Key Points

The GPIbM/VWF:Ag ratio is a valuable tool for timely aVWS diagnostics during intraoperative coagulation monitoring of infants with CHD.

aVWS is not a major cause of bleeding during cardiac surgery, but its correction might be beneficial in selected cases.

Abstract

Acquired von Willebrand syndrome (aVWS) has been reported in patients with congenital heart diseases associated with shear stress caused by significant blood flow gradients. Its etiology and impact on intraoperative bleeding during pediatric cardiac surgery have not been systematically studied. This single-center, prospective, observational study investigated appropriate diagnostic tools of aVWS compared with multimer analysis as diagnostic criterion standard and aimed to clarify the role of aVWS in intraoperative hemorrhage. A total of 65 newborns and infants aged 0 to 12 months scheduled for cardiac surgery at our tertiary referral center from March 2018 to July 2019 were included in the analysis. The glycoprotein Ib M assay (GPIbM)/von Willebrand factor antigen (VWF:Ag) ratio provided the best predictability of aVWS (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve [AUC], 0.81 [95% CI, 0.75-0.86]), followed by VWF collagen binding assay/VWF:Ag ratio (AUC, 0.70 [0.63-0.77]) and peak systolic echocardiographic gradients (AUC, 0.69 [0.62-0.76]). A cutoff value of 0.83 was proposed for the GPIbM/VWF:Ag ratio. Intraoperative high-molecular-weight multimer ratios were inversely correlated with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) time (r = −0.57) and aortic cross-clamp time (r = −0.54). Patients with intraoperative aVWS received significantly more fresh frozen plasma (P = .016) and fibrinogen concentrate (P = .011) than those without. The amounts of other administered blood components and chest closure times did not differ significantly. CPB appears to trigger aVWS in pediatric cardiac surgery. The GPIbM/VWF:Ag ratio is a reliable test that can be included in routine intraoperative laboratory workup. Our data provide the basis for further studies in larger patient cohorts to achieve definitive clarification of the effects of aVWS and its potential treatment on intraoperative bleeding.

Introduction

The development of diagnostic methods has led to increasing diagnosis of acquired von Willebrand syndrome (aVWS) as a bleeding diathesis and has raised the awareness of physicians for this disease in recent years. Heterogeneous etiologies can lead to the characteristic decrease or loss of von Willebrand high-molecular-weight multimers (HMWMs).1 In the context of congenital heart disease (CHD), distinct anatomic features causing high shear due to high gradients in the circulation can lead to increased secretion,2,3 unfolding, and subsequent proteolytic clearance of HMWMs within their mechanosensitive A2 domain by von Willebrand factor–cleaving protease (ADAMTS13).4 Patent arterial ducts (PDAs),5 ventricular septal defects (VSDs),6 aortic7 or pulmonary valve stenosis,8 and pulmonary hypertension9 have previously been found to be associated with aVWS. The severity of stenosis has been shown to be in linear relationship to the grade of HMWM decrease.10 In a previous study, we reported an intraoperative aVWS incidence of up to 66% in neonates undergoing heart surgery for complex CHD.11 Although extracorporeal circulation support (ECLS) and ventricular assist devices are proven to trigger aVWS,12,13 the impact of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) on intraoperative development of aVWS in pediatric patients is still unclear. Available data in adults show that CPB does not induce clinically relevant aVWS.14

Moreover, the role of aVWS among the numerous hemostatic abnormalities after CPB is still controversial.15 It is unclear whether aVWS correction with von Willebrand factor (VWF) concentrates could be of clinical benefit.

Intraoperative testing for aVWS is complicated because no point-of-care testing method for its detection exists so far. The criterion standard for diagnosing aVWS is the time-consuming VWF multimer analysis. Impaired VWF functional markers, such as ratio of ristocetin cofactor activity (VWF:RCo) to VWF antigen (VWF:Ag) <0.7 or collagen-binding (VWF:CB)/VWF:Ag <0.8 have been proposed as possible indicators of aVWS.16 However, these are not reliable as diagnostic tools17; moreover, both tests are also quite time consuming. In 2014, Patzke et al introduced the VWF:GPIbM assay for measurement of platelet-dependent VWF activity based on the binding of VWF to recombinant glycoprotein Ib (GPIb).18 The test is of superior precision and sensitivity compared with the VWF:RCo assay. It is automated and can be performed in a timely manner. At our institution, it takes 1 hour from blood collection to result. To our knowledge, data on its diagnostic value in pediatric cardiac surgery are still lacking.

The aim of the present study was to identify rapid diagnostic markers for aVWS that can be used in clinical practice for the intraoperative diagnosis of aVWS. Because cardiac surgery on CPB in neonates and infants is frequently associated with bleeding complications,19 we evaluated the role of aVWS in intraoperative bleeding and postoperative bleeding complications.

Methods

Study design and setting

We performed a single-center, prospective, observational trial for evaluation of the clinical and laboratory manifestations of aVWS in newborns and infants with CHD who underwent cardiac surgery with or without CPB at our tertiary referral center from March 2018 to July 2019. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of the University of Tübingen (159/2017BO1). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consents were obtained from the parents of the participating children before inclusion and before any study-related procedures.

Patient selection

During the study period all patients scheduled for cardiac surgery due to CHD were screened for possible inclusion in this study. Inclusion criteria were age 0 to 12 months and diagnosis of CHD requiring corrective or palliative cardiac surgery.

The following criteria resulted in secondary exclusion from the data analysis: diagnosis of congenital von Willebrand syndrome (VWS) at initial study sampling, need for ECLS at the time of sampling, and failures in collection or processing of intraoperative blood samples. aVWS data on unplanned revision surgeries during the same inpatient stay were not collected.

Patients were divided into 4 groups according to the type of surgery: (I) complex univentricular palliation in neonates and young infants, (II) complex biventricular repair in neonates, (III) surgery without CPB, and (IV) nonneonatal biventricular repair with CPB.

Blood sampling and echocardiographic assessment were conducted at 4 time points: up to 24 hours before surgery, intraoperatively immediately after weaning from CPB and before administration of any further VWF-containing blood components (fresh frozen plasma [FFP], platelet concentrate [PLT], or VWF-containing concentrate), on the first postoperative day, and before removal of the central venous line. All echocardiography was performed by pediatric cardiologists. Pressure gradients were calculated with the use of the modified Bernoulli equation based on Doppler measurements of the highest peak systolic instantaneous gradient at any localization.

Data, including echocardiography findings, laboratory results, blood component therapy, and bleeding and thrombotic events, were collected prospectively based on the study protocol. Data were independently reviewed by V.I. and J.E., and H.M. was consulted in case of disagreements. All authors had access to primary clinical trial data.

Coagulation management and CPB details

CPB circuits contained the Sorin Kids D100 oxygenator and venous reservoir combination (Livanova, London, UK) driven by an S5 Perfusion System (Livanova). Priming consisted of an isotonic and isotonic crystalloid solution (Jonosteril 1/1E; Fresenius Kabi, Bad Homburg, Germany) and unfractioned heparin (UFH). FFP and red blood cell concentrate (RBC) were added to the CPB prime solution in neonates who underwent complex surgeries.

Anticoagulation during CPB was managed with individual UFH and protamine doses calculated with the Hepcon system (HMS Plus; Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN). The detailed protocol of UFH/protamine management has been previously published.20 Antifibrinolytic treatment with tranexamic acid was given to all patients during surgery with CPB. Patients undergoing surgery without CPB received a single dose of UFH (100 IE per kg body weight) and no tranexamic acid. Intraoperative coagulation management followed a TEG6s-based (Haemonetics Corp, Braintree, MA) algorithm for all patients. Anesthetists did not have access to VWF results at the time of intraoperative blood component treatment. After separation from CPB, FFP was used as volume therapy and to treat obligatory loss coagulopathy in addition to factor concentrates. Intraoperative bleeding was indirectly quantified by comparing substituted blood components and thoracic closure times (defined as the time from protamine administration to the end of surgery).

Postoperative bleeding was quantified by measurement of chest tube secretion over the 24 hours after surgery. Prophylactic postoperative anticoagulation was performed with 10 IU UFH per kg body weight and hour after biventricular repair. Patients with univentricular palliation received UFH in a dose to achieve 1.5- to 2-fold prolongation of initial activated partial thromboplastin time.

Laboratory analysis

Measurements of VWF:Ag, VWF:CB, VWF:GPIbM, factor VIII activity (FVIII:C), VWF multimer analysis, and global coagulation parameters (international normalized ratio, activated partial thromboplastin time, fibrinogen, antithrombin, and platelet counts) were performed in the Department of Laboratory Medicine of the University Hospital of Tübingen. VWF binding activity to GPIbM was measured with the use of a commercially available test (Innovance VWFAcAssay; Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Erlangen, Germany) at the Sysmex CS-5100 analyzer (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). Analyses of von VWF:Ag, VWF:CB, and FVIII:C and multimer analysis were performed as described previously.21,22 Plasma samples for multimer analysis were stored frozen at −74°C. Sodium dodecyl sulfate electrophoresis for VWF multimer analysis was performed at an external reference laboratory (cMedilys Coagulation Lab, Asklepios Clinic, Hamburg, Germany) with the use of densitometric gel analysis. The HMWM ratio was calculated as the proportion of HMWMs in patient blood compared with control plasma and used as a continuous reference variable. The aVWS was graded as severe (++) if the HMWMs were less than 20% of all multimers. Moderate aVWS (+) was defined as a complete or relative loss of the largest HMWMs, resulting in values of 20% to 25% of all multimers and a disproportion between high- and low-molecular-weight multimers.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses and the design of the figures were carried out with the SAS JMP software (version 15.2.0; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Normal distribution was tested by means of the Shapiro-Wilk W test. Group comparisons of normally distributed variables were performed with the use of Student t tests. Non-normally distributed continuous variables were compared with the use of Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) with calculation of 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was used to assess the relation between 2 continuous variables. The predictive value of prognostic factors of aVWS was evaluated by examining the area under the receiver operator characteristic curve (AUC) using a CI of 95% based on the easyROC webtool.23 Optimal cutoff values were determined using the Max Se/Sp method.24,25 Statistical significance was defined as a probability of P < .05.

Results

Patient recruitment and characteristics

A total of 75 consecutive patients scheduled for cardiac surgery were screened for inclusion in the study. The parents of 4 children refused to participate, resulting in 71 patients being enrolled. During the study period, 1 patient had to be later excluded from data analysis owing to detection of congenital VWS and the need of perioperative VWF replacement. Four patients were later excluded owing to failures in collection or processing of the intraoperative blood samples. One patient was later excluded from analysis owing to prolonged ECLS therapy initiated after weaning from CPB and continuing until his death 3 weeks later. In total, 65 patients were finally included in the study and were categorized into 4 groups according to age and type of surgery. Detailed information on the recruitment process is provided in supplemental Figure 1 on the Blood website. Fourteen patients with functional univentricular hearts underwent palliative surgery (group I), 17 patients received corrective surgery in the neonatal period (group II), 10 patients had surgery without the use of CPB (group III), and 24 patients had corrective surgery at a later stage in infancy (group IV). Four patients in group I were on ECLS therapy at the time of the third blood collection (24 hours after surgery), so the data of this time point were excluded from analyses to avoid possible influences caused by ECLS. The final blood sampling was performed a median 9 days after surgery (IQR, 6-14 days; range, 2-51 days).

Detailed data on patient characteristics, baseline coagulation parameters, CPB data, and performed surgeries are provided in Table 1 and supplemental Table 1. Median CPB duration of the entire cohort was 107 minutes (IQR, 53-164 minutes). Median aortic cross-clamp (ACC) duration was 67 minutes (IQR, 27-108 minutes). Median reperfusion time was 34 minutes (IQR, 32-36 minutes), median minimal intraoperative temperature was 34°C (32°C-36°C). The median postoperative stay in the intensive care unit was 9 days (IQR, 6-13 days).

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics

| . | Group I: single ventricle . | Group II: neonatal biventricular . | Group III: without CPB . | Group IV: nonneonatal biventricular . | Entire cohort . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (% of all) | 14 (21.5) | 17 (26.2) | 10 (15.4) | 24 (36.9) | 65 (100) |

| Sex male | 9 (64.3) | 10 (58.8) | 5 (50) | 15 (62.5) | 39 (60) |

| Age, d | 14 (9-48) | 12 (8-18) | 44 (15-108) | 167 (114-222) | 46 (12-151) |

| Weight, kg | 3.6 (3.1-3.9) | 3.3 (2.9-3.7) | 3.6 (2.0-5.6) | 6.1 (4.1-6.9) | 3.9 (3.1-5.8) |

| Performed surgeries | |||||

| mBTS or PDA-stent, ASE, and bipulmonary banding | 3 (4.6) | – | – | – | 3 (4.6) |

| mBTS implantation | 3 (4.6) | – | – | – | 3 (4.6) |

| Norwood type procedure | 8 (12.4) | – | – | – | 8 (12.4) |

| Arterial switch | – | 9 (13.8) | – | – | 9 (13.8) |

| Aortic valve repair | – | 2 (3.1) | – | 1 (1.5) | 3 (4.6) |

| Aortic coarctation repair | – | – | 5 (7.7) | – | 5 (7.7) |

| Pulmonary banding | – | – | 2 (3.1) | – | 2 (3.1) |

| PDA ligation | – | – | 3 (4.6) | – | 3 (4.6) |

| TOF repair | – | – | – | 10 (15.4) | 10 (15.4) |

| Biventricular repair (others) | – | 6 (9.2) | – | 13 (20) | 19 (29.2) |

| CPB time, min | 116 (77-163) | 150 (94-206) | – | 109 (75-161) | 107 (53-164) |

| ACC time, min | 63 (26-89) | 114 (56-164) | 10 (0-22) | 77 (58-104) | 67 (27-109) |

| Reperfusion, min | 40 (23-76) | 18 (10-27) | – | 11 (6-17) | 13 (6.8-27) |

| Minimal temperature (% within group) | |||||

| Normothermia | 2 (3.1) | – | 9 (13.8) | 9 (13.8) | 20 (30.8) |

| 32°C-36°C | 5 (7.7) | 13 (20) | 1 (1.5) | 15 (23.1) | 34 (52.3) |

| Below 32°C | 7 (10.8) | 4 (6.2) | – | – | 11 (16.9) |

| Median, °C | 32 (28-35) | 32 (31.5-33.5) | 37 (36-37) | 35 (34-36.3) | 34 (32-36) |

| Postoperative stay in ICU, d | 13 (10-46) | 9 (7-17) | 4 (3-10) | 8 (5-10) | 9 (6-13) |

| Laboratory parameters at baseline | |||||

| aPTT, s | 33.5 (29.8-41) | 34.5 (32-36.8) | 33.5 (31.2-38.8) | 32 (30-33.8) | 33 (30.3-35.0) |

| INR | 1.13 (1.11-1.18) | 1.16 (1.11-1.28) | 1.13 (1.05-1.21) | 1.15 (1.07-1.22) | 1.15 (1.09-1.22) |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL | 202 (135-269) | 185 (116-239) | 208 (180-226) | 178 (149-218) | 191 (149-229) |

| Platelets, ×103/μL | 288 (241-441) | 356 (210-483) | 315 (249-440) | 380 (317-533) | 346 (254-511) |

| Hemoglobin, mg/dL | 15.2 (13.5-16.7) | 14.2 (12.9-15.5) | 12.2 (11.0-13.1) | 12.7 (11.0-14.7) | 13.2 (11.9-15.2) |

| Antithrombin, % | 66 (58-101) | 64 (46-72) | 66 (49-75) | 76 (68-91) | 69 (60-81) |

| FVIII:C, % | 89 (74-118) | 99 (82-105) | 84 (79-120) | 78 (64-114) | 85 (72-109) |

| VWF:Ag, % | 108 (91-125) | 108 (81-130) | 118 (101-190) | 89 (58-114) | 105 (83-126) |

| . | Group I: single ventricle . | Group II: neonatal biventricular . | Group III: without CPB . | Group IV: nonneonatal biventricular . | Entire cohort . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (% of all) | 14 (21.5) | 17 (26.2) | 10 (15.4) | 24 (36.9) | 65 (100) |

| Sex male | 9 (64.3) | 10 (58.8) | 5 (50) | 15 (62.5) | 39 (60) |

| Age, d | 14 (9-48) | 12 (8-18) | 44 (15-108) | 167 (114-222) | 46 (12-151) |

| Weight, kg | 3.6 (3.1-3.9) | 3.3 (2.9-3.7) | 3.6 (2.0-5.6) | 6.1 (4.1-6.9) | 3.9 (3.1-5.8) |

| Performed surgeries | |||||

| mBTS or PDA-stent, ASE, and bipulmonary banding | 3 (4.6) | – | – | – | 3 (4.6) |

| mBTS implantation | 3 (4.6) | – | – | – | 3 (4.6) |

| Norwood type procedure | 8 (12.4) | – | – | – | 8 (12.4) |

| Arterial switch | – | 9 (13.8) | – | – | 9 (13.8) |

| Aortic valve repair | – | 2 (3.1) | – | 1 (1.5) | 3 (4.6) |

| Aortic coarctation repair | – | – | 5 (7.7) | – | 5 (7.7) |

| Pulmonary banding | – | – | 2 (3.1) | – | 2 (3.1) |

| PDA ligation | – | – | 3 (4.6) | – | 3 (4.6) |

| TOF repair | – | – | – | 10 (15.4) | 10 (15.4) |

| Biventricular repair (others) | – | 6 (9.2) | – | 13 (20) | 19 (29.2) |

| CPB time, min | 116 (77-163) | 150 (94-206) | – | 109 (75-161) | 107 (53-164) |

| ACC time, min | 63 (26-89) | 114 (56-164) | 10 (0-22) | 77 (58-104) | 67 (27-109) |

| Reperfusion, min | 40 (23-76) | 18 (10-27) | – | 11 (6-17) | 13 (6.8-27) |

| Minimal temperature (% within group) | |||||

| Normothermia | 2 (3.1) | – | 9 (13.8) | 9 (13.8) | 20 (30.8) |

| 32°C-36°C | 5 (7.7) | 13 (20) | 1 (1.5) | 15 (23.1) | 34 (52.3) |

| Below 32°C | 7 (10.8) | 4 (6.2) | – | – | 11 (16.9) |

| Median, °C | 32 (28-35) | 32 (31.5-33.5) | 37 (36-37) | 35 (34-36.3) | 34 (32-36) |

| Postoperative stay in ICU, d | 13 (10-46) | 9 (7-17) | 4 (3-10) | 8 (5-10) | 9 (6-13) |

| Laboratory parameters at baseline | |||||

| aPTT, s | 33.5 (29.8-41) | 34.5 (32-36.8) | 33.5 (31.2-38.8) | 32 (30-33.8) | 33 (30.3-35.0) |

| INR | 1.13 (1.11-1.18) | 1.16 (1.11-1.28) | 1.13 (1.05-1.21) | 1.15 (1.07-1.22) | 1.15 (1.09-1.22) |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL | 202 (135-269) | 185 (116-239) | 208 (180-226) | 178 (149-218) | 191 (149-229) |

| Platelets, ×103/μL | 288 (241-441) | 356 (210-483) | 315 (249-440) | 380 (317-533) | 346 (254-511) |

| Hemoglobin, mg/dL | 15.2 (13.5-16.7) | 14.2 (12.9-15.5) | 12.2 (11.0-13.1) | 12.7 (11.0-14.7) | 13.2 (11.9-15.2) |

| Antithrombin, % | 66 (58-101) | 64 (46-72) | 66 (49-75) | 76 (68-91) | 69 (60-81) |

| FVIII:C, % | 89 (74-118) | 99 (82-105) | 84 (79-120) | 78 (64-114) | 85 (72-109) |

| VWF:Ag, % | 108 (91-125) | 108 (81-130) | 118 (101-190) | 89 (58-114) | 105 (83-126) |

Values are presented as n (%) or median (IQR).

–, 0%; aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; ASE, atrioseptectomy; ICU, intensive care unit; INR, international normalized ratio; mBTS, modified Blalock-Taussig shunt; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot.

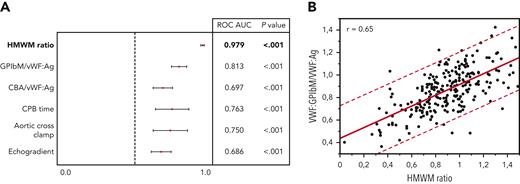

Diagnostic tools for rapid aVWS detection

Different diagnostic methods were evaluated for their accuracy in predicting aVWS based on receiver operating characteristic curve analysis (Figure 1A). Among laboratory parameters, the VWF:GPIbM/VWF:Ag ratio provided the best predictive power (AUC, 0.81 [95% CI, 0.76-0.87]) and correlated strongly (r = 0.65) with HMWM ratio (Figure 1B). In comparison, the accuracy of the VWF:CB/VWF:Ag ratio was significantly poorer (AUC, 0.70 [95% CI, 0.63-0.77]). FVIII:C (HMWM, 0.54 [95% CI, 0.46-0.62]) and VWF:Ag (AUC, 0.51 [95% CI, 0.43-0.59]) did not show relevant predictive value.

Analysis of possible aVWS predictors. (A) The VWF:GPIbM/vWF:Ag ratio shows the best predictability compared to the other investigated parameters. The HMWM ratio is presented in bold as test reference for aVWS diagnosis. (B) VWF:GPIbM/vWF:Ag ratio shows a significant correlation with HMWM. The red dashed lines represent the 95% prediction interval. Regression line: y = 0.4337093 + 0.4791361 × x.

Analysis of possible aVWS predictors. (A) The VWF:GPIbM/vWF:Ag ratio shows the best predictability compared to the other investigated parameters. The HMWM ratio is presented in bold as test reference for aVWS diagnosis. (B) VWF:GPIbM/vWF:Ag ratio shows a significant correlation with HMWM. The red dashed lines represent the 95% prediction interval. Regression line: y = 0.4337093 + 0.4791361 × x.

The predictive power of echocardiographic peak systolic gradients (AUC, 0.69 [95% CI, 0.62-0.76]) was inferior to the laboratory measurements of VWF ratios. Regarding intraoperative parameters, duration of CPB (AUC, 0.76 [0.64-0.88]) and ACC time (AUC, 0.75 [0.62-0.87]) showed reasonable values as predictors of aVWS. Intraoperative HMWM ratio values were inversely correlated with CPB time (r = −0.57) and ACC time (r = −0.54) (supplemental Figure 2).

The generally recommended cutoff value for VWF:GPIbM/VWF:Ag ratio of 0.7 provided a high specificity of 91%. However, it was associated with a poor sensitivity of 48% in our cohort and missed the intraoperative diagnosis in 17 of 24 patients (70%). We determined optimal cutoff values for VWF:GPIbM/VWF:Ag ratio with the use of the MaxSpSe method to ensure maximum sensitivity and specificity. The optimal cutoff was at 0.83, providing a sensitivity of 73% and a specificity of 71%.

Impact of aVWS on intraoperative hemorrhage

Intraoperative blood component supplementation was evaluated in our cohort according to the intraoperative aVWS status after weaning from CPB (Table 2). aVWS was associated with significantly higher substitution of FFP (59 vs 39 mL/kg; P = .016) and fibrinogen concentrate (FIB; 92 vs 48 mg/kg; P = .011) compared with that found in aVWS-negative patients. Quantities of supplemented RBC (P = .11), PLT (P = .084), factor XIII (P = .295), and prothrombin complex concentrate (P = .257) did not differ significantly according to aVWS status. The same was true for chest closure times (P = .24). Comparison of CPB duration (152 vs 81 min; P <.001) and ACC time (103 vs 51 min; P <.001) showed significantly higher values in aVWS-positive patients.

Surgery characteristics and blood component treatment according to intraoperative aVWS status

| . | aVWS negative . | aVWS positive . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (% of all) | 41 (64) | 24 (36) | NA |

| CPB time, min | 81 (26-130) | 152 (105-189) | .0004 |

| ACC time, min | 51 (22-88) | 103 (64-152) | .0008 |

| Reperfusion time, min | 11 (5-27) | 16 (11-27) | .129 |

| Minimal temperature, °C | 34.6 (32-36.8) | 34 (32-35) | .205 |

| RBC, mL/kg | 48 (0-81) | 59 (31-130) | .110 |

| FFP, mL/kg | 39 (0-76) | 59 (43-97) | .016 |

| PLT, mL/kg | 5 (0-22) | 11 (0-45) | .084 |

| FIB, mg/kg | 48 (0-96) | 92 (43-144) | .011 |

| PCC, IU/kg | 26 (0-47) | 37 (0-67) | .257 |

| Factor XIII, IU/kg | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | .295 |

| Chest closure time, min | 79 (57-111) | 79 (63-143) | .242 |

| . | aVWS negative . | aVWS positive . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (% of all) | 41 (64) | 24 (36) | NA |

| CPB time, min | 81 (26-130) | 152 (105-189) | .0004 |

| ACC time, min | 51 (22-88) | 103 (64-152) | .0008 |

| Reperfusion time, min | 11 (5-27) | 16 (11-27) | .129 |

| Minimal temperature, °C | 34.6 (32-36.8) | 34 (32-35) | .205 |

| RBC, mL/kg | 48 (0-81) | 59 (31-130) | .110 |

| FFP, mL/kg | 39 (0-76) | 59 (43-97) | .016 |

| PLT, mL/kg | 5 (0-22) | 11 (0-45) | .084 |

| FIB, mg/kg | 48 (0-96) | 92 (43-144) | .011 |

| PCC, IU/kg | 26 (0-47) | 37 (0-67) | .257 |

| Factor XIII, IU/kg | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | .295 |

| Chest closure time, min | 79 (57-111) | 79 (63-143) | .242 |

Values are presented as median (IQR) unless otherwise indicated. Significant differences are indicated in boldface.

The intraoperative incidence of aVWS was 35% in groups I and II, 10% in group III, and 50% in group IV. The intraoperative HMWM ratio was significantly higher in patients in group III (no CPB) compared with that in the other groups (P = .001).

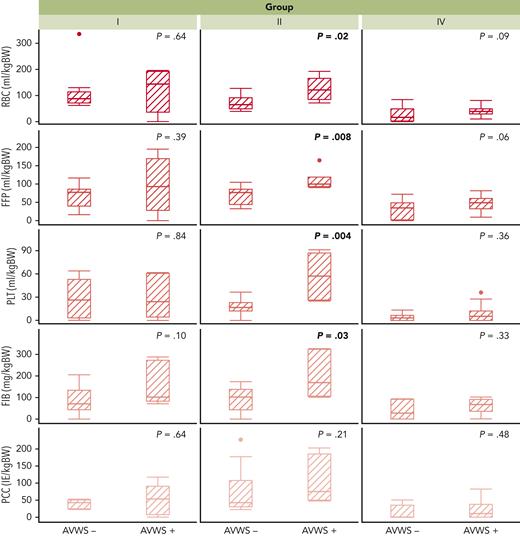

In a subgroup analysis, group II showed significant differences in supplemented quantities of FFP (P = .008), PLT (P = .004), RBC (P = .02), FIB (P = .03), and chest closure times (P = .001) according to aVWS status. In the other groups, there were no significant differences regarding these parameters. (Figure 2; supplemental Figure 3).

Intraoperative blood component supplementation according to group and aVWS status. aVWS-positive patients with complex biventricular repair (group II) received significantly higher amounts of RBC, FFP, PLT, and FIB, which could not be proved for group I and IV. Group III is not shown owing to the comparatively low requirements for blood components in non-CPB surgery. BW, body weight.

Intraoperative blood component supplementation according to group and aVWS status. aVWS-positive patients with complex biventricular repair (group II) received significantly higher amounts of RBC, FFP, PLT, and FIB, which could not be proved for group I and IV. Group III is not shown owing to the comparatively low requirements for blood components in non-CPB surgery. BW, body weight.

Comparison of intraoperative global coagulation parameters at the time of CPB weaning showed significantly higher values of fibrinogen, hemoglobin, antithrombin, FVIII:C, and VWF in patients with intraoperative aVWS compared with values in patients without aVWS (Table 3).

Intraoperative laboratory parameters according to aVWS status

| Intraoperative laboratory parameter . | aVWS negative (n = 41; 63%) . | aVWS positive (n = 24; 27%) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| aPTT, s | 45 (36-55) | 42 (34-55) | .58 |

| INR | 1.4 (1.29-1.5) | 1.32 (1.28-1.38) | .08 |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL | 173 (116-206) | 225 (194-237) | .006 |

| Platelets, ×103/μL | 140 (107-212) | 162 (115-186) | .436 |

| Hemoglobin, mg/dL | 11.4 (10.2-13.5) | 12.4 (11.6-13.6) | .026 |

| Antithrombin, % | 82 (67-101) | 105 (81-114) | .020 |

| Factor XIII, % | 101 (79-122) | 118 (90-130) | .178 |

| FVIII:C, % | 76 (63-94) | 105 (87-145) | <.001 |

| VWF:Ag, % | 123 (101-142) | 174 (146-256) | <.0001 |

| VWF:GPIbM, % | 120 (93-137) | 132 (111-150) | 0.0458 |

| VWF:GPIbM/VWF:Ag | 0.93 (0.80-1.02) | 0.74 (0.68-0.88) | 0.0002 |

| Intraoperative laboratory parameter . | aVWS negative (n = 41; 63%) . | aVWS positive (n = 24; 27%) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| aPTT, s | 45 (36-55) | 42 (34-55) | .58 |

| INR | 1.4 (1.29-1.5) | 1.32 (1.28-1.38) | .08 |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL | 173 (116-206) | 225 (194-237) | .006 |

| Platelets, ×103/μL | 140 (107-212) | 162 (115-186) | .436 |

| Hemoglobin, mg/dL | 11.4 (10.2-13.5) | 12.4 (11.6-13.6) | .026 |

| Antithrombin, % | 82 (67-101) | 105 (81-114) | .020 |

| Factor XIII, % | 101 (79-122) | 118 (90-130) | .178 |

| FVIII:C, % | 76 (63-94) | 105 (87-145) | <.001 |

| VWF:Ag, % | 123 (101-142) | 174 (146-256) | <.0001 |

| VWF:GPIbM, % | 120 (93-137) | 132 (111-150) | 0.0458 |

| VWF:GPIbM/VWF:Ag | 0.93 (0.80-1.02) | 0.74 (0.68-0.88) | 0.0002 |

Values are presented as median (IQR). Significant differences are indicated in boldface.

aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time.

aVWS dynamics over time in relation to clinical course

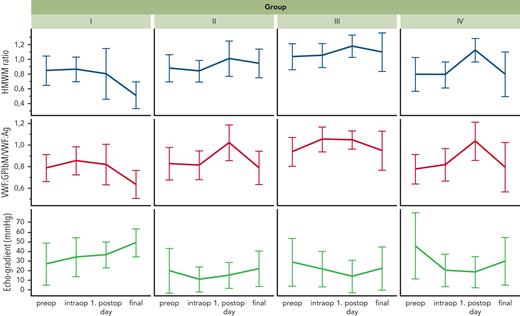

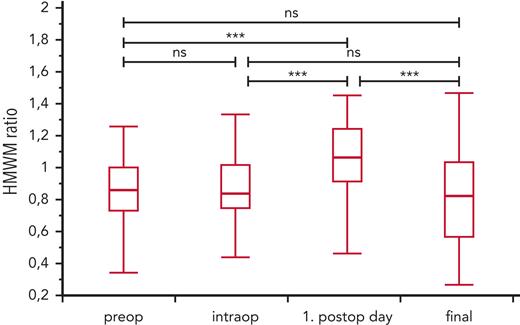

The changes in VWF:GPIbM/VWF:Ag ratio and HMWM ratio during the perioperative course were inversely related and consistent with the changes in peak systolic echocardiographic gradients for each group (Figure 3). The individual course of aVWS during the study period for each patient is shown in supplemental Figure 4. The mean values of the HMWM ratio were significantly higher on the first postoperative day than at the other 3 time points of blood sampling ( Figure 4).

Development of qualitative VWF parameters and echocardiographic peak systolic gradients over the perioperative course. The respective mean values with standard deviations at the time of blood sampling for all 3 parameters are shown. The echocardiographically determined pressure gradients are inversely related to the values for HMWM ratio and VWF:GPIbM/VWF:Ag ratio.

Development of qualitative VWF parameters and echocardiographic peak systolic gradients over the perioperative course. The respective mean values with standard deviations at the time of blood sampling for all 3 parameters are shown. The echocardiographically determined pressure gradients are inversely related to the values for HMWM ratio and VWF:GPIbM/VWF:Ag ratio.

Development of HMWM ratio (mean ± SD) over the clinical course of the entire cohort. The values of HMWM ratio were highest on the first postoperative day, supporting the thesis that the acute-phase reaction and intraoperative supplementation can lead to significant increase of HMWMs. ∗∗∗P <.0001.

Development of HMWM ratio (mean ± SD) over the clinical course of the entire cohort. The values of HMWM ratio were highest on the first postoperative day, supporting the thesis that the acute-phase reaction and intraoperative supplementation can lead to significant increase of HMWMs. ∗∗∗P <.0001.

At preoperative and intraoperative testing, 36% of patients in the entire cohort were found to have aVWS. The overall aVWS incidence was 13% on the first postoperative day and increased up to 43% at final blood sampling. In the individual groups, the aVWS incidence reached 93% in group I, 19% in group II, 20% in group III, and 40% in group IV at final blood sampling. Amounts of chest tube drainage over the first 24 postoperative hours did not differ significantly according to postoperative aVWS status (P = .45).

Nonsurgical bleeding events occurred during postoperative follow-up in 2 patients in group I (diffuse bleeding tendency during secondary chest closure and bleeding from puncture sites), 3 patients in group II (hemorrhagic tracheal aspirate, mediastinal hematoma, and pulmonary hemorrhage), and 1 patient in group IV (pulmonary hemorrhage). Thromboembolic events occurred in 1 patient in group I (partial shunt thrombosis 4 months after surgery), 1 patient in group II (transient ischemia of upper limb 4 days after surgery), and 1 patient in group III (thrombosis of the innominate vein 6 weeks after surgery). The incidence of bleeding or thrombotic events and the mortality rate did not differ significantly between aVWS-positive and aVWS-negative patients at final sampling.

Structural abnormalities associated with aVWS included mitral valve stenosis, right ventricular outflow tract obstruction, modified Blalock-Taussig shunt, pulmonary artery or valve stenosis, hemodynamically relevant PDA, and restrictive VSD. However, none of these anatomic features was invariably associated with aVWS. There were patients with very similar anatomy and yet different aVWS status. Hemodynamically insignificant small residual defects with a high-pressure gradient, such as minor residual leakages after VSD closure or residual PDAs, did not cause aVWS in our patient population. Nor did we encounter aVWS in patients with isolated coarctation of the aorta.

Discussion

According to our data, aVWS occurs frequently in neonates and infants with CHD. This is why the rapid diagnosis of aVWS is important to facilitate targeted coagulation therapy. Until now, the diagnosis of aVWS in cardiovascular disease has been challenging because of the lack of rapid tests with sufficient sensitivity.16 The presented data clearly show that aVWS diagnostics with the use of the VWF:GPIbM/VWF:Ag ratio is a promising approach, as it provided the best predictability of aVWS among all clinical and laboratory parameters. In our opinion, this newer-generation test to determine platelet-specific VWF binding26 offers a practical tool for timely intraoperative aVWS diagnosis in CHD patients. However, as suggested by Tiede et al, in-house cutoff values should be established for optimal performance of the testing strategy.27 Although providing a high specificity, the generally recommended cutoff value28 of 0.7 was associated with unacceptably low sensitivity, especially under intraoperative conditions. The optimal cutoff value for the VWF:GPIbM/VWF:Ag ratio in our cohort was determined to be 0.83. In centers where this parameter is not readily available, the knowledge that CPB and ACC durations are associated with the loss of HMWMs is crucial for empiric VWS treatment. Among the other parameters evaluated as markers for aVWS in our study, measurements of peak echocardiographic systolic gradients showed a good correlation with the HMWM ratio, demonstrating the importance of cardiac hemodynamics and shear stress in the development of aVWS. However, these gradients showed inferior predictive power compared with laboratory parameters. Especially under intraoperative conditions, the effect of CPB seems to override that of hemodynamics and valid gradient determination by echocardiography may be significantly biased owing to dynamic changes in cardiac output.

During cardiac surgery, aVWS-positive patients in our cohort had higher volumes of FFP and FIB. In the subgroup of neonates undergoing complex biventricular corrective surgery, we found that patients with intraoperative aVWS also received higher amounts of intraoperative PLT and RBC substitution and had longer chest closure times, which might be an indicator for increased bleeding tendency due to aVWS. A possible confounding effect might be due to the fact that patients with aVWS had longer CPB and ACC times, which could result in a more severe general coagulopathy in this subgroup of patients. Definitive clarification of this issue can be achieved only with prospective randomized trials evaluating the effect of VWF-containing concentrate supplementation on intraoperative bleeding. However, identification of the appropriate patient cohort that might benefit from intraoperative VWF supplementation in a prospective trial remains challenging and critical to avoid overtreatment possibly associated with thromboembolic events.29,30 Patients with transposition of the great arteries undergoing arterial switch operation might be a suitable target population, because this procedure is often complicated by significant intraoperative bleeding.

Regarding the postoperative course, the VWF values showed intense fluctuations. On the first postoperative day, HMWM ratios increased in the majority of patients, which was consistent with previous results31 and suggested that the acute-phase reaction triggered by surgery and the intraoperative supplementation of blood components contribute to overcoming aVWS. The patient’s hemodynamics become more relevant to the development of aVWS later in the course after the above effects have subsided. This is reflected by a correlation of aVWS with increasing Doppler gradients at various sites of the circulation during postoperative examination.

Preoperative and postoperative bleeding rates were low in our entire cohort and were not significantly increased in patients with aVWS. This fact supports the observation that aVWS does not contribute to excessive bleeding in the absence of open wound surface.32,33 In our cohort we found patients with similar anatomy and hemodynamics but different aVWS status, indicating possible differences of intrinsic potential to compensate shear stress–induced HMWM cleavage.

The present study has several limitations. Intraoperative bleeding intensity is difficult to quantify and could be determined by surrogate parameters only, such as the amount of supplemented blood components and chest closure times. Despite the formation of 4 subgroups, there was still considerable heterogeneity among the patients owing to different congenital heart defects and surgical procedures. The number of patients was too small to determine possible differences in intraoperative bleeding intensity according to aVWS status for “standardized” surgical procedures. Finally, we cannot exclude the possibility of potential unknown confounders that might affect the patients’ aVWS status.

In summary, the results of this study reveal a significant incidence of aVWS among neonates and infants undergoing different types of surgical procedures for palliation or correction of CHDs. Because the VWF:GPIbM/VWF:Ag ratio appears to be suitable for intraoperative monitoring, it could be included in the routine intraoperative diagnostic work-up of complex neonatal surgery on CPB. Although the effects of aVWS on intraoperative bleeding in these children are not yet clear, our data provide an important basis for optimizing intraoperative coagulation management. A possible approach could be the conduction of prospective trials evaluating the intraoperative use of VWF concentrate in specific homogeneous cohorts of patients with aVWS, such as neonates after arterial switch operations or Norwood type procedures.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sieglinde Albrecht and Heike Rathloff for their outstanding support in processing, shipping and laboratory analysis of the blood samples. They thank Walter Jost (head of clinical perfusion) for his expertise in neonatal and pediatric perfusion.

This work was supported by grants from the German Heart Foundation/German Foundation of Heart Research.

Authorship

Contribution: V.I., M.H., and C.S. designed the study; V.I. and J. Ebert collected the data; V.I. and H.M. interpreted the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; V.I., H.M., F.N., and J.M. performed the statistical analysis; J. Engel, G.W., M.K. H.M., S.S., and J. Ebert conducted the study and were responsible for patient care and blood sample collection; U.B. and K.J. analyzed and interpreted multimer analysis and other laboratory data; all authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and gave their final approval for it to be published.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests related to this manuscript.

Correspondence: Vanya Icheva, Department of Pediatric Cardiology and Intensive Care Medicine, University Children’s Hospital, Eberhard Karls University Tübingen, Hoppe-Seyler Straße 1, D-72076 Tübingen, Germany; e-mail: vanya.icheva@med.uni-tuebingen.de.

References

Author notes

For original data, please contact vanya.icheva@med.uni-tuebingen.de. Deidentified individual participant data can be obtained from the authors on reasonable request.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Comments

Comment on: “Perioperative diagnosis and impact of acquired von Willebrand syndrome in infants with congenital heart disease.”

AUTHORS: Emmanuel J Favaloro*1,2,3

1. Haematology, Institute of Clinical Pathology and Medical Research (ICPMR), Sydney Centres for Thrombosis and Haemostasis, NSW Health Pathology, Westmead Hospital, Westmead, NSW Australia.

2. School of Dentistry and Medical Sciences, Faculty of Science and Health, Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga, New South Wales, Australia

3. School of Medical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, Westmead Hospital, Westmead, New South Wales, Australia.

*Corresponding author details: Emmanuel J Favaloro, Haematology, ICPMR, Westmead, NSW, Australia 2145. Ph: +612 8890 6618; Fax: +612 9689 2331; email: Emmanuel.Favaloro@health.nsw.gov.au

Short title: Comment on VWF:GPIbM vs VWF:CB for pediatric AVWS

Manuscript type: Comment

Manuscript contains: 5 references (max 5 permitted); 0 tables/figures (max 0 tables/figures permitted).

Word count: 298 words; 300 words max permitted

Keywords: acquired von Willebrand syndrome; AVWS; VWF:GPIbM; VWF:CB.

Acknowledgements/sources of funding: No funding received. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of NSW Health Pathology or other affiliated institutions.

Conflicts of interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

ORCID: Emmanuel J. Favaloro: 0000-0002-2103-1661

To the editors,

I was interested to read the recent original study1 and accompanying Commentary2 on the perioperative diagnosis and impact of acquired von Willebrand syndrome (AVWS) in infants with congenital heart disease (CHD). The authors reported the von Willebrand factor (VWF) glycoprotein Ib M assay (GPIbM)/antigen (Ag) ratio provided the best predictability of AVWS, followed by VWF collagen binding assay (VWF:CB)/Ag ratio, based on area under the receiver operating characteristic curve data. I do not wish to denigrate these findings, and welcome any improvement in diagnosis and management of AVWS. The VWF:GPIbM is a commercial assay recently FDA approved for use in the USA; it is an excellent assay and, in my opinion, better than alternative VWF ‘activity’ assay options currently FDA approved for use in the USA. My concern is with the comparative VWF:CB assay, which was not detailed by the authors. The authors instead referred to two prior publications,3,4 the first of which3 suggested use of an in-house assay (called a laboratory developed test [LDT] in the USA) using type III collagen, and the second of which4 did not mention any VWF:CB. It is now well known that the utility of VWF:CB assays depends on collagen source and how the assay is ‘constructed’, and a wide variety of possibilities emerge regarding sensitivity (or not) to loss of high molecular weight (HMW) VWF,5 and thus AVWS due to loss of HMW VWF. So, whilst not doubting that the VWF:GPIbM/Ag ratio will enable diagnosis of AVWS in infants with CHD, whether this will ultimately always prove to better than a VWF:CB/Ag remains an open question. The authors showed the VWF:GPIbM/Ag ratio was better than ‘their’ VWF:CB/Ag, but there are possibly better VWF:CB assays available,5 and optimized VWF:CB/Ag ratios may in time prove better than the VWF:GPIbM/Ag ratio in future studies.

References:

1. Icheva V, Ebert J, Budde U, et al. Perioperative diagnosis and impact of acquired von Willebrand syndrome in infants with congenital heart disease. Blood. 2023 Jan 5;141(1):102-110.

2. O'Brien S. Acquiring a new diagnostic approach for aVWS. Blood. 2023 Jan 5;141(1):7-9.

3. Hinterleitner C, Kreisselmeier KP, Pecher AC, et al. Low plasma protein Z levels are associated with an increased risk for perioperative bleedings. Eur J Haematol. 2018;100(5):403-411.

4. Budde U, Schneppenheim R, Eikenboom J, et al. Detailed von Willebrand factor multimer analysis in patients with von Willebrand disease in the European study, Molecular and Clinical Markers for the Diagnosis and Management of Type 1 von Willebrand Disease (MCMDM-1VWD). J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(5):762-771.

5. Favaloro EJ. Commentary on the ASH ISTH NHF WFH 2021 guidelines on the diagnosis of VWD: reflections based on recent contemporary test data. Blood Adv. 2022 Jan 25;6(2):416-419.