Abstract

Sickle cell anemia is characterized by periodic vasoocclusive crises. Increased adhesion of sickle erythrocytes to vascular endothelium is a possible contributing factor to vasoocclusion. This study determined the effect of sickle erythrocyte perfusion at a venous shear stress level (1 dyne/cm2) on endothelial cell (EC) monolayers. Sickle erythrocytes up-regulated intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) gene expression in cultured human endothelial cells. This was accompanied by increased cell surface expression of ICAM-1 and also elevated release of soluble ICAM-1 molecules. Expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) messenger RNA (mRNA) was also strikingly elevated in cultured ECs after exposure to sickle cell perfusion, although increases in membrane-bound and soluble VCAM-1 levels were small. The presence of cytokine interleukin-1β in the perfusion system enhanced the production of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 mRNA, cell surface expression, and the concentrations of circulating forms. This is the first demonstration that sickle erythrocytes have direct effects on gene regulation in cultured human ECs under well-defined flow environments. The results suggest that perfusion with sickle erythrocytes increases the expression of cell adhesion molecules on ECs and stimulates the release of soluble cell adhesion molecules, which may serve as indicators of injury and/or activation of endothelial cells. The interactions between sickle red blood flow, inflammatory cytokines, and vascular adhesion events may render sickle cell disease patients vulnerable to vasoocclusive crises.

Sickle cell anemia is a genetic disorder of red blood cells (RBCs) characterized by chronic hemolysis and episodic vasoocclusive crises. Abnormally high adhesion of sickle erythrocytes to vascular endothelial cells (ECs) is hypothesized to be a contributing factor to the initiation and progression of vascular occlusion.1 Several plasma proteins and receptors expressed on erythrocyte membranes and EC surfaces have been shown to be involved in the receptor-mediated adhesion of sickle cells to the endothelium.2 3 In this study we examined the role of contact with flowing sickle erythrocytes on the production of cell adhesion molecules by endothelial cells.

Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) are cytokine-inducible, single-chain glycoproteins belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily. ICAM-1 is constitutively expressed on vascular endothelium and is up-regulated in response to various stimuli, including cytokines during inflammation.4,5 It plays an important role in leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells. Lymphocyte function–associated antigen-1 (LFA-1) (CD11a/CD18, αLβ2) and macrophage-1 (CD11b/CD18, αMβ2) are ligands expressed on leukocytes that bind to different domains of ICAM-1.6-9 Erythrocytes infected by Plasmodium falciparum, the malaria-causing protozoan, appear to adhere to ECs via ICAM-1 binding to members of the PfEMP1 (P falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein) protein family expressed on infected RBCs.10-14

VCAM-1 is present in activated ECs after stimulation with cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and IL-4.15,16 It serves as a counterreceptor for integrin very late activation antigen–4 (VLA-4, α4β1) and is important in the recruitment of leukocytes to inflammatory sites.17 VCAM-1 also participates in cellular interactions involved in lymphocyte activation.18,19 Moreover, it has been shown that sickle erythrocytes can adhere to cytokine-stimulated human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) via binding between VLA-4 on sickle erythrocyte membranes and VCAM-1 on endothelial cells.20,21Both ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 also exist as soluble forms circulating in plasma, although the physiological roles of these soluble cell adhesion molecules are not yet clearly known.22-25 As reported by in vivo data, sickle cell patients have elevated concentrations of soluble ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 in plasma.26-28 Saleh et al29showed that the treatment of hydroxyurea did not have significant influence on soluble ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 plasma concentrations in sickle cell patients.

In this study we investigated the effects of perfusion with sickle erythrocytes on the production of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 by cultured human endothelial cells. A flow apparatus was developed to perfuse sickle cells over cultured human ECs under well-characterized flow conditions for times of up to 24 hours. Endothelial cell surface expression and release of soluble forms of both ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 were examined after exposure to sickle cell perfusion at 1 dyne/cm2. Quantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) combined with high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis was used to determine the amounts of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 messenger RNA (mRNA) in endothelial cells.

Materials and methods

Endothelial cell culture

Primary HUVECs were harvested as previously described33and suspended in complete medium (cM199; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% heat-deactivated fetal bovine serum (FCS) (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 300 U/mL penicillin, 300 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.292 mg/mL glutamine (Gibco-BRL Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Cells were cultured on gelatin-coated glass slides (78 × 35 mm; Fisher Scientific Laboratories, Pittsburgh, PA). Prior to seeding, autoclaved glass slides were coated with 1% gelatin cross-linked with 0.5% glutaraldehyde (Sigma) as described by Smeets et al.34 Cells were maintained at 37°C with 5% carbon dioxide (CO2) in a humidified incubator. HUVECs reached confluence 2-3 days after seeding. Confluent monolayers were used for all experiments within 4 days.

Isolation of RBCs

This project comprised 12 adult sickle cell patients (HbSS) in healthy states (crisis-free and not on medication), and 20 mL venous blood was obtained from each patient. Hematocrits of these patients ranged from 22.5% to 38%. The controls were 13 healthy individuals, and 10 mL of venous blood was obtained from each subject. Red blood cells (RBCs) were separated from heparin-anticoagulated whole blood of normal individuals and sickle cell patients by centrifugation at 100g for 10 minutes to remove plasma and buffy coat. Packed RBCs were washed twice in Tris (tris[hydroxymethyl] aminomethane) buffer and then resuspended to a 1% hematocrit in serum-free media (SFM; pH 7.2) containing 5.0 μg/mL bovine insulin, 5.0 μg/mL human transferrin, 2 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (Sigma), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.292 mg/mL glutamine in M199). The low hematocrit (1%) keeps the viscosity of RBC suspension close to 0.01 poise so that the momentum balance equation for a Newtonian fluid can be used to calculate the wall shear stress generated by the RBC suspension flow, as described in the next section. In matched experiments, IL-1β (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was added to the RBC suspension at a final concentration of 50 pg/mL before beginning perfusion. For the reticulocyte counts in sickle blood, RBCs were isolated from whole blood as described above. Packed RBCs were then diluted to 106 cells/mL and incubated with the dye thiazole orange at room temperature for 1 hour, after which the reticulocyte percentage in whole RBCs was determined by using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) flow cytometer (FACScan, Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). The reticulocyte percentage in sickle RBCs was 9.17% ± 0.58%, the mean plus or minus the standard error of the mean (SEM), in 2 sickle cell patients. This is consistent with previous work in our laboratory.21

Flow apparatus

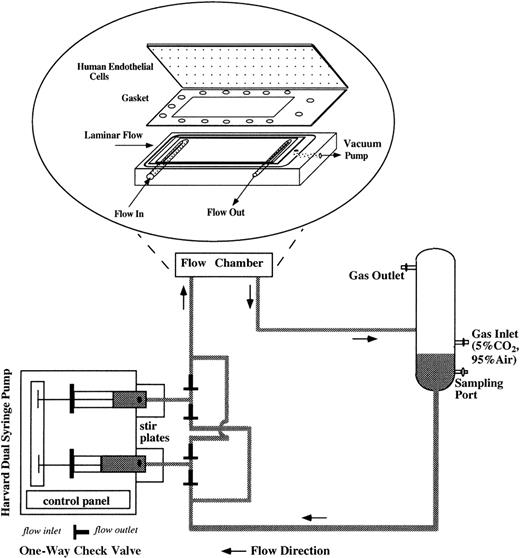

For flow studies, the flow system was assembled as shown in Figure1. The flow apparatus consisted of a parallel plate flow chamber, a reciprocating dual syringe pump (New Harvard ‘33′ Double Syringe Pump; Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA), and a glass reservoir. The confluent ECs were mounted in the flow chamber by applying vacuum to hold the glass slide, gasket (SF Medical, Hudson, MA), and polycarbonate base together and to form a flow channel of parallel plate geometry. The wall shear stress (τ) can be determined as τ = 6 μQ/h2w, as previously described by Frangos et al,35 where μ is the viscosity of the circulating media (1.1 cP), Q is the volumetric flow rate (4.8 mL/min), h is the height of the flow channel (0.046 cm), and w is the width (2.49 cm). For all experiments, τ was 1 dyne/cm2, a venous shear stress level. The flow rate was controlled by the syringe pump, which drove RBC suspension to recirculate in the flow loop. We installed 4 polypropylene 1-way check valves (Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL) to maintain the unidirectional flow into the flow chamber in spite of the reciprocating movement of the syringe pump. Stir bars were placed inside the syringes and stirred at 150-250 rpm at a 20-minute on/20-minute off cycle (Fisher Lab Controller/Timer, Fisher Scientific Laboratories) to avoid RBC sedimentation inside the syringes. The glass reservoir was connected to a humidified mixture of 95% air and 5% CO2 to control the pH of the circulating media and to keep the media oxygenated. Experiments were performed in a 37°C room. Media samples were drawn from the glass reservoir at several time points during 24-hour flow studies, and equal amounts of fresh media (RBC suspension) were replenished at the same time of sampling to maintain a 15-mL constant circulating volume. Media samples were centrifuged at 13 600gfor 10 minutes to remove RBCs and then stored at −80°C until the assays were performed. After being subjected to 24-hour flow studies, the hematocrit of RBC suspension was measured by capillary centrifugation and was found to be close to 1%, which was the starting hematocrit. At the end of each flow study, HUVECs were harvested either for RNA analysis or to examine cell surface expression of adhesion molecules.

Schematic of the flow apparatus used for exposing ECs to RBC perfusion.

The endothelial monolayers were mounted in the parallel plate flow chamber by applying vacuum to hold the glass slide, gasket, and polycarbonate base together. RBC suspensions were driven by a reciprocating dual syringe pump, which determined the flow rate. The glass reservoir was connected to a humidified mixture of 95% air and 5% CO2 to maintain the pH levels of the media and also to keep the media oxygenated.

Schematic of the flow apparatus used for exposing ECs to RBC perfusion.

The endothelial monolayers were mounted in the parallel plate flow chamber by applying vacuum to hold the glass slide, gasket, and polycarbonate base together. RBC suspensions were driven by a reciprocating dual syringe pump, which determined the flow rate. The glass reservoir was connected to a humidified mixture of 95% air and 5% CO2 to maintain the pH levels of the media and also to keep the media oxygenated.

RNA isolation

For RNA analysis, total cellular RNA was isolated from HUVECs at the end of flow studies using a FastRNA GREEN kit (BIO 101, La Jolla, CA). Total RNA was then resuspended in diethylpyrocarbonate-treated (DEPC-treated) (Sigma) water and stored at −80°C until the assays were performed. RNA concentration and purity were determined spectrophotometrically (DU-640 Spectrophotometer; Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA).

Synthesis of competitor RNA

The competitor RNA (cRNA) for target ICAM-1 mRNA was constructed as an internal control in RT-PCR. The cRNA and target RNA have identical terminal ends to be amplified with the same pair of primers. They also have the same sequence and similar lengths between 2 terminal ends, except that cRNA is 60 nucleotides shorter so that the RT-PCR products from cRNA and target RNA can be distinguished by different molecular weights. The reaction rate of cRNA and target RNA in RT-PCR can be assumed to be equal because they bear great similarity. Target RNA and cRNA were mixed together to perform RT-PCR. When the amount of cRNA (known) and the amount of target RNA (unknown) were the same, the ratio of their RT-PCR products was 1.

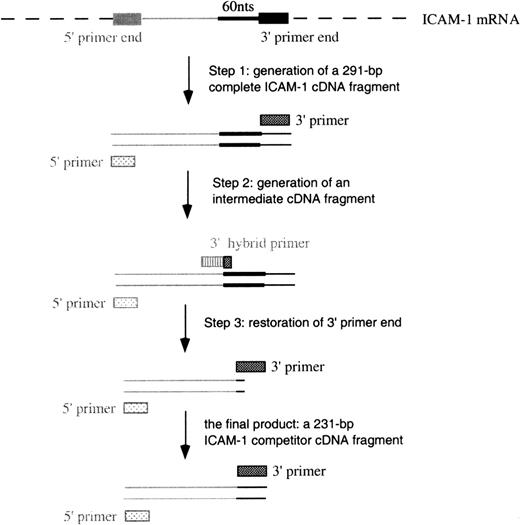

The construction of complementary DNA (cDNA) for cRNA included 3 steps (Figure 2) using different 3′ primers (Table 1). In step 1, the generation of a full-length ICAM-1 cDNA product was performed in a standard RT-PCR procedure using primers 3I and 5I (3′ and 5′ primers, respectively). A 291–base pair (bp) ICAM-1 cDNA was constructed. In step 2, 60 bps were deleted from the full-length cDNA using primer 3delI (a hybrid 3′ primer) and primer 5I to perform PCR. This step produced an intermediate cDNA fragment containing the first 10 bps of primer 3I and missing the 60 bps proximal to the 3′ end. In the last step, the 3′ end was restored in the intermediate cDNA using primers 3I and 5I to perform PCR. A 231-bp cDNA was thus constructed.

Schematic of the construction of cDNA for ICAM-1 competitors.

Similar procedures were used to construct VCAM-1 and GAPDH competitors.

Schematic of the construction of cDNA for ICAM-1 competitors.

Similar procedures were used to construct VCAM-1 and GAPDH competitors.

Sequence of primers used in RT-PCR

| Gene . | Primer Name . | Sequence (5′ → 3′) . | Positions . |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICAM-136 | 5I (5′ primer) | GGTGTATGAACTGAGCAATGTGCAAGAAG | 243 → 271 |

| 3I (3′ primer) | AGCACCGTGGTCGTGACCTCAG | 533 → 512 | |

| 3delI (3′ hybrid primer) | GTGACCTCAGTGAGGTTGGCCCGGGGTGC | 521 → 512, 451 → 433 | |

| 5I-PCR (5′ primer) | TAGCCAACCAATGTGCTATTCAAACT | 273 → 298 | |

| VCAM-137 | 5V (5′ primer) | AGATTGGTGACTCCGTCTCATTGACTTG | 113 → 140 |

| 3V (3′ primer) | CTGAACACTTGACTGTGATCGGCTTC | 415 → 390 | |

| 3delV (3′ hybrid primer) | GATCGGCTTCACCTGGATTCCTTTTTCCAA | 399 → 390, 329 → 310 | |

| GAPDH38 | 5G (5′ primer) | GGTTTACATGTTCCAATATGATTCCACCC | 189 → 217 |

| 3G (3′ primer) | GTTGTCATACTTCTCATGGTTCACACCC | 486 → 459 | |

| 3delG (3′ hybrid primer) | GTTCACACCCTGCAAATGAGCCCCA | 468 → 459, 398 → 384 |

| Gene . | Primer Name . | Sequence (5′ → 3′) . | Positions . |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICAM-136 | 5I (5′ primer) | GGTGTATGAACTGAGCAATGTGCAAGAAG | 243 → 271 |

| 3I (3′ primer) | AGCACCGTGGTCGTGACCTCAG | 533 → 512 | |

| 3delI (3′ hybrid primer) | GTGACCTCAGTGAGGTTGGCCCGGGGTGC | 521 → 512, 451 → 433 | |

| 5I-PCR (5′ primer) | TAGCCAACCAATGTGCTATTCAAACT | 273 → 298 | |

| VCAM-137 | 5V (5′ primer) | AGATTGGTGACTCCGTCTCATTGACTTG | 113 → 140 |

| 3V (3′ primer) | CTGAACACTTGACTGTGATCGGCTTC | 415 → 390 | |

| 3delV (3′ hybrid primer) | GATCGGCTTCACCTGGATTCCTTTTTCCAA | 399 → 390, 329 → 310 | |

| GAPDH38 | 5G (5′ primer) | GGTTTACATGTTCCAATATGATTCCACCC | 189 → 217 |

| 3G (3′ primer) | GTTGTCATACTTCTCATGGTTCACACCC | 486 → 459 | |

| 3delG (3′ hybrid primer) | GTTCACACCCTGCAAATGAGCCCCA | 468 → 459, 398 → 384 |

The construction of competitor cDNA for VCAM-1 and GAPDH (glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase, a housekeeping gene control) followed similar procedures using proper primers listed in Table 1. Each primer pair for these genes spanned several exons so that it allowed the discrimination between cDNA and genomic DNA amplification products. cDNA was cloned into pCR-Script Amp SK(+) cloning vectors (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) for amplification. To prepare cRNA, plasmids were linearized and transcribed by T7 RNA polymerase using an in vitro transcription kit (MAXIscript; Ambion, Austin, TX). After transcription, cRNA templates were recovered from 3% agarose gel (RNaid kits, BIO 101) and then resuspended in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water. The concentration of cRNA was spectrophotometrically quantified. GAPDH cRNA was mixed with either ICAM-1 or VCAM-1 cRNA and then diluted into a series of concentrations.

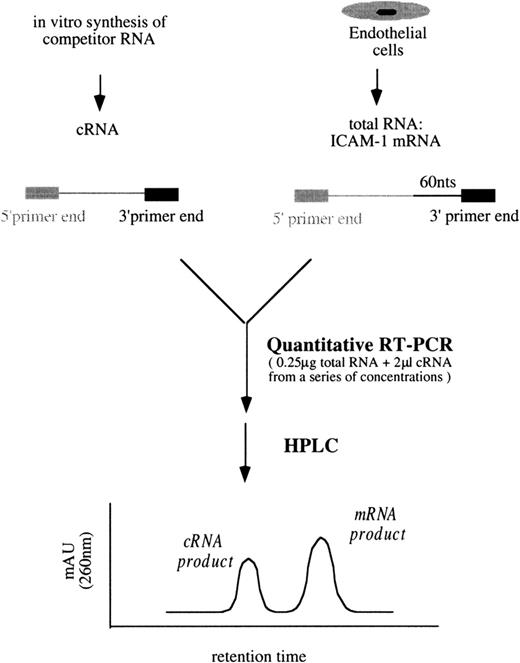

Quantitative RT-PCR

A schematic diagram of the simplified quantitative RT-PCR procedures for ICAM-1 is shown in Figure 3. Unless otherwise indicated, all reagents and enzymes used in RT-PCR were purchased from Perkin Elmer, Norwalk, CT. In a series of tubes, each containing 0.25 μg total RNA from the sample and 2 μL cRNA mixtures (ICAM-1/GAPDH) from a range of concentrations, the final reaction volumes were brought to 40 μL containing 200 μmol/L of each dNTP, 1× manganese dichloride (MnCl2), 1× rTth RT-buffer, 0.25 U/μL rTth DNA polymerase, 0.375 μmol/L primer 3I, and 0.375 μmol/L primer 3G in DEPC-treated water. Then RT was performed at 70°C for 15 minutes. Each of the 40 μL RT products was aliquoted into 2 tubes, one for the following ICAM-1 PCR amplification and the other for GAPDH. In ICAM-1 PCR amplification, 20 μL RT products were mixed with 80 μL PCR buffer containing 1× chelating buffer, 2.0625 mmol/L magnesium dichloride (MgCl2), 0.1875 μmol/L primer 5I-PCR, and 0.09375 μmol/L primer 3I in autoclaved water.

Simplified procedures of quantitative RT-PCR followed by HPLC analysis to determine ICAM-1 mRNA levels.

Similar procedures were used to quantify VCAM-1 mRNA amounts.

Simplified procedures of quantitative RT-PCR followed by HPLC analysis to determine ICAM-1 mRNA levels.

Similar procedures were used to quantify VCAM-1 mRNA amounts.

The PCR buffer for GAPDH was the same as that for ICAM-1 except that primers 5G and 3G were replaced for primers 5I-PCR and 3I, respectively. PCR amplification included a 3-minute incubation at 94°C and 35 cycles at 95°C for 10 seconds and 60°C for 15 seconds, finishing with a 6-minute incubation at 70°C in a thermocycler (GeneAmp PCR System 9600; Perkin Elmer). In each tube, PCR products contained either an ICAM-1 mixture of 261-bp target cDNA/201-bp competitor cDNA or a GAPDH mixture of 298-bp target cDNA/238-bp competitor cDNA. They were analyzed by HPLC (Figure 3). The titration of VCAM-1 mRNA amounts followed similar procedures using proper primers and VCAM-1/GAPDH cRNA mixtures.

HPLC analysis

PCR products were quantified using an HPLC Spectra System (Thermo Separation Products, Riviera Beach, FL) equipped with an anion-exchange column (4.6 mm ID × 7.5 cm L; TOSOHAAS, Montgomeryville, PA). A mobile phase of 20 mmol/L Tris solution (buffer A, pH 9.0) and 20 mmol/L Tris per 1 mol/L sodium chloride (NaCl) solution (buffer B, pH 9.0) was used. The gradient program began with the composition of 55% buffer A and 45% buffer B, which linearly changed to 40% buffer A and 60% buffer B in 30 minutes, during which time PCR products were separated and monitored at 260 nm. For titration of each RNA sample, ratios of target cDNA and competitor cDNA were linear with correspondingly added cRNA amounts in a log-log scale. Therefore, an estimated amount of cRNA, which would produce a product ratio of 1, can be calculated using linear regression.

Flow cytometry

For flow cytometric analysis, EC monolayers were washed 3 times with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (D-PBS, calcium- and magnesium-free [Ca++/Mg2+free]; Sigma) at the end of flow studies. No significant RBC attachment to EC monolayers was observed by using an inverted phase-contrast microscopy. HUVECs were then removed from the glass slides after incubation with 50 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) for 10 minutes at 37°C followed by centrifugation at 13 600g for 10 minutes. The pellet was washed once and then resuspended in 500 μL D-PBS per 0.25 × 106 cells. Fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated (FITC-conjugated) mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) antihuman ICAM-1 monoclonal antibody (mAb) or FITC-conjugated mouse IgG antihuman VCAM-1 mAb (both from R&D Systems) was added to the cell suspension at a final concentration of 3 μg/mL and incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C. Unbounded antibody was removed by centrifugation at 13 600g for 10 minutes. Labeled cells were fixed in 1% formaldehyde and then analyzed using a FACScan flow cytometer. At least 5000 cells were analyzed, and the results were expressed as geometric mean fluorescence. Background binding was detected using fluorescein-conjugated mouse IgG isotype controls (R&D Systems).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Soluble ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 released into the flow system were measured by sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (R&D Systems).

Lactate dehydrogenase assay

The release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) into the circulating solution was used as an indicator of the extent of hemolysis during 24-hour flow studies. LDH concentration was measured spectrophotometrically by an LDH-L reagent kit (Ciba-Corning, Oberlin, OH). The percent of lysis was calculated by comparing the LDH concentrations of media samples from flow studies to the LDH concentrations of the media samples from negative control (0% lysis) and positive control (100% lysis). The negative control was fresh RBC suspension not subjected to any experiments. The positive control was fresh RBC suspension sonicated with a sonic dismembrator (Fisher Scientific Laboratories) to produce complete RBC lysis.

Data presentation

Data are presented as the mean plus or minus SEM, and n represents the number of experiments. Cumulative production levels were determined by a mass balance, which took into account samples withdrawn and fresh RBC suspension replenished. Statistical analysis was done by using 2-tailed t tests for paired samples from 2 groups and by using repeated measures of analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine the trends from cumulative production between 2 groups over time. ANOVA followed by the Fisher's protected least significant difference (PLSD) was used as appropriate. P < .05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

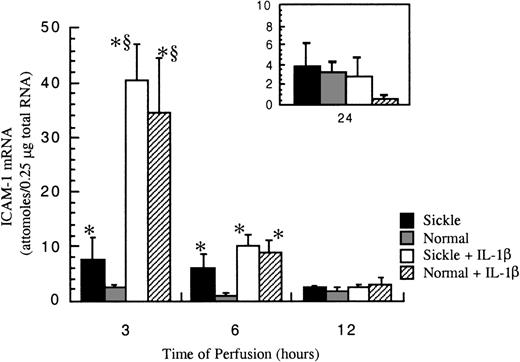

Sickle erythrocytes up-regulated ICAM-1 gene expression

After exposure to either sickle cell perfusion or normal RBC perfusion at 1 dyne/cm2, ICAM-1 mRNA levels in confluent HUVECs were measured at 3, 6, 12, and 24 hours (Figure4). At 3 and 6 hours, which were the early time points, perfusion with sickle erythrocytes significantly inducedICAM-1 gene expression. The increases caused by sickle cell perfusion were about 3-fold at 3 hours and 6-fold at 6 hours compared with matched normal RBC perfusion. Beyond 12 hours, ICAM-1 mRNA levels were relatively low and the same in both conditions. ICAM-1 mRNA expression was maximal at 3 hours, and decreased with time, but the expression was still maintained above the baseline for 24 hours. Basal amounts of ICAM-1 mRNA in cultured HUVECs were about 0.5 × 10−18 mole per 0.25 μg total RNA (data not shown).

ICAM-1 mRNA levels in ECs after exposure to different perfusing conditions.

The time course is depicted for ICAM-1 gene expression in HUVECs after exposure to sickle cell perfusion (Sickle), normal RBC perfusion (Normal), sickle cell perfusion with cytokine (Sickle + IL-1β), and normal RBC perfusion with cytokine (Normal + IL-1β). Data are shown as the mean plus or minus SEM, with n = 5-6 for 3 and 6 hours; n = 3-5 (approximately) for 12 and 24 hours.*Indicates significantly different from values in the matched normal RBC perfusion at the same time points (P < .05), and § indicates significantly different from values in the matched sickle RBC perfusion without IL-1β at the same time points (P < .05).

ICAM-1 mRNA levels in ECs after exposure to different perfusing conditions.

The time course is depicted for ICAM-1 gene expression in HUVECs after exposure to sickle cell perfusion (Sickle), normal RBC perfusion (Normal), sickle cell perfusion with cytokine (Sickle + IL-1β), and normal RBC perfusion with cytokine (Normal + IL-1β). Data are shown as the mean plus or minus SEM, with n = 5-6 for 3 and 6 hours; n = 3-5 (approximately) for 12 and 24 hours.*Indicates significantly different from values in the matched normal RBC perfusion at the same time points (P < .05), and § indicates significantly different from values in the matched sickle RBC perfusion without IL-1β at the same time points (P < .05).

IL-1β profoundly elevated ICAM-1 expression at early phases of the flow studies (Figure 4). The potent induction by IL-1β masked any discrimination between sickle and normal erythrocytes, so that observed mRNA amounts were the same in both sickle and normal RBC perfusions with this cytokine at all time points. The maximal induction of ICAM-1 mRNA by IL-1β occurred at 3 hours. The cytokine induction decreased about 75% at 6 hours. By 12 hours of perfusion, effects by IL-1β were negligible.

Measured ICAM-1 mRNA levels were internally normalized with GAPDH mRNA. The amounts of GAPDH mRNA were consistently the same in all experiments, approximately 5 × 10−16 moles per 0.25 μg total RNA (data not shown).

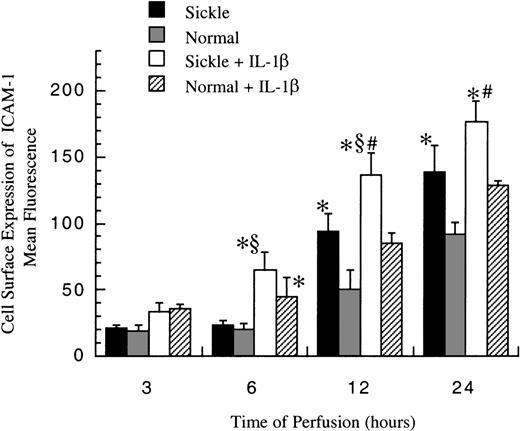

Cell surface expression of ICAM-1

The level of membrane-bound ICAM-1 (mbICAM-1) production associated with flow and cytokine stimulation was measured by flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 5, sickle cell perfusion and normal RBC perfusion had the same mbICAM-1 levels at 3 and 6 hours, which were approximately equal to constitutive amounts of mbICAM-1 expressed on cultured HUVECs. Thereafter, the surface expression started to rise in both conditions. Sickle cells caused about 4-fold and 6-fold increases above baseline in EC surface expression of ICAM-1 at 12 hours and 24 hours (P < .05), respectively. Normal erythrocytes elicited a similar pattern, whereas the increased magnitudes were smaller than those caused by sickle erythrocytes. At 12 and 24 hours, HUVECs subjected to sickle cell perfusion had nearly 2-fold increases in mbICAM-1 levels compared with HUVECs exposed to normal RBC perfusion.

Membrane-bound ICAM-1 levels in ECs after exposure to different perfusing conditions.

The time course is depicted for the cell surface expression of ICAM-1 in HUVECs after exposure to sickle cell perfusion (Sickle), normal RBC perfusion (Normal), sickle cell perfusion with cytokine (Sickle + IL-1β), and normal RBC perfusion with cytokine (Normal + IL-1β). Data are shown as the mean plus or minus SEM, with n = 6-9 (approximately) at 12 and 24 hours, and n = 3-7 at 3 and 6 hours. *Indicates significantly different from values in the matched normal RBC perfusion at the same time points (P < .05); #indicates significantly different from values in the matched normal RBC perfusion with IL-1β at the same time points (P < .05); and §indicates significantly different from values in the matched sickle RBC perfusion without IL-1β at the same time points (P < .05).

Membrane-bound ICAM-1 levels in ECs after exposure to different perfusing conditions.

The time course is depicted for the cell surface expression of ICAM-1 in HUVECs after exposure to sickle cell perfusion (Sickle), normal RBC perfusion (Normal), sickle cell perfusion with cytokine (Sickle + IL-1β), and normal RBC perfusion with cytokine (Normal + IL-1β). Data are shown as the mean plus or minus SEM, with n = 6-9 (approximately) at 12 and 24 hours, and n = 3-7 at 3 and 6 hours. *Indicates significantly different from values in the matched normal RBC perfusion at the same time points (P < .05); #indicates significantly different from values in the matched normal RBC perfusion with IL-1β at the same time points (P < .05); and §indicates significantly different from values in the matched sickle RBC perfusion without IL-1β at the same time points (P < .05).

In the presence of IL-1β, though mbICAM-1 amounts were still close to constitutive levels at 3 hours, this cytokine caused a 2-fold increase above baseline in both sickle and normal RBC perfusion at 6 hours (P < .05) (Figure 5). The time course of mbICAM-1 expression beyond 12 hours had a qualitatively similar pattern as that observed without IL-1β, whereas the magnitudes were higher in the presence of cytokines. At 12 and 24 hours, sickle cell perfusion with IL-1β caused 50% increases in mbICAM-1 expression compared with matched normal RBC perfusion with IL-1β.

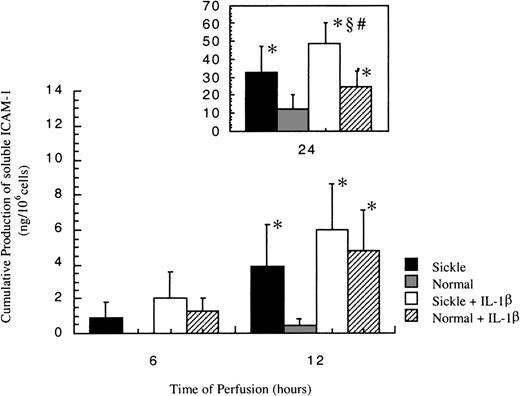

Release of soluble ICAM-1

In all experiments, no soluble ICAM-1 (sICAM-1) was detected before 6 hours. As shown in Figure 6, sICAM-1 was first detected at 6 hours in sickle cell perfusion, and the release increased with time. On the other hand, sICAM-1 was not detectable in normal RBC perfusion until 12 hours, when matched sickle cell perfusion induced a 9-fold higher release of sICAM-1 from HUVECs.

Soluble ICAM-1 amounts released from ECs after exposure to different perfusing conditions.

The time course is depicted for the release of soluble ICAM-1 by HUVECs after exposure to sickle cell perfusion (Sickle), normal RBC perfusion (Normal), sickle cell perfusion with cytokine (Sickle + IL-1β), and normal RBC perfusion with cytokine (Normal + IL-1β). Data are shown as the mean plus or minus SEM, with n = 6. *Indicates significantly different from values in the matched normal RBC perfusion at the same time points (P < .05); #indicates significantly different from values in the matched normal RBC perfusion with IL-1β at the same time points (P < .05); and§indicates significantly different from values in the matched sickle RBC perfusion without IL-1β at the same time points (P < .05).

Soluble ICAM-1 amounts released from ECs after exposure to different perfusing conditions.

The time course is depicted for the release of soluble ICAM-1 by HUVECs after exposure to sickle cell perfusion (Sickle), normal RBC perfusion (Normal), sickle cell perfusion with cytokine (Sickle + IL-1β), and normal RBC perfusion with cytokine (Normal + IL-1β). Data are shown as the mean plus or minus SEM, with n = 6. *Indicates significantly different from values in the matched normal RBC perfusion at the same time points (P < .05); #indicates significantly different from values in the matched normal RBC perfusion with IL-1β at the same time points (P < .05); and§indicates significantly different from values in the matched sickle RBC perfusion without IL-1β at the same time points (P < .05).

Soluble ICAM-1 production increased in both conditions in the presence of IL-1β (Figure 6). Although sICAM-1 concentrations were the same in sickle and normal RBC perfusion with IL-1β at 6 and 12 hours, sickle cells caused a 2-fold increase in the release of sICAM-1 compared with normal RBCs at 24 hours.

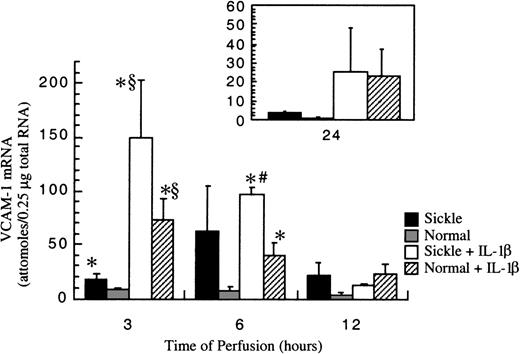

Sickle erythrocytes up-regulated VCAM-1 gene expression

Basal amounts of VCAM-1 mRNA in cultured HUVECs were about 1 × 10−18 mole per 0.25 μg total RNA (data not shown). After exposure to RBC perfusion at 1 dyne/cm2, VCAM-1 mRNA amounts in cultured HUVECs were measured at 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24-hour flow studies. In normal RBC perfusion, VCAM-1 mRNA levels were about 8 ± 2 × 10−18moles per 0.25 μg total RNA at 3 and 6 hours, then the levels decreased monotonically and returned to baseline at 24 hours. Similar to ICAM-1, VCAM-1 gene expression was up-regulated by sickle cells at early phases of flow studies (Figure7). At 3 hours, sickle cell perfusion caused a 2-fold increase in VCAM-1 mRNA amounts compared with normal RBC perfusion. The induction maximized at 6 hours, when an average 9-fold increase of VCAM-1 transcript was caused by sickle erythrocytes compared with normal erythrocytes. Thereafter in sickle cell perfusion, VCAM-1 mRNA levels decreased gradually, but they were still maintained about 3-fold above baseline until 24 hours.

VCAM-1 mRNA levels in ECs after exposure to different perfusing conditions.

The time course is depicted for VCAM-1 gene expression in HUVECs after exposure to sickle cell perfusion (Sickle), normal RBC perfusion (Normal), sickle cell perfusion with cytokine (Sickle + IL-1β), and normal RBC perfusion with cytokine (Normal + IL-1β). Data are shown as the mean plus or minus SEM, with n = 5-6 (approximately) for 3 and 6 hours, and n = 3-5 for 12 and 24 hours. *Indicates significantly different from values in the matched normal RBC perfusion at the same time points (P < .05); #indicates significantly different from values in the matched normal RBC perfusion with IL-1β at the same time points (P < .05); and §indicates significantly different from values in the matched sickle RBC perfusion without IL-1β at the same time points (P < .05).

VCAM-1 mRNA levels in ECs after exposure to different perfusing conditions.

The time course is depicted for VCAM-1 gene expression in HUVECs after exposure to sickle cell perfusion (Sickle), normal RBC perfusion (Normal), sickle cell perfusion with cytokine (Sickle + IL-1β), and normal RBC perfusion with cytokine (Normal + IL-1β). Data are shown as the mean plus or minus SEM, with n = 5-6 (approximately) for 3 and 6 hours, and n = 3-5 for 12 and 24 hours. *Indicates significantly different from values in the matched normal RBC perfusion at the same time points (P < .05); #indicates significantly different from values in the matched normal RBC perfusion with IL-1β at the same time points (P < .05); and §indicates significantly different from values in the matched sickle RBC perfusion without IL-1β at the same time points (P < .05).

IL-1β strikingly elevated VCAM-1 gene expression in both sickle and normal RBC perfusion (Figure 7). In contrast to ICAM-1, the profound induction by IL-1β did not mask the discrimination between sickle and normal RBCs at the early time points of flow studies. The increases in VCAM-1 transcript amounts caused by sickle cell perfusion with IL-1β were about 2-fold at 3 hours and 3-fold at 6 hours, respectively, when compared with matched normal RBC perfusion with IL-1β. However, beyond 12 hours, VCAM-1 mRNA was at the same levels in both conditions. Similar to ICAM-1, VCAM-1 gene expression induced by IL-1β maximized at 3 hours and decreased slowly thereafter. However, the inductive effects by this cytokine lasted until 24 hours, when VCAM-1 mRNA amounts reached a new steady-state level, about 20-fold above the baseline.

Measured VCAM-1 mRNA levels were also normalized with GAPDH mRNA. The amounts of GAPDH mRNA were consistently the same in all experiments, as previously mentioned in the ICAM-1 gene expression.

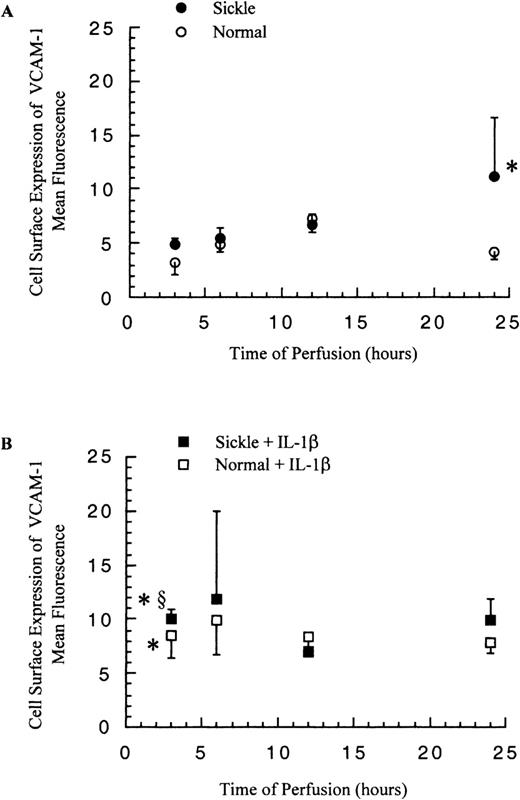

Cell surface expression of VCAM-1 and release of soluble VCAM-1

The cell surface expression of VCAM-1 on HUVECs was determined by flow cytometry, and the release of soluble VCAM-1 from HUVECs was detected by ELISA. In contrast to ICAM-1, membrane-bound and soluble VCAM-1 levels did not increase greatly in response to the significantly elevated VCAM-1 mRNA amounts.

The levels of mbVCAM-1 on HUVECs were comparable in both sickle and normal RBC perfusion until 12 hours. After 12 hours, in sickle cell perfusion, the levels kept rising to about 3-fold above the basal level at 24 hours, and in normal RBC perfusion, the mbVCAM-1 level returned to the baseline (Figure 8A). The release of sVCAM-1 by HUVECs had no significant differences in both conditions within 12 hours; thereafter, sickle cell perfusion caused a 1.6-fold increase over the normal RBC perfusion at 24 hours (P < .05) (Figure 9A).

Membrane-bound VCAM-1 levels in ECs after exposure to different perfusing conditions.

The time course is depicted for the cell surface expression of VCAM-1 in HUVECs after exposure to (A) sickle cell perfusion (Sickle) and normal RBC perfusion (Normal) and (B) sickle cell perfusion with cytokine (Sickle + IL-1β) and normal RBC perfusion with cytokine (Normal + IL-1β). Data are shown as the mean plus or minus SEM, with n = 6-9 (approximately) at 12 and 24 hours, and n = 3-7 at 3 and 6 hours. *Indicates significantly different from values in the matched normal RBC perfusion at the same time points (P < .05), and §indicates significantly different from values in the matched sickle RBC perfusion without IL-1β at the same time points (P < .05).

Membrane-bound VCAM-1 levels in ECs after exposure to different perfusing conditions.

The time course is depicted for the cell surface expression of VCAM-1 in HUVECs after exposure to (A) sickle cell perfusion (Sickle) and normal RBC perfusion (Normal) and (B) sickle cell perfusion with cytokine (Sickle + IL-1β) and normal RBC perfusion with cytokine (Normal + IL-1β). Data are shown as the mean plus or minus SEM, with n = 6-9 (approximately) at 12 and 24 hours, and n = 3-7 at 3 and 6 hours. *Indicates significantly different from values in the matched normal RBC perfusion at the same time points (P < .05), and §indicates significantly different from values in the matched sickle RBC perfusion without IL-1β at the same time points (P < .05).

Soluble VCAM-1 amounts released from ECs after exposure to different perfusing conditions.

The time course is depicted for the release of soluble VCAM-1 in HUVECs after exposure to (A) sickle cell perfusion (Sickle) and normal RBC perfusion (Normal) and (B) sickle cell perfusion with cytokine (Sickle + IL-1β) and normal RBC perfusion with cytokine (Normal + IL-1β). Data are shown as the mean plus or minus SEM, with n = 6. *Indicates significantly different from values in the matched normal RBC perfusion at the same time points (P < .05); #indicates significantly different from values in the matched normal RBC perfusion with IL-1β at the same time points (P < .05); and §indicates significantly different from values in the matched sickle RBC perfusion without IL-1β at the same time points (P < .05).

Soluble VCAM-1 amounts released from ECs after exposure to different perfusing conditions.

The time course is depicted for the release of soluble VCAM-1 in HUVECs after exposure to (A) sickle cell perfusion (Sickle) and normal RBC perfusion (Normal) and (B) sickle cell perfusion with cytokine (Sickle + IL-1β) and normal RBC perfusion with cytokine (Normal + IL-1β). Data are shown as the mean plus or minus SEM, with n = 6. *Indicates significantly different from values in the matched normal RBC perfusion at the same time points (P < .05); #indicates significantly different from values in the matched normal RBC perfusion with IL-1β at the same time points (P < .05); and §indicates significantly different from values in the matched sickle RBC perfusion without IL-1β at the same time points (P < .05).

The presence of IL-1β in the perfusion system elevated both EC expression of mbVCAM-1 and release of sVCAM-1 in comparison with matched experiments without IL-1β (Figure 8B and 9B). Membrane-bound VCAM-1 levels were the same in both sickle and normal RBC perfusion at all time points, whereas sVCAM-1 levels were 1.6-fold higher in sickle cell perfusion than in normal RBC perfusion at 24 hours.

LDH assays

The injury of red cells in the perfusion system was low until 12 hours. For all experiments, the percent lysis of the 1% hematocrit recirculating RBC suspensions was 2% at 6 hours and 5% at 12 hours, although hemolysis increased to about 27% at 24 hours. The extents of hemolysis were the same in sickle and normal erythrocytes at all time points. The presence of IL-1β did not affect hemolysis.

Discussion

We observed 3 important phenomena in this study: (1) Sickle erythrocytes have direct effects on gene regulation in cultured human ECs under vascular flow environments, (2) gene expression ofICAM-1 and VCAM-1 in ECs was up-regulated after exposure to sickle cell perfusion at 1 dyne/cm2; and (3) under RBC perfusion, the production of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 proteins appeared to be regulated via different mechanisms.

Sickle erythrocytes increased gene expression and cell surface expression of ICAM-1 in endothelial cells

The ICAM-1 molecule consists of 5 extracellular immunoglobulin domains, a hydrophobic transmembrane region, and a short cytoplasmic tail.36,39 ICAM-1 has a great variety of functions. Besides its important role in recruiting white cells to inflammatory sites, ICAM-1 is also involved in the cell-cell interactions in immune response,40 and it is the major human rhinovirus receptor.41,42 Although so far there has been no evidence showing that ICAM-1 is directly involved in sickle cell adhesion to ECs, the up-regulation of ICAM-1 production in HUVECs by sickle erythrocytes may have several physiological effects. For instance, increased ICAM-1 expression reflects an activated endothelium state that may lead to leukocyte adhesion and exacerbate vascular occlusive events. By analysis of over 1000 sickle cell patients, Mansour43 demonstrated that the strongest correlation between hematological variables and the severity of crises was found to be with total leukocyte counts not erythrocyte-related parameters, which suggests an important role of leukocytes in sickle cell disease. Lipowsky et al30 proposed that leukocyte-endothelium adhesion may be a significant determinant in the onset of sequestration and entrapment of RBCs and thus obstruct the microvascular lumen, which will contribute to the initiation of vasoocclusive crises.

Using ELISA, Wick et al44 demonstrated that stationary coincubation of sickle RBCs and HUVECs induced cell surface expression of ICAM-1 on ECs. Maximal mbICAM-1 expression was observed at 12 hours and was maintained until 24 hours. Although normal RBCs elicited a qualitatively similar response, the increase was lower than that observed for sickle cells. In our system, sickle erythrocytes stimulated ICAM-1 gene and cell surface expression in HUVECs under a venous shear stress level of 1 dyne/cm2. While increased mRNA occurred at early phases of flow studies, elevated mbICAM-1 protein levels occurred at late phases and increased monotonically until 24 hours. Transcription was maximized at 3 hours in both sickle and normal RBC perfusion. It decreased thereafter and reached a new steady-state constitutive expression level, higher than the unstimulated constitutive levels, at 12 hours. These data suggest that the up-regulation of ICAM-1 cell surface expression by sickle erythrocytes was at least partly regulated at the transcription level.

Differences of timing between maximal mRNA amounts and increased mbICAM-1 levels may be the time delay from transcription to translation. Another possible contributing factor for the continuously higher expression of mbICAM-1 in sickle cell perfusion at late phases, when both sickle and normal RBCs caused the same mRNA amounts, is enhanced EC translation activities by sickle cells. Detailed molecular bases for these changes remain to be determined. A possible intracellular messenger that leads to ICAM-1 mRNA induction is the free oxidant product released from sickle cells. Lo and colleagues45 showed that hydrogen peroxide increases ICAM-1 mRNA and cell surface expression in HUVECs in static coincubation, which maybe be secondary to the activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) by hydrogen peroxide.46 Therefore, locally increased free radicals, released from sickle erythrocytes by accelerated autooxidation of sickle hemoglobin,47 may be involved in ICAM-1 expression in ECs after exposure to sickle erythrocyte perfusion.

Sickle erythrocytes increased gene expression of VCAM-1 in endothelial cells

The predominant form of VCAM-1 molecules in human ECs contain 7 immunoglobulin domains, a single transmembrane region, and a short cytoplasmic domain.48 Swerlick et al20 and Natarajan et al21 demonstrated that VCAM-1 expressed on HUVECs stimulated with TNF-α for 9 hours or IL-1β for 24 hours may be responsible for binding sickle erythrocytes to cytokine-treated ECs under venous shear stress environments via sickle RBC membrane-associated VLA-4.

In this study, we observed up-regulated VCAM-1 gene expression in cultured ECs subjected to sickle erythrocyte perfusion at a venous shear stress level of 1 dyne/cm2. As with ICAM-1, the enhanced transcription of VCAM-1 was maximized at early phases of flow studies and decreased gradually after 6 hours. However, cell surface expression of VCAM-1 did not increase significantly. This suggested that though sickle erythrocyte perfusion profoundly raised the production of VCAM-1 at the transcriptional level, it did not have significant impact on the protein expression at least within 12 hours in the flow studies, during which time mbVCAM-1 levels were the same in both sickle and normal RBC perfusion.

Effects of IL-1β in ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 cell surface expression

Acute pain crises in sickle cell anemia are often preceded by or associated with infection and/or inflammation.30Concentrations of cytokines increase in plasma during inflammation and activate the vascular endothelium to increase interactions between sickle cells and endothelial cells. Synergistic elevation of cell surface ICAM-1 expression in ECs after exposure to sickle RBC perfusion with cytokines observed in our system is consistent with in vivo observations. Higher ICAM-1 levels reflect the activation and/or damage of ECs and may lead to abnormal adhesion of leukocytes.

Interestingly, although IL-1β masked the differences between sickle and normal RBCs in ICAM-1 transcription in HUVECs, perfusion with sickle cells still induced higher mbICAM-1 expression, suggesting an enhanced translation activity caused by sickle erythrocytes. On the contrary, mbVCAM-1 amounts on ECs were the same in both sickle and normal RBC perfusions in the presence of IL-1β, irrespective of higher VCAM-1 mRNA caused by sickle cells. These observations imply that the protein production of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 was modulated at different levels by RBC perfusions.

The release of soluble ICAM-1 and soluble VCAM-1

The existence of soluble ICAM-1 in human serum was first demonstrated in 1991 by Seth et al22 using immunoblotting and by Rothlein et al23 using ELISA. Soluble ICAM-1 contains most of the 5 extracellular immunoglobulin domains of membrane-bound ICAM-1 as well as the ability to bind specifically to LFA-1.23 The mechanism by which sICAM-1 molecules are released into extracellular fluid remains unclear. No alternatively spliced forms of ICAM-1 mRNA lacking the transmembrane domain have been identified yet, and it is therefore probable that the molecules are shed or cleaved from cell surfaces by proteases.49 The physiological role of sICAM-1 remains to be determined. It is possible that the released sICAM-1 is merely destined for clearance or may be regarded as EC markers of the presence of inflammatory states.50 Nonetheless, the ability of sICAM-1 to bind to LFA-1 shows that sICAM-1 may have some biological functions. Marlin et al51 demonstrated that sICAM-1 can inhibit rhinovirus infection, and Becker et al52 showed that sICAM-1 shed from human melanoma cells is able to inhibit cell-mediated cytotoxicity.

An increasing number of diseases have been correlated with the release of sICAM-1, including rheumatoid arthritis49 and atherosclerosis.53 In vivo data showed that children with sickle cell anemia have elevated sICAM-1 concentrations in plasma compared with normal individuals.26 Our data were consistent with this report, although the mechanisms by which sickle cells stimulated the release of sICAM-1 require further investigation. However, if the cleavage of membrane-bound ICAM-1 is the major source of soluble ICAM-1, as proposed previously,49 increased mbICAM-1 levels shown in our system may explain the observed increase in sICAM-1 amounts. Therefore, the overall increases in expression of ICAM-1 protein must take into account both mbICAM-1 and sICAM-1 in our system.

Soluble VCAM-1 is released by activated ECs in culture24and also can be detected in human plasma.25,54,55 As with ICAM-1, the production, metabolism, and functions of sVCAM-1 are still not clearly known. However, sVCAM-1 molecules remain capable of binding to leukocytes,56 which suggests that sVCAM-1 may still have biological functions. The shedding of VCAM-1 from cell surfaces by proteases is so far the main probable mechanism in the release of sVCAM-1 from human vascular ECs because no alternative splicing of VCAM-1 to eliminate the transmembrane region has been found.49 However, Terrel et al57 and Moy et al58 have shown that murine VCAM-1 has a truncated form containing only the first 3 immunoglobulin domains and a unique C-terminal tail generated by alternative splicing, which is released by phospholipase C treatment.

Soluble VCAM-1 levels are elevated in the serum of patients who have cancer and inflammatory diseases.50 Moreover, sVCAM-1 levels in sickle cell patients appeared to be significantly higher than in normal individuals.26-28 In this study, sVCAM-1 levels were higher in sickle cell perfusion than in normal RBC perfusion at late time points of flow studies. The presence of IL-1β enhanced the release of sVCAM-1.

In our system, the release of sICAM-1 and sVCAM-1 was not random and appeared to be regulated in ECs upon exposure to different RBC perfusions. Detailed information about the production and metabolism of soluble ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 can explain the higher amounts of sICAM-1 and sVCAM-1 caused by sickle erythrocytes so that they may serve as reliable diagnostic markers in clinical studies.

Transcriptional regulation of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1

An increasing number of reports have demonstrated that the elevated expression of EC ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 is either wholly or partly due to the up-regulation of genes.59 Our results are consistent with this observation, although detailed mechanisms by which sickle erythrocytes induced ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 gene expression in ECs remain to be determined. However, extensive research that has been done to elucidate the transcriptional regulation of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 by analysis of their 5′ regulatory sequences may provide insights into the possible pathways involved in sickle cell–EC interactions.

The production of ICAM-1 includes constitutive and inducible expression. The constitutive ICAM-1 expression was suggested to be regulated by a balance of enhancing and silencing transcription factors.60 ICAM-1 induction by cytokines generally requires new transcription and translation.5,61 Studies of the 5′ regulatory region of the cloned human ICAM-1 gene revealed that multiple cis-acting elements are involved in cytokine modulation of ICAM-1 expression including potential binding sites for nuclear transcription factors such as NF-κB, AP-1, AP-2, AP-3, and Sp-1.62-64 However, Sugama et al65 proposed that ICAM-1 may be mobilized much more rapidly from EC intracellular stores with thrombin stimulation, although there is no evidence of intracellular storage of ICAM-1 at present.

As to transcriptional regulation of VCAM-1, analysis of the 5′ promoter region for the human VCAM-1 gene showed that NF-κB and GATA binding sites are functional elements in the cytokine-induced activation of VCAM-1 gene expression.66,67 A putative silencer element in this region has also been identified, and it has been hypothesized to be involved in the repression of VCAM-1 transcription in unstimulated cells.66

In blood vessels, biochemical and mechanical factors may act together to modulate vascular events. Thus, it is possible that sickle erythrocytes may use biochemical pathways similar to those used by cytokines to affect the production of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 by ECs. The production may occur after release of certain factors, such as free radicals, due to the accelerated oxidation of sickle hemoglobin47 and lipids from unstable sickle erythrocyte membranes. Barabino et al68 showed that in comparison to normal RBCs, sickle erythrocytes move slowly across the EC monolayer at low shear rates, which may be the consequence of increased contact with ECs. The mechanical forces from repetitive contact between sickle erythrocytes and ECs may trigger signal transduction in ECs and cause consequent gene expression.

The experimental system

The flow apparatus described here demonstrated an in vitro model to examine the interactions between sickle cells and ECs under well-characterized flow conditions. The model can be used for investigating the effects of sickle erythrocytes on the function, metabolism, and gene regulation of ECs along with other important factors in the blood stream such as cytokines or protein components. The model can also be used for elucidating the cellular and molecular bases involved. At 24 hours, high hemolysis (about 27%) restricted the useful time frame of this system. The increased hemolysis after long-term exposure to shear and to surfaces of the flow system may be due to inherent characteristics of RBCs because both normal RBCs and sickle cells showed the same extent of hemolysis.

Conclusions

This study is the first demonstration that sickle erythrocytes have direct effects on gene regulation in cultured human ECs under controlled fluid mechanical environments. The results reveal that sickle erythrocyte perfusion increased the EC production of cell adhesion molecules, which may create a vascular environment that favors adhesion events, lengthens microcirculation transient times, and thus renders sickle cell anemia patients vulnerable to vasoocclusive crises.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cynthia Patton for help in the collection of clinic materials, Dr Susan McCormick for advice on molecular biology protocols, and Dr Thomas Chow for assistance in flow cytometry. The technical assistance of Marcella Estralla, Nancy Turner, and Dick Chronister is gratefully acknowledged.

Supported by grant R01 HL50601 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Reprints:Larry V. McIntire, Cox Laboratory for Biomedical Engineering, Institute of Biosciences and Bioengineering, Rice University, Houston, TX 77251-1892; e-mail: mcintire@rice.edu.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal