Natural killer (NK) cell activation is the result of a balance between positive and negative signals triggered by specific membrane receptors. We report here the activation of NK cells induced through the transmembrane glycoprotein CD43 (leukosialin, sialophorin). Engagement of CD43 by specific antibodies stimulated the secretion of the chemokines RANTES, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1, and MIP-1β, which was prevented by treatment of cells with the specific tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein. Furthermore, signaling through CD43 increased the cytotoxic activity of NK cells and stimulated an increase in the tyrosine kinase activity in antiphosphotyrosine immune complexes of NK cell lysates. PYK-2 was identified among the tyrosine kinase proteins that become activated. Hence, PYK-2 activation was observed after 20 minutes of CD43 stimulation, reached a maximum after 45 to 60 minutes, and decreased to almost basal levels after 120 minutes of treatment. Together, these results demonstrate the role of CD43 as an activation molecule able to transduce positive activation signals in NK cells, including the regulation of chemokine synthesis, killing activity, and tyrosine kinase activation.

AS ESSENTIAL COMPONENTS of the innate immune system, natural killer (NK) cells kill cellular targets and secrete cytokines that modulate acquired immunity.1 NK cell activity is tightly regulated by a counter-balance of signals that activate and inhibit their effector function.2-4 Inhibitory receptors, specific for major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I, have been widely characterized and are known to mediate their effects through cytoplasmic sequences termed immuno- receptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs). In contrast, receptor-ligand interactions responsible for activation of NK cells remain less characterized. Nevertheless, it is largely known that the activation process involves soluble factors such as the α/β interferons, cytokines (eg, tumor necrosis factor-α [TNF-α], interleukin-2 [IL-2], and IL-15), and chemokines, as well as activation signals transduced through certain membrane receptors. Receptors that have been reported to mediate positive signals in NK cells include the low-affinity receptor for IgG or CD16 (FcγRIII), CD2, CD28, and the CD40 ligand.2,5 Other receptors, such as CD69 and CD44, have been implicated in NK cell activation based on the ability of monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) against these molecules to induce lysis of Fc receptor-bearing target cells.6,7 Activation receptors are thought to mediate positive signals in NK cells through protein kinase activation, whereas NK cell receptor inhibitory signals involve recruitment of protein tyrosine phosphatases (ie, SHP). In this regard, it has been reported that ligation of CD16 and CD2 receptors triggers activation and recruitment of tyrosine kinases of the Src family.2 8

CD43 (leukosialin, sialophorin) is a transmembrane glycoprotein, selectively expressed by hematopoietic cells, that bears a heavily O-glycosylated extracellular N-terminal region.9 CD43 belongs to the growing family of cell-associated mucins, from which at least 4 members, GlyCAM, CD34, MadCAM, and PSGL-1, appear to be physiological ligands of selectins.10 However, it has been proposed that the extended structure of mucins and their negative charge may provide a repulsive barrier around the cell that limits nonspecific adhesion phenomena. In the case of CD43, its role as an adhesion receptor remains controversial, and different reports have provided evidence supporting both its adhesive and antiadhesive activity. Hence, this molecule has been described as a counter-receptor for intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), MHC class I molecules, C1q, E-selectin, galectin-1, and for a putative endothelial cell ligand.11-17 In contrast, several reports indicate that, due to its stiffened and large negatively charged structure, CD43 prevents the interaction of surface receptors with their ligands, acting as an antiadhesive molecule that negatively regulates T-cell adhesion and homing.18-21 Both adhesive and antiadhesive properties of CD43 have been recently integrated in a model that proposes a dual functionality of CD43 in regulating cell interactions depending on different immune events.10 This is further supported by recent data showing the impairment of CD43− leukocytes to emigrate in response to chemoattractants.22 Nevertheless, it is now clear that CD43 plays a role in the activation of T lymphocytes, monocytes, B cells, and cytotoxic lymphocytes.23-27 According to its role as an accessory molecule, engagement of CD43 with specific MoAbs regulates integrin-mediated T-cell adhesion to endothelial and extracellular matrix proteins and promotes cell aggregation in monocytes and T lymphocytes, thus demonstrating that CD43 regulates integrin function.28-31

Despite its well-established role as a stimulatory molecule, the signals triggered by CD43 receptor are poorly characterized. In this regard, it has been reported that CD43 is able to transduce signals that lead to intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and activation of protein kinase C (PKC). PKC, in turn, hyperphosphorylates the cytoplasmic domain of CD43.32,33Furthermore, it has also been reported that CD43 regulates tyrosine phosphorylation, including phosphorylation of Vav and mitogen-activated protein kinase, and that activation through CD43 induces its association to the tyrosine kinase Fyn in T lymphocytes.23,34 35

PYK-2 (proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2), also called RAFTK (related adhesion focal tyrosine kinase), CAKβ (cell adhesion kinase β), and CadTK (cell adhesion dependent tyrosine kinase), is a member of the FAK nonreceptor tyrosine kinase family and is expressed by different cell types, including brain, platelets, and other hematopoietic cells. PYK-2 shares significant sequence homology with FAK (60% identity in the central catalytic domain and 40% identity in both the C and N termini) and, like FAK, does not contain SH2 or SH3 domains, but presents several sites for binding of SH2/SH3-containing signaling proteins. PYK-2 is rapidly phosphorylated in response to stimuli that elevate calcium or activate PKC.36-40

We studied here the role of CD43 as an activation molecule able to transduce positive activation signals in NK cells, including the regulation of the tyrosine kinase PYK-2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

IL-2–cultured NK cells were obtained essentially as described.41 In brief, peripheral blood T lymphocytes (PBL) were cultured with irradiated (5 Gy) RPMI 8866 lymphoblastoid cells for 6 to 9 days in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; complete medium), followed by a negative selection step using an anti-CD3 MoAb plus rabbit complement (Behring, Marburg, Germany). The CD3− cells (<5% CD3+) were cultured with 50 IU/mL of recombinant human IL-2 (rhIL-2) until use. These cell populations are hereafter referred to as NK cells. After each purification process, the resulting population was characterized by flow cytometry analysis. We routinely obtained a cell population with a proportion of CD56+ and CD16+cells greater than 95% and with less than 5% of CD3+, CD19+, or CD14+ contaminating cells.

Antibodies and reagents.

The anti-CD43 MoAb TP1/36 (IgG1), HP2/21 (IgM), the nonactivatory anti-CD44 MoAb HP2/9 (IgG1), and the anti-CCR5 MoAb CCR5-01(IgM) have been previously described.42,43 The anti-CD56 K218 (IgG1) was kindly provided by Dr A. Moretta (Istituto Nazionale per la Ricerca sul Cancro e Centro Biotecnologie Avanzate, University of Genova, Genova, Italy). F(ab′)2 fragments were obtained by pepsin digestion of purified antibody.41 PYK-2 antipeptide polyclonal antibodies C-19 and N-19 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc (Santa Cruz, CA). The anti-Tyr(P) PY20 MoAb was from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY). [γ32P]ATP (4,000 Ci/mmol) was from ICN (Irvine, CA). Protein A-agarose and protein G-agarose were from Boehringer Mannheim (Mannheim, Germany). ECL reagents were from Amersham (Buckinghamshire, UK). Tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein was from Calbiochem-Novabiochem Ltd (Nottingham, UK). All other reagents used were of the purest grade available.

Preparation of antibody-coated dishes.

Plates were precoated overnight at 4°C with 2.5 μg/mL of antibody in adhesion buffer (20 mmol/L Tris/HCl, 150 mmol/L NaCl, pH 8.2), blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in adhesion buffer for 1 hour at room temperature, and then washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Chemokine quantification.

NK cells (106) were incubated in polypropylene tubes, to prevent signaling through integrins, in a final volume of 1 mL complete medium in the presence of 5 μg/mL of different MoAbs for different times at 37°C, 5% CO2. Cells were then centrifuged and the chemokines present in the supernatant were quantified. Human RANTES was measured using the Cytoscreen immunoassay kit (Biosource International, Inc, Camarillo, CA), and human macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α and MIP-1β were measured using the Quantikine immunoassay kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Redirected lysis assays.

Redirected lysis assays were performed as described.41 NK cells were in triplicate tested in a 4-hour 51Cr release assay against the murine P815 (FcγR+) mastocytoma cell line at different E/T ratios. MoAb were preincubated for 15 minutes with the target cells before NK cell addition. The percentage of specific lysis was calculated as described previously.41Data are expressed as the arithmetic mean of triplicates. In each case, spontaneous release was always less than 10% of the maximum lysis.

Preparation of cell lysates/immunoprecipitations.

IL-2–activated NK cells were washed twice with RPMI. Experiments were initiated by adding the cells (10 × 106 cells, unless otherwise stated) to 60-mm cultured dishes precoated with the relevant antibodies. Cells were incubated in ice for 15 minutes and then were incubated at 37°C for the indicated times. The incubation was stopped by solubilizing the cells in 1 mL of ice-cold lysis buffer (10 mmol/L Tris/HCl, pH 7.65, 5 mmol/L EDTA, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 30 mmol/L sodium pyrophosphate, 50 mmol/L NaF, 2 mmol/L sodium orthovanadate, 1% Triton X-100, 50 μg/mL aprotinin, 50 μg/mL leupeptin, 5 μg/mL pepstatin, and 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 10 minutes and the pellets were discarded. After centrifugation, supernatants were transferred to fresh tubes and proteins were immunoprecipitated at 4°C overnight with protein G-agarose–linked MoAbs directed against Tyr(P) proteins (PY20 MoAb) or protein G-agarose–linked goat polyclonal anti–Pyk-2 (C-19) antibody. Immunoprecipitates were washed 3 times with lysis buffer and either used for in vitro kinase reaction (see below) or extracted in 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer (200 mmol/L Tris/HCl, pH 6.8, 0.1 mmol/L sodium orthovanadate, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 6% SDS, 2 mmol/L EDTA, 4% 2-mercaptoethanol, and 10% glycerol) by boiling 5 minutes, were fractionated by SDS-PAGE (7.5%), and were further analyzed.

In vitro kinase reactions.

Reactions were performed as described.44 Briefly, immunoprecipitates were washed and pelleted (2,500 rpm 10 minutes at 4°C) 3 times in lysis buffer and twice with kinase buffer (20 mmol/L HEPES, 3 mmol/L MnCl2, pH 7.35). Pellets were dissolved in 40 μL of kinase buffer and reactions were initiated by adding 10 μCi of [γ32P] ATP. The reactions were performed at 30°C for 15 minutes and were stopped on ice by adding 10 mmol/L EDTA. After the in vitro kinase reactions, the pellets were washed in lysis buffer containing 10 mmol/L EDTA, extracted for 5 minutes at 95°C in 2× SDS-PAGE sample buffer, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. After fixing and drying of the gels, autoradiography was performed at −80°C. Autoradiograms were analyzed using an AGFA Studio ScanIIsi scanner (Montiel, Belgium) and bands were quantified using the Bio-Rad Molecular Analyst Software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Western blotting.

Cell lysis and immunoprecipitations were performed as described above. After SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred to Immobilon membranes using a Bio-Rad SD Transblot. Membranes were blocked using 3% nonfat dried milk in PBS, pH 7.2, and incubated for 2 hours at 22°C with the polyclonal antibody anti–Pyk-2 (C-19 or N-19) or with the anti-Tyr (P) PY20 MoAb, all diluted 1:500 in PBS containing 3% nonfat dried milk. After incubating membranes with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, immunoreactive bands were visualized using ECL reagents.

RESULTS

Increased secretion of chemokines and NK cell cytotoxicity by engagement of CD43.

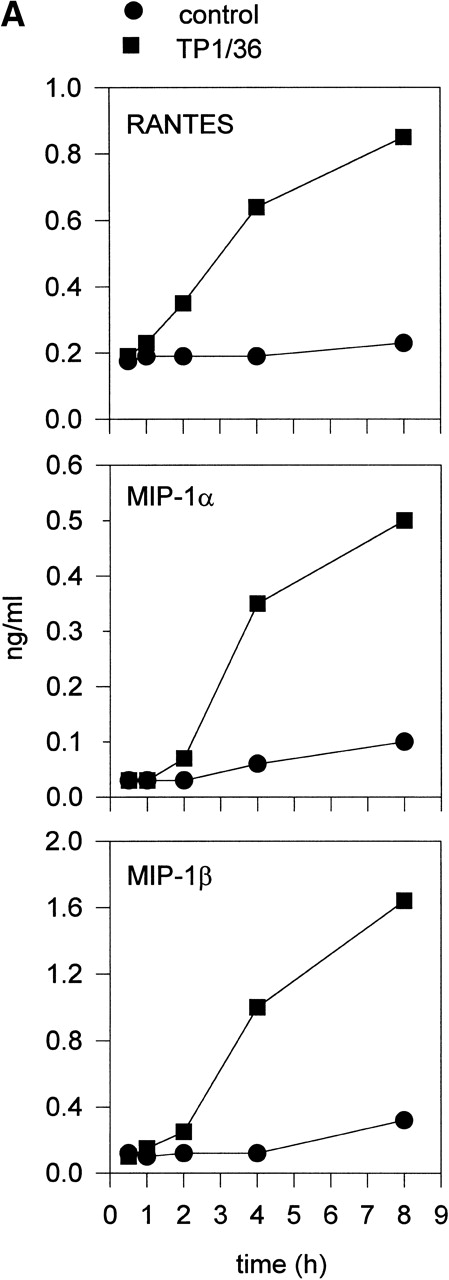

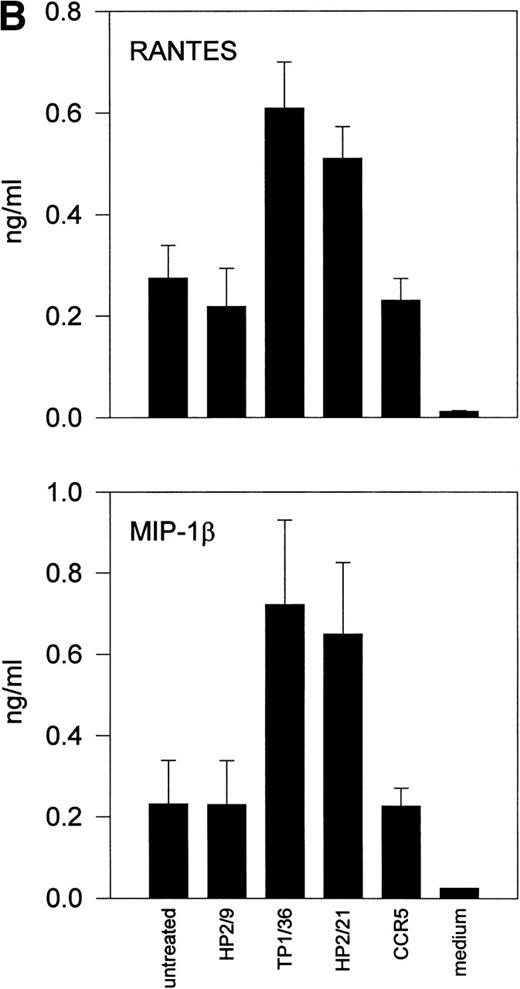

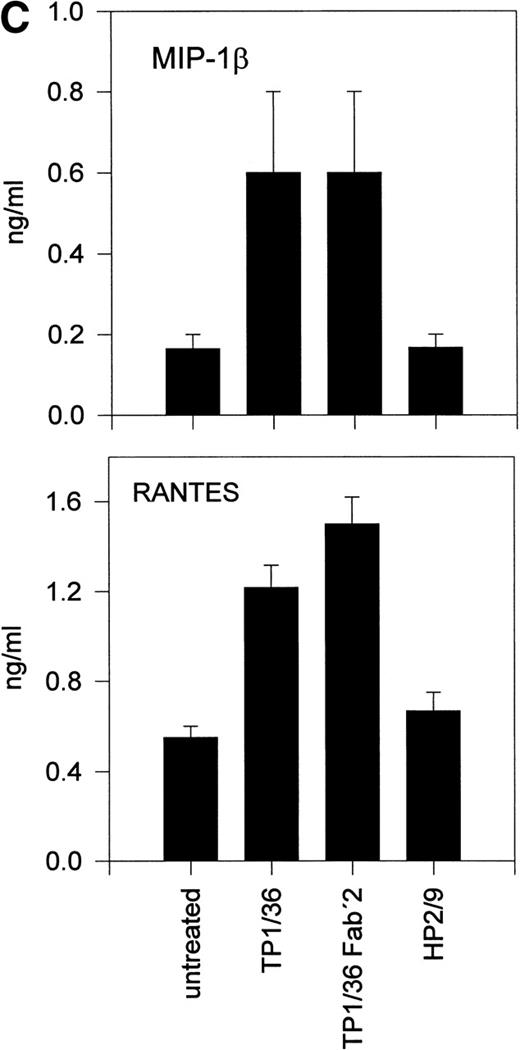

Upon activation, NK cells are able to secrete cytokines that modulate NK cytotoxic response and other immune events.45,46Different chemokines, including RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and lymphotactin, are secreted by NK cells.43,47-49 These chemokines trigger the directional migration or chemotaxis of NK cells, regulate cell polarization and redistribution of adhesion molecules, stimulate intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and cytolytic granule release, and augment NK-mediated cytotoxicity.50-53To investigate the possible role of CD43 as a triggering molecule in NK cells, we assayed the effect on chemokine secretion by NK cells of anti-CD43 MoAbs that have previously been described to stimulate integrin-mediated adhesion, cell polarization, and homotypic aggregation in T lymphocytes.28 54 IL-2–activated NK cells constitutively secrete MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES (Fig 1A through C). Engagement of CD43 with TP1/36 MoAb significantly increases the production of these chemokines by NK cells. The increased release of chemokines in NK cell supernatants was clearly detectable after 4 hours of incubation with the anti-CD43 TP1/36 and persisted after 8 hours of incubation (Fig 1A). Treatment of NK cells with cycloheximide abolished the secretion of chemokines induced by anti-CD43, thus indicating the requirement of protein synthesis for this process (data not shown). Engagement of CD43 with the anti-CD43 MoAb (HP2/21) of a different isotype also increased chemokine production by NK cells (Fig 1B). Furthermore, the incubation of NK cells on TP1/36 Fab′2 fragment-coated dishes also stimulated the secretion of chemokines (Fig 1C). In contrast, control isotype-matched MoAbs against the highly expressed membrane adhesion molecule CD44 or the chemokine receptor anti-CCR5 did not affect cytokine production, ruling out the possibility of an Fc-receptor mediated effect (Fig 1B and C).

Induction of chemokine release in NK cells by engagement of CD43. (A) Kinetics of the chemokine production induced by the pro-activatory anti-CD43 TP1/36 MoAb in NK cells. IL-2–activated NK cells were incubated in complete medium for different periods of time in the absence or presence of anti-CD43 TP1/36 MoAb (5 μg/mL). Cell supernatants were then assayed for different chemokines as described in Materials and Methods. This is a representative experiment of 2 independent experiments. (B) Secretion of RANTES and MIP-1β by NK cells stimulated with different MoAb. IL-2–activated NK cells were incubated in complete medium for 4 hours in the absence or the presence of the following MoAbs (5 μg/mL): anti-CD44 (HP2/9, IgG1); anti-CD43 (TP1/36 and HP2/21, IgG1 and IgM, respectively); and anti-CCR5 (IgM). Chemokines present in cell supernatants were then measured as described in Materials and Methods. In the absence of NK cells, the presence of chemokines was undetectable in complete medium (medium). The arithmetic mean ± SE of 6 independent experiments performed with cells from 6 different donors are shown. (C) The divalent F(ab′)2fragments of anti-CD43 MoAb induce RANTES and MIP-1β production in NK cells. IL-2–activated NK cells were allowed to adhere on dishes precoated with saturating concentrations of different MoAbs for 4 hours in complete medium. Chemokines present in cell supernatants were then measured. Chemokines were undetectable in complete medium (medium). The arithmetic mean ± SE of 3 experiments performed with cells from different donors are shown.

Induction of chemokine release in NK cells by engagement of CD43. (A) Kinetics of the chemokine production induced by the pro-activatory anti-CD43 TP1/36 MoAb in NK cells. IL-2–activated NK cells were incubated in complete medium for different periods of time in the absence or presence of anti-CD43 TP1/36 MoAb (5 μg/mL). Cell supernatants were then assayed for different chemokines as described in Materials and Methods. This is a representative experiment of 2 independent experiments. (B) Secretion of RANTES and MIP-1β by NK cells stimulated with different MoAb. IL-2–activated NK cells were incubated in complete medium for 4 hours in the absence or the presence of the following MoAbs (5 μg/mL): anti-CD44 (HP2/9, IgG1); anti-CD43 (TP1/36 and HP2/21, IgG1 and IgM, respectively); and anti-CCR5 (IgM). Chemokines present in cell supernatants were then measured as described in Materials and Methods. In the absence of NK cells, the presence of chemokines was undetectable in complete medium (medium). The arithmetic mean ± SE of 6 independent experiments performed with cells from 6 different donors are shown. (C) The divalent F(ab′)2fragments of anti-CD43 MoAb induce RANTES and MIP-1β production in NK cells. IL-2–activated NK cells were allowed to adhere on dishes precoated with saturating concentrations of different MoAbs for 4 hours in complete medium. Chemokines present in cell supernatants were then measured. Chemokines were undetectable in complete medium (medium). The arithmetic mean ± SE of 3 experiments performed with cells from different donors are shown.

We next assessed the possible effect of the anti-CD43 MoAb TP1/36 on the cytotoxic activity of NK cells. IL-2–activated NK cells treated with the anti-CD43 MoAb showed a significant increase of cytotoxic activity. Similarly to the chemokine production response, the increase in NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity triggered by anti-CD43 varied among donors (Fig 2). Control isotype-matched MoAb did not modify the cytotoxic activity of effector NK cells (Fig2). These data further indicate that CD43 functions as a stimulatory molecule in NK cells.

Enhancement of NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity by engagement of CD43. Effect of the proactivatory anti-CD43 TP1/36 MoAb and the control isotype-matched anti-CD56 K218 MoAb in the cytolytic activity of IL-2–cultured NK cells against P815 target cells. NK killing was determined in a 4-hour 51Cr release assay, as described in Materials and Methods. The arithmetic mean ± SE of 3 different experiments corresponding to 3 independent donors is shown. The differences were significant according to Student’st-test (P < .05).

Enhancement of NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity by engagement of CD43. Effect of the proactivatory anti-CD43 TP1/36 MoAb and the control isotype-matched anti-CD56 K218 MoAb in the cytolytic activity of IL-2–cultured NK cells against P815 target cells. NK killing was determined in a 4-hour 51Cr release assay, as described in Materials and Methods. The arithmetic mean ± SE of 3 different experiments corresponding to 3 independent donors is shown. The differences were significant according to Student’st-test (P < .05).

CD43-mediated signaling involves the activation of protein tyrosine kinases.

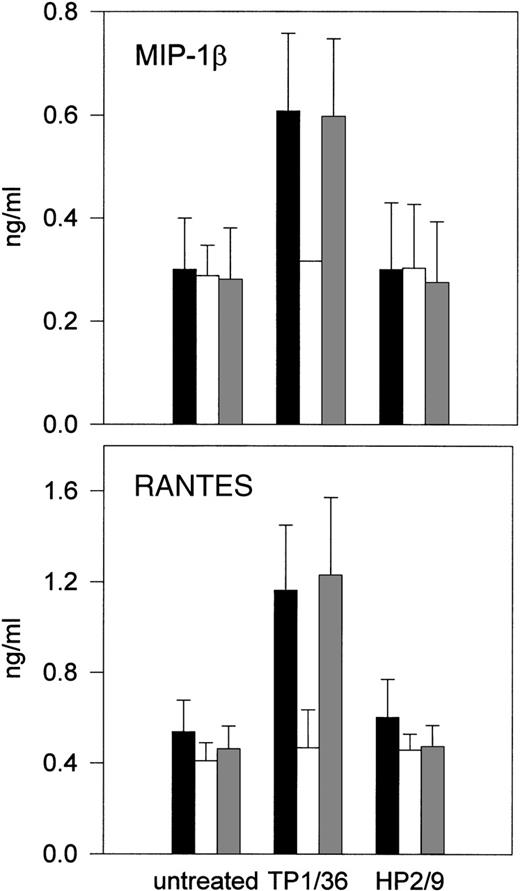

Positive regulation of NK cell activity involves protein kinase activation.2-4 To examine the possible involvement of protein tyrosine kinases in the signals triggered by CD43, NK cells were pretreated with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein55 before stimulation with anti-CD43 MoAb, and then chemokines released were quantitated in cell supernatants. As shown in Fig 3, CD43-induced production of RANTES and MIP-1β was abolished by genistein, suggesting that genistein-sensitive tyrosine kinases are required for signaling through CD43 in NK cells.

Effect of genistein on CD43-induced chemokine production and NK cell cytotoxicity. (A and B) IL-2–activated NK cells were incubated for 1 hour in (▪) complete medium or complete medium in the presence of (□) 30 μmol/L genistein or an equivalent amount of (▩) disolvent dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Anti-CD43 TP1/36 or anti-CD44 HP2/9 MoAbs were then added and cells were incubated for additional 4 hours. Chemokines present in cell supernatants were measured as described above. The arithmetic mean ± SE of 3 experiments performed with cells from different donors is shown.

Effect of genistein on CD43-induced chemokine production and NK cell cytotoxicity. (A and B) IL-2–activated NK cells were incubated for 1 hour in (▪) complete medium or complete medium in the presence of (□) 30 μmol/L genistein or an equivalent amount of (▩) disolvent dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Anti-CD43 TP1/36 or anti-CD44 HP2/9 MoAbs were then added and cells were incubated for additional 4 hours. Chemokines present in cell supernatants were measured as described above. The arithmetic mean ± SE of 3 experiments performed with cells from different donors is shown.

Engagement of CD43 induces activation of the PYK-2 tyrosine-kinase in NK cells.

We next examined the effect of anti-CD43 TP1/36 MoAb on the tyrosine kinase activities present in NK cells. Cells plated on dishes coated with the anti-CD43 MoAb TP1/36 were allowed to attach for different times and then lysed. Tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins were immunoprecipitated from the cell lysates with the MoAb PY20, and the resulting immunocomplexes were incubated with [32P]-γ-ATP and then analyzed by SDS-PAGE. As shown in Fig 4A, we observed a time-dependent phosphorylation of proteins in the molecular weight (Mr) of 110 to 80 kD and in the 48 to 83 kD range (Fig 4A, left panel).

Time-course of CD43-induced tyrosine kinase activity and presence of PYK-2 in anti-Tyr (P) immunoprecipitates. (A) NK cells were allowed to adhere for the indicated times on dishes precoated with the anti-CD43 TP1/36 MoAb. The cells were then lysed and the extracts were immunoprecipitated (IP) with the PY20 anti-Tyr(P) MoAb [IP: Tyr (P)], and kinase reactions performed as described in Materials and Methods (left panel). After the kinase reaction was performed, the major Tyr (P)-labeled bands in the cells stimulated for 60 minutes were eluted from the PY20 immunocomplex by boiling the pellet in 100 μL of a solution containing 10 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.4, and 1% SDS. Denaturated Tyr(P) proteins were then reimmunoprecipitated (r-IP) with the C-19 anti–PYK-2 antibody to confirm the presence of PYK-2 [IP: Tyr(P); r-IP: PYK-2] or with nonimmune serum control [IP: Tyr (P); r-IP: IgG; right panel]. After SDS-PAGE (7.5%) of immunoprecipitates, gels were subjected to autoradiography. The position of the major phosphorylated bands in the gel is indicated with arrowheads. PYK-2 position is indicated by an arrow. Molecular weight markers (in kilodaltons) are shown on the left side of the figure. (B) Cells were lysed and the extracts were incubated with C-19 antibody to immunoprecipitate PYK-2. Tyrosine phosphorylation levels of PYK-2 were determined by Western blot analysis with the PY20 anti-Tyr (P) MoAb.

Time-course of CD43-induced tyrosine kinase activity and presence of PYK-2 in anti-Tyr (P) immunoprecipitates. (A) NK cells were allowed to adhere for the indicated times on dishes precoated with the anti-CD43 TP1/36 MoAb. The cells were then lysed and the extracts were immunoprecipitated (IP) with the PY20 anti-Tyr(P) MoAb [IP: Tyr (P)], and kinase reactions performed as described in Materials and Methods (left panel). After the kinase reaction was performed, the major Tyr (P)-labeled bands in the cells stimulated for 60 minutes were eluted from the PY20 immunocomplex by boiling the pellet in 100 μL of a solution containing 10 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.4, and 1% SDS. Denaturated Tyr(P) proteins were then reimmunoprecipitated (r-IP) with the C-19 anti–PYK-2 antibody to confirm the presence of PYK-2 [IP: Tyr(P); r-IP: PYK-2] or with nonimmune serum control [IP: Tyr (P); r-IP: IgG; right panel]. After SDS-PAGE (7.5%) of immunoprecipitates, gels were subjected to autoradiography. The position of the major phosphorylated bands in the gel is indicated with arrowheads. PYK-2 position is indicated by an arrow. Molecular weight markers (in kilodaltons) are shown on the left side of the figure. (B) Cells were lysed and the extracts were incubated with C-19 antibody to immunoprecipitate PYK-2. Tyrosine phosphorylation levels of PYK-2 were determined by Western blot analysis with the PY20 anti-Tyr (P) MoAb.

PYK-2 has been recently identified as a 115-kD tyrosine kinase homologous to FAK that is expressed in different cell types, including NK cells.36-38 56 A protein band displaying an Mr equal to that of PYK-2 was among the phosphorylated proteins present in the lysates stimulated with the anti-CD43 TP1/36 MoAb. To determine whether PYK-2 was a component of the Mr 110- to 180-kD bands in the PY20 immune complexes, parallel cultures of NK cells were treated with the anti-CD43 MoAb for 45 minutes, in vitro kinase analysis was performed, and [32P]-labeled phosphotyrosinated proteins were eluted from the complexes by denaturation and then reimmunoprecipitated with the anti–PYK-2 polyclonal antibody. The results shown in Fig 4A (right panel) demonstrate that PYK-2 is a constituent of the Mr 110- to 180-kD Tyr (P) bands induced after engagement of CD43. We confirmed by Western blotting that CD43 induces tyrosine phosphorylation of PYK-2. Lysates obtained from cells that were plated on dishes coated with the anti-CD43 TP1/36 MoAb for different times were immunoprecipitated with the C-19 anti–PYK-2 antibody and tyrosine phosphorylation of PYK-2 was determined by immunoblotting using the MoAb PY20. As shown in Fig 4B, tyrosine phosphorylation of PYK-2 increased gradually, reaching a maximum after 60 minutes of CD43 stimulation.

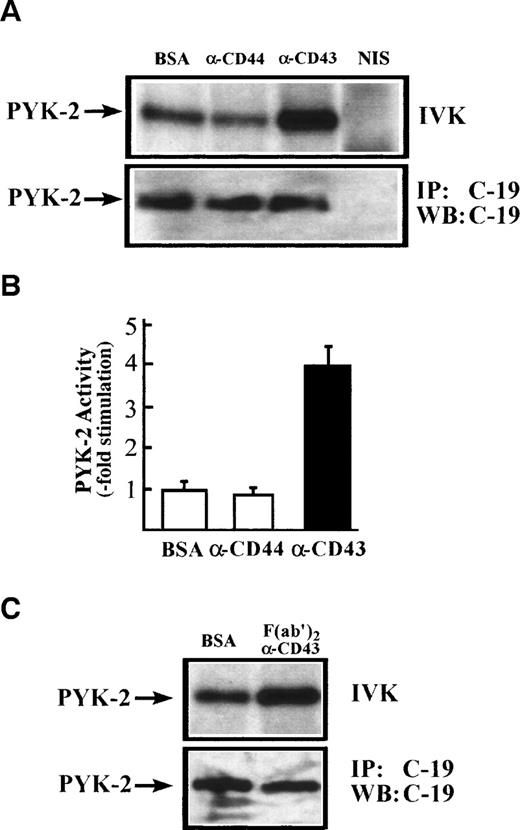

To confirm directly that CD43 stimulates PYK-2 activity, NK cells were incubated for 60 minutes on dishes coated with the anti-CD43 MoAb TP1/36. Cells were then lysed and immunoprecipitated with the C-19 anti–PYK-2 polyclonal antibody. PYK-2 immunoprecipitates were incubated with [32P]-γ-ATP and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. As shown in Fig 5A, CD43 induced an increase in the PYK-2 autokinase activity. F(ab′)2 of anti-CD43 TP1/36 MoAb also induced a similar activation PYK-2 (Fig 5C). The increase in PYK-2 phosphorylation of activity was not observed when NK cells were plated on dishes precoated with the nonstimulating isotype control anti-CD44 MoAb HP2/9 or when NK cells were incubated with conditioned medium obtained from cells plated on TP1/36 MoAb-coated dishes for 60 minutes, ruling out an autocrine loop in the activation of PYK-2 (Fig 5A and data not shown). Immunoblotting with anti–PYK-2 C-19 antibody immunoprecipitates performed in parallel verified that similar amounts of PYK-2 were recovered after stimulation with anti-CD43 MoAbs or its F(ab′)2 fragments (Fig 5A and C; IP: C-19; WB: C-19). Densitometric scanning showed that anti-CD43 MoAb TP1/36 induced a 4- ± 0.5-fold increase (n = 5) in the phosphorylation level of PYK-2 (Fig 5B).

CD43-induced stimulation of PYK-2 tyrosine kinase activity. (A) NK cells were allowed to adhere for 60 minutes, on dishes precoated with BSA, with the HP 2/9 anti-CD44 MoAb, TP 1/36 anti-CD43 MoAb, or TP1/36 F(ab′)2 fragments. Cells were then lysed and the extracts were incubated with C-19 antibody to immunoprecipitate PYK-2 (C-19) or with nonimmune serum (NIS) control and in vitro kinase reactions, performed as described in Materials and Methods (IVK, top). PYK-2 levels were determined by immunoprecipitation with the C-19 anti-PYK-2 antibody and Western blot analysis with C-19 anti–PYK-2 antibody (IP: C-19; WB: C-19; bottom). The position of PYK-2 is indicated with an arrow. (B) Quantification by densitometric scanning of the effect of stimulation with BSA, anti-CD44, and anti-CD43 on PYK-2 activity. PYK-2 was immunoprecipitated with the C-19 antibody and in vitro kinase reactions performed as described in Materials and Methods. Values are the mean± SEM of 5 independent experiments and are expressed as fold-stimulation above control. (C) NK cells were allowed to adhere for 60 minutes on dishes precoated with BSA or TP1/36 F(ab′)2 fragments. Cells were then lysed and processed as described above.

CD43-induced stimulation of PYK-2 tyrosine kinase activity. (A) NK cells were allowed to adhere for 60 minutes, on dishes precoated with BSA, with the HP 2/9 anti-CD44 MoAb, TP 1/36 anti-CD43 MoAb, or TP1/36 F(ab′)2 fragments. Cells were then lysed and the extracts were incubated with C-19 antibody to immunoprecipitate PYK-2 (C-19) or with nonimmune serum (NIS) control and in vitro kinase reactions, performed as described in Materials and Methods (IVK, top). PYK-2 levels were determined by immunoprecipitation with the C-19 anti-PYK-2 antibody and Western blot analysis with C-19 anti–PYK-2 antibody (IP: C-19; WB: C-19; bottom). The position of PYK-2 is indicated with an arrow. (B) Quantification by densitometric scanning of the effect of stimulation with BSA, anti-CD44, and anti-CD43 on PYK-2 activity. PYK-2 was immunoprecipitated with the C-19 antibody and in vitro kinase reactions performed as described in Materials and Methods. Values are the mean± SEM of 5 independent experiments and are expressed as fold-stimulation above control. (C) NK cells were allowed to adhere for 60 minutes on dishes precoated with BSA or TP1/36 F(ab′)2 fragments. Cells were then lysed and processed as described above.

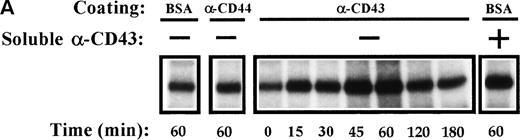

Kinetic studies of CD43-induced activation of PYK-2 showed that the increase in the autokinase activity of PYK-2 reached a maximum after 45 to 60 minutes, returning to basal levels after 180 minutes. When soluble anti-CD43 MoAb was added directly to the cell suspension, it was also able to induce activation of PYK-2 (Fig 6A and B). Taken together, these results show that engagement of CD43 increases the phosphotyrosine kinase activity of PYK-2.

Time-course of CD43-stimulated PYK-2 activity in NK cells. (A) NK cells were either plated on dishes coated with BSA (BSA), HP 2/9 anti-CD44 MoAb (-CD44), and anti-CD43 MoAb TP1/36 (-CD43) or plated on dishes coated with BSA and stimulated with soluble anti-CD43 MoAb (soluble -CD43). The cells were allowed to adhere for the indicated times and lysed. Lysates were incubated with the C-19 antibody to immunoprecipitate PYK-2 and activities in the resulting immunoprecipitates were measured by in vitro kinase reactions, as described in Materials and Methods. A representative experiment of 3 is shown. (B) Quantification by densitometric scanning of the effect of stimulation with anti-CD43 on PYK-2 activity. PYK-2 was immunoprecipitated with the C-19 antibody and in vitro kinase reactions performed as described in Materials and Methods. (s) -CD43 indicates soluble antibody. Values are the mean ± SE of 3 independent experiments and are expressed as fold-stimulation above control.

Time-course of CD43-stimulated PYK-2 activity in NK cells. (A) NK cells were either plated on dishes coated with BSA (BSA), HP 2/9 anti-CD44 MoAb (-CD44), and anti-CD43 MoAb TP1/36 (-CD43) or plated on dishes coated with BSA and stimulated with soluble anti-CD43 MoAb (soluble -CD43). The cells were allowed to adhere for the indicated times and lysed. Lysates were incubated with the C-19 antibody to immunoprecipitate PYK-2 and activities in the resulting immunoprecipitates were measured by in vitro kinase reactions, as described in Materials and Methods. A representative experiment of 3 is shown. (B) Quantification by densitometric scanning of the effect of stimulation with anti-CD43 on PYK-2 activity. PYK-2 was immunoprecipitated with the C-19 antibody and in vitro kinase reactions performed as described in Materials and Methods. (s) -CD43 indicates soluble antibody. Values are the mean ± SE of 3 independent experiments and are expressed as fold-stimulation above control.

DISCUSSION

We provide evidence here suggesting that CD43 positively regulates NK cell activity through phosphorylation signals. In addition, we have investigated the involvement of the protein tyrosine kinase PYK-2 in this signaling pathway. Despite the fact that a definitively confirmed ligand for CD43 is still lacking and its controversial function as an adhesion molecule, our data further support the role of this receptor as an accessory molecule in lymphocytes. In this regard, we have explored different aspects of the activation events triggered by CD43 in NK cells. Our results show that engagement of CD43 induces the augmented secretion of chemokines. This effect appeared to be independent of homotypic cell aggregation triggered by the anti-CD43 MoAb,28 as demonstrated by the results obtained with antibody-coated dishes, in which cells adhere and do not aggregate. This fact allows us to rule out the possibility of an activation effect as a consequence of cell-cell interactions.

Chemokines have been shown to be major factors regulating the directed migration of leukocytes, including NK cells, in inflammation and immunity.57-59 In addition, it has been described that chemokines stimulate Ca2+ mobilization and cytolytic granule release, promote cytotoxic activity, and regulate the adhesiveness of NK cells.51,52 We have previously reported that chemokine secretion by NK cells is dramatically increased by contact with target cells and that the release of these soluble factors induces the chemotaxis of additional NK cells. This suggests that chemokines may function by amplifying the immune response at sites of NK cell activation.43 It is therefore conceivable that the chemokines RANTES, MIP1-α, and MIP-1β, released upon activation through CD43, may increase the cytotoxic activity of NK cells at the targeted tissue and may direct the migration of other neighboring NK cells towards the target cells. In addition, these chemokines may contribute to modulate the function of other leukocytes. In this regard, it is worth mentioning that, in addition to its cytotoxic activity, growing evidence points to the role of NK cells as regulators of the immune response.46

The role of CD43 as a positive modulator of NK cell function was further reinforced by our finding that engagement of this receptor increases the cytotoxic activity of NK cells. Furthermore, CD43 induced phosphorylation and activation of tyrosine kinase proteins that are thought, in general, to transduce the positive signals that trigger the cytotoxic process. We have analyzed in detail some of the molecular components of the phosphorylation pathways triggered through CD43. PYK-2 was among the tyrosine kinases that became activated. PYK-2 is a member of the FAK nonreceptor tyrosine kinase family expressed by different cell types, including brain cells, platelets, and other hematopoietic cells. The cascade of signaling events that trigger PYK-2 activation includes various stimuli that elevate intracellular calcium or induce PKC activation.36,37 Hence, a possible linkage between CD43 engagement and PYK-2 activation could be established, because it has been reported that ligation of CD43 induces PKC activation.33 Nevertheless, it should be taken into account that PYK-2 tyrosine phosphorylation can be mediated via different pathways in various cell sytems. The Src tyrosine kinase Fyn has been reported to selectively phosphorylate PYK-2 in T cells. This phosphorylation does not depend on intracellular Ca2+.60 Fyn, which associates with the cytoplasmic tail of CD43,34 could be another candidate for the molecule responsible for the phosphorylation and activation of PYK-2 triggered through CD43.

The precise role of PYK-2 in the activation of NK cells through CD43 currently remains unknown. The homology sequence between FAK and PYK-2 seems to correspond to the functions that these two PTKs perform in the cell, although the exact role of PYK-2 may differ depending on the cell type.38 In this regard, studies using FAK− mutant mice have shown that expression of PYK-2 is induced in fibroblasts from these mice and that this expression counterbalances FAK signaling functions triggered by β1 integrins.61 This suggested that the expression of both proteins is regulated in a mutually exclusive fashion and that they might undertake similar functions in the cell. Nevertheless, as occurs with FAK, PYK-2 is best known for its functional association to β1, β2, and β3 integrins and its activation upon interaction of these adhesion receptors with their ligands.56,62,63 Recently, it has been described that NK cells express PYK-2, but not FAK, and that outside-in signaling triggered by β1 integrin receptors stimulates PYK-2 activation.56 Moreover, the constitutive association of PYK-2 to paxillin, a cytoskeletal protein that is also associated to pp125FAK, and to other proteins present in focal adhesions such as vinculin has been recently reported.56,64 Integrins are two-way signaling receptors, and it is therefore feasible that PYK-2, as occurs with different second-messengers and mediators involved in the outside-in integrin signaling, may also participate in transducing signals from inside the cell to the exterior. The possibility that CD43-mediated activation of PYK-2 may regulate integrin affinity must be taken into account, because CD43 has been reported to regulate β1 and β2 integrin-mediated lymphocyte adhesion,28 a phenomenon that may lead to an increase in the cytotoxic activity of NK cells.

Nevertheless, it is also feasible that PYK-2 may function independently of integrin receptors and participates in other different signaling events during CD43-induced activation. Hence, PYK-2 phosphorylation has been involved in other processes, such as the signal events triggered by the interaction of CCR5 with either the chemokine RANTES or the HIV envelope protein gp120, the stress signals, or cytokine signaling.65-67 Interestingly, different reports have shown that engagement of the T-cell receptor triggers PYK-2 activation, which is selectively phosphorylated by Fyn, and the association of PYK-2 to Lck.60,68 69

Our results add novel elements to the range of protein kinases that participate in the positive regulation of NK cell activity. It is clear that the function of NK cells is modulated by the interplay between negative and positive signals within the cell. Membrane receptors as well as the signaling pathways involved in the activation of NK cells have not been studied to the same extent as the inhibitory receptors that provide specific recognition.2-4 The CD16 molecule functions as a prototype activating receptor in NK cells, and the signaling through this molecule has been extensively investigated (reviewed in Lanier2 and Yokoyama4). Engagement of CD16 triggers recruitment of tyrosine kinase of the src-family and tyrosine phosphorylation of residues contained within the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based motifs (ITAMs) in the cytoplasmic domains of CD16-associated zeta and gamma chains, followed by activation of ZAP-70, activation of phospholipase C, and the MAP kinase activation pathway. As occurs with CD43, ligation of CD16 stimulates cytokine production.70 These findings, together with the fact that CD43 has been reported to be associated to the Src family tyrosine kinase Fyn,34 suggest that the activation pathway triggered by these two receptors, as well as by other positive modulators of NK cell activity, may share more common elements. Therefore, it is likely that CD16 receptor triggers PYK-2 phosphorylation. However, this issue requires further investigation. It is therefore feasible that signals triggered by positive regulators of NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity may converge in a common signaling pathway. This activatory cascade of signals may be induced by different receptors depending on the type of NK cell cytotoxicity (ie, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity or MHC-recognition regulated killing). Triggering of this cascade by CD43, as well as by other costimulatory receptors, such as CD16, may serve to augment the primary activation of NK cells through specific MHC receptors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Dr Miguel López-Botet for critical reading of the manuscript.

Supported by Grants No. SAF 99/0034 and 2FD97-0680-C02-02 from the Ministerio de Educación y Cultura, Grants No. 07/44/96 (to F.S.-M.) and 08.1/0015/97 (to C.C.) from the Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid, a grant from “Fundación Cientifica de la Asociación Española contra el Cáncer” (to F.S.-M. and C.C.), Grant No. SAF 98/0080 (to C.C.), and by fellowships from the Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias BAE 97/5089 (to M.N.). J.L.R.-F. was supported by a “Contrato de Reincorporación” associated to Grants No. PB94-0231 and SAF98/0080, awarded by the “Ministerio Español de Educación y Cultura.” The Department of Immunology and Oncology was founded and is supported by the CSIC, Pharmacia, and Upjohn.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Francisco Sánchez-Madrid, PhD, Servicio de Inmunologı́a, Hospital de la Princesa, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Diego de León 62, E-28006, Madrid, Spain; e-mail: fsmadrid/princesa@hup.es.

![Fig. 4. Time-course of CD43-induced tyrosine kinase activity and presence of PYK-2 in anti-Tyr (P) immunoprecipitates. (A) NK cells were allowed to adhere for the indicated times on dishes precoated with the anti-CD43 TP1/36 MoAb. The cells were then lysed and the extracts were immunoprecipitated (IP) with the PY20 anti-Tyr(P) MoAb [IP: Tyr (P)], and kinase reactions performed as described in Materials and Methods (left panel). After the kinase reaction was performed, the major Tyr (P)-labeled bands in the cells stimulated for 60 minutes were eluted from the PY20 immunocomplex by boiling the pellet in 100 μL of a solution containing 10 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.4, and 1% SDS. Denaturated Tyr(P) proteins were then reimmunoprecipitated (r-IP) with the C-19 anti–PYK-2 antibody to confirm the presence of PYK-2 [IP: Tyr(P); r-IP: PYK-2] or with nonimmune serum control [IP: Tyr (P); r-IP: IgG; right panel]. After SDS-PAGE (7.5%) of immunoprecipitates, gels were subjected to autoradiography. The position of the major phosphorylated bands in the gel is indicated with arrowheads. PYK-2 position is indicated by an arrow. Molecular weight markers (in kilodaltons) are shown on the left side of the figure. (B) Cells were lysed and the extracts were incubated with C-19 antibody to immunoprecipitate PYK-2. Tyrosine phosphorylation levels of PYK-2 were determined by Western blot analysis with the PY20 anti-Tyr (P) MoAb.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/94/8/10.1182_blood.v94.8.2767.420k26_2767_2777/7/m_blod42026004w.jpeg?Expires=1767737781&Signature=0AtGiNZ78WeEa4hEjHsGVcYmBgI5levwXREDQJHkID~DES-eHOfiGPpk7zK50rJlKAKmpuaxfSQDrKwSPhXhfaKL7PMmbTfK6AVwUV3RU~-0zKu5wXEFhi7By6KwJBKFYpNnXXptHBd9mMq1Vluy7Zkjf3t8jNSMKrxuK0Loa9JmmS~uR~91atnw1ftIqooMiKFPyRyYg5WfRj-GIDO0N9CtEBh1zU0L6iMHHaxt9C1fcXedoFN~W~5XeUTSATztYf~WhAHRu-R8zrW7KxEu~nfMcI2-Qyr-5f4mrZV6OTppQJ62-yDB8Ooeus6UiW8ry5cKOAQVsoD6e67YXqjW-g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal