Diverse death stimuli including anticancer drugs trigger apoptosis by inducing the translocation of cytochrome c from the outer mitochondrial compartment into the cytosol. Once released, cytochrome c cooperates with apoptotic protease-activating factor-1 and deoxyadenosine triphosphate in caspase-9 activation and initiation of the apoptotic protease cascade. The results of this study show that on death induction by chemotherapeutic drugs, staurosporine and triggering of the death receptor CD95, cytochrome c not only translocates into the cytosol, but furthermore can be abundantly detected in the extracellular medium. The cytochrome c release from the cell is a rapid and apoptosis-specific process that occurred within 1 hour after induction of apoptosis, but not during necrosis. Interestingly, elevated cytochrome c levels were observed in sera from patients with hematologic malignancies. In the course of cancer chemotherapy, the serum levels of cytochrome c in the majority of the patients grew rapidly as a result of increased cell death. These data suggest that monitoring of cytochrome c in the serum of patients with tumors might serve as a useful clinical marker for the detection of the onset of apoptosis and cell turnover in vivo.

Introduction

Damaged cells can die through different mechanisms. Two major forms of cell death are necrosis and apoptosis.1Apoptosis, also known as programmed cell death, is the form of cell elimination commonly occurring during development as well as in many physiologic and pathologic processes.2 3 In contrast, necrosis occurs mostly when noxious stimuli disintegrate the function of various cellular compartments leading to plasma membrane damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cell lysis.

The induction of the endogenous death machinery can be initiated via 2 principal signaling pathways.4 One involves the ligation of death receptors, such as CD95 and tumor necrosis factor–receptor (TNF-R1), which on binding of the adapter protein FADD, recruit procaspase-8 into the death-inducing signaling complex. Another pathway that is triggered by a number of apoptotic stimuli such as anticancer drugs or irradiation is essentially controlled at the mitochondrion. An initial event is the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria into the cytosol.5,6 Once released, cytochrome c together with deoxyadenosine triphosphate binds to apoptotic protease-activating factor-1 (Apaf-1), leading to an unmasking of its caspase recruitment domain and the subsequent binding and autoproteolytic activation of procaspase-9. The complex of procaspase-9, cytochrome c, and Apaf-1 is known as the apoptosome. Similarly to caspase-8, active caspase-9 then proteolytically activates downstream effector caspases, which by degrading various cellular proteins propagate the apoptotic signal. Both the death receptor and the mitochondrial pathway can synergize and amplify their own signals by positive feedback loops. First, the BH3-only Bax-interacting protein Bid, which is a substrate of caspase-8, becomes activated in the death receptor-mediated pathway and induces the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria.7,8Activated Bid triggers a conformational change of another proapoptotic molecule, Bax, which leads to its oligomerization and subsequent insertion into the outer mitochondrial membrane and finally to cytochrome c release.9,10 Second, caspase-9 can activate procaspase-8 via the caspase-3 and caspase-6 cascade, thus amplifying the receptor-derived signal and via Bid cleavage also the mitochondrial pathway.11 12

A crucial step controlling the apoptosome pathway is the release of cytochrome c. It is a rapid and presumably irreversible process that appears to be both energy- and caspase-independent.13 The mechanism by which cytochrome c translocates to the cytosol during apoptosis has not been elucidated in detail and is still a matter of debate. Much of the controversy has focused on the mode of action of the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members such as Bad, Bak, Bax, and Bid, which cause the release of cytochrome c, whereas the antiapoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL suppress the translocation of cytochrome c.5-10,14 The functions of the proapoptotic Bcl-2 members have been proposed to involve the formation of pores in the outer mitochondrial membrane through which cytochrome c diffuses. Other models suggest that these proteins affect channels in the outer or the inner mitochondrial membrane, such as the permeability transition pore, thereby inducing hyperpolarization and permeability transition.15 It has been proposed that these events cause the entry of water and solutes, matrix swelling, and rupture of the outer membrane, which allows the passive release of cytochrome c. However, it has been observed that in many cell types the release of cytochrome c occurs before or in the absence of a change in mitochondrial permeability,13 suggesting that this process involves additional or other mechanisms than opening of the permeability transition pore.

In the present study, our results show that cytochrome c not only enters the cytoplasm on apoptosis induction, but furthermore is also released from the “committed to die cell” into the extracellular medium. The externalization of cytochrome c is a rapid and apoptosis-specific process because it was not observed on necrosis induced by diverse triggers. A release of cytochrome c into the extracellular medium was detected during apoptosis induced by various stimuli such as staurosporine, anticancer drugs, and CD95 ligation in different cell types. Moreover, even in the serum of patients with hematologic malignancies, elevated cytochrome c levels were found, which increased on induction of antitumor chemotherapy. These results suggest that monitoring of extracellular cytochrome c levels may be used as a marker to monitor cell death in vivo.

Materials and methods

Materials and cell culture

The human Jurkat T-cell line and mouse L929 fibroblasts were grown in 5% CO2 at 37°C using RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, penicillin, and streptomycin (all from Gibco BRL, Eggenstein, Germany). Etoposide, actinomycin D, and doxorubicin were purchased from Sigma (Deisenhofen, Germany) and staurosporine from Roche Diagnostics (Mannheim, Germany). All stimuli were dissolved in ethanol and kept at −70°C. An agonistic anti-CD95 monoclonal antibody (mAb) was obtained from Biocheck (Münster, Germany) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) from the laboratory of Dr W. Fiers (Ghent, Belgium). The broad-range caspase inhibitor benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp-fluoromethylketone (zVAD-fmk) was purchased from Enzyme Systems (Dublin, CA); all other chemicals were from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) or Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany).

Serum sample processing

Sera (3 mL/person) from 6 men and 11 women, aged 19 to 78 (median, 48), with mostly hematologic malignant diseases were analyzed. Seven patients had acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and 6 had non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). One patient each with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), Hodgkin disease (HD), breast carcinoma, and non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) were also studied. All patients received multidrug chemotherapy as indicated in Table 1. Serum samples were collected before and at several time points during therapy. Corresponding control samples were collected from 8 healthy individuals. All samples were precleared by centrifugation at 10 000g, 4°C for 15 minutes. Subsequently, the immunoglobulin content was reduced by 2 rounds of extraction with 2 mL protein G-Sepharose (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) for 1 hour. Precleared sera were kept at −70°C until use for immunoprecipitation.

Summary of patients participating in the study

| Diagnosis . | Patient no. . | Therapy protocol* . | Maximal Cyt c level (d)† . | Maximal LDH level (d)† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AML | 1, 3, 6, 11 | TAD (thioguanine, cytosine arabinoside, daunorubicin)28 | 3, 4, 2, 2 | 0, 5, 0, 4 |

| 2 | HAM (high-dose cytosine arabinoside, mitoxantrone)29 | 3 | 0 | |

| 14 | Cytosine arabinoside‡ | 2 | 0 | |

| 9 | Cytosine arabinoside, daunorubicin—remission support281-153 | 1 | 0 | |

| ALL | 13 | GMALL (for elderly patient)1-155,1-154 | 3 | 1 |

| NHL | 10 | DexaBEAM (dexamethasone, carmustine, melphalan, cytosine arabinoside, etoposide)30 | 2 | 0 |

| 4, 17 | CHOEP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, etoposide, prednisolone) + anti-CD2031 32 | 2, 4 | 0, 0 | |

| 12, 16 | CHOP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisolone, doxorubicin)33 | 2, 1 | 4, 0 | |

| 5 | ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide)34 | 2 | 0 | |

| Morbus Hodgkin | 7 | DHAP (dexamethasone, high-dose cytosine arabinoside, cisplatin)351-159 | 4 | 3 |

| NSCLC | 15 | Cisplatin, etoposide | 1 | 0 |

| Breast cancer | 8 | Epirubicin, paclitaxel36 | 2 | 1 |

| Diagnosis . | Patient no. . | Therapy protocol* . | Maximal Cyt c level (d)† . | Maximal LDH level (d)† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AML | 1, 3, 6, 11 | TAD (thioguanine, cytosine arabinoside, daunorubicin)28 | 3, 4, 2, 2 | 0, 5, 0, 4 |

| 2 | HAM (high-dose cytosine arabinoside, mitoxantrone)29 | 3 | 0 | |

| 14 | Cytosine arabinoside‡ | 2 | 0 | |

| 9 | Cytosine arabinoside, daunorubicin—remission support281-153 | 1 | 0 | |

| ALL | 13 | GMALL (for elderly patient)1-155,1-154 | 3 | 1 |

| NHL | 10 | DexaBEAM (dexamethasone, carmustine, melphalan, cytosine arabinoside, etoposide)30 | 2 | 0 |

| 4, 17 | CHOEP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, etoposide, prednisolone) + anti-CD2031 32 | 2, 4 | 0, 0 | |

| 12, 16 | CHOP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisolone, doxorubicin)33 | 2, 1 | 4, 0 | |

| 5 | ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide)34 | 2 | 0 | |

| Morbus Hodgkin | 7 | DHAP (dexamethasone, high-dose cytosine arabinoside, cisplatin)351-159 | 4 | 3 |

| NSCLC | 15 | Cisplatin, etoposide | 1 | 0 |

| Breast cancer | 8 | Epirubicin, paclitaxel36 | 2 | 1 |

AML indicates acute myeloid leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer.

Detailed information can be obtained from authors W.E.B. and M.K.

Day 0 indicates that maximal cytochrome c or LDH levels were detected before the onset of chemotherapy.

Day 1-7: cytosine arabinoside.

Day 1-25: prednisolone; day 1: vincristine; day 5, 12, 19, 26: vincristine, daunorubicin; day 5-31: L-asparaginase (every second day).

German Multicenter ALL study.

Day 1-5, day 11-14: dexamethasone; day 1-3: cyclophosphamide; day 4, 11: vincristine; day 4, 7, 11, 14: idarubicin; (intradural therapy, day 1, 10, 18: methotrexate; day 10, 18: dexamethasone, cytosine arabinoside).

With modifications.

Cell extracts, immunoprecipitation, and immunoblotting

To determine the cellular cytochrome c content, cells were collected by centrifugation, washed in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and extracted in cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100 containing 3 μg/mL aprotinin, 3 μg/mL leupeptin, 3 μg/mL pepstatin, and 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Extracellular fractions and cell lysates were precleared by centrifugation at 10 000g, 4°C for 15 minutes prior to immunoprecipitation. Supernatants were kept at −70°C until use. Immunoprecipitations were performed in a volume of 4 mL in a rotator at 4°C for 4 hours using anticytochrome c mAb 6H2.B4 (Pharmingen Europe, Hamburg, Germany) at a final concentration of 0.5 μg/mL. The cytochrome c–mAb complexes were precipitated for 1 hour with 40 μL of a 50% slurry of protein G-Sepharose in PBS. Precipitates were harvested by short centrifugation (2000 rpm, 10 seconds, 4°C) and washed 4 times with cold washing buffer (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 μg/mL aprotinin, 1 μg/mL leupeptin). Proteins were eluted by boiling the precipitates in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-loading buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol, separated under reducing conditions on a 12% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and subsequently transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Amersham Buchler, Braunschweig, Germany). Equal loading was confirmed by staining of the proteins with Ponceau S. Subsequently, membranes were blocked for 1 hour with 5% nonfat dry milk powder in Tris-buffered saline (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl) and 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST) and then immunoblotted with anticytochrome c mouse mAb 7H8.2C12 (Pharmingen Europe) for 2 hours. After washing in TBST the blots were incubated with antimouse horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour. Finally, the membranes were washed extensively in TBST and developed using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Amersham Buchler). The quantity of immunoprecipitated cytochrome c was determined by densitometric analysis using the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD) image software. The values of the patients' sera were always normalized with the amount of cytochrome c from healthy controls that were incorporated in each Western blot analysis. The relative cytochrome c levels indicate the ratio of the densitometric values from the patients and the mean values of control. Sera from control persons revealed only low levels of detectable cytochrome c, and mean values did not reveal large interindividual differences (< 9%).

Measurement of cell death

For determination of apoptosis, Jurkat and L929 cells were seeded in microtiter plates and treated with the cytotoxic agents for the indicated time points. Apoptotic, hypodiploid nuclei were measured as described previously.16 Briefly, apoptotic nuclei were prepared by lysing cells in a hypotonic lysis buffer (1% sodium citrate, 0.1% Triton X-100, 50 μg/mL propidium iodide) and subsequently analyzed by flow cytometry. In parallel, cell death as assessed by membrane damage was determined by the uptake of propidium iodide (2 μg/mL in PBS; Sigma) into nonfixed cells. After 10 minutes, red fluorescence (FL-3) was measured by flow cytometry using a FACScalibur (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) and CellQuest analysis software (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Cell viability was also determined by monitoring the release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), which was measured by the central laboratory of the medical clinic. To obtain total LDH activity, cells were lysed with 1% Triton X-100. The percentage of LDH release represents the fraction of LDH activity found in the supernatants with respect to the overall enzyme activity.

Results and discussion

One of the earliest events in apoptosis induced by death receptor–independent mechanisms is the translocation of cytochrome c from the mitochondrial intermembrane space into the cytosol.5,6 Released cytochrome c then activates the apoptosome-dependent death machinery by binding to Apaf-1, resulting in the subsequent recruitment and activation of procaspase-9.17 Our initial experiments in cells overexpressing a green fluorescent protein–tagged version of cytochrome c revealed that following translocation of cytochrome c the fluorescent signal was rapidly lost during apoptosis (data not shown). Therefore, we investigated whether cytochrome c was degraded or could be detected in the extracellular medium on induction of cell death.

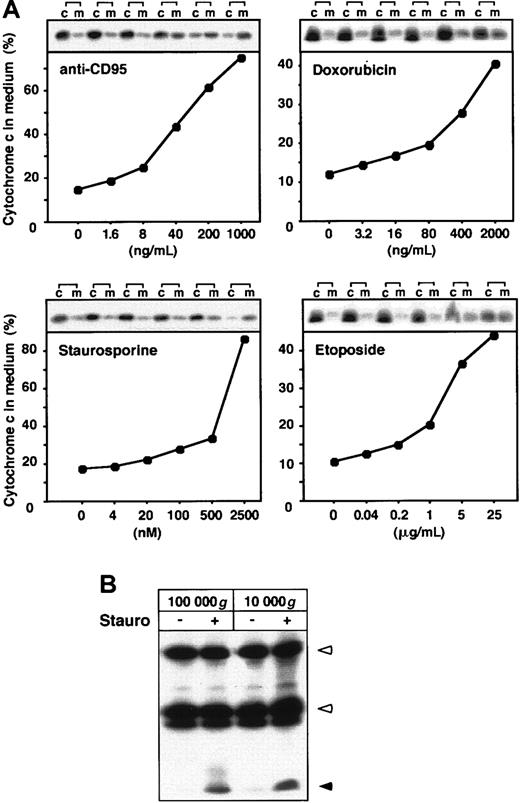

To our surprise, large amounts of cytochrome c were found in the culture medium of Jurkat T cells on apoptosis induction by several stimuli including the protein kinase inhibitor staurosporine, agonistic anti-CD95 antibody, and the anticancer drugs etoposide and doxorubicin (Figure 1A). This event was accompanied by a decrease of cytochrome c in the corresponding cellular fractions. The weaker cytochrome c release observed in anticancer drug-treated cells could be attributed to a slower progression of cell death. These results are consistent with previous data showing that cytochrome c release into the cytosol, caspase activation, and final cell death occur more slowly in drug-induced than in CD95 receptor-mediated cell death.18 In response to staurosporine and anti-CD95, 2 potent apoptosis inducers, almost all of the cytochrome c was detected in the culture medium. The extracellular release of cytochrome c in response to the proapoptotic agents was dose dependent (Figure 1A). The concentration dependency correlated with the induction of apoptosis in Jurkat cells as described previously.11 19 Similar to Jurkat T-cells, in murine L929 cells cytochrome c was readily released in cultures following induction of apoptosis by several stimuli (data not shown). To analyze whether the released cytochrome c was present in a soluble form or associated with apoptotic bodies or other membrane fractions, we cleared the supernatants by ultracentrifugation. Cytochrome c was not recovered in the pellets but was still present in the supernatants (Figure 1B), indicating that it was indeed released as a soluble protein.

Various apoptotic stimuli lead to the extracellular release of cytochrome c.

(A) Jurkat cells (5 × 106) were cultured in growth medium and either left untreated or stimulated for 15 hours with the indicated concentrations of anti-CD95 mAb and staurosporine or for 24 hours with the indicated concentrations etoposide or doxorubicin. Cytochrome c was precipitated from the culture medium (m) and the cellular extracts (c) with antibodies against the native molecule. The immunoprecipitated material was separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting. The quantity of cytochrome c was then determined by densitometric analysis. The graphs display the amount of cytochrome c in the culture medium relative to the total content of cytochrome c present in medium and cells. (B) Cytochrome c is released from cells as a soluble protein. Supernatants of Jurkat cells treated for 15 hours with staurosporine were centrifuged for 30 minutes at 10 000g or 100 000g and immunoblotted as described above. Open arrowheads indicate heavy chain and light chain of anticytochrome c antibody; closed arrowhead indicates cytochrome c.

Various apoptotic stimuli lead to the extracellular release of cytochrome c.

(A) Jurkat cells (5 × 106) were cultured in growth medium and either left untreated or stimulated for 15 hours with the indicated concentrations of anti-CD95 mAb and staurosporine or for 24 hours with the indicated concentrations etoposide or doxorubicin. Cytochrome c was precipitated from the culture medium (m) and the cellular extracts (c) with antibodies against the native molecule. The immunoprecipitated material was separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting. The quantity of cytochrome c was then determined by densitometric analysis. The graphs display the amount of cytochrome c in the culture medium relative to the total content of cytochrome c present in medium and cells. (B) Cytochrome c is released from cells as a soluble protein. Supernatants of Jurkat cells treated for 15 hours with staurosporine were centrifuged for 30 minutes at 10 000g or 100 000g and immunoblotted as described above. Open arrowheads indicate heavy chain and light chain of anticytochrome c antibody; closed arrowhead indicates cytochrome c.

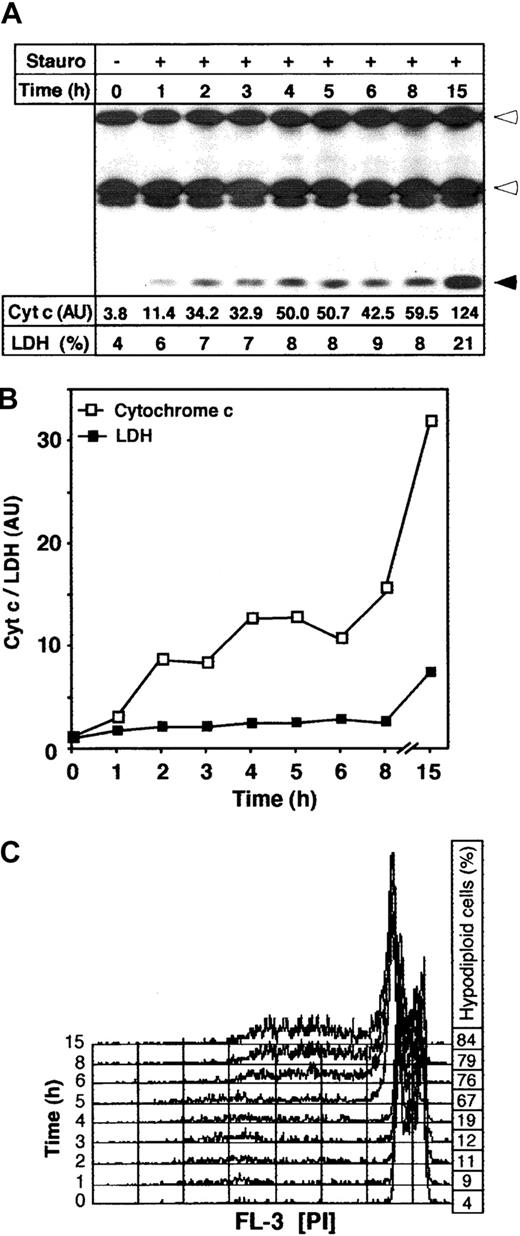

The release of cytochrome c from the cell was a rapid process. Already 1 hour after apoptosis induction with staurosporine, cytochrome c could be detected in the medium (Figure 2A). A parallel measurement of the activity of LDH, a cytoplasmic enzyme and clinical marker of cell damage, indicated that the release of LDH into supernatants from apoptotic cells occurred much later and was less pronounced than cytochrome c release. Only approximately 20% of total LDH was detected in the supernatants of apoptotic cells after 15 hours of staurosporine treatment (Figure 2A). To compare the kinetics of the release of cytochrome c and LDH, cytochrome c levels were further quantified by densitometric analysis (Figure 2A). A comparison of both events showed that the extracellular release of cytochrome c was stronger and occurred much earlier than the release of LDH (Figure 2B). The fast kinetics of cytochrome c release corresponded to a recent study demonstrating that the translocation of this molecule into cytosol is an all-or-nothing event that, once induced, is completed within a few minutes.13 Parallel to cytochrome c detection in the extracellular medium, the progression of apoptosis was monitored by flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 2C, formation of hypodiploid nuclei was not observed until 5 hours after apoptosis triggering. This agrees with observations that cytochrome c release into the cytosol precedes caspase activation and other morphologic changes of apoptosis including phosphatidylserine exposure, cell shrinkage, and membrane blebbing.13,17 20 Therefore, detection of cytochrome c in the extracellular medium can be regarded as an early and sensitive death indicator.

Time course of cytochrome c release on apoptosis induction.

Jurkat cells (1 × 106) were incubated with medium or staurosporine (Stauro, 2.5 μM) and harvested after the indicated time points. (A) Release of cytochrome c was determined by immunoprecipitation of the medium fractions and subsequent immunoblotting. Heavy and light chains of anticytochrome c antibody and cytochrome c are indicated by open and closed arrowheads, respectively. The LDH activity in the supernatant of apoptotic cells represents the percentage of total LDH activity in each sample. The cytochrome c content in the supernatant indicates the absolute densitometric values. (B) Relative kinetics of release of cytochrome c and LDH activity. To visualize the relative quantities of cytochrome c and LDH activity in the culture medium, the absolute densitometric values of cytochrome c and the percentage of released LDH from Figure 1A were divided by the control values (0 hours). (C) Apoptosis induction by staurosporine was assessed by flow cytometry. The histograms show measurements of hypodiploid DNA formation. The percentage of apoptotic hypodiploid cells is shown on the right.

Time course of cytochrome c release on apoptosis induction.

Jurkat cells (1 × 106) were incubated with medium or staurosporine (Stauro, 2.5 μM) and harvested after the indicated time points. (A) Release of cytochrome c was determined by immunoprecipitation of the medium fractions and subsequent immunoblotting. Heavy and light chains of anticytochrome c antibody and cytochrome c are indicated by open and closed arrowheads, respectively. The LDH activity in the supernatant of apoptotic cells represents the percentage of total LDH activity in each sample. The cytochrome c content in the supernatant indicates the absolute densitometric values. (B) Relative kinetics of release of cytochrome c and LDH activity. To visualize the relative quantities of cytochrome c and LDH activity in the culture medium, the absolute densitometric values of cytochrome c and the percentage of released LDH from Figure 1A were divided by the control values (0 hours). (C) Apoptosis induction by staurosporine was assessed by flow cytometry. The histograms show measurements of hypodiploid DNA formation. The percentage of apoptotic hypodiploid cells is shown on the right.

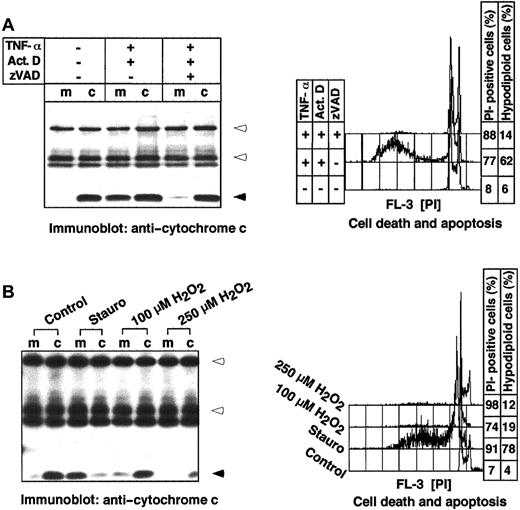

Because during necrotic cell death, contrary to apoptosis, marked morphologic changes of mitochondria are observed, we wanted to compare the degree of cytochrome c release in both types of cell death. To this end, 2 different death models were used: (1) The stimulation of L929 cells with TNF-α plus actinomycin D induces apoptosis, whereas the same stimuli in the presence of the broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk induce necrosis.21 Concomitant measurement of the DNA content and propidium iodide uptake confirmed these data. In the absence of zVAD-fmk, the cells underwent apoptosis as indicated by the formation of hypodiploid nuclei (Figure3A). In contrast, blocking the apoptotic pathway through caspase inhibition by zVAD-fmk resulted in necrosis, as shown by the increased uptake of propidium iodide in the absence of degraded DNA. Interestingly, cytochrome c was found only in the medium of apoptotic cells, whereas during necrosis it remained cellular (Figure 3A). Similar results were obtained in the second experimental system: (2) Here, necrosis was induced by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) incubation. H2O2at concentrations above 50 μM is known to block caspase activity by oxidizing the active center cysteine, and instead induces necrotic cell death by oxidative stress and membrane lipid damage.22Treatment of Jurkat T cells with 100 μM and 250 μM H2O2 induced necrotic death, as confirmed by propidium iodide uptake in the absence of hypodiploid nuclei formation (Figure 3B). Similar to the first approach (Figure 3A), no cytochrome c release into the extracellular medium was observed. The weaker cytochrome c signal in cells treated with 250 μM H2O2 was probably due to a partial oxidation of cytochrome c and the alteration of an epitope recognized by the antibody.

Cytochrome c release is an apoptosis-specific process.

Cytochrome c is not released during necrotic cell death in mouse L929 fibroblasts. L929 cells (3 × 106) were incubated with medium or with TNF-α (10 ng/mL) plus actinomycin D (Act D, 1 μg/mL) in the absence or presence of the caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk (100 μM) for 8 hours. (B) Cytochrome c is not released during necrotic cell death in human Jurkat cells. Cells (1 × 106) were cultured in normal growth medium (Control), or in the presence of staurosporine (Stauro, 2.5 μM) or the indicated concentrations of H2O2 for 18 hours. The release of cytochrome c was determined by immunoprecipitation of culture medium (m) and corresponding cellular extracts (c) and subsequent immunoblotting. Heavy and light chains of the anticytochrome c antibody and cytochrome c are indicated by open and closed arrowheads, respectively. Cell death was measured by propidium iodide uptake and apoptosis by flow cytometric detection of hypodiploid nuclei. The SDs were less than 9%.

Cytochrome c release is an apoptosis-specific process.

Cytochrome c is not released during necrotic cell death in mouse L929 fibroblasts. L929 cells (3 × 106) were incubated with medium or with TNF-α (10 ng/mL) plus actinomycin D (Act D, 1 μg/mL) in the absence or presence of the caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk (100 μM) for 8 hours. (B) Cytochrome c is not released during necrotic cell death in human Jurkat cells. Cells (1 × 106) were cultured in normal growth medium (Control), or in the presence of staurosporine (Stauro, 2.5 μM) or the indicated concentrations of H2O2 for 18 hours. The release of cytochrome c was determined by immunoprecipitation of culture medium (m) and corresponding cellular extracts (c) and subsequent immunoblotting. Heavy and light chains of the anticytochrome c antibody and cytochrome c are indicated by open and closed arrowheads, respectively. Cell death was measured by propidium iodide uptake and apoptosis by flow cytometric detection of hypodiploid nuclei. The SDs were less than 9%.

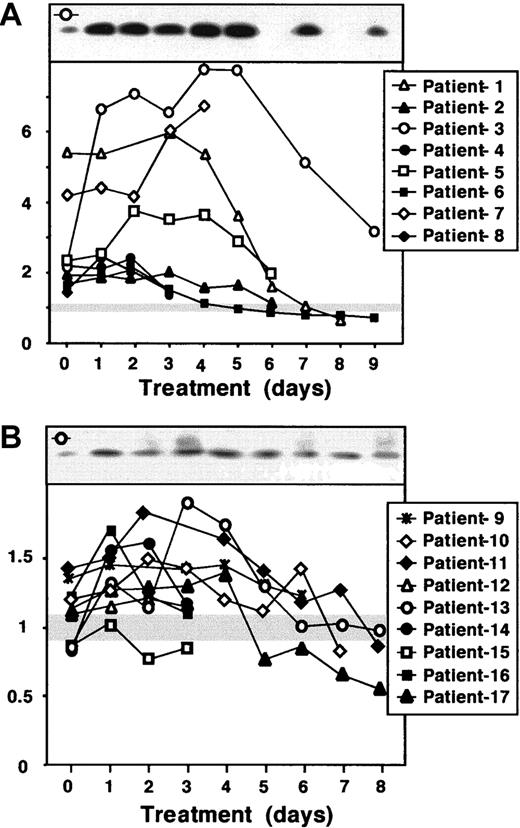

Because the release of cytochrome c could be induced by a variety of apoptotic stimuli, we postulated that it should be also detected in vivo, for instance during anticancer drug therapy. To examine this hypothesis we screened human sera from oncologic patients receiving combined chemotherapy. The serum cytochrome c levels were monitored from 17 patients hospitalized mostly due to hematologic malignancies and treated with various chemotherapy protocols (Table 1). For standardization, sera from 8 healthy control persons were included in the analysis, but did not show significant differences in cytochrome c levels (< 9%). The patients' samples were loosely categorized into those with strongly elevated (≥ 2-fold) cytochrome c levels compared to control donors (Figure 4A), and those with less altered levels of cytochrome c (Figure 4B) either before or during chemotherapy. Eight patients had serum cytochrome c levels exceeding at least twice the level of the controls in the course of the therapy. From this group, 4 patients were diagnosed with AML, 2 with NHL, and 1 each with HD and metastasizing breast cancer, respectively. In some of these patients the levels of cytochrome c became even 6- to 8-fold higher than the control values (Figure 4A). In contrast, some patients had initial serum cytochrome c levels similar to controls (Figure 4B). Almost half the patients from this group (n = 4) were diagnosed with NHL, 3 with AML, and 1 each with ALL and NSCLC, respectively. Serum cytochrome c increased in the course of the therapy in most of them, although the extent and kinetics of elevated cytochrome c was variable.

Detection of cytochrome c in serum of chemotherapy-treated cancer patients.

Sera (3 mL) obtained from different cancer patients (Table 1) before and during chemotherapy were precleared from residual immunoglobulins with protein G. Cytochrome c was immunoprecipitated and detected by Western blotting. A sample from a healthy control person was incorporated into each Western blot and served as an internal standard to normalize the data obtained from the different patients. The relative levels of cytochrome c in the sera were quantified by densitometric analysis and calculated as the ratio relative to the value of the control, which was set to 1. Day 0 indicates a sample taken before the start of the therapy. The first day of chemotherapy was considered as day 1; at day 1 the serum was withdrawn 8 to 12 hours after the start of infusion with chemotherapeutic drugs. The patients were loosely classified according to their serum cytochrome c levels. Panel A depicts patients with at least 2-fold elevated cytochrome c levels, and panel B patients with cytochrome c levels less than 2-fold increased in comparison to controls. Healthy control persons showed only low detectable levels of serum cytochrome c. The gray horizontal bar indicates the range of measured serum cytochrome c in the controls, which did not show marked interindividual differences (< 9%). The top panel of each graph shows a Western blot of a representative patient. The symbol in the left upper corner of each Western blot indicates the corresponding densitometric analysis.

Detection of cytochrome c in serum of chemotherapy-treated cancer patients.

Sera (3 mL) obtained from different cancer patients (Table 1) before and during chemotherapy were precleared from residual immunoglobulins with protein G. Cytochrome c was immunoprecipitated and detected by Western blotting. A sample from a healthy control person was incorporated into each Western blot and served as an internal standard to normalize the data obtained from the different patients. The relative levels of cytochrome c in the sera were quantified by densitometric analysis and calculated as the ratio relative to the value of the control, which was set to 1. Day 0 indicates a sample taken before the start of the therapy. The first day of chemotherapy was considered as day 1; at day 1 the serum was withdrawn 8 to 12 hours after the start of infusion with chemotherapeutic drugs. The patients were loosely classified according to their serum cytochrome c levels. Panel A depicts patients with at least 2-fold elevated cytochrome c levels, and panel B patients with cytochrome c levels less than 2-fold increased in comparison to controls. Healthy control persons showed only low detectable levels of serum cytochrome c. The gray horizontal bar indicates the range of measured serum cytochrome c in the controls, which did not show marked interindividual differences (< 9%). The top panel of each graph shows a Western blot of a representative patient. The symbol in the left upper corner of each Western blot indicates the corresponding densitometric analysis.

Thus, the majority of the monitored patients responded to chemotherapy with an increase of serum cytochrome c levels (Table 1). The increase of cytochrome c in the serum could be observed within a few hours after the onset of chemotherapy (data not shown). In most patients cytochrome c levels started to decrease later in the course of chemotherapy, reaching levels similar to or even lower than those in the controls (Figure 4). In a large number of patients the cytochrome c levels were already high before the start of the chemotherapy, which may indicate an increased cell turnover and augmented spontaneous apoptosis. Similar to cytochrome c, in most patients high serum levels of LDH were observed prior to therapy (Table 1). However, although LDH levels increased during therapy in 6 patients, its kinetics was different from that of cytochrome c (Table 1). This finding indicates that the release of cytochrome c and LDH activity reflects different (patho)physiologic processes. LDH, a cytosolic protein, is most likely released on cell lysis, eg, during necrosis. In contrast, cytochrome c needs to pass from mitochondria to the cytoplasm, before reaching extracellular compartment. Thus, based on our experimental data, we propose that serum LDH activity is more indicative of necrotic processes in vivo, whereas the release of cytochrome c characterizes apoptotic events.

So far, it has only been described that cytochrome c is released from the mitochondria to the cytosol. The exact mechanism of this key event is not understood. Several models including rupture of the outer mitochondrial membrane and permeability transition15 and the escape of cytochrome c through megachannels or pores formed by proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members have been proposed.7,9,10 It is possible that related mechanisms of externalization may be responsible for the release of cytochrome c into the extracellular medium. However, it is unlikely that cytochrome c is released by a nonspecific mechanism such as cell lysis, because a release of LDH occurred at later time points (Figure 2). It has been reported that the tripeptide glutathione is specifically extruded during apoptosis,23 although it is unlikely that cytochrome c, a 14.5-kd protein, is externalized by a related mechanism. In addition, there are several examples of proteins, such as HIV-Tat, thioredoxin, interleukin 1β and basic fibroblast growth factor, which lack a signal peptide and are exported by alternative pathways.24 For most of these proteins the mechanism of export is unclear. In some cases, proteins lacking a signal peptide can be released by exocytosis of preterminal endocytic vesicles and an ABC-related transport mechanism.24,25 It has been also found that death ligands, such as CD95L and TRAIL, are stored in microvesicles that may be released on cell activation and apoptosis.26 27 However, the fact that cytochrome c was recovered as a soluble protein after ultracentrifugation as well as in pharmacologic inhibitor experiments (data not shown) argues against this idea. Because the mechanism of the extracellular release of cytochrome c remains unknown, its physiologic relevance is also unclear. Current experiments therefore investigate whether extracellular cytochrome c exerts anti-inflammatory effects or is involved in the recognition of apoptotic cells by phagocytes or other physiologic processes.

In summary, we show that cytochrome c, the key regulator of apoptosome pathway, is released not only into cytoplasm, but moreover leaves the cell. This externalization of cytochrome c is an early and apoptosis-specific event, which occurs not only in experimental settings but also in vivo during chemotherapy of tumor patients. The kinetics of cytochrome c release differs from that of LDH indicating that both parameters are indicative for distinct physiologic processes. The noninvasive assessment of cytochrome c release may therefore provide a useful assay to detect apoptosis and to determine cell turnover and treatment efficacy in several clinical disorders.

The authors thank Dr W. Fiers (University of Ghent, Belgium) for the gift of TNF-α and the staff of the central laboratory of the University Clinic of Münster for the measurement of LDH activity.

Supported in part by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 293), the IZKF of the University of Münster, and the Deutsche Krebshilfe.

K.S.-O. and M.L. share equal senior authorship.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Marek Los, Department of Immunology and Cell Biology, University of Münster, Röntgenstrasse 21, D-48149 Münster, Germany; e-mail: los@uni-muenster.de.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal