Abstract

The transcription factor c-JUN and its upstream kinase JNK1 have been implicated in BCR-ABL–induced leukemogenesis. JNK1 has been shown to regulate BCL2 expression, thereby altering leukemogenesis, but the impact of c-JUN remained unclear. In this study, we show that JNK1 and c-JUN promote leukemogenesis via separate pathways, because lack of c-JUN impairs proliferation of p185BCR-ABL–transformed cells without affecting their viability. The decreased proliferation of c-JunΔ/Δ cells is associated with the loss of cyclin-dependent kinase 6 (CDK6) expression. In c-JunΔ/Δ cells, CDK6 expression becomes down-regulated upon BCR-ABL–induced transformation, which correlates with CpG island methylation within the 5′ region of Cdk6. We verified the impact of Cdk6 deficiency using Cdk6−/− mice that developed BCR-ABL–induced B-lymphoid leukemia with significantly increased latency and an attenuated disease phenotype. In addition, we show that reexpression of CDK6 in BCR-ABL–transformed c-JunΔ/Δ cells reconstitutes proliferation and tumor formation in Nu/Nu mice. In summary, our study reveals a novel function for the activating protein 1 (AP-1) transcription factor c-JUN in leukemogenesis by antagonizing promoter methylation. Moreover, we identify CDK6 as relevant and critical target of AP-1–regulated DNA methylation on BCR-ABL–induced transformation, thereby accelerating leukemogenesis.

Introduction

Activating protein 1 (AP-1) functions as a dimeric transcription factor in important cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis.1-3 This wide range of different roles is made possible by the variable compositions of many homo- and heterodimers that are formed by the JUN, FOS, ATF, and MAF proteins that comprise the AP-1 transcription factors.4,5

c-JUN was originally identified as the normal cellular counterpart of the avian sarcoma JUN oncoprotein (v-JUN). Mouse model experiments revealed the essential role of c-JUN for development. c-Jun−/− mice die at embryonic day 12.5-13.5, displaying multiple defects in liver, heart, and neural crest.6,7 c-JUN was shown to transform cells in culture,6-8 and is commonly expressed at high levels in human malignancies.9,10 High levels of c-JUN have been described in a large fraction of human melanoma samples,11 liposarcomas,12 and lymphomas13 and are important players in skin and liver tumorigenesis.14,15 The tumor-promoting roles of c-JUN have been attributed either to growth-accelerating effects via the regulation of CYCLIN expression16 or to antiapoptotic properties. In hepatocytes, c-JUN antagonizes the function of the tumor-suppressor protein p53 and protects transformed hepatocytes from cell death.17 In T cells, c-JUN is involved in the expression of the FAS ligand (FASL), triggering apoptosis through the FAS receptor.18

In BCR-ABL–driven leukemogenesis, both c-JUN and its upstream regulator JNK1 have been described as tumor promoters.19-22 For JNK1−/−–transformed cells, the underlying mechanism has been elucidated: JNK1−/− cells express severely reduced levels of the antiapoptotic protein BCL2, which leads to a significantly delayed leukemogenesis in BCR-ABL–transformed cells.21 However, it remained unclear whether this effect was mediated via c-JUN–dependent phosphorylation.

DNA methylation and modifications of histone proteins such as acetylation or methylation regulate gene expression by affecting the binding of transcription factors to DNA via changes in the structure of chromatin (ie, c-MYC).23 This may either result in gene activation or gene silencing. Alterations of epigenetic marks, especially of DNA methylation, have been associated with all stages of tumor formation and progression. DNA methylation implicates the covalent addition of a methyl group to the 5′ carbon of cytosine bases within cytosine-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides. Regions in the genome where the CpG dinucleotide occurs at high density are called CpG islands (CGIs), and can be found in approximately 60% of the human gene promoter regions extending into the 5′-coding end of the gene. Whereas 70% to 80% of all non-CGI CpG dinucleotides in the human genome are methylated, CGI CpG dinucleotides usually remain unmethylated. In general, CGI methylation is associated with transcriptional gene silencing.24-26

We describe a novel mechanism through which the AP-1 transcription factor modulates tumorigenesis. In B-lymphoid cells, c-JUN counteracts the BCR-ABL–induced DNA methylation within the 5′ region of Cdk6, thereby preventing the BCR-ABL–induced silencing of the CDK6 gene. A lack of regulation or down-regulation of CDK6 is associated with a pronounced increase of disease latency, as verified by the use of Cdk6−/− mice. Our study reveals primary insights into the role of AP-1 transcription factors for oncogene-induced gene silencing. Moreover, we provide the first conclusive evidence for a nonredundant tumor-promoting role of CDK6 in lymphoid malignancies.

Methods

Mice and infection of neonatal mice with Ab-MuLV

c-Junfl/fl,27 CD19-Cre+/−,28 Jnk1−/−,29 c-JunAA/AA,30 p53−/−,31 Cdk6−/−,32 Nu/Nu, and Rag2−/− mice33 have been described previously. Animal experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the animal welfare committee of the Medical University of Vienna.

Newborn mice were injected IP with 50 μL of replication-incompetent ecotropic retrovirus encoding for Ab-MuLV.34 Sick mice were killed. Peripheral blood, lymphoid tissues, and hematopoietic organs were analyzed for leukemic cells by FACS and by histopathology.

Cell culture, infection of fetal liver cells, and expression vectors

Transplantation of tumor cells into Rag2−/− and Nu/Nu mice

For tail-vein injections, a defined cell number from independently derived pMSCV-p185BCR-ABL-IRES-GFP–transformed cell lines was injected into Rag2−/− mice. For subcutaneous injections, 1 × 106 cells were injected into Nu/Nu mice. Sick mice were killed and analyzed for spleen weights, white blood cell counts, and the presence of leukemic cells in BM, spleen, liver, and blood by FACS analysis.

[3H]-thymidine incorporation

Cells (5 × 104) were plated in triplicate in 96-well plates and [3H]-thymidine (0.1 μCi/well [MBq/well]) was added. After 12 hours of incubation, analysis was performed with Ultima Gold MV scintillation fluid (Packard Instruments) using a scintillation counter.

Flow cytometric analysis

FACS analysis was performed using a FACSCanto flow cytometer using FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences).

B-cell development staining

We used different antibodies to determine the specific B-lineage maturation stages: B220 (CD45R; RA3-6B2), CD43 (1B11), CD19 (1D3), BP-1 (6C3), IgM (R6-60.2), and IgDb (IgH-5b; 217-170), all from BD Pharmingen.

Cell-cycle analysis

Cells (5 × 106) were stained with propidium iodide (50 μg/mL) in a hypotonic lysis solution (0.1% sodium citrate, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 100 μg/mL RNAse) and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes.

Protein analysis and Western blotting

Cells were lysed in a buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (50mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 0.1% Tween 20, 150mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 20mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.1mM sodium vanadate, 1mM sodium fluoride, 10 μg/mL aprotinin, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, and 1mM PMSF). Protein concentrations were determined using a bicinchoninic acid kit (Pierce). Proteins (100 μg) were separated on 12% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto Immobilon membranes. Membranes were probed with antibodies directed against CDK6 (C8343) and β-ACTIN (A-4700), both from Sigma-Aldrich; and c-JUN (sc-1694x), p53 (sc-6243), BCL2(sc-7382), CDK4 (sc-260), p21 (sc-471), p27 (sc-1641), p15INK4b (sc-612), and p16INK4a (sc-1207), all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Immunoreactive bands were visualized by chemiluminescent detection (ECL detection kit; Amersham).

Treatment with Aza-dC

Cells were seeded in 1μM 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (Aza-dC; Sigma-Aldrich). After 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours of incubation, Western blot analysis was performed.

RNA isolation and real-time RT-PCR analysis

RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen). First-strand cDNA synthesis and PCR amplification were performed using a RT-PCR kit (GeneAmp RNA PCR kit; Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Real-time RT-PCR was performed on a RealPlex cycler using RealMasterMix (Eppendorf) and SYBR Green, as described previously.36 The following primer pairs were used: Gapdh: 5′-AGAAGGTGGTGAAGCAGGCATC-3′ and 5′-CGGCATCGAAGGTGGAAGAGTG-3′ and Cdk6: 5′-GCTTCGTGGCTCTGAAGCGCG-3′ and 5′-TGGTTTCTGT- GGGTACGCCGG-3′.

Real-time RT-PCR for Dnmt

Total RNA (1 μg) was used for cDNA preparation using the Omniscript RT kit (QIAGEN). Real-time RT-PCR of Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b was performed using Taqman gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems), as recommended by the manufacturer. Gapdh was used as a reference gene for normalization of RT-PCR data.

Nucleic acid isolation, MSP, and bisulfite genomic sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from murine c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ cell lines by digestion with proteinase K, followed by standard phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Afterward, 1 μg of genomic DNA was used for chemical modification by sodium bisulfite using the EpiTect kit (QIAGEN). The methylation status of the region 5′ to the coding sequence of Cdk6 (ENSMUSG00000040274, www.ensembl.org, release 52) was analyzed by methylation-specific PCR (MSP). MSP primers sequences were designed using the MethPrimer program37 and are as follows: Cdk6m-fwd, 5′-TAGTTCGGCGGTCGCGAGTTCG-3′, Cdk6m-rev, 5′-CGCACGCGCTTCAAAACCACG-3′, Cdk6u-fwd, 5′-TAGTTTGGTGGTTGTGAGTTTG-3′ and Cdk6u-rev, 5′-TCACACACACTTCAAAACCACA-3′. PCR was performed under the following conditions: initial denaturation for 12 minutes at 95°C, followed by 38 cycles of denaturation for 30 seconds at 95°C, annealing for 40 seconds at 64°C, and extension for 30 seconds at 72°C, with a final extension for 7 minutes at 72°C. MSP products were separated in 2% agarose gels stained with GelRed (Biotium), and visualized under UV spectrophotometry. DNA extracted from murine cell lines was treated with Sss1 CpG methylase (New England Biolabs) and was used as a positive control for methylated alleles. Water blanks were used as negative controls.

For bisulfite genomic sequencing, PCR primers were designed to anneal at both methylated and unmethylated bisulfite-converted DNA: Cdk6-seq-f, GAAGGATAGTTTGAGTYGYGT and Cdk6-seq-r, TAACTACCCRAAAACCACCRCA. PCR products were gel excised and cloned using the TOPO cloning kit (Invitrogen). Ten clones of each c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ cell were sequenced using M13 reverse primers.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as mean values ± SEM. Biochemical experiments were performed in triplicate, and a minimum of 3 independent experiments was evaluated. Differences were assessed for statistical significance by an unpaired 2-tailed t test or the log-rank test (for Kaplan-Meier plots).

Results

JNK1 and c-JUN are involved in BCR-ABL–induced transformation

The AP-1 upstream kinase JNK1 and the AP-1 transcription factor c-JUN have been implicated in BCR-ABL–driven leukemogenesis.19,21,22 We confirmed these previous observations by performing colony formation assays in growth factor–free methylcellulose. Fetal liver cells were prepared from Jnk1−/− and c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/− embryos and the appropriate controls, and infected with a retrovirus encoding p185BCR-ABL (pMSCV-p185BCR-ABL-IRES-GFP). As expected, a significant reduction of growth factor–independent colony numbers was detected when Jnk1−/− or c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/− hematopoietic cells were used (Figure 1A-B). After transformation, CD19+/CD43+ leukemic cell lines were generated from all cultures.

c-JUN is involved in p185BCR-ABL-induced transformation and leukemogenesis. Colony formation assays were performed using 1 × 106 (A) JNK1+/− and JNK1−/− (n = 8; 2-tailed t test, 49.2 ± 7.9 vs 28.9 ± 4.1 colonies/107 fetal liver cells, P = .0401) and (B) c-Junfl/fl and c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/− (n = 6; 2-tailed t test, 60.5 ± 6.1 vs 27.3 ± 1.9 colonies/107 fetal liver cells, P = .0004) fetal liver cells after infection with a pMSCV-p185BCR-ABL-IRES-GFP retrovirus in growth factor–free methylcellulose. (C) Transplantation of 1 × 105c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ cells into Rag2−/− mice. Two independent cell lines for each cell type were injected in 9 mice (mean survival, 11 vs 16 days in mice injected with c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ cells, respectively, P = .0307). (D) Spleen weights of diseased recipient Rag2−/− mice were analyzed (c-Junfl/fl [n = 9] and c-JunΔ/Δ [n = 9], 2-tailed t test, P = .0169).

c-JUN is involved in p185BCR-ABL-induced transformation and leukemogenesis. Colony formation assays were performed using 1 × 106 (A) JNK1+/− and JNK1−/− (n = 8; 2-tailed t test, 49.2 ± 7.9 vs 28.9 ± 4.1 colonies/107 fetal liver cells, P = .0401) and (B) c-Junfl/fl and c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/− (n = 6; 2-tailed t test, 60.5 ± 6.1 vs 27.3 ± 1.9 colonies/107 fetal liver cells, P = .0004) fetal liver cells after infection with a pMSCV-p185BCR-ABL-IRES-GFP retrovirus in growth factor–free methylcellulose. (C) Transplantation of 1 × 105c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ cells into Rag2−/− mice. Two independent cell lines for each cell type were injected in 9 mice (mean survival, 11 vs 16 days in mice injected with c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ cells, respectively, P = .0307). (D) Spleen weights of diseased recipient Rag2−/− mice were analyzed (c-Junfl/fl [n = 9] and c-JunΔ/Δ [n = 9], 2-tailed t test, P = .0169).

The lack of Jnk1 has been reported to be associated with an increased disease latency.21 To study tumor cell–intrinsic characteristics in vivo, we transplanted established cell lines via tail-vein injection into Rag2−/− mice. This procedure inflicts a rapidly evolving leukemia, which can be readily monitored in Rag2−/− mice because they lack all lymphoid cells except natural killer cells. After injection of c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/− (c-JunΔ/Δ) and c-Junfl/fl stable cell lines via the tail vein, the mice developed leukemia with infiltrations of leukemic cells in BM, spleen, liver, and lymph nodes (data not shown). As summarized in Figure 1C, leukemia evolved with a significantly enhanced latency in mice that had received c-JunΔ/Δ cells. The signs of disease were attenuated, as evident from the reduced spleen weight of mice suffering from a c-Jun–deficient leukemia (Figure 1D).

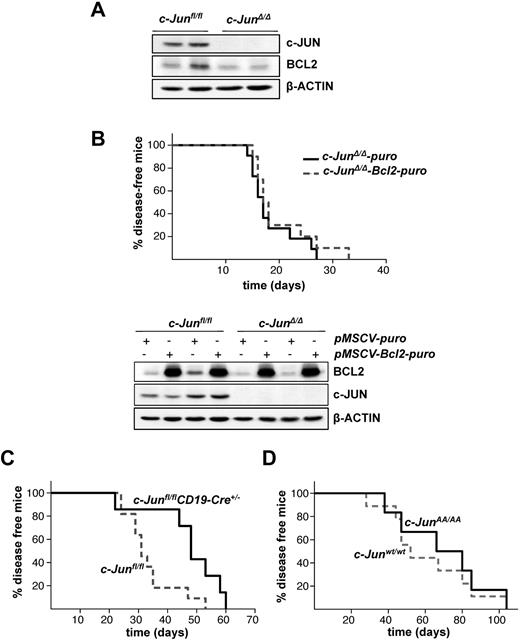

JNK1 and c-JUN act via different pathways in promoting BCR-ABL–induced leukemia

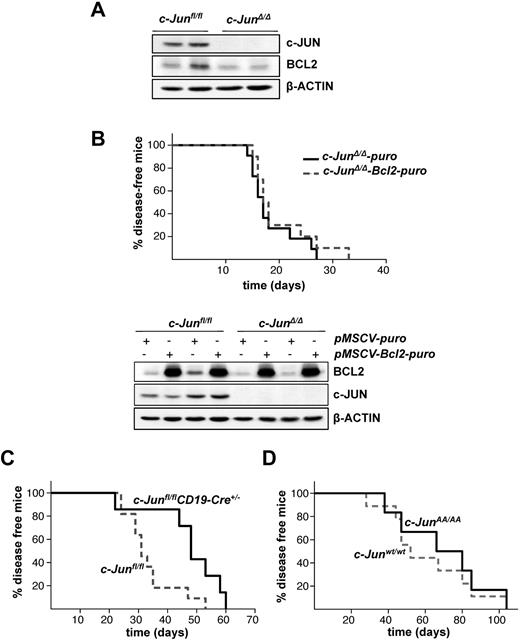

The lack of Jnk1 in BCR-ABL–transformed cells was reported to decrease BCL2 expression, which was verified as the major cause for the reduced malignancy of Jnk1−/− cells on BCR-ABL transformation. Transgenic expression of Bcl2 in these cells rescued apoptosis and restored tumors.21 BCL2 protein expression was also reduced in c-JunΔ/Δ cells compared with c-Junfl/fl control cells (Figure 2A). To explore whether the reduction in BCL2 expression accounts for a delayed tumorigenesis in c-JunΔ/Δ cells, we expressed BCL2, encoded by a retrovirus, in BCR-ABL–transformed c-JunΔ/Δ and c-Junfl/fl cells (Figure 2B bottom panel). Leukemia formation was then investigated by injecting these cells into Rag2−/− animals via the tail vein. Surprisingly, disease latency was unaffected whether we injected c-JunΔ/Δ cells or c-Junfl/fl cells expressing low or high levels of BCL2 (Figure 2B top panel and supplemental Figure 1A, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Enforced BCL2 expression does not alter c-JUN–deficient leukemogenesis. (A) Protein levels of c-JUN and BCL2 in c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δp185BCR-ABL-transformed cells. β-ACTIN served as the loading control. (B) 1 × 105 leukemic c-JunΔ/Δ B cells, transduced either with pMSCV-puro or pMSCV-Bcl2-puro, were injected IV into Rag2−/− mice (n = 11 and n = 13, respectively; mean survival, 17 vs 17.5 days in mice injected with c-JunΔ/Δ-puro and c-JunΔ/Δ-Bcl2-puro cells, P = .3552) (top panel). Immunoblot analysis shows the enforced expression of BCL2 on a pMSCV-Bcl2-puro retrovirus infection in c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ cells. β-ACTIN served as the loading control (bottom panel). (C) Injection of c-Junfl/fl (n = 11) and c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/− (n = 7) newborn mice with a replication-deficient Ab-MuLV–encoding retrovirus resulted in B-lymphoid leukemia/lymphoma (mean survival 31 vs 48 days in c-Junfl/fl and c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/− mice, respectively, P = .0173). (D) Injection of c-Junwt/wt (n = 9) and c-JunAA/AA (n = 6) newborn mice with a replication-deficient Ab-MuLV–encoding retrovirus resulted in B-lymphoid leukemia/lymphoma (mean survival 52 vs 73 days in c-Junwt/wt and c-JunAA/AA mice, respectively, P = .6168).

Enforced BCL2 expression does not alter c-JUN–deficient leukemogenesis. (A) Protein levels of c-JUN and BCL2 in c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δp185BCR-ABL-transformed cells. β-ACTIN served as the loading control. (B) 1 × 105 leukemic c-JunΔ/Δ B cells, transduced either with pMSCV-puro or pMSCV-Bcl2-puro, were injected IV into Rag2−/− mice (n = 11 and n = 13, respectively; mean survival, 17 vs 17.5 days in mice injected with c-JunΔ/Δ-puro and c-JunΔ/Δ-Bcl2-puro cells, P = .3552) (top panel). Immunoblot analysis shows the enforced expression of BCL2 on a pMSCV-Bcl2-puro retrovirus infection in c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ cells. β-ACTIN served as the loading control (bottom panel). (C) Injection of c-Junfl/fl (n = 11) and c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/− (n = 7) newborn mice with a replication-deficient Ab-MuLV–encoding retrovirus resulted in B-lymphoid leukemia/lymphoma (mean survival 31 vs 48 days in c-Junfl/fl and c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/− mice, respectively, P = .0173). (D) Injection of c-Junwt/wt (n = 9) and c-JunAA/AA (n = 6) newborn mice with a replication-deficient Ab-MuLV–encoding retrovirus resulted in B-lymphoid leukemia/lymphoma (mean survival 52 vs 73 days in c-Junwt/wt and c-JunAA/AA mice, respectively, P = .6168).

To investigate further whether JNK1 and c-JUN act in a signaling cascade independently of BCL2, we made use of c-JunAA/AA mice harboring point mutations at the critical serine sites subjected to phosphorylation by JNK. Newborn c-JunAA/AA mice and the appropriate controls were infected IP with the replication-deficient retrovirus Ab-MuLV encoding v-Abl. As an additional control, we used c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/− and compared them with c-Junfl/fl mice. Ab-MuLV infects B-lymphoid precursors and induces a slowly evolving pro–B-cell leukemia in mice. Therefore, in contrast to leukemia inflicted by transplanting readily established cell lines by IV injection, disease development is much slower and is induced with delayed kinetics. As depicted in Figure 2C, c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/− mice developed leukemia with a significantly enhanced latency compared with c-Junfl/fl mice, which is clearly in agreement with the tumor-promoting effect of c-JUN. However, no effect was observed when we compared c-JunAA/AA mice with control animals (Figure 2D). The slight difference in latency between the control mice in these 2 experiments was caused by minor background differences in the animals. In agreement with this, we failed to detect any alteration in the outgrowth of c-JunAA/AA and control p185BCR-ABL–transformed cell lines (data not shown). These data indicate that JNK1 and c-JUN promote BCR-ABL–driven tumorigenesis independently using different mechanisms.

c-Jun deficient cells show a proliferative defect

AP-1 members regulate survival, differentiation and proliferation.15 Because the enforced expression of BCL2 did not accelerate leukemogenesis in c-JunΔ/Δ cells, we next investigated cell growth of BCR-ABL–transformed c-JunΔ/Δ cells. Six individually derived, stable cell lines lacking c-Jun and corresponding control cell lines were generated. [3H]-thymidine incorporation assays and growth curves showed a significant difference in the proliferation of c-JunΔ/Δ and c-Junfl/fl cells. c-JunΔ/Δ cells expanded significantly more slowly (Figure 3A-B). This was also evident from the DNA content of asynchronously proliferating cells: c-JunΔ/Δ cells showed a significantly increased proportion of cells in the G1 phase and a decreased proportion in the S phase (Figure 3C). To monitor tumor growth in vivo, we made use of Nu/Nu mice. Tumor cells were injected subcutaneously to allow monitoring of tumor growth. These in vivo experiments recapitulated the in vitro observations. c-JunΔ/Δ tumors evolved significantly more slowly in Nu/Nu mice. The experiment was terminated after 10 days, when the first tumor reached 1 cm in diameter. At that time, the weight of the c-JunΔ/Δ tumors compared with the c-Junfl/fl tumors was significantly lower (Figure 3D).

c-JunΔ/Δp185BCR-ABL–transformed cell lines demonstrate a proliferative defect. (A) [3H]-thymidine incorporation of fetal liver–derived c-Junfl/fl (n = 3) and c-JunΔ/Δ (n = 4; 2-tailed t test, P = .0142) p185BCR-ABL-transformed cell lines. (B) 1 × 105p185BCR-ABL-transformed c-Junfl/fl (n = 3) and c-JunΔ/Δ cells (n = 3) were plated and total cell numbers were determined after 48, 96, and 144 hours. (C) Cell-cycle profiles of c-Junfl/fl (n = 5) and c-JunΔ/Δ (n = 4) cells (2-tailed t test, G1 phase, P = .0333; S phase, P = .0173) gated on living cells. One representative set of data is depicted. (D) Tumor weights of Nu/Nu mice that were subcutaneously injected with 1 × 106c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ leukemic cells. Three independent cell lines for each cell type were injected into 9 mice (2-tailed t test, P = .0007). (E) Injection of c-Junfl/flp53−/− (n = 11) and c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/−p53−/− (n = 7) newborn mice with a replication-deficient Ab-MuLV–encoding retrovirus resulted in B-lymphoid leukemia/lymphoma (mean survival, 31 vs 44 days in c-Junfl/flp53−/− and c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/−p53−/− mice, P = .0213).

c-JunΔ/Δp185BCR-ABL–transformed cell lines demonstrate a proliferative defect. (A) [3H]-thymidine incorporation of fetal liver–derived c-Junfl/fl (n = 3) and c-JunΔ/Δ (n = 4; 2-tailed t test, P = .0142) p185BCR-ABL-transformed cell lines. (B) 1 × 105p185BCR-ABL-transformed c-Junfl/fl (n = 3) and c-JunΔ/Δ cells (n = 3) were plated and total cell numbers were determined after 48, 96, and 144 hours. (C) Cell-cycle profiles of c-Junfl/fl (n = 5) and c-JunΔ/Δ (n = 4) cells (2-tailed t test, G1 phase, P = .0333; S phase, P = .0173) gated on living cells. One representative set of data is depicted. (D) Tumor weights of Nu/Nu mice that were subcutaneously injected with 1 × 106c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ leukemic cells. Three independent cell lines for each cell type were injected into 9 mice (2-tailed t test, P = .0007). (E) Injection of c-Junfl/flp53−/− (n = 11) and c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/−p53−/− (n = 7) newborn mice with a replication-deficient Ab-MuLV–encoding retrovirus resulted in B-lymphoid leukemia/lymphoma (mean survival, 31 vs 44 days in c-Junfl/flp53−/− and c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/−p53−/− mice, P = .0213).

In hepatocytes, c-JUN accelerates tumor formation by antagonizing the proapoptotic activity of p53.17 A role for p53 has been established for BCR-ABL–induced disease previously. BCR-ABL–induced transformation and leukemia occur more rapidly on a p53−/− background because the cells do not have to overcome p53-induced apoptosis and crisis induced by oncogenic stress.38 To determine the possible involvement of c-JUN in this mechanism and to find out whether c-JUN is required to counteract the proapoptotic effects of p53 during transformation, we crossed c-Junfl/fl and c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/− mice with p53−/− mice and then assessed leukemia formation by challenging newborn c-Junfl/flp53−/− and c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/−p53−/− mice with Ab-MuLV. As depicted in Figure 2E, p53 deficiency did not change the disease latency that was observed upon transformation of c-Junfl/fl and c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/− mice. This experiment led us to conclude that c-JUN is not required to antagonize p53, as is observed in hepatocytes, but rather suggests an involvement of c-JUN in growth control in p185BCR-ABL–positive tumor cells.

Transformed c-JunΔ/Δ cells down-regulate the expression of the cell-cycle kinase CDK6

To determine which cell-cycle components are altered in c-JunΔ/Δ cell lines, we compared genome-wide gene expression patterns of c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ cells using microarray analysis. Microarray results are summarized in a scatter plot in supplemental Figure 2A and in supplemental Tables 1-2. Expression of 31 transcripts was found to be down-regulated at least 2-fold in c-JunΔ/Δ cells. These transcripts included the cell-cycle kinase Cdk6 and the cell-cycle inhibitor and tumor suppressor p16INK4a. Microarray data for these genes were confirmed by Western blot analysis (Figure 4A). Loss of CDK6 was restricted to stable c-JunΔ/Δ cell lines and was not observed in p185BCR-ABL–transformed c-JunAA/AA cells, supporting the independence of JNK phosphorylation (Figure 4B). The protein expression of CDK6 steadily declined after 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks of the initial transformation event by retroviral infection with p185BCR-ABL in c-JunΔ/Δ cells (Figure 4C). This constant protein reduction was correlated with a decrease in the proliferative capacity of the cells (Figure 4D). After 2 weeks, the cell cultures already consisted of more than 95% GFP+ and therefore BCR-ABL+ cells; therefore, a decreasing contamination with nontransformed cells can be ruled out. Quantitative PCR experiments revealed that the reduction of the CDK6 protein was accompanied by a loss of Cdk6 mRNA (Figure 4E). When we compared Cdk6 mRNA levels in BCR-ABL–transformed wild-type and c-JunΔ/Δ cells side by side, we found that mRNA levels developed in opposite directions. Whereas Cdk6 mRNA was up-regulated in transformed wild-type cells, a significant decline was observed in cells lacking c-JUN (Figure 4E).

CDK6 protein levels are down-regulated in c-JunΔ/Δp185BCR-ABL–transformed cell lines. (A) Immunoblot analysis for CDK6, CDK4, CDK2, CYCLIN D2, CYCLIN D3, p16INK4a, p15INK4b, p21, and p27 protein expression in c-Junfl/fl- and c-JunΔ/Δp185BCR-ABL–transformed cells. β-ACTIN served as the loading control. (B) Immunoblot analysis for c-JUN and CDK6 protein expression in c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ (top panel) and c-Junwt/wt and c-JunAA/AA (bottom panel) p185BCR-ABL–transformed cells. β-ACTIN served as the loading control. (C) c-JUN and CDK6 protein levels of c-JunΔ/Δ and c-Junfl/fl cell lines after 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks of transformation. β-ACTIN served as the loading control. One representative set of data is depicted. (D) [3H]-thymidine incorporation of the same cell lines was measured (n = 3; 2-tailed t test: c-Junfl/fl vs c-JunΔ/Δ 6 weeks, P = .002; c-Junfl/fl vs c-JunΔ/Δ 8 weeks, P = .0016). (E) Cdk6 mRNA levels of c-JunΔ/Δ and c-Junfl/fl cells 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks after p185BCR-ABL transformation were analyzed by quantitative PCR (n = 3; 2-tailed t test: c-Junfl/fl 2 weeks vs c-JunΔ/Δ 2 weeks, P = .0385; c-Junfl/fl 2 weeks vs c-Junfl/fl 8 weeks, P = .0293; c-JunΔ/Δ 2 weeks vs c-JunΔ/Δ 8 weeks, P = .0024). The fold change compared with c-JunΔ/Δ 2-week Cdk6 mRNA level is shown. Results were normalized by comparison with their Gapdh mRNA expression.

CDK6 protein levels are down-regulated in c-JunΔ/Δp185BCR-ABL–transformed cell lines. (A) Immunoblot analysis for CDK6, CDK4, CDK2, CYCLIN D2, CYCLIN D3, p16INK4a, p15INK4b, p21, and p27 protein expression in c-Junfl/fl- and c-JunΔ/Δp185BCR-ABL–transformed cells. β-ACTIN served as the loading control. (B) Immunoblot analysis for c-JUN and CDK6 protein expression in c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ (top panel) and c-Junwt/wt and c-JunAA/AA (bottom panel) p185BCR-ABL–transformed cells. β-ACTIN served as the loading control. (C) c-JUN and CDK6 protein levels of c-JunΔ/Δ and c-Junfl/fl cell lines after 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks of transformation. β-ACTIN served as the loading control. One representative set of data is depicted. (D) [3H]-thymidine incorporation of the same cell lines was measured (n = 3; 2-tailed t test: c-Junfl/fl vs c-JunΔ/Δ 6 weeks, P = .002; c-Junfl/fl vs c-JunΔ/Δ 8 weeks, P = .0016). (E) Cdk6 mRNA levels of c-JunΔ/Δ and c-Junfl/fl cells 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks after p185BCR-ABL transformation were analyzed by quantitative PCR (n = 3; 2-tailed t test: c-Junfl/fl 2 weeks vs c-JunΔ/Δ 2 weeks, P = .0385; c-Junfl/fl 2 weeks vs c-Junfl/fl 8 weeks, P = .0293; c-JunΔ/Δ 2 weeks vs c-JunΔ/Δ 8 weeks, P = .0024). The fold change compared with c-JunΔ/Δ 2-week Cdk6 mRNA level is shown. Results were normalized by comparison with their Gapdh mRNA expression.

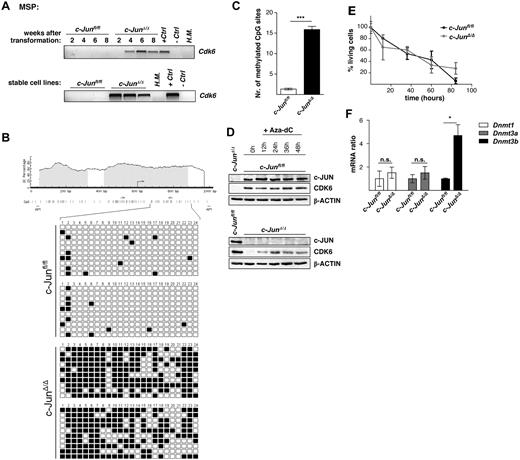

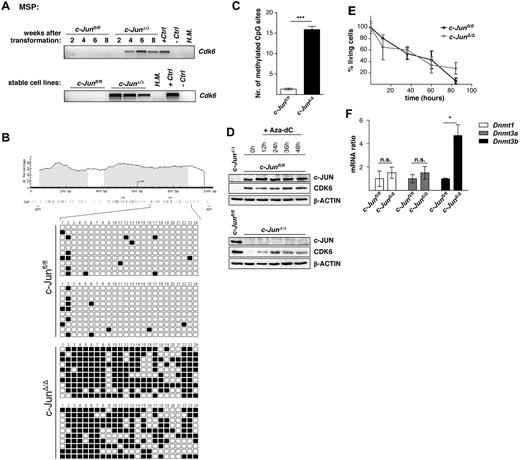

Lack of c-JUN leads to methylation within the 5′ region of Cdk6 in p185BCR-ABL–transformed cells

To determine whether epigenetic changes are responsible for the down-regulation of CDK6 in p185BCR-ABL–transformed cells, we developed MSP and bisulfite genomic sequencing assays for DNA methylation analysis of the 5′ region of the Cdk6 gene. As analyzed by MSP, the time-dependent reduction of Cdk6 mRNA coincided with DNA methylation within the 5′ region of Cdk6 (Figure 5A top panel). Whereas Cdk6 methylation was detected in all stable cell lines lacking c-JUN, the c-Junfl/fl cells were not methylated for this gene (Figure 5A bottom panel). Results obtained with MSP analysis were confirmed by bisulfite genomic sequencing of the Cdk6 5′ region in c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ cells. In total, 20 cell clones of each genotype were sequenced (Figure 5B-C). Further confirmation was obtained when we treated the BCR-ABL–transformed c-JunΔ/Δ cells with the demethylating agent Aza-dC for 48 hours. As expected, Aza-dC–induced demethylation of DNA resulted in reexpression of CDK6 by 12 hours after treatment (Figure 5D), and most of the cells had entered the G0/G1 phase (supplemental Figure 3A) and began to die 12 hours after Aza-dC addition (Figure 5E). Analyzing the mRNA levels of DNA methyltransferases (Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b) in c-JunΔ/Δ and c-Junfl/fl cells using real-time RT-PCR showed a significantly higher amount of Dnmt3b mRNA in c-JunΔ/Δ cells compared with c-Junfl/fl cells (Figure 5F).

The 5′ region of Cdk6 is methylated in c-JunΔ/Δ cells. (A) Hypermethylation in c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ cells after 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks of p185BCR-ABL transformation (top panel) and in stable c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ cell lines (bottom panel), was detected by MSP analysis. A visible PCR product indicates the presence of methylated alleles. H.M. indicates BM of a healthy mouse; +Ctrl, control for methylated samples; −Ctrl, control for unmethylated samples. (B) Location of CpG islands within the 5′ region of Cdk6 (gray boxes). CpG sites are shown as horizontal bars, MSP primer-binding sites are shown as arrows, and AP1-binding sites are shown as vertical bars (black). Twenty-four CpG sites were analyzed by bisulfite genomic sequencing in 2 c-Junfl/fl and in 2 c-JunΔ/Δ cell lines. In total, 20 clones of each genotype were sequenced. Small black boxes indicate methylated CpG sites and white boxes indicate unmethylated CpG sites. (C) A statistically significant difference between Cdk6 methylation in c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ cells was observed (n = 20; 2-tailed t test, P < .0001). (D) Immunoblot for c-JUN and CDK6 of c-JunΔ/Δ and c-Junfl/fl cells after 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours of Aza-dC treatment. β-ACTIN served as the loading control. One representative set of data is depicted. (E) Percentage of living cells 12, 36, 60, and 84 hours after Aza-dC treatment of c-JunΔ/Δ and c-Junfl/fl leukemic cells. Viability was analyzed by propidium iodide staining. (F) Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b mRNA levels of c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ cells were analyzed by RT-PCR (n = 3; 2-tailed t test, Dnmt3b, P = .016). The fold change compared with c-Junfl/fl mRNA levels is shown. Results were normalized by comparison with their Gapdh mRNA expression.

The 5′ region of Cdk6 is methylated in c-JunΔ/Δ cells. (A) Hypermethylation in c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ cells after 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks of p185BCR-ABL transformation (top panel) and in stable c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ cell lines (bottom panel), was detected by MSP analysis. A visible PCR product indicates the presence of methylated alleles. H.M. indicates BM of a healthy mouse; +Ctrl, control for methylated samples; −Ctrl, control for unmethylated samples. (B) Location of CpG islands within the 5′ region of Cdk6 (gray boxes). CpG sites are shown as horizontal bars, MSP primer-binding sites are shown as arrows, and AP1-binding sites are shown as vertical bars (black). Twenty-four CpG sites were analyzed by bisulfite genomic sequencing in 2 c-Junfl/fl and in 2 c-JunΔ/Δ cell lines. In total, 20 clones of each genotype were sequenced. Small black boxes indicate methylated CpG sites and white boxes indicate unmethylated CpG sites. (C) A statistically significant difference between Cdk6 methylation in c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ cells was observed (n = 20; 2-tailed t test, P < .0001). (D) Immunoblot for c-JUN and CDK6 of c-JunΔ/Δ and c-Junfl/fl cells after 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours of Aza-dC treatment. β-ACTIN served as the loading control. One representative set of data is depicted. (E) Percentage of living cells 12, 36, 60, and 84 hours after Aza-dC treatment of c-JunΔ/Δ and c-Junfl/fl leukemic cells. Viability was analyzed by propidium iodide staining. (F) Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b mRNA levels of c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ cells were analyzed by RT-PCR (n = 3; 2-tailed t test, Dnmt3b, P = .016). The fold change compared with c-Junfl/fl mRNA levels is shown. Results were normalized by comparison with their Gapdh mRNA expression.

Loss of CDK6 in BCR-ABL–transformed cells recapitulates the phenotype of c-Jun deficiency

We next investigated whether the loss of CDK6 accounts for the reduced proliferation of BCR-ABL–transformed c-JunΔ/Δ cells, provoking the increased disease latency. To study the contribution of CDK6 to BCR-ABL–induced tumor formation, we used Cdk6−/− mice. Because no information on a potential role of CDK6 in B-lymphoid development was available, we first monitored the emergence of individually defined B-cell stages. Figure 6A shows typical examples of FACS blots; a summary and a statistical analysis of 4 mice of each genotype is given in Figure 6B. Briefly, Cdk6−/− mice had significantly elevated levels of pre–pro-B cells. The total cell number of peripheral mature B cells was unaltered, indicating that this partial block was compensated for in vivo. Mature Cdk6−/− B lymphocytes responded equally well to mitogenic stimuli compared with control cells (supplemental Figure 3A). We next transformed fetal liver–derived Cdk6−/− cells and wild-type controls with a pMSCV-p185BCR-ABL-IRES-GFP retrovirus. GFP+CD43+CD19+B220+ colonies and cell lines were obtained with equal frequencies (supplemental Figure 3B). However, a significant difference became obvious in a [3H]-thymidine incorporation assay; a decreased proliferation was also documented by growth curves (Figure 6B-C). These data point toward an essential, nonredundant role for CDK6 in transformed B cells, which is in contrast to the observation in nontransformed, mature B cells, in which the lack of CDK6 did not impair proliferation (supplemental Figure 4A).

CDK6 advances p185BCR-ABL–induced leukemia. (A) Top panel shows the percentages of B cells of fraction A-C in the BM (left panel) and fraction D-F in the spleens (right panel) of Cdk6−/− mice compared with Cdk6+/+ mice as analyzed by FACS (n = 3; fraction A: 2-tailed t test, P = .0379). In the bottom panel, dot blots indicate the percentages of gated CD43+/B220+ (first panel) and CD43+/B220+/CD19−/BP-1− for fraction A, CD43+/B220+/CD19+/BP-1− for fraction B, and CD43+/B220+/CD19+/BP-1+ for fraction C (second panel) in the BM and gated CD43−/B220+ (third panel) and CD43−/B220+/IgD−/IgM− for fraction D, CD43−/B220+/IgD+/IgM− for fraction E, and CD43−/B220+/IgD−/IgM− for fraction F (fourth panel) in the spleens of Cdk6−/− and Cdk6+/+ mice. (B) [3H]-thymidine incorporation into fetal liver–derived Cdk6+/+ and Cdk6−/−p185BCR-ABL–transformed cell lines was measured (n = 6; 2-tailed t test, P < .0001). (C) Cells (1 × 105) of p185BCR-ABL–transformed Cdk6+/+ (n = 3) and Cdk6−/− (n = 3) mice were plated and total cell numbers were determined after 48, 96, and 144 hours. (D) Injection of Cdk6+/+ (n = 7), Cdk6+/− (n = 23), and Cdk6−/− (n = 16) newborn mice with a replication-deficient Ab-MuLV–encoding retrovirus resulted in B-lymphoid leukemia/lymphoma (mean survival 63 vs 62 vs 120 days in Cdk6+/+, Cdk6+/−, and Cdk6−/− mice, respectively; P < .0001 for Cdk6+/+ vs Cdk6−/−). (E) The infiltration rates of CD19+/CD43+ cells in the spleens of diseased mice were analyzed by FACS (n = 6; 2-tailed t test, P = .103).

CDK6 advances p185BCR-ABL–induced leukemia. (A) Top panel shows the percentages of B cells of fraction A-C in the BM (left panel) and fraction D-F in the spleens (right panel) of Cdk6−/− mice compared with Cdk6+/+ mice as analyzed by FACS (n = 3; fraction A: 2-tailed t test, P = .0379). In the bottom panel, dot blots indicate the percentages of gated CD43+/B220+ (first panel) and CD43+/B220+/CD19−/BP-1− for fraction A, CD43+/B220+/CD19+/BP-1− for fraction B, and CD43+/B220+/CD19+/BP-1+ for fraction C (second panel) in the BM and gated CD43−/B220+ (third panel) and CD43−/B220+/IgD−/IgM− for fraction D, CD43−/B220+/IgD+/IgM− for fraction E, and CD43−/B220+/IgD−/IgM− for fraction F (fourth panel) in the spleens of Cdk6−/− and Cdk6+/+ mice. (B) [3H]-thymidine incorporation into fetal liver–derived Cdk6+/+ and Cdk6−/−p185BCR-ABL–transformed cell lines was measured (n = 6; 2-tailed t test, P < .0001). (C) Cells (1 × 105) of p185BCR-ABL–transformed Cdk6+/+ (n = 3) and Cdk6−/− (n = 3) mice were plated and total cell numbers were determined after 48, 96, and 144 hours. (D) Injection of Cdk6+/+ (n = 7), Cdk6+/− (n = 23), and Cdk6−/− (n = 16) newborn mice with a replication-deficient Ab-MuLV–encoding retrovirus resulted in B-lymphoid leukemia/lymphoma (mean survival 63 vs 62 vs 120 days in Cdk6+/+, Cdk6+/−, and Cdk6−/− mice, respectively; P < .0001 for Cdk6+/+ vs Cdk6−/−). (E) The infiltration rates of CD19+/CD43+ cells in the spleens of diseased mice were analyzed by FACS (n = 6; 2-tailed t test, P = .103).

To assess tumor formation in vivo, we injected a replication-incompetent retrovirus encoding Ab-MuLV in newborn mice, thereby inducing a slowly emerging lymphoid leukemia. The outcome of the experiment is summarized in Figure 6D. Strikingly, Cdk6−/− animals developed disease significantly later and survived the oncogenic challenge up to 5 months, whereas all Cdk6+/+ and Cdk6+/− mice succumbed to leukemia within ∼ 2 months. A slightly decreased infiltration of the spleen with leukemic cells was found in Cdk6−/− mice, but this difference did not meet the criteria for being statistically significant (Figure 6E). This experiment highlighted a nonredundant role of CDK6 as a tumor promoter for p185BCR-ABL–induced B-cell leukemia. In summary, these data revealed a nonredundant tumor-promoting role for CDK6 in p185BCR-ABL–driven leukemogenesis.

Reexpression of CDK6 reconstitutes proliferation in c-JunΔ/Δ cells

To define whether the loss of CDK6 accounts for the decreased proliferation and tumor formation of BCR-ABL–transformed c-JunΔ/Δ cells, we reexpressed CDK6 with a pMSCV-Cdk6-puro retrovirus in c-JunΔ/Δ cells (Figure 7A). As depicted in Figure 7B, c-JunΔ/Δ cells proliferated significantly faster after CDK6 expression compared with control cells that had been infected with the empty vector. In addition, the proportion of these cells in the G1 and S phases showed no significant difference compared with c-Junfl/fl cells (Figure 7C). Tumor formation in Nu/Nu mice was assessed with c-JunΔ/Δ-Cdk6-puro cells compared with c-JunΔ/Δ cells and in this in vivo experiment, an increased tumor size of c-JunΔ/Δ-Cdk6-puro cells was detected (Figure 7D). We concluded that reexpression of CDK6 in c-JunΔ/Δ cells restores proliferation to levels observed in wild-type control cells and accelerates tumor formation in vivo.

Reexpression of CDK6 in c-JunΔ/Δ cells rescues the proliferative defect. (A) Immunoblot analysis of the enforced expression of CDK6 with a pMSCV-Cdk6-puro retrovirus in c-JunΔ/Δ cells. β-ACTIN served as the loading control. (B) [3H]-thymidine incorporation in c-Junfl/fl, c-JunΔ/Δ-puro, and c-JunΔ/Δ-Cdk6-puro cell lines (n = 3; 2-tailed t test, c-Junfl/fl vs c-JunΔ/Δ-puro, P = .0053; c-JunΔ/Δ-puro vs c-JunΔ/Δ-Cdk6-puro, P = .0029). (C) Cell-cycle profiles of c-Junfl/fl (n = 5) and c-JunΔ/Δ-Cdk6-puro (n = 4) cells gated on living cells. One representative set of data is depicted. (D) 1 × 106c-Junfl/fl, c-JunΔ/Δ-puro, and c-JunΔ/Δ-Cdk6-puro p185BCR-ABL–transformed cells were injected subcutaneously into Nu/Nu mice. Two independent cell lines for each cell type were injected into mice (2-tailed t test, c-Junfl/fl [n = 17] vs c-JunΔ/Δ-puro [n = 17], P < .0001; c-JunΔ/Δ-puro [n = 17] vs c-JunΔ/Δ-Cdk6-puro [n = 11], P = .0017).

Reexpression of CDK6 in c-JunΔ/Δ cells rescues the proliferative defect. (A) Immunoblot analysis of the enforced expression of CDK6 with a pMSCV-Cdk6-puro retrovirus in c-JunΔ/Δ cells. β-ACTIN served as the loading control. (B) [3H]-thymidine incorporation in c-Junfl/fl, c-JunΔ/Δ-puro, and c-JunΔ/Δ-Cdk6-puro cell lines (n = 3; 2-tailed t test, c-Junfl/fl vs c-JunΔ/Δ-puro, P = .0053; c-JunΔ/Δ-puro vs c-JunΔ/Δ-Cdk6-puro, P = .0029). (C) Cell-cycle profiles of c-Junfl/fl (n = 5) and c-JunΔ/Δ-Cdk6-puro (n = 4) cells gated on living cells. One representative set of data is depicted. (D) 1 × 106c-Junfl/fl, c-JunΔ/Δ-puro, and c-JunΔ/Δ-Cdk6-puro p185BCR-ABL–transformed cells were injected subcutaneously into Nu/Nu mice. Two independent cell lines for each cell type were injected into mice (2-tailed t test, c-Junfl/fl [n = 17] vs c-JunΔ/Δ-puro [n = 17], P < .0001; c-JunΔ/Δ-puro [n = 17] vs c-JunΔ/Δ-Cdk6-puro [n = 11], P = .0017).

Discussion

We have shown that the AP-1 transcription factor c-JUN promotes BCR-ABL–induced leukemogenesis by maintaining the expression of the cell-cycle kinase CDK6. c-JUN is required to protect the CpG island in the 5′ region of Cdk6 from being methylated. We defined a novel mechanism for how AP-1 transcription factors that are commonly up-regulated in transformed cells contribute to tumorigenesis. Furthermore, we defined for the first time a tumor-promoting role for CDK6 in B-lymphoid leukemogenesis.

Although c-JUN has unequivocally been implicated in the regulation of apoptosis during tumorigenesis,17 these effects have been excluded for BCR-ABL–induced B-lymphoid leukemogenesis. Neither the enforced expression of BCL2 nor the lack of p53 counteracted or influenced the effects on disease latency that occurred in the absence of c-JUN during leukemia progression. This is in contrast to the situation in Jnk1−/− cells, in which the enforced expression of BCL2 reconstituted leukemogenesis.21 This also led us to conclude that JNK1 exerts its effects independently of c-JUN, which was further confirmed by investigating c-JunAA/AA mice. How JNK1 regulates BCL2 expression and promotes survival independently of c-JUN remains to be determined.

We cannot rule out that c-JUN exerts a survival function during the initial transformation event. Similar to Jnk1−/− cells, c-JunΔ/Δ cells gave rise to significantly reduced colony numbers when plated in growth factor–free methylcellulose. This is in contrast to our observations in Cdk6−/− cells, which display unimpaired colony formation. Obviously, transformation induces rewiring of signaling pathways and changes the signaling network required for survival and proliferation. Therefore, factors that are required within the initial transformation process may become irrelevant for tumor-cell maintenance. This has been recently demonstrated for the transcription factor STAT3.39

Interestingly, nontransformed B-lymphoid cells lacking c-JUN express regular levels of CDK6. Only upon transformation with the BCR-ABL oncogene does the 5′ region of Cdk6 become methylated, if not protected and prevented, by c-JUN. Hundreds of possibly epigenetically silenced genes exist in individual tumors. Whereas a selection for stochastic events certainly exists and selects for dominant tumor clones, it is unlikely that all of these events arise in a random fashion. Rather, the current model suggests that the existence of multiple epigenetically silenced genes reflects a general program of epigenetic control abnormalities. These early epigenetic silencing events could represent primary alterations induced by the initial transformation event. Our data support this model, because the BCR-ABL–induced transformation consistently provoked the silencing of the Cdk6 gene by DNA methylation. Alternatively, one might suggest that c-JUN is exclusively required for CDK6 expression. In the absence of c-JUN, Cdk6 transcription comes to a stop, which then induces DNA methylation. The fact that we found increased mRNA levels of the DNA methyltransferases Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b in BCR-ABL–transformed c-JunΔ/Δ cells suggests a general mechanism not specific for Cdk6. It remains to be determined which of the genes found to be down-regulated in the absence of c-JUN in transformed cells have also undergone promoter methylation. Interestingly, the de novo methyltransferase Dnmt3b was significantly high in the absence of c-JUN. The enzymes DNMT3a and DNMT3b account for the somatic methylation pattern during embryogenesis and favor semi- and unmethylated DNA substrates.40,41 In contrast, DNMT1 specifies copying existing methylation patterns.40,42

What singles out CDK6 silencing is the fact that CDK6 contributes significantly to the tumor-promoting role of c-JUN. The reduced growth of BCR-ABL–transformed c-JunΔ/Δ cells can be largely overridden by the enforced expression of CDK6, which reconstitutes the proliferative ability of the cells and thereby enhances tumor formation in Nu/Nu mice. It is also noteworthy that the expression of CDK6 is subject to regulation not only by c-JUN, but also by the related protein JUNB. We have recently found that JUNB suppresses the transcription of Cdk6 in BCR-ABL–transformed cells.35 As a consequence, the loss or down-regulation of JUNB—as observed in human myeloid and B-lymphoid malignancies—provokes increased CDK6 expression. In summary, a shift of AP-1 composition occurs in B-lymphoid malignancies: c-JUN becomes up-regulated whereas JUNB remains constant or gets down-regulated.13 Based on these alterations of AP-1 expression pattern, one might therefore expect an overall increased expression of CDK6 in B-lymphoid malignancies. Indeed, enhanced CDK6 protein expression has been documented in lymphoma and leukemia in humans.43-46 In particular, several reports have documented chromosomal translocations in patients suffering from B-lymphoid malignancies involving CDK6. In these patients, the aberrant and increased expression of CDK6 had been proposed to represent a cause and/or driving force for the B-cell disease.47-49 In addition, a recent study describes a down-regulation of the microRNA hsa-miR-124a during acute lymphoblastic leukemia, resulting in an up-regulation of CDK6.50 Nevertheless, it remained unclear until now whether the enforced expression of CDK6 represents a bystander alteration or is indeed a driving force in B-lymphoid leukemogenesis. We provide the first evidence for the tumor-promoting role by showing that the absence of CDK6 drastically prolonged tumorigenesis in vivo. CDK6 advanced the growth of transformed B-lymphoid cells. p185BCR-ABL–induced leukemia was significantly delayed in Cdk6−/− mice, and the lifespan of the affected animals nearly doubled. Therefore, in B-lymphoid malignancies, CDK6 exerts a unique and nonredundant tumor-promoting role. CDK6 comes into this privileged position only upon BCR-ABL–induced transformation, after which it takes over the dominant role during the G1 phase of the cell cycle. It is tempting to speculate that this alteration might be the direct consequence of the changed AP-1 expression profiles and may result from the combination of low or missing JUNB combined with elevated c-JUN expression.

In summary, we provide first insights into a role for the AP-1 transcription factors as modulators of epigenetic reprogramming occurring in transformed cells. Our data reveal a linear axis for c-JUN and CDK6 in the regulation of proliferation in transformed B-lymphoid cells. In this scenario, CDK6 occupies a privileged and unique position and exerts a nonredundant, tumor-promoting role.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Udo Losert and the staff of the Biomedical Research Institute, Medical University of Vienna, as well as Gabriele Schöppl and the mouse facility of the Institute of Pharmacology, Medical University of Vienna, for taking excellent care of the mice. We are grateful to Gerda Egger, Latifa Bakiri, Robert Eferl, Denise Barlow, and Michael Freissmuth for valuable discussions. We thank Erwin F. Wagner for providing essential reagents and mice.

This work was supported by the Vienna Science and Technology Fund (grants LS07-037 and LS07-019) and by the Austrian Science Foundation (grants SFB F28 and P19723 to V.S.).

Authorship

Contribution: K.K., G.H., R.G.O., R.S., E.Z.-B., C.S., O.S., W.W., E.E., A.H., M.B., S.Z.-M., M.M., and V.S. designed and performed research and analyzed data; M.M. provided vital new reagents and analytic tools; and K.K. and V.S. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Veronika Sexl, Institute of Pharmacology, and Toxicology, Veterinary University of Vienna, Veterinaerplatz 1, A-1210 Vienna, Austria; e-mail: veronika.sexl@vetmeduni.ac.at.

![Figure 1. c-JUN is involved in p185BCR-ABL-induced transformation and leukemogenesis. Colony formation assays were performed using 1 × 106 (A) JNK1+/− and JNK1−/− (n = 8; 2-tailed t test, 49.2 ± 7.9 vs 28.9 ± 4.1 colonies/107 fetal liver cells, P = .0401) and (B) c-Junfl/fl and c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/− (n = 6; 2-tailed t test, 60.5 ± 6.1 vs 27.3 ± 1.9 colonies/107 fetal liver cells, P = .0004) fetal liver cells after infection with a pMSCV-p185BCR-ABL-IRES-GFP retrovirus in growth factor–free methylcellulose. (C) Transplantation of 1 × 105 c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ cells into Rag2−/− mice. Two independent cell lines for each cell type were injected in 9 mice (mean survival, 11 vs 16 days in mice injected with c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ cells, respectively, P = .0307). (D) Spleen weights of diseased recipient Rag2−/− mice were analyzed (c-Junfl/fl [n = 9] and c-JunΔ/Δ [n = 9], 2-tailed t test, P = .0169).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/117/15/10.1182_blood-2010-07-299644/4/m_zh89991168840001.jpeg?Expires=1765103217&Signature=X6KlOnUFO3yXwI5L3GPY9o1slfzj23~FGiwnEUXEcMGioQ34NNA06miUPuIC3t6PKCAkOuyyrq2swlinDh7UHr6SC~hhC5tZeMIQ-udXgJa729EFBmEk~xAVuqvEPozdrw9m4yWkc2gGbSIRwWD803vQsN9y-EdbdsehYrKv8KPahLyEq9bkbf9kzksVgIEZZ8iNn880t9FJnNSzfTyz-y9mDYPrJX77mdVw0lWFjIJagJnfdCEDtdxBbEnbE8TgZTLCe7gM3gn83v~-L14hAfIaEdZQljo2cdYjhqARP9JhNgQTDiA4R7eaYxEgYce6d17QnuWEdFISyPde8em8Pw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 3. c-JunΔ/Δ p185BCR-ABL–transformed cell lines demonstrate a proliferative defect. (A) [3H]-thymidine incorporation of fetal liver–derived c-Junfl/fl (n = 3) and c-JunΔ/Δ (n = 4; 2-tailed t test, P = .0142) p185BCR-ABL-transformed cell lines. (B) 1 × 105 p185BCR-ABL-transformed c-Junfl/fl (n = 3) and c-JunΔ/Δ cells (n = 3) were plated and total cell numbers were determined after 48, 96, and 144 hours. (C) Cell-cycle profiles of c-Junfl/fl (n = 5) and c-JunΔ/Δ (n = 4) cells (2-tailed t test, G1 phase, P = .0333; S phase, P = .0173) gated on living cells. One representative set of data is depicted. (D) Tumor weights of Nu/Nu mice that were subcutaneously injected with 1 × 106 c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ leukemic cells. Three independent cell lines for each cell type were injected into 9 mice (2-tailed t test, P = .0007). (E) Injection of c-Junfl/flp53−/− (n = 11) and c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/−p53−/− (n = 7) newborn mice with a replication-deficient Ab-MuLV–encoding retrovirus resulted in B-lymphoid leukemia/lymphoma (mean survival, 31 vs 44 days in c-Junfl/flp53−/− and c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/−p53−/− mice, P = .0213).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/117/15/10.1182_blood-2010-07-299644/4/m_zh89991168840003.jpeg?Expires=1765103217&Signature=xfuS3e35UWzJMTvYb~0SoRK9ZOn4c~GOz35lQ1CLI1wfTfX50x5dXbhk9WqN2A3-AXze5Yvz5YeJ4IhDmOoyTGMBgPSGf71pvk29TxEzlyUEQMtp1bcHcHqHjxPnMUO7ghJjBdf7XUKsnYg~eF5BbtE80mr83Qnhn23giZ33BA0ng4shLOOBLNQey5WAXQhJ6FDGauWumQye9d~TcUw-5YzCkauIUV4O1KkLVqqzh7g344zEcTohFMW7h2rUB5ipS1~oL9ww47g8BzuAKUyEubSQwiqVKppyxaPOid-9kthMsbyJhXY4i-1e7VTTWuJMADu6ej3oKkVKuUDWnme1nw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 4. CDK6 protein levels are down-regulated in c-JunΔ/Δ p185BCR-ABL–transformed cell lines. (A) Immunoblot analysis for CDK6, CDK4, CDK2, CYCLIN D2, CYCLIN D3, p16INK4a, p15INK4b, p21, and p27 protein expression in c-Junfl/fl- and c-JunΔ/Δ p185BCR-ABL–transformed cells. β-ACTIN served as the loading control. (B) Immunoblot analysis for c-JUN and CDK6 protein expression in c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ (top panel) and c-Junwt/wt and c-JunAA/AA (bottom panel) p185BCR-ABL–transformed cells. β-ACTIN served as the loading control. (C) c-JUN and CDK6 protein levels of c-JunΔ/Δ and c-Junfl/fl cell lines after 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks of transformation. β-ACTIN served as the loading control. One representative set of data is depicted. (D) [3H]-thymidine incorporation of the same cell lines was measured (n = 3; 2-tailed t test: c-Junfl/fl vs c-JunΔ/Δ 6 weeks, P = .002; c-Junfl/fl vs c-JunΔ/Δ 8 weeks, P = .0016). (E) Cdk6 mRNA levels of c-JunΔ/Δ and c-Junfl/fl cells 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks after p185BCR-ABL transformation were analyzed by quantitative PCR (n = 3; 2-tailed t test: c-Junfl/fl 2 weeks vs c-JunΔ/Δ 2 weeks, P = .0385; c-Junfl/fl 2 weeks vs c-Junfl/fl 8 weeks, P = .0293; c-JunΔ/Δ 2 weeks vs c-JunΔ/Δ 8 weeks, P = .0024). The fold change compared with c-JunΔ/Δ 2-week Cdk6 mRNA level is shown. Results were normalized by comparison with their Gapdh mRNA expression.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/117/15/10.1182_blood-2010-07-299644/4/m_zh89991168840004.jpeg?Expires=1765103217&Signature=Q0a-x7JADur-w2Ukmj46JmOjBtvQZ~TtlFUE7Da~2EbXjO6i5AKa6BDCMsV9XgEJkQfezmzDuOED1ZFCxw6m1wCRlvAbNlcnJzVJR7pKKPShiHh1CY6L-ySpkGa2DMBCoilA0BLBoUz~~EnGp8QJI~HmX3GXrxlfPEz2WnqsNXWjdZblvwwffikziVEa3exeijFWe-5Q4XNanmWCWc41TWmiRImGsdR9WxPgYv3R48jqPmBhPtC1CDOiSNekToIdMqkzR3mJSMEPbn1nbLfj3R~CtzZBCK628rIrcgvYRXjgZSBmOrtvwD0t8DGlawlYz0qIiLIzD1OESqxTqbUNmg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 6. CDK6 advances p185BCR-ABL–induced leukemia. (A) Top panel shows the percentages of B cells of fraction A-C in the BM (left panel) and fraction D-F in the spleens (right panel) of Cdk6−/− mice compared with Cdk6+/+ mice as analyzed by FACS (n = 3; fraction A: 2-tailed t test, P = .0379). In the bottom panel, dot blots indicate the percentages of gated CD43+/B220+ (first panel) and CD43+/B220+/CD19−/BP-1− for fraction A, CD43+/B220+/CD19+/BP-1− for fraction B, and CD43+/B220+/CD19+/BP-1+ for fraction C (second panel) in the BM and gated CD43−/B220+ (third panel) and CD43−/B220+/IgD−/IgM− for fraction D, CD43−/B220+/IgD+/IgM− for fraction E, and CD43−/B220+/IgD−/IgM− for fraction F (fourth panel) in the spleens of Cdk6−/− and Cdk6+/+ mice. (B) [3H]-thymidine incorporation into fetal liver–derived Cdk6+/+ and Cdk6−/− p185BCR-ABL–transformed cell lines was measured (n = 6; 2-tailed t test, P < .0001). (C) Cells (1 × 105) of p185BCR-ABL–transformed Cdk6+/+ (n = 3) and Cdk6−/− (n = 3) mice were plated and total cell numbers were determined after 48, 96, and 144 hours. (D) Injection of Cdk6+/+ (n = 7), Cdk6+/− (n = 23), and Cdk6−/− (n = 16) newborn mice with a replication-deficient Ab-MuLV–encoding retrovirus resulted in B-lymphoid leukemia/lymphoma (mean survival 63 vs 62 vs 120 days in Cdk6+/+, Cdk6+/−, and Cdk6−/− mice, respectively; P < .0001 for Cdk6+/+ vs Cdk6−/−). (E) The infiltration rates of CD19+/CD43+ cells in the spleens of diseased mice were analyzed by FACS (n = 6; 2-tailed t test, P = .103).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/117/15/10.1182_blood-2010-07-299644/4/m_zh89991168840006.jpeg?Expires=1765103217&Signature=cerJ4ckiKmjTiU~GQxPiLRowD36o6nKCO~kSCKhBesxT2jGSWf0OKx81Xf9y-iVGv8AHvWKWZl1XdZgjmIKCmzGj-yBSylHE1yS~ckLj8CdDDsUOU3w97TCLDmG-CTyVNZwxcypemursW-JPIccwGOCPs251vz2epOZ2TuwcGdmxiDE-yPUgR6bC9fWeHw45sLiWRzPi0LOaAjZ47S6Yd4O-4UCmuCp1h2cZ8xLncHqvrQZLGnnRpQOzQuyiah1NID1jXUSnNzg29hW9Tu5dFUdw28Qms-zUdgUXdsisUSY6v40TBCkR2x42XG7OPyqmUBTCsyqJlVlzvxHVGWCFpg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 7. Reexpression of CDK6 in c-JunΔ/Δ cells rescues the proliferative defect. (A) Immunoblot analysis of the enforced expression of CDK6 with a pMSCV-Cdk6-puro retrovirus in c-JunΔ/Δ cells. β-ACTIN served as the loading control. (B) [3H]-thymidine incorporation in c-Junfl/fl, c-JunΔ/Δ-puro, and c-JunΔ/Δ-Cdk6-puro cell lines (n = 3; 2-tailed t test, c-Junfl/fl vs c-JunΔ/Δ-puro, P = .0053; c-JunΔ/Δ-puro vs c-JunΔ/Δ-Cdk6-puro, P = .0029). (C) Cell-cycle profiles of c-Junfl/fl (n = 5) and c-JunΔ/Δ-Cdk6-puro (n = 4) cells gated on living cells. One representative set of data is depicted. (D) 1 × 106 c-Junfl/fl, c-JunΔ/Δ-puro, and c-JunΔ/Δ-Cdk6-puro p185BCR-ABL–transformed cells were injected subcutaneously into Nu/Nu mice. Two independent cell lines for each cell type were injected into mice (2-tailed t test, c-Junfl/fl [n = 17] vs c-JunΔ/Δ-puro [n = 17], P < .0001; c-JunΔ/Δ-puro [n = 17] vs c-JunΔ/Δ-Cdk6-puro [n = 11], P = .0017).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/117/15/10.1182_blood-2010-07-299644/4/m_zh89991168840007.jpeg?Expires=1765103217&Signature=h84pA-pP4XEyj9Sl~eb0ISV0-aKvDevrxZCCirT6zoHfdePQ3-iEI2DnGOHwjBRvtE7IhkZamq3nu9jO3RAYFKspw7qgL~qjf~ARDyuS36ROkj7ESEWkdgUwmC0HndfbZV31i0zOAVGn9VSkwIpGxKJEsdvFI7hIltxRhXKt35IhceIAmkLz3L7RWOFRj3Tv9Kc9SN56jk~iuNwx0J-0CxC~1ARPPY0nq2qiNTE-nBi2bEdnPBnm8nHyMWfnUGAbiX5xqxFY~tzyMEF01VzqmDYmx7Zswv0RX3Ub6W39BiFutxFUff1I-fpDLGKxabX3hoyon~a9PQ5bFgzBDEePaQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 1. c-JUN is involved in p185BCR-ABL-induced transformation and leukemogenesis. Colony formation assays were performed using 1 × 106 (A) JNK1+/− and JNK1−/− (n = 8; 2-tailed t test, 49.2 ± 7.9 vs 28.9 ± 4.1 colonies/107 fetal liver cells, P = .0401) and (B) c-Junfl/fl and c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/− (n = 6; 2-tailed t test, 60.5 ± 6.1 vs 27.3 ± 1.9 colonies/107 fetal liver cells, P = .0004) fetal liver cells after infection with a pMSCV-p185BCR-ABL-IRES-GFP retrovirus in growth factor–free methylcellulose. (C) Transplantation of 1 × 105 c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ cells into Rag2−/− mice. Two independent cell lines for each cell type were injected in 9 mice (mean survival, 11 vs 16 days in mice injected with c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ cells, respectively, P = .0307). (D) Spleen weights of diseased recipient Rag2−/− mice were analyzed (c-Junfl/fl [n = 9] and c-JunΔ/Δ [n = 9], 2-tailed t test, P = .0169).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/117/15/10.1182_blood-2010-07-299644/4/m_zh89991168840001.jpeg?Expires=1765344182&Signature=oWw2I-XlK0s0ABScMDJ5JesKdJ0yXSIP3QfgxITwLRGwxqtxojcHDbT1-9XRfPK2CAXhW4Wy-UaWEvDAxr4~fgi-~evTfUPdI5EKEGRiDvVAJsLgF6ggkELmZq2I~c5QkUqeDjEPPBXtfiUG98BMrkrEtvwHAdMI9BMTQRFP1u21UKH6zsUBJmnw0B8Q0LFAc1ga-HAPe6NLlnk7h-u35khloi-9LTod6X-bOxGnAhyVFGL07C81GG5JBJl2wrqI8UKmLI0nvGh6vETrJRC~6QrG-amEJPu55I~iHj4BmqMuAuBfNe50g852uB3lZHpL~pKS96RwRDqhYjO48ubBbA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 3. c-JunΔ/Δ p185BCR-ABL–transformed cell lines demonstrate a proliferative defect. (A) [3H]-thymidine incorporation of fetal liver–derived c-Junfl/fl (n = 3) and c-JunΔ/Δ (n = 4; 2-tailed t test, P = .0142) p185BCR-ABL-transformed cell lines. (B) 1 × 105 p185BCR-ABL-transformed c-Junfl/fl (n = 3) and c-JunΔ/Δ cells (n = 3) were plated and total cell numbers were determined after 48, 96, and 144 hours. (C) Cell-cycle profiles of c-Junfl/fl (n = 5) and c-JunΔ/Δ (n = 4) cells (2-tailed t test, G1 phase, P = .0333; S phase, P = .0173) gated on living cells. One representative set of data is depicted. (D) Tumor weights of Nu/Nu mice that were subcutaneously injected with 1 × 106 c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ leukemic cells. Three independent cell lines for each cell type were injected into 9 mice (2-tailed t test, P = .0007). (E) Injection of c-Junfl/flp53−/− (n = 11) and c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/−p53−/− (n = 7) newborn mice with a replication-deficient Ab-MuLV–encoding retrovirus resulted in B-lymphoid leukemia/lymphoma (mean survival, 31 vs 44 days in c-Junfl/flp53−/− and c-Junfl/flCD19-Cre+/−p53−/− mice, P = .0213).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/117/15/10.1182_blood-2010-07-299644/4/m_zh89991168840003.jpeg?Expires=1765344182&Signature=QqWf1t1vWmpTjUUGJyfNq4~6N91vSSQGnaFcabVoI104AbLgphWMl1H~4wQUxAzlZB5vXuukzX~Zz2-PZibZxVywe8Y6~LtI0iWalK12KV7IRF36zDKTvY~iRid7bqDoZw2boOFBv26wyHXgGHppz1mJE31ssXO0bdj7vyf4VrmRteKakNYpx5Pgjq6pLRWvzM38qIC-G3Rpmmu4ipguep-fYroQMJhyYDiCMW4FLYreyuouXMKFLPG9edCYDJmGUAvOykjRJ2IFarbGMvtbWcOmKQQ4cjOX52YVsAluxlD0Kw0d-Q4fniOB0KsUu5QgLS66Vyco1UUM~rbcDg367g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 4. CDK6 protein levels are down-regulated in c-JunΔ/Δ p185BCR-ABL–transformed cell lines. (A) Immunoblot analysis for CDK6, CDK4, CDK2, CYCLIN D2, CYCLIN D3, p16INK4a, p15INK4b, p21, and p27 protein expression in c-Junfl/fl- and c-JunΔ/Δ p185BCR-ABL–transformed cells. β-ACTIN served as the loading control. (B) Immunoblot analysis for c-JUN and CDK6 protein expression in c-Junfl/fl and c-JunΔ/Δ (top panel) and c-Junwt/wt and c-JunAA/AA (bottom panel) p185BCR-ABL–transformed cells. β-ACTIN served as the loading control. (C) c-JUN and CDK6 protein levels of c-JunΔ/Δ and c-Junfl/fl cell lines after 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks of transformation. β-ACTIN served as the loading control. One representative set of data is depicted. (D) [3H]-thymidine incorporation of the same cell lines was measured (n = 3; 2-tailed t test: c-Junfl/fl vs c-JunΔ/Δ 6 weeks, P = .002; c-Junfl/fl vs c-JunΔ/Δ 8 weeks, P = .0016). (E) Cdk6 mRNA levels of c-JunΔ/Δ and c-Junfl/fl cells 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks after p185BCR-ABL transformation were analyzed by quantitative PCR (n = 3; 2-tailed t test: c-Junfl/fl 2 weeks vs c-JunΔ/Δ 2 weeks, P = .0385; c-Junfl/fl 2 weeks vs c-Junfl/fl 8 weeks, P = .0293; c-JunΔ/Δ 2 weeks vs c-JunΔ/Δ 8 weeks, P = .0024). The fold change compared with c-JunΔ/Δ 2-week Cdk6 mRNA level is shown. Results were normalized by comparison with their Gapdh mRNA expression.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/117/15/10.1182_blood-2010-07-299644/4/m_zh89991168840004.jpeg?Expires=1765344182&Signature=uwEtv9gJmPJLQgOF1T~Zql~6t3IQSZGqoaLVJrvy2kXA6l7xGoGYb9BgmbD0J40iQrA1cGF16j1KAGdBTPhSAALqGDBo-ejGRtrlVeZvUwK9ShXM0N28q-nKky3Up5wn2Mji8KbcuYaHlR~Zi~b69XbpvCiyfXb7po3Ca2WtSAIJjj26bB~WUFUQf0oHNMVNduvsQuh1a4zgrQCRIZipZS3zl6Z4RsKJEGeFNxYFUobaA8QdM4ntKhfoF-HuSwpRIJNQqEs0ma0W44aNr9ggk-4ku9~oRXNAwrY1bOHh2cTrBLjhUzX8ZmciAyNjR3emxaeL~wPjY29l9MlHDEusfA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 6. CDK6 advances p185BCR-ABL–induced leukemia. (A) Top panel shows the percentages of B cells of fraction A-C in the BM (left panel) and fraction D-F in the spleens (right panel) of Cdk6−/− mice compared with Cdk6+/+ mice as analyzed by FACS (n = 3; fraction A: 2-tailed t test, P = .0379). In the bottom panel, dot blots indicate the percentages of gated CD43+/B220+ (first panel) and CD43+/B220+/CD19−/BP-1− for fraction A, CD43+/B220+/CD19+/BP-1− for fraction B, and CD43+/B220+/CD19+/BP-1+ for fraction C (second panel) in the BM and gated CD43−/B220+ (third panel) and CD43−/B220+/IgD−/IgM− for fraction D, CD43−/B220+/IgD+/IgM− for fraction E, and CD43−/B220+/IgD−/IgM− for fraction F (fourth panel) in the spleens of Cdk6−/− and Cdk6+/+ mice. (B) [3H]-thymidine incorporation into fetal liver–derived Cdk6+/+ and Cdk6−/− p185BCR-ABL–transformed cell lines was measured (n = 6; 2-tailed t test, P < .0001). (C) Cells (1 × 105) of p185BCR-ABL–transformed Cdk6+/+ (n = 3) and Cdk6−/− (n = 3) mice were plated and total cell numbers were determined after 48, 96, and 144 hours. (D) Injection of Cdk6+/+ (n = 7), Cdk6+/− (n = 23), and Cdk6−/− (n = 16) newborn mice with a replication-deficient Ab-MuLV–encoding retrovirus resulted in B-lymphoid leukemia/lymphoma (mean survival 63 vs 62 vs 120 days in Cdk6+/+, Cdk6+/−, and Cdk6−/− mice, respectively; P < .0001 for Cdk6+/+ vs Cdk6−/−). (E) The infiltration rates of CD19+/CD43+ cells in the spleens of diseased mice were analyzed by FACS (n = 6; 2-tailed t test, P = .103).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/117/15/10.1182_blood-2010-07-299644/4/m_zh89991168840006.jpeg?Expires=1765344182&Signature=a64brm1cJautmgn~41dxKr5XnzfcGKD85F-m1LMFhjKB5mz9sZH1kF-yzsjfz2iNALbK0HwyDPhLxeeGX1B4rJKSVZysYximLmWgCRvAiqTCjj8maX0GRFaw76EFMiuxffMDCYlToUSsu47FTZEuBBtAwC6qa4eSD46kSXp9Y~iyBAGPPq89uin6t1WrvRKkL~A5MU94pmBvSz0XYX8ea0qZRu9T5VR4Wfw5SLdQIuXPGj4dUQfxyvzQl-K7aP9T6c1NUR9o8~fBrymhuIIkkAUrCazUv4vTftSsTG-u3ElEiqEPujkgqbykdMMdPo3u5acpr4YZUUPeEE-osmr~SQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 7. Reexpression of CDK6 in c-JunΔ/Δ cells rescues the proliferative defect. (A) Immunoblot analysis of the enforced expression of CDK6 with a pMSCV-Cdk6-puro retrovirus in c-JunΔ/Δ cells. β-ACTIN served as the loading control. (B) [3H]-thymidine incorporation in c-Junfl/fl, c-JunΔ/Δ-puro, and c-JunΔ/Δ-Cdk6-puro cell lines (n = 3; 2-tailed t test, c-Junfl/fl vs c-JunΔ/Δ-puro, P = .0053; c-JunΔ/Δ-puro vs c-JunΔ/Δ-Cdk6-puro, P = .0029). (C) Cell-cycle profiles of c-Junfl/fl (n = 5) and c-JunΔ/Δ-Cdk6-puro (n = 4) cells gated on living cells. One representative set of data is depicted. (D) 1 × 106 c-Junfl/fl, c-JunΔ/Δ-puro, and c-JunΔ/Δ-Cdk6-puro p185BCR-ABL–transformed cells were injected subcutaneously into Nu/Nu mice. Two independent cell lines for each cell type were injected into mice (2-tailed t test, c-Junfl/fl [n = 17] vs c-JunΔ/Δ-puro [n = 17], P < .0001; c-JunΔ/Δ-puro [n = 17] vs c-JunΔ/Δ-Cdk6-puro [n = 11], P = .0017).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/117/15/10.1182_blood-2010-07-299644/4/m_zh89991168840007.jpeg?Expires=1765344182&Signature=p7sSk~LwTV-t7BghCT2e1dgeew~2IKbQuqZO-zftm04So8VZG3FYPbopPCII9WrWJIRYr~HcjN~LtnDXhhWEBTnTs1z~iMUtyMIMy4ItGGKUP4JxL6DIGSz40~d8IwUkCskRWvpH44Y~L35Cxv7WATrbYcRF96KNbNVfZmvymktceiyzP4lCxFKsrn~WjD5EsPPMsuu8x-0tb23u2R0M2J6QsmH-exQEy-xDoHYzA9Esq2eHTFRsfU1At-cahsDmwIjunRtz3IfmiNcF5MP~uwCeN30t3Z-rFZniz66erQE5NBkzJ-wvzRrBF0w39wGevTdheVU8UneLrvMuBm4z8A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)