Abstract

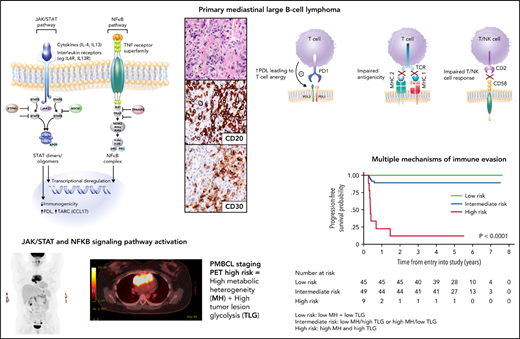

Primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL) is a separate entity in the World Health Organization’s classification, based on clinicopathologic features and a distinct molecular signature that overlaps with nodular sclerosis classic Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL). Molecular classifiers can distinguish PMBCL from diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) using ribonucleic acid derived from paraffin-embedded tissue and are integral to future studies. However, given that ∼5% of DLBCL can have a molecular PMBCL phenotype in the absence of mediastinal involvement, clinical information remains critical for diagnosis. Studies during the past 10 to 20 years have elucidated the biologic hallmarks of PMBCL that are reminiscent of cHL, including the importance of the JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways, as well as an immune evasion phenotype through multiple converging genetic aberrations. The outcome of PMBCL has improved in the modern rituximab era; however, whether there is a single standard treatment for all patients and when to integrate radiotherapy remains controversial. Regardless of the frontline therapy, refractory disease can occur in up to 10% of patients and correlates with poor outcome. With emerging data supporting the high efficacy of PD1 inhibitors in PMBCL, studies are underway that integrate them into the up-front setting.

Introduction

Primary mediastinal (thymic) large B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL) was initially defined as a subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in the Revised European American Lymphoma Classification based on unique clinicopathologic features. Subsequent molecular profiling studies highlighted a characteristic gene expression signature with striking similarities to classic Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL),1,2 and established PMBCL as a distinct entity in the World Health Organization (WHO) classification.3 Recurrent somatic gene mutations, copy number alterations, and structural variants, including those in 9p24.1 and 2p16.1,4-6 leading to JAK-STAT and NFKB constitutive pathway activation, are recognized disease hallmarks. In addition, an immune evasion phenotype predominates and is achieved through multiple converging genetic mechanisms, including structural changes at 9p24.1 leading to expression of PDL (CD274 [PDL1] and, in particular, PDCD1LG12 [PDL2]), as well as structural variants of CIITA, leading to reduced expression of major histocompatibility complex class 2 (MHC 2).7-11 Coupled with advances in the understanding of the biology of PMBCL are studies demonstrating improved outcome using rituximab chemoimmunotherapy, but still ongoing is the controversy about the optimal primary therapy and the role of consolidative radiotherapy (RT). Further, similar to cHL, a strong biological rationale for targeting the PD1-PDL pathway has led to studies evaluating PD1 inhibitors in relapsed/refractory (R/R) PMBCL, with excellent efficacy and drug approval in this setting. This review is focused on the overall unique pathogenetic features of PMBCL and provides a detailed analysis of the current treatment landscape.

Epidemiology and clinical features

PMBCL accounts for ∼2% to 4% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) and 10% of all large B-cell lymphomas. It occurs mainly in young adults with a median age of ∼35 years and has a female predominance (female/male ratio, 2:1). Patients may present with compressive symptoms caused by the anterior mediastinal mass, and thrombosis, including superior vena cava syndrome, may occur. Most patients have stage I or II disease but may have intrathoracic extension into the lung and/or chest wall or pleural/pericardial effusions.12 Extrathoracic disease can also occur in ∼10% of patients, including rare involvement of the kidney and adrenal gland,13-15 but the predominant site of disease must be in the anterior mediastinum. These sites, as well as the central nervous system (CNS), may be involved at relapse.

Pathology and molecular features of PMBCL

Pathology and immunophenotype of PMBCL

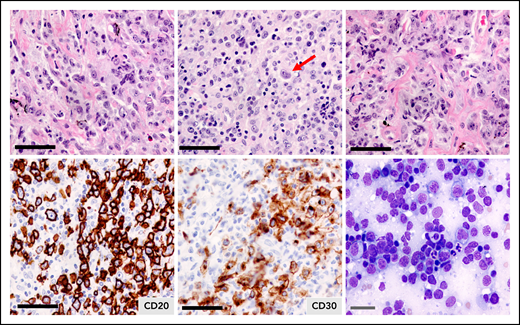

Pathologically, PMBCL is typified by a diffuse proliferation of large cells, often compartmentalized by fine bands of sclerosis (Figure 1). It can exhibit a wide morphological/cytological spectrum with variable size and shape of the neoplastic cells, and multilobated cells resembling Hodgkin Reed-Sternberg cells may be present. Of note, the diagnosis can be challenging, given the tumor location, and biopsy specimens may be small with crush artifact. With compartmentalizing fibrosis, PMBCL can mimic a carcinoma or thymoma, and adequate sampling is essential for full immunohistochemical analyses. It must also be distinguished from nodular sclerosis cHL and DLBCL with secondary mediastinal involvement. In some cases, core biopsies may not be adequate to distinguish PMBCL from the related entity, mediastinal gray zone lymphoma (MGZL), and obtaining a larger biopsy specimen is advised.

Primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Hematoxylin and eosin staining illustrating the clear cytoplasm of the neoplastic cells and the fibrotic bands without annular distribution that compartmentalize the tumor cells. Tumor cells express CD20 and most express CD30, which is weak and heterogeneous. The arrow depicts a multilobulated Hodgkin Reed Sternberg-like cell. Black bars = 50 μm; gray bar = 20 μm.

Primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Hematoxylin and eosin staining illustrating the clear cytoplasm of the neoplastic cells and the fibrotic bands without annular distribution that compartmentalize the tumor cells. Tumor cells express CD20 and most express CD30, which is weak and heterogeneous. The arrow depicts a multilobulated Hodgkin Reed Sternberg-like cell. Black bars = 50 μm; gray bar = 20 μm.

In addition to the leukocyte common antigen (CD45), the B-cell lineage antigens CD19, CD20, and CD22 are expressed (Figure 1; Table 1). However, unlike other B-cell lymphomas, PMBCL tumors often lack surface or cytoplasmic immunoglobulin, despite expression of the immunoglobulin co-receptor CD79a. CD10 and CD21 are typically negative, whereas most cases have a MUM1/IRF4+ phenotype with variable BCL6 expression.12 CD30 is positive in ∼80% of cases, but is usually weak and heterogeneous (Figure 1; Table 1), and CD15 is absent. Expression of CD200, CD23, and MAL, a lipid raft component, as well as TRAF1 and nuclear cREL, are characteristic features of PMBCL and distinguish it from DLBCL.16,17 The putative cell of origin is a thymic medullary B-cell that shares a similar phenotype, including MAL expression.18 A commercially available MAL antibody has 100% specificity in PMBCL, with expression in 72% vs 0% in DLBCL, and is superior to CD200 (specificity of 87%).19 Linked with aberrations of 9p24.1 is the expression of PDL1 (also known as B7-H1) and PDL2 in PMBCL tumors, the latter being a more specific marker for tumor cells, as PDL1 is also expressed in tumor-associated macrophages.10,20

Comparison of the clinical, pathologic, and genetic features of PMBCL and related entities

| Clinical, pathologic, and genetic features . | PMBCL . | Nonmediastinal PMBCL signature-positive DLBCL . | MGZL . | NScHL . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical and pathological features | ||||

| Female:Male | 2:1 | 1:1 | 1:3 | 1:1 |

| Median age (y) | ∼35 | ∼66 | ∼34-40 | ∼28 |

| Stages I and II, % | 70-80 | 56 | 65 | 55 |

| Mediastinal presentation, % | All | None | 100 | 80 |

| Bone marrow, % | Rare | 19 | Rare | Rare |

| Bulky disease (≥10 cm), % | 70-80 | 6 | 30 | 54 |

| Morphology | Sheets of large cells; clear cells; no inflammatory polymorphous infiltrate | Similar to DLBCL | Broad cytologic appearance; may resemble PMBCL (25%); cHL (25%); intermediate (45%); composite (5%) | Lacunar Hodgkin Reed-Sternberg cells; inflammatory polymorphous infiltrate |

| Sclerosis, % | 70-100 (alveolar, fine bands) | Negative | Variable | 100 (large bands, annular) |

| 5-year OS, % | ∼90-97 | 72 (2-year DSS)* | ∼75 | ∼85 |

| Immunohistochemistry, % | ||||

| CD45 | 100 | Not reported | Positive | Negative |

| CD30 | 70-85 (weak) | 31 (weak) | ∼85-100 (strong) | 100 |

| CD15 | Negative | Negative | 58-80 | 75-85 |

| CD20 CD79a PAX-5 MUM1 | 100 100 100 75 | 100 Not reported* Not reported 19 | ∼72-98 (weak) 67-75 98 Positive | Very rare (minority) Very rare 95 (weak) 100 |

| MAL CD23 | 60-70 85 | 57 71 | 30-49* 30-49 | 19 Negative |

| TRAF1 expression Nuclear cRel | 60-70 60-70 | Not reported Not reported | Usually positive Not reported | 84 92 |

| PDL1 PDL2 | 71 72 | 19 14 | ∼80 ∼30 | 87 |

| Genetic aberrations, % | ||||

| CIITA rearrangements 9p.24.1 aberrations (JAK2, PDL) 2p16.1 (Rel, BCL11A) SOCS1 mutation/deletion B2M mutations | 38 70 25-50 35-45 30-64 | Negative 33 Frequent 100 ∼15 | 30-37 60 33 40 32 | 15 25-30 25 42 40 |

| Clinical, pathologic, and genetic features . | PMBCL . | Nonmediastinal PMBCL signature-positive DLBCL . | MGZL . | NScHL . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical and pathological features | ||||

| Female:Male | 2:1 | 1:1 | 1:3 | 1:1 |

| Median age (y) | ∼35 | ∼66 | ∼34-40 | ∼28 |

| Stages I and II, % | 70-80 | 56 | 65 | 55 |

| Mediastinal presentation, % | All | None | 100 | 80 |

| Bone marrow, % | Rare | 19 | Rare | Rare |

| Bulky disease (≥10 cm), % | 70-80 | 6 | 30 | 54 |

| Morphology | Sheets of large cells; clear cells; no inflammatory polymorphous infiltrate | Similar to DLBCL | Broad cytologic appearance; may resemble PMBCL (25%); cHL (25%); intermediate (45%); composite (5%) | Lacunar Hodgkin Reed-Sternberg cells; inflammatory polymorphous infiltrate |

| Sclerosis, % | 70-100 (alveolar, fine bands) | Negative | Variable | 100 (large bands, annular) |

| 5-year OS, % | ∼90-97 | 72 (2-year DSS)* | ∼75 | ∼85 |

| Immunohistochemistry, % | ||||

| CD45 | 100 | Not reported | Positive | Negative |

| CD30 | 70-85 (weak) | 31 (weak) | ∼85-100 (strong) | 100 |

| CD15 | Negative | Negative | 58-80 | 75-85 |

| CD20 CD79a PAX-5 MUM1 | 100 100 100 75 | 100 Not reported* Not reported 19 | ∼72-98 (weak) 67-75 98 Positive | Very rare (minority) Very rare 95 (weak) 100 |

| MAL CD23 | 60-70 85 | 57 71 | 30-49* 30-49 | 19 Negative |

| TRAF1 expression Nuclear cRel | 60-70 60-70 | Not reported Not reported | Usually positive Not reported | 84 92 |

| PDL1 PDL2 | 71 72 | 19 14 | ∼80 ∼30 | 87 |

| Genetic aberrations, % | ||||

| CIITA rearrangements 9p.24.1 aberrations (JAK2, PDL) 2p16.1 (Rel, BCL11A) SOCS1 mutation/deletion B2M mutations | 38 70 25-50 35-45 30-64 | Negative 33 Frequent 100 ∼15 | 30-37 60 33 40 32 | 15 25-30 25 42 40 |

MGZL, B-cell lymphoma unclassifiable with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and classic Hodgkin lymphoma. Estimates for MGZL (vs non-MGZL) are reported where possible.12,20,21,23,42,90-92 Frequencies are provided when available; immunohistochemistry frequencies may vary depending on the thresholds used. For GZL, frequencies vary for cHL-like and large B-cell lymphoma subtypes (eg, MAL and CD23 expression are higher in large B-cell lymphoma type GZL).

NScHL, nodular sclerosing cHL.

As a subtype of DLBCL, CD79a, and PAX5 would be expected to show frequencies of 100%. The survival estimate is based on only 16 cases and requires validation.

Of note, GZL is defined in the WHO classification as B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between DLBCL and cHL. Approximately 60% to 70% of cases have mediastinal involvement (MGZL), and a diagnosis of MGZL is made if a tumor has overlapping genotypic and/or phenotypic features of cHL and PMBCL21,22 (Table 1).

Molecular signature of PMBCL

Clinical and pathological similarities between PMBCL and nodular sclerosis cHL have long been appreciated, and their pathogenetic relatedness was further supported by two gene expression–profiling studies that demonstrated striking similarities in their molecular signatures. Genes overexpressed in PMBCL included those involved in the JAK-STAT pathway (IL13RA, JAK2, and STAT1), as well as key components of NF-κB activation (TRAF1 and TFNAIP3), but expression of genes involved in B-cell receptor signaling were decreased.1,2 Interestingly, MGZL (PMBCL-like) has an intermediate gene expression profile between PMBCL and cHL, but a notably strong macrophage signature and downregulation of the B-cell program, which may be linked to poorer outcome.22,23

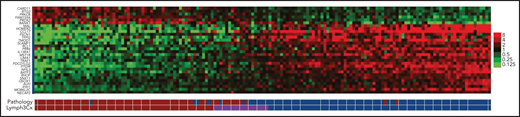

In practice, PMBCL is a clinicopathologic diagnosis that has inherent subjectivity. Integration of a robust PMBCL molecular classifier into routine diagnostics may guide therapy and would facilitate study comparison. Investigators from the Lymphoma/Leukemia Molecular Profiling Project used formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue from primary biopsies of PMBCL tumors to develop the Lymph3Cx Nanostring assay, incorporating genes to determine the DLBCL cell of origin24 along with a 30-gene PMBCL molecular classifier, with 24 genes overexpressed in PMBCL and 6 genes overexpressed in DLBCL (Figure 2).25 More recently, an expanded Nanostring-based assay, DLBCL90, combines previous DLBCL Nanostring assays (Lymph3Cx and the double-hit signature),26 as well as the reverse transcriptase multiplex ligation–dependent probe amplification classifier assay similarly distinguish DLBCL by cell of origin and PMBCL27; both have the potential to translate molecular classification into routine practice in PMBCL.

Heat map of gene expression comparing PMBCL and DLBCL. Each column represents a case, and the discriminating gene features included in Lymph3Cx assay are in rows. The top 6 genes are overexpressed in DLBCL, and the remaining 24 genes show higher expression in PMBCL. Modified from Mottok et al.25

Heat map of gene expression comparing PMBCL and DLBCL. Each column represents a case, and the discriminating gene features included in Lymph3Cx assay are in rows. The top 6 genes are overexpressed in DLBCL, and the remaining 24 genes show higher expression in PMBCL. Modified from Mottok et al.25

Genomic landscape and pathogenic hallmarks of PMBCL

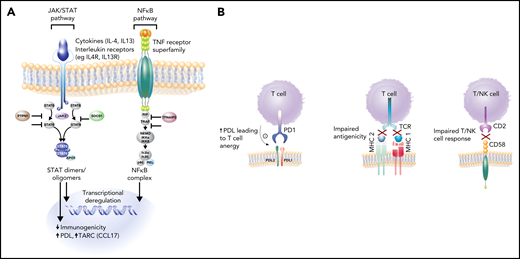

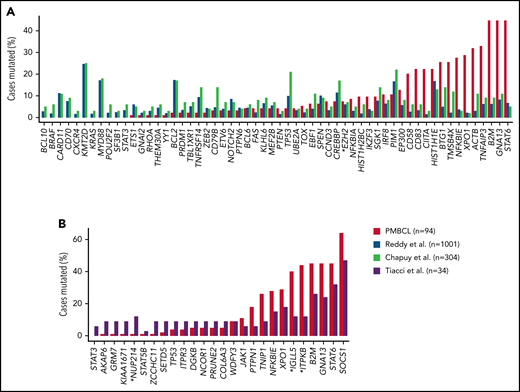

Molecular hallmarks of PMBCL include constitutive activation of the JAK-STAT and NF-κB pathways and genetic aberrations that lead to a phenotype of immune evasion, all shared features with cHL (Figure 3A-B). Mechanisms of NF-κB activation include copy number gains of REL (on 2p16.1) and inactivating mutations of negative regulators of NF-κB, including TNFAIP3 and NFKBIE.5,28,29 JAK-STAT pathway activation is achieved through multiple mechanisms, including paracrine activation by interleukin 13 (IL13) receptor–mediated signaling, constitutive activation through loss-of-function mutations in SOCS-1 (suppressor of cytokine signaling) and PTPN1 (protein tyrosine phosphatase), and gain-of-function mutations in STAT6 and IL4R.30-33 Mutations in these genes co-occur in ∼63% of cases, supporting an additive or synergistic cooperation.30 These findings were echoed in two integrative whole-genome sequencing studies where, in comparison with DLBCL,34,35 distinct recurrent genetic alterations emerged in PMBCL including, as expected, genes affected in the NF-κB and JAK-STAT signaling pathways, SOCS1, NFKBIE, and XPO1 (exportin 1)34 (Figure 4). Many of the involved genes were implicated as oncogenic drivers (eg, IL4R) and have also been observed in cHL34,35 (Figure 4).

Key pathogenic hallmarks of PMBCL and pathway perturbation. (A) JAK-STAT and NFκB are key activation pathways in PMBCL leading to transcriptional deregulation and impaired immunogenicity. (B) Mechanisms of immune evasion in PMBCL, including PDL1/2 expression with resultant T-cell anergy, reduced antigenicity through MHC class 2 downregulation (in part, due to CIITA rearrangements and mutations), MHC class 1 defects caused by B2M mutations, and CD58 mutations/microdeletions leading to impaired T- and NK-cell interactions.8,32,35

Key pathogenic hallmarks of PMBCL and pathway perturbation. (A) JAK-STAT and NFκB are key activation pathways in PMBCL leading to transcriptional deregulation and impaired immunogenicity. (B) Mechanisms of immune evasion in PMBCL, including PDL1/2 expression with resultant T-cell anergy, reduced antigenicity through MHC class 2 downregulation (in part, due to CIITA rearrangements and mutations), MHC class 1 defects caused by B2M mutations, and CD58 mutations/microdeletions leading to impaired T- and NK-cell interactions.8,32,35

Comparison of mutational frequencies between DLBCL, PMBCL, and cHL. (A) Comparison of mutation frequencies for putative PMBCL driver genes identified in Mottok et al34 and compared with DLBCL (Reddy et al42 and Chapuy et al43). EZH2(*) is the only gene with no significant difference in mutational frequency. (B) Mutational frequencies of PMBCL compared with cHL (Tiacci et al44). Mutational frequencies are comparable for most genes. Statistically different mutation frequencies are identified by an asterisk. Modified and reproduced from Mottok et al34 and, with permission, from Chapuy et al.43

Comparison of mutational frequencies between DLBCL, PMBCL, and cHL. (A) Comparison of mutation frequencies for putative PMBCL driver genes identified in Mottok et al34 and compared with DLBCL (Reddy et al42 and Chapuy et al43). EZH2(*) is the only gene with no significant difference in mutational frequency. (B) Mutational frequencies of PMBCL compared with cHL (Tiacci et al44). Mutational frequencies are comparable for most genes. Statistically different mutation frequencies are identified by an asterisk. Modified and reproduced from Mottok et al34 and, with permission, from Chapuy et al.43

These and other studies have also illuminated a diverse array of mechanisms that contribute to the immune escape phenotype of PMBCL. CD274 (PDL1) and PDCD1LG2 (PDL2) are concurrently amplified with JAK2 at 9p24.1, leading to PDL1/2 expression and the resultant T-cell anergy10,36,37 (Figure 3B). Interestingly, STAT-dependent expression of PDL1 has also been identified, supporting the notion of cooperation between these pathways31 (Figure 3A).

Impaired antigen presentation through MHC defects also contributes to the immune-privileged phenotype in PMBCL (Figure 3B). Similar to cHL, downregulation of MHC Class 2 molecules is associated with inferior outcome in PMBCL9 and is linked to genetic aberrations at the CIITA (an MHC Class 2 master transcriptional regulator) locus,8 which in composite, occur in ∼70% of PMBCL cases.38 Mutations in β-2-microglobulin (B2M) are prominent in PMBCL and cHL and lead to impaired MHC class 1–mediated antigen presentation (Figure 3B). Similarly, CD58 mutations, a shared feature with cHL39 and DLBCL,40 are thought to impair interactions with NK and T cells. Mutations in immune response (IRF) genes, including a hotspot mutation IRF4, as well as mutations in downstream targets collectively occur in more than half of PMBCL cases and affect antigen presentation, as well as T-cell, NK-cell, and macrophage responses.34

DLBCL with a PMBCL-like signature

Rarely, DLBCL cases with a non-mediastinal location can have a molecular signature reminiscent of PMBCL.41 In a recent study, 5.8% of DLBCL cases had a molecular signature of PMBCL in the absence of mediastinal involvement.42 In comparison with bona fide PMBCL, these patients were older (median age, 66 years), with equal sex predominance, but MAL (57%) and CD23 (71%) protein expression were frequent. although CD30 was positive in only 17% of the patients42 (Table 1). Similar to PMBCL, aberrations in genes involving JAK-STAT signaling were common, including, SOCS1 mutations in all cases, and frequent mutations in STAT6, IL4R, and DUSP2 as well as copy number alterations at 9p24.1 with resultant transcript levels in affected genes (eg, PDL1/2, JAK2) was observed. Mutations in genes involved in the immune response were also found (eg, CD8, HLA-A, and HLA-C), and the IL4R mutation location was different from those found in bona fide PMBCL, suggesting alternate mechanisms leading to an immune evasion phenotype.42 Two key studies of DLBCL have defined a new classification that integrates genetic features.43-45 Cluster 4 defined by Chapuy and colleagues, includes recurrent mutations similar to those of non-mediastinal PMBCL signature-positive tumors, except that SOCS1 mutations were not reported, as they did not pass MutsigCV filtering thresholds.43 Lacy and colleagues applied targeted sequencing to define a SOCS/SGK1 DLBCL molecular group that also shared a similar mutation profile, providing further evidence that non-mediastinal PMBCL signature-positive tumors represent a true entity with unique biology, which may have therapeutic implications.46

Management of PMBCL

Frontline therapy in PMBCL

There are no randomized controlled studies defining the optimal frontline treatment for PMBCL, and as a result, international guidelines vary (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site). Data are largely derived from non-randomized prospective and retrospective studies, both of which can be subject to selection bias. An acute presentation may necessitate urgent chemotherapy, which may preclude trial enrollment, whereas retrospective studies rely on comprehensive inclusion as well as center diagnosis and may be affected by diverse treatment approaches. Given that PMBCL is a clinicopathologic diagnosis, diagnostic certainty may affect study comparisons, and to date, there have been few studies that applied gold-standard molecular diagnostics. Regardless, because patients often are younger, balancing cure and the potential for long-term toxicities, such as secondary malignancies and cardiovascular complications, are important treatment considerations in PMBCL.

Most studies support the notion that the addition of rituximab to CHOP/CHOP-like (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) chemotherapy adds a magnitude of benefit similar to that shown in DLBCL.47-50 This was not as clear in a study evaluating R-MACOPB (methotrexate, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, prednisolone, and bleomycin with rituximab) or R-VACOPB (etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone, bleomycin with rituximab), with 69% receiving RT, where historical comparisons to V/MACOPB+RT appeared similar51 (Table 2). In a separate study, there was a trend toward improved progression-free survival (PFS; P = .06) of R-VACOPB over VACOPB but no difference in overall survival (P = .2). In addition, PFS with R-VACOPB was similar to that with CHOP+rituximab (R-CHOP; P = .3)52 (Table 2), suggesting that rituximab may somewhat negate the benefit of dose intensity. None of these studies are definitive, given the small number of patients enrolled. Taking all study results together, R-CHOP or R-CHOP-like therapy yields a 2-year PFS of ∼80% and a 2-year OS of ∼90% in most of the analyses; however, the majority of studies have also incorporated routine mediastinal RT, particularly if CHOP was used (Table 2), which may have long-term secondary complications.

Prospective and retrospective studies evaluating R-CHOP(like) and DA-EPOCHR chemotherapy in PMBCL

| PMBCL studies R-chemotherapy . | Study size, n; Median age, y (range) . | Study type . | PFS/EFS, % (y) . | OS, % (y) . | % RT . | Treatment comparison/study comment . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective | ||||||

| R-CHOP14/ICE±R (MSKCC 01-142) Moskowitz et al (abstract), 201093 | 54 34 (19-59) | Prospective + per protocol | 78 (3) | 88 (3) | 0 | First 28 patients treated during the study and 26 treated per protocol.* Planned switch to ICE. |

| R-CHOP/R-CHOEP (MINT study group), Rieger et al, 201149† | 44 36 (27-43) | Prospective subgroup | 78 (3) | 89 (3) | 73 | R-CHO(E)P vs CHO(E)P EFS P = .012 OS P = .158 0 or 1 aaIPI factor* |

| DA-EPOCHR (NCI) DA-EPOCHR (Stanford) Dunleavy et al, 201354 | 51 30 (23-51) 16 33 (23-68) | Prospective Retrospective | 93 (5) 100 | 97 (5) 100 | 4 0 | Subset with PMBCL within phase 2 study of aggressive BCLs.* Series of PMBCL treated with DA-EPOCHR at Stanford 2007-12 reported with phase 2 study. |

| R-MACOPB/R-VACOPB (84%) or R-CHOP IELSG-26 Martelli et al, 201468 | 125 33 (range, NR) | Prospective observational | 86 (5) | 92 (5) | 92 | Purpose was to evaluate CR by Deauville criteria.* |

| R-CHOP14/21 (NCI) Gleeson et al, 201694‡ | 50 38.5 (22-78) | Prospective subgroup | 80 (5) | 84 (5) | 58 | R-CHOP21 vs R-CHOP14 PFS P = .10; OS P = .06 Unadjusted analysis* |

| DA-EPOCH-R (pediatric) Burke et al, 202195 | 47 15 (range NR) | Prospective | 69 (2) | 82 (2) | 0 | No patients received consolidative RT.* |

| R-CHOP21/14 (UNFOLDER trial) Held et al (abstract), 202096§ | 131 34 (range NR) | Prospective subgroup | 93 (3) | 97 (3) | 62.5 | R-CHOP21 vs R-CHOP14 (no difference) Pooled 3-y event rates;* RT did not impact PFS (P = .25). |

| Retrospective | ||||||

| R-V/MACOPB Zinzani et al, 200951 | 45 38 (17-66) | Retrospective | 84 (5) | 80 (5) | 71 | No difference in R-V/MACOPB vs historical estimates without R.* |

| R-CHOP Ahn et al, 201097 | 21 30 (17-79) | Retrospective | 79 (2) | 83 (2) | 62 | R-CHOP vs CHOP PFS P = .043 OS P = .08 |

| R-CHOP Vassilakopoulos et al, 201248 | 76 31.5 (17-73) | Retrospective | 81 (5) | 89 (5) | 76 | R-CHOP vs CHOP FFP P < .0001 OS P = .003 Early treatment failure (<6 m), 9%* |

| R-CHOP Xu et al, 201350 | 39 29 (13-54) | Retrospective | 77 (5) | 84 (5) | 76 | R-CHOP vs CHOP PFS P = .012 OS P = .011 |

| R-CHOP Aoki et al, 201415ǁ | 187 31.5 (17-77) | Retrospective | 71 (4) | 90 (4) | 34 | R-chemo all vs CHOP PFS P = .001 OS P = .001 DA-EPOCHR; 2nd/3rd generation HDC/SCT (vs R-CHOP no difference) Treatment selection criteria unknown.* |

| R-CHOP Soumerai et al, 201498 | 63 37 (20-82) | Retrospective | 68 (5) | 79 (5) | 77 | PD during R-CHOP 18%* Male predominance (60%)* |

| R-VACOPB Avigdor et al, 201452 | 40 33 (range NR) | Retrospective | 83 (5) | NR | 0 | R-VACOPB vs VACOPB PFS P = .06 OS P = .2 R-VACOPB vs R-CHOP P = .3 |

| R-MACOPB Zinzani et al, 201566 | 74 34 (18-63) | Retrospective | 88 (10) | 82 (10) | 69 | RT vs no RT P = .85 RT only in PET-positive (IHP).* |

| R-CHOP DA-EPOCHR Pinnix et al, 201599¶ | 50 35 (19-70) 25 | Retrospective | ∼90 (estimate) 83 | NR NR | 90 20 | R-CHOP vs DA-EPOCHR (and R-HCVAD) PFS P = .35 Treatment selection criteria unknown.* |

| R-CHOP-RICE Goldschmidt et al, 2016100 | 24 34 (18-60) | Retrospective | 87 (5) | 100 (5) | 12 | R-CHOP-RICE vs other protocols, R CHOP/R-M/ VACOPB/DA-EPOCHR PFS P = .35 OS P = .31 78% other protocols received RT.* |

| R-CHOP/R-CHOEP Lisenko et al, 201747 | 45 38 (19-64) | Retrospective | 95 | 92 | 91 | R-CHO(E)P vs CHOP PFS P = .001 OS P = .023 |

| DA-EPOCH-R (Adult) DA-EPOCHR (Pediatric) Giulino-Roth et al, 201714 | 118 34 (21-70) 38 16 (9-20) | Retrospective | 87 (3) 81 (3) | 97 (3) 91 (3) | 16 11 | Adult vs pediatric; EFS P = .34 |

| R-CHOP DA-EPOCHR Shah et al, 201858 | 56 37 (20-77) 76 34 (18-69) | Retrospective | 76 (2) 85 (2) | 89 (2) 91 (2) | 59 13 | R-CHOP vs DA-EPOCHR PFS P = .28 OS P = .83 Treatment selection criteria unknown.* |

| R-CHOP Malenda et al, 202059 | 25 37 (18-80) | Retrospective | 87 (1) | 100 (1) | 25 | R-CHOP vs DA-EPOCHR PFS P = .20 OS P = .66 Treatment selection criteria unknown.* |

| R-CHOP R-CHOP + RT Messmer et al, 2019101 | 16 36 (23-52) 10 40.5 (19-60) | Retrospective | 93 (3) 100 (3) | 100 (3) 100 (3) | 0 100 | RT vs no RT P = .85 RT criteria unknown.* |

| R-CHOP R-CHOP + RT DA-EPOCHR Chan et al, 2019102 | 41 28 (11-72) 37 26 (14-48) 46 27 (16-51) | Retrospective | 56.5(5) 88 (5) 90 (5) | 76 (5) 94 (5) 94 (5) | 0 100 6 | R-CHOP vs DA-EPOCHR PFS P = .012 OS P = .01 RT vs no RT with R-CHOP PFS P = .04 Treatment selection criteria unknown.* |

| R-CHOP Zhou et al, 202057# | 89 33 (11-64) | Retrospective | ∼60 (5) estimate | ∼70 (5) estimate | 84 (5) | R-CHOP vs DA-EPOCHR/R-HCVAD PFS P = .048 OS P = .0067 Treatement selection criteria unknown.* |

| R-CHOP Hayden et al, 202013 | 159 36 (19-84) | Retrospective | 80 (5) | 89 (5) | 28 | PET-guided use of consolidative RT (no difference in outcome vs routine RT).* |

| R-CHOP14/21 R-CHOEP14 Wästerlid et al, 2021103** | 17 49 (18-83) 90 35 (18-74) | Registry | NR | 74 (5) RS 95 (5) RS | 14 18 | R-CHOEP14/R-HyperCVAD/DA-EPOCHR Treatment selection criteria unknown (not formally compared)* |

| PMBCL studies R-chemotherapy . | Study size, n; Median age, y (range) . | Study type . | PFS/EFS, % (y) . | OS, % (y) . | % RT . | Treatment comparison/study comment . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective | ||||||

| R-CHOP14/ICE±R (MSKCC 01-142) Moskowitz et al (abstract), 201093 | 54 34 (19-59) | Prospective + per protocol | 78 (3) | 88 (3) | 0 | First 28 patients treated during the study and 26 treated per protocol.* Planned switch to ICE. |

| R-CHOP/R-CHOEP (MINT study group), Rieger et al, 201149† | 44 36 (27-43) | Prospective subgroup | 78 (3) | 89 (3) | 73 | R-CHO(E)P vs CHO(E)P EFS P = .012 OS P = .158 0 or 1 aaIPI factor* |

| DA-EPOCHR (NCI) DA-EPOCHR (Stanford) Dunleavy et al, 201354 | 51 30 (23-51) 16 33 (23-68) | Prospective Retrospective | 93 (5) 100 | 97 (5) 100 | 4 0 | Subset with PMBCL within phase 2 study of aggressive BCLs.* Series of PMBCL treated with DA-EPOCHR at Stanford 2007-12 reported with phase 2 study. |

| R-MACOPB/R-VACOPB (84%) or R-CHOP IELSG-26 Martelli et al, 201468 | 125 33 (range, NR) | Prospective observational | 86 (5) | 92 (5) | 92 | Purpose was to evaluate CR by Deauville criteria.* |

| R-CHOP14/21 (NCI) Gleeson et al, 201694‡ | 50 38.5 (22-78) | Prospective subgroup | 80 (5) | 84 (5) | 58 | R-CHOP21 vs R-CHOP14 PFS P = .10; OS P = .06 Unadjusted analysis* |

| DA-EPOCH-R (pediatric) Burke et al, 202195 | 47 15 (range NR) | Prospective | 69 (2) | 82 (2) | 0 | No patients received consolidative RT.* |

| R-CHOP21/14 (UNFOLDER trial) Held et al (abstract), 202096§ | 131 34 (range NR) | Prospective subgroup | 93 (3) | 97 (3) | 62.5 | R-CHOP21 vs R-CHOP14 (no difference) Pooled 3-y event rates;* RT did not impact PFS (P = .25). |

| Retrospective | ||||||

| R-V/MACOPB Zinzani et al, 200951 | 45 38 (17-66) | Retrospective | 84 (5) | 80 (5) | 71 | No difference in R-V/MACOPB vs historical estimates without R.* |

| R-CHOP Ahn et al, 201097 | 21 30 (17-79) | Retrospective | 79 (2) | 83 (2) | 62 | R-CHOP vs CHOP PFS P = .043 OS P = .08 |

| R-CHOP Vassilakopoulos et al, 201248 | 76 31.5 (17-73) | Retrospective | 81 (5) | 89 (5) | 76 | R-CHOP vs CHOP FFP P < .0001 OS P = .003 Early treatment failure (<6 m), 9%* |

| R-CHOP Xu et al, 201350 | 39 29 (13-54) | Retrospective | 77 (5) | 84 (5) | 76 | R-CHOP vs CHOP PFS P = .012 OS P = .011 |

| R-CHOP Aoki et al, 201415ǁ | 187 31.5 (17-77) | Retrospective | 71 (4) | 90 (4) | 34 | R-chemo all vs CHOP PFS P = .001 OS P = .001 DA-EPOCHR; 2nd/3rd generation HDC/SCT (vs R-CHOP no difference) Treatment selection criteria unknown.* |

| R-CHOP Soumerai et al, 201498 | 63 37 (20-82) | Retrospective | 68 (5) | 79 (5) | 77 | PD during R-CHOP 18%* Male predominance (60%)* |

| R-VACOPB Avigdor et al, 201452 | 40 33 (range NR) | Retrospective | 83 (5) | NR | 0 | R-VACOPB vs VACOPB PFS P = .06 OS P = .2 R-VACOPB vs R-CHOP P = .3 |

| R-MACOPB Zinzani et al, 201566 | 74 34 (18-63) | Retrospective | 88 (10) | 82 (10) | 69 | RT vs no RT P = .85 RT only in PET-positive (IHP).* |

| R-CHOP DA-EPOCHR Pinnix et al, 201599¶ | 50 35 (19-70) 25 | Retrospective | ∼90 (estimate) 83 | NR NR | 90 20 | R-CHOP vs DA-EPOCHR (and R-HCVAD) PFS P = .35 Treatment selection criteria unknown.* |

| R-CHOP-RICE Goldschmidt et al, 2016100 | 24 34 (18-60) | Retrospective | 87 (5) | 100 (5) | 12 | R-CHOP-RICE vs other protocols, R CHOP/R-M/ VACOPB/DA-EPOCHR PFS P = .35 OS P = .31 78% other protocols received RT.* |

| R-CHOP/R-CHOEP Lisenko et al, 201747 | 45 38 (19-64) | Retrospective | 95 | 92 | 91 | R-CHO(E)P vs CHOP PFS P = .001 OS P = .023 |

| DA-EPOCH-R (Adult) DA-EPOCHR (Pediatric) Giulino-Roth et al, 201714 | 118 34 (21-70) 38 16 (9-20) | Retrospective | 87 (3) 81 (3) | 97 (3) 91 (3) | 16 11 | Adult vs pediatric; EFS P = .34 |

| R-CHOP DA-EPOCHR Shah et al, 201858 | 56 37 (20-77) 76 34 (18-69) | Retrospective | 76 (2) 85 (2) | 89 (2) 91 (2) | 59 13 | R-CHOP vs DA-EPOCHR PFS P = .28 OS P = .83 Treatment selection criteria unknown.* |

| R-CHOP Malenda et al, 202059 | 25 37 (18-80) | Retrospective | 87 (1) | 100 (1) | 25 | R-CHOP vs DA-EPOCHR PFS P = .20 OS P = .66 Treatment selection criteria unknown.* |

| R-CHOP R-CHOP + RT Messmer et al, 2019101 | 16 36 (23-52) 10 40.5 (19-60) | Retrospective | 93 (3) 100 (3) | 100 (3) 100 (3) | 0 100 | RT vs no RT P = .85 RT criteria unknown.* |

| R-CHOP R-CHOP + RT DA-EPOCHR Chan et al, 2019102 | 41 28 (11-72) 37 26 (14-48) 46 27 (16-51) | Retrospective | 56.5(5) 88 (5) 90 (5) | 76 (5) 94 (5) 94 (5) | 0 100 6 | R-CHOP vs DA-EPOCHR PFS P = .012 OS P = .01 RT vs no RT with R-CHOP PFS P = .04 Treatment selection criteria unknown.* |

| R-CHOP Zhou et al, 202057# | 89 33 (11-64) | Retrospective | ∼60 (5) estimate | ∼70 (5) estimate | 84 (5) | R-CHOP vs DA-EPOCHR/R-HCVAD PFS P = .048 OS P = .0067 Treatement selection criteria unknown.* |

| R-CHOP Hayden et al, 202013 | 159 36 (19-84) | Retrospective | 80 (5) | 89 (5) | 28 | PET-guided use of consolidative RT (no difference in outcome vs routine RT).* |

| R-CHOP14/21 R-CHOEP14 Wästerlid et al, 2021103** | 17 49 (18-83) 90 35 (18-74) | Registry | NR | 74 (5) RS 95 (5) RS | 14 18 | R-CHOEP14/R-HyperCVAD/DA-EPOCHR Treatment selection criteria unknown (not formally compared)* |

Estimates are rounded; complete remission.

aaIPI, age-adjusted International Prognostic Index; CVAD, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone; HCVAD hyper-CVAD; ICE, ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide; IHP International Harmonization Project; NCI, National Cancer Institute; NR not reported; RS, relative survival; Tx, treatment.

Comment on treatment comparison.

R-CHOP (n=21), RCHOEP (n=23), RCHOP/RCHOEP (n=1).

Median age for all patients.

Abstract only; P-values not provided.

The study included 345 patients (CHOP [n = 47]; R-CHOP [n = 187]; DA-EPOCHR [n = 9]; second/third generation [n = 45]; high-dose chemotherapy/ASCT [n = 57]).

Median age for all patients; outcome for cohort: 5-year PFS 91%, 5-year OS 99%; PFS estimated for R-CHOP.

Median age for all patients; 19 patients were treated with HCVAD (vs R-CHOP PFS, P = .0088; OS, P = .095).

R-CHOP (n = 3); R-CHOP14 (n = 14); not shown DA-EPOCHR (n = 11); 5-year RS, 82%; R-HCVAD (n = 16), 5-year RS 100%.

DA-EPOCHR (dose-adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, rituximab) was developed for aggressive lymphomas to overcome drug resistance and integrates three important modifications over R-CHOP: (1) the addition of etoposide with added activity and synergy; (2) continuous infusion of etoposide, vincristine, and doxorubicin, with in vitro data supporting less drug resistance; and (3) individualized dose adjustment based on the previous cycle neutrophil nadir with growth factor support.53 The subset of 51 patients classified as PMBCL enrolled in the phase 2 National Cancer Institute (NCI) study of DA-EPOCHR in aggressive lymphomas, demonstrated excellent outcomes, with a 5-year event-free survival (EFS) of 93% and OS of 97%, with only 2 patients receiving consolidative RT (Table 2).54 In the same report, a retrospective series of 16 PMBCL patients from Stanford treated with DA-EPOCHR was included, and with a median follow-up of 37 months, all patients were alive and event free.54 In the largest retrospective series of DA-EPOCHR treated PMBCL patients, Guilino-Roth et al evaluated156 patients, most of whom were adults (n = 118)14 (Table 1). For all patients, the 3-year EFS was 86%, and OS was 95%. Considering only adult patients (≥21 years, with a median age of 34 years [range, 21-70]), the 5-year EFS was 87.4%, and the OS was 97%, with 16% having received mediastinal RT. Pediatric patients had a 3-year EFS of 81% and 91% (vs adult patients, P = .34) but were more likely to have dose escalation to at least level 4 (54% vs 33%; P = .03). The authors concluded that DA-EPOCHR is a reasonable approach for PMBCL of all ages. In contrast, in a phase 2 of the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) and European Intergroup for Childhood Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma of 46 pediatric/adolescent patients with PMBCL (median age, 15.4 years) were treated with DA-EPOCHR and demonstrated a 2-year EFS of 69.6% and OS of 82%,55 with 48% advancing to at least dose level 4. In addition, 41% received pre-phase COP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisolone) 1 week before the study.55 The recently reported CALGB 50303 phase 3 study comparing DA-EPOCHR to R-CHOP as a frontline therapy for DLBCL, including morphologic subtypes and PMBCL, failed to show a benefit of the intensive regimen. For the 35 patients with PMBCL, PFS events were similar, (DA-EPOCHR, 2 of 15 [13%] vs R-CHOP 3 of 20 [15%]), with no patients receiving RT; but, importantly, the study was not designed to evaluate subtypes, and the overall trial results cannot be applied to PMBCL56 (Table 2).

Three retrospective studies have compared outcomes of therapy with DA-EPOCHR and R-CHOP, typically with RT, in PMBCL, with one demonstrating superiority of DA-EPOCHR,57 and the others showing no difference.58,59 Interpretation remains challenging, as the selection criteria for each regimen is unclear, and the studies are underpowered to detect small differences. In the CALGB 50303 study, given that DA-EPOCHR was designed to push chemotherapy doses, it was associated with increased acute hematologic toxicity, including febrile neutropenia, compared with R-CHOP (35% vs 18%; P < .001), and also was noted to have higher frequencies of non-hematologic toxicities, including high-grade neuropathy (grades 3 and 4, 10.8% vs 3.3%).56 A separate study demonstrated that 40% of patients with lymphoma treated with DA-EPOCHR had central line complications, including extravasation from port insertion, and the researchers endorsed a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) for that reason.60 Collectively, the 2-year PFS is 81% to 93% and the 2-year OS is 92% to 97%, in adult patients with PMBCL treated with DA-EPOCHR (Table 2). Although cross-trial comparisons remain limited, there is likely a proportion of patients in whom DA-EPOCHR is warranted, especially those with aggressive presentations, including advanced stage with extrathoracic involvement.

Consolidative RT and use of positron emission tomographic scan in PMBCL

Consolidative mediastinal RT is still frequently delivered after R-CHOP; however, it is unclear whether RT affects the relapse risk or impacts OS, especially for those in complete remission (CR). Retrospective studies have shown conflicting results and are subject to bias caused by variable inclusion criteria, and RT was not administered by uniform criteria. For example, a SEER study of 250 patients with stages I or II PMBCL diagnosed from 2001 through 2012 reported a superior 5-year OS in patients who underwent RT vs those who did not (90% vs 79%; P = .029).61 However, treatment and response data are unknown, and earlier patients may not have received rituximab, which was only approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2006. In contrast, a separate SEER study of 258 cases, including all stages of PMBCL (diagnosed 2006 through 2011) failed to show a difference (5-year OS, treated with RT 82.5% vs nontreated 78.6%; P = .47), despite the no-RT group having a numerically higher proportion of patients with advanced-stage disease (31 vs 19%).62

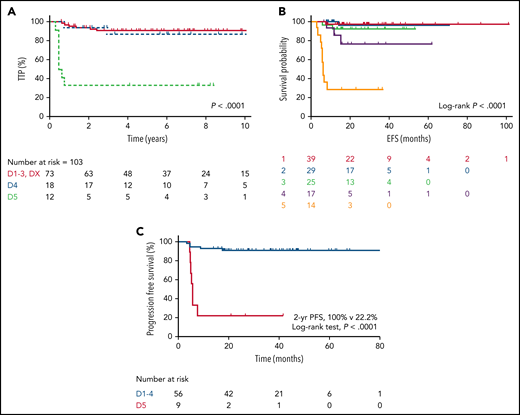

One key benefit of DA-EPOCHR is less reliance on mediastinal RT. Although the long-term effects of modern RT doses remain unknown,63 especially if guided by positron emission tomography (PET), avoidance of RT is relevant in younger patients, given the potential for long-term cardiovascular complications and secondary malignancies, as shown in Hodgkin lymphoma.64,65 Few studies have evaluated the outcome using R-CHOP or R-CHOP–like therapies alone to treat PMBCL and whether a PET scan can be used to guide the use of RT. This approach was first evaluated after MACOPB, where a similar 10-year PFS (∼90%; P = .85) was reported, regardless of end-of-treatment (EOT) PET scan status, with only those with a positive scan (by the International Harmonization Project) receiving RT.66 The International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELSG) evaluated EOT response by PET scan using the more granular Deauville (D) 5-point scale67 after R-VACOPB/R-MACOPB chemotherapy and consolidative RT (IELSG26)68 (Table 3). This study established that D3 (FDG uptake greater than the mediastinum but less than in the liver) should be included as a complete metabolic response at EOT.68 We recently reported the outcome of PMBCL in British Columbia, applying Provincial Lymphoma Tumor Group–endorsed guidelines, whereby an EOT PET scan was used to guide consolidative RT after R-CHOP therapy. Patients with an EOT PET-positive scan were referred for RT, and those with a negative PET scan were observed, regardless of initial disease bulk.13 Overall, for the 113 PET-evaluable population, the 5-year time to progression (TTP) was 82% and the 5-year OS was 94%, with 99% of patients with EOT PET-negative scans receiving chemotherapy alone. For the patients with available Deauville-scored PET scans, the PET-negative (D1-3, DX) and PET-positive (D4, D5) rates were 71% and 29%, respectively (Table 3). In the PET-negative cases, the 5-year TTP and OS were 91% and 97%, respectively, and ultimately, only 11% received RT as a result of reassignment of earlier scans according to the Deauville criteria (Figure 5; Table 3). The negative predictive value was also high in other studies after R-CHOP without RT (92% to 97%)69,70 or DA-EPOCHR (95% to 100%)14,71,72 (Figure 5; Table 3) and increased further if extramediastinal recurrence, including CNS relapse, were excluded.13,69 Larger studies are needed to determine whether the negative predictive value is higher with DA-EPOCHR than with R-CHOP. Importantly, the IELSG37 phase 3 trial is evaluating the role of consolidative RT in PMBCL with an EOT PET-negative scan after investigator’s-choice rituximab chemotherapy, but has not yet been reported (registered at www.clincaltrials.com as NCT01599559).

Outcome of PMBCL by EOT PET Deauville score. Outcomes after R-CHOP (A) and after DA-EPOCHR (B-C). Modified and reproduced from Hayden et al,13 Pinnix et al,71 and, with permission, from Guilino-Roth et al.14

Studies evaluating outcomes in PMBCL by EOT PET scan using Deauville criteria

| Study . | Treatment . | Frequency EOT PET-neg/PET-pos % . | PET-neg D1-3 PFS, % (y) . | PET-pos D4-D5 PFS, % (y) . | Frequency PET pos D4, % . | PET-pos D4 PFS, % (y) . | Frequency PET-pos D5, % . | PET-pos D5 PFS, %(y) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martelli et al, 201468* | R-MACOPB | 70/30 | 99 (5) | 68 (5) | 21 | NR | 9 | NR |

| Vassilakopoulos et al, 2016 69† | R-CHOP | 71/29 | 96 (3) | 61 (3) | 15 | 65 (3) | 14 | 57 (3) |

| Giulino-Roth et al, 201714‡ | DA-EPOCHR | 75/25 | 95 (3) | 55 (3) | 15 | ∼78 (3) | 11 | ∼30 (3) |

| Melani et al, 201872§ | DA-EPOCHR | 69/31 | 96 (8) | 71 (8) | 21 | NR | 10 | 50 (8) |

| Pinnix et al, 201871ǁ | DA-EPOCHR | 62/38 | 100 (2) | 51 (2) | NR | NR | 14 | 22 (2) |

| Hayden et al, 202013¶ | R-CHOP | 71/29 | 92 (5) | 68 (5) | 17 | 87 (5) | 12 | 33 (5) |

| Vassilakopoulos et al, 202170# | R-CHOP | 73/27 | 92-97 (5) | NR | 16 | 82 (5) | 11 | 44 (5) |

| Study . | Treatment . | Frequency EOT PET-neg/PET-pos % . | PET-neg D1-3 PFS, % (y) . | PET-pos D4-D5 PFS, % (y) . | Frequency PET pos D4, % . | PET-pos D4 PFS, % (y) . | Frequency PET-pos D5, % . | PET-pos D5 PFS, %(y) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martelli et al, 201468* | R-MACOPB | 70/30 | 99 (5) | 68 (5) | 21 | NR | 9 | NR |

| Vassilakopoulos et al, 2016 69† | R-CHOP | 71/29 | 96 (3) | 61 (3) | 15 | 65 (3) | 14 | 57 (3) |

| Giulino-Roth et al, 201714‡ | DA-EPOCHR | 75/25 | 95 (3) | 55 (3) | 15 | ∼78 (3) | 11 | ∼30 (3) |

| Melani et al, 201872§ | DA-EPOCHR | 69/31 | 96 (8) | 71 (8) | 21 | NR | 10 | 50 (8) |

| Pinnix et al, 201871ǁ | DA-EPOCHR | 62/38 | 100 (2) | 51 (2) | NR | NR | 14 | 22 (2) |

| Hayden et al, 202013¶ | R-CHOP | 71/29 | 92 (5) | 68 (5) | 17 | 87 (5) | 12 | 33 (5) |

| Vassilakopoulos et al, 202170# | R-CHOP | 73/27 | 92-97 (5) | NR | 16 | 82 (5) | 11 | 44 (5) |

Estimates (∼) are rounded. Frequencies of D4 and D5 reflect proportions in the entire cohort.

EOT, end of treatment; NR, not reported; neg, negative; PD, progressive disease; PFS progression free survival; pos, positive.

EOT PET scan for central review was performed on 115 patients (4 with early PD excluded); RT in 94% of PET-neg; PFS estimates NR separately in D4 and D5; however, in categories D4, 5 of 24 (21%), and in D5, and 6 of 10 (60%) patients relapsed/progressed.

Included only responding patients with PMBCL; RT in 49%; 12% received R-CHOP14; FFP reported.

Excluded 2 patients with early PD before EOT PET scan.

Survival estimates not reported separately for D4; however, 1 of 17 relapsed/progressed patient (6%) had EFS.

Included only patients with pre-PET and EOT PET scans.

Excluded 1 patient with early PD before EOT PET; RT in 11% (due to reassignment of earlier scans according to Deauville criteria; 2 patients had DA-EP OCHR; TTP reported).

Extended results of prior study: 231 responding patients; PET-neg, RT in 72%, RT (D1-2 47% vs D3 96%; 5-year FFP 100% vs 92%; mediastinal only 100% vs 96%. P = .16); PET-pos RT in 89% (D4 97% vs D5 80%); FFP reported.

In contrast, for the ∼30% of patients with a positive EOT PET scan, the positive predictive value (PPV) was very low (Table 3). However, this is highly driven by the EOT Deauville score with the PPV of an EOT score of D4 notably poor (Figure 5), regardless of frontline therapy; however, outside of studies using DA-EPOCHR, most patients received RT. In the BC Cancer study of primarily R-CHOP–treated PMBCL, overall, the PET-positive cases (D4, D5) had an inferior 5-year TTP (68%) compared with PET-negative cases but it was far superior in D4 vs D5 cases where the 5-year TTP was 87% vs 33%, respectively. The D4 EOT PET-positive cases had outcomes similar to those of the PET-negative cases and, although 4 patients were observed without subsequent relapse, overall, 72% underwent RT.13 Of note, in this study, an EOT PET-positive scan was more frequent in those with bulky disease at diagnosis and led to a greater proportion receiving consolidative RT (33% [bulky] vs 16% [non-bulky]; P = .06). A separate study from Greece demonstrated a less favorable outcome of D4 (3-year freedom from progression [FFP], 65%; Table 3) after R-CHOP, where 15 of 16 patients received RT, and the investigators found that a maximum standardized uptake value (SUV) of ≥5 was predictive of relapse. An extension of this study to include 231 patients with PMBCL treated with R-CHOP by EOT PET using the Deauville criteria,, and noted a 5-year FFP of 82% in D4 patients, of which 28 of 29, had received RT. After DA-EPOCHR therapy, favorable outcomes are consistently observed in D4 cases, with most not including RT.14,71,72 In an expanded study of 93 patients from the NCI phase 2 study and Stanford series, only 1 of 17 patients with a D4 EOT scan relapsed and none received RT.72 Taken together, the data support observation with serial PET scans after DA-EPOCHR with a D4 score. However, further studies are needed to determine whether this approach is appropriate after R-CHOP, with repeat biopsy favored when possible.

In contrast to EOT D4 scans, for the 11% to 14% of patients with a EOT D5 scan (Table 3), the PPV is much higher, and outcome is poor, regardless of frontline therapy, with a 5-year TTP/PFS of 22% to 57%13,14,69,71 (Figure 5), with consolidative RT less effective in one study (5-year TTP 92% D4 vs 57% D5).13 The variability in outcome may be related to the inclusion of both marked fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake and new lesions (ie, progressive disease) in the D5 definition. Regardless, events are typically early, and most of the patients have refractory disease. It is important also to note that some PET-focused studies included only responding patients,70,73 and others may have excluded a minority of very high-risk patients who may have progressed at an earlier time point (Table 5).

In general, most R-CHOP-like–treated patients can be effectively treated without RT; however, overall, RT use is still more frequent than with DA-EPOCH, in part because of the lack of certainty of whether a D4 score represents false-positive disease. In younger patients with bulky disease, DA-EPOCHR may still be preferred in centers with expertise, as it largely avoids mediastinal RT.

PET radiomics in PMBCL

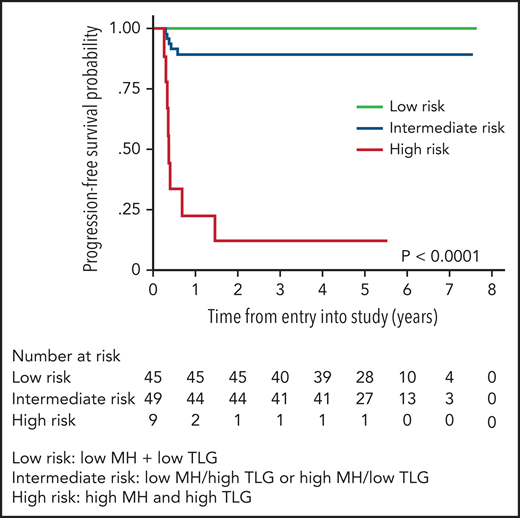

PET radiomics has emerged as an evolving field whereby baseline quantitative 18FDGPET/computed tomographic (CT) parameters can be important predictors of outcome. Volume-based metabolic assessment including maximum standard uptake volume, metabolic tumor volume, and total lesion glycolysis (TLG) were correlated with prognosis in patients in the IELSG study in those with staging PET scans available (n = 103).74 TLG, which combines tumor volume and metabolism on baseline PET/CT scan, emerged as the most robust predictor of outcome, where the 5-year PFS was 64% vs 99% in those with a high vs low TLG, respectively, with similar findings in a separate study using DA-EPOCHR (high TLG, 2-year PFS 60% vs low TLG, 2-year PFS 95%; P = .006).71 Building on this result, the IELSG evaluated metabolic heterogeneity (MH), and found that, in multivariate analysis, only MH and TLG were associated with a shorter PFS, and combining these 2 factors identified 10% of all patients with a 5-year PFS of only 11%75 (Figure 6). Given the challenges of applying clinical risk models to PMBCL, this approach represents a potential means of identifying a subset that may need an alternate treatment approach.

PFS by combined MH (metabolic heterogeneity) and TLG (total lesion glycolysis). Low risk (MH and TLG low); intermediate risk (either low MH and high TLG or high MH and low TLG); high risk (high MH and high TLG). Modified and reproduced from Ceriani et al.75

PFS by combined MH (metabolic heterogeneity) and TLG (total lesion glycolysis). Low risk (MH and TLG low); intermediate risk (either low MH and high TLG or high MH and low TLG); high risk (high MH and high TLG). Modified and reproduced from Ceriani et al.75

Relapsed/refractory PMBCL

Almost all treatment failures in PMBCL occur within the first 2 years, with the exception of rare, late CNS relapse, which occurs in ∽2.5% to 4.5% overall.13,15,71 Management of relapsed/refractory (R/R) PMBCL parallels DLBCL, where salvage therapy is administered, followed by high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), if a response is documented. There have been limited studies evaluating the outcome of R/R PMBCL, particularly in the rituximab treatment era, and very few have evaluated the intent-to-transplant (ITTx) population (Table 4). An earlier study of 37 patients with R/R PMBCL from Princess Margaret Cancer Centre (PMCC), almost entirely in the era before rituximab, demonstrated a transplant rate of only 22% and 2-year OS of only 15% in ITTx R/R PMBCL. For the transplant recipients, the 2-year OS was 67%. In contrast, a recent study of 51 patients with R/R PMBCL from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre (MSKCC) demonstrated an 85% transplant rate and a 3-year PFS and OS of 57% and 61% in the ITTx population, respectively, with only slightly better rates in those who underwent transplant (60% and 65%, respectively).76 The investigators credited the excellent outcomes to the integration of mediastinal RT in 90% of patients before transplant.76 Outcomes were also more favorable after ASCT in other series with 5-year OS 57% to 70%,13,77,78 but a 5-year OS of only 48% in the ITTx group, suggesting salvage failure in some cases13 (Table 4). Overall, patients with refractory disease seem to fare worse and may benefit from alternate treatment approaches.

Select studies evaluating the outcome of relapsed/refractory PMBCL

| Study . | n (% rituximab primary treatment) Year of primary diagnosis . | Outcomes in intention to transplant . | . | Post-ASCT outcomes . | % Salvage RT pre- vs post- ASCT . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFS, % (y) . | OS, % (y) . | ASCT rate, % . | PFS/EFS, % (y) . | OS, % (y) . | |||

| Kuruvilla et al, 2005104 | 37 3 1995-2004 | 15 (2) | 15 (2) Rel 29 (2) Ref 31 (2) | 22 | 57 (2) | 67 (2) | NR |

| Aoki et al, 201577 | 44 66 1996-2012 | NR | NR | NR | 61 (4)* | 70 (4)* Rel 73 (4) Ref 65 (4) | NR |

| Avivi et al, EBMT, 201878† | 86 85 2000-2012 | NR | NR | NR | 62 (5) Rel 64 (5) Ref 39 (5) | 71 (5) 77 (5) 41 (5) | 30 pre |

| Vardhana et al, 201876 | 60 40 1989-2014 | 57 (3) | 61 (3) | 85 | 60 (3) | 65 (3) | 90 pre |

| Hayden et al, 202013 | 31 100 2001-2018 | NR | 48 (5) | Rel 78 Ref 75 | NR | 57 (5) Rel 71 (5) Ref 50 (5) | 36 post |

| Study . | n (% rituximab primary treatment) Year of primary diagnosis . | Outcomes in intention to transplant . | . | Post-ASCT outcomes . | % Salvage RT pre- vs post- ASCT . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFS, % (y) . | OS, % (y) . | ASCT rate, % . | PFS/EFS, % (y) . | OS, % (y) . | |||

| Kuruvilla et al, 2005104 | 37 3 1995-2004 | 15 (2) | 15 (2) Rel 29 (2) Ref 31 (2) | 22 | 57 (2) | 67 (2) | NR |

| Aoki et al, 201577 | 44 66 1996-2012 | NR | NR | NR | 61 (4)* | 70 (4)* Rel 73 (4) Ref 65 (4) | NR |

| Avivi et al, EBMT, 201878† | 86 85 2000-2012 | NR | NR | NR | 62 (5) Rel 64 (5) Ref 39 (5) | 71 (5) 77 (5) 41 (5) | 30 pre |

| Vardhana et al, 201876 | 60 40 1989-2014 | 57 (3) | 61 (3) | 85 | 60 (3) | 65 (3) | 90 pre |

| Hayden et al, 202013 | 31 100 2001-2018 | NR | 48 (5) | Rel 78 Ref 75 | NR | 57 (5) Rel 71 (5) Ref 50 (5) | 36 post |

Outcomes are for >1 CR/PR and refractory disease.

NR, not reported; ref, refractory; rel, relapsed.

Five patients underwent allo-SCT.

Includes 16 patients who underwent transplant in first remission (included in overall PFS and OS estimate only).

New approaches in relapsed/refractory PMBCL

PD1 inhibitors in PMBCL

Proof of principle of the efficacy of PD1 inhibitors in PMBCL first came from the phase 1 KEYNOTE-013 study, which evaluated pembrolizumab across cohorts with R/R lymphoma, including PMBCL.79 In the updated analysis, the objective response rate (ORR) in R/R PMBCL was 48% (CR 33%), and similar results were observed in the subsequent phase 2 study, the KEYNOTE-170 trial, with an ORR of 45% and a CR of 13%. With a median follow-up of 29.1 months (KEYNOTE-013) and 12.5 months (KEYNOTE-170), the median PFS was 10.4 and 5.5 months, respectively, and the median duration of response (DOR) was not yet reached in either study.80 Pembrolizumab was used as a bridge to transplant in 9 patients. Grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events (AEs) occurred in 23% of patients, and neutropenia was the most common high-grade AE (13.5%). This data led to FDA approval of pembrolizumab in R/R PMBCL for the treatment of adult and pediatric patients who have relapsed after 2 or more lines of therapy.

The PD1 inhibitor nivolumab was combined with the anti-CD30 antibody drug conjugate brentuximab vedotin (BV) in the CheckMate 436 study, which included a cohort of patients with R/R PMBCL.81 Despite an ORR of only 13% in a prior study with BV alone in R/R PMBCL,82 the ORR was 73% and CR was 37%, which reflects the potential synergy of PD1 therapy combined with other systemic agents.81 Half of the responding patients (n = 11) underwent subsequent SCT and none have relapsed. Grade 3 and 4 treatment-related AEs were higher (53%) than with single-agent PD1 inhibitor, with 30% neutropenia and 10% peripheral neuropathy (27% overall). IRAEs were reported in 10 patients (grade 3; n = 3). Studies are underway integrating PD1 inhibitors in the up-front setting in PMBCL (supplemental Table 2).

Cellular therapies in relapsed/refractory PMBCL

CAR T-cell therapy is a form of cellular therapy using patients’ autologous T lymphocytes that are genetically engineered to express an anti-CD19 single-chain fragment on the cell surface, linked to costimulatory proteins required for T-cell activation. CAR T-cell therapy has changed the landscape of treatment of R/R CD19+ aggressive large B-cell lymphomas, including PMBCL, with seemingly curative potential at a stage of disease where the OS is typically <6 months.83 The ZUMA-1 and TRANSCEND NHL001 studies tested axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) and tisagenlecleucel products, respectively, in R/R aggressive large B-cell lymphomas (including PMBCL) after failure of at least 2 lines of therapy.84 Response assessment in the ZUMA-1 study initially grouped PMBCL (n = 8) with transformed follicular lymphoma, but regardless, the ORR was 71% with CR of 12% in the initial report.84 For all 119 patients in the study, the ORR was 83%, with 58% CR and a median PFS and DOR of 5.6 and 11.1 months, respectively, and the 2-year PFS was ∼40%.85 In a subsequent report with a median follow-up of 27 months, ongoing responses were maintained in 5 of 8 cases of PMBCL.85 Similarly, in the TRANSCEND study the ORR was 73% and CR was 53% for all enrolled patients, and in the 15 patients with R/R PMBCL (14 evaluable), ORR was 79% (CR not stated). Median PFS was 6.8 months for all patients and 1-year PFS was 44% in all patients, 65% for patients in CR and median DOR not yet reached.86 These data led to FDA approval of both agents and, if available, CAR T-cell therapy is the preferred option in R/R PMBCL after failure of 2 lines of therapy, including ASCT.

Other novel therapies/treatment approaches

Given that most cases of PMBCL are CD30+, they were included in a phase 1/2 study of CD30+ B-cell lymphomas evaluating BV and CHP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, prednisone; CHP+BV).87 In the 22 patients with PMBCL, 2-year PFS was 86% and 2-year OS was 100%, with no difference made by the addition of consolidative RT (P = .95). Overall, 11 of 14 (79%) were confirmed molecular PMBCL by Lymph3x, which implies that there is some imprecision in clinicopathologic diagnoses of PMBCL.87 The antibody drug conjugate loncastuximab (ADCT-402) was evaluated in R/R B-cell NHL, and although only 2 cases of PMBCL were included, the ORR for all patients was 42% and the CR was 23%, with some durable responses, albeit with moderate hematologic toxicity (71% thrombocytopenia, 59% neutropenia), leading to recent FDA approval. Bispecific antibodies are under investigation across a range of B-cell lymphomas but have not specifically included PMBCL. Despite evidence of aberrant activation of the JAK/STAT pathway in PMBCL, use of JAK2 inhibitors has not been fruitful to date. A pilot study evaluated ruxolitinib in R/R cHL and R/R PMBCL and none of the patients with PMBCL responded.88 Whether combination therapy with PD1 inhibitor will translate into clinical benefit remains unknown.89

Summary

There have been significant scientific advances over the past 20 years in dissecting the disease biology of PMBCL. Integral to disease pathogenesis is an immune-privileged phenotype that has led to pivotal studies and approval of PD1 inhibitors in R/R PMBCL. Although most patients have an excellent outcome with R-chemoimmunotherapy, ∼10% of patients have refractory disease, regardless of primary therapy, providing a strong rationale to integrate PD1 inhibitors in the up-front setting. Finally, further study of radiomics and biomarkers at diagnosis may help to identify patients who would benefit from alternative treatment approaches.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges Jane Rowlands for figure creation, Christian Steidl and David Scott for manuscript review, and Jeffrey Craig and Graham Slack for supplying the histology figure and for manuscript review.

Authorship

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: K.J.S. has received honoraria and consulting fees from Seattle Genetics, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck, Novartis, Kyowa, Janssen, and AstraZeneca and consulting fees from Servier; has been a member of the Data Safety Monitoring Committee of Regeneron; and has served on the Steering Committee of Beigene.

Correspondence: Kerry J. Savage, Centre for Lymphoid Cancer, BC Cancer, 600 West 10th Ave, Vancouver, BC V5Z 4E6, Canada; e-mail: ksavage@bccancer.bc.ca.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal