Key Points

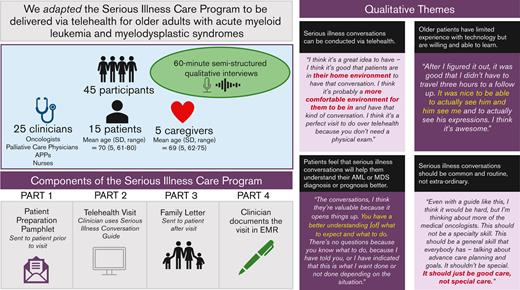

We adapted an SICP to be delivered via telehealth for older adults with hematologic malignancies.

The adapted SICP may facilitate earlier advance care planning discussions.

Abstract

Older patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) experience intense inpatient health care at the end-of-life stage. Early advance care planning may improve care at the end of life for patients with AML or MDS. The Serious Illness Care Program (SICP) is a multicomponent, communication intervention developed to improve conversations about values for patients with serious illnesses. The SICP has been shown to improve the quality and frequency of advance care planning discussions. We adapted the SICP for delivery via telehealth to older patients with AML or MDS. We conducted a single-center qualitative study of 45 participants (25 clinicians, 15 older patients with AML or MDS, and 5 caregivers). Participants, whether clinicians, patients, or caregivers, agreed that the SICP would help older patients with AML or MDS to share their personal values with their care team. Four qualitative themes emerged from our data: (1) serious illness conversations can be conducted via telehealth, (2) older patients have limited experience using technology but are willing and able to learn, (3) patients feel that serious illness conversations will help them understand their AML or MDS diagnosis and prognosis better, and (4) serious illness conversations should be common and routine, not extraordinary. The adapted SICP may provide older patients with AML or MDS an opportunity to share what matters most to them with their care team and may assist oncologists in aligning patient care with patient values. The adapted SICP is the subject of an ongoing single-arm pilot study at the Wilmot Cancer Institute (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT04745676).

Introduction

Patients with hematologic malignancies, such as acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), use more high-intensity care (eg, hospitalizations, intensive care unit admissions) at the end of life (EOL) than patients with solid tumors.1-3 Adults aged ≥60 years have lower survival rates than younger patients and are at risk for more rapid clinical declines.4 High inpatient health care use and in-hospital deaths are considered suboptimal at the EOL based on established quality of care metrics.5 Nevertheless, a retrospective study of 46 older patients with AML found that 51.2% spent the final month of their life in the hospital.6 Another study demonstrated that only 44.4% of older adults with AML enrolled in hospice at the EOL.7 Among patients enrolled in hospice, 47% and 28% enrolled in the last 7 days and 3 days of life, respectively.7

Advance care planning (ACP) is a process that supports patients in sharing their personal values regarding medical treatment.8 This process may include completion of advance directive forms (ie, medical order for life-sustaining treatment form, health care proxy, or living will), but more importantly, exploration of the patient’s values.9 Serious illness communication is a process that seeks to improve conversations about values and may include advance directive completion.10 Therefore, although the terminology is distinct, both processes have a similar intent, to identify patient values so that care aligns with what matters most to the patient.

The Serious Illness Care Program (SICP) is a multicomponent communication intervention developed to improve conversations about values for patients with serious illnesses.11 A cluster randomized clinical trial of the SICP in the outpatient setting for 278 patients with cancer found that patients who were randomized to the intervention arm experienced significant reductions in anxiety (5.0% vs 10.2%, P = .05) and depression (10.6% vs 20.8%, P = .04).12 Serious illness conversations (SICs) occurred more frequently with patients in the intervention arm compared with usual care (96% vs 79%, P = .005), and conversations took place 2.4 months earlier (P < .001). However, <10% of patients in the aforementioned study had a hematologic malignancy.12 The acuity and uncertainty associated with diagnoses of AML or MDS lead to unique challenges that can be addressed via processes such as ACP.13,14 In addition, compared with younger adults, older adults with AML or MDS are more likely to have aging-related vulnerabilities (eg, functional and cognitive impairments) that are associated with poorer outcomes.4,15-17 Therefore, we hypothesize that elicitation of patients’ preferences, worries, and preferred involvement in care early in their disease trajectory may ensure goal-concordant care for older patients with AML or MDS.

With the emergence of COVID-19, the use of telehealth visits increased.18 Use of telehealth interactions for patients with cancer is feasible and improves quality of life.19,20 Telehealth increases access to cancer specialists for patients residing in rural areas and allows support persons who may not live close to the patient to participate in health care visits.21 Telehealth potentially provides increased opportunities for SICs for older patients with AML or MDS, as well as involvement of caregivers, although its acceptability, efficacy, and overall effectiveness remain to be evaluated.

The primary aim of this qualitative study was to evaluate and adapt the SICP for delivery via telehealth to older patients with AML or MDS. The secondary aim was to explore clinician, patient, and caregiver perspectives on having SICs (including via telehealth) for older patients with AML or MDS.

Methods

Study design, population, and setting

We conducted a single-center qualitative study designed to assess and adapt the SICP for delivery via telehealth to older patients with AML or MDS.22 Participants were recruited from the Wilmot Cancer Institute (Rochester, NY) and its affiliated sites. Oncology clinicians, palliative care clinicians, patients with AML or MDS, and caregivers (if available) for patients with AML or MDS were recruited. The inclusion criteria for oncology and palliative care clinicians were physicians, nurses, or advance practitioners who cared for at least 1 patient aged ≥60 years with AML or MDS during the past year. The inclusion criteria for patients were being ≥60 years old with a diagnosis of AML or MDS, English-speaking, and able to provide informed consent. Caregivers were selected by the patient when asked if there is a family member, partner, friend, or caregiver (aged ≥21 years] with whom you discuss, or who can be helpful in, health-related matters, and spoke English. English-speaking was part of our inclusion criteria because the SICP documents are written in English. The institutional review board of the University of Rochester Medical Center provided approval for this study.

Study procedure and data collection

Data was reported using the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research guidelines (supplemental Table 1). Participants who consented to the study completed baseline measures and were provided with the SICP documents to review before their interview. They participated in 60-minute semistructured interviews focused on telehealth and feedback on the SICP (supplemental Table 2).

Data analyses

Demographics (of all participants) and clinical characteristics (of patients) were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Transcripts from the professional transcription service were analyzed using focused content analysis and open coding on MAXQDA (VERBI Software GmbH, Berlin, Germany). A preliminary coding schema was developed based on the first 2 transcripts and was modified based on subsequent analysis. Thematic saturation was achieved for patients and clinicians. We included caregivers if they were available to provide additional perspectives but did not aim to achieve thematic saturation in this group.

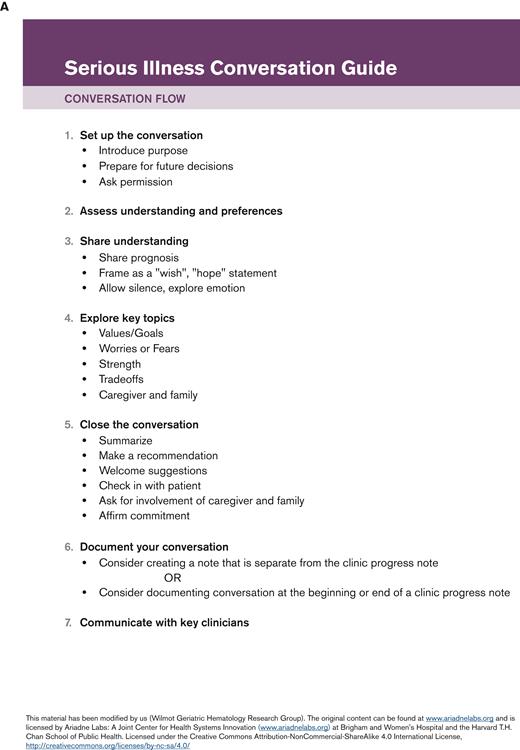

The SICP

The SICP is a multicomponent communication intervention developed to improve conversations about values for patients with serious illnesses.11 It is designed to (1) identify patients at high risk of death in the next year, (2) train clinicians to use the Serious Illness Conversation Guide (SICG) to structure ACP discussions with patients, (3) prompt oncology clinicians to have conversations using the guide with enrolled patients, (4) prepare patients for the conversation by providing them with a letter, the patient preparation letter, encouraging them to think about some of the topics raised in the SICG, (5) guide clinicians in conducting values and goals conversations, (6) document outcomes of the discussion in a structured format in the electronic medical record (EMR), and (7) provide patients with a family communication guide to help them continue discussions at home with their loved ones.11,12

Other components of the intervention include an interactive training session on the SICG for oncology clinicians delivered by palliative care experts, system changes for routine identification of patients at high risk of death, email reminders to clinicians to initiate conversations with patients, and a template in the EMR for documentation.11

Results

Of the 24 patients who were approached, 20 consented to this study (consent rate: 83%); 5 patients withdrew from the study after giving consent and therefore did not participate in the 60-minute semistructured interview. Of the 5 patients that withdrew, 2 patients had declining health status, 2 patients no longer wanted to participate at time of interview, and 1 patient was unable to be reached via phone after providing consent. We enrolled patients until thematic saturation was met. Six caregivers were approached, and 5 consented (consent rate: 83%). All 5 caregivers completed study procedures. Twenty-eight clinicians were approached, and 25 consented (consent rate: 89%). All 25 clinicians completed study procedures. The final sample size was 45 participants, and the study population comprised 15 patients, 5 caregivers, and 25 clinicians.

Demographics

Among the 45 participants, 16 were oncology clinicians, 9 were palliative care clinicians, 15 were patients with AML or MDS, and 5 were caregivers. Mean ages of oncology clinicians, palliative care clinicians, patients, and caregivers were 46, 49, 70, and 69 years, respectively. Demographic information for participants is shown in Tables 1 and 2. Clinical characteristics of patients are shown in Table 2. Patient and caregiver participants in this study had high health literacy with an average score of 5.7 (standard deviation, 0.6) and 6.0 (standard deviation, 0.0), respectively.

SICP adaptation

We adapted the SICP documents to meet the unique needs of older patients with AML or MDS. In general, participants in this study reported that they liked the SICP and that it would be helpful for patients with AML or MDS to share their values with their care team. Specifically, 10 patients (67%) stated that they think that the SICP is a good idea and would be helpful, 2 patients (13%) stated that the SICP resembled discussions that they have already had, 2 (13%) patients said the SICP would be best if personalized to each patient, and 1 patient (7%) was not sure if the SICP would be helpful to them. Clinicians in this study reported that they would like an EMR documentation template and would be willing to participate in a training session to learn how to use the adapted SICP in clinical practice.

A study participant said: “I’m just happy you’re doing what you’re doing…I applaud you because in other cases that I’ve been with people, I haven’t seen this aspect of treatment offered…I think you’re spot on to be doing this study and to be offering people the opportunity to not wait until you’re told you got 3 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months to live.”

Adaptation of patient preparation letter

Oncology clinicians suggested providing the patient with more examples of questions that they might ask at their SIC visit. They also suggested removing the language of “stable disease,” because AML or MDS are often unstable with a substantial risk of rapid decline in older patients. Patients thought that the wording of this guide was appropriate, but the visual layout of the paragraphs was overwhelming to look at. Patients suggested that a pamphlet-style patient preparation letter would look better. Table 3 shows changes made to the patient preparation letter. Figure 1A and B show the original and adapted patient preparation letters, respectively.

Adapted patient preparation letter. (A) Page 1. (B) Page 2.

SICG adaptation

Oncology clinicians suggested that the language of the SICG be simplified. They offered suggestions for wording that would better gauge the patients’ understanding of their diagnosis. Oncology clinicians also recommended changing the wording of the subcategories under the “share” section, removing the terms “wish” and “worried” from the language of the guide and focusing on what is likely for patients rather than what is ahead. Patients agreed with oncology clinicians that the word “worried” should be removed from the SICG. Patients advised against using the word “goal,” because the meaning behind a goal is defined differently by all individuals (ie, some may define functionality as a goal whereas others may have the goal to live until a particular event). Patients suggested that clinicians be honest in sharing prognostic information with patients. Table 4 shows the changes made to the SICG. Figure 2A and B show the original and adapted SICG, respectively.

Family letter adaptation

Oncology clinicians liked the family guide and shared that they believe it would have a positive impact on patients’ ability to communicate with their loved ones. Patients agreed and some patients stated that the family guide reflected their own personal conversations with their family. No changes were made to the family guide.

Qualitative feedback

Four major qualitative themes were identified in this study: (1) SICs can be conducted via telehealth, (2) older patients have limited experience using technology but are willing and able to learn, (3) patients feel that SIC will help them understand their AML or MDS diagnosis and prognosis better, and (4) SICs should be common and routine, not extraordinary. Representative quotes are shown in Table 5.

SICs can be conducted via telehealth

Telehealth may increase patient comfort

Oncology clinicians felt that having SICs via telehealth might provide patients with the comfort of being at home, in an environment familiar to them. In addition, telehealth conversations would allow patients to have more family members present for support during a SIC.

Palliative care clinicians reported that telehealth SICs could be particularly helpful for weaker and more symptomatic patients.

Patients echoed the oncology and palliative care clinicians’ sentiment regarding telehealth-based SICs. Some patients explained that the telehealth option eased their worries regarding going out in public with a leukemia diagnosis.

Telehealth may make interpretation of body language challenging

Although participants in the study were optimistic about telehealth, they identified challenges to having SICs via this platform. Oncology clinicians found it challenging to see the entire person while using telehealth, and therefore it may be more difficult to respond to patients’ unspoken emotions and/or body language. Oncology clinicians emphasized that telehealth with video, as opposed to just phone audio, helps combat this challenge.

Palliative care clinicians also found body language was more difficult to interpret via telehealth. They were also worried about navigating and balancing the opinions of multiple loved ones who might be participating in a telehealth visit.

Patients were also worried about interpreting body language and recalled previous telehealth experiences in which people interrupted or spoke over each other when communicating. Some patients were concerned that they might misinterpret the body language of their clinician if they looked away from the camera and/or seemed preoccupied by something other than the conversation.

Older patients have limited experience with technology but are willing and able to learn

Patients’ current experience with technology is limited

Oncology clinicians emphasized that their older patients with AML or MDS were often not familiar with using technology and might find telehealth to be logistically challenging.

Palliative care physicians also thought that older patients, specifically, may have more difficulty troubleshooting technological difficulties during a telehealth visit. Furthermore, they were concerned that older patients, who are more likely to have hearing impairments, may have difficulty understanding the clinician’s voice via telehealth, especially when video is lacking.

Patients are willing to learn how to use telehealth

The patients in our study had limited experience with using telehealth, and many reported infrequent computer use. Some patients had used telehealth to meet with their primary care physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic for routine follow-up appointments. Patients were concerned that they would not be able to figure out how to access a camera for a telehealth visit. Nevertheless, patients in this study generally were willing to participate in a telehealth ACP visit and believed that they would be able to use telehealth successfully after learning how to use the technology. Specifically, 12 of 15 patients (80%) reported that they would be willing to participate in a telehealth ACP visit; 2 of 12 patients (13%) stated that they would prefer an in-person visit and 1 patient (7%) stated that they would participate in telehealth depending on their health status at the time of visit.

Patients feel that SICs will help them understand their AML or MDS diagnosis and prognosis better

Patients should be prepared to have an SIC

Oncology clinicians highlighted the importance of preparing their patients for an SIC. They suggested that providing the patient preparation letter from the SICP before the SIC visit was ideal, to allow the patient to adequately prepare to discuss their preferences and values.

Patients echoed the oncologists and stressed that it was important for them to have time to prepare for their SIC. Many patients said the patient preparation letter in the SICP would be helpful to them.

Patients emphasized their desire to understand their diagnosis (including course of illness and prognosis) of AML or MDS and felt that a SIC would be beneficial to their care.

Patients reported that additional education on their diagnosis and prognosis would be helpful but did not want to be scared by their clinician. Many patients recalled feeling confused when they received their diagnosis. They would have liked a SIC to better understand their diagnosis but recommended that the conversation be adaptable to each individual patient’s needs.

Positivity is important when communicating with patients about their illness

Oncology clinicians highlighted the challenge that they face when communicating information to patients about diagnosis and prognosis while simultaneously trying not to take away hope. Clinicians did not want their relationship with patients to be negatively affected by the SIC and wanted to continue to be someone that the patient looked forward to seeing. They added that this situation is particularly difficult to navigate in the setting of AML and MDS, in which the diagnoses are often very unpredictable, and older patients, in particular, are at high risk of rapid decline.

Patients identified hope and positivity as their driving force to navigate a new and unfamiliar diagnosis. They stressed the importance of being educated early about their prognosis without completely taking away the hope that helped them to move forward.

SICs should be common and routine, not extraordinary

All clinicians should be comfortable having SICs with patients

Palliative care clinicians reported that they receive consults to have SICs with patients. Although these conversations are frequently conducted by palliative care clinicians, it is important that all medical specialties be trained to have SICs with patients. They believed that SICs should be a routine part of hospital care, in which clinicians of various medical specialties should be trained to conduct, especially in the field of oncology because prognosis is typically poor for these patients.

Palliative care clinicians suggested that routine elicitation of patient values (in all medical settings) will make SICs less daunting for all patients, not just for those with a hematologic malignancy such as AML or MDS.

Patients want their oncologist to lead their serious illness discussion

Patients stated that they wanted their oncology clinicians to be trained to have SICs with them. They believed that these discussions would be best led by their primary treating oncologist who could speak about their disease status/prognosis, treatment options and side effects, and personal priorities/family values. Specifically, 11 of 15 patients (73%) stated that they would like their oncologist to be at their ACP visits; 3 patients (20%) did not specify whether they would prefer their oncologist at their ACP visit, and 1 patient (7%) specified that they would want to have an ACP conversation with their family, as opposed to a physician.

Discussion

We evaluated and adapted the SICP for delivery via telehealth to older patients with AML and MDS. Four major qualitative themes emerged from our data: (1) SICs can be conducted via telehealth, (2) older patients have limited experience using technology but are willing and able to learn, (3) patients feel that SICs will help them understand their AML or MDS diagnosis and prognosis better, and (4) SICs should be common and routine, not extraordinary.

We found that telehealth-based SICs may provide patients with the comfort of a familiar environment but run the risk of making interpretation of body language a challenge. Oncology clinicians in a previous study noted the convenience and increased access to care provided by telehealth but were similarly concerned with the ability to comfort patients in a virtual setting.23 Patients with cancer also appreciated the convenience of telehealth; some reported that they preferred to receive serious or bad news virtually.24 These patients felt that telehealth allowed more privacy, more space to process serious news, and additional family comfort (which is not available in an in-person setting).24 Although interpretation of body language remains a challenge with telehealth, having SICs via telehealth might also provide patients with a safe space to process their emotions with a larger support system. Nonetheless, clinicians should elicit patient preferences for having ACP discussions via telehealth vs in-person. Although the majority of patients in this study would be willing to have an ACP discussion virtually, this may not be the case for all individuals.

Oncology clinicians, palliative care clinicians, and patients in our study were concerned about the logistics of delivering care for older patients via telehealth. Technological issues, including poor Internet connection and lack of universal access to technology, are commonly reported as a barrier to telehealth.25 Nonetheless, patients in our study would be willing to use telehealth for a SIC, increasing the likelihood of successful use. Telehealth has provided benefits to older patients during COVID-19, including increased timeliness of care, enhanced communication with caregivers, and reduced travel burden.26 Previous research identified predictors for older adults’ success with telemedicine, some of which include perceived usefulness, effort expectancy, and physicians’ opinion.27 By delivering our adapted SICP via telehealth, we may increase access and frequency of SICs for older adults with hematologic malignancy.

Patients in this study emphasized their desire to fully understand their AML or MDS diagnosis and prognosis, and identified SICs led by their oncologist as a mechanism to help accomplish this. Patients stressed that these conversations would be most effective if discussed with hope and positivity even in the context of poor prognosis. This could be done by emphasizing what can be done, exploring realistic goals, and discussing day-to-day living.28 Research focusing on communicating prognosis to patients with cancer found that patients prefer a honest and clear presentation of prognosis and prefer clinicians to encourage hope and a sense of control in the conversation.29 A previous study demonstrated that the receipt of adequate diagnostic and prognostic information facilitated better patient-clinician relationships in 84% of patients.30 Prognostic discussions are not harmful to the patient-physician relationship and may actually strengthen the therapeutic alliance between a patient and their clinician.31 Older patients with AML or MDS want to have SICs with their oncologists, and this may lead to better patient understanding of diagnoses and patient-care team relationships. Therefore, our findings support the need for the development of palliative care interventions to be delivered by the oncology team for patients with hematologic malignancies.

SICs should take place in all medical specialties, especially oncology. Palliative care clinicians in this study suggested routine conversations for patients with hematologic malignancy. Since the original SICP randomized controlled trial, studies have implemented the SICP in clinical practice.32 In an outpatient oncology clinic at the Tom Baker Cancer Centre in Canada, implementation led to increased documentation of SICs at postintervention and documentation of 93% of conversations in the electronic medical record.32,33 At the Abramson Cancer Center in Pennsylvania, the majority of patients (90%) reported that the SIC was worthwhile, with 55% reporting that the conversation increased their understanding of their future health, 42% reporting increased sense of control over future medical decisions, 58% reporting increased closeness with their physician, and 42% reporting greater hopefulness about quality of life.32,34 Routine implementation of the SICP for older patients with AML or MDS may lead to increased SIC documentation, improvement in patient knowledge, and may promote patient hope and positivity. A single-arm pilot study is currently ongoing to evaluate the feasibility of the SICP for older patients with AML or MDS (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT04745676).

Our study has strengths. Firstly, we included perspectives from a variety of stakeholders including older patients with AML or MDS, their caregivers, oncology clinicians, and palliative care clinicians. Secondly, we adapted the SICP for the vulnerable population of older patients with AML or MDS. In addition, this patient population is underrepresented in clinical trials. Our study has limitations. Firstly, as a single-center qualitative study at a large academic center, our results may not be widely generalizable. Secondly, our patient/caregiver population comprised largely White and non-Hispanic patients with high health literacy and may not be generalizable to minority populations. Additional studies testing these materials in a diverse population is warranted. Thirdly, because caregiver enrollment was based on availability, thematic saturation for the caregiver group was not reached. Nonetheless, it is valuable to include caregivers’ perspectives because they play an important role in patient care.

In conclusion, we found that the SICP may provide the opportunity for older patients with AML or MDS to share their personal values with their care team early in the course of their disease. The adapted SICP may facilitate earlier ACP discussions and allow oncologists to tailor care to what matters most to the patient, thereby improving patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Cancer and Aging Research Group and the Stakeholders for Care in Oncology and Research for our Elders Board (SCOREboard) who provided feedback. The authors thank Susan Rosenthal for her editorial assistance.

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (UG1CA189961; R00CA237744 [K.P.L.]), the National Institute of Aging at the National Institutes of Health (R33AG059206; K02AG062745 [B.K.]), Conquer Cancer American Society of Clinical Oncology and Walther Cancer Foundation Career Development Award (K.P.L.), the Wilmot Research Fellowship Award (K.P.L.), and the American Society of Hematology HONORS Award (M.L.). H.D.K. is supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging under Award #R33AG059206.

The content of this report is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Authorship

Contribution: M.L. and K.P.L. conceptualized and designed the study, performed data collection, data analysis and interpretation, wrote the manuscript, and approved the final version; C.S. conceptualized and designed the study, performed data collection, data analysis and interpretation, and approved the final version of the manuscript; J.H.M., S.N., R.B., T.C., and H.D.K. conceptualized and designed the study and approved the final version of the manuscript; E.W. performed data collection and analysis; J.L., E.H., K.O., A.B., and M.F. approved the final version of the manuscript; and B.K. conceptualized and designed the study and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: K.P.L. has served as a consultant to Pfizer and Seattle Genetics and has received honoraria from Pfizer. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Kah Poh Loh, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Department of Medicine, James P. Wilmot Cancer Center, 601 Elmwood Ave, Box 704, Rochester, NY 14642; e-mail: kahpoh_loh@urmc.rochester.edu.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Kah Poh Loh (kahpoh_loh@urmc.rochester.edu) or first author, Marissa LoCastro (Marissa_locastro@urmc.rochester.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.