Background:Myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is a common post-remission treatment strategy for medically fit adults with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in morphologic remission. Several conditioning regimens have been utilized for this purpose, with ongoing controversy regarding the benefit of high-dose total body irradiation (TBI) in this setting. It is also unknown whether the relative value of TBI- versus non-TBI-based myeloablative conditioning differs for patients presenting with measurable residual disease (MRD) at the time of HCT from those in MRDnegremission. These open questions prompted us to compare outcomes among a large cohort of adult AML patients in MRDposand MRDnegremission who had myeloablative allogeneic HCT at our institution.

Patients and Methods:We retrospectively studied 387 consecutive adults ≥18 years with AML in first or second morphologic remission (i.e. <5% bone marrow blasts by morphologic assessment) who had myeloablative allogeneic HCT from a peripheral blood or bone marrow donor between 4/2006 and 1/2019. Patients receiving radiolabeled antibodies as part of their conditioning were excluded. Pre-HCT disease staging included 10-color multiparametric flow cytometry (MFC) on bone marrow aspirates in all patients. MRD was identified as a cell population showing deviation from normal antigen expression patterns compared with normal or regenerating marrow. Any level of residual disease was considered MRDpos.

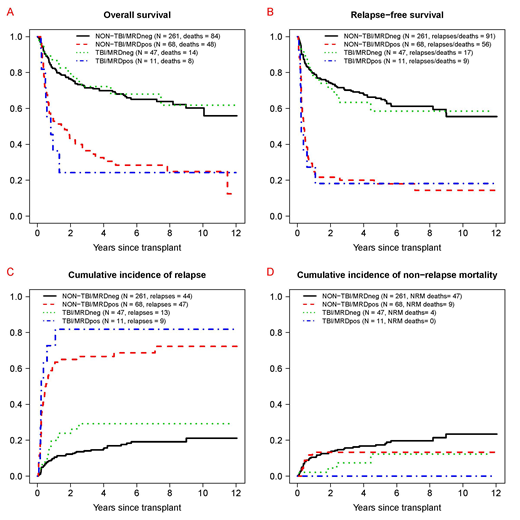

Results: Fifty-eight of the 387 patients (15%) received high-dose (HD; ≥12 Gy) TBI-based conditioning (HD-TBI/Cy [n=32], HD-TBI/thiotepa/Flu [n=22], HD-TBI±Flu [n=4]). Regimens for the other 329 patients included Bu/Cy [n=160], Bu/Flu [n=72], and treosulfan/Flu±low-dose TBI [n=97]. Patients receiving HD-TBI conditioning were younger (median: 33 [range: 18-58] vs. 51 [18-70] years, p<0.001), had a higher white blood cell count at AML diagnosis (34.5 [0.6-280] vs. 8.4 [0.2-297] x103/µL, p=0.004), less often had secondary AML (5% vs. 25%, p<0.001), and less often had an unrelated donor as stem cell source (43% vs. 67%, p<0.001) than those receiving non-HD-TBI conditioning. The cytogenetic risk profile (revised MRC criteria) was similar (p=0.76), as was the proportion of patients in second rather than first remission (HD-TBI vs. non-HD-TBI: 28% vs. 22%, p=0.31), the proportion of patients with MRD by MFC at the time of HCT (19% vs. 21%, p=0.86), and the proportion of patients with recovered peripheral blood counts at the time of HCT (66% vs. 77%, p=0.10). Overall, 3-year estimates of overall survival (OS), relapse-free survival (RFS), cumulative incidence of relapse, and non-relapse mortality (NRM) were similar for patient with HD-TBI and those without HD-TBI conditioning (OS: 63% [95% confidence interval: 51-78%] vs. 64% [59-70%]; RFS: 55% [43-70%] vs. 60% [55-65%]; relapse: 39% [26-52%] vs. 25% [20-30%]; NRM: 6% [1-13%] vs. 15% [11-19%]). Likewise, when stratified by the pre-HCT MRD status, OS, RFS, relapse, and NRM estimates were similar for patient with HD-TBI and those without HD-TBI conditioning (Figure). In multivariable models accounting for type of conditioning (HD-TBI vs. not), pre-HCT MRD status, age, cytogenetic risk, type of AML (de novo vs. secondary AML), CR1 vs. CR2, pre-HCT karyotype (normalized vs. not), and pre-HCT peripheral blood counts (recovered vs. not), MRDposremission remained statistically associated with increased mortality (hazard ratio [HR]=2.99 [95% confidence interval: 2.08-4.30], p<0.001), failure of RFS (HR=4.49 [3.18-6.33], p<0.001), and increased risk of relapse (HR=7.21 [4.77-10.88], p<0.001) but not NRM (HR=0.63 [0.29-1.37], p=0.24). On the other hand, compared to non-HD-TBI conditioning, HD-TBI conditioning was not associated with different outcomes: OS (HR=0.91 [0.56-1.48], p=0.70), RFS (HR=0.83 [0.53-1.32], p=0.44), relapse risk (HR=1.06 [0.59-1.88], p=0.85), or NRM (HR=0.44 [0.15-1.28], p=0.54).

Conclusion:For adults with AML undergoing myeloablative allogeneic HCT in morphologic remission, our analyses found no differences in survival and relapse risks between patients who received HD-TBI and those who received non-HD-TBI containing conditioning. Considering the known late effects of HD-TBI, non HD-TBI regimens should be used preferentially.

Othus:Celgene: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; Glycomimetics: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees. Walter:Aptevo Therapeutics: Consultancy, Research Funding; Argenx BVBA: Consultancy; Astellas: Consultancy; BioLineRx: Consultancy; BiVictriX: Consultancy; Boehringer Ingelheim: Consultancy; Boston Biomedical: Consultancy; Kite Pharma: Consultancy; New Link Genetics: Consultancy; Pfizer: Consultancy, Research Funding; Race Oncology: Consultancy; Seattle Genetics: Research Funding; Covagen: Consultancy; Daiichi Sankyo: Consultancy; Agios: Consultancy; Amgen: Consultancy; Amphivena Therapeutics: Consultancy, Equity Ownership; Jazz Pharmaceuticals: Consultancy.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This icon denotes a clinically relevant abstract

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal