To determine whether the multidrug resistance gene MDR1could act as a selectable marker in human subjects, we studied engraftment of peripheral blood progenitor cells (PBPCs) transduced with either MDR1 or the bacterial NeoR gene in six breast cancer patients. This study differed from previous MDR1 gene therapy studies in that patients received only PBPCs incubated in retroviral supernatants (no nonmanipulated PBPCs were infused), transduction of PBPCs was supported with autologous bone marrow stroma without additional cytokines, and a control gene (NeoR) was used for comparison with MDR1. Transduced PBPCs were infused after high-dose alkylating agent therapy and before chemotherapy with MDR-substrate drugs. We found that hematopoietic reconstitution can occur using only PBPCs incubated ex vivo, that theMDR1 gene product may play a role in engraftment, and that chemotherapy may selectively expand MDR1 gene-transduced hematopoietic cells relative to NeoR transduced cells in some patients.

THE ABILITY TO DEVELOP cellular resistance to anticancer drugs is a property of tumor cells but not of normal cells, including hematopoietic progenitor cells. Although tumor cell populations progressively recruit and use mechanisms of drug resistance, the ability of hematopoietic cells to withstand the toxic effects of chemotherapy seems to diminish. Thus, the clinical response to chemotherapy in the treatment of recurrent cancer often results in the familiar pattern of dose reduction and disease progression.

Gene-therapy techniques offer the potential to transfer the drug resistance mechanisms used by tumors into hematopoietic progenitor cells.1-3 In vitro studies have shown that transgenic expression of the MDR1 gene, which encodes the drug-efflux pump P-glycoprotein, can confer a characteristic pattern of pleiotropic drug resistance to previously drug-sensitive cells.4 5Utilization of the MDR1 gene for hematopoietic cell protection is attractive in the context of breast cancer therapy because theMDR1 gene can confer resistance to several of the active chemotherapeutic agents used in the treatment of this disease, including paclitaxel and doxorubicin, both of which have considerable hematopoietic toxicity.

The ability of this gene to protect hematopoietic progenitor cells from chemotherapy-induced myelotoxicity was first shown in transgenic mice in which the human MDR1 cDNA was constitutively expressed in hematopoietic cells and the animals were shown to be protected from the myelosuppressive effects of chemotherapeutic drugs.6Several murine models have since shown that direct retroviral-mediated gene transfer of MDR1 could be used to introduce and express this gene in hematopoietic cells.7-10 Results from these studies showed that hematopoietic cells transduced with theMDR1 gene have preferential survival after treatment of the animals with MDR drugs. Therefore, because the MDR1 gene can protect blood-forming cells from toxicity, it may also serve as an in vivo selectable marker that could be used to selectively expand the numbers of hematopoietic cells containing this transgene.

Several groups have conducted clinical MDR1 gene therapy trials to examine whether the MDR1 gene could act as a selectable marker in the clinical setting.11-13 In each of these studies, cancer patients received a conditioning regimen of myeloablative chemotherapy and subsequent autologous transplantation with MDR1-transduced hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) supplemented with genetically unmanipulated HSCs. Two of these trials did not present information regarding the effects of MDR1 gene marking on subsequent chemotherapy-induced myelotoxicity. In the third study there was some suggestion of possible protection from chemotherapy-induced myelotoxicity despite low levels of MDR1gene marking in vivo; however, too few patients were studied to draw any conclusions.13 In all three MDR1 gene-therapy trials, the level of gene marking detected at the time of reconstitution has been low (<5%), thus limiting any potential benefit from the myelosuppressive effects of MDR drugs.11-13

In the current study, we examined the feasibility of reconstituting patients with hematopoietic cells exposed to retroviral transduction conditions without simultaneous reinfusion of nonmanipulated hematopoietic progenitor cells. The ex vivo culture conditions necessary for viral transduction may lead to engraftment defects,14 and thus give the nonmanipulated cells a significant advantage in competition for engraftment. The conditioning regimen in this study, single-agent thiotepa (350 mg/m2), was chosen to be less intensive than previously used high-dose chemotherapy regimens, such as ifosfamide-carboplatin-etoposide (ICE), to obviate the need for simultaneous reinfusion of unmanipulated peripheral blood progenitor cells (PBPCs). Therefore, this study differed from previous MDR1 gene-transfer studies in that hematopoietic rescue depended solely on PBPCs that had been incubated in retroviral supernatants.

The ability of the MDR1 gene to protect hematopoietic cells from the myelotoxicity of anticancer drugs was determined by reconstituting patients with gene-modified CD34+ cells, one half of which were transduced with a retroviral vector containing theMDR1 multidrug resistance gene (G1MD), while the other half were transduced with a retroviral vector containing the neomycin resistance (NeoR) gene (G1Na.40). The transductions were supported with autologous irradiated stroma, unlike previous clinical MDR1gene-therapy studies which have relied on cytokines to support viral transduction. After recovery, patients received four cycles of paclitaxel followed by four cycles of either doxorubicin or vinblastine, all of which are known substrates for the MDR1 drug efflux pump. The comparison of the levels of MDR1 to NeoR transgenes in peripheral blood cells was used to determine whether PBPCs containing the MDR1 gene were selectively protected from myelotoxic effects of MDR1 substrate chemotherapy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient selection.

The treatment protocol MB361 was approved by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Institutional Biosafety Committee, the NIH Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee, and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Institutional Review Board. Patients with metastatic breast cancer were eligible for the study. Patients with metastatic breast cancer who declined to participate in the gene-therapy procedures and other patients with high-risk breast cancer were offered enrollment on another study that used the same chemotherapy schema.

Treatment plan.

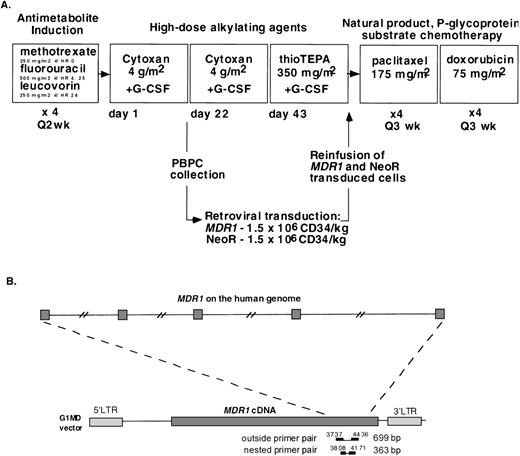

Before chemotherapy, bone marrow aspirates were obtained for diagnostic purposes and to establish autologous stromal cell cultures using procedures previously described.15 The protocol chemotherapy schema is shown in Fig 1A. Patients were first treated with four 2-week cycles of MLF, which consisted of sequential methotrexate (250 mg/m2 intravenous [IV] at hour 0), 5-fluorouracil (500 mg/m2 IV at hours 4 and 25), and leucovorin (250 mg/m2 at hour 24). At least 14 days after the last MLF cycle, when the absolute neutrophil count (ANC) exceeded 1,200/μL and platelets exceeded 90,000/μL, patients were then treated with two 3-week cycles of cyclophosphamide (4 g/m2 over 4 hours) with mesna 2-mercaptoethanesulfonate uroprotection. Patients received filgrastim 10 μg/kg/d beginning on day 2 of the first cyclophosphamide cycle and underwent apheresis when the white blood cell (WBC) count increased to greater than 5,000 cells/μL after reaching the nadir level. Peripheral blood progenitor cells were harvested during recovery from cyclophosphamide using a Fenwal CS3000 (Baxter Corp, Deerfield, IL) or a Cobe Spectra (COBE, Lakewood, CO) apheresis device. All patients underwent two apheresis procedures each, with a mean of 15.2 L of blood processed per procedure. Adequate numbers of PBPCs were collected in all gene-therapy patients after the first cyclophosphamide cycle. The collected mononuclear cells were CD34+ enriched using a Ceprate stem cell concentrator column (Cellpro, Bothell, WA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.16 An aliquot (5 × 106) of CD34-selected cells was examined for breast cancer cell contamination by immunohistochemistry using a panel of anti-keratin antibodies. All of the CD34+ samples were negative for tumor cell contamination, with the limit of detection of 1 tumor cell in 105 CD34+ cells. At least 1.5 × 106 CD34-selected cells per kilogram were stored without further manipulation for hematopoietic rescue in the event of engraftment failure. These cells were placed in freezing medium containing 50% human AB serum, 40% Plasmalyte-A (Baxter), 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Tera Pharmaceuticals, Salt Lake City, UT), 10 μg/mL Darnase (Genentech, Thousand Oaks, CA), and 15 U/mL heparin (Fujisawa, Deerfield, IL). The cells were cryopreserved in a controlled rate freezer and stored in liquid nitrogen.

(A) MB361 chemotherapy schema. Bone marrow aspirate for stroma culture was obtained before the first cycle of chemotherapy. Vinblastine was substituted for doxorubicin after patients exceeded a lifetime cumulative doxorubicin dose of 550 mg/m2. (B) A diagram of the PCR assay showing the position of the primers used to detect the MDR1 transgene and the relative positions of their annealing sequences on the human genome. The numbering system shows that of the G1MD vector. The MDR1 cDNA starts at nt 1479 and ends at nt 5339. The MDR1 ATG start codon is at position 1491.

(A) MB361 chemotherapy schema. Bone marrow aspirate for stroma culture was obtained before the first cycle of chemotherapy. Vinblastine was substituted for doxorubicin after patients exceeded a lifetime cumulative doxorubicin dose of 550 mg/m2. (B) A diagram of the PCR assay showing the position of the primers used to detect the MDR1 transgene and the relative positions of their annealing sequences on the human genome. The numbering system shows that of the G1MD vector. The MDR1 cDNA starts at nt 1479 and ends at nt 5339. The MDR1 ATG start codon is at position 1491.

After recovery from the second cyclophosphamide cycle, patients were treated with thiotepa (350 mg/m2 on day 1) followed by reinfusion on day 4 of the cryopreserved PBPCs that had been incubated in viral supernatant. Patients subsequently received daily injections of filgrastim (5 μg/kg). After hematologic recovery, patients received four 3-week cycles of paclitaxel (175 mg/m2 IV over 24 hours) followed by four 3-week cycles of doxorubicin (60 mg/m2). Vinblastine (1.5 mg/m2/d for 5 days) was administered in place of doxorubicin when the total lifetime doxorubicin dose exceeded 550 mg/m2.

Transduction of hematopoietic cells.

For retroviral transductions, CD34+ cells were collected by centrifugation at 290g for 10 minutes and at a concentration of 1 to 3 × 105 cells/mL in two equal portions of transduction medium (TM). TM consisted of three parts Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles Medium (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Biowhittaker, Walkersville, MD) and either 1 part supernatant from amphotrophic retroviral vector producer cell line G1MD clone 5 (0.5 to 0.6 × 106 vector/mL) or 1 part supernatant from amphotrophic retroviral G1Na (NeoR) vector producer cell line (3.5 to 5.1 × 106 vector/mL) (Genetic Therapy Inc, Gaithersburg, MD). TM was also supplemented with 4 μg/mL protamine sulfate (Fujisawa, Deerfield, MI). Autologous bone marrow stromal cells (0.5 to 2.0 × 106 cells) from each patient were plated in 162-cm2 flasks (Costar, Cambridge, MA) in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum and incubated overnight at 37°C and then irradiated (1,000 cGy). CD34+ cells (1 to 3 × 105 /mL) in TM containing supernatants from retroviral producer cell lines were placed in flasks containing irradiated autologous stromal cells and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 18 to 24 hours. At 24 and 48 hours the nonadherent cells were collected by centrifugation at 745g for 10 minutes, resuspended in fresh TM (containing fresh G1MD or G1Na supernatant), and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. Adherent cells were harvested at 72 hours by incubation with Trypsin-EDTA (GIBCO-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD), combined with nonadherent cells and collected by centrifugation at 745g for 10 minutes. Aliquots were taken for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of G1MD and G1Na vector DNA and for testing for bacterial and fungal contamination. The remaining cells were resuspended in freezing medium and stored in liquid nitrogen.

Detection of transgenes in hematopoietic cells.

A sample of peripheral blood was collected before each cycle and was used for isolation of mononuclear and polymorphonuclear cells. A double gradient was formed by layering an equal volume of HISTOPAQUE-1077 over HISTOPAQUE-1119 (Sigma, St Louis, MO). Whole blood was carefully layered onto the upper HISTOPAQUE-1077 medium, followed by centrifugation at 700g for 30 minutes. Mononuclear cells were found at the plasma/1077 interface whereas cells of the granulocytic series were found at the 1077/1119 interface. The two layers were harvested, washed with HEPES-Buffered Standard Saline (Biofluids, Rockville, MD), and collected by centrifugation for 10 minutes at 700g. Aliquots of cell preparations were counted with a hematocytometer and stained with Hema stain (Biochemical Sciences, Inc, Swedesboro, NJ) to document the purity of the collection. The remaining cells were concentrated again by centrifugation and resuspended in a cell lysis solution (Gentra Systems Inc, Research Triangle Park, NC). All samples were stored at −80°C until DNA extraction.

DNA was isolated from the granulocytes and monocytes using the Puregene DNA isolation kit (Gentra Systems Inc). After the frozen samples were thawed and incubated with RNase A, protein was precipitated from the lysate and pelleted by centrifugation. The supernatant was collected, added to 3 vol of isopropyl alcohol, and the DNA pellet was then formed by centrifugation at 15,000g for 1 minute. The DNA pellet was washed once with 70% alcohol, resuspended in DNA hydration solution, and the concentration determined by ultraviolet spectrophotometry.

Care was taken to avoid potential contamination of patient specimens with PCR products. DNA extraction and PCR assays were performed in separate rooms. Vector DNA was detected with a PCR assay using the following MDR1 primers which span nucleotides (nt) 3737 to 4436 (exons 18 to 23): 5′-TGA AAC AAA ACG ACA GAA TAG TAA C-3′, 5′-AAT ACT AAC AGA ACA TCC TCA AAG C-3′). The amplified fragment is 699 bp (see Fig 1B). These primers span more than 10 kb on the MDR1 genomic gene17 and were chosen to reduce the possibility of amplification of endogenous genomic MDR1sequences. Previous studies have shown that, due to cryptic splice sites within the MDR1 cDNA, G1MD producer cell lines generate both full-length and spliced transcripts resulting in full-length and truncated provirus in target cells.18 The shortened provirus produces a truncated MDR1 mRNA that results in a large deletion of coding sequences. The upstream G1MD primer used for viral detection in these studies is located just upstream of the cryptic splice acceptor site. Therefore, the PCR assay recognizes only full-length proviral sequences. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 94°C for 3 minutes, followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 30 seconds, 58°C for 20 seconds, 72°C for 50 seconds, and a final extension of 10 minutes at 72°C.

Semiquantitative estimates of the relative percent of transgene copy number were made by comparing the relative signal intensity of the G1MD PCR reaction from patient-derived DNA with the relative signal intensity obtained from a control G1MD dilution series. The dilution series was made from DNA extracted from a cloned MCF-7 breast cancer cell line containing a single copy of the MDR1 transgene per cell that was serially diluted in DNA extracted from nontransduced CD34+ cells. These serial dilutions of control DNA were amplified by PCR at the same time as patient samples. PCR products (10 μL) were separated by electrophoresis on a 2% 3:1 agarose gel, stained with SYBR Green (FMC, Rockland, ME), photographed using an electronic camera, and the band intensity was determined using NIH Image software. The densitometry of the dilution series was measured and served as a reference for the relative amount of the MDR1transgene contained in hematopoietic cells obtained from patients.

A nested MDR1 PCR assay was developed using primers located within the first amplified PCR fragment and which span nt 3808 to 4171 and exons 18 to 21 (5′-CAT TTT TCC TTC AGG GTT TCA C-3′, 5′-GTT CTT TCT TAT CTT TCA GTG CTT G-3′). This primer pair produces a 363-bp product (see Fig 1B). The PCR conditions for the nested MDR1 reaction were 94°C for 3 minutes, then 25 cycles at 94°C for 30 seconds, 58°C for 20 seconds, 72°C for 30 seconds, and a final extension of 10 minutes at 72°C. The PCR reaction for actin was performed as a control at the same time using primers 5′-CAT TGT GAT GGA CTC CGG AGA CGG-3′ and 5′-CAT CTC CTG CTC GAA GTC TAG AGC-3′ and used the same conditions as the initial MDR1 PCR reaction. The limit of detection of the nested PCR assay was .01% G1MD vector copy per cell.

PCR for the NeoR gene was performed using the NeoR outer primers (5′-GGC CAG ACT GTT ACC ACT CC-3′, 5′-CAG CCG ATT GTC TGT TGT GC-3′) and nested primers (5′-CGG ATC GCT CAC AAC CAG TC-3′, 5′-AGC CGA ATA GCC TCT CCA CC-3′) and gave a band size of 502 bp.19 The reaction conditions were 95°C for 2 minutes, 20 cycles of 95°C for 1 minute, 60°C for 1.5 minutes, 72°C for 2 minutes for the first PCR and 26 cycles of 95°C for 1 minute, 60°C for 1.5 minutes, 72°C for 2 minutes for the nested PCR, followed by a final extension of 8 minutes at 72°C. In some reactions, [32P]dCTP was added to the nested PCR reaction. PCR products (10 μL) were separated by electrophoresis on a 2% 3:1 agarose gel, stained with SYBR Green (FMC) and photographed using a CCD camera. Band intensity was determined using NIH Image software. Radiolabeled PCR fragments were detected by autoradiography. The limit of detection of the PCR assay was .01% G1Na vector copy per cell.

Detection of helper virus.

Posttransplantation peripheral blood mononuclear cellular DNA was screened by PCR for recombinant helper virus genome as previously described.19 Conditions for amplification were 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by 25 cycles at 95°C for 1 minute and 72°C for 1.5 minutes, and final extension at 72°C for 10 minutes. Retroviral supernatants were also tested for replication-competent helper virus using coculture amplification on mus dunni cell line.20 All samples were negative for helper virus.

RESULTS

The protocol chemotherapy schema is shown in Fig 1A. Of the first nine patients to enroll in the study, six patients underwent PBPC harvest, ex vivo retroviral transduction with the MDR1and NeoR vectors, reinfusion after thiotepa chemotherapy, and completion of eight subsequent cycles of chemotherapy with the MDR drugs paclitaxel, doxorubicin, or vinblastine. Two patients did not complete the study because their bone marrow stromal cells harvested before the beginning of chemotherapy did not grow in vitro, and one patient withdrew consent. The characteristics of the patients who received MDR1 and NeoR gene-transduced CD34+ cells are shown in Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Patient No. . | Age (yr) . | Date of Diagnosis . | Prior Chemotherapy . | Date of Recurrence . | Sites of Disease . | Response . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 36 | 4/10/95 | CAF | 2/14/96 | Bone | EI | PD 10/27/97 |

| 2 | 37 | 10/2/91 | CAF | 4/24/96 | Lung, bone | EI | PD 3/10/98 |

| 3 | 48 | 8/5/91 | CAF | 5/14/96 | Lung, bone | EI | Alive w/o progression |

| 4 | 67 | 5/18/94 | CMF | 8/8/96 | Chest wall, lung | PR | PD 11/13/97 |

| 5 | 39 | 2/9/96 | NONE | — | Chest wall | EI | Alive w/o progression |

| 6 | 49 | 1/21/88 | CMF, TAM | 8/28/96 | Chest wall, nodes | PR | Alive w/o progression |

| Patient No. . | Age (yr) . | Date of Diagnosis . | Prior Chemotherapy . | Date of Recurrence . | Sites of Disease . | Response . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 36 | 4/10/95 | CAF | 2/14/96 | Bone | EI | PD 10/27/97 |

| 2 | 37 | 10/2/91 | CAF | 4/24/96 | Lung, bone | EI | PD 3/10/98 |

| 3 | 48 | 8/5/91 | CAF | 5/14/96 | Lung, bone | EI | Alive w/o progression |

| 4 | 67 | 5/18/94 | CMF | 8/8/96 | Chest wall, lung | PR | PD 11/13/97 |

| 5 | 39 | 2/9/96 | NONE | — | Chest wall | EI | Alive w/o progression |

| 6 | 49 | 1/21/88 | CMF, TAM | 8/28/96 | Chest wall, nodes | PR | Alive w/o progression |

Abbreviations: CAF, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, fluorouracil; CMF, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, fluorouracil; TAM, tamoxifen; EI, evaluable improved; PR, partial response; PD, progressive disease.

The PBPCs used for retroviral transductions were harvested during the first cycle of cyclophosphamide treatment. Apheresis was initiated when the WBC count first exceeded 5,000 cells/μL, and all six patients underwent two apheresis procedures each. As shown in Table 2, the mean blood CD34 cell count increased from 28.9 cells/μL to 112.6 cells/μL from the first to the second day of apheresis. The corresponding increase in the WBC count was from 6,850 cells/μL on day 1 to 18,500 cells/μL on day 2 of apheresis. The stem cell collections were thus performed during the period of exponential increase in the CD34 count in the peripheral blood.

Timing and Yields of Apheresis Procedures

| Patient . | Blood Counts on First Day of Apheresis . | Blood Counts on Second Day of Apheresis . | Total CD34 Cells Collected . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC/μL . | CD34/μL . | WBC/μL . | CD34/μL . | ×106 . | ×106/kg . | |

| 1 | 6,400 | 19.2 | 13,300 | 33.8 | 228 | 2.56 |

| 2 | 8,730 | 17.7 | 17,700 | 32 | 238 | 4.67 |

| 3 | 11,600 | 14.0 | 30,700 | 100 | 60 | 0.94 |

| 4 | 5,040 | 54.4 | 15,800 | 246 | 611 | 11.11 |

| 5 | 5,880 | 20.6 | 13,100 | 59.0 | 220 | 3.20 |

| 6 | 3,460 | 47.6 | 20,300 | 205 | 589 | 12.37 |

| Mean | 6,850 | 28.9 | 18,500 | 112.6 | 324 | 5.81 |

| Patient . | Blood Counts on First Day of Apheresis . | Blood Counts on Second Day of Apheresis . | Total CD34 Cells Collected . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC/μL . | CD34/μL . | WBC/μL . | CD34/μL . | ×106 . | ×106/kg . | |

| 1 | 6,400 | 19.2 | 13,300 | 33.8 | 228 | 2.56 |

| 2 | 8,730 | 17.7 | 17,700 | 32 | 238 | 4.67 |

| 3 | 11,600 | 14.0 | 30,700 | 100 | 60 | 0.94 |

| 4 | 5,040 | 54.4 | 15,800 | 246 | 611 | 11.11 |

| 5 | 5,880 | 20.6 | 13,100 | 59.0 | 220 | 3.20 |

| 6 | 3,460 | 47.6 | 20,300 | 205 | 589 | 12.37 |

| Mean | 6,850 | 28.9 | 18,500 | 112.6 | 324 | 5.81 |

For each patient an aliquot of 1.5 × 106CD34-selected cells/kg was incubated separately with each vector (G1MD and G1Na). Because the purity of the CD34 selected product was approximately 80%, the average number of CD34 cells incubated in each vector was approximately 1.2 × 106 CD34+cells/kg. After 3 days in culture in the presence of viral supernatant and autologous irradiated stroma, the number of surviving CD34 cells decreased to approximately 65% of the original number. Therefore, as shown in Table 3, the mean total number of CD34+ cells available for hematopoietic rescue after thiotepa chemotherapy was only 1.5 × 106CD34+ cells/kg (G1MD, 0.78 × 106CD34+ cells/kg; G1Na, 0.74 × 106CD34+ cells/ kg). In contrast to other MDR1gene-therapy protocols,10-13 in this trial we did not reinfuse any PBPCs that had not been cultured in viral supernatant.

Transduction Efficiencies of G1MD and G1Na Retroviral Vectors

| Patient . | CD34+ Cells After G1MD Incubation ×106/kg . | G1MD Transduction Efficiency % . | CD34+ Cells After G1Na Incubation ×106/kg . | G1Na Transduction Efficiency % . | G1MDMarked CD34+ Cells Reinfused ×104/kg . | G1NaMarked CD34+ Cells Reinfused ×104/kg . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | .80 | .24 | .90 | 9 | .19 | 8.1 |

| 2 | .57 | .28 | .60 | 25 | .17 | 15.0 |

| 3 | .68 | .33 | .63 | 45 | .22 | 28.4 |

| 4 | .86 | .22 | .71 | 43 | .19 | 30.5 |

| 5 | 1.08 | .19 | 1.03 | 8 | .21 | 8.2 |

| 6 | .66 | .28 | .55 | 52 | .18 | 28.6 |

| Mean | .78 | .26 | .74 | 30.3 | .19 | 19.8 |

| Patient . | CD34+ Cells After G1MD Incubation ×106/kg . | G1MD Transduction Efficiency % . | CD34+ Cells After G1Na Incubation ×106/kg . | G1Na Transduction Efficiency % . | G1MDMarked CD34+ Cells Reinfused ×104/kg . | G1NaMarked CD34+ Cells Reinfused ×104/kg . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | .80 | .24 | .90 | 9 | .19 | 8.1 |

| 2 | .57 | .28 | .60 | 25 | .17 | 15.0 |

| 3 | .68 | .33 | .63 | 45 | .22 | 28.4 |

| 4 | .86 | .22 | .71 | 43 | .19 | 30.5 |

| 5 | 1.08 | .19 | 1.03 | 8 | .21 | 8.2 |

| 6 | .66 | .28 | .55 | 52 | .18 | 28.6 |

| Mean | .78 | .26 | .74 | 30.3 | .19 | 19.8 |

In this study retroviral transductions were supported solely with irradiated, autologous stroma; we did not add any additional cytokines to the culture. To determine the relative transduction efficiency of cells after incubation with retroviral supernatants for 72 hours, DNA obtained from cells at the end of the transduction period was analyzed by PCR for the presence of vector DNA and compared to a serial dilution of DNA from a control cell line containing a single copy of G1MD or G1NA vector per cell. As shown in Table 3, the mean transduction efficiency after incubation with G1MD vector was estimated to be 0.26%, while the mean transduction efficiency of cells incubated with G1Na vector was 30.3%. This difference in transduction efficiency between the two vectors was due in part to the 6- to 10-fold difference in titer of viral supernatants for G1MD (0.5 to 0.6 × 106 vector/mL) and G1Na (3.5 to 5.1 × 106vector/mL), and in part to a cryptic splice site in the G1MD vector that renders half of the G1MD proviruses undetectable by our PCR assay due to a large deletion of the MDR1 coding region (see Patients and Methods). The difference in transduction efficiency resulted in a 100-fold difference in the dose of CD34+ cells containing the two vectors; the mean total estimated dose containing full-length G1MD-transduced CD34+ cells was 0.19 × 104 cells/kg (range, 0.17 to 0.22 × 104cells/kg), while the mean number of reinfused NeoR-containing CD34+ cells was 19.8 × 104 cells/kg (range, 8.1 to 30.5 × 104/kg cells/kg).

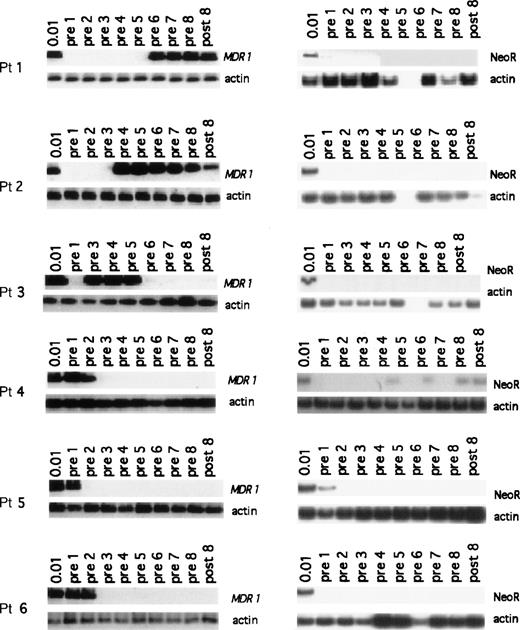

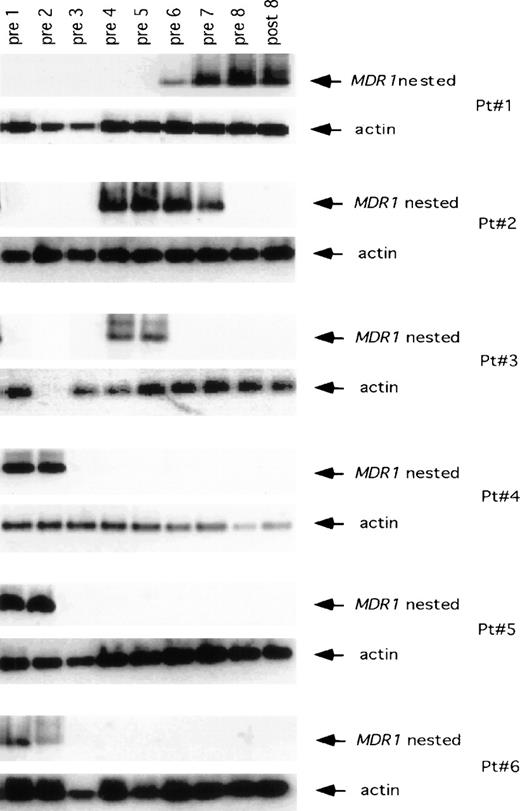

Despite the low number of CD34+ cells reinfused which carried the MDR1 transgene, we were able to detect the presence of the MDR1 transgene after hematopoietic recovery in all 6 patients (Fig 2). In patient 1, no G1MD vector DNA signal was detectable in granulocytes immediately after hematopoietic recovery from high-dose thiotepa chemotherapy (the limit of detection being 0.01% relative gene copy number), nor was vector DNA detected after treatment with four cycles of paclitaxel (pre-cycle 1 through pre-cycle 5). However, G1MD vector DNA was apparent in granulocytes after two cycles of doxorubicin (pre-cycle 6 and pre-cycle 7) and after treatment with two cycles of vinblastine (pre-8 and post-8). MDR1 and NeoR transgene levels in polymorphonuclear cells of the next five patients are also shown in Fig 2. In the second patient, the MDR1 transgene was not detected immediately after hematologic recovery after infusion of G1MD vector–marked cells, but it was detected in granulocytes after the third cycle of paclitaxel and following treatment with four cycles of doxorubicin (pre-cycle 4 through post-cycle 8). In patient 3, no G1MD vector was detectable in granulocytes at hematopoietic reconstitution (pre-cycle 1), but it was detected after the second cycle of paclitaxel. In this patient there was no detectable G1MD vector DNA in granulocytes after the fourth cycle of paclitaxel chemotherapy. For patients 4, 5, and 6, the G1MD transgene was initially present in granulocytes (Fig 2) after hematological recovery from thiotepa, but it was lost during the course of therapy with paclitaxel, and remained undetectable after therapy with either doxorubicin or vinblastine. A similar pattern inMDR1 transgene detection was seen in the examination of monocytes (Fig 3).

PCR assay showing the presence of MDR1 and NeoR transgene in granulocytes for all patients enrolled on the study. In each set of MDR1 panels, the top gel shows the nestedMDR1 primers, and the bottom panels show the control for the amount of DNA placed in PCR reaction using primers for the actin gene. The NeoR gels show the results for the nested NeoR primers.

PCR assay showing the presence of MDR1 and NeoR transgene in granulocytes for all patients enrolled on the study. In each set of MDR1 panels, the top gel shows the nestedMDR1 primers, and the bottom panels show the control for the amount of DNA placed in PCR reaction using primers for the actin gene. The NeoR gels show the results for the nested NeoR primers.

PCR assay showing the presence of the MDR1transgene in monocytes obtained from the patients enrolled in the study. In each set of MDR1 panels, the top gel shows the nestedMDR1 primers, and the bottom panel shows the control for the amount of DNA placed in PCR reaction using primers for the actin gene.

PCR assay showing the presence of the MDR1transgene in monocytes obtained from the patients enrolled in the study. In each set of MDR1 panels, the top gel shows the nestedMDR1 primers, and the bottom panel shows the control for the amount of DNA placed in PCR reaction using primers for the actin gene.

By reinfusing an equal number of PBPCs transduced with the control gene NeoR in the study design, we were able to discern the specific effect of transgenic expression of the MDR1 gene on both engraftment and on subsequent response of transduced cells to chemotherapy. Despite the much higher transduction efficiency of the G1Na vector, the NeoR transgene was only faintly detectable (=.01% NeoR gene copy) in granulocytes of three patients (Fig 2). In patients 1 and 5, G1Na vector DNA signal was seen only in peripheral granulocytes obtained at hematopoietic reconstitution from high-dose thiotepa (pre-cycle 1), but it was undetectable thereafter. In patient 4, a low level of G1Na marking was observed intermittently after treatment with paclitaxel and doxorubicin (pre-cycles 4, 6, and 8, and post-cycle 8), suggesting that the level of marking was constant and near the limit of detection of 0.01%.

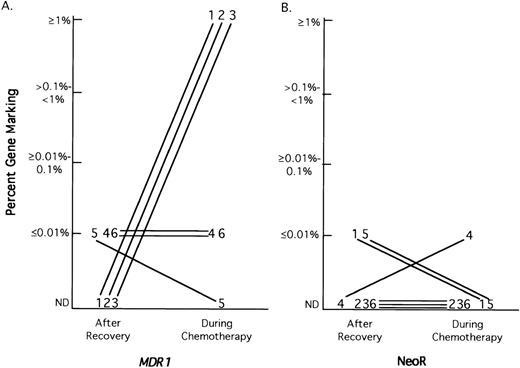

Semiquantitative PCR analysis was used to determine the level of G1MD- and G1Na-transduced granulocytes in each patient at the time of hematopoietic reconstitution and after each cycle of MDR chemotherapy by comparing the PCR signal strength of the transgene with serial dilutions of DNA from a control cell line containing a single vector copy per cell. As shown in Fig 4A, of the three patients that had undetectable levels (<.01%) of G1MD vector in granulocytes at the time of hematopoietic reconstitution, all three patients had increased G1MD marking at some time after chemotherapy to levels >1.0% (=1 G1MD vector per 100 cells). One of the other three patients with low levels of gene marking at the time of reconstitution became negative after the first cycle of chemotherapy, while the other two patients who were initially G1MD positive remained at a low level of G1MD marking during the first cycle of chemotherapy and then decreased to an undetectable level. In contrast, as shown in Fig 4B, only one patient converted from undetectable marking with G1Na at hematopoietic reconstitution to a positive level of marking on chemotherapy, but the highest level achieved was only 0.01%.

Semiquantitative PCR analysis G1MD (A) and G1Na (B) marking in granulocytes at hematopoietic recovery and during MDR chemotherapy. Semiquantitative PCR analysis for G1MD and G1Na was performed on DNA from granulocytes obtained at hematopoietic reconstitution and during each cycle of chemotherapy. The maximal level of marking for each vector at hematopoietic recovery and at any time during chemotherapy is depicted for each patient. The patient samples are referred to by patient number.

Semiquantitative PCR analysis G1MD (A) and G1Na (B) marking in granulocytes at hematopoietic recovery and during MDR chemotherapy. Semiquantitative PCR analysis for G1MD and G1Na was performed on DNA from granulocytes obtained at hematopoietic reconstitution and during each cycle of chemotherapy. The maximal level of marking for each vector at hematopoietic recovery and at any time during chemotherapy is depicted for each patient. The patient samples are referred to by patient number.

This is the first study of hematopoietic gene therapy in which the PBPCs that had been cultured in viral supernatant were not supplemented with unmanipulated PBPCs before infusion in patients. Therefore, hematological recovery of these patients from high dose thiotepa is of interest. Since we contemporaneously enrolled other breast cancer patients (high-risk stages II, III, and IV) on a study (MB381) which used the same chemotherapy schema as was used in the gene therapy study (MB361), we compared the hematologic recovery of the gene-therapy patients with patients receiving the same chemotherapy, but whose PBPC collections were not incubated in viral supernatant after CD34 selection. As shown in Table 4, patients enrolled on MB361 received a lower dose of PBPCs owing to the loss of CD34 cells during the retroviral transduction process, with the gene therapy patients receiving a median dose of 1.4 × 106CD34+ cell/kg compared with a median CD34+ dose of 2.4 × 106 cells/kg for the non–gene-therapy patients. Nevertheless, there was little difference in the median time to recovery of a granulocyte count >500 cells/μL (11.0 ± 0.9v 10.0 ± 0.4 days) or to a granulocyte count of >1,200/μL (12.5 ± 0.8 v 11.0 ± 0.8 days), and only a 2.5-day difference (14.5 ± 2.7 v 12.0 ± 1.5 days) in time to platelet count >20,000/μL (without requiring platelet transfusions). One gene-therapy patient and two non–gene-therapy patients required reinfusion of additional, unmanipulated stored PBPCs to aid hematological recovery (granulocytes >1,200/μL and platelets >90,000/μL) to continue the chemotherapy regimen.

Time to Hematopoietic Recovery

| . | Gene Rx Patients (n = 6) . | Non-Gene Rx Patients (n = 13) . |

|---|---|---|

| Median days (±SD) to granulocytes >500/μL | 11 ± 0.9 | 10 ± 0.4 |

| Median days (±SD) to granulocytes >1,200/μL | 12.5 ± 0.8 | 11 ± 0.8 |

| Median days (±SD) to platelets >20,000/μL | 14.5 ± 2.7 | 12 ± 1.5 |

| Median (±SD) CD34+ cells reinfused (×106/kg) | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 2.4 ± 0.3 |

| . | Gene Rx Patients (n = 6) . | Non-Gene Rx Patients (n = 13) . |

|---|---|---|

| Median days (±SD) to granulocytes >500/μL | 11 ± 0.9 | 10 ± 0.4 |

| Median days (±SD) to granulocytes >1,200/μL | 12.5 ± 0.8 | 11 ± 0.8 |

| Median days (±SD) to platelets >20,000/μL | 14.5 ± 2.7 | 12 ± 1.5 |

| Median (±SD) CD34+ cells reinfused (×106/kg) | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 2.4 ± 0.3 |

Abbreviation: Rx, therapy.

All six gene-therapy patients were treated for metastatic breast cancer. Two of the six patients had measurable disease at the time of enrollment, and both of these patients achieved a partial response with the chemotherapy regimen (see Table 1). All of the other four patients had evaluable disease only and showed improvement with chemotherapy. However, these patients were unevaluable for overall response. All six patients completed the chemotherapy regimen, which took approximately 11 months from the time of enrollment on the study.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we have explored the concept of using gene therapy to enhance the effectiveness of anticancer chemotherapy by imparting drug resistance on normal tissues.1-3 This strategy holds out the promise not only of making bone marrow cells more resistant to chemotherapy, but also of exploiting drug-resistance genes to help deliver and expand cells cotransduced with other therapeutic genes that could be used in the treatment of both cancer and nonmalignant disorders.

Previous clinical studies of MDR1 gene transfer into hematopoietic stem cells have shown that patients can be reconstituted with MDR1 gene–marked hematopoietic cells. However, the levels of gene marking in the previous studies were low.11-13 Two factors common to each of these trials may have contributed to this outcome. First, to promote proviral integration of the retroviral transgene, ex vivo culture conditions included incubation of CD34+ cells with the cytokines interleukin-3 (IL-3), IL-6, and stem cell factor; these cytokines stimulate quiescent, pluripotent hematopoietic cells to enter the cell cycle and become susceptible to retroviral integration into the host cell genome. Incubation of PBPCs under these conditions can result in expansion of the number of cells in culture after the incubation period, increased retroviral transduction efficiency, and increased number of colony-forming units (CFUs) containing the transgene. However, animal studies have shown that incubation of hematopoietic stem cells with these cytokines results in an engraftment defect.21,22 Furthermore, the fraction of CFUs containing an MDR1 transgene after incubation in cytokines, which was thought to be a surrogate marker for transduction of pluripotent stem cells, has not correlated with the long-term engraftment of hematopoietic cells containing the transgene.12 In addition, the stimulation of cell division by these cytokines may have irreversibly placed the primitive stem cells in the CD34-selected collection on a path toward differentiation and ultimately apoptosis.

Second, in the interest of safety, previous MDR1 gene-therapy studies reinfused stored, unmanipulated PBPCs along with the PBPCs incubated in viral supernatant and cytokines. Uncultured and unmanipulated PBPCs may have a significant competitive advantage over cultured PBPCs for engraftment resulting in decreased gene marking efficiencies in vivo. After reinfusion of equal numbers of cultured and nonmanipulated hematopoietic progenitors, animal studies indicate that only one tenth of the cells that repopulate the marrow come from cells that were incubated in tissue-culture conditions.14

In the current MDR1 gene-transfer clinical study, the trial design was modified in an attempt to optimize transduction and engraftment of gene-marked pluripotent stem cells. First, the retroviral transduction was supported with autologous, irradiated stroma rather than using the cytokines commonly used for ex vivo transduction—IL-3, IL-6, and stem cell factor. Second, we reinfused only PBPCs incubated in retroviral supernatant; we did not supplement the PBPC rescue with stored, unmanipulated PBPCs. Third, the conditioning regimen in this study was single-agent thiotepa (350 mg/m2). Although this dose of thiotepa produces significant myelosuppression, it may be less toxic to the bone marrow microenvironment than standard conditioning regimens. It is possible that any of these changes may have facilitated MDR1 gene transfer into a stem cell compartment that could successfully engraft and expand with subsequent breast cancer chemotherapy.

All six patients entered on this trial had evidence of G1MD marking in granulocytes during treatment with MDR chemotherapy (paclitaxel, doxorubicin, and vinblastine). In the first three patients, no G1MD vector DNA was detected in granulocytes or monocytes at the time of hematopoietic reconstitution after treatment with thiotepa. However, G1MD marking became apparent in both granulocytes and monocytes during treatment with MDR chemotherapy in all three patients. In contrast, G1MD vector DNA was detected immediately after hematopoietic reconstitution in patients 4, 5, and 6, but it was lost in both granulocytes and monocytes early on after treatment in these patients as well as in patient 3.

These results suggest that in the first two patients, G1MD transduction occurred in pluripotent stem cells with long-term engrafting potential. In contrast, G1MD transduction in the other patients most likely occurred in progenitor cells that were ultimately destined for elimination by programmed cell death. Although G1MD-transduced cells may be protected from MDR chemotherapy, the survival ofMDR1-transduced hematopoietic progenitor cells in patients is also dependent on the state of differentiation of the hematopoietic cell in which the gene is transduced ex vivo. An alternative explanation is that the first two patients received paclitaxel at 250 mg/m2 with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) support for all four cycles, while the remaining four patients received paclitaxel at 175 mg/m2 with G-CSF only if needed (ANC <500/μL for >3 days). This raises the possibility that the paclitaxel dose may not have been high enough in the last group of patients to select for the MDR1 transgene, or that the G-CSF administration resulted in prestimulation of primitive cells and contributed to the selection of the MDR1 transgene, as has been shown experimentally to be the case with stem cell factor.23

In the current trial we used the NeoR gene (G1Na vector) as a control to compare two equal populations of CD34+ cells, which differed only in the gene that was inserted into the host genome. Although the transduction efficiency of the NeoR vectors under our culture conditions was almost two orders of magnitude higher than the transduction efficiency of the MDR1 vector, we were surprised that we were able to detect the MDR1 transgene in peripheral blood granulocytes more frequently and at higher levels than the NeoR gene. All six patients marked for MDR1, whereas only three of six patients showed NeoR marking. Semiquantitative PCR analysis indicated that the highest level of NeoR gene marking, obtained in patient 4, was only 0.01% of total peripheral blood granulocytes. These results are comparable with previous studies by us using stroma-supported transduction of NeoR15 (and C.D., unpublished observations, 1998): in a total of six patients, only three showed intermittent NeoR marking and none showed sustained engraftment of NeoR-marked cells. In comparison, the level ofMDR1 marking observed in all six patients ranged from 0.01% to 1% of the total peripheral blood granulocytes (Fig 4). These results suggest that the transgenic MDR1 expression may have had a beneficial effect on hematopoietic cell reconstituting ability, even when it did not lead to long-term repopulation and expansion with MDR drug therapy.

These results are consistent with a recent competitive repopulation experiments in mice by Bunting et al.24 In these studies, murine bone marrow cells transduced with a Harvey-based retroviral vector containing the human MDR1 gene (HaMDR1) during cytokine stimulation showed a substantial increase in multipotent repopulating cells compared to control marrow cells transduced with a retroviral vector containing a mutant dihydrofolate reductase gene.24The mechanism whereby MDR1 transduction might enhance long-term engraftment of cells is unclear. Recent studies have indicated thatMDR1 overexpression can protect cells from undergoing apoptosis.25,26 Thus, MDR1 transduction of hematopoietic progenitor cells might reduce their susceptibility to programmed cell death. Alternatively, it is possible that MDR1overexpression in primitive hematopoietic cells could reduce their propensity to differentiate toward committed progenitor cells in vitro and in vivo.24

Bunting et al24 also found that hematopoietic cells transduced with the Harvey-based HaMDR1 vector and then cultured for an additional 12 days in the presence of cytokines produced a myeloproliferative disorder in recipient mice which was not observed in mice reinfused with cells immediately after transduction. The report of myeloproliferative disorders following reinfusion of cells containing the MDR1 transgene raises important safety concerns. However, it is not clear how the prolonged incubation in cytokines and the Harvey-based vector interacted with MDR1 to produce this effect. The current clinical trial used a Moloney-based retroviral vector for both the MDR1 and NeoR vectors and did not subject cells to prolonged incubation after transduction. No preclinical6-8,27 or clinical11-13 studies have reported myeloproliferation in recipients of MDR1 transduced cells, nor has the NeoR Maloney-based vector been associated with hematopoietic disorders in recipient patients.19 28

This trial of MDR1 gene therapy occurred in the context of a pilot trial of prolonged sequential high-dose chemotherapy for breast cancer. Rather than use autologous stem cell rescue as consolidation,29 we employed a sequential, continuous chemotherapy strategy that would optimize the utilization of theMDR1 transgene if improvement in transduction efficiency could make MDR1-mediated hematopoietic protection clinically beneficial. The sequential nature of the chemotherapy schema was suggested by the findings of Bonadonna et al,30 who demonstrated the superiority of sequential doxorubicin followed by sequential cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil, as opposed to alternating these two regimens, as adjuvant therapy in breast cancer patients with four or more positive lymph nodes. The treatment plan began with an antifolate-based induction regimen of methotrexate, fluorouracil and leucovorin based on a regimen used in colon cancer.31 We then harvested and reinfused PBPCs in the context of high- dose alkylating agent chemotherapy. After engraftment, therapy was consolidated with the MDR1 drugs paclitaxel and doxorubicin. This treatment design permitted the engraftment ofMDR1 hematopoietic stem cells in patients before the initial administration of chemotherapeutic agents that are substrates for the drug-resistance transgene.

This study shows that patients can be reconstituted with PBPCs incubated in retroviral supernatants after treatment with high-dose thiotepa and that, under these conditions, no unmanipulated cells need to be included in the stem cell rescue. It is possible that long-term engraftment resulted primarily from residual hematopoietic cells and not from the cultured, but not genetically altered, reinfused stem cells. Thus, it is not known whether long-term engraftment of gene-marked cells was enhanced or diminished by the use of a myelotoxic, rather than a myeloablative, preparative regimen.

The design of this study allowed us to examine the effect ofMDR1 both on engraftment as well as on in vivo selection with MDR drugs. In all six patients, the higher level of engraftment of MDR1-containing cells relative to NeoR, despite a lower transduction efficiency, suggests that MDR1 overexpression may have had a beneficial effect on the engraftment potential of hematopoietic cells. However, clear assessment of the potential of the MDR1transgene for in vivo selection was limited both by the fact that only two of six patients showed evidence of in vivo expansion, and by the inability to perform functional studies on the MDR1-containing engrafted cells due to the low transduction efficiency.

Therefore, although the ability of retroviral vectors containingMDR1 to confer drug resistance in hematopoietic lineages in animal models is not in doubt,7-10 the ability of this transgene to confer clinical drug resistance in human hematopoietic tissues has yet to be conclusively shown. The low efficiency of hematopoietic reconstitution of patients with gene-transduced cells capable of long-term engraftment remains the major limitation to widespread application of MDR1 gene therapy for therapeutic benefit. Additional studies with greater numbers of patients are needed to identify strategies to increase the efficiency of gene transduction in hematopoietic stem cells with long-term engraftment and self-renewal potential.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Kenneth H. Cowan, MD, PhD, UNMC/Eppley Cancer Center, Eppley Institute for Research in Cancer, 600 S 42nd St, Omaha, NE 68198-6085.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal