Key Points

FL patients with concomitant HBV infection show early disease progression and may represent a separate subtype of FL.

Genomic and transcriptomic analyses revealed distinct mutation targets and tumorigenic pathways in HBV-associated FL.

Abstract

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection has been associated with an increased risk for B-cell lymphomas. We previously showed that 20% of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) patients from China, an endemic area of HBV infection, have chronic HBV infection (surface antigen–positive, HBsAg+) and are characterized by distinct clinical and genetic features. Here, we showed that 24% of follicular lymphoma (FL) Chinese patients are HBsAg+. Compared with the HBsAg− FL patients, HBsAg+ patients are younger, have a higher histological grade at diagnosis, and have a higher incidence of disease progression within 24 months. Moreover, by sequencing the genomes of 109 FL tumors, we observed enhanced mutagenesis and distinct genetic profile in HBsAg+ FLs, with a unique set of preferentially mutated genes (TNFAIP3, FAS, HIST1H1C, KLF2, TP53, PIM1, TMSB4X, DUSP2, TAGAP, LYN, and SETD2) but lack of the hallmark of HBsAg− FLs (ie, IGH/BCL2 translocations and CREBBP mutations). Transcriptomic analyses further showed that HBsAg+ FLs displayed gene-expression signatures resembling the activated B-cell–like subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, involving IRF4-targeted genes and NF-κB/MYD88 signaling pathways. Finally, we identified an increased infiltration of CD8+ memory T cells, CD4+ Th1 cells, and M1 macrophages and higher T-cell exhaustion gene signature in HBsAg+ FL samples. Taken together, we present new genetic/epigenetic evidence that links chronic HBV infection to B-cell lymphomagenesis, and HBV-associated FL is likely to have a distinct cell-of-origin and represent as a separate subtype of FL. Targetable genetic/epigenetic alterations identified in tumors and their associated tumor microenvironment may provide potential novel therapeutic approaches for this subgroup of patients.

Introduction

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is the second most common type of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), comprising ∼35% of NHLs.1 It is more common in subjects aged >60 years and is characterized by a variable clinical course. According to the latest World Health Organization classification, FL can be morphologically divided into different grades based on the percentage of centroblasts.2 Grades 1-3A FLs are generally considered indolent, whereas grade 3B FLs appear to be more aggressive. Several additional subgroups have also been described, including in situ FL, duodenal-type FL, and pediatric-type FL (PTFL).2 Although patients with FL frequently respond to chemoimmunotherapies, it remains largely incurable, with inevitable relapse or progression, and ∼30% to ∼40% of FL cases may transform into diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).3

Genetically, one of the hallmarks of FL is t(14;18) translocation, accounting for ∼80% to ∼90% of all cases.4 This genetic lesion leads to constitutive overexpression of BCL2, which blocks the apoptotic process. However, BCL2 deregulation is not sufficient for driving malignant transformation, and additional factors are required for lymphomagenesis.4 Using next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies, the genetic basis of FL progression and transformation has been studied in several cohorts.5-11 The most highly and recurrently mutated genes in FL are involved in the process of histone modification (EZH2, KMT2D, CREBBP, MEF2B, and ARID1A) and linker histone genes HIST1H1B-E.12 Additional frequently mutated genes have also been discovered in FL, including BCL2, TNFRSF14, IRF8, STAT6, PIM1, CARD11, and RRAGC.5-11,13 Mutations in MYC, TP53, B2M, and PIM1, deletions in CDKN2A/2B, and aberrant somatic hypermutation have furthermore been associated with the genome of transformed FLs, which is more related to germinal center B-cell-like (GCB)-DLBCL.14 Seven of the recurrently mutated genes in FL have been used to build a clinicogenomic risk model (m7 Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index [m7-FLIPI]) to predict disease outcome.15 In addition, molecular features of tumor-infiltrating cells, evaluated by immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, and gene-expression signatures have been used to predict the survival of FL patients.16 More recently, a gene-expression profiling score was developed to predict the outcome of FL patients.17 To date, however, in contrast to DLBCL,18,19 there have been no distinct molecular subtypes defined for FL.

Several viruses, such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human T-cell lymphotropic virus, human immunodeficiency virus, and hepatitis B/C viruses (HBV/HCV) have been implicated as etiologic factors for lymphoma.20,21 A meta-analysis indicated that patients with hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) seropositivity have a significantly higher risk of developing NHL,22-24 including FL.24,25 Recently, HBsAg seropositivity was shown to correlate with poor overall survival and progression of disease within 24 months (POD24) in FL patients.26 We previously showed that HBsAg+ DLBCL in Chinese patients displayed distinct clinical and genetic features, suggesting a role of HBV infection in the development of DLBCL.21 Here, we performed an integrative genomic and transcriptomic analysis to investigate the potential role of HBV infection in the pathogenesis of FL.

Materials and methods

Patient materials

Frozen tumor biopsies (n = 135) and matched peripheral blood samples (n = 76) from FL patients were collected at Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute (supplemental Table 1). Detections of HBsAg and relevant antibodies and HBV DNA levels were performed as routine clinical tests. Based on clinical guidelines in China, HBsAg+ FL patients with HBV DNA levels >2000 IU/mL were treated with antiviral agents (entecavir, lamivudine, or tenofovir disoprox) before starting the standard immunochemotherapy. Patients with HBV DNA levels <2000 IU/mL received the cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone (CHOP)/rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone (R-CHOP) treatment combined with the antiviral therapy to avoid the reactivation of HBV virus. POD24 was defined as progression or relapse of the disease within the first 24 months following the first-line therapy. The Swedish FL patients (n = 100) were all HBsAg− and have been described previously.27 The study was approved by the institutional review boards of Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Karolinska Institutet and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

NGS

Whole-genome or whole-exome sequencing (WGS/WES) were performed on either Illumina HiSeq 2000 (Illumina) or DNBSEQ (BGI) platform. Paired FL tumor/control samples were sequenced by WGS (n = 61) or WES (n = 15), and additional 33 FL tumor samples were sequenced by lymphochip.21 The performance of various sequencing platforms is summarized in supplemental Table 2. Transcriptome sequencing was performed on RNA prepared from 101 FL tumors. More details of data analysis on significantly mutated genes, mutational signatures, structural variants, transcriptome, and prediction of tumor infiltrating cells are provided in supplemental Methods. Sequencing data can be found in the China National Genebank (https://db.cngb.org/cnsa/project/CNP0002528/reviewlink/, accession number CNP0002528).28,29

Results

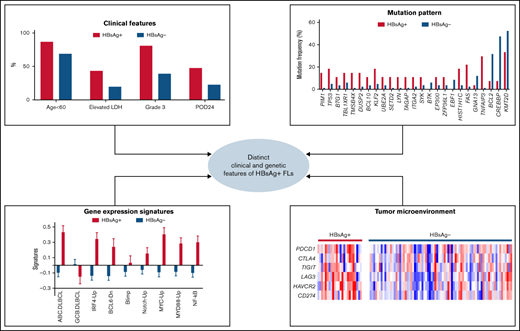

Clinical features of HBsAg+ FLs

The HBsAg+ rate in the Chinese FL patients included in the study was 24% (32/135), which is similar to that observed in Chinese DLBCL patients (20%, 56/275)21 but notably higher than that in the general population (7%).30 There was no significant difference in sex, performance status, stage at diagnosis, or risk scores predicted by the FLIPI, m7-FLIPI, and PRIMA-prognostic index31 between the HBsAg+ and HBsAg− groups (Table 1). However, HBsAg+ patients were significantly younger at diagnosis (median age, 45 vs 52) and had elevated levels of lactate dehydrogenase and higher histological grades at diagnosis (grade 3A/B). Furthermore, HBsAg+ patients had a significantly higher incidence of POD24 than HBsAg− patients (R-CHOP, P = .037, Table 1; CHOP, 100% vs 42%; P = .017). Finally, no significant differences were observed in the clinical data of HBsAg+ FL patients with different HBV DNA levels (>2000 IU/mL vs <2000 IU/mL).

Clinical characteristics of HBsAg+ and HBsAg− FL patients

| . | HBsAg+ FL (%) . | HBsAg− FL (%) . | P value* . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 32 | 103 | |

| Age (y)‡ | |||

| >60 | 4 (13%) | 32 (31%) | .038† |

| ≤60 | 28 (87%) | 71 (69%) | |

| Sex‡ | |||

| Female | 14 (44%) | 44 (43%) | .918 |

| Male | 18 (56%) | 59 (57%) | |

| Performance status‡ | |||

| 0-1 | 30 (94%) | 96 (94%) | .939 |

| 2-4 | 2 (6%) | 6 (6%) | |

| Elevated LDH‡ | |||

| Yes | 13 (43%) | 19 (20%) | .012† |

| No | 17 (57%) | 75 (80%) | |

| Stage‡ | |||

| I-II | 5 (17%) | 23 (23%) | .445 |

| III-IV | 25 (83%) | 76 (77%) | |

| FLIPI score‡ | |||

| 0-1 | 5 (19%) | 15 (17%) | .991 |

| 2 | 7 (26%) | 24 (27%) | |

| 3-5 | 15 (55%) | 49 (56%) | |

| M7-FLIPI score‡ | |||

| High risk | 4 (17%) | 17 (22%) | .628 |

| Low risk | 19 (83%) | 60 (78%) | |

| PRIMA-PI‡ | |||

| High risk | 2 (13%) | 22 (30%) | .158 |

| Intermediate risk | 3 (19%) | 5 (7%) | |

| Low risk | 11 (69%) | 47 (64%) | |

| Grade‡ | |||

| 1-2 | 6 (19%) | 59 (61%) | <.001† |

| 3A | 15 (48%) | 27 (27%) | |

| 3B | 5 (16%) | 3 (3%) | |

| 3 (mixed 3A and 3B) | 3 (10%) | 6 (6%) | |

| 3A/B combined DLBCL | 2 (7%) | 5 (5%) | |

| POD24 (R-CHOP)‡ | |||

| Yes | 10 (48%) | 13 (23%) | .037† |

| No | 11 (52%) | 43 (77%) | |

| . | HBsAg+ FL (%) . | HBsAg− FL (%) . | P value* . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 32 | 103 | |

| Age (y)‡ | |||

| >60 | 4 (13%) | 32 (31%) | .038† |

| ≤60 | 28 (87%) | 71 (69%) | |

| Sex‡ | |||

| Female | 14 (44%) | 44 (43%) | .918 |

| Male | 18 (56%) | 59 (57%) | |

| Performance status‡ | |||

| 0-1 | 30 (94%) | 96 (94%) | .939 |

| 2-4 | 2 (6%) | 6 (6%) | |

| Elevated LDH‡ | |||

| Yes | 13 (43%) | 19 (20%) | .012† |

| No | 17 (57%) | 75 (80%) | |

| Stage‡ | |||

| I-II | 5 (17%) | 23 (23%) | .445 |

| III-IV | 25 (83%) | 76 (77%) | |

| FLIPI score‡ | |||

| 0-1 | 5 (19%) | 15 (17%) | .991 |

| 2 | 7 (26%) | 24 (27%) | |

| 3-5 | 15 (55%) | 49 (56%) | |

| M7-FLIPI score‡ | |||

| High risk | 4 (17%) | 17 (22%) | .628 |

| Low risk | 19 (83%) | 60 (78%) | |

| PRIMA-PI‡ | |||

| High risk | 2 (13%) | 22 (30%) | .158 |

| Intermediate risk | 3 (19%) | 5 (7%) | |

| Low risk | 11 (69%) | 47 (64%) | |

| Grade‡ | |||

| 1-2 | 6 (19%) | 59 (61%) | <.001† |

| 3A | 15 (48%) | 27 (27%) | |

| 3B | 5 (16%) | 3 (3%) | |

| 3 (mixed 3A and 3B) | 3 (10%) | 6 (6%) | |

| 3A/B combined DLBCL | 2 (7%) | 5 (5%) | |

| POD24 (R-CHOP)‡ | |||

| Yes | 10 (48%) | 13 (23%) | .037† |

| No | 11 (52%) | 43 (77%) | |

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

The χ2 test was used for comparisons.

Significant P values (<.05).

The calculation was based on 135, 134, 124, 129, 115, 100, 90, 131, or 77 samples with available data.

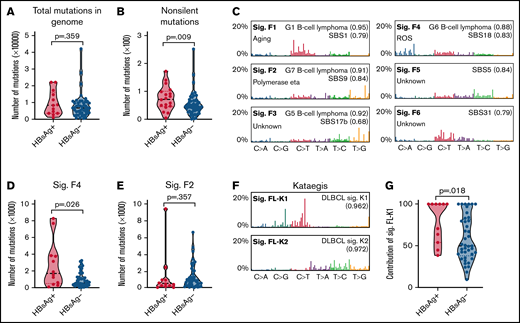

Enhanced mutagenesis in HBsAg+ FLs

To investigate the overall genomic changes and identify the potential difference between HBsAg+ and HBsAg− FLs, we performed WES (n = 15) or WGS (n = 61) on DNAs prepared from tumor/control samples from 76 FL patients (discovery cohort; 18 were HBsAg+). A median of 128 (55-205) or 6737 (561-41 946) somatic mutations per tumor was observed in samples sequenced by WES or WGS, respectively. Among these, a median of 56 (24-106, WES) or 45 (0-251, WGS) nonsilent mutations in coding regions per tumor were observed. There was a trend for increased mutation load in the whole genome of the HBsAg+ FLs (median, 8383 vs 6658; Figure 1A), and in the coding regions, significantly more nonsilent mutations per tumor were observed in HBsAg+ FLs (median, 72 vs 43; Figure 1B).

Enhanced mutagenesis and enrichment of selected mutational signatures in HBsAg+ FLs. (A-B) Comparison of the mutation load in the whole genome (A) or coding genome (B) between HBsAg+ and HBsAg− FLs. (C) Mutational signatures were identified according to the 96-substitution classifications from 61 pairs of FL/control samples sequenced by WGS. (D-E) Comparison of Sig.F4 and Sig.F2 in HBsAg+ and HBsAg− FLs. (F) Two mutational signatures (Sig.FL-K1 and Sig.FL-K2) of kataegis were identified in FL genomes. (G) Comparison of the contribution of Sig.FL-K1 to kataegis identified in HBsAg+ and HBsAg− FLs. The numbers in brackets in panel C and panel F represent the cosine similarities between current signatures and indicated signatures. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to calculate the P value. ROS, reactive oxygen species; sig., signature.

Enhanced mutagenesis and enrichment of selected mutational signatures in HBsAg+ FLs. (A-B) Comparison of the mutation load in the whole genome (A) or coding genome (B) between HBsAg+ and HBsAg− FLs. (C) Mutational signatures were identified according to the 96-substitution classifications from 61 pairs of FL/control samples sequenced by WGS. (D-E) Comparison of Sig.F4 and Sig.F2 in HBsAg+ and HBsAg− FLs. (F) Two mutational signatures (Sig.FL-K1 and Sig.FL-K2) of kataegis were identified in FL genomes. (G) Comparison of the contribution of Sig.FL-K1 to kataegis identified in HBsAg+ and HBsAg− FLs. The numbers in brackets in panel C and panel F represent the cosine similarities between current signatures and indicated signatures. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to calculate the P value. ROS, reactive oxygen species; sig., signature.

Based on WGS data from 61 pairs of tumor/control samples, 6 genome-wide mutational signatures were subsequently deciphered using SigProfiler32 and compared with the COSMIC single base substitution signature reference database (SBS1-94)33,34 and previously described B-cell lymphoma genome-wide signatures (G1-G7)35 (Figure 1C; supplemental Figure 1). Sig.F1 was similar to signatures G1 and SBS1, which are associated with age.33,34 Sig.F2 was most similar to the G7 signature,35 which is B-cell lymphoma–specific and is associated with polymerase η activity and the rate of mutations in the immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region.33,35 Sig.F4 was similar to the G6 signature (unknown etiology) and the SBS18 signature (possibly damaged by reactive oxygen species). Sig.F3, Sig.F5, and Sig.F6 could be assigned to previously described signatures but with undefined etiologies. The number of mutations that can be assigned to Sig.F4 was significantly higher in HBsAg+ FLs (Figure 1D). Conversely, mutations assigned to other signatures, including the B-cell–specific Sig.F2 (Figure 1E), were comparable between HBsAg+ and HBsAg− FLs. Thus, we observed an increased mutational load in the coding regions of HBsAg+ FLs, and mutations in the genome are associated with selected mutational signatures.

Kataegis in the HBsAg+ FL genome are associated with the activity of activation-induced deaminase (AID)

Clustered somatic mutations in cancer genomes, often referred to as kataegis, can be used as a fingerprint of the mutagenic process,36 and their signatures have been linked to the different subtypes of DLBCL and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.35 To further explore the underlying mutagenesis in FL, we characterized the kataegis in the 61 FL genomes sequenced by WGS. A total of 346 kataegis containing 8482 mutations, accounting for 1.7% of the total somatic mutations, were identified. On average, 5.7 kataegis were identified per genome. There was no significant difference in the number of kataegis between HBsAg+ and HBsAg− FLs (average, 5.7 vs 6.9, P = .196). However, we noticed that kataegis in the BCL2 region were totally absent in HBsAg+ FLs (supplemental Table 3; 0% vs 55% in HBsAg− FLs, P < .001).

Two mutational signatures were subsequently extracted from the 346 kataegis: Sig.FL-K1 and Sig.FL-K2 (Figure 1F), which were highly similar to the previously described B-cell lymphoma kataegis–signature K1 (AID-related, enriched in switch region and activated B-cell-like [ABC]-DLBCL) and K2 (polymerase η–related, enriched in variable region and GCB-DLBCL).35 Kataegis identified in HBsAg+ FLs, in contrast to the previously described FL samples (largely HBsAg−)35 and the HBsAg− FLs described here, but similar to ABC-DLBCLs, were mainly contributed by the Sig.FL-K1 (Figure 1G). Thus, highly clustered mutations in the HBsAg+ FL genomes largely result from the aberrant activity of B-cell–specific factor AID during immunoglobulin class-switch recombination.35

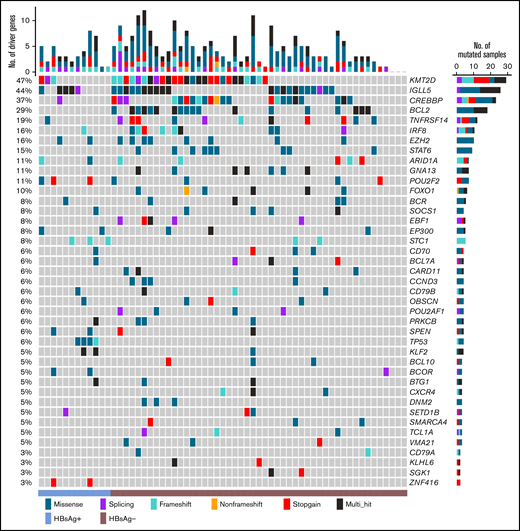

Unique set of mutated genes in HBsAg+ FLs

In the discovery cohort, 162 genes were affected by somatically occurred nonsilent mutations in at least 3 samples (4%, supplemental Table 4), and among these, 40 genes were considered as cancer drivers (Figure 2). The most significantly mutated genes included KMT2D, IGLL5, CREBBP, BCL2, TNFRSF14, IRF8, EZH2, STAT6, ARID1A, and GNA13. Further Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway enrichment analysis of the cancer drivers showed that the HBV infection–associated pathway was one of the most significantly mutated pathways, followed by the FoxO-, Wnt-, JAK-STAT-, BCR-, PI3K-, and NF-κB signaling pathways (supplemental Table 5).

List of the top cancer driver genes in the Chinese FL cohort. Genes affected by somatically occurring, nonsilent mutations in FL samples sequenced by WGS (n = 61) and considered to be significantly mutated (q < 0.05 in ≥2 prediction methods; IntOGen, ActiveDriverWGS, and MutSigCV) are displayed.

List of the top cancer driver genes in the Chinese FL cohort. Genes affected by somatically occurring, nonsilent mutations in FL samples sequenced by WGS (n = 61) and considered to be significantly mutated (q < 0.05 in ≥2 prediction methods; IntOGen, ActiveDriverWGS, and MutSigCV) are displayed.

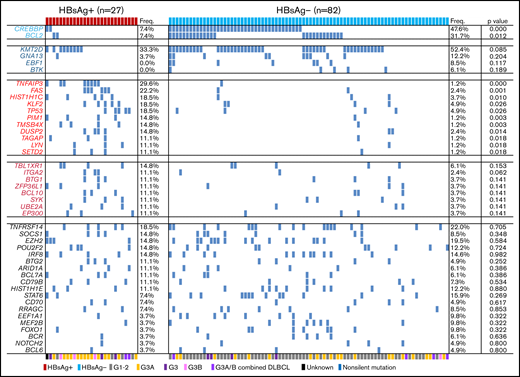

Comparison of somatic mutation patterns in HBsAg+ and HBsAg− FLs. Frequency of nonsilent mutations in HBsAg+ (n = 27) and HBsAg− (n = 82) FLs identified from WES/WGS and/or lymphochip. The histological grades for each sample are marked by different color bars at the bottom. The P value was compared by the χ2 test. G, grade.

Comparison of somatic mutation patterns in HBsAg+ and HBsAg− FLs. Frequency of nonsilent mutations in HBsAg+ (n = 27) and HBsAg− (n = 82) FLs identified from WES/WGS and/or lymphochip. The histological grades for each sample are marked by different color bars at the bottom. The P value was compared by the χ2 test. G, grade.

Based on the mutational profile in the discovery cohort, we noticed that some genes were preferentially mutated in either the HBsAg+ (TP53) or HBsAg− (CREBBP and BCL2) group. To further validate and define preferentially mutated genes in HBsAg+ FLs, 33 additional samples were sequenced by lymphochip.21 The data were subsequently merged, and 51 frequently mutated genes (>5%) were identified in 109 FL samples (27 HBsAg+ FLs) (supplemental Figure 2). Among these, BTG2, UBE2A, CD70, TMSB4X, KLF2, BTK, ZFP36L1, and BCR have not previously been considered as significant mutational targets in FL. In HBsAg+ FLs, 30 genes were affected by nonsilent mutations in at least 3 samples (11%), with KMT2D, TNFAIP3, FAS, HISTIH1C, KLF2, TP53, and TNFRSF14 as the most frequently mutated genes (supplemental Table 6).

We next directly compared the mutation patterns between HBsAg+ and HBsAg− FLs. Two genes, CREBBP and BCL2, which are usually highly mutated in FLs, were mutated at a significantly lower level in HBsAg+ FLs. In contrast, 11 genes (TNFAIP3, FAS, HIST1H1C, KLF2, TP53, PIM1, TMSB4X, DUSP2, TAGAP, LYN, and SETD2) were mutated at a significantly higher level in HBsAg+ FLs. Moreover, the mutation prevalence of some genes was somewhat lower (KMT2D, GNA13, EBF1, and BTK) or higher (TBL1XR1, ITGA2, BTG1, and ZFP36L1) in HBsAg+ FLs, although the differences did not reach statistical significance. These findings may explain the somewhat different mutational profile in the Chinese FL patients compared with that in the Western FL cohorts (previously published cohorts, altogether 199 patients,5-9 and a Swedish FL cohort27 sequenced by lymphochip, 100 patients), where a lower frequency of KMT2D, CREBBP, and BCL2 mutations was noted in Chinese patients (supplemental Figure 3).

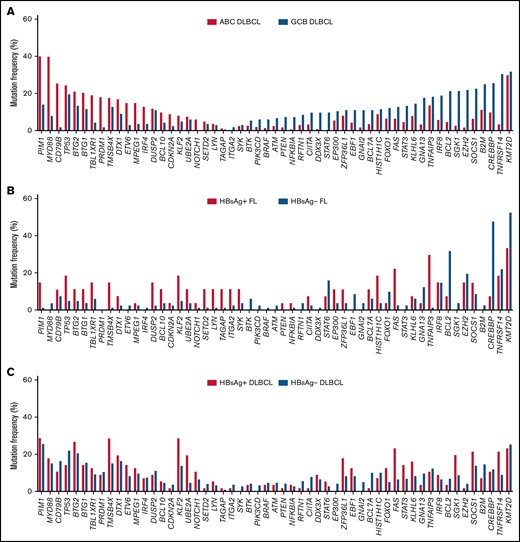

As the mutagenesis process in HBsAg+ FLs showed some similarities with ABC-DLBCLs, we next summarized the prevalence of mutational targets in DLBCL18 (Figure 4A). Indeed, compared with the HBsAg− FLs, HBsAg+ FLs preferentially harbored mutations in some of the ABC-DLBCL mutational targets, such as PIM1, BTG1/2, TBL1XR1, and DTX1, and were less likely mutated in GCB-DLBCL mutational targets, such as CREBBP, BCL2, and GNA13 (Figure 4B). However, unlike ABC-DLBCLs, HBsAg+ FLs had no mutations in MYD88, PRDM1, and IRF4. Compared with the current known molecular subtypes of DLBCL,19 the preferentially mutated genes in HBsAg+ FL are distributed in several subtypes, such as C1 (TNFAIP3 and FAS), C2 (TP53), C4 (HIST1H1C), and C5 (PIM1), indicating that HBsAg+ FLs do not resemble any of the molecular subtypes of DLBCL. The frequently mutated genes in HBsAg+ FLs further overlapped with some (TMSB4X, KLF2, UBE2A, ZFP36L1, and FAS), but not all, preferred targets in HBsAg+ DLBCLs (Figure 4C). Taken together, these data showed that HBsAg+ FLs displayed a unique mutation pattern that differed from conventional FLs and various subtypes of DLBCLs.

HBsAg+ FLs display a distinctive mutation profile, partially overlapping with ABC-DLBCL and HBsAg+ DLBCL. (A) Highly mutated genes in ABC-DLBCL (n = 295) and GCB-DLBCL (n = 164) from the dataset described previously.18 The gene list includes the most differentially mutated genes in ABC-DLBCL or GCB-DLBCL with a P value <.05 in >3% of the DLBCL patients, and important genes are presented in Figure 3. (B) Prevalence of mutations in genes listed in panel A in HBsAg+ FLs and HBsAg− FLs. (C) Prevalence of mutations in genes listed in panel A in HBsAg+ DLBCLs and HBsAg− DLBCLs from the data described previously.21

HBsAg+ FLs display a distinctive mutation profile, partially overlapping with ABC-DLBCL and HBsAg+ DLBCL. (A) Highly mutated genes in ABC-DLBCL (n = 295) and GCB-DLBCL (n = 164) from the dataset described previously.18 The gene list includes the most differentially mutated genes in ABC-DLBCL or GCB-DLBCL with a P value <.05 in >3% of the DLBCL patients, and important genes are presented in Figure 3. (B) Prevalence of mutations in genes listed in panel A in HBsAg+ FLs and HBsAg− FLs. (C) Prevalence of mutations in genes listed in panel A in HBsAg+ DLBCLs and HBsAg− DLBCLs from the data described previously.21

Lack of BCL2/IGH translocation in HBsAg+ FLs

BCL2/IGH translocation is not only a well-known molecular hallmark of FL but also an important marker to distinguish the cell-of-origin of DLBCL.18,19 By analyzing the WGS data, a total of 35 FL tumors (57.3%) had translocations involving BCL2 and IGH loci. This is consistent with previous findings that, in general, BCL2/IGH translocation was less often identified in Chinese FL patients.37 Consistent with a previous report,35 the corresponding IGH translocation breakpoints were located in the IGHD or IGHJ gene loci, suggesting that aberrant joining events might have occurred during V(D)J recombination in bone marrow B cells.38 Strikingly, only 1 BCL2/IGH translocation was identified from 12 HBsAg+ FLs in the WGS cohort (8% vs 71% in HBsAg− FLs; P < .001). Neither MYC/IGH nor IRF4/IGH translocations were identified, and BCL6/IGH translocation was observed only in 3 samples (1 in HBsAg+ FL, grade 3B; 2 in HBsAg− group, grade 2/3A). Together with the observation of fewer mutations in BCL2 and CREBBP in HBsAg+ FLs, our data suggest that the initiation of FL in HBV-infected patients seems to be unrelated or less dependent on the genetic alterations in BCL2 and CREBBP.

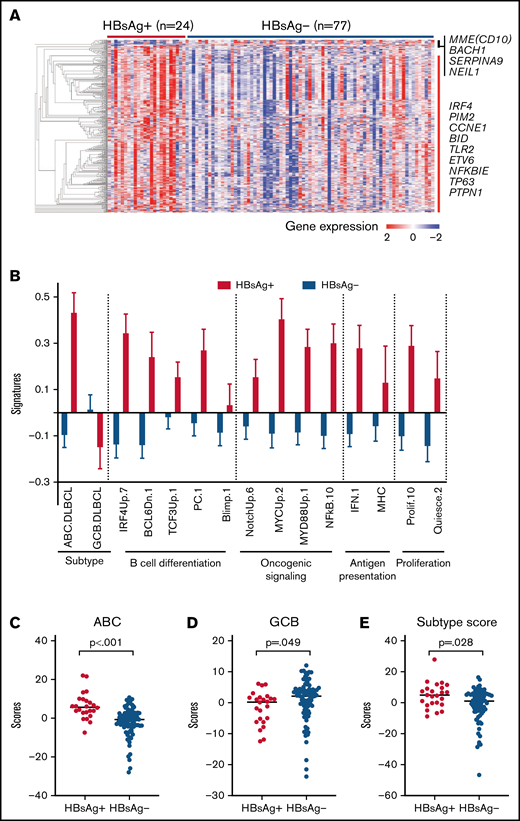

Gene-expression profiling showed an “ABC-like” signature in HBsAg+ FLs

We next characterized the transcriptomes of 101 FL tumors (24 HBsAg+). There is no significant enrichment of HBsAg+ FLs in any risk groups (supplemental Figure 6) predicted by PRIMA-23 scores.17 However, a distinct gene-expression profile was observed in HBsAg+ FLs compared with HBsAg− FLs (Figure 5A; supplemental Table 7). Furthermore, gene set enrichment analysis of these differentially expressed genes revealed the enrichment of several pathways in HBsAg+ FLs, involving the cell cycle/DNA replication, EBV/human T-cell lymphotropic virus 1/HBV infection, apoptosis process, p53, NF-κB, and BCR signaling pathways (supplemental Table 8). Among the differentially expressed genes, several (IRF4, ETV6, PTPN1, MME [CD10], and SERPINA9) have been specifically used to characterize the cells-of-origin of DLBCL.39,40 Using the signatures of pathways that might be important for lymphomagenesis,18 we further showed that ABC-DLBCL–associated genes41 were highly expressed in HBsAg+ FLs, along with expression signature of B-cell differentiation, oncogenic signaling, antigen presentation, and proliferation (Figure 5B). In contrast, only GCB-DLBCL–related genes were highly expressed in HBsAg− FLs. Notably, HBsAg+ FLs are associated not only with high IRF4 expression but also with the genes transactivated by IRF4, a key marker of ABC-DLBCL. Furthermore, HBsAg+ FLs indeed displayed higher ABC-DLBCL–subtype scores using the classification model of ABC-/GCB-DLBCL described previously40 (Figure 5C-E). This became even more evident when we performed an unbiased analysis on all FL and DLBCL samples, and the majority of HBsAg+ FL samples showed “ABC”-like gene-expression signature, regardless of the histological grades, whereas most of the HBsAg− FLs presented a “GCB”-like gene-expression signature (supplemental Figure 4). Notably, HBsAg+ DLBCLs did not show any preference for the “ABC”-like or GCB like signatures (supplemental Figure 4). Taken together, HBsAg+ FL displayed distinct gene-expression profiles that were more closely linked to the ABC-DLBCL–related signature and additional B-cell activation signaling pathways.

HBsAg+ FLs display a distinct gene expression pattern. (A) HBsAg+ FLs showed a distinct gene expression profile. The normalized expression levels were analyzed using Qlucore Omics Explorer software. Significantly and differentially expressed genes between HBsAg+ (n = 24) and HBsAg− (n = 77) FLs were used to draw the heatmap. (B) Comparison of expression signatures in HBsAg+ and HBsAg− FLs. The expression signatures were determined using gene sets (https://lymphochip.nih.gov/signaturedb/) based on previously described methods.66 (C-E) HBsAg+ FLs expressed higher levels of genes associated with ABC-DLBCLs (C) and lower levels of genes associated with GCB-DLBCLs (D), giving rise to an ABC-like phenotype in general (E). The analysis of ABC and GCB scores was performed based on previously described methods.40 The Mann-Whitney U test was used to calculate the P value.

HBsAg+ FLs display a distinct gene expression pattern. (A) HBsAg+ FLs showed a distinct gene expression profile. The normalized expression levels were analyzed using Qlucore Omics Explorer software. Significantly and differentially expressed genes between HBsAg+ (n = 24) and HBsAg− (n = 77) FLs were used to draw the heatmap. (B) Comparison of expression signatures in HBsAg+ and HBsAg− FLs. The expression signatures were determined using gene sets (https://lymphochip.nih.gov/signaturedb/) based on previously described methods.66 (C-E) HBsAg+ FLs expressed higher levels of genes associated with ABC-DLBCLs (C) and lower levels of genes associated with GCB-DLBCLs (D), giving rise to an ABC-like phenotype in general (E). The analysis of ABC and GCB scores was performed based on previously described methods.40 The Mann-Whitney U test was used to calculate the P value.

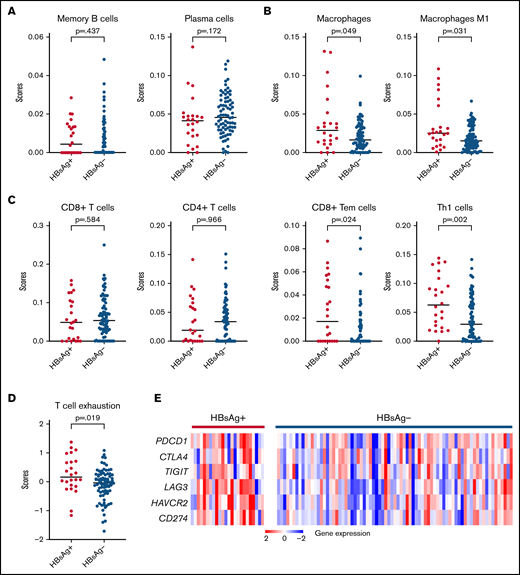

TME in HBsAg+ FLs

Increased expression levels of interferon-associated genes, which play critical roles in the antitumor response in the tumor microenvironment (TME),42 were noted in HBsAg+ FLs (Figure 5A). To explore the characteristics of TME in FLs, we predicted the major tumor-infiltrating cell types based on the transcriptome data using default cell-type signatures from xCell (supplemental Table 9). Focusing on immune cell types, we observed no changes in the infiltration of memory/plasma B cells between the HBsAg+ and HBsAg− groups (Figure 6A). In contrast, the infiltration of macrophages, especially the proinflammatory M1-subset, was significantly increased in HBsAg+ FLs (Figure 6B). Furthermore, even though there was no significant difference in the infiltration of CD8+ or CD4+ T cells, the infiltration of a subset of CD8+ T (CD8+ Tem) or CD4+ T (Th1) cells was significantly increased in HBsAg+ FLs (Figure 6C). Moreover, a significantly higher score of 6 coinhibitory receptors (PDCD1, CTLA4, TIGIT, LAG3, HAVCR2, and CD274/PD-L1) was observed in HBsAg+ FLs (Figure 6D-E), suggesting a relatively high level of T-cell exhaustion in these tumors. Taken together, our data suggest that HBsAg+ FLs may display a different TME, with an increased infiltration of CD8+ memory T cells, CD4+ Th1 cells, and M1-macrophages and increased T-cell exhaustion.

HBsAg+ FLs display a different TME. (A-C) Comparison of different types of tumor-infiltrating immune cells in HBsAg+ (n = 24) and HBsAg− (n = 77) FLs, including B-cell types (A), macrophages (B), and T-cell types (C). RNAseq data were used to predict tumor-infiltrating immune cells based on the online tool xCell (https://xcell.ucsf.edu/). (D-E) Dot plot (D) and heatmap (E) show increased T-cell exhaustion in tumor cells from HBsAg+ FLs. A 6-gene panel (PDCD1, CTLA4, TIGIT, LAG3, HAVCR2, and CD274/PD-L1) was used to generate a score of T-cell exhaustion. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to calculate the P value. RNAseq, RNA sequencing.

HBsAg+ FLs display a different TME. (A-C) Comparison of different types of tumor-infiltrating immune cells in HBsAg+ (n = 24) and HBsAg− (n = 77) FLs, including B-cell types (A), macrophages (B), and T-cell types (C). RNAseq data were used to predict tumor-infiltrating immune cells based on the online tool xCell (https://xcell.ucsf.edu/). (D-E) Dot plot (D) and heatmap (E) show increased T-cell exhaustion in tumor cells from HBsAg+ FLs. A 6-gene panel (PDCD1, CTLA4, TIGIT, LAG3, HAVCR2, and CD274/PD-L1) was used to generate a score of T-cell exhaustion. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to calculate the P value. RNAseq, RNA sequencing.

Discussion

Integrated genomic studies have helped us to understand the mechanism underlying disease initiation, progression, and transformation of FL43 and have facilitated the establishment of risk models to predict the outcome of FL patients.15,17 However, most of these data were derived from FL patients from Western countries. To date, very limited genomic/epigenomic data are available for FL patients with different ethnic backgrounds. It has been shown that the incidence and distribution of lymphoma subtypes differ significantly between patients from East Asia and Western countries, where T-/natural killer–cell lymphomas are proportionally higher in East Asia, whereas some B-cell lymphomas, for example FL, are proportionally lower.44 Furthermore, a recent multicenter study showed that Chinese FL patients were significantly younger at diagnosis than Western FL patients (median age, 53 vs 61) and more likely involved extranodal sites but less frequently infiltrated bone marrow.45,46 Unique somatic mutation profiles have been identified in DLBCL and T-/natural killer–cell lymphomas from Chinese patients.44,47 Herein, we studied the clinical characteristics of 135 Chinese FL patients and performed comprehensive genomic/transcriptomic analyses of 109 samples using NGS methods. We observed that ∼24% of Chinese FL patients had HBsAg seropositivity, and these patients were younger, had a higher histological grade at diagnosis, and a higher incidence of POD24. Moreover, HBsAg+ tumors showed a higher mutation load in the coding genome and distinct mutational and gene-expression patterns. Our data further link chronic HBV infection and B-cell lymphomagenesis and also provide a plausible explanation for why the clinical features and mutational profile were different between Chinese and Western FL patients. It is of note, however, that even the HBsAg− Chinese FL patients in our cohort seemed to be younger than the patients from the Western cohort, with 69% younger than 60 years (Table 1). Thus, additional factors (genetic and environmental), which remain to be defined, may contribute to the difference observed in various patient populations.

FL is believed to arise from developmentally blocked GCB cells and has similar cell-of-origin as GCB-DLBCL.15 In addition to the crucial role of t(14;18) translocation in FL, genetic alterations in histone-modifying genes are also considered early events during the malignant transformation of FL precursors.15 Lack of the classical BCL2/IGH translocation and CREBBP mutations in HBsAg+ FLs thus suggest a different initiation factor and possibly different cell-of-origin of these tumors, compared with conventional FLs. Indeed, the HBsAg+ FLs exhibited higher expression of ABC-DLBCL–related gene-sets. Similar to these findings, it has previously been shown that FLs without BCL2/IGH translocation had enrichment of ABC-like, NF-κB, and proliferation gene-expression signatures.48 Furthermore, the highly clustered mutations in the HBsAg+ FL genomes showed similar features as those in the ABC subtype of DLBCL, with footprints of AID activity. Thus, similar to a subset of ABC-DLBCLs, HBsAg+ FLs may have arisen either from different stages of GC (compared with conventional FLs and GCB-DLBCLs) or from extrafollicular B cells (without entering GC).49

EBV and HCV have been shown to play a role in lymphomagenesis of FL, and there is a significant association of a higher grade in FL patients infected by these viruses.50,51 It is also evident that FL patients with HCV infection can potentially be cured by antiviral therapy.52 In our study, we observed that HBsAg+ FL patients were also significantly associated with a higher grade, which may suggest a common mechanism underlying the development of FL in EBV-, HCV-, and HBV-infected individuals. For instance, TNFAIP3, a negative regulator of NF-κB signaling, is highly mutated in HBsAg+ FLs (30%) but rarely mutated in HBsAg− FLs (1%). In another study on HCV-infected patients, a genetic variant of TNFAIP3 was shown to be present only in tumors of HCV-infected NHL patients.53 Consistent with the high expression of NF-κB and proliferation signaling in HBsAg+ FLs, it is possible that NF-κB signaling activated by TNFAIP3 mutations may provide a survival or proliferation signal to tumor cells in HBV-infected FLs. Another possible mechanism is that HBV protein may interact with transcription factors of the host to regulate gene-expression networks.54 For instance, the interaction of HBx and acetyltransferases CREB-binding protein/p300 could facilitate the recruitment of these coactivators onto CREB-responsive promoters, leading to the activation of gene expression.54 Indeed, CREBBP-bound genes were significantly upregulated in HBsAg+ FLs compared with HBsAg− FLs (supplemental Figure 5). This may thus explain the lower dependence on the CREBBP mutations of HBsAg+ FLs as the interaction between HBx and CREB-binding protein/p300 may mimic the role of mutated CREBBP in the early stage of lymphomagenesis.

The above observations suggest that the molecular shift of HBsAg+ FL might be driven by HBV infection. Additional mechanisms connecting HBV and lymphomagenesis have also been considered. HBV DNA may integrate into the host genome and induce chromosome instability or alter the function of cancer drivers.55 We were not able to find evidence of integration of HBV DNA into the genome of FL tumors using the WGS data. However, we indeed detected free HBV DNA sequences in a subset of HBsAg+ FLs, indicating the presence of HBV viral antigens in tumor cells or in cells within the TME, which resulted in chronic activation of the tumor and/or tumor-infiltrating cells. We sequenced V(D)J regions of IGH from 5 HBsAg+ and 17 HBsAg− FLs and did not find any preference for VH gene–usage or stereotyped complementarity determining region 3.56 However, further experiments are needed to test this hypothesis, for example, by investigating the binding of such BCRs expressed by HBsAg+ FLs and HBV antigens. Nevertheless, our data showed changes in TME, especially an enrichment of exhausted T cells in HBsAg+ FLs, which is consistent with similar findings in HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma.57 Furthermore, we also observed an upregulation of PD-L1 expression in HBsAg+ FLs (Figure 6E, P = .005). Considering that PD-1 was also upregulated on HBV-specific T or B cells in HBV-infected patients,58,59 blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway could restore dysfunctional immune cells in these individuals.58,59 Taken together, these data suggest that the exhaustion of T cells might be a consequence of chronic stimulation from HBV antigens in addition to coinhibitory signals from the lymphoma cells. In either case, inhibition of PD-1/PD-L1 could be a promising approach to treat HBsAg+ FL patients.

Some of those genetic features observed in HBsAg+ FLs, such as lack of BCL2/IGH translocations and CREBBP mutations, are similar to that of PTFL,60,61 a subtype of FL mainly described in children.2 PTFL is characterized by unique clinical features including early stage at diagnosis (I/II), higher grade, male predominance, indolent behavior, and good prognosis,60,61 as well as genetic features such as frequent mutations in TNFRSF14, MAP2K1, and IRF8.60,61 Similarly, primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma also frequently lacks BCL2/IGH translocations but has a high frequency of TNFRSF14 mutations (40%).62 HBsAg+ FL patients who were diagnosed at adult age, with no sex predominance but higher grades and aggressive tumors, often had POD24 following the first-line treatment and had a combination of highly mutated genes, including TNFAIP3, FAS, HIST1H1C, KLF2, TP53, and PIM1. Thus, HBsAg+ FLs are distinct from PTFL and primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma, supporting the previous observations that t(14;18)− FL is a clinically and genetically heterogeneous disease.48,63

In conclusion, we present the first comprehensive genetic/epigenetic study on Chinese FL patients. We showed that approximately one-quarter of these patients had concomitant HBV infection and that HBsAg+ tumors had distinct clinical, genetic, and molecular features. The existing risk prediction models are not optimal to evaluate the outcome of these patients. Based on our results, we propose that HBsAg+ FLs could be classified as a separate subtype with an ABC-like DLBCL cell-of-origin. These patients, which have a poor prognosis, may benefit from different therapeutic strategies, such as antiviral treatment, immune checkpoint blockade therapy, and other targeted therapies tested in ABC-DLBCLs. It is also important to point out that currently ∼300 million people worldwide are living with chronic HBV infection, and the infection burden remains very high in parts of Asia, Africa, and the Western Pacific regions. In a study from South Korea, the researchers also showed that >20% of FL patients were infected with HBV.64 A recent study based on European patients further showed that FL patients with resolved HBV infection (HBsAg−, anti-HBc+) was associated with worse 10-year survival and different mutational targerts.65 Thus, our results from Chinese FL patients may have broad clinical implications. Further investigation on a large cohort of FL patients with concomitant HBV infection and/or non-Chinese ethnic background is required to validate and broaden our findings.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society (Cancerfonden), the Swedish Research Council, the Chinese Natural Science Foundation (grants 81670184, 81872902, 82073917, and 81611130086), Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Human Disease Genomics (grant 2020B1212070028), China National GeneBank (CNGB), STINT (Joint China-Sweden mobility program), Radiumhemmets, the Center for Innovative Medicine (CIMED), and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: W.R. analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript; X.L., H.W., M.Y., and X.Y. performed the bioinformatics analysis; B.M. reviewed the pathological data; X.W., W.L., J.Y., E.K., and H.Z. collected samples and clinical information; X.W., W.L., J.Y., W.J., H.H., Z.-M.L., and H.Z. interpreted the clinical information; D.L. and K.W. supervised the bioinformatics analysis; H.Z., K.W., and Z.-M.L. were involved in study supervision; and Q.P.-H. designed and supervised the study and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Qiang Pan-Hammarström, Department of Biosciences and Nutrition, Karolinska Institutet, 14183 Huddinge, Sweden; e-mail: qiang.pan-hammarstrom@ki.se; Zhi-Ming Li, Department of Medical Oncology, Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou, China; e-mail: lizhm@sysucc.org.cn; Kui Wu, BGI-Shenzhen, Shenzhen, China; e-mail: wukui@genomics.cn; and Huilai Zhang, Department of Lymphoma, Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital, Tianjin, China; e-mail: zhlwgq@126.com.

References

Author notes

W.R., X.W., and M.Y. contributed equally to this study.

Sequencing data can be found in the China National Genebank (https://db.cngb.org/, accession number CNP0002528). Please direct other inquiries to the corresponding author.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.