Key Points

Stimulation of the BCR activates JAK2 and STAT3 in CLL cells.

The JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib induces apoptosis of CLL cells.

Abstract

In chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), stimulation of the B-cell receptor (BCR) triggers survival signals. Because in various cells activation of the Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway provides cells with survival advantage, we wondered whether BCR stimulation activates the JAK/STAT pathway in CLL cells. To stimulate the BCR we incubated CLL cells with anti-IgM antibodies. Anti-IgM antibodies induced transient tyrosine phosphorylation and nuclear localization of phosphorylated (p) STAT3. Immunoprecipitation studies revealed that anti-JAK2 antibodies coimmunoprecipitated pSTAT3 and pJAK2 in IgM-stimulated but not unstimulated CLL cells, suggesting that activation of the BCR induces activation of JAK2, which phosphorylates STAT3. Incubation of CLL cells with the JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib inhibited IgM-induced STAT3 phosphorylation and induced apoptosis of IgM-stimulated but not unstimulated CLL cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Whether ruxolitinib treatment would benefit patients with CLL remains to be determined.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells traffic between the peripheral blood (PB) and lymphoid organs,1,2 in which they are amenable to extracellular signals that protect them from apoptosis and stimulate their proliferation.3 CLL cells obtained from lymph nodes expressed B-cell receptor (BCR) activation genes, suggesting that antigen stimulation of the BCR activates antiapoptotic signals.4,5

In circulating CLL cells, the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) is constitutively phosphorylated on serine-727 residues.6,7 Tyrosine phosphorylated (p) STAT3 is rarely detected in unstimulated circulating CLL cells in PB. However, extracellular factors such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) induce transient tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 in CLL cells.7 Tyrosine pSTAT3 shuttles to the nucleus, binds to DNA, and activates transcription of antiapoptosis genes.7-11 Whether stimulation of the BCR induces tyrosine pSTAT3 as well is unknown. Because stimulation of normal BCRs induces tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3,12 we sought to determine whether stimulation of CLL-cell BCRs induces tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 and which signaling pathway or pathways are engaged in this process.

Study design

Cell fractionation

PB cells were obtained from untreated CLL patients (supplemental Table 1; available on the Blood Web site) who were followed at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Leukemia Center from 2011 to 2013 after the patients gave Institutional Review Board–approved informed consent to participate in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The cells were fractionated using Histopaque-1077 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Activation of the BCR

Freshly isolated CLL B cells were resuspended in a culture medium as described previously.7 BCR stimulation was performed via incubation with 10 μg/mL goat F(ab′)2 anti-human IgM (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA).

Western immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation

Western immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation studies were performed as described previously.7 The following primary antibodies were used: monoclonal mouse anti-human STAT3 (BD Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA); rabbit anti-human serine pSTAT3, rabbit anti-human tyrosine pSTAT3, rabbit anti-human Janus kinase 2 (JAK2), and rabbit anti-human tyrosine pJAK2 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA); mouse anti-human lamin B, mouse anti-human S6, and poly(adenosine 5′-diphosphate-ribose) polymerase (PARP; Calbiochem, Billerica, MA); and mouse anti-human β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich).

Isolation of nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts

Nondenatured nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts of CLL cells were prepared using an NE-PER extraction kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) and confirmed western blot–based detection of the nuclear protein lamin B and cytoplasmic S6 ribosomal proteins.7

Apoptosis assay

The rate of cellular apoptosis was analyzed via flow cytometry using double staining with a Cy5-conjugated annexin V and propidium iodide (PI; BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Confocal microscopy

Confocal microscopy was performed as previously described with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), S6, and tyrosine pSTAT3 (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA).7

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

RNA was isolated using an RNeasy purification procedure (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). Five hundred nanograms of total RNA was used in 1-step quantitative reverse transcription–PCR (qRT-PCR; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Real-time PCR and qRT-PCR were performed as previously described.7

Results and discussion

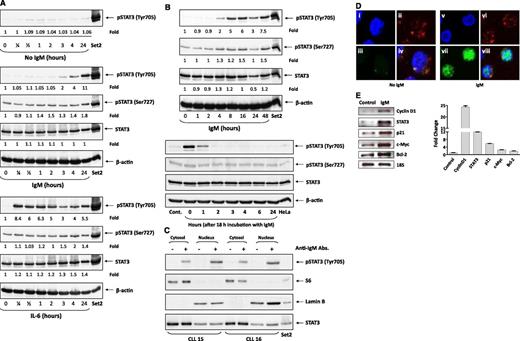

To determine whether activation of the BCR in CLL cells induces tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3, CLL cells from PB were incubated with anti-IgM antibodies, which are known to activate the BCR in CLL cells.13,14 In all experiments, anti-IgM antibodies induced tyrosine pSTAT3 and slightly increased serine pSTAT3 levels. Contrary to IL-6 that induced tyrosine pSTAT3 within 15 minutes (Figure 1A), anti-IgM antibodies induced phosphorylation of STAT3 within 2 hours (Figure 1B). However, the anti-IgM–induced phosphorylation of STAT3 was short lived. Two hours after IgM washout, tyrosine pSTAT3 was no longer detected (representative results from 3 identical separate experiments are depicted in Figure 1A-B).

Stimulation of the BCR induces tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 in CLL cells. (A) Time-dependent increase in pSTAT3 levels induced by incubation of CLL cells with anti-IgM antibodies. CLL cells were incubated without or with 10 μg/mL goat F(ab′)2 anti-human IgM antibodies (upper panel) or with 20 ng/mL IL-6 (lower panel). Cells were harvested at several time points, lysed, and analyzed using western immunoblotting with anti-tyrosine pSTAT3, anti-serine pSTAT3, and anti-STAT3 antibodies. SET2 cells were used as positive controls. As shown, tyrosine pSTAT3 was detected 2 hours from exposure to anti-IgM antibodies (upper panel) but only after 15 minutes of exposure to IL-6. This experiment was repeated 3 times using samples from patients 4, 13, and 17 (supplemental Table 1). (B) Tyrosine pSTAT3 levels remained increased after prolonged (up to 48 hours) exposure to anti-IgM antibodies (upper panel) but diminished 1 hour and were no longer detected 2 hours after washout. As shown in the upper panel, CLL cells were incubated with 10 μg/mL anti-IgM antibodies for 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, and 48 hours; harvested; and analyzed by western immunoblotting using anti-tyrosine pSTAT3, anti-serine pSTAT3, anti-STAT3, and anti-actin antibodies. Cells from patient 2 (supplemental Table 1) were used in this experiment. Two additional experiments yielded similar results (data not shown). As depicted in the lower panel, IgM-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 is short lived. CLL cells were incubated for 18 hours with or without (Cont.) 10 μg/mL anti-IgM antibodies. The antibodies were then washed out and the cells were harvested at different time points, and the cell lysates were analyzed using western immunoblotting with anti-tyrosine pSTAT3, anti-serine pSTAT3, and anti-STAT3 antibodies. This experiment was repeated 2 times using samples from patients 3 and 18 (supplemental Table 1). (C) IgM-induced tyrosine pSTAT3 is detected in the cytosol and nucleus of CLL cells. CLL cells were incubated for 2 hours with or without 10 μg/mL anti-IgM antibodies. The extract was fractionated, and the nuclear and cytoplasmic preparations were analyzed using western immunoblotting with anti-tyrosine pSTAT and anti-STAT3 antibodies. Anti-lamin B antibodies were used to detect the nuclear fractions, and anti-S6 antibodies to detect the cytoplasmic fractions. As shown, S6 was not detected in the nuclear fraction, and lamin B was not detected in the cytoplasmic fraction. Tyrosine pSTAT3 was detected both in the nuclear (lamin B–positive) and cytoplasm (S6-positive) fractions of CLL cells incubated with but not without anti-IgM antibodies. We intentionally loaded more cytosolic protein. This experiment was repeated 3 times using samples from patients 15, 16, and 18 (data obtained using cells from patient 18 are not shown) (supplemental Table 1). (D) Tyrosine pSTAT3 is detected in the nucleus and cytosol of IgM-stimulated but not unstimulated CLL cells. Cells were incubated for 2 hours without or with 10 μg/mL anti-IgM antibodies. The cells were cytospun, fixed on glass slides, and stained with the nuclear stain 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole, shown in blue (panels i, v); anti-S6 antibodies, shown in red (panels ii, vi); or anti-tyrosine pSTAT3 antibodies, shown in green (panels iii, vii). Tyrosine pSTAT3 was not detected in unstimulated CLL cells (left panel). However, following incubation with anti-IgM antibodies, tyrosine pSTAT3 was detected in the nucleus (panel vii) and also in the cytosol (merged panel viii). Cells from patient 7 (supplemental Table 1) were used in this experiment. (E) Anti-IgM antibodies increased STAT3-targeted gene levels. RNA was extracted from CLL cells incubated for 2 hours without or with 10 μg/mL anti-IgM antibodies. The left panel depicts agarose gel electrophoresis of RT-PCR, and the right panel depicts qRT-PCR assessed using the TakMan gene

Stimulation of the BCR induces tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 in CLL cells. (A) Time-dependent increase in pSTAT3 levels induced by incubation of CLL cells with anti-IgM antibodies. CLL cells were incubated without or with 10 μg/mL goat F(ab′)2 anti-human IgM antibodies (upper panel) or with 20 ng/mL IL-6 (lower panel). Cells were harvested at several time points, lysed, and analyzed using western immunoblotting with anti-tyrosine pSTAT3, anti-serine pSTAT3, and anti-STAT3 antibodies. SET2 cells were used as positive controls. As shown, tyrosine pSTAT3 was detected 2 hours from exposure to anti-IgM antibodies (upper panel) but only after 15 minutes of exposure to IL-6. This experiment was repeated 3 times using samples from patients 4, 13, and 17 (supplemental Table 1). (B) Tyrosine pSTAT3 levels remained increased after prolonged (up to 48 hours) exposure to anti-IgM antibodies (upper panel) but diminished 1 hour and were no longer detected 2 hours after washout. As shown in the upper panel, CLL cells were incubated with 10 μg/mL anti-IgM antibodies for 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, and 48 hours; harvested; and analyzed by western immunoblotting using anti-tyrosine pSTAT3, anti-serine pSTAT3, anti-STAT3, and anti-actin antibodies. Cells from patient 2 (supplemental Table 1) were used in this experiment. Two additional experiments yielded similar results (data not shown). As depicted in the lower panel, IgM-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 is short lived. CLL cells were incubated for 18 hours with or without (Cont.) 10 μg/mL anti-IgM antibodies. The antibodies were then washed out and the cells were harvested at different time points, and the cell lysates were analyzed using western immunoblotting with anti-tyrosine pSTAT3, anti-serine pSTAT3, and anti-STAT3 antibodies. This experiment was repeated 2 times using samples from patients 3 and 18 (supplemental Table 1). (C) IgM-induced tyrosine pSTAT3 is detected in the cytosol and nucleus of CLL cells. CLL cells were incubated for 2 hours with or without 10 μg/mL anti-IgM antibodies. The extract was fractionated, and the nuclear and cytoplasmic preparations were analyzed using western immunoblotting with anti-tyrosine pSTAT and anti-STAT3 antibodies. Anti-lamin B antibodies were used to detect the nuclear fractions, and anti-S6 antibodies to detect the cytoplasmic fractions. As shown, S6 was not detected in the nuclear fraction, and lamin B was not detected in the cytoplasmic fraction. Tyrosine pSTAT3 was detected both in the nuclear (lamin B–positive) and cytoplasm (S6-positive) fractions of CLL cells incubated with but not without anti-IgM antibodies. We intentionally loaded more cytosolic protein. This experiment was repeated 3 times using samples from patients 15, 16, and 18 (data obtained using cells from patient 18 are not shown) (supplemental Table 1). (D) Tyrosine pSTAT3 is detected in the nucleus and cytosol of IgM-stimulated but not unstimulated CLL cells. Cells were incubated for 2 hours without or with 10 μg/mL anti-IgM antibodies. The cells were cytospun, fixed on glass slides, and stained with the nuclear stain 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole, shown in blue (panels i, v); anti-S6 antibodies, shown in red (panels ii, vi); or anti-tyrosine pSTAT3 antibodies, shown in green (panels iii, vii). Tyrosine pSTAT3 was not detected in unstimulated CLL cells (left panel). However, following incubation with anti-IgM antibodies, tyrosine pSTAT3 was detected in the nucleus (panel vii) and also in the cytosol (merged panel viii). Cells from patient 7 (supplemental Table 1) were used in this experiment. (E) Anti-IgM antibodies increased STAT3-targeted gene levels. RNA was extracted from CLL cells incubated for 2 hours without or with 10 μg/mL anti-IgM antibodies. The left panel depicts agarose gel electrophoresis of RT-PCR, and the right panel depicts qRT-PCR assessed using the TakMan gene

Following cytokine-induced phosphorylation, STAT3 translocates to the nucleus.10 To determine whether BCR-induced tyrosine pSTAT3 also shuttles to the nucleus and activates STAT3-target genes, we prepared cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts of IgM-stimulated CLL cells and analyzed them using western immunoblotting.7 As shown in Figure 1C, tyrosine pSTAT3 was detected in the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of IgM-stimulated CLL cells. Similarly, confocal microscopy studies detected tyrosine pSTAT3 in the nucleus of IgM-stimulated, but not unstimulated, CLL cells (Figure 1D). RT-PCR revealed that anti-IgM antibodies upregulated STAT3-target genes whose levels were increased by 1.8-fold (BCL2) to 24-fold (Cyclin D1), as assessed by qRT-PCR (Figure 1E). Taken together, these results suggest that stimulation of the BCR induces tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 and mildly increases levels of serine pSTAT3, and that phosphorylation of STAT3 either at serine or tyrosine residues activates transcription.

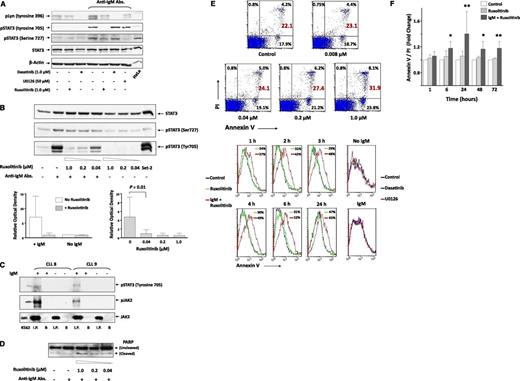

To determine which signaling pathways are engaged in BCR-induced STAT3 phosphorylation, we incubated CLL cells from 2 patients with or without anti-IgM antibodies and assessed the exposure to 3 kinase inhibitors. As shown in Figure 2A, 1 µM of the Abl and Lyn kinase inhibitor dasatinib15 completely blocked IgM-mediated phosphorylation of Lyn kinase, whereas the levels of IgM-induced pSTAT3 remained unchanged, suggesting that BCR-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 is Lyn independent. Also, the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway inhibitor U0126 (50 µM) downregulated the expression of serine pSTAT3 as described previously16 but did not affect the levels of tyrosine pSTAT3. Conversely, the JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib17 markedly reduced the level of tyrosine but not serine pSTAT3 in IgM-stimulated CLL cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2A-B), suggesting that activation of the BCR induces tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3, likely via activation of JAK2.

Anti-IgM antibodies induce tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK2 and STAT3 in CLL cells. (A) Ruxolitinib inhibited IgM-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3. CLL cells were pretreated with dasatinib, U0126, or ruxolitinib for 30 minutes. The cells were then harvested and incubated for 18 hours with or without 10 μg/mL anti-IgM antibodies (Abs.). Cell lysates were analyzed using western immunoblotting with total STAT3, anti-serine and anti-tyrosine pSTAT3, and anti-phosphorylated Lyn (pLyn) antibodies. HeLa cells served as positive controls. Samples from patients 13, 14, 15, and 16 (supplemental Table 1) were used. (B) Ruxolitinib inhibits tyrosine pSTAT3 in a dose-dependent manner. CLL cells were incubated without or with 10 μg/mL anti-IgM antibodies. Ruxolitinib was added for 30 minutes at concentrations ranging from 0.04 to 1.00 μM, and the cells were harvested and analyzed using western immunoblotting. Set-2 cells were used as positive controls. As shown in the upper panel, ruxolitinib inhibited tyrosine pSTAT3 in IgM-stimulated but not unstimulated CLL cells in a dose-dependent manner. This experiment was repeated twice using samples from patients 1 and 6 (supplemental Table 1). As shown in the left lower panel, densitometry analysis of western immunoblots from 4 different patients confirmed that ruxolitinib inhibited tyrosine pSTAT3 in IgM-stimulated but not in unstimulated CLL cells. Samples from patients 13, 14, 15, and 16 (supplemental Table 1) were used. As shown in the right lower panel, ruxolitinib inhibited tyrosine pSTAT3 in a dose-dependent manner. Densitometry analysis of western immunoblots of 6 different experiments was conducted. Depicted are the means ± standard deviation of the relative optical density of tyrosine pSTAT3, quantified and normalized to total levels of STAT3. This experiment was conducted 6 times using samples from patients 1, 2, 6, 7, 10, and 11 (supplemental Table 1). (C) Anti-JAK2 antibody coimmunoprecipitation of pJAK2 and tyrosine pSTAT3 in IgM-stimulated CLL cells. CLL cells from 4 patients were incubated for 2 hours with or without 10 μg/mL anti-IgM antibodies. Cell lysates were prepared, and JAK2 was immunoprecipitated (I.P.) with anti-JAK2 antibodies using protein A-agarose beads. Cells incubated with beads only (B) were used as negative controls. The immune complex was separated using sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and analyzed using western immunoblotting with anti-tyrosine pSTAT3, anti-tyrosine JAK2, and anti-JAK2 antibodies. K562 cells were used as positive controls. As shown, JAK2 was immunoprecipitated from lysates of IgM-treated or untreated CLL cells. However, phosphotyrosine STAT3 and pJAK2 were coimmunoprecipitated from IgM-treated but not untreated cells. These experiments were conducted using samples from patients 8, 9, 12, and 13. Representative results are depicted. Data obtained using cells from patients 12 and 13 are not shown (supplemental Table 1). (D) Ruxolitinib induces PARP cleavage in CLL cells. Cells were incubated for 18 hours with or without 10 μg/mL anti-IgM antibodies, and 0.04, 0.20, or 1.00 μM ruxolitinib was added for 30 minutes. The cells were then harvested and analyzed using western immunoblotting with anti-PARP antibodies. This experiment was repeated 6 times using samples from patients 1, 2, 6, 7, 10, and 11 (supplemental Table 1). (E) Ruxolitinib induces apoptosis of CLL cells. As shown in the upper panel, CLL cells were incubated for 18 hours with 10 μg/mL anti-IgM antibodies, and ruxolitinib was added to culture at increasing concentrations for 30 minutes. Apoptosis was assessed using flow cytometry with annexin V/PI staining. As shown, ruxolitinib induced apoptosis of CLL cells in a dose-dependent manner. Cells from patient 11 (supplemental Table 1) were used. As shown in the lower panel, ruxolitinib (but not dasatinib or U0126) induced apoptosis of IgM-stimulated CLL cells in a time-dependent manner. CLL cells were incubated without or with anti-IgM antibodies; ruxolitinib (1.0 μM), dasatinib (1.0 μM), or U0126 (50 μM) was added for 2 hours (right panel) or for different time intervals (1, 2, 3, 6, and 24 hours); and apoptosis was assessed after washout using the annexin V/PI assay, assessed by flow cytometry. As shown, ruxolitinib induced apoptosis of IgM-stimulated cells in a time-dependent manner, whereas dasatinib or U0126 did not affect the apoptosis rate of CLL cells. This experiment was repeated twice using cells from patients 1 and 7 (supplemental Table 1). (F) CLL cells from 3 patients (patients 20, 21, and 22) were incubated for 6 to 72 hours with or without ruxolitinib in the presence or absence of anti-IgM antibodies. Apoptosis rates of ruxolitinib-treated relative to untreated cells are depicted. As shown, ruxolitinib induced apoptosis of IgM-treated but not IgM-untreated CLL cells. *P < .05; **P < .001.

Anti-IgM antibodies induce tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK2 and STAT3 in CLL cells. (A) Ruxolitinib inhibited IgM-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3. CLL cells were pretreated with dasatinib, U0126, or ruxolitinib for 30 minutes. The cells were then harvested and incubated for 18 hours with or without 10 μg/mL anti-IgM antibodies (Abs.). Cell lysates were analyzed using western immunoblotting with total STAT3, anti-serine and anti-tyrosine pSTAT3, and anti-phosphorylated Lyn (pLyn) antibodies. HeLa cells served as positive controls. Samples from patients 13, 14, 15, and 16 (supplemental Table 1) were used. (B) Ruxolitinib inhibits tyrosine pSTAT3 in a dose-dependent manner. CLL cells were incubated without or with 10 μg/mL anti-IgM antibodies. Ruxolitinib was added for 30 minutes at concentrations ranging from 0.04 to 1.00 μM, and the cells were harvested and analyzed using western immunoblotting. Set-2 cells were used as positive controls. As shown in the upper panel, ruxolitinib inhibited tyrosine pSTAT3 in IgM-stimulated but not unstimulated CLL cells in a dose-dependent manner. This experiment was repeated twice using samples from patients 1 and 6 (supplemental Table 1). As shown in the left lower panel, densitometry analysis of western immunoblots from 4 different patients confirmed that ruxolitinib inhibited tyrosine pSTAT3 in IgM-stimulated but not in unstimulated CLL cells. Samples from patients 13, 14, 15, and 16 (supplemental Table 1) were used. As shown in the right lower panel, ruxolitinib inhibited tyrosine pSTAT3 in a dose-dependent manner. Densitometry analysis of western immunoblots of 6 different experiments was conducted. Depicted are the means ± standard deviation of the relative optical density of tyrosine pSTAT3, quantified and normalized to total levels of STAT3. This experiment was conducted 6 times using samples from patients 1, 2, 6, 7, 10, and 11 (supplemental Table 1). (C) Anti-JAK2 antibody coimmunoprecipitation of pJAK2 and tyrosine pSTAT3 in IgM-stimulated CLL cells. CLL cells from 4 patients were incubated for 2 hours with or without 10 μg/mL anti-IgM antibodies. Cell lysates were prepared, and JAK2 was immunoprecipitated (I.P.) with anti-JAK2 antibodies using protein A-agarose beads. Cells incubated with beads only (B) were used as negative controls. The immune complex was separated using sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and analyzed using western immunoblotting with anti-tyrosine pSTAT3, anti-tyrosine JAK2, and anti-JAK2 antibodies. K562 cells were used as positive controls. As shown, JAK2 was immunoprecipitated from lysates of IgM-treated or untreated CLL cells. However, phosphotyrosine STAT3 and pJAK2 were coimmunoprecipitated from IgM-treated but not untreated cells. These experiments were conducted using samples from patients 8, 9, 12, and 13. Representative results are depicted. Data obtained using cells from patients 12 and 13 are not shown (supplemental Table 1). (D) Ruxolitinib induces PARP cleavage in CLL cells. Cells were incubated for 18 hours with or without 10 μg/mL anti-IgM antibodies, and 0.04, 0.20, or 1.00 μM ruxolitinib was added for 30 minutes. The cells were then harvested and analyzed using western immunoblotting with anti-PARP antibodies. This experiment was repeated 6 times using samples from patients 1, 2, 6, 7, 10, and 11 (supplemental Table 1). (E) Ruxolitinib induces apoptosis of CLL cells. As shown in the upper panel, CLL cells were incubated for 18 hours with 10 μg/mL anti-IgM antibodies, and ruxolitinib was added to culture at increasing concentrations for 30 minutes. Apoptosis was assessed using flow cytometry with annexin V/PI staining. As shown, ruxolitinib induced apoptosis of CLL cells in a dose-dependent manner. Cells from patient 11 (supplemental Table 1) were used. As shown in the lower panel, ruxolitinib (but not dasatinib or U0126) induced apoptosis of IgM-stimulated CLL cells in a time-dependent manner. CLL cells were incubated without or with anti-IgM antibodies; ruxolitinib (1.0 μM), dasatinib (1.0 μM), or U0126 (50 μM) was added for 2 hours (right panel) or for different time intervals (1, 2, 3, 6, and 24 hours); and apoptosis was assessed after washout using the annexin V/PI assay, assessed by flow cytometry. As shown, ruxolitinib induced apoptosis of IgM-stimulated cells in a time-dependent manner, whereas dasatinib or U0126 did not affect the apoptosis rate of CLL cells. This experiment was repeated twice using cells from patients 1 and 7 (supplemental Table 1). (F) CLL cells from 3 patients (patients 20, 21, and 22) were incubated for 6 to 72 hours with or without ruxolitinib in the presence or absence of anti-IgM antibodies. Apoptosis rates of ruxolitinib-treated relative to untreated cells are depicted. As shown, ruxolitinib induced apoptosis of IgM-treated but not IgM-untreated CLL cells. *P < .05; **P < .001.

To confirm that BCR stimulation activates the JAK2/STAT3 pathway in CLL cells, we incubated CLL cells from 4 patients with or without anti-IgM antibodies for 2 hours. Subsequently, we immunoprecipitated the cell lysates with anti-JAK2 antibodies. As shown in Figure 2C, we detected both pJAK2 and tyrosine pSTAT3 in the JAK2-immunoprecipitated lysates of cells incubated with but not without anti-IgM antibodies, suggesting that stimulation of the BCR induces JAK2 phosphorylation and that pJAK2 binds to and phosphorylates STAT3 on tyrosine-705 residues in CLL cells.

Because pSTAT3 provides CLL cells with a survival advantage7 and exposure to ruxolitinib inhibited tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 in IgM-stimulated CLL cells, we investigated the effect of exposure to ruxolitinib on CLL-cell viability. As shown in Figure 2D-E, ruxolitinib, but not dasatinib or U0126, induced apoptosis of IgM-stimulated CLL cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner. This effect was observed in IgM-stimulated but not in unstimulated CLL cells (Figure 2E-F).

The recently described tonic low-grade activation of the BCR18 does not induce tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3, for which full-scale BCR stimulation resulting in activation of JAK2 is required. Whereas stimulation of the BCR induces rapid Syk or extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 phosphorylation,19 stimulation of the BCR for at least 2 hours was needed to induce tyrosine pSTAT3, suggesting that activation of transcription is required, a slow signaling pathway(s) is recruited, or both. Conversely, BCR-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 is short lived and therefore rarely detected in circulating CLL cells. In vitro models1 and gene expression profiles of CLL cells in PB and lymph nodes5 agree with these findings. Upon migration to PB, CLL cells are no longer stimulated by their microenvironment. Once the BCR is no longer engaged, the gene signature associated with BCR activation changes drastically.7

Taken together, our findings suggest that stimulation of the BCR activates the JAK2/STAT3 pathway in CLL cells. Whether treatment with ruxolitinib is clinically beneficial in patients with CLL remains to be determined.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Susan Smith for obtaining the patients’ clinical data and Don Norwood for editing the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant CA016672 and the CLL Global Research Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: M.J.K., Z.E., and S.V. were responsible for conception and design of the study; J.A.B., A.F., M.J.K., S.O., and W.G.W. were responsible for provision of study materials or patients; J.Y.W. performed the western blot and IP experiments; D.M.H. performed the PI/annexin assay; P.L. helped in the IP experiments; Z.L. performed the western blot and IP experiments; I.H.-H. helped in the IP and western blot experiments; U.R. and Z.E. wrote the manuscript; and U.R., J.Y.W., D.M.H., Z.L., P.L., I.H.-H., A.F., J.A.B., S.O., N.J., S.V., W.G.W., M.J.K., and Z.E. approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Zeev Estrov, Department of Leukemia, Unit 428, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: zestrov@mdanderson.org.