Abstract

The cytotoxic effect of anticancer drugs has been shown to involve induction of apoptosis. We report here that tumor cells resistant to CD95 (APO-1/Fas) -mediated apoptosis were cross-resistant to apoptosis-induced by anticancer drugs. Apoptosis induced in tumor cells by cytarabine, doxorubicin, and methotrexate required the activation of ICE/Ced-3 proteases (caspases), similarly to the CD95 system. After drug treatment, a strong increase of caspase activity was found that preceded cell death. Drug-induced activation of caspases was also found in ex vivo-derived T-cell leukemia cells. Resistance to cell death was conferred by a peptide caspase inhibitor and CrmA, a poxvirus-derived serpin. The peptide inhibitor was effective even if added several hours after drug treatment, indicating a direct involvement of caspases in the execution and not in the trigger phase of drug action. Drug-induced apoptosis was also strongly inhibited by antisense approaches targeting caspase-1 and -3, indicating that several members of this protease family were involved. CD95-resistant cell lines that failed to activate caspases upon CD95 triggering were cross-resistant to drug-mediated apoptosis. Our data strongly support the concept that sensitivity for drug-induced cell death depends on intact apoptosis pathways leading to activation of caspases. The identification of defects in caspase activation may provide molecular targets to overcome drug resistance in tumor cells.

ANTICANCER DRUGS have been shown to target diverse cellular functions in mediating cell death in sensitive tumors. Anthracyclines are assumed to induce a genotoxic effect by damaging DNA, whereas other drugs may inhibit certain metabolic pathways or disrupt the mitotic apparatus.1 However, the precise molecular requirements that are central for drug-mediated cell death are largely unknown. Recently, it has been shown that most antineoplastic drugs used in chemotherapy of leukemias and solid tumors induce apoptosis in drug-sensitive target cells.2-5 Apoptosis is a highly conserved physiologic process important in normal development and tissue homeostasis of multicellular organisms with characteristic morphologic features such as membrane blebbing and nuclear condensation and fragmentation.6 7 Physiological apoptosis can be induced by a multitude of stimuli, including withdrawal of growth factors and hormones, inappropriate expression of oncogenes, and activation of death receptors such as CD95 (APO-1/Fas) and tumor necrosis factor-receptor type I (TNF-RI).

Studies in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans have been crucial to the identification of critical components of the cell death machinery. Genetic analyses showed that apoptosis during development of C elegans embryo is controlled by a hierarchical set of genes that include ced-3, ced-4, and ced-9 as key regulators.6,8,Ced-3 exhibits significant homology with the mammalian protease interleukin-1β (IL-1β)–converting enzyme (ICE; caspase-1)9 that is required for proteolytic processing of the IL-1β precursor to the active cytokine.10,11 In transfection experiments, caspase-1 can substitute defective ced-3 in C elegans and is capable of eliciting cell death after overexpression in COS or Rat-1 cells.12 Although caspase-1 itself can induce apoptosis upon overexpression in mammalian cells, mice deficient in caspase-1 develop normally and, in most cases, cells from these animals are still capable of undergoing apoptosis.13,14 Recently, a number of other related proteases have been identified that form a multigene family termed caspases. Mammalian members include caspase-1 (ICE), caspase-2 (Nedd2 and Ich-1), caspase-3 (CPP32 and Yama), caspases-4 (TX, Ich-2, and ICE rel II), caspase-5 (ICE rel III and TY), caspase-6 (Mch2), caspase-7 (Mch3, ICE-LAP3, and CMH-1), caspase-8 (FLICE, MACH, and Mch5), caspase-9 (ICE-LAP6 and Mch6), and caspase-10 (Mch-4) (reviewed in Kumar and Harvey,15 Alnemri et al,16 Martin and Green,17 Schulze-Osthoff et al,18 and Fraser and Evan19 ). Caspases are synthesised as inactive proenzymes that are proteolytically processed to form active heterodimers.20,21 Activation may proceed through autoproteolysis of the precursor, through processing by another caspase, or by still undefined processes. A conserved structural motif of most caspases is the pentapeptide QACRG surrounding the putative active site cysteine residue.17 As in pro–IL-1β, all caspases require an aspartate residue in P1 position of the substrate. Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase (PARP), an enzyme involved in DNA repair, is cleaved during apoptosis22 and has been shown to serve as a substrate for caspase-3.23 Because single members of the caspase family possess a slightly different substrate specificity and the ability to process each other, one can assume that either apoptosis proceeds through a linear cascade of proteolytic events or that caspases are, at least in part, functionally redundant.

Caspases have been intimately implicated in the apoptotic pathway triggered by the surface receptor CD95 (APO-1/Fas).18 The CD95 receptor-ligand system plays a pivotal role in various physiologic and pathologic forms of cell death.24-26 In addition, CD95-mediated apoptosis may be triggered in malignant cells such as T-cell leukemias.27-29 CD95-mediated apoptosis is prevented by specific peptide inhibitors and overexpression of CrmA, a pox virus-derived serpin-like inhibitor.23,30-32 Experiments in fibrosarcoma cells using antisense techniques have further shown that caspase-1 itself may be important in CD95-mediated cell death in certain cell types.31 This is underscored by the finding that thymocytes from caspase-1 (−/−) mice are resistant to CD95-induced apoptosis.14 However, caspase-1 (−/−) mice do not exhibit autoimmune diseases usually associated with a defective CD95 system, suggesting that caspase-1 itself may have a more restricted role in certain cell types or in specific developmental stages. In addition, the previous finding that apoptosis induced by the drosophila gene reaper is mediated via ICE-like activity shows the key role of ICE proteases as effector molecules in evolutionary conserved apoptotic pathways.33 34

Disrupted apoptosis pathways may be involved in tumor formation and may confer resistance to treatment approaches.35 Resistance to chemotherapy is a major concern in cancer treatment.3 Tumors frequently display resistance to a variety of structurally and functionally unrelated agents that has in many cases been attributed to mechanisms of multidrug resistance gene (MDR)-mediated drug exclusion.36 In addition, there is mounting evidence that defective or deregulated apoptosis programs may also contribute to drug resistance.37 38

