Abstract

The coronavirus infectious disease (COVID-19) shows a remarkable symptomatic heterogeneity. Several risk factors including advanced age, previous illnesses, and a compromised immune system contribute to an unfavorable outcome. In patients with hematologic malignancy, the immune response to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is significantly reduced explaining why the mortality rate of hematologic patients hospitalized for a SARS-CoV-2 infection is about 34%. Active immunization is an essential pillar to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infections in patients with hematologic malignancy. However, the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines may be significantly impaired, as only half of patients with hematologic malignancy develop a measurable antiviral antibody response. The subtype of hematologic malignancy and B cell–depleting treatment predict a poor immune response to vaccination. Recently, antiviral drugs and monoclonal antibodies for pre-exposure or postexposure prophylaxis and for early treatment of COVID-19 have become available. These therapies should be offered to patients at high risk for severe COVID-19 and vaccine nonresponders. Importantly, as the virus evolves, some therapies may lose their clinical efficacy against new variants. Therefore, the ongoing pandemic will remain a major challenge for patients with hematologic malignancy and their caregivers who need to constantly monitor the scientific progress in this area.

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was identified as the causative agent of the coronavirus infectious disease (COVID-19) in early 2020. Since December 2020, variants of concerns with increased transmissibility or with an escape to prior immunization have been reported.1-5 Since November 2021, variant B.1.1.529 (Omicron) was discovered in Botswana. This variant of concern encodes the largest number of genomic mutations reported thus far, including 32 mutations in the spike protein alone.6

It has become apparent that the clinical course of COVID-19 is more severe in patients with hematologic malignancy (HM). Therefore, we wished to summarize the current knowledge on COVID-19 in these diseases and performed a systematic literature search using the terms “hematologic malignancy,” “immunosuppressive,” and “COVID-19.”

COVID-19 in patients with hematologic malignancy

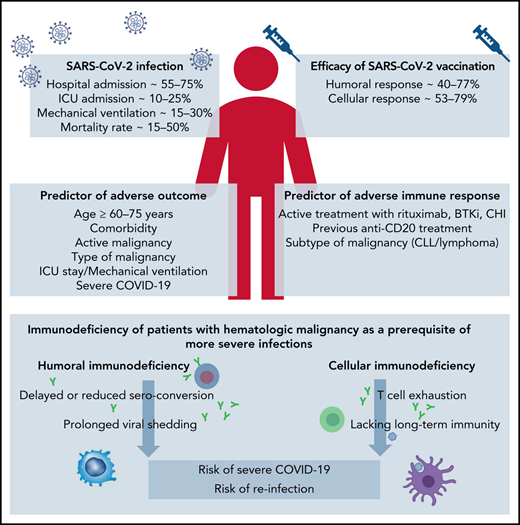

In light of the complex and profound immune dysfunction of patients with HM, already the first reports from Wuhan, China, demonstrated a more severe course of COVID-19 and a higher case fatality rate for patients with HM.7 Although hospitalized patients with HM had a similar case rate of COVID-19 compared with normal health care providers (10% and 7%), the case fatality rate was significant higher, with 62% for patients with HM compared with 0%, respectively. Thereafter, cohort studies and surveys from Europe, North America, South America, and Asia evaluated larger case series of patients with HM with COVID-19 and searched for risk factors associated with an adverse outcome (Table 1). Summarizing all studies reporting on more than 50 patients with HM with COVID-19, the overall hospitalization rate ranged from 56.4% to 73.8%, the intensive care unit (ICU) admission rate was 9.8% to 24.1%, mechanical ventilation was applied to 13.8% to 29.2%, and 14.1% to 51.5% of all patients died.8-42

Among the most common risk factors for an adverse outcome were, in the order of their frequency, age, comorbidities, active HM, type of HM, ICU stay, mechanical ventilation, and severe COVID-19.8,11-16,20,22,26,29,30,37,39,42 In a pooled meta-analysis, the estimated risk of death was 34% (95% confidence interval [CI], 28-39; N = 3240) in patients with HM with COVID-19.

The analysis of individual patient trajectories demonstrated shifting age and sex profiles of hospitalized patients and large-scale fluctuations in patient mortality with the ongoing progression of the pandemic.43 The results suggest that in HM patient vaccination, more frequent testing with identification of less-symptomatic patients and usage of COVID-19–directed interventions may have improved outcome.44

The SARS-CoV-2 viral load as assessed by cycle threshold (CT) values from reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays is significantly higher in patients with HM (CT = 25.0) than in patients without HM (CT = 29.2; P = .0039). This seems to apply particularly to those who had received chemotherapy or targeted therapies.45 In a retrospective observational study of patients with HM, median time to RT-PCR negativity for SARS-CoV-2 was 17 days (range, 7-49 days).26 Several case reports of immunocompromised patients indicate that prolonged viral shedding may lead to genomic evolution of the virus with emergence of new variants.46-48

Following SARS-CoV-2 infection, Abdul-Jawad et al49 demonstrated that patients with HM had delayed or negligible seroconversion, prolonged shedding, and sustained immune dysregulation compared with patients with solid cancer. RNA persistence (as detected by nasopharyngeal swab tests) beyond 20 days was seen in 60% of patients with HM compared with only 35% of patients with solid cancer. Thus, although patients with solid cancer, including those with advanced disease, do not seem at higher risk of SARS-CoV-2–associated immune dysregulation compared with the general population, patients with HM show complex immunologic consequences of SARS-CoV-2 exposure.

An immunologic characterization with systematic quantification of different cell types corresponding to patients with COVID-19 showed significantly decreased percentages of classical monocytes, immune-regulatory natural killer cells, double-positive T cells, and B cells for patients with HM compared with patients with COVID-19 without HM.50,51 These data emphasize the significant alterations in the relative distribution of specific innate and adaptive cell types in patients with HM, possibly compromising an initial response to COVID-19.

A prospective study monitored the kinetic of immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in 45 patients with HM. Antibody levels (Ab) to the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (N) and spike (S) protein were measured at +1, +3, and +6 months after nasal swabs became PCR negative.52 Mean anti-N and anti-S Ab levels were similar between patients with HM and controls and shared the same behavior, with anti-N Ab levels declining at +6 months and anti-S Ab levels remaining stable. However, seroconversion rates both for anti-N and anti-S Abs and at all time points were significant lower in patients with HM than in controls. All rituximab-pretreated patients failed to produce anti-N and anti-S Abs.

A small case series of 25 patients with HM confirmed the short lasting protection with declination of antibody titers from 4 months after COVID-19.53

The Hematology Alliance on COVID‐19 (ITA-HEMA-COV) project (NCT04352556) investigated patterns of seroconversion in a large case series of 237 SARS-CoV-2–infected patients with HM.54 Overall, 69% of patients had detectable immunoglobulin G (IgG) SARS-CoV-2 serum antibodies. In a multivariable logistic regression analysis, chemoimmunotherapy (odds ratio, 3·42; 95% CI, 1·04-11·21; P = .04] was associated with a lower rate of seroconversion, indicating that treatment-mediated immune dysfunction represents a main driver of impaired immunogenicity. Smaller case series confirmed the impaired immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with HM and reported a range of seroconversion of 16.6% to 84%.53,55

Evaluating cellular immune response, Bilich et al56 demonstrated impaired preexisting and newly generated CD4 T-cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with HM. In this study, patients with HM presented with reduced prevalence of preexisting SARS-CoV-2 cross-reactive CD4+ T-cell responses and signs of T-cell exhaustion compared with patients with solid cancer or healthy volunteers. The intensity, expandability, and diversity of SARS-CoV-2 T-cell responses were profoundly reduced and a potential determinant for a dismal outcome of COVID-19 in patients with HM.

Lacking T-cell immunity even in the setting of humoral response was demonstrated in the prospective monocentric study of specific viral immune responses induced by SARS-CoV-2 (COV-CREM) evaluating 39 SARS-CoV-2–infected patients with cancer, including 11 patients with HM.57 Only 36.4% of patients with HM exhibited T-cell responses against at least 1 of the SARS-CoV-2 proteins (S, M, or N). Of note, 2 patients without peripheral SARS-CoV-2–specific T cells had prolonged virus RNA detection after symptom resolution. The lack of T cell responses suggests that patients with HM fail to mount a protective T cell response. Therefore, a specific immunoglobulin monitoring alone may not be sufficient to characterize anti–SARS-CoV-2 immunity.

Higher rates of SARS-CoV-2–specific T cells (77%) were reported in an observational study of 100 patients with HM who were hospitalized for COVID-19. Flow cytometric and serologic analyses demonstrated that their B-cell response was impaired, and levels of SARS-CoV-2–specific antibodies were reduced compared with patients with solid cancer.58 Higher numbers of CD8 T cells correlated with an improved survival, including patients treated with anti-CD20 antibodies.

Vaccination

In 2020, several effective vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 have become available.59-62 More than 4 billion persons have been vaccinated since then. There is a clear consensus that these vaccinations are helpful to prevent hospitalizations and deaths after SARS-CoV-2 infections for all variants known to date.63

COVID-19 vaccination is particularly recommended in immunocompromised patients. However, there is only limited information on vaccine safety and efficacy for patients with HM, as most trials (eg, the registrational trials for mRNA-1273 [Moderna COVID-19 vaccine] and ChAdOx1 nCoV-19/AZD1222 [University of Oxford, AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine] have excluded patients with cancer).60,61 The phase 3 trial of BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine) and of Ad26.COV2.S (Janssen/Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine) enrolled only 4% and 0.5% of patients with cancer, respectively.59,62

It is important to note that many anticancer therapies are immunosuppressive. In particular, anti-CD20 antibodies may result in a prolonged depletion of normal B cells. This inevitably impairs the humoral response, and patients may fail to respond not only to influenza vaccines but also to other common vaccines.64

Patients with HM display the most pronounced impairment of SARS-CoV-2 cross-reactive CD4 T cells in parallel with highest expression of programmed cell death protein 1 on CD4 T cells.56 As opposed to anti-CD20 antibody treatment, programmed cell death protein 1 blockade (immune checkpoint treatment) may therefore enhance vaccination response.

That treatment modality may impact the vaccination response was shown by an evaluation of seroconversion rates against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein after US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved COVID-19 vaccines.65 Although patients with solid tumors had adequate immune response in 98%, this response was only 85% in patients with HM and was particularly impaired in patients having received immunosuppressive therapies such as anti-CD20 therapies (70%) and stem cell transplantation (73%). As previously speculated, patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy demonstrated high seroconversion rates after vaccination (97%). Patients with prior COVID-19 infection demonstrated higher antispike IgG titers after vaccination.

A report on quantitative serologic responses and early clinical outcome in a cohort of 885 patients with HM who had received 1 and 2 doses of BNT162b2 demonstrated that both anti-CD20 therapies and treatment with Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitor (BTKi), ruxolitinib, and venetoclax were associated with strongly reduced or absent antibody responses.66 Patients on kinase inhibitor treatments or after an hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation or systemic chemotherapy more than 6 months before the first dose of vaccine had good antibody responses (Table 2). Severe breakthrough infections were reported in 9 (1%) of 885 fully vaccinated patients (6 required supplemental oxygen and 3e died of COVID-19 pneumonitis). Six (67%) patients with breakthrough infection did not seroconvert after the second SARS-CoV-2 immunization.

Several other prospective studies confirmed the low antibody response after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with HM (Table 2), particularly in patients pretreated with rituximab. These studies also reported cases of breakthrough infections in partially or completely vaccinated patients.65-79

A comprehensive workup of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections among partially or completely vaccinated patients with HM was provided by an open web-based registry (EPICOVIDEHA) of the European Hematology Association Infectious Diseases Working Party.67 Most patients with breakthrough infections had lymphoproliferative disorders (>80%), received an active treatment within 3 months before vaccination (68.1%), were males (61.1%), and were >50 years of age (85.5%). Eighty-seven patients (77%) were considered fully vaccinated, and COVID-19 was diagnosed more than 2 weeks after the second vaccination. Overall, 79 (60.4%) patients had a severe or critical infection. Seventy-five patients (66.4%) were admitted to the hospital, with 16 (21.3%) to an ICU, and 10 of 16 required mechanical ventilation. At 30 days after COVID-19 diagnosis, the overall mortality rate was 12.4% (N = 14). No statistical differences were observed between partially or fully vaccinated patients (15.4% vs 11.5%; P = .734) and patients achieving a serologic response vs nonresponders (13.3% vs 15.6%; P = 1). Multivariable analysis showed that the only factor independently related to the risk of death was age.

The first prospective evaluation of a booster dose was reported in a well-described cohort of patients with cancer (all but 1 with HM) and demonstrated a high booster-induced seroconversion of 56%, even in patients that were previously treated for their malignancy.80 Prior BTKi or anti-CD20 treatment was associated with inferior postbooster seroconversion and anti-S IgG titers. All patients remaining seronegative after the booster vaccination had B-cell malignancies. Of the seronegative patients, booster-induced T-cell responses were detectable in 80% of evaluable patients.

Two observational studies confirmed an improvement of the immune response after a booster dose of COVID-19 vaccine in patients with HM, and 41.7% to 65% of patients seroconverted.69,81 Again, previous treatment with anti-CD20 antibodies had the strongest adverse impact on immunogenicity, whereas most patients treated with BTKi were able to seroconvert after a third booster vaccination.80

When comparing different HM subtypes, patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and indolent lymphoma had the lowest seroconversion rate after COVID-19 vaccination.78,82 In contrast, the highest seroconversion rates in descending order were reported in patients with smoldering myeloma, hairy cell leukemia, Hodgkin lymphoma, myelodysplastic syndrome, chronic myeloid leukemia, myeloproliferative disorders, acute myeloid leukemia, multiple myeloma, acute lymphoid leukemia, T-cell lymphoma, and aggressive lymphoma.

Predictive markers other than the type of HM (lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukemia) were the levels of different cell types in the peripheral blood (T cells, B cells, neutrophils, natural killer cells, and monocytes), IgG count, and clinical and treatment characteristics (male sex, age, and B-cell targeting treatment within 12 months before vaccination).70,78,83,84

Results of several studies indicate that the time from last rituximab infusion (<6 months, <12 months) is associated with lower rates of serologic conversion,66,69,70,73,75,79,81 and hardly any HM patients treated with rituximab within 6 months before vaccination had detectable neutralizing antibodies.85 As up to 80% of anti-CD20–treated patients with HM were able to mount a specific T-cell response,73 it is possible that SARS-CoV2 vaccines may generate a cellular protection even at the time of anti-CD20 antibody induced B-cell depletion.

After a 2-dose vaccination, the antibody persistence was reported to hold up to 6 months in healthy individuals.86 The duration of protection from reinfection and severe disease after booster vaccination is currently the subject of extensive debate. Cellular immunity might provide long-term protection (in contrast to waning humoral immunity), and as recently demonstrated, even T-cell response to the Omicron variant is preserved in most vaccinated individuals, albeit with reduced reactivity in approximately 20% of individuals.87

Of note, vaccination with initial mRNA-1273 or Ad26.CoV2.S vaccination, as well as mRNA-1273 booster compared with BNT162b2, yielded higher titers of antiviral antibodies in patients with HM, unlike the nearly identical efficacy of mRNA vaccines in healthy volunteers.82 Differences in the amount of spike mRNA, differences in the exact coding sequence of the mRNA or lipid composition of the vaccines, and different dosing schedules may alter immunogenicity of the vaccines in patients with HM.80,82

Many countries now offer a fourth dose of COVID-19 vaccine to special risk groups.88 The first case series of solid-organ transplant recipients reports successful second boosting in up to 50% of negative and in 100% of patients with low-positive titer.89 Data on patients with HM have not been reported. However, a second booster vaccination should be offered to all patients with hematologic malignancy.

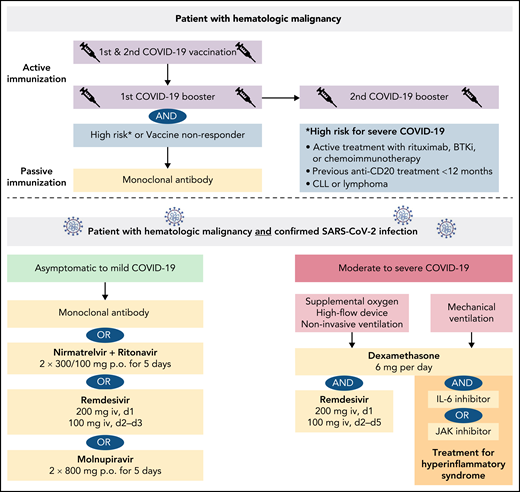

In summary, the vaccine-induced immunity is significantly lower in patients with lymphoid malignancies and patients receiving active B cell–depleting treatment, whereas vaccine-induced immunity in patients with myeloid malignancies or Hodgkin lymphoma is hardly impaired. Hematologic patients with a deficient vaccine response need other protective measures to prevent or minimize the risk of breakthrough infections, as discussed in the following chapter of antiviral therapies (Figure 1).

Management of a patient with hematologic malignancy during the pandemic.

Antiviral therapies

Because a large subgroup of patients with HM does not respond adequately to COVID-19 vaccination, early therapeutic or prophylactic measures are needed to prevent severe COVID-19. A large variety of options have been tested over the last 2 years. In terms of the current dominating Omicron variant, the antiviral drugs nirmatrelvir-ritonavir, remdesivir, and molnupiravir retain their efficacy against Omicron compared with earlier variants of concern.90-92

Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir

The oral protease inhibitor nirmatrelvir inhibits the SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease that is critical for viral replication.93 Nirmatrelvir is administered in combination with ritonavir, a prodrug to inhibit the metabolism of nirmatrelvir. As a result, relevant CYP3A4 drug interactions should be noted (eg, kinase inhibitor, venetoclax). The evaluation of protease inhibition for COVID-19 in high-risk patients (EPIC-HR) phase 2/3 trial evaluating nirmatrelvir/ritonavir in high-risk patients treated within 3 days of COVID-19–related symptom onset demonstrated a relative risk reduction of 90% for hospitalization or death compared with placebo, and the viral load was lower at day 5 of treatment.94 Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir received emergency use authorization for the treatment of mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in SARS-CoV-2–positive patients at high risk for severe COVID-19.

Remdesivir

The nucleotide analog remdesivir was the first approved drug for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2. A 10-day course of remdesivir was superior to placebo in shortening the time to recovery in hospitalized patients with lower respiratory tract infections but did not reduce mortality.95 The randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 Study GS-US-540-9012 (PINETREE) evaluated the efficacy of a 3-day course of remdesivir in high-risk, nonhospitalized patients with COVID-19, including a small subgroup of immunocompromised patients (4.1%).96 Early remdesivir treatment resulted in an 87% lower risk of hospitalization or death than placebo (hazard ratio, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.03-0.59; P = .008). Remdesivir received emergency use authorization for the treatment of COVID-19 patients with pneumonia requiring supplemental oxygen (low- or high-flow oxygen or other noninvasive ventilation at the start of treatment).

Molnupiravir

Molnupiravir is an oral, small-molecule antiviral prodrug that is active against SARS-CoV-2 by increasing the frequency of viral RNA mutations and impairing SARS-CoV-2 replication.97 MOVe-OUT is a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial that evaluated molnupiravir therapy starting within 5 days after onset of symptoms in nonhospitalized, unvaccinated patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 (including 2.2% patients with active cancer) and demonstrated a relative risk reduction of hospitalization or death of 30% (relative risk, 0.70; 95% CI: 0.49-0.99).98 Because of the mechanism of action, an increased teratogenicity is of concern, particularly in younger, childbearing, pregnant, and lactating patients. Molnupiravir is indicated for the treatment of COVID-19 in patients with HM who do not require supplemental oxygen to reduce the risk of progression to severe COVID-19.

Convalescent plasma

Virus-neutralizing antibodies contained in convalescent plasma of recovered individuals may be used for the therapy of immunocompromised patients with SARS-CoV-2. Several observational studies have demonstrated reduced symptoms and mortality in patients with COVID-19 after convalescent plasma transfusion.99-101 Although case series showed some effectiveness among immunocompromised patients with HM, large clinical trials did not find evidence for therapeutic effects of convalescent plasma.102-109 Therefore, convalescent plasma therapy represents an option for individual patients with HM but should not be applied routinely.

Dexamethasone

Early use of oral or IV dexamethasone (at a dose of 6 mg once daily) for up to 10 days in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 resulted in a lower mortality among patients on respiratory support (oxygen or mechanical ventilation) as evaluated with the Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy Study (RECOVERY).110 Dexamethasone is indicated in the treatment of COVID-19 in adults who require supplemental oxygen therapy.

Monoclonal antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies directed to the S protein can neutralize the ability of the virus to bind and fuse with the target host cell. The neutralizing reactivity of FDA-approved and investigational therapeutic monoclonal antibodies against Omicron and other variants of concern was evaluated recently.91,111 In summary, several monoclonal antibodies (etesevimab-bamlanivimab, imdevimab-casirivimab) lose their neutralizing activity and are not effective against Omicron. Substantial inhibitory activity was demonstrated for tixagevimab-cilgavimab (although with reduced neutralizing capacity compared with Beta or Gamma) and for sotrovimab, albeit to a much lesser extent. Extended studies including antigenic characterization of the emerging Omicron sublineages demonstrated that in 17 of 19 neutralizing monoclonal antibodies tested (including sotrovimab), BA.2 exhibited marked resistance.112 Only the recently authorized monoclonal antibody bebtelovimab could adequately cover all sublineages of the Omicron variant.

Sotrovimab

The neutralizing antibody sotrovimab binds to the receptor-binding motif that engages the ACE2 receptor and demonstrated activity against several variants of concern including Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Lambda.113 The COVID-19 Monoclonal Antibody Efficacy Trial–Intent to Care Early (COMET-ICE) demonstrated that sotrovimab reduces the risk of severe COVID-19 in high-risk ambulatory patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 (relative risk reduction, 85%; 97.24% CI, 44-96; P = .002).114 Following these results, sotrovimab has been approved for the treatment of COVID-19 in patients who do not require oxygen supplementation but are at increased risk of progressing to severe COVID-19. Sotrovimab retained activity against Omicron BA.1 sublineages, but its activity against BA.2 has remarkably dropped.112 Following these findings, the FDA has limited use of sotrovimab to regions where the Omicron BA.2 subvariant is not the dominant subvariant.

Tixagevimab and cilgavimab

The phase 3 double-blind, placebo-controlled trial for pre-exposure prophylaxis of COVID-19 in (PROVENT) (#NCT04723394) evaluated AZD7442, a combination of 2 long-acting antibodies, tixagevimab and cilgavimab, to prevent symptomatic COVID-19 including patients with a poor vaccine response. The data have not been published, but a press release stated that tixagevimab/cilgavimab reduced the risk of developing symptomatic COVID-19 by 83% compared with placebo.115 The combination is authorized for the emergency use as pre-exposure prophylaxis for prevention of COVID-19 in moderately to severely immunocompromised patients or for whom an active COVID-19 vaccination is not possible.116 This includes patients with active HM, patients with HM receiving immunosuppressive therapy, and transplant recipients. The FDA has amended its Emergency Use Authorization to increase the recommended dose of each drug from 150 to 300 mg. The revision was based on in vitro data showing that tixagevimab/cilgavimab retain a greater degree of neutralizing activity against the BA.2 Omicron variant (5.4-fold reduction vs the ancestral virus).117 The duration of protection is estimated to be 9 to 12 months and, in contrast to other monoclonal antibodies, this antibody-cocktail is given by intramuscular administration.

Bebtelovimab

The FDA has granted emergency approval for LY-CoV1404 (bebtelovimab), as the antibody retains potent neutralizing activity against both Omicron sublineages BA.1 and BA.2 in pseudovirus neutralization studies.112 However, clinical data evaluating bebtelovimab alone or in combination in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 are still pending (#NCT04634409).

Impact of Omicron SARS-COV-2 variant

Epidemiologic data from Africa showed a decoupling of hospitalizations and deaths from infections while Omicron was circulating.118 The first population-based study of patients with CLL with COVID-19 from eastern Denmark evaluated the severity and outcome before and after Omicron predominance.119 High ICU admission rates before Omicron emergence might reflect the protection by booster vaccination and improved care for patients with COVID-19 such as full implementation of early antiviral treatment with monoclonal antibodies and treatment with remdesivir of hospitalized patients. Albeit the numbers of patients reported are small, the survival rate decreased with the emergence of ο BA.2 sublineage, indicating an impaired efficacy of sotrovimab against Omicron available at that time.

Psychologic distress

Patients with HM often report increased psychologic stress levels, as they are part of a population at increased risk of contracting COVID-19. Evaluation of the psychologic status of outpatients with HM receiving infusional therapies or other antineoplastic treatments demonstrated an increased level of anxiety and depression. Up to 36% of patients with HM fulfilled the criteria for a posttraumatic stress disorder.120 Women and younger patients were found to be more vulnerable to anxiety and posttraumatic disorders. Concerns about the impact of COVID-19 on cancer management were significantly associated with fear of cancer recurrence among responder in remission.121 Other stressors were social distancing and limited social interactions induced by the pandemic.122

Summary: management of patients with hematologic malignancy during the SARS-COV-2 pandemic

For patients with HM, the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic represents a particular challenge for at least 2 reasons. First, their immune system may be impaired by the interaction of cancer cells with different immune cell subsets, inducing a state of anergy. Second, the antineoplastic therapies themselves, and in particular anti-CD20 antibodies or chemotherapies, act as potent immunosuppressive agents. As a consequence, patients with HM have an increased risk for a severe course of COVID-19, with a hospitalization rate of more than 50% and a case fatality rate of approximately 30%. Advanced age, comorbidities, and type of HM seem to be additional risk factors.

Patients with HM show short-lasting protection after SARS-CoV-2 infection with detection of specific antibodies for less than 4 months and signs of T-cell exhaustion, indicating a lack of long-term immunity and an increased risk of reinfection.

Active immunization by vaccination remains an important element of protection for these patients. As the recent SARS-CoV-2 variants of concerns have increased their transmissibility, a first and second booster vaccination should be given to all patients with HM regardless of serologic results.

As the protection by COVID-19 vaccines is significantly reduced in patients with lymphoid malignancies or patients receiving B cell–directed treatments, preventive passive immunization with monoclonal antibodies (pre-exposure prophylaxis) is another milestone in containment of the pandemic and should be offered to all such patients with HM and to vaccine nonresponders.

Antiviral drugs and monoclonal antibodies for early treatment of COVID-19 have become available and should be given to all SARS-CoV-2–infected patients with HM to prevent severe or fatal courses. The treatment selection is based on efficacy against the current dominating SARS-CoV-2 variants, potential contraindications, drug interactions, and availability in different health care systems.

Moreover, we feel that it is important to establish specific programs and registries at a national and global level for patients with HM during this historic pandemic because they represent a particularly vulnerable group of patients with regard to COVID-19 in our society.

Authorship

Contribution: P.L. performed a systematic review and wrote an initial draft; M.H. conceived, reviewed, and edited the manuscript; and both authors approved the final version.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: P.L. research funding, travel grants and honoraria by AbbVie, F. Hoffmann-LaRoche, Janssen-Cilag and AstraZeneca. M.H. consultant or advisory board member, honoraria and research support by AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, F. Hoffmann-LaRoche, Gilead, Janssen-Cilag, and Mundipharma.

Correspondence: Petra Langerbeins, Department I of Internal Medicine, Center for Integrated Oncology Aachen Bonn Cologne Duesseldorf, German CLL Study Group, CECAD Cluster of Excellence, University of Cologne, Kerpener Str 62, 50937 Cologne, Germany; e-mail: petra.langerbeins@uk-koeln.de.