FVIIa expressed by myeloid cells is crucial for integrin αMβ2–dependent migration on fibrin.

TF-FVIIa induces PAR2–β-arrestin–biased signaling in monocytes and macrophages.

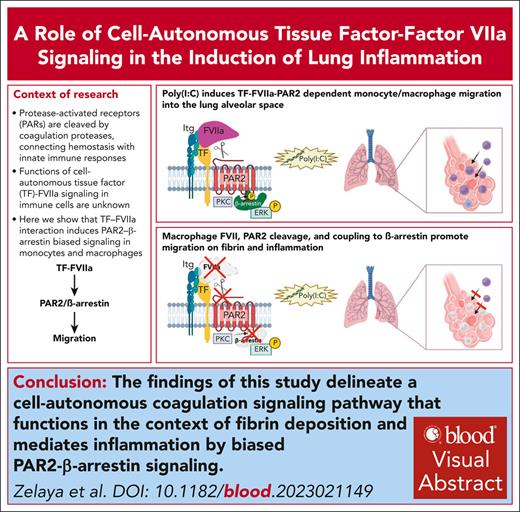

Visual Abstract

Protease activated receptors (PARs) are cleaved by coagulation proteases and thereby connect hemostasis with innate immune responses. Signaling of the tissue factor (TF) complex with factor VIIa (FVIIa) via PAR2 stimulates extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation and cancer cell migration, but functions of cell autonomous TF-FVIIa signaling in immune cells are unknown. Here, we show that myeloid cell expression of FVII but not of FX is crucial for inflammatory cell recruitment to the alveolar space after challenge with the double-stranded viral RNA mimic polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid [Poly(I:C)]. In line with these data, genetically modified mice completely resistant to PAR2 cleavage but not FXa-resistant PAR2–mutant mice are protected from lung inflammation. Poly(I:C)-stimulated migration of monocytes/macrophages is dependent on ERK activation and mitochondrial antiviral signaling (MAVS) but independent of toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3). Monocyte/macrophage-synthesized FVIIa cleaving PAR2 is required for integrin αMβ2-dependent migration on fibrinogen but not for integrin β1-dependent migration on fibronectin. To further dissect the downstream signaling pathway, we generated PAR2S365/T368A-mutant mice deficient in β-arrestin recruitment and ERK scaffolding. This mutation reduces cytosolic, but not nuclear ERK phosphorylation by Poly(I:C) stimulation, and prevents macrophage migration on fibrinogen but not fibronectin after stimulation with Poly(I:C) or CpG-B, a single-stranded DNA TLR9 agonist. In addition, PAR2S365/T368A-mutant mice display markedly reduced immune cell recruitment to the alveolar space after Poly(I:C) challenge. These results identify TF-FVIIa-PAR2-β-arrestin–biased signaling as a driver for lung infiltration in response to viral nucleic acids and suggest potential therapeutic interventions specifically targeting TF-VIIa signaling in thrombo-inflammation.

Introduction

Coagulation activation by the tissue factor (TF) pathway is a hallmark of severe acute bacterial and viral infections.1,2 Toll-like receptor (TLR), inflammatory, and oxidative signaling induce TF expression in immune and vascular cells, which, in turn, contributes to microvascular thrombosis and vascular dysfunction.3-5 TF is upregulated in chemically induced acute lung injury, but epithelial6 and myeloid cell7–expressed TF plays protective, rather than inflammatory, roles in this context. Beyond thrombosis and hemostasis, the extrinsic coagulation proteases factor X (FX), FVII, and thrombin also influence immune networks in inflammation and cancer via protease activated receptor (PAR) signaling.8 In fungal lung infections, PAR1 and PAR2 participate in inflammation by linking to different TLR-responses.9 In viral lung infections, TF-PAR1 signaling has been implicated in modulating antiviral immune responses,10 whereas PAR2 signaling in myeloid cells promotes11 or attenuates12,13 lung inflammation by incompletely understood mechanisms.

TF-FVIIa forms signaling complexes implicated in the regulation of immunity. When associated with the endothelial protein C receptor, TF-FVIIa-FXa activates PAR214 and mediates TLR4-dependent induction of interferon (IFN) responses.15,16 PAR2 cross talk amplifies TLR4 signaling17 and alternative macrophage activation.13 Similarly, tumor-associated macrophages synthesize FX that promotes cell autonomous FXa-PAR2 signaling and an immune suppressive phenotype.18 Myeloid cell PAR2 is also linked to FXa-mediated hypersensitivity in the skin,19 indicating broader immune regulatory functions. In a distinct signaling pathway, TF-FVIIa associates with integrins and directly cleaves PAR2.20 PAR2 signals via G-proteins or recruits β-arrestin to induce MAPK signaling.21 The scaffolding function of β-arrestin prolongs cytosolic extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation and promotes cancer cell migration and chemotaxis.22,23 Specific receptor–coagulation protease complexes as well as alternative cleavage of PARs,24 thus, can induce biased signaling by activating distinct signaling pathways.

It is unknown whether the TF-FVIIa-PAR2 signaling complex regulates responses to sensing of pathogen-associated molecular patterns by pattern-recognition receptors in innate immune cells. In addition to cell surface TLRs recognizing bacterial and fungal pathogen-associated molecular patterns, endosomal TLRs sense oligonucleotides derived from bacteria and viruses. TLR9 recognizes DNA, whereas TLR7 recognizes single-stranded and TLR3 double-stranded RNA (dsRNA). Cytosolic retinoic acid–inducible gene-I–like receptors also recognize microbial dsRNA and contribute to antiviral and proinflammatory responses.25

Because macrophages are known to synthesize FVII and FX in lung26,27 and other diseases,18,28,29 we hypothesized that the extrahepatic synthesis of coagulation factors contributes to local PAR signaling responses in extravascular milieus. We, therefore, studied the role of coagulation signaling by inducing lung inflammation with the dsRNA polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (Poly(I:C)), which mimics RNA generated during viral infections and activates TLR3 and cytosolic RNA sensors. In this model specifically reflective of microbial RNA sensing, we identify TF-FVIIa as the inducer of PAR2-biased β-arrestin signaling that promotes the fibrinogen-dependent migration of monocyte/macrophages in acute lung inflammation.

Materials and methods

Mice

Mutant and genetically matched wild-type (WT) mice were bred under identical housing conditions in the central animal facility of the University Medical Center Mainz. Animal experiments with age- and sex-matched mice were performed with approved protocols (23 177-07/G 14-1-055; Landesuntersuchungsamt Rheinland-Pfalz, Koblenz, Germany).

We used C57BL/6N PAR2R38E (F2rl1R38E),15,30 PAR2G37I (F2rl1G37I),18,F10flflLysMcre,18 and Itgb1flflLysMcre.30 C57BL/6N F7flfl (F7tm1c(EUCOMM)Hmgu/H mice from the European Mouse Mutant Archive)19 were crossed with either LysMcre (Lyz2tm1(cre)Ifo]) or CX3CR1cre (Cx3cr1tm1.1(cre)Jung). Experiments with conditional deletions used Cre-negative littermate controls. The intracellular domain of PAR2 carries protein kinase C (PKC) phosphorylation sites that are crucial for β-arrestin recruitment.21 We generated phosphorylation-deficient PAR2S365A/T368A (F2rl1S365A/T368A) mice by CRISPR/Cas-mediated targeting in C57BL/6N oocytes to change the F2rl1 coding sequence to 5′CGAgcgGTgaGggCgGTcAAc3′ (encoding the protein sequence RAVRAVN), which also introduced the silent BsrBI restriction site for genotyping. Founders were bred to homozygosity, sequence confirmed, and compared with C57BL/6N controls. Mitochondrial antiviral signaling (MAVS)-deficient mice (B6;129-Mavstm1Zjc/J) were used on a C57BL/6J background after in-house backcrossing by speed congenics (Taconic).

Cell isolation

Peritoneal lavage was collected from euthanized mice in 10 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and bovine serum albumin (BSA; 0.5%). Macrophages were selected by adhesion or purified with MACS mouse macrophage isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec). Bone marrow (BM) monocytes were isolated by flushing the bone, purified with MACS monocyte isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec), and resuspended in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) for functional assays.

FVII assays

FVII levels in citrate-anticoagulated plasma obtained by cardiac puncture were determined by clotting assay in FVII-deficient plasma (STA-Deficient VII, Diagnostica Stago). FVII protein was measured in serum-free cell supernatant of macrophages cultured overnight in DMEM with Vitamin K3 with a TF (Innovin, Dade) initiated FXa (Enzyme Research, Swansea, United Kingdom) generation assay calibrated with purified mouse FVIIa (kindly provided by NovoNordisk) and Spectrozyme FXa substrate (Biomedica Diagnostics).

FXa generation assay

Inhibition of TF by anti-TF21E10,31 anti-TF43D8 (Endpoint Health), or mouse immunoglobulin G2a (IgG2a) was measured on MC-38 cells in a FXa generation assay with mouse FVIIa (2 nM) and human FX (100 nM) (Enzyme Research).

Messenger RNA expression levels

We isolated RNA with TRIzol (Invitrogen) and synthesized complementary DNA with LunaScript Reverse Transcriptase (New England Biolabs) for semiquantitative polymerase chain reaction with Luna Universal quantitative polymerase chain reaction Master Mix (New England Biolabs) and normalization for 18S RNA using primers summarized in supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website.

Poly(I:C) lung inflammation model

Mice received 200 μg of Poly(I:C) or 100 μl of PBS (Sigma Aldrich) intranasally. Poly(I:C) was typically administered 3 times with 24-hour intervals, and pathology was scored 24 hours later.32 Cardiac puncture EDTA blood samples were analyzed with an automated hematology analyzer (Sysmex KX-21N). Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was obtained by flushing with PBS. BAL differential cell counts were determined with a Neubauer chamber and scoring 200 cells in BAL smears stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain. Perfused lungs were analyzed by histology of hematoxylin-eosin– and antibody MAC3-stained sections.

Flow cytometry

We analyzed lung single-cell suspensions based on the article by Yu et al.31 Briefly, after thoracotomy, the pulmonary circulation was perfused through a right heart catheterization with saline-EDTA to remove intravascular cells. Lungs were removed, minced, and incubated with 5 mL 1.5 mg/mL collagenase A, 10 U/mL DNase I (Roche) in DMEM at 37°C for 30 minutes with gently vortexing and passed through a 70-μm filter. White blood cells from EDTA blood samples were isolated by centrifugation and red blood cell lysis. Cells were stained with fixable viability dye (fixable viability dye eFluor 780, eBioscience), followed by the labeled antibodies listed in supplemental Table 2 in PBS and BSA (0.5%), and fixation with paraformaldehyde for analysis on an Attune NxT flow cytometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using Invitrogen Attune NxT Software for compensation and data acquisition. Data were analyzed with FlowJo version 10 (BD Biosciences).

Migration assay

For migration assays, we followed the protocol by Cao et al.33 Boyden chamber inserts (5 μm polycarbonate, Costar) were precoated on both sides with 50 μg/mL human plasminogen-, fibronectin-, factor XIII–depleted fibrinogen (Sekisui Diagnostics GmbH) or human fibronectin (BD Biosciences), blocked with BSA and placed on DMEM, 10% fetal calf serum in the lower chambers. Peritoneal macrophages or BM monocytes in serum-free DMEM with or without 25 μg/mL Poly(I:C) and 5 μM TLR9 agonist CpG-B (ODN1826, Invivogen) were seeded in the upper chambers for 4 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2. Inhibitors were added 10 minutes before Poly(I:C) stimulation: M1/70 (25 μg/ml), AZ3451 (1 μM), anti-TF21E10 (25 μg/mL), anti-TF43D8 or control mouse IgG2a (50 μg/mL), 5L15 (50 nM), TLR3 inhibitor (TLR3/dsRNA complex inhibitor, EMD Millipore, 27 μM), p38 inhibitor (SB 203580, 250 nM), ERK inhibitor (CAS 1049738-54-6, 25 μM). Cells remaining in the upper chamber were removed with a cotton swab, cells adhering to the lower surface were fixed and stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa for counting with a light microscope. The average number of migrating cells in the absence of stimulation was used for normalization.

In vitro assays

24-hour cell-free supernatant of peritoneal macrophages in DMEM, 10% fetal calf serum stimulated with 10 μg/mL Poly(I:C) was analyzed for secreted IFNα (Verkine mouse IFNα enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, PBL Assay Science) and IFNβ (DuoSet Mouse IFNβ, R&D Systems). Phospho-ERK was quantified in Poly(I:C)-stimulated cells fixed with paraformaldehyde (PFA, 4%), Triton X100 (0.2%) stained with phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Thr202/Tyr204, Cell Signaling), and counterstained with Alexa Fluor 555 anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin (Cell Signaling) and Hoechst 33342 for imaging on a Cytation5 (Biotek) with a 10× objective. The autofocus was set on the Hoechst signal and bright unspecific signals excluded by subpopulation image analysis. The nuclei were used as the primary mask to quantify nuclear phospho-ERK1/2 intensity, and the cytosolic area was defined as circles of 10-μM diameter around the nuclei. Δ object mean was calculated by subtracting the unstimulated object mean fluorescence from the stimulated object mean fluorescence.

Statistics

Mean and standard deviations of biological replicates are shown. GraphPad Prism 9.5.0 was used for statistical analysis by the 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the Sidak multiple comparison test or the 1-way ANOVA with the Tukey multiple comparison test for multiple groups or the two-tailed unpaired Student t test for 2 groups. Graphical illustrations were created with BioRender.

Results

FVII is required for Poly(I:C) induced monocyte/macrophage recruitment to the lung

Acute lung inflammation induced by the synthetic dsRNA analog Poly(I:C) models immune cell activation during viral infections and is associated with increased blood coagulation.32 FVII and FX synthesis has been documented in lung diseases.26,27 In addition to established myeloid cell FX-deleted F10flflLysMcre18 and FVII-deficient F7flflLysMcre mice,19 we generated F7flflCX3CR1cre mice with more specific deletion of FVII in monocytes/macrophages, but not neutrophils. FVII is expressed by peritoneal and lung macrophages,34 but myeloid cell FVII deletion did not alter functional FVII plasma levels (Figure 1A). However, peritoneal macrophages from F7flflLysMcre and F7flflCX3CR1cre mice expressed markedly lower levels of FVII messenger RNA (mRNA) and secreted less protein than F7flfl controls (Figure 1B). F7 deletion was also efficient in isolated lung macrophage (supplemental Figure 1). We used these mutant mice to address the role of myeloid cell–expressed coagulation factors in a Poly(I:C) challenge model of lung inflammation (Figure 1C).

FVII is required for Poly(I:C)-induced monocyte/macrophage recruitment to lung exudates. (A) FVII plasma levels in F7flflLysMcre vs in littermate F7flfl mice determined by clotting assay. (B) F7 mRNA and FVII-secreted protein in isolated peritoneal macrophages from F7flflLysMcre and F7flflCx3Cr1cre mice in comparison with littermate F7flfl controls. (C) Schematic overview of the standard experimental model of lung inflammation induced by intranasal Poly(I:C) application. (D) Schematic model of PAR2 activation by the TF-FVIIa-FXa complex involving the endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR). (E) Cell counts in BAL in unchallenged and Poly(I:C)-treated F10flflLysMcre and littermate F10flfl mice. (F) Schematic overview of PAR2 activation by the TF-FVIIa complex involving integrins. (G) Cell counts in BAL in unchallenged and Poly(I:C)-treated F7flflLysMcre and F7flfl littermate control mice. (H) Cell counts in BAL in F7flflCx3Cr1cre and F7flfl mice. (I) Cell counts in BAL of mice 24 hours after receiving 1 or 2 doses of Poly(I:C). Mean ± standard deviation (SD); the 2-way ANOVA with the Sidak multiple comparison test (E,G,I) or the unpaired Student t test (H). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Mo, monocytes; MՓ, macrophages.

FVII is required for Poly(I:C)-induced monocyte/macrophage recruitment to lung exudates. (A) FVII plasma levels in F7flflLysMcre vs in littermate F7flfl mice determined by clotting assay. (B) F7 mRNA and FVII-secreted protein in isolated peritoneal macrophages from F7flflLysMcre and F7flflCx3Cr1cre mice in comparison with littermate F7flfl controls. (C) Schematic overview of the standard experimental model of lung inflammation induced by intranasal Poly(I:C) application. (D) Schematic model of PAR2 activation by the TF-FVIIa-FXa complex involving the endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR). (E) Cell counts in BAL in unchallenged and Poly(I:C)-treated F10flflLysMcre and littermate F10flfl mice. (F) Schematic overview of PAR2 activation by the TF-FVIIa complex involving integrins. (G) Cell counts in BAL in unchallenged and Poly(I:C)-treated F7flflLysMcre and F7flfl littermate control mice. (H) Cell counts in BAL in F7flflCx3Cr1cre and F7flfl mice. (I) Cell counts in BAL of mice 24 hours after receiving 1 or 2 doses of Poly(I:C). Mean ± standard deviation (SD); the 2-way ANOVA with the Sidak multiple comparison test (E,G,I) or the unpaired Student t test (H). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. Mo, monocytes; MՓ, macrophages.

FXa generated by the TF-FVIIa complex cleaves PAR2 (Figure 1D), but myeloid cell deletion of FX did not impair leukocyte recruitment to the BAL after challenge (Figure 1E). Poly(I:C)-induced inflammatory BAL cell infiltration was quantified based on morphology and consisted predominantly of monocytes and macrophages, known to be derived from newly recruited inflammatory monocytes,35 with a lesser contribution of neutrophils and lymphocytes. The lack of appreciable differences not only excluded roles of macrophage-synthesized FX in this model of lung inflammation but also indicated that the LysMcre-driver expression did not affect leukocyte recruitment.

The TF-FVIIa complex associated with integrins20 also directly activates PAR2 (Figure 1F). Compared with littermate controls, F7flflLysMcre mice displayed attenuated Poly(I:C)-induced recruitment of leukocytes to the BAL (Figure 1G). Similarly, F7flflCX3CR1cre mice showed reduced leukocyte and monocyte/macrophage alveolar recruitment in response to Poly(I:C) (Figure 1H), supporting the importance of FVII expression in the monocytic lineage. In addition, leukocyte and macrophage/monocyte counts were lower in the BAL after 1or 2 doses of Poly(I:C) (Figure 1I), arguing that monocytic FVII specifically mediated the acute inflammatory response rather than indirectly by possible immune priming after multiple Poly(I:C) injections. All genotypes did not differ in standard blood cell counts after Poly(I:C) challenge (supplemental Figure 2A-B). Taken together, these data suggested that cell autonomous FVIIa signaling in monocytes/macrophages played a role in dsRNA-induced lung inflammation.

PAR2 cleavage is required for Poly(I:C)-induced monocyte/macrophage recruitment to the lung

We next compared PAR2R38E mutant mice, which are resistant to cleavage by all proteases, including FVIIa,15 but support PAR1/PAR2 heterodimer signaling,30 with FXa-resistant PAR2G37I mice (Figure 2A).18,19 PARG37I mice were indistinguishable from strain-matched WT controls in Poly(I:C)-induced alveolar recruitment of leukocytes (Figure 2B), in line with unaltered BAL counts in mice that lacked FX in myeloid cells (Figure 1E). In contrast, inflammatory cell counts in the BAL of PAR2R38E-mutant mice were markedly reduced (Figure 2B), although standard blood cell counts were unchanged (supplemental Figure 2C).

PAR2 cleavage is required for Poly(I:C)-dependent monocyte/macrophage recruitment to the lungs. (A) Schematic overview of PAR2 mutation PAR2G37I and PAR2R38 and their cleavage resistance to different proteases. (B) Cell count in BAL in unchallenged and Poly(I:C) treated of F2rl1G37I, F2rl1R38E and WT mice. (C) Flow cytometry gating strategy to identify different cell populations in whole lung cell suspensions, pregated on viable, single CD45+ cells. (D) Flow cytometry analysis of whole lung cell suspensions from F2rl1R38E and WT mice after Poly(I:C) treatment. Mean ± SD; the 2-way ANOVA with the Sidak multiple comparison test (panel A) or the unpaired Student t test (panel C). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. SSC, side scatter; MHCII, major histocompatibility complex class II; NK cells, natural killer cells.

PAR2 cleavage is required for Poly(I:C)-dependent monocyte/macrophage recruitment to the lungs. (A) Schematic overview of PAR2 mutation PAR2G37I and PAR2R38 and their cleavage resistance to different proteases. (B) Cell count in BAL in unchallenged and Poly(I:C) treated of F2rl1G37I, F2rl1R38E and WT mice. (C) Flow cytometry gating strategy to identify different cell populations in whole lung cell suspensions, pregated on viable, single CD45+ cells. (D) Flow cytometry analysis of whole lung cell suspensions from F2rl1R38E and WT mice after Poly(I:C) treatment. Mean ± SD; the 2-way ANOVA with the Sidak multiple comparison test (panel A) or the unpaired Student t test (panel C). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. SSC, side scatter; MHCII, major histocompatibility complex class II; NK cells, natural killer cells.

We next analyzed immune cell composition by flow cytometry of total lung cell suspensions, using a previously described marker panel36 to define CD45+ immune cell populations with a standardized gating strategy (Figure 2C). The abundance in neutrophils and natural killer cells was not different in the lungs of Poly(I:C)-challenged PAR2R38E vs WT mice (Figure 2D). T cells increased and B cells decreased in PAR2R38E mice (Figure 2D) but not in PAR2G37I mice (supplemental Figure 3A) relative to that in WT controls. Furthermore, inflammatory Ly6Chigh monocytes, alveolar macrophages, and CD11c+/CD11b+ dendritic cells were reduced in the lungs of PAR2R38E mice (Figure 2D) but not of PAR2G37I mice (supplemental Figure 3A), relative to the lungs of WT mice. Thus, accumulation of monocytes/macrophages in the BAL not only required cell autonomous FVII synthesis but also PAR2 activation, independent of FXa.

Myeloid FVII deficiency and PAR2 cleavage resistance regulate circulating inflammatory monocytes

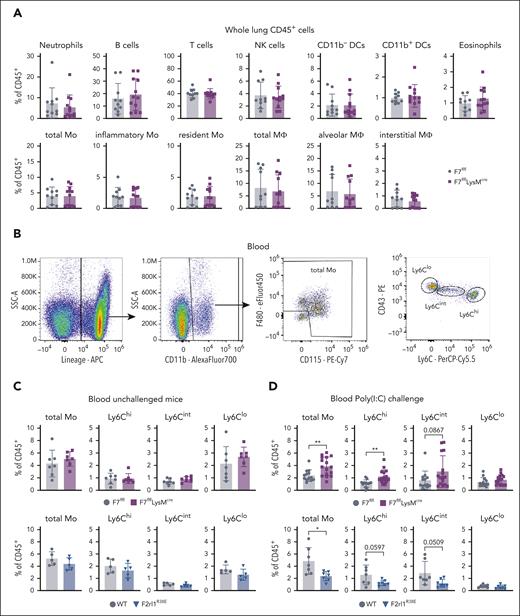

In contrast to the markedly reduced inflammatory monocyte and alveolar macrophage levels in whole lung cell suspensions of PAR2R38E mice, no differences were observed in F7flflLysMcre (Figure 3A) or F7flflCX3CR1cre (supplemental Figure 3B) relative to their F7flfl littermate controls after Poly(I:C) challenge. To resolve this apparent discrepancy between phenotypes, we focused on circulating monocytes, which are mobilized for local accumulation in the lung after Poly(I:C) challenge.37 Blood monocyte subpopulations were characterized by flow cytometry (Figure 3B). In unchallenged mice, blood monocyte distribution did not differ between FVII-deficient or PAR2R38E mice and their respective WT controls (Figure 3C).

Myeloid FVII deficiency and PAR2 cleavage insensitivity regulate circulating inflammatory monocytes. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of whole lung cell suspension after Poly(I:C) treatment of F7flflLysMcre compared with that of F7flfl littermate control mice. (B) Flow cytometry gating strategy of blood samples pregated on viable, single CD45+ cells. (C) Monocytes in blood after intranasal Poly(I:C) treatment of F7flflLysMcre and F7flfl littermate control mice or (D) F2rl1R38E and WT mice analyzed by flow cytometry. Mean ± SD; the unpaired Student t test ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01.

Myeloid FVII deficiency and PAR2 cleavage insensitivity regulate circulating inflammatory monocytes. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of whole lung cell suspension after Poly(I:C) treatment of F7flflLysMcre compared with that of F7flfl littermate control mice. (B) Flow cytometry gating strategy of blood samples pregated on viable, single CD45+ cells. (C) Monocytes in blood after intranasal Poly(I:C) treatment of F7flflLysMcre and F7flfl littermate control mice or (D) F2rl1R38E and WT mice analyzed by flow cytometry. Mean ± SD; the unpaired Student t test ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01.

Although myeloid cell FVII–deficient mice had higher levels of circulating and especially Ly6Chi inflammatory monocytes after Poly(I:C) challenge, these populations were reduced in PAR2R38E relative to those in WT mice without changes in Ly6Clo monocytes (Figure 3D). In addition, the immune cell composition in the lungs of unchallenged F7flflLysMcre mice showed a reduction in monocyte-derived CD11b+ dendritic cells but was otherwise similar to that in F7flfl littermate controls (supplemental Figure 4A). In contrast, lung inflammatory monocytes were already reduced in unchallenged PAR2R38E mice (supplemental Figure 4B), suggesting that hematopoietic roles demonstrated for PAR2R38E mice in embryogenesis38 extended to homeostasis at a steady state. The observed diminished lung accumulation of inflammatory monocytes in Poly(I:C)-challenged PAR2R38E mice (Figure 2D), thus, likely resulted from overall diminished circulating inflammatory monocyte levels after challenge (Figure 3D). In contrast, the markedly reduced accumulation of FVII-deficient inflammatory monocytes in the BAL (Figure 1G-I) despite efficient lung accumulation (Figure 3A) and even higher circulating inflammatory monocyte counts in F7flflLysMcre mice (Figure 3D), indicated a specific role for FVIIa signaling in transmigration of monocytes/macrophages into the alveolar space.

TF-FVIIa-PAR2 signaling regulates migration on fibrinogen

TF-FVIIa interacts with integrins and thereby regulates cell migration through PAR2 signaling.20,39 We hypothesized that PAR2 signaling controls migration specifically in the context of inflammation-associated coagulation activation and fibrin deposition. We, therefore, measured migration in a Boyden chamber assay on filters coated with fibrinogen, which engages the leukocyte integrin αMβ2 (CD11b/CD18) for macrophage activation in inflammation40,41 or the extracellular matrix protein fibronectin, a ligand for integrins α4β1 and α5β1 involved in macrophage TF trafficking.42 Poly(I:C) stimulation promoted migration of peritoneal macrophages or purified BM monocytes on both fibrinogen- and fibronectin-coated filters (Figure 4A,B). Migration on fibrinogen was blocked by the inhibitory anti-CD11b monoclonal antibody M1/7043 (Figure 4A), whereas integrin β1-deficient Itgb1flflLysMcre macrophages and monocytes showed diminished Poly(I:C)-stimulated migration on fibronectin (Figure 4B). This confirmed the involvement of alternative integrin complexes in matrix-specific migration.

TF-FVIIa-PAR2 signaling promotes migration on fibrinogen. (A) Migration of peritoneal macrophages and BM monocytes from C57BL/6N mice stimulated with Poly(I:C) (25 μg/mL) on fibrinogen-coated filters in the presence of inhibitory αMβ2 (M1/70, 25 μg/mL) antibody or control IgG. (B) Migration of macrophages and monocytes from Itgb1flflLysMcre and littermate Itgb1flfl WT control mice stimulated with Poly(I:C) on fibronectin-coated filters. (C-E) Migration of macrophages and monocytes from F2rl1R38E, F7flflLysMcre, F7flflCX3CR1cre, F10flflLysMcre, and WT control mice stimulated with Poly(I:C). (F) Inhibition of migration on fibrinogen with PAR2 antagonist AZ3451 (1 μM). (G) Migration of macrophages and monocytes from C57BL/6N mice with inhibitors anti-TF21E10 (25 μg/ml) or 5L15 (50 nM). (H) Fold induction of Poly(I:C) induced migration with and without 5 nM mouse FVII (mFVII) added to macrophages from F7flflLysMcre mice. Mean ± SD; the 1-way ANOVA with the Tukey multiple comparison test (A,F,G); the 2-way ANOVA with the Sidak multiple comparison test (B,C,D,E,H). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

TF-FVIIa-PAR2 signaling promotes migration on fibrinogen. (A) Migration of peritoneal macrophages and BM monocytes from C57BL/6N mice stimulated with Poly(I:C) (25 μg/mL) on fibrinogen-coated filters in the presence of inhibitory αMβ2 (M1/70, 25 μg/mL) antibody or control IgG. (B) Migration of macrophages and monocytes from Itgb1flflLysMcre and littermate Itgb1flfl WT control mice stimulated with Poly(I:C) on fibronectin-coated filters. (C-E) Migration of macrophages and monocytes from F2rl1R38E, F7flflLysMcre, F7flflCX3CR1cre, F10flflLysMcre, and WT control mice stimulated with Poly(I:C). (F) Inhibition of migration on fibrinogen with PAR2 antagonist AZ3451 (1 μM). (G) Migration of macrophages and monocytes from C57BL/6N mice with inhibitors anti-TF21E10 (25 μg/ml) or 5L15 (50 nM). (H) Fold induction of Poly(I:C) induced migration with and without 5 nM mouse FVII (mFVII) added to macrophages from F7flflLysMcre mice. Mean ± SD; the 1-way ANOVA with the Tukey multiple comparison test (A,F,G); the 2-way ANOVA with the Sidak multiple comparison test (B,C,D,E,H). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Poly(I:C) stimulation of PAR2R38E peritoneal macrophages or BM monocytes did not promote migration on fibrinogen-coated filters (Figure 4C). In contrast, Poly(I:C)-induced migration on fibronectin was indistinguishable between PAR2R38E and WT mice (Figure 4C), excluding a general signaling defect of this mouse strain. Remarkably, stimulated F7flflLysMcre or F7flflCXC3R1cre macrophages and monocytes also failed to migrate on the αMβ2 matrix fibrinogen-coated wells compared with F7flfl littermates-derived cells (Figure 4D). As seen with cleavage-resistant PAR2 mutant cells, migration on fibronectin was not impaired and even stimulated in Poly(I:C)-stimulated FVII–deficient cells (Figure 4D).

In line with unaltered BAL immune cell recruitment in myeloid cell FX–deficient mice (Figure 1E), migration of FX-deficient cells was unchanged on fibrinogen and fibronectin after Poly(I:C) stimulation (Figure 4E). The central role of TF-FVIIa-PAR2 signaling for monocyte/macrophage migration on fibrinogen was furthermore demonstrated by the inhibitory effects of the PAR2 antagonist AZ345144 (Figure 4F), anti-TF-21E10 blocking FVIIa binding,31 and the Kunitz-domain inhibitor 5L15 blocking FVIIa45 (Figure 4G). Remarkably, addition of recombinant mouse FVIIa did not restore the deficient migration of F7flflLysMcre macrophages (Figure 4H), suggesting that the promigratory TF-FVIIa complex forms during de novo synthesis of both proteins by monocyte/macrophages. Taken together, these data indicated that the TF-FVIIa complex was dispensable for migration on physiological extracellular matrix fibronectin but specifically enhanced monocyte/macrophage motility on the transitional fibrin(ogen) matrix generated under inflammatory conditions.

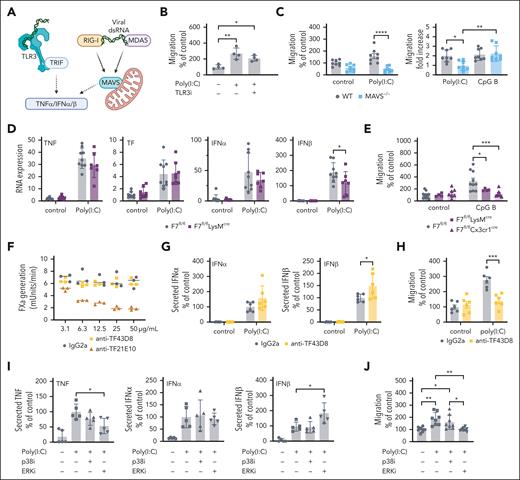

Monocyte/macrophage synthesis of FVII specifically regulates double-stranded, nucleotide-induced migration dependent on ERK signaling

We next analyzed the downstream signaling pathway regulated by TF-FVIIa-PAR2 signaling. Poly(I:C) is sensed by TLR3 coupling to TIR domain-containing adaptor-inducing IFNβ (TRIF) or the cytosolic sensors retinoic acid–inducible gene-I (RIG-I) and melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5) activating MAVS.46 Sensing of viral RNA leads to activation of the transcription factors NF-κB and IFN regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and, thereby, induces TNFα and anti-viral type 1 IFN (Figure 5A). Inhibition of TLR3 did not impair Poly(I:C)-stimulated migration (Figure 5B), but macrophages isolated from MAVS-deficient mice failed to migrate on fibrinogen (Figure 5C). Besides dsRNA, macrophages also sense foreign DNA through endosomal TLR9 signaling induced by unmethylated CpG dinucleotides. CpG-B induced migration of macrophages comparable with Poly(I:C) stimulation but independent of MAVS (Figure 5C).

Poly(I:C) stimulates migration and type 1 IFN induction via MAVS. (A) Schematic overview of Poly(I:C) signaling pathways via TLR3 or MAVS. (B) Migration of peritoneal macrophages from C57BL/6J mice stimulated with Poly(I:C) (25 μg/mL) on fibrinogen-coated filters in the presence of TLR3/dsRNA complex inhibitor (27 μM) (C) Migration of peritoneal macrophages from C57BL/6J WT mice and Mavs–/– mice stimulated with Poly(I:C) (25 μg/ml) or CpG-B (5 μM) on fibrinogen-coated filters. (D) Gene induction of TNFα, TF, IFNα and IFNβ by Poly(I:C) (10 μg/mL) of macrophages plated on fibrinogen from F7flflLysMcre mice in comparison to littermate F7flfl controls. (E) Migration of peritoneal macrophages on fibrinogen-coated filters from F7flflLysMcre and F7flflCx3Cr1cre mice in comparison to littermate F7flfl controls stimulated with CpG-B (5 μM). (F) FXa generation with anti-TF 43D8, anti-TF 21E10, or control mouse IgG2a on MC38 cells (G) IFNα and IFNβ secreted into the cell supernatant by peritoneal macrophages from C57BL6J mice treated with anti-TF 43D8 IgG2a (50 μg/mL) or control mouse IgG2a (50 μg/mL). (H) Migration of peritoneal macrophages from C57BL/6J mice stimulated with Poly(I:C) (25 μg/mL) on fibrinogen-coated filters in the presence of anti-TF 43D8 IgG2a (50 μg/mL) or control mouse IgG2a (50 μg/mL). (I) Secreted TNFα, IFNα, and IFNβ in the cell supernatant of WT peritoneal macrophages plated on fibrinogen-coated plates and stimulated with Poly(I:C) (10 μg/mL) and treated with p38 inhibitor (SB 203580, 250 nM) or with ERK inhibitor (CAS 1049738-54-6 25 μM). (J) Migration of peritoneal macrophages stimulated with Poly(I:C) (25 μg/mL) on fibrinogen-coated filters with p38 inhibitor (SB 203580, 250 nM) or with ERK inhibitor (CAS 1049738-54-6 25 μM). Mean ± SD; the 1-way ANOVA with the Tukey multiple comparison test (B,I,J); the 2-way ANOVA with the Sidak multiple comparison test (C,D,E,G,H). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Poly(I:C) stimulates migration and type 1 IFN induction via MAVS. (A) Schematic overview of Poly(I:C) signaling pathways via TLR3 or MAVS. (B) Migration of peritoneal macrophages from C57BL/6J mice stimulated with Poly(I:C) (25 μg/mL) on fibrinogen-coated filters in the presence of TLR3/dsRNA complex inhibitor (27 μM) (C) Migration of peritoneal macrophages from C57BL/6J WT mice and Mavs–/– mice stimulated with Poly(I:C) (25 μg/ml) or CpG-B (5 μM) on fibrinogen-coated filters. (D) Gene induction of TNFα, TF, IFNα and IFNβ by Poly(I:C) (10 μg/mL) of macrophages plated on fibrinogen from F7flflLysMcre mice in comparison to littermate F7flfl controls. (E) Migration of peritoneal macrophages on fibrinogen-coated filters from F7flflLysMcre and F7flflCx3Cr1cre mice in comparison to littermate F7flfl controls stimulated with CpG-B (5 μM). (F) FXa generation with anti-TF 43D8, anti-TF 21E10, or control mouse IgG2a on MC38 cells (G) IFNα and IFNβ secreted into the cell supernatant by peritoneal macrophages from C57BL6J mice treated with anti-TF 43D8 IgG2a (50 μg/mL) or control mouse IgG2a (50 μg/mL). (H) Migration of peritoneal macrophages from C57BL/6J mice stimulated with Poly(I:C) (25 μg/mL) on fibrinogen-coated filters in the presence of anti-TF 43D8 IgG2a (50 μg/mL) or control mouse IgG2a (50 μg/mL). (I) Secreted TNFα, IFNα, and IFNβ in the cell supernatant of WT peritoneal macrophages plated on fibrinogen-coated plates and stimulated with Poly(I:C) (10 μg/mL) and treated with p38 inhibitor (SB 203580, 250 nM) or with ERK inhibitor (CAS 1049738-54-6 25 μM). (J) Migration of peritoneal macrophages stimulated with Poly(I:C) (25 μg/mL) on fibrinogen-coated filters with p38 inhibitor (SB 203580, 250 nM) or with ERK inhibitor (CAS 1049738-54-6 25 μM). Mean ± SD; the 1-way ANOVA with the Tukey multiple comparison test (B,I,J); the 2-way ANOVA with the Sidak multiple comparison test (C,D,E,G,H). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Poly(I:C) induction of TNFα, TF, and IFNβ mRNA (supplemental Figure 5A) as well as secretion of IFNα and IFNβ (supplemental Figure 5B) were largely dependent on MAVS. In contrast, mRNA induction of these transcripts was independent of myeloid cell–expressed FVII (Figure 5D). Similarly, only modest reductions were seen in IFNα and IFNβ secretion in FVII-deficient macrophages. IFNs were secreted independently of myeloid cell–expressed FX and at even higher levels in Poly(I:C)-stimulated PAR2R38E macrophages compared to WT (supplemental Figure 5C). These data indicated that TF-FVIIa-PAR2 signaling specifically regulated migration but only marginally other responses dependent on cytosolic dsRNA sensing. Remarkably, FVII-deficient macrophages stimulated with CpG-B also failed to migrate on fibrinogen (Figure 5E), indicating broader roles for TF-FVIIa signaling in regulating macrophage migration induced by nucleic acid sensing.

The role of the TF-FVIIa signaling complex was further corroborated by antibody-inhibition experiments with a monoclonal antibody (anti-TF43D8) that specifically blocks TF-FVIIa signaling without interference of TF prothrombotic function (Figure 5F). Remarkably, this antibody had no effect on the Poly(I:C) induction of IFNα secretion and minimally increased IFNβ secretion (Figure 5G) yet significantly inhibited macrophage migration on fibrinogen (Figure 5H).

TF signaling has been linked to the activation of promigratory MAPK ERK1/2 and p38 mitogen–activated protein kinases.47,48 Poly(I:C) stimulation of macrophages on fibrinogen-coated wells in the presence of a p38 inhibitor resulted in unaltered TNFα and IFN secretion (Figure 5I). Inhibition of ERK slightly decreased TNFα production and increased IFNβ levels in the cell supernatant (Figure 5I). Importantly, inhibition of ERK markedly reduced Poly(I:C)-stimulated macrophage migration on fibrinogen, whereas p38 inhibition was without effect (Figure 5J). Thus, ERK activity was required for TF-FVIIa-PAR2 stimulated macrophage migration on the transitional extracellular matrix fibrinogen.

TF-FVIIa promotes inflammatory migration through PAR2–β-arrestin coupling

PAR2 couples to G-proteins but also recruits β-arrestin directly after PKC-mediated phosphorylation of Ser253/Thr258 located in the PAR2 intracellular carboxyl-terminal domain.21 PAR2 recruited β-arrestin acts as a scaffold for cytosolic MAPK activation, suggesting a potential mechanism for the observed ERK dependence of TF-FVIIa regulated macrophage migration (Figure 6A). The PKC phosphorylation site is species conserved and mutating positions Ser365 to Ala in mouse PAR2 does not affect tumor cell proangiogenic PAR2 signaling.49 In addition, β-arrestin has been implicated in proinflammatory effects in models of PAR2-dependent lung inflammation.50

PAR2-β-arrestin signaling drives Poly(I:C)-induced monocyte/macrophage recruitment to the lungs. (A) Schematic overview of downstream PAR2 signaling pathways via recruitment of β-arrestin or G-proteins. (B) IFNα and IFNβ secreted into the cell supernatant from macrophages from F2rl1S365A/T368A compared with WT mice on fibrinogen-coated plates. (C) Representative microscopic staining comparing the phosphorylation of ERK from peritoneal macrophage from F2rl1S365A/T368A and WT mice after Poly(I:C) stimulation (25 μg/mL). (D) Nuclear and cytosolic quantification of pERK with Citation5. (E) Migration of macrophages and monocytes from F2rl1S365A/T368A and WT mice on fibrinogen- or fibronectin-coated filters after Poly(I:C) stimulation (25 μg/mL). (F) Migration of macrophages from F2rl1S365A/T368A and WT mice on fibrinogen- or fibronectin-coated filters after CpG-B stimulation (5 μM). (G) Quantification of different monocyte and macrophage subsets by flow cytometry of whole lung cell suspensions after intranasal Poly(I:C) treatment of F2rl1S365A/T368A and WT mice. (H) Cell counts in BAL in unchallenged and Poly(I:C)-treated F2rl1S365A/T368A and C57BL/6N mice. Mean ± SD; the 2-way ANOVA with the Sidak multiple comparison test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. PKC, protein kinase C.

PAR2-β-arrestin signaling drives Poly(I:C)-induced monocyte/macrophage recruitment to the lungs. (A) Schematic overview of downstream PAR2 signaling pathways via recruitment of β-arrestin or G-proteins. (B) IFNα and IFNβ secreted into the cell supernatant from macrophages from F2rl1S365A/T368A compared with WT mice on fibrinogen-coated plates. (C) Representative microscopic staining comparing the phosphorylation of ERK from peritoneal macrophage from F2rl1S365A/T368A and WT mice after Poly(I:C) stimulation (25 μg/mL). (D) Nuclear and cytosolic quantification of pERK with Citation5. (E) Migration of macrophages and monocytes from F2rl1S365A/T368A and WT mice on fibrinogen- or fibronectin-coated filters after Poly(I:C) stimulation (25 μg/mL). (F) Migration of macrophages from F2rl1S365A/T368A and WT mice on fibrinogen- or fibronectin-coated filters after CpG-B stimulation (5 μM). (G) Quantification of different monocyte and macrophage subsets by flow cytometry of whole lung cell suspensions after intranasal Poly(I:C) treatment of F2rl1S365A/T368A and WT mice. (H) Cell counts in BAL in unchallenged and Poly(I:C)-treated F2rl1S365A/T368A and C57BL/6N mice. Mean ± SD; the 2-way ANOVA with the Sidak multiple comparison test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. PKC, protein kinase C.

To test the contributions of PAR2-β-arrestin coupling to monocyte/macrophage migration, we generated a mutant mouse carrying Ser365/Thr368 mutations to Ala by CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis. Homozygous PAR2S365/T368A mice with sequence confirmed genomic mutation appeared healthy without evidence of abnormal fertility or changes in steady state hematopoietic cell development (supplemental Tables 3 and 4; supplemental Figure 6). We evaluated PAR2, CD11b, and integrin β1 expression in peritoneal macrophages from PAR2S365/T368A mice and found no differences in surface expression levels compared with those in WT, PAR2R38E, and monocyte/macrophage FVII–deficient mice (supplemental Figure 7). In line with results of FVII-deficient and PAR2R38E macrophages, Poly(I:C)-induced secretion of IFNα and IFNβ was not reduced in PAR2S365/T368A mice (Figure 6B). We next analyzed ERK phosphorylation after Poly(I:C) stimulation by quantitative image analysis (Figure 6C). ERK phosphorylation peaked at 60 minutes. Nuclear ERK phosphorylation was indistinguishable between PAR2S365/T368A and WT macrophages (Figure 6D). In contrast, cytosolic ERK phosphorylation was markedly reduced in PAR2S365/T368A. Importantly, PAR2S253/T258A monocytes and macrophages showed reduced migration on fibrinogen but not fibronectin after Poly(I:C) (Figure 6E) or CpG-B stimulation (Figure 6F).

We next characterized these mice in the lung inflammation model. Blood counts after stimulation with Poly(I:C) were not different between PAR2S365/368A and strain-matched WT mice (supplemental Figure 8A), including circulating monocytes (supplemental Figure 8B). In line with the finding in myeloid cell FVII–deficient mice, total lung suspensions by flow cytometry showed similar numbers of inflammatory monocytes and macrophages after Poly(I:C) challenge (supplemental Figure 8C). However, PAR2S365/T368A mice also showed a decrease in B cells and increase in T cells vs WT mice after Poly(I:C) challenge, as seen with PAR2R38E mice (Figure 2D). These data indicated that PAR2-β-arrestin–biased signaling (independent of myeloid cell–synthesized FVII) also regulated adaptive immune responses. Importantly, extravasation of leukocytes into the alveolar space was markedly attenuated in the PAR2S365/T368A mice (Figure 6G) and phenocopied mice with FVII deficiency in monocytic cells. Analysis of lung histology after Poly(I/C) challenge revealed no differences in macrophage counts in macrophage FVII–deficient or PAR2S365/T368A mice compared with their respective WT controls (supplemental Figure 9). Taken together, these data identify cell autonomous TF-FVIIa-PAR2–biased signaling through cytosolic ERK MAPK coupling as a central mechanism for alveolar immune cell recruitment in lung inflammation in response to dsRNA sensing.

Discussion

Here, we identify a role of cell autonomous TF-FVIIa-PAR2 signaling in acute lung inflammation induced by the dsRNA analog Poly(I:C). This signaling pathway is specifically triggered by monocyte/macrophage-derived FVII, but not FX, although both proteases are locally expressed in lung diseases.26,27 Cleavage-insensitive PAR2R38E mice but not the FXa-resistant PAR2G37I mice show diminished inflammatory cell recruitment to the BAL, directly implicating proteolytic PAR2 signaling by TF-FVIIa. Although PAR2 can be activated by a variety of myeloid cell–expressed proteases, FVII expression is a lineage characteristic of lung and peritoneal macrophages.34 Our data demonstrate that the identified TF-FVIIa-PAR2 signaling pathway specifically supports monocyte and macrophage migration mediated by integrin αMβ2 on fibrinogen generated in inflammation but not on the physiological extracellular fibronectin. These findings demonstrate crucial immune cell functions of the previously described interactions of the TF-FVIIa complex with integrins in cancer cell migration and metastasis.20,39,51-53

TF-FVIIa-PAR2 signaling mediates ERK- but not p38-dependent migration on fibrinogen. With a newly generated mutant mouse model deficient in cytosolic ERK activation downstream of PAR2-β-arrestin (PAR2S365/T368A mice), we show that TF-FVIIa induces biased PAR2 signaling in this monocyte/macrophage inflammatory response. PARs have been implicated in the regulation of TLR signaling9,13,17 that are linked to viral infections.10,11,54,55 However, we show here that macrophage migration and IFN production induced by the viral RNA mimic Poly(I:C) are primarily mediated by cytosolic sensors signaling through MAVS in a TLR3-independent pathway. Although TLR4-dependent IFN responses in monocytes and dendritic cells are specifically dependent on TF-FVIIa-FXa–endothelial protein C receptor–PAR2 signaling,15,16 the Poly(I:C) induction of type 1 IFNs through MAVS did not require TF-FVIIa. In addition, the regulation of macrophage migration on fibrinogen by TF-FVIIa-PAR2 signaling extends to MAVS-independent promigratory effects of TLR9 activated by CpG-B, indicating broader roles of the identified signaling pathway in nucleic acid–induced myeloid cell migration.

PAR2S365/T368A mice phenocopy FVII deficiency in protection from lung inflammation, emphasizing the crucial role of ERK scaffolding56 as central for immune cell migration in inflammation. We also present data with a monoclonal antibody to mouse TF that mimics prototypic monoclonal antibodies to human TF that specifically block TF-FVIIa endosomal trafficking,30 conformational transitions,42 and signaling20 without effects on coagulation. Specifically blocking TF-FVIIa signaling with anti–mouse-TF43D8 also blocked macrophage migration without reducing Poly(I:C)-induced IFN responses. The recruitment and migration of monocytes are essential for effective control and clearance of viral invasion; therefore, modulating this signaling axis could be a promising tool for treating viral infections.

Monocytes exit the blood to mediate their functions in extravascular locations. During vessel wall transmigration, monocyte engagement of P-selectin induces the upregulation of TF.57,58 Notably, functions of TF in the extravascular space and the ultimate exit of monocytes/macrophages into alveolae requires the cell autonomous synthesis of FVII. These findings add to the emerging evidence that the hemostatic system functions independent of the plasmatic coagulation cascade to regulate immunity,18 inflammation,28 and hematopoiesis.59,60

Acknowledgments

The authors thank P. Wilgenbus and G. Carlino for assisting in managing the mouse colonies.

This study was supported by the German Research Foundation (project number 318346496, SFB1292/2 TP02/TP10), the Humboldt Foundation of Germany (Humboldt Professorship to W.R.; Georg Forster Research Fellowship to H.Z.), a Marie Curie Career Integration Grant of the European Union (project 334486) (M.B.), National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants HL133348 (H.W.) and HL141513 (M.B.), Cluster of Excellence iFIT (EXC 2180) (I.G.-M. and L.Q.-M.), and research support by Endpoint Health (W.R.).

This work contains results that are part of the PhD thesis of K.G. at the Center for Thrombosis and Hemostasis, Johannes-Gutenberg-University Mainz, Mainz, Germany.

Authorship

Contribution: H.Z. and K.G. designed, performed, and analyzed experiments and wrote the manuscript; T.S.N., A.H., C.W., S.R., I.G.-M., and L.Q.-M. performed and analyzed experiments; M.B. provided crucial reagents; H.W. generated mice and provided input; and W.R. conceptualized and directed the study and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: W.R. is a consultant for Endpoint Health. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Wolfram Ruf, Center for Thrombosis and Hemostasis, University Medical Center of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Langenbeckstr 1, 55131 Mainz, Germany; email: ruf@uni-mainz.de.

References

Author notes

H.Z. and K.G. contributed equally to this study.

Original data, protocols, and reagent information are available on request from the corresponding author, Wolfram Ruf (ruf@uni-mainz.de).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal