HC (Figure 1B). To investigate suppressive capacity, CD4+CD25+CD127low Tregs were sorted by flow cytometry5,6 (supplemental Figure 1A) and functionally analyzed in in vitro suppression assays. FOXP3 analysis consistently revealed a high percentage of FOXP3+ cells within the sorted CD4+CD25+CD127low population, which did not differ between SFMC (84% ± 9.1%) and PBMC of both patients (81% ± 3.9%) and HC (82% ± 7.6%). However, when synovial fluid (SF) derived Tregs were cocultured with effector cells and proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was analyzed, only a minor reduction in the percentage of proliferating cells was observed (Figure 1C) and this suppression of both CD4+ (Figure 1D) and CD8+ T-cell proliferation (Figure 1E) was significantly reduced in SFMCs (white bars) compared with PBMC of patients (gray bars) and HCs (black bars). In contrast, no difference in suppression was observed between PBMC from JIA patients and PBMCs from HCs. To control for cell density, effector cells instead of Tregs were added, which did not result in suppression (Figure 1D-E; +eff). These data demonstrate that, locally, at the site of autoimmune inflammation, proliferation of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells is poorly controlled by Tregs.

Treg-mediated suppression of T-cell proliferation is impaired at the site of autoimmune inflammation. (A-B) PBMCs and SFMCs were stained for CD4 and FOXP3 expression by flow cytometry. (A) Dotplots showing the percentage of FOXP3+ cells within CD4+ cells in paired PBMCs (left panel) and SFMC (right panel) of JIA patients, 1 representative of n = 16. (B) Accumulative data of the percentage of CD4+FOXP3+cells in PBMCs of HCs and paired PBMCs and SFMCs from JIA patients (n = 16), ***P < .001. (C-E) CD4+CD25+CD127low Tregs were sorted by flow cytometry and co-cultured with CFSE-labeled effector cells. At day 4, proliferation of CFSE+ effector cells was analyzed. (C) Proliferation of CD4+ (let panel) and CD8+ (right panel) SFMCs in the absence (open histograms) or presence of Tregs at 1 to 4 ratio (closed histograms). Percentages indicate the percentage of proliferating cells, 1 representative of n = 3. (D-E) Suppression of CD4+ (D) and CD8+ T-cell proliferation (E) in the presence of Tregs at a 1:8 and 1:4 ratio or additional effector cells (+eff) at a 1:4 ratio for PBMCs from HC (black bars), PBMCs from JIA patients (gray bars) and SFMCs from JIA patients (white bars). The results show percentage of suppression in the presence of Tregs or additional effector cells relative to effector cells cultured alone. Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 6 PBMCs HCs, n = 2 PBMCs JIA, and n = 3 SFMCs JIA, *P < .05, ***P < .001 compared with PBMCs (HCs).

Treg-mediated suppression of T-cell proliferation is impaired at the site of autoimmune inflammation. (A-B) PBMCs and SFMCs were stained for CD4 and FOXP3 expression by flow cytometry. (A) Dotplots showing the percentage of FOXP3+ cells within CD4+ cells in paired PBMCs (left panel) and SFMC (right panel) of JIA patients, 1 representative of n = 16. (B) Accumulative data of the percentage of CD4+FOXP3+cells in PBMCs of HCs and paired PBMCs and SFMCs from JIA patients (n = 16), ***P < .001. (C-E) CD4+CD25+CD127low Tregs were sorted by flow cytometry and co-cultured with CFSE-labeled effector cells. At day 4, proliferation of CFSE+ effector cells was analyzed. (C) Proliferation of CD4+ (let panel) and CD8+ (right panel) SFMCs in the absence (open histograms) or presence of Tregs at 1 to 4 ratio (closed histograms). Percentages indicate the percentage of proliferating cells, 1 representative of n = 3. (D-E) Suppression of CD4+ (D) and CD8+ T-cell proliferation (E) in the presence of Tregs at a 1:8 and 1:4 ratio or additional effector cells (+eff) at a 1:4 ratio for PBMCs from HC (black bars), PBMCs from JIA patients (gray bars) and SFMCs from JIA patients (white bars). The results show percentage of suppression in the presence of Tregs or additional effector cells relative to effector cells cultured alone. Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 6 PBMCs HCs, n = 2 PBMCs JIA, and n = 3 SFMCs JIA, *P < .05, ***P < .001 compared with PBMCs (HCs).

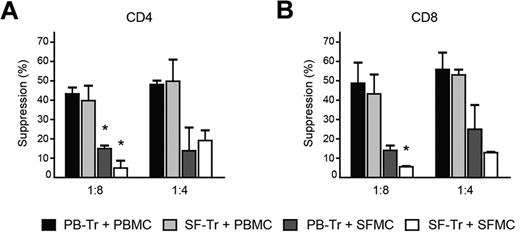

Deficient inhibition of cell proliferation is caused by resistance of effector cells to suppression

Both reduced functioning of Tregs as well as resistance of effector cells to suppression could play a role in the incomplete control of proliferation of effector cells from the site of inflammation.11 Phenotypical analysis of paired patient samples revealed that FOXP3 content per cell (mean fluorescence intensity [MFI]) was increased in SF derived CD4+CD25+CD127low Tregs compared with PB Tregs (supplemental Figure 1B-C). In addition, the percentage of cells with demethylated FOXP3 TSDR was not different for Tregs from SF (supplemental Figure 1D), suggesting that these cells do not display decreased stability. Other Treg markers, such as, the percentage of CTLA-4 expressing cells (supplemental Figure 1E) and both the percentage of GITR expressing cells as well as GITR content per cell (MFI; supplemental Figure 1F) were enhanced in SF CD4+FOXP3+ Tregs compared with PB Tregs. Thus, SF derived Tregs are stable and show enhanced expression of functional and activation markers suggesting that these cells are not deficient in their suppressive capacity. To confirm this, cross-over experiments were performed, in which SF derived Tregs (SF-Tregs) were cocultured with PB effector cells, and vice versa. When SF-Tregs were cocultured with PBMC (light gray bars), inhibition of CD4+ (Figure 2A) and CD8+ T-cell proliferation (Figure 2B) was completely comparable with suppression of PBMC by PB derived Tregs (PB-Tregs; black bars). Thus, Tregs from the site of inflammation show similar suppressive capacity to Tregs from PB and, in line with their phenotype, are not impaired in their suppressive function. However, when PB-Tregs were cocultured with SFMC (dark gray bars), the level of suppression of both CD4+ (Figure 2A) and CD8+ T-cell proliferation (Figure 2B) was markedly reduced compared with PB-Tregs cultured with PBMCs (black bars). Thus, in the presence of the same PB-Tregs, SFMCs are less responsive to suppression compared with PBMCs. Furthermore, this decrease in suppression was comparable with the decrease in suppression in cultures with both Tregs and effector cells from the site of inflammation (SF-Tregs + SFMCs; white bars). Therefore, the reduced suppression of cell proliferation observed in suppression assays with cells from the site of inflammation is attributable to unresponsiveness of effector cells to suppression.

Normal Treg function at the site of inflammation, but resistance of effector cells to suppression of cell proliferation. PBMCs and SFMCs were isolated from paired PB and SF samples from JIA patients. CD4+CD25+CD127low Tregs were sorted from PBMCs by flow cytometry and cocultured with CFSE-labeled PBMCs (black bars) or SFMCs (dark gray bars) at 1:8 and 1:4 ratios. Conversely, CD4+CD25+CD127low Tregs were sorted from SFMCs and cocultured with CFSE- labeled PBMCs (light gray bars) or SFMCs (white bars). At day 4, suppression of CD4+ (A) and CD8+ T-cell proliferation (B) was measured. The results show percentage of suppression in the presence of Tregs relative to effector cells alone. Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 2, *P < .05 compared with PB-Tr + PBMCs.

Normal Treg function at the site of inflammation, but resistance of effector cells to suppression of cell proliferation. PBMCs and SFMCs were isolated from paired PB and SF samples from JIA patients. CD4+CD25+CD127low Tregs were sorted from PBMCs by flow cytometry and cocultured with CFSE-labeled PBMCs (black bars) or SFMCs (dark gray bars) at 1:8 and 1:4 ratios. Conversely, CD4+CD25+CD127low Tregs were sorted from SFMCs and cocultured with CFSE- labeled PBMCs (light gray bars) or SFMCs (white bars). At day 4, suppression of CD4+ (A) and CD8+ T-cell proliferation (B) was measured. The results show percentage of suppression in the presence of Tregs relative to effector cells alone. Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 2, *P < .05 compared with PB-Tr + PBMCs.

Impaired control of cytokine production because of resistance of effector cells to suppression

Because we observed impaired Treg-mediated suppression of proliferation of effector T cells from the site of inflammation, we wondered whether suppression of other effector T-cell functions, such as cytokine production, was also impaired. After 4.5 hours PMA and ionomycin stimulation, CD4+ (top panel) and CD8+ (bottom panel) SFMCs (gated as shown in supplemental Figure 2A) not only express pro-inflammatory cytokines associated with autoimmune pathology, such as IL-17, TNFα, and IFNγ, but also IL-10 (Figure 3A) and expression of these cytokines was enhanced compared with paired PBMCs (supplemental Figure 2B-E). When suppression assays were performed using PBMCs from either HCs (Figure 3B) or JIA patients (Figure 3C), the amount of IL-5, IL-13, IL-10, TNFα, and IFNγ in the culture supernatant generally declined when Tregs were added at a 1:8 ratio and further decreased with higher numbers of Tregs present (1:4). No clear reduction in IL-17 levels was observed, consistent with previous reports.27,28 Adding additional effector cells instead of Tregs (+eff) did not result in a decrease in cytokine levels and Tregs cultured alone did not produce significant amounts of cytokines (data not shown). In contrast to these results with PBMCs from patients and HCs, cytokine levels in SFMC cultures (Figure 3D), did not decrease when Tregs were added at a 1:8 ratio and only modestly in the presence of Tregs at a 1:4 ratio. When the level of suppression at a 1:4 ratio was calculated for each cytokine, suppression was significantly lower in SFMCs (white bars) compared with PBMCs of both patients (gray bars) and HCs (black bars), whereas, again, there was no clear difference between PBMCs of JIA patients and PBMCs from HCs (Figure 3E). These data demonstrate that a broad range of cytokines produced by effector cells from the site of inflammation are insufficiently controlled by Tregs.

Effector cytokine production at the site of inflammation is insufficiently controlled, because of resistance of effector cells to suppression. (A) SFMCs were stained for cytokine expression by flow cytometry after 4.5 hours of PMA and Ionomycin stimulation. Dotplots showing the percentage of IL-10, IL-17, TNFα, and IFNγ-positive cells in CD4+ (top panel) and CD8+ cells (bottom panel), 1 representative of n = 4. Percentages indicate the percentage of positive cells from representative data, or, in upper line, average percentage ± SD from accumulative data of n = 4. (B-F) CD4+CD25+CD127low Tregs were sorted by flow cytometry and co-cultured with effector cells. At day 4, cytokine production in the culture supernatant was analyzed. (B-D) IL-5, IL-13, IL-10, IL-17, TNFα, and IFNγ levels in the absence (eff) or presence of Tregs at 1:8 and 1:4 ratios or additional effector cells (+eff) at a 1:4 ratio for PBMCs from HCs (B), PBMCs from JIA patients (C), and SFMCs from JIA patients (D). Data represent mean cytokine levels in pg/mL ± SEM of n = 4 PBMC HC, n = 4 PBMC JIA and n = 8 SFMC JIAs, *P < .05, ***P < .001 compared with effector cells (eff). (E-F) Percentage suppression of IL-5, IL-13, IL-10, IL-17, TNFα, and IFNγ production in the presence of Tregs at a 1:4 ratio relative to effector cells alone. (E) Percentage suppression in cocultures of Tregs and effector cells from PBMCs of HCs (black bars), PBMCs of JIA patients (gray bars), and SFMCs of JIA patients (white bars). Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 4 PBMC HC, n = 4 PBMC JIA and n = 8 SFMC JIA, **P < .01, ***P < .001. (F) Percentage suppression in cocultures of PB derived Tregs and PBMC (black bars), PB Tregs and SFMCs (white bars), or SF derived Tregs and PBMCs (gray bars). Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 4, **P < .01, ***P < .001 compared with PB-Tr + PBMCs.

Effector cytokine production at the site of inflammation is insufficiently controlled, because of resistance of effector cells to suppression. (A) SFMCs were stained for cytokine expression by flow cytometry after 4.5 hours of PMA and Ionomycin stimulation. Dotplots showing the percentage of IL-10, IL-17, TNFα, and IFNγ-positive cells in CD4+ (top panel) and CD8+ cells (bottom panel), 1 representative of n = 4. Percentages indicate the percentage of positive cells from representative data, or, in upper line, average percentage ± SD from accumulative data of n = 4. (B-F) CD4+CD25+CD127low Tregs were sorted by flow cytometry and co-cultured with effector cells. At day 4, cytokine production in the culture supernatant was analyzed. (B-D) IL-5, IL-13, IL-10, IL-17, TNFα, and IFNγ levels in the absence (eff) or presence of Tregs at 1:8 and 1:4 ratios or additional effector cells (+eff) at a 1:4 ratio for PBMCs from HCs (B), PBMCs from JIA patients (C), and SFMCs from JIA patients (D). Data represent mean cytokine levels in pg/mL ± SEM of n = 4 PBMC HC, n = 4 PBMC JIA and n = 8 SFMC JIAs, *P < .05, ***P < .001 compared with effector cells (eff). (E-F) Percentage suppression of IL-5, IL-13, IL-10, IL-17, TNFα, and IFNγ production in the presence of Tregs at a 1:4 ratio relative to effector cells alone. (E) Percentage suppression in cocultures of Tregs and effector cells from PBMCs of HCs (black bars), PBMCs of JIA patients (gray bars), and SFMCs of JIA patients (white bars). Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 4 PBMC HC, n = 4 PBMC JIA and n = 8 SFMC JIA, **P < .01, ***P < .001. (F) Percentage suppression in cocultures of PB derived Tregs and PBMC (black bars), PB Tregs and SFMCs (white bars), or SF derived Tregs and PBMCs (gray bars). Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 4, **P < .01, ***P < .001 compared with PB-Tr + PBMCs.

To study the role of Treg malfunctioning versus resistance of effector cells to suppression in the incomplete restriction of cytokine production, cross-over experiments were again performed (Figure 3F). In these assays, levels of suppression were clearly reduced when PB-Tregs were cocultured with SFMC (white bars) compared with PB-Tregs and PBMC co-cultures (black bars), demonstrating that effector cells from the site of inflammation show resistance to suppression of cytokine production. In contrast, the level of suppression was not affected in SF-Tregs and PBMC cultures (gray bars) compared with PB-Tregs and PBMC co-cultures, showing that SF-Tregs are not impaired in their cytokine suppressive capacity. Together our data show that, despite normal Tregs function, suppression of proliferation and cytokine production by cells from the site of autoimmune inflammation is impaired, because of resistance of effector cells to suppression.

Resistance of autoimmune effector cells to suppression is not caused by a memory phenotype

To mimic the in vivo situation as closely as possible, total mononuclear cells from the site of inflammation were used as effector cells in our assays. These SFMCs differ in cellular composition from PBMCs, which could contribute to the reduced responsiveness of these cells to suppression. Therefore, we carefully phenotyped paired SFMCs and PBMCs ex vivo by flow cytometry to gain insight into these differences in cellular constitution. We observed a significant increase in CD45RA−CD45RO+ memory cells in SFMC compared with PBMCs in both CD4+ (P < .01) and CD8+ T cells (P < .05; Figure 4A-C), which was accompanied by a decrease in the presence of CD45RA+CD45RO− naive cells. In mice, it has been shown that memory effector cells are more resistant to Treg-mediated suppression compared with naive cells.29 Therefore the high numbers of memory T cells present among effector cells from the site of inflammation might influence the responsiveness of these cells to suppression. To investigate this, we determined whether in our assays memory CD4+ T cells sorted from PBMCs of HCs are less responsive to suppression compared with naive cells (Figure 4D-E). We found that in the absence of Tregs (open histograms) CD25−CD45RA−CD45RO+ memory CD4+ effector cells (Figure 4D right panel) showed enhanced proliferation compared with CD25−CD45RA+CD45RO− naive effector cells (Figure 4D middle panel). However, on addition of Tregs (filled histograms), T-cell proliferation was significantly reduced in both memory and naive cells (Figure 4D). Similarly, IL-5, IL-13, TNFα, and IFNγ production was suppressed in both memory (white bars) and naive cells (gray bars), albeit to a slightly lower extend in memory cells compared with naive and total cells (Figure 4E black bars). In conclusion, consistent with previous results29 memory cells show reduced responsiveness to suppression, but, the difference in suppression is minimal and not comparable with the highly diminished suppression observed in SFMCs. Therefore, the general memory phenotype of cells at the site of autoimmune inflammation cannot explain their resistance to suppression.

Effector cells from the site of inflammation have a general memory phenotype, which is not the cause of their resistance to suppression. (A-C) Paired PBMCs and SFMCs were stained for CD45RA and RO expression by flow cytometry. (A) Dotplots showing the percentage of CD45RA−CD45RO+ memory cells in PBMCs (left panel) and SFMCs (right panel) CD4+ (top panel) and CD8+ T cells (bottom panel), 1 representative of n = 4. (B-C) Percentage of CD45RA−CD45RO+ memory (black bars) and CD45RA+CD45RO− naive cells (white bars) in CD4+ T cells (B) and CD8+ T cells (C) of paired SFMCs and PBMCs of n = 4. (D-E) CD4+CD25+CD127low Tregs were sorted by flow cytometry and cocultured with CFSE labeled total, naive, and memory effector T cells at a 1:2 ratio. At day 5, proliferation of CFSE+ effector cells (D) and cytokine production in the culture supernatant (E) was analyzed. (D) CFSE profile of CD4+CD25− total effector T cells (left panel), CD4+CD25−CD45RA+CD45RO− naive effector T cells (middle panel) and CD4+CD25−CD45RA−CD45RO+ memory effector T cells (right panel) cultured in the absence (open histograms) or presence of Tregs (closed histograms). Percentages indicate the percentage suppression of cell proliferation in the presence Tregs relative to effector cells alone, one representative of n = 2. (E) Percentage suppression of IL-5, IL-13, TNFα, and IFNγ production by CD4+CD25− total effector T cells (black bars), CD4+CD25−CD45RA+CD45RO− naive effector T cells (gray bars) and CD4+CD25−CD45RA−CD45RO+ memory effector T cells (white bars) in the presence of Tregs relative to effector cells alone. Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 2.

Effector cells from the site of inflammation have a general memory phenotype, which is not the cause of their resistance to suppression. (A-C) Paired PBMCs and SFMCs were stained for CD45RA and RO expression by flow cytometry. (A) Dotplots showing the percentage of CD45RA−CD45RO+ memory cells in PBMCs (left panel) and SFMCs (right panel) CD4+ (top panel) and CD8+ T cells (bottom panel), 1 representative of n = 4. (B-C) Percentage of CD45RA−CD45RO+ memory (black bars) and CD45RA+CD45RO− naive cells (white bars) in CD4+ T cells (B) and CD8+ T cells (C) of paired SFMCs and PBMCs of n = 4. (D-E) CD4+CD25+CD127low Tregs were sorted by flow cytometry and cocultured with CFSE labeled total, naive, and memory effector T cells at a 1:2 ratio. At day 5, proliferation of CFSE+ effector cells (D) and cytokine production in the culture supernatant (E) was analyzed. (D) CFSE profile of CD4+CD25− total effector T cells (left panel), CD4+CD25−CD45RA+CD45RO− naive effector T cells (middle panel) and CD4+CD25−CD45RA−CD45RO+ memory effector T cells (right panel) cultured in the absence (open histograms) or presence of Tregs (closed histograms). Percentages indicate the percentage suppression of cell proliferation in the presence Tregs relative to effector cells alone, one representative of n = 2. (E) Percentage suppression of IL-5, IL-13, TNFα, and IFNγ production by CD4+CD25− total effector T cells (black bars), CD4+CD25−CD45RA+CD45RO− naive effector T cells (gray bars) and CD4+CD25−CD45RA−CD45RO+ memory effector T cells (white bars) in the presence of Tregs relative to effector cells alone. Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 2.

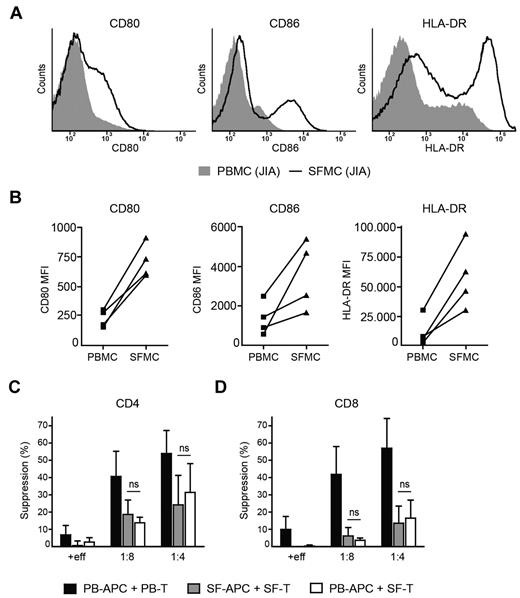

Resistance to suppression not caused by activation status of APCs

In RA patients it was demonstrated that monocytes from the site of inflammation showed a more activated phenotype that interfered with Treg-mediated suppression.20 Because the effector cell population in our experiments contained monocytes, we investigated whether changes in monocyte number and/or activation could explain the resistance of SFMCs to suppression. Monocytes were gated on forward side scatter (supplemental Figure 3) and phenotypically analyzed. No difference in percentage of monocytes between SFMCs (24% ± 12%) and PBMCs (23% ± 12%) was observed. However, in line with previous reports in RA20 and JIA,30 monocytes from SF displayed higher expression of CD80, CD86 and HLA-DR (Figure 5A-B), which could interfere with Treg inhibition. Therefore, we investigated whether in our in vitro suppression assays CD3− APCs contribute to resistance of SFMCs to suppression or whether this resistance solely resides within the CD3+ T-cell population (Figure 5C-D). When SF CD3− APCs were cocultured with SF CD3+ T cells in the presence of Tregs (gray bars), suppression of both CD4+ (Figure 5C) and CD8+ T-cell proliferation (Figure 5D) was again reduced compared with cultures containing PB-derived APCs and T cells (black bars). However, this reduction in suppression was similar when SF T cells were cocultured with PB APCs (white bars), clearly demonstrating that the resistance of SFMCs to suppression resides within CD3+ T cells and is not caused by enhanced activation of SF APCs.

Resistance of SFMCs to suppression is not caused by activation status of APCs. (A-B) Monocytes from paired PBMCs and SFMCs of JIA patients were analyzed for CD80, CD86, and HLA-DR expression by flow cytometry. (A) Histograms showing CD80 (left panel), CD86 (middle panel), and HLA-DR (right panel) fluorescence intensity in paired PBMCs (solid gray) and SFMCs (black line), one representative of n = 4. (B) MFI of CD80 (left panel), CD86 (middle panel) and HLA-DR (right panel) in monocytes from paired PBMCs and SFMCs of n = 4. (C-D) CD3+ T cells, CD3− APCs and CD4+CD25+CD127low Tregs were sorted by flow cytometry. PB T cells were cocultured with PB APCs (black bars) and SF T cells were cocultured with SF APCs (gray bars) or PB APCs (white bars) in the absence or presence of SF Tregs at a 1:8 and 1:4 ratio or additional effector cells (+eff) at a 1:4 ratio. Suppression of CD4+ (C) and CD8+ T cell proliferation (D) was measured. The results show percentage of suppression in the presence of Tregs or additional effector cells relative to effector cells alone. Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 3.

Resistance of SFMCs to suppression is not caused by activation status of APCs. (A-B) Monocytes from paired PBMCs and SFMCs of JIA patients were analyzed for CD80, CD86, and HLA-DR expression by flow cytometry. (A) Histograms showing CD80 (left panel), CD86 (middle panel), and HLA-DR (right panel) fluorescence intensity in paired PBMCs (solid gray) and SFMCs (black line), one representative of n = 4. (B) MFI of CD80 (left panel), CD86 (middle panel) and HLA-DR (right panel) in monocytes from paired PBMCs and SFMCs of n = 4. (C-D) CD3+ T cells, CD3− APCs and CD4+CD25+CD127low Tregs were sorted by flow cytometry. PB T cells were cocultured with PB APCs (black bars) and SF T cells were cocultured with SF APCs (gray bars) or PB APCs (white bars) in the absence or presence of SF Tregs at a 1:8 and 1:4 ratio or additional effector cells (+eff) at a 1:4 ratio. Suppression of CD4+ (C) and CD8+ T cell proliferation (D) was measured. The results show percentage of suppression in the presence of Tregs or additional effector cells relative to effector cells alone. Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 3.

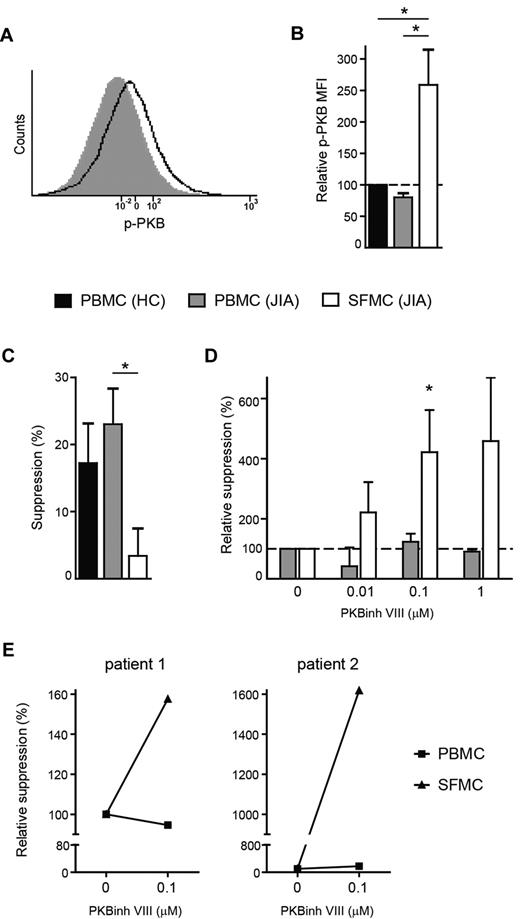

Hyperactivation of PKB/c-akt leads to resistance of effector cells to suppression

In addition to a general memory phenotype, CD4+ cells from the site of inflammation expressed higher levels of proliferation and activation markers compared with cells from PB (supplemental Figure 4), indicating that these cells are in a highly activated state. Because the PI3K-PKB/c-akt module is an important intracellular signaling pathway involved in T-cell activation31 and in mice hyperactivation of this pathway has been shown to induce resistance to suppression,32 we investigated whether hyperactivation of this pathway may be responsible for the resistance of SFMCs to suppression. First, we analyzed PKB/c-akt activation in paired SFMCs and PBMCs ex vivo by measuring the level of phosphorylated PKB/c-akt, a measure of activation status, by flow cytometry (Figure 6A). We found that compared with HC (black bars), the level of phosphorylated PKB/c-akt was unchanged in CD4+ T cells from the PB of JIA patients (gray bars), however, cells from the site of inflammation (white bars) clearly showed enhanced phosphorylated PKB/c-akt levels (Figure 6B). Thus, effector T cells at the site of autoimmune inflammation show increased levels of PKB/c-akt activation.

PKB/c-akt hyperactivation causes resistance of effector cells to suppression. (A-B) PBMCs and SFMCs were stained for phosphorylated PKB/c-akt expression by flow cytometry. (A) Histogram showing phosphorylated PKB/c-akt (p-PKB) fluorescence intensity in CD4+ T cells from paired PBMCs (solid gray) and SFMCs (black line), 1 representative of n = 3. (B) MFI of phosphorylated PKB/c-akt (p-PKB) in CD4+ T cells from paired PBMCs (gray bar) and SFMCs (white bar) of JIA patients relative to PBMC from HC (black bar). Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 3, *P < .05. (C-D) CFSE-labeled PBMCs and SFMCs were cultured in the presence or absence of recombinant human TGFβ1 (40 ng/mL) and increasing concentrations of PKB/c-akt inhibitor VIII (PKBinh VIII; 0, 0.01, 0.1, 1μM). At day 5, proliferation of CD4+ T cells was analyzed. (C) TGFβ-mediated suppression of CD4+ T-cell proliferation for PBMCs from HCs (black bars) and PBMCs (gray bars) and SFMCs (white bars) from JIA patients. The results show percentage of suppression in the presence of TGFβ relative to cells cultured without TGFβ. Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 3 PBMC HC, n = 4 PBMC JIA, and n = 5 SFMC JIA, *P < .05. (D) TGFβ-mediated suppression of CD4+ T cell proliferation for paired PBMCs (gray bars) and SFMCs (white bars) in the presence of increasing concentrations of PKB/c-akt inhibitor VIII. The data show the change in TGFβ-mediated suppression for each concentration of PKB/c-akt inhibitor relative to cultures without PKB/c-akt inhibitor. Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 3, *P < .05 compared with 0μM PKB/c-akt inhibitor VIII. (E) CD4+CD25+CD127low Tregs were sorted from SFMCs by flow cytometry and cocultured with CFSE-labeled PBMCs (squares) or SFMCs (triangles) at a 1:4 ratio in the presence or absence of PKB/c-akt inhibitor VIII (PKBinh VIII) (0.1μM). At day 4, Treg-mediated suppression of CD4+ T-cell proliferation was analyzed. The data show the change in Treg- mediated suppression in the presence PKB/c-akt inhibitor relative to cultures without PKB/c-akt inhibitor.

PKB/c-akt hyperactivation causes resistance of effector cells to suppression. (A-B) PBMCs and SFMCs were stained for phosphorylated PKB/c-akt expression by flow cytometry. (A) Histogram showing phosphorylated PKB/c-akt (p-PKB) fluorescence intensity in CD4+ T cells from paired PBMCs (solid gray) and SFMCs (black line), 1 representative of n = 3. (B) MFI of phosphorylated PKB/c-akt (p-PKB) in CD4+ T cells from paired PBMCs (gray bar) and SFMCs (white bar) of JIA patients relative to PBMC from HC (black bar). Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 3, *P < .05. (C-D) CFSE-labeled PBMCs and SFMCs were cultured in the presence or absence of recombinant human TGFβ1 (40 ng/mL) and increasing concentrations of PKB/c-akt inhibitor VIII (PKBinh VIII; 0, 0.01, 0.1, 1μM). At day 5, proliferation of CD4+ T cells was analyzed. (C) TGFβ-mediated suppression of CD4+ T-cell proliferation for PBMCs from HCs (black bars) and PBMCs (gray bars) and SFMCs (white bars) from JIA patients. The results show percentage of suppression in the presence of TGFβ relative to cells cultured without TGFβ. Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 3 PBMC HC, n = 4 PBMC JIA, and n = 5 SFMC JIA, *P < .05. (D) TGFβ-mediated suppression of CD4+ T cell proliferation for paired PBMCs (gray bars) and SFMCs (white bars) in the presence of increasing concentrations of PKB/c-akt inhibitor VIII. The data show the change in TGFβ-mediated suppression for each concentration of PKB/c-akt inhibitor relative to cultures without PKB/c-akt inhibitor. Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 3, *P < .05 compared with 0μM PKB/c-akt inhibitor VIII. (E) CD4+CD25+CD127low Tregs were sorted from SFMCs by flow cytometry and cocultured with CFSE-labeled PBMCs (squares) or SFMCs (triangles) at a 1:4 ratio in the presence or absence of PKB/c-akt inhibitor VIII (PKBinh VIII) (0.1μM). At day 4, Treg-mediated suppression of CD4+ T-cell proliferation was analyzed. The data show the change in Treg- mediated suppression in the presence PKB/c-akt inhibitor relative to cultures without PKB/c-akt inhibitor.

In mice, expression of constitutively activated PKB/c-akt renders effector cells resistant to both Tregs as well as TGFβ-mediated suppression,33 therefore, we investigated whether SFMC, showing enhanced PKB/c-akt activation, are also refractory to TGFβ-mediated suppression. Proliferation of CD4+ T cells from PBMCs of HCs (black bars) and JIA patients (gray bars) was clearly suppressed by the presence of TGFβ, whereas, only very low levels of suppression were detected in SF CD4+ T cells (white bars; Figure 6C), showing that these cells are resistant to TGFβ-mediated suppression. To investigate whether increased PKB/c-act activation directly leads to resistance of these cells to suppression, we determined whether inhibiting this kinase restored responsiveness to TGFβ. Culture of SFMCs in the presence of a specific PKB/c-akt inhibitor dose-dependently decreased PKB activation in these cells as measured by flow cytometry (supplemental Figure 5A). As a result, TGFβ-mediated suppression of SFMCs (white bars), but not already responsive PBMCs (gray bars), was enhanced in the presence of this inhibitor (Figure 6D).

In addition, PKB/c-akt inhibition restored responsiveness of SFMCs (triangles) to Treg-mediated suppression, without affecting suppression of PBMCs (squares; Figure 6E). Importantly, PKB/c-akt inhibitor treatment did not affect proliferation of SFMCs in the absence of TGFβ and Tregs (supplemental Figure 5B), showing that it specifically targets the unresponsiveness of these cells to suppression, and does not inhibit proliferation in general. Together these data clearly demonstrate that the resistance of effector cells to suppression at the site of inflammation is caused by PKB/c-akt hyperactivation. Furthermore, by pharmacologically targeting this pathway responsiveness of the cells to suppression can be restored.

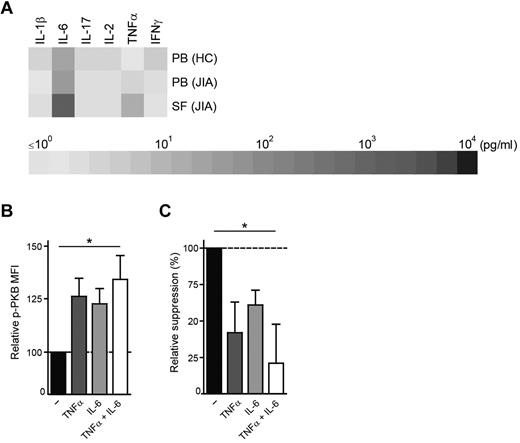

TNFα and IL-6 present at the site of inflammation induce PKB/c-akt activation and resistance to suppression

We are the first to show that PKB/c-akt hyperactivation occurs under physiologic conditions at the site of inflammation in human autoimmune disease. It is therefore intriguing to identify the cause of this enhanced PKB/c-akt activation. To investigate whether soluble factors present in the inflammatory environment lead to enhanced PKB/c-akt activation, we first measured the expression of proinflammatory cytokines in PB plasma of HCs and paired PB plasma and SF of JIA patients (Figure 7A). In line with previous reports25 and regarding effectiveness of TNFα- and IL-6–blocking strategies in arthritis,34 we observed elevated levels of TNFα and IL-6 in SF of JIA patients. Incubation of PBMCs from HCs with these cytokines resulted in an up-regulation of p-PKB (Figure 7B) and reduced responsiveness to TGFβ-mediated suppression (Figure 7C), which was significant when both TNFα and IL-6 were added (P < .05). Together, these data identify TNFα and IL-6 as proinflammatory factors that contribute to enhanced PKB/c-akt activation and subsequent resistance to suppression at the site of human autoimmune inflammation.

TNFα and IL-6 present at the site of inflammation induce PKB/c-akt activation resulting in resistance to suppression. (A) IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17, IL-2, TNFα, and IFNγ expression in n = 4 PB plasma of HCs and n = 8 paired PB plasma and SF of JIA patients measured by Luminex. (B-C) PBMCs from HCs were untreated or incubated overnight with TNFα (50 ng/mL), IL-6 (100 ng/mL) or both TNFα and IL-6. After incubation period, cells were stained for phosphorylated PKB/c-akt expression by flow cytometry (B) or CFSE labeled and cultured in the presence or absence of recombinant human TGFβ1 (40 ng/mL) and TNFα and IL-6 to measure TGFβ-mediated suppression (C). (B) MFI of phosphorylated PKB/c-akt (p-PKB) in CD4+ T cells in the presence of TNFα (dark gray bars), IL-6 (light gray bars) or both (white bars) relative to cultures without cytokines added (black bars). Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 5, *P < .05. (C) TGFβ-mediated suppression of CD4+ T-cell proliferation in the absence (black bars) or presence of TNFα (dark gray bars), IL-6 (light gray bars) or both (white bars). The data show the change in TGFβ-mediated suppression in the presence of cytokines compared with cultures without cytokines added. Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 5, *P < .05.

TNFα and IL-6 present at the site of inflammation induce PKB/c-akt activation resulting in resistance to suppression. (A) IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17, IL-2, TNFα, and IFNγ expression in n = 4 PB plasma of HCs and n = 8 paired PB plasma and SF of JIA patients measured by Luminex. (B-C) PBMCs from HCs were untreated or incubated overnight with TNFα (50 ng/mL), IL-6 (100 ng/mL) or both TNFα and IL-6. After incubation period, cells were stained for phosphorylated PKB/c-akt expression by flow cytometry (B) or CFSE labeled and cultured in the presence or absence of recombinant human TGFβ1 (40 ng/mL) and TNFα and IL-6 to measure TGFβ-mediated suppression (C). (B) MFI of phosphorylated PKB/c-akt (p-PKB) in CD4+ T cells in the presence of TNFα (dark gray bars), IL-6 (light gray bars) or both (white bars) relative to cultures without cytokines added (black bars). Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 5, *P < .05. (C) TGFβ-mediated suppression of CD4+ T-cell proliferation in the absence (black bars) or presence of TNFα (dark gray bars), IL-6 (light gray bars) or both (white bars). The data show the change in TGFβ-mediated suppression in the presence of cytokines compared with cultures without cytokines added. Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 5, *P < .05.

Discussion

After 15 years of research into Treg biology the main question is whether these cells can be used in treatment of autoimmune disease. To resolve this issue more information on Treg function at the site of autoimmune inflammation in humans is required. Here we studied Treg function in patients with JIA and show that both in the periphery and at the site of inflammation, Tregs are not deficient in number and function. Nevertheless, effector cells from the site of inflammation are poorly controlled, because these cells are resistant to suppression. We further demonstrate that this unresponsiveness to suppression is, at least partially, caused by PKB/c-akt hyperactivation and can be restored by specific PKB/c-akt inhibition. These data therefore identify PKB/c-akt as a potential novel target for the treatment of autoimmune disease.

In the PB of JIA patients, no change in the numbers of Tregs was observed and these cells suppressed both cell proliferation and cytokine production similar to Tregs from HCs. In contrast, defective Treg function has previously been described in the peripheral blood of RA patients.12,15 Perhaps differences in Treg function in the periphery are less pronounced in OA JIA, because of its relative mild and local pathology. Alternatively, because CD127 has become available as an additional marker to isolate Tregs,5,6 the differences in results could also be explained by differences in Treg purity. Other studies are, however, in agreement with our data and report no difference in Treg function in patients with established arthritis.14,16,35

At the site of inflammation in patients with JIA, increased numbers of Tregs were present and these cells showed normal suppressive capacity. Thus, we and others14,16,18,19,36 have observed that Tregs from the site of inflammation are fully functional. However, by mimicking the in vivo situation as closely as possible and using total mononuclear cells as effector cells in our assays, we were able to demonstrate that these Tregs still failed to control effector cells from the site of inflammation. This was caused by reduced responsiveness of these effector cells to suppression. In other experimental models of autoimmune disease and some patient studies, most profoundly systemic lupus erythematosus and type 1 diabetes, resistance of effector cells to suppression has also been described.22,37-42 However, in OA JIA unresponsiveness of effector cells to suppression occurs locally, at the site of inflammation, and not systemically. In genetically prone mice effector cells become resistant to suppression before clinical overt disease,37,39 suggesting that this phenomenon acts early in disease pathology and is therefore an important target in controlling autoimmune inflammation. However, to target this resistance of effector cells effectively, the underlying mechanism needs to be clarified.

Here, we show that autoimmune inflammatory effector cells are resistant to both TGFβ- as well as Treg-mediated suppression and that this resistance does not result from a general memory phenotype of the cells or activation status of APCs. Instead, hyperactivation of PKB/c-akt is responsible for the unresponsiveness to suppression, as CD4+ effector T cells from the site inflammation showed increased PKB/c-akt phosphorylation and selective inhibition of this kinase restored responsiveness of cells to suppression. We are the first to show that PKB/c-akt is involved in resistance to suppression in human autoimmune disease, consistent with findings in mice.33,43

Phosphorylation and activation of PKB/c-akt is regulated by the generation of lipid products by phosphoinositide 3 kinases (PI3Ks) and PI3K is activated in lymphocytes on binding of antigens, costimulatory molecules, cytokines, and chemokines.32,44 PI3K-PKB activation by chemokines is, however, both rapid and transient,44 therefore, enhanced PKB/c-akt activation in cells at the site of inflammation is likely to result from either TCR, CD28, or cytokine signaling. We show that TNFα and IL-6 are elevated in synovial fluid of JIA patients and induce PKB/c-akt activation and resistance to suppression, in line with previous reports showing that these cytokines can confer resistance to suppression in mice.22,23 Other cytokines and CD28 signaling can activate the PI3K-PKB pathway as well,45 therefore it is likely that a combination of environmental factors contributes to resistance to suppression at the site of human autoimmune inflammation. However, given the effectiveness of TNFα and IL-6 blockade in the treatment of arthritis,34 it is intriguing to speculate that TNFα and IL-6 are critical in inducing resistance to suppression and that the effectiveness of these strategies can partially be explained by inhibiting PKB/c-akt activation.

Independent of the initial cause of PKB/c-akt activation, we show that selective PKB/c-akt inhibition is sufficient to restore responsiveness of effector cells to suppression, making this kinase an attractive target for therapeutic intervention. Clinical efficacy of PI3K inhibition, upstream of PKB/c-akt, has already been demonstrated in experimental models of arthritis46 and systemic lupus erythematosus.47 Targeting this pathway might therefore be beneficial in a wide range of autoimmune inflammatory conditions. However, for a PKB/c-akt targeted approach to be successful negative effects on Treg function must be prevented. In human PB-derived Tregs PKB/c-akt was hypoactivated and this hypoactivation was essential for their suppressive function.48 Therefore, PKB/c-akt inhibition might not negatively affect Treg function and could even enhance de novo generation of Tregs.49,50 As a result, selective PKB/c-akt inhibition might be especially effective when combined with a Treg enhancing strategy, ensuring responsiveness of effector cells to suppression and simultaneously creating an environment suited for Treg induction.

In conclusion, the data presented in this study provide new insights in the pathology of autoimmune disease and raise important therapeutic implications. Our findings argue for a T effector instead of Treg-targeted approach to control autoimmune inflammation. More specifically, responsiveness of effector cells to suppression should be restored by selectively inhibiting PKB/c-akt activation.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mariska van Dijk for technical assistance in the Luminex assays and Nico Wulffraat for patient inclusion.

This research was funded by Top Institute Pharma (TI Pharma). J.v.L. was supported by a grant from the Dutch Rheumatology Foundation. F.v.W. is supported by a Veni grant from the Dutch Organization for Scientific Research (NWO). B.J.P. is supported by the Dutch Rheumatology Foundation and an NWO Innovation Impulse grant (VIDI).

Authorship

Contribution: E.J.W., B.V., J.v.L., P.J.C., B.J.P. and F.v.W. designed research; E.J.W., G.M., C.L.D., M.K., J.M., and W.d.J. performed research; B.S. analyzed methylation of FOXP3 TSDR; E.J.W. and G.M. analyzed and interpreted data; E.J.W. performed statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript; and P.J.C., B.J.P., and F.v.W. edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ellen J. Wehrens, Suite KC.01.069.0, PO Box 85090, 3508 AB Utrecht, The Netherlands; e-mail: ewehrens@umcutrecht.nl.

References

Author notes

B.J.P. and F.v.W. contributed equally to this article.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal