Key Points

CCR9 is expressed on the majority of cases of T-ALL but not on normal T cells or other essential tissues.

Anti-CCR9 CAR-T cells were highly potent against T-ALL in vitro and in vivo.

Abstract

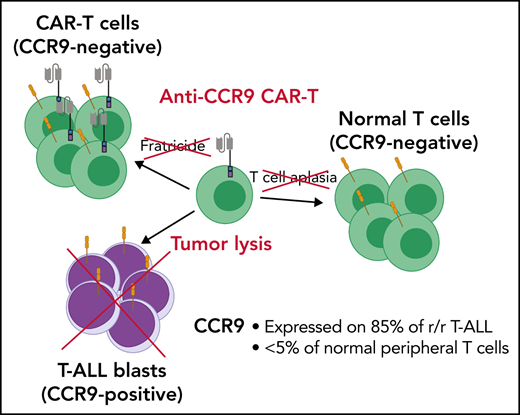

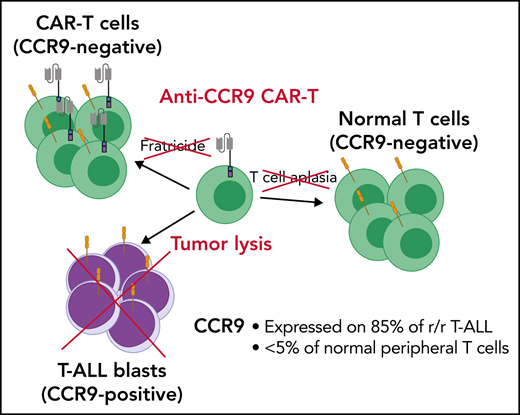

T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) is an aggressive malignancy of immature T lymphocytes, associated with higher rates of induction failure compared with those in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The potent immunotherapeutic approaches applied in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, which have revolutionized the treatment paradigm, have proven more challenging in T-ALL, largely due to a lack of target antigens expressed on malignant but not healthy T cells. Unlike B cell depletion, T-cell aplasia is highly toxic. Here, we show that the chemokine receptor CCR9 is expressed in >70% of cases of T-ALL, including >85% of relapsed/refractory disease, and only on a small fraction (<5%) of normal T cells. Using cell line models and patient-derived xenografts, we found that chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells targeting CCR9 are resistant to fratricide and have potent antileukemic activity both in vitro and in vivo, even at low target antigen density. We propose that anti-CCR9 CAR-T cells could be a highly effective treatment strategy for T-ALL, avoiding T cell aplasia and the need for genome engineering that complicate other approaches.

Introduction

T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) is an aggressive cancer arising from the malignant transformation of immature Tcell precursors. It accounts for ∼15% and 25% of cases of ALL in children and adults,1 respectively, and typically presents with leukocytosis or cytopenia(s), with frequent extramedullary manifestations that include central nervous system infiltration and a mediastinal mass. Treatment is with multi-agent cytotoxic chemotherapy.2 Historically, outcomes have been worse than for patients with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), but with contemporary, minimal residual disease (MRD)-directed approaches,3 survival in children with B-ALL and T-ALL is now similar, with cure rates of >90%.4,5 In adults, long-term survival is much lower, approaching 50% in patients who can tolerate intensive chemotherapy.1,6,7 However, just less than half of patients relapse after standard therapy or fail to respond to standard therapy. These patients have a poor prognosis, with a median overall survival of ∼8 months.8 New treatment options that impart meaningful survival benefits are lacking, with <50% of children and <10% of adults attaining sustained remissions.9,10

In relapsed/refractory (r/r) T-ALL, the standard approach to attaining remission is with intensive re-induction chemotherapy followed by allogeneic transplantation, with regimens typically associated with significant toxicity and high failure rates. Unlike B-ALL, for which highly potent immunotherapies such as the bispecific T cell engager blinatumomab,11-13 the antibody-drug conjugate inotuzumab ozogamicin,14 and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells15 have revolutionized the treatment paradigm, no specific immunotherapies are available for T-ALL. Perhaps the most promising advance in r/r B-ALL is CAR-T cells, which lead to high rates of deep and sustained remissions, even in advanced and refractory disease.15,16 Application of CAR-T cell therapy to patients with T-ALL is highly desirable.

Due to a lack of tumor-specific antigens, in B-ALL, CAR T cells target pan-B cell antigens such as CD19 or CD22, leading to loss of normal B cells. However, targeting a pan-T cell antigen requires additional considerations. First, unlike B cell aplasia, which is well tolerated, depletion of normal T cells may induce life-threatening immunodeficiency.17 Second, CAR-T cells may target each other during manufacture and after administration.18 This so-called “fratricide” precludes CAR-T targeting of pan-T cell antigens without the use of complex genome editing or protein-retention techniques to prevent CAR-T cell expression of the cognate antigen.

To avoid these problems, identification of an antigen selectively expressed on T-ALL blasts but not normal T cells or other essential cell types is critical. Here, we propose the chemokine receptor CCR9 (or CD199) as such a target. CCR9 is a 7-pass transmembrane G–coupled receptor for the natural ligand CCL2519 (Figure 1D), and in mice it is expressed in gut intraepithelial γδ T cells but <5% of normal circulating T cells and B cells.20 We show that CCR9 is expressed on a high proportion of cases of r/r T-ALL but <5% of normal T cells. Furthermore, we generate anti-CCR9 CAR-T cells and report robust antitumor efficacy in multiple in vitro and in vivo models of T-ALL, with no evidence of fratricide or lysis of normal T cells.

CCR9 is expressed on T-ALL blasts with limited expression on normal peripheral blood cells. (A) Heatmap showing genes that are solely expressed in MOLT-4 T-ALL cells (red) compared with 35 normal tissue (blue; n = 172 samples) using subtractive transcriptomics from data from the Human Protein Atlas.23(B-C) CCR9 gene expression as determined by RNA-sequencing from pediatric patients with T-ALL from St. Jude’s Hospital (Memphis, TN).24 Pie chart (B) shows distribution of patients considered CCR9+ (fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped fragments [FPKM] >2.0), while scatter chart (C) shows CCR9 expression according to genetic subgroup. (D) Expression of CCR9 on 102 cases of primary T-ALL, proportion of positive blasts. (E) CCR9 antigen density of positive samples, antibodies bound per cell. (F) Expression of CCR9 on peripheral leucocytes in healthy donors. Mono, monocytes; mRNA, messenger RNA; NK, natural killer cells; RPKM, reads per kilobase of transcript per million reads mapped; TCM, T central memory; TEM, T effector memory; TEMRA, terminally differentiated effector memory; TSCM, T stem cell memory; UNK, unknown.

CCR9 is expressed on T-ALL blasts with limited expression on normal peripheral blood cells. (A) Heatmap showing genes that are solely expressed in MOLT-4 T-ALL cells (red) compared with 35 normal tissue (blue; n = 172 samples) using subtractive transcriptomics from data from the Human Protein Atlas.23(B-C) CCR9 gene expression as determined by RNA-sequencing from pediatric patients with T-ALL from St. Jude’s Hospital (Memphis, TN).24 Pie chart (B) shows distribution of patients considered CCR9+ (fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped fragments [FPKM] >2.0), while scatter chart (C) shows CCR9 expression according to genetic subgroup. (D) Expression of CCR9 on 102 cases of primary T-ALL, proportion of positive blasts. (E) CCR9 antigen density of positive samples, antibodies bound per cell. (F) Expression of CCR9 on peripheral leucocytes in healthy donors. Mono, monocytes; mRNA, messenger RNA; NK, natural killer cells; RPKM, reads per kilobase of transcript per million reads mapped; TCM, T central memory; TEM, T effector memory; TEMRA, terminally differentiated effector memory; TSCM, T stem cell memory; UNK, unknown.

Methods

Cell lines and maintenance

The HEK-293T cell line was cultured in Iscove Modified Dulbecco Medium (Lonza), and other cell lines were cultured in complete RPMI 1640 (Lonza), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM GlutaMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All cell lines were routinely tested for mycoplasma by using the EZ-PCR Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Biological Industries), and the identity of T-ALL cell lines was verified by short tandem repeat analysis using the PowerPlex 1.2 system (Promega) in June 2017. All cell lines were obtained from the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (DSMZ).

Generation of CCR9-KO cells by CRISPR/Cas9 nicking strategy

CCR9–versions of P12-Ichikawa and PF382 T-ALL cell lines were generated by using CRISPR/Cas9 genome engineering. Guide RNAs (gRNAs) were designed targeting exon 4 of the CCR9 gene (https://chopchop.cbu.uib.no/), choosing the guides with the top quality and least off-target score: gRNA 1, TGGAAGACTACGTTAACTTC; gRNA 2, GTACTGGCTCGTGTTCATCG. The Alt-R CRISPR RNP system (IDT) was used per manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were electroporated by using AMAXA Nucleofector (Lonza). Once confirmed by flow cytometry, knockout cells were validated at the DNA level. DNA was extracted by using the Qiagen DNeasy kit followed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification using specific primers (forward, 5′- CCCTTGCAGAGCCCTATTCC; reverse, 5′- ACCTTCAGGGTCAAGACAGC).

Flow cytometry and primary T-ALL samples

Primary T-ALL tumor samples were obtained from the UK CellBank collection or from local biobanks at Great Ormond Street Hospital or University College London Hospital. The primary T-ALL samples used in primary in vitro killing experiments were all bone marrow samples collected at the time of initial diagnosis and were respectively derived from an adult male with high count T-ALL (genetics unknown), an adult female with high count T-ALL (genetics unknown), and a 14-year-old boy with STIL-deleted T-ALL. Quantification of CCR9 antigen density was performed by using BD Quantibrite beads (BD Biosciences) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Flow cytometry was performed on a BD Fortessa LSR II instrument. A list of antibodies is included in the supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site).

Retroviral transduction of T cells

CAR constructs were expressed in the SFG vector backbone. Viral supernatant was generated and peripheral blood mononuclear cell transductions performed as previously described.21,22

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting–based coculture and cytotoxicity assays

Target cells were prelabeled with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) and effector cells with CellTrace Violet (both Invitrogen). Co-cultures were performed with 50 000 target cells per well in a 96-well plate (25 000 cells for primary samples).

After 48 hours (72 hours for primary tumor samples), the plate was centrifuged to pellet cells, and 100 μL of supernatant was removed from the 1:8 effector-to-target (E:T) ratio wells for cytokine assays. Cytokines were measured by using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (BioLegend) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

After staining with appropriate antibodies and fixable viability dye, cells were resuspended in 100 μL of 0.4% paraformaldehyde/phosphate-buffered saline. Data acquisition was made on the Beckman Coulter Cytoflex instrument. Assays were performed in triplicate. To minimize the impact of alloreactivity, cytotoxicity for CAR-T cells was normalized to that for nontransduced (NT) cells at the same E:T ratio.

T-cell proliferation assay

Effector NT or CAR T cells were labeled with CFSE by incubating the cells for 5 minutes at a concentration of 1 µM in complete media, before 2× washes with complete media. A sample of cells were fixed in 0.4% paraformaldehyde and kept at 4°C for later analysis by flow cytometry (FCM). Cells were then plated at 2.5 × 105/mL, 100 μL in wells of a 96-well plate (25 000 cells per well), in triplicate. Irradiated (40 Gy) target cells (MOLT4 or SupT1) were then added to the wells at a 1:2 ratio. After 7 days, effector cells were counted, and a sample taken for FCM. T-cell proliferation was assessed by CFSE dilution compared with baseline sample and by fold-expansion.

Mouse models of T-ALL

This work was performed under a UK Home Office–approved project license and was approved by the UCL Biological Services Ethical Review Committee. Female NSG mice aged 6 to 12 weeks were obtained from Charles River Laboratories and assigned randomly to control and experimental groups.

The MOLT4-Fluc cells used in the assay were generated by lentiviral transduction of the parental cell line with a plasmid-expressing luciferase. Patient-derived xenograft (PDX) samples were developed at the Institute of Child Health by Professor Owen Williams and were derived from an 11-year-old boy with hyperdiploid T-ALL (PDX 1078), a 5-year-old boy with TLX3-rearranged T-ALL (PDX 1139), a 14-year-old boy with STIL1-deleted T-ALL (PDX 782), a 1-year-old girl with ATM-deleted T-ALL (PDX 682), a 10-year-old boy with biallelic CDKN2A-deleted T-ALL (PDX 602), and an 8-year-old boy with CDKN2a/STIL1-deleted T-ALL (PDX 352).

Mice were intravenously injected with cell suspensions via the tail vein, and tail vein bleeds of 50 μL were undertaken as indicated in the text. Blood, spleen, and bone marrow were analyzed by FCM. Human T cells were identified as CD45brightCD3bright and T-ALL cells as CD45dimCD3dim–.

For experiments with a survival end point, mice were weighed at least twice weekly. Animals with >10% weight loss or those displaying evidence of graft-versus-host disease or disease progression, including hunched posture, poor coat condition, reduced mobility, piloerection, or hindlimb paralysis, were killed. Bioluminescence imaging of mice was performed by using the IVIS Lumina III system (PerkinElmer). General anesthesia was induced and maintained by using inhaled isoflurane. After induction, intraperitoneal injection of luciferin (200 μL via 27-gauge needle) was undertaken. After 2 minutes, mice were placed in the imaging chamber. Simultaneous optical and bioluminescence imaging was performed.

Statistical analyses

Unless otherwise noted, data are summarized as mean ± standard deviation. A t test was used to determine statistically significant differences between samples for normally distributed variables, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for nonparametrically distributed variables. Paired analyses were used when appropriate. When ≥3 groups were compared, one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons with α = 0.05 were used. For longitudinal outcomes, comparisons were made by using two-way analysis of variance or a mixed effects model, with multiple comparisons between groups made by Šidák’s test, with α = 0.05. Survival curves were generated by using the Kaplan-Meier method. Graph generation and statistical analyses were performed by using GraphPad Prism version 9 (GraphPad Software).

Results

CCR9 is highly expressed in T-ALL blasts with limited expression on normal immune cells

We sought to identify potential immunotherapy targets for T-ALL. We first reasoned that any tractable T-ALL target must be expressed in T-ALL cells but not normal tissues. Thus, we analyzed the collated gene expression profiles of 35 normal tissues (n = 172 samples) compared with MOLT-4 cells, a TAL1-positive T-ALL cell line included in the Protein Atlas Cancer compendium. Using subtractive transcriptomics, we identified 12 transcripts uniquely expressed in MOLT-4 cells but in no other normal tissue (Figure 1A).23 Of these, CCR9 was the most attractive, being predicted to reside on the cell surface and thus amenable to immunotherapy.

Analysis of the largest published pediatric T-ALL data set shows that CCR9 is expressed in 80% of T-ALL cases at the RNA level at diagnosis, with notable expression in most HOXA-positive patients, half of whom have MLL gene rearrangements (Figure 1B-C). CCR9 was expressed in 12 of 19 patients with early T cell precursor (ETP) T-ALL in this cohort, thus highlighting the potential of CCR9-directed therapy in the highest risk patients. There was no significant difference in the mutation profile of CCR9+ patients compared with CCR9– patients, apart from a lower incidence of chromosome 6q deletions (P = .002) and a higher incidence of NOTCH1 mutations (P < .0001) (supplemental Figure 1).24

We examined CCR9 status of primary cases of T-ALL using flow cytometry (FCM). Seventy-four (73%) of 102 cases expressed CCR9 (defined as expression on >20% of blasts), with expression enriched in cases of r/r disease: 38 (65%) of 59 diagnostic vs 11 (85%) of 13 relapsed vs 26 (86%) of 30 primary refractory (Figure 1D; supplemental Figure 2). The 20% threshold was selected to defined positivity, as blast expression of CCR9 was typically dim but homogeneous according to flow cytometry. The median number of copies of CCR9 per cell was 1732 (1320 diagnostic vs 1889 relapsed vs 2175 refractory) (Figure 1E). Expression was similar in pediatric (72% CCR9+) and adult (75% CCR9+) cases. True biphenotypic expression with CCR9+ and CCR9– blast populations was noted in only 3 of 102 cases (supplemental Figure 2, highlighted in red). In diagnostic samples in which full immunophenotyping was available, 6 of 32 cases were identified as ETP ALL phenotype. Four (67%) of six ETP cases were CCR9+. In 3 cases in which matched diagnostic and relapse samples were available, CCR9 expression was preserved or increased upon relapse.

Next, to examine the potential for hematologic toxicity when targeting CCR9, we examined CCR9 expression on peripheral blood cells isolated from healthy donors. We found low levels of expression, limited to 11% of B cells and <5% of CD3+ cells. CCR9 was not expressed on monocytes, granulocytes, natural killer (NK) cells, or peripheral blood γ-δ T cells (Figure 1F). The median copy number on both positive B and T cells was lower than that seen in primary T-ALL, at <500 copies per cell. Expression of CCR9 on T cells was not clearly linked to CD4/CD8 identity, markers of differentiation (CD45RA/CCR7/CD95), or activation (HLA-DR) and did not change on stimulation of T cells with CD3/CD28 antibodies (data not shown).

We also evaluated CCR9 expression in thymic subsets and CD34+ marrow precursor cells from healthy donors, using quantitative PCR. As previously described, no CCR9 expression was seen in CD34 cells, with minimal expression in single-positive peripheral blood CD4 and CD8 cells, confirming FCM data. CCR9was expressed at low levels (<5% of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [GAPDH] signal) in early thymic T-cell precursors (DN1, single-positive CD3–) with somewhat higher expression in double-positive CD3+ (22% GAPDH signal) and single-positive CD3+ CD4 (8% GAPDH signal) and CD8 (8% GAPDH signal) thymic cells (supplemental Figure 3).

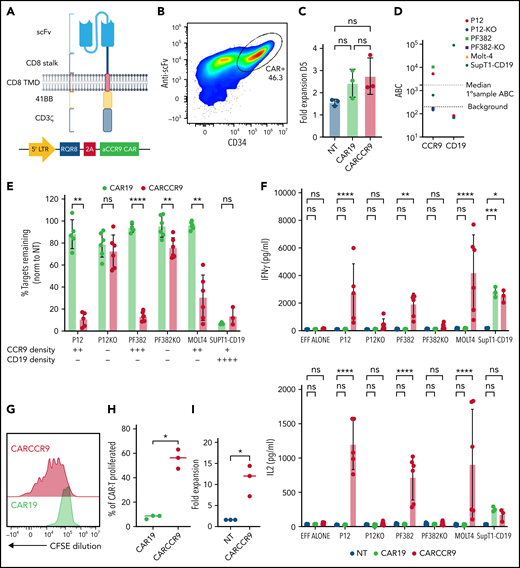

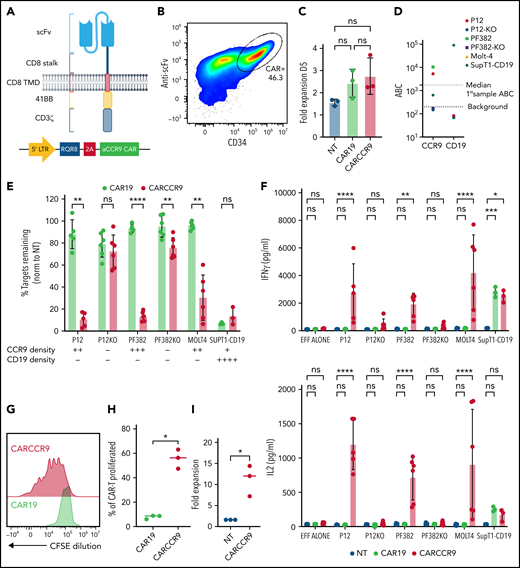

Anti-CCR9 CAR T cells are effective against T-ALL cell lines in vitro

We developed a novel binder against CCR9 by gene-gun vaccination of rats with a plasmid-encoding human CCR9, followed by hybridoma generation from lymphoid tissue of seroconverted animals. A single CCR9-specific hybridoma clone (P4T1) was identified, from which we generated a single-chain variable fragment. Anti-CCR9 single-chain variable fragment was cloned as a second-generation CAR, incorporating CD8 stalk/transmembrane domain and 4-1BB-CD3zeta endodomain25 (Figure 2A). This was encoded in a γ-retroviral vector with RQR8 marker/sort-suicide gene26 and used to transduce primary human T cells. CAR was detected directly on the surface of transduced cells by using an anti-Fab antibody (Figure 2B). T cells transduced with anti-CCR9 CAR expanded similarly to those transduced with a control CAR targeting CD19, with no evidence of fratricide (Figure 2C). No CCR9+ cells were detected in the transduced cell product, suggesting “purging” of CCR9+ T cells (supplemental Figure 4a). Furthermore, there were no differences in expression of markers of differentiation (ie, CD45RA, CCR7), exhaustion (ie, T cell immunoglobulin-3, lymphocyte activation gene 3, programmed cell death protein 1), or activation (ie, CD71, HLA-DR, forward scatter) between CAR19 and CCR9 CAR-T cells after manufacture (supplemental Figure 4b-c).

Anti-CCR9 CAR has potent cytotoxicity against T-ALL cell lines in vitro. (A) Structure and vector design of anti-CCR9 and control anti-CD19 CAR used in the study, using “Campana” architecture with RQR8 marker/sort-suicide gene. (B) Expression of anti-CCR9 CAR on the surface of transduced T cells, detected by anti-murine Fab. (C) Fold expansion of NT, CAR19, or CARCCR9 cells 5 days after transduction. (D) Antigen density of CD19 and CCR9 on cell lines used in the study. (E) Cytotoxicity of CAR19 vs CARCCR9 against primary T-ALL cell lines, data normalized to NT condition, 48-hour coculture, data shown at 1:8 E:T ratio. (F) Secretion of interferon-γ (IFN-γ; top) and interleukin-2 (IL-2) (bottom) in 48-hour co-culture, 1:8 E:T ratio as in panel E. (G) Example flow plot of CFSE dilution on T cells after 7-day incubation with irradiated MOLT-4 cells at 1:2 ratio. (H) Quantification of T cell CFSE dilution, 3 donors. (I) Fold expansion of T cells after 7-day co-culture with irradiated SupT1 cells at 1:2 ratio, 3 donors. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001. ns, not significant. EFF, effectors.

Anti-CCR9 CAR has potent cytotoxicity against T-ALL cell lines in vitro. (A) Structure and vector design of anti-CCR9 and control anti-CD19 CAR used in the study, using “Campana” architecture with RQR8 marker/sort-suicide gene. (B) Expression of anti-CCR9 CAR on the surface of transduced T cells, detected by anti-murine Fab. (C) Fold expansion of NT, CAR19, or CARCCR9 cells 5 days after transduction. (D) Antigen density of CD19 and CCR9 on cell lines used in the study. (E) Cytotoxicity of CAR19 vs CARCCR9 against primary T-ALL cell lines, data normalized to NT condition, 48-hour coculture, data shown at 1:8 E:T ratio. (F) Secretion of interferon-γ (IFN-γ; top) and interleukin-2 (IL-2) (bottom) in 48-hour co-culture, 1:8 E:T ratio as in panel E. (G) Example flow plot of CFSE dilution on T cells after 7-day incubation with irradiated MOLT-4 cells at 1:2 ratio. (H) Quantification of T cell CFSE dilution, 3 donors. (I) Fold expansion of T cells after 7-day co-culture with irradiated SupT1 cells at 1:2 ratio, 3 donors. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001. ns, not significant. EFF, effectors.

We co-cultured anti-CCR9 CAR-T cells or control CAR-T cells targeting CD19 for 48 hours with a panel of T-ALL cell lines, which express CCR9 at varying surface densities (Figure 2D). To confirm specific anti-CCR9 functions, we included CCR9– variants of the P12-Ichikawa and PF382 cell lines (designated P12-KO and PF382-KO), generated by using CRISPR-Cas9. We showed specific cytotoxicity of anti-CCR9 CAR-T against CCR9+ cell lines (Figure 2E; supplemental Figure 4d), including at low target density of ∼400 molecules per cell (SupT1-CD19). A small degree of nonspecific kill (∼10%) above CD19 CAR was seen against the PF382-KO cell line but not against the P12-KO cell line, perhaps due to slightly higher basal activation. We also examined cytokine secretion and showed that anti-CCR9 CAR-T specifically secreted the pro-inflammatory cytokines interferon-γ and interleukin-2 only in coculture with CCR9+ cell lines (Figure 2F). Further, in 7-day CFSE dilution assays, anti-CCR9 CAR-T but not anti-CD19 CAR-T proliferated in response to CCR9+ target cells (Figure 2G-I), with >10-fold expansion seen over this period (Figure 2I).

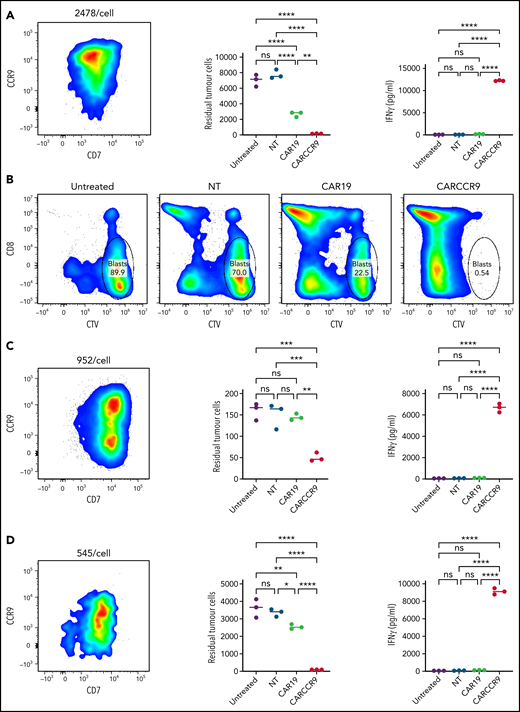

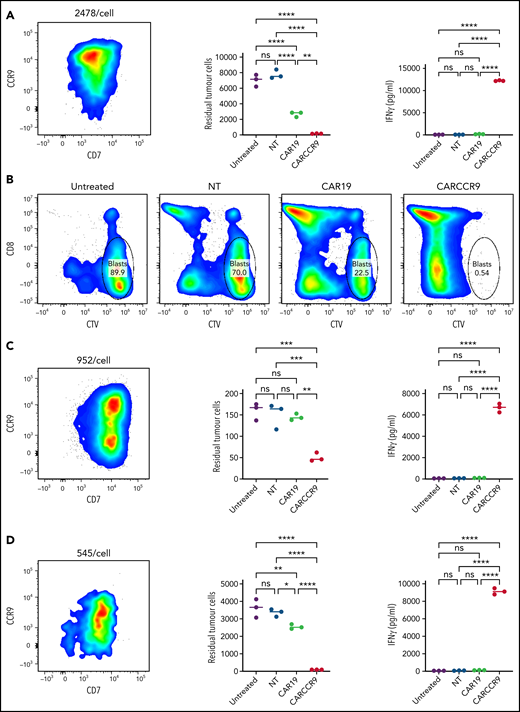

Anti-CCR9 CAR T cells were effective against primary T-ALL blasts in vitro

We isolated blasts from peripheral blood of 3 patients with newly diagnosed T-ALL and confirmed CCR9 expression (89% vs 55% vs 56% blasts CCR9+, respectively) and antigen density by flow cytometry (2478 v 952 v 545 molecules per cell). We incubated blasts at a 1:1 ratio for 72 hours with NT, CAR19, or CARCCR9 cells, generated from healthy donor T cells. Compared with NT or CAR19 cells, CARCCR9 exhibited potent cytotoxicity and secretion of interferon-γ (Figure 3).

Anti-CCR9 CAR-T cells demonstrate potent cytotoxicity against primary T-ALL blasts in vitro. (A,C,D) NT, CAR19, or CARCCR9 cells from healthy donor T cells were incubated for 72 hours, at a 1:1 ratio with T-ALL blasts obtained from 3 separate patients. Flow cytometry of sample CCR9 density (left), quantification of remaining blasts (middle), and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) secretion (right) in patients 1 to 3, respectively. (B) Example flow cytometry gating from patient 1 at end of coculture. **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001. CTV, CellTrace Violet; ns, not significant.

Anti-CCR9 CAR-T cells demonstrate potent cytotoxicity against primary T-ALL blasts in vitro. (A,C,D) NT, CAR19, or CARCCR9 cells from healthy donor T cells were incubated for 72 hours, at a 1:1 ratio with T-ALL blasts obtained from 3 separate patients. Flow cytometry of sample CCR9 density (left), quantification of remaining blasts (middle), and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) secretion (right) in patients 1 to 3, respectively. (B) Example flow cytometry gating from patient 1 at end of coculture. **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001. CTV, CellTrace Violet; ns, not significant.

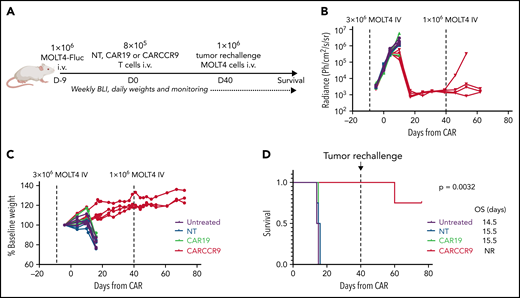

Anti-CCR9 CAR T cells were effective in murine cell line and PDX models of high-burden T-ALL

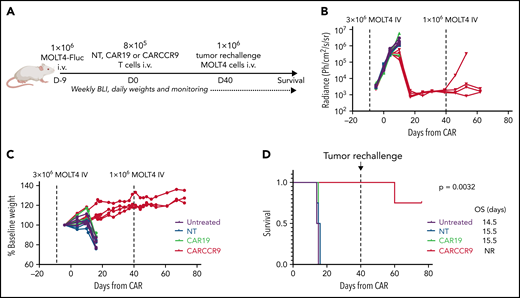

To test the anti-tumor potency of anti-CCR9 CAR-T in vivo, we intravenously injected NSG mice with 3 × 106 MOLT-4 cells, engineered to express firefly-luciferase (MOLT4-Fluc) (Figure 4A). Engraftment and exponentially increasing disease signal in marrow were confirmed by bioluminescence imaging at day 4 (D4) and D9 after injection (Figure 4B). Mice were treated on D9 (CAR D+0) with 8 × 105 intravenous NT, CAR19, or CARCCR9 cells, and disease was tracked by bioluminescence imaging and clinical assessment. While untreated mice and those receiving NT or CAR19 cells experienced disease progression, rapid weight loss, and death by CAR D+16, mice receiving CARCCR9 had disease regression, continued weight gain, and prolonged survival beyond CAR D+80 (Figure 4C-D). Furthermore, to confirm durable T cell memory, mice were re-injected with 1 × 106 MOLT4-Fluc on CAR D+40. In 3 (75%) of 4 mice, no increasing signal was detected in marrow, suggesting continued anti-CCR9 immunosurveillance. The remaining mouse died of progressive CCR9+ disease in the absence of detectable human T cells.

Anti-CCR9 CAR has potent antitumor activity in a MOLT4 xenograft model of T-ALL. (A) Schematic of murine MOLT4 model. (B) Bioluminescence signal in mice in study. (C) Mass of mice in study, expressed as percentage of starting mass. (D) Survival of mice in study. n = 4 per group. Experiment performed twice; data shown from representative experiment. BLI, bioluminescence imaging; NR, not reported; OS, overall survival.

Anti-CCR9 CAR has potent antitumor activity in a MOLT4 xenograft model of T-ALL. (A) Schematic of murine MOLT4 model. (B) Bioluminescence signal in mice in study. (C) Mass of mice in study, expressed as percentage of starting mass. (D) Survival of mice in study. n = 4 per group. Experiment performed twice; data shown from representative experiment. BLI, bioluminescence imaging; NR, not reported; OS, overall survival.

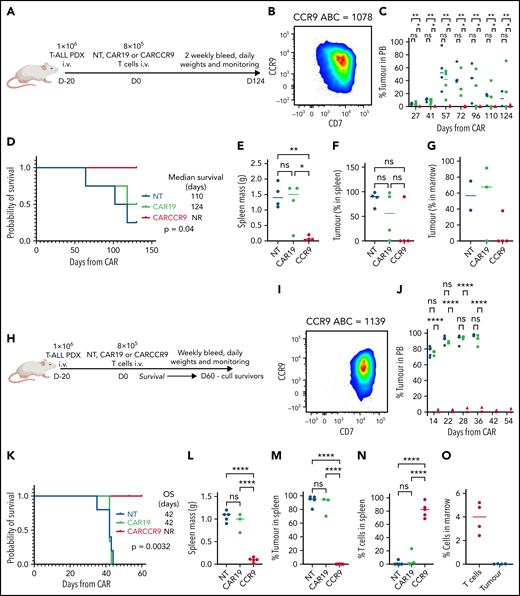

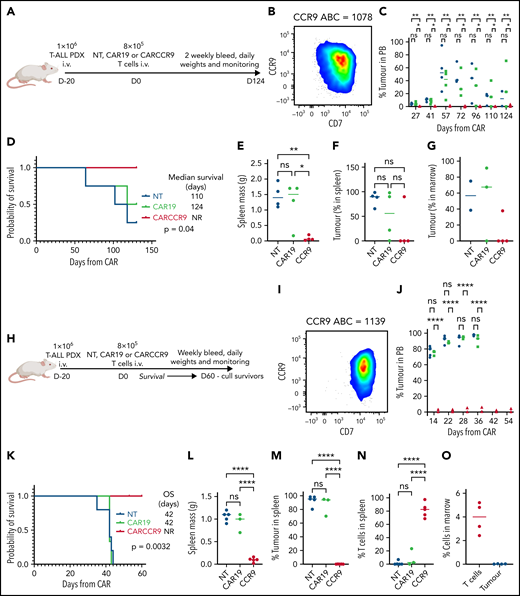

We also tested CARCCR9 in PDX models of T-ALL (Figure 5A-H), with antigen densities of 1078 (Figure 5B) and 1139 (Figure 5I) molecules per cell, respectively. NSG mice were injected with 1 × 106 primary blasts; then 8 × 105 NT, CAR19, or CARCCR9 cells were administered intravenously on D+20 (CAR D+0) (Figure 5A,H). In PDX model 1078 (Figure 5A-B), disease was slowly progressive: NT or CAR19 recipients displayed increasing blast percentages in peripheral blood (Figure 5C). Leukemic death occurred in most animals by CAR D+120 (Figure 5D), in association with massive splenomegaly (Figure 5E) and heavy infiltration of spleen (Figure 5F) and marrow (Figure 5G) with T-ALL. Late tumor regression associated with development of xeno–graft-versus-host disease was seen in one recipient of CAR19. By contrast, in recipients of CARCCR9, no tumor was detected in peripheral blood until the end of the study (Figure 5C), although low-level infiltration of T-ALL blasts was seen at necropsy in both spleen and marrow in 1 of 4 animals (Figure 5F-G). Blasts were CCR9+, and no T cells were detected.

Anti-CCR9 CAR has potent anti-leukemic activity in PDX models of T-ALL. (A) Flow diagram of PDX model 1, n = 4 per group. (B) Flow cytometry of CCR9 expression in blasts of PDX model 1. (C) Serial bleeds of mice, percent tumor of total CD45+cells. (D) Survival of mice in PDX model 1. (E) Spleen mass at necropsy in PDX model 1. (F) Tumor in spleen, percentage of total CD45+ cells. (G) Tumor in marrow, percentage of total CD45+ cells. (H) Flow diagram of PDX model 2, n = 5 (NT), n = 3 (CAR19), and n = 5 (CARCCR9). (I) Flow cytometry of CCR9 expression in blasts of PDX model 2. (J) Serial bleeds of mice in PDX model 2, percent tumor of total CD45+cells. (K) Survival of mice in PDX model 2. (L) Spleen mass at necropsy in PDX model 2. (M) Tumor in spleen in PDX model 2, percentage of total CD45+ cells. (N) T cells in spleen in PDX model 2, percentage of total CD45+ cells. (O) T cells and tumor in marrow of CARCCR9 recipients in PDX model 2, percentage of total CD45+ cells. *P < .05, **P < .01, ****P < .0001. NR, not reported; ns, not significant; OS, overall survival; PB, peripheral blood.

Anti-CCR9 CAR has potent anti-leukemic activity in PDX models of T-ALL. (A) Flow diagram of PDX model 1, n = 4 per group. (B) Flow cytometry of CCR9 expression in blasts of PDX model 1. (C) Serial bleeds of mice, percent tumor of total CD45+cells. (D) Survival of mice in PDX model 1. (E) Spleen mass at necropsy in PDX model 1. (F) Tumor in spleen, percentage of total CD45+ cells. (G) Tumor in marrow, percentage of total CD45+ cells. (H) Flow diagram of PDX model 2, n = 5 (NT), n = 3 (CAR19), and n = 5 (CARCCR9). (I) Flow cytometry of CCR9 expression in blasts of PDX model 2. (J) Serial bleeds of mice in PDX model 2, percent tumor of total CD45+cells. (K) Survival of mice in PDX model 2. (L) Spleen mass at necropsy in PDX model 2. (M) Tumor in spleen in PDX model 2, percentage of total CD45+ cells. (N) T cells in spleen in PDX model 2, percentage of total CD45+ cells. (O) T cells and tumor in marrow of CARCCR9 recipients in PDX model 2, percentage of total CD45+ cells. *P < .05, **P < .01, ****P < .0001. NR, not reported; ns, not significant; OS, overall survival; PB, peripheral blood.

PDX model 1139 was more aggressive (Figure 5H-I): recipients of NT or CAR19 displayed increasing ALL burden in peripheral blood over time (Figure 5J), with eventual leukemic death and massive splenomegaly in all animals (Figure 5K-L). By contrast, all CARCCR9 recipients had undetectable leukemia and disease-free survival until CAR D+60, when mice were culled due to development of graft-versus-host disease in some animals (median survival: NT, 42 days; CAR19, 42 days; CARCCR9, not reached; P = .0032) (Figure 5K). At the time of cull, all CCR9 CAR recipients had normal-sized spleens, with no detectable leukemia either in spleen (Figure 5L-M) or marrow (Figure 5O). Instead, human T cell infiltration was seen (Figure 5N-O).

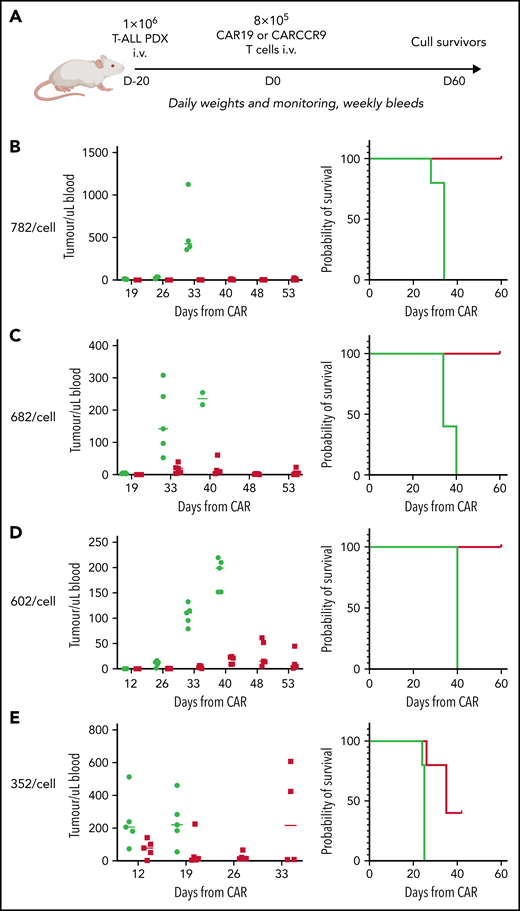

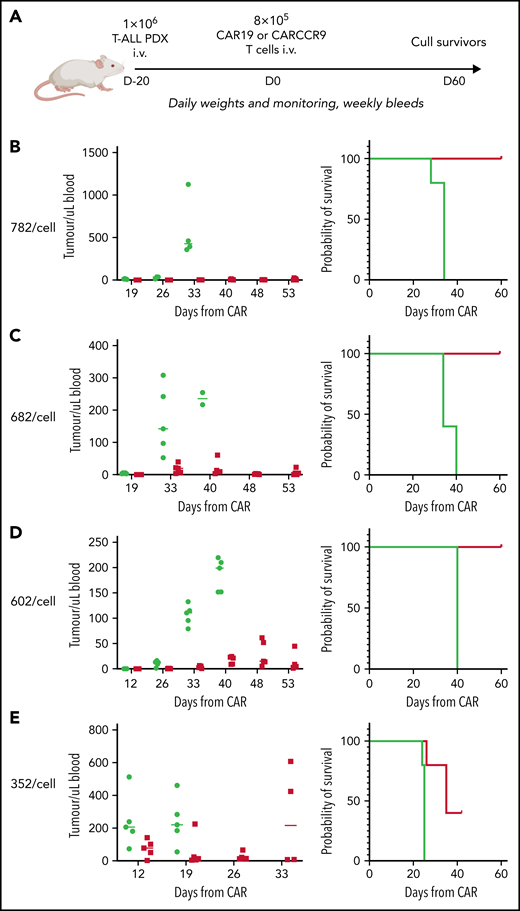

Finally, given the high potency of CARCCR9 shown thus far, we sought to investigate performance in vivo against low-density targets. Thus, PDX with antigen densities of 782, 682, 602, and 352 CCR9 per cell, respectively, were engrafted in NSG mice as before, with intravenous administration of 8 × 105 CAR19 or CARCCR9 cells on D+20 (Figure 6A). Even at these low densities, tumor clearance and long-term survival until CAR D+60 were seen in all recipients of CARCCR9, other than those engrafted with the lowest density PDX (352 molecules per cell) (Figure 6B-E). All surviving mice were culled at D60 due to development of graft-versus-host disease in the majority of animals. Notably, even in PDX 352, which was the most aggressive model tested, initial disease control was seen in 4 of 5 recipients of CARCCR9, followed by rapid relapse in all mice. This was associated with a survival benefit for CARCCR9 recipients (Figure 6E).

Anti-CCR9 CAR has potent anti-leukemic activity in PDX models of T-ALL with low CCR9 antigen density. (A) Flow diagram of low-density PDX models. (B-E) PDX models 3 to 7. CCR9 antigen density in PDX blasts before injection, molecules per cell (left), leukemic burden in peripheral blood in PDX models (center), and survival curves of animals in PDX models (right). n = 5 per group in all models.

Anti-CCR9 CAR has potent anti-leukemic activity in PDX models of T-ALL with low CCR9 antigen density. (A) Flow diagram of low-density PDX models. (B-E) PDX models 3 to 7. CCR9 antigen density in PDX blasts before injection, molecules per cell (left), leukemic burden in peripheral blood in PDX models (center), and survival curves of animals in PDX models (right). n = 5 per group in all models.

Discussion

In this study, we have shown that CCR9 is a viable immunotherapy target for T-ALL, expressed in the majority of patients with T-ALL but on <5% of peripheral blood T cells. Anti-CCR9 CAR T cells were not prone to fratricide, specifically lyzed T-ALL cell lines and primary tumors in vitro, and were highly potent in multiple in vivo models of T-ALL. Importantly, most patients with ETP ALL, a group with a particularly high risk of induction failure, and >85% of patients with r/r T-ALL expressed CCR9, suggesting that CCR9 CAR-T cell therapy could be a valuable therapy in those patients most at need of novel treatment approaches.

Currently, treatment options in r/r T-ALL are limited, and there is no standard of care. Most patients receive combination salvage chemotherapy, typically including a purine analogue such as nelarabine. However, salvage regimens are associated with considerable morbidity and mortality, with remission rates <40%.27 For the minority of patients who enter remission, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) is often considered as a curative option. However, allo-HSCT is only suitable for younger, medically fit patients and is associated with a mortality of up to 20%.28

Few investigational approaches to T-ALL are available. The anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody daratumumab is being tested in a clinical study in children with r/r T-ALL (#NCT03384654), but clinical data to date are limited. A single case report of off-label use in MRD-positive T-ALL showed that 2 patients attained MRD-negative remission, sustained to 10 months with continuous treatment,29 but no long-term data are currently available. Although CD38 is expressed by >70% of T-ALL cases,30 it is not an ideal immunotherapy target because it is also expressed by activated T cells, hematopoietic stem cells, and monocytes.31

Given the success of CAR-T cells in B-ALL, there is great interest in development of CAR-T for T-ALL. Multiple CAR-T targets have been proposed, most of which are pan-T cell antigens (CD3,32 CD4,33 CD5,34 and CD718,35) or are expressed on activated T cells (CD3836). We previously described targeting of TRBC1 or TRBC2 alleles at the T cell receptor β constant region, an approach that may spare a substantial proportion of normal T cells.21 However, this strategy is better suited to mature T cell malignancies, as surface expression of the T cell receptor is limited to ∼15% to 20% of T-ALL.1 CD1a is a potential target absent from normal T cells,37 but expression defines cortical T-ALL, which constitutes a good prognostic group. Hence, it is infrequently expressed in r/r disease (∼10% of r/r T-ALL cases).30

The most clinically advanced CAR-T targets for T-ALL are CD7 and CD5. CD7 is expressed on >90% of r/r T-ALL but also on both NK cells and normal (and CAR) T cells. To prevent CAR-T fratricide, strategies to knock-out CD7 by genome editing or protein retention are therefore needed, introducing complexity to the manufacturing process.18,35 An initial study has been published. This used allogeneic donor-derived CAR-T cells, limiting use to patients pre/post allo-HSCT.38 Of 20 reported patients, 18 (90%) attained complete response at 30 days. Seven of 19 responders (37%) then received allo-HSCT. Nine of 12 patients not undergoing transplant remained in remission, with a median follow-up of 6.3 months. Depletion of normal T and NK cells was observed, and some patients experienced opportunistic infections/viral reactivations. Unexpectedly, most patients had recovery of CD7– peripheral T and NK cells, although in markedly reduced numbers.

Another clinically tested target is CD5, expressed on >70% of r/r T-ALL but also on all normal T cells. Preclinical data showed that anti-CD5 CAR T cells showed relative sparing of normal T cells, and thus knock-out of CD5 might not be needed.34 However, early clinical data revealed no responses in patients with T-ALL,39 perhaps due to reported exhaustion from chronic self-stimulation.34

Here, we identified CCR9 as another potential CAR target in T-ALL, which is not expressed on most normal T cells; thus, T cell fratricide and T cell aplasia are unlikely to be risks of this strategy. However, other potential on-target off-tumor risks must be considered. In mature tissues, CCR9 is expressed mainly on gut-resident immune cells, including gut-homing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells,40 γ-δ T cells,41 plasmacytoid dendritic cells,42 immunoglobulin A plasmablasts and plasma cells,43 and intraepithelial lymphocytes.44 It is important to note that CCR9 is not, however, expressed on gut epithelium. Its only known ligand is CCL25, which is constitutively expressed in thymic and intestinal epithelial cells, and is overexpressed in the intestine during gut inflammation and autoimmunity.20 CCL25/CCR9 interactions play a role in infiltration of effector T cells to the small intestinal mucosa and are also involved in thymic T cell migration and maturation,45 with maximal CCR9 expression found on double-positive thymocytes.46

Human and murine CCR9 share similar function, expression patterns, and 86% sequence homology, and evidence from murine models may therefore be instructive. Ccr9−/− mice display normal T-cell development and, although diminished numbers of γδ intraepithelial lymphocytes are present in the small intestine, this observation is not associated with any adverse phenotype,19,41 probably due to some functional redundancy with other receptors, including CD103 and CCR7.45 Some clinical data also suggest that CCR9 may be safely targeted in humans. The CCL25/CCR9 axis has been implicated in the pathology of inflammatory bowel disease,47,48 leading to clinical trials of a small-molecule inhibitor of CCR9 in Crohn’s disease. Although these trials did not report efficacy, anti-CCR9 therapy was not associated with significant toxicity, in the gut or elsewhere.48,49 Indeed, gut-resident T cells are also CD7+, and no early gut toxicity has been seen in initial studies of anti-CD7 CAR-T, despite presumed targeting of these cells.38 Furthermore, although CCR9-directed immunotherapies may lead to thymic ablation, a meta-analysis of children who have undergone total thymectomy during cardiothoracic procedures found no evidence of clinical immunocompromise, increased risk of cancer, or autoimmunity.50

Whether CCR9 has a role in the pathophysiology of T-ALL or simply reflects expression by the underlying normal thymocyte counterparts of T-ALL blasts is unknown. CCR9 is a downstream target of NOTCH1,51 which is physiologically expressed in normal thymocytes but affected by oncogenic activating mutations in ∼60% of cases of T-ALL,52 potentially explaining the higher rate of NOTCH1 mutations identified in the CCR9+ cohort (supplemental Figure 1). In our data set, CCR9 expression was enriched in patients with r/r disease, suggesting that CCR9 may identify patients with worse prognosis. Previous reports described that CCR9 expression in T-ALL may confer a proliferative phenotype51 and resistance to apoptosis.53 Furthermore, some T-ALL cell lines or primary blasts can signal through CCR9, demonstrating CCL25-mediated chemotaxis. However, no clear evidence shows that the CCL25/CCR9 axis is required for disease initiation or progression.51,54 Indeed, in our study, CRISPR/Cas9–mediated knockout of CCR9 from the P12-Ichikawa and PF382 cell lines did not reduce blast survival or growth, indicating CCR9 signaling is not likely a requirement for survival in vitro. Of note, no CCR9 loss was seen in the cell line or PDX models used in this study, despite prolonged selection pressure, suggesting that neither de novo antigen downregulation nor selection of a preexisting CCR9– clone occurred. This is important as in patients with B-ALL treated with anti-CD19 CAR-T,55 CD19 downregulation is an important cause of relapse. Ultimately, clinical testing will be required to determine if CCR9 antigen loss is seen in patients with T-ALL treated with CARCCR9.

In our analysis, we found relatively low expression of CCR9 on primary T-ALL compared with that reported for other CAR targets in ALL. CCR9 median surface density was 1732 molecules per cell on T-ALL blasts, compared with ∼10 000 for CD19 and ∼14 000 for CD22 on B-ALL.56 Antigen-low escape was recently seen in a trial of anti-CD19/22 CAR-T in B-ALL and diffuse large B cell lymphoma: in this study, “low” density was defined as <3000 molecules per cell.57 Despite low target density, we found that anti-CCR9 CAR T cells displayed potent cytokine secretion and cytotoxicity against both cell line and primary T-ALL targets. Indeed, in coculture with the SupT1-CD19 cell line, which natively expresses CCR9 at only ∼450 molecules per cell, and transgenically expresses CD19 at 80 000 molecules per cell, production of interferon-γ and interleukin-2 was similar between anti-CCR9 and anti-CD19 CAR T cells. In addition, no evidence of antigen-low escape was seen in multiple PDX models with very low CCR9 density, including one model extending >100 days. Indeed, only in a highly aggressive PDX model with extremely low antigen density (352 molecules per cell) was initial clearance followed by tumor escape seen. Precedent for targeting of a low-density molecule comes from the clinical success of CAR-T targeting B-cell maturation antigen in myeloma,58,59 which is expressed at a median density of only 1061 molecules per cell.60

In conclusion, we have shown that CCR9 is a viable potential CAR-T target for r/r T-ALL. Clinical exploration of anti-CCR9 CAR-T for T-ALL is warranted, and a phase 1 clinical trial of anti-CCR9 CAR-T is planned. CAR-T cells against CCR9 and other targets may potentially bring the potent therapeutic potential of cellular immunotherapy to this neglected disease area.

Acknowledgments

Primary childhood leukemia samples used in this study were provided by the Blood Cancer UK Childhood Leukaemia Cell Bank. Additional samples were obtained from University College London Hospital leukemia biobank and from Papa Giovanni XXIII hospital leukemia biobank.

This work was supported by Children with Cancer and Carol’s Smile Charities. M.R.M. is funded by Great Ormond Street Hospital Children’s Charity and Blood Cancer UK. D.O., P.M.M., N.C.M., and S.D. are funded by Cancer Research UK. L.L. and A.B. are funded by the UK Medical Research Council. M.A.P. is funded by the UCL/University College London Hospital Biomedical Research Centre. O.W. is funded by Children with Cancer UK (17-249) and the UK Medical Research Council (MR/S021000/1).

This work was undertaken at University College London, which receives funding from the Department of Health’s National Institutes of Health Research Biomedical Research Centre.

Authorship

Contribution: P.M.M. designed, led, and performed the in vitro and in vivo experiments, analyzed the data, prepared the figures, and wrote the manuscript; P.A.W. led on hybridoma screening, antibody and CAR subcloning, and designed and performed in vitro and in vivo experiments; N.C.M., A.B., and D.O. sourced T-ALL samples and performed and analyzed flow cytometry data on primary samples; S.D. and M.H. assisted with in vitro/in vivo data collection; T.K. performed enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, molecular cloning, and coculture experiments; T.L. and T.R.-D. generated and maintained the CCR9– and Fluc+ cell lines used in the experiments, and assisted in hybridoma screening; S. Rahman and R.P. assessed CCR9 expression on thymic subsets by quantitative PCR; D.C.Y., S. Ross, and T.C. supplied sorted thymic subset cells; G.G. supplied the primary T-ALL samples; O.W. provided T-ALL PDX samples; L.L. provided support for the experiments, and animal work was performed on a Home Office license held by L.L.; M.A.P. supported the experiments and wrote the manuscript; and M.R.M. conceived the study, obtained funding, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: P.M.M. and L.L. own stock and received research funding from Autolus Ltd. M.A.P. is employed by and owns stock in Autolus Ltd. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Paul M. Maciocia, Department of Haematology, Cancer Institute, University College London, 72 Huntley St, London WC1E 6DD, United Kingdom; e-mail: p.maciocia@ucl.ac.uk.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

![CCR9 is expressed on T-ALL blasts with limited expression on normal peripheral blood cells. (A) Heatmap showing genes that are solely expressed in MOLT-4 T-ALL cells (red) compared with 35 normal tissue (blue; n = 172 samples) using subtractive transcriptomics from data from the Human Protein Atlas.23(B-C) CCR9 gene expression as determined by RNA-sequencing from pediatric patients with T-ALL from St. Jude’s Hospital (Memphis, TN).24 Pie chart (B) shows distribution of patients considered CCR9+ (fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped fragments [FPKM] >2.0), while scatter chart (C) shows CCR9 expression according to genetic subgroup. (D) Expression of CCR9 on 102 cases of primary T-ALL, proportion of positive blasts. (E) CCR9 antigen density of positive samples, antibodies bound per cell. (F) Expression of CCR9 on peripheral leucocytes in healthy donors. Mono, monocytes; mRNA, messenger RNA; NK, natural killer cells; RPKM, reads per kilobase of transcript per million reads mapped; TCM, T central memory; TEM, T effector memory; TEMRA, terminally differentiated effector memory; TSCM, T stem cell memory; UNK, unknown.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/140/1/10.1182_blood.2021013648/2/m_bloodbld2021013648f1.png?Expires=1765907728&Signature=cz7yR7F1PiHMvOSYbFqfpsOotRIcDTdhoCRa9rbGa17KWnsTq8mTKOGHjzmK3bz~KDjcCFRpxTP0vCa6h9vga-iofS8ZgLkPv36xpdnBBneLG0l9FYcv~uDdEz3tOiwsnQ1EcFe0V7WQ2-8-p4bPK4gqzc-a35mSqqlYoT406ZIRk4m9FyrD~L1UOrIHogodssrBHcWXQnqytK6cFa7vcgFjLB0xyaIYikrJ9N3H6vf~4yzAmA7s1zvXv~t5BxhQqrZDWBv8emFOsDixj5YbaYUxwTTCAOZSEClSVDY9z8d0mCnBKXcmR6AJXp9yj45pFMT~Slyf43m-3BgGN7Cx2Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![CCR9 is expressed on T-ALL blasts with limited expression on normal peripheral blood cells. (A) Heatmap showing genes that are solely expressed in MOLT-4 T-ALL cells (red) compared with 35 normal tissue (blue; n = 172 samples) using subtractive transcriptomics from data from the Human Protein Atlas.23(B-C) CCR9 gene expression as determined by RNA-sequencing from pediatric patients with T-ALL from St. Jude’s Hospital (Memphis, TN).24 Pie chart (B) shows distribution of patients considered CCR9+ (fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped fragments [FPKM] >2.0), while scatter chart (C) shows CCR9 expression according to genetic subgroup. (D) Expression of CCR9 on 102 cases of primary T-ALL, proportion of positive blasts. (E) CCR9 antigen density of positive samples, antibodies bound per cell. (F) Expression of CCR9 on peripheral leucocytes in healthy donors. Mono, monocytes; mRNA, messenger RNA; NK, natural killer cells; RPKM, reads per kilobase of transcript per million reads mapped; TCM, T central memory; TEM, T effector memory; TEMRA, terminally differentiated effector memory; TSCM, T stem cell memory; UNK, unknown.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/140/1/10.1182_blood.2021013648/2/m_bloodbld2021013648f1.png?Expires=1765938266&Signature=Ax1GTfgBSP1NU5GWUp31oxJ72uzdI94OA9l4VCMa73umXHUyMpQvoO8kzCVHd79lZbFR2kRFOsfviuzZJz2B~Zz02w32T4~BsiX59RJAFv56VU8D1vOkSmyNQ9yP6Tzvcd52UwElqXgiRloD60vso~aMy9I~d4KPuTCvDH1jLX52IKNejdrl8S4BtyXo5iIOhm5PlZyWmWScVnr-UGJQ2uUduWI5qzrMnV0WS-1ZkmobBCsKYls0diHvdCsKbEDWuZTb3CHod65jj3CN1n8cwnp9WIk0zQkWNy37XhMr4B-~HyiqiWGMk7tCQfTN6wdImvUwNZEpqqYGQtiVanqwEg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)