Key Points

Lenalidomide inhibits CLL proliferation in a cereblon/p21-dependent manner.

Treatment with lenalidomide induces p21 in CLL independent of p53.

Abstract

Lenalidomide has demonstrated clinical activity in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), even though it is not cytotoxic for primary CLL cells in vitro. We examined the direct effect of lenalidomide on CLL-cell proliferation induced by CD154-expressing accessory cells in media containing interleukin-4 and -10. Treatment with lenalidomide significantly inhibited CLL-cell proliferation, an effect that was associated with the p53-independent upregulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, p21WAF1/Cip1 (p21). Silencing p21 with small interfering RNA impaired the capacity of lenalidomide to inhibit CLL-cell proliferation. Silencing cereblon, a known molecular target of lenalidomide, impaired the capacity of lenalidomide to induce expression of p21, inhibit CD154-induced CLL-cell proliferation, or enhance the degradation of Ikaros family zinc finger proteins 1 and 3. We isolated CLL cells from the blood of patients before and after short-term treatment with low-dose lenalidomide (5 mg per day) and found the leukemia cells were also induced to express p21 in vivo. These results indicate that lenalidomide can directly inhibit proliferation of CLL cells in a cereblon/p21-dependent but p53-independent manner, at concentrations achievable in vivo, potentially contributing to the capacity of this drug to inhibit disease-progression in patients with CLL.

Introduction

Lenalidomide is a second-generation immunomodulatory drug (IMiD)1-3 that has both direct tumoricidal, as well as immunomodulatory activity in patients with multiple myeloma.4 This drug also has clinical activity in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), even though it is not directly cytotoxic to CLL cells in vitro.5,6 As such, its clinical activity in CLL is presumed to be secondary to its immune modulatory activity.7 Indeed, lenalidomide indirectly modulates CLL-cell survival in vitro by affecting supportive cells, such as nurse-like cells,8 found in the microenvironment of lymphoid tissues. Lenalidomide also can enhance T-cell proliferation1 and interferon-γ production9 in response to CD3-crosslinking in vitro and dendritic-cell–mediated activation of T cells.10 Moreover, lenalidomide can reverse noted functional defects of T cells in patients with CLL.11,12 Finally, lenalidomide can also induce CLL B cells to express higher levels of immunostimulatory molecules such as CD80, CD86, HLA-DR, CD95, and CD40 in vitro,5,13 thereby potentially enhancing their capacity to engage T cells in cognate interactions that lead to immune activation in response to leukemia-associated antigen(s).14

However, lenalidomide may also have direct antiproliferative effects on CLL cells that account in part for its clinical activity in patients with this disease. This drug can inhibit proliferation of B-cell lymphoma lines15 and induce growth arrest and apoptosis of mantle-cell lymphoma cells.16 Although originally considered an accumulative disease of resting G0/1 lymphocytes, CLL increasingly is being recognized as a lymphoproliferative disease that can have high rates of leukemia-cell turnover, resulting from robust leukemia cell proliferation that is offset by concomitant cell death. Indeed, CLL cells can undergo robust growth in so-called “proliferation centers” within lymphoid tissues, in response to signals received from accessory cells within the leukemia microenvironment. In vivo heavy-water labeling studies have demonstrated that some patients can have relatively high rates of leukemia-cell turnover, generating as much as 1% of their total leukemia-cell population each day, presumably in such tissue compartments.17 Inhibition of leukemia-cell proliferation could offset the balance between CLL-cell proliferation and cell death, resulting in reduction in tumor burden over time. Herein, we examined whether lenalidomide could inhibit the growth of CLL cells that are induced to proliferate, an effect that potentially could contribute to its noted clinical activity in patients with this disease.

Methods

Reagents

Lenalidomide was provided by Celgene Corporation (San Diego, CA) and solubilized in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), which was used as a vehicle control in all experiments. Between 0.01 and 30 μM of lenalidomide was added every 3 days to long-term cultures, unless otherwise indicated.

CLL cell samples

Blood samples were collected from CLL patients at the University of California San Diego Moores Cancer Center who satisfied diagnostic and immunophenotypic criteria for common B-cell CLL, and who provided written, informed consent, in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki18 and the Institutional Review Board of the University of California San Diego. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by density centrifugation with Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden), resuspended in 90% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Omega Scientific, Tarzana, CA) and 10% DMSO for viable storage in liquid nitrogen. Alternatively, viably frozen CLL cells were purchased from AllCells (Emeryville, CA) or Conversant Biologics (Huntsville, AL). Samples with >95% CD19+CD5+ CLL cells were used without further purification throughout this study.

Coculture of CLL cells with HeLaCD154, fibroblastsCD154, or CpG stimulation

HeLa cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). CD154-expressing HeLa cells (HeLaCD154) were generated as described.19 FibroblastsCD154 were provided by Dr Ralph Steinman.20 For experiments using HeLaCD154 cells, CLL cells were plated at 1.5 × 106 cells per well (per mL) in a 24-well tray on a layer of irradiated HeLaCD154 (8000 Rad) cells at a CLL:HeLaCD154 cell ratio of 15:1 in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 10 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), penicillin (100 U/mL)-streptomycin (100 µg/mL) (Life Technologies), 5 ng/mL of recombinant human interleukin (IL)-4 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and 15 ng/mL recombinant human IL-10 (PeproTech Inc, Rocky Hill, NJ). In earlier studies, we noted that expression of CD154 on the supportive cells, combined with exogenous IL-4 and IL-10, provided for optimal CLL-cell proliferation (see supplemental Figure 1A-B on the Blood Web site). These cells were also stained with fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies specific for CD19, CD5, or ROR1 to confirm via flow cytometry that the proliferating cells were CLL cells (supplemental Figure 1C). For coculture on FibroblastsCD154, 0.8 to 1 × 106 CLL cells were plated on 6 × 105 cells/well mitomycin-C–treated fibroblasts (10 µg/mL; 3 hours) in 1 mL per well in the media described above. For long-term cultures, half of the media was renewed every 3 days. For CpG stimulation, CLL cells were plated at 1.5 × 106 cell/mL in RPMI-1640 supplemented with FCS, N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, penicillin, and streptomycin as above, to which we added 2.5 µg/mL CpG (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA), 10 ng/mL rhIL-2, and 15 ng/mL rhIL-10 (both from PeproTech Inc).

Descriptions of CLL-cell proliferation and viability measurements, flow cytometry, cell-cycle analysis, gene expression and TP53-mutation analysis, transfection, immunoblot and statistical analysis are provided in the supplemental “Methods.”

Results

Lenalidomide inhibits CLL-cell proliferation

We induced CLL cells to undergo proliferation by coculturing them with accessory cells made to express CD154 in the presence of exogenous IL-4 and IL-10. CLL cells cocultured with CD154-expressing HeLa cells (Figure 1A-B) or human fibroblasts (Figure 1C-D) were induced to proliferate, as detected by the reduction in green fluorescence of dividing cells labeled with carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE). Moreover, the CD154-expressing cell lines supported CLL-cell proliferation through several rounds of division, as shown by the dilution of CFSE fluorescence over time (Figure 1A-D). Induction of CLL-cell proliferation was associated with changes in the distribution of cells in the different phases of the cell cycle, decreasing the numbers of cells in G0/G1 and concomitantly increasing the numbers of cells in S or G2/M phases of the cell cycle, without affecting the fraction of cells in sub-G1 (Figure 1E-H). Consistent with the induced cellular proliferation, we noted increased numbers of viable CLL cells over time in cultures with exogenous cytokines and CD154-expressing cells, but not in control cultures exposed to supportive cells not expressing CD154 (Figure 1I).

CLL cells cocultured with CD154-expressing supportive cells are induced to proliferate. (A-B) CLL cells were labeled with CFSE and cocultured on HeLaCD154 in the presence of IL-4 and IL-10, as described in “Methods.” Cells were collected on days 2, 3, 6, and 10 for analysis by flow cytometry. The results of assays on 2 representative CLL samples are shown in (A) and the fraction of dividing cells observed in 6 patient samples tested is presented in (B). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s multiple comparison test were used to determine statistically significant differences from day 2. ***P < .001 (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]; n = 6). (C-D) CLL cells were labeled with CFSE and cocultured on FibroblastsCD154 in the presence of IL-4 and IL-10, as described in “Methods.” Cells were collected on days 1, 6, and 9 for analysis by flow cytometry. One representative CLL sample out of 4 is shown in (C) and the fraction of dividing cells observed in all 4 patients tested is presented in (D). One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test were used to determine statistically significant differences from day 1. ***P < .001 (mean ± SEM; n = 4). (E-F) CLL cells were cocultured on FibroblastsCD154 in the presence of IL-4 and IL-10, and at the indicated time, subjected to cell-cycle analysis following PI staining. One representative CLL sample out of 4 is shown in (E) and the fraction of cells in each phase for all 4 patients tested is presented in (F). **P < .01; ***P < .001 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 4). (G-H) CLL cells were cocultured on FibroblastsCD154 in the presence of IL-4 and IL-10, and at the indicated time, subjected to 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation for a period of 4 hours, as described in “Methods.” One representative CLL sample out of 4 is shown in (G) and the fraction of EdU+ cells observed in all 4 patients tested is presented in (H). **P < .01 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 4). (I) CLL cells from 3 different patients were cocultured on HeLa CD154 or nontransfected HeLa cells in the presence of IL-4 and IL-10. At the indicated days, live CLL-cell counts were assessed by flow cytometry, as described in “Methods,” and are presented as expansion folds relative to day 1. *P < .05 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 3).

CLL cells cocultured with CD154-expressing supportive cells are induced to proliferate. (A-B) CLL cells were labeled with CFSE and cocultured on HeLaCD154 in the presence of IL-4 and IL-10, as described in “Methods.” Cells were collected on days 2, 3, 6, and 10 for analysis by flow cytometry. The results of assays on 2 representative CLL samples are shown in (A) and the fraction of dividing cells observed in 6 patient samples tested is presented in (B). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s multiple comparison test were used to determine statistically significant differences from day 2. ***P < .001 (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]; n = 6). (C-D) CLL cells were labeled with CFSE and cocultured on FibroblastsCD154 in the presence of IL-4 and IL-10, as described in “Methods.” Cells were collected on days 1, 6, and 9 for analysis by flow cytometry. One representative CLL sample out of 4 is shown in (C) and the fraction of dividing cells observed in all 4 patients tested is presented in (D). One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test were used to determine statistically significant differences from day 1. ***P < .001 (mean ± SEM; n = 4). (E-F) CLL cells were cocultured on FibroblastsCD154 in the presence of IL-4 and IL-10, and at the indicated time, subjected to cell-cycle analysis following PI staining. One representative CLL sample out of 4 is shown in (E) and the fraction of cells in each phase for all 4 patients tested is presented in (F). **P < .01; ***P < .001 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 4). (G-H) CLL cells were cocultured on FibroblastsCD154 in the presence of IL-4 and IL-10, and at the indicated time, subjected to 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation for a period of 4 hours, as described in “Methods.” One representative CLL sample out of 4 is shown in (G) and the fraction of EdU+ cells observed in all 4 patients tested is presented in (H). **P < .01 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 4). (I) CLL cells from 3 different patients were cocultured on HeLa CD154 or nontransfected HeLa cells in the presence of IL-4 and IL-10. At the indicated days, live CLL-cell counts were assessed by flow cytometry, as described in “Methods,” and are presented as expansion folds relative to day 1. *P < .05 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 3).

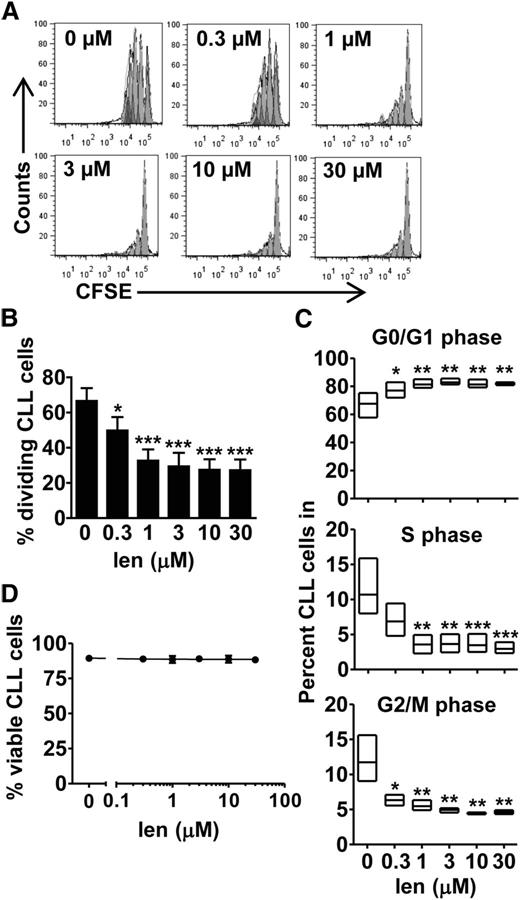

The capacity to induce CLL-cell proliferation allowed us to examine the impact of lenalidomide on dividing CLL cells in vitro. First, CLL cells were cocultured on CD154-expressing accessory cells in media containing IL-4 and IL-10 for 2 days. Subsequent to this, we added lenalidomide to the concentrations listed and cultured the cells for 7 days. We observed a dose-dependent inhibition of CLL-cell proliferation with lenalidomide (Figure 2A), which led to a significant decrease in the fraction of dividing CLL cells, starting at concentrations as low as 0.3 µM (Figure 2B). The inhibition of proliferation was confirmed by cell-cycle analysis using propidium iodide (PI) staining (Figure 2C). The fraction of cells in the G0/G1 phases of the cell cycle were significantly elevated in a dose-dependent fashion with increasing amounts of lenalidomide. The increases in the fraction of cells in the G0/G1 phase were accompanied by a significant decrease in the fraction of cells in the S or G2/M phase in cells treated with lenalidomide, relative to cultures without the added drug. We also observed comparable cytostatic effects, measured via CFSE labeling, viable cell counts, 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine incorporation, or cell-cycle analysis, when lenalidomide was added at the initiation of the cocultures at drug concentrations ≥3 µM (supplemental Figure 2A-F). Using this regimen, we observed that lenalidomide could inhibit the induced proliferation of CLL cells of almost all patients examined (19 of 22), significantly inhibiting the induced increase in numbers of CLL cells noted after 6 days in coculture (supplemental Figure 2G). There were no distinctive characteristics that were shared by the 3 nonresponsive samples. On the other hand, we did not observe direct cytotoxic effects of lenalidomide on the proliferating CLL cells, as noted in other studies on resting cells,5,6 even when the drug was added to the CLL cells at the initiation of coculture (supplemental Figure 2H) or after 2 days of coculture (Figure 2D). Of note, the level of CD154 expressed on accessory cells was not altered by treatment with lenalidomide (supplemental Figure 3A-B), suggesting that the effect of the drug was not due to an indirect effect on the accessory cells used to induce CLL-cell proliferation. Finally, lenalidomide also inhibited CLL-cell proliferation induced by coculture with accessory cells expressing CD154, in the absence of IL-4 and IL-10, suggesting that the inhibitory effects of lenalidomide on CLL-cell proliferation is not mediated through inhibition of the signaling induced by cytokines, such as IL-4 and/or IL-10 (supplemental Figure 3C). Consistent with this notion, lenalidomide also displayed a cytostatic effect on CLL cells stimulated to divide following treatment with CpG oligonucleotides in the presence of IL-2 and IL-10 (supplemental Figure 4), suggesting that the inhibition of proliferation was not restricted to inhibition of CD40-signaling.

Lenalidomide inhibits CLL-cell proliferation. (A-B) CFSE-labeled CLL cells from 3 different patients were cocultured with FibroblastsCD154 and IL-4/IL-10 for 48 hours and exposed to increasing single doses of lenalidomide or DMSO as vehicle control for 7 days, at which point, the cells were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry for proliferation. (A) CFSE profiles are presented for cells of a representative patient. (B) The fraction of dividing CLL cells present with increasing doses of lenalidomide were determined using FlowJo software, by establishing the nondividing cells based on unstimulated, CFSE-labeled CLL cells. Data from 3 patients are presented. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test were used to determine statistically significant differences from day 1. *P < .05; ***P < .001 (mean ± SEM; n = 3). (C) CLL cells from 3 different patients were stimulated with IL-4/IL-10 in the presence of FibroblastsCD154 and exposed to increasing doses of lenalidomide or DMSO as control. Cell-cycle analysis was performed by flow cytometry after 6 days using PI staining, as described in “Methods.” Percentage of cells in G0/G1, S, or G2/M were assessed using the cell-cycle analysis tool from FlowJo software and are presented as boxes indicating the median, minimum, and maximum values of cell proportions in each phase of the cell cycle. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test were used to determine statistically significant differences from control. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 (mean ± SEM; n = 3). (D) CLL cells from 3 patient samples were cocultured on FibroblastsCD154 in the presence of IL-4 and IL-10, and increasing doses of lenalidomide from day 2 of coculture. The fraction of viable CLL cells were measured after 7 days of treatment by flow cytometry using 7-AAD. Live cells were identified as 7-AAD–negative cells (mean ± SEM; n = 3).

Lenalidomide inhibits CLL-cell proliferation. (A-B) CFSE-labeled CLL cells from 3 different patients were cocultured with FibroblastsCD154 and IL-4/IL-10 for 48 hours and exposed to increasing single doses of lenalidomide or DMSO as vehicle control for 7 days, at which point, the cells were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry for proliferation. (A) CFSE profiles are presented for cells of a representative patient. (B) The fraction of dividing CLL cells present with increasing doses of lenalidomide were determined using FlowJo software, by establishing the nondividing cells based on unstimulated, CFSE-labeled CLL cells. Data from 3 patients are presented. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test were used to determine statistically significant differences from day 1. *P < .05; ***P < .001 (mean ± SEM; n = 3). (C) CLL cells from 3 different patients were stimulated with IL-4/IL-10 in the presence of FibroblastsCD154 and exposed to increasing doses of lenalidomide or DMSO as control. Cell-cycle analysis was performed by flow cytometry after 6 days using PI staining, as described in “Methods.” Percentage of cells in G0/G1, S, or G2/M were assessed using the cell-cycle analysis tool from FlowJo software and are presented as boxes indicating the median, minimum, and maximum values of cell proportions in each phase of the cell cycle. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test were used to determine statistically significant differences from control. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 (mean ± SEM; n = 3). (D) CLL cells from 3 patient samples were cocultured on FibroblastsCD154 in the presence of IL-4 and IL-10, and increasing doses of lenalidomide from day 2 of coculture. The fraction of viable CLL cells were measured after 7 days of treatment by flow cytometry using 7-AAD. Live cells were identified as 7-AAD–negative cells (mean ± SEM; n = 3).

p21WAF1/Cip1 (p21) is necessary for lenalidomide-induced inhibition of CLL-cell proliferation

We observed that CLL cells exposed to lenalidomide accumulate in the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle when stimulated with CD154 and IL-4/IL-10. Prior studies on the B-cell line Namalwa showed that lenalidomide could upregulate the expression of p21,15 a protein that could inhibit the activity of cyclin-dependent kinases involved in G1/S progression.21,22 We, therefore, monitored the expression levels of p21 in CLL cells stimulated to divide and exposed to lenalidomide. We observed an upregulation of p21 messenger RNA levels after 24 hours of exposure to lenalidomide (Figure 3A). A dose-dependent increase of p21 protein was also observed, regardless of whether there was a detectable expression of p53 (Figure 3B-C), suggesting that p21 may be upregulated via a p53-independent mechanism. To test this hypothesis, we measured the effect of lenalidomide on CLL cells lacking functional p53, of which 99.5% had del(17p) on one allele and an inactivating mutation in exon 5 (at protein codon 174 [R→W]) in the retained allele. In contrast to CLL cells with wild-type p53, we observed that these CLL cells could not be induced to express higher levels of p53 or p21 following exposure to γ-irradiation (Figure 3D). However, such CLL cells could be induced to express p21 by treatment with lenalidomide, indicating that lenalidomide-induced upregulation of p21 in CLL cells does not require functional p53.

Lenalidomide upregulates p21 in CLL cells. (A) CLL cells from 4 patient samples were cocultured with FibroblastsCD154 and IL-4/IL-10, and exposed to 10 µM lenalidomide or the equivalent volume of DMSO. After 24 hours, the cells were collected and analyzed for the expression levels of p21 messenger RNA (mRNA) by QuantiGene. The expression of hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyltransferase was monitored as housekeeping gene and used to normalize p21 expression level for each sample. *P < .05 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 4). (B-C) CLL cells were cocultured with HeLaCD154 and IL-4/IL-10 and exposed to increasing amounts of lenalidomide or vehicle control. In parallel, HeLaCD154 alone were cultured with increasing doses of lenalidomide as a control. After 24 hours, the cells were collected and protein extracted for the analysis of p21, p53, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression by immunoblot. In (B), the results from 3 CLL samples are shown, along with the HeLaCD154 control, for which the same amount of total protein as the CLL cells was run. In (C), the densitometry analysis of p21 and p53 expression is presented for all 3 patients from (B). The intensity of the target proteins were normalized to GAPDH levels. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test were used to determine statistically significant differences from control. *P < .05; ***P < .001 (mean ± SEM; n = 3). (D) CLL cells from a sample deficient in functional p53 (p53 def) and from a sample with functional p53 (p53 WT) were exposed to either γ-irradiation (1 Gy) or 3 µM lenalidomide followed by 8 hours incubation, at which point the cells were collected for protein extraction and detection of p21, p53, and GAPDH by immunoblot. (E-F) CLL cells from 16 patients were cocultured with HeLaCD154 and IL-4/IL-10 and exposed to 3 µM lenalidomide or DMSO. After 3 days, the cells were collected, lysed, and analyzed for p21 and GAPDH expression by immunoblot. (E) Shows the immunoblot results, while (F) presents the densitometry analysis quantifying the expression levels of p21 protein for all patients presented in (E). The expression levels of p21 have been normalized to GAPDH. ***P < .001 (Student t test). (G) CLL cells were cocultured with HeLaCD154 and IL-4/IL-10 and exposed to 3 µM lenalidomide or an equivalent volume of DMSO. At day 3, a fraction of the cells were collected, lysed, and analyzed for the expression of p21 and GAPDH by immunoblot, as described above. At day 6, viable cell counts were performed by flow cytometry as described in “Methods.” The percent decrease in proliferation for each patient measured at day 6 (100 × [expansion foldCTRL-treated samples − expansion foldlenalidomide-treated samples] / expansion foldCTRL-treated samples) is presented in function of the percent increase in p21 protein expression measured by densitometry analysis as above (100 × [p21CTRL-treated samples – p21lenalidomide-treated samples] / p21CTRL-treated samples). Each dot represents data from 1 CLL patient (n = 22; Pearson r = 0.52).

Lenalidomide upregulates p21 in CLL cells. (A) CLL cells from 4 patient samples were cocultured with FibroblastsCD154 and IL-4/IL-10, and exposed to 10 µM lenalidomide or the equivalent volume of DMSO. After 24 hours, the cells were collected and analyzed for the expression levels of p21 messenger RNA (mRNA) by QuantiGene. The expression of hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyltransferase was monitored as housekeeping gene and used to normalize p21 expression level for each sample. *P < .05 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 4). (B-C) CLL cells were cocultured with HeLaCD154 and IL-4/IL-10 and exposed to increasing amounts of lenalidomide or vehicle control. In parallel, HeLaCD154 alone were cultured with increasing doses of lenalidomide as a control. After 24 hours, the cells were collected and protein extracted for the analysis of p21, p53, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression by immunoblot. In (B), the results from 3 CLL samples are shown, along with the HeLaCD154 control, for which the same amount of total protein as the CLL cells was run. In (C), the densitometry analysis of p21 and p53 expression is presented for all 3 patients from (B). The intensity of the target proteins were normalized to GAPDH levels. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test were used to determine statistically significant differences from control. *P < .05; ***P < .001 (mean ± SEM; n = 3). (D) CLL cells from a sample deficient in functional p53 (p53 def) and from a sample with functional p53 (p53 WT) were exposed to either γ-irradiation (1 Gy) or 3 µM lenalidomide followed by 8 hours incubation, at which point the cells were collected for protein extraction and detection of p21, p53, and GAPDH by immunoblot. (E-F) CLL cells from 16 patients were cocultured with HeLaCD154 and IL-4/IL-10 and exposed to 3 µM lenalidomide or DMSO. After 3 days, the cells were collected, lysed, and analyzed for p21 and GAPDH expression by immunoblot. (E) Shows the immunoblot results, while (F) presents the densitometry analysis quantifying the expression levels of p21 protein for all patients presented in (E). The expression levels of p21 have been normalized to GAPDH. ***P < .001 (Student t test). (G) CLL cells were cocultured with HeLaCD154 and IL-4/IL-10 and exposed to 3 µM lenalidomide or an equivalent volume of DMSO. At day 3, a fraction of the cells were collected, lysed, and analyzed for the expression of p21 and GAPDH by immunoblot, as described above. At day 6, viable cell counts were performed by flow cytometry as described in “Methods.” The percent decrease in proliferation for each patient measured at day 6 (100 × [expansion foldCTRL-treated samples − expansion foldlenalidomide-treated samples] / expansion foldCTRL-treated samples) is presented in function of the percent increase in p21 protein expression measured by densitometry analysis as above (100 × [p21CTRL-treated samples – p21lenalidomide-treated samples] / p21CTRL-treated samples). Each dot represents data from 1 CLL patient (n = 22; Pearson r = 0.52).

Next, we monitored the expression levels of p21 in a larger group of patient samples after treatment with 3 µM lenalidomide. We observed that lenalidomide induced upregulation of p21 in most samples tested (13 of 16) (Figure 3E-F). Of note, the 3 samples that failed to upregulate p21 expression were induced to proliferate in the coculture system, but were not sensitive to the inhibition mediated by 3 µM lenalidomide (2.6 ± 0.7 vs 2.4 ± 0.7-fold expansion from day 1 to day 6 in control-treated cells vs lenalidomide-treated cells, respectively). Furthermore, we observed that p21 was upregulated in a fashion that correlated with the inhibition of proliferation induced by lenalidomide (Figure 3G), suggesting that p21 is involved in the growth inhibitory effects of lenalidomide.

We used small interfering RNA (siRNA) technology to silence p21 in primary CLL cells and monitored the activity of lenalidomide on the transfected cells stimulated to divide by coculture with CD154-expressing cells and exogenous cytokines. We observed reduced expression of p21 following silencing (Figure 4A-B). Upon exposure to lenalidomide, the p21-silenced cells still showed an increase in p21 protein, but its levels were reduced compared with that of control-treated cells (Figure 4C-D). CLL cells transfected with siRNA specific for p21 were significantly less sensitive to the growth inhibitory effects of lenalidomide than CLL cells transfected with control siRNA (Figure 4E-F). These results indicate that expression of p21 contributes to the cytostatic activity of lenalidomide on CLL cells.

p21 silencing in CLL cells interferes with the antiproliferative activity of lenalidomide. (A-B) siRNAs specific for p21 or nonspecific siRNA control (CTRL) were transfected into CLL cells using HiPerFect reagent as described in “Methods,” and cocultured on HeLaCD154 and IL-4/IL-10. After 48 hours, the cells were collected and lysed for detection of p21 and GAPDH protein by immunoblot. In (A), data from 2 representative patients are presented, and in (B) densitometry analysis quantifying the levels of p21 protein in 5 different CLL samples is shown. The expression of p21 has been normalized to GAPDH. **P < .01 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 5). (C-D) CLL cells from 4 patient samples were transfected as in (A) with either CTRL siRNA or p21 siRNA, and cocultured on HeLaCD154 and IL-4/IL-10 in the presence of 3 µM lenalidomide or control media. After 48 hours, the cells were collected and lysed for detection of p21 and GAPDH protein by immunoblot. In (C), data from 2 representative patients are presented, and in (D) densitometry analysis quantifying the levels of p21 protein in 4 different CLL samples is shown. The expression of p21 has been normalized to GAPDH. *P < .05 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 4). (E) CLL cells from 5 patient samples were transfected as in (A) with either CTRL siRNA or p21 siRNA, and exposed to 3 µM lenalidomide or DMSO. After 72 hours, CLL-cell proliferation was measured using 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation, which provides absorbances at 450 to 690 nm. *P < .05; **P < .01 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 5). (F) Proliferation data from (E) were used to calculate the percent inhibition of proliferation induced by lenalidomide in p21-silenced cells and in CTRL cells ([AbsorbanceCTRL-treated samples – Absorbancelenalidomide-treated samples] / AbsorbanceCTRL-treated samples × 100). **P < .01 (Student t test).

p21 silencing in CLL cells interferes with the antiproliferative activity of lenalidomide. (A-B) siRNAs specific for p21 or nonspecific siRNA control (CTRL) were transfected into CLL cells using HiPerFect reagent as described in “Methods,” and cocultured on HeLaCD154 and IL-4/IL-10. After 48 hours, the cells were collected and lysed for detection of p21 and GAPDH protein by immunoblot. In (A), data from 2 representative patients are presented, and in (B) densitometry analysis quantifying the levels of p21 protein in 5 different CLL samples is shown. The expression of p21 has been normalized to GAPDH. **P < .01 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 5). (C-D) CLL cells from 4 patient samples were transfected as in (A) with either CTRL siRNA or p21 siRNA, and cocultured on HeLaCD154 and IL-4/IL-10 in the presence of 3 µM lenalidomide or control media. After 48 hours, the cells were collected and lysed for detection of p21 and GAPDH protein by immunoblot. In (C), data from 2 representative patients are presented, and in (D) densitometry analysis quantifying the levels of p21 protein in 4 different CLL samples is shown. The expression of p21 has been normalized to GAPDH. *P < .05 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 4). (E) CLL cells from 5 patient samples were transfected as in (A) with either CTRL siRNA or p21 siRNA, and exposed to 3 µM lenalidomide or DMSO. After 72 hours, CLL-cell proliferation was measured using 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation, which provides absorbances at 450 to 690 nm. *P < .05; **P < .01 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 5). (F) Proliferation data from (E) were used to calculate the percent inhibition of proliferation induced by lenalidomide in p21-silenced cells and in CTRL cells ([AbsorbanceCTRL-treated samples – Absorbancelenalidomide-treated samples] / AbsorbanceCTRL-treated samples × 100). **P < .01 (Student t test).

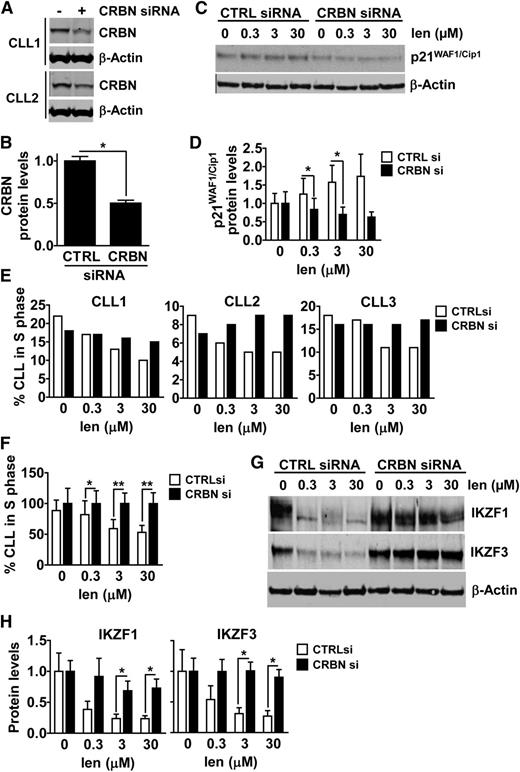

Lenalidomide mediates its cytostatic activity via a cereblon (CRBN)/p21-dependent mechanism in CLL cells

The only known direct molecular target of lenalidomide is CRBN,23 that is part of the Cul4A-DDB1 E3 ligase complex. CRBN also plays a role in the cytostatic and/or cytotoxic activity of lenalidomide in multiple myeloma cells23,24 and in the neoplastic B cells of patients with activated B-cell diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.25 To evaluate the role of CRBN in the cytostatic activity of lenalidomide on CLL cells, we used siRNA technology to silence CRBN in primary CLL cells. We observed a significant reduction of CRBN protein levels in CLL cells 48 hours after transfection with CRBN siRNA, but not with control siRNA (Figure 5A-B). CLL cells transfected with CRBN siRNA expressed substantially lower amounts of p21 following treatment with lenalidomide than CLL cells transfected with control siRNA (Figure 5C-D), indicating that CRBN contributed to the lenalidomide-induced expression of p21. Furthermore, we observed that the CRBN-silenced cells were less susceptible to the cytostatic activity of lenalidomide than control-treated CLL cells (Figure 5E-F). These results indicate that the cytostatic activity of lenalidomide involves induction of p21 in CLL cells in a CRBN-dependent manner.

CRBN silencing interferes with p21, IKZF1 and IKZF3 expression, and the antiproliferative activity of lenalidomide in CLL cells. (A-B) CLL cells were transfected with CRBN siRNA or nonspecific control siRNA (CTRL) using Amaxa, and cocultured on FibroblastsCD154 with IL-4 and IL-10 for 48 hours, at which point the cells were collected and lyzed for the analysis of CRBN protein expression and β-actin by immunoblot. Data from 2 representative patients are shown in (A) and densitometry analysis quantifying the expression levels of CRBN protein in 3 transfected CLL samples is presented in (B). The expression of CRBN has been normalized to β-actin. *P < .05 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 3). (C-D) CLL cells were transfected with CTRL siRNA or CRBN siRNA as above, and plated on FibroblastsCD154 for 48 hours, at which point increasing doses of lenalidomide were added to the cells. After 5 days of lenalidomide exposure, CLL cells were collected and lysed to monitor for p21 and β-actin protein expression by immunoblot. Data from a representative patient is shown in (C) and densitometry analysis quantifying the expression levels of p21 protein in 3 transfected CLL samples is presented in (D). The expression of p21 has been normalized to β-actin. *P < .05 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 3). (E-F) CLL cells were transfected with CTRL siRNA or CRBN siRNA, cocultured on FibroblastsCD154, and exposed to lenalidomide as above. After 5 days of lenalidomide exposure, the fraction of CLL cells in S-phase of the cell cycle was measured by EdU incorporation and flow cytometry. In (E), data from each patient sample tested are presented, while (F) shows the combined data for all 3 patients presented in (E), after being normalized to CTRL cells. *P < .05, **P < .01 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 3). (G-H) CLL cells were transfected with CTRL siRNA or CRBN siRNA, cocultured on FibroblastsCD154, and exposed to lenalidomide as above. After 24 hours of lenalidomide exposure, CLL cells were collected and lysed to monitor for IKZF1, IKZF3, and β-actin protein expression by immunoblot. Data from a representative patient is shown in (G). Densitometry analysis quantifying the expression levels of IKZF1 and IKZF3 obtained using CLL cells from 3 different patients is presented in (H). The expression of each target protein has been normalized to β-actin, and is expressed relatively to control. *P < .05 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 3).

CRBN silencing interferes with p21, IKZF1 and IKZF3 expression, and the antiproliferative activity of lenalidomide in CLL cells. (A-B) CLL cells were transfected with CRBN siRNA or nonspecific control siRNA (CTRL) using Amaxa, and cocultured on FibroblastsCD154 with IL-4 and IL-10 for 48 hours, at which point the cells were collected and lyzed for the analysis of CRBN protein expression and β-actin by immunoblot. Data from 2 representative patients are shown in (A) and densitometry analysis quantifying the expression levels of CRBN protein in 3 transfected CLL samples is presented in (B). The expression of CRBN has been normalized to β-actin. *P < .05 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 3). (C-D) CLL cells were transfected with CTRL siRNA or CRBN siRNA as above, and plated on FibroblastsCD154 for 48 hours, at which point increasing doses of lenalidomide were added to the cells. After 5 days of lenalidomide exposure, CLL cells were collected and lysed to monitor for p21 and β-actin protein expression by immunoblot. Data from a representative patient is shown in (C) and densitometry analysis quantifying the expression levels of p21 protein in 3 transfected CLL samples is presented in (D). The expression of p21 has been normalized to β-actin. *P < .05 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 3). (E-F) CLL cells were transfected with CTRL siRNA or CRBN siRNA, cocultured on FibroblastsCD154, and exposed to lenalidomide as above. After 5 days of lenalidomide exposure, the fraction of CLL cells in S-phase of the cell cycle was measured by EdU incorporation and flow cytometry. In (E), data from each patient sample tested are presented, while (F) shows the combined data for all 3 patients presented in (E), after being normalized to CTRL cells. *P < .05, **P < .01 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 3). (G-H) CLL cells were transfected with CTRL siRNA or CRBN siRNA, cocultured on FibroblastsCD154, and exposed to lenalidomide as above. After 24 hours of lenalidomide exposure, CLL cells were collected and lysed to monitor for IKZF1, IKZF3, and β-actin protein expression by immunoblot. Data from a representative patient is shown in (G). Densitometry analysis quantifying the expression levels of IKZF1 and IKZF3 obtained using CLL cells from 3 different patients is presented in (H). The expression of each target protein has been normalized to β-actin, and is expressed relatively to control. *P < .05 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 3).

Lastly, we monitored for changes in the expression of Ikaros family zinc finger proteins 1 and 3 (IKZF1 and IKZF3), transcription factors found to be degraded in a CRBN-dependent manner and required for the activity of lenalidomide on multiple myeloma cells and T cells.26-28 For this, we transfected CLL cells with either control siRNA or CRBN-specific siRNA, cocultured the transfected cells on CD154-expressing supportive cells in media without (control) or with various concentrations of lenalidomide for 24 hours, after which we prepared cell lysates which were examined via immunoblot analysis. We observed reduced expression levels of IKZF1 and IKZF3 in control CLL cells treated with lenalidomide at concentrations as low as 0.3 µM (Figure 5G-H). However, CLL cells silenced for CRBN failed to experience enhanced degradation IKZF1 or IKZF3 upon treatment with lenalidomide, even at concentrations as high as 30 µM (Figure 5G-H). These results suggest that changes in expression levels of IKZF1 and IKZF3 may be involved in the CRBN-dependent mechanism-of-action of lenalidomide on CLL cells.

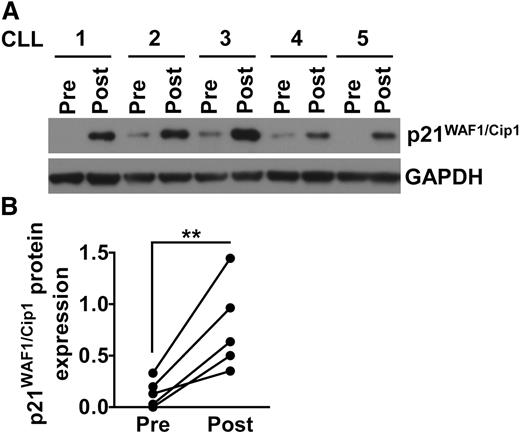

Lenalidomide induces p21 expression in vivo in CLL patients

To assess whether lenalidomide could induce p21 in CLL cells at concentrations that could be achieved in vivo, we examined CLL cells of patients before and after starting therapy with low-dose lenalidomide (eg, 5 mg by mouth daily). CLL blood mononuclear cells were isolated from patients (n = 5) before and 15 days after starting treatment with lenalidomide at 2.5 mg per day for the first week, and 5 mg per day for the second week. For each of these samples, the proportion of CD19+CD5+ cells exceeded 91%. Patients providing samples CLL1, CLL2, CLL3, CLL4, or CLL5 experienced a reduction from pretreatment values in their blood absolute lymphocyte counts of 41%, 22%, 40%, 88%, or 55%, respectively, following lenalidomide therapy. We examined the CLL cells for expression of p21 by immunoblot analysis (Figure 6A–B). For all patient samples examined, we observed induced-expression of p21 in the CLL cells of patients following initiation of therapy with lenalidomide. These results indicate that lenalidomide can induce the expression of p21 in CLL cells of patients receiving doses as low as 5 mg per day.

Lenalidomide therapy induces p21 expression in CLL cells in vivo. (A-B) CLL blood mononuclear cells from 5 different patients were collected prior therapy (Pre) and 15 days after lenalidomide treatment (Post). All patients received 2.5 mg daily for the first 7 days, and 5 mg daily for the subsequent 7 days. Protein were extracted from all samples and analyzed for p21 and GAPDH expression by immunoblot. (A) Shows the immunoblot data for all 5 patients tested. (B) Shows the densitometry analysis quantifying the expression of p21 protein in the 5 patient samples shown in (A). The expression of p21 has been normalized to GAPDH. **P < .001 (Student t test).

Lenalidomide therapy induces p21 expression in CLL cells in vivo. (A-B) CLL blood mononuclear cells from 5 different patients were collected prior therapy (Pre) and 15 days after lenalidomide treatment (Post). All patients received 2.5 mg daily for the first 7 days, and 5 mg daily for the subsequent 7 days. Protein were extracted from all samples and analyzed for p21 and GAPDH expression by immunoblot. (A) Shows the immunoblot data for all 5 patients tested. (B) Shows the densitometry analysis quantifying the expression of p21 protein in the 5 patient samples shown in (A). The expression of p21 has been normalized to GAPDH. **P < .001 (Student t test).

Discussion

This study describes, for the first time, a mechanism by which lenalidomide directly affects CLL cells, potentially contributing to its noted clinical activity in patients with CLL. Recent studies have found that patients with CLL may have a high rate of leukemia-cell turnover, with cell death rates balancing out the birth rates of new cells, which may represent approximately 1% of the leukemia-cell clone each day.17 Agents that interfere with the capacity of leukemia cells to grow could tilt the balance in favor of cell-death, resulting in clearance of leukemia cells, even when such agents lack direct cytotoxic activity. Lenalidomide potentially could act through such a mechanism. We found that lenalidomide could cause a dose-dependent inhibition of CLL-cell proliferation that resulted in the accumulation of cells in the G0/1 phase of the cell cycle. This activity was dependent upon the induced expression of the cell-cycle regulator p21 by a mechanism dependent on CRBN, a known molecular target of lenalidomide. Importantly, we observed these effects at concentrations as low as 0.3 µM, below the 0.6 µM estimated concentration of the drug found in the plasma of patients treated daily with 5 mg of lenalidomide.29 Consistent with this, we found that the CLL cells of patients treated with lenalidomide at such doses were induced to express p21 in vivo. As such, the capacity of lenalidomide to inhibit the proliferation of CLL cells may account in part for its observed clinical activity.

We found that lenalidomide could induce p21 in leukemia cells harboring del(17p) and a single dysfunctional mutant allele of p53, indicating that the cytostatic activity of this drug did not require functional p53. This may account in part for the observed clinical activity of lenalidomide in patients with CLL cells with del(17p).30-32 It also could support the notion of treating patients with lenalidomide to mitigate the risk of disease progression. Our results are consistent with the p53-independent mechanism by which lenalidomide upregulates p21 in the Namalwa cell line,33 into which a mutation prevents the binding of p53 to the p21 promoter. In these cells, the upregulation of p21 is mediated by a lysine-specific demethylase 1-dependent epigenetic mechanism, leading to a reduction in histone methylation and an increase in histone acetylation of the p21 promoter, which facilitates the access to DNA of transcription factors such as sp1, sp3, Egr1, and Egr2.33 Silencing experiments in multiple myeloma cells identified the contribution of sp1, sp3, Egr1, and Egr2 to the upregulation of p21 induced by lenalidomide or pomalidomide in plasma cells, even though none of these factors alone appeared to be physiologic regulators of p21 expression.33 Rather, it is suggested that a combination of these factors, and possibly others from the abundant array of p21 regulators,34 may be involved. A comparable complex network of factors also may be responsible for the lenalidomide-induced upregulation of p21 in CLL.

We found that the cytostatic activity of lenalidomide and its capacity to induce p21 in CLL cells was dependent upon CRBN. We observed that the silencing of CRBN in primary CLL cells mitigated the cytostatic effect of lenalidomide and inhibited its capacity to induce leukemia-cell expression of p21. This is consistent with the notion that reducing the expression levels of a drug target reduces its activity, and is also consistent with the data presented by Zhu et al, showing that the suppression of CRBN renders multiple myeloma cell lines less responsive to lenalidomide.24 CRBN is the adaptor protein part of a Cul4A-DDB1 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex and is the subunit responsible for substrate recognition.35 Our results suggest that the interaction of lenalidomide with this E3 ligase complex via binding to CRBN increases p21 expression, which ultimately contributes to cell-cycle arrest of CLL cells.

Recent studies identified the transcription factors IKZF1 (Ikaros) and IKZF3 (Aiolos) as being substrates of CRBN, which are rapidly degraded upon exposure to lenalidomide, and required for its antiproliferative and immunomodulatory activity.26-28 IKZF1 and IKZF3 are transcriptional regulators involved in hematopoiesis and in the development of the adaptive immune system.36 Work performed in mutant mouse models showed that IKZF1 is required at different levels in hematopoiesis, such as in the generation of chronic lymphoid precursors, while IKZF3 appears more restricted to B cells and is required for the generation of peritoneal, marginal, and recirculating B cells, as well as for the generation of long-lived plasma cells.36 These transcription factors may act as transcriptional repressors by forming complexes with proteins from the mSin3 family of co-repressors and histone deacetylases.37 Disruption of these complexes via lenalidomide-induced degradation of IKZF1 and IKZF3 could alleviate the repression of p21 transcription that may be mediated by factors such as Runx-1.38 This would be in line with the recently described mechanism of IL-2 de-repression in T cells following lenalidomide exposure that was dependent on IKZF1/IKZF3 degradation.26,27 Additional studies are required to evaluate whether these proteins are responsible for the cytostatic activity of lenalidomide in CLL cells.

Collectively, this study sheds new light on the mechanism-of-action of lenalidomide, which may inhibit CLL-cell proliferation. Such activity might mitigate the activity of drugs that are most active against cycling cells, accounting in part for the unfavorable results of clinical trials coupling lenalidomide with cytotoxic agents such as fludarabine monophosphate.39-41 This mechanism could also account in part for the lack of disease progression generally observed during lenalidomide maintenance therapy, regardless of whether the patient has leukemia cells that harbor del(17p) and/or have dysfunctional p53.42 Since lenalidomide is not directly cytotoxic to CLL cells, this drug might tilt the balance between leukemia-cell growth and cell death,17 conceivably resulting in a faster decline in tumor burden of patients who have relatively high rates of leukemia-cell turnover. Clinical trials combining heavy-water-labeling assessment of leukemia-cell turnover, and subsequent treatment with lenalidomide, would be required to formally test this hypothesis.

Authorship

Contribution: J.-F.F. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; E.M.G. performed research, analyzed data, and revised the paper; S.G. designed and performed research, and analyzed data; D.F., I.S.B., M.S., and B. Cui performed research and analyzed data; L.G.C., B. Cathers, and A.L.-G. designed research, supervised the study, and revised the paper; D.M. designed research, supervised the study, and revised the paper; T.J.K. designed research, supervised the study, provided patient samples, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: L.G.C., S.G., B. Cathers, and A.L.-G. are employees of Celgene Corporation. T.J.K. and D.M. received financial support from Celgene Corporation. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for I.S.B. is Genoptix, a Novartis Company, Carlsbad, CA 92008 and for D.M. is Inception Sciences, San Diego, CA 92121

Correspondence: Thomas J. Kipps, University of California, San Diego Moores Cancer Center, 3855 Health Sciences Dr, Rm 4307, La Jolla, CA 92093-0820; email: tkipps@ucsd.edu.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Andrew Abriol Santos Ang for his excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by research funding from the Celgene Corporation (T.J.K. and D.M.); the National Institutes of Health grant for the CLL Research Consortium (P01-CA081534) (T.J.K.); the Blood Cancer Research Fund (J.-F.F.); Le Fond de la Recherche en Santé du Québec (J.-F.F.); and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (SCOR grant #7005-14) (T.J.K.).

References

Author notes

D.M. and T.J.K. contributed equally to this study.

![Figure 1. CLL cells cocultured with CD154-expressing supportive cells are induced to proliferate. (A-B) CLL cells were labeled with CFSE and cocultured on HeLaCD154 in the presence of IL-4 and IL-10, as described in “Methods.” Cells were collected on days 2, 3, 6, and 10 for analysis by flow cytometry. The results of assays on 2 representative CLL samples are shown in (A) and the fraction of dividing cells observed in 6 patient samples tested is presented in (B). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s multiple comparison test were used to determine statistically significant differences from day 2. ***P < .001 (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]; n = 6). (C-D) CLL cells were labeled with CFSE and cocultured on FibroblastsCD154 in the presence of IL-4 and IL-10, as described in “Methods.” Cells were collected on days 1, 6, and 9 for analysis by flow cytometry. One representative CLL sample out of 4 is shown in (C) and the fraction of dividing cells observed in all 4 patients tested is presented in (D). One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test were used to determine statistically significant differences from day 1. ***P < .001 (mean ± SEM; n = 4). (E-F) CLL cells were cocultured on FibroblastsCD154 in the presence of IL-4 and IL-10, and at the indicated time, subjected to cell-cycle analysis following PI staining. One representative CLL sample out of 4 is shown in (E) and the fraction of cells in each phase for all 4 patients tested is presented in (F). **P < .01; ***P < .001 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 4). (G-H) CLL cells were cocultured on FibroblastsCD154 in the presence of IL-4 and IL-10, and at the indicated time, subjected to 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation for a period of 4 hours, as described in “Methods.” One representative CLL sample out of 4 is shown in (G) and the fraction of EdU+ cells observed in all 4 patients tested is presented in (H). **P < .01 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 4). (I) CLL cells from 3 different patients were cocultured on HeLa CD154 or nontransfected HeLa cells in the presence of IL-4 and IL-10. At the indicated days, live CLL-cell counts were assessed by flow cytometry, as described in “Methods,” and are presented as expansion folds relative to day 1. *P < .05 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 3).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/124/10/10.1182_blood-2014-03-559591/4/m_1637f1.jpeg?Expires=1767736995&Signature=CMFys8bLwESDW~oW0dzlc7Xm-850PVOKJiyXI2uyOQ9hhFoKEaTgfQCMz1N2Bsxo~Hmj6AOAENzSjzFXgw4GSu7UFpyHZOAwoP8s14ZYaNGimrmc3xyzNf8ZS8MGFQ-XaKfjx6yjapsdG9lClBylinbcpchE0qpk7ig3ZRC7PZRib19h0UQH8uRYBq5cYiZMnuZ3aqri-PA~BNOe~Ml-vRiVxqPriFIyp3JpHWiv4LR7LzNSi-6bR8qvO2dNYraURrklV9qbmztduAk7JapXNigLm4YGBywF0EtmLmNsXHdaUUf~OHlkcjiw8Vip79NtvZBFb4EqIcbncuTvG6oXeA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 3. Lenalidomide upregulates p21 in CLL cells. (A) CLL cells from 4 patient samples were cocultured with FibroblastsCD154 and IL-4/IL-10, and exposed to 10 µM lenalidomide or the equivalent volume of DMSO. After 24 hours, the cells were collected and analyzed for the expression levels of p21 messenger RNA (mRNA) by QuantiGene. The expression of hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyltransferase was monitored as housekeeping gene and used to normalize p21 expression level for each sample. *P < .05 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 4). (B-C) CLL cells were cocultured with HeLaCD154 and IL-4/IL-10 and exposed to increasing amounts of lenalidomide or vehicle control. In parallel, HeLaCD154 alone were cultured with increasing doses of lenalidomide as a control. After 24 hours, the cells were collected and protein extracted for the analysis of p21, p53, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression by immunoblot. In (B), the results from 3 CLL samples are shown, along with the HeLaCD154 control, for which the same amount of total protein as the CLL cells was run. In (C), the densitometry analysis of p21 and p53 expression is presented for all 3 patients from (B). The intensity of the target proteins were normalized to GAPDH levels. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test were used to determine statistically significant differences from control. *P < .05; ***P < .001 (mean ± SEM; n = 3). (D) CLL cells from a sample deficient in functional p53 (p53 def) and from a sample with functional p53 (p53 WT) were exposed to either γ-irradiation (1 Gy) or 3 µM lenalidomide followed by 8 hours incubation, at which point the cells were collected for protein extraction and detection of p21, p53, and GAPDH by immunoblot. (E-F) CLL cells from 16 patients were cocultured with HeLaCD154 and IL-4/IL-10 and exposed to 3 µM lenalidomide or DMSO. After 3 days, the cells were collected, lysed, and analyzed for p21 and GAPDH expression by immunoblot. (E) Shows the immunoblot results, while (F) presents the densitometry analysis quantifying the expression levels of p21 protein for all patients presented in (E). The expression levels of p21 have been normalized to GAPDH. ***P < .001 (Student t test). (G) CLL cells were cocultured with HeLaCD154 and IL-4/IL-10 and exposed to 3 µM lenalidomide or an equivalent volume of DMSO. At day 3, a fraction of the cells were collected, lysed, and analyzed for the expression of p21 and GAPDH by immunoblot, as described above. At day 6, viable cell counts were performed by flow cytometry as described in “Methods.” The percent decrease in proliferation for each patient measured at day 6 (100 × [expansion foldCTRL-treated samples − expansion foldlenalidomide-treated samples] / expansion foldCTRL-treated samples) is presented in function of the percent increase in p21 protein expression measured by densitometry analysis as above (100 × [p21CTRL-treated samples – p21lenalidomide-treated samples] / p21CTRL-treated samples). Each dot represents data from 1 CLL patient (n = 22; Pearson r = 0.52).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/124/10/10.1182_blood-2014-03-559591/4/m_1637f3.jpeg?Expires=1767736995&Signature=foLVSfWr5T2mXYOwGHfUcnjD5XVD4RL8n6uwIq9OuuxWj9ZDVvZd6DnJoAJtO8lTUMCbATa8DVK7meusBeFPgHHxMrs43QmM-NTrr9jkgnFpCGJZoaLgpuLkzs0quTW0ibkpJ~jPvyVuEyqMBUmqVaUOxGg9968fox5N0ldtG8ObMZNexqL9awDkkK4jcLMip3RNUOOTiwoi~kLryQPjPQm8yy1I23WDiqiTQjy3NhbIX~dwF7S8E16dpQvHrkhRiBNeg7eflj-Ar5hFMjq5rXG~wWZmmLGjWLPjFOUy3dQK7BM9Zotsf-dp8f~~aNCcJYV-5lAp3Tv4ENHqU5BHgA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 4. p21 silencing in CLL cells interferes with the antiproliferative activity of lenalidomide. (A-B) siRNAs specific for p21 or nonspecific siRNA control (CTRL) were transfected into CLL cells using HiPerFect reagent as described in “Methods,” and cocultured on HeLaCD154 and IL-4/IL-10. After 48 hours, the cells were collected and lysed for detection of p21 and GAPDH protein by immunoblot. In (A), data from 2 representative patients are presented, and in (B) densitometry analysis quantifying the levels of p21 protein in 5 different CLL samples is shown. The expression of p21 has been normalized to GAPDH. **P < .01 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 5). (C-D) CLL cells from 4 patient samples were transfected as in (A) with either CTRL siRNA or p21 siRNA, and cocultured on HeLaCD154 and IL-4/IL-10 in the presence of 3 µM lenalidomide or control media. After 48 hours, the cells were collected and lysed for detection of p21 and GAPDH protein by immunoblot. In (C), data from 2 representative patients are presented, and in (D) densitometry analysis quantifying the levels of p21 protein in 4 different CLL samples is shown. The expression of p21 has been normalized to GAPDH. *P < .05 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 4). (E) CLL cells from 5 patient samples were transfected as in (A) with either CTRL siRNA or p21 siRNA, and exposed to 3 µM lenalidomide or DMSO. After 72 hours, CLL-cell proliferation was measured using 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation, which provides absorbances at 450 to 690 nm. *P < .05; **P < .01 (Student t test, mean ± SEM; n = 5). (F) Proliferation data from (E) were used to calculate the percent inhibition of proliferation induced by lenalidomide in p21-silenced cells and in CTRL cells ([AbsorbanceCTRL-treated samples – Absorbancelenalidomide-treated samples] / AbsorbanceCTRL-treated samples × 100). **P < .01 (Student t test).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/124/10/10.1182_blood-2014-03-559591/4/m_1637f4.jpeg?Expires=1767736995&Signature=kuDuiZWpXA1UmyggI2lhwXuHQ3OLmY5yHj1uJjIpqoOFLnJrEIrwcyfstdyuJcikiA6SNG055DcxqKNe9JZavg0zup9OXColoTItnvzVOKBy2xhLZzOWHwC7M5qPgSKRiWF35P4-XzXsq9ee0fF~Aqzz0r-0EP0yERW4j3piIEbO-ZEUzAIdoT~gRVR0AcjgpTIcoxxfLCh3JBE7f3SUE1eOw5mo9nwtyTAHpTCewxk2gMiqJuguN58B2NGGnXmVmqN9H9A~PuYsaTcY~EzYqmHHZ7VU4y8XuySK6vQPwGZ0FsVl8mIc7BQToAUwIm7yqThmlTIbCXB-3uKmPdFBcQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)