In this issue of Blood, Hellmuth et al provide new insights into the molecular genetic profile of duodenal-type follicular lymphoma (FL), with comparisons to both typical advanced-stage nodal FL and a lesser number of cases of FL with limited stage disease.1

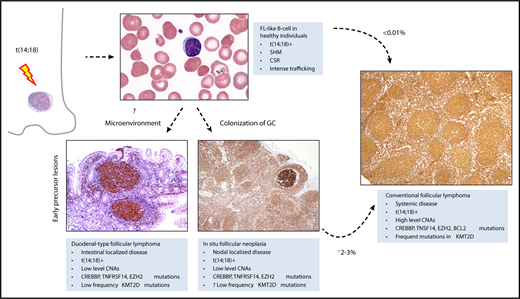

The t(14;18) occurs in a precursor B cell in the bone marrow. B cells carrying the t(14; 18) can be detected at very low levels in the peripheral blood of >50% of healthy adults. These cells have undergone somatic hypermutation (SHM), and class switch recombination (CSR), indicative of transit through the germinal center. They are prone to intense trafficking, with multiple episodes of germinal center reentry. However, <0.01% of patients with FL-like B cells in the peripheral blood subsequently develop FL. Expansion of FL-like B cells, in either the intestine or the lymph node, lead to 2 early lesions, duodenal-type FL, and ISFN. ISFN can be identified in ∼2% to 3% of unselected lymph node biopsies. Both duodenal-type FL and ISFN progress to systemic FL in only 2% to 3% of cases. These early lesions have a low level of copy number aberrations (CNAs), but share many genetic features with conventional FL, including the t(14;18), and mutations in CREBBP, TNFRSF14, and EZH2. However, multiple mutations in KMT2D may be a later event, associated with more advanced disease. Microenvironmental influences may drive colonization of the intestine, independent of the genetic profile. All tissue sections illustrated are stained for BCL2 by immunohistochemistry, original magnification ×40. Peripheral smear, Wright-Giemsa stain, original magnification ×1000. GC, germinal center.

The t(14;18) occurs in a precursor B cell in the bone marrow. B cells carrying the t(14; 18) can be detected at very low levels in the peripheral blood of >50% of healthy adults. These cells have undergone somatic hypermutation (SHM), and class switch recombination (CSR), indicative of transit through the germinal center. They are prone to intense trafficking, with multiple episodes of germinal center reentry. However, <0.01% of patients with FL-like B cells in the peripheral blood subsequently develop FL. Expansion of FL-like B cells, in either the intestine or the lymph node, lead to 2 early lesions, duodenal-type FL, and ISFN. ISFN can be identified in ∼2% to 3% of unselected lymph node biopsies. Both duodenal-type FL and ISFN progress to systemic FL in only 2% to 3% of cases. These early lesions have a low level of copy number aberrations (CNAs), but share many genetic features with conventional FL, including the t(14;18), and mutations in CREBBP, TNFRSF14, and EZH2. However, multiple mutations in KMT2D may be a later event, associated with more advanced disease. Microenvironmental influences may drive colonization of the intestine, independent of the genetic profile. All tissue sections illustrated are stained for BCL2 by immunohistochemistry, original magnification ×40. Peripheral smear, Wright-Giemsa stain, original magnification ×1000. GC, germinal center.

An increased incidence of FL in the duodenum was first recognized by Yoshino et al.2 Subsequent studies confirmed the presence of the BCL2 translocation, similar to that seen in nodal FL, and described the unique clinical features of this distinctive FL variant. The majority of patients presented with small polypoid lesions confined to the mucosa and submucosa, often in the region of the ampulla of Vater.3 A lesser number of patients had lesions in the distal small bowel. However, regardless of the initial site of presentation, the clinical course was indolent, with a very low risk of nodal or systemic involvement, ∼3%. Similar to the 100% 10-year survival rate reported by Hellmuth et al, clinical outcome with limited treatment was excellent. In the majority of patients, the diagnosis of duodenal-type FL is an incidental finding, with the lesion detected upon endoscopy for other unrelated gastrointestinal findings or surveillance. Notably, conventional FL can involve the intestine, usually with concomitant involvement of mesenteric lymph nodes. Based on these and other distinctive features, the revised 4th Edition of the World Health Organization classification of lymphomas designated duodenal-type FL as a specific variant of FL, to be distinguished from conventional FL.4

Early on, one of the main questions regarding duodenal-type FL was the biological basis for the very indolent clinical course and lack of dissemination beyond the intestine. Bende et al reported that the lymphoid cells expressed the alpha4beta7 integrin, a homing receptor found on normal mucosal T and B lymphocytes as well as lymphomas of mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT).5 However, questions remained regarding the molecular pathogenesis of duodenal-type FL, and both similarities and differences with nodal FL. In the current report, Hellmuth et al confirm the presence of BCL2 R in the majority of cases, but show that most cases show less genetic complexity than other forms of FL. Although the mutational frequencies of several genes mutated in FL were similar (CREBBP, TNFRSF14, EZH2), fewer cases harbored mutations in KMT2D (also known as MLL2), and cases with multiple KMT2D mutations as seen in patients with advanced stage disease were notably absent. These results are similar to those reported by Mamessier et al using array comparative genomic hybridization to study both duodenal-type FL and another early lesion of FL, in situ follicular neoplasia (ISFN), formerly referred to as follicular lymphoma in situ.6 A low level of genetic complexity was seen in all “early lesions” studied, including duodenal-type FL, ISFN, and lymph nodes with partial involvement. Cases of FL with partial nodal involvement have been shown to be associated with low-stage disease.7 Interestingly, in the current report, cases of FL with limited-stage disease also showed a low mutational load, sharing many features with the duodenal-type lesions.

Are there any positive results that distinguish duodenal-type FL from nodal FL? Using whole genome sequencing, the authors found 2 genes mutated at a higher frequency, HVCN1 and EEF1A1, than previously reported in FL. Unfortunately, the authors were not able to examine these genes in their cohort of advanced-stage or limited-stage FL cases, so the specificity of these findings for duodenal-type FL is unclear.

In a separate aspect of the study, the authors address the question of the microenvironment in duodenal-type FL; namely, do the cells localize in, and remain confined to, the intestinal mucosa, because of the microenvironment, or intrinsic attributes of the neoplastic lymphoid cells. They use gene expression profiling of paraffin embedded sections to examine a panel of cytokines and chemokines. Using hierarchical clustering, they compare a small number of samples of duodenal-type FL and limited-stage FL. They show that the 2 groups of lesions cluster separately, suggesting that the microenvironment might be relevant to the disease pathophysiology. However, it is difficult to sort out whether the microenvironment is simply a reflection of the biopsy site, rather than central to disease biology. Future work might address these points by comparing duodenal-type FL with other inflammatory lesions affecting the intestine, as well as lymphomas with secondary involvement. A single such case was examined in the current study, and that 1 “secondary case” appeared to cluster with the nodal FL cases. Another recent report found common themes in the gene expression profile of duodenal-type FL and MALT lymphoma, distinguishing both from nodal FL. Again, it is difficult to sort out the role of the biopsy site in the generation of these data points.8

In conclusion, this study confirms the importance of recognizing duodenal-type FL as a separate variant of FL, both in terms of disease pathogenesis and in patient management. Duodenal-type FL, ISFN, and FL-like B cells in the peripheral blood comprise a group of early lesions that can help us understand the earliest events in FL pathogenesis (see figure).9 Future studies, including assessment of relative allele frequencies of key genes, may identify secondary aberrations predictive of clinical progression.10

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal