Abstract

Protein ubiquitination is an important regulator of cytokine-activated signal transduction pathways and hematopoietic cell growth. Protein ubiquitination is controlled by the coordinate action of ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes and deubiquitinating enzymes. Recently a novel family of genes encoding growth-regulatory deubiquitinating enzymes (DUB-1 and DUB-2) has been identified.DUBs are immediate-early genes and are induced rapidly and transiently in response to cytokine stimuli. By means of polymerase chain reaction amplification with degenerate primers for theDUB-2 complementary DNA, 3 murine bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones that contain DUB gene sequences were isolated. One BAC contained a novel DUB gene(DUB-2A) with extensive homology to DUB-2. LikeDUB-1 and DUB-2, the DUB-2A gene consists of 2 exons. The predicted DUB-2A protein is highly related to other DUBs throughout the primary amino acid sequence, with a hypervariable region at its C-terminus. In vitro, DUB-2Ahad functional deubiquitinating activity; mutation of its conserved amino acid residues abolished this activity. The 5′ flanking sequence of the DUB-2A gene has a hematopoietic-specific functional enhancer sequence. It is proposed that there are at least 3 members of the DUB subfamily (DUB-1, DUB-2,and DUB-2A) and that different hematopoietic cytokines induce specific DUB genes, thereby initiating a cytokine-specific growth response.

Introduction

Protein ubiquitination controls many intracellular processes, including cell cycle progression.1,2transcriptional activation,3 and signal transduction4 (reviewed in Ciechanover5 and D'Andrea and Pellman6). Like protein phosphorylation, protein ubiquitination is dynamic, involving enzymes that add ubiquitin (ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes) and enzymes that remove ubiquitin (deubiquitinating enzymes). Considerable progress has been made in understanding ubiquitin conjugation and its role in regulating protein degradation. Recent studies have demonstrated that regulation also occurs at the level of deubiquitination. Deubiquitinating enzymes are cysteine proteases that specifically cleave ubiquitin from ubiquitin-conjugated protein substrates. Deubiquitinating enzymes have significant sequence diversity and may therefore have a broad range of substrate specificity.

There are 2 major families of deubiquitinating enzymes, the ubiquitin-processing proteases (ubp) family7-9 and the ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase (uch) family.10,11The ubp family and the uch family have also been referred to as the type 1 uch and type 2 uch families.12 Both ubps and uchs are cysteine proteases containing an active site cysteine, aspartate, and histidine residue. Ubps vary greatly in size and structural complexity, but all contain 6 characteristic conserved homology domains.13 Uchs, in contrast, include a group of small, closely related proteases that lack the 6 characteristic homology domains of the ubps.11

Little is known regarding the precise cellular function of ubps and uchs. For instance, despite the broad range and structural diversity of these enzymes, only a few specific candidate substrates have been identified.14-16 Also, whether these enzymes act exclusively on ubiquitinated substrates or on substrates with ubiquitinlike modifications, such as SUMO-117,18 and NEDD8,19 remains unknown. Recently, a distinct family of cysteine proteases, acting on SUMO-1–conjugated substrates, has been identified.20 Finally, the precise cellular level of action of these enzymes is unknown. Some deubiquitinating enzymes may act before the proteasome, thereby removing ubiquitin and rescuing a substrate protein from degradation.6 Other deubiquitinating enzymes may act as a component of the proteasome, thereby promoting the net degradation of a specific ubiquitinated substrate.21

Despite this lack of information regarding substrate specificity, substrate selection, and level of action, it is clear that some deubiquitinating enzymes exert distinct growth-regulatory activities or growth effects on cellular differentiation. The tre-2 oncoprotein, for example, is a deubiquitinating enzyme with transforming activity.8,22 The FAF protein is a ubp that regulatesDrosophila eye development.23 Other ubps, such as UBP324 and Drosophilaubp-64E,25 play an important role in transcriptional silencing.

We have recently identified a hematopoietic-specific growth-regulatory subfamily of ubps, referred to as DUBs.26,27 DUB-1 was originally cloned as an immediate-early gene induced by the cytokine interleukin-3 (IL-3). Several lines of evidence suggest that DUB-1 plays a growth-regulatory role in the cell. First, the expression of DUB-1 has the characteristics of an immediate-early gene. Following IL-3 stimulation, theDUB-1 messenger RNA (mRNA) is rapidly induced and is superinduced in the presence of cyclohexamide. Second, high-level expression of DUB-1 from an inducible promoter results in cell cycle arrest prior to S phase. This result suggests thatDUB-1 controls the ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis or the ubiquitination state of an important regulator at the G1/S transition of the cell cycle. Finally, the induction of DUB proteins may be a general feature of the response to cytokines. Another family member, DUB-2, is induced by IL-2.28

DUB proteins are highly related to each other, not only within the 6 characteristic ubp domains, but also throughout their protein sequence. One short peptide region within the C-terminal extension ofDUB family members shows remarkable sequence diversity. This “hypervariable region” may have a role in the recognition of specific substrates.28 A tandem repeat of DUBgenes maps to a region of murine chromosome 7,28suggesting that the DUB subfamily arose by tandem duplication of an ancestral DUB gene.

In the current study, we have cloned the complementary DNA (cDNA) and gene for a new member of the hematopoietic-specific DUBsubfamily of deubiquitinating enzymes. Because the new DUBis highly related to DUB-2, in terms of its sequence, genomic organization, and expression pattern, we have named the new gene DUB-2A. DUB-2A encodes a functional deubiquitinating enzyme, which is rapidly induced in response to cytokine stimulation of hematopoietic cells. A minimal catalytic domain in the N-terminal region of DUB-2A is necessary and sufficient for functional activity, and the carboxy-terminal region, which is hypervariable among DUBs, is not required for activity. Moreover, we propose that DUB-2A regulates cellular growth by controlling the ubiquitin-dependent degradation or the ubiquitination state of an unknown intracellular growth-regulatory protein.

Materials and methods

Cells and cell culture

Southern and Northern blot analyses

For Southern blots, genomic DNA (10 to 15 μg) was digested with the EcoRV, electrophoresed on 1% agarose gel, and blotted onto Duralon-UV membranes (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The 0.8-kilobase (kb) probe, generated from the digestion of the 15-kb genomic DUB-2 DNA with Kpn I and Hind III, purified from agarose gels (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA), was radiolabeled and hybridized for 2 hours to the membrane in a 65°C oven. Hybridized filters were washed at 65°C in 1 × sodium chloride/sodium acetate hybridization solution (SSC) and 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) for 15 minutes and washed again in 0.5 × SSC and 0.2% SDS for 15 minutes. For Northern blots, RNA samples (10 to 20 μg) were electrophoresed on denaturing formaldehyde gels and blotted onto Duralon-UV membranes. The 0.8-kb probe derived from 3′-UTR was radiolabeled and hybridized to the membrane as Southern blotting. Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for analysis of DUB-2A mRNA expression was performed as previously described.26

Isolation of the genomic DUB-2A gene and construction of luciferase reporter plasmids

The murine genomic library in pBeloBAC11 vector was screened by genomic PCR by means of 2 primers (Bam5′, GCGGATCCTTTGAAGAGGTCTTTGGAAA, and Xho3′, ATCTCGAGGTGTCCACAGGAGCCTGTGT) derived from theDUB-2 DNA sequence. By means of the same primers, genomic PCR products from 1 of the 3 positive bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones were generated and sequenced.

DUB-1 and DUB-2A enhancer elements were identified and subcloned into the PGL2Promoter plasmid (Promega, Madison, WI), which contains the simian virus SV40 basal promoter upstream of the luciferase reporter gene. The enhancer region of theDUB-2A gene corresponds to the minimal IL-3 response element of the murine DUB-1 gene (nucleotides −1528 to −1416), which has previously been described.29 30

Deubiquitination assay

A deubiquitination assay, based on the cleavage of ubiquitin–β-galactosidase (ub-β-gal) fusion proteins, has been described previously.8 A 1638–base pair (bp) fragment from the wild-type DUB-2A cDNA (corresponding to amino acids 1 to 545) and a cDNA containing a missense mutant form,DUB-2A (C60S [single-letter amino acid codes]), were generated by PCR and inserted, in frame, into pGEX-2TK (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NY), downstream of the glutathioneS-transferase (GST) coding element. Ub-Met-β-gal was expressed from a pACYC184-based plasmid. Plasmids were cotransfomed into MC1061 Escherichia coli. Plasmid-bearing E coli MC1061 cells were lysed and analyzed by immunoblotting with a rabbit anti–β-gal antiserum (Cappel, Durham, NC), a rabbit anti-GST antiserum (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA), and the ECL system (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom).

Transient transfection and transactivation experiments

All plasmid DNAs were purified with Qiagen columns. Transient transfections of Ba/F3 cells and luciferase reporter gene assays were performed as previously described,27 with the following modification. Ba/F3 cells were washed free of serum and IL-3 and cultured in plain RPMI for 2 hours. Afterwards, they were resuspended at 1 × 107 cells per 0.8 mL RPMI and transferred to an electroporation cuvette. Cells were incubated with 10 μg of the indicated luciferase reporter vector, along with 1 μg of a cytomegalovirus-promoter-driven β-galactosidase (β-gal) reporter gene construct to monitor transfection efficiencies. After electroporation with a Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) electroporator (350 V, 960 microfarads [μF]), cells were divided into 2 pools and either restimulated with 10 pM IL-3 for 4 hours or left untreated. Then, luciferase and β-galactosidase levels were assayed by, respectively, the Luciferase assay kit (Analytical Luminescence Laboratory, San Diego, CA) and the Galacto-Light Kit (Tropix, Bedford, MA) according to vendor specifications. Each luciferase reporter construct was tested at least 3 times by independent transfection.

Isolation of an enhancer sequence from the BAC clone containing theDUB-2A gene

A 1516–base pair fragment, corresponding to the promoter region of the DUB-2A gene, was amplified by PCR from the DUB-2A BAC clone. Primers used wereDUB1e1 (5′-CTAGTAAGGATATAACAGG-3′) and T14/CS (5′-CATTCAGGTAGCAGCTGTTGCC-3′). The amplified PCR product was subcloned into a pCR2.1-TOPO vector and sequenced. The 100-bp fragment derived from the promoter region was further subcloned into the pGL2Promoter.

Results

Identification and cloning of a novel DUB gene,DUB-2A

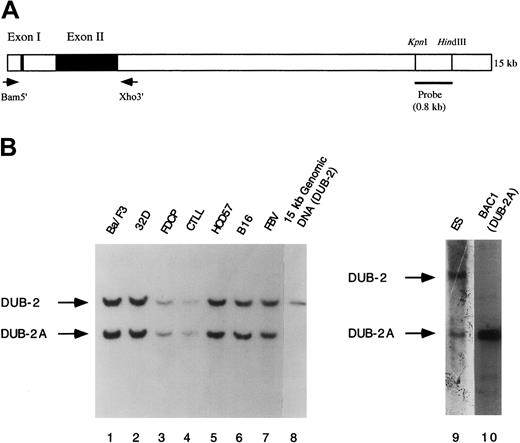

We have previously characterized a genomic clone of the murineDUB-2 gene28 (Figure1A). In an attempt to isolate additionalDUB-2 genomic clones with longer 5′ and 3′ genomic sequence, we screened a murine genomic BAC library, using PCR withDUB-2–specific primers (Figure 1A). We isolated 3 BAC clones that yielded a 1.5-kb PCR product, consistent with the presence of a DUB sequence. Two of the BAC clones (BAC2 and BAC3) contained the DUB-2 gene. An additional BAC clone (BAC1) contained a different DUB gene (DUB-2A), which was subjected to further analysis.

Identification of the murine

DUB-2 and DUB-2A genes by Southern blot analysis. (A) Schematic representation of theDUB-2 gene. The indicated primers were used to amplify theDUB-2 and DUB-2A genes from murine BAC clones by PCR. The indicated 800-bp probe was used for Southern blot analysis in panel B. (B) Genomic DNA from the indicated murine cell lines or BAC clones was restriction-digested with EcoRV, electrophoresed, blotted to nitrocellulose, and probed with the 32P-labeled probe. Lanes 1 to 7 contain EcoRV-digested genomic DNA from the indicated murine cell lines. Ba/F3 and 32D cells were derived from Balb/c mice. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte line (CTLL) cells were derived from C57BL mice. HCD57 cells were derived from National Institutes of Health (NIH) Swiss mice. B16 cells were derived from B16 mice. FVB cells were derived from FVB mice. ES cells were derived from 129SV mice. Lanes 8 and 10 contain digested DNA from either a DUB-2 genomic clone or a DUB-2A (BAC1) genomic clone, respectively. The band corresponding to the DUB-2 and DUB-2A genes is indicated.

Identification of the murine

DUB-2 and DUB-2A genes by Southern blot analysis. (A) Schematic representation of theDUB-2 gene. The indicated primers were used to amplify theDUB-2 and DUB-2A genes from murine BAC clones by PCR. The indicated 800-bp probe was used for Southern blot analysis in panel B. (B) Genomic DNA from the indicated murine cell lines or BAC clones was restriction-digested with EcoRV, electrophoresed, blotted to nitrocellulose, and probed with the 32P-labeled probe. Lanes 1 to 7 contain EcoRV-digested genomic DNA from the indicated murine cell lines. Ba/F3 and 32D cells were derived from Balb/c mice. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte line (CTLL) cells were derived from C57BL mice. HCD57 cells were derived from National Institutes of Health (NIH) Swiss mice. B16 cells were derived from B16 mice. FVB cells were derived from FVB mice. ES cells were derived from 129SV mice. Lanes 8 and 10 contain digested DNA from either a DUB-2 genomic clone or a DUB-2A (BAC1) genomic clone, respectively. The band corresponding to the DUB-2 and DUB-2A genes is indicated.

To distinguish the new DUB gene from DUB-2, the BAC1 clone was analyzed by Southern blot analysis (Figure 1B). In parallel, we analyzed restriction enzyme–digested genomic DNA samples from multiple murine cell lines, corresponding to 6 independent strains of mice (lanes 1 through 7). We also analyzed genomic DNA from aDUB-2 genomic clone (lane 8). For analysis, we used a32P-labeled DNA probe from the indicated region downstream of the DUB-2 gene (Figure 1A). This labeled probe identified 2 distinct bands in genomic DNA from all mouse species tested (Figure1B, lanes 1 through 7). The genomic DUB-2 clone yielded the upper band (lane 8), but the genomic DUB-2A clone (BAC1) yielded the lower band (lane 10). Taken together, these results demonstrate that DUB-2 and DUB-2A are distinct genes found in the genome of multiple mouse strains.

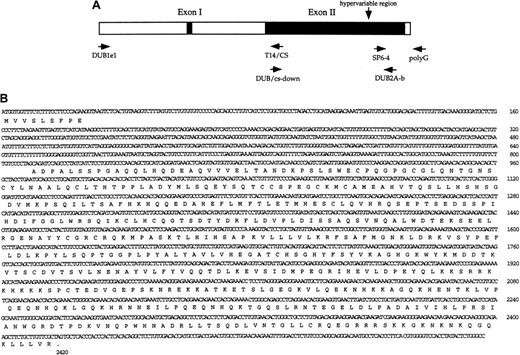

The structure of the genomic DUB-2A gene was further examined by PCR of various regions of the BAC1 clone (Figure2B). Distinct regions of theDUB-2A gene, including the 5′ and 3′ genomic sequences, were amplified by PCR with the indicated oligonucleotide primer pairs (Figure 2A). Sequencing of these amplified PCR products indicated that the DUB-2A gene is composed of 2 exons and 1 intron (Figure2B) and therefore has a structural organization identical to that of the DUB-2 gene.28 The DUB-2A gene is predicted to encode a protein of 545 amino acids. Exon 1 encodes the 9 amino acid amino terminal region of DUB-2A, and exon 2 encodes amino acids 10 through 545. The single intron is 792 bp. The sequence of the intron-exon junction conforms to a consensus sequence for a eukaryotic splice site. A region of the DUB-2A genomic clone, 5′ to the ATG translation start site, contains a stop codon.

Characterization of the

DUB-2A gene. (A) Schematic representation of theDUB-2A gene. Primer pairs used for genomic PCR of the 5′ region, open reading frame (ORF) region, and 3′ region are indicated. (B) Nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequence for theDUB-2A gene. The gene contains 2 exons, similar to the genomic structure of DUB-1 andDUB-2.25 26 The sequences of theDUB-2A gene and cDNA have been submitted to GenBank (accession number 407172).

Characterization of the

DUB-2A gene. (A) Schematic representation of theDUB-2A gene. Primer pairs used for genomic PCR of the 5′ region, open reading frame (ORF) region, and 3′ region are indicated. (B) Nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequence for theDUB-2A gene. The gene contains 2 exons, similar to the genomic structure of DUB-1 andDUB-2.25 26 The sequences of theDUB-2A gene and cDNA have been submitted to GenBank (accession number 407172).

We next compared the predicted amino acid sequence of DUB-2A with the previously cloned DUB-1 and DUB-2 proteins28 (Figure3). DUB-2A has 95% amino acid identity with DUB-2 and 86% amino acid identity with DUB-1. The DUB-2A protein contains the highly conserved C (cystein) and H (histidine) domains of other known ubps.8 13 In addition, there is a highly conserved D residue at DUB-2A, position 133. These domains are likely to form the enzyme's active site. The putative active site nucleophile of DUB-2A is a cysteine residue (C60) in the C domain. In addition, DUB-2A contains a lysine-rich region (amino acids 74 to 84) and a short hypervariable region (amino acids 431 to 450) in which the DUB-2 sequence diverges from DUB-1 and DUB-2 (Figure 3). The hypervariable region of DUB-2A contains the sequence VPQEQNHQKLGQKHRNNEIL, extending from amino acid residue 432 to 451.

Amino acid alignment of DUB-1, DUB-2, and DUB-2A proteins.

The predicted amino acid sequences of DUB-1, DUB-2, and DUB-2A are shown. Boxed residues are different among the various DUB proteins. The hypervariable region of the DUB-2A protein extends from amino acids 432 through 451. On the basis of this alignment, DUB-2A has a 95% identity with DUB-2 and an 86% identity with DUB-1.

Amino acid alignment of DUB-1, DUB-2, and DUB-2A proteins.

The predicted amino acid sequences of DUB-1, DUB-2, and DUB-2A are shown. Boxed residues are different among the various DUB proteins. The hypervariable region of the DUB-2A protein extends from amino acids 432 through 451. On the basis of this alignment, DUB-2A has a 95% identity with DUB-2 and an 86% identity with DUB-1.

DUB-1, DUB-2, and DUB-2A proteins are more related to each other than to other members of the ubp family of deubiquitinating enzymes. For instance, DUB-1, DUB-2, and DUB-2A contain sequence similarity not only in the conserved C and H domains (common to all ubps), but also throughout the carboxy-terminal region of the proteins. Taken together, these results further support the existence of a DUB subfamily of ubps, as previously described.28

Expression pattern of the DUB-2A mRNA

We next used DUB-2A-specific PCR primers to determine the expression pattern of the DUB-2A mRNA (Figure4). Using PCR from genomic DUBclones (indicated in Figure 2A), we demonstrated that one primer pair (exon 1 and DUB-2A-b) specifically amplifies theDUB-2A sequence (lane 1) but does not amplify the highly related DUB-2 sequence (lane 2). We used these primer pairs and RT-PCR to examine the expression of the DUB-2A mRNA in various murine cell lines (lanes 3 through 7). The DUB-2AmRNA was expressed in CTLL (T cells), 32D (myeloid cells), and ES cells but was not expressed in F9 (carcinoma cells) or NIH3T3 (fibroblasts). The DUB-2A mRNA was also detected in Ba/F3 cells (data not shown). The identification of the cDNA isolated from CTLL, 32D, and ES cells was confirmed as DUB-2A by direct DNA sequencing of the amplified cDNA product (data not shown). As a control, degenerate DUB primers, capable of amplifying otherDUB family members, yielded an amplified RT-PCR product from all murine cell lines tested. Taken together, these data demonstrate that DUB-2A is expressed primarily in hematopoietic cells, a pattern that is similar but not identical to the expression pattern ofDUB-2.

Expression pattern of the

DUB-2A mRNA. Genomic PCR products and RT-PCR products were generated from the indicated cell lines, by means of degenerate primers and DUB-2A-specific primers. The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel, which was stained with ethidium bromide. The DUB-2A mRNA was detected by RT-PCR in several murine cell lines. including CTLL (T cells), 32D (myeloid cells), and ES cells, but not in murine F9 carcinoma cell lines or NIH3T3 fibroblasts. A DUB mRNA was detected by RT-PCR from all cell lines when degenerate DUB primers were used (lanes 3 though 7).

Expression pattern of the

DUB-2A mRNA. Genomic PCR products and RT-PCR products were generated from the indicated cell lines, by means of degenerate primers and DUB-2A-specific primers. The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel, which was stained with ethidium bromide. The DUB-2A mRNA was detected by RT-PCR in several murine cell lines. including CTLL (T cells), 32D (myeloid cells), and ES cells, but not in murine F9 carcinoma cell lines or NIH3T3 fibroblasts. A DUB mRNA was detected by RT-PCR from all cell lines when degenerate DUB primers were used (lanes 3 though 7).

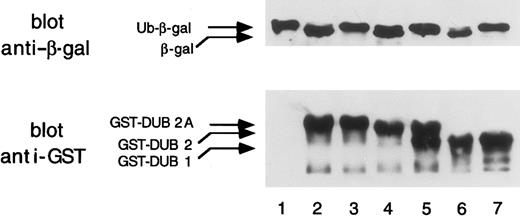

The DUB-2A gene encodes a functional deubiquitinating enzyme

To determine whether DUB-2A has deubiquitinating activity, we expressed DUB-2A as a GST fusion protein (Figure 5). The open reading frame ofDUB-2A was subcloned into the bacterial expression vector pGEX. The pGEX–DUB-2A was cotransformed into E coli (MC1061) with a plasmid encoding Ub-Met-β-gal, in which ubiquitin is fused to the NH2-terminus of β-galactosidase. As shown by immunoblot analysis, a cDNA clone encoding GST–DUB-2A fusion protein resulted in cleavage of Ub-Met-β-gal (lane 2) to an extent comparable to that observed with GST–DUB-1 (lane 6) and GST–DUB-2 (lane 4). As a control, cells transformed with the pBlueScript vector with a nontranscribed DUB-2A insert (lane 1) or with the pGEX vector (data not shown) failed to cleave Ub-Met-β-gal. A mutantDUB-2A polypeptide, containing a C60S mutation, was unable to cleave the Ub-Met-β-gal substrate (lane 3).

DUB-2A is a functional deubiquitinating enzyme.

The upper panel shows the deubiquitination of the ubiquitin-β-galactosidase (Ub-Met-β-gal) fusion protein by various GST-DUB proteins coexpressed in bacteria. A Western blot using anti–β-gal antiserum is shown. Coexpressed plasmids were pBlueScript–DUB-2A(DUB-2A is not expressed) (lane 1); pGEX–DUB-2A(lane 2); pGEX–DUB-2A (C60S) (lane 3); pGEX–DUB-2 (lane 4); pGEX–DUB-2 (C60S) (lane 5); pGEX–DUB-1 (lane 6); and pGEX–DUB-1 (C60S) (lane 7). In the lower panel, GST-DUB fusion proteins were analyzed by an immunoblot with an anti-GST monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). E coli extracts were prepared from bacteria transformed with cDNAs encoding no GST fusion protein (empty vector) (lane 1); GST–DUB-2A (lane 2); GST–DUB-2A (C60S) (lane 3); GST–DUB-2 (lane 4); GST–DUB-2 (C60S) (lane 5); GST–DUB-1 (lane 6); and GST–DUB-1 (C60S) (lane 7). The lower band of the doublet in lane 5 is a degradation product of GST–DUB-2(C60S).

DUB-2A is a functional deubiquitinating enzyme.

The upper panel shows the deubiquitination of the ubiquitin-β-galactosidase (Ub-Met-β-gal) fusion protein by various GST-DUB proteins coexpressed in bacteria. A Western blot using anti–β-gal antiserum is shown. Coexpressed plasmids were pBlueScript–DUB-2A(DUB-2A is not expressed) (lane 1); pGEX–DUB-2A(lane 2); pGEX–DUB-2A (C60S) (lane 3); pGEX–DUB-2 (lane 4); pGEX–DUB-2 (C60S) (lane 5); pGEX–DUB-1 (lane 6); and pGEX–DUB-1 (C60S) (lane 7). In the lower panel, GST-DUB fusion proteins were analyzed by an immunoblot with an anti-GST monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). E coli extracts were prepared from bacteria transformed with cDNAs encoding no GST fusion protein (empty vector) (lane 1); GST–DUB-2A (lane 2); GST–DUB-2A (C60S) (lane 3); GST–DUB-2 (lane 4); GST–DUB-2 (C60S) (lane 5); GST–DUB-1 (lane 6); and GST–DUB-1 (C60S) (lane 7). The lower band of the doublet in lane 5 is a degradation product of GST–DUB-2(C60S).

Taken together, these results demonstrate that DUB-2A has deubiquitinating enzyme activity and that C60 is critical for its thiol protease activity. An anti-GST immunoblot confirmed that the GST–DUB-1, GST–DUB-2, and GST–DUB-2A proteins were synthesized at comparable levels (Figure 5, lower blot). The difference in sizes of the DUB-1, DUB-2, and DUB-2A GST fusion proteins reflects the difference in size of these full-length DUB enzymes. Expression of full-length wild-type DUB proteins in transfected COS cells reveals that DUB-1, DUB-2, and DUB-2A are 59 kd, 62 kd, and 64 kd, respectively (data not shown).

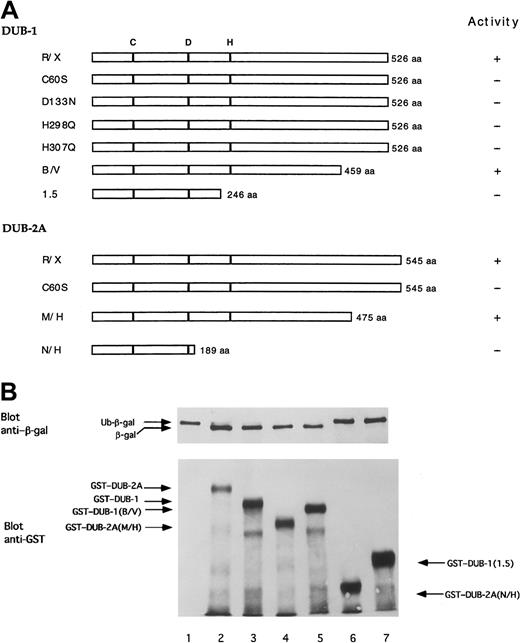

The carboxy-terminal region of DUB-2A is not required for enzymatic activity

As previously described, the amino terminal region ofDUB-1, DUB-2, and DUB-2A contains a putative catalytic region, consisting of C and H domains. The carboxy-terminal region contains a hypervariable region that may not be required for functional activity and that may confer substrate specificity. In order to determine the structural requirements ofDUB-mediated deubiquitinating activity, we next generated a series of DUB-1 and DUB-2A mutant polypeptides (Figure 6A) and synthesized these as GST-fusion proteins in E coli (Figure 6B). The mutantDUB polypeptides displayed differential activities in cleaving Ub-β-galactosidase in the E coli–based cotransformation assay. The C60 residue was required for deubiquitinating activity. In addition, mutations of the indicated D or H residue resulted in loss of activity, suggesting that these residues also play a critical role in the catalytic core of the enzyme. The carboxy-terminal 67 amino acids of DUB-1 (B/V mutant) and the carboxy-terminal 70 amino acids of DUB-2A (M/H mutant) were not required for deubiquitinating activity. Taken together, these data demonstrate that the core catalytic domain of DUB-1 andDUB-2A is sufficient for deubiquitinating activity.

The carboxy-terminus of DUB enzymes is not required for enzymatic activity.

(A) Schematic representation of DUB-1 and DUB-2A,and mutant forms. aa indicates amino acids. (B) Deubiquitination of ubiquitin-β-galactosidase (Ub-Met-β-gal) fusion protein expressed in bacteria. The upper panel is an immuoblot using anti–β-gal antiserum. Coexpressed plasmids were pBlueScript empty vector (lane 1); pBlueScript–DUB-2A (lane 2); pGEX–DUB-1 (lane 3); pGEX–DUB-2A (M/H) (lane 4); pGEX–DUB-1 (B/V) (lane 5); pGEX–DUB-2A(N/H) (lane 6); and pGEX–DUB-1 (1.5) (lane 7). The Ub-Met-β-gal fusion protein substrate was not cleaved in lanes 1, 6, and 7. The lower panel is an immunoblot using an anti-GST monoclonal antibody. In addtion to the full-length GST-fusion proteins, partial degradation products are also observed in lanes 2 through 7.

The carboxy-terminus of DUB enzymes is not required for enzymatic activity.

(A) Schematic representation of DUB-1 and DUB-2A,and mutant forms. aa indicates amino acids. (B) Deubiquitination of ubiquitin-β-galactosidase (Ub-Met-β-gal) fusion protein expressed in bacteria. The upper panel is an immuoblot using anti–β-gal antiserum. Coexpressed plasmids were pBlueScript empty vector (lane 1); pBlueScript–DUB-2A (lane 2); pGEX–DUB-1 (lane 3); pGEX–DUB-2A (M/H) (lane 4); pGEX–DUB-1 (B/V) (lane 5); pGEX–DUB-2A(N/H) (lane 6); and pGEX–DUB-1 (1.5) (lane 7). The Ub-Met-β-gal fusion protein substrate was not cleaved in lanes 1, 6, and 7. The lower panel is an immunoblot using an anti-GST monoclonal antibody. In addtion to the full-length GST-fusion proteins, partial degradation products are also observed in lanes 2 through 7.

The DUB-2A gene contains a cytokine-inducible enhancer element

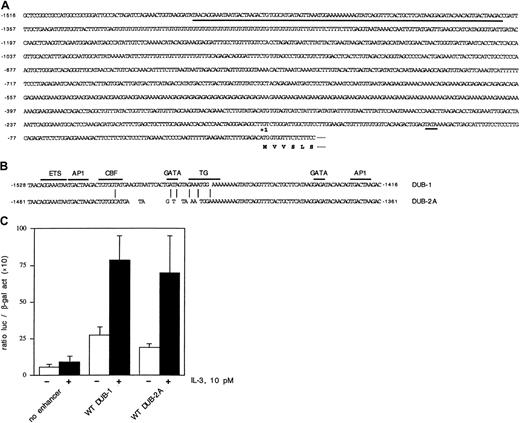

We have previously identified a cytokine-response enhancer element of the murine DUB-1 gene.27 This minimal enhancer element of DUB-1 is 112 bp in size and contains anets site, 2 AP-1 sites, and 2 GATA sites. The enhancer is located approximately 1500 bp 5′ to the ATG translational start site ofDUB-1. In an attempt to identify an enhancer region of theDUB-2A gene, we compared the 5′ sequences ofDUB-1 and DUB-2A, within the region of theDUB-1 enhancer element. The complete 5′ region of theDUB-2A gene is shown (Figure7A). A comparison of the DUB-1enhancer with the corresponding region of the DUB-2A gene is also shown (Figure 7B). Interestingly, there is considerable base-pair identity in this region of DUB-1 and DUB-2A,suggesting conserved enhancer functional activity. TheDUB-2A 5′ region contains conserved ets, AP1, and GATA sequences.

identification and functional analysis of the cytokine-inducible enhancer of the

DUB-2 gene. (A) Nucleotide sequence of theDUB-2A promoter. A putative TATA box (position −104) is indicated with a short underline. A 100-bp enhancer element is indicated with a long underline. In addition, a purine-rich microsatellite repeat is found between positions −560 and −385. (B) Comparison of the minimal enhancer regions of DUB-1 andDUB-2A. These enhancer regions contain an ETS protein consensus sequence, 2 AP1 sites, and 3′GATA site. A CBF site, a 5′GATA site, and a TG protein–binding site are found only in DUB-1,as indicated. (C) Luciferase activity was assayed in Ba/F3 cells transfected with the indicated constructs. The cells were starved and restimulated with no growth factor (■) or 10 pM IL-3 (▪). Luciferase assays were performed after 8 hours.

identification and functional analysis of the cytokine-inducible enhancer of the

DUB-2 gene. (A) Nucleotide sequence of theDUB-2A promoter. A putative TATA box (position −104) is indicated with a short underline. A 100-bp enhancer element is indicated with a long underline. In addition, a purine-rich microsatellite repeat is found between positions −560 and −385. (B) Comparison of the minimal enhancer regions of DUB-1 andDUB-2A. These enhancer regions contain an ETS protein consensus sequence, 2 AP1 sites, and 3′GATA site. A CBF site, a 5′GATA site, and a TG protein–binding site are found only in DUB-1,as indicated. (C) Luciferase activity was assayed in Ba/F3 cells transfected with the indicated constructs. The cells were starved and restimulated with no growth factor (■) or 10 pM IL-3 (▪). Luciferase assays were performed after 8 hours.

To assess the putative enhancer activity of the DUB-2Aregion, we next performed transfection assays in the murine hematopoietic pro-B lymphocyte cell line, Ba/F3 (Figure 7C). Ba/F3 cells are dependent on murine IL-3 for growth and survival. Ba/F3 cells were transiently transfected with various reporter constructs, and IL-3–induced DUB-1-luc and DUB-2A-luc activity were measured. The DUB-2A sequence, shown in Figure 7B, had an enhancer activity that was comparable to the activity of the knownDUB-1 enhancer.27 Taken together, these data further support the notion that DUBs are cytokine-inducible, immediate-early gene products expressed in hematopoietic cells.

Discussion

We have previously described a family of hematopoietic-specific, cytokine-inducible immediate-early genes encoding growth-regulatory deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs).28,DUB mRNA is induced rapidly by cytokines, and this is followed by a rapid decline. DUB induction requires the activation of a cytokine receptor and a Janus kinase (JAK).29 Sustained overexpression of DUB mRNA results in cell cycle arrest,26 suggesting that these enzymes regulate cell growth by controlling the ubiquitin-dependent degradation or the ubiquitination state of a critical intracellular substrate. Several cellular proteins involved in hematopoietic cell growth, including cytokine receptors, cbl, and cyclin/cdk inhibitors, are ubiquitinated and are potential physiologic substrates of DUB activity.

In the current study, we have identified a novel DUB enzyme, DUB-2A, which is another member of the DUB subfamily of deubiquitinating enzymes. DUB-2A is highly related to DUB-2,containing the same 2 exon genomic structure and encoding an enzyme of remarkable similarity (95% amino acid identity with DUB-2).DUB-2A is a discrete gene, however, and not an allele of theDUB-2 gene. For instance, both DUB-2 andDUB-2A genes are found in 6 independent strains of inbred mice.

Interestingly, DUB-2A differs from DUB-2 andDUB-1 in the carboxy-terminal hypervariable region, further suggesting that this region of the DUB enzyme regulates substrate specificity. For instance, this region may determine specific binding partner proteins of the various DUB enzymes. The existence of hypervariable regions outside of a core catalytic domain is also a feature of regulatory kinase and phosphatase enzyme families.

The DUB genes map to a region of murine chromosome 7 that contains a head-to-tail repeat of DUB genes.28This tandem repeat array suggests that the DUB genes arose by the tandem duplication of an ancestral DUB gene. While the tandem repeat length is unknown, recent evidence suggests a relatively short amplified unit. For instance, one of our murine BAC clones (120 kb) contains 2 complete DUB genes, suggesting that the amplified unit is less than 120 kb (K.-H.B., unpublished observation, December 2000). Other studies have recently identified a 4.7-kb highly repeated motif that has homology to the murine DUB genes.31 32

According to RT-PCR analysis (Figure 4) and Northern blot analysis (data not shown), the DUB-2A mRNA is expressed primarily in hematopoietic cells. This is similar to the expression pattern of theDUB-2 mRNA. Interestingly, a highly related DUBmRNA (not DUB-2A) is expressed in some nonhematopoietic cell lines, such as ES cells and 3T3 fibroblasts (Figure 4), suggesting thatDUB mRNA induction is a common feature of growth responses in other cell types as well.

While the function of the DUB-2A cDNA remains unknown, several features of DUB-2A suggest that it plays a role in hematopoietic cell growth control. First, the temporal expression of the DUB-2A gene is precisely regulated. TheDUB-2A mRNA has a cytokine-inducible immediate-early pattern of expression and a short half-life. Second, the DUB-2A mRNA is expressed in a precise, hematopoietic-specific pattern, suggesting that it regulates growth and differentiation of a specific subset of cellular lineages.

Several recent studies suggest that hematopoietic cell growth is regulated by ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of critical proteins involved in cytokine signaling pathways. First, cytokine receptors have been shown to undergo ubiquitin-dependent internalization and turnover.4,33 Second, recent evidence suggests that the mitogenic signaling protein, signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1), is regulated, at least in part, by ubiquitin-dependent degradation.34 Inhibition of proteasome activity also modulates signaling by the JAK/STAT pathway.35,36 Third, other hematopoietic signaling proteins, such as cbl37 and CIS,38 are thought to be directly or indirectly modulated by the ubiquitin pathway. Recent studies have shown that the hematopoietic transforming protein cbl has a Ring Finger domain and is a functional E3 ubiquitin ligase.39 Whether DUB enzymes regulate the ubiquitin-dependent degradation or the ubiquitination state of any of these hematopoietic protein substrates, leading to modulation of cellular growth, remains to be determined.

We thank members of the D'Andrea laboratory for helpful discussions and Barbara Keane for preparation of the manuscript.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants RO1 DK 43889 and PO1 DK 50654.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Alan D. D'Andrea, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Department of Pediatric Oncology, Harvard Medical School, 44 Binney St, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail: alan_dandrea@dfci.harvard.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal