Key Points

The AML BM milieu is unique and characterized by immunologic alterations differing from CML, B-ALL, and control BM.

Immune profiles of AML patients are related to patient age, T-cell receptor clonality, and survival.

Abstract

The immunologic microenvironment in various solid tumors is aberrant and correlates with clinical survival. Here, we present a comprehensive analysis of the immune environment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) bone marrow (BM) at diagnosis. We compared the immunologic landscape of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded BM trephine samples from AML (n = 69), chronic myeloid leukemia (CML; n = 56), and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) patients (n = 52) at diagnosis to controls (n = 12) with 30 immunophenotype markers using multiplex immunohistochemistry and computerized image analysis. We identified distinct immunologic profiles specific for leukemia subtypes and controls enabling accurate classification of AML (area under the curve [AUC] = 1.0), CML (AUC = 0.99), B-ALL (AUC = 0.96), and control subjects (AUC = 1.0). Interestingly, 2 major immunologic AML clusters differing in age, T-cell receptor clonality, and survival were discovered. A low proportion of regulatory T cells and pSTAT1+cMAF− monocytes were identified as novel biomarkers of superior event-free survival in intensively treated AML patients. Moreover, we demonstrated that AML BM and peripheral blood samples are dissimilar in terms of immune cell phenotypes. To conclude, our study shows that the immunologic landscape considerably varies by leukemia subtype suggesting disease-specific immunoregulation. Furthermore, the association of the AML immune microenvironment with clinical parameters suggests a rationale for including immunologic parameters to improve disease classification or even patient risk stratification.

Introduction

In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), myeloid lineage precursor cells modified by somatic mutations and transcriptomic dysregulation infiltrate the bone marrow (BM) and disrupt normal hematopoiesis. Although high-dose cytarabine–based (HD-cytarabine) multiagent chemotherapy forms the backbone for induction therapy, refractory and relapsed diseases remain common clinical challenges.1,2

Risk stratification of AML patients is used to predict therapy response, tailor treatment intensity, and guide clinical decision making when considering allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT). Patient age, performance status, blast karyotype, mutation status, and the combined European LeukemiaNet (ELN) genetics risk stratification score are well-established prognostic factors.1,3,4 In solid tumors, the clinicopathological prediction tool Immunoscore highlights the role of T cells as favorable prognostic biomarkers and is currently being validated by an international task force for possible clinical use.5 To date, tumor immunology has not been included in risk stratification of AML patients.

In AML, cytotoxic T cells fail to eliminate leukemic blasts and become senescent through the activity of immunosuppressive cells such as regulatory T cells (Tregs).6-8 Macrophages have been shown to become avidly M2 polarized, and the cytokine profile in peripheral blood (PB) of AML patients contributes in preventing T-cell activation and proliferation.9,10 The complex interactions among blast, stromal, and immune cells of the BM microenvironment create a multifaceted niche sustaining blast proliferation and conferring chemoresistance.11-14 Hence, systematic profiling of different immune cells is critical to improve our understanding of AML BM from a clinical perspective.

The immune system has been harnessed in the treatment of AML patients by inducing the graft-versus-leukemia response following allo-HSCT. Novel immunotherapeutic modalities, such as, immune checkpoint inhibitors, leukemia antigen-specific antibodies, and adoptive cell therapy, may challenge conventional chemotherapy-focused regimens with either improved efficacy or more tolerable side effects, as they have in the treatment of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) and solid tumors,15-20 yet little is known about the pretreatment immunologic landscape of AML BM and its potential immune biomarkers.

Here, we present a comprehensive analysis of the immunologic components of the AML BM niche at diagnosis. Using multiplexed immunohistochemistry (mIHC), we determined quantitative compositions and phenotypic states of millions of immune cells in AML BM. Host immunology was compared with cytogenetic and molecular genetic features, ELN risk classification, disease burden parameters, T-cell receptor (TCR) clonality, and patient demographics. Immunologic profiles were compared with previously published data from chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and B-ALL patients as well as controls. Novel immunologic biomarkers were identified in intensively treated patients.21,22 Taken together, we provide a single-cell, spatial, multiparametric protein-level analysis of the AML BM immunologic microenvironment with a clinical perspective.

Materials and methods

Study design

Patient samples

To investigate the immune cell and immunophenotype composition of leukemia BM, we collected diagnostic, pretreatment BM biopsy specimens from AML patients treated at the Department of Hematology, Comprehensive Cancer Center of the Helsinki University Hospital (HUS) between 2005 and 2015 (n = 69; Table 1). Due to ethical reasons, BM trephine samples could not be taken from healthy subjects. Therefore, we collected control BM biopsy samples in HUS from age- and sex-matched subjects without diagnosis of hematologic malignancy, chronic infection, or autoimmune disorder in 6 years of follow-up (n = 12; supplemental Table 1). As additional samples, we included data from immunologic analyses performed on pretreatment BM samples from CML (n = 56) and B-ALL (n = 52) patients previously published.21,22 AML, CML, B-ALL, and control samples were analyzed by the same mIHC platform. In addition, we collected paired BM and PB samples from AML patients at diagnosis (n = 8) and unpaired BM (n = 8) and PB (n = 11) samples from healthy volunteers and analyzed these by flow cytometry. All study subjects gave written informed research consent to the study and to the Finnish Hematology Registry. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and the HUS ethics committee (DNRO 303/13/03/01/2011).

Clinical data

We retrieved 96 clinical diagnostic baseline parameters, including PB and BM laboratory examination values, cytogenetics, molecular genetics, patient demographics, and medical history, from the Finnish Hematology Registry and clinical databases (supplemental Table 2).

Methods

Tissue microarrays (TMAs)

According to routine clinical practice to visually assess BM morphology, fresh BM biopsy samples were formalin fixed and paraffin embedded (FFPE) in the Department of Pathology, HUSLAB and stored at the Helsinki Biobank at HUS. Using hematopathologic expertise, we constructed TMA blocks by punching two 1 mm cores per donor located in areas of the BM biopsy characterized with high leukemic infiltrations (Figure 1A). Control cores were punched from representative areas.

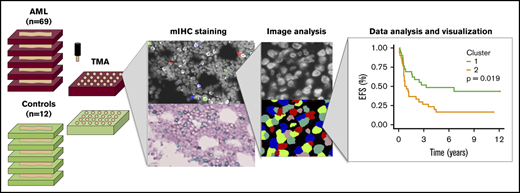

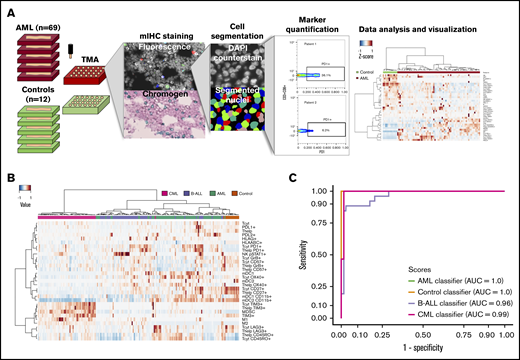

Immunocharacterization of the AML, B-ALL, CML, and control BM. (A) Visualization of the quantitative BM immunocharacterization pipeline. FFPE BM tissue blocks of AML patients (n = 69) and age- and sex-matched controls (n = 12) were retrieved from the Helsinki Biobank. TMAs were constructed from duplicate punches (1 mm in diameter) from each subject. TMAs were cut onto tissue slides and stained with mIHC consisting of ≤4 primary antibodies detected with fluorescence dyes and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) counterstain as well as 2 primary antibodies detected with chromogenic probes and hematoxylin counterstain. Tissue slides were scanned after both staining procedure and corresponding images registered to ensure that the location of individual cells is matched in parallel stainings. Following cell segmentation, marker colocalization and intensity were quantified in identified cells. (B) Immune cells (as a proportion of all cells in a TMA spot) and their immunophenotypes (as a proportion of their parent immune cell) derived from mIHC and computerized image analysis are plotted on a heatmap and organized by hierarchical clustering using Spearman correlation distance and the Ward linkage (ward.D2) method. Immunologic parameters are arranged in rows and patients in columns. Red denotes higher and blue lower proportions. (C) Using 10-fold crossvalidated elastic net–regularized logistic regression analysis, 4 subtype-specific classifiers were developed to identify AML, B-ALL, and CML patients and controls. Classifiers were developed with a training group (n = 94) and assessed with a test group (n = 95). The accuracy of the classifiers was evaluated on the test group with receiver-operator curves (AUC).

Immunocharacterization of the AML, B-ALL, CML, and control BM. (A) Visualization of the quantitative BM immunocharacterization pipeline. FFPE BM tissue blocks of AML patients (n = 69) and age- and sex-matched controls (n = 12) were retrieved from the Helsinki Biobank. TMAs were constructed from duplicate punches (1 mm in diameter) from each subject. TMAs were cut onto tissue slides and stained with mIHC consisting of ≤4 primary antibodies detected with fluorescence dyes and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) counterstain as well as 2 primary antibodies detected with chromogenic probes and hematoxylin counterstain. Tissue slides were scanned after both staining procedure and corresponding images registered to ensure that the location of individual cells is matched in parallel stainings. Following cell segmentation, marker colocalization and intensity were quantified in identified cells. (B) Immune cells (as a proportion of all cells in a TMA spot) and their immunophenotypes (as a proportion of their parent immune cell) derived from mIHC and computerized image analysis are plotted on a heatmap and organized by hierarchical clustering using Spearman correlation distance and the Ward linkage (ward.D2) method. Immunologic parameters are arranged in rows and patients in columns. Red denotes higher and blue lower proportions. (C) Using 10-fold crossvalidated elastic net–regularized logistic regression analysis, 4 subtype-specific classifiers were developed to identify AML, B-ALL, and CML patients and controls. Classifiers were developed with a training group (n = 94) and assessed with a test group (n = 95). The accuracy of the classifiers was evaluated on the test group with receiver-operator curves (AUC).

mIHC

The mIHC method combines 5-plex fluorescence and 3-plex chromogenic IHC (Figure 1A). For antibody panels, see supplemental Tables 3-5. Technical protocol and reagents used are listed in supplemental material of Blom et al, and more detailed information are described in previous publications and supplemental Methods.21-23

Image preprocessing

First, individual markers were deconvoluted from bright-field chromogen stainings.24 Mean fluorescent and bright-field images were downscaled by factor of 8 and image histograms adjusted to match each other. Mean images of each spots were registered using 2-dimensional phase correlation method.25 The analysis was implemented in a numerical computing environment (MATLAB, MathWorks).

Image analysis

After manual quality assurance, images out of focus and not correctly registered were eliminated from the analysis. Cell masks were segmented by parent immune cell markers (eg, CD3 for T cells) using adaptive Otsu thresholding and individual cells using gradient intracellular intensity. Cell segmentation, intensity measurements, and immune cell classification were performed with the image analysis platform CellProfiler 2.1.2 (Figure 1A).26-28 The total number of cells was quantified using TMA core area of binary-transformed 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole images using Fiji. Marker colocalization and cell classification were computed from integrated intensity values using single-cell analysis (FlowJo v10).

Besides actual BM cellularity, BM sampling from the patient, tissue processing in the clinical pathology department, extraction and insertion of tissue cores into TMAs, tissue slicing, slide coverslipping, and imaging may affect cell number in individual TMA core. TMA cores with <1000 cells were discarded from the analysis as they were not considered to be technically representative. Different cell types were quantified as either proportion to all cells (eg, CD3+CD8+ T-cell count to total cell count in a TMA core) or proportion of an immunophenotype defined by 1 or 2 markers to the cell type of interest (eg, CD3+CD8+/PD1+TIM3+ corresponds to the PD1+TIM3+ cell proportion of CD3+CD8+ T cells). Immunophenotyping results from duplicate cores of each patient were aggregated by their mean value. Values from duplicate tissue cores correlated well (r = 0.85, P < .001, Spearman correlation; supplemental Figure 1), supporting the use of TMA and duplicate cores to represent the BM biopsy.

Flow cytometry

Vitally frozen mononuclear cells (n = 500 000) from paired PB and BM samples of AML patients at diagnosis (n = 8) and unpaired PB (n = 8) and BM (n = 11) control samples were analyzed as a batch. AML and control samples were stained with 7 and 5 different 8-color panels, respectively, due to limited amount of control samples. The samples were analyzed with FACSVerse System (BD Pharmingen).

Statistical analysis

The Mann-Whitney U test (unpaired, 2 tailed) was used to compare 2 groups of continuous variables. To compare ≥3 groups, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used and, if needed, supplemented with Dunn’s test. P values were adjusted with Benjamini-Hochberg’s false discovery rate correction.29 Binomial categorical variables were compared with χ2 (frequency for each variable >5) or Fisher’s exact test (frequency for any variable ≤5). Correlation between 2 continuous variables was assessed with Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. For clustering analyses, data were median centered and maximum scaled. Normalized values were clustered by Spearman correlation distance and Ward linkage (ward.D2) methods. For survival analyses, Cox regression analysis (log-rank test) was used.

To classify patients into leukemic or control category, we developed four classifiers using 10-fold cross-validated elastic net regularized logistic regression models.30,31 The optimal shrinkage parameter λ and hyperparameter α were iterated 100-fold. Λ was tuned to 1 standard deviation of the minimum mean cross-validated error (λ.1se).

Results

Patient characteristics

The characteristics of AML patients are presented in Table 1. No significant difference between age and sex (Kruskal-Wallis test) was observed between the discovery cohort analyzed with mIHC and the flow cytometry cohort.

When comparing leukemia patients, the median age of CML patients and B-ALL patients was 57 years (range, 19-81 years) and 47 years (range, 16-72 years), respectively. 63% of CML and 48% of B-ALL patients were male. Control subjects were age and sex matched to all leukemia subtypes (>0.05, Mann-Whitney U test) with a median age of 55 years (range, 40-65 years) and male frequency of 58%. B-ALL patients were younger than AML (q < 0.001, Dunn’s test) and CML patients (q = 0.059).

Immune profiles in various leukemias are distinct

Using mIHC, we analyzed 9.6 million cells from 9 different immune panels, each consisting of ≤6 different primary antibodies and nuclear counterstaining on a cohort of 69 FFPE AML BM samples and 12 control BM combined into TMAs (Figure 1A). The panels consisted of T-cell, B-cell, natural killer (NK)–cell, macrophage, myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC)-like cell, myeloid dendritic cell, and T-cell activation, differentiation, and immune checkpoint markers (supplemental Tables 3-5). To characterize the immunophenotypic landscape, cells of interest were segmented and the integrated marker intensity in each pixel of segmented cells scaled between 0 and 1. Intriguingly, the immunologic profile of AML, B-ALL, and CML patients formed distinct disease-specific clusters (Figure 1B). While controls segregated apart from leukemia patients, we observed that their immune profile clustered closer to the profile of AML patients (Figure 1B).

To study the impact of each variable in separating patients by their immunologic phenotypes, we analyzed their differences between subtypes (Dunn’s test, Benjamini-Hochberg correction; supplemental Figure 2A). PD1, TIM3, and LAG3 have been recognized as markers of exhausted CD3+ T cells induced following long-lasting antigen exposure and chronic inflammation.15,32 PD1+ T cells were most prevalent in both acute leukemia subtypes, and LAG3+ T cells were depleted in all leukemia subtypes. Of particular interest, TIM3+ T cells were enriched in CML patients. Granzyme B (GrB) and CD57 production is sparked by cytolytic activity, especially on cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, and CD57 is also used to label senescent lymphocytes.33 The highest GrB+ and CD57+ levels in cytotoxic T cells were observed in B-ALL patients. Class I HLA is expressed on all nucleated cells and presents endogenic antigens primarily for T cells. The combination of HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C (HLA-ABC) was expressed in slightly albeit statistically significantly higher levels on control BM than in various leukemias. Interestingly, when studying cells of the myeloid lineage, CML patients differed from other subtypes by virtue of a higher proportion of both M1 (CD68+/cMAF-pSTAT1+) and M2-type (CD68+/cMAF+pSTAT1−) macrophages and MDSC-like (CD33+CD11b+HLADR−) cells but a lower proportion of both type I (CD11c+BDCA1+) and type II (CD11c+BDCA3+) myeloid dendritic cells (supplemental Figure 2A).

Given the distinct immunophenotypes between leukemias and controls, we hypothesized that these parameters alone could be used to classify disease subtypes without additional clinical variables. Patients were randomly divided into training (n = 94) and test groups (n = 95). Developing 4 subtype-specific classifiers with elastic net–regularized logistic regression with the training group translated into the accurate distinction of leukemia patients and control subjects in the test group (AML area under the curve [AUC] = 1.0, control AUC = 1.0, CML AUC = 0.99, and ALL AUC = 0.96; Figure 1C; supplemental Figure 2B; supplemental Table 7). Although subtype-specific immune profiles might reflect differences in the cell of origin and molecular genetics of different leukemias, results might also suggest differences in immune-editing mechanisms.

The AML BM microenvironment is shaped by immune regulation

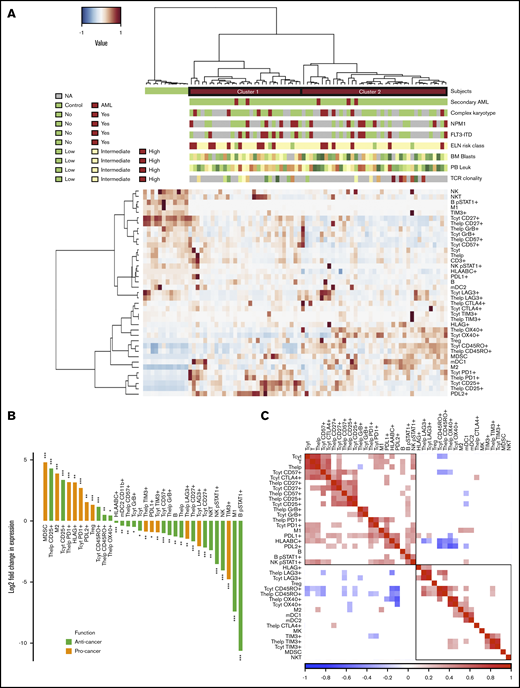

To dissect the immunologic contexture of the AML BM, we integrated quantified immune cell and their immunophenotypic proportions (Figure 2A). AML patients clustered into 2 major groups that were distinct from nonleukemic controls.

Comparison of the AML and control BM. (A) Immune cells (as proportion to all cells in a TMA spot) and their immunophenotypes (as proportion to their parent immune cell) derived from mIHC and computerized image analysis are plotted on a heatmap and organized by hierarchical clustering using Spearman correlation distance and the Ward linkage (ward.D2) method. Immunologic parameters are arranged in rows and patients in columns. Red denotes higher and blue lower proportions. Horizontal column bars indicate AML etiology, complex karyotype, NPM1 and FLT3-ITD molecular genetics, ELN 2017 risk classification, BM blast proportion (%), PB leukocyte count (E9/mL), and TCR clonality. (B) To focus only on significant comparisons (Benjamini-Hochberg corrected q < 0.05), the median AML-to-control ratio of each immunologic parameter was transformed to twofold logarithmic scale and grouped as anticancer (green) or procancer immunologic markers (orange) according to the literature. (C) Spearman correlation of immunologic parameters. Red denotes positive and blue negative correlations. Insignificant correlations (Benjamini-Hochberg corrected q < 0.05) were blanked. NA, values are not defined (gray bars in panel A).

Comparison of the AML and control BM. (A) Immune cells (as proportion to all cells in a TMA spot) and their immunophenotypes (as proportion to their parent immune cell) derived from mIHC and computerized image analysis are plotted on a heatmap and organized by hierarchical clustering using Spearman correlation distance and the Ward linkage (ward.D2) method. Immunologic parameters are arranged in rows and patients in columns. Red denotes higher and blue lower proportions. Horizontal column bars indicate AML etiology, complex karyotype, NPM1 and FLT3-ITD molecular genetics, ELN 2017 risk classification, BM blast proportion (%), PB leukocyte count (E9/mL), and TCR clonality. (B) To focus only on significant comparisons (Benjamini-Hochberg corrected q < 0.05), the median AML-to-control ratio of each immunologic parameter was transformed to twofold logarithmic scale and grouped as anticancer (green) or procancer immunologic markers (orange) according to the literature. (C) Spearman correlation of immunologic parameters. Red denotes positive and blue negative correlations. Insignificant correlations (Benjamini-Hochberg corrected q < 0.05) were blanked. NA, values are not defined (gray bars in panel A).

After extracting significantly different (Mann-Whitney U test, 2 tailed, q < 0.05) variables in AML patients compared with control BM subjects and with either an anticancer or procancer immunologic function, we discovered an intriguing dichotomous polarization (Figure 2B). Compared with control BM, AML BM contained decreased lymphocyte populations, including T cells, B cells (CD3−CD20+), NK cells (CD45+CD2+CD3−CD56+), and NK T cells (CD45+CD2+CD3+CD56+), as anticipated due to blast expansion. T cells displayed less cytolytic (GrB and CD57) and costimulation markers (CD27). Anti-inflammatory immune cells and immunophenotypes, such as the proportion of M2-polarized macrophages were enriched in AML BM, while activated pSTAT1+ B cells, M1 macrophages, and other conventional proinflammatory markers were depleted. In terms of immune checkpoint receptors, PD1 expression in T cells of AML patients exceeded expression in control subjects, while the contrary was observed for LAG3 and TIM3. No difference was noted in CTLA4 expression between AML and control BM.

Next, we studied the co-occurrence (Spearman correlation) of immune cell abundance and single-cell immunophenotypes in AML patients (Figure 2C). The proportion of helper and cytotoxic T cells and B cells as well as various lymphocyte phenotype markers correlated positively with each other (Figure 2C; supplemental Figure 3A-C). These included costimulatory (CD27), immune checkpoint T-cell markers (CTLA4 and PD1), and cytolytic T-cell markers (CD57), proportion of pSTAT1+ NK cells, M1-polarized macrophages, and overall expression of class I HLA and PDL1. Interestingly, the proportion of memory CD45RO+ T cells correlated negatively with the immunophenotypes described above (Figure 2C).34 No correlation between the proportion of cytotoxic T cells from all BM cells and their level of GrB was noted (supplemental Figure 3D). However, total PDL1+ expression in the BM correlated with CD3+CD4+/PD1+ (r = 0.55, P < .001; supplemental Figure 3E) and CD3+CD8+/PD1+ (r = 0.40, P < .001; supplemental Figure 3F).

An aging-related immune profile associates with poor prognosis and high TCR clonality

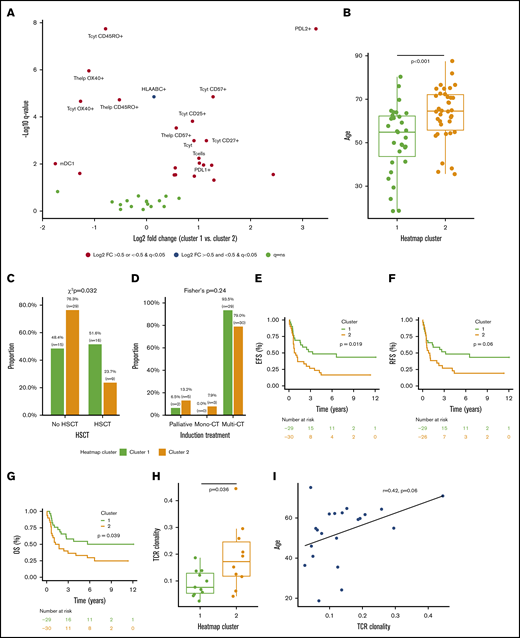

The integrated quantitative immune cell and phenotype profiles of AML patients diverged into 2 main clusters (Figure 2A). Compared with patients in cluster 2, patients in cluster 1 had a lower proportion of OX40+ and memory CD45RO+ T cells and a higher proportion of late-stage cytolytic CD57+, memory CD25+, and naive or central memory CD27+ T cells, as well as pronounced expression of PDL1/2 and classical class I HLA in all cells (Mann-Whitney U test, log2 fold change >0.75, q < 0.001; Figure 3A).

Clinicoimmunologic analysis of major AML immune profiles. (A) The proportion of immune cells and their single-marker immunophenotypes in AML patients (n = 69) in clusters 1 and 2 were compared (Mann-Whitney U test), P values corrected (Benjamini-Hochberg procedure), and results plotted on a volcano plot. Immunologic features with log2 fold change (FC) >0 are enriched in cluster 1 and features with log2 fold change <0 are more frequent in cluster 2. Age (Mann-Whitney U test) (B), allo-HSCT (χ2 test) (C), and induction treatment frequency (Fisher’s exact test) (D) distributions of patients in clusters 1 and 2 were compared. The survival of patients in clusters 1 and 2 who were intensively treated (HD-cytarabine–based induction treatment; n = 59) were compared (Cox regression, log-rank test) using EFS (E), relapse-free survival (RFS) (F), and overall survival (OS) (G) as an end point. TCR clonality was compared between patients in cluster 1 and cluster 2 (Mann-Whitney U test) (G) and correlated with patient age (Spearman correlation) (I).

Clinicoimmunologic analysis of major AML immune profiles. (A) The proportion of immune cells and their single-marker immunophenotypes in AML patients (n = 69) in clusters 1 and 2 were compared (Mann-Whitney U test), P values corrected (Benjamini-Hochberg procedure), and results plotted on a volcano plot. Immunologic features with log2 fold change (FC) >0 are enriched in cluster 1 and features with log2 fold change <0 are more frequent in cluster 2. Age (Mann-Whitney U test) (B), allo-HSCT (χ2 test) (C), and induction treatment frequency (Fisher’s exact test) (D) distributions of patients in clusters 1 and 2 were compared. The survival of patients in clusters 1 and 2 who were intensively treated (HD-cytarabine–based induction treatment; n = 59) were compared (Cox regression, log-rank test) using EFS (E), relapse-free survival (RFS) (F), and overall survival (OS) (G) as an end point. TCR clonality was compared between patients in cluster 1 and cluster 2 (Mann-Whitney U test) (G) and correlated with patient age (Spearman correlation) (I).

While neither patient cluster represented a traditional profile of immunosuppression, which could have accounted for the observed patient clustering, we then studied association with prognostic clinical parameters. We found no significant difference in the distribution of ELN risk class, complex karyotype, BM blast proportion, PB leukocyte count, or frequency of NPM1 or FLT3-ITD between clusters (supplemental Figure 4). However, patients in cluster 1 were significantly younger than those in cluster 2 (median 54.8 vs 64.6 years, P < .001, Mann-Whitney U test; Figure 3B). This reflected also on the treatment regimen, as patients in cluster 1 were treated more frequently with allo-HSCT and tended to receive HD-cytarabine induction therapy more often than patients in cluster 2 (Figure 3C-D). Furthermore, when studying only HD-cytarabine–treated AML patients (n = 59), we observed superior prognosis in cluster 1 subjects (Figure 3D-F) in terms of event-free survival (EFS; hazard ratio [HR], 2.10; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.11-3.97; P = .019, log-rank test), relapse-free survival (HR, 1.87; 95% CI, 0.97-3.60; P = .060), and overall survival (OS; HR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.02-3.92; P = .039).

We observed higher TCR clonality in AML patients in cluster 2 (P = .036; Figure 3G). In addition, higher TCR clonality correlated with higher age (r = 0.42, P = .06; Spearman correlation; Figure 3H). With regards to immunologic phenotypes, higher TCR clonality correlated most with OX40 expression in cytotoxic (r = 0.50, P = .022) and helper T cells (r = 0.53, P = .015; supplemental Figure 5A-B). However, no association between TCR clonality and BM blast proportion, PB leukocyte count, and NPM1+ or FLT3-ITD+ frequency was observed (supplemental Figure 5C-F). While higher clonality trended to associate with complex karyotype and higher ELN risk class, patient number remained insufficient to reach significance (supplemental Figure 5G-H).

Screening for novel immunologic prognostic biomarkers

Next, we aimed to discover previously unidentified immunologic prognostic biomarkers. EFS was selected as the primary end point, because baseline immunology may impact chemotherapy responses.13,35-37 As induction therapy protocol reflects performance status and dramatically affects survival, the prognostic impact of each clinicoimmunologic parameter was investigated individually in AML patients treated with HD-cytarabine (n = 59; Cox regression).

Clinical parameters such as PB leukocyte count (E9/L; HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 1.00-1.01; P = .014, log-rank test) and age >60 years (HR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.03-3.56; P = .037), as well as novel immune predictors such as the proportion of M1-polarized macrophages (%; HR, 2.18; 95% CI, 1.14-4.19; P = .008) and the proportion of FOXP3+ helper T cells, including Tregs (%; HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.00-1.28; P = .049), predicted poor prognosis, while the proportion of CTLA4−LAG3− T-helper cells (%; HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.96-1.00; P = .013) was associated with superior survival (Figure 4A; supplemental Table 8). To visualize their prognostic impact, we categorized M1 macrophages and Tregs into tertiles. As the highest 2 tertiles were superimposed, their EFS curves were combined against the lowest tertile (Figure 4B-C). To study multicollinearity, the HR and 95% CI of categorized M1 macrophages and Tregs were compared both in a univariate setting and by combining with an essential clinical covariate in a multivariate setting (Forest plot, Cox regression). The HR of either M1-polarized macrophages (Figure 4D) or Tregs (Figure 4E) remained virtually unaffected when studied in combination with either FLT3-ITD+, BM blast (%), PB leukocyte (10E9/mL), complex karyotype, or patient age but lost significance when NPM1+ or ELN 2017 risk classification was added with either covariate.

Immunologic prognostic biomarkers in intensively treated AML patients (HD-cytarabine–based induction treatment; n = 59). (A) Volcano plot of the HRs for an EFS incident of immune cells and their immunophenotypes and PB and BM laboratory values. Variables increasing the risk for an EFS event have a positive log10 HR and deviate to the right side of the plot. Parameters with a negative log10 HR diverge to the left. Survival plot of the proportion of CD68+ monocytes expressing pSTAT1+cMAF− (M1-like monocytes) (B) and helper T cells expressing FOXP3+ (%, regulatory T cells) (C). Covariates were divided into tertiles, and the highest 2 subgroups were combined. A forest plot displaying the HR and 95% CI of the categorized proportion of M1-like monocytes (D) and Tregs (E) in univariate and combined with another essential clinical biomarker (Cox regression analysis).

Immunologic prognostic biomarkers in intensively treated AML patients (HD-cytarabine–based induction treatment; n = 59). (A) Volcano plot of the HRs for an EFS incident of immune cells and their immunophenotypes and PB and BM laboratory values. Variables increasing the risk for an EFS event have a positive log10 HR and deviate to the right side of the plot. Parameters with a negative log10 HR diverge to the left. Survival plot of the proportion of CD68+ monocytes expressing pSTAT1+cMAF− (M1-like monocytes) (B) and helper T cells expressing FOXP3+ (%, regulatory T cells) (C). Covariates were divided into tertiles, and the highest 2 subgroups were combined. A forest plot displaying the HR and 95% CI of the categorized proportion of M1-like monocytes (D) and Tregs (E) in univariate and combined with another essential clinical biomarker (Cox regression analysis).

We also screened for immune parameters associated with adverse ELN risk class and NPM1 and FLT3 mutations, but findings remained nonsignificant after P value adjustment (supplemental Figure 6).

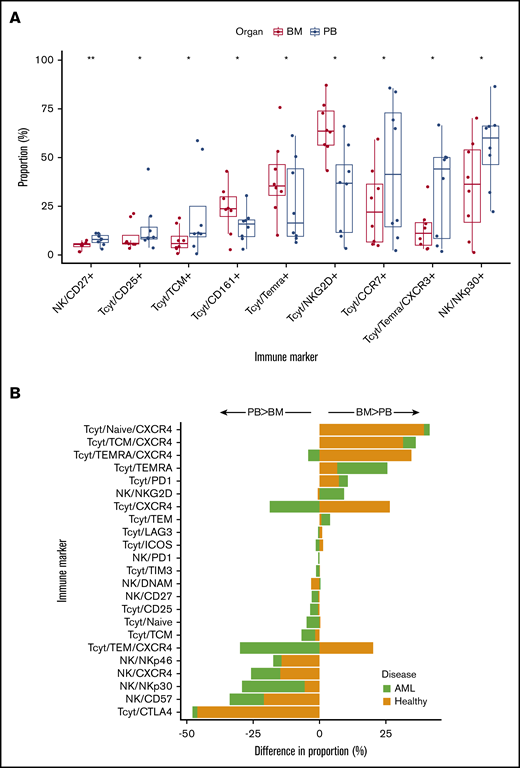

Immune profiles differ by sample type

The leukemia BM represents a particular milieu promoting leukemic proliferation. To investigate whether the BM immunologic microenvironment would differ from the PB, we characterized a total of seven 8-color panels of CD8+ T- and NK-cell immunophenotype markers in paired BM and PB samples of AML patients (n = 8) at diagnosis (Figure 5A; supplemental Figures 7A-B and 8; supplemental Tables 9 and 10). NK cells expressed less of the activating receptor NKp30 and CD27 downregulating cytotoxicity in BM than in PB.38 CD45RA+ effector memory T cells (TEMRA) were more prevalent in BM but these expressed significantly less CXCR3 associated with Th1-type inflammatory reactions than in the PB.39 However, no clear differential pattern in immune checkpoint expression was observed between AML BM and PB.

Comparison of immunophenotypes in BM and PB samples. (A) Boxplots and dotplots displaying only significant comparisons (Mann-Whitney U test, P < .05) of CD8+ T- and NK-cell immunophenotypes quantified from paired BM and PB samples of AML patients at diagnosis. The center line of boxplots displays the median value and whiskers the interquartile range. The color of the bar reflects whether the immunophenotype is from BM (red) or PB (blue). P values for the comparison are listed on the top (**P < .01, *P < .05). (B) Differences in the median proportion of immunophenotypes from BM and PB samples in AML patients and healthy controls. The length of the bar signifies the amplitude of the difference between BM and PB samples (value in BM subtracted by value in PB). Bars orientated to the right represent immunophenotypes more prevalent in BM than PB samples. All common immunophenotypes analyzed with flow cytometry in both AML and control BM and PB samples are presented. As control samples were unpaired, no P values were computed.

Comparison of immunophenotypes in BM and PB samples. (A) Boxplots and dotplots displaying only significant comparisons (Mann-Whitney U test, P < .05) of CD8+ T- and NK-cell immunophenotypes quantified from paired BM and PB samples of AML patients at diagnosis. The center line of boxplots displays the median value and whiskers the interquartile range. The color of the bar reflects whether the immunophenotype is from BM (red) or PB (blue). P values for the comparison are listed on the top (**P < .01, *P < .05). (B) Differences in the median proportion of immunophenotypes from BM and PB samples in AML patients and healthy controls. The length of the bar signifies the amplitude of the difference between BM and PB samples (value in BM subtracted by value in PB). Bars orientated to the right represent immunophenotypes more prevalent in BM than PB samples. All common immunophenotypes analyzed with flow cytometry in both AML and control BM and PB samples are presented. As control samples were unpaired, no P values were computed.

To discern any disease-specific impact on differential BM vs PB composition, we compared the NK and CD8+ T-cell immunophenotypes in both sample types of AML patients and healthy controls. Due to limited availability of control samples, 11 PB and 9 BM unpaired samples from 16 healthy subjects were analyzed with flow cytometry. Comparative analysis was performed by comparing the difference in median values of immunophenotypes in AML BM vs PB samples to control BM vs PB samples.

Healthy subjects did not differ from AML patients in terms of age (46.6 ± 29.4 [median ± interquartile range] vs 58.4 ± 27.9, Mann-Whitney U test, P = .15) or sex (70.6% male vs 75% male, χ2 test, P = 1.0). When studying only significantly differing markers presented in Figure 5A, we observed that central memory CD8+ T cells, NK/NKp30+, NK/CD27+, and CD25+CD8+ T cells also differed more between AML than control BM and PB samples (Figure 5B). Moreover, CD45RA+ effector memory T cells, which were more frequent in AML BM than PB samples, also differed more in AML than control BM vs PB samples.

Discussion

Despite that deviations in the immune system have been recognized as one of the hallmarks of cancer and that the immune microenvironment affects clinical survival and treatment responses in solid tumors, their contribution in leukemia is unknown.40,41 Here, we compared the BM immunologic landscape of AML, ALL, and CML patients at diagnosis to controls using a single-cell in situ mIHC approach combined with computerized image analysis for fast and objective immune cell quantification. We observed immune profiles were capable of segregating distinct leukemia subtypes and controls with high confidence without prior information on patient characteristics.

Due to our primary interest in the BM immunologic landscape from a T-cell perspective, and because myeloid markers might be expressed in immature cell subsets, the characterization panels focused on lymphoid markers. The expression pattern of various immunologic phenotypes varied by abundance in a subtype-dependent fashion.

In B-ALL BM, we noted a higher proportion of cytolytic markers and immune checkpoint receptor PD1 compared with other leukemias. In CML, the expression pattern of TIM3 differed from other immune checkpoint receptors by being notably enriched compared with other leukemias and control. The reason for this contrast remains unknown but might pose an interesting therapeutic target along with other immunomodulatory approaches for tyrosine kinase inhibitor–resistant patients or following treatment discontinuation.42-45 In addition, compared with acute leukemia and control BM, we observed a particularly high macrophage polarization toward both M1 and M2 phenotypes and an abundance of MDSC-like cells in CML BM. However, despite classifying MDSC-like cells with 3 lineage markers according to recommendations (CD11b+CD33+HLADR−), we recognize that these might partly represent expanded malignant CML cells.34

Compared with other leukemias, the expression of immune checkpoint receptors was low in AML. However, we observed substantial heterogeneity between AML patients, suggesting that similar immunologic phenomena might not govern in all patients. The rich immunologic variability could be categorized into 2 main age-dependent immunologic signatures, which differed by TCR clonality and clinical prognosis, but no association with other well-established prognostic markers was noted.

Age-related thymic involution, inapt responses of peripheral T cells to inflammatory stimulations, and expansion of effector memory clones account for the decline in the TCR repertoire during ageing.46-50 Our results suggest that increasing TCR clonality could be associated with worse prognosis, but our patient number (n = 20) remained insufficient to confirm this hypothesis.

Cancer cells have been shown to orchestrate immunosuppressive changes in surrounding cells of the microenvironment enabling immune evasion.51-54 Opposite well-reported findings have been reported, emphasizing that the immune system’s role in AML is not evident.55 Here, we describe an elevated M2/M1 macrophage phenotype ratio at diagnosis and an increased number of MDSC-like cells and proportion of Tregs, while expression of GrB, pSTAT1, and CD27, representing lymphocyte activity and costimulation, were found to be decreased in BM of patients with AML. With respect to immune checkpoint molecules, PD1 expression was upregulated but LAG3 and TIM3 levels were downregulated in T cells of AML patients.

High heterogeneity among AML patients suggests various immunoregulatory mechanisms and possibly also differences considering immunotherapy applications. Of the immunophenotypic markers upregulated in AML only, the PD1/PDL1 signaling pathway can currently be targeted. Hypomethylating agentshave been shown to upregulate PD1/PDL1 expression in myelodysplastic syndrome.56 Interestingly, the combination of hypomethylating agents and anti-PD1 has induced encouraging response rates, and pretherapy T-cell numbers are associated with treatment response.57

A comprehensive immunologic characterization and clinical parameters in the AML BM has not been performed. Recently, the expression of immune checkpoint receptors and ligands in AML patients was elegantly analyzed at diagnosis and relapse and compared with healthy controls.58 The authors demonstrated immunologic heterogeneity between BM and PB samples with flow cytometry. Further reinforcing the findings of our study, the authors described higher PD1 and OX40 expression in cytotoxic T cells in AML patients at diagnosis compared with controls.

In immuno-oncology, T cells have been perceived as the key effector cell type partly following remarkable responses related to immune checkpoint, bispecific antibody, and adoptive T-cell therapies.17-20,32 The immunohistochemical tool Immunoscore further highlights the positive prognostic value associated with high T-cell infiltration across various cancers.5,41 Immunologic populations in AML BM have not been previously analyzed for prognostic biomarkers. In this study, we discovered that high proportion of Tregs predicted inferior survival in AML. Although requiring further investigation, Tregs might mediate this effect by interfering with immunologic synapse formation, previously reported to be dysfunctional in AML patients.8 In addition, we identified higher proportion of pSTAT1+cMAF− macrophages and lower proportion of LAG3−CTLA4− helper T cells as novel biomarkers of worse prognosis. Nevertheless, their validation in larger cohorts with flow cytometry is warranted.

Immunosuppressive phenotypes and dysfunction in T cells in AML patients have been observed, although mostly in studies conducted using PB samples for practical reasons.6,8-10,12-14,59,60 We demonstrate that the BM and PB are dissimilar in terms of immune cell phenotypes, also when compared with healthy control BM and PB samples, and could be crucial in the design of immunology studies on AML.

Taken together, the AML BM milieu is unique and characterized by immunologic alterations differing from CML, B-ALL, and control BM. In addition, while the molecular genetic profile of AML has been thoroughly studied, implementing immunologic parameters might not only enhance disease and risk classification but also at best allow improved individualization of therapy.3,4

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the members of the Hematology Research Unit Helsinki for discussions and technical help. They thank the Helsinki Biobank and the Digital and Molecular Pathology Unit supported by Helsinki University and Biocenter Finland for digital microscopy services.

This study was supported by the University of Helsinki’s Doctoral Programme in Biomedicine and personal grants (O.B.) from the Emil Aaltonen Foundation, Magnus Ehrnrooth Foundation, Hematology Research Foundation (Veritautien tutkimussäätiö), the Finnish Foundation of Medicine (Suomen Lääketieteen Säätiö), the Finnish Medical Society (Finska Läkaresällskapet), the Orion-Farmos Foundation, and the Paulo Foundation; and research grants (S.M.) from the Finnish Cancer Institute, Finnish Cancer Organizations, the Sigrid Juselius Foundation, the Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation, the Relander Foundation, state funding for university-level health research in Finland, and an investigator-initiated research grant from Novartis.

Authorship

Contribution: K.P., O.B., O.D., O.K., S.B., T.P., and S.M. contributed to conception and design; A.R., H.H., H.L., O.B., O.D., K.P., K.V., M.I., M.E.M., P.K., S.S., and S.M. contributed to collection and assembly of data; C.P., H.H., K.P., M.I., O.B., O.D., P.M.R., R.T., S.B., S.M., and T.P. contributed to data analysis and interpretation; and all authors contributed to manuscript writing and final approval of manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: K.P. has received honoraria and research funding from Celgene, Incyte, Novartis, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. S.M. has received honoraria and research funding from Pfizer, Novartis, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. S.B. is an employee of Fimmic Oy. C.P. and P.M.R. are employees of Novartis Pharmaceuticals. H.H. has received research funding from Incyte. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Satu Mustjoki, Hematology Research Unit Helsinki, University of Helsinki and Helsinki University Hospital Comprehensive Cancer Center, Haartmaninkatu 8, FIN-00290 Helsinki, Finland; e-mail: satu.mustjoki@helsinki.fi; and Oscar Brück, Hematology Research Unit Helsinki, University of Helsinki and Helsinki University Hospital Comprehensive Cancer Center, Haartmaninkatu 8, FIN-00290 Helsinki, Finland; e-mail: oscar.bruck@helsinki.fi.

References

Author notes

K.P., T.P., and S.M. contributed equally to this study.

Original images were deposited to an open data repository with the BioImage Archive accession number S-BIAD12.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Processed multiplexed immunohistochemistry data and essential clinical data can be found in supplemental Table 6.