Abstract

While the precipitation of unstable variant β-globin chains has been implicated as a major pathogenic mechanism in dominantly inherited β thalassemia, their instability and presence in intra-erythroblastic inclusions have not been conclusively shown. We report the investigation of two cases of dominantly inherited β thalassemia due to heterozygosity for the β-codon 121 G-T mutation. In one case, we were able to demonstrate the presence of an abnormal β-globin chain in both peripheral blood reticulocytes and bone marrow erythroblasts, and to assess its stability in relation to the substantial amounts of mutant β mRNA transcript. The serum transferrin receptor (TfR) level was markedly increased, an indication of increased erythropoietic activity. In both cases, we could show by immunoelectron microscopy that the intra-erythroblastic inclusion bodies, a prominent feature of diseases in this category, contained not only precipitated α-globin chains, but also β chains. The data confirm previous suggestions that the cellular pathology underlying this group of β thalassemias is related to the synthesis of highly unstable β-globin chain variants, which fail to form functional tetramers and precipitate intracellularly with the concomitant excess α chains, leading to increased ineffective erythropoiesis.

THE DOMINANTLY inherited β thalassemias are a group of disorders in which the inheritance of a single β-thalassemia allele, in the presence of normal α genes, results in a clinically detectable phenotype.1 By contrast, individuals heterozygous for typical β thalassemia are asymptomatic. Apart from the usual features of heterozygous β thalassemia, such as increased levels of HbA2 and increased α/β-globin chain biosynthesis ratios, this group of disorders is also characterized by morphologic evidence of a substantial degree of dyserythropoiesis associated with the presence of large intra-erythroblastic inclusions.2-7

A spectrum of different mutations affecting the β-globin gene has been identified in families with this form of β thalassemia, including the G-T mutation in codon 121, which introduces premature termination of translation.1,7,8 In a previous study of this mutant β allele, a minute amount of the truncated β-chain variant could be demonstrated and instability of the β-globin variant was suggested, although no formal assessment of its instability was made.9

We report our investigation of two individuals with thalassemia intermedia due to heterozygosity for the β-globin codon 121 G-T mutation. Peripheral reticulocytes showed that the level of mutant β mRNA was at least equal to normal β mRNA. Globin-chain biosynthesis studies in one subject demonstrated marked instability of the β-chain variant. Large inclusion bodies were present in the bone marrow erythroblasts of both subjects. The composition of these inclusion bodies was investigated by immunoelectron microscopy, which clearly demonstrated the presence of both precipitated α- and β-globin chains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Hematologic studies.Blood samples were collected in edathamil (EDTA) as anticoagulant and full blood profiles obtained using an automated cell counter. Fresh blood (10 mL) and bone marrow aspirate were collected in heparin and kept on ice for globin-chain biosynthesis studies (described later). Hemoglobin (Hb) analyses and HbA2 and HbF levels were measured using standard techniques. Informed consent was obtained in both cases before the collection of blood and bone marrow samples.

RNA and DNA analyses.Total cytoplasmic RNA was extracted using Ultraspec (Biotecx Laboratories, Houston, TX) by adding 200 μL spun washed peripheral erythrocytes to 1 mL Ultraspec, followed by extraction with chloroform and isopropanol precipitation. A 200-ng quantity of total RNA was reverse transcribed (RT) into cDNA using an oligo (dT)15 primer and avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase; β-globin cDNA was then enzymatically amplified by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers A (5′-TGA GGA GAA GTC TGC CGT TAC -3′ ) and B (5′- CCC CAG TTT AGT AGT TGG ACT TA -3′ ). Primer A is specific for a sequence in exon 1 of the β-globin gene and primer B is specific for a sequence in the 3′ flanking region. Full details of the PCR conditions have been described.10 The PCR product of 497 bp was digested with the restriction enzyme EcoRI and the digests analyzed on a 2% agarose gel.

DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes using standard methods. The β-globin genes were directly sequenced after enzymatic amplification by PCR; DNA sequences of the oligonucleotide primers and thermal cycling conditions have been described.7 For confirmation of the codon 121 G-T mutation, a 1,224-bp segment of the β-globin gene was PCR-amplified using primers C (5′- CAA TGT ATC ATG CCT CTT TGC AC -3′ ) and D (5′- GGG CCT ATG ATA GGG TAA TAA G -3′ ) and subjected to EcoRI restriction analysis.

Globin-chain biosynthesis.Bone marrow cells (erythroid precursors) and peripheral blood reticulocytes were kept on ice until they were incubated at 37°C with 3H-leucine as previously described.11 Leukocytes were removed from the blood before incubation using α-cellulose and microcrystalline cellulose (Sigmacell 50; Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO). Time-course incubation was performed, with aliquots removed at 2, 5, 15, and 60 minutes; biosynthesis was stopped by the addition of cold reticulocyte saline (0.13 mol/L NaCl, 0.005 mol/L KCl, 0.007 mol/L MgCl2 ), followed by acid-acetone precipitation of the globin from whole cells. The globin chains were separated by cation-exchange chromatography on carboxymethyl cellulose and the radioactive incorporation into each fraction measured by scintillation counting. Both total radioactivity and specific activities of the various globin-chain fractions were measured and the globin-chain biosynthesis ratios calculated.

Electron microscopy and immunostaining.The anti-human α-globin chain mouse monoclonal antibody was obtained from Immuno-rx (Augusta, GA). The anti-human β-globin chain mouse monoclonal antibody (culture supernatant) was generously supplied by Dr S. Thorpe, National Institute of Biological Standards,12 as was anti-human γ-globin chain mouse monoclonal antibody.

Bone marrow from the propositus (case no. 1) of family no. 2 reported by Thein et al7 and from a new patient (case no. 2) with thalassemia intermedia were studied. The marrow fragments were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer (pH 7.3), postfixed in buffered 1% osmium tetroxide, stained with aqueous uranyl acetate, and embedded in Araldite (Agar Scientific Ltd, Essex, UK). Archival blocks of marrow from two patients with β-thalassaemia major, which had been processed as described earlier, were also studied. Sections were cut to silver interference colors, floated on to nickel grids, treated with a saturated solution of sodium metaperiodate for 30 minutes followed by 0.01 mol/L sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 70°C for 5 minutes, and washed sequentially in citrate buffer and distilled water.13 Sections to be incubated with monoclonal antibody against α-globin chains were placed on a drop of phosphate-buffered saline that contained 15% normal goat serum to prevent nonspecific binding of antibody. Sections were incubated overnight with drops of anti–α- or anti–β-globin chain antibody (undiluted or diluted 1:10 or 1:100), washed in buffer, and incubated with goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) conjugated to 10 nm colloidal gold. In control sections, the anti–globin-chain antibody was either omitted or replaced with normal mouse serum or monoclonal antibody to γ-globin chains. After counterstaining with aqueous uranyl acetate, the sections were viewed in a Philips EM300 electron microscope (Eindhoven, The Netherlands).

Transferrin receptor assay.Soluble transferrin receptor (TfR) was measured in quadruplicate on heparinized plasma, using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Control samples from 44 normal individuals, 11 β-thalassemia traits, 12 HbE traits, 20 untransfused HbE/β thalassemias, 1 Hb Bristol heterozygote (β67 [E11] Val-Met → Asp; an unstable β-globin variant), and 1 Hb Sun Prairie homozygote (α130 [H13] Ala-Pro; an unstable α-globin variant) were assayed in duplicate.

RESULTS

Clinical details of case no. 1 have been reported (propositus in family no. 2).7 The second propositus (case no. 2) is a 58-year-old English man (of Anglo-Saxon origin) who presented with anemia (Hb, 7.5 to 10 g/dL) and splenomegaly. A peripheral blood smear showed hypochromic microcytosis (mean corpuscular volume [MCV] 67 fL; mean corpuscular Hb [MCH], 22 pg), marked basophilic stippling, and reticulocytosis (4%). The HbA2 level was 4.3%, and HbF 3.0%. Serum bilirubin (67 μmol/L) and ferritin (482 μg/L) levels were elevated. A bone marrow examination showed marked dyserythropoiesis, and large inclusion bodies were detected in the erythroid precursors on staining with methyl violet. His 31-year-old daughter had previously presented with anemia during pregnancy with the following hematologic profile: Hb, 9.0 g/dL; MCV, 64 fL; MCH, 19.5 pg; reticulocytes, 4.3%; HbA2 , 4.8%; HbF, 1.1%; and similar blood film appearances.7

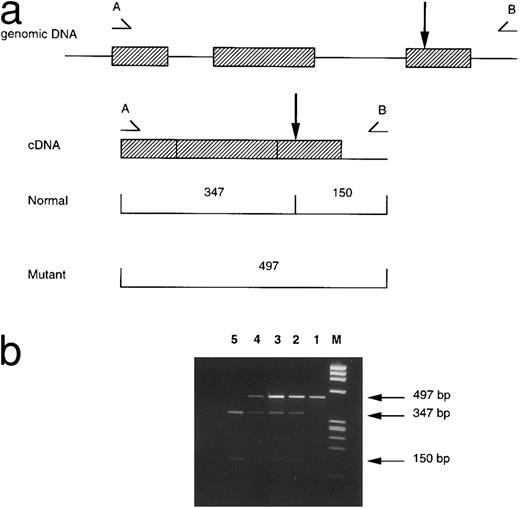

Patient no. 2 was found to be heterozygous for β-codon 121 G-T on sequencing of the β-globin genes, as was previously found in his daughter. As the mutation abolishes a restriction site for EcoRI, this was confirmed by restriction analysis of the amplified β-globin gene and β cDNA fragments (Fig 1). The amount of mutant β cDNA was at least equal to the normal β cDNA as assessed by the intensity of ethidium bromide staining, similar to two other heterozygotes for the β-codon 121 G-T with thalassemia intermedia which were also assessed concurrently.

Detection of the β-codon 121 G-T mutation by restriction analysis. (a) A 497-bp fragment of β cDNA is amplified by the primers A (5′-TGA GGA GAA GTC TGC CGT TAC-3′ ) and B (5′-CCC CAG TTT AGT AGT TGG ACT TA-3′ ). The EcoRI restriction site is indicated by the arrow; this is abolished by the β-codon 121 mutation. EcoRI digestion produces 2 fragments of 347 and 150 bp from the normal allele, and a single uncut 497-bp fragment from the mutant allele. (b) Ethidium bromide–stained 2% agarose gels of electrophoresed EcoRI-digested β cDNA. The lanes are represented by M:ΦX174 RF DNA/HaeIII marker; 1, Uncut fragment; 2, case no. 2; 3, case no. 1; 4, positive control for codon 121 G-T; 5, normal control.

Detection of the β-codon 121 G-T mutation by restriction analysis. (a) A 497-bp fragment of β cDNA is amplified by the primers A (5′-TGA GGA GAA GTC TGC CGT TAC-3′ ) and B (5′-CCC CAG TTT AGT AGT TGG ACT TA-3′ ). The EcoRI restriction site is indicated by the arrow; this is abolished by the β-codon 121 mutation. EcoRI digestion produces 2 fragments of 347 and 150 bp from the normal allele, and a single uncut 497-bp fragment from the mutant allele. (b) Ethidium bromide–stained 2% agarose gels of electrophoresed EcoRI-digested β cDNA. The lanes are represented by M:ΦX174 RF DNA/HaeIII marker; 1, Uncut fragment; 2, case no. 2; 3, case no. 1; 4, positive control for codon 121 G-T; 5, normal control.

Cation-exchange chromatography showed three main protein peaks in both blood and bone marrow, with the two largest corresponding to β- and α-globin chains (Fig 2); a third, much smaller, protein peak eluted before the β chain (βX on Fig 2), in a position where one would predict the truncated β121 chain to run. The peaks of radioactive incorporation occur in positions corresponding to the protein peaks; however, it is evident that the amount of incorporation of radioactivity into peak βX relative to the amount of protein in the peak is much greater than that for the α- and βA-globin chains, ie, protein βX, presumably the truncated β chain, has a high specific activity relative to α and β globin (Table 1). The α/βA total counts ratio corresponding to the relative rates of synthesis of these chains, after 60 minutes, is 2.4 in bone marrow and 3.9 in blood. This figure does not change significantly over the period of incubation. However, if the truncated β chain is included, the synthesis becomes much more balanced, 1.1 in marrow and 1.9 in blood. The α/βA specific activity ratio is similar to the total counts ratio, in both blood and marrow; however, the α/βX and βA/βX specific activity ratios differ greatly from the total counts ratios, reflecting the high specific activity of βX.

Cation-exchange chromatography on globin (case no. 2) from (A) peripheral blood and (B) bone marrow following incubation with tritiated leucine for 60 minutes. Solid line shows radioactive incorporation (counts per minute), and dotted line, absorbance at 280 nm.

Cation-exchange chromatography on globin (case no. 2) from (A) peripheral blood and (B) bone marrow following incubation with tritiated leucine for 60 minutes. Solid line shows radioactive incorporation (counts per minute), and dotted line, absorbance at 280 nm.

Biosynthesis Studies of Bone Marrow Erythroblasts and Peripheral Reticulocytes From Patient No. 2

| Time (mins) . | α/β A . | α/β X . | β A/β X . | α/( βA + β X) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marrow | ||||

| 2 | ||||

| Total counts | 2.7 | 2 | 0.71 | 1.2 |

| Specific activity | 2.8 | 0.24 | 0.08 | |

| 5 | ||||

| Total counts | 2.7 | 1.7 | 0.63 | 1 |

| Specific activity | 2.5 | 0.23 | 0.09 | |

| 15 | ||||

| Total counts | 2.8 | 2 | 0.71 | 1.1 |

| Specific activity | 2.2 | 0.22 | 0.1 | |

| 60 | ||||

| Total counts | 2.4 | 2.1 | 0.91 | 1.1 |

| Specific activity | 2 | 0.13 | 0.07 | |

| Blood | ||||

| 2 | ||||

| Total counts | 3.7 | 2.1 | 0.59 | 1.3 |

| Specific activity | 2.7 | 0.25 | 0.09 | |

| 5 | ||||

| Total counts | 3.7 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 1.2 |

| Specific activity | 3.5 | 0.18 | 0.05 | |

| 15 | ||||

| Total counts | 4.1 | 2.3 | 0.59 | 1.5 |

| Specific activity | 3.5 | 0.31 | 0.09 | |

| 60 | ||||

| Total counts | 3.9 | 3.8 | 1 | 1.9 |

| Specific activity | 2.9 | 0.31 | 0.11 |

| Time (mins) . | α/β A . | α/β X . | β A/β X . | α/( βA + β X) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marrow | ||||

| 2 | ||||

| Total counts | 2.7 | 2 | 0.71 | 1.2 |

| Specific activity | 2.8 | 0.24 | 0.08 | |

| 5 | ||||

| Total counts | 2.7 | 1.7 | 0.63 | 1 |

| Specific activity | 2.5 | 0.23 | 0.09 | |

| 15 | ||||

| Total counts | 2.8 | 2 | 0.71 | 1.1 |

| Specific activity | 2.2 | 0.22 | 0.1 | |

| 60 | ||||

| Total counts | 2.4 | 2.1 | 0.91 | 1.1 |

| Specific activity | 2 | 0.13 | 0.07 | |

| Blood | ||||

| 2 | ||||

| Total counts | 3.7 | 2.1 | 0.59 | 1.3 |

| Specific activity | 2.7 | 0.25 | 0.09 | |

| 5 | ||||

| Total counts | 3.7 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 1.2 |

| Specific activity | 3.5 | 0.18 | 0.05 | |

| 15 | ||||

| Total counts | 4.1 | 2.3 | 0.59 | 1.5 |

| Specific activity | 3.5 | 0.31 | 0.09 | |

| 60 | ||||

| Total counts | 3.9 | 3.8 | 1 | 1.9 |

| Specific activity | 2.9 | 0.31 | 0.11 |

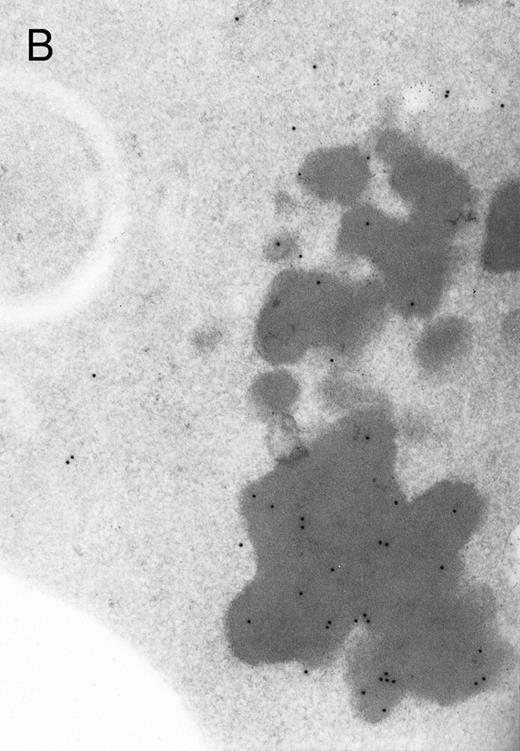

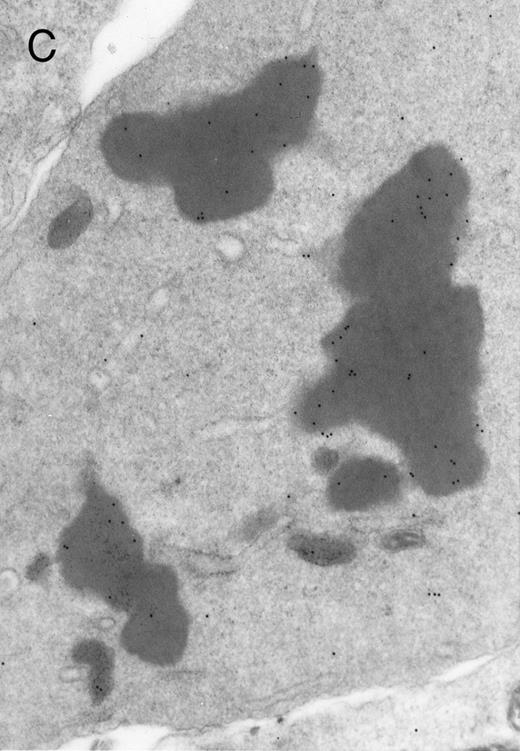

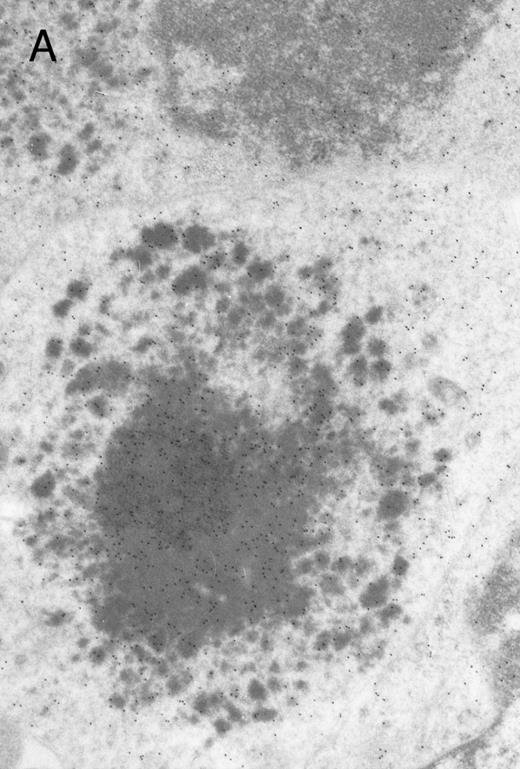

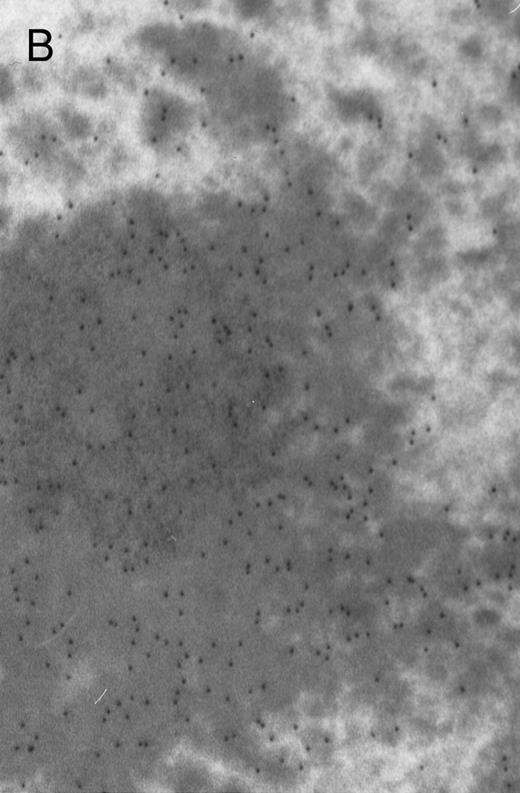

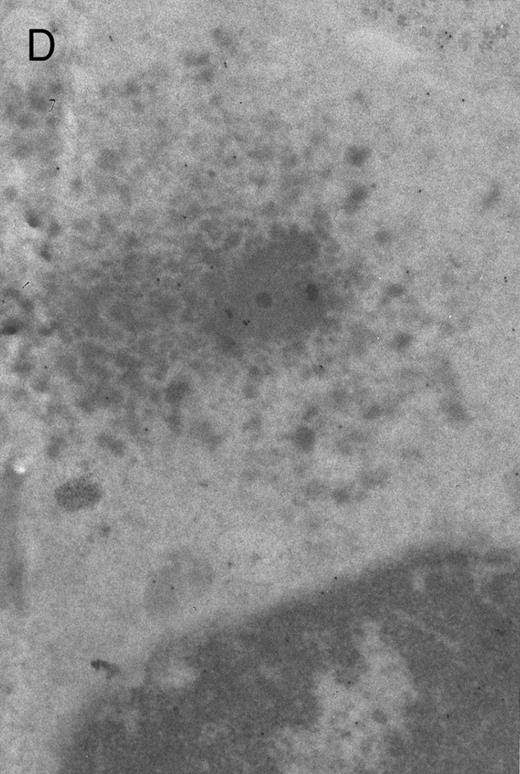

In both cases no. 1 and no. 2, electron microscope studies demonstrated electron-dense inclusions in 30% of early and late polychromatic erythroblast sections and many marrow reticulocytes. In ultrathin sections that reacted with monoclonal antibodies to either α- or β-globin chains followed by gold-labeled anti-mouse IgG, the density of gold particles over the majority of the inclusions was clearly greater than that over surrounding inclusion-free cytoplasm (Fig 3). By contrast, in sections from the two patients with β-thalassemia major, gold particles were concentrated over the inclusions following incubation with the antibody to α-globin chains, but not to β-globin chains (Fig 4A-C). The density of gold particles over inclusions in all control preparations was not greater than that over surrounding cytoplasm (Fig 4D).

Electron micrographs of erythroblastic inclusions from sections of marrow immunogold-labeled with mouse monoclonal antibody. Inclusions from case no. 1 show positive reactions with antibody against α-globin chains (A) and β-globin chains (B). Inclusions from case no. 2 show positive reactions with antibody against α-globin chains (C) and β-globin chains (D). Magnifications: A, × 32,000; B, × 38,000; C, × 32,000; D, × 37,000.

Electron micrographs of erythroblastic inclusions from sections of marrow immunogold-labeled with mouse monoclonal antibody. Inclusions from case no. 1 show positive reactions with antibody against α-globin chains (A) and β-globin chains (B). Inclusions from case no. 2 show positive reactions with antibody against α-globin chains (C) and β-globin chains (D). Magnifications: A, × 32,000; B, × 38,000; C, × 32,000; D, × 37,000.

Electron micrographs of erythroblastic inclusions from sections of marrow immunogold-labeled with mouse monoclonal antibody. Inclusions from a case of β-thalassemia major show a positive reaction with antibody against human α-globin chains (A, B) and no reaction with antibody against human β-globin chains (C). B shows part of the inclusion in A at higher magnification. There is virtually no labeling of inclusions in a control section that was reacted with normal mouse serum instead of a monoclonal antibody (D). Magnifications: A, × 20,000; B, × 59,000; C, × 23,000; D, × 35,000.

Electron micrographs of erythroblastic inclusions from sections of marrow immunogold-labeled with mouse monoclonal antibody. Inclusions from a case of β-thalassemia major show a positive reaction with antibody against human α-globin chains (A, B) and no reaction with antibody against human β-globin chains (C). B shows part of the inclusion in A at higher magnification. There is virtually no labeling of inclusions in a control section that was reacted with normal mouse serum instead of a monoclonal antibody (D). Magnifications: A, × 20,000; B, × 59,000; C, × 23,000; D, × 35,000.

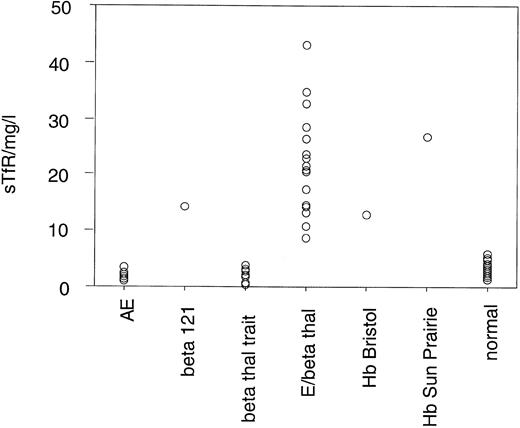

Serum TfR levels in normal subjects and patients with various conditions are presented in Table 2 and Fig 5. Patient no. 2 had a TfR level of 14.2 mg/L, which is significantly higher than that observed in normal subjects (mean, 2.82 ± 0.96 mg/L), β-thalassemia heterozygotes (mean, 2.19 ± 1.27 mg/L), or HbE heterozygotes (mean, 1.97 ± 0.59 mg/L). The level of increase is comparable to that observed in a heterozygote for Hb Bristol (12.9 mg/L), an unstable β-chain variant.

Serum TfR Levels in Normal Subjects and Patients With Various Anemias

| Sample . | No. . | Mean Serum TfR (mg/L) . | SD . | Range (mg/L) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Thalassemia trait | 11 | 2.19 | 1.27 | 0.43-3.98 |

| HbE Trait | 12 | 1.97 | 0.59 | 1.2-2.4 |

| HbE/β Thalassaemia | 20 | 20.6 | 8.73 | 8.7-43.0 |

| Hb Bristol heterozygote | 1 | 12.9 | ||

| Hb Sun Prairie homozygote | 1 | 26.9 | ||

| β121 | 1 | 14.2 | ||

| Normal | 44 | 2.82 | 0.96 | 1.34-5.92 |

| Sample . | No. . | Mean Serum TfR (mg/L) . | SD . | Range (mg/L) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Thalassemia trait | 11 | 2.19 | 1.27 | 0.43-3.98 |

| HbE Trait | 12 | 1.97 | 0.59 | 1.2-2.4 |

| HbE/β Thalassaemia | 20 | 20.6 | 8.73 | 8.7-43.0 |

| Hb Bristol heterozygote | 1 | 12.9 | ||

| Hb Sun Prairie homozygote | 1 | 26.9 | ||

| β121 | 1 | 14.2 | ||

| Normal | 44 | 2.82 | 0.96 | 1.34-5.92 |

Distribution of serum TfR levels in normal individuals, patient no. 1 (β121), and subjects with various anemias. The mean level in 44 normal subjects is 2.82 ± 0.96 mg/L.

Distribution of serum TfR levels in normal individuals, patient no. 1 (β121), and subjects with various anemias. The mean level in 44 normal subjects is 2.82 ± 0.96 mg/L.

DISCUSSION

It has been proposed that the mutations found in the dominantly inherited β thalassemias result in the synthesis of extremely unstable β-globin chain variants, demonstrated in some cases but implicated in others, the precipitation of which imposes an extra burden on the proteolytic reserves of red cell precursors and leads to a considerable degree of ineffective erythropoiesis.1 Various mutations affecting the β-globin gene have been reported in families with this type of β thalassemia, including β-codon 121 G-T and β-codon 127 C-T, both nonsense mutations in exon 3 that are predicted to produce truncated β-globin chains due to premature termination. The marked increase in soluble TfR level in the individual heterozygous for the β121 mutation (case no. 2) suggests a significant degree of erythron expansion, comparable to that seen in a severe hemolytic anemia, Hb Bristol, and in HbE/β thalassemia. Despite the increase in TfR level, the reticulocyte count is relatively low, which indicates that the majority of this expansion is due to ineffective erythropoiesis. Although substantial amounts of mutant β mRNA could be shown in patients with such mutations,10 as also shown in both cases here, it has been difficult to demonstrate the presence of the truncated β variant, suggesting that the variant chain may be extremely unstable.

That the truncated β121 chains are highly unstable and rapidly degraded is demonstrated by the imbalanced α:β biosynthesis ratios in both individuals heterozygous for the β121 G-T mutation. This is supported by the very small amount of truncated β121 chain present in both marrow and blood even when the β121 chain appears to be synthesized at approximately the same rate as the normal β chain, as evidenced by its high specific activity. In a previous study of another case of β121 G-T mutation, a small peak of radioactivity eluting before βA in a position similar to the present case could be demonstrated. Fractions from 10 high-performance liquid chromatography runs were pooled to isolate enough proteins for peptide analysis. The truncated β globin was estimated to comprise only 0.05% to 0.1% of the total non-α globin.9 While this may indicate instability of the protein, it may also be due to a lack of synthesis, and no formal assessment of its stability was made. In our study, we were able to examine erythroid precursors of the marrow, as well as reticulocytes. It is noteworthy that the α/β ratios are more balanced in the marrow than the blood. This is probably related to the greater proteolytic capacity in erythroblasts when compared with the reticulocytes; excess α chains, which result from the deficit of normal β chains, are removed more rapidly, resulting in a less imbalanced α/β ratio. The abnormal β variant that is truncated to residue 120 should bind heme with some secondary structure and, presumably, is not as unstable as mutants in which no abnormal globin has ever been demonstrated, such as Hb Manhattan (β-codon 109 [-G]),14 Hb Showa-Yakushiji (β-codon 110 Leu-Pro),15 Hb Durham NC (β114 Leu → Pro),16 or those in which the abnormal chain was only detected when newly synthesized following incubation with radioactive amino acids, eg, Hb Houston (β-codon 127 Gln → Pro).14

Another example of this class of β thalassemia is Hb Terre Haute (β106 Leu-Arg),6 initially reported as Hb Indianapolis (β112 Cys-Arg).4 In two patients heterozygous for this mutant β globin, biosynthetic studies showed an α:non-α ratio of approximately 1.0 in marrow erythroblasts compared with a ratio of approximately 2 in reticulocytes. Although the variant β chain was synthesized at a level almost equal to that of the normal β chain, most of it was rapidly precipitated on the red cell membrane. Heinz bodies isolated from the cells of these patients consisted of both α- and β-globin chains. Fingerprinting data on chromatographic fractions prepared from “pure” inclusion bodies derived from the red cells of patients with other β mutants of this class2,3 5 also showed that the prominent inclusion bodies contained both precipitated α- and β-globin chains. Based on these observations, it was hypothesized that both the hyperunstable β-globin chains and the redundant excess α-globin chains were responsible for the underlying pathology of the dominantly inherited β thalassemias. However, the reliability of these data was uncertain, as the inclusions were always contaminated with membrane proteins and probably small amounts of membrane-associated Hb, and the relative proportion of α and β chains found in the inclusions varied from one experiment to another.

Prominent intra-erythroblastic inclusions were also present in both of these individuals (patients no. 1 and 2) with dominantly inherited β thalassemia. The percentage of polychromatic erythroblast sections containing inclusions in the two cases was 30%, which is considerably above the range (0.2% to 2.8%) previously reported in β-thalassemia trait.13 We have investigated the composition of the inclusions in cases no. 1 and 2 by immunoelectron microscopy using mouse monoclonal antibodies against human α- and β-globin chains and the immunogold technique. The intra-erythroblastic inclusions in the two cases reacted with both monoclonal antibodies to α- and β-globin chains, clearly indicating that these inclusions contained both types of chains. In contrast, the intra-erythroblastic inclusions found in homozygous β thalassemia reacted with the monoclonal antibody against α globin but not β-globin chains, confirming that they consisted only of precipitated α-globin chains. These data support the hypothesis that the cellular pathology underlying the dominantly inherited β thalassemias is related to the synthesis of highly unstable β-globin chains, which are not able to form functional tetramers. These abnormal β-chain variants precipitate intracellularly together with the concomitant excess α-globin chains to form large inclusions, which leads to more severe ineffective erythropoiesis than in heterozygous β thalassemia, in which much smaller amounts of precipitated globin chains are found.17

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Liz Rose and Milly Graver for preparation of the manuscript, Prof Peter Beverley for permission to use the anti–β-globin chain antibody, Dr Bill Wood for the kind gift of anti–α-globin chain antibody, and Prof Sir D.J. Weatherall for encouragement and support.

Supported by the Medical Research Council, UK. P.J.H. is a Nuffield Dominions Fellow and D.C.R. is a Medical Research Council Training Fellow.

Address reprint requests to Swee Lay Thein, MD, MRC Molecular Haematology Unit, Institute of Molecular Medicine, John Radcliffe Hospital, Headington, Oxford OX3 9DU, UK.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal