Key Points

The inherited AnWj-negative blood group phenotype is caused by homozygosity for a deletion in MAL, encoding Mal protein.

Mal protein is expressed on red blood cell membranes of AnWj-positive, but not AnWj-negative, individuals.

Visual Abstract

The genetic background of the high prevalence red blood cell antigen AnWj has remained unresolved since its identification in 1972, despite reported associations with both CD44 and Smyd1 histone methyltransferase. Development of anti-AnWj, which may be clinically significant, is usually due to transient suppression of antigen expression, but a small number of individuals with persistent, autosomally recessive inherited AnWj-negative phenotype have been reported. Whole-exome sequencing of individuals with the rare inherited AnWj-negative phenotype revealed no shared mutations in CD44H or SMYD1; instead, we discovered homozygosity for the same large exonic deletion in MAL, which was confirmed in additional unrelated AnWj-negative individuals. MAL encodes an integral multipass membrane proteolipid, myelin and lymphocyte protein (Mal), which has been reported to have essential roles in cell transport and membrane stability. AnWj-positive individuals were shown to express full-length Mal on their red cell membranes, which was not present on the membranes of AnWj-negative individuals, regardless of whether from an inherited or suppression background. Furthermore, binding of anti-AnWj was able to inhibit binding of anti-Mal to AnWj-positive red cells, demonstrating the antibodies bind to the same molecule. Overexpression of Mal in an erythroid cell line resulted in the expression of AnWj antigen, regardless of the presence or absence of CD44, demonstrating that Mal is both necessary and sufficient for AnWj expression. Our data resolve the genetic background of the inherited AnWj-negative phenotype, forming the basis of a new blood group system, further reducing the number of remaining unsolved blood group antigens.

This is an episode of the Blood podcast; subscribe to the channel in your favorite podcast app.

This is an episode of the Blood podcast; subscribe to the channel in your favorite podcast app.

Introduction

Knowledge of the complexities of blood groups is crucial not only in transfusion and pregnancy but also in understanding disease susceptibility, population genetics, and evolutionary studies. The molecular bases of nearly all known blood group antigens have now been elucidated, with 45 blood group systems, comprising 362 antigens, currently recognized by the International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT). A small number of remaining antigens have yet to be genetically resolved; 16 of low prevalence (700 series) and only 3 of high prevalence (901 series).1

Among these, the AnWj or Anton (ISBT 901009) high prevalence antigen, previously also known as Wj,2 was first identified in 1972.3 AnWj is present on epithelial tissues and red cells of >99.9% of individuals but is absent on cord cells.2 Transition of red cells from AnWj-negative to AnWj-positive normally occurs between 3 and 46 days after birth and is completed within 24 to 48 hours,4 although the mechanism remains unknown. AnWj expression is also markedly reduced on In(Lu) phenotype cells,3-6 caused by mutation in the KLF1 gene encoding the erythroid transcription factor Krueppel-like factor 1 (KLF1/EKLF).7 In(Lu) cells show reduced expression of several blood group antigens in addition to AnWj, including those of the Lutheran and Indian (CD44) systems.8,9

Antibodies directed against AnWj are rare and usually associated with transient suppression of AnWj expression on an individual’s red cells, associated with various disorders, including lymphoid malignancies and autoimmune hemolytic anemia.10-13 In addition, an autosomal recessive inherited, persistent AnWj-negative phenotype was first reported in a consanguineous family of Middle Eastern origin.14 Alloanti-AnWj in the AnWj-negative propositus and her sibling was presumably produced as a result of pregnancy but was not associated with hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn (HDFN). However, anti-AnWj may be clinically significant and has been associated with acute hemolytic transfusion reactions.12,13,15

The AnWj antigen has been reported to be the erythrocyte receptor for Haemophilus influenzae,4 however, the carrier molecule for AnWj on the red cell surface has remained elusive. It has been reported that AnWj may be carried on CD44 or dependent on CD44 for its expression.16,17 More recently, a missense mutation in the SMYD1 gene, encoding a histone methyltransferase, has been reported to be the cause of the inherited AnWj-negative phenotype, but the mechanism for this has not been elucidated.18

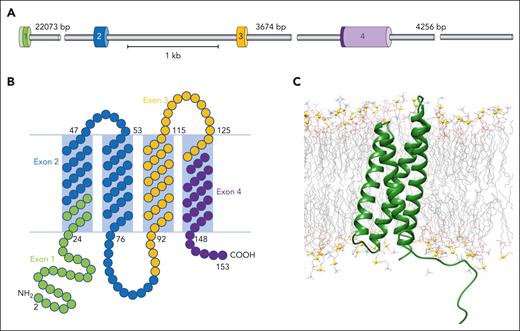

Myelin and lymphocyte protein (Mal) is an integral multipass membrane proteolipid of 17 kDa, which resides in glycosphingolipid and cholesterol–enriched microdomains. It appears to shuttle between the trans-Golgi network, plasma membrane, and endosomes.19 The MAL gene, located on chromosome 2, was first identified in human T lymphocytes20 and is organized into 4 exons, each encoding a membrane-associated segment and an adjacent hydrophilic sequence (Figure 1).21 Mal is also expressed in myelin-forming cells and in polarized epithelial cells,22-24 where it plays important roles in assembly and stabilization of glycosphingolipid and cholesterol–enriched microdomains and in protein targeting. Mal is required for apical sorting and transport of influenza virus hemagglutinin in polarized cells25 and has also been identified as the receptor for binding of Clostridium perfringens epsilon toxin on erythrocyte membranes.26

MAL gene and Mal protein organization. (A) Representation of MAL gene showing the 4 coding exons represented by different colored cylinders. (B) Schematic showing Mal protein organization in the membrane, with 2 predicted external loops. Amino acids are color-coded according to the exon that encodes them (exon 1, green; exon 2, blue; exon 3, orange; exon 4, purple). (C) All-atom explicit solvent molecular dynamics calculation of modeled Mal protein, depicting membrane insertion. Mal protein is depicted in green cartoon representation, whereas the lipid components are shown as wire representation colored by atom type. The solvent has been omitted for clarity. Phosphate atoms are represented as gold balls for orientation of the membrane leaflet.

MAL gene and Mal protein organization. (A) Representation of MAL gene showing the 4 coding exons represented by different colored cylinders. (B) Schematic showing Mal protein organization in the membrane, with 2 predicted external loops. Amino acids are color-coded according to the exon that encodes them (exon 1, green; exon 2, blue; exon 3, orange; exon 4, purple). (C) All-atom explicit solvent molecular dynamics calculation of modeled Mal protein, depicting membrane insertion. Mal protein is depicted in green cartoon representation, whereas the lipid components are shown as wire representation colored by atom type. The solvent has been omitted for clarity. Phosphate atoms are represented as gold balls for orientation of the membrane leaflet.

Mal has been reported to have conflicting roles in cancer, apparently acting both as an oncogene and a tumor suppressor.27 Esophageal cancer cell lines demonstrated a lack of Mal expression, caused by promoter methylation,28 and Mal downregulation has also been associated with a number of epithelial malignancies, including colon cancer,29,30 breast cancer,31 and bladder cancer.32 Contrastingly, overexpression of Mal appears to be associated with poor prognosis in several lymphocyte-derived cancers such as acute adult T-cell leukemia,33 primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma,34 and Hodgkin lymphoma,35 as well as in ovarian cancer.36,37 In addition to these opposing cancer associations, a rare, missense, mutation in MAL has been reported to cause leukodystrophy, with mutated Mal retained in the endoplasmic reticulum.38

In this study, we identify homozygous deletions in the MAL gene associated with the inherited AnWj-negative phenotype, finally elucidating the genetic basis of this long-established blood group antigen. We demonstrate a lack of red blood cell (RBC) Mal expression in AnWj-negative individuals, both transient and inherited, and show that overexpression of Mal in an erythroid cell line results in the expression of AnWj antigen, thereby establishing a new blood group system.

Methods

Participants

Blood samples were procured, and the study conducted according to the National Health Service (NHS) Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) Research and Development governance requirements and ethical standards, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval was granted by NHS Health Research Authority, Bristol Research Ethics Committee (reference 12/SW/0199). Samples from AnWj-negative individuals (n = 7; P1-P7) and family members (n = 4; P2_F1-P2_F4) were obtained from cryopreserved rare reference material International Blood Group Reference Laboratory (IBGRL) collections. Fresh blood samples were obtained from a further AnWj-negative individual and her sibling (P8 and P8_F1) with informed consent. Samples from In(Lu) phenotype individuals (n = 3) were obtained from cryopreserved IBGRL reference collections. Samples are detailed in supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website.

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid peripheral blood samples from voluntary NHSBT donors, consented to the use of their blood for research purposes, were used as AnWj-positive controls.

Serological testing

Standard agglutination techniques were used for the assessment of anti-AnWj reactivity and RBC phenotyping.39 For the indirect antiglobulin test, a low-ionic strength saline tube method was used, in which the secondary antibody was anti-human globulin (Millipore), polyspecific for human primary antibodies (in-house IBGRL reference collection), or polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Dako) for mouse primary monoclonal antibodies (IBGRL Research Products). Anti-AnWj eluates were prepared using Gamma ELU-KIT II rapid acid elution kit (Immucor). Direct antiglobulin test (DAT) was carried out using DC-Screening I cards (Bio-Rad) and low-ionic strength saline tube method using anti-human globulin. For papain treatment, 1 volume of washed packed RBCs was incubated with 2 volumes of papain (NHSBT) for 3 minutes. After incubations, RBCs were washed a minimum of 4 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) until supernatant was clear.

For agglutination tests using anti-Mal, 15 μL of a 2% solution of RBCs in PBS 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) was incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature (RT) with either anti-Glycophorin A (GPA [BRIC256 and BRIC163; IBGRL Research Products]), polyclonal mouse anti-Mal (ab167374; Abcam), or monoclonal anti-AnWj (H86).40 Cells were washed twice with PBS 1% BSA before incubation with secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse; Jackson) and viewing under a light microscope at ×100 magnification.

For blocking, 15 μL of a 2% solution of RBCs in PBS 1% BSA was incubated at RT for 60 minutes with plasma containing human anti-AnWj or a 1:1 mix of plasma containing human anti-Lua and human anti-Lub. After 2 washes in PBS 1% BSA, cells were incubated for 20 minutes at RT with either anti-GPA, anti-Mal, or anti-AnWj. After incubation, cells were washed twice with PBS 1% BSA before a 1 in 100 dilution of goat anti-mouse was added, and the plate was immediately spun before reading.

Next-generation sequencing library preparation

Genomic DNA was extracted using a commercial isolation kit (QIAamp DNA blood mini kit; Qiagen). Library preparation, indexing, and target enrichment for exome or targeted blood group panel sequencing were carried out using Nextera Rapid Capture Exome or DNA prep with enrichment (Illumina). The exome kit targets 45 Mb of coding sequence, whereas the custom panel targets 0.5-Mb coding sequence of known blood group genes (recognized by ISBT as of 2022), plus several other genes of interest including MAL. Paired-end (2 × 87 cycle) single-plex sequencing was carried out on a MiSeq (Illumina). Secondary data analysis, including alignment of reads against human reference genome hg19, was performed using MiSeq Reporter v2.5.1 (Illumina), and the variants were called and annotated using Illumina Variant Studio v2.2. Selected alignments were further visualized using Integrative Genomics Viewer (v2.3).41

Genetic analysis of SMYD1 and CD44H

SMYD1 exon 7 and CD44H exons present in erythroid isoform (1-5 and 15-17) were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR; primers and conditions shown in supplemental Table 2). PCR products were prepared for sequencing using ExoSAP-IT (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Sanger sequenced with forward and reverse PCR primers using a capillary automated DNA sequencer (3130xL Genetic Analyzer; Applied Biosystems). Sequences were aligned to Homo sapiens SMYD1 (NM_001330364.2) or CD44 (NG_008937.1) reference sequence using SeqScape (Applied Biosystems).

Sequencing and deletion analysis of MAL

Confirmation of deletions involving MAL exons 3 and 4 was carried out by PCR amplification of individual coding exons (1-4) and of products spanning deleted regions (supplemental Table 2). PCR products were prepared for sequencing with ExoSAP-IT (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and sequenced with forward and reverse PCR primers or internal sequencing primers as shown in supplemental Table 2.

Flow cytometry

Erythrocytes (0.25-μL packed cells per test) and BEL-A cells (3 × 105 cells per test) were analyzed by flow cytometry after labeling with anti-Mal (ab167374), anti-AnWj (H86), human anti-AnWj eluate, anti-CD44 (BRIC222; IBGRL Research Products), and anti-Lutheran (BRIC221 and BRIC224; IBGRL Research Products). Isotype controls (Bio-Rad) were tested in parallel to ascertain background fluorescence. Cells were incubated with primary antibody at RT for 30 minutes and washed once. Bound antibody was detected by adding R-phycoerythrin anti-mouse globulins (Dako) or Alexa Fluor 647-AffiniPure F(ab')2 fragment goat anti-human immunoglobulin G (Stratech Scientific) and incubated at 4°C for 30 minutes. Cells were washed once, and fluorescence geometric mean was recorded for each test. Flow cytometry was performed on a Navios (Beckman Coulter).

RBC membrane preparation and immunoblotting

RBC membranes were prepared as previously described,42 and protein content was determined using a commercial assay kit (Pierce BCA; Pierce Biotechnology). Membranes (50 μg) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on a 4% to 20% gradient precast gel (Bio-Rad) under reducing conditions, transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Thermo Fisher Scientific), blocked overnight in 5% milk, and immunoblotted using mouse monoclonal anti-Mal antibodies E1:sc-390687 (Santa Cruz) or 6D9.43

Generation of CRISPR/CRISPR-associated protein 9 DNA constructs and MAL editing of BEL-A cells

Knockout (KO) of MAL in BEL-A cells was achieved by nucleofection of ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) using an Amaxa 4D nucleofector (Lonza), program DZ100. RNPs were prepared by addition of 22.5 pmol of each of 2 chemically modified single guide RNAs (Synthego) targeting MAL to 18 pmol CRISPR-associated protein 9 and incubating at 25°C for 15 minutes. Guide sequences were as follows (MAL exon 1: ATGGCCCCCGCAGCGGCGAC and exon 2: TCCTCCCCCGCAGATCTTCG). Transfected cells were fluorescence-activated cell sorted to obtain single clones, and the presence of biallelic disruptive mutations was assessed by Sanger sequencing. Knockout CD44 BEL-A cell line has been previously described.44

Overexpression of Mal in BEL-A cells

Preparation of lentiviral particles and transduction of BEL-A cells was performed as previously described45 using XLG3 vector for expression of MAL constructs. Open reading frames of full-length and truncated (exons 1 and 2 only) MAL were synthesized, with and without N-terminal green fluorescent protein (GFP) tag, and cloned into XLG3 by GenScript.

Confocal microscopy of GFP-expressing BEL-A cell lines

BEL-A cells (8 × 104) were centrifuged at 400g for 5 minutes, and pellets were resuspended in 200 μL of BEL-A expansion medium. Cell suspensions were placed into an uncoated 8-well chamber slide (ibidi) and incubated at RT for 10 minutes. Samples were imaged at 22°C using 40× oil immersion lenses on a TCS SP8 confocal imaging system (Leica). Images were obtained using Leica LAS AF software.

Results

Serological identification of AnWj-negative individuals

Individuals with AnWj-negative phenotype were originally identified through clinical investigations of unresolved antibodies to a high prevalence antigen. The antibody in each case was identified as anti-AnWj, and the AnWj-negative phenotype was determined by lack of reactivity with at least 2 examples of anti-AnWj. Reactivity with autologous control cells and DAT status were scrutinized to predict whether AnWj-negative phenotype was due to inheritance or transient suppression of antigen expression. Suppression was suspected if a positive DAT was observed, and comparable weak reactivity was seen with the RBCs when typed with anti-AnWj. Weak reactivity detected with monoclonal anti-AnWj under papain enhancement conditions or the ability to adsorb and elute anti-AnWj from the cells also supported suppression. Conversely, inheritance was inferred from family information when available, a negative DAT, and/or inability to adsorb/elute anti-AnWj from RBCs, demonstrating complete lack of the antigen. Additional AnWj-negative individuals were identified through family studies (supplemental Table 1).

Determination of genetic basis of inherited AnWj-negative phenotype

To uncover the genetic basis of the AnWj antigen, DNA from 2 unrelated individuals, with persistent, inherited AnWj-negative phenotype (P1 and P2) was subjected to whole-exome sequencing. The CD44 and SMYD1 genes, previously reported to be associated with AnWj expression, were analyzed in both individuals. No mutations were identified in CD44H (encoding the erythroid CD44 isoform) in either individual. The SMYD1 variant 959G>A (NM_001330364.2, R320Q, rs114851602) was homozygous in P2, but P1 was wild-type at this position, suggesting an alternative cause for the AnWj-negative phenotype. Thus, whole-exome sequences were analyzed, filtering for genes carrying rare (frequency <0.01), homozygous missense or nonsense mutations, consistent with the lack of the high prevalence AnWj antigen.

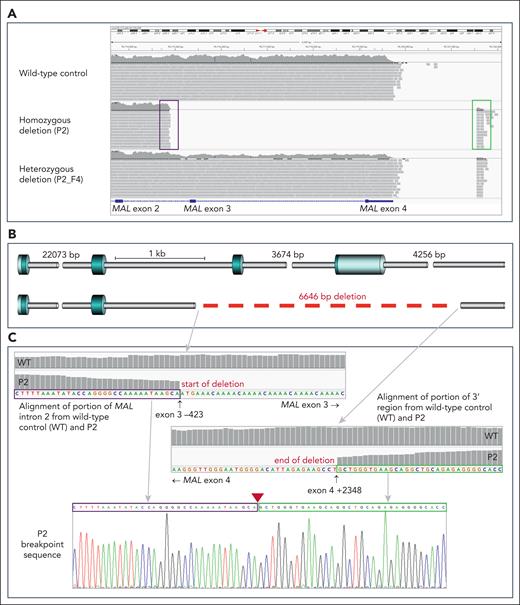

No variant fitting these criteria was shared by both individuals, so data were further analyzed to search for possible deletions shared by P1 and P2 but not present in control sequences. A homozygous deletion of exons 3 and 4 of MAL gene, encoding Mal protein, was observed in both P1 and P2 but was not present in AnWj-positive controls (n = 5). To determine whether this deletion was responsible for the lack of AnWj, further samples with serologically determined AnWj-negative phenotypes were subjected to targeted next-generation sequencing and/or Sanger sequencing. AnWj-negative family members of P2 (P2_F1 and P2_F2), 2 siblings from the same region (apparently unrelated to the original family; P8 and P8_F1), and a further 2 unrelated AnWj-negative individuals (P3 and P4) were all shown to be homozygous for the same 6646 nt deletion in MAL, encompassing coding exons 3 and 4 (NC_00002.12, NM_002371.4; 262-423_462+2348del) as shown in Figure 2. AnWj-positive family members of P2 (P2_F3 and P2_F4) were either homozygous wild-type or heterozygous for the MAL deletion allele. Three serologically AnWj-negative individuals (P5-P7) had wild-type MAL, all of which have evidence suggesting the negative phenotype is due to suppression of AnWj expression (such as positive DAT and/or clinical condition; supplemental Table 1). No coding mutations in CD44H were identified in any AnWj-negative individuals, except P6 who carried a heterozygous rare coding mutation in CD44 exon 17; 2018G>A, Arg673Gln (rs61752932). Only P2 and family members, plus the unrelated AnWj-negative siblings from the same region, were homozygous for SMYD1 variant 959G>A, with all other AnWj-negative individuals showing wild-type sequence at this position. Sequencing results are detailed in Table 1.

All individuals with inherited AnWj-negative phenotype are homozygous for the same deletion in MAL, encompassing exons 3 and 4. (A) Portion of chromosome 2 sequence, spanning MAL exons 2 to 4, from next-generation sequencing (NGS) targeted–panel sequencing of 3 representative individuals. Wild-type sequence is shown in the upper panel, whereas individual P2 (middle) shows no sequencing reads mapping to exons 3 and 4, with reads spanning the deleted area mapping to intron 2 (boxed in purple) and in the region downstream from exon 4 (boxed in green). The bottom panel shows a deletion heterozygote (P2_F4), with only ∼50% of expected reads mapping to MAL exons 3 and 4, and the end of sequencing reads spanning the deleted area is clearly visible, mapping in the same region as with the homozygous deletion sample above. (B) Gene schematic showing deletion break points. Wild-type MAL (top) consists of 4 coding exons (blue cylinders), whereas the AnWj-negative individuals lack exons 3 and 4 and parts of the adjacent introns (gray cylinders). Deletion (6646 bp) represented by dashed red line. (C) Details of portions of MAL intron 2 (upper left) and 3' region downstream from MAL (lower right) sequence alignment in representative AnWj-negative individual (P2) compared with wild-type control. Sanger sequencing of P2 across the deletion break points is shown in bottom panel; sequence boxed in purple derives from intron 2, whereas sequence boxed in green derives from the 3' region downstream from exon 4. Position of deletion is indicated by red triangle. Break points confirmed by Sanger and/or NGS sequencing to be identical in all AnWj-negative samples (Table 1).

All individuals with inherited AnWj-negative phenotype are homozygous for the same deletion in MAL, encompassing exons 3 and 4. (A) Portion of chromosome 2 sequence, spanning MAL exons 2 to 4, from next-generation sequencing (NGS) targeted–panel sequencing of 3 representative individuals. Wild-type sequence is shown in the upper panel, whereas individual P2 (middle) shows no sequencing reads mapping to exons 3 and 4, with reads spanning the deleted area mapping to intron 2 (boxed in purple) and in the region downstream from exon 4 (boxed in green). The bottom panel shows a deletion heterozygote (P2_F4), with only ∼50% of expected reads mapping to MAL exons 3 and 4, and the end of sequencing reads spanning the deleted area is clearly visible, mapping in the same region as with the homozygous deletion sample above. (B) Gene schematic showing deletion break points. Wild-type MAL (top) consists of 4 coding exons (blue cylinders), whereas the AnWj-negative individuals lack exons 3 and 4 and parts of the adjacent introns (gray cylinders). Deletion (6646 bp) represented by dashed red line. (C) Details of portions of MAL intron 2 (upper left) and 3' region downstream from MAL (lower right) sequence alignment in representative AnWj-negative individual (P2) compared with wild-type control. Sanger sequencing of P2 across the deletion break points is shown in bottom panel; sequence boxed in purple derives from intron 2, whereas sequence boxed in green derives from the 3' region downstream from exon 4. Position of deletion is indicated by red triangle. Break points confirmed by Sanger and/or NGS sequencing to be identical in all AnWj-negative samples (Table 1).

Sequencing results for AnWj-negative individuals and family members

| Sample . | Phenotype . | Genetic investigations . | CD44H (exons 1-5, 15-18) NM_00610.4 . | SMYD1 NM_001330364.2 . | MAL NC_0002.12, NM_002371.4 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | AnWj-negative (inherited) | WES, Sanger SMYD1 & MAL, breakpoint analysis | No mutations | No mutation | Homozygous MAL 6646 nt deletion encompassing exons 3 and 4; (NC_00002.12, NM_002371.4; 262-423_462+2348del) |

| P2 | AnWj-negative (inherited) | WES, Sanger SMYD1 & MAL | No mutations | Homozygous 959G>A, R320Q (rs114851602; gnomAD v4.0.0 freq 0.0006) | Homozygous MAL 6646 nt deletion as in P1 |

| P2_F1 | AnWj-negative (inherited) | Targeted NGS, Sanger SMYD1 & MAL, breakpoint analysis | No mutations | Homozygous 959G>A, R320Q | Homozygous MAL 6646 nt deletion as in P1 |

| P2_F2 | AnWj-negative (inherited) | Targeted NGS, Sanger SMYD1 | No mutations | Homozygous 959G>A, R320Q | Homozygous MAL 6646 nt deletion as in P1 |

| P2_F3 | AnWj-positive | Targeted NGS, Sanger SMYD1 | No mutations | No mutation | Wild-type MAL, no deletion |

| P2_F4 | AnWj-positive | Targeted NGS, Sanger SMYD1 | No mutations | Heterozygous 959G>A, R320Q | Heterozygous MAL 6646 nt deletion |

| P3 | AnWj-negative (inherited) | Targeted NGS, Sanger SMYD1 & MAL, breakpoint analysis | Homozygous synonymous mutation in exon 3; 255C>T, H85H (rs1071695; gnomAD v4.0.0 freq. 0.16) | No mutation | Homozygous MAL 6646 nt deletion as in P1 |

| P4 | AnWj-negative (inherited) | Sanger SMYD1 & MAL, breakpoint analysis | not tested | No mutation | Homozygous MAL 6646 nt deletion as in P1 |

| P5 | AnWj-negative (suppression) | Targeted NGS, Sanger SMYD1 & MAL | No mutations | No mutation | Wild-type MAL, no deletion |

| P6 | AnWj-negative (suppression) | Targeted NGS, Sanger SMYD1 & MAL | Heterozygous mutation in exon 17 2018G>A; R673Q (rs61752932; gnomAD v4.0.0 freq. 0.003) | No mutation | Wild-type MAL, no deletion |

| P7 | AnWj-negative (suppression) | Sanger SMYD1 & MAL | not tested | No mutation | Wild-type MAL, no deletion |

| P8 | AnWj-negative (inherited) | Targeted NGS, Sanger SMYD1 | No mutations | Homozygous 959G>A, R320Q | Homozygous MAL 6646 nt deletion as in P1 |

| P8_F1 | AnWj-negative (inherited) | Targeted NGS, Sanger SMYD1 | No mutations | Homozygous 959G>A, R320Q | Homozygous MAL 6646 nt deletion as in P1 |

| Sample . | Phenotype . | Genetic investigations . | CD44H (exons 1-5, 15-18) NM_00610.4 . | SMYD1 NM_001330364.2 . | MAL NC_0002.12, NM_002371.4 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | AnWj-negative (inherited) | WES, Sanger SMYD1 & MAL, breakpoint analysis | No mutations | No mutation | Homozygous MAL 6646 nt deletion encompassing exons 3 and 4; (NC_00002.12, NM_002371.4; 262-423_462+2348del) |

| P2 | AnWj-negative (inherited) | WES, Sanger SMYD1 & MAL | No mutations | Homozygous 959G>A, R320Q (rs114851602; gnomAD v4.0.0 freq 0.0006) | Homozygous MAL 6646 nt deletion as in P1 |

| P2_F1 | AnWj-negative (inherited) | Targeted NGS, Sanger SMYD1 & MAL, breakpoint analysis | No mutations | Homozygous 959G>A, R320Q | Homozygous MAL 6646 nt deletion as in P1 |

| P2_F2 | AnWj-negative (inherited) | Targeted NGS, Sanger SMYD1 | No mutations | Homozygous 959G>A, R320Q | Homozygous MAL 6646 nt deletion as in P1 |

| P2_F3 | AnWj-positive | Targeted NGS, Sanger SMYD1 | No mutations | No mutation | Wild-type MAL, no deletion |

| P2_F4 | AnWj-positive | Targeted NGS, Sanger SMYD1 | No mutations | Heterozygous 959G>A, R320Q | Heterozygous MAL 6646 nt deletion |

| P3 | AnWj-negative (inherited) | Targeted NGS, Sanger SMYD1 & MAL, breakpoint analysis | Homozygous synonymous mutation in exon 3; 255C>T, H85H (rs1071695; gnomAD v4.0.0 freq. 0.16) | No mutation | Homozygous MAL 6646 nt deletion as in P1 |

| P4 | AnWj-negative (inherited) | Sanger SMYD1 & MAL, breakpoint analysis | not tested | No mutation | Homozygous MAL 6646 nt deletion as in P1 |

| P5 | AnWj-negative (suppression) | Targeted NGS, Sanger SMYD1 & MAL | No mutations | No mutation | Wild-type MAL, no deletion |

| P6 | AnWj-negative (suppression) | Targeted NGS, Sanger SMYD1 & MAL | Heterozygous mutation in exon 17 2018G>A; R673Q (rs61752932; gnomAD v4.0.0 freq. 0.003) | No mutation | Wild-type MAL, no deletion |

| P7 | AnWj-negative (suppression) | Sanger SMYD1 & MAL | not tested | No mutation | Wild-type MAL, no deletion |

| P8 | AnWj-negative (inherited) | Targeted NGS, Sanger SMYD1 | No mutations | Homozygous 959G>A, R320Q | Homozygous MAL 6646 nt deletion as in P1 |

| P8_F1 | AnWj-negative (inherited) | Targeted NGS, Sanger SMYD1 | No mutations | Homozygous 959G>A, R320Q | Homozygous MAL 6646 nt deletion as in P1 |

Freq, frequency; gnomAD, Genome Aggregation Database; NGS, next-generation sequencing; WES, whole-exome sequencing.

Mal expression in AnWj-positive and AnWj-negative red cells

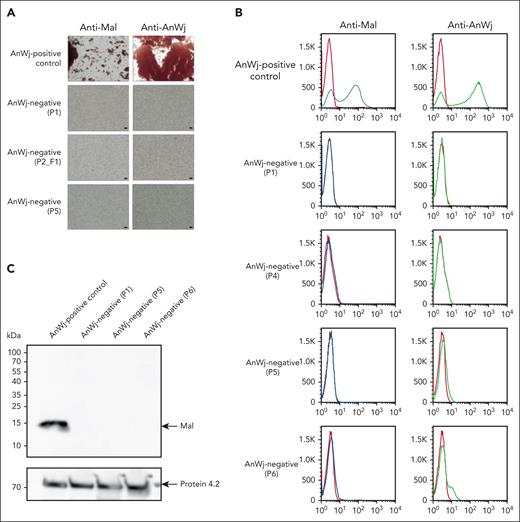

Previous studies26,46,47 suggest that Mal is expressed in low levels on human red cell membranes. To confirm this, AnWj-positive red cells were tested with polyclonal mouse anti-Mal, both serologically and by flow cytometry. Anti-Mal was able to bind and agglutinate AnWj-positive red cells, confirming its expression on normal erythrocyte membranes. Anti-Mal did not, however, bind to AnWj-negative red cells, even those with wild-type MAL (Figure 3A-B). Interestingly, flow cytometry of AnWj-positive control erythrocytes shows a bimodal expression pattern with both anti-Mal and anti-AnWj (Figure 3B), indicative of dual populations of antigen-positive and -negative cells. A band consistent in size with full-length Mal was observed by western blotting of red cell membranes from AnWj-positive individuals, which was not present with AnWj-negative membranes, regardless of the presence or absence of the MAL deletion (Figure 3C; supplemental Figure 1).

Anti-Mal binds AnWj-positive red cells, but not AnWj-negative cells. (A) Red cells sequentially incubated with either mouse polyclonal anti-Mal (ab167376, Abcam; 1 in 10) or mouse monoclonal anti-AnWj (H86; 1 in 5) followed by goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G show agglutination in AnWj-positive red cells (top row) but not in AnWj-negative red cells (lower 3 rows). Two representative examples of inherited AnWj-negative phenotype (P1 and P2_F1), both carrying homozygous MAL deletions, and 1 example of suspected AnWj antigen suppression, without MAL mutation (P5) cells, are shown. Negative (secondary antibody only) and positive (anti-GPA; BRIC256) controls were included (data not shown). Scale bars are 40 μm. Cells were imaged using a Leica DM750 microscope (Leica Microsystems) at 100× magnification and imaged using a Pixera Penguin 600CL camera (Digital Imaging Systems). (B) Flow cytometry with anti-Mal (ab167376) and anti-AnWj (H86) on control RBC (top row) and 4 representative examples of AnWj-negative cells, 2 with MAL deletion (P1 and P4), and 2 lacking the MAL deletion (P5 and P6). No detectable expression of Mal or AnWj is observed in any AnWj-negative samples. (C) Red cell membranes prepared from 1 AnWj-positive control and 3 AnWj-negative samples (P1, inherited; P5 and P6, suppression) were immunoblotted using mouse monoclonal anti-Mal antibody E1 (sc-390687; Santa Cruz). A band consistent with full-size Mal (15 kDa) was present in the control sample and absent in all AnWj-negative samples tested. The anti-protein 4.2 (BRIC273) control demonstrates consistent protein loading. A further 2 AnWj-negative samples showed the same results (supplemental Figure 1A). Multiple commercially available anti-Mal antibodies were tested (supplemental Table 3) but only 1 worked in our hands by red cell serology/flow cytometry (ab167376) and 2, E1 (shown here and supplemental Figure 1A) and 6D947 (supplemental Figure 1A-B), by immunoblotting.

Anti-Mal binds AnWj-positive red cells, but not AnWj-negative cells. (A) Red cells sequentially incubated with either mouse polyclonal anti-Mal (ab167376, Abcam; 1 in 10) or mouse monoclonal anti-AnWj (H86; 1 in 5) followed by goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G show agglutination in AnWj-positive red cells (top row) but not in AnWj-negative red cells (lower 3 rows). Two representative examples of inherited AnWj-negative phenotype (P1 and P2_F1), both carrying homozygous MAL deletions, and 1 example of suspected AnWj antigen suppression, without MAL mutation (P5) cells, are shown. Negative (secondary antibody only) and positive (anti-GPA; BRIC256) controls were included (data not shown). Scale bars are 40 μm. Cells were imaged using a Leica DM750 microscope (Leica Microsystems) at 100× magnification and imaged using a Pixera Penguin 600CL camera (Digital Imaging Systems). (B) Flow cytometry with anti-Mal (ab167376) and anti-AnWj (H86) on control RBC (top row) and 4 representative examples of AnWj-negative cells, 2 with MAL deletion (P1 and P4), and 2 lacking the MAL deletion (P5 and P6). No detectable expression of Mal or AnWj is observed in any AnWj-negative samples. (C) Red cell membranes prepared from 1 AnWj-positive control and 3 AnWj-negative samples (P1, inherited; P5 and P6, suppression) were immunoblotted using mouse monoclonal anti-Mal antibody E1 (sc-390687; Santa Cruz). A band consistent with full-size Mal (15 kDa) was present in the control sample and absent in all AnWj-negative samples tested. The anti-protein 4.2 (BRIC273) control demonstrates consistent protein loading. A further 2 AnWj-negative samples showed the same results (supplemental Figure 1A). Multiple commercially available anti-Mal antibodies were tested (supplemental Table 3) but only 1 worked in our hands by red cell serology/flow cytometry (ab167376) and 2, E1 (shown here and supplemental Figure 1A) and 6D947 (supplemental Figure 1A-B), by immunoblotting.

Furthermore, it was shown that binding of anti-Mal to AnWj-positive red cells was inhibited by the binding of human anti-AnWj, consistent with both antibodies binding to the same molecule (supplemental Figure 2). Together, these results demonstrate that Mal protein is required for the expression of AnWj antigen on erythrocytes.

Mal expression in BEL-A erythroid cell line

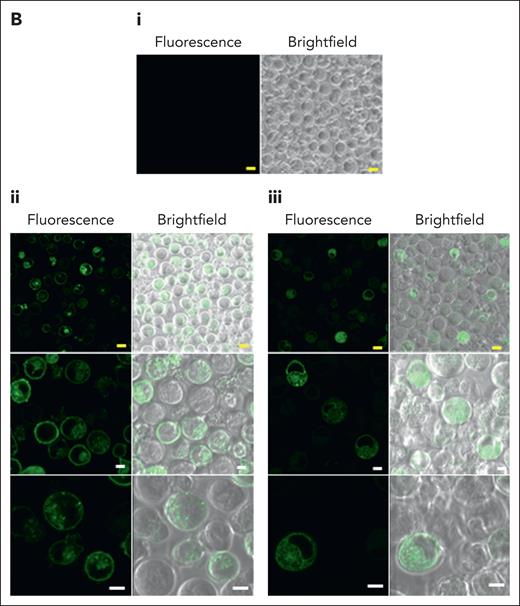

Although transcriptomics data (not shown) suggest a low level of Mal expression in the erythroid cell line BEL-A, no expression of either Mal or AnWj was detectable on unmodified BEL-A cells (Figure 4A). However, to ensure that no endogenous Mal expression was possible in these cells, a BEL-A erythroid MAL KO cell line was established by CRISPR-mediated gene editing. Sequencing of a selected BEL-A clone confirmed presence of a biallelic disruptive MAL mutation; Ile32AlafsTer21, confirming the clone to be genetically MAL KO. As expected, no expression of Mal or AnWj was detectable on BEL-A MAL KO cells (Figure 4A). To determine the specificity of anti-AnWj antibodies for Mal protein, a stable Mal overexpression BEL-A cell line was established. Both Mal and AnWj expression were detectable by flow cytometry in these cells (Figure 4A), confirming that Mal is required for AnWj expression. However, overexpression of the truncated form of MAL observed in AnWj-negative patients (exons 1 and 2 only) did not result in detectable surface expression of either Mal or AnWj (Figure 4A). Confocal imaging of GFP-tagged Mal showed that most full-length Mal was located on the plasma membrane of the BEL-A cells, whereas truncated Mal was restricted to the cytoplasm (Figure 4B), consistent with the lack of surface expression detected by flow cytometry.

Overexpression of full-length, but not truncated, Mal protein in BEL-A cells results in the expression of AnWj antigen at the cell surface. (A) Flow cytometry with mouse polyclonal anti-Mal (ab167374), human anti-AnWj eluate and monoclonal anti-AnWj (H86) wild-type BEL-A cells (top row), Mal KO BEL-A cells (second row), and BEL-A cells overexpressing either full-length Mal or truncated Mal (exons 1 and 2 only). Only BEL-A cells overexpressing full-length Mal (row 3) show any expression of Mal protein and AnWj antigen detectable by flow cytometry. (B) Full-length Mal (i), N-terminal GFP–tagged full-length Mal (ii), or GFP truncated Mal (iii; exons 1 and 2 only, as potentially expressed in the AnWj-negative patients) were expressed in KO Mal BEL-A cells and observed by confocal microscopy. Full-length Mal (ii) was located throughout the cell (but not in the nucleus) but was predominantly observed on the cell surface, whereas truncated Mal (iii) is localized inside the cell (but again not in the nucleus). Yellow scale bars are 10 μm, and white scale bars are 5 μm. Samples were imaged at 22 °C using 40× oil immersion lenses (magnification, 101.97 μm at zoom 3.8; 1.25 NA) on a TCS SP8 confocal imaging system (Leica). Images were obtained using Leica LAS AF software. KO, knockout; OE, overexpression.

Overexpression of full-length, but not truncated, Mal protein in BEL-A cells results in the expression of AnWj antigen at the cell surface. (A) Flow cytometry with mouse polyclonal anti-Mal (ab167374), human anti-AnWj eluate and monoclonal anti-AnWj (H86) wild-type BEL-A cells (top row), Mal KO BEL-A cells (second row), and BEL-A cells overexpressing either full-length Mal or truncated Mal (exons 1 and 2 only). Only BEL-A cells overexpressing full-length Mal (row 3) show any expression of Mal protein and AnWj antigen detectable by flow cytometry. (B) Full-length Mal (i), N-terminal GFP–tagged full-length Mal (ii), or GFP truncated Mal (iii; exons 1 and 2 only, as potentially expressed in the AnWj-negative patients) were expressed in KO Mal BEL-A cells and observed by confocal microscopy. Full-length Mal (ii) was located throughout the cell (but not in the nucleus) but was predominantly observed on the cell surface, whereas truncated Mal (iii) is localized inside the cell (but again not in the nucleus). Yellow scale bars are 10 μm, and white scale bars are 5 μm. Samples were imaged at 22 °C using 40× oil immersion lenses (magnification, 101.97 μm at zoom 3.8; 1.25 NA) on a TCS SP8 confocal imaging system (Leica). Images were obtained using Leica LAS AF software. KO, knockout; OE, overexpression.

Investigation of CD44 association with AnWj expression

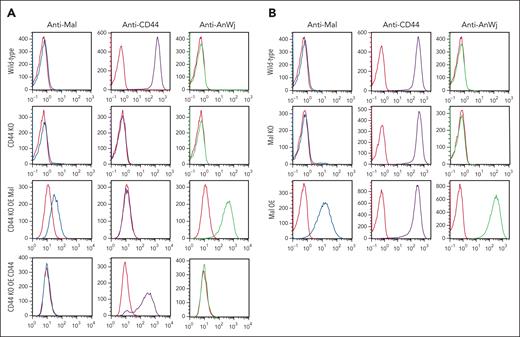

Because previous studies16,17 have suggested that CD44 is required for the expression of AnWj antigen, expression of Mal and AnWj were investigated in CD44 KO BEL-A cells. These cells showed no detectable levels of AnWj or Mal expression (as observed in unmodified BEL-A cells), but overexpression of Mal in CD44 KO cells resulted in expression of both Mal and AnWj, whereas overexpression of CD44 alone had no effect (Figure 5A). These data demonstrate that CD44 is neither sufficient nor required for the expression of AnWj antigen, whereas the expression of Mal alone results in AnWj expression, even in the absence of CD44.

CD44 is neither sufficient nor required for the expression of AnWj antigen, and CD44 expression is not affected by lack of Mal protein. (A) Flow cytometry with anti-Mal (ab167374), anti-CD44 (BRIC222), and anti-AnWj (H86) on wild-type BEL-A cells (top row), CD44 KO BEL-A cells (second row), and CD44 KO BEL-A cells overexpressing either Mal or CD44. Wild-type BEL-A cells express CD44, which is abolished in the CD44 KO BEL-A cells. Overexpression of Mal in CD44 KO BEL-A cells results in detectable expression of Mal and AnWj antigen, which is not observed in either wild-type, CD44 KO, or CD44 KO BEL-A cells rescued by overexpression of CD44. (B) Flow cytometry with anti-Mal (ab167374), anti-CD44 (BRIC222), and anti-AnWj (H86) on wild-type BEL-A cells (top row), Mal KO BEL-A cells (second row), and BEL-A cells overexpressing Mal (row 3). CD44 expression is not altered by either KO or OE of Mal protein. OE, overexpression.

CD44 is neither sufficient nor required for the expression of AnWj antigen, and CD44 expression is not affected by lack of Mal protein. (A) Flow cytometry with anti-Mal (ab167374), anti-CD44 (BRIC222), and anti-AnWj (H86) on wild-type BEL-A cells (top row), CD44 KO BEL-A cells (second row), and CD44 KO BEL-A cells overexpressing either Mal or CD44. Wild-type BEL-A cells express CD44, which is abolished in the CD44 KO BEL-A cells. Overexpression of Mal in CD44 KO BEL-A cells results in detectable expression of Mal and AnWj antigen, which is not observed in either wild-type, CD44 KO, or CD44 KO BEL-A cells rescued by overexpression of CD44. (B) Flow cytometry with anti-Mal (ab167374), anti-CD44 (BRIC222), and anti-AnWj (H86) on wild-type BEL-A cells (top row), Mal KO BEL-A cells (second row), and BEL-A cells overexpressing Mal (row 3). CD44 expression is not altered by either KO or OE of Mal protein. OE, overexpression.

Furthermore, normal expression of CD44 is observed on AnWj-negative cells14 (supplemental Figure 3) and on Mal KO cells (Figure 5B), showing that CD44 expression does not require the presence of Mal/AnWj antigen. In(Lu) cells, with mutations in erythroid-specific transcription factor KLF1, show reduced expression of several red cell antigens, including CD44.7-9 AnWj and Mal expression are extremely weak or absent on these cells, even in the presence of (albeit reduced) CD44 expression (supplemental Figure 3). These data suggest that, rather than the lack of AnWj antigen arising as an indirect result of reduced CD44 expression, the Mal protein may be a direct target for KLF1 transcriptional regulation. Analysis of the MAL proximal promoter region using JASPAR48 shows a KLF1 consensus binding site sequence (GGGGCGGGG) starting at position −179 relative to the start of the coding sequence.

Discussion

Despite reported associations with CD4416,17 and SMYD1,18 the genetic basis of the AnWj antigen has remained unresolved for >50 years. Here, we demonstrate that the AnWj-negative phenotype is associated with the loss of expression of Mal proteolipid on erythrocytes, and individuals with inherited AnWj-negative phenotype are homozygous for the same large deletion in the MAL gene. We also show that overexpression of Mal in an erythroid cell line results in expression of AnWj antigen, independently of CD44 expression.

The AnWj-negative phenotype is usually caused by transient suppression of antigen expression, associated with certain hematologic disorders and malignancies.10-13 Such suppression of blood group antigens, with associated antibody production against the suppressed antigen, is an established phenomenon, seen for example in Kell,49 Kidd,50 and Landsteiner-Wiener51,52 systems. In such cases, it has been hypothesized that acquired reduction of antigen expression on the patient’s red cells leads to the development of the antibody, typically during pregnancy or after transfusion.13,51,52 Establishing whether an AnWj-negative phenotype is due to suppression or the rare inherited phenotype is not always clear-cut. Demonstration of a long-standing AnWj-negative phenotype (as in P1) or a clear pattern of inheritance (P2 and P8) provides strong evidence for the autosomal recessive genetic phenotype. Conversely, serological indicators such as a positive DAT or very weakly detectable antigen expression, combined with clinical information, may suggest suppression of antigen expression. Transient suppression would ideally be proven by follow-up samples, demonstrating the return of antigen expression and resulting loss of antibody (as has been shown in previous studies10,13), however, this is often not practicable. The 3 AnWj-negative individuals in this study without MAL mutations all had indications suggestive of a suppression cause of their negative phenotype (supplemental Table 1), although unfortunately retesting to confirm the return of AnWj expression was not possible. Genotyping for MAL mutation can now be used to determine whether an AnWj-negative phenotype is inherited or due to suppression, which may aid clinical decision-making processes. It is interesting that all the inherited AnWj-negative individuals tested in this study share the same MAL deletion. It remains to be seen whether other MAL variants affecting AnWj expression may be identified in future, but no homozygous nonsense variants or missense mutations encoding external amino acids are currently listed in the Genome Aggregation Database.

All AnWj-negative individuals tested lacked Mal expression on their erythrocytes, regardless of the presence or absence of MAL deletion. The mechanism of loss of Mal expression in those with no MAL deletion remains unclear. Mal is known to be downregulated in certain cancers,28-32 likely due to promoter hypermethylation, which may explain the transient loss of AnWj antigen in these individuals. Our results support the theory that Mal may be downregulated at the transcriptional or translational level, because no Mal protein is detectable on red cell membranes of the suppressed AnWj-negative phenotype by western blotting, serology, or flow cytometry. No pathological phenotype appears to be directly associated with the lack of Mal in either transient or inherited AnWj-negative individuals. The original Anton propositus (P1) together with P2 and several of her AnWj-negative family members have been well-studied over the course of many years, with no disease phenotype or red cell abnormalities found, despite their MAL deletions. Mal function may be nonessential or compensated, perhaps by another member of the MAL protein family.

AnWj antigen has previously been reported to be carried on CD4416,17 or at least require CD44 for its expression. In(Lu) phenotype cells, with reduced levels of CD44, have a significant reduction in AnWj expression,3-6 and a CD44-deficient individual was reported to be AnWj-negative.53 These observations have been used to support the theory that AnWj expression is dependent on CD44. However, our results show that both Mal and AnWj can be expressed on erythroid cells in vitro in the absence of CD44, so reduced CD44 levels do not explain aberrant AnWj antigen expression in In(Lu) or CD44-deficient phenotypes. Both phenotypes are associated with mutations in erythroid-specific transcription factor, KLF1,7,54,55 which has known roles in transcriptional regulation of multiple blood group genes. There is at least 1 KLF1 consensus binding site in the GC box region of the MAL proximal promoter,48,56 so erythrocyte Mal expression may be regulated by KLF1, explaining the reduced AnWj expression in KLF1 mutant phenotypes, although this remains to be proven.

More recently, inherited cases of AnWj-negative phenotype were reported to be associated with homozygosity for a rare, missense mutation in SMYD1,18 encoding a histone methyltransferase. Although members of 2 AnWj-negative families in our study do indeed show segregation of this mutation with the AnWj-negative phenotype, we also show other unrelated AnWj-negative individuals (including the original Anton propositus, P1) to lack the SMYD1 mutation. Both SMYD1 and MAL are located on chromosome 2, on either side of the centromere, so this association may be due to linkage between the SMYD1 variant and the MAL deletion, which appears to be restricted to a specific (Middle Eastern) population. Strong linkage disequilibrium has been demonstrated across centromeric gaps.57 In our study, all SMYD1 variant homozygotes were also homozygous for the MAL deletion, whereas heterozygous carriers of the SMYD1 mutation were concomitantly heterozygous for the MAL deletion allele. However, the observation of MAL deletion homozygotes with no SMYD1 mutation show that this linkage does not exist in all populations.

Many blood group antigens have known roles in infection and disease susceptibility, with several acting as pathogen receptors on the red cell surface. Perhaps the most well-known example is the Duffy blood group antigen, carried on atypical chemokine receptor 1 protein, acting as a receptor for binding of Plasmodium vivax to reticulocytes.58,59 AnWj antigen has been reported to act as the erythrocyte receptor for Hinfluenzae,6 and erythrocytes from individuals with the inherited AnWj-negative phenotype (including P2 from this current study) are not agglutinated by H influenzae.60 Mal has been identified as the erythrocyte receptor for binding of C perfringens epsilon toxin (ETX).26 ETX has been shown to cause hemolysis in humans but not in other mammals,61 and ETX does not bind to Mal KO mouse cells.62 Exposure to ETX has been proposed as a potential environmental trigger in the development of multiple sclerosis.63 More work is needed to elucidate the role of Mal/AnWj in red cell infection.

Levels of Mal membrane expression on mature red cells are low, and detection of Mal in the red cell proteome is variable,47 perhaps due to different sample preparation protocols and the nature of the Mal proteolipid. We were unable to demonstrate Mal membrane expression at any stage of primary cell culture (data not shown), so the pattern of Mal expression during erythropoiesis remains unclear. It is interesting to note that normal adult red cells show bimodal expression of AnWj/Mal by flow cytometry, and serologically, anti-AnWj exhibits characteristic mixed-field agglutination. This is indicative of only a proportion of cells expressing AnWj antigen, whereas others remain negative. A similar pattern of reactivity is seen with Lutheran antibodies,64 the reason for which has not, as yet, been explained.

Both cord cells and red cells of newborn babies lack AnWj antigen expression, and rapid transition of circulating red cells from AnWj-negative to AnWj-positive occurs shortly after birth.4 It is interesting, therefore, that the production of anti-AnWj in inherited AnWj-negative individuals appears to have been stimulated by pregnancy, albeit with no evidence of HDFN. Antibody production may have been stimulated by the presence of AnWj antigen on other fetal cell types. Although anti-AnWj is not implicated in HDFN, it is significant in transfusion,12,13 so the identification of AnWj-negative individuals, whether inherited or due to suppression, remains clinically important. Our findings allow for the development of new tests to detect such rare individuals, and the identification of natural human Mal knockouts allows for further study of the role of Mal in erythroid cells and wider biological processes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following individuals: Jan Frayne and Kongtana Trakarnsanga for provision of the BEL-A cell line; International Blood Group Reference Laboratory Molecular Diagnostics Department for Sanger sequencing support; Andrew Herman from the University of Bristol Faculty of Biomedical Sciences Flow Cytometry Facility for cell sorting support; Cyril Levene and Michael Bennett for their work in describing the first inherited AnWj family; Miguel A. Alonso (Centro de Biologia Molecular, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas—Universidad Autónoma de Madrid) for providing the anti-Mal 6D9 monoclonal antibody used in this study; Joyce Poole and Geoff Daniels for initiating this project; and finally the late Dave Anstee for his insights and many fruitful discussions and ideas about this long study.

This study was supported by National Health Service (NHS) Blood and Transplant R&D funding, the Cultural Bureau at the Royal Saudi Embassy in the United Kingdom and the Saudi Ministry of Education (S.A.A.; PhD scholarship), Medical Research Council (MR/V010506/1) (A.M.T. and T.J.S.), and infrastructure funding from the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Blood and Transplant Research Unit in Red Cell Products (IS-BTU-1214-10032).

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Authorship

Contribution: N.M.T., V.K.C., L.A.T., T.J.M., A.M.T., and T.J.S. conceived, designed, and coordinated the study; N.M.T., T.J.M., A.B., and B.J. performed serology experiments; L.A.T., V.K.C., and S.A.A. performed whole-exome/targeted sequencing, Sanger sequencing, and associated data analysis; T.J.S., T.J.M., and S.A.A. performed expression, CRISPR/CRISPR-associated protein 9, confocal, and flow cytometry experiments; T.J.S. and S.A.A. performed western blotting; V.Y. and L.F. performed antibody identification on patients P8 and P8_F1; B.K.S. made CD44 KO cell line and performed transcriptomics; P.J.W. carried out protein modeling; L.A.T., V.K.C., T.J.M., and N.M.T. wrote the manuscript; and all authors contributed to review of the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.M.T. is a cofounder, director, and consultant of Scarlet Therapeutics Ltd. T.J.S. is a cofounder and scientific consultant of Scarlet Therapeutics Ltd. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Nicole M. Thornton International Blood Group Reference Laboratory, NHS Blood and Transplant, 500 North Bristol Park, Northway, Filton, Bristol, BS34 7QH, United Kingdom; email: Nicole.thornton@nhsbt.nhs.uk.

References

Author notes

L.A.T., V.K.C., T.J.M., and S.A.A. are joint first authors.

Nucleotide sequence data are available in the DNA Data Bank of Japan/European Molecular Biology Laboratory/GenBank databases (accession number PP694609).

All other data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, Nicole M. Thornton (Nicole.thornton@nhsbt.nhs.uk).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal