Abstract

The PML-RARα fusion protein is central to the pathogenesis of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL). Expression of this protein in transgenic mice initiates myeloid leukemias with features of human APL, but only after a long latency (8.5 months in MRP8 PML-RARAmice). Thus, additional changes contribute to leukemic transformation. Activating mutations of the FLT3 receptor tyrosine kinase are common in human acute myeloid leukemias and are frequent in human APL. To assess how activating mutations of FLT3 contribute to APL pathogenesis and impact therapy, we used retroviral transduction to introduce an activated allele of FLT3 into control and MRP8 PML-RARA transgenic bone marrow. Activated FLT3 cooperated with PML-RARα to induce leukemias in 62 to 299 days (median latency, 105 days). In contrast to the leukemias that arose spontaneously inMRP8 PML-RARA mice, the activated FLT3/PML-RARα leukemias were characterized by leukocytosis, similar to human APL with FLT3 mutations. Cytogenetic analysis revealed clonal karyotypic abnormalities, which may contribute to pathogenesis or progression. SU11657, a selective, oral, multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets FLT3, cooperated with all-trans retinoic acid to rapidly cause regression of leukemia. Our results suggest that the acquisition of FLT3 mutations by cells with a pre-existing t(15;17) is a frequent pathway to the development of APL. Our findings also indicate that APL patients with FLT3 mutations may benefit from combination therapy with all-trans retinoic acid plus an FLT3 inhibitor.

Introduction

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is defined by the presence of a PML-RARA fusion gene or, rarely, by alternative RARA fusions.1PML-RARAfusion is created as a result of a chromosomal translocation, t(15;17)(q22;q12).2RARA encodes retinoic acid receptor α (RARα), a member of the steroid–thyroid hormone nuclear receptor superfamily that stimulates myeloid differentiation in the presence of its ligand, all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA). Promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML) encodes a nuclear protein that can induce growth arrest and apoptosis. The PML-RARα protein inhibits PML function and thereby contributes to enhanced cell survival and growth deregulation. PML-RARα also interferes with transcription, including enhancing the repression of RARα target genes by increasing associations with corepressors and, as recently shown,3 by recruiting DNA methyl-transferases. PML-RARα inhibits the differentiation of myeloid cell lines4-7 and can initiate acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in mice.8-10 The leukemias initiated by PML-RARA in mice have features of human APL, including differentiation in response to ATRA.

The FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3 [FLK-2, STK-1]) receptor enhances the proliferation and survival of hematopoietic progenitors in response to FLT3 ligand.11,12 Activating mutations of FLT3 have been identified in 25% to 30% of human patients with AML and are common in APL (18%-37% of APL patients).13-17 Many activating mutations of FLT3 are the result of an internal tandem duplication (ITD) of the intracellular juxtamembrane region of this molecule.18 These ITD mutations result in constitutive tyrosine kinase activity.19,20 It is of interest that though activated tyrosine kinases are often associated with human chronic myeloproliferative diseases (MPDs), commonlyBCR-ABL,1 and infrequently such fusions asTEL-PDGFBR,21HIP1-PDGFBR,22D10S170-PDGFBR,23,24 andRAB5EP-PDGFBR,25 activating mutations of FLT3 have not yet been similarly identified in human MPD.

Genetic manipulation of mice is a powerful tool for understanding the contributions that particular genetic changes make to malignant transformation. Studies of PML-RARA transgenic mice revealed that PML-RARα initially exerted relatively modest effects on myelopoiesis in vivo but could initiate AML in association with additional genetic changes.8-10,26-30 The introduction of activated alleles of FLT3 into the bone marrow of BALB/c mice by retroviral transduction led to the development of a lethal MPD in recipient animals.31 Given the common coexistence ofPML-RARA and activated FLT3 in human APL, we used our mouse model to assess the ability of these 2 genetic changes to cooperate in leukemogenesis. Introduction of an activated allele ofFLT3 into mouse bone marrow expressingPML-RARA resulted in the rapid development of AMLs with features of human APL with the FLT3 mutation.

Given the clinical efficacy of the selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor, imatinib mesylate, to treat BCR-ABL– andTEL-PDGFBR–positive chronic myeloproliferative diseases,32,33 we investigated whether the inhibition of activated FLT3 would affect the growth of acute leukemias that expressed PML-RARα and activated FLT3. We examined the effects on such leukemias of SU11657, a selective and potent small molecule inhibitor of several members of the split-kinase domain receptor tyrosine kinase family, including platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 (VEGFR1), VEGFR2, KIT, and FLT3.34 35 Whereas SU11657 modestly impaired the progression of leukemia when used as a single agent, SU11657 combined with ATRA to rapidly restore normal hematopoiesis.

Materials and methods

Mice

Mice were bred and maintained at the University of California at San Francisco, and their care was in accordance with the university's guidelines. MRP8 PML-RARA transgenic mice in the FVB/N background and control FVB/N mice were used for all experiments.

Retroviral transductions

Control FVB/N and PML-RARA transgenic donor mice were treated with 150 mg/kg 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), and marrow was harvested 5 days later. Marrow was disassociated through a 40-μm mesh and was prestimulated for 24 hours in Myelocult 3200 (Stem-Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) supplemented with 5% X63Ag8–murine interleukin-3 (mIL-3)–conditioned media,36 100 U/mL penicillin G, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, 6 ng/mL mIL-3, 10 ng/mL mIL-6, and 100 ng/mL stem cell factor (growth factors from Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ). BOSC23 cells37 were transfected with mouse stem cell virus retroviral constructs38 that contained an internal ribosomal entry site upstream of green fluorescence protein39(MSCV-IRES-GFP or MIG). MIG constructs expressing wild-type FLT3 (MSCV-FLT3wt-IRES-GFP) or an activated version of FLT3 (MSCV-FLT3W51-IRES-GFP) have been described previously.31 Marrow was transduced by spinoculation with fresh retroviral supernatants (filtered through 0.45-μm filters) at 1100g in the presence of 2 μg/mL polybrene for 1.5 hours on 2 consecutive days. Unsorted cells after transduction were introduced into lethally irradiated (9 Gy in 2 equal doses 3-6 hours apart) mice.

Peripheral blood counts and bone marrow differential counts

Blood was obtained from the retro-orbital sinuses of anesthetized mice. White blood cell (WBC) count, hemoglobin level, and platelet count were measured with the Hemavet 850 FS cell counter (CDC Technologies, Oxford, CT). Bone marrow was flushed from the tibias and femurs of mice with buffered saline supplemented with 2% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 2.5% cell dissociation buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Blood smears, marrow smears, and marrow and spleen cytospins were prepared according to standard hematologic techniques and were stained with Wright-Giemsa stain. Peripheral blood differential WBC counts (200 cells each) and bone marrow differential counts (400 cells each) were in accord with published guidelines.40

Histopathology

Sternum, liver, spleen, kidney, lungs, lymph nodes, and intestine were initially fixed in either Bouin fixative or a buffered formalin solution before embedding in paraffin. Sternums fixed in formalin were decalcified for 3 hours before embedding (11% formic acid, 8% formaldehyde). Sections were prepared according to standard protocols and were stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Cytochemical stains

Suspensions of viable bone marrow and spleen cells were depleted of red blood cells with the use of Histopaque 1119 (Sigma, St Louis, MO) at 4°C according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cytospins of bone marrow and spleen were prepared by standard technique. Cytospins were stained with chloroacetate esterase or alpha-naphthyl acetate esterase according to the manufacturer's instructions (Sigma).

Immunophenotyping

For flow cytometric immunophenotyping, 300 000 bone marrow or spleen cells were suspended in 100 to 200 μL buffered saline (with 2% heat-inactivated FBS and 2.5% cell dissociation buffer). Cells were incubated on ice with unlabeled anti-CD16/CD32 antibodies (Fc block) for 15 minutes before the addition of antibodies (obtained from Cal-Tag Laboratories, Burlingame, CA or BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA). Phycoerythrin, Tri-Color, or biotin-conjugated antibodies to mouse CD3, CD11b (Mac-1), CD19, CD31 (PECAM), CD34, CD61, CD86, CD117 (c-kit), Ly-6G (Gr-1), Ly-71 (F4/80), or Ly-76 (Ter119) were added and incubated with the cells for 20 minutes in the dark on ice. Biotin antibodies were subsequently washed and incubated with streptavidin–allophycocyanin. Cells were washed with buffered saline and resuspended in a final volume of 200 μL. Stained cells were analyzed on a FACScan or FACScalibur (Becton Dickinson), and at least 10 000 events were collected for each sample. FACS data were analyzed with CellQuest (Becton Dickinson). We used forward-scatter (FSC), side-scatter (SSC), GFP, and CD45 (when applicable) to select gated cells for analysis, as described in the legends to Figures 3 and 8.

Western blotting

Whole cell lysates were prepared by lysing 1 × 107 cells in 500 μL 2 × sample buffer, heating at 90°C to 95°C for 5 minutes, and shearing through a 20-gauge needle. Western blot analysis was performed as previously described8 41 using a rabbit polyclonal antiserum raised against a glutathione-S-transferase (GST)–fusion protein that encompassed amino acids 420 to 462 of the human RARα protein. FLT3 expression was detected using anti-FLT3 SC479 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Bands were visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Karyotyping

Cytogenetic and spectral karyotyping analysis of spleen cells was performed as described.30

Southern blotting

Southern blots of DNA derived from leukemic spleens was performed as described with a probe for retroviral DNA.31

In vitro analysis of FLT3 phosphorylation

The MV 4;11 human leukemia cell line, which expresses FLT3-ITD, was maintained as previously described.42 To assess FLT3 phosphorylation, cells were treated with SU11657 for 2 hours in medium containing 0.1% FBS and lysed as described.42 Equivalent amounts of protein from each sample were immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C with an agarose-conjugated anti-FLT3 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Immune complexes were washed (150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid], pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 1 mM EGTA [ethyleneglycotetraacetic acid]), separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were probed with an antiphosphotyrosine antibody 4G10 (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY or Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY) and were stripped with Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Membranes were reprobed with an anti-FLT3 antibody.

Transplantation of leukemic cells

Leukemic cells isolated from the bone marrow and spleen of experimental animals were resuspended in buffered saline. After a sublethal (4.5 Gy) dose of irradiation, 1 × 106 cells in 100 μL buffered saline were injected into the tail veins of each FVB/N recipient mouse. Recipients of serially transplanted leukemia 1127 were treated with ATRA, SU11657, or both.

Treatment of mice with ATRA and SU11657

Retinoic acid (10 mg, 21-day release) or placebo pellets (Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL) were implanted subcutaneously using a 12-gauge trochar. SU11657 was administered daily at 20 mg/kg/d in a carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) suspension by oral gavage. Mice were observed twice daily for the development of disease.

Statistical analyses

The Student t test (2-sided, unequal variance) was used except as otherwise noted.

Results

Activated FLT3 accelerates the appearance of leukemia in MRP8 PML-RARA transgenic mice

To test the ability of activated FLT3 to cooperate with PML-RARα in leukemogenesis, we used retroviral transduction of bone marrow fromMRP8 PML-RARA transgenic mice. Bone marrow cells of control and PML-RARA transgenic mice were transduced with control or activated FLT3 retroviruses. These cells were subsequently introduced into lethally irradiated recipient mice that were monitored for the development of disease.

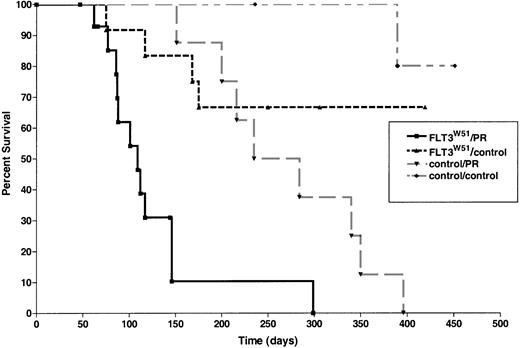

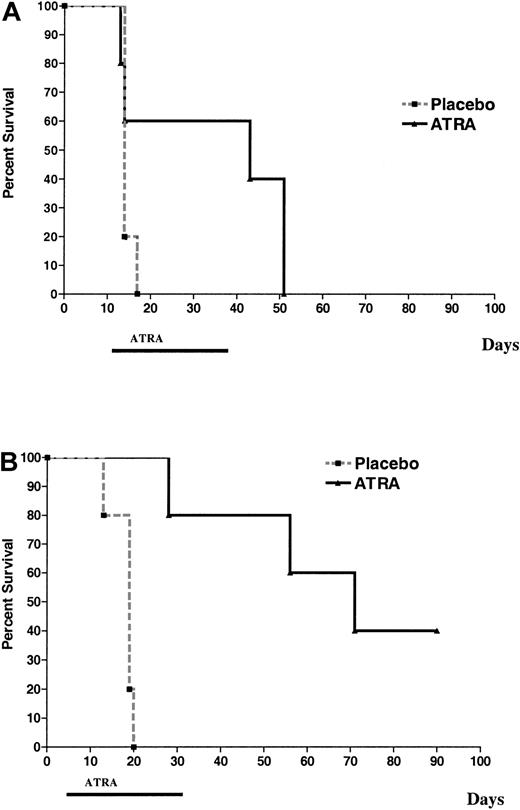

Recipients of PML-RARA transgenic marrow transduced with an activated FLT3 retrovirus (FLT3W51, an ITD mutation from a human patient) developed leukemia beginning at 62 days after transplantation (median latency, 105 days; range, 62-299 days; Figure1). Latency until disease was shorter than that observed in recipients of PML-RARA marrow transduced with control retroviruses (Figure 1) or in recipients ofPML-RARA marrow that had not undergone retroviral transduction.28 Time to illness of activated FLT3/PML-RARα recipients was also less than that observed in recipients of control bone marrow transduced with either activated FLT3 or control retroviruses (Figure 1).

Activated FLT3 cooperates with a

MRP8 PML-RARA transgene to cause leukemia.Survival curves are shown of mice reconstituted withPML-RARA transgenic or control FVB/N bone marrow after transduction with activated FLT3 (FLT3W51) or control (FLT3wt or GFP only) retroviruses. Overall survival, including leukemic and nonleukemic deaths, is shown (see “Results”). FLT3W51/PR indicates activated FLT3 retrovirus in PML-RARA transgenic bone marrow (n = 15); FLT3W51/control, activated FLT3 retrovirus in FVB/N bone marrow (n = 12); control/PR, control retroviral vector inPML-RARA transgenic bone marrow (n = 8); control/control, control retroviral vector in FVB/N bone marrow (n = 10).

Activated FLT3 cooperates with a

MRP8 PML-RARA transgene to cause leukemia.Survival curves are shown of mice reconstituted withPML-RARA transgenic or control FVB/N bone marrow after transduction with activated FLT3 (FLT3W51) or control (FLT3wt or GFP only) retroviruses. Overall survival, including leukemic and nonleukemic deaths, is shown (see “Results”). FLT3W51/PR indicates activated FLT3 retrovirus in PML-RARA transgenic bone marrow (n = 15); FLT3W51/control, activated FLT3 retrovirus in FVB/N bone marrow (n = 12); control/PR, control retroviral vector inPML-RARA transgenic bone marrow (n = 8); control/control, control retroviral vector in FVB/N bone marrow (n = 10).

Although our transductions of bone marrows with the MIG retrovirus typically is associated with transduction efficiencies of approximately 30%, transduction efficiencies with the wild-type and FLT3W51 retroviruses were lower (2%-17%), as was observed in previous studies (Kelly et al31 43 and data not shown). These low levels of transduction were nevertheless associated with high penetrance of leukemia in recipients of activated FLT3-transducedPML-RARA bone marrow. Of note, in the moderate number of mice we studied, there was no correlation between transduction efficiency and latency of disease (r2 = 0.4; 12 leukemias from 6 independent transductions).

Activated FLT3/PML-RARα leukemias model human APL with FLT3 mutations

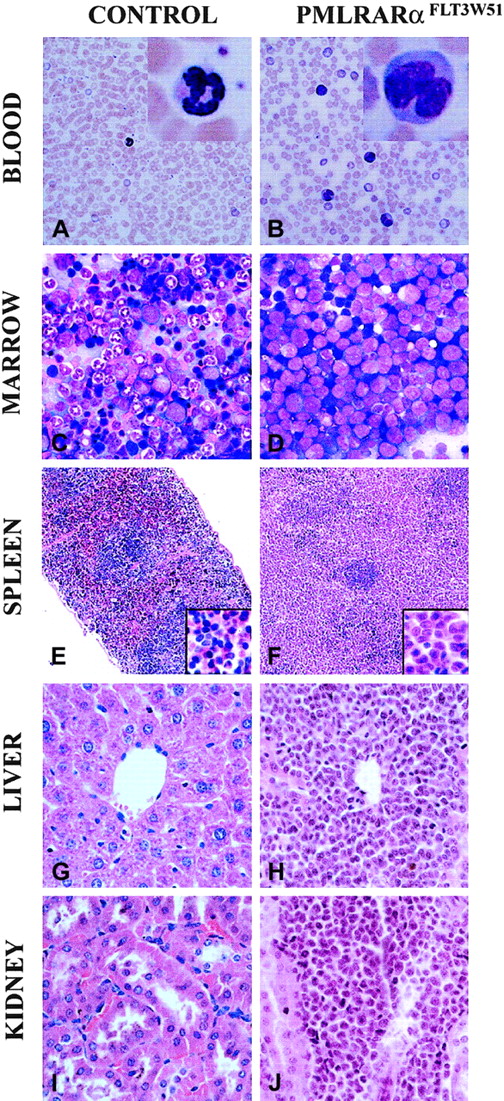

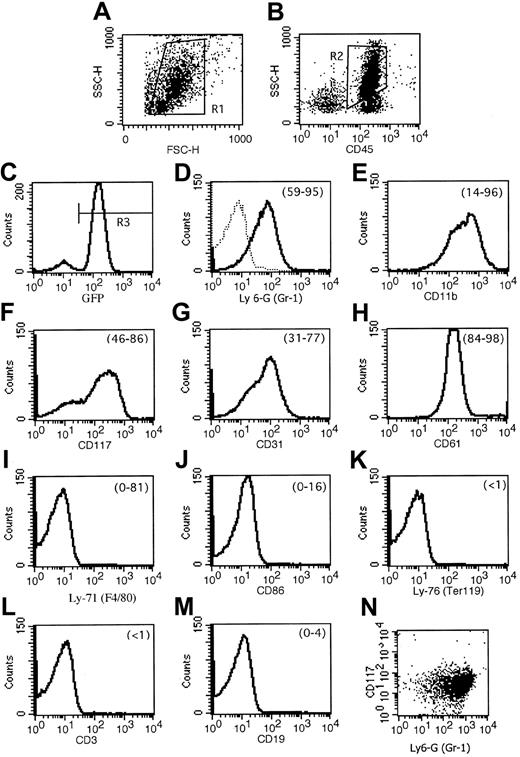

We had observed that leukemias that arose spontaneously in MRP8 PML-RARA mice did not exhibit elevated leukocyte counts. In contrast, the leukemias that developed in the presence of activated FLT3 usually exhibited leukocytosis (Table1). This feature of FLT3-associated leukemias in PML-RARA mice paralleled the leukocytosis that typifies APL with FLT3 mutations in humans.13 The disease in activated FLT3/PML-RARα recipients was an aggressive leukemia. When compared with healthy blood, the peripheral blood contained numerous immature forms/blasts, including occasional cells with deep nuclear indentations similar to the bilobed forms that typify the microgranular variant of human APL1 (Figure 2A-B). Similarly, in contrast to healthy mice, bone marrows contained numerous immature forms/blasts (Table 2; Figure 2C-D). The cytoplasm of these cells contained azurophilic granules, but Auer rods were not seen. Many of the immature leukemic cells stained weakly to strongly with the neutrophil marker chloroacetate esterase. A variable number of marrow myeloid cells stained with the monocyte marker α-naphthyl acetate esterase, but the number of such cells did not exceed 20% of marrow nonerythroid cells (data not shown). Flow cytometric immunophenotyping of 7 leukemias demonstrated that leukemic cells expressed GFP, and it corroborated morphology and cytochemistry in demonstrating the myeloid character of the leukemias (Figure 3). The leukemias expressed the combination of Ly-6G (Gr-1) and CD117 (c-kit), indicative of immature myeloid cells. Consistent with this was the expression of CD61 (which in mice is not restricted to megakaryocytic cells but is also expressed by granulocytes) and CD31 (PECAM). Cells lacked the lymphocyte markers CD3 and CD19 and the erythroid marker Ly-76 (Ter119). There was some heterogeneity among the leukemias: CD11b (Mac-1) varied from weak to moderate; Ly-6G (Gr-1) expression varied from moderate to strong; and 2 leukemias expressed low levels of Ly-71 (F4/80) and CD86. In addition to expressing GFP, a surrogate marker for FLT3 expression, the leukemias expressed PML-RARα and FLT3, as assessed by Western blot analysis (data not shown).

Peripheral blood counts of leukemic FLT3W51/PML-RARα mice

| Mice . | Blood counts . | WBC differential counts, % . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC . | HGB . | Platelets . | Imm/Bl . | Intermediate . | Neutrophils . | Lymphocytes . | Monocytes . | Eosinophils . | |

| Control | 3.9 | 13.5 | 1041 | 0 | 0 | 7.9 | 89.9 | 1.7 | 1 |

| PML-RARα leukemia | 4.5 | 7.8 | 334 | 6.8 | 3.2 | 2 | 87.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| PML-RARα/FLT3W51leukemia | 28.5 | 8.4 | 239 | 32.2 | 10.5 | 4.7 | 51.9 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| 747 | 25.5 | 8.3 | 194 | 32.5 | 8 | 14 | 45.5 | 0 | 0 |

| 874 | NA | NA | NA | 85 | 1.5 | 2 | 11 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 1019 | 15.4 | 7.4 | 102 | 15 | 7 | 5 | 61.5 | 1 | 0 |

| 1020 | 30.3 | 9.6 | 281 | 19 | 7 | 5 | 69 | 0 | 0 |

| 1086 | 6.5 | 6.9 | 289 | 8 | 13 | 2 | 76.5 | 0 | 0.5 |

| 1087 | 13.3 | 7.4 | 318 | 14 | 23 | 6 | 64 | 0 | 0 |

| 1127 | 59.2 | 8.4 | 228 | 39 | 21 | 3.5 | 36 | 0 | 0.5 |

| 1128 | 49.1 | 11.0 | 260 | 45 | 3.5 | 0 | 51.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Mice . | Blood counts . | WBC differential counts, % . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC . | HGB . | Platelets . | Imm/Bl . | Intermediate . | Neutrophils . | Lymphocytes . | Monocytes . | Eosinophils . | |

| Control | 3.9 | 13.5 | 1041 | 0 | 0 | 7.9 | 89.9 | 1.7 | 1 |

| PML-RARα leukemia | 4.5 | 7.8 | 334 | 6.8 | 3.2 | 2 | 87.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| PML-RARα/FLT3W51leukemia | 28.5 | 8.4 | 239 | 32.2 | 10.5 | 4.7 | 51.9 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| 747 | 25.5 | 8.3 | 194 | 32.5 | 8 | 14 | 45.5 | 0 | 0 |

| 874 | NA | NA | NA | 85 | 1.5 | 2 | 11 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 1019 | 15.4 | 7.4 | 102 | 15 | 7 | 5 | 61.5 | 1 | 0 |

| 1020 | 30.3 | 9.6 | 281 | 19 | 7 | 5 | 69 | 0 | 0 |

| 1086 | 6.5 | 6.9 | 289 | 8 | 13 | 2 | 76.5 | 0 | 0.5 |

| 1087 | 13.3 | 7.4 | 318 | 14 | 23 | 6 | 64 | 0 | 0 |

| 1127 | 59.2 | 8.4 | 228 | 39 | 21 | 3.5 | 36 | 0 | 0.5 |

| 1128 | 49.1 | 11.0 | 260 | 45 | 3.5 | 0 | 51.5 | 0 | 0 |

Peripheral blood counts of control, leukemic PML-RARα, and leukemic FLT3W51/PML-RARα mice are shown as mean values along with data from 8 individual FLT3W51/PML-RARα mice. WBC indicates white blood cell count, 1000/μL; HGB, hemoglobin, g/dL; PLT, platelet count, 1000/μL; Imm/Bl, immature forms/blasts; Neutrophils, mature forms, neutrophilic; and NA, not available. Blood counts: control n = 9, PML-RARα leukemias n = 10, FLT3W51/PML-RARα leukemias n = 7. WBC differential counts: control n = 7, PML-RARα leukemias n = 6, FLT3W51/PML-RARα leukemias n = 8. Compared with control, FLT3W51/PML-RARα leukemias show a statistically significant (P < .05) increase in white blood cell count, decrease in hemoglobin levels, decrease in platelet count, increase in immature forms/blasts, and increase in lymphocyte counts. Compared with PML-RARα leukemias, FLT3W51/PML-RARα leukemias show a statistically significant increase in white blood cell counts, increase in immature forms/blasts, increase in intermediate forms, and decrease in lymphocyte counts. Some of the control and PML-RARα leukemia data have been previously reported.28 46

Bone marrow counts of leukemic FLT3W51/PML-RARα mice

| Mice . | Imm/Bl . | Intermediate . | Neutrophils . | Erythrocytes . | Lymphocytes . | Eosinophils . | Other . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 2.8 | 15.7 | 25.6 | 39.9 | 13.7 | 2.6 | 0 |

| PML-RARα leukemia | 81.3 | 4.5 | 0.7 | 8.7 | 4.6 | 0.3 | 0 |

| PML-RARα/FLT3W51leukemia | 68.5 | 7.0 | 4.2 | 12.8 | 3.8 | 0.9 | 2.5 |

| 874 | 85.8 | 4 | 1.5 | 0 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 4.3 |

| 1019 | 64.5 | 13 | 11.5 | 4.8 | 2 | 2 | 3.5 |

| 1020 | 75.8 | 7.5 | 1.5 | 4.3 | 8.8 | 0 | 2.3 |

| 1086 | 50.8 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 36 | 4.5 | 0.8 | 2.3 |

| 1087 | 66.3 | 8.3 | 4.5 | 15.8 | 2.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| 1127 | 65.5 | 10.3 | 9.3 | 10.5 | 3.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| 1128 | 70.8 | 3.3 | 0.8 | 18 | 2.8 | 0.3 | 4 |

| Mice . | Imm/Bl . | Intermediate . | Neutrophils . | Erythrocytes . | Lymphocytes . | Eosinophils . | Other . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 2.8 | 15.7 | 25.6 | 39.9 | 13.7 | 2.6 | 0 |

| PML-RARα leukemia | 81.3 | 4.5 | 0.7 | 8.7 | 4.6 | 0.3 | 0 |

| PML-RARα/FLT3W51leukemia | 68.5 | 7.0 | 4.2 | 12.8 | 3.8 | 0.9 | 2.5 |

| 874 | 85.8 | 4 | 1.5 | 0 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 4.3 |

| 1019 | 64.5 | 13 | 11.5 | 4.8 | 2 | 2 | 3.5 |

| 1020 | 75.8 | 7.5 | 1.5 | 4.3 | 8.8 | 0 | 2.3 |

| 1086 | 50.8 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 36 | 4.5 | 0.8 | 2.3 |

| 1087 | 66.3 | 8.3 | 4.5 | 15.8 | 2.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| 1127 | 65.5 | 10.3 | 9.3 | 10.5 | 3.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| 1128 | 70.8 | 3.3 | 0.8 | 18 | 2.8 | 0.3 | 4 |

Bone marrow nucleated cell differential counts (%) of control, leukemic PML-RARα, and leukemic FLT3W51/PML-RARα mice are shown as mean values along with data from seven individual FLT3W51/PML-RARα mice. Erythrocytes: nucleated erythroid cells. Other: includes monocytes, macrophages, plasma cells, mast cells. Control n = 7, PML-RARα leukemias n = 6, FLT3W51/PML-RARα leukemias n = 7. Compared with control, FLT3W51/PML-RARα leukemias show a statistically significant difference for all cell types. The bone marrows of PML-RARα leukemias have significantly more immature forms/blasts than the bone marrows of FLT3W51/PML-RARα leukemias (P = .03). Some of the control and PML-RARα leukemia data have been previously reported.28 46

Combination of activated FLT3 and PML-RARα results in aggressive disseminated acute myeloid leukemias.

(A,C,E,G,I) Healthy FVB/N control. (B,D,F,H,J) Representative findings of leukemic-activated FLT3/PML-RARα mice. (A-B) Peripheral blood. Leukocytosis, including immature forms/blasts with indented nuclei, is present in leukemic mice. Comparisons of normal neutrophil with abnormal immature form/blast (insets). (C-D) Bone marrow smears. Leukemic marrow is filled with immature forms/blasts, many with numerous azurophilic granules. (E-F) Spleens. Leukemic spleen has red pulp effaced with leukemic cells; insets show red pulp at higher magnification. (G-H) Livers. Leukemic cells are present in periportal areas and infiltrate the sinusoids. (I-J) Kidneys. Leukemic cells infiltrate the kidney focally. (A-D) Wright-Giemsa stain. (E-J) Hematoxylin and eosin stain. Original magnification × 400 (A-D, G-J). Original magnification × 2400 (A-B, insets). Original magnification × 100 (E-F; insets, × 400).

Combination of activated FLT3 and PML-RARα results in aggressive disseminated acute myeloid leukemias.

(A,C,E,G,I) Healthy FVB/N control. (B,D,F,H,J) Representative findings of leukemic-activated FLT3/PML-RARα mice. (A-B) Peripheral blood. Leukocytosis, including immature forms/blasts with indented nuclei, is present in leukemic mice. Comparisons of normal neutrophil with abnormal immature form/blast (insets). (C-D) Bone marrow smears. Leukemic marrow is filled with immature forms/blasts, many with numerous azurophilic granules. (E-F) Spleens. Leukemic spleen has red pulp effaced with leukemic cells; insets show red pulp at higher magnification. (G-H) Livers. Leukemic cells are present in periportal areas and infiltrate the sinusoids. (I-J) Kidneys. Leukemic cells infiltrate the kidney focally. (A-D) Wright-Giemsa stain. (E-J) Hematoxylin and eosin stain. Original magnification × 400 (A-D, G-J). Original magnification × 2400 (A-B, insets). Original magnification × 100 (E-F; insets, × 400).

Flow cytometric immunophenotyping of FLT3W51/PML-RARα leukemias demonstrates that they are composed of immature myeloid cells.

(A) FSC/SSC, ungated. (B) CD45/SSC, gate = R1. (C) GFP, gate = R1 and R2. Remaining panels: gate = R1 and R2 and R3. Results of a representative leukemia (no. 747) are shown. (D) Dotted line in the Ly-6G (Gr-1) histogram represents an isotype control antibody. Numbers in parentheses at the top right of the histograms indicate the range of percent expression of the given marker compared with control antibody for the leukemias analyzed. (E) Of particular note, though leukemia number 747 expressed CD11b (Mac-1) moderately strongly, other leukemias analyzed showed weak and variable expression. (I) F4/80 also had heterogenous expression; 2 leukemias (nos. 1128 and 1087) had moderately strong expression, and expression in the remaining was very low. Mean ± standard deviation for the markers was as follows: (D) Ly-6G (Gr-1), 80.7 ± 13.2 (% of GFP-positive cells); (E) CD11b (Mac-1), 56.8 ± 32.2; (F) CD117 (c-kit), 69.7 ± 14.2; (G) CD31, 54.2 ± 18.3; (H) CD61, 94.1 ± 5.2; (I) Ly-71 (F4/80), 19.4 ± 33.8; (J) CD86, 6.6 ± 6.0; (K) Ly-76 (Ter119) < 0.5; (L) CD3 < 0.5; (M) CD19, 0.7 ± 1.4. Because CD117 (c-kit) and Ly-6G (Gr-1) were each expressed on more than 50% of GFP-positive cells in 5 leukemias, it is clear that these markers are coexpressed by leukemic immature forms/blasts. This coexpression is depicted in the final panel (N) showing coexpression of CD117 and Ly-6G on leukemia number 1128.

Flow cytometric immunophenotyping of FLT3W51/PML-RARα leukemias demonstrates that they are composed of immature myeloid cells.

(A) FSC/SSC, ungated. (B) CD45/SSC, gate = R1. (C) GFP, gate = R1 and R2. Remaining panels: gate = R1 and R2 and R3. Results of a representative leukemia (no. 747) are shown. (D) Dotted line in the Ly-6G (Gr-1) histogram represents an isotype control antibody. Numbers in parentheses at the top right of the histograms indicate the range of percent expression of the given marker compared with control antibody for the leukemias analyzed. (E) Of particular note, though leukemia number 747 expressed CD11b (Mac-1) moderately strongly, other leukemias analyzed showed weak and variable expression. (I) F4/80 also had heterogenous expression; 2 leukemias (nos. 1128 and 1087) had moderately strong expression, and expression in the remaining was very low. Mean ± standard deviation for the markers was as follows: (D) Ly-6G (Gr-1), 80.7 ± 13.2 (% of GFP-positive cells); (E) CD11b (Mac-1), 56.8 ± 32.2; (F) CD117 (c-kit), 69.7 ± 14.2; (G) CD31, 54.2 ± 18.3; (H) CD61, 94.1 ± 5.2; (I) Ly-71 (F4/80), 19.4 ± 33.8; (J) CD86, 6.6 ± 6.0; (K) Ly-76 (Ter119) < 0.5; (L) CD3 < 0.5; (M) CD19, 0.7 ± 1.4. Because CD117 (c-kit) and Ly-6G (Gr-1) were each expressed on more than 50% of GFP-positive cells in 5 leukemias, it is clear that these markers are coexpressed by leukemic immature forms/blasts. This coexpression is depicted in the final panel (N) showing coexpression of CD117 and Ly-6G on leukemia number 1128.

The leukemias were aggressive, disseminated diseases effacing the spleens and infiltrating nonhematopoietic tissues including liver, kidneys, and lung (Figure 2E-J and data not shown). Spleens and livers of leukemic animals were enlarged (mean weight of activated FLT3/PML-RARα spleen, 576 mg; liver, 3389 mg; mean weight of healthy adult FVB/N spleen, 101 mg; liver, 1080 mg). Of note, we did not observe the lung hemorrhages that have been reported in recipient mice of bone marrow transduced with activated tyrosine kinases, including TEL-PDGFβR and TEL-JAK2.44,45 In addition, the lymph nodes were infiltrated by leukemic cells, and, similar to what we had observed in PML-RARα leukemias, lymph nodes were dark green, indicative of high levels of myeloperoxidase in the tissue. Cells harvested from leukemic animals readily transmitted the disease to sublethally irradiated FVB/N recipients. For each of 4 leukemias, cells were injected intravenously into 3 to 4 recipient mice. All animals became ill (median latency, 38 days; range, 33-59 days); these results are similar to those obtained for transplantation of leukemias fromMRP8 PML-RARA transgenic mice (median latency, 34 days; range, 31-60 days).46 Interestingly, leukocytosis was not a common feature of transplant recipients of activated FLT3/PML-RARα or PML-RARα leukemias, but the peripheral blood of secondary recipients of activated FLT3/PML-RARα leukemias did contain substantial numbers of circulating leukemic cells (data not shown and see Figure 6).

Overall, the predominant disease that arose in activated FLT3/PML-RARα animals was AML. In 3 of 8 cases analyzed, the leukemias would be classified as AML without maturation, whereas in 5 mice the marrows showed a modest amount of differentiation and would be classified as AML with maturation.40 Thus, like human APL, the state of differentiation of these leukemias bordered between AML without and AML with maturation.

The survival curve for activated FLT3/PML-RARα shown in Figure 1includes 2 animals that did not have typical leukemia. The first of these appeared ill on day 47 after transplantation. Necropsy examination including hematologic studies did not identify the cause for this animal's illness. The second of these animals appeared ill on day 66 after transplantation. At this time, though the mouse did not have disseminated myeloid leukemia, a limited area of the spleen was filled with immature forms/blasts, and the transplantation of cells to 2 sublethally irradiated recipient animals generated leukemias in 45 and 51 days. Thus, of 15 animals in the activated FLT3/PML-RARα group, 1 became ill for unclear reasons, 12 developed leukemia, 1 had a preleukemic or early leukemic condition, and 1 animal that survived more than 144 days could not be evaluated for disease.

Activated FLT3/PML-RARα leukemias exhibit clonal cytogenetic abnormalities

We previously observed that leukemias of MRP8 PML-RARA transgenic mice exhibited recurring clonal cytogenetic abnormalities.30 The addition of BCL-2 to PML-RARα, either as an MRP8 transgene or by retroviral transduction ofPML-RARA transgenic bone marrow, accelerated leukemogenesis and was associated with complex karyotypic abnormalities. In contrast, though all the leukemias that developed in activated FLT3/PML-RARα mice exhibited clonal karyotypic abnormalities (Table3), the cytogenetically abnormal clones were simpler than what we had seen in PML-RARα and BCL-2/PML-RARα mice.30 The abnormalities observed were gain of chromosome 15 in 3 mice, gain of chromosome 10 in 3 mice, and gain of chromosome 7 in 2 mice. Six mice showed loss of an X chromosome. All 7 mice had a single abnormal clone. Southern blotting of leukemic samples was consistent with the cytogenetic results in demonstrating 1 or 2 predominant retroviral integration sites in the samples (data not shown).

Cytogenetic analysis of murine FLT3W51/PML-RARα leukemias

| Mouse . | Karyotype . |

|---|---|

| 747 | 41,XY,+15[7]/40,XY[3] |

| 1019 | 40,X,−X,+15[10]/NCA: 39,idem,der(10;14)(A1;A1)[1] |

| 1020 | 40,X,−X,+10[10] |

| 1086 | 41,X, −X,+7,+10[9]/40,XX[1] |

| 1087 | 40,X, −X,+10[4]/40,XX[5]/NCA:38,XX,t(8;19)(C3;B), −12, −13,der(18)t(13;18)(B;E1)[1] |

| 1127 | 40,X, −X,+7[8]/40,XX[2]/NCA:40, idem, −9,+14[1]/38,idem, −8,der(12;18)(A1;A1)[1] |

| 1128 | 40,X, −X,+15[10] |

| Mouse . | Karyotype . |

|---|---|

| 747 | 41,XY,+15[7]/40,XY[3] |

| 1019 | 40,X,−X,+15[10]/NCA: 39,idem,der(10;14)(A1;A1)[1] |

| 1020 | 40,X,−X,+10[10] |

| 1086 | 41,X, −X,+7,+10[9]/40,XX[1] |

| 1087 | 40,X, −X,+10[4]/40,XX[5]/NCA:38,XX,t(8;19)(C3;B), −12, −13,der(18)t(13;18)(B;E1)[1] |

| 1127 | 40,X, −X,+7[8]/40,XX[2]/NCA:40, idem, −9,+14[1]/38,idem, −8,der(12;18)(A1;A1)[1] |

| 1128 | 40,X, −X,+15[10] |

NCA indicates nonclonal abnormal cell.

Activated FLT3 does not readily initiate myeloproliferative disease in FVB/N mice

Previously, the FLT3W51 retrovirus we used in these studies was shown to induce myeloproliferative disease when BALB/c bone marrow was transduced using a protocol similar to that used in the current study.31 This MPD was characterized by increased numbers of myeloid cells with retained maturation, and it contrasted with the AMLs we observed in FLT3W51/PML-RARA mice in the FVB/N strain background. In contrast to what was observed in BALB/c mice, none of the recipients of control FVB/N bone marrow transduced with the FLT3W51 construct developed myeloproliferative disease.

Five of 12 recipients of control bone marrow transduced with activated FLT3 did become ill. One such mouse became ill at 75 days because of intestinal distention, and other recipients appeared ill at 117, 168, and 308 days, at which times pathology examination did not reveal any specific abnormalities. Of particular interest was one animal that became ill 175 days after transplantation because of a thoracic T-cell malignancy (presumptive diagnosis, T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma) that showed strong expression of GFP. We also observed T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia lymphomas when activated FLT3 was introduced into a mixed B6 × C3H strain of mice.43 Remaining activated FLT3/control recipients do not show evidence of MPD in their peripheral blood 250 to 419 days after transplantation.

Activated FLT3/PML-RARα leukemias respond to retinoic acid

To assess the effects of ATRA on acute myeloid leukemias that express PML-RARα and activated FLT3, we treated sublethally irradiated mice that had been injected with activated FLT3/PML-RARα leukemic cells. Mice received either placebo or ATRA pellets (10 mg, 21-day release). In one experiment, ATRA pellets were implanted 12 days after the injection of leukemic cells. ATRA prolonged survival (median prolongation of survival, 29 days; Figure5A). In an ensuing experiment, treatment was begun earlier (6 days after injection of leukemic cells). Not surprisingly, the increase in survival with ATRA was longer when therapy was begun on day 6 (median prolongation in survival, 52 days; Figure 5B). These results were not markedly different from those of a previous study on PML-RARα leukemia without the FLT3 mutation, for which we observed that implantation of 10-mg ATRA pellets on day 12 after injection prolonged survival a median of 41 days.47

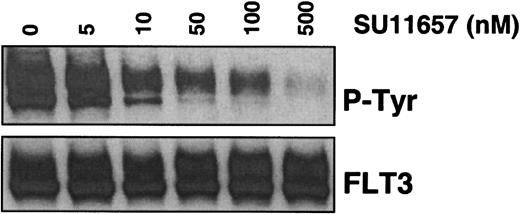

SU11657, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, blocks autophosphorylation of FLT3 with ITD mutation

MV 4;11 cells express FLT3 with an ITD mutation and were treated with SU11657, a novel receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Immunoprecipitation with an FLT3-specific antibody, followed by Western blot analysis with an antiphosphotyrosine antibody, demonstrated dose-dependent inhibition of autophosphorylation of FLT3 with an IC50 of approximately 50 nM (Figure4).

SU11657 inhibits activated FLT3.

MV 4;11 cells were incubated with SU11657 at the indicated concentration for 2 hours. Lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLT3 antibody. After SDS-PAGE and transfer to nitrocellulose, blots were probed with an antiphosphotyrosine antibody (top) and subsequently stripped and reprobed with an anti-FLT3 antibody (bottom). The IC50 for inhibition of FLT3-ITD phosphorylation is approximately 50 nM.

SU11657 inhibits activated FLT3.

MV 4;11 cells were incubated with SU11657 at the indicated concentration for 2 hours. Lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLT3 antibody. After SDS-PAGE and transfer to nitrocellulose, blots were probed with an antiphosphotyrosine antibody (top) and subsequently stripped and reprobed with an anti-FLT3 antibody (bottom). The IC50 for inhibition of FLT3-ITD phosphorylation is approximately 50 nM.

SU11657 alters the response of leukemias to ATRA and rapidly restores normal hematopoiesis

To move toward the development of a therapeutic regimen in which combination therapy with ATRA and a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, SU11657, would be more efficacious than with ATRA alone, we investigated the effects of these agents in vivo after a short course of therapy. Matched recipients of FLT3/PML-RARα leukemic cells were treated with ATRA, SU11657, or both beginning on day 12 after injection. After 4 days of therapy, animals were killed and analyzed.

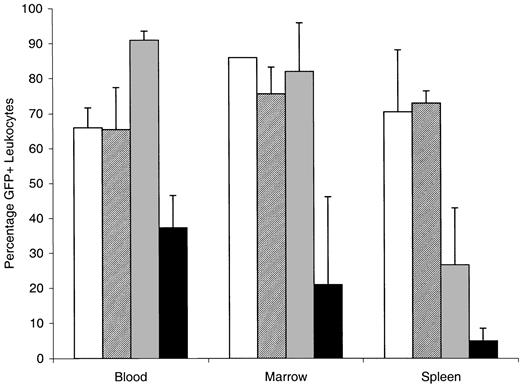

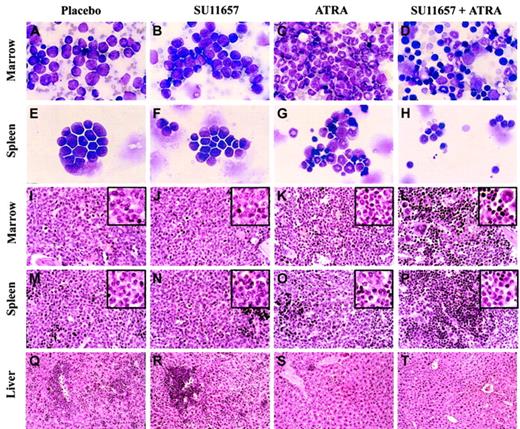

Combination therapy with ATRA and SU11657 had a dramatic ability to cause regression of the leukemia and to restore normal hematopoiesis. Spleen and liver weights, correlated with the degree of involvement by leukemia, were reduced through treatment (Table4). Reduction in splenic involvement by leukemia was also apparent by decreased GFP expression (Figure6). ATRA alone decreased splenic involvement from 71% to 30%, and combined therapy nearly eliminated leukemic cells from the spleen (only 5% of splenic WBCs expressed GFP). Considering the reduction in splenic weight and the reduction of GFP-positive leukocytes, SU11657 + ATRA eliminated, on average, 99% of leukemic cells from the spleen. Combination therapy decreased GFP-positive cells in the blood and bone marrow as well, but, interestingly, ATRA therapy did not. In fact, ATRA therapy was associated with increasing numbers of blood cells that expressed GFP, reflecting the differentiation of leukemic cells to mature circulating neutrophils. Cytology and histopathology examination of bone marrow, spleen, and liver revealed the cellular effects of the treatments (Figure 7). SU11657 had minimal morphologic effects (compare Figure 7 column 1 with Figure 7column 2). Although in vitro the inhibition of FLT3 has been associated with apoptosis, by histopathology we did not observe any substantive increase in the number of apoptotic cells compared with the moderate numbers seen in placebo-treated mice. We cannot, however, exclude the possibility of a small increase in apoptosis in vivo. ATRA alone caused differentiation of the leukemic cells. The bone marrow was filled with maturing granulocytes (Figure 7C,K). Differentiation was also observed in the spleen, accompanied by a relative increase in erythroid and lymphoid cells (Figure 7G,O). There was regression of disease from the liver (Figure 7S). The addition of SU11657 to ATRA dramatically accelerated disease regression and restoration of normal bone marrow hematopoiesis. Marrows of mice treated with ATRA and SU11657 were filled with a heterogeneous mixture of myeloid, megakaryocytic, and lymphoid elements, along with prominent erythropoiesis (Figure 7D,L). Leukemia was markedly reduced in the spleen (Figure 7H,P; H shows normal splenic lymphocytes) and was eliminated from the liver (Figure7T).

Combination therapy with ATRA and SU11657 causes rapid reduction of organ size in leukemic animals

| . | Weight, mg . | |

|---|---|---|

| . | Spleen . | Liver . |

| Placebo | 637 ± 55 | 2593 ± 480 |

| SU11657 | 403 ± 98 | 1950 ± 156 |

| ATRA | 193 ± 56 | 1420 ± 170 |

| SU11657 + ATRA | 90 ± 14 | 1373 ± 95 |

| . | Weight, mg . | |

|---|---|---|

| . | Spleen . | Liver . |

| Placebo | 637 ± 55 | 2593 ± 480 |

| SU11657 | 403 ± 98 | 1950 ± 156 |

| ATRA | 193 ± 56 | 1420 ± 170 |

| SU11657 + ATRA | 90 ± 14 | 1373 ± 95 |

Recipients of leukemic cells were treated for 4 days beginning day 12 after injection. Means ± standard deviations are shown; n = 3 for each group. There was a trend toward smaller spleens and livers in mice treated with SU11657. Organ weights were significantly reduced by ATRA and SU11657 + ATRA treatment (P < .05).

FLT3W51/PML-RARα leukemias respond to ATRA.

Cohorts of histocompatible healthy FVB/N mice were sublethally irradiated and injected with 1 × 106 leukemic cells (n = 5 for all cohorts). (A) ATRA or placebo pellets (10 mg, 21-day release) were implanted on day 12 after injection. (B) ATRA or placebo pellets (10 mg, 21-day release) were implanted on day 6 after injection. Placebo versus ATRA, P = .002 (by log-rank).

FLT3W51/PML-RARα leukemias respond to ATRA.

Cohorts of histocompatible healthy FVB/N mice were sublethally irradiated and injected with 1 × 106 leukemic cells (n = 5 for all cohorts). (A) ATRA or placebo pellets (10 mg, 21-day release) were implanted on day 12 after injection. (B) ATRA or placebo pellets (10 mg, 21-day release) were implanted on day 6 after injection. Placebo versus ATRA, P = .002 (by log-rank).

FLT3 inhibition combines with ATRA to cause regression of leukemia.

Sublethally irradiated mice that were recipients of activated FLT3/PML-RARα leukemic cells were treated with 10 mg ATRA or placebo pellets. After 4 days of treatment, mice were analyzed. Percentages of leukocytes that expressed GFP in blood, bone marrow, and spleen are shown. ■ indicates placebo; ▨, SU11657; ░, ATRA; and ▪, ATRA + SU11657. Error bars represent standard deviation.

FLT3 inhibition combines with ATRA to cause regression of leukemia.

Sublethally irradiated mice that were recipients of activated FLT3/PML-RARα leukemic cells were treated with 10 mg ATRA or placebo pellets. After 4 days of treatment, mice were analyzed. Percentages of leukocytes that expressed GFP in blood, bone marrow, and spleen are shown. ■ indicates placebo; ▨, SU11657; ░, ATRA; and ▪, ATRA + SU11657. Error bars represent standard deviation.

FLT3 inhibition cooperates with ATRA to rapidly restore normal hematopoiesis.

Cytology and histopathology of representative mice treated as described in the legend to Figure 6. (A-D) Bone marrow cytology. ATRA causes differentiation of leukemic immature forms/blasts to neutrophilic cells, whereas SU11657 + ATRA restores a heterogeneous bone marrow with healthy elements. (E-H) Splenic cytology. ATRA-induced differentiation is evident along with normal lymphocytes and erythroid cells. SU11657 + ATRA spleen contains many healthy small lymphocytes. (I-L) Bone marrow histopathology. Findings are consistent with those observed in cytology preparations. (M-P) Splenic histopathology. SU11657 + ATRA restores normal splenic architecture. (Q-T) Liver histopathology. ATRA and SU11657 + ATRA cause marked regression of the leukemia from the liver. Wright-Giemsa stain; original magnification × 250 (A-H). Hematoxylin and eosin stain (I-T). Original magnification × 125; insets × 250 (I-P). Original magnification × 50 (Q-T).

FLT3 inhibition cooperates with ATRA to rapidly restore normal hematopoiesis.

Cytology and histopathology of representative mice treated as described in the legend to Figure 6. (A-D) Bone marrow cytology. ATRA causes differentiation of leukemic immature forms/blasts to neutrophilic cells, whereas SU11657 + ATRA restores a heterogeneous bone marrow with healthy elements. (E-H) Splenic cytology. ATRA-induced differentiation is evident along with normal lymphocytes and erythroid cells. SU11657 + ATRA spleen contains many healthy small lymphocytes. (I-L) Bone marrow histopathology. Findings are consistent with those observed in cytology preparations. (M-P) Splenic histopathology. SU11657 + ATRA restores normal splenic architecture. (Q-T) Liver histopathology. ATRA and SU11657 + ATRA cause marked regression of the leukemia from the liver. Wright-Giemsa stain; original magnification × 250 (A-H). Hematoxylin and eosin stain (I-T). Original magnification × 125; insets × 250 (I-P). Original magnification × 50 (Q-T).

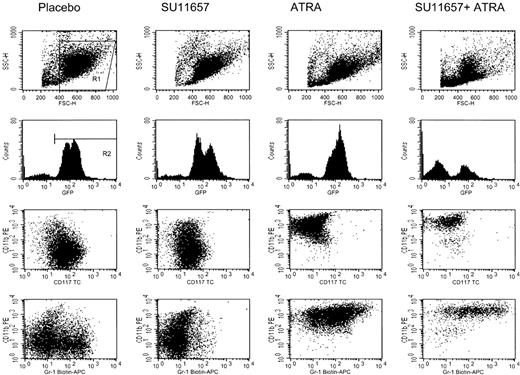

Flow cytometric immunophenotyping of GFP-positive cells remaining in the spleen (Figure 8) demonstrated that untreated cells of this leukemia expressed CD117 (c-kit), low levels of CD11b (Mac-1), and heterogeneous Ly-6G (Gr-1). SU11657 had a modest effect on surface immunophenotype (small increase in CD11b, loss of Ly-6G–positive leukemic population), and both ATRA and SU11657 + ATRA caused immunophenotypic differentiation (loss of CD117, increased CD11b and Ly-6G). These results, showing that a short course of SU11657 synergized with ATRA to restore normal hematopoiesis, will serve as the basis for additional preclinical studies in which ATRA will be combined with multiple short courses of SU11657.

ATRA causes immunophenotypic differentiation of leukemic cells.

Representative flow cytometry of splenic cells harvested from mice treated as described in the legend to Figure 6. Histograms are gated on R1. Dot plots are gated on R1 and R2 and, therefore, represent the GFP-positive leukemic cells. ATRA causes a loss of the immature marker CD117 (c-kit) and increased expression of the mature myeloid markers CD11b (Mac-1) and Ly-6G (Gr-1).

ATRA causes immunophenotypic differentiation of leukemic cells.

Representative flow cytometry of splenic cells harvested from mice treated as described in the legend to Figure 6. Histograms are gated on R1. Dot plots are gated on R1 and R2 and, therefore, represent the GFP-positive leukemic cells. ATRA causes a loss of the immature marker CD117 (c-kit) and increased expression of the mature myeloid markers CD11b (Mac-1) and Ly-6G (Gr-1).

Discussion

Although the creation of the PML-RARA fusion gene is the central genetic event in APL, this fusion is insufficient for leukemogenesis. Expression of PML-RARA in myeloid cells of transgenic mice initially causes only a modest increase in immature neutrophilic cells, and leukemias appear only after a long latency (median, 8.5 months in MRP8 PML-RARA transgenic mice). Activating mutations of FLT3 are a common additional genetic change in APL. Our results demonstrate that the coexpression of an activated FLT3 allele accelerates the appearance of leukemia in mice that express a PML-RARA transgene and that inhibiting FLT3 in combination with using ATRA to neutralize the effect of PML-RARα may have a future role in the treatment for APL patients with FLT3 mutations.

PML-RARα impairs the ability of myeloid cells to differentiate, in part by blocking RAR activity, and also enhances proliferation and survival of myeloid cells by interfering with PML activity. In the absence of additional genetic changes, these effects of PML-RARα nevertheless do not convert healthy hematopoietic cells to acute leukemia. The limited effect of PML-RARα expression likely reflects the fact that cells expressing this protein remain subject to normal growth controls. Events such as the activation of FLT3 abrogate the normal regulatory mechanisms that control the survival and proliferation of immature myeloid cells. Only in the presence of such additional mutations is the ability of PML-RARα to block differentiation manifested. It is possible that the activation of FLT3 itself contributes to this differentiation block.48

It is notable that the leukemias that arose in activated FLT3/PML-RARα mice were characterized by increased white blood cell counts, whereas those that arose spontaneously in MRP8 PML-RARA transgenic mice had normal white blood cell counts. Thus, the presence of an activated cytokine receptor influenced the phenotype of the primary leukemias. This observation is in accord with the association of activated FLT3 with leukocytosis in patients with APL.13 Cytokines are used clinically to mobilize immature cells before peripheral blood stem cell harvests, and it may be that FLT3 activation mobilizes leukemic cells out of the bone marrow into the peripheral blood. Recently, the mobilization of healthy progenitors by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor has been linked to the cleavage of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1.49 It will be of interest to assess whether activating mutations of FLT3 similarly alter the expression of adhesion molecules in mouse and human leukemias. Further evidence for the idea that activation of cytokine receptors may be responsible for the leukocytosis associated with FLT3 mutations is provided by the observation that treatment of MRP8 PML-RARA leukemic mice with GM-CSF results in rapid and profound leukocytosis (H. de Thé, unpublished observations, 2002).

Although we have previously identified several recurring cytogenetic abnormalities in the leukemias of MRP8 PML-RARA mice, the particular genetic changes responsible for completing transformation are unknown. That these leukemias do not usually exhibit leukocytosis suggests that activation of FLT3 or other cytokine receptors is not a common, spontaneously occurring secondary abnormality in these mice. Further investigations may reveal whether the cooperating spontaneous genetic changes in this mouse model of APL, and in human APL without FLT3 mutations, have molecular effects in common with FLT3 activation or, alternatively, reflect a distinct route to leukemic transformation.

We had observed that the combination of BCL-2 and PML-RARα was not sufficient for leukemic transformation and hypothesized that the combination of PML-RARα with antiapoptotic plus proliferative signals would be sufficient to induce the leukemic phenotype. We therefore anticipated that the combination of activated FLT3 and PML-RARα would be rapidly transforming, and, as such, we expected that clonal cytogenetic lesions would not be present in the activated FLT3/PML-RARα leukemias. In contradistinction to this expectation, clonal karyotypic abnormalities were present in each of the activated FLT3/PML-RARα leukemias. The presence of these clonal abnormalities could indicate that additional genetic changes are required. It is notable that the activated FLT3/PML-RARα leukemias were characterized by a single abnormal clone with simple karyotypic abnormalities (1-2 numerical abnormalities) as compared with the greater karyotypic complexity observed in MRP8 PML-RARA andPML-RARA/BCL2 leukemias. We interpret this finding to mean that activated FLT3 alters the transformation pathway, thereby abrogating the requirement for more extensive additional genetic changes, as reflected by cytogenetics. Nevertheless, loss of a sex chromosome and gains of chromosomes 7, 10, and 15 were seen not only in activated FLT3/PML-RARα leukemias but also previously in MRP8 PML-RARA and PML-RARA/BCL2 leukemias. Gains of these chromosomes may be intrinsic to the process of transformation. Alternatively, these chromosomal gains might instead provide a significant growth or survival advantage to leukemic cells, thereby permitting rapid clonal outgrowth. Identifying the genes that drive chromosomal gain in human and mouse myeloid leukemias may offer insight into pathogenesis or progression and could provide new therapeutic targets.

Although activated FLT3 can induce myeloproliferative disease in BALB/c mice, we did not observe this illness in recipients of control FVB/N bone marrow transduced with FLT3W51 retrovirus. Although this could reflect slight technical differences, rates of bone marrow transduction in the current study were comparable to those in the previous study in BALB/c (data not shown). We suspect that the difference in the 2 strains reflects a relative sensitivity in the BALB/c background to MPD. Consistent with this idea, the expression of FLT3W51 in a mixed B6 × C3H strain background also did not result in MPD.43 Elucidating the strain-specific differences that underlie susceptibility to activated FLT3-induced MPD is an area of active investigation (L.M.K., D.G.G., unpublished observations, 2002). Studies of bone marrow transduction withBCR-ABL–expressing retroviruses had previously demonstrated significant strain effects.50 Hence, it is possible that genetic variation in the human population may likewise influence susceptibility to myeloid neoplasms when potentially pathogenic mutations occur.

The present study complements a study using cathepsin G PML-RARA transgenic mice43 to show that the cooperative effect of activated FLT3 on PML-RARα–initiated acute leukemia is independent of transgene insertion site, promoter, and strain background. We note that whereas the primary leukemias in activated FLT3/MRP8 PML-RARA mice exhibited clonal cytogenetic lesions and dominant retroviral insertion sites, the primary leukemias in activated FLT3/cathepsin G PML-RARAmice showed multiple retroviral insertion sites but decreased complexity on transplantation. A possible explanation for this difference lies in a difference between the cathepsin G PML-RARA and MRP8 PML-RARA models: cathepsin G PML-RARA mice showed progressive myeloid proliferation with splenomegaly from which leukemia may eventually arise, whereasMRP8 PML-RARA mice did not exhibit substantial splenomegaly before the onset of leukemia. Thus the oligo-clonality observed in the activated FLT3/cathepsin G PML-RARA model might reflect preleukemic clonal expansion of multiple transduced cells. The relatively long latency of disease in both models in combination with the development of monoclonal lesions (either initially or on transplantation) raises the possibility that PML-RARα plus activated FLT3 is insufficient to convert healthy cells to fully transformed leukemia cells. The fact that FLT3 mutations may be present at diagnosis and absent in relapsed samples is at least consistent with the idea that other genetic changes might work together with PML-RARα and activated FLT3 to complete transformation.51-53

These 2 mouse models are proving useful for the development of therapeutic strategies that incorporate FLT3 inhibitors. The ability to assess the efficacy of various therapeutic approaches on independent leukemias in different strain backgrounds should enhance the likelihood that such strategies will be successful when applied to the heterogeneous human population.

Activating mutations of FLT3 are common in AML, and previous work has shown that FLT3 inhibition represents a promising avenue for novel therapy.42 54-57 We have investigated the possible application of the inhibition of FLT3 to treatment for APL. We found that SU11657, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor able to block FLT3 activity, had only a modest effect when used as a single agent but that it synergized with ATRA to rapidly cause disease regression. SU11657 altered the effect of ATRA. ATRA alone caused the differentiation of leukemic blasts into numerous mature neutrophils. In the presence of SU11657, ATRA caused some differentiation, but its major effect was to rapidly reduce leukemic cell mass. Our observations suggest that combination therapy could potentially reduce the incidence of side effects of ATRA therapy, including retinoic acid syndrome, and might decrease early fatalities by hastening remission. There could also be a positive impact on long-term survival. Additional studies of FLT3 inhibition in our mouse models of APL should lead to treatment strategies that enhance cure. Use of these models will allow the development of novel treatment regimens that will facilitate subsequent human clinical trials.

We thank J. Michael Bishop, Daphne A. Haas-Kogan, H. Jeffrey Lawrence, Frank McCormick, and Kevin M. Shannon for their continuing support.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, December 19, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1800.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants K08-CA75986 (S.C.K), U01-CA84221 (S.C.K., M.M.L.), CA66996, (D.G.G.), and DK50654 (D.G.G.) and by a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society SCOR grant (D.G.G.). S.C.K. is the 32nd Edward Mallinckrodt Junior Scholar and is a recipient of a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award. L.M.K. is a Fellow of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. D.G.G. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

T.J.A. and A.M.O. are employed by Sugen Inc, whose potential product (SU11657) is studied in the present work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Scott C. Kogan, Comprehensive Cancer Center, Rm N-361, Box 0128, University of California at San Francisco, 2340 Sutter St, San Francisco, CA 94143-0128; e-mail:skogan@cc.ucsf.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal