Abstract

Hematopoietic fate maps in the developing mouse embryo remain imprecise. Definitive, adult-type hematopoiesis first appears in the fetal liver, then progresses to the spleen and bone marrow. Clonogenic common lymphoid progenitors and clonogenic common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) in adult mouse bone marrow that give rise to all lymphoid and myeloid lineages, respectively, have recently been identified. Here it is shown that myelopoiesis in the fetal liver similarly proceeds through a CMP equivalent. Fetal liver CMPs give rise to megakaryocyte–erythrocyte-restricted progenitors (MEPs) and granulocyte–monocyte-restricted progenitors (GMPs) that can also be prospectively isolated by cell surface phenotype. MEPs and GMPs generate mutually exclusive cell types in clonogenic colony assays and in transplantation experiments, suggesting that the lineage restriction observed within each progenitor subset is absolute under normal conditions. Purified progenitor populations were used to analyze expression profiles of various hematopoiesis-related genes. Expression patterns closely matched those of the adult counterpart populations. These results suggest that adult hematopoietic hierarchies are determined early in the development of the definitive immune system and suggest that the molecular mechanisms underlying cell fate decisions within the myeloerythroid lineages are conserved from embryo to adult.

Introduction

The genesis of the mammalian immune system has best been studied in the mouse, where hematopoiesis occurs through a stepwise process that begins in the yolk sac (YS) on embryonic day 7 (E7).1 Only primitive erythropoiesis is evident in this organ, which is characterized by the production of erythrocytes with unextruded nuclei and expression of embryonic globin genes.2 Hematopoiesis then appears in the aorta-gonad-mesonephros (AGM) region of the para-aortic splanchnopleura in the developing mouse embryo from E8 to E10, after which the fetal liver (FL) becomes the major site of embryonic blood production from approximately E12 to birth.2 Although culture and transplantation experiments have shown that both the YS1,3and AGM4,5 regions contain multipotent hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), definitive, multi-lineage hematopoiesis does not occur until the FL becomes the predominant hematopoietic organ.2This suggests that environmental cues may restrict and specify the cell fate determinations of HSCs. Cellular transplants of identical hematopoietic progenitors clearly show that differing environments can lead to different cell fates,1,3 6 suggesting that local niches specify lineage determination. Alternatively, hematopoietic precursors may be genetically distinct among the shifting sites of hematopoiesis in the developing immune system.

HSCs capable of long-term, multilineage reconstitution are prospectively isolatable from murine FL using cell surface marker profiles roughly equivalent to those of adult HSCs.7FL-HSCs, however, show several phenotypic and functional differences when compared to their adult counterparts. Phenotypically, FL-HSCs express AA4.18 and Mac-17 cell surface proteins, whereas adult HSCs do not. Functionally, FL-HSCs show much higher rates of proliferation and more rapid and robust reconstitution ability than adult HSCs.9-12 FL-HSCs also have differing cell fate potentials than adult HSCs. For example, early FL-HSCs give rise to Vγ3+ and Vγ4+ T cells in fetal thymic cultures13 and can reconstitute B-1a lymphocytes.14 Adult HSCs lack these differentiation capacities. These data suggest that intrinsic differences exist in cell fate potentials between fetal and adult hematopoietic progenitors.

Adult hematopoiesis takes place in bone marrow (BM) and occurs through a hierarchy of defined, lineage-restricted progenitors that are isolatable by cell surface phenotype. Common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) are clonogenic precursors of T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, and natural killer cells,15 whereas common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) give rise to all myeloerythroid lineages.16 CMPs are clonogenic precursors of megakaryocyte–erythrocyte-restricted progenitors (MEPs) and granulocyte–monocyte-restricted progenitors (GMPs) that respectively generate either platelets and red blood cells or granulocytes and monocytes.16 Taken together, these populations appear to represent the major pathways of blood cell development in adult BM.

In this study, we sought to determine whether the hematopoietic hierarchies of adult hematopoiesis are present in the first site of definitive hematopoiesis. We therefore searched for counterparts of adult CMPs, MEPs, and GMPs in the developing FL. We show, through the use of multiparameter flow cytometry and clonal assessment of progenitor potentials, that the lineage relationships of the adult hematopoietic system are determined early in development. Prospectively isolated CMP, MEP, and GMP counterparts from FL show transcriptional profiles nearly identical to their adult homologues, suggesting that the molecular foundations of adult lineal hierarchies are established after the development of the definitive immune system. We also report that, despite the general similarities between FL and BM fate maps, significant differences in proliferative capacity, colony-forming activity, and differentiation fidelity exist between progenitors in these 2 locations. These findings highlight the importance of prospective identification of progenitor populations for a more precise understanding of their biology.

Materials and methods

Mouse strains

The congenic strains of mice, C57Bl/Ka-Thy1.1 (CD45.2) and C57Bl/Ka-Thy1.1-CD45.1, were used as described.17 Timed pregnancies were used to generate embryos; all assays were performed on E14.5 FL cells, as in our previous studies of FL HSCs7 and FL CLP counterparts.74 All animals were maintained in Stanford University's Research Animal Facility in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Cell staining and sorting

For myeloid progenitor experiments, fetal liver cells were stained with biotinylated antibodies specific for the following lineage markers: CD3 (KT31.1), CD4 (GK1.5), CD5 (53.7.3), CD8 (53-6.7), B220 (6B2), CD19 (1D3), IgM (R6-60.2, Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), and TER119. Biotinylated IL-7Rα (A7R34) and AA4.1 antibodies were added to this cocktail to exclude FL CLPs and HSCs, respectively. Lin+ IL-7Rα+ AA4.1+ cells were partially removed with sheep anti–rat IgG–conjugated magnetic beads (Dynabeads M-450; Dynal AS, Oslo, Norway), and the remaining cells were stained with streptavidin-RED670 (Gibco BRL, Bethesda, MD). Cells were stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-FcγR (2.4G2), fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated CD34 (RAM34; Pharmingen), Texas Red–conjugated anti–Sca-1 (E13-161-7), and antigen presenting cell-conjugated anti–c-Kit (2B8) monoclonal antibodies.

Fetal liver HSCs were stained as sorted as described.7 All cell populations were sorted or analyzed using a highly modified triple laser (488-nm argon laser, 599-nm dye laser, and UV laser) FACS Vantage (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, Mountain View, CA). Progenitors were purified by sorting and re-sorting to obtain precise numbers of cells that were essentially pure for the indicated surface marker phenotype. In limiting-dilution assays and single-cell clonogenic assays, the re-sort was performed by using a carefully calibrated automatic cell deposition unit system (Becton Dickinson). This system deposited a specific number of purified cells onto either methylcellulose medium or OP9 stromal cell cultures in 96-well or 24-well plates, respectively, as previously described.16

In vivo and in vitro assays to determine differentiation potential of progenitors

For reconstitution assays, purified progenitors were injected into the retro-orbital venous sinus of either lethally irradiated (9.5 Gy delivered in a split dose) or sublethally irradiated (4.75 Gy single dose) congenic mice (differing only at the CD45 allele). Host-type whole BM cells (2-5 × 105) were co-injected into lethally irradiated recipients for radioprotection. Intrathymic injections were performed by directly injecting cells into thymi of mice that had been irradiated (6 Gy) as described previously.15,17 CFU-S assays were performed with 100 to 500 double-sorted progenitors per mouse as previously described.18

To support the formation of myeloid colonies, progenitors were cultured in Methocult M3434 or H4100 methylcellulose media (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% bovine serum albumin, 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 10% FL-conditioned medium. Cytokines such as mouse SLF (20 ng/mL; R&D Systems), mouse IL-3 (30 ng/mL; Genzyme, Cambridge, MA), mouse IL-11 (10 ng/mL; R&D Systems), mouse GM-CSF (10 ng/mL; R&D Systems), mouse TPO (10 ng/mL; R&D Systems), mouse Flt-3 ligand (10 ng/mL; R&D Systems), and human erythropoietin (1 U/mL; R&D Systems) were added at the start of the culture. Colonies were enumerated under an inverted microscope consecutively from day 5 to day 12. CFU-mix such as CFU-GEMMeg, CFU-GEM, and CFU-GEMeg was determined by Giemsa staining of cells plucked as individual colonies using fine-drawn Pasteur pipettes. To evaluate the B-cell differentiation potential of FL CMPs in vitro by limiting-dilution analysis, specific numbers of cells were sorted onto irradiated (30 Gy) OP9 stromal cell layers19 in 24-well plates with Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM) containing 10% FBS (Gemini Bioproducts, Woodland, CA), mouse SLF (10 ng/mL), and mouse IL-7 (10 ng/mL; R&D Systems). Similarly, to test the lineage relationships of each myeloid progenitor subset, 1000 cells from each population were sorted in triplicate onto irradiated OP9 stromal layers in 6-well plates containing IMDM supplemented with 10% FBS, mouse SLF (10 ng/mL), mouse IL-11 (10 ng/mL), and mouse TPO (10 ng/mL). Nonadherent cells were recovered 48 hours later, stained as described above, and sorted into methylcellulose cultures as described above. All cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified chamber under 7% CO2.

Evaluation of transcription factor expression

Total RNA was purified from 1000 double-sorted cells from each population and was amplified by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) as previously reported.16Primer sequences, conditions for amplification, and the expected lengths of products are shown in Table 1. Quantitation of expression of each gene was performed by a relative determination, comparing the level of any subject sequence in target samples to that in control cDNA prepared from 2 × 105whole fetal liver cells or thymocytes, using the Integrated Image analysis system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction primers and conditions

| cDNA . | Length . | Tm . | Cycles . | 5′ sequence . | 3′ sequence . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GATA-2 | 720 | 55 | 32 | 5′ CGG AAT TCG ACA CAC CAC CCG ATA CCC ACC TAT 3′ | 5′ CGG AAT TCG CCT ACG CCA TGG CAG TCA CCA TGC T 3′ | 67 |

| c-mpl | 322 | 60 | 30 | 5′ GCA GCA CCC AGT GGG ACA TAC CAG 3′ | 5′ GCC ATA GCG GAG TTC ATG CCT CAG G 3′ | 65 |

| NF-E2 | 400 | 60 | 34 | 5′ AGA TGG AAC TGA CTT GGC AAG 3′ | 5′ TCT GCA TCA CTG TAG TTG AGG 3′ | 66 |

| GATA-1 | 375 | 60 | 32 | 5′ GGA ATT CGG GCC CCT TGT GAG GCC AGA GAG 3′ | 5′ CGG GGT ACC TCA CGC TCC AGC CAG ATT CGA CCC 3′ | 68 |

| EPO-R | 452 | 55 | 32 | 5′ GGA CAC CTA CTT GGT ATT GG 3′ | 5′ GAC GTT GTA GGC TGG AGT CC 3′ | 69 |

| C/EBPα | 458 | 55 | 32 | 5′ TTC TAC GAG GCG GAG CCG CGG 3′ | 5′ GAT CAC CAG CGG CCG CAG CGC 3′ | 70 |

| Pax-5 | 439 | 65 | 36 | 5′ CTA CAG GCT CCG TGA CGC AG 3′ | 5′ TCT CGG CCT GTG ACA ATA GG 3′ | 72 |

| Aiolos | 463 | 65 | 32 | 5′ GTG TGC GGG TTA TCC TGC ATT AGC 3′ | 5′ ATC GAA GCA GTG CCG CTT CTC ACC 3′ | 45 |

| GATA-3 | 262 | 55 | 32 | 5′ TCG GCC ATT CGT ACA TGG AA 3′ | 5′ GAG AGC CGT GGT GGA TGG AC 3′ | 71 |

| HPRT | 249 | 60 | 30 | 5′ CAC AGG ACT AGA ACA CCT GC 3′ | 5′ GCT GGT GAA AAG GAC CTC T 3′ | 69 |

| cDNA . | Length . | Tm . | Cycles . | 5′ sequence . | 3′ sequence . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GATA-2 | 720 | 55 | 32 | 5′ CGG AAT TCG ACA CAC CAC CCG ATA CCC ACC TAT 3′ | 5′ CGG AAT TCG CCT ACG CCA TGG CAG TCA CCA TGC T 3′ | 67 |

| c-mpl | 322 | 60 | 30 | 5′ GCA GCA CCC AGT GGG ACA TAC CAG 3′ | 5′ GCC ATA GCG GAG TTC ATG CCT CAG G 3′ | 65 |

| NF-E2 | 400 | 60 | 34 | 5′ AGA TGG AAC TGA CTT GGC AAG 3′ | 5′ TCT GCA TCA CTG TAG TTG AGG 3′ | 66 |

| GATA-1 | 375 | 60 | 32 | 5′ GGA ATT CGG GCC CCT TGT GAG GCC AGA GAG 3′ | 5′ CGG GGT ACC TCA CGC TCC AGC CAG ATT CGA CCC 3′ | 68 |

| EPO-R | 452 | 55 | 32 | 5′ GGA CAC CTA CTT GGT ATT GG 3′ | 5′ GAC GTT GTA GGC TGG AGT CC 3′ | 69 |

| C/EBPα | 458 | 55 | 32 | 5′ TTC TAC GAG GCG GAG CCG CGG 3′ | 5′ GAT CAC CAG CGG CCG CAG CGC 3′ | 70 |

| Pax-5 | 439 | 65 | 36 | 5′ CTA CAG GCT CCG TGA CGC AG 3′ | 5′ TCT CGG CCT GTG ACA ATA GG 3′ | 72 |

| Aiolos | 463 | 65 | 32 | 5′ GTG TGC GGG TTA TCC TGC ATT AGC 3′ | 5′ ATC GAA GCA GTG CCG CTT CTC ACC 3′ | 45 |

| GATA-3 | 262 | 55 | 32 | 5′ TCG GCC ATT CGT ACA TGG AA 3′ | 5′ GAG AGC CGT GGT GGA TGG AC 3′ | 71 |

| HPRT | 249 | 60 | 30 | 5′ CAC AGG ACT AGA ACA CCT GC 3′ | 5′ GCT GGT GAA AAG GAC CTC T 3′ | 69 |

Results

Prospective isolation of fetal liver myeloerythroid progenitors

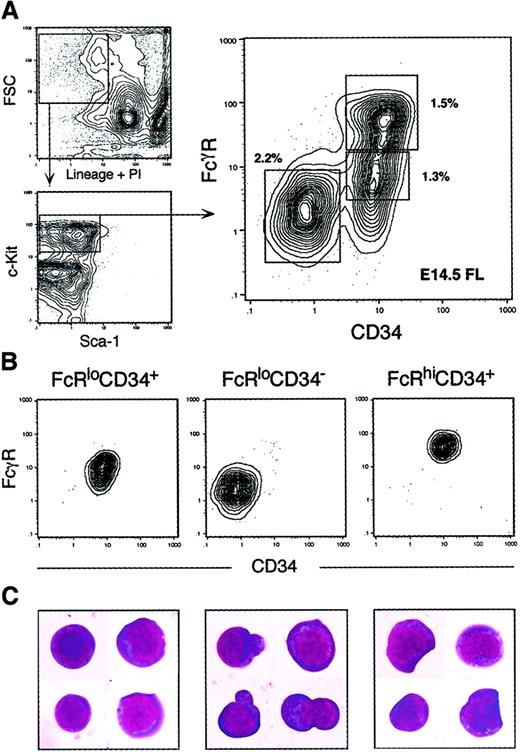

We have previously reported that the IL-7Rα+fraction of adult mouse BM does not contain myeloid progenitors,15 and we have recently determined that the IL-7Rα+ fraction of E14 FL largely lacks myeloid potential.74 In initial studies, we could detect no colony-forming activity within 1000 cells plated from the lineage (Lin)+ fraction of whole FL (not shown). Figure1A shows the Sca-1/c-Kit expression profile of the Lin−IL-7Rα− fraction of E14.5 FL. Similar to the Lin+ fraction, we could detect no colony-forming activity from cultures containing up to 10 000 Lin−IL-7Rα−c-Kit− cells (not shown). When the Lin−IL-7Rα−c-Kit+ fraction of whole FL was assayed, however, robust myeloerythroid colony-forming activity was observed. We estimate that approximately 99% of myeloerythroid colony-forming cells can be found within the Lin−IL-7Rα−c-Kit+ fraction when cultured in methylcellulose containing steel factor (SLF), flt-3 ligand (FL), interleukin (IL)-3, IL-11, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), thrombopoietin (TPO), and erythropoietin (EPO). We therefore focused our search for primitive myeloid progenitors within the Lin−IL-7Rα−c-Kit+ fraction. The Lin−IL-7Rα−c-Kit+ fraction can be divided into Sca-1+ and Sca-1− subsets, each comprising roughly 0.2% to 0.4% and 4% to 6% of E14.5 FL cells, respectively. The Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+(Thy-1.1lo) population has been shown to be highly enriched for HSCs in both BM20-22 and FL.7,8AA4.1 is another important marker of FL HSCs8 and can similarly be used to further enrich the Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ fraction for HSC activity. Cells within the Lin−IL-7Rα− c-Kit+Sca-1−fraction did not express Thy1.1 or AA4.1 at levels above background staining (not shown). To prevent HSCs from confounding our search for lineage-committed progenitors, we added Thy1.1 and AA4.1 to the lineage cocktail to visualize and remove antigen-positive cells by flow cytometry. The Lin−IL-7Rα−c-Kit+Sca-1−AA4.1−fraction was subsequently divided into 3 subpopulations according to the expression profiles of the Fcγ receptor II/III (FcγR), an important marker of myelomonocytic cells and a progenitor marker in fetal liver hematopoiesis,23 and CD34, previously shown to mark hematopoietic progenitors.24-26 The FACS profiles of these FcγRloCD34+, FcγRloCD34−, and FcγRhiCD34+ subpopulations is shown in Figure1A. Each of these populations was distinct and could be sorted to purity (Figure 1B-C). FL HSCs (Lin−IL-7Rα−c-Kit+Sca-1+AA4.1+) were FcγRlo and were approximately 90% CD34+(not shown).

Identification of myeloid progenitors in murine fetal liver.

(A) Live, Lin−IL-7R−AA4.1− cells were gated and analyzed for expression of the c-Kit and Sca-1 surface markers. The Lin−IL-7R−AA4.1−Sca-1−c-Kit+fraction was subdivided into FcγRloCD34+, FcγRloCD34−, and FcγRhiCD34+ populations. Percentages of each population relative to whole FL are shown next to each sort gate. (B) Reanalysis of sorted populations. Each was isolatable to purity after 2 consecutive sorts. (C) Cellular morphology of sorted populations (60 × magnification, Giemsa/May-Grünwald staining). Note the unusual cytoplasmic protrusions of FcγRloCD34− cells and the presence of myelomonocytic characteristics in FcγRhiCD34+cells.

Identification of myeloid progenitors in murine fetal liver.

(A) Live, Lin−IL-7R−AA4.1− cells were gated and analyzed for expression of the c-Kit and Sca-1 surface markers. The Lin−IL-7R−AA4.1−Sca-1−c-Kit+fraction was subdivided into FcγRloCD34+, FcγRloCD34−, and FcγRhiCD34+ populations. Percentages of each population relative to whole FL are shown next to each sort gate. (B) Reanalysis of sorted populations. Each was isolatable to purity after 2 consecutive sorts. (C) Cellular morphology of sorted populations (60 × magnification, Giemsa/May-Grünwald staining). Note the unusual cytoplasmic protrusions of FcγRloCD34− cells and the presence of myelomonocytic characteristics in FcγRhiCD34+cells.

In vitro characterization of FL progenitors

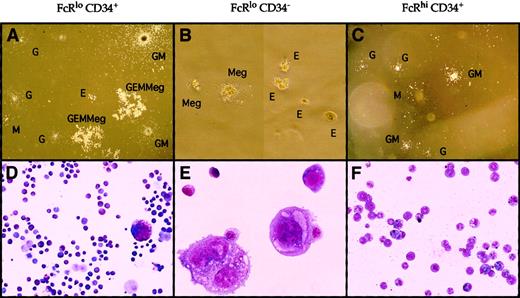

We evaluated the myeloid colony-forming activity for each of the above populations in methylcellulose. Results are shown in Figures2 and 3. In the presence of SLF, FL, IL-3, IL-6, IL-11, EPO, and TPO, more than 90% of sorted single FcγRloCD34+ cells gave rise to various types of myeloid colonies including CFU-Mix, CFU-MegE, BFU-E, CFU-Meg, CFU-GM, CFU-G, and CFU-M (Figures 2, 3). The distribution of colony types arising from single FcγRloCD34+ cells is shown in Figure 3, where colonies of all myeloerythroid lineages were found. In contrast, approximately 90% of single FcγRhiCD34+cells formed colonies composed only of macrophages or granulocytes, such as CFU-M, CFU-G, or CFU-GM, in response to any of the growth factor combinations. Megakaryocyte–erythroid (MegE) cells were not found in day 7 or day 10 colonies formed from 200 sorted FcγRhiCD34+ cells (data not shown). As with adult MEPs,16 FL FcγRloCD34−cells gave rise exclusively to CFU-Meg, CFU-E, or CFU-MegE colonies that contained only megakaryocytes or erythrocytes in response to the above growth factors, but they did not form colonies in the absence of TPO and EPO (not shown). GM cells were similarly not found in day 7 or day 10 colonies formed from 200 sorted FcγRloCD34−cells (not shown). Thus, the FcγRhiCD34+ and FcγRloCD34− progenitors are entirely restricted to GM and MegE lineages and are termed FL GMPs and FL MEPs, respectively.

Morphology of day 7 colonies derived from sorted FL myeloid progenitors.

Two hundred cells from each population were cultured in methylcellulose containing SLF, Flt-3 L, IL-3, IL-6, IL-11, EPO, TPO, and FL-conditioned media in 35-mm dishes. Upper panels (A-C) show the appearance of colonies in methylcellulose, and lower panels (D-F) show the cellular morphologies of colonies pooled from each progenitor subset (Giemsa/May-Grünwald staining). All types of myeloerythroid colonies were generated from FcγRloCD34+ cells (A, D). CFU-MegE colonies were generated from FcγRloCD34− cells (B, E), and CFU-GM, CFU-M, and CFU-G colonies were generated from FcγRhiCD34+ cells (C, F). Relative magnifications for each panel were (A) 8×, (B) 40×, (C) 8×, (D) 20×, (E) 60×, and (F) 40×.

Morphology of day 7 colonies derived from sorted FL myeloid progenitors.

Two hundred cells from each population were cultured in methylcellulose containing SLF, Flt-3 L, IL-3, IL-6, IL-11, EPO, TPO, and FL-conditioned media in 35-mm dishes. Upper panels (A-C) show the appearance of colonies in methylcellulose, and lower panels (D-F) show the cellular morphologies of colonies pooled from each progenitor subset (Giemsa/May-Grünwald staining). All types of myeloerythroid colonies were generated from FcγRloCD34+ cells (A, D). CFU-MegE colonies were generated from FcγRloCD34− cells (B, E), and CFU-GM, CFU-M, and CFU-G colonies were generated from FcγRhiCD34+ cells (C, F). Relative magnifications for each panel were (A) 8×, (B) 40×, (C) 8×, (D) 20×, (E) 60×, and (F) 40×.

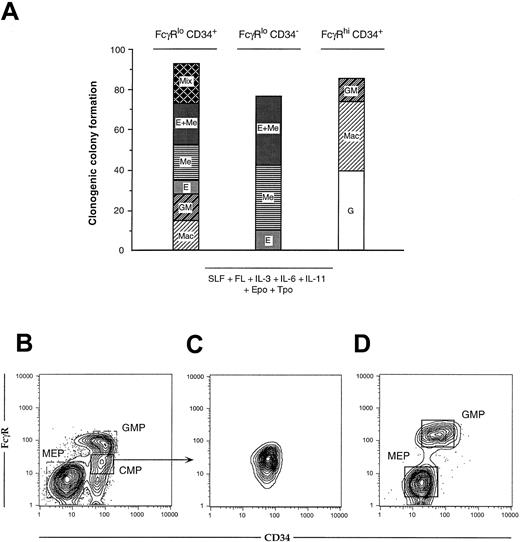

Clonogenic colony formation and precursor-progeny relationships of myeloerythroid progenitor subsets.

(A) At least 100 wells receiving a single cell from each sorted progenitor population were scored. FcγRloCD34+ cells produced all myeloid colony types, including CFU-GEMMeg, whereas FcγRloCD34− and FcγRhiCD34+ populations gave rise only to MegE and GM colonies, respectively. (B) One thousand cells from each Lin−IL-7Rα−c-Kit+Sca-1−progenitor subset were sorted onto irradiated OP9 stromal layers supplemented with SLF, IL-11, and TPO. (C) Reanalysis of sorted FcγRloCD34+ cells. (D) Culture supernatants were harvested after 48 hours on OP9 and analyzed for myeloid progenitor markers. Lin−IL-7Rα−c-Kit+Sca-1− cells were recovered from cultured FcγRloCD34+ cells, but not from the other 2 progenitor subsets (not shown). FcγRloCD34+ cells generated both FcγRhiCD34+ and FcγRloCD34− subsets. Recovered FcγRhiCD34+ and FcγRloCD34− cells were sorted into methylcellulose cultures and differentiated exclusively to either GM or EMeg cell types (not shown). We therefore term FcγRloCD34+ cells FL common myeloid progenitors (CMPs), FcγRhiCD34+ cells FL granulocyte–monocyte-restricted progenitors (GMPs), and FcγRloCD34− cells FL megakaryocyte–erythrocyte-restricted progenitors (MEPs).

Clonogenic colony formation and precursor-progeny relationships of myeloerythroid progenitor subsets.

(A) At least 100 wells receiving a single cell from each sorted progenitor population were scored. FcγRloCD34+ cells produced all myeloid colony types, including CFU-GEMMeg, whereas FcγRloCD34− and FcγRhiCD34+ populations gave rise only to MegE and GM colonies, respectively. (B) One thousand cells from each Lin−IL-7Rα−c-Kit+Sca-1−progenitor subset were sorted onto irradiated OP9 stromal layers supplemented with SLF, IL-11, and TPO. (C) Reanalysis of sorted FcγRloCD34+ cells. (D) Culture supernatants were harvested after 48 hours on OP9 and analyzed for myeloid progenitor markers. Lin−IL-7Rα−c-Kit+Sca-1− cells were recovered from cultured FcγRloCD34+ cells, but not from the other 2 progenitor subsets (not shown). FcγRloCD34+ cells generated both FcγRhiCD34+ and FcγRloCD34− subsets. Recovered FcγRhiCD34+ and FcγRloCD34− cells were sorted into methylcellulose cultures and differentiated exclusively to either GM or EMeg cell types (not shown). We therefore term FcγRloCD34+ cells FL common myeloid progenitors (CMPs), FcγRhiCD34+ cells FL granulocyte–monocyte-restricted progenitors (GMPs), and FcγRloCD34− cells FL megakaryocyte–erythrocyte-restricted progenitors (MEPs).

FcγRloCD34+ cells generate FcγRhiCD34+ GMPs and FcγRloCD34− MEPs

To test the lineage relationships among the 3 myeloid progenitor populations, we cultured 1000 double-sorted cells from each population on OP9 stromal layers for 48 hours in the presence of SLF, IL-11, and TPO and then analyzed their phenotypic changes by flow cytometry. FcγRloCD34+ cells gave rise to FcγRloCD34− cells and FcγRhiCD34+ cells (Figure 3 B-D). When FcγRloCD34− cells and FcγRhiCD34+ cells derived from cultured FcγRloCD34+ cells were resorted into methylcellulose, they formed colonies consisting only of MegE or GM, respectively (not shown). In contrast, neither FcγRloCD34− MEPs nor FcγRhiCD34+ GMPs gave rise to the other 2 progenitor subtypes; progeny from these populations appeared to rapidly lose c-Kit expression and differentiated into mature cell types (not shown). Thus, FcγRloCD34+ cells generate both FcγRloCD34− MEP and FcγRhiCD34+ GMP daughter cells that are respectively committed to either the MegE or GM lineages. Based on these data, we term FcγRloCD34+cells FL CMPs.

In vivo differentiation potential of FL progenitor populations

We next tested the in vivo differentiation potential of these 3 progenitor populations. All 3 progenitor populations rapidly differentiated into mature cells in vivo, and their outcomes corresponded with those of vitro colony assays. Six days after the injection of 10 000 FL CMPs into lethally irradiated recipient mice, both Gr-1+/Mac-1+ myelomonocytic cells and TER119+ erythroid cells were detectable in spleen and BM (not shown). In contrast, 10 000 FcγRloCD34− MEPs transiently reconstituted only TER119+ cells (not shown). Conversely, FcγRhiCD34+ GMP cells transiently gave rise only to Mac-1+ cells (not shown). In vivo demonstration of lineage restrictions identical to those observed in vitro suggested that the culture conditions described above were fully permissive for the generation of all myeloerythroid cell fates. Interestingly, though FL CMPs showed robust colony formation in vitro and generated large numbers of myeloerythroid progeny in vivo, FL MEPs and FL GMPs showed very small burst sizes (Figure 2A-C) when compared to their adult BM equivalents.16 This may partially explain our finding that none of the FL myeloid progenitor populations had significant day 8 spleen colony-forming unit (CFU-S) activity (Table2). Although most day 8 CFU-S potential within adult BM was found in MEPs, FL MEPs displayed no detectable activity. Similarly, adult CMPs had some day 8 CFU-S activity, whereas FL CMPs showed no detectable colony formation. It is important to note that FL HSCs were the only population tested that had day 8 CFU-S activity and formed colonies with high efficiency (Table 2). BM HSCs, however, did not show significant day 8 activity, as previously reported.22 Potential reasons for these differences between FL and BM are discussed below.

Day 8 spleen colony-forming unit frequency of hematopoietic progenitor populations

| Whole tissue . | HSC . | CMP . | MEP . | GMP . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult BM | ||||

| 1/33 000 | < 1/100 | 1/67 | 1/15 | < 1/500 |

| E14.5 fetal liver | ||||

| 1/25 000 | 1/38 | < 1/1000 | < 1/1000 | < 1/1000 |

| Whole tissue . | HSC . | CMP . | MEP . | GMP . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult BM | ||||

| 1/33 000 | < 1/100 | 1/67 | 1/15 | < 1/500 |

| E14.5 fetal liver | ||||

| 1/25 000 | 1/38 | < 1/1000 | < 1/1000 | < 1/1000 |

To evaluate self-renewal potential and proliferative capacity, we co-injected 200 HSCs (C57Bl6-CD45.2) with 10 000 cells of each FL myeloid progenitor population (C57Bl6-CD45.1) into lethally irradiated C57Bl6-CD45.2 hosts. In this competitive reconstitution assay, the progeny from either FL MEPs or FL GMPs cells were undetectable after 2 weeks (not shown). Myeloid progeny from FL CMPs were detectable at 2 weeks after injection but disappeared after 3 weeks (not shown). This indicates that in the context of transplantation, these populations have limited or no self-renewal capacity.

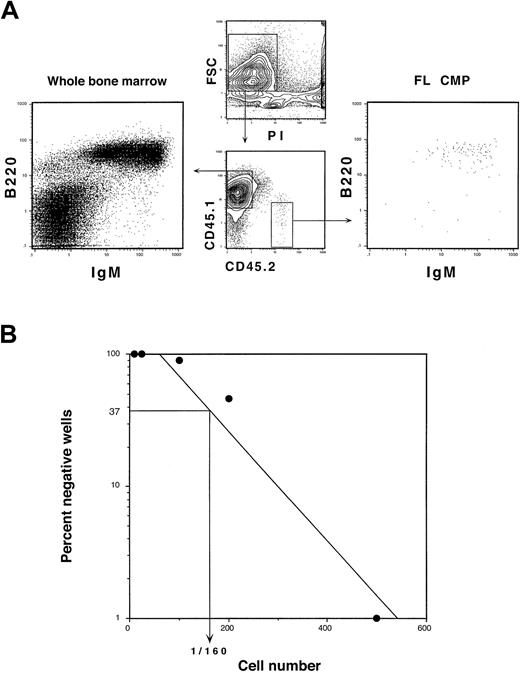

Myeloid progenitor populations largely lack lymphoid differentiation potential

We did not detect B-cell or T-cell progeny from either 20 000 FL MEPs or FL GMPs in the competitive reconstitution assays described above nor after intrathymic injections into sublethally irradiated congenic mice (not shown). Differentiation potentials of both FL GMPs and FL MEPs are thus entirely restricted to the myeloid lineages. FL CMPs did not generate T cells in either assay. B-cell progeny, however, were found in recipient spleens beginning at 14 days after transplantation (Figure 4A). To gauge the B-cell differentiation potential of FL CMPs, we performed limiting-dilution analysis on OP9 stromal layers supplemented with IL-7 as described.15 In this assay, 1 in 160 cells gave rise to B cells (Figure 4B). We have previously reported that the limiting-dilution frequency of B cells from adult CMPs was 1 in 2780.16 Thus, the FL CMP has significant B- but not T-lymphocyte differentiation potential, highlighting the close link between B cells and the myeloid lineage that has previously been described.27-29 Although FL CMPs can form significant numbers of B cells, the FL equivalent of the adult CLP has a limiting-dilution B-cell readout of 1 in 7 cells.74 Thus, the vast majority of the FL CMP population has myeloid-restricted differentiation potential.

FL CMPs have limited B-lymphoid differentiation potential.

(A) CD45.2+ FL CMPs (1 × 104) were competitively transplanted with 5 × 105CD45.1+ WBM cells into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ hosts. Splenocytes were harvested at 3 weeks after transplantation and were analyzed for donor-derived B and T cells. FL CMPs gave rise to no T-cell progeny (not shown) but showed minor production of B cells. Myeloid progeny derived from FL CMPs were largely absent from the spleen by this time. (B) Limiting-dilution analysis of B-lymphoid differentiation potential from FL CMPs. Graded numbers of FL CMPs were deposited into irradiated OP9 stromal cultures that were supplemented with IL-7 and SLF. One in 160 FL CMPs generated B-cell progeny in this assay.

FL CMPs have limited B-lymphoid differentiation potential.

(A) CD45.2+ FL CMPs (1 × 104) were competitively transplanted with 5 × 105CD45.1+ WBM cells into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ hosts. Splenocytes were harvested at 3 weeks after transplantation and were analyzed for donor-derived B and T cells. FL CMPs gave rise to no T-cell progeny (not shown) but showed minor production of B cells. Myeloid progeny derived from FL CMPs were largely absent from the spleen by this time. (B) Limiting-dilution analysis of B-lymphoid differentiation potential from FL CMPs. Graded numbers of FL CMPs were deposited into irradiated OP9 stromal cultures that were supplemented with IL-7 and SLF. One in 160 FL CMPs generated B-cell progeny in this assay.

Transcriptional profiles of fetal hematopoietic progenitors

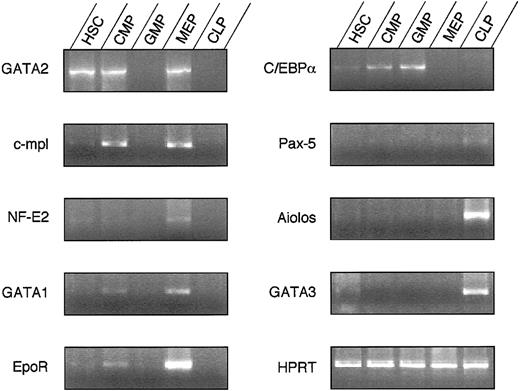

Because FL progenitor populations showed nearly identical lineage outcomes compared to their adult counterparts, we evaluated the expression of lineage-associated transcription factors in FL HSCs, the 3 subsets of myeloid progenitors, and the recently isolated FL counterpart of the CLP. Results are shown in Figure5. Among the panel of genes tested,GATA-230 and c-mpl31were expressed in FL HSCs, FL CMPs, and FL MEPs, but not in FL GMP or FL CLP counterparts. Other MegE-related genes, such asNF-E2,32GATA-1,33-35and the EPO receptor,36 were expressed in FL CMPs and FL MEPs but not in FL GMPs, and their expression levels were highest in FL MEPs. In contrast, the expression of C/EBPα, previously suggested to be a master regulatory gene in myelomonocytic cell development,37 38 was found in FL HSCs, FL CMPs, and FL GMPs but not in FL MEPs, and its expression level was highest in FL GMPs. All these genes were expressed in FL CMPs but not in FL CLP counterparts, suggesting potential roles for each in myeloid-specific cell fate decisions (Figure6).

Differential expression of transcription factors in fetal hematopoietic progenitors.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed for a number of genes previously associated with the development of specific lineages.

Differential expression of transcription factors in fetal hematopoietic progenitors.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed for a number of genes previously associated with the development of specific lineages.

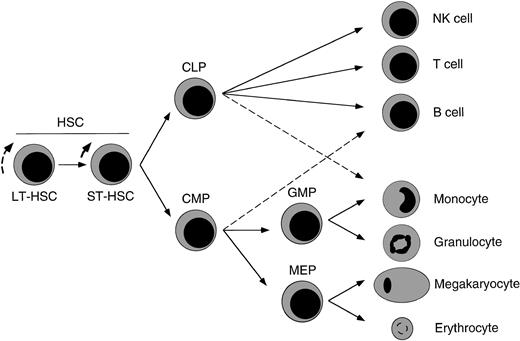

Proposed model of major hematolymphoid maturation pathways from HSCs in the fetal liver.

We propose that FL HSCs give rise to at least FL CLPs, which can form all cells of the lymphoid lineages,17 and FL CMPs, which can differentiate into either FL GMPs or FL MEPs that then form the cells of the granulocyte–monocyte or megakaryocyte–erythrocyte lineages, respectively. FL counterparts of adult CMPs and CLPs show incomplete lineage restriction to each respective pathway, with FL CLPs showing minor macrophage differentiation capacity and FL CMPs showing minor B-cell potential (dashed lines). Although denoted here, ST HSCs have not been formally identified in murine FL.

Proposed model of major hematolymphoid maturation pathways from HSCs in the fetal liver.

We propose that FL HSCs give rise to at least FL CLPs, which can form all cells of the lymphoid lineages,17 and FL CMPs, which can differentiate into either FL GMPs or FL MEPs that then form the cells of the granulocyte–monocyte or megakaryocyte–erythrocyte lineages, respectively. FL counterparts of adult CMPs and CLPs show incomplete lineage restriction to each respective pathway, with FL CLPs showing minor macrophage differentiation capacity and FL CMPs showing minor B-cell potential (dashed lines). Although denoted here, ST HSCs have not been formally identified in murine FL.

It has been reported that c-myb and PU.1 play important roles in the differentiation of myeloid/T cell39-41 and myeloid/B cell42-44 lineages, respectively. Both c-myb and PU.1 were expressed in HSCs, CLP counterparts, and all myeloid progenitors (not shown). The lymphoid-related transcription factor Aiolos45 was expressed at high levels in CLP counterparts but not in any other progenitor tested. GATA-3 has been reported to be expressed mainly in T cells.46 The expression of GATA-3gradually increased from HSC to CLP counterparts but was not seen in any of the myeloid progenitor populations. These data indicate that transcription factor expression is differentially regulated in these purified progenitor populations, and they are in agreement with the lineages affected in knock-out studies.47

Discussion

Definitive hematopoiesis in the FL has been suggested to differ significantly from adult hematopoiesis from the level of HSCs to committed progenitors.1,2,7,8,12,48 Here we sought to determine whether the lineage relationships we identified recently in adult murine BM15,16 are established early after the shift from primitive to definitive hematopoiesis during the development of the immune system. Our data suggest that the basic programs underlying the development of CMP, MEP, and GMP homologues are in fact established in the developing FL, similar to our recent description of an FL CLP counterpart.74 Expression patterns of transcription factors and growth factor receptors previously described as master regulators of lineage determination38,47 are similar between FL and BM counterpart populations. Interestingly, our expression results uniformly show that multipotent HSCs, CMPs, and CLPs appear to express most of these genes at low levels. This may reflect priming stages in which lineage commitment remains flexible49,50 because once these progenitors give rise to daughters with progressively limited differentiation capacity, the expression of many of these factors is quenched. Low-level expression of multiple master regulators in multipotent progenitors may suggest that chromatin remains relatively accessible to poise differentiation to any particular lineage. The isolation of progenitors downstream of HSCs that are restricted to either the lymphoid or the myeloid lineage and of MEPs and GMPs downstream of CMPs that are restricted to mutually exclusive progeny suggests that fate commitments are normally irreversible once made by upstream progenitors. Priming stages may thus exist as a hierarchy of diminishing flexibility that eventually restricts a stem cell to a particular effector cell fate. This program is likely dependent on instructive signals from the environment,51 and recent findings strongly suggest that lineage determination is controlled by the down-regulation of inappropriate growth factor receptors.52

Although the major pathways of definitive hematopoiesis appear to be established in embryogenesis, there exist several important differences between fetal and adult stem and progenitor cells. We have previously shown that FL HSCs can give rise to Vγ3+ and Vγ4+ T cells in fetal thymic organ cultures, whereas adult HSCs only give rise to thymocytes with αβ T-cell receptors.13 Similarly, FL HSCs can reconstitute both conventional B-2 and B-1a lymphocytes, whereas adult HSCs produce only conventional B cells.14 In this report, we have also surprisingly found that most day 8 CFU-S potential within the FL is possessed by HSCs. This is in stark contrast with adult BM, in which most day 8 CFU-S are produced by MEPs. Interestingly, these results are in accordance with early studies by Silini et al,53 who found, by morphologic analysis of day 8 to day 10 CFU-S, that FL-derived colonies had a higher percentage of mixed cell types than did those derived from adult BM, which were largely erythroid. Adult HSCs have little day 8 CFU-S activity; instead, HSCs have been shown to give rise to colonies appearing 12 days after transplantation. This delay, when compared to FL HSCs, may be due to increased relative quiescence of adult HSCs, as previously reported.54 It has been shown that short-term reconstituting HSCs from adult BM, which are actively in cell cycle, contain 4-fold more day 12 CFU-S activity than the relatively quiescent long-term reconstituting HSC subset.22 Even the more rapidly cycling adult subset, however, fails to give rise to significant numbers of day 8 colonies, suggesting that intrinsic differences exist in FL HSCs. Interestingly, FL MEPs and FL CMPs had no detectable CFU-S activity (Table 2). This was not attributable to inefficient homing of FL progenitors to adult spleens because donor-derived progeny from both populations could be detected in recipient spleens by FACS at similar time points (not shown). Failure of FL MEPs to generate spleen colonies may be explained by the relatively small burst sizes of colonies, as detected in methylcellulose assays (Figure 2B). Although the plating efficiency of single FL MEPs in these assays was roughly equivalent to that described from adult MEPs, the numbers of cells arising in each colony was dramatically reduced. Inefficient colony generation has been reported previously from FL populations,1 possibly suggesting that additional embryonic growth factors are required. The fact that robust colonies of all lineages were generated from FL CMPs under identical conditions, however, argues against this hypothesis. Instead, these findings suggest that FL MEPs are limited in proliferative capacity when compared to adult MEPs. This is paradoxical, however, because approximately 80% of FL cells at E14 are erythroid. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that additional pathways of erythroid production exist in the FL, FL CMPs give rise to robust BFU-e colonies (not shown), whereas FL MEPs give rise only to small, evanescent CFU-e colonies. This may suggest that the FL CMP is largely responsible for the quantitative production of erythrocytes by having greater self-renewal capacity or greater mitotic amplification potential. Accordingly, comparison of differential counts of colony types derived from single fetal and adult CMPs showed an approximate 2-fold increase in MegE production from the FL CMP. This may suggest that FL myeloerythroid progenitors are predisposed to differentiate along the erythroid pathway, as has been suggested.55 Supporting a critical role of FL CMPs in the generation of erythroid progeny are our recent findings in Pbx1-deficient mice (see accompanying article by DiMartino et al,73 page 618).

Pbx1-deficient mice have recently been created by targeted deletion and show a number of defects, the most important of which is embryonic death by day 16 that is likely the result of profound anemia (DiMartino et al,73 accompanying article, page 618). Phenotypic analyses of stem and progenitor cells in E14 FL showed approximate 2-fold decreases in total numbers of HSCs, MEPs, and GMPs. Strikingly, the FL CMP population showed 5- to 10-fold decreases. Analysis of clonal colony distributions showed that FL CMPs preferentially differentiated to GM lineages and showed approximately a 3-fold decrease in erythroid-containing colonies (DiMartino et al73). Taken together, our results in both wild-type and Pbx-1−/− mice strongly suggest that the CMP stage in FL hematopoietic differentiation is critical for the generation of erythrocyte numbers sufficient to oxygenate the rapidly expanding tissues of the mid- to late-gestation embryo.

Although the basic relationships among blood cell lineages are conserved from embryo to adult, the fidelity of progenitors normally restricted to either the lymphoid or myeloid lineages in BM is incomplete in the fetus. We have recently shown that FL progenitors, isolated based on the adult Lin−IL-7R+c-Kit+Sca-1+ Thy1.1− adult CLP phenotype, similarly develop to T, B, and natural killer cells, but they also show limited differentiation capacity to macrophages.74 Interestingly, no other myeloid cell type could be generated from this population. In accordance with these findings, previous reports have shown that lymphoid-restricted precursors in the FL can similarly give rise to macrophages but not to other myeloerythroid lineages.23,56 Conversely, our present data highlight the close relationship between myeloid cells and the B-lymphoid lineage. We found that FL CMPs, but not FL MEPs or FL GMPs, have significant B lymphoid differentiation potential. Limiting-dilution analysis showed that 1 in 160 FL CMPs gave rise to B-cell progeny when cultured on OP9 stromal layers. FL CMPs showed no T-cell potential, however, because intravenous or intrathymic injection of 1 × 104 cells yielded no T-cell progeny. We previously reported that adult CMPs gave rise to minor B-, but not T-, lymphoid development on intravenous injection. OP9 co-culture experiments showed only 1 in 3000 adult CMPs generated B cells, which led us to believe that we were sorting rare, committed B-cell precursors that shared surface phenotype with CMPs. Our data with FL CMPs suggests, however, that all CMPs, whether fetal or adult, have limited B-cell differentiation capacity. Closely linked development of myeloid cells and B cells has been demonstrated by many investigators. For example, B-cell lines have been observed to differentiate to macrophage-like cells with rearranged immunoglobulin loci,57 and mixed-lineage leukemias are often observed that share features of both myelomonocytic cells and B cells.28,58 It is interesting to speculate that mixed-lineage leukemias may arise from the transformation of CMPs or the activation of a similar gene expression program. Clonal myeloid/B bipotent progenitors have been previously reported in E12 murine FL.27 59 The relationship of these progenitors to FL CMPs is unclear, however, because they were enriched by AA4.1 and Sca-1 surface markers. Both AA4.1 and Sca-1 are highly expressed on FL HSCs and absent on FL CMPs, suggesting that these previously described precursors represent more primitive stages in the hematopoietic hierarchy.

The FL counterpart of the adult CLP can generate CD4+CD3− cells that have been shown to facilitate LN generation and development.74 We tested here whether the FL counterpart of the CMP could generate CD4+CD3− cells. FL CMPs were injected directly into the livers of newborn, congenic mice as previously described.60 We did not detect any CD4+CD3− cells in any tissue assayed from days 14 to 21 (not shown). It thus appears that CD4+CD3− cells derive from lymphoid-restricted progenitors, as previously hypothesized.60

FL CLP counterparts also generate both CD8α+ and CD8α− dendritic cells (DCs).74 After the intravenous injection of 1 × 104 FL CMPs, spleen, thymus, and lymph nodes were examined at 17 days after transplantation, where we observed both CD8α+ and CD8α− DCs in all tissues (not shown). This is in agreement with our recent data showing that adult CMPs generate both DC subsets.61Because FL CLP counterparts give rise to macrophages and presumably monocyte intermediates, it is difficult to assess the lineal ontogeny of DCs in the fetus. Although purified adult progenitor transplants have shown that most DCs are generated from CMPs, we62 and others63 have also shown that lymphoid-restricted progenitors give rise to DCs, but at lower numerical outputs. It is interesting to note that the lymphoid progenitors with DC potentials—CLPs, early thymocyte precursors, pro-T cells, and pre-T cells—can all be converted to myeloid cell fates by the instructive actions of cytokines.52 All of these populations in the adult BM and thymus are normally committed exclusively to the lymphoid lineages.64 We have recently shown that on expression of exogenously expressed IL-2 or GM-CSF receptors (and provision of cognate ligand), all of these progenitors can be driven to produce cells of the myelomonocytic cell lineages.52 These findings show that each of these progenitor populations maintains dormant myeloid differentiation capacity, and they may partially explain their DC potentials. Interestingly, B-cell–committed precursors cannot be converted to myeloid differentiation,52 nor can they give rise to DCs under any conditions.62 Taken together, these data may suggest that lineage restriction is a fine balance maintained largely by coordinated expression of specific growth factor receptors. Thus, a survey of growth factor receptor expression between fetal and adult progenitors may provide clues to the incomplete lineage restriction found in FL CLP and CMP counterparts when compared to their adult homologues. Concomitant analysis of transcription factors potentially underlying expression of these receptors, such as Pax-5 and PU.1, may also provide insight into the genetics of lineage restriction and cell fate determination.

In summary, the present report, along with the previous descriptions of embryonic and adult hematopoietic progenitor populations, provides a means to isolate cells at several stages of hematopoietic differentiation. The ability to isolate each population prospectively should allow the identification of candidate genes for lineage commitment and the transduction of these genes into isolated progenitors to resolve their roles. Comparison of the genetic profiles of fetal versus adult progenitors may identify pathways that restrict differentiation potentials that may lead to a better understanding of the development of mixed-lineage leukemias. Finally, the identification of counterpart populations in humans may allow the elucidation of target cells for oncogenic events underlying early hematologic malignancies.

We thank S.-I. Nishikawa for anti-IL-7R antibody, Amy Kiger and Len Zon for critical evaluation of the manuscript, Libuse Jerabek for excellent laboratory management and assistance with animal procedures, Veronica Braunstein for antibody preparation, the Stanford FACS facility for flow cytometer maintenance, and Lucino Hidalgo, Bert Lavarro, and Diosdado Escoto for animal care.

Supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Training Grant 5T32 AI-07290 (D.T.), by United States Public Health Service grant CA42551 (I.L.W.), and by 1997 Jose Carreras International Leukemia Foundation Claudia Adams-Barr grants (K.A.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

David Traver, Children's Hospital, Enders 650, 320 Longwood Ave, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail:dtraver@genetics.med.harvard.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal