Key Points

Detection of mNPM1 MRD by NGS using DNA overcomes several limitations of RT-qPCR and is therefore an attractive alternative assay.

The prognostic significance of mNPM1 MRD appears greatest in patients with AML with a concomitant FLT3-internal tandem duplications.

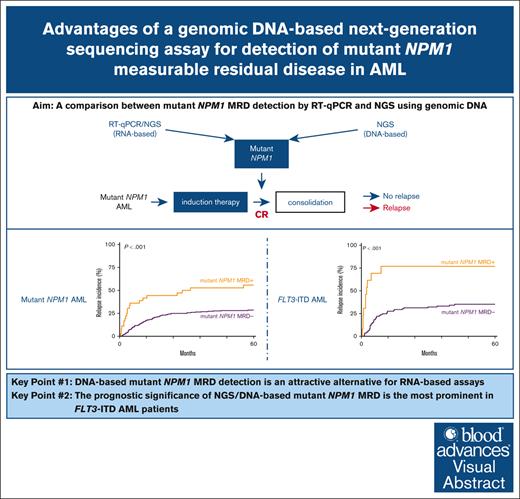

Visual Abstract

Mutations in the nucleophosmin-1 (NPM1) gene are among the most common molecular aberrations in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Various studies have established mutant NPM1 (mNPM1) as a faithful molecular measurable residual disease (MRD) marker with prognostic significance. Assessment of prognostic mNPM1 is included in the European LeukemiaNet recommendations on MRD detection in AML. Because of recent advancements of promising drugs targeting mNPM1 AML, monitoring of mNPM1 MRD has gained interest, and is generally done by reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). However, these RT-qPCR assays use complementary DNA (cDNA) as input, are based on gene expression levels of mNPM1, and are generally limited to specific mNPM1 gene variants. The main advantages of next-generation sequencing (NGS) using genomic DNA as input are stability, independence of gene expression levels, and the ability to detect any NPM1 variant in a single assay. Here, we comprehensively investigated the applicability of NGS on DNA to detect mNPM1 MRD in a cohort of 119 (cDNA) and 310 (DNA) patients with mNPM1 AML in complete remission after 2 cycles of induction chemotherapy. We demonstrate high correlations in levels and prognostic value between RT-qPCR/cDNA and NGS/DNA approaches, postulating NGS/DNA as an attractive alternative to RT-qPCR. We report that the 2% mNPM1/ABL1 threshold by RT-qPCR/cDNA corresponds to an NGS/DNA variant allele frequency of 0.01%. The NGS/DNA threshold of >0.01% after 2 cycles of induction chemotherapy identifies significantly more patients with AML with an increased relapse risk than current RT-qPCR/cDNA assays. The prognostic significance of mNPM1 MRD appears greatest in patients with AML with FLT3-internal tandem duplications.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a heterogeneous hematological malignancy characterized by an increased proliferation of undifferentiated myeloid cells that arises from the sequential acquisition of gene mutations in a hematopoietic stem cell and its daughter cells. Of patients with AML, ∼30% carry mutations in the nucleophosmin-1 (NPM1) gene in their leukemic cells. NPM1 encodes a protein critical for various important cellular processes, including ribosome biogenesis and genomic stability.1 Mutations in NPM1 are typically 4 base-pair insertions in exon 12 and result in the aberrant cytoplasmic localization of the NPM1 protein. During AML development, mutant NPM1 cells frequently harbor various additional other gene mutations, in particular and most commonly FLT3 internal tandem duplications (ITDs). Patients with mutant NPM1 AML are classified with a favorable (FLT3 wild type) or intermediate (FLT3-ITD) prognosis according to the European LeukemiaNet (ELN) 2022 risk classification, and are therefore of particular interest for monitoring treatment response with the possibility of intensifying treatment.2 Mutant NPM1–targeted treatment is currently in active development in AML. Various therapeutic compounds specifically targeting NPM1-mutant disease show promising activity and registration of menin inhibitors is likely to be expected in the near future.3

Monitoring of measurable residual disease (MRD) in AML offers important insights into disease response and therapeutic decision-making.2,4-6 Because of the stability of the mutation during the course of disease from diagnosis to relapse, and high expression of mutant transcripts, mutant NPM1 residual cells can be detected with high sensitivity by reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR), that is, 1 in 100 000 cells (0.001%), and is generally established as the standard method of measurement.7 The recent update on MRD recommendations in AML by the ELN expert panel accepts mutant NPM1 as a robust and clinically valuable molecular target for MRD testing.8 Mutant NPM1 MRD is generally assessed in the bone marrow (BM) or peripheral blood (PB) at the end of remission induction or after consolidation therapy. In follow-up, mutant NPM1 predicts an increased relapse probability when mutant NPM1/ABL1 levels exceed 2%, whereas low-level MRD (mutant NPM1/ABL1 of <2%) is associated with a more favorable response.8 Recommendations focusing on mutant NPM1 MRD after 2 cycles of chemotherapy have not been firmly established in the ELN guidelines. Two landmark studies showed that patients with AML with either 200 copies of mutant NPM1 of >104ABL1 copies9 or with mutant NPM1 at any level in the PB after regeneration after the second cycle of chemotherapy10 were shown to have the highest risk of relapse. Multiple other studies have explored the prognostic value of mutant NPM1 MRD, but substantial variations in treatment protocols, MRD detection time points, and prognostically relevant cutoffs do not permit a critical direct intercomparison of these results.11-18

Although the majority of investigational treatment protocols incorporate mutant NPM1 MRD detection by RT-qPCR, several issues remain unresolved. First, the optimal prognostic threshold to distinguish patients in complete hematological remission (CR) after remission induction chemotherapy with high and low risk of recurrence has remained subject of debate. Second, differences in mutant NPM1 gene expression levels among patients with AML together with the instability of RNA molecules before molecular testing makes standardization challenging.19 In fact, compared with DNA assays, RNA/complementary DNA (cDNA) approaches are merely an estimate of the actual level of expression of mutant NPM1. Finally, RT-qPCR assays are generally designed to detect only the most frequent NPM1 mutations (designated type A, B, and D), excluding 10% of all mutant NPM1 AML cases from effective MRD testing.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) usually requires genomic DNA as input source, which is more stable compared with RNA/cDNA-based approaches. Because mutant NPM1 MRD levels measured by NGS/DNA are independent of gene expression levels, results are likely more reproducible, interpretable, and comparable among patients with AML. Another potential advantage of NGS is the ability to comprehensively detect any NPM1 variants in a single assay such that the broad variety of patients with mutant NPM1 AML can be monitored. Finally, the 4–base-pair insertion, constituting an NPM1 mutation, can be easily distinguished from background noise, enabling NGS-based mutant NPM1 detection at relatively high sensitivity, that is, 1 in 100 000 cells (0.001%). NGS for mutant NPM1 MRD detection has not been widely implemented yet20,21 and associations between variant allele frequency (VAF) thresholds and relapse risk have not been explored.

In this study, we comprehensively compared mutant NPM1 MRD detection by RT-qPCR/cDNA and NGS/DNA assays in a large cohort of patients with newly diagnosed AML.

Methods

Patients and samples

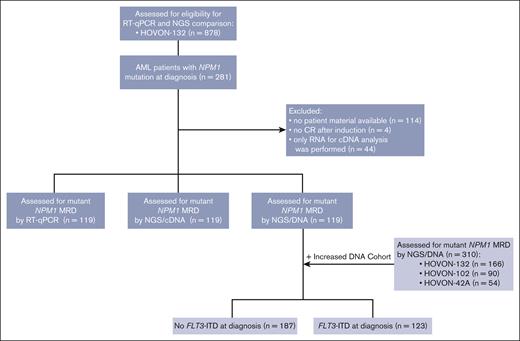

Adult patients with newly diagnosed AML were treated with remission induction chemotherapy in the Dutch-Belgian Hemato-Oncology Cooperative Group and Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research clinical trials HO42A (NL193/NTR230), HO102 (NL2070/NTR2187), or HO132 (NL4231/NTR4376).22-24 The treatment protocols and patient eligibility criteria are available in supplemental Figure 1. Trial participants provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. To be included in the study, patients with mutant NPM1 AML had to be in either complete remission or complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery (defined according to the ELN recommendation; hereafter collectively referred to as complete remission [CR]) after 2 cycles of chemotherapy. Patients with AML enrolled in the HO132 trial of whom RNA and DNA CR material was available were included (n = 119 [110 BM and 9 PB]). The NGS/DNA cohort was expanded with patients with AML from HO42A (n = 54), HO102 (n = 90), and HO132 (n = 47) to add up to a final cohort of 310 patients with AML for NGS/DNA mutant NPM1 MRD analyses in CR (Figure 1). Gene mutations at diagnosis of 54 commonly mutated genes in AML were assessed using the TruSight myeloid sequencing panel (Illumina, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. FLT3-ITDs at diagnosis were assessed using capillary fragment length analysis.9

Flow diagram of selection of cases of patients with AML included in mutant NPM1 cohort. HOVON, Dutch–Belgian Cooperative Trial Group for Hematology–Oncology.

Flow diagram of selection of cases of patients with AML included in mutant NPM1 cohort. HOVON, Dutch–Belgian Cooperative Trial Group for Hematology–Oncology.

Mutant NPM1 MRD detection by RT-qPCR

Detection of mutant NPM1 by RT-qPCR was carried out according to the recommendations set by the ELN for MRD detection in 2021.8 Mutant NPM1 copies were normalized to the number of copies of the reference gene ABL1. NPM1 and ABL1 primer and probe sequences are summarized in supplemental Table 1A. MRD was defined as mutant NPM1 detectable in duplicate, and assay criteria included a minimum of 10 000 copies of ABL1 and a Cycle threshold (Ct)-value difference between duplicates of no >1. Analysis was performed using QuantStudio design and analysis software version 1.4.1 with threshold set at 0.1 (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA). Detailed RT-qPCR protocol is described in the supplemental Methods.

Mutant NPM1 MRD detection by NGS

NPM1 mutations were determined at diagnosis on genomic DNA by NGS using the TruSight myeloid sequencing panel (Illumina, San Diego, CA). For mutant NPM1 MRD detection, a targeted single-amplicon deep NGS approach was used, covering exon 12 of the NPM1 gene. For MRD analysis by NGS/DNA, 100 ng high–molecular weight genomic DNA was used as input. The library preparation protocols for NGS/DNA and NGS/cDNA are described in the supplemental Methods, and only differed in the primers used for the first target PCR (supplemental Table 1B). The average read coverage of the NGS/DNA approach was 1 264 927 (range, 85 277-2 333 905).

FLT3-ITD MRD detection by NGS

FLT3-ITD MRD was assessed using a targeted deep sequencing approach as described before.25

Statistical analysis

The primary end point of the MRD analysis was cumulative incidence of relapse (CIR). Time to relapse and survival were estimated from date of sampling in CR until the date of the event of interest. Survival analyses were performed using Kaplan-Meier estimates, and significance was assessed using the log-rank test. Multivariable analysis was performed using Cox proportional hazards model. Differences in patient characteristics were tested with the Fisher exact test (categorical) or Mann-Whitney U test (continuous). P values of <.05 were considered statistically significant, and all tests were 2-sided. Stata statistics and data science software, Release 17.0 (Stata, College Station, TX) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Mutant NPM1 MRD detection by RT-qPCR on cDNA

Mutant NPM1 detection by RT-qPCR/cDNA in CR after 2 cycles of induction chemotherapy was performed on patients with mutant NPM1 AML. Mutant NPM1 MRD was detected in 94 cases (79%) with a limit of detection (LOD) of 10–6 (Figure 2A). Stratification of patients with AML following various mutant NPM1/ABL1 thresholds demonstrate that the group with >2% mutant NPM1/ABL1 after cycle 2 was most significantly associated with increased relapse risk (P = .016; Figure 2B) and inferior overall survival (OS; P < .001; supplemental Figure 3A-B) compared with other thresholds. In fact, the groups of patients with AML with mutant NPM1/ABL1 MRD of <2% did not differ statistically significantly in terms of treatment outcome from the patient group without mutant NPM1 MRD. However, relapse incidence was slightly increased for patients with AML with low-level MRD, suggesting that these groups contain a mix of patients with or without a higher risk of relapse that cannot be distinguished based on mutant NPM1 levels.

Mutant NPM1 MRD detection by RT-qPCR/cDNA. (A) LOD of mutant NPM1 by RT-qPCR/cDNA. (B) CIR of patients with AML with different mutant NPM1/ABL1 thresholds by RT-qPCR/cDNA. Neg, LOD, Limit of detection.

Mutant NPM1 MRD detection by RT-qPCR/cDNA. (A) LOD of mutant NPM1 by RT-qPCR/cDNA. (B) CIR of patients with AML with different mutant NPM1/ABL1 thresholds by RT-qPCR/cDNA. Neg, LOD, Limit of detection.

Mutant NPM1 MRD detection by NGS on genomic DNA

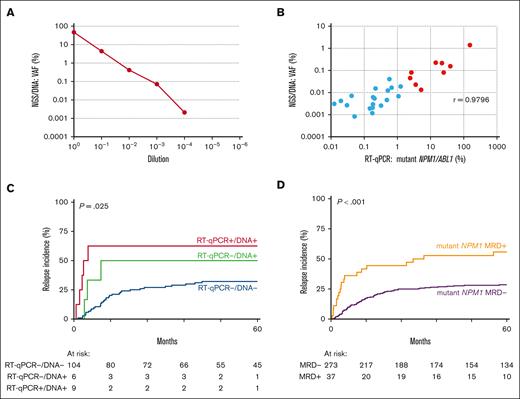

Next, we explored NGS-based mutant NPM1 MRD detection on DNA. The LOD of mutant NPM1 by NGS/DNA was 10–4 (VAF, 2.1 × 10–3; Figure 3A). Among 119 AML cases in CR, 29 (24%) had measurable mutant NPM1 by NGS/DNA, of which 28 (97%) were also detectable by RT-qPCR/cDNA. In addition, there were 67 discordant cases in which mutant NPM1 was detectable by RT-qPCR/cDNA but undetectable with NGS/DNA (supplemental Table 2). All these discordant cases carried mutant NPM1/ABL1 ratios at low levels (<0.56% mutant NPM1/ABL1 by RT-qPCR). The correlation between VAF values by NGS/DNA and mutant NPM1/ABL1 by RT-qPCR was high (r = 0.98; Figure 3B). In fact, a similar NGS approach was carried out on cDNA(LOD, 10–5; supplemental Figure 4A). Mutant NPM1 MRD was detected in 48 (40%) patients, and a strong correlation between mutant NPM1 VAFs by NGS/cDNA and mutant NPM1/ABL1 by RT-qPCR/cDNA was found, with 0.1% VAF approximately corresponding to 2% mutant NPM1/ABL1 (r = 0.99; supplemental Figure 4B). CIR and OS were similar for NGS/cDNA compared with RT-qPCR, with MRD defined as VAF of >0.1% (supplemental Figure 4C-D).

Mutant NPM1 MRD detection by NGS/DNA. (A) LOD of mutant NPM1 by NGS/DNA. (B) Correlation of mutant NPM1 detection by RT-qPCR/cDNA and NGS/DNA, with cases of >2% mutant NPM1/ABL1 indicated in red. (C) CIR of mutant NPM1 MRD as detected by RT-qPCR/cDNA (MRD with >2% mutant NPM1/ABL1) and/or NGS/DNA (MRD at >0.01%) in a cohort of 119 patients with mutant NPM1 AML. (D) CIR of mutant NPM1 MRD as detected by NGS/DNA in a cohort of 310 patients with mutant NPM1 AML (MRD of >0.01% VAF). Patients with detectable mutant NPM1 MRD indicated in yellow, patients without detectable mutant NPM1 MRD indicated in purple.

Mutant NPM1 MRD detection by NGS/DNA. (A) LOD of mutant NPM1 by NGS/DNA. (B) Correlation of mutant NPM1 detection by RT-qPCR/cDNA and NGS/DNA, with cases of >2% mutant NPM1/ABL1 indicated in red. (C) CIR of mutant NPM1 MRD as detected by RT-qPCR/cDNA (MRD with >2% mutant NPM1/ABL1) and/or NGS/DNA (MRD at >0.01%) in a cohort of 119 patients with mutant NPM1 AML. (D) CIR of mutant NPM1 MRD as detected by NGS/DNA in a cohort of 310 patients with mutant NPM1 AML (MRD of >0.01% VAF). Patients with detectable mutant NPM1 MRD indicated in yellow, patients without detectable mutant NPM1 MRD indicated in purple.

All samples with mutant NPM1/ABL1 of >2% by RT-qPCR were detected with NGS/DNA with VAFs of >0.01% (Figure 3B). This illustrates that the 2% mutant NPM1/ABL1 by RT-qPCR threshold corresponds to ∼1 mutant NPM1 cell in 10 000 NPM1 wild-type cells. Relapse rates in patients with AML with mutant NPM1 VAF of >0.01% by NGS/DNA were significantly increased (4-year CIR: 57.1% MRD+ vs 32.2% MRD–; hazard ratio [HR], 2.82; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.13-7.03; P = .026; supplemental Figure 5A). Notably, the NGS/DNA VAF threshold of >0.01% identified patients with AML with a significantly increased risk of relapse, including cases that were missed by RT-qPCR/cDNA with mutant NPM1/ABL1 of >2% (P = .025; Figure 3C). Although this is only a small number of patients with AML in our cohort (n = 6), it increases the number of cases at risk considerably (7.5% to 13%).

We confirmed the prognostic value of mutant NPM1 MRD by NGS/DNA with the >0.01% VAF threshold in an independent cohort of 191 AML cases with available DNA samples (4-year CIR: 50.0% MRD+ vs 25.6% MRD–; HR, 2.55; 95% CI, 1.38-4.71; P = .003; supplemental Figure 5B).

Next, we combined all mutant NPM1 MRD analyses by NGS/DNA to a cohort of 310 AML cases in total (BM, n = 301 and PB, n = 9). Eighty-three (27%) of 310 AML samples had measurable mutant NPM1 by NGS/DNA at any level. These cases showed a significant increase in relapse incidence compared with patients without detectable mutant NPM1 (4-year CIR: 42.7% MRD+ vs 26.7% MRD–; HR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.17-2.65; P = .007; supplemental Figure 5C). Applying the previously established MRD threshold of VAF >0.01% by NGS/DNA in the enlarged cohort, resulted in 37 patients (12%) with relatively high-level mutant NPM1 disease and a highly significant increased risk of relapse (4-year CIR: 52.8% MRD+ vs 28.1% MRD–; HR, 2.56; 95% CI, 1.54-4.25; P < .001; Figure 3D), and inferior OS (P > .001; supplemental Figure 5D).

Multiparameter flow cytometry (MFC) MRD results were available in 245 of 310 patients with AML. No clear correlation was apparent between MFC-MRD and mutant NPM1 MRD by NGS/DNA with or without a VAF threshold of 0.01% (supplemental Table 3A-B). Furthermore, MFC-MRD was not found to be prognostically relevant in this cohort of patients with AML (supplemental Figure 6).

Influence of concomitant mutations on mutant NPM1 MRD outcome

Next, we addressed the influence of concomitant mutations at diagnosis on the prognostic value of mutant NPM1 MRD by NGS/DNA (VAF > 0.01%). Mutations in DNMT3A (n = 172, 55%) and FLT3-ITDs (n = 123, 40%) were the most common coexisting aberrations (supplemental Figure 7). Patients with AML with FLT3-ITD had significantly higher white blood cell count (WBC) at diagnosis (P = .013), were more often consolidated with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (P < .001), and less frequently had a complex karyotype (P = .015; Table 1).

Patient characteristics of patients with AML with mutated NPM1

| . | No FLT3-ITD (n = 187) . | FLT3-ITD (n = 123) . | Total (n = 310) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | P = .204 | |||

| Median | 52 | 53 | 52 | |

| Range | 19-65 | 26-66 | 19-66 | |

| Sex, n (%) | P = .561 | |||

| M | 91 (49) | 55 (45) | 146 (47) | |

| F | 96 (51) | 68 (55) | 164 (53) | |

| ELN risk classification (%) | P < .001 | |||

| Favorable | 182 (97) | 1 (1) | 183 (59) | |

| Intermediate | 0 (0) | 121 (98) | 121 (39) | |

| Adverse | 5 (3) | 1 (1) | 6 (2) | |

| Disease type (%) | P = .565 | |||

| De novo AML | 186 (99.5) | 121 (98) | 307 (99) | |

| Therapy-related AML | 1 (0.5) | 2 (2) | 3 (1) | |

| WBC at diagnosis, n (%) | P = .013 | |||

| <100 × 109/L | 171 (91) | 100 (81) | 271 (87) | |

| >100 × 109/L | 16 (9) | 23 (19) | 39 (13) | |

| Last treatment before first CR, n (%) | P = .243 | |||

| Cycle 1 | 172 (92) | 108 (88) | 280 (90) | |

| Cycle 2 | 15 (8) | 15 (12) | 30 (10) | |

| Consolidation therapy, n (%) | P < .001 | |||

| None | 16 (9) | 15 (12) | 31 (10) | |

| Chemotherapy | 55 (29) | 17 (14) | 72 (23) | |

| Autologous HSCT | 88 (47) | 23 (19) | 111 (36) | |

| Allogeneic HSCT | 28 (15) | 68 (55) | 96 (31) | |

| Cytogenetics, n (%)∗ | P = .015 | |||

| Normal karyotype | 158 (87) | 113 (96) | 271 (91) | |

| Aberrant karyotype | 23 (13) | 5 (4) | 28 (9) | |

| Mutations at diagnosis, n (%) | P = .035 | |||

| DNMT3A | ||||

| Wild-type | 92 (49) | 45 (37) | 137 (44) | |

| Mutant | 95 (51) | 78 (63) | 173 (56) |

| . | No FLT3-ITD (n = 187) . | FLT3-ITD (n = 123) . | Total (n = 310) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | P = .204 | |||

| Median | 52 | 53 | 52 | |

| Range | 19-65 | 26-66 | 19-66 | |

| Sex, n (%) | P = .561 | |||

| M | 91 (49) | 55 (45) | 146 (47) | |

| F | 96 (51) | 68 (55) | 164 (53) | |

| ELN risk classification (%) | P < .001 | |||

| Favorable | 182 (97) | 1 (1) | 183 (59) | |

| Intermediate | 0 (0) | 121 (98) | 121 (39) | |

| Adverse | 5 (3) | 1 (1) | 6 (2) | |

| Disease type (%) | P = .565 | |||

| De novo AML | 186 (99.5) | 121 (98) | 307 (99) | |

| Therapy-related AML | 1 (0.5) | 2 (2) | 3 (1) | |

| WBC at diagnosis, n (%) | P = .013 | |||

| <100 × 109/L | 171 (91) | 100 (81) | 271 (87) | |

| >100 × 109/L | 16 (9) | 23 (19) | 39 (13) | |

| Last treatment before first CR, n (%) | P = .243 | |||

| Cycle 1 | 172 (92) | 108 (88) | 280 (90) | |

| Cycle 2 | 15 (8) | 15 (12) | 30 (10) | |

| Consolidation therapy, n (%) | P < .001 | |||

| None | 16 (9) | 15 (12) | 31 (10) | |

| Chemotherapy | 55 (29) | 17 (14) | 72 (23) | |

| Autologous HSCT | 88 (47) | 23 (19) | 111 (36) | |

| Allogeneic HSCT | 28 (15) | 68 (55) | 96 (31) | |

| Cytogenetics, n (%)∗ | P = .015 | |||

| Normal karyotype | 158 (87) | 113 (96) | 271 (91) | |

| Aberrant karyotype | 23 (13) | 5 (4) | 28 (9) | |

| Mutations at diagnosis, n (%) | P = .035 | |||

| DNMT3A | ||||

| Wild-type | 92 (49) | 45 (37) | 137 (44) | |

| Mutant | 95 (51) | 78 (63) | 173 (56) |

F, female; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplant; M, male; WBC, white blood cell.

Cytogenetics failed in 11 patients.

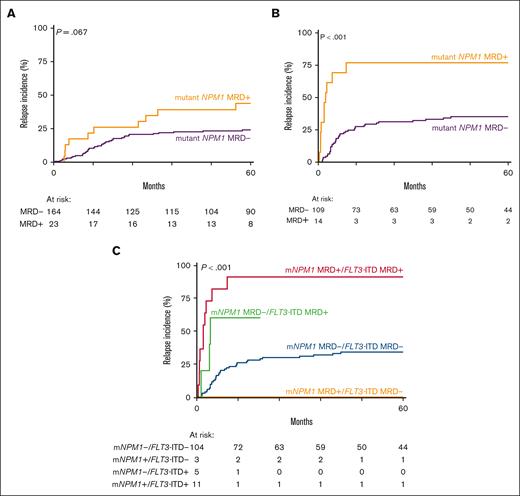

Next, we explored the effect of mutant NPM1 MRD (VAF > 0.01%) by NGS/DNA in patients with AML with a FLT3-ITD (n = 123) and patients without a FLT3-ITD (n = 187) at diagnosis. In the subgroup without a FLT3-ITD (n = 187), mutant NPM1 MRD was detected in 23 patients with AML (12%). Persistence of mutant NPM1 in CR only shows a trend of a higher relapse rate after 5 years compared with patients with AML without mutant NPM1 MRD (P = .067; Figure 4A). In contrast, in patients with a concomitant FLT3-ITD the presence of mutant NPM1 MRD (n = 14) was associated with a significantly higher relapse incidence (P < .001; Figure 4B), with 75% of the patients facing a relapse after 5 years compared to ∼30% of patients with AML with mutant NPM1 MRD with VAF of <0.01%. Similarly, in terms of OS, persistence of mutant NPM1 in CR was inferior in patients with a co-occurring FLT3-ITD than patients without (supplemental Figure 8). In multivariable analysis including age, number of cycles to attain CR, and white blood cell count at diagnosis, mutant NPM1 MRD with VAF of >0.01% was not prognostic in patients with wild-type FLT3-ITD (P = .102; supplemental Table 4) but remained a strong independent predictor of relapse in patients with FLT3-ITD AML (P = .001; Table 2).

Mutant NPM1 MRD detection in patients with AML with a concomittant FLT3-ITD. (A) Relapse incidence of mutant NPM1 (mNPM1) MRD (NGS/DNA, >0.01% VAF) in patients with AML without FLT3-ITD at diagnosis. Patients with detectable mNPM1 MRD indicated in yellow, patients without detectable NPM1 MRD indicated in purple. (B) Relapse incidence of mNPM1 MRD (NGS/DNA, >0.01% VAF) in patients with AML with a FLT3-ITD at diagnosis. Patients with detectable mNPM1 MRD indicated in yellow, patients without detectable NPM1 MRD indicated in purple. (C) Relapse incidence of patients with AML with and without mNPM1 MRD in patients with AML with a FLT3-ITD at diagnosis in the context of FLT3-ITD MRD.

Mutant NPM1 MRD detection in patients with AML with a concomittant FLT3-ITD. (A) Relapse incidence of mutant NPM1 (mNPM1) MRD (NGS/DNA, >0.01% VAF) in patients with AML without FLT3-ITD at diagnosis. Patients with detectable mNPM1 MRD indicated in yellow, patients without detectable NPM1 MRD indicated in purple. (B) Relapse incidence of mNPM1 MRD (NGS/DNA, >0.01% VAF) in patients with AML with a FLT3-ITD at diagnosis. Patients with detectable mNPM1 MRD indicated in yellow, patients without detectable NPM1 MRD indicated in purple. (C) Relapse incidence of patients with AML with and without mNPM1 MRD in patients with AML with a FLT3-ITD at diagnosis in the context of FLT3-ITD MRD.

Multivariable analysis of mutant NPM1 MRD in patients with AML with a FLT3-ITD at diagnosis

| Prognostic factor . | Relapse incidence . | |

|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) . | P value . | |

| Mutant NPM1 MRD status (detectable vs not detectable) | 4.79 (1.84-12.44) | .001 |

| Age (per year) | 1.00 (0.97-1.04) | .86 |

| No. of cycles to attain CR (2 vs 1 cycle) | 0.70 (0.26-1.85) | .47 |

| WBC counts at diagnosis (>100 × 109 vs ≤100 × 109) | 1.59 (0.78-3.22) | .20 |

| Prognostic factor . | Relapse incidence . | |

|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) . | P value . | |

| Mutant NPM1 MRD status (detectable vs not detectable) | 4.79 (1.84-12.44) | .001 |

| Age (per year) | 1.00 (0.97-1.04) | .86 |

| No. of cycles to attain CR (2 vs 1 cycle) | 0.70 (0.26-1.85) | .47 |

| WBC counts at diagnosis (>100 × 109 vs ≤100 × 109) | 1.59 (0.78-3.22) | .20 |

WBC, white blood cell.

FLT3-ITD MRD has recently been shown to be a strong predictor of relapse in FLT3-ITD AML.25-27 Of 14 patients with AML with mutant NPM1 MRD with VAF of >0.01% in CR, 11 cases also had detectable FLT3-ITD MRD with VAF of >0.01%. The 3 patients with mutant NPM1 MRD without FLT3-ITD MRD in CR did not relapse within 5 years (Figure 4C). In contrast, the 5 patients without mutant NPM1 MRD but with detectable FLT3-ITD MRD showed an increased CIR (Figure 4C).

Discussion

MRD assessment of mutant NPM1 in patients with AML is currently performed primarily by using RT-qPCR assays on cDNA. For various reasons this assay has limitations and particular drawbacks. The most prominent disadvantages relate to (1) the instability of the RNA input material, (2) the MRD levels that are based on expression of the target genes that vary among patients with AML, and (3) the MRD analyses that are generally limited to the most frequent NPM1 mutation types. There is an intense clinical interest in a robust mutant NPM1 MRD detection assay, and the establishment of reliable prognostically relevant thresholds that would resolve these issues and enable better comparison, verification, and harmonization of assays across molecular diagnostic laboratories.

Here, we show that NGS can reliably assess mutant NPM1 MRD with a very high concordance between RT-qPCR/cDNA (mutant NPM1/ABL1) and NGS/DNA (mutant NPM1/wild-type NPM1). Although NGS/DNA is ∼10-fold less sensitive compared with cDNA-based assays, a high correlation between mutant NPM1 VAFs by NGS/DNA and mutant NPM1/ABL1 by RT-qPCR is apparent. The difference in sensitivity does not preclude the association with relapse risk, because patients with AML with higher levels of mutant NPM1/ABL1 expression (>2% by RT-qPCR) were easily detected by NGS/DNA (VAF > 0.01%). In fact, a substantial number of additional patients with AML at higher risk of relapse were identified with >0.01% VAF by NGS/DNA, compared with >2% mutant NPM1/ABL1 by RT-qPCR/cDNA. Moreover, we show that MRD assessment for mutant NPM1 after 2 cycles of chemotherapy is prognostic for relapse with a mutant NPM1/ABL1 threshold of 2% in the BM. Whereas the current guidelines state that PB is preferred for post–cycle 2 assessment, we show here that cDNA/DNA derived from the BM is equally proficient. However, because of the unavailability of paired PB/BM samples, a comparison could not be performed. In addition, although MFC-MRD is established for MRD assessment in AML, it did not correlate with mutant NPM1 MRD by NGS/DNA, and MFC-MRD has limited prognostic value in our mutant NPM1 AML patient cohort. Altogether, our data indicate that NGS can be used as a reliable MRD detection method that identifies patients with mutant NPM1 AML with prognostic significance. Importantly, NGS-based assays with DNA as input will allow an easier way of harmonizing mutant NPM1 MRD detection among users.

Models of AML progression support the acquisition of NPM1 mutations as an intermediate event that is frequently preceded by mutations in DNMT3A and followed by FLT3-ITDs or other mutations in activated signaling genes, such as KRAS, NRAS, PTPN11, or FLT3-TKDs.28 Previous work has shown that FLT3-ITD persistence in AML with FLT3-ITD in CR after induction treatment is a strong and independent prognostic marker for inferior OS and increased relapse incidence.25-27 The threshold of FLT3-ITD MRD showing the best correlation with disease outcomes in independent studies corresponded with a value of >0.01%.18,25,26 The optimal prognostically relevant threshold of mutant NPM1 VAF of >0.01% reported here is as expected because the VAFs of concomitant mutations, in this case mutant NPM1 and FLT3-ITD, are expected to be similar.

We demonstrated that mutant NPM1 MRD detection is particularly prognostic in FLT3-ITD AML. Mutant NPM1 will act as a surrogate MRD marker for FLT3-ITD MRD in mutant NPM1/FLT3-ITD AML. A similar but less profound association of mutant NPM1 MRD with a higher relapse risk in FLT3-ITD AML has been reported before,12 however, in the majority of studies this association was not addressed9,11,18 or absent.10 Although the number of patients with mutant NPM1/FLT3-ITD AML in our study was small, cases with FLT3-ITD MRD had a higher CIR and none of the patients with only mutant NPM1 MRD experienced relapse within 5 years. Altogether, this may indicate that combinatorial MRD analyses of mutant NPM1 and FLT3-ITD MRD analyses are preferred in mutant NPM1/FLT3-ITD AML, however additional molecular MRD analyses in this subtype of AML are warranted.

In conclusion, we showed that mutant NPM1 MRD detection with VAF of >0.01% by NGS/DNA-based assays reliably identifies patients with AML with an increased CIR after 2 cycles of chemotherapy, most profoundly in mutant NPM1/FLT3-ITD AML. Harmonization of this alternative NGS/DNA-based assay is expected to be relatively easy and may be useful in resolving many of the current issues with respect to mutant NPM1 MRD detection in clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the patients, clinicians, research nurses, data managers, and laboratory scientists who provided samples, conducted cytogenetic analyses, and performed analyses at the participating centers of the Dutch-Belgian Cooperative Trial Group for Hematology-Oncology and the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research, including centers in The Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland, Norway, Sweden, Lithuania, Germany, and Denmark. The authors thank the Erasmus MC Hematology department, the Molecular Diagnostic unit of the Hemato-oncology laboratory, and Eric Bindels for performing the sequencing; as well as Mathijs Sanders and Remco Hoogenboezem for assisting with bioinformatics.

This study was supported by grants from the Queen Wilhelmina Fund Foundation of the Dutch Cancer Society (EMCR 2019-12507 and 2021-13650 infra).

Authorship

Contribution: C.M.V., T.G., B.L., and P.J.M.V. designed the study; G.J.O., M.G.M., V.H., Y.F., and B.L. provided study materials or patients; C.M.V., M.R., and F.G.K. performed experiments; C.M.V., T.G., M.R., F.G.K., and J.M.L.K. analyzed data; C.M.V. and T.G. prepared the figures; C.M.V., T.G., B.L. and P.J.M.V. drafted the manuscript with input from the remaining authors; and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Peter J. M. Valk, Department of Hematology, Erasmus University Medical Center Rotterdam, Nc806, Wytemaweg 80, 3015 CN Rotterdam Z-H, The Netherlands; email: p.valk@erasmusmc.nl.

References

Author notes

The data sets generated and/or analyzed during this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author, Peter J. M. Valk (p.valk@erasmusmc.nl).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.