In this issue of Blood, Joseph et al report that sperm counts and quality were similar in males with sickle cell anemia (SCA) who started hydroxyurea before puberty compared with those who had never taken the drug.1 More than 40% of men with SCA had low sperm counts in both groups, but there was no suggestion that starting hydroxyurea in early childhood increased the risk of abnormalities. The use of hydroxyurea in SCA arouses strong opinions in many doctors and patients; although some will see this article as providing important new information on safety, others may feel that it is a confirmation of what they already knew.

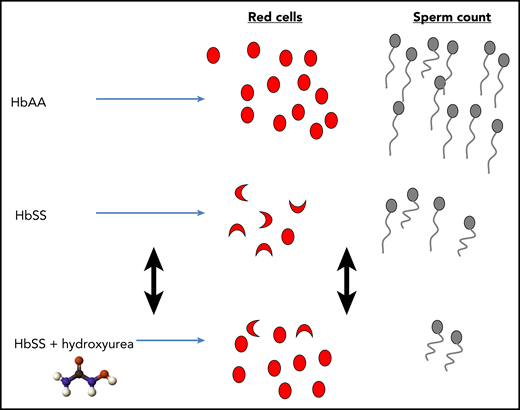

Contrasting and reversible effects of hydroxyurea on blood and sperm counts in SCA. HbAA, normal hemoglobin; HbSS, sickle cell anemia.

Contrasting and reversible effects of hydroxyurea on blood and sperm counts in SCA. HbAA, normal hemoglobin; HbSS, sickle cell anemia.

The decision about whether to take any medicine depends on balancing the likelihood of benefit against the risk of harm. Almost all studies have shown marked benefits of taking hydroxyurea in SCA, starting 25 years ago with the Muticenter Study of Hydroxyurea (MSH), which found ∼50% reductions in the rates of acute pain, acute chest syndrome, and the use of blood transfusions in adults.2 Similar benefits have been shown in children, including a reduction in the frequency of acute pain when hydroxyurea was given to infants, irrespective of the severity of the condition.3 Further studies have shown that hydroxyurea also protects against progressive cerebrovascular disease in children,4 and it has an important and wide range of benefits in some African countries, including reducing death rates in children.5 This evidence has led many experts to believe that all children with SCA should be offered hydroxyurea in the first year of life, irrespective of symptoms, as suggested in guidelines produced in the United States in 2014.6

Given this recommendation, it is perhaps surprising that relatively little is known about the safety of hydroxyurea in SCA, particularly about long-term use starting in early life. Hydroxyurea is well tolerated with remarkably few short-term side effects other than myelosuppression. However, it is a cytotoxic drug that directly inhibits DNA synthesis, which is especially relevant when treating children from infancy with a drug that they may take for many decades. This potential toxicity and the lack of long-term safety data make it difficult to completely reassure parents who are worried about starting the drug in their child and is one of the more common reasons why hydroxyurea is refused or taken unreliably.

One particular area of concern, particularly in Europe, is the effect of hydroxyurea on fertility in males (see figure). Some believe that this is not a significant issue, which is supported by the fact that many men have conceived healthy babies while taking hydroxyurea, including in the original MSH,2 and that, although sperm counts may be reduced, this does not equate to infertility. However, many studies suggest that male subfertility may be a legitimate concern, including a study of 35 men with SCA, in whom hydroxyurea caused a decrease in median sperm count from 61.6 million to 0.63 million (P < .0001).7 Although this is largely reversible on stopping hydroxyurea, there are some well-documented cases in which hydroxyurea seems to have caused a long-term reduction in sperm count, persisting for >1 year after stopping the drug.7 This raises the possibility that exposing all children with SCA to hydroxyurea from an early age could greatly increase the numbers of men with reduced fertility, with up to 10 years of exposure to hydroxyurea before the onset of puberty. This risk may be justified given the proven benefits of hydroxyurea, particularly in children with complications such as vasculopathy, and in many parts of Africa where the majority of patients die in childhood,8 and hydroxyurea significantly improves survival.5 However, the risk-benefit analysis may be different in high-income countries where the chance of dying from SCA in childhood is very small,9 and it is not entirely clear whether there is an advantage to starting hydroxyurea early in childhood as opposed to waiting until after puberty. The emergence of new drugs for the treatment of SCA also enters the equation, particularly because they are likely to have a different spectrum of side effects, which may not include reduced fertility.10

Although it is a small study, this article by Joseph et al is important, because it makes it possible to give some reassurance to parents of infant boys that there is no evidence that hydroxyurea increases the risk of infertility, and it will directly influence my clinical practice. Currently, ∼50% children with SCA at my hospital take hydroxyurea, and significant numbers of symptomatic children do not take it because of parental concerns about toxicity. These days, expert opinion6 does not convince many people to change their behavior, but it is hoped that actual evidence will be more persuasive.

Some important questions remain: do higher doses of hydroxyurea increase the chance of subfertility? Should teenagers temporarily stop hydroxyurea and bank sperm when they reach puberty? Could hydroxyurea actually help to protect gonadal function and reduce the number of men with SCA with low sperm counts? It is hoped that more long-term studies will continue to emerge and answer some of these questions. Although hydroxyurea is undoubtedly beneficial to the large majority of patients with SCA, it is important to continue to collect longitudinal data on efficacy and adverse effects, to allow the drug to be used more precisely and to minimize harm.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.