Recent work in our laboratory has indicated that CD95/CD95 ligand interaction may be triggered in leukemia cells during apoptosis induced by anticancer drugs.39 Because caspases have previously been shown to mediate apoptosis upon CD95 triggering,31 we investigated the involvement of caspases in drug-induced cytotoxicity. We show that caspases are critically involved in apoptosis triggered by doxorubicin (DX), methotrexate (MT), and cytarabine (CR). Using specific inhibitors of caspases and antisense approaches, we show that presumably two prototype proteases, caspase-1 and caspase-3, are required for induction of cell death. Furthermore, resistance to CD95-induced apoptosis was associated with resistance to cell death induced by chemotherapeutic agents. The finding of cross-resistance between drug-induced apoptosis and the CD95 pathway gives an important insight into the molecular mechanism of drug sensitivity and resistance of tumor cells and provides new targets for drug development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and drug treatment. The human cell lines CEM (acute T-cell leukemia), SHEP (neuroblastoma), and MG63 (osteosarcoma) were grown in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine (all from GIBCO BRL, Eggenstein, Germany), and 50 μmol/L β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany). CD95-resistant cells were generated by continuous culture in anti–APO-1 (mouse IgG3, 1 μg/mL40 ) for 3 months. Likewise, doxorubicin-resistant cells were isolated after continuous culture in increasing concentration (up to 100 ng/mL) of doxorubicin. The cytotoxic drugs DX, MT, and CR were purchased from Sigma as pure substances. CR and DX were freshly dissolved in sterile distilled water and MT was dissolved in 0.01 N NaOH before each experiment. The final concentrations of CR, DX, and MT used in the experiments were 100 μg/mL, 100 ng/mL, and 100 μg/mL, respectively.

Measurement of apoptosis. Apoptosis was assessed by the method first described by Hardin et al,41 using propidium iodide uptake and analysis of DNA fragmentation with the dye Hoechst 33342. Cells were simultaneously stained with 0.5 μg/mL propidium iodide (Sigma) and 1 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis (FACS Vantage; Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany). The data represent the mean ± SD from three experiments with duplicate samples. Spontaneous cell death in the absence of apoptosis inducing agents was less than 10%.

Determination of proteolytic activity of caspases. Caspase activity was measured by FACS analysis as described.31 Briefly, cells were loaded in hypotonic medium (RPMI-1640:H2O = 1:1.25) in the presence of 10 mmol/L β-mercaptoethanol with the fluorogenic substrate DABCYL-YVADAPK-EDANS (50 μmol/L; Bachem, Bubendorf, Switzerland)42 containing the cleavage site of the IL-1β precursor. After 10 minutes, osmolarity was restored by the addition of 5× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in 50% fetal calf serum. After 10 minutes of further incubation at 37°C, the reaction was terminated by putting the cells on ice. Fluorescence was measured with an UV laser-equipped flow cytometer (FACS Vantage; Becton Dickinson) using an excitation wavelength of 360 nm and emission wavelength of 488 nm.

cDNA constructs. The cDNAs encoding human caspase-1, -2, and -3 were isolated by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction from Jurkat cell-derived mRNA and cloned into the eukaryotic expression vector pCDNA-3 (Invitrogene, NV Leek, The Netherlands). Antisense constructs were generated by inserting a fragment of approximately 300 bp starting close to the ATG codon in reverse orientation. For antisense ICH-1L , the 1-258 bp insert was cloned as a HindIII/BamHI fragment into pCDNA-3. For antisense ICE and antisense CPP32, the 23-419 bp and 185-531 bp cDNA fragments, respectively, were cloned as HindIII/EcoRI inserts into pCDNA-3. The correct sequences of the constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The vector pSV25CrmA encoding vaccinia virus-derived CrmA has been described previously.31

Microinjections. Cells (0.8 to 1 × 106) were seeded in 60-mm tissue dishes. After overnight incubation, cell nuclei were microinjected with either empty vector, antisense constructs (ich-1, ice, and cpp32 ), or pSV25CrmA. Cell injections were performed with an automatic microinjection system (Zeiss ALS, Göttingen, Germany) equipped with glass micropipettes that had been loaded with 1 μLof the appropriate DNA diluted to about 0.1 mg/mL with 0.2% Texas red-labeled dextran 70 kD (Molecular Probes). After microinjection, cells were washed three times with RPMI-1640, left for 8 hours at 37°C, and then treated with anti–APO-1, CR, DX, or MT. After 30 hours (SHEP cells) or 48 hours (MG63 cells) of further incubation, cells were scored microscopically. Cells were regarded as apoptotic when they showed membrane blebbing and/or a condensed cell nucleus. All experiments were independently evaluated by two scientists in blind samples. At least 180 cells were analyzed for each condition in three independent experiments.

Transfections. Cells were washed in TBS, resuspended at 1 × 108 cells/0.4 mL TBS, and transfected with 15 μg of expression plasmids using a Bio-Rad electroporator (975 μF, 250 V; Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). After electroporation, cells were seeded in a 6-well plate at 1 × 106 cells/well. Eight hours later, cultures were treated with G418 (1 mg/mL; GIBCO) and incubated for a further 36 hours to select transfected cells. Dead CEM cells were removed by Ficoll gradient centrifugation. As determined by cotransfection with the eukaryotic lacZ expression vector CMV-β-gal (Clontech, Heidelberg, Germany) and X-Gal staining, this procedure resulted in the enrichment of 70% to 90% of transfected SHEP cells and 65% to 85% of transfected CEM cells. For X-Gal staining, cells were fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde for 5 minutes, washed once with PBS, and stained for 10 to 12 hours in X-Gal buffer containing 5 mmol/L K4Fe(CN)6 , 5 mmol/L K3Fe(CN)6 , 2 mmol/L MgCl2 , and 1 mg/mL 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoxyl-β-galactoside.

Densitometry. Western blot films were photographed using HEROLAB (Herolab Molekulare Trenntechnik, Wiesloch, Germany) system and evaluated by the EASY software (provided with the system). In each case, data from two independent experiments were evaluated. Deviations between experiments were less than 12%.

Limiting dilution assay. CEM cells were transfected with empty vector, antisense ICE, or CPP32 constructs and selected in G418-containing medium for 36 hours. Cells were then treated with the indicated cytotoxic drugs. After 30 hours, dead cells were washed away (Ficoll-Paque) and the remaining ones were adjusted to a concentration of 3 × 105 cells/mL. Limiting dilutions (1:3) were performed with 200 μL per well. Cell viability was assayed by trypan blue exclusion after 14 days. The highest dilutions still containing living cells are indicated. Samples of cells transfected with control vector contained no living cells.

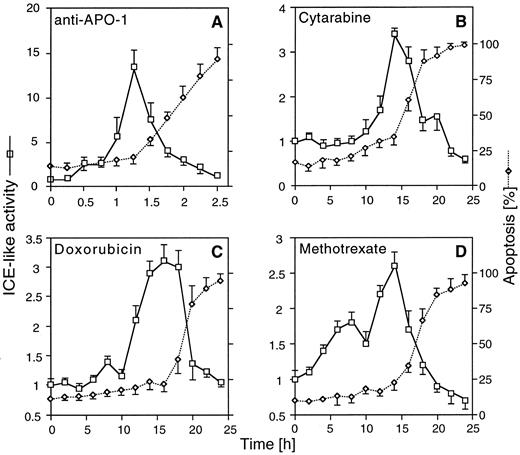

Stimulation of ICE-like proteolytic activity after CD95 ligation and chemotherapeutic drug treatment in CEM cells. CEM cells were incubated for the indicated times with anti–APO-1 (A), CR (B), DX (C), and MT (D) at concentrations indicated. Ten minutes before harvest, cells were permeabilized by a short hypotonic shock and incubated with 50 μmol/L of the fluorogenic ICE substrate. Cells were analyzed in parallel by FACS for induction of cell death and ICE proteolytic activity. The data represent the mean ± SD from three experiments with duplicate samples. Similar data were obtained in SHEP cells (data not shown).

Stimulation of ICE-like proteolytic activity after CD95 ligation and chemotherapeutic drug treatment in CEM cells. CEM cells were incubated for the indicated times with anti–APO-1 (A), CR (B), DX (C), and MT (D) at concentrations indicated. Ten minutes before harvest, cells were permeabilized by a short hypotonic shock and incubated with 50 μmol/L of the fluorogenic ICE substrate. Cells were analyzed in parallel by FACS for induction of cell death and ICE proteolytic activity. The data represent the mean ± SD from three experiments with duplicate samples. Similar data were obtained in SHEP cells (data not shown).

Measurement of P-glycoprotein (P-gp; MDR-1) expression. Cells were stained with mouse anti–MDR-1 monoclonal antibody UIC2 (50 μg/mL; Immunotech, Marseilles, France) for 30 minutes at 4°C After washing in cold Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution/1% bovine serum albumin (GIBCO), the cells were incubated with goat F(ab′)2 antimouse IgG2a-RPE (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc, Birmingham, AL) for 30 minutes at 4°C and analyzed by FACScan (Becton Dickinson).

Western blotting. Cleavage of the caspase precursors, PARP, and Bcl-2–related proteins were detected by Western blotting. Cells were washed in PBS and lysed in a buffer containing 1% NP-40, 20 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 137 mmol/L NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF ), 1 μg/mL benzamidine, 1 μg/mL aprotinin, and 1 μg/mL leupeptin. Lysates were separated on a 15% (for caspases and Bcl-2–related proteins) or 8% (for PARP) sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under reducing conditions and were transferred onto nitro-cellulose membranes. Proteins were stained with specific antisera against caspase-1, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), caspase-2, caspase-3 (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY), and Bax (Calbiochem, Bad Soden, Germany). An anti-PARP antiserum was kindly provided by Dr J.M. deMurcia (Strasbourg, France). Bound antibodies were detected with a mouse antirabbit/horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Santa Cruz) followed by enhanced chemoluminescent (ECL) staining using ECL reagents (Amersham, Braunschweig, Germany).

RESULTS

Caspase activity is induced by chemotherapeutic drugs. Activation of some caspases has previously been shown to be required for apoptosis after CD95 triggering.23,29,31 Recent work in our laboratory has indicated that CD95/CD95 ligand interaction may play a role in apoptosis induced by anticancer drugs in leukemia cells.39 We therefore investigated the role of caspases in cytotoxic drug-induced apoptosis. Activation of caspases was monitored by FACS analysis, with the fluorogenic substrate DABCYL-YVADAPVK-EDANS containing the caspase-1 cleavage site of the IL-1β precursor.31 Simultaneous measurement of substrate cleavage and apoptosis confirmed that anti–APO-1 induced a strong (∼15-fold), transient activation of proteolytic activity of caspases that preceded the onset of apoptosis (Fig 1A). Increased cleavage (∼3-fold) of the substrate was also observed upon treatment with CR, DX, and MT, although both activation of caspases and apoptosis occurred at later time points (Fig 1B through D). In contrast to anti–APO-1, which caused a sharp peak of activation, drug-induced activation of caspases was maintained at an increased level for 5 to 10 hours. This may suggest that, in contrast to direct death inducers such as CD95, drug-induced apoptosis is less synchronized and may require induction of other signalling molecules or accumulation of cellular changes before activation of caspases. Activation of caspases was confirmed by Western blot analysis detecting proteolytic cleavage of caspases-1, -2, and -3 and PARP upon drug treatment (data not shown). These results suggested that activation of caspases may be crucial for drug-induced apoptosis, similar to the requirement of caspases for an intact CD95 pathway.

Peptide inhibitors of caspases reduce cytotoxic drug-induced apoptosis. To further explore the functional involvement of caspases in drug-induced cell death, we used a tripeptide inhibitor that potently inhibits proteolytic activity of caspases and CD95-mediated apoptosis. zVAD-CH2F (zVAD) is an active site inhibitor that mimics the aspartic acid in the P1 position of known substrates of caspases. Pretreatment of CEM cells with zVAD led to dose-dependent resistance in 60% to 80% of cells towards CR-, DX-, or MT-induced death after 30 hours of drug incubation (Fig 2A). Similar data were obtained for SHEP neuroblastoma cells (Fig 2B). A significant percentage (>50%) of pretreated cells was alive even after prolonged exposure (72 hours). To analyze the level of interference of zVAD with drug-induced apoptosis, we either coincubated zVAD together with drugs or delayed addition of zVAD for different periods of time. Protection from drug-induced death could be observed when addition of zVAD was delayed for up to 8 hours after the addition of drugs (Fig 2C), indicating that inhibition of caspases interfered with a death effector mechanism rather than with a primary target of anticancer drugs. Unrelated protease inhibitors such as leupeptin and PMSF were not able to protect from drug-induced apoptosis (data not shown). The zVAD inhibitor was also effective in MG63 osteosarcoma cells (data not shown), indicating that caspases are involved in drug-induced apoptosis in different chemosensitive tumor cell types.

Inhibition of chemotherapeutic drug-induced apoptosis by the ICE inhibitor zVAD in different cell lines. CEM and SHEP cells were incubated with 100 μg/mL CR (circles), 100 ng/mL DX (triangles), and 100 μg/mL MX (squares) in the presence or absence of the ICE protease inhibitor zVAD (Enzyme Systems Products, Dublin, CA). Apoptosis was measured as described in Fig 1. SHEP (A) or CEM cells (B) were cotreated with drugs and various concentrations of the inhibitor for 40 or 30 hours, respectively. (C) Effect of delayed addition of zVAD on drug-induced apoptosis in CEM cells. Cells were treated with drugs for 34 hours and then analyzed for cell death. The addition of zVAD (60 μmol/L) was delayed for the indicated time. Data represent the mean ± SD from four experiments with duplicate measurements. Spontaneous apoptosis was less than 10%. The percentage of living cells after 34 hours of drug treatment without the inhibitor was less than 5% for each drug.

Inhibition of chemotherapeutic drug-induced apoptosis by the ICE inhibitor zVAD in different cell lines. CEM and SHEP cells were incubated with 100 μg/mL CR (circles), 100 ng/mL DX (triangles), and 100 μg/mL MX (squares) in the presence or absence of the ICE protease inhibitor zVAD (Enzyme Systems Products, Dublin, CA). Apoptosis was measured as described in Fig 1. SHEP (A) or CEM cells (B) were cotreated with drugs and various concentrations of the inhibitor for 40 or 30 hours, respectively. (C) Effect of delayed addition of zVAD on drug-induced apoptosis in CEM cells. Cells were treated with drugs for 34 hours and then analyzed for cell death. The addition of zVAD (60 μmol/L) was delayed for the indicated time. Data represent the mean ± SD from four experiments with duplicate measurements. Spontaneous apoptosis was less than 10%. The percentage of living cells after 34 hours of drug treatment without the inhibitor was less than 5% for each drug.

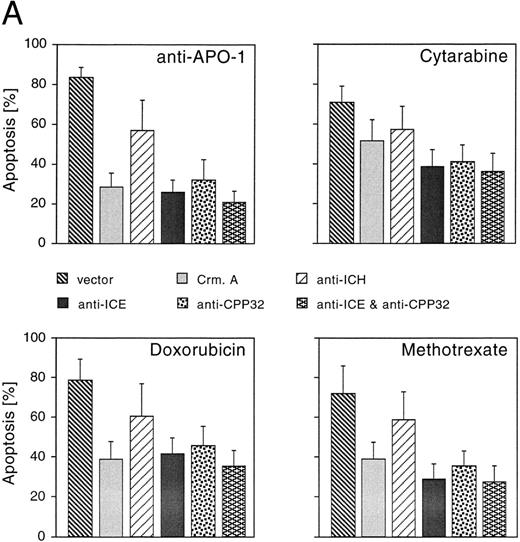

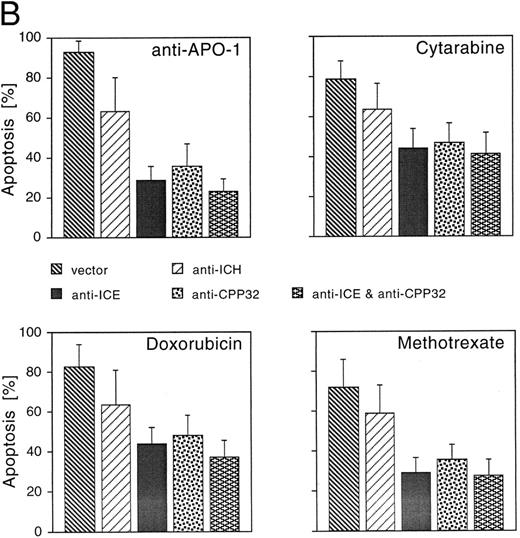

CrmA, antisense-ICE, and antisense-CPP32 protect cells from drug-induced apoptosis. We next studied whether reduced expression of caspases could inhibit cell death induced by CR, DX, and MT. A number of different caspases have recently been identified in mammalian cells.15 Although each of these proteases is able to induce apoptosis upon overexpression, little is known about the functional relevance of individual members of this family of proteases and the redundancy of the system. To gain insights into whether caspases may be involved in drug-induced apoptosis, we used an antisense approach to deplete single caspases. In addition, we overexpressed CrmA, a pox virus-derived serpin that is a specific inhibitor of some caspases and apoptosis.23,31 32 Microinjection of the CrmA expression construct into adherent MG63 cells potently inhibited apoptosis after treatment with anti–APO-1, DX, and MT. CR-induced apoptosis was also significantly reduced, although to a lower extent (Fig 3A). A similar extent of protection was observed after microinjection of antisense-CPP32 into nuclei of MG63 cells. CD95- and drug-induced apoptosis was further inhibited by an antisense-ICE construct. Antisense–ICH-1 was considerably less effective upon treatment with the four apoptosis-inducing agents. Interestingly, combined microinjection of antisense-ICE and antisense-CPP32 did not result in additive effects and protection was not significantly enhanced compared with microinjection of the single antisense constructs.

Effects of CrmA and antisense cDNA constructs complementary to single ICE proteases on apoptosis. (A) Inhibition of apoptosis in MG63 cells by cDNA microinjection. Cells (8 × 105) were seeded in 60-mm tissue dishes. After overnight incubation, cell nuclei were microinjected with a CrmA expression plasmid or antisense constructs targeting ICH-1, ICE, or CPP32. Cell injections were performed with an automatic microinjection system equipped with glass micropipettes loaded with DNA and Texas red-labeled dextran. After 20 hours after microinjection, cells were treated with anti–APO-1, CR, DX, or MT as described in Fig 1 and incubated for a further 48 hours. Anti–APO-1 treatment was applied in the presence of 5 μg/mL cycloheximide, which was not toxic by itself. Cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and inspected microscopically. Microinjected cells were identified by red fluorescent staining. Cells were regarded as apoptotic when they showed membrane blebbing and/or a condensed cell nucleus. At least 180 cells were analyzed for each condition. The values represent the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. (B) Effect of cDNA expression after electroporation of CEM cells. Cells (2 × 108) were transfected the antisense constructs using an electroporator (975 μF, 230 V). After electroporation, cells were seeded at 1 × 106 cells/well in 6-well plates. Eight hours later, cells were treated with G-418 to deplete untransfected cells. Dead cells were removed after a further 36 hours by a washing step in a Ficoll-Paque gradient. The enriched population containing 65% to 88% of transfected cells was then treated with anti–APO-1 for 4 hours or with CR, DX, or MT at the concentrations indicated in Fig 1 for 20 hours. Apoptosis was measured by propidium iodide/Hoechst 33342 uptake using flow cytometry. Data are given as the mean percentage of cell death from four experiments with duplicate samples.

(C) Morphologic analysis of doxorubicin-induced apoptosis after microinjection of CrmA cDNA and antisense constructs complementary to ICE family members in SHEP cells. Cells were microinjected as described in (A) using 0.2% Texas red-dextran together with cDNA constructs encoding (a) empty pCDNA-3 vector, (b) pSV25S-CrmA, (c) antisense ICE, and (d) antisense CPP32. Eight hours after transfection, cells were treated with anti–APO-1, CR, DX, and MT and evaluated 30 hours later by two independent scientists. Microinjected cells were identified by red fluorescent staining (left panel) and are indicated by arrows (right panel). The scale bar represents 20 μm. Quantitative values of specific inhibition after scoring of about 300 cells were 58% for CrmA, 62% for pCDNA-3-a300h.ICE, 61% for pCDNA-3-a300h.CPP32, and 64% for the mixture of ICE and CPP32 antisense constructs microinjected together.

(D) Long-term protection from drug-induced apoptosis by antisense constructs. CEM cells were transfected with empty vector, antisense ICE, or CPP32 constructs and selected in G418-containing medium for 36 hours. Cells were then treated with the indicated cytotoxic drugs. After 30 hours, cells were harvested and limiting dilutions (1:3) were performed, starting from 3 × 104 cells per well. Cell viability was assayed by trypan blue exclusion after 14 days. The highest dilutions still containing living cells are indicated. Samples of cells transfected with control vector did not contain living cells after 14 days of drug treatment; therefore, the vector alone bar is not included. Control indicates the clonogenicity of vector-transfected cells without drug treatment. The data represent experiments with quadruplicated samples. Standard deviations were in the range of one dilution step.

Effects of CrmA and antisense cDNA constructs complementary to single ICE proteases on apoptosis. (A) Inhibition of apoptosis in MG63 cells by cDNA microinjection. Cells (8 × 105) were seeded in 60-mm tissue dishes. After overnight incubation, cell nuclei were microinjected with a CrmA expression plasmid or antisense constructs targeting ICH-1, ICE, or CPP32. Cell injections were performed with an automatic microinjection system equipped with glass micropipettes loaded with DNA and Texas red-labeled dextran. After 20 hours after microinjection, cells were treated with anti–APO-1, CR, DX, or MT as described in Fig 1 and incubated for a further 48 hours. Anti–APO-1 treatment was applied in the presence of 5 μg/mL cycloheximide, which was not toxic by itself. Cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and inspected microscopically. Microinjected cells were identified by red fluorescent staining. Cells were regarded as apoptotic when they showed membrane blebbing and/or a condensed cell nucleus. At least 180 cells were analyzed for each condition. The values represent the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. (B) Effect of cDNA expression after electroporation of CEM cells. Cells (2 × 108) were transfected the antisense constructs using an electroporator (975 μF, 230 V). After electroporation, cells were seeded at 1 × 106 cells/well in 6-well plates. Eight hours later, cells were treated with G-418 to deplete untransfected cells. Dead cells were removed after a further 36 hours by a washing step in a Ficoll-Paque gradient. The enriched population containing 65% to 88% of transfected cells was then treated with anti–APO-1 for 4 hours or with CR, DX, or MT at the concentrations indicated in Fig 1 for 20 hours. Apoptosis was measured by propidium iodide/Hoechst 33342 uptake using flow cytometry. Data are given as the mean percentage of cell death from four experiments with duplicate samples.

(C) Morphologic analysis of doxorubicin-induced apoptosis after microinjection of CrmA cDNA and antisense constructs complementary to ICE family members in SHEP cells. Cells were microinjected as described in (A) using 0.2% Texas red-dextran together with cDNA constructs encoding (a) empty pCDNA-3 vector, (b) pSV25S-CrmA, (c) antisense ICE, and (d) antisense CPP32. Eight hours after transfection, cells were treated with anti–APO-1, CR, DX, and MT and evaluated 30 hours later by two independent scientists. Microinjected cells were identified by red fluorescent staining (left panel) and are indicated by arrows (right panel). The scale bar represents 20 μm. Quantitative values of specific inhibition after scoring of about 300 cells were 58% for CrmA, 62% for pCDNA-3-a300h.ICE, 61% for pCDNA-3-a300h.CPP32, and 64% for the mixture of ICE and CPP32 antisense constructs microinjected together.

(D) Long-term protection from drug-induced apoptosis by antisense constructs. CEM cells were transfected with empty vector, antisense ICE, or CPP32 constructs and selected in G418-containing medium for 36 hours. Cells were then treated with the indicated cytotoxic drugs. After 30 hours, cells were harvested and limiting dilutions (1:3) were performed, starting from 3 × 104 cells per well. Cell viability was assayed by trypan blue exclusion after 14 days. The highest dilutions still containing living cells are indicated. Samples of cells transfected with control vector did not contain living cells after 14 days of drug treatment; therefore, the vector alone bar is not included. Control indicates the clonogenicity of vector-transfected cells without drug treatment. The data represent experiments with quadruplicated samples. Standard deviations were in the range of one dilution step.

Cross-inhibition of protease expression by antisense constructs. Cells were electroporated with the respective constructs and enriched for transfection by G418 treatment as indicated in the Materials and Methods. Protein extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis as described. In addition, films were evaluated by densitometry using HEROLAB system (Herolab Molekulare Trenntechnik, Wiesloch, Germany) equiped with EASY software (data not shown). The level of protease expression in empty vector-transfected cells was given as 100%. In SHEP cells, pCDNA-3-α300h.ICE decreased caspase-1 expression to 23% and caspase-3 expression to 26%. In CEM cells, pCDNA-3-α300h.ICE inhibited caspase-1 expression to 21% and caspase-3 expression to 25%. pCDNA-3-α300h.CPP32 inhibited caspase-3 expression to 24% in SHEP and to 21% in CEM cells, but there was no cross-inhibition of caspase-1 expression by this construct. Experiments have been performed twice, with differences between experiments of less than 12%.

Cross-inhibition of protease expression by antisense constructs. Cells were electroporated with the respective constructs and enriched for transfection by G418 treatment as indicated in the Materials and Methods. Protein extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis as described. In addition, films were evaluated by densitometry using HEROLAB system (Herolab Molekulare Trenntechnik, Wiesloch, Germany) equiped with EASY software (data not shown). The level of protease expression in empty vector-transfected cells was given as 100%. In SHEP cells, pCDNA-3-α300h.ICE decreased caspase-1 expression to 23% and caspase-3 expression to 26%. In CEM cells, pCDNA-3-α300h.ICE inhibited caspase-1 expression to 21% and caspase-3 expression to 25%. pCDNA-3-α300h.CPP32 inhibited caspase-3 expression to 24% in SHEP and to 21% in CEM cells, but there was no cross-inhibition of caspase-1 expression by this construct. Experiments have been performed twice, with differences between experiments of less than 12%.

Similar results were obtained after transfection of the constructs in nonadherent CEM cells by electroporation (Fig 3B). Subsequently, cells were incubated in G418-containing selection medium resulting in an enrichment of transfected cells 65% to 80%. Corresponding to the previous experiment, drug-induced apoptosis in CEM cells was also inhibited by antisense constructs to a similar extent as CD95-induced apoptosis. Microinjection of SHEP cells showed similar quantitative results compared with MG63 and CEM cells (data not shown). Morphologic analysis of a typical microinjection experiment in SHEP cells is shown in Fig 3C. Microinjection of SHEP cells with empty vector or antisense–ICH-1 did not significantly influence cell death induced by DX (Fig 3C, a). Both injected and noninjected cells displayed apoptotic morphology with membrane blebbing, cell shrinkage, and chromatin condensation. In contrast, cells microinjected with CrmA or antisense constructs for ICE or CPP32 showed significant resistance against DX (Fig 3C, b through d). As in CEM or MG63 cells, combined microinjection of antisense-ICE and antisense-CPP32 in SHEP cells was not superior compared with individual constructs. This may be due to the fact that both proteases are integral parts of an overlapping pathway or that caspase-3 may ultimately become activated through activated caspase-2. Antisense-ICE microinjected SHEP cells were able to proliferate (Fig 3C, c), whereas mitotic divisions were infrequently observed in antisense-CPP32 microinjected cells. Microinjection of MG63 or SHEP cells with empty vector or antisense-ICH-1 did not significantly influenced drug-induced cell death (Fig 3A and C). To investigate whether inhibition of caspases is also able to provide long-term protection from drug treatment, we further performed limiting dilution assays (Fig 3D). In these experiments, MT, DX, and CR completely killed CEM cells transfected with the parental vector even in undiluted cell suspensions. In contrast, samples of cells transfected with antisense-ICE could be diluted more than 80-fold and still showed living cells 14 days after drug treatment. Transfection of antisense-CPP32 was less protective. The results therefore indicate that expression of antisense-caspase constructs promotes cell survival even for prolonged period of time. To investigate the differences found in the protective effect of antisense-ICE and antisense-CPP32, we analyzed the efficacy of our antisense constructs to downregulate expression of caspases by Western blot. As shown in Fig 4 the pCDNA-3-a300hICE was able to inhibit not only expression of caspase-1 but also significantly reduced expression of caspase-3. On the other hand, pCDNA-3-a300hCPP32 construct reduced expression of caspase-3 but did not significantly downregulate expression of caspase-1. Better survival of cells transfected with pCDNA-3-a300hICE could therefore be explained by a broader inhibitory potential.

Caspase activation in sensitive, CD95-resistant, and DX-resistant CEM cells. Sensitive (CEM), CD95-resistant CEM (CEMCD95-R), and DX-resistant CEM cells (CEMDX-R) were treated for 1.5 hours with anti–APO-1 (1 μg/mL). Caspase activity was measured by FACS analysis as described in Fig 1.

Caspase activation in sensitive, CD95-resistant, and DX-resistant CEM cells. Sensitive (CEM), CD95-resistant CEM (CEMCD95-R), and DX-resistant CEM cells (CEMDX-R) were treated for 1.5 hours with anti–APO-1 (1 μg/mL). Caspase activity was measured by FACS analysis as described in Fig 1.

Deficient activation of caspases in doxorubicin- and CD95-resistant cell lines after anti–APO-1 treatment. Because caspases were shown to be centrally involved in both drug- and CD95-induced apoptosis, we analyzed caspase activity after incubation with anti–APO-1 in DX-resistant (CEMDX-R) and anti–APO-1 — resistant (CEMCD95-R) cells. As shown in Fig 5, caspase activity only minimally increased after CD95 triggering in both resistant cell lines compared with parental CEM cells. The data on cross-resistance of CD95-induced and drug-induced apoptosis further suggest that activation of caspases is required for drug-induced cell death and imply that defective activation of caspases could be a resistance mechanism to escape drug-induced apoptosis.

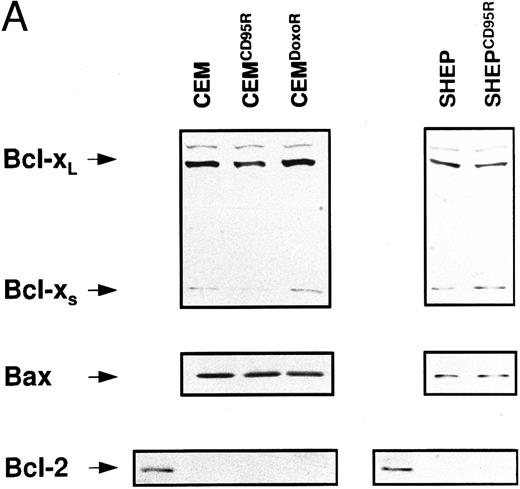

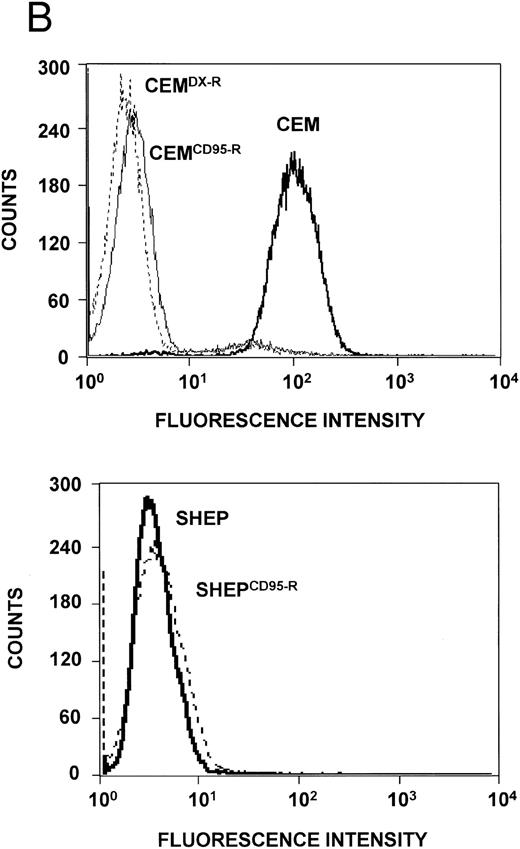

Expression levels of Bcl-2–related proteins and P-gp (MDR-1). (A) Expression of Bcl-2–related proteins. Western blot analysis of CEM, CD95-resistant CEM (CEMCD95-R), DX-resistant CEM (CEMDX-R), SHEP, and CD95-resistant SHEP (SHEPCD95-R) cell lysates was performed using mouse anti–Bcl-2 monoclonal, rabbit anti–Bcl-xL polyclonal, and rabbit anti-Bax polyclonal antibody and ECL. (B) Assessment of P-gp (MDR-1) expression. P-gp expression of CEM (solid line), CD95-resistant CEM (CEMCD95-R; thin line), DX-resistant CEM cells (CEMDX-R; broken line), SHEP (solid line), and CD95-resistant SHEP cells (SHEPCD95-R; broken line) was determined by FACS analysis using P-gp (MDR-1) monoclonal antibody UIC2. Representative experiments of three performed are shown.

Expression levels of Bcl-2–related proteins and P-gp (MDR-1). (A) Expression of Bcl-2–related proteins. Western blot analysis of CEM, CD95-resistant CEM (CEMCD95-R), DX-resistant CEM (CEMDX-R), SHEP, and CD95-resistant SHEP (SHEPCD95-R) cell lysates was performed using mouse anti–Bcl-2 monoclonal, rabbit anti–Bcl-xL polyclonal, and rabbit anti-Bax polyclonal antibody and ECL. (B) Assessment of P-gp (MDR-1) expression. P-gp expression of CEM (solid line), CD95-resistant CEM (CEMCD95-R; thin line), DX-resistant CEM cells (CEMDX-R; broken line), SHEP (solid line), and CD95-resistant SHEP cells (SHEPCD95-R; broken line) was determined by FACS analysis using P-gp (MDR-1) monoclonal antibody UIC2. Representative experiments of three performed are shown.

Expression of Bcl-2 family members and MDR-1 in apoptosis resistant CEM and SHEP cells. Resistance to chemotherapy has been attributed to various mechanisms such as overexpression of P-glycoprotein (MDR-1)36 or imbalance of antiapoptotic and proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members.38 We therefore investigated whether one of these mechanisms would contribute to the resistance phenotype in our experimental system. Western blot analysis showed no difference in expression levels of Bcl-2, Bcl-x, and Bax proteins in resistant CEM and SHEP cells as compared with the parental cell lines (Fig 6A). P-gp expression varied among CEM cell lines, with highest expression in sensitive CEM cells, whereas both SHEP and CD95-resistant SHEP cells did not express detectable levels of P-gp (Fig 6B).

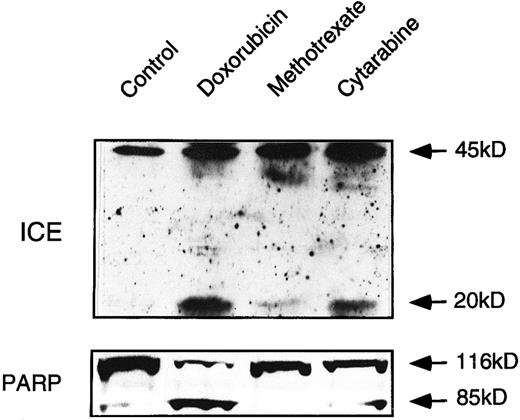

Drug-induced activation of caspases in ex vivo-derived leukemia cells follows the pattern of drug sensitivity. To confirm the data obtained in cell lines, we investigated drug-induced activation of caspases in leukemia cells from a patient with T-cell leukemia. Ex vivo-derived leukemia cells were incubated with DX, MT, and CR. After 24 hours, induction of specific apoptosis could be measured with DX (60%) and CR (25%). MT only induced 5% to 10% specific apoptosis. Immunoblot analyses showed that DX and CR treatment indeed yielded the characteristic processed fragments of caspase-1 and PARP (Fig 7). However, caspase-1 processing and PARP cleavage were only slightly induced after MT treatment. This finding suggests that our basic observations obtained with different cell lines are fundamental to drug sensitivity of primary human cancer cells.

ICE processing and PARP cleavage in ex vivo-derived leukemia cells. Extracts obtained from cells treated with the indicated cytotoxic drugs were processed as described in methodology and analyzed by immunoblotting for ICE processing and PARP cleavage. Mononuclear cells containing more than 95% of leukemia blasts were separated from whole heparinized blood by Ficoll-Paque gradient centrifugation. Because of the shortage of patient material, the experiment has been performed once only.

ICE processing and PARP cleavage in ex vivo-derived leukemia cells. Extracts obtained from cells treated with the indicated cytotoxic drugs were processed as described in methodology and analyzed by immunoblotting for ICE processing and PARP cleavage. Mononuclear cells containing more than 95% of leukemia blasts were separated from whole heparinized blood by Ficoll-Paque gradient centrifugation. Because of the shortage of patient material, the experiment has been performed once only.

DISCUSSION

Antineoplastic drugs have previously been shown to cause apoptosis similar to known physiologic cell death pathways.3 We have recently described that DX-induced apoptosis in leukemia cells involves gene expression and induces a cell death mechanism that depends on CD95 ligand-receptor interaction similar to the autocrine suicide in activated T cells.43 In the present report, we show that chemosensitivity also depends on activation of caspases that are an integral part of the CD95 signalling pathway. Any interference with the activity of these proteases leads to a chemoresistant phenotype. This is supported by different experimental approaches. First, caspase activity is observed in drug-sensitive but not drug-resistant derivatives after treatment with drugs. Second, interference with caspase activity, either by a peptide inhibitor or ectopic expression of CrmA, significantly attenuated drug-induced cytotoxicity. Third, antisense experiments targeting distinct members of caspases lead to a chemoresistant phenotype both in short-term and long-term experiments. Lastly, direct activation of certain caspases was observed in response to drug treatment by measuring processing of relevant caspase precursors and its proteolytic activity in all cell lines and patient-derived leukemia cells. Activation of caspases may be the ultimate effector mechanism in apoptotic pathways induced by different, structurally unrelated cytotoxic drugs. Malfunction of those death-executing pathways may be clinically reflected as chemoresistance. Together with recent reports on activation of caspases on drug treatment44-46 and the finding of caspase cleavage upon drug treatment in primary tumor cells ex vivo, our data indicate that caspases play an important role in drug sensitivity of tumor cells in vivo.

The molecular mechanisms leading to proteolytic activation of caspases during initiation of apoptosis in general are unknown. In the CD95 system, cleavage of caspases may be a consequence of the signalling cascade that follows multimerization of the receptor and the assembly of signal transduction molecules that become phosphorylated upon binding to the intracellular death domain of CD95.47-49 Because drug-induced activation of caspases requires several hours, additional signalling programs may have to be activated. Upon drug incubation, CD95 ligand is induced in leukemia and solid tumor cells and may initiate CD95-mediated activation of caspases.39 However, CD95 ligand is not induced in MG63 cells after drug treatment (data not shown), suggesting that other mechanisms may also lead to activation of caspases in these cells. These mechanisms may include ceramide generation by membrane-bound or lysosomal sphingomyelinases. The sphingomyelin pathway has previously been shown to be triggered by some cytotoxic drugs and CD95.50-52

The physiologic relevance of individual members of the caspase family is presently not well defined. Many cells express more than one of these proteases, but whether all are functionally required for a single apoptotic pathway remains obscure. Current knowledge indicates that single members of the caspase family have distinct substrate specificities, inhibitor profiles, and ability to process each other,15 17 suggesting that caspases may form a hierarchical although redundant network that may function as an amplifier for a given apoptotic stimulus. The blocking efficiency of the caspase-3 construct was comparable to a similar antisense construct to caspase-1 in short-term assays, whereas an antisense construct derived from caspase-2 cDNA was considerably less effective. Interestingly, the combined transfection of caspase-1 and -3 did not result in additive protection, suggesting that both proteases are integral parts of the same signalling cascade. Because the ability to block the expression of genes by a given antisense construct largely depends on its sequence homology, we calculated the cross-homology of the antisense constructs to known caspases (by BESTFIT; GCG, Madison, WI). Sequence alignment showed the highest overall homology of the anti-ICE construct to known caspases, which may explain our finding that the anti-ICE construct also inhibited the expression of other caspases, thereby providing the best long-term protective effect in our assays. In contrast, antisense ICH-1, which shows the lowest overall homology, may only weakly interfere with synthesis of other caspases. An important observation is the finding that inhibition of caspases not only retarded the apoptotic process but also provided protection from drug-induced death for up to 2 weeks. Thus, any impairment in the protease effector phase of apoptosis may lead to chemoresistance against several anticancer drugs.

The elucidation of cross-resistance between CD95 and anticancer drugs may have profound implications for the treatment of tumors resistant to chemotherapy. Failure to activate caspases was not due to other well-characterized resistance mechanisms such as overexpression of antiapoptotic Bcl-2–related proteins or increased expression of P-gp (MDR-1). In addition, consistent with previous reports,53 we found a slight (up to 1.5-fold) increase in intracellular glutathione levels in resistant cells compared with parental cell lines (data not shown). Cross-resistance between drug- and CD95-mediated apoptosis in some cases may involve downregulation of CD95 expression54 (Friesen et al, manuscript submitted). Our findings indicate that defective downstream signalling events such as deficient activation of caspases also contribute to cross-resistance. Defects at the level of caspase activation may even be more crucial than downregulation of CD95 for cross-resistance between drug- and CD95-mediated apoptosis in view of recently published data showing that drug-resistant cell lines that partly reverted to sensitivity regained CD95 expression, but still remained resistant to CD95-induced apoptosis.54 In addition, our findings may have implications for immunotherapy of cancer. Modulation of an antitumor immune response presents an alternative treatment option for malignancies resistant to conventional therapies. However, because drug-induced apoptosis and apoptosis mediated by cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) activity depend on caspases as death effector molecules,19 resistance at the level of caspases would render tumor cells unresponsive to both chemotherapy and immunotherapy. The crucial requirement of caspases in resistance or sensitivity towards drug-induced cell death provides a new molecular understanding of sensitivity and resistance of tumor cells for chemotherapy and may also provide new targets for rational drug development.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Dr J.M. deMurcia for providing anti-PARP antiserum, K. Hexel for help with flow cytometry, R. Fischer for assisting with the microinjections, and S. Commendatore and G. Hölzl-Wenig for excellent technical help.

Address reprint requests to Klaus-Michael Debatin, MD, PhD, University Children's Hospital, Prittwitzstr 43, D-89075 Ulm, Germany.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal