TO THE EDITOR:

In chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), presence of complex karyotype (CKT; ie, ≥3 chromosomal abnormalities in ≥2 metaphases) has adverse prognostic significance.1-5 The impact of targeted agents on CLL patients with CKT has been analyzed retrospectively and mostly in patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) CLL. Although treatment with idelalisib plus rituximab seems to have comparable efficacy in patients with R/R, both with and without CKT (NCKT),6 data on ibrutinib indicate adverse outcomes in patients with CKT.3 Limited data on CKT and venetoclax monotherapy are available, with 1 analysis indicating poorer outcomes in patients with CKT and 1 analysis showing unaltered efficacy in CKT patients.7,8 In contrast to patients with R/R, CLL treated with ibrutinib, patients with previously untreated CLL who receive frontline ibrutinib have comparable progression-free survival (PFS), irrespective of CKT, as recent data suggest.9,10

The CLL14 trial was a global, randomized, phase 3 trial that demonstrated improved PFS of fixed-duration venetoclax plus obinutuzumab (VenG) as compared with chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab (ClbG) across all high-risk groups, including patients with TP53 aberrations and unmutated IGHV status.11 Here, we present the first analysis of the impact of CKT on the clinical outcomes of patients treated with VenG vs ClbG.

Chromosome analysis was successfully performed in 397 (91.9%) of 432 patients (supplemental material). This consisted of 197 and 200 patients from the ClbG and VenG treatment groups, respectively (supplemental Table 1). Overall, CKT was found in 30 patients (15.2%) in the ClbG arm and 34 (17.0%) in the VenG arm. In the ClbG arm, median age was 71 years in NCKT patients and 74 in CKT patients. Thirteen patients with NCKT (8.0%) and 9 patients with CKT (31.0%) had a del(17p) or TP53 mutation or both. Unmutated IGHV status was detected in 95 patients with NCKT (58.6%) and 18 patients with CKT (62.1%). The study was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT02242942 and http://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu as #EudraCT2014-001810-24.

For the VenG arm, median age was 72 years in patients with NCKT and 69 years in patients with CKT. Twelve patients with NCKT (7.4%) and 11 patients with CKT (33.3%) had a del(17p) or TP53 mutation or both. Unmutated IGHV status was detected in 96 patients with NCKT (61.5%) and 20 patients with CKT (66.7%).

In both arms, most patients with CKT were in the high or very high CLL International Prognostic Index risk group (82.2% and 79.3%, respectively), which was comparable to patients with NCKT.

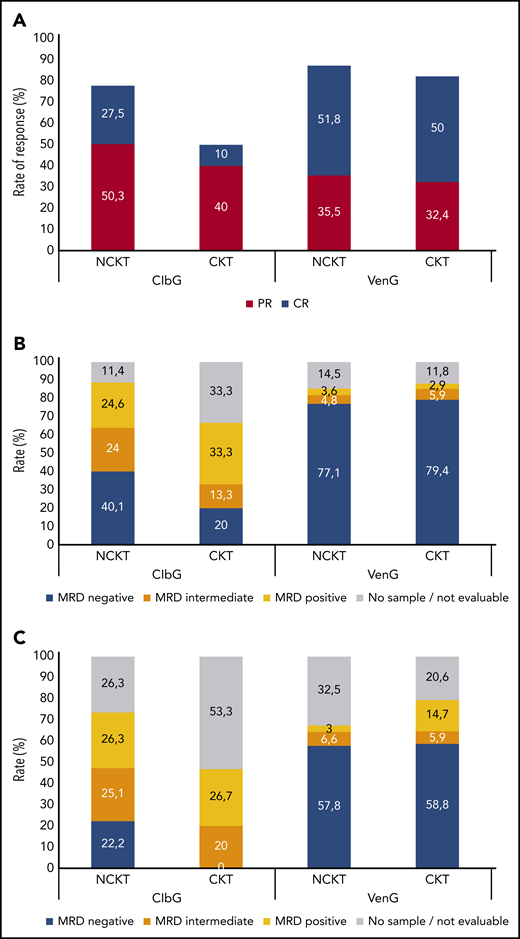

In the ClbG arm, overall response rate (ORR) 3 months after treatment completion was lower in patients with CKT (50%) than in patients without CKT (78%; P = .003; Figure 1A). Likewise, the rate of complete responses was 10% in the CKT group and 27.5% in the NCKT group (P = .041). In contrast, no differences were observed between patients with CKT and NCKT in the VenG arm, with ORRs of 82.4% and 87.3% (P = .42), respectively, and complete response rates of 50.0% and 51.8% (P = .85), respectively.

Response to treatment. Rates of complete response (CR) and partial response (PR) (A) and rates of measurable residual disease (MRD) negativity (MRD negative, 10−4; MRD intermediate, ≥10−4 and <10−2; MRD positive, ≥10−2) in peripheral blood (B) and bone marrow (C) 3 months after completion of treatment, according to treatment with ClbG or VenG and according to CKT or NCKT status. MRD rates are reported in the intention-to-treat population and 3 months after completion of treatment; therefore, patients who progressed before this time point were censored at last tumor assessment, and those with missing sample were reported as no sample/not evaluable.

Response to treatment. Rates of complete response (CR) and partial response (PR) (A) and rates of measurable residual disease (MRD) negativity (MRD negative, 10−4; MRD intermediate, ≥10−4 and <10−2; MRD positive, ≥10−2) in peripheral blood (B) and bone marrow (C) 3 months after completion of treatment, according to treatment with ClbG or VenG and according to CKT or NCKT status. MRD rates are reported in the intention-to-treat population and 3 months after completion of treatment; therefore, patients who progressed before this time point were censored at last tumor assessment, and those with missing sample were reported as no sample/not evaluable.

The rate of MRD negativity (<10−4) in the ClbG arm 3 months after treatment completion was lower in patients with CKT than in patients with NCKT in peripheral blood (20.0% vs 40.1%; P = .041) as well as bone marrow (0.0% vs 22.2%; P = .002; Figure 1B). The rates of patients with intermediate MRD levels (≥10−4 and <10−2) were comparable in patients with CKT and NCKT, both in peripheral blood (13.3% vs 24.0%; P = .60) and bone marrow (20.0% vs 25.1%; P = .56).

In the VenG arm, the rates of MRD negativity did not differ significantly between patients with CKT and NCKT, at 79.4% vs 77.1% (P = 1.0) in peripheral blood and 58.8% vs 57.8% (P = 1.0) in bone marrow. Similarly, the rates of intermediate MRD levels were comparable in peripheral blood (5.9% vs 4.8%; P = .69) and bone marrow (5.9% vs 6.6%; P = 1.0).

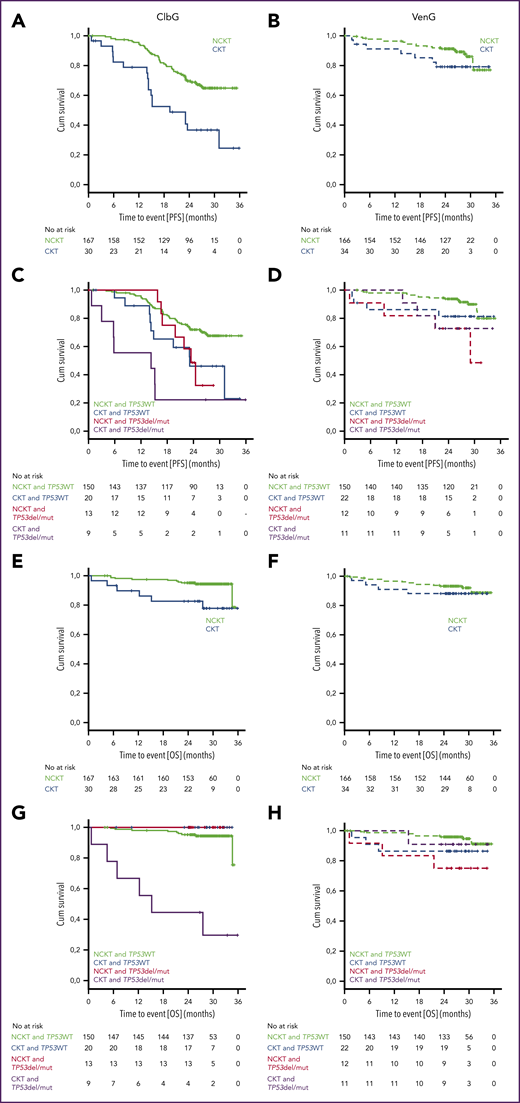

Median PFS in the ClbG arm was 19.4 months (2-year PFS rate, 36.6%) in patients with CKT, which was significantly shorter than in patients with NCKT, where median was not reached (NR; 2-year PFS rate, 69.6%; hazard ratio [HR], 2.790; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.631-4.772; P < .001; Figure 2A). OS was significantly shorter in patients with CKT vs NCKT (median, NR; 2-year OS rate, 82.7% and 95.1%, respectively; HR, 3.736; 95% CI, 1.357-10.287; P = .006; Figure 2E).

Progression-free and overall survival. Kaplan-Meier plots of PFS (A-D) and overall survival (OS) (E-H) for patients treated with ClbG (A,C,E,G) and VenG (B,D,F,H) according to presence of del(17p) or TP53 mutation (TP53del/mut) or TP53 wild type (TP53WT) as well as CKT, NCKT, or highly CKT (HCKT)/intermediate CKT (ICKT) status.

Progression-free and overall survival. Kaplan-Meier plots of PFS (A-D) and overall survival (OS) (E-H) for patients treated with ClbG (A,C,E,G) and VenG (B,D,F,H) according to presence of del(17p) or TP53 mutation (TP53del/mut) or TP53 wild type (TP53WT) as well as CKT, NCKT, or highly CKT (HCKT)/intermediate CKT (ICKT) status.

In the VenG arm, median PFS was NR in the CKT or the NCKT group, and no statistically significant differences were observed between groups (2-year PFS rate, 78.9% and 91.1%, respectively; HR, 1.909; 95% CI, 0.806-4.520; Figure 2B). No statistically significant differences in OS were observed between patients with CKT and NCKT (median, NR; 2-year-OS rate, 88.2% and 93.2%; HR, 1.511; 95% CI, 0.496-4.600; Figure 2F).

Presence of a del(17p) or TP53 mutation in patients with CKT altered PFS compared with patients without a del(17p) or TP53 mutation in the ClbG arm (HR, 2.103; 95% CI, 0.795-5.567) but not in the VenG arm (HR, 1.419; 95% CI, 0.317-6.353; Figure 2C-D), although the differences did not reach statistical significance. OS was not affected by presence of a del(17p) or TP53 mutation in the ClbG arm (HR and CI not evaluable) or the VenG arm (HR, 0.620; 95% CI, 0.064-5.962) in the CKT group (Figure 2G-H).

Because the number of chromosomal aberrations has been suggested to correlate with prognosis,12 in a separate approach, patients with CKT were separated into a group with HCKT (ie, with ≥5 chromosomal aberrations) and a group with <5 but ≥3 aberrations (ICKT). Overall, HCKT was detected in 10 patients in the ClbG arm (5.1%) and 11 patients in the VenG arm (5.5%); ICKT was detected in 20 (10.2%) and 23 (11.5%), respectively. Response rates, rates of MRD negativity, and PFS and OS rates (supplemental Figure 1A-B) did not differ significantly between patients with ICKT and HCKT (supplemental Methods).

The analysis of the CLL14 trial confirms previous reports on CKT in Clb-based treatments in 197 ClbG-treated patients with successful karyotyping.4,13,14 CKT patients not only had a lower ORR and rate of MRD negativity but also had a significantly shorter PFS as well OS vs NCKT patients. Again, this effect was observed irrespective of presence of del(17p) or TP53 mutation, which supports the assumption that CKT might be an independent adverse prognostic factor.

The results with VenG consistently showed similar efficacy regarding ORR, PFS, and OS in CKT and NCKT patients. A tendency toward shorter PFS can be derived from the Kaplan-Meier plots; however, this difference did not reach statistical significance, and given that, in contrast to the ClbG arm, response and MRD rates did not differ between patients with CKT and NCKT, it stands to reason that VenG has similar efficacy in patients with CKT as in patients with NCKT. Longer follow-up is warranted to see whether these deep responses are maintained in patients with both CKT and NCKT.

In summary, this analysis shows that CKT can be frequently observed in elderly, treatment-naïve patients with CLL. Frontline treatment with VenG, but not ClbG, shows similar efficacy in patients with CKT and NCKT. Therefore, patients with CKT might particularly benefit from upfront treatment with novel agents.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the patients, their families, and their nurses and physicians for their participation in the trial.

This study was supported by F. Hoffmann-La Roche and AbbVie; genetic analyses were partly funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche, AbbVie, and the Deutsche José Carreras Leukämie-Stiftung (23 R/2017); and E.T. and S.S. were supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB1074 subproject B1 B2) and Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (PRECiSe).

Authorship

Contribution: O.A.-S., K.F., M.H., and K.-A.K. designed the research, collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data, and wrote the paper; J.B. and S.R. performed the statistical analysis and wrote the paper; E.L., A.-M.F., M.P., M.T., Y.J., W.S., and B.E. interpreted and reviewed the data; M.R. performed the MRD analyses; E.T. and S.S. performed the cytogenetic analyses and interpreted and reviewed the data; and all authors critically reviewed and approved the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: O.A.-S. reports personal fees and nonfinancial support from AbbVie, Roche, Gilead, and Janssen outside the submitted work. J.B. reports nonfinancial support from Roche during the conduct of the study and personal fees and nonfinancial support from Roche outside the submitted work. B.E. reports grants and personal fees from Roche and AbbVie outside the submitted work. A.-M.F. reports personal fees from Janssen Pharmaceutical outside the submitted work. K.F. reports nonfinancial support from Roche during the conduct of the study. M.H. reports grants and personal fees from Roche and AbbVie during the conduct of the study, grants and personal fees from Gilead and Janssen, and personal fees from Celgene and Boehringer Ingelheim outside the submitted work. W.S. reports personal fees from AbbVie outside the submitted work. Y.J. reports personal fees from Genentech outside the submitted work. K.-A.K. reports grants and personal fees from Roche and AbbVie during the conduct of the study. M.R. reports grants from Roche/AbbVie and personal fees from Roche during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Roche and AbbVie outside the submitted work. S.S. reports grants, personal fees, and nonfinancial support from AbbVie and Hoffmann La-Roche during the conduct of the study and grants, personal fees, and nonfinancial support from AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Celgene, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffmann La-Roche, Janssen, Novartis, Pharmacyclics, grants, and Sunesis outside the submitted work. M.T. reports personal fees from Roche Products Ltd outside the submitted work. E.T. reports personal fees from Roche AG and personal fees and nonfinancial support from AbbVie during the conduct of the study. E.L., M.P., and S.R. report no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Othman Al-Sawaf, Department I of Internal Medicine and Center of Integrated Oncology Aachen-Bonn-Cologne-Duesseldorf, University of Cologne, Kerpener Strasse 62, 50937, Cologne, Germany; e-mail: othman.al-sawaf@uk-koeln.de; and Karl-Anton Kreuzer, Department I of Internal Medicine and Center of Integrated Oncology Aachen-Bonn-Cologne-Duesseldorf, University of Cologne, Kerpener Strasse 62, 50937, Cologne, Germany; e-mail: karl-anton.kreuzer@uni-koeln.de.

REFERENCES

Author notes

K.F., M.H., and K.-A.K. contributed equally to this work.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal