Key Points

A mutation preventing production of a fibrinogen α-chain isoform (AαE) is a genetic modifier of venous thrombosis in zebrafish.

A functional role for the conserved AαE in early developmental blood clotting is revealed.

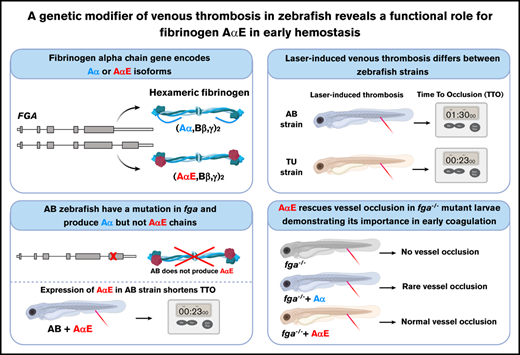

Visual Abstract

Created using Biorender

Abstract

Plasma fibrinogen molecules comprise 2 copies of Aα, Bβ, and γ chains folded into a hexameric protein. A minor fibrinogen isoform with an extended Aα chain (AαE) is more abundant in newborn human blood than in adults. Larval zebrafish produce predominantly AαE-containing fibrinogen, but its functional significance is unclear. In 3-day-old zebrafish, when hemostasis is reliant on fibrinogen and erythrocyte-rich clotting but is largely thrombocyte-independent, we measured the time to occlusion (TTO) in a laser-induced venous thrombosis assay in 3 zebrafish strains (AB, TU, and AB × TL hybrids). AB larvae showed delayed TTO compared with the TU and AB × TL strains. Mating AB with TU or TL produced larvae with a TU-like TTO. In contrast to TU, AB larvae failed to produce fibrinogen AαE, due to a mutation in the AαE-specific coding region of fibrinogen α-chain gene (fga). We investigated whether the lack of AαE explained the delayed AB TTO. Transgenic expression of AαE, but not Aα, shortened the AB TTO to that of TU. AαE rescued venous occlusion in fibrinogen mutants or larvae with morpholino-targeted fibrinogen α-chain messenger RNA, but Aα was less effective. In 5-day-old larvae, circulating thrombocytes contribute to hemostasis, as visualized in Tg(itga2b:EGFP) transgenics. Laser-induced venous thrombocyte adhesion and aggregation is reduced in fibrinogen mutants, but transgenic expression of Aα or AαE restored similar thrombocyte accumulation at the injury site. Our data demonstrate a genetic modifier of venous thrombosis and a role for fibrinogen AαE in early developmental blood coagulation, and suggest a link between differentially expressed fibrinogen isoforms and the cell types available for clotting.

Introduction

The role of fibrinogen as the thrombin substrate is conserved in vertebrate blood clotting.1 The most abundant soluble human fibrinogen is a hexamer of 2 Aα, Bβ, and γ polypeptides, combining to a molecular weight of ∼340 kDa. Variability comes from posttranslational modifications2 and differential messenger RNA (mRNA) splicing giving rise to γ′3 and extended Aα-chain (AαE)4,5 isoforms. The AαE arises from splicing of a sixth exon in the Aα-chain mRNA. This exon encodes a C-terminal globular domain (αEC) with homology to the Bβ- and γ-chain C-terminal regions.5 AαE is only present as 2 copies in human fibrinogen, generating a hexamer of 420 kDa (fibrinogen 420).4 Despite being represented in only ∼1% of circulating fibrinogen, the αEC domain of AαE is highly conserved,6 suggesting functional importance. The proportion of fibrinogen 420 in newborn blood is considerably higher than later in life.7

Despite its description over 25 years ago,5 the role and importance of the αEC domain of AαE remains somewhat enigmatic. Studies of the αEC domain structure,8 fibrinogen 420–containing fibrin clots,9 and their dissolution,10 have been reported. One proposed function for the αEC domain is as an additional binding site for leukocyte interactions with fibrinogen or fibrin via integrin receptors.11 The αEC domain can be seen as nodes bulging from fibrin fibers,9 inferring an exposed binding region for cellular interactions. However, in which context this interaction is important in vivo is not clear.

The zebrafish (Danio rerio) fibrinogen α-chain gene (fga) encodes both Aα and AαE isoforms,12 also due to differential splicing of a sixth exon.5 The αEC domain of AαE in zebrafish is over 60% identical to human αEC and both span 236 aa. The zebrafish has emerged as a model for thrombosis and hemostasis studies13 due to the conservation of coagulation proteins14 and the successful adaptation of in vivo hemostasis tests using transparent zebrafish larvae.15-19 In addition, targeted mutations in a number of coagulation-related proteins, including fibrinogen,20,21 have demonstrated the zebrafish’s utility in modeling factor deficiencies and for assessing the impact of patient-derived polymorphisms.22-25 Zebrafish have nucleated thrombocytes,26 which are considered cellular equivalents to platelets in hemostasis. They participate in blood clotting in a platelet-like manner, rapidly binding and aggregating at injury sites.27-30

In previous work, we noticed the presence or absence of fibrinogen AαE chains in the plasma fibrinogen of adult zebrafish.20 This was attributed to a single-nucleotide deletion in the sixth exon of fga in a laboratory strain, predicted to cause a translational frameshift, preventing production of AαE and fibrinogen containing the αEC domain. Here, we describe how strain-to-strain variability in a laser-induced venous thrombosis assay in zebrafish larvae has a genetic basis that we assign to the fga exon 6 variant. Homozygosity of the deletion in the AB laboratory zebrafish strain prevents AαE expression and leads to prolonged venous thrombosis times compared with a different laboratory strain (TU). Without the deletion, TU larvae express predominantly AαE-containing fibrinogen and support rapid thrombosis in response to laser injury. Whole-genome sequencing also identified the deletion in an AB × TL hybrid strain, with similar effects on larval venous thrombosis. Genetic complementation and expression of Aα or AαE highlighted the importance of the AαE in early blood clotting, and we used transgenic reporters to monitor erythrocyte and thrombocyte activity in this setting. We demonstrate the utility of zebrafish for identifying a genetic modifier of venous thrombosis, an early developmental role for the AαE chain with its αEC domain, and differences in the abilities of fibrinogen with Aα chains or AαEs to promote thrombosis upon vessel injury.

Methods

Zebrafish

Adult zebrafish were maintained at 26°C, pH 7.5, and 500 µs conductivity. fga mutants, and their genotyping, were described previously.20,21 Experimentation was authorized by local veterinary authorities. Tüpfel long fin (TL) and Tübingen (TU) strains were derived by researchers in Tübingen, Germany,31 and might be related. The AB strain originated in the United States, in Oregon (http://zebrafish.org/home/guide.php). Animals with itga2b:EGFP and gata1:DsRed transgenes were gifts from Leonard Zon’s laboratory (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). Developing embryos were raised at 28.5°C. Genotyping of fga exon 6 was performed by Sanger sequencing of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products, amplified using the oligonucleotides fga exon 6 forward: CAGATTGCGTTGAAATCCAGCAG and fga exon 6 reverse: GGTTGGGATGTCCTCTCACTAAC.

Whole-genome sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from adult tails and larval pools of AB × TL hybrid zebrafish using the Qiagen DNeasy Kit. Illumina 150-bp paired-end high-throughput sequencing was made at Novogene (Sacramento, CA). Raw data were aligned to the GRCz10 reference genome using BWA-MEM,32 sorted, and duplicates marked using Sambamba v0.65 (https://lomereiter.github.io/sambamba/index.html) and biobambam (https://github.com/gt1/biobambam2/releases) to generate analysis-ready BAM files. Variants were called within genes defined by Ensembl (GRCz10 v86) using the GATK 3.7 HaplotypeCaller33,34 and snpEff v4.3T35 annotation. Variants within exons and 20-bp flanking regions with a coverage depth of 7 or more in all samples were extracted for further analysis using SnpSift36 and custom python and R scripts.

Plasmids

Plasmids for expression of zebrafish fibrinogen Aα or AαE under the control of a ubiquitin gene (ubb) promoter (subsequently labeled ubi) were prepared by Gateway cloning (Invitrogen). Middle entry clones for Aα and AαE complementary DNAs (cDNAs) were made using attB1- and attB2-tagged oligonucleotides to PCR amplify cDNAs and pDONOR221 (Invitrogen) as a vector for recombination with PCR products, yielding pME-Aα and pME-AαE. These were used in 4-way Gateway recombination reactions with pENTR5′_ubi (Addgene plasmid #27320),37 pDestTol2CG2-U6:gRNA (Addgene plasmid #63156),38 both gifts from Leonard Zon, and p3E polyA from the Tol2kit.39 Final plasmids for transgenesis were named pT2ubi:Aα and pT2ubi:AαE. Our Aα cDNA clone encodes the 456-aa zebrafish Aα chain, the AαE cDNA, and the 684-aa zebrafish AαE. In the shared region spanning from amino acids 1 to 452, at position 286 our Aα clone has a serine whereas our AαE clone an asparagine. This polymorphic residue has been annotated previously (GenBank: BC054946.1 and BC075895.1). To exclude the polymorphism as a source of functional differences measured between Aα chains and AαEs, we used site-directed mutagenesis, with the Q5 kit and protocol (New England Biolabs), to mutate serine 286 to asparagine in pT2ubi:Aα and asparagine 286 to serine in pT2ubi:AαE. Sequences of mutagenesis oligonucleotides are available upon request. Results for laser-induced thrombosis using these mutated plasmids are described in supplemental Figure 2.

Microinjections

One- to 2-cell zebrafish embryos were microinjected with ∼1 nL of injection mixes. These contained Danieau buffer (58 mM NaCl, 0.7 mM KCl, 0.4 mM MgSO4, 0.6 mM Ca(NO3)2, 5.0 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid pH 7.6) and phenol red. Where described, 2 ng of an fga exon 1–intron 1 splice site–targeting antisense morpholino (5′GCATTATATCACTCACCAATGCAGA3′) or a 5-nt mismatch control (5′GCTTAATATGACTCACGAATCCAGA3′) were included (Genetools Inc). For transgenic expression of Aα or AαE, injection mixes included ∼25 ng of pT2ubi:Aα or pT2ubi:AαE and ∼35 ng of 5′ capped, in vitro–polyadenylated Tol2 transposase mRNA.

Laser-injury assays and imaging

Three- or 5-day postfertilization (3-dpf or 5-dpf) zebrafish larvae were anesthetized with 0.17 mg/mL MS-222 (Sigma) and placed on their sides in 0.22% low-gelling temperature agarose (Sigma) on glass microscope slides. Using a Leica LMD microscope, laser injuries were targeted to the posterior cardinal vein (PCV), 4 to 5 somites caudal to the cloaca.18 Constant laser power, amplitude, speed, and injury shapes were used for 3-dpf and 5-dpf larvae, respectively. The system has a Leica DM 6500 microscope with an HCX PL FLUOTAR L 20×/0.40 CORR objective (numerical aperture, 0.4) with a Cryslas Laser (maximum pulse energy, 50 µJ; frequency, 80 Hz; wavelength, 355 nm) and images and films were acquired with Leica LMD CC7000 and DFC360 FX cameras using LMD and LAS-AF software, at room temperature. Fluorescence accumulation over time in a constant selected area near the injury site was assessed using MetaMorph (7.1) software for Tg(itga2b:EGFP) or Tg(gata1:DsRed) larvae. To evaluate circulating thrombocyte numbers in 5-dpf fga+/+, fga+/−, and fga−/− fish with the itga2b:EGFP transgene, larvae were prepared as for laser injuries and fluorescence filmed for 1 minute. Green fluorescent protein–positive (GFP+) cells passing through the PCV in 30 seconds were counted. For laser injuries (described in Figure 2), a protocol described formerly was used.24

Reverse transcription qPCR

RNA was purified using TRI Reagent (Invitrogen), treated with DNAse using the TURBO DNA-Free Kit (Invitrogen), and reverse transcribed using M-MLV reverse transcriptase and poly(dT)15 primers (both Promega). Assays used for mRNA quantification presented in supplemental Figure 1 were made using oligonucleotides and single-stranded amplicon template standards (Ultramers; IDT) described in supplemental Table 7, and the SensiFAST SYBR Hi-ROX Kit Bioline) reagent with an Applied Biosystems Step-One Quantitative PCR (qPCR) machine. Assays for fibrinogen mRNA quantification in samples described for experiments using an fga morpholino (accompanying the description of the data in Figure 3) were described previously.20

Immunoblots

Zebrafish larvae were lysed in T-PER (Invitrogen) with protease inhibitors (Roche) and supplemented with sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel loading buffer (NuPAGE; Invitrogen). Samples were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting, as described previously,20 with detection of zebrafish fibrinogen chains using antibodies developed by Covalab and β-actin antibodies from Sigma.

Graphics and statistics

Graphics were prepared and the statistical tests described were made using Prism 8 (GraphPad).

Results

Laboratory zebrafish strains reveal a genetic modifier of venous thrombosis

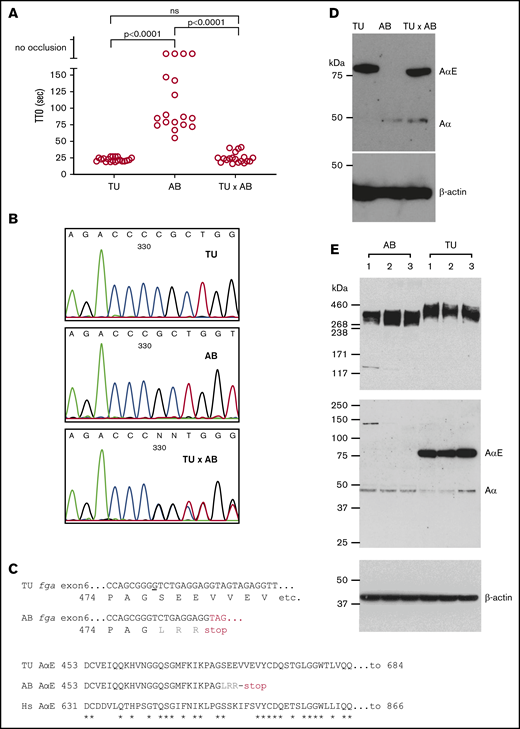

The laser-induced time to occlusion (TTO) of blood in the larval zebrafish PCV has been used as a general readout for blood clotting.15,29,40 In 3-dpf larvae of the TU zebrafish strain, we measured an average TTO of 22.6 seconds (range, 8 seconds; n = 20). In the AB strain, the mean TTO was 89.8 seconds (range, 92 seconds; n = 14). Four AB embryos failed to support occlusion within 3 minutes of the laser injury. This difference suggested strain-specific variance in embryonic hemostasis. To test for a genetic basis of this difference, TU and AB fish were mated and a mean TTO of 25.1 seconds (range, 25 seconds; n = 19) was measured in their offspring (Figure 1A). This result implies that a genetic modifier of developmental venous thrombosis resides in 1 of the strains. As the mean TTO from the TU × AB larvae resembles the TU strain, we reasoned that a recessively transmitted antithrombotic mutation exists in the AB strain or a dominantly transmitted prothrombotic mutation is present in TU.

Variability in laser-induced venous occlusion, an fga exon 6 polymorphism and fibrinogen quantity and quality in zebrafish strains. (A) The TTO after laser injury of the PCV in 3-dpf TU (n = 20), AB (n = 18), or TU × AB (n = 19) larvae is represented. The TU strain TTO is significantly shorter than that of AB, but not significantly different (ns) from that measured in TU × AB larvae (Mann-Whitney U tests). Each circle represents an individual larva. (B) Small stretches of Sanger sequencing chromatograms of part of fga exon 6 PCR-amplified from TU, AB, and TU × AB larvae. The sequencing is in the reverse direction to the fga open reading frame. A single-nucleotide deletion can be seen in the AB strain plot, compared with TU, and then heterozygosity at this position in the TU × AB larvae. (C) The consequences of this single-nucleotide change for AαE translation are highlighted. In the top alignment, the sequences begin with the proline 474 codon; the nucleotide deleted in the AB strain is underlined in the TU DNA sequence. Three missense residues are encoded after the deletion in the AB strain (LRR, in gray) before a TAG (UAG in mRNA) terminator. The bottom alignment shows the AαE sequence from the start of the fga exon 6-encoded residues, in TU, AB, and human (Hs) AαE. In AB, translation is predicted to terminate after 27 codons instead of 236 in TU or human AαE. Asterisks (*) show identical aligned residues in TU and human AαE. (D) An immunoblot for detection of zebrafish fibrinogen AαE and β-actin in whole-larvae lysates from 3-dpf TU, AB, and TU × AB larvae in reduced conditions. (E) For further interstrain comparison, additional blots in which 3 independent pools of AB and TU larvae were used are shown.

Variability in laser-induced venous occlusion, an fga exon 6 polymorphism and fibrinogen quantity and quality in zebrafish strains. (A) The TTO after laser injury of the PCV in 3-dpf TU (n = 20), AB (n = 18), or TU × AB (n = 19) larvae is represented. The TU strain TTO is significantly shorter than that of AB, but not significantly different (ns) from that measured in TU × AB larvae (Mann-Whitney U tests). Each circle represents an individual larva. (B) Small stretches of Sanger sequencing chromatograms of part of fga exon 6 PCR-amplified from TU, AB, and TU × AB larvae. The sequencing is in the reverse direction to the fga open reading frame. A single-nucleotide deletion can be seen in the AB strain plot, compared with TU, and then heterozygosity at this position in the TU × AB larvae. (C) The consequences of this single-nucleotide change for AαE translation are highlighted. In the top alignment, the sequences begin with the proline 474 codon; the nucleotide deleted in the AB strain is underlined in the TU DNA sequence. Three missense residues are encoded after the deletion in the AB strain (LRR, in gray) before a TAG (UAG in mRNA) terminator. The bottom alignment shows the AαE sequence from the start of the fga exon 6-encoded residues, in TU, AB, and human (Hs) AαE. In AB, translation is predicted to terminate after 27 codons instead of 236 in TU or human AαE. Asterisks (*) show identical aligned residues in TU and human AαE. (D) An immunoblot for detection of zebrafish fibrinogen AαE and β-actin in whole-larvae lysates from 3-dpf TU, AB, and TU × AB larvae in reduced conditions. (E) For further interstrain comparison, additional blots in which 3 independent pools of AB and TU larvae were used are shown.

The majority of laboratory zebrafish strains are highly polymorphic with interstrain variation showing heterozygosity at 7% of polymorphic sites.41 The strains described here (AB, TU) and later in the text (an AB × TL hybrid) are commonly used and, to our knowledge, were not developed for any particular phenotypic purposes (also see “Methods”). In previous work,20 we reported a polymorphism in AB zebrafish when developing fibrinogen-deficient animals mutated in fga. In some fish, a single-nucleotide deletion, compared with a TU strain–derived reference sequence, was detected in exon 6 of fga. This difference is also present in an AB-derived mRNA sequence (Genbank:BC054946.1). Exon 6 of fga encodes the αEC domain of the extended AαE isoform. The deletion is predicted to frameshift the AαE mRNA. Supporting this, we detected Aα but not AαE in the plasma of animals with the deleted nucleotide.20 Figure 1B shows the local exon 6 DNA sequence in TU, AB, and TU × AB zebrafish, confirming the polymorphism. Figure 1C shows aligned sequences for part of fga exon 6, highlighting the differences detected and their predicted consequences. We subjected protein lysates from 3-dpf TU, AB, and TU × AB larvae to immunoblotting with anti-zebrafish Aα-chain antibodies, which were raised to an antigen common to Aα and AαE. At 3 dpf, the fibrinogen α chain seen in TU larvae was almost exclusively AαE. In AB larvae, the AαE was not detected, and only a comparatively low amount of the Aα chain. In TU × AB lysates, both α chains were detected, but predominantly AαE (Figure 1D).

To assess the relative amounts of Aα chains and AαEs in both strains, we took protein lysates and RNA samples from pools of 20 embryos (3 dpf) from 3 independent matings of each strain. Immunoblots for fibrinogen detected similar amounts of fibrinogen hexamers, with an increased size seen in the TU strain (Figure 1E top panel). With reduced samples, the absence of the AαE in the AB strain and presence in the TU strain (Figure 1E middle panel) was confirmed, explaining the size difference of detected hexamers. The Aα chain in the 2 strains migrated at the same rate, close to the predicted molecular weight of 50 kDa, and is therefore expected to be the normal Aα chain in AB larvae and not a truncated form of AαE that could be translated from the mutated AαE mRNA (predicted mass, 52.3 kDa).

As accurately quantifying circulating fibrinogen in 3-dpf zebrafish larvae is not currently possible, we measured the mRNA levels of the different fibrinogen chains in 3-dpf embryo pools by reverse transcription qPCR. We used an assay common to all fga mRNAs and specific tests for the Aα and AαE mRNA isoforms. Expressed as a percentage of actb2 mRNA, a higher level (1.3-fold) of fga mRNA was measured in the TU strain, compared with AB, whereas Aα mRNA was more abundant in AB (1.7-fold vs TU) and AαE clearly more present in TU (2.7-fold).

Spliced AαE mRNA is present in the AB strain, at a lower level than in TU, with its frameshift preventing AαE protein expression. No significant differences were measured between strains for fgb and fgg mRNAs (supplemental Figure 1).

We hypothesized that the fga exon 6 polymorphism could lead to effects on fibrin-based coagulation, seen as the genetic modifier of laser-induced TTO in our zebrafish strains and hinting at a role for AαE (and the αEC domain) in early developmental blood clotting.

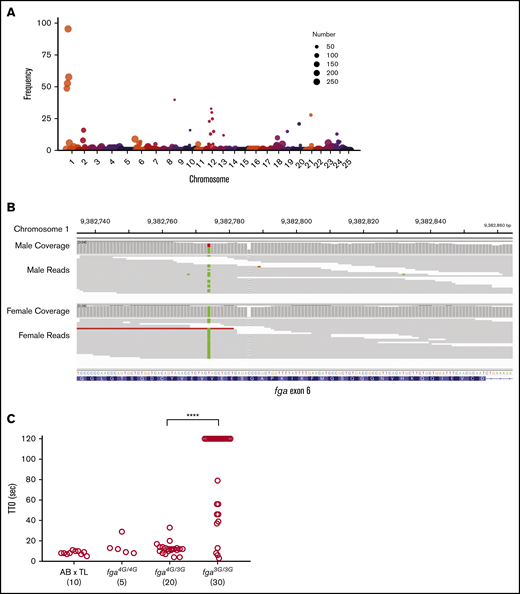

In a distinct colony of AB × TL strain hybrid fish, a similar pattern of delayed TTO was observed. Two adults were crossed and 56 larval offspring underwent laser-induced TTO tests at 3 dpf. Forty-two formed occlusions within 120 seconds and 14 failed to occlude, supporting a recessive inheritance pattern for delayed TTO. Genomic DNA was extracted from both parents. In a separate experiment, sibling wild-type larvae were subjected to endothelial injury and separated into groups, those occluding vs nonoccluding. From these, 1 pool of 20 occluding larvae and 2 replicate pools of 7 nonoccluding larvae were produced. Samples were processed for high-throughput sequencing to identify the causative variant. Following sequencing, 881 793 variants were identified within exons and flanking regions with informative coverage across all samples. From the total variants, 393 734 were identified as informative markers for being heterozygous in 1 parent and nonreference (heterozygous or homozygous) in the other. This enabled the broadest sensitivity in detecting recessive traits. From the informative markers, 5437 variants were homozygous in both nonoccluding pools and heterozygous in the occluding pool. For visualization, the genome was separated into 3 million base-pair intervals. In each, the frequency of homozygosity was calculated by dividing the number of homozygous markers by the number of informative markers. A major peak of homozygosity was seen centered in chromosome 1 from 9 million to 12 million base pairs (Figure 2A). Within this region were 166 missense mutations and 1 frameshift mutation, the latter was the single base-pair G-nucleotide deletion in exon 6 of fga (Figure 2B). Surprisingly, the entire region was found to be heterozygous in the male parent but homozygous for all variants in the female. Laser injury followed by genotyping revealed that lack or delay of occlusion correlates with the fga genotype in a recessive pattern (Figure 2C). Rapid occlusion in 4 of these larvae homozygous for the G deletion, with the mapping data, supports the existence of 1 or more strain-specific suppressor mutations of the nonoccluding phenotype.

Whole-genome sequencing reveals the fga exon 6 polymorphism in the AB × TL genetic background. (A) Frequency of homozygous markers moving across the genome in 3 million base-pair intervals identifies a major peak on chromosome 1 in the region of the fga locus. The circle size represents the number of informative markers in that interval. Circles with the number 250 represent a range from 250 to 4500, for easier visualization. (B) Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) visualization of whole-genome sequencing data for fga exon 6. The arrow indicates the site of the GGGG/GGG exon 6 polymorphism; male is heterozygous and female is homozygous GGG. Read coverage is >20 for the entire region. (C) AB × TL fish hybrids that are not homozygous for the exon 6 (3G) polymorphism display rapid vessel occlusion of the PCV in response to laser injury. Offspring produced from group matings of parents with mixed fga genotypes were subjected to laser injury and TTO analysis, followed by genotyping. Larvae homozygous for the 3G polymorphism displayed an increased TTO. fga4G/4G, fga4G/3G, and fga3G/3G indicate fga exon 6 GGGG or GGG alleles, respectively. ****P < .0001 when the data from bracketed groups were compared in a Mann-Whitney U test.

Whole-genome sequencing reveals the fga exon 6 polymorphism in the AB × TL genetic background. (A) Frequency of homozygous markers moving across the genome in 3 million base-pair intervals identifies a major peak on chromosome 1 in the region of the fga locus. The circle size represents the number of informative markers in that interval. Circles with the number 250 represent a range from 250 to 4500, for easier visualization. (B) Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) visualization of whole-genome sequencing data for fga exon 6. The arrow indicates the site of the GGGG/GGG exon 6 polymorphism; male is heterozygous and female is homozygous GGG. Read coverage is >20 for the entire region. (C) AB × TL fish hybrids that are not homozygous for the exon 6 (3G) polymorphism display rapid vessel occlusion of the PCV in response to laser injury. Offspring produced from group matings of parents with mixed fga genotypes were subjected to laser injury and TTO analysis, followed by genotyping. Larvae homozygous for the 3G polymorphism displayed an increased TTO. fga4G/4G, fga4G/3G, and fga3G/3G indicate fga exon 6 GGGG or GGG alleles, respectively. ****P < .0001 when the data from bracketed groups were compared in a Mann-Whitney U test.

From these data, we concluded that (1) when produced, the AαE is the major fibrinogen α chain in larval zebrafish; (2) crossing TU or TL strains with AB coincides with increased fibrinogen containing the AαE and rescue of a delayed TTO phenotype; and (3) the single-nucleotide deletion in fga could be the molecular basis of the genetic modifier of venous thrombosis.

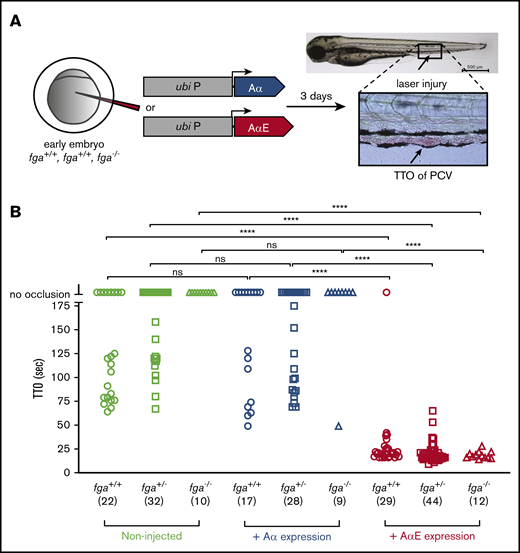

Fibrinogen AαE, but not Aα, restores a thrombotic response in fga mutants

The delayed TTO phenotype in our AB zebrafish larvae, compared with TU, could be due to low fibrinogen production as well as an incapacity to produce the AαE, although detection of fibrinogen hexamers in larval lysates suggests similar overall levels (Figure 1E). As fibrinogen-deficient zebrafish larvae fail to support laser-induced venous thrombosis,21 we reasoned that by reintroducing expression in homozygous fga-mutant embryos, we could compare the relative activity of Aα and AαE isoforms. Using microinjection of a Tol2 transposon-based expression system,42 we expressed Aα or AαE cDNA under the control of the ubi promoter,37 in embryos from fga+/− in-crosses, and measured laser-induced TTO (Figure 3A). Using heterozygous in-crosses, the genotype of larvae could be assessed after TTO analyses, avoiding potential bias. This method has been used to demonstrate complementation of various coagulation factor mutants.21,24,25 The genetic background of our mutant line was largely AB (mutation 1 in Fish et al20 ). Noninjected fga+/+ or fga+/− larvae had variable laser-induced TTOs and occlusion could not be measured in fga−/− fish (Figure 3B), as we previously described in a similar fga mutant.21 Expression of fibrinogen Aα did not affect TTO in fga+/+ or fga+/− larvae significantly, compared with noninjected larvae, and only rescued venous occlusion in a single fga−/− animal (n = 9). However, expression of fibrinogen AαE cDNA shortened the laser-induced TTO in all but 1 of the fga+/+ (n = 29), fga+/− (n = 44), or fga−/− (n = 12) larvae (Figure 3B), with TTO values reminiscent of the TU strain (Figure 1A).

Reversal of a venous thrombosis defect and afibrinogenemia with fibrinogen AαE, but not Aα, expression in early zebrafish larvae. (A) One- to 2-cell embryos from an fga+/− in cross mating were microinjected with reagents for transgenic expression of fibrinogen Aα or AαE cDNAs under the control of a ubb (ubi P) promoter sequence. At 3 dpf, TTO was measured after laser injury of the PCV as illustrated. (B) Results are shown with the fga genotype, number of larvae used in brackets, and, where appropriate, cDNA expressed on the y-axis. Each shape represents an individual larva. Mann-Whitney U tests were made to test for statistical significance of differences between groups (****P < .0001).

Reversal of a venous thrombosis defect and afibrinogenemia with fibrinogen AαE, but not Aα, expression in early zebrafish larvae. (A) One- to 2-cell embryos from an fga+/− in cross mating were microinjected with reagents for transgenic expression of fibrinogen Aα or AαE cDNAs under the control of a ubb (ubi P) promoter sequence. At 3 dpf, TTO was measured after laser injury of the PCV as illustrated. (B) Results are shown with the fga genotype, number of larvae used in brackets, and, where appropriate, cDNA expressed on the y-axis. Each shape represents an individual larva. Mann-Whitney U tests were made to test for statistical significance of differences between groups (****P < .0001).

AαE fibrinogen facilitates erythrocyte-rich thrombosis

In 3-dpf zebrafish larvae, thrombocytes begin to circulate,43 but erythrocytes are the major cellular component in laser-induced thrombi (see bright field TTO image in Figure 3A). To assess the role of AαE vs Aα fibrinogen chains in this context, we used an antisense morpholino oligonucleotide (MO) to lower fibrinogen expression by targeting splicing of the fga mRNA in a transgenic zebrafish line with red fluorescent erythrocytes [Tg(gata1:DsRed)]. In 2 control experiments using the TU strain, we injected early embryos with 2 ng of fga MO or 2 ng of a control MO, and measured fibrinogen mRNA by reverse transcription qPCR in pools of larvae at 3 dpf. Mean fga mRNA levels, normalized to 100% in noninjected embryos, were 110% in control MO-injected larvae and 7% with the fga MO. The fga MO was coinjected with or without transgenesis reagents for expression of fibrinogen Aα chains or AαEs in hemizygous Tg(gata1:DsRed) embryos from a transgenic parent mated with the TU strain (Figure 4A). The fga MO lowers endogenous Aα or AαE fibrinogen expression but should not prevent expression of cDNA-derived fibrinogen α-chain mRNA, as it targets unspliced fga mRNA. With low fibrinogen α-chain expression, the fga MO knockdown prevented venous occlusion in the TTO assay (Figure 4B). Expression of the Aα chain rescued occlusion in 17 of 23 larvae with a prolonged TTO compared with noninjected animals (mean TTO, 18 seconds for noninjected, 58 seconds for occluding fga MO plus Aα). Expression of the AαE rescued occlusion in all fga MO plus AαE larvae, with an average TTO that was similar to noninjected fish (mean TTO, 21.9 seconds; n = 24). The more effective rescue of erythrocyte-rich clotting with AαE vs Aα-chain expression, could also be seen when quantifying the accumulation of red fluorescence after the laser injury (Figure 4C). The fluorescence measured 20 seconds postlaser for each larva is plotted in Figure 4D with the group mean and standard deviation indicated. P values for unpaired Student t tests between certain groups are indicated and listed in supplemental Tables 1-3 for data at 16, 20, and 24 seconds postlaser, respectively. Twenty-four seconds after laser injury, a time point at which occlusive thrombosis was indistinguishable in noninjected and fga MO plus AαE–injected larvae, mean fluorescence had not increased at the injury site after fga MO-mediated knockdown and barely changed in fga MO plus Aα–injected animals.

Venous thrombosis with fibrinogen AαE or Aα expression in MO-induced fibrinogen knockdowns, monitored in early zebrafish larvae with fluorescent erythrocytes. (A) One- to 2-cell embryos from a Tg(gata1:DsRed) × TU mating were microinjected with an MO that inhibits fga mRNA by antisense targeting of the exon 1–intron 1 splicing boundary, lowering by over 90% the expression of fibrinogen Aα or AαE. This was done in the presence or absence of Aα-chain or AαE cDNA expression, which cannot be targeted by the MO, and the TTO assessed at 3 dpf after laser injury in the PCV. Measurements were made by monitoring the red fluorescent erythrocytes in these larvae, a single frame image of which is given to the right. The dorsal aorta (DA), PCV, and laser-injury (LI) position are labeled. Scale bar, 50 μm. (B) The TTO results for the respective conditions with the number of embryos assessed below each in brackets, and P values of a Mann-Whitney U test between certain groups. Each circle represents an individual larva. (C) The gata1:DsRed-associated fluorescence accumulation in the first 24 seconds postlaser injury are plotted, for each group of larvae from within a defined region around the laser-injury site. Average fluorescence over time is plotted with error bars representing the standard error of the mean for each grouping. The number of larvae per group is shown in brackets next to the group color indicators. (D) The data for individual larvae 20 seconds postlaser are plotted for each group, with the mean and standard deviation. P values are indicated for unpaired Student t tests; results of further tests at 16, 20, and 24 seconds postlaser are given in supplemental Tables 1-3.

Venous thrombosis with fibrinogen AαE or Aα expression in MO-induced fibrinogen knockdowns, monitored in early zebrafish larvae with fluorescent erythrocytes. (A) One- to 2-cell embryos from a Tg(gata1:DsRed) × TU mating were microinjected with an MO that inhibits fga mRNA by antisense targeting of the exon 1–intron 1 splicing boundary, lowering by over 90% the expression of fibrinogen Aα or AαE. This was done in the presence or absence of Aα-chain or AαE cDNA expression, which cannot be targeted by the MO, and the TTO assessed at 3 dpf after laser injury in the PCV. Measurements were made by monitoring the red fluorescent erythrocytes in these larvae, a single frame image of which is given to the right. The dorsal aorta (DA), PCV, and laser-injury (LI) position are labeled. Scale bar, 50 μm. (B) The TTO results for the respective conditions with the number of embryos assessed below each in brackets, and P values of a Mann-Whitney U test between certain groups. Each circle represents an individual larva. (C) The gata1:DsRed-associated fluorescence accumulation in the first 24 seconds postlaser injury are plotted, for each group of larvae from within a defined region around the laser-injury site. Average fluorescence over time is plotted with error bars representing the standard error of the mean for each grouping. The number of larvae per group is shown in brackets next to the group color indicators. (D) The data for individual larvae 20 seconds postlaser are plotted for each group, with the mean and standard deviation. P values are indicated for unpaired Student t tests; results of further tests at 16, 20, and 24 seconds postlaser are given in supplemental Tables 1-3.

To approximate fibrinogen protein levels in the larvae in these analyses, and control for possible differences in expression levels between transgenically expressed Aα chains and AαEs (used for data in Figures 3 and 4), we made immunoblots for fibrinogen larval lysates 3 days postinjection. Compared with noninjected larvae, fibrinogen was scarcely detectable after MO injection, but immunoreactive bands of similar molecular weight and intensity to those in noninjected larval lysates were seen after injection of fga MO plus Aα or fga MO plus AαE (supplemental Figure 3).

We conclude that the genetic modifier of venous thrombosis detected is a single-nucleotide deletion in exon 6 of fga that prevents the production of fibrinogen with the AαE isoform. This leads to variable, prolonged larval thrombotic responses that can be effectively shortened by expression of fibrinogen AαE, but not Aα, even when Aα is expressed at levels resembling the AαE-containing fibrinogen in larvae lacking the deletion.

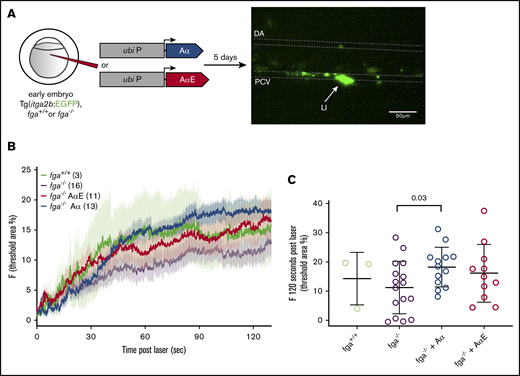

Fibrinogen with Aα or AαE can mediate thrombocyte adhesion and aggregation

In 5-dpf zebrafish larvae, thrombocytes circulate and participate in clotting in response to laser injury. We were interested to know whether the differences in the ability of fibrinogen Aα chains and AαEs to rescue the depletion or absence of fibrinogen in our TTO assay at 3 dpf were similar at 5 dpf in the presence of thrombocytes. Laser injuries were made to the PCV in 5-dpf Tg(itga2b:EGFP) larvae, which have green fluorescent thrombocytes to facilitate their monitoring (Figure 5A). This was in the presence or absence of fibrinogen (fga+/+ or fga−/−) and with transgenic expression of Aα or AαE in fga−/− fish. This assay does not typically lead to occlusive thrombi, which helps in monitoring thrombocyte interactions at the injured vessel wall over time. Adhesion and aggregation of GFP+ thrombocytes postinjury was monitored for 2 minutes by fluorescence microscopy (Figure 5B). Fluorescence at the injury site 120 seconds postlaser for individual larvae in groups is shown in Figure 5C. P values for unpaired Student t tests between groups are listed in supplemental Tables 4-6 for data at 60, 90, and 120 seconds postlaser, respectively.

Effect of fibrinogen Aα or AαE expression on laser-induced thrombocyte binding and aggregation in 5-dpf zebrafish larvae. (A) One- to 2-cell zebrafish embryos with the fga+/+ or fga−/− genotype, hemizygous for the itga2b:EGFP transgene, were microinjected for expression of fibrinogen Aα or AαE cDNA. At 5 dpf, laser injuries were made in the PCV and green fluorescent thrombocytes accumulating within a defined area measured over time, which is shown schematically. The dorsal aorta (DA), PCV, and laser-injury (LI) position are labeled. Scale bar, 50 μm. (B) The mean fluorescence for each experimental group is plotted as a line against time, with error bars representing the standard error of the mean for each group; the number of larvae per group is denoted in the figure. Given the broad variability in this assay, we compared the accumulated fluorescence of each group at 60, 90, and 120 seconds after laser injury. (C) The results at 120 seconds postlaser are given with individual larvae shown and the mean and standard deviation. Means for each group were compared using unpaired Student t tests; the results are given in supplemental Tables 4-6.

Effect of fibrinogen Aα or AαE expression on laser-induced thrombocyte binding and aggregation in 5-dpf zebrafish larvae. (A) One- to 2-cell zebrafish embryos with the fga+/+ or fga−/− genotype, hemizygous for the itga2b:EGFP transgene, were microinjected for expression of fibrinogen Aα or AαE cDNA. At 5 dpf, laser injuries were made in the PCV and green fluorescent thrombocytes accumulating within a defined area measured over time, which is shown schematically. The dorsal aorta (DA), PCV, and laser-injury (LI) position are labeled. Scale bar, 50 μm. (B) The mean fluorescence for each experimental group is plotted as a line against time, with error bars representing the standard error of the mean for each group; the number of larvae per group is denoted in the figure. Given the broad variability in this assay, we compared the accumulated fluorescence of each group at 60, 90, and 120 seconds after laser injury. (C) The results at 120 seconds postlaser are given with individual larvae shown and the mean and standard deviation. Means for each group were compared using unpaired Student t tests; the results are given in supplemental Tables 4-6.

We controlled for effects of the fga genotype on circulating thrombocyte numbers by counting the GFP+ cells passing through the PCV in noninjected fga+/+, fga+/−, and fga−/− fish with the itga2b:EGFP transgene. No significant differences were measured (supplemental Figure 4).

The absence of fibrinogen (fga−/−) appeared to lower laser-induced thrombocyte accumulation, compared with wild-type larvae (fga+/+), but did not inhibit initial thrombocyte binding to the injury site or a gradual increase in fluorescence over time, and did not reach statistical significance. Aα or AαE expression in fga−/− increased thrombocyte accumulation compared with noninjected fga−/− (Figure 5B), but only expression of Aα gave a significant increase (Figure 5C; supplemental Tables 4-6) and a significant difference was not measured between fga−/− plus Aα and fga−/− plus AαE. These data show variability within experimental groups, but in contrast to developmentally earlier occlusive thrombi, thrombocyte accumulation after injury does not appear to show a clear dependency on 1 fibrinogen α-chain isoform.

Discussion

In this report, we demonstrate the molecular basis of a genetic modifier of venous thrombosis in larval zebrafish, which in turn assigns a functional role for fibrinogen with the AαE isoform, with αEC domains, in the blood clotting step of early hemostasis.

Our study is an example of how disparity between genetic backgrounds can reveal an unambiguous modifying effect on a defined physiological process. Laboratory zebrafish strains are generally not as well defined genetically as other model systems.44 Although this can introduce variability, in this case it helped reveal the basis of differences in experimental venous thrombosis between strains. This reinforces the importance of the underlying genetic background in zebrafish, as we have recently shown,45 as well as for other model organisms, as seen with Gray platelet syndrome in mice.46 Our initial results could have been ignored as technical noise, but instead highlight the power of the larval zebrafish model system and the utility of the laser-induced TTO assay for detecting genotype-phenotype correlations.

The αEC domain of fibrinogen AαE is conserved across vertebrates,6 suggesting functional importance. It resembles the C-terminal globular domains of the fibrinogen Bβ and γ chains, in agreement with their common ancestry,47,48 but lacks the equivalent residues found in γC and βC involved in fibrin polymerization.9 The early blood clotting we have studied in zebrafish larvae indicates that AαE is a more effective α-chain for promoting a coagulation response and thrombosis. This infers that the AαE chain is better adapted for fibrin formation during early development compared with Aα, perhaps due to the presence or absence of factor(s) in the embryonic coagulation process or the changing nature of circulating cells. A fibrinogen concentrate rich in fibrinogen 420 may have advantageous clotting properties compared with current fibrinogen-based therapies, with altered fibrin formation kinetics or cellular interactions. Further mechanistic studies are warranted to investigate this.

We cannot exclude that our observations are limited to the role of the fibrinogen AαE chain, with its αEC domain, in developing zebrafish or closely related species. A similar embryonic role in humans may not exist. In vitro assays of clot formation using thrombin did not demonstrate major differences between human fibrinogen containing Aα chains or AαEs in a purified system.10 Our findings do not correlate with this, but a direct comparison is problematic because we measured differences in larval blood clotting with Aα and AαE when the contribution of plasma proteins, the endothelium, and circulating cells is expected to influence the outcome. Additionally, as mentioned in "Laboratory zebrafish strains reveal a genetic modifier of venous thrombosis," we cannot measure the fibrinogen levels in the larval circulation at present. Although this can be inferred by expression studies, the influence of small differences in plasma fibrinogen levels has not been excluded here. Comparing the clotting properties of purified zebrafish and human fibrinogen, containing their respective Aα chains or AαEs, would help resolve these issues.

Binding of fibrinogen 420 to leukocyte β2-type integrins (αMβ2, αXβ2) has been reported,11 but its importance in vivo is unclear. Our data support the hypothesis that fibrinogen with AαE, rather than Aα, is involved in clotting when erythrocytes are the principle cellular component, in the near absence of circulating thrombocytes. This could implicate the fibrinogen αEC domain of AαE in erythrocyte binding or retention. However, rather than β2-type integrins, the receptors showing experimental evidence of fibrinogen binding on mammalian red blood cells are the αVβ3 integrin49 and CD47.50 For erythrocyte retention in venous clots, where factor XIII activity is important,51 it seems unlikely that AαE would be critical because of its low abundance. Although α-chain cross-linking is important,52 factor XIII–mediated erythrocyte retention can be reconstituted with recombinant fibrinogen that presumably lacks AαE.52

The AB strain larvae with the fga exon 6 mutation we describe show variable hemostatic responses and could have low fibrinogen levels. The presence of fibrinogen Aα enabled vascular occlusion after injury in some AB larvae, with an extended average TTO compared with the TU strain. Additional transgenic production of Aα had little effect on the variable AB TTO whereas AαE expression gave TTOs resembling the TU strain. The inability of the fibrinogen Aα chain to rescue the impaired thrombotic response seen with fibrinogen deficiency in fga−/− mutants was unexpected. In humans, the Aα chain is part of “normal” fibrinogen, but in the early life of the zebrafish, our data point to the AαE-containing fibrinogen as the predominant form. As previously stated, this finding may have limited translation in the human setting.

Whether polymorphisms or mutations in FGA exon 6 are linked to human pathology is unclear. Three FGA exon 6 variants have been identified in patients with fibrinogen deficiencies,53-55 but causality has not been proven. As fibrinogen 420 is only present as 1% of circulating adult fibrinogen, and only 3% in newborns,7 we conclude that variation in the αEC domain of AαE is unlikely to lead to a quantitative human fibrinogen disorder.56 However, if fibrinogen 420 is necessary for leukocyte interactions, its absence or mutation could have significant clinical consequences.

When a morpholino was used to lower Aα or AαE expression (>90%) in embryos from a cross between transgenic adults and the TU strain, which can produce AαE, Aα cDNA expression rescued laser-induced TTO more effectively than in the AB strain (compare Figure 3B with Figure 4B or supplemental Figure 2). We believe this could be due to residual endogenous AαE expression in these larvae, absent in AB larvae described in Figure 3B.

In summary, we have demonstrated a genetic modifier of venous thrombosis in the zebrafish that resides in exon 6 of fga and impedes fibrinogen AαE expression. The differential ability of Aα chains and AαEs to complement fibrinogen deficiency in zebrafish larvae supports a role for the αEC domain of AαE in early blood coagulation, and the presence of AαEs or Aα chains may be linked to fibrin formation in the context of different cells or factors available for clotting. The zebrafish model is ideally suited for further investigation of these issues given the accessibility of larvae for studies of early development.

Genome sequencing data are available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information repository, BioProject number PRJNA597072.

For original data, please contact Marguerite Neerman-Arbez at marguerite.neerman-arbez@unige.ch.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation funding (#31003A_152633) (M.N.-A.); National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants R01 HL124232, R01 HL125774, and R35 HL150784 (J.A.S.); and National Institutes of Health grants T32 GM007863 (National Institute of General Medical Sciences) and T32 HL125242 (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute), and an American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship Award (S.J.G.).

Authorship

Contribution: C.F., R.V., C.D.S., S.J.G., and C.E.R. performed experiments and analyzed and interpreted data; R.J.F. designed and performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and drafted the manuscript; J.A.S. and M.N.-A. directed research and contributed to writing; and all authors approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Marguerite Neerman-Arbez, Department of Genetic Medicine and Development, University of Geneva Medical Centre, 1, Rue Michel-Servet, 1211 Geneva 4, Switzerland; e-mail: marguerite.neerman-arbez@unige.ch.

References

Author notes

C.F. and R.J.F. contributed equally to this work.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.