Abstract

Secondary myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) have been reported after autologous transplantation. It is not known whether the MDS results from the pretransplant conventional-dose chemotherapy or from the high-dose chemotherapy (HDC) used for the transplant procedure. We performed a multicenter, retrospective analysis of morphologically normal pretransplant marrow or stem cell specimens from 12 patients who subsequently developed myelodysplasia after HDC. To determine if the abnormal clone was present before HDC, we used fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to detect the cytogenetic markers observed at the onset of posttransplant MDS. Cryopreserved, pretransplant bone marrow, peripheral blood stem cell specimens, obtained at the time of harvest, or archival smears were used. Standard cytogenetic analysis had been performed pretransplant in four patients, showing a normal karyotype. In 9 of 12 cases, the same cytogenetic abnormality observed at the time of MDS diagnosis was detected by FISH in the pre-HDC specimens. Our findings support the hypothesis that, in many cases of posttransplant MDS, the stem cell damage results from prior conventional-dose chemotherapy and may be unrelated to HDC or the transplantation process itself.

MYELODYSPLASTIC syndromes (MDS) are a heterogeneous group of hematologic disorders characterized by peripheral cytopenias associated with ineffective hematopoiesis in the bone marrow.1 The illnesses can be primary (de novo) or develop secondarily in patients previously treated for malignant and nonmalignant disorders with cytotoxic agents, particularly alkylating agents2,3 and/or radiotherapy.4,5 In the last 10 years, high-dose chemotherapy (HDC) followed by autologous bone marrow transplantation (ABMT) or peripheral blood stem cell transplantation (PBSCT) has been used with increasing frequency for the treatment of both hematologic malignancies and solid tumors.6,7 Secondary MDS are well-known complications of antineoplastic therapy8,9 and recently have been described with an increasing incidence after autologous transplantation.10,11 It is not clear, however, whether the stem cell damage leading to MDS is already present in pretransplant hematopoietic progenitors, and probably caused by pretransplant conventional-dose chemotherapy or if it arises during or after the HDC used for the transplant procedure.12 13

To address this question, we studied pretransplant marrow or stem-cell specimens from 12 patients who had received HDC with autologous marrow or stem cell transplantation for the treatment of a lymphoma or solid tumor and have subsequently developed posttransplant MDS. Posttransplant bone marrow specimens obtained from all patients at the time of MDS diagnosis exhibited 1 or more MDS-related cytogenetic abnormalities. These posttransplant cytogenetic abnormalities were used as markers to determine retrospectively, by using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), whether the abnormal MDS clone was present in pretransplant marrow or peripheral blood stem cell specimens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient eligibility.

Patients were identified retrospectively from the Bone Marrow Transplantation Databases of the three institutions participating in the study. Patients eligible for study met the following criteria:

- (1)

They had undergone HDC with bone marrow and/or stem cell rescue for the treatment of Hodgkin’s or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) or solid malignancy. Patients transplanted for leukemia or myeloid disorders were excluded from the study.

- (2)

Morphologic examination of bone marrow aspirates and core biopsies performed before transplant had not shown any dysplastic changes or evidence of the primary malignancy.

- (3)

They had developed posttransplant MDS, diagnosed according to French-American-British (FAB) criteria.14

- (4)

Bone marrow specimens obtained at the time of diagnosis of posttransplant MDS exhibited 1 or more MDS-related15cytogenetic abnormalities for which a FISH probe was available.

- (5)

Pretransplant bone marrow or stem cell specimens were available for analysis, in the form of cryopreserved cells or archival marrow smears.

Cytogenetic analysis.

Standard G-banding cytogenetic technique was performed on direct preparations and short-term unstimulated cultures of fresh or thawed heparinized bone marrow. Karyotypes were designated according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature.16

Molecular cytogenetic (FISH) analysis.

In 8 cases, cryopreserved, pretransplant marrow or stem cell specimens were available for analysis. These were thawed and prepared (uncultured) for interphase FISH analysis after standard molecular cytogenetic techniques, including a 20-minute incubation at 37°C in hypotonic solution (0.075 mol/L KCl) and fixing in methanol/acetic acid 3:1. One or more slides were prepared per patient and per cytogenetic abnormality. Cells were then denatured for 3 minutes at 73°C in 70% formamide/2× SSC and dehydrated in an ethanol series. In 4 cases, analysis was performed on archived pretransplant bone marrow smears. After hematologic analysis, coverslips from Wright-Giemsa-stained bone marrow smears were flipped up by immersing the slides in liquid nitrogen. Slides were dipped in xylene at room temperature for 30 minutes to clear the mounting medium as previously described.17

Hybridization was performed with standard FISH protocols. To reduce cell loss during the procedure, bone marrow slides were processed by using the HYBrite System (VYSIS, Downers Grove, IL) following the manufacturer’s directions. The FISH probes used were chosen depending on the cytogenetic abnormalities found in posttransplant marrows and obtained from VYSIS. The probes used for this study included LSI EGR-1 (5q31) and centromeric probes CEP 7, CEP 8, CEP11, and CEP 21 (Spectrum Orange direct labeled). DAPI counterstain was used for detection.

Cytogenetically normal samples were used as controls for each probe, following the same hybridization procedure. Two hundred cells per slide were examined by 2 independent observers for each patient, and the results reported as a mean of these determinations. A conservative threshold of 10% abnormal cells was established; any specimens below 10% were considered to be negative for presence of the clonal abnormality.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics.

Twelve patients met the criteria for study. The median age at the time of transplant was 38 years (range, 25 to 65 years), with 5 males and 7 females. Four patients were referred to transplant for breast cancer (BC), 4 for NHL, 3 for Hodgkin’s disease (HD), and 1 patient for melanoma. The majority of patients had received multiple cycles of chemotherapy and radiotherapy before HDC. Only 1 patient was transplanted at diagnosis, without prior chemotherapy or radiotherapy. HDC regimens varied and 3 patients received total body irradiation (TBI) together with HDC. The time from diagnosis to HDC ranged from 1 month to 96 (median, 33) months.

Posttransplant, 3 patients were diagnosed as having refractory anemia (RA), 1 RA with ringed sideroblasts, 6 RA with excess of blasts (RAEB), and 2 RA with excess of blasts in transformation (RAEB-t). The time between HDC and MDS diagnosis ranged from 10 to 60 (median, 38) months. The clinical characteristics and a summary of the pertinent patient data are presented in Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Pt No. . | Age . | Sex . | Diagnosis . | Pretransplant Therapy . | ΔT1 (mo) . | HDC . | ΔT2 (mo) . | MDS . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT . | CT . | TBI . | HDC . | |||||||

| 1 | 34 | M | HD | X | X | 30 | X | 57 | RAEB | |

| 2 | 46 | F | BC | X | 9 | X | 25 | RAEB-t | ||

| 3 | 25 | M | HD | X | X | 96 | X | 35 | RAEB | |

| 4 | 61 | M | NHL | X | X | 96 | X | 11 | RA | |

| 5 | 36 | F | HD | X | X | 39 | X | 44 | RA | |

| 6 | 34 | F | NHL | X | X | 84 | X | X | 60 | RAEB-t |

| 7 | 37 | M | M | 1 | X | 43 | RAEB | |||

| 8 | 38 | F | BC | X | X | 36 | X | 28 | RAEB | |

| 9 | 65 | F | BC | X | X | 24 | X | X | 41 | RAEB |

| 10 | 50 | F | NHL | X | X | 96 | X | X | 10 | RAEB |

| 11 | 47 | F | BC | X | X | 24 | X | 41 | RARS | |

| 12 | 66 | M | NHL | X | 15 | X | 18 | RA | ||

| Pt No. . | Age . | Sex . | Diagnosis . | Pretransplant Therapy . | ΔT1 (mo) . | HDC . | ΔT2 (mo) . | MDS . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT . | CT . | TBI . | HDC . | |||||||

| 1 | 34 | M | HD | X | X | 30 | X | 57 | RAEB | |

| 2 | 46 | F | BC | X | 9 | X | 25 | RAEB-t | ||

| 3 | 25 | M | HD | X | X | 96 | X | 35 | RAEB | |

| 4 | 61 | M | NHL | X | X | 96 | X | 11 | RA | |

| 5 | 36 | F | HD | X | X | 39 | X | 44 | RA | |

| 6 | 34 | F | NHL | X | X | 84 | X | X | 60 | RAEB-t |

| 7 | 37 | M | M | 1 | X | 43 | RAEB | |||

| 8 | 38 | F | BC | X | X | 36 | X | 28 | RAEB | |

| 9 | 65 | F | BC | X | X | 24 | X | X | 41 | RAEB |

| 10 | 50 | F | NHL | X | X | 96 | X | X | 10 | RAEB |

| 11 | 47 | F | BC | X | X | 24 | X | 41 | RARS | |

| 12 | 66 | M | NHL | X | 15 | X | 18 | RA | ||

Abbreviations: RT, radiotherapy; CT, chemotherapy; ΔT1, interval from diagnosis to HDC (months); ΔT2, interval from HDC to MDS diagnosis (months).

Cytogenetic analyses.

All the patients developed clonal karyotypic abnormalities posttransplant (Table 2). Many were complex, but all included aberrations associated with MDS, most commonly extra copies of chromosome 8 or deletions of all or parts of chromosomes 5 or 7. In 4 cases, standard cytogenetic analyses had been performed before transplantation and were normal.

Cytogenetic and FISH Analyses

| Pt No. . | Transplant Type . | Pretransplant Cytogenetics . | Posttransplant Cytogenetics (at time of MDS Diagnosis) . | FISH Marker . | Abnormal Cells Pre-HDC (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ABMT | Not done | 45,XY,t(5;11)(q31q13), −7, −11, +mar[13] | −7 | 35 |

| −11 | 46 | ||||

| 2 | PBSC | Not done | 45,XX, inv(3)(q21q27), −7 [20] | −7 | 30 |

| 3 | ABMT | Not done | 45,XY,del(3)(q21q25), −5,del(7)(q11.2q34), add(13)(p11.2), add(17)(q11.2), del(20)(q11.2), −21, −22, +mar,+r[4]/44, idem,−3 [2]/46,XY [2] | del(5)(q31) | 29 |

| 4 | ABMT | Not done | 46,XY, del(5)(q15q31) [5]/ 46,XY, del(5)(q11.2q35)[19]/45,XY add(7)(q11.2), −13 [2] | del(5)(q31) | 39 |

| 5 | ABMT | 46,XX[16] | 46,XX, +der(12)t(?;12) (12;11) (?p11.2q15q21) [17]/48,XX, +8, +8[3]/ 46,XX [4] | +8 | 6 |

| 6 | ABMT | Not done | 44,X, add(X)(q26), t(3;4)(p23;q14), −5, t(6;18)(p21;q12), −11, der(14)t(5;14) q11.2q33;p11),−16,−17, add(20)(q13), add(21)(q22), +mar,+dms [4]/46,X, add(X)(q26), del(1)(p22p32), t(3;4)(p23;p14), −5, t(6;18)(p21;q12), +8, −11, der(14)t(5;14)(q11.2q33;p11), −17, +add(20)(q13), add(21)(q22), +mar, +dms [5]/46,XX [11] | +8 | 20 |

| 7 | ABMT | 46,XY[20] | 47,XY,del(3)(q13q28),+8[20] | +8 | 5 |

| 8 | Purged ABMT | Not done | 45,XX,der(6)t(3;6)(q21;q15),−7[19]/ 46,XX[10] | −7 | 41 |

| 9 | ABMT | 46,XX[15] | 45,XX,−6,−21,+mar,[4]/ 46,idem,del(9)(q22)[16] | −21 | 11 |

| 10 | CD34 + PBSC | Not done | 45,XX,del(3)(p25p21),−5, add(7)(p15), del(9)(p13p24), −15,+mar[20] | del(5)(q31) | 5 |

| 11 | ABMT/PBSCT | Not done | 46,XX,del(5)(q31)[20] | del(5)(q31) | 23 |

| 12 | ABMT | 46,XY[20] | 45,XY,−3,−5,−6,add(6)(p21),−7,−15, +mar1, +mar2, +mar3, +mar4, +mar5[7]/ 45,Y,−X, add(1)(p34), −5, del(5)(q13q31),−6,−7,−8,−9, del(10)(p13), der(11)t(5;11) (q11.2;p15), add(16)(p13.1), +mar1, +mar2, +mar3, +mar4, +mar5[3]/ 46,XY[10] | del(5)(q31) −7 | 27 7 |

| Pt No. . | Transplant Type . | Pretransplant Cytogenetics . | Posttransplant Cytogenetics (at time of MDS Diagnosis) . | FISH Marker . | Abnormal Cells Pre-HDC (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ABMT | Not done | 45,XY,t(5;11)(q31q13), −7, −11, +mar[13] | −7 | 35 |

| −11 | 46 | ||||

| 2 | PBSC | Not done | 45,XX, inv(3)(q21q27), −7 [20] | −7 | 30 |

| 3 | ABMT | Not done | 45,XY,del(3)(q21q25), −5,del(7)(q11.2q34), add(13)(p11.2), add(17)(q11.2), del(20)(q11.2), −21, −22, +mar,+r[4]/44, idem,−3 [2]/46,XY [2] | del(5)(q31) | 29 |

| 4 | ABMT | Not done | 46,XY, del(5)(q15q31) [5]/ 46,XY, del(5)(q11.2q35)[19]/45,XY add(7)(q11.2), −13 [2] | del(5)(q31) | 39 |

| 5 | ABMT | 46,XX[16] | 46,XX, +der(12)t(?;12) (12;11) (?p11.2q15q21) [17]/48,XX, +8, +8[3]/ 46,XX [4] | +8 | 6 |

| 6 | ABMT | Not done | 44,X, add(X)(q26), t(3;4)(p23;q14), −5, t(6;18)(p21;q12), −11, der(14)t(5;14) q11.2q33;p11),−16,−17, add(20)(q13), add(21)(q22), +mar,+dms [4]/46,X, add(X)(q26), del(1)(p22p32), t(3;4)(p23;p14), −5, t(6;18)(p21;q12), +8, −11, der(14)t(5;14)(q11.2q33;p11), −17, +add(20)(q13), add(21)(q22), +mar, +dms [5]/46,XX [11] | +8 | 20 |

| 7 | ABMT | 46,XY[20] | 47,XY,del(3)(q13q28),+8[20] | +8 | 5 |

| 8 | Purged ABMT | Not done | 45,XX,der(6)t(3;6)(q21;q15),−7[19]/ 46,XX[10] | −7 | 41 |

| 9 | ABMT | 46,XX[15] | 45,XX,−6,−21,+mar,[4]/ 46,idem,del(9)(q22)[16] | −21 | 11 |

| 10 | CD34 + PBSC | Not done | 45,XX,del(3)(p25p21),−5, add(7)(p15), del(9)(p13p24), −15,+mar[20] | del(5)(q31) | 5 |

| 11 | ABMT/PBSCT | Not done | 46,XX,del(5)(q31)[20] | del(5)(q31) | 23 |

| 12 | ABMT | 46,XY[20] | 45,XY,−3,−5,−6,add(6)(p21),−7,−15, +mar1, +mar2, +mar3, +mar4, +mar5[7]/ 45,Y,−X, add(1)(p34), −5, del(5)(q13q31),−6,−7,−8,−9, del(10)(p13), der(11)t(5;11) (q11.2;p15), add(16)(p13.1), +mar1, +mar2, +mar3, +mar4, +mar5[3]/ 46,XY[10] | del(5)(q31) −7 | 27 7 |

FISH analyses.

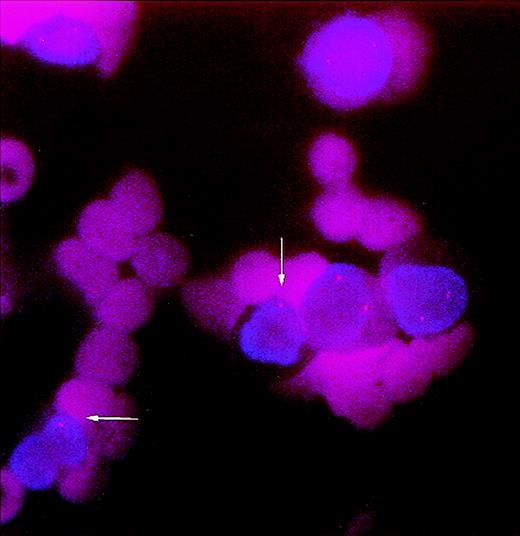

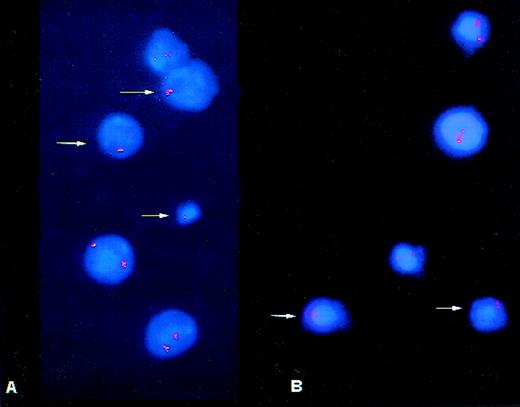

FISH analyses were performed on aliquots of cryopreserved, pretransplant bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cells obtained at the time of harvest (9 cases) or on archival smears of pretransplant bone marrow (4 cases), with the patient-specific probes listed in Table2 (Figs 1 and2).

Pretransplant bone marrow smear cells from patient no. 3 screened for del(5)(q31). Nucleated cells (2 of 6) show a single signal instead of the two normal signals indicating deletion 5q31 (arrows).

Pretransplant bone marrow smear cells from patient no. 3 screened for del(5)(q31). Nucleated cells (2 of 6) show a single signal instead of the two normal signals indicating deletion 5q31 (arrows).

A (left) neutrophil and an (right) erytroblast from pretransplant bone marrow smear of patient no. 6 showing trisomy 8.

A (left) neutrophil and an (right) erytroblast from pretransplant bone marrow smear of patient no. 6 showing trisomy 8.

In 9 of these 12 patients, the same cytogenetic abnormality(ies) identified by conventional cytogenetic analysis at the time of posttransplant MDS diagnosis was detected by FISH in pretransplant marrow or stem-cell specimens. The percentage of abnormal cells in the pretransplant specimens ranged from 11% to 46% (Fig 3, see page 1817). Two of these patients had 2 cytogenetic markers analyzed independently by FISH. In the case of patient no. 1, 46% and 35% of pretransplant exhibited monosomy 11 and monosomy 7, respectively (Fig 4). In the case of patient no. 12, 27% of pretransplant cells exhibited monosomy 5, although only 7% cells demonstrated monosomy 7. Three of these 9 patients had a normal karyotype in all metaphases examined pretransplant with standard cytogenetic analysis.

Percentage of cytogenetically abnormal cells in pretransplant specimens per marker studied. Two patients had 2 abnormalities analyzed by molecular cytogenetics. One patient presented with both abnormalities in pretransplant marrow, and the other patient had only 1 of the 2 abnormalities detected in a sufficient number of cells to be considered present pretransplant.

Percentage of cytogenetically abnormal cells in pretransplant specimens per marker studied. Two patients had 2 abnormalities analyzed by molecular cytogenetics. One patient presented with both abnormalities in pretransplant marrow, and the other patient had only 1 of the 2 abnormalities detected in a sufficient number of cells to be considered present pretransplant.

Cells from patient no. 1 harvest. Arrows indicate (A) monosomy 11 cells and (B) monosomy 7 cells.

Cells from patient no. 1 harvest. Arrows indicate (A) monosomy 11 cells and (B) monosomy 7 cells.

In the remaining 3 patients, the cytogenetic abnormalities identified at the time of posttransplant MDS diagnosis were not detected in pretransplant specimens in a sufficient number of cells to be considered positive. One of these, patient no. 7, had not received previous therapy for his primary malignancy; pretransplant cytogenetic studies were also normal in this case. Patient no. 5 had a complex karyotype; the marker studied with FISH (+8) was present in only 3 of 24 posttransplant metaphases by standard cytogenetic analysis. Patient no. 10 had initial cytogenetic analysis done at the time of posttransplant MDS diagnosis showing: 46,XX, del(3)(p25p21) [2]/46,XX, t(3;18)(q21q23) [2]/46,XX [16]. It was not possible to analyze these abnormalities by using interphase FISH. A second bone marrow sample was sent for cytogenetic analysis 9 months later showing: 46,XX, del(3)(p25p21), −5, add(6)(p21.3), add(7)(p15), del (9)(p13p24), −15, +mar [20]. FISH analysis of the pretransplant specimen was then performed by screening the cells for monosomy 5, which was identified in 5% of pretransplant cells.

DISCUSSION

Many previous studies have attempted to identify the mechanisms related to the onset of secondary leukemias (SL) and MDS after conventional-dose chemotherapy.18,19 Factors considered important in determining the onset of SL/MDS have been the intensity and timing of conventional-dose chemotherapy and the dose and the extent of radiation therapy. The most commonly reported cytogenetic abnormalities associated with therapy-related SL/MDS have been abnormalities of chromosomes 5, 7, and 11.20-22

Recent studies have examined the incidence of SL/MDS after HDC with marrow and/or stem cell rescue for hematologic and nonhematologic diseases.23-30 One large study reported an overall incidence for lymphoma patients of 5%, with an actuarial risk of developing SL/MDS of 2.6% at 5 years,27 in other studies, the cumulative risk has been as high as 15%.10 In his editorial, Stone12 commented that the interval between the conventional-dose therapy and the onset of MDS after HDC corresponded closely to the typically alkylating agent-related SL/MDS that develops in nontransplant settings. This, together with the extent of pretransplant conventional-dose chemotherapy received by the affected patients, led him to hypothesize that the pretransplant conventional-dose therapy was likely to be causative. However, no scientific data were available to confirm this hypothesis.

Chao et al28 described 7 patients considered for autologous transplantation for HD. Three had histologically normal bone marrows and underwent HDC. All 3 developed MDS at 9, 12, and 12 months posttransplant, respectively. In 2 of the 3 patients, retrospective analysis failed to showed cytogenetic abnormalities in the frozen marrow samples from the time of marrow harvest. In the other 4 patients, cytogenetic abnormalities were detected and the HDC was deferred. From these data, Chao et al28 suggested that SL/MDS may be related to pretransplant conventional-dose therapy and that standard cytogenetic analysis may not be sensitive enough to detect the abnormal clone.

Govindarajan et al29 compared 2 groups of myeloma patients. Group 1 had received limited alkylating-agent–based therapy before peripheral stem-cell mobilization. Group 2 had significantly more prolonged exposure to chemotherapy before mobilization. None of the patients in group 1 (71 patients; 39 months median follow-up) developed MDS as compared with 7 in group 2 (117 patients; 29 months median follow-up). The investigators suggested that the more extensive pretransplant treatment may have contributed to the posttransplant MDS.

More recently, Laughlin et al25 reported the cumulative incidence of posttransplant MDS in a series of BC patients treated with HDC was low (only 5 cases in 864 patients). More importantly, in all 4 cases studied, cytogenetic abnormalities were present posttransplant, and all 4 were cytogenetically normal pretransplant. The investigators concluded from these data that the HDC in these patients was likely the etiology for the development of the MDS. Similarly, Traweek et al30 noted that, among 275 patients undergoing autologous transplantation for HD or NHL, 10 with morphologically normal bone marrow and normal cytogenetic analysis immediately before transplantation subsequently developed clonal karyotypic abnormalities posttransplant. The investigators noted that the presence of normal chromosomes at the time of marrow harvest does not fully negate the risk of developing subsequent hematopoietic cell abnormalities.

However, an alternative interpretation, supported by our data, is that conventional cytogenetic analysis may be unable to detect the abnormal clone pretransplant as a result of a low sensitivity. The abnormal clone may not yet have acquired a growth advantage in the presymptomatic state and, therefore, may not grow well enough to be detected with standard metaphase techniques.

The use of clonal analysis of X-linked polymorphism may be useful in identifying an emerging clonal population in the bone marrow.31 This technique has been used to identify patients who are at risk of developing SL/MDS.32 Retrospective studies have showed the presence of clonal hematopoiesis in morphologically normal pretransplant marrow of some patients who developed MDS posttransplant.33 However, the technique can only be used in selected females and is not sensitive enough to detect clones that represent less than 30% to 40% of cells in the marrow population.

We identified 12 patients who were transplanted for lymphomas or solid tumors and had developed a secondary MDS post-HDC. All had an MDS-related cytogenetic abnormality at the time of the MDS diagnosis. Pretransplant marrows were examined by using molecular cytogenetics to determine whether the same cytogenetic abnormality that was found posttransplant was also present in presymptomatic, pretransplant marrow, or stem cells. FISH was chosen because of its ability to study interphase nuclei (thus, allowing analysis of both dividing and nondividing cells) and because of the greater sensitivity conferred by the ability to study a large number of cells. Pretransplant cells from 9 of 12 patients were found to contain the same MDS-related abnormalities identified at the time of diagnosis of posttransplant MDS. Of these patients, 3 had previously been studied with standard cytogenetic analysis and found to have normal karyotypes. These data support the hypothesis that the progenitor cell damage, which led to posttransplant MDS in these cases, antedated the HDC given in association with autologous transplantation.

In 3 of the 12 cases, the cytogenetic marker(s) found posttransplant were not found in pretransplant specimens. Patient no. 7 had not received any antineoplastic therapy for his melanoma before HDC and developed RAEB 43 months after transplantation that rapidly evolved into acute myeloid/myelogenous leukemia (FAB-M7). Pretransplant cytogenetics were also normal in this case. In patient no. 5, the cytogenetic abnormality analyzed (+8) was present only in a small percentage of cells posttransplant (3 of 24) and represented a subclone of the abnormal karyotype. As such, it may have been acquired late in the evolution of the clone, and it is possible that the original clone arose pretransplant but was not identified with the chromosome 8 probe. Similarly, in patient no. 10, the abnormality studied (monosomy 5) arose (by standard cytogenetic analysis) between the patient’s first and second posttransplant cytogenetic studies, again suggesting that it may have been acquired late in clonal evolution.

We conclude from these data that in many patients, the posttransplant MDS evolves from an abnormal clone that is present in the progenitor cells before autologous transplantation. If this proves to be true, this finding would have important implications for patients for whom HDC might be considered appropriate. If the stem cell damage leading to posttransplant MDS results from prior conventional-dose therapy, strategies intended to reduce the incidence of posttransplant MDS should focus on the conventional-dose therapy rather than on the HDC itself. Such strategies might include attempts to limit the dose and/or duration of therapy or the avoidance of alkylating agents during this phase of treatment. Alternatively, if molecular cytogenetic analysis can detect clonal abnormalities in pretransplant progenitor cells, then the focus could be on the use of selection technologies that can identify, isolate, and possibly permit expansion of unaffected progenitors.34 Prospective identification of such abnormalities before HDC would be limited by one’s inability to determine in advance the specific probe to use for a given patient. However, the use of a panel of probes for the common MDS abnormalities might be feasible, particularly in patients with substantial prior therapy and, therefore, might permit the prospective identification of patients at high risk for development of posttransplant MDS. Clinical trials of such strategies are warranted to determine if these approaches will reduce the incidence of MDS after autologous transplantation.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to David D. Hurd, MD, c/o Comprehensive Cancer Center, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Medical Center Blvd, Winston-Salem, NC 27157-1082; e-mail: dhurd@wfubmc.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal