Key Points

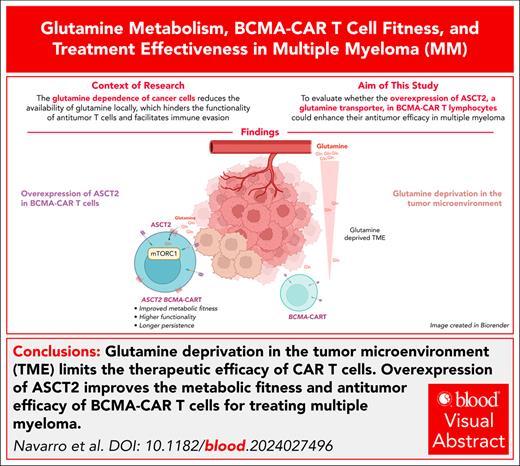

Glutamine deprivation in the tumor microenvironment might limit CAR T-cell therapeutic efficacy in patients with cancer.

ASCT2 overexpression improves the metabolic fitness and antitumor efficacy of BCMA-CAR T-cell therapy for MM treatment.

Visual Abstract

Glutamine dependence of cancer cells reduces local glutamine availability, which hinders antitumor T-cell functionality and facilitates immune evasion. We thus speculated that glutamine deprivation might be limiting efficacy of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies in patients with cancer. We have seen that antigen-specific T cells are unable to proliferate or produce interferon gamma (IFN-γ) in response to antigen stimulation when glutamine concentration is limited. Using multiple myeloma (MM) as a glutamine-dependent disease model, we found that murine CAR T cells selectively targeting B-cell maturation antigen (Bcma) in MM cells were sensitive to glutamine deprivation. However, CAR T cells engineered to increase glutamine uptake by expression of the glutamine transporter Asct2 exhibited enhanced proliferation and responsiveness to antigen stimulation, increased production of IFN-γ, and heightened cytotoxic activity, even under conditions of low glutamine concentration. Mechanistically, Asct2 overexpression reprogrammed the metabolic fitness of CAR T cells by upregulating the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 gene signature, modifying the solute carrier transporter repertoire, and improving both basal oxygen consumption rate and glycolytic function, thereby enhancing CAR T-cell persistence in vivo. Accordingly, expression of Asct2 increased the efficacy of Bcma-CAR T cells in syngeneic and genetically engineered mouse models of MM, which prolonged mouse survival. In patients, higher-level expression of ASCT2 by MM cells predicted poor outcome to combined immunotherapy and BCMA-CAR T-cell therapy. Our results indicate that reprogramming glutamine metabolism may enhance antitumor CAR T-cell functionality in MM. This approach may also be effective for other cancers that depend on glutamine as a key energy source and metabolic hallmark.

Introduction

Chimeric antigen-specific receptor (CAR) T-cell immunotherapy specific for B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA; BCMA-CAR T cells) has shown impressive results against advanced multiple myeloma (MM), with many patients achieving complete responses.1,2 However, many patients relapse within a few months due to the lack of CAR T-cell persistence, which is a potential mechanism of acquired resistance.3 One of the main obstacles to achieve a persistent response is the tumor microenvironment (TME), which is significantly altered due to the tumor’s aberrant metabolism.4 Aggressive tumors often rely on glycolysis even in nonhypoxic conditions, a phenomenon known as the Warburg effect.5 Additionally, many tumor types, specially MM, have a high dependency on glutamine (Gln) metabolism for cell survival and growth.6,7 This reliance on Gln has led MM to be defined as “Gln addicted.”

In this scenario, the MM tumor interstitial fluid is thought to be Gln depleted compared with either normal tissues or the circulation.8 Similar to tumor cells, the activation and proliferation of antitumor T lymphocytes rely heavily on Gln.9,10 Unfortunately, lymphocytes are less efficient than tumor cells in transporting Gln, impairing their persistence and antitumor activity under Gln-deprived conditions. We found that antigen-specific T cells cannot proliferate or produce interferon gamma (IFN-γ) with limited Gln, unless engineered to overexpress the transporter Asct2 (Slc1a5). Bcma-targeting CAR T cells are also vulnerable to Gln deprivation, but when modified to overexpress Asct2, they show improved antitumor activity in a mouse model of human-like MM that reflects the key elements in the pathogenesis of the disease.11 This enhancement is associated to better metabolic fitness, longer persistence, and improved functionality.

Methods

ACT experiments

In the B16OVA model, C57BL/6 mice (aged 6-12 weeks) were subcutaneously challenged with 5 × 105 B16OVA melanoma cells. Seven days later, mice received a total body irradiation (TBI) of 4 Gy, and adoptive cell transfer (ACT) immunotherapy with 5 × 106Asct2-overexpressing or control CD8+ OT-I T cells. Interleukin-2 (IL-2; 20 000 IU per mouse) was administered for 4 consecutive days after ACT. Tumor volume was estimated using a caliper and the formula [(length × width2)/2]. For immune characterization experiments, 14 days after ACT, mice were euthanized to analyze the presence of tumor-infiltrating T cells, and circulating antigen-specific T cells by flow cytometry and immunospot.

In the 5080 MM model, C57BL/6 mice were injected with 6 × 106 5080 MM cells IV. After 7 days, they received 2.5 Gy TBI and were treated with 5 × 105Asct2-overexpressing or control CD8+ and CD4+Bcma-CAR T cells (1 × 106 total) and IL-2. Mice were euthanized 7 and 14 days after treatment for immune analysis by flow cytometry.

In the MIC-γg1 genetic MM model (described previously11), 170-day-old mice were assessed for disease levels by serum γ-globulin fraction and grouped accordingly. They received 2.5 Gy TBI and ACT immunotherapy with 3 × 106 CD8+ and 3 × 106 CD4+ control or Asct2-overexpressing Bcma-CAR T cells (6 × 106 total), along with IL-2. Blood samples were taken weekly to monitor disease progression via γ-globulin fractions.

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxic activity of OT-I and OT-II T cells against B16OVA, as well as mouse and human BCMA-CAR T cells against 5080 MM and H929 MM, was evaluated using flow cytometry. T cells were cocultured with tumor cells at various effector-to-tumor ratios in media with decreasing Gln concentrations for 18 hours. Following staining with anti–CD8-allophycocyanin or anti–CD4-phycoerythrin antibodies, Cytognos counting beads were added. Flow cytometry was used to determine the remaining tumor cells and calculate percentage lysis.

Seahorse

The Seahorse XFp microplates were coated with 22.4 μg/mL Cell-Tak in 0.1 M NaHCO3. Control or Asct2-overexpressing T cells were resuspended in Seahorse XF Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (pH 7.4) containing 15 mM glucose, 1 mM pyruvate, and 2 mM Gln. 100 000 T cells were cultured in Seahorse medium, and incubated at 37°C and 0% CO2 for 20 minutes and analyzed using the Agilent Seahorse XF. In some experiments, T cells were preincubated for 60 minutes with saline, 2-DG (2-deoxy-d-glucose; 2 mM), or BPTES [bis-2-(5-phenylacetamido-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)ethyl sulfide] (10 μM) before the analysis. Adenosine triphosphate production rate was measured according to the manufacturer’s instructions, using 1 μM oligomycin, 1.5 μM FCCP (carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone), 1 μM antimycin/rotenone, and 50 mM 2-DG, all from Sigma. Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) data were normalized to the protein content as assessed by the Bradford assay from Bio-Rad.

Statistics

Data are presented as averages ± standard error of the mean. Statistical comparisons between 2 groups of normally distributed variables used Student t tests, whereas 1-way or 2-way analysis of variance with Tukey post hoc test was used for >2 groups. Tumor growth data were analyzed using nonlinear cubic regression curves. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were assessed for significance with the log-rank Mantel-Cox test. A P value of <.05 was considered significant. GraphPad Prism software was used for analysis.

For detailed procedures on T-cell purification and activation, viral transduction, and other analyses such as flow cytometry and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), please refer to the supplemental Materials and methods, available on the Blood website.

All animal handling and tumor experiments were conducted under the institutional guidelines of our ethics committee (protocol R-018-19).

Results

Asct2 overexpression improves effector T-cell function

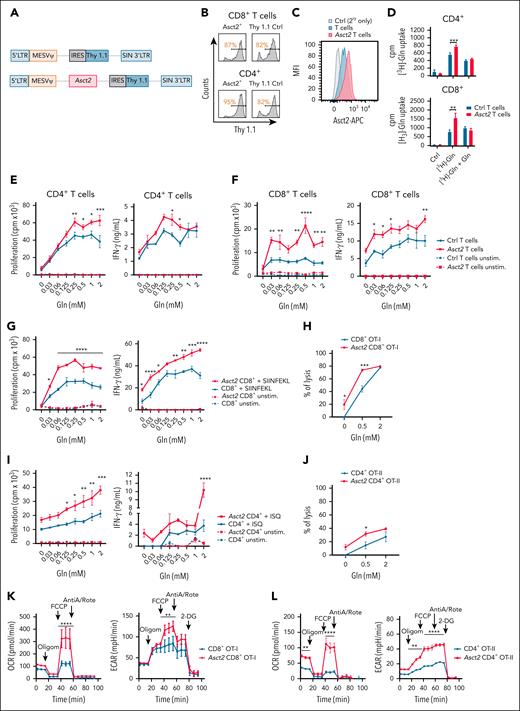

The activation and proliferation of T cells is highly dependent on Gln.8,9 To study the potential beneficial effect of Asct2 overexpression on T cells, we cloned Asct2 in the MSCV-IRES-Thy1.1 vector to express Asct2 and the Thy1.1 (CD90.1) transduction marker (Figure 1A). CD8+ and CD4+ T cells from C57BL/6 mice were infected, and transduction efficiency was confirmed by measurement of Thy1.1 expression (Figure 1B). Higher expression of Asct2 was observed in Asct2-Thy1.1 infected T cells compared with Thy1.1 or inactivated control T cells (Figure 1C). It is worth mentioning that control T cells also express detectable Asct2 levels, because it is physiologically expressed in most cells.12

Asct2 overexpression on T cells enhances the function of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells cultured under low and high Gln concentrations. (A) Diagrams of retroviral vectors designed to overexpress Asct2 in T cells. (B) Transduction efficiency (Thy 1.1+) in CD8+ and CD4+ T cells assessed by flow cytometry. (C) Asct2 expression on the transduced T cells’ membrane measured by flow cytometry. (D) 3H-labeled Gln uptake by transduced CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. (E-F) Proliferation and IFN-γ secretion of Ctrl and Asct2-overexpressing CD4+ (E) and CD8+ (F) T cells activated with anti-CD3/CD28 beads under different Gln concentrations (0-2 mM). (G-J) Proliferation, IFN-γ secretion, and specific B16OVA lysis of Ctrl and CD8+ Asct2–OT-I T cells (G-H), and CD4+Asct2–OT-II T cells (I-J) under different Gln concentrations. (K-L) Seahorse metabolic assay was used to measure the OCR and the ECAR of Ctrl and Asct2-overexpressing CD8+ OT-I T cells (K), and CD4+ OT-II T cells (L). Data are representative of 2 to 3 independently repeated experiments. Data represent mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and were analyzed using 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni multiple comparisons test (∗∗∗∗P < .0001; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗P < .01; ∗P < .05). AntiA/Rote, antimycin/rotenone; APC, allophycocyanin; cpm, counts per minute; Ctrl, control; LTR, long termi; MFI, mean fluoresecence intensity; Oligom, oligomycin; unstim, unstimulated.

Asct2 overexpression on T cells enhances the function of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells cultured under low and high Gln concentrations. (A) Diagrams of retroviral vectors designed to overexpress Asct2 in T cells. (B) Transduction efficiency (Thy 1.1+) in CD8+ and CD4+ T cells assessed by flow cytometry. (C) Asct2 expression on the transduced T cells’ membrane measured by flow cytometry. (D) 3H-labeled Gln uptake by transduced CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. (E-F) Proliferation and IFN-γ secretion of Ctrl and Asct2-overexpressing CD4+ (E) and CD8+ (F) T cells activated with anti-CD3/CD28 beads under different Gln concentrations (0-2 mM). (G-J) Proliferation, IFN-γ secretion, and specific B16OVA lysis of Ctrl and CD8+ Asct2–OT-I T cells (G-H), and CD4+Asct2–OT-II T cells (I-J) under different Gln concentrations. (K-L) Seahorse metabolic assay was used to measure the OCR and the ECAR of Ctrl and Asct2-overexpressing CD8+ OT-I T cells (K), and CD4+ OT-II T cells (L). Data are representative of 2 to 3 independently repeated experiments. Data represent mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and were analyzed using 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni multiple comparisons test (∗∗∗∗P < .0001; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗P < .01; ∗P < .05). AntiA/Rote, antimycin/rotenone; APC, allophycocyanin; cpm, counts per minute; Ctrl, control; LTR, long termi; MFI, mean fluoresecence intensity; Oligom, oligomycin; unstim, unstimulated.

Then the Gln transport activity of Asct2 was confirmed in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells using stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture media supplemented with [3H]-radiolabeled Gln. Asct2-overexpressing T cells showed a higher uptake of [3H]-Gln compared with Thy1.1 control T cells. When nonradiolabeled Gln was added, the uptake of [3H]-Gln decreased in both groups, indicating competition between labeled and nonlabeled Gln (Figure 1D).

To assess the impact of enhanced Gln uptake on T-cell function, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from C57BL/6 mouse spleens were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 beads at varying Gln concentrations. Asct2 overexpression significantly improved T-cell proliferation and IFN-γ production (Figure 1E for CD4+; Figure 1F for CD8+ T cells). Similar enhancements were seen in CD8+ OT-I and CD4+ OT-II T cells (Figure 1G,I). Asct2 -overexpressing OT-I T cells showed increased lysis of B16OVA cells, even at low Gln levels (Figure 1H), and Asct2-overexpressing CD4+ OT-II T cells were more efficient at lysing B16OVA cells at 0.5 mM Gln (Figure 1J).

Asct2 overexpression reprograms T-cell metabolism

Upon activation, T cells undergo a regulated process of proliferation and differentiation into effector and memory subsets, requiring increased biosynthetic and bioenergetic activities to support their function.13 Given the distinct functional characteristics of Asct2-overexpressing CD4+ OT-II and CD8+ OT-I T cells, we aimed to investigate potential variances in their metabolic profiles.

Metabolic Seahorse assay revealed that Asct2-overexpressing CD8+ OT-I T cells exhibited elevated basal OCR compared with control counterparts. Importantly, there was a marked increase in maximal respiratory capacity in Asct2-overexpressing CD8+ OT-I T cells (Asct2 CD8+ OT-I) following uncoupling of the mitochondrial membrane with FCCP (Figure 1K). Additionally, increased glycolytic function, as indicated by higher ECAR, was observed in Asct2 CD8+ OT-I T cells. Similar findings were observed in CD4+ OT-II T cells, in which Asct2 overexpression (Asct2 CD4+ OT-II) led to augmented OCR and ECAR capacities (Figure 1L), underscoring the role of Asct2 in reshaping the metabolic state of T cells.

Several studies show that central memory T cells have higher basal OCR and spare respiratory capacity than other T-cell types.14,15 Our analysis found no significant differences in memory phenotypes between Asct2-overexpressing CD4+/CD8+ T cells and controls (supplemental Figure 1A-D). Both OT-I and OT-II T cells mostly displayed an effector memory phenotype (CD62L–CD44+), which aligns with the strong activation via CD3/CD28 for retrovirus transduction.

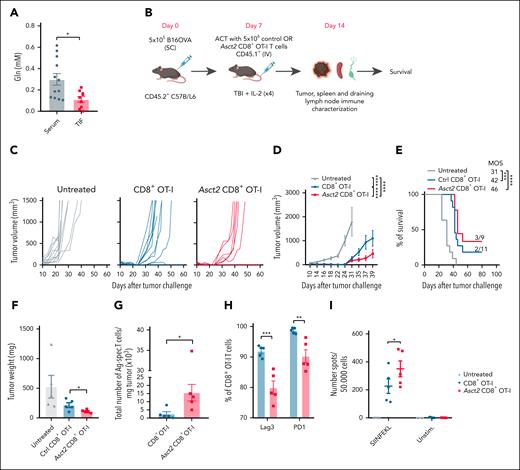

Asct2 overexpression in Ag-specific T cells enhances ACT immunotherapy

To assess the potential of Asct2 overexpression in enhancing ACT therapy, B16OVA tumor-bearing mice were treated with control or Asct2 CD8+ OT-I T cells. Melanoma heavily depends on Gln, using it as a crucial energy and carbon source, and as a primary driver of the tricarboxylic acid cycle.16 Significantly lower levels of Gln were detected in the tumor interstitial fluid of B16OVA tumors obtained 14 days after tumor injection (Figure 2A), underscoring their high Gln consumption and indicating a Gln-deficient TME.

Asct2 overexpression on OT-I T cells enhances the efficacy of ACT immunotherapy. (A) Gln concentration measured in the TIF and sera of B16OVA-challenged mice. (B) Experimental design to evaluate antitumor activity of ACT. (C-E) Tumor growth measured over time (C-D) and OS of mice (E) after treatment with Asct2-CD8+ OT-I or with Ctrl CD8+ OT-I T cells (n = 9-11 mice per group). (F) Tumor weight measured at day 14 after treatment. (G) Number of Ag-specific T cells infiltrating the tumor measured by flow cytometry using SIINFEKL tetramers. (H) Percentage of expression of LAG3 and PD-1 measured in CD45.1+ tumor-infiltrating CD8+ OT-I and Asct2–OT-I T cells measured by flow cytometry. (I) Number of IFN-γ–producing Ag-specific T cells measured in the spleen of untreated mice or treated with Ctrl CD8+ OT-I or Asct2–OT-I T cells in response to SIINFEKL peptide. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments. Data represent mean ± SEM and were analyzed using Student t test, 2-way ANOVA, and 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons test (∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗P < .01; ∗P < .05). MOS, median overall survival; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1; SC, subcutaneous; TIF, tumor interstitial fluid; unstim, unstimulated.

Asct2 overexpression on OT-I T cells enhances the efficacy of ACT immunotherapy. (A) Gln concentration measured in the TIF and sera of B16OVA-challenged mice. (B) Experimental design to evaluate antitumor activity of ACT. (C-E) Tumor growth measured over time (C-D) and OS of mice (E) after treatment with Asct2-CD8+ OT-I or with Ctrl CD8+ OT-I T cells (n = 9-11 mice per group). (F) Tumor weight measured at day 14 after treatment. (G) Number of Ag-specific T cells infiltrating the tumor measured by flow cytometry using SIINFEKL tetramers. (H) Percentage of expression of LAG3 and PD-1 measured in CD45.1+ tumor-infiltrating CD8+ OT-I and Asct2–OT-I T cells measured by flow cytometry. (I) Number of IFN-γ–producing Ag-specific T cells measured in the spleen of untreated mice or treated with Ctrl CD8+ OT-I or Asct2–OT-I T cells in response to SIINFEKL peptide. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments. Data represent mean ± SEM and were analyzed using Student t test, 2-way ANOVA, and 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons test (∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗P < .01; ∗P < .05). MOS, median overall survival; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1; SC, subcutaneous; TIF, tumor interstitial fluid; unstim, unstimulated.

Then, C57BL/6 mice were subcutaneously challenged with B16OVA cells and, 7 days later, treated with 5 × 106 control or Asct2 CD8+ OT-I T cells (Figure 2B). Mice treated with Asct2 CD8+ OT-I T cells exhibited a delay in tumor growth as evidenced by tumor weight and survival rate analysis (Figure 2C-E). Immune characterization of the tumors at day 14 after treatment revealed that mice treated with Asct2 CD8+ OT-I T cells had reduced tumor weight (Figure 2F), increased infiltration of antigen-specific transferred T cells (Figure 2G), and lower expression of exhaustion markers such as lymphocyte-activation gene 3 and programmed cell death protein 1 (Figure 2H), indicating a less exhausted phenotype in the tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Moreover, mice treated with Asct2 CD8+ OT-I T cells showed a higher number of IFN-γ–producing antigen-specific T cells in the spleen compared with control T cells (Figure 2I).

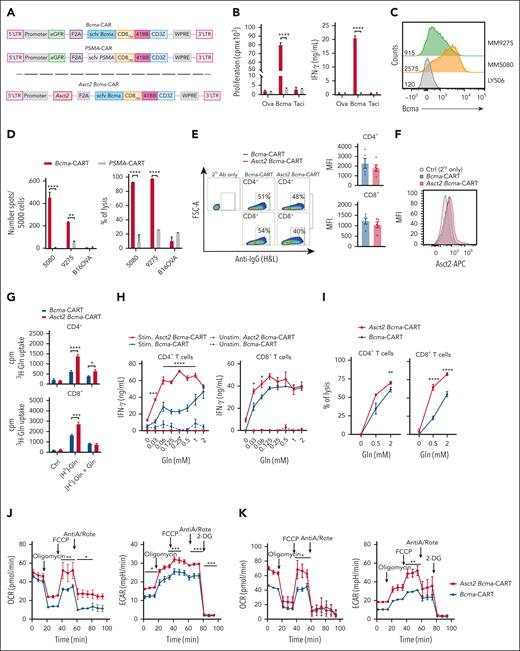

Asct2 overexpression in murine Bcma-CAR T cells improves their functionality in vitro

Gln “addiction” of MM8,17 may lead to Gln depletion in the bone marrow (BM), affecting the TME. Considering this Gln deprivation in the BM, we wondered if enhancing Asct2 expression could improve Gln uptake capacity and potentially benefit CAR T-cell immunotherapy in MM models.

Because MM expresses BCMA, we sought to generate a murine anti–Bcma-CAR T-cell therapy that was effective against MM in vivo. Then, we tested if Asct2 overexpression could improve their efficacy in vivo. A retrovirus construct encoding an antimurine Bcma single-chain variable fragment (derived from antibody 29C12-mut; supplemental Materials and methods) linked to the murine CD8 transmembrane, the 41BB costimulatory, and the CD3ζ domains in combination with the green fluorescent protein (GFP) was generated (Bcma-CAR). As control, we used an anti–prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) CAR encoded in the same vector as the Bcma-CAR (Figure 3A upper). Bcma-CAR cells exhibited robust proliferation and high IFN-γ secretion when stimulated with Bcma, but no activation occurred in response to ovalbumin or transmembrane activator and CAML interactor, whereas PSMA-CAR T cells did not respond to any protein (Figure 3B). Subsequent coculture experiments with Bcma-expressing MM cells confirmed that Bcma-CAR T cells selectively secreted IFN-γ, and displayed cytolytic activity against 5080 and 9275 MM cells expressing different levels of Bcma (Figure 3C-D).

Asct2 overexpression enhances Bcma-CAR T-cell activity. (A) Schematic representation of second-generation Bcma-CAR and PSMA-CAR constructs (upper). Schematic representation of second-generation of Asct2 Bcma-CAR construct (lower). (B) Proliferation and IFN-γ production of Bcma and PSMA-CAR T cells in response to Bcma-, Taci-, or ovalbumin-coated plates (as an irrelevant protein). (C) Bcma expression in MM cell lines 5080 and 9275 and Ctrl lymphoma cell line LY5026. (D) IFN-γ production and percentage of lysis induced by Bcma and PSMA-CAR T cells in response to these MM cell lines (5080 and 9275) or to B16OVA melanoma cells. (E) CAR expression in T lymphocytes transduced with retrovirus expressing Bcma or Asct2 BCMA-CAR constructs. Representative flow cytometry plots are shown together with histograms representing the mean fluorescence intensity in RV-transduced CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. (F) Asct2 expression measured by flow cytometry. (G) 3H-labeled Gln uptake by CD4+ and CD8+Bcma-CAR T cells and Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells (purified by flow cytometric cell sorting). (H) IFN-γ secretion of CD4+ or CD8+Bcma-CAR T cells and Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells in response to Bcma-coated plates under different Gln concentrations. (I) Specific lysis of 5080 MM cells by Bcma-CAR T cells and Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells under different Gln concentrations. (J-K) Seahorse metabolic assay was used to measure the OCR and the ECAR of Ctrl and Asct2-overexpressing CD4+ (J) and CD8+ (K) Bcma-CAR T cells. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. Data represent mean ± SEM, and were analyzed using 2-way ANOVA and 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons test (∗∗∗∗P < .0001; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗P < .01; ∗P < .05). Ab, antibody; AntiA/Rote, antimycin A/rotenone; APC, allophycocyanin; cpm, counts per minute; Ctrl, control; FSC-A, forward scatter area; H&L, heavy and light; IgG, immunoglobulin G; LTR, long terminal repeat; MFI, mean fluoresecence intensity; Ova, ovalbumin; SC, subcutaneous; stim, stimulated; Taci, transmembrane activator and CAML interactor; unstim, unstimulated.

Asct2 overexpression enhances Bcma-CAR T-cell activity. (A) Schematic representation of second-generation Bcma-CAR and PSMA-CAR constructs (upper). Schematic representation of second-generation of Asct2 Bcma-CAR construct (lower). (B) Proliferation and IFN-γ production of Bcma and PSMA-CAR T cells in response to Bcma-, Taci-, or ovalbumin-coated plates (as an irrelevant protein). (C) Bcma expression in MM cell lines 5080 and 9275 and Ctrl lymphoma cell line LY5026. (D) IFN-γ production and percentage of lysis induced by Bcma and PSMA-CAR T cells in response to these MM cell lines (5080 and 9275) or to B16OVA melanoma cells. (E) CAR expression in T lymphocytes transduced with retrovirus expressing Bcma or Asct2 BCMA-CAR constructs. Representative flow cytometry plots are shown together with histograms representing the mean fluorescence intensity in RV-transduced CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. (F) Asct2 expression measured by flow cytometry. (G) 3H-labeled Gln uptake by CD4+ and CD8+Bcma-CAR T cells and Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells (purified by flow cytometric cell sorting). (H) IFN-γ secretion of CD4+ or CD8+Bcma-CAR T cells and Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells in response to Bcma-coated plates under different Gln concentrations. (I) Specific lysis of 5080 MM cells by Bcma-CAR T cells and Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells under different Gln concentrations. (J-K) Seahorse metabolic assay was used to measure the OCR and the ECAR of Ctrl and Asct2-overexpressing CD4+ (J) and CD8+ (K) Bcma-CAR T cells. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. Data represent mean ± SEM, and were analyzed using 2-way ANOVA and 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons test (∗∗∗∗P < .0001; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗P < .01; ∗P < .05). Ab, antibody; AntiA/Rote, antimycin A/rotenone; APC, allophycocyanin; cpm, counts per minute; Ctrl, control; FSC-A, forward scatter area; H&L, heavy and light; IgG, immunoglobulin G; LTR, long terminal repeat; MFI, mean fluoresecence intensity; Ova, ovalbumin; SC, subcutaneous; stim, stimulated; Taci, transmembrane activator and CAML interactor; unstim, unstimulated.

To evaluate the potential enhancement of Bcma-CAR T-cell function through Asct2 overexpression, the GFP transduction marker in the CAR vector was replaced with the murine Asct2 sequence to generate T cells coexpressing the Bcma-CAR and Asct2 (Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells; Figure 3A lower). Flow cytometry analysis revealed similar expression levels of the CAR in both Bcma and Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells (Figure 3E), and also an overexpression of Asct2 in the membrane of Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells (Figure 3F), whereas 3H-Gln transport assays confirmed the improved Gln transport capacity in Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells (Figure 3G).

No major differences in the percentages of naïve, effector memory, and central memory phenotypes were observed between the 2 groups, with the exception of the central memory population in CD4+ T cells, which was notably higher in both groups expressing the Bcma-CAR. In CD8+ T cells, no differences in the memory phenotype were observed (supplemental Figure 2).

To assess their functional activity, CD4+ and CD8+ CAR T cells were activated on Bcma-coated plates, with varying Gln concentrations. Both CD4+ and CD8+Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells exhibited significantly higher IFN-γ secretion than Bcma-CAR T cells under conditions of low Gln availability. However, at higher Gln concentrations (2 mM), the IFN-γ secretion was comparable between the 2 groups, suggesting that Asct2 overexpression enhances T-cell functionality under restricted Gln conditions (Figure 3H; supplemental Figure 3A-C). Inhibition of the Asct2 transporter with V9302 significantly reduced the proliferation of murine CD8+Bcma-CAR T cells when stimulated with Bcma, at both optimal and suboptimal Gln levels (supplemental Figure 3D). Knockdown of Asct2 in these cells further confirmed the positive role of Gln uptake in T-cell stimulation (supplemental Figure 3E-G).

In assays evaluating the lytic activity of Bcma-CAR constructs, coculture of 5080 MM cells with CD4+ or CD8+Bcma-CAR T cells or Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells revealed a higher lytic capacity in Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells, particularly at low Gln levels (0.5 mM; Figure 3I).

Consistent with observations in OT-I and OT-II T cells, both CD4+ and CD8+Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells exhibited enhanced OCR and ECAR compared with Bcma-CAR T cells (Figure 3J-K, respectively). This advantage is maintained when glycolysis in inhibited with WZB117, but is lost when glutaminolysis is inhibited with BPTES (supplemental Figure 4). These results suggest improved metabolic fitness in activated T cells overexpressing Asct2, similar to previous findings in OT-I T cells.

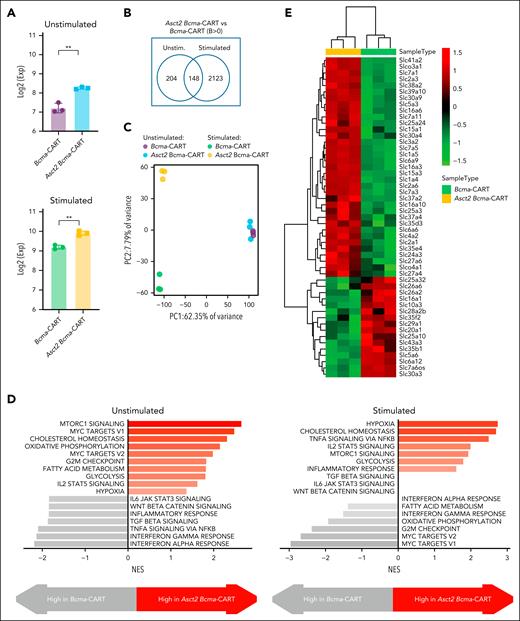

We compared the transcriptomic profiles of Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells and Bcma-CAR T cells before and after antigen stimulation. CD8+ CAR T cells were incubated with or without Bcma protein for 12 hours, followed by RNA-seq. Asct2 expression was higher in Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells and increased further upon Bcma activation in both cell types, peaking in Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells (Figure 4A). Initially, 352 genes were differentially expressed between the 2 cell types, increasing to 2271 after stimulation (Figure 4B). This highlights significant transcriptomic changes in Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells (Figure 4C), with increased mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) activity and pathways related to cholesterol homeostasis, hypoxia, and glycolysis (Figure 4D). Several studies demonstrate that Gln uptake via the Asct2 transporter is essential for mTORC1 activation,18 which is closely linked to the regulation of many solute carrier (SLC) transporters.19 Importantly, the repertoire of SLC transporters differed from conventional Bcma-CAR T cells (Figure 4E), indicating specific metabolic reprogramming due to Asct2 overexpression.

Transcriptomic analysis of Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells and Bcma-CAR T cells before and after BCMA antigen stimulation. (A) Expression of Slc1a5 (Asct2). (B) Number of differentially expressed genes between Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells and Bcma-CAR T cells before and after BCMA antigen stimulation. (C) PC analysis of gene expression profiles. (D) Gene signatures upregulated in Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells compared with Bcma-CAR T cells, before and after BCMA antigen stimulation. (E) Heat map showing differential expression of SLC family members in Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells compared with Bcma-CAR T cells after antigen stimulation. Data represent mean ± SEM, and were analyzed using Student t test (∗∗P < .01). Exp, expression; NES, normalized enriched score; PC, principal component; unstim, unstimulated.

Transcriptomic analysis of Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells and Bcma-CAR T cells before and after BCMA antigen stimulation. (A) Expression of Slc1a5 (Asct2). (B) Number of differentially expressed genes between Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells and Bcma-CAR T cells before and after BCMA antigen stimulation. (C) PC analysis of gene expression profiles. (D) Gene signatures upregulated in Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells compared with Bcma-CAR T cells, before and after BCMA antigen stimulation. (E) Heat map showing differential expression of SLC family members in Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells compared with Bcma-CAR T cells after antigen stimulation. Data represent mean ± SEM, and were analyzed using Student t test (∗∗P < .01). Exp, expression; NES, normalized enriched score; PC, principal component; unstim, unstimulated.

Asct2 overexpression enhances antitumor activity of Bcma-CAR T cells in syngeneic MM models

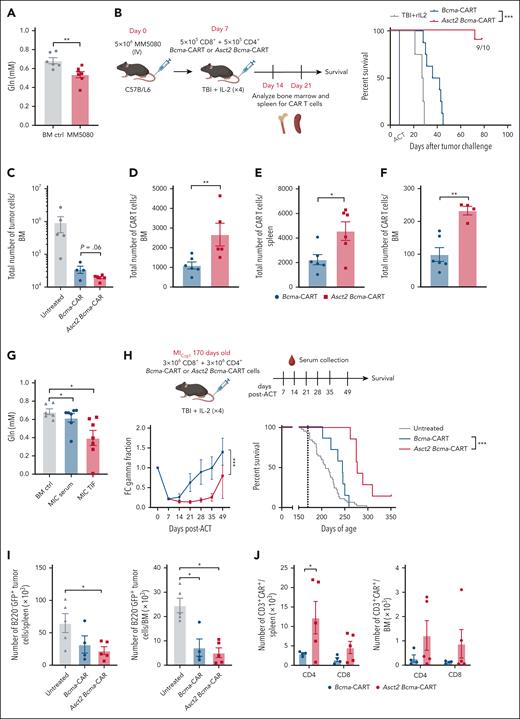

To evaluate if Asct2 overexpression could enhance ACT immunotherapy with Bcma-CAR T cells, we used a murine model of MM based on the injection of the MM-derived 5080 MM cell line. The 5080 MM cell line was previously established, genetically characterized and found to engraft into immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice.11 As occurred in the BM aspirates of patients with MM, Gln concentration in the interstitial fluid of BM from mice with 5080 tumors was significantly lower than that found in BM from control healthy mice (Figure 5A), suggesting that overexpressing Asct2 could offer a benefit by enhancing Gln uptake by transferred CAR T cells within the TME.

The antitumor efficacy of ACT immunotherapy with Bcma-CAR T cells was improved by Asct2 overexpression. (A) Gln concentration measured in the BM of healthy mice or mice challenged with 5080 MM cell line (25 days after tumor challenge). (B) Experimental design to evaluate antitumor activity of CAR T cells in a MM murine model based on the IV injection of 5080 MM cells and percent of survival of 5080 MM-challenged mice treated with 1 × 106 CAR T cells (1:1 ratio of CD4+ and CD8+ CAR T cells; number of mice per group n = 10). (C) Total number of tumor cells (B220+GFP+) found in the BM of mice treated with Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells and Bcma-CAR T cells. (D-F) Total numbers of CAR T cells measured in the BM (D, F), and the spleen (E) of mice treated with Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells or Bcma-CAR T cells at day 14 (D-E), and at day 21 (F) after CAR T-cell transfer. (G-J) Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells exert antitumor activity in a genetic model of MM. (G) Gln concentration in the BM aspirates and the sera of 170-day-old MICγt1 mice compared with the Gln levels in BM or serum of healthy mice. (H) Experimental design for testing CAR T-cell immunotherapy against the MICγt1 MM genetic model. Fc γ-globulin fraction levels and survival curves after CAR T-cell treatment (n = 7 mice per group; survival data for untreated animals corresponds to a cohort of 50 mice). (I) Number of tumor cells in both the spleen and the BM of mice treated with Bcma-CAR T cells and Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells compared with untreated mice. (J) CAR T cells in the spleen and in the BM of MICγt1 mice treated with Bcma or Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells analyzed in the CD4+ and CD8+ compartments. Data are representative of 2 to 3 independent experiments. Data represent mean ± SEM and were analyzed using Student t test, 2-way ANOVA, and 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons test. Statistical analysis for survival curves is a log-rank test (∗∗P < .01; ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗P < .001). ACT, adoptive cell therapy; FC, fold change; rIL, recombinant interleukin.

The antitumor efficacy of ACT immunotherapy with Bcma-CAR T cells was improved by Asct2 overexpression. (A) Gln concentration measured in the BM of healthy mice or mice challenged with 5080 MM cell line (25 days after tumor challenge). (B) Experimental design to evaluate antitumor activity of CAR T cells in a MM murine model based on the IV injection of 5080 MM cells and percent of survival of 5080 MM-challenged mice treated with 1 × 106 CAR T cells (1:1 ratio of CD4+ and CD8+ CAR T cells; number of mice per group n = 10). (C) Total number of tumor cells (B220+GFP+) found in the BM of mice treated with Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells and Bcma-CAR T cells. (D-F) Total numbers of CAR T cells measured in the BM (D, F), and the spleen (E) of mice treated with Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells or Bcma-CAR T cells at day 14 (D-E), and at day 21 (F) after CAR T-cell transfer. (G-J) Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells exert antitumor activity in a genetic model of MM. (G) Gln concentration in the BM aspirates and the sera of 170-day-old MICγt1 mice compared with the Gln levels in BM or serum of healthy mice. (H) Experimental design for testing CAR T-cell immunotherapy against the MICγt1 MM genetic model. Fc γ-globulin fraction levels and survival curves after CAR T-cell treatment (n = 7 mice per group; survival data for untreated animals corresponds to a cohort of 50 mice). (I) Number of tumor cells in both the spleen and the BM of mice treated with Bcma-CAR T cells and Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells compared with untreated mice. (J) CAR T cells in the spleen and in the BM of MICγt1 mice treated with Bcma or Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells analyzed in the CD4+ and CD8+ compartments. Data are representative of 2 to 3 independent experiments. Data represent mean ± SEM and were analyzed using Student t test, 2-way ANOVA, and 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons test. Statistical analysis for survival curves is a log-rank test (∗∗P < .01; ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗P < .001). ACT, adoptive cell therapy; FC, fold change; rIL, recombinant interleukin.

In this 5080 MM model, we observed that administering Bcma-CAR T cells 7 days after IV injection of 5080 MM cells resulted in a dose-dependent therapeutic effect. Specifically, whereas the administration of 3 × 106Bcma-CAR T cells (CD4:CD8 ratio, 1:1) provided protection for 80% of the mice, this response dropped to 0% when administering 1 × 106Bcma-CAR T cells (supplemental Figure 5). Therefore, we used this latter setting for comparative studies. Mice were challenged with 5080 MM cells and treated IV with 1 × 106 CD8+ and CD4+Bcma-CAR T cells (1:1 ratio) or Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells. Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells significantly improved overall survival (OS) in mice challenged with 5080 tumors, achieving 90% survival at day 100 after treatment, whereas no cures were observed with Bcma-CAR T cells alone (Figure 5B).

Seven days after infusion, CAR T cells isolated from the BM of mice treated with Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells showed higher numbers of IL-2 and IFN-γ–producing cells in response to stimulation, similar to that found in preinfusion cell products (supplemental Figure 6). Fourteen days after CAR T-cell transfer, there was a significant reduction in tumor cells in the BM of both CAR T-cell–treated mice groups, being more significant in the BM of mice treated with Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells compared with those treated with Bcma-CAR T cells (Figure 5C). Moreover, there was a higher number of infiltrating CAR T cells in both the spleen and BM of mice receiving Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells (Figure 5D-E). These differences were also observed at day 21 after CAR T-cell transfer (Figure 5F), suggesting that the augmented persistence of CAR T cells in the BM through Asct2 overexpression enhances the antitumor immunity of CAR T cells in the 5080 MM model.

We investigated whether therapy efficacy was linked to changes in the TME in the BM or spleen, but we found no significant differences in leukocyte subpopulations (supplemental Figure 7). To further explore the role of Gln in CAR T-cell functionality, we overexpressed L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT-1; Slc7a5) instead of Asct2 in Bcma-CAR T cells. LAT-1 exchanges essential amino acids with intracellular Gln. This modification impaired Bcma-CAR T-cell function and reduced the survival of treated mice, indicating the importance of Gln retention for antitumor effectiveness (supplemental Figure 8).

Asct2 overexpression increases therapeutic responses of Bcma-CAR T cells in genetically engineered mouse models of MM

We evaluated the antitumor effect of the Bcma-CAR T cells in a genetic MM preclinical model based on the generation of transgenic mice carrying the MM genetic drivers MYC and IKK2NF-κB. This model closely mimics common genetic alterations observed in human MM, presenting BM tumors comprising >10% GFP+CD138+B220−sIgM− plasma cells that morphologically resemble human MM cells. The BM infiltration pattern, expression of typical MM markers (such as acid phosphatase, Bcma, Slamf7, and Taci), immunoglobulin secretion, clonal immunoglobulin heavy chain variable gene rearrangements, and other hallmark MM features were also observed in this model.11 In this MIcγ1 strain mice, survival is significantly compromised, with most mice succumbing ∼200 days after birth. Notably, a decrease in Gln concentration was observed in BM aspirates of 170-day-old MIcγ1 mice compared with levels in BM or serum of healthy animals (Figure 5G).

To investigate if MM progression could be delayed by Bcma-CAR T-cell immunotherapy in MIcγ1 mice, 6 × 106Bcma-CAR T cells and Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells (3 × 106 CD4+ and 3 × 106 CD8+ CAR T cells for each group) were IV administered at day 170 after birth. Analysis of the γ-globulin fraction in diseased mice at different time points revealed a transient reduction in mice receiving Bcma-CAR T cells, notably deeper and sustained after treatment with Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells (Figure 5H; P < .005). Importantly, treatment with Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells significantly enhanced OS compared with conventional Bcma-CAR T cells, with median survival times of 208 days for untreated, 245 days for Bcma-CAR T cells, and 275 days for Asct2 Bcma-CAR T-cell–treated mice (Figure 5H; log-rank test P < .005).

Concurrently, we conducted an experiment to characterize the CAR T-cell product 14 days after their administration. Initially, we observed a decrease in the total number of tumor cells in both the spleen and the BM of mice treated with Bcma-CAR T cells compared with untreated mice (Figure 5I). Notably, mice treated with Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells exhibited a higher number of CAR T cells in the spleen and in the BM, indicating a longer persistence of Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells (supplemental Figure 9A-B). These differences were observed in both CD4+ and CD8+ CAR T cells (Figure 5J).

Asct2 Bcma-CAR T-cell therapy is less effective in the genetic model compared with the 5080 MM cell transfer model. This may be due to higher levels of tumor cells in the MIcγ1 mice, as seen in both the BM and spleen (supplemental Figure 10A-B). Though the tumor niche showed no major differences, the 5080 MM model had more B cells and F4-80+ cells in the BM, and more B cells and CD4+ cells in the spleen (supplemental Figure 10C-D).

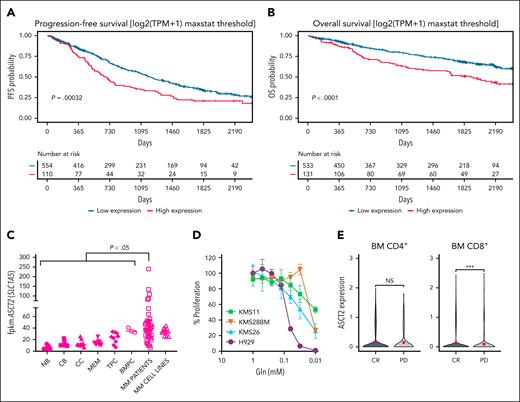

ASCT2 expression is associated with a poor prognosis in MM

We studied if ASCT2 expression could serve as a prognostic indicator for MM. Leveraging RNA-seq data from the CoMMpass (IA18) study involving 664 samples from patients with MM, we analyzed the progression-free survival (PFS) and OS of patients with MM according to the level of expression of ASCT2, separating patients into 2 groups based on the distribution of expression levels. Patients with high and low expression of ASCT2 were defined using the maxstat threshold, a computationally determined cutoff that objectively identifies the point at which the 2 groups are most distinctly separated. High ASCT2 expression was significantly associated with reduced PFS (Figure 6A) and OS in patients with MM (Figure 6B). Analysis of RNA-seq samples from BM aspirates of untreated patients with MM compared ASCT2 expression levels in various B-cell subtypes (naïve, centroblasts, centrocytes, memory, tonsillar, and BM plasma cells) obtained from healthy donors as previously described,13 showed a marked upregulation in MM cells compared with normal B-cell subsets (Figure 6C). These findings suggest a potential prognostic relevance of ASCT2 expression in MM. We assessed the dependency of 4 human MM cell lines on Gln deprivation in culture. Although the cell lines exhibited varying degrees of dependency, all demonstrated a significant reduction in cell proliferation when Gln was absent (Figure 6D). We conducted an analysis of the recently published single-cell RNA-seq data (GSE234261) by Rade et al20 on BM T cells from patients with MM, 30 days after BCMA-CAR T-cell transfer. The results revealed an elevated ASCT2-expression in CD8+ T cells from patients who experienced a complete response compared with those who did not respond to therapy (progressive disease; Figure 6E). More extensive experiments will be necessary to validate this trend.

ASCT2 expression is associated with a poor prognosis in MM. Correlation between ASCT2 expression and clinical outcomes in MM in PFS (A) and OS (B). (C) ASCT2 messenger RNA expression levels in NBs, CBs, CCs, MEMs, TPCs, and BMPCs, as well as in MM aspirates and MM cell lines. (D) Proliferation of human MM cell lines in culture medium with decreasing concentrations of Gln. Percentage of proliferation with respect to that found in culture medium supplemented with Gln at 2 mM. (E) ASCT2 expression in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in patients who experienced a CR compared with those who did not respond to therapy. Data represent mean ± SEM and were analyzed using 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons test (∗P < .05; ∗∗∗P < .001). BMPC, BM plasma cell; CB, centroblast; CCs, centrocytes; CR, complete response; MEM, memory B cells; NB, naïve B cells; NS, no significance; PD, progressive disease; TPC, tonsillar plasma cell; TPM, transcripts per million.

ASCT2 expression is associated with a poor prognosis in MM. Correlation between ASCT2 expression and clinical outcomes in MM in PFS (A) and OS (B). (C) ASCT2 messenger RNA expression levels in NBs, CBs, CCs, MEMs, TPCs, and BMPCs, as well as in MM aspirates and MM cell lines. (D) Proliferation of human MM cell lines in culture medium with decreasing concentrations of Gln. Percentage of proliferation with respect to that found in culture medium supplemented with Gln at 2 mM. (E) ASCT2 expression in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in patients who experienced a CR compared with those who did not respond to therapy. Data represent mean ± SEM and were analyzed using 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons test (∗P < .05; ∗∗∗P < .001). BMPC, BM plasma cell; CB, centroblast; CCs, centrocytes; CR, complete response; MEM, memory B cells; NB, naïve B cells; NS, no significance; PD, progressive disease; TPC, tonsillar plasma cell; TPM, transcripts per million.

To explore the clinical relevance of ASCT2 overexpression in human CAR T cells, we created 2 lentiviral constructs encoding an antihuman BCMA-CAR using single-chain variable fragment from the C11D5.3 clone, used in the US Food and Drug Administration–approved idecabtagene vicleucel for MM. We prepared a conventional BCMA-CAR fused to blue fluorescent protein and the ASCT2 BCMA-CAR construct coexpressing ASCT2 (Figure 7A). Both were expressed at similar levels in CAR T cells (Figure 7B). Flow cytometry confirmed ASCT2 overexpression in ASCT2 BCMA-CAR T cells (Figure 7C). Notably, these cells showed greater proliferation and higher IFN-γ production upon BCMA stimulation at various Gln concentrations (Figure 7D). Additionally, they had a higher proportion of naïve stem cell memory and central memory subsets (Figure 7E).

ASCT2 overexpression enhances antihuman BCMA-CAR T-cell activity. (A) Schematic diagrams of lentiviral vectors used to overexpress ASCT2 in human BCMA-CAR T cells. (B) Expression levels of the CAR construct, measured by BFP fluorescence. (C) Human ASCT2 expression detected on CAR T cells by flow cytometry. (D) Proliferation of CAR T cells in response to BCMA-coated plate stimulation at different Gln concentrations, measured by [3H]-thymidine incorporation. (E) Phenotypic analysis of CD4+ and CD8+ CAR T cells at the time of manufacture. (F) Asct2 silencing in H929 MM cells using 3 different single-guide RNAs (TadCBEd). (G) Measurement of [3H]-Gln uptake in WT and ASCT2-silenced H929 MM cells. (H) Cytotoxic activity of BCMA-CAR T cells against WT and ASCT2-silenced H929 MM cells. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments. Data represent mean ± SEM and were analyzed using 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons test (∗∗∗P < .001). BFP, blue fluorescent protein; cpm, counts per million; KO, knockout; neg, negative; SSC-A, side scatter area; TCM, T central memory; TEM, T effector memory; TEMRA, T effector memory recently reactivated; TSCM, T stem cell memory; WT, wild-type.

ASCT2 overexpression enhances antihuman BCMA-CAR T-cell activity. (A) Schematic diagrams of lentiviral vectors used to overexpress ASCT2 in human BCMA-CAR T cells. (B) Expression levels of the CAR construct, measured by BFP fluorescence. (C) Human ASCT2 expression detected on CAR T cells by flow cytometry. (D) Proliferation of CAR T cells in response to BCMA-coated plate stimulation at different Gln concentrations, measured by [3H]-thymidine incorporation. (E) Phenotypic analysis of CD4+ and CD8+ CAR T cells at the time of manufacture. (F) Asct2 silencing in H929 MM cells using 3 different single-guide RNAs (TadCBEd). (G) Measurement of [3H]-Gln uptake in WT and ASCT2-silenced H929 MM cells. (H) Cytotoxic activity of BCMA-CAR T cells against WT and ASCT2-silenced H929 MM cells. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments. Data represent mean ± SEM and were analyzed using 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons test (∗∗∗P < .001). BFP, blue fluorescent protein; cpm, counts per million; KO, knockout; neg, negative; SSC-A, side scatter area; TCM, T central memory; TEM, T effector memory; TEMRA, T effector memory recently reactivated; TSCM, T stem cell memory; WT, wild-type.

To further demonstrate the importance of ASCT2, we performed cytotoxicity assays with BCMA-CAR T cells against tumor cells with different ASCT2 levels. We silenced ASCT2 in H929 MM cells using 3 single-guide RNAs, with guide 1 being more effective (Figure 7F). Tritiated Gln uptake assays confirmed reduced uptake in ASCT2 knockout cells (Figure 7G). BCMA-CAR T cells more efficiently lysed ASCT2 knockout H929 cells, likely due to increased amino acid availability (Figure 7H).

Discussion

MM tumor cells exhibit a reliance on extracellular Gln, displaying characteristics of Gln addiction.8 In this context, Gln levels in the BM of patients with MM can drop significantly, from ∼600 μM in patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and smoldering multiple myeloma (the precursor stages of the MM disease) to <400 μM in patients with MM.8 In the vicinity of tumor cells that overexpress Gln transporters, Gln levels may even fall to between 100 and 200 μM.21 We found that T-cell proliferation, IFN-γ production, or even the lytic activity are compromised when Gln levels are <500 μM. Given this insight, modifying T cells to overexpress Asct2, the primary Gln transporter, could enhance Gln uptake efficiency in a nutrient-deprived TME.

We found that Asct2 overexpression in T cells increased Gln uptake and enhanced function in response to T-cell receptor stimulation even at low Gln concentrations. Metabolically, Asct2-overexpressing T cells showed a higher OCR and ECAR compared with control T cells. This enhancement of T-cell functionality induced by Asct2 overexpression can be particularly relevant in Gln-deprived conditions often seen in “Gln-addicted” tumors such as MM. Clinical trials evaluating BCMA-CAR T-cell therapy in patients with MM have shown initial improvement in survival (www.ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT03361748, NCT03548207, and NCT03145181), but long-term persistence of the CAR T cells diminish, leading to decreased PFS (KarMMa, NCT03361748). The reduced CAR T-cell persistence might be linked to the high Gln consumption by MM cells and amino acid deprivation in the BM. Analysis of RNA-seq data from the CoMMpass study, including 664 samples from patients with MM acquired at diagnosis, identified a correlation between high ASCT2 expression and poorer PFS in patients with MM.

To investigate if Asct2 overexpression could enhance CAR T-cell therapy in MM, a murine version of Bcma-CAR T cells targeting murine Bcma was tested in vitro and in immunocompetent mice challenged with the MM cell line 5080. RNA-seq analyses and in vitro results suggest that Asct2 overexpression induces a specific metabolic reprogramming, likely through mTORC1 activation and the modulation of multiple SLC transporters. This integrates nutrient sensing with cellular growth and metabolic adaptation. Consequently, Asct2 overexpression may drive additional downstream changes that influence CAR T-cell phenotypes beyond simply enhancing Gln uptake. In vivo experiments with Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells and control Bcma-CAR T cells in the 5080 MM model showed promising results, with significant improvement in OS in mice treated with Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells and enhancing antitumor immunity. Furthermore, the Asct2 Bcma-CAR T cells were able to extend survival in transgenic mice carrying MM driver mutations MYC and IKK2NF-κB, which mimic common changes observed in human MM. This improvement was associated with enhanced CAR T-cell persistence and expansion, along with a metabolic profile showing increased basal OCR and ECAR. These findings are of particular significance given that they were obtained in immunocompetent murine models. In contrast to immunodeficient models such as NSG mice, immunocompetent hosts provide a TME that more accurately recapitulates the immune interactions and conditions present in the disease setting. However, despite significant advancements, complete cures were not achieved in this challenging MM model with low numbers of injected CAR T cells. These results highlight the need to explore new combinations to equip CAR T cells with tools to combat the immunosuppressive TME in patients with MM. In prior work, we found that antitumor T-cell activity in a poorly perfused, acidic TME can be enhanced by modulating transporters that regulate intracellular pH in T cells.22 Recently, it has also been shown that enforced expression of the glucose transporter GLUT1 enhances the antitumor efficacy of CAR T cells against CD19 or IL13Ra,23 or against glypican-3.24 Fine-tuning CAR T cells with a combination of these transporters, including ASCT2, might further enhance their ability to adapt to the TME and exert better antitumor actions.

In summary, our in vitro studies show that Asct2 overexpression in T cells and CAR T cells enhances their function and metabolism. Promising in vivo results using B16OVA melanoma and 5080 MM tumor models reveal improved antitumor immunity and increased OS. Further combinations can be explored to enhance the effects of Asct2 and develop synergistic strategies to combat Gln deprivation in the TME, giving T cells a competitive advantage in tumor rejection.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Elena Ciordia and Eneko Elizalde for the excellent animal care, Elisabet Guruceaga for their support in RNA-sequencing analyses, Diego Aligniani and Aitziber Lopez (Cytometry Unit) for their support in flow cytometry, and the Blood Bank of Navarra (Biobanco, Instituto de Investigaciones Sanitarias de Navarra, Pamplona, Spain) for their collaboration.

The study was supported by grants from Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (PID2022-137265OB-I00, PID2022-137914OB-I00 financiados por MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 y por la Unión Europea Next Generation EU/ PRTR, PID2021-128283OA-I00, PID2019-108989RB-I00, PLEC2021-008094 MCIN/AEI/10.13039/ 501100011033, AUTOCART, RTC-2017-6585-1), from Gobierno de Navarra Industria (0011-1411-2019-000079 and 0011-1411-2019-000072 [Proyecto SOCRATHeS]; 0011-1411-2020-000011 and 0011-1411-2020-000010 [Proyecto AGATA]; and 0011-1411-2023-000105 and 0011-1411-2023-000074 [Proyecto DIAMANTE]); from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, cofinanced by European Regional Development Fund, “A way to make Europe,” Red de Terapias Avanzadas TERAV (RD21/0017/0009); from the Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Cáncer (CB16/12/00489); from the European Union (T2EVOLVE, IMI H2020-JTI-IMI2-2019-18 Contract 945393 and CARAMBA, SC1-PM-08-2017. Contract 754658), and the Paula and Rodger Riney Foundation; the Cancer Research UK (C355/A26819), Fundación Científica Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer; Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro under the Accelerator Award Program; and Caja Rural de Navarra.

Authorship

Contribution: F.N., T.L., and J.J.L. conceptualized of the study; F.N., A.F.G., I.S.-M., P.J., B.P., M.M.-T., R.M.-T., M.L., N.C., C.M.-O., M.G., E.W.M., M.C., D.L., E.S., P.L.B., M.E.C.-C., P.S.M.-U., X.A., L.J., S.H.-S., J.R.R.-M., F.P., J.A.M.-C., T.L., and J.J.L. contributed to methodology; F.N., M.L., C.M.-O., M.E.C.-C., J.R.R.-M., F.P., J.A.M.-C., T.L., and J.J.L. contributed to investigation; F.N. and J.J.L. wrote the original draft of the manuscript; J.J.L., F.P., and T.L. acquired funding; F.N., T.L., and J.J.L. provided supervision; and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: F.N., T.L., J.A.M.-C., J.R.R.-M., M.L., F.P., and J.J.L. have a patent pending for the use of ASCT2 BCMA-CAR T cells. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Juan José Lasarte and Flor Navarro, Inmunología e Inmunoterapia, Centro de Investigación Médica Aplicada, Avda Pio XII, 55, 31008 Pamplona, Spain; email: fenavarro22@gmail.com/ jjlasarte@unav.es.

References

Author notes

F.N. and T.L. contributed equally to this study.

RNA-sequencing data are available in Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE299766).

Original data and detailed step-by-step methods are available on request from the corresponding author, Juan José Lasarte (jjlasarte@unav.es).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

![ASCT2 overexpression enhances antihuman BCMA-CAR T-cell activity. (A) Schematic diagrams of lentiviral vectors used to overexpress ASCT2 in human BCMA-CAR T cells. (B) Expression levels of the CAR construct, measured by BFP fluorescence. (C) Human ASCT2 expression detected on CAR T cells by flow cytometry. (D) Proliferation of CAR T cells in response to BCMA-coated plate stimulation at different Gln concentrations, measured by [3H]-thymidine incorporation. (E) Phenotypic analysis of CD4+ and CD8+ CAR T cells at the time of manufacture. (F) Asct2 silencing in H929 MM cells using 3 different single-guide RNAs (TadCBEd). (G) Measurement of [3H]-Gln uptake in WT and ASCT2-silenced H929 MM cells. (H) Cytotoxic activity of BCMA-CAR T cells against WT and ASCT2-silenced H929 MM cells. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments. Data represent mean ± SEM and were analyzed using 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons test (∗∗∗P < .001). BFP, blue fluorescent protein; cpm, counts per million; KO, knockout; neg, negative; SSC-A, side scatter area; TCM, T central memory; TEM, T effector memory; TEMRA, T effector memory recently reactivated; TSCM, T stem cell memory; WT, wild-type.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/146/24/10.1182_blood.2024027496/2/m_blood_bld-2024-027496-gr7.jpeg?Expires=1768572954&Signature=MKaK1iQstOrvrxQXxLIKV7RHgZyGBa2qNdvxV80fQ5nMqgDMCIucz6LW2PltqMAteXUXsr2gNvgQvybbcfXWwCx7LsdF9yD9~5fhvgBmwOXa-cGIxA5H4rsA3vJ-vChCf~9264lWxnIgEXNNeF6WQ476qnT5hNzdwKhz9l8SmD2H4Omfdxnq9TU9AqELOUPXivngEAVpEj51hui~pg25Wgm-f7k2omKPsQrUS5wvHm1o6mKuN1mqZbZNw8Kmqzm-iO72wDoTfLFkYP0Rtv0S-Hk7A55CrY1VQ15ZGNfwptmrE4iN6G8sgGp-r3CbQbbmJYCvSmOhZMjrg7j~g1~vAg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